INTRODUCTION

Indian Psychiatric Society (IPS) published Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) for management of dementia, in the year 2007. (http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org/cpg2007.asp). The current version of the CPG is an update of the earlier version of CPGs for management of dementia There were three separate CPGs for management of dementia, one each for Reversible Dementias, Alzheimer's Disease and Vascular Dementia, Please note that the present CPG on dementia deals all types of dementia together. The current version of the CPGs for dementia in elderly must be read in conjunction with the previous version of CPGs for dementia. The focus of the present CPG is to provide suggestions and clinical tips to differentiate dementia syndrome from other clinical conditions, identify the subtypes of dementia and then offer suggestions for management.

These guidelines only provide a broad framework for assessment, management and follow-up of older people with dementia. While most of the recommendations are evidence based, these guidelines should not be considered as a substitute of professional knowledge and clinical judgment. The recommendations made as part of these guidelines should be tailored to address the clinical needs of the individual patient and the treatment setting.

AGING, DEPRESSION AND DEMENTIA

Before we examine the management of dementia, let us look at the issues related to the clinical diagnosis of dementia. Mental health problems and disablement are frequent in late life. Dementia and depression are two major mental health problems in late life. It is well known that the prevalence of dementia increases steadily with age. Normal aging itself is associated with age related decline in cognitive functions. Depressive symptoms are more common in later years of life. The differentiation between depressive disorder and a cognitive disorder can be problematic in this age group. There are many symptoms which can be seen in both in depressive disorders as well as in cognitive disorders. Depression can co-exist with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) a condition which is being increasingly recognized as an important entity.

MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT AND DEMENTIA

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a controversial entity but remains a useful construct in terms of targeting interventions to prevent dementia. MCI detection relies largely on subjective memory complaint (SMC) as a presenting symptom. However SMC is heterogeneous in its etiology and poorly predicts medium-term dementia risk. The differentiation of early dementia from MCI depends on the level of cognitive impairment and the resultant disability. Cognitive impairment in dementia causes significant impairment in instrumental activities of daily living and this is known to increase with time. Most diagnostic criteria use the resultant disability as an important differentiating feature. However reliance on informant reports can be problematic as that could be influenced by the social context, expectations of the informant and his or her ability to know and the current level of functioning of the older person.

DEMENTIA SYNDROME

Dementia is a syndrome due to disease of the brain, usually chronic, characterized by a progressive, global deterioration in intellect including memory, learning, orientation, language, comprehension and judgment. It mainly affects older people, after the age of 65 years. Then onwards, the prevalence doubles with every five year increment in age. Dementia is one of the major causes of disability in late-life. People with dementia have difficulty in living independently and have difficulties in social and occupational functioning. The disabilities progress with the severity of dementia

Cognitive changes that are part of normal aging process has to be differentiated from the dementia syndrome. This is difficult in early stages of dementia. Age related changes are more frequent in those who are in their eighties and nineties. Propensity to develop transient cognitive problems like delirium increases with age and in the presence of cognitive impairment

Evaluation of cognitive symptoms

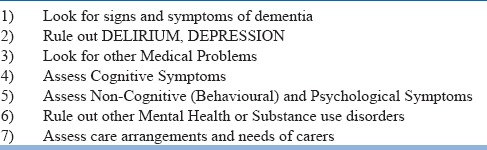

Cognitive symptoms can be due to many conditions and dementia is only one of them. Delineation of the syndrome of dementia and differentiating it from other cognitive disorders is the first task. Other assessments can then follow. The suggested assessments are best carried out as part of the initial evaluation though it might take a few sessions to complete. See table -1.

Table 1.

Assessment for dementia

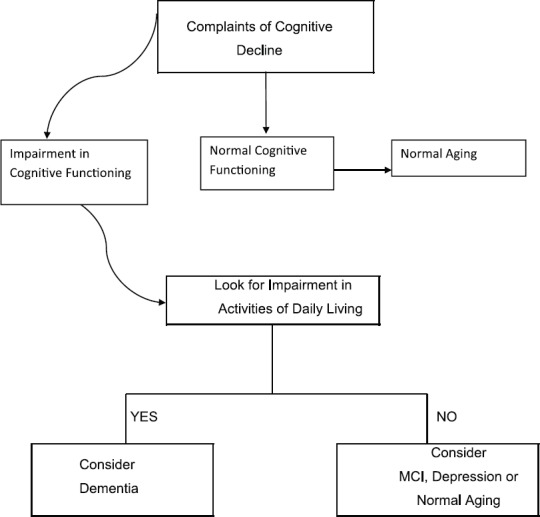

The following assessments will help in making a clinical diagnosis of dementia : See the flow chart below.

History of Cognitive Changes

History taking is the main tool in eliciting and evaluating the nature and progression of cognitive decline. Choose an informant who knows about the person's current and past personal, social and occupational functioning. A reliable informant should be interviewed separately in person. This will allow discussion of a certain information which may otherwise be difficult in the presence of the patient. While doing the assessments, one has to be mindful of the family's culture, values, primary language, literacy level and also the decision making process. A thorough history should include details like the mode of onset of cognitive decline which affects multiple cognitive domains. The pattern progression, clinical manifestations of cognitive dysfunction, behavioral as well as personality changes will have to be enquired into.

Subjects or informants can be asked if the person is forgetful about recent events; especially amnesia for events which happened hours or days back. Does the person forget the fact that he/she had a meal some time after having the meal? Does the person tend to ask the same questions repeatedly even though this was answered many times. Is the person unable to recall where they’ve placed things and often searching for things? A review of current medication is very important. Enquire if there is worsening of cognitive symptoms after initiation of a certain new medication. Details regarding the use of all medications, including over-the-counter products, may be collected. See if the person is on medications with anti-cholinergic effects which can worsen cognitive functions.

Importance of Identification of Delirium

Delirium is an important differential diagnosis of dementia. Patients with pre-existing dementia could present for the first time with superimposed delirium. Sudden worsening of cognitive functions and appearance of behavioural symptoms should alert the clinician to the possibility of delirium. Delirium is a medical emergency signs that needs to be identified early and evaluated immediately.

A diagnosis of dementia cannot be made if the cognitive deficits occur exclusively during the course of delirium. Delirium is characterized by a disturbance of consciousness and a change in cognition that develop over a short period of time. The disorder has a tendency to fluctuate during the course of the day, and there is evidence from the history, examination or investigations that the delirium is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal.

The ICD 10 diagnostic criteria for Delirium is given below

ICD 10 CRITERIA FOR DELIRIUM, NOT INDUCED BY ALCOHOL AND OTHER PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES

Clouding of consciousness, i.e. reduced clarity of awareness of the environment, with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention.

-

Disturbance of cognition, manifest by both:

-

(1)impairment of immediate recall and recent memory, with relatively intact remote memory;

-

(2)disorientation in time, place or person.

-

(1)

-

At least one of the following psychomotor disturbances:

-

(1)rapid, unpredictable shifts from hypo-activity to hyper-activity;

-

(2)increased reaction time;

-

(3)increased or decreased flow of speech;

-

(4)enhanced startle reaction.

-

(1)

-

Disturbance of sleep or the sleep-wake cycle, manifest by at least one of the following:

-

(1)insomnia, which in severe cases may involve total sleep loss, with or without daytime drowsiness, or reversal of the sleep-wake cycle;

-

(2)nocturnal worsening of symptoms;

-

(3)disturbing dreams and nightmares which may continue as hallucinations or illusions after awakening.

-

(1)

Rapid onset and fluctuations of the symptoms over the course of the day.

-

Objective evidence from history, physical and neurological examination or laboratory tests of an underlying cerebral or systemic disease (other than psychoactive substance-related) that can be presumed to be responsible for the clinical manifestations in A-D.

-

Common causes of Delirium include:

- Infection (e.g. pneumonia, urinary track infection, etc.)

- Drugs (particularly those with anticholinergic side effects e.g. antidepressants, anti-parkinsonian /anticholinergic drugs, sedatives, etc.)

- Cardiological (e.g. myocardial infarction, heart failure)

- Metabolic imbalances (e.g. secondary to dehydration, renal failure)

- Endocrine and metabolic (e.g. cachexia, thiamine deficiency, thyroid dysfunction)

- Neurological (e.g. stroke, subdural haematoma, Epilepsy)

- Substance intoxication or withdrawal (e.g. alcohol)

- Respiratory (e.g. pulmonary embolus, hypoxia).

-

Clinician should take care, not to misdiagnose Delirium as Dementia and also not to miss the diagnosis of Delirium when it is superimposed on dementia. When there is clinical suspicion of delirium, the efforts should focus on identifying the causes. Delirium in older people are most often multifactorial in etiology and identification of the underlying conditions would enable us to provide interventions to reverse/modify them. The evaluations need to be comprehensive so that all common causes can be ruled out. Prolonged delirium could lead to more neuronal damage and accelerate cognitive decline by impacting the cognitive reserve

The interface between Delirium & Dementia

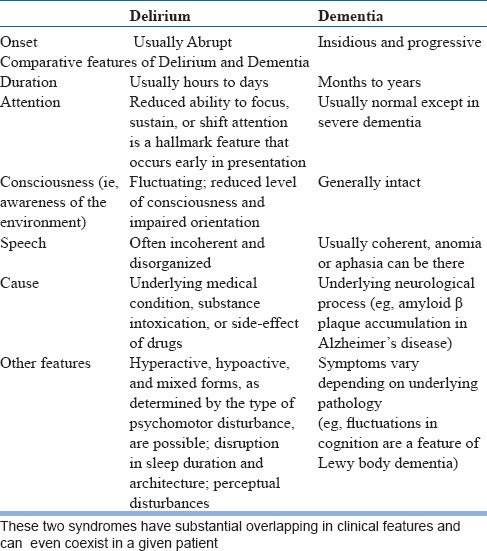

Delirium and dementia are two major causes for cognitive impairment in later years of life. Though these two conditions had been conceptualized as distinct, mutually exclusive entities, it can be difficult at times to differentiate between them. Delirium in late life is often superimposed on pre-existing dementia and can be the reason for help seeking. Dementia is the leading risk factor for delirium in an older person. Occurrence of delirium in turn is a risk factor for subsequent dementia in older people without pre-existing dementia. The clinician needs to differentiate between three possible scenarios namely Delirium with no features suggestive of pre-existing dementia dementia with no features suggestive of delirium dementia with superimposed delirium. See table-2 for broad guidelines for making this distinction, which by no means, will be easy in a given clinical setting. When faced with uncertainty, it is better to attribute the symptoms to delirium and manage it as delirium. This will allow careful monitoring and detailed evaluation to identify modifiable conditions/factors.

Table 2.

Differentiation between Delirium & Dementia

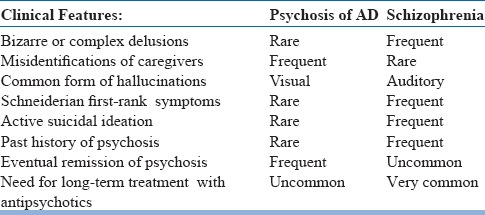

Dementia with Psychotic Symptoms and Schizophrenia

Presence of BPSD, especially delusions with or without hallucinations in mild to moderate dementia can resemble schizophrenia or other psychotic conditions in late life. The key differentiating features here are history of progressive cognitive decline which has onset prior to the development of psychotic symptoms the presence of clinically significant impairment in multiple cognitive domains on clinical evaluation. This distinction is rather easy when there is long duration of illness starting from adulthood. But it could be difficult when psychotic symptoms have onset after the age of 60 years and also in situations where it is difficult to test cognitive functions due to active psychotic symptoms. One could also come across individuals who after many years of illness with onset during adulthood, either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, present with cognitive decline and clinical features suggestive of dementia. In such situations an additional diagnosis of dementia can be made apart from the diagnosis of the pre existing mental health condition. See table-3 for some clinical tips

Table 3.

Psychosis of AD compared with Schizophrenia in the elderly

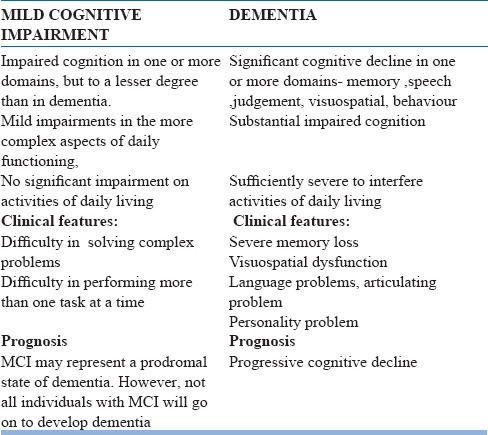

Differentiation between Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment

The differentiation between early dementia and mild cognitive impairment can be difficult at times but efforts to make that distinction is always warranted. DSM 5 uses the term Mild Neurocognitive Disorder to refer to this condition. ICD 10 does not have specific criteria. The following DSM 5 criteria may be used as a guide for clinical diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment.

DSM 5 criteria for Mild Cognitive Impairment

-

Evidence of modest cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual motor, or social cognition) based on:

- Concern of the individual, a knowledgeable informant, or the clinician that there has been a mild decline in cognitive function; and

- A modest impairment in cognitive performance, preferably documented by standardized neuropsychological testing or, in its absence, another quantified clinical assessment.

The cognitive deficits do not interfere with capacity for independence in everyday activities (i.e., complex instrumental activities of daily living such as paying bills or managing medications are preserved, but greater effort, compensatory strategies, or accommodation may be required).

The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of a delirium.

The cognitive deficits are not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder, schizophrenia).

Behavioral disturbance (e.g., psychotic symptoms, mood disturbance, agitation, apathy, or other behavioral symptoms

The diagnostic challenge in MCI here is in the assessment of “significant impairment in functional ability,” which is required for the diagnosis of dementia. There is also the controversy about the best way to objectively measure memory loss. Early recognition of the condition may help the clinician to monitor the progression of cognitive and other symptoms and the later conversion to dementia. This might allow potential use of evidence based preventive interventions as and when they become available. The recognition of MCI as a diagnostic allows us to have a better understanding of the nature of mild memory loss, which is far more common than dementia among the older segments of the population. Table-4 lists out the main differences between the two clinical conditions

Table 4.

MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT Vs DEMENTIA

Assessment of Dementia Syndrome

We need to rule out delirium and mild cognitive disorder before we make a clnical diagnosis of dementia. Then one should apply and see if the person meets the diagnostic criteria for Dementia. If that is met, then there is a need to make further evaluations. The next part of evaluation is aimed at establishing the cause for the dementia syndrome.

Types and Causes of Dementia

Dementia is a syndrome which can be caused by many diseases. After the clinical recognition of dementia syndrome, the evaluations shall focus on identifying the cause of dementia. Causes can be broadly classified as “reversible causes’ and “Irreversible” causes. Though “Reversible” causes are less frequent, they carry good prognosis with prompt treatment of the underlying condition. Thus the evaluation for all potentially reversible conditions which cause dementia syndrome is the first most important step in the assessment of dementia syndrome and this is essential in all cases presenting with features of dmentia. The type of investigations can be decided based on the clinical features and context of care. This aspect is discussed in detail in the 2009 Dementia Supplement of Indian Journal of Psychiatry.

Clinical Assessment

Patients who seek help in clinical settings often do not represent cases prevalent in the community. Reversible causes thus may be much more common in clinical settings than in community settings. Routine investigations should include complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and serum/blood levels of urea, electrolytes, calcium and phosphate, liver, renal and, thyroid function tests, urine analysis, VDRL and Serum B12, and Folate levels. CT scan or MRI scan, at times, can be a very useful investigation in the differential diagnosis of dementia. Investigations for testing the HIV status, ECG, Chest radiograph, Electroencephalogram, Neuropsychological assessment etc are investigations worth considering.

Common Potentially Reversible Causes

Depression

Medication Induced (Especially drugs with anticholinergic activity)

Metabolic derangements

Thyroid disorders (Hyopthyroidism is a common cause)

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Thiamine deficiency

Chronic disease (e.g., renal failure, hepatic failure, malignancy)

-

Gastrointestinal disorders

- Whipple's disease

- Vitamin E deficiency

- Pellagra

-

Structural brain lesions

- Subdural hematoma

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus

- Tumor

-

Infections

- Neurosyphilis

- HIV/AIDS

How to investigate and rule out Reversible causes?

A reliable, detailed history will guide us in identifying the causes of dementia. We have to rule out common reversible causes and the eminently reversible causes first. See table-5 for the list. Investigations to rule out less common causes may be needed when the clinical features indicate a high index of suspicion of reversible dementia.

Table 5.

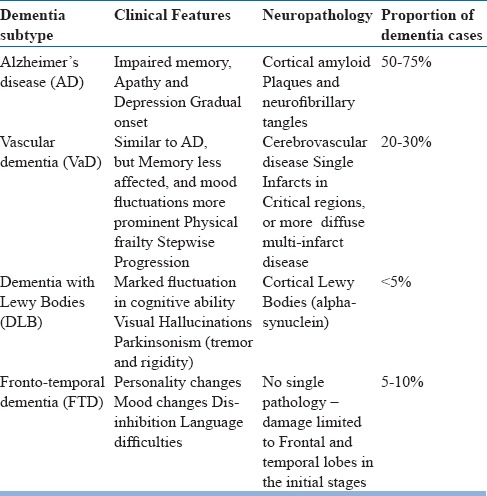

Common Subtypes of Irreversible Dementias

Dementia syndrome is linked to many underlying causes and diseases of the brain. The most common causes accounting for vast majority of cases are due to Alzheimer's disease, Vascular dementia, Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Fronto-temporal dementia.

Please follow the steps described in Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 for systematic evaluation of a person presenting with cognitive symptoms

Figure 1.

Initial assessment

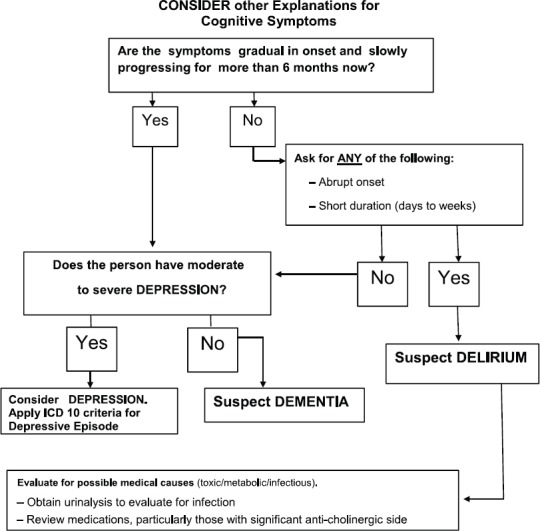

Figure 2.

Clinical Assessment: Step 1

Figure 3.

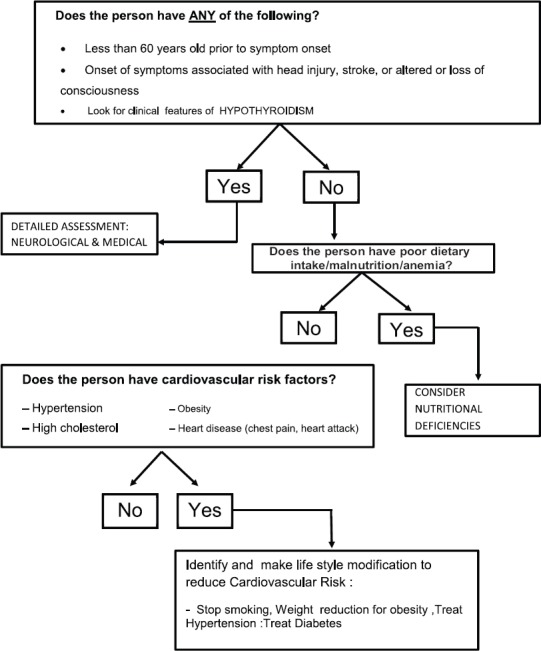

STEP 2: Evaluate Cognitive Impairment

Figure 4.

STEP 3 Evaluation after recognition of the syndrome of dementia look for medical problems

Cognitive assessment can be made as part of detailed examination of higher functions. Commonly used instruments like Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) can be used. Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (ACE) is a more detailed test battery for assessing cognitive functions. Assessment of the activities of daily living is very important. This information is essential in formulating the individualized plan of intervention. Everyday Activities Scale for India (EASI) developed during the Indo-US Cross-National Dementia Epidemiology Study is useful for this purpose, especially in the rural illiterate. Use of simple instruments like the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale can help in assessing the severity of dementia in routine clinical practice. Assessment of non-cognitive symptoms like Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) is yet another important part of clinical assessment. Two commonly used scales for assessment of these symptoms are the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) and the BEHAVE-AD Both these scales use the caregiver interview for rating behavioural symptoms. Knowledge of instruments like MMSE, ACE, EASI, Behave-AD and NPI is helpful in the detailed and effective assessments of patients with dementia.

Clinical Criteria for Diagnosis of Dementia

ICD- 10 clinical criteria may be used for diagnosis of Dementia and subtyping. Alterantively one could use the DSM-5 criteria too. Since ICD 10 does not give criteria for Dementia with Lewy Bodies, one could instead rely on the Consensus criteria or the DSM-5 criteria. You may use the consensus clinical diagnostic criteria.

After detailed assessment usually, the clinician would be in a position to judge the cause of the dementing illness. However at times, even the distinction between Vascular Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease (AD) may appear difficult. Clinical recognition of the subtypes of dementia is important and is easier during the early part of the illness. The differentiation between Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) and AD can be attempted during the initial evaluations itself. Such differentiation is feasible in clinical practice by using clinical criteria for these subtypes.

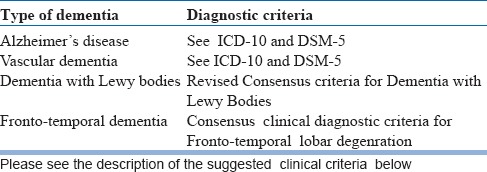

The clinicians might choose any standard criteria for making clinical diagnosis of dementia, especially common sub-types. See Table 6 for the criteria which may be useful in clinical practice

Table 6.

Diagnostic criteria for Dementia

ICD 10 – DEMENTIA

G1. Evidence of each of the following:

(1) A decline in memory, which is most evident in the learning of new information, although in more severe cases, the recall of previously learned information may be also affected. The impairment applies to both verbal and non-verbal material. The decline should be objectively verified by obtaining a reliable history from an informant, supplemented, if possible, by neuropsychological tests or quantified cognitive assessments. The severity of the decline, with mild impairment as the threshold for diagnosis, should be assessed as follows:

Mild: a degree of memory loss sufficient to interfere with everyday activities, though not so severe as to be incompatible with independent living. The main function affected is the learning of new material. For example, the individual has difficulty in registering, storing and recalling elements in daily living, such as where belongings have been put, social arrangements, or information recently imparted by family members.

Moderate: A degree of memory loss which represents a serious handicap to independent living. Only highly learned or very familiar material is retained. New information is retained only occasionally and very briefly. The individual is unable to recall basic information about where he lives, what he has recently been doing, or the names of familiar persons.

Severe: a degree of memory loss characterized by the complete inability to retain new information. Only fragments of previously learned information remain. The subject fails to recognize even close relatives.

(2) A decline in other cognitive abilities characterized by deterioration in judgement and thinking, such as planning and organizing, and in the general processing of information. Evidence for this should be obtained when possible from interviewing an informant, supplemented, if possible, by neuropsychological tests or quantified objective assessments. Deterioration from a previously higher level of performance should be established. The severity of the decline, with mild impairment as the threshold for diagnosis, should be assessed as follows:

Mild. The decline in cognitive abilities causes impaired performance in daily living, but not to a degree making the individual dependent on others. More complicated daily tasks or recreational activities cannot be undertaken.

Moderate. The decline in cognitive abilities makes the individual unable to function without the assistance of another in daily living, including shopping and handling money. Within the home, only simple chores are preserved. Activities are increasingly restricted and poorly sustained.

Severe. The decline is characterized by an absence, or virtual absence, of intelligible ideation. The overall severity of the dementia is best expressed as the level of decline in memory or other cognitiveabilities, whichever is the more severe (e.g. mild decline in memory and moderate decline in cognitive abilitiesindicate a dementia of moderate severity).

G2. Preserved awarenenss of the environment (i.e. absence of clouding of consciousness (as defined in F05, criterion A)) during a period of time long enough to enable the unequivocal demonstration of G1. When there are superimposed episodes of delirium the diagnosis of dementia should be deferred.

G3. A decline in emotional control or motivation, or a change in social behaviour, manifest as at least one of the following:

-

(1)

emotional lability;

-

(2)

irritability;

-

(3)

apathy;

-

(4)

coarsening of social behaviour.

G4. For a confident clinical diagnosis, G1 should have been present for at least six months; if the period since the manifest onset is shorter, the diagnosis can only be tentative.

Comments: The diagnosis is further supported by evidence of damage to other higher cortical functions, such as aphasia, agnosia, apraxia.

Judgment about independent living or the development of dependence (upon others) need to take account of the cultural expectation and context.

Dementia is specified here as having a minimum duration of six months to avoid confusion with reversible states with identical behavioural syndromes, such as traumatic subdural haemorrhage (S06.5), normal pressure hydrocephalus (G91.2) and diffuse or focal brain injury (S06.2 and S06.3).

ICD 10

F00 DEMENTIA IN ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

The general criteria for dementia (G1 to G4) must be met.

There is no evidence from the history, physical examination or special investigations for any other possible cause of dementia (e.g. cerebrovascular disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus), a sysytemic disorder (e.g. hypothyroidism, vit. B12 or folic acid deficiency, hypercalcaemia), or alcohol- or drug-abuse.

Comments: The diagnosis is confirmed by post mortem evidence of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in excess of those found in normal ageing of the brain.

The following features support the diagnosis, but are not necessary elements: Involvement of cortical functions as evidenced by aphasia, agnosia or apraxia; decrease of motivation and drive, leading to apathy and lack of spontaneity; irritability and disinhibition of social behaviour; evidence from special investigations that there is cerebral atrophy, particularly if this can be shown to be increasing over time. In severe cases there may be Parkinson-like extrapyramidal changes, logoclonia, and epileptic fits.

Specification of features for possible subtypes. Because of the possibility that subtypes exist, it is recommended that the following characteristics be ascertained as a basis for a further classification: age at onset; rate of progression; the configuration of the clinical features, particularly the relative prominence (or lack) of temporal, parietal or frontal lobe signs; any neuropathological or neurochemical abnormalities, and their pattern.

The division of AD into subtypes can at present be accomplished in two ways: first by taking only the age of onset and labeling AD as either early or late, with an approximate cut-off point at 65 years

ICD 10

F01 VASCULAR DEMENTIA

G1. The general criteria for dementia (G1 to G4) must be met.

G2. Unequal distribution of deficits in higher cognitive functions, with some affected and others relatively spared. Thus memory may be quite markedly affected while thinking, reasoning and information processing may show only mild decline.

-

G3. There is clinical evidence of focal brain damage, manifest as at least one of the following:

-

(1)unilateral spastic weakness of the limbs;

-

(2)unilaterally increased tendon reflexes;

-

(3)an extensor plantar response;

-

(4)pseudobulbar palsy.

-

(1)

G4. There is evidence from the history, examination, or tests, of a significant cerebrovascular disease, which may reasonably be judged to be etiologically related to the dementia (e.g. a history of stroke; evidence of cerebral infarction).

Consensus criteria for FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA

-

Core diagnostic features

- Insidious onset and gradual progression

- Early decline in social interpersonal conduct

- Early impairment in regulation of personal conduct

- Early emotional blunting

- Early loss of insight

-

Supportive diagnostic features

-

Behavioral disorder

- Decline in personal hygiene and grooming

- Mental rigidity and inflexibility

- Distractibility and impersistence

- Hyperorality and dietary changes

- Perseverative and stereotyped behavior

- Utilization behavior

-

Speech and language

-

1.Altered speech output

-

a.Aspontaneity and economy of speech

-

b.Pressure of speech

-

2.Stereotypy of speech

-

3.Echolalia

-

4.Perseveration

-

5.Mutism

-

1.

-

Physical signs

- Primitive reflexes

- Incontinence

- Akinesia, rigidity, and tremor

- Low and labile blood pressure

-

Investigations

- Neuropsychology: impairment on frontal lobe tests without severe amnesia, aphasia, or perceptuospatial disorder

- Electroencephalography: normal on conventional EEG despite clinically evident dementia

-

Brain imaging (structural and/or functional): predominant frontal and/or anterior temporal abnormality

Revised criteria for the clinical diagnosis of probable and possible dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)

Essential for a diagnosis of DLB is dementia, defined as a progressive cognitive decline of sufficient magnitude to interfere with normal social or occupational functions, or with usual daily activities. Prominent or persistent memory impairment may not necessarily occur in the early stages but is usually evident with progression. Deficits on tests of attention, executive function, and visuoperceptual ability may be especially prominent and occur early.

-

Core clinical features (The first 3 typically occur early and may persist throughout the course.)

- Fluctuating cognition with pronounced variations in attention and alertness.

- Recurrent visual hallucinations that are typically well formed and detailed.

- REM sleep behavior disorder, which may precede cognitive decline.

- One or more spontaneous cardinal features of parkinsonism: these are bradykinesia (defined as slowness of movement and decrement in amplitude or speed), rest tremor, or rigidity.

-

Supportive clinical features

Severe sensitivity to antipsychotic agents postural instability; repeated falls; syncope or other transient episodes of unresponsiveness; severe autonomic dysfunction, e.g., constipation, orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence; hypersomnia; hyposmia; hallucinations in other modalities; systematized delusions; apathy, anxiety, and depression.

-

Indicative biomarkers

- Reduced dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by SPECT or PET. Abnormal (low uptake) 123iodine-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy. Polysomnographic confirmation of REM sleep without atonia.

-

Supportive biomarkers

- Relative preservation of medial temporal lobe structures on CT/MRI scan. Generalized low uptake on SPECT/PET perfusion/metabolism scan with reduced occipital activity 6 the cingulate island sign on FDG-PET imaging. Prominent posterior slow-wave activity on EEG with periodic fluctuations in the pre-alpha/theta range.

-

Probable DLB can be diagnosed if:

- Two or more core clinical features of DLB are present, with or without the presence of indicative biomarkers

- Only one core clinical feature is present, but with one or more indicative biomarkers.

Probable DLB should not be diagnosed on the basis of biomarkers alone.

-

Possible DLB can be diagnosed if:

- Only one core clinical feature of DLB is present, with no indicative biomarker evidence

- One or more indicative biomarkers is present but there are no core clinical features.

-

DLB is less likely:

- In the presence of any other physical illness or brain disorder including cerebrovascular disease, sufficient to account in part or in total for the clinical picture, although these do not exclude a DLB diagnosis and may serve to indicate mixed or multiple pathologies contributing to the clinical presentation

- I parkinsonian features are the only core clinical feature and appear for the first time at a stage of severe dementia.

DLB should be diagnosed when dementia occurs before or concurrently with parkinsonism. The term Parkinson disease dementia (PDD) should be used to describe dementia that occurs in the context of well-established Parkinson disease. In a practice setting the term that is most appropriate to the clinical situation should be used and generic terms such as Lewy body disease are often helpful. In research studies in which distinction needs to be made between DLB and PDD, the existing 1-year rule between the onset of dementia and parkinsonism continues to be recommended.

Aassessment of the following will help in planning the management:

Activities of Daily Living (ADL). This is essentiality about the the ablity for feeding, bathing, dressing, mobility, toileting, continence and also the ability to manage finances and medications

Assess the Cognitive Status using a reliable and valid instrument (e.g. the MMSE, MOCA etc)

Look for other Medical Conditions, Behavioral Problems, Psychotic Symptoms, or Depressive Symptoms

Identify the Primary Caregiver: Assess the adequacy of family and other support systems.

Assess Caregiver's needs and risks; Re-asses this a regular basis

Assess the patient's decision-making capacity and whether a surrogate has been identified

Assessment of co-morbidity:

Multimorbidity is common in latelife. A clear understanding of physical aand mental health is important for planning dementia care. Assess for

-

Co-morbidity

- Depression

- Diabetes/HTN/Vascular diseases

- Parkinsonism

- Other chronic diseses like COPD/Arthritis

Nutritional Status. Poor nutritional status can be a consequence of poor self care and poor dietary intake

-

Care arrangements

- Identify the Primary caregiver. This is crucial. In most instances there will be one person who generally co-ordinates and provide most of the care provision

- Assess Caregiver support systems

- Is there a Formal/Paid caregiver

- Try to link with local Dementia Society/Palliative Care service

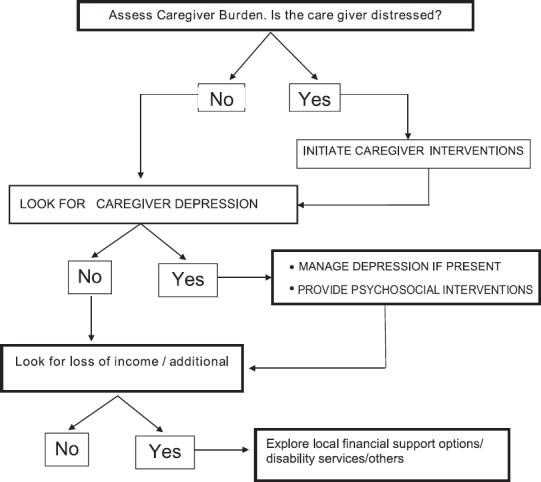

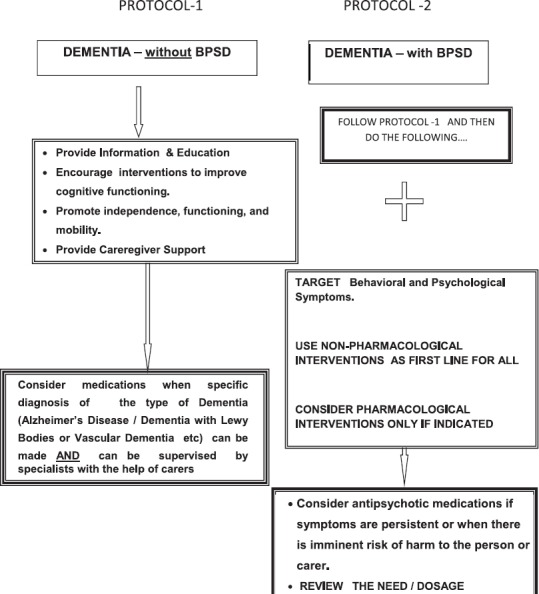

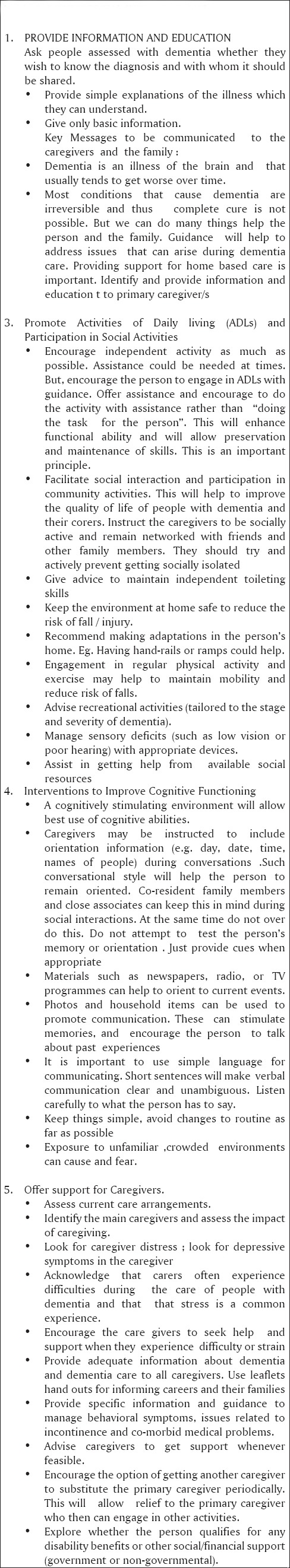

2. Formulating a treatment plan (Figure 5-8)

Figure 5.

STEP 4 EVALUATE & ADDRESS CAREGIVER NEEDS

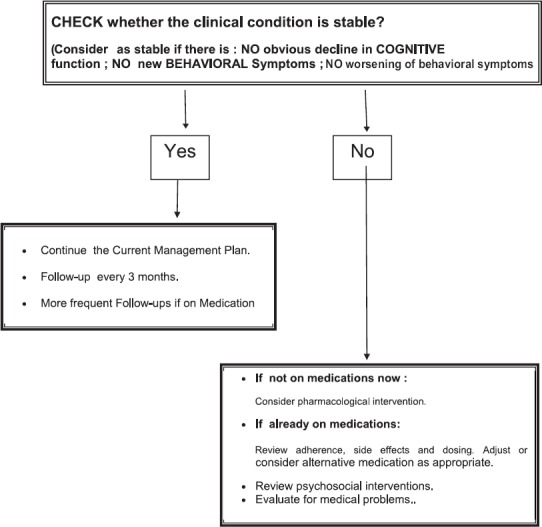

Figure 8.

Make Follow-up Plans

Diagnostic Evaluation. Please follow the earlier described format to make assessments when there is history of cognitive decline. Those steps will help to identify and differentiate between syndromes like delirium, dementia and mild cognitive disorder. Once the dementia syndrome is identified the assessments shall be aimed at the following

Type of Dementia

Presence and nature of cognitive and non-cognitive symptoms

Asses Caregiver support

Assess caregiver needs

Decide Caregiver interventions

Provision of Information & Education

Guidance for management of symptoms of Dementia

Caregiver Support

Decide need for Specific Non-pharmacological interventions for BPSD

Decide need for pharmacological methods

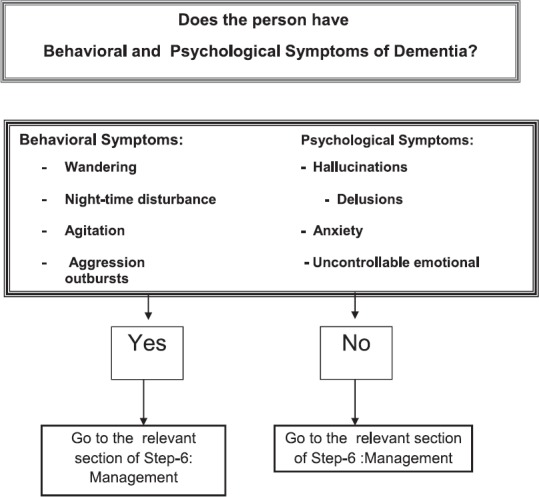

Figure 6.

STEP 5:IDENTIFICATION OF SYMPTOMS WHICH NEED SPECIAL ATTENTION

Figure 7.

Step 6: Management of Dementia

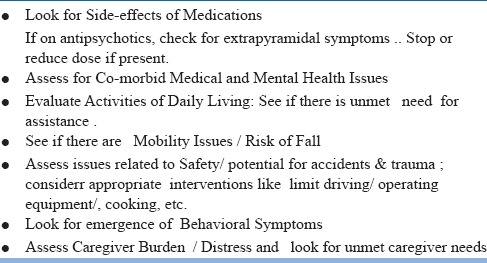

Please see table 7 for follow up plans

Table 7.

ASSESSMENTS DURING FOLLOW-UP VISITS

Choice of treatment settings

Home-based care :By and large the commonest setting for dementia care. The need is to identify and support the needs of home-based care. Encourage the family to access/take help from out reach services like community health workers like ASHAs /volunteers of palliative care services. They may contact local chapters of Alzhiemer's and Related Disorders Society, Help Age India, Paliative Care Networks, other voluntary agencies engaged in geriatric care and seek support and guidance

Institutional care: When the hom-based care is not feasible or unavailable, the person with dementia may need instituitional care with provision for assisted living

Short-term hospitalization : This is often required when there is a medical or surgical morbidity which often cannot be handled in ambulatory care settings. Onset of delirium or sudden worsening of BPSD also could necessitate brief hospitalization. Brief hospitalisations can be used to provide more information and assistance to caregivers. This can be an opportunity to identify unmet care needs as well as needs of the caregivers.

Long-term assisted living. There is a need for this facility especially when the home-based care is not able to meet the demands of care. This is a reality in many household as the family size is dwindling and most young people work outside their homes.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Non-pharmacological management strategies (Table -8) have an important role in the management of dementia of any type. It is particularly helpful in elderly patients who may not tolerate pharmacological agents due to the development of adverse effects even in smaller doses. There are specific non-pharmacological interventions targeting the cognitive as well as non-cognitive symptoms and challenging behaviours seen in dementia.

Table 8.

PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTIONS

-

Non-pharmacological interventions for cognitive symptoms

People with mild to moderate dementia of all types should be encouraged to participate in structured cognitive stimulation programmes. They benefit cognition in such patients irrespective of whether any drug is prescribed or not. They are also beneficial in improving and maintaining their functional capacity. This is based on the view that lack of cognitive activity hastens cognitive decline. Reality orientation and reminiscence therapy is of use in this regard.

-

Non-pharmacological interventions for non-cognitive symptoms and challenging behaviour

Non-cognitive symptoms and challenging behaviors significantly increase the burden of care. They lead to caregiver distress and burnout and hence is an important concern in the management of dementia. Common non-cognitive symptoms seen in dementia are delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, agitation and associated aggressive behavior. Challenging behaviours include a range of difficulties experienced by people with dementia and has a considerable impact on their caregivers. Common challenging behaviours are aggression, agitation, wandering, hoarding, sexual disinhibition, apathy and shouting.

Non-pharmacological interventions for the non-cognitive symptoms and challenging behaviours should be tailored for each patient with participation from the caregivers. This shall be preceded by assessments aimed at identifying factors which may be responsible to generate, aggravate or improve such behaviour. Such an assessment should be comprehensive and consider the person's physical health, possible undetected pain or discomfort, side effects of medication, psychosocial factors, cultural and religious background, and physical environmental factors. Several modalities of non-pharmacological interventions like aromatherapy, multisensory stimulation, music/dancing therapy, massage and animal assisted therapy are available. The choice of therapy should be made considering the availability along with the person's preferences, skills and abilities. These interventions can be delivered by health and social care staff and volunteers with proper training and supervision. The response to each form of therapy should be monitored and the care plan should be reviewed from time to time as there may be individual variations in the response to each of these modalities.

Pharmacological treatment of Dementia

General Principles

The pharmacological treatment of dementia is associated with important challenges such as complexities in the clinical presentation and diagnosis, non-availability of therapeutic agents with robust effectiveness and issues related to tolerability of medications used in the treatment of dementia.

Disease modifying drugs to treat Alzheimer's disease and other related dementias is an important unmet need in the treatment of chronic medical disorders in elderly.

The currently available options for the pharmacological treatment of dementia are essentially symptomatic treatments with limited effectiveness.

It would be preferable to plan the pharmacological treatment of dementia after comprehensive evaluation to understand the possible subtype, associated behavioural and psychological symptoms, comorbidity etc

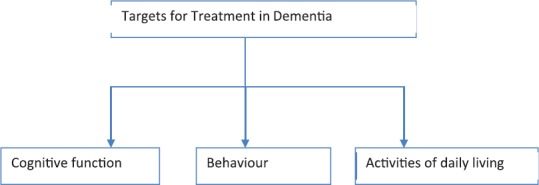

Treatment of dementia needs to be focused on improving the cognitive function, amelioration of associated behavioral and psychological symptoms and improvement or stabilization of global functioning in daily activities.

It would be useful to have clear understanding of the treatment targets and proper monitoring of outcomes following treatment to optimize the treatment appropriately(Figure-9).

Behavioral and psychosocial interventions are required for all patients with dementia. Pharmacological treatment needs to be planned in addition to this particularly for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Figure 9.

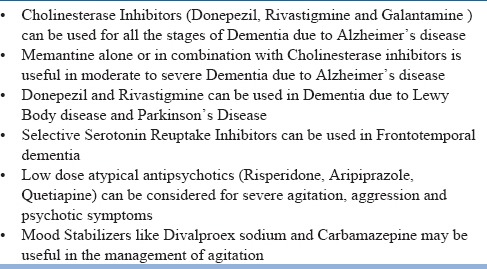

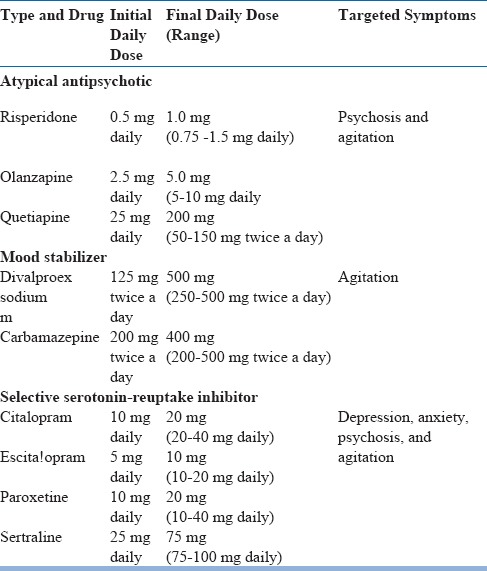

Pharmacological treatment for cognitive symptoms of Dementia(Tables 9 & 10)

Table 9.

Pharmacological Treatment of Dementia

Table 10.

Approved Antidementia drugs

Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and a major contributor for global disease burden. Hence there has been very active global effort to develop effective disease modifying drug for Alzheimer's disease in the past decade.

However, no new effective drug has been identified for improving the cognitive function in patients with dementia due to Alzheimer's disease in the last decade.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors (Donepezil, Rivastigmine and Galantamine) and NMDA antagonist (Memantine) are the approved pharmacological treatment options for the cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's Dementia

Donepezil has been approved for all stages of Alzheimer's dementia. Rivastigmine and Galantamine has been approved for mild to moderate Alzheimer's dementia

Memantine has been approved for moderate to severe Alzheimer's dementia

Combination of Donepezil and Memantine has been approved for moderate to Severe Alzheimer's dementia

Rivastigmine Transdermal patch (4.6mg, 9.5mg or 13,3mg per 24 hours) has been approved for mild to moderate Alzheimer's dementia. The extent of adverse effects with Rivastigmine is lesser in transdermal patch than oral formulation.

There is no clear evidence regarding the benefit of Cholinesterase inhibitors for the management of behavioral and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer's dementia.

The efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors is established clearly in the short term randomized controlled trials lasting for 3 to 6 months for the cognitive domains and global functioning.

Few studies have indicated continued benefit of cholinesterase inhibitors in the long term (up to 1 year). But there are limitations in the quality of this evidence.

The benefit of cholinesterase inhibitors in the long term is suggested through the observation of deterioration of cognitive function and global functioning after the withdrawal of cholinesterase inhibitors.

The adverse effects that are commonly noted to occur with Cholinesterase inhibitors are primarily related to cholinergic effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, bradycardia and falls).

The most common adverse effects with cholinesterase inhibitors are gastrointestinal side effects. The cholinergic effects are usually dose related. The tolerability appears to improve with dose reduction and slower titration.

The benefit with cholinesterase inhibitors is difficult to establish at individual patient level in view of the progressive nature of the illness and the possibility of contribution to cognitive decline from multiple factors.

The assessment of response to treatment is based on the effects on cognitive symptoms, activities of daily living and the clinician judgement about the global change.

Memantine can be considered as the choice of drug for treatment of patients with Alzheimer's dementia when cholinesterase inhibitors are contraindicated or could not be tolerated due to adverse effects.

Despite the minor differences in the mechanism of action of Donepezil, Rivastigmine and Galantamine, there is no clear evidence to support choosing any specific cholinesterase inhibitor over other drugs.

It would be useful to do Electrocardiogram to rule out conduction abnormalities and clarify about pre-existing gastrointestinal side effects like nausea and vomiting prior to initiating cholinesterase inhibitors.

Patients initiated on medications for dementia requires follow up evaluation after 4 to 6 weeks to review the adverse effects and adjust the dose as required.

If a patient is not tolerating one cholinesterase inhibitor and it has not improved with dose reduction or slower titration, changeover to another cholinesterase inhibitor can be considered.

Rivastigmine transdermal patch can be considered if there are significant gastrointestinal side effects with oral cholinesterase inhibitor.

High dose (11.5 and 23mg) extended release Donepezil has been approved for use in moderate to severe dementia after 3 months of stabilization with 10mg Donepezil.

The approval for Donepezil 23mg is based on a single randomized controlled trial which showed that it was significantly better than Donepezil 10mg for improving cognitive function in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's dementia.

The clinical utility of Donepezil 23mg is not clear as the marginal improvement in cognitive function without significant improvement in global functioning may have limited clinical significance for individuals with moderate to severe dementia.

The frequency of cholinergic adverse effects is also higher with Donepezil 23mg contributing to poor tolerability and increased risk for discontinuation

Other than cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, there are no other approved drugs to improve cognitive function in patients with dementia. Cognitive enhancers like Ginko Biloba and Piracetam do not have clear evidence to be recommended for routine use in patients with dementia.

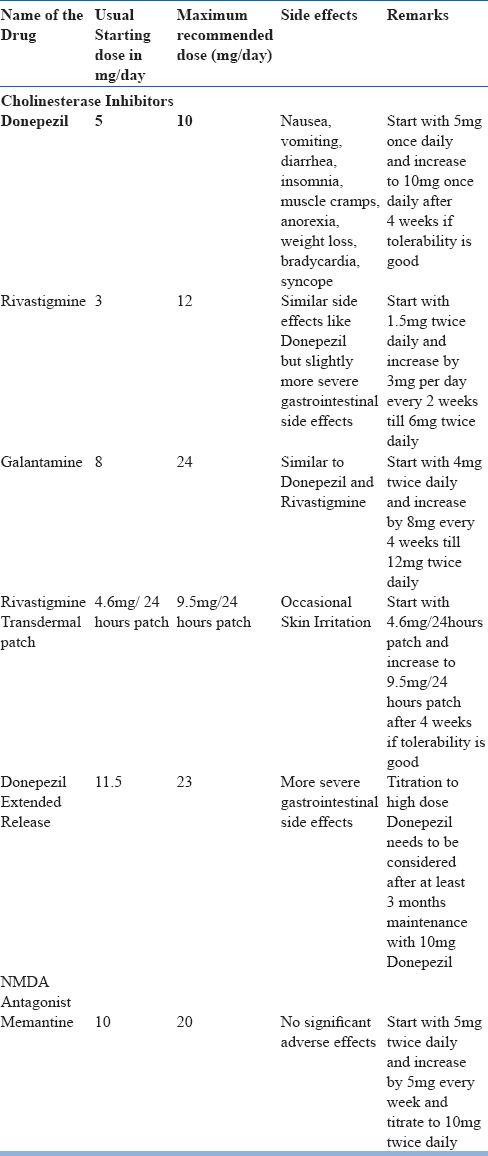

Pharmacological treatment for Behavioural and Psychological symptoms of dementia (Table 11)

Table 11.

Psychotropic Agents Useful for the Treatment of BPSD

Behavioral and Psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) is very common in patients with dementia. Nearly all patients with dementia are likely to develop BPSD at any point of time during the illness.

BPSD is often the most important contributor for the distress and burden in caregivers. Many patients with dementia are brought for evaluation and treatment primarily due to BPSD.

BPSD is also the important factor that determines the risk for institutionalization.

Apathy, depression, agitation, aggression, wandering behavior, sleep disturbance and psychotic symptoms are the most common BPSD symptoms in dementia.

Risperidone is the only treatment approved for the treatment of agitation and aggression in patients with dementia.

Use of antipsychotics in elderly with dementia is associated with increased risk for cerebrovascular adverse events and mortality

Pharmacological treatment for BPSD needs to be considered only if the symptoms are distressing to the patient / caregiver or if it is contributing to the risk for harm to patient / others.

Recent evidence has suggested the possibility of improvement in agitation with Citalopram when it is not severe enough to initiate antipsychotics.

Like Citalopram, other Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI) are also likely to be effective in controlling the agitation in patients with dementia. However, there is need for more evidence to support this treatment option.

Higher dose of Citalopram (used in the study showing positive effect on agitation in dementia) is associated with increased risk for QT interval prolongation. Hence it is not recommended.

Low dose atypical antipsychotics (Aripiprazole, Risperidone, Quetiapine etc) can be considered for severe psychotic symptoms and agitation

Quetiapine and Clozapine can be considered by severe psychotic symptoms in dementia due to Lewy body disease and Parkinson's disease

Treatment with SSRI and Mirtazapine has not contributed to significant improvement of depression in patients with dementia.

Pharmacological Treatment in Non-Alzheimer's dementia

Clinical trials on the treatment of dementia has largely focused on Alzheimer's dementia due to high prevalence and public health significance

There is no clear evidence for efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine in Vascular dementia and Frontotemporal dementia

Cholinesterase inhibitors (Particularly Rivastigmine and Donepezil) have significant benefits for cognitive symptoms as well as visual hallucination in dementia due to Lewy body disease and Parkinson's disease

SSRI and Trazodone are found to be useful in Frontotemporal dementia

Lorazepam or Clonazepam and Melatonin are found to be useful for REM sleep behavioural disorder in dementia due to Lewy body disease.

Patients with Vascular dementia needs treatment with medications for risk factors like diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia etc

Cholinesterase inhibitors can be tried in patients with mixed dementia if Alzheimer's disease is co-existent with other types of dementia

Other Somatic treatments

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) can be considered for severe depression in patients with dementia.

ECT can be considered for those with dementia having very severe agitation and aggression that are non-responsive to other treatments

Non-invasive brain stimulation like Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) have no clear evidence of effectiveness in patients with dementia.

Pharmacological Treatment of Mild Cognitive Impairment

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)is the high-risk state for dementia with significantly increased risk for conversion to dementia compared to those with normal cognition.

Disease modifying drugs for dementia are expected to be more effective in the stage of MCI compared to the stage of dementia. However no effective medication has been identified for MCI

Acetyl Cholinesterase inhibitorsand Memantine have not been found to be effective in delaying the conversion of MCI to dementia. Routine use of Cholinesterase inhibitors or Memantinefor the treatment of MCI is not recommended.

(Please see references 12-20 for further reading of pharmacological treatment)

Management of different phases of illnesses

The course of Dementia can be divided into three phases; mild, moderate and severe, based on the severity of cognitive symptoms and functional impirment. Symptoms like BPSD are more common in the mild to moderate phase where as the impairments in ADL predominate the severe phase. BPSD may not be present in all cases and may not be problematic in some. Mangement of BPSD is particularly important during the initial phases of the illness as this can have direct impact on the quality of life of the affected individual and the family members involved in care. Refer to the setion on management

Special Issues in the management of Dementia

1. Delirium Superimposed on Dementia

When to suspect ?

Older people with dementia have high risk of development delirium. Both hypoactive and hyperactive delirium can occur, but hypoactive delirium is more likely. Any sudden deterioration in sensorium, activity level, behaviour should alert the possibility of superimposed delirium. It will be be associated with disturbance in sleep wake cycle and could also take the form of increased sleepiness.

How to manage?

The management should involve attempts to identify multiple causes which usually contribute to development and persistence of delirium. Once identified these factors may be addressed and the condition be monitored. Disappearance of recent onset behavioural symptoms and improvement in cognitive functions over a period of days would usually be indicative of resolution of superimposed delirium

2. Management of Multi-morbidity.

Dementia is a major neuropsychiatric condition and long-term medical care. Multimorbidity is common among older people and people with dementia are no exception. Two strategies can help here. The first one is to evaluate the person in detail for presence of co-morbidity and sensory impairments. This can be done after making the diagnosis of dementia. Do enquire about the current management of each problem. You may include the management of the co-morbid conditions also into the follow-up plan. The second important strategy would be to be on the watch out for emergence of new problems like delirium or issues related falls, infections, cerebrovascular events etc. Prompt identification and early interventions can help to prevent or identify major eventsearly. Adherence to interventions is a matter of concern as this would be dependent on the caregivers. Communication with the caregivers will have to be simple and might need to be repeated. Try to speak to the primary caregivers directly and allow time for clarifications if they have doubts. Ask a family member to take up the responsibility of co-ordinating and monitoring home-based care and to report the progress during follow up visit. The primary caregiver is the ideal person to do this. Frequent changes in place/caregivers etc can create issues and is best avoided minimised. But resource limitations are frequent and providing more caregiver support during trying times can be a great help for families involved in dementia care

3. Risk of Falls/fractures:

Prevention of accidents/trauma particularly falls is important. Judicious modification of the home environment will help. An informed caregiver can discuss this and do the needful. Discussions with caregivers and other family members will allow innovations which will may suit the particular home setting. All falls increase the risk of fractures and a fracture hip can have a very negative outcome for an older person with dementia

4. Need to Link with Community-based ServicesIt would help if community outreach services like palliative care services or any other similar service can be linked to home-based dementia care

5. Use of diagnostic instruments/tools

Brief screening tests can be useful. This can help in eliciting key information and by making brief cognitive assessment. The ideal test would be sensitive and specific. It should be short, simple and user friendly. There are large number of tests available and that suggests that no one test is the best. Shorter tests may confirm a cognitive problem that needs to be evaluated, whereas longer tests contribute more to the diagnosis. There are many instruments useful to screen or find cases of dementia. See http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/evidence/dementia/q6/en/index.html for more details of the review. Details of useful tools are available at the website of Alzheimer's Association (https://www.alz.org/documents_custom/141209-CognitiveAssessmentToo-kit-final.pdf)

CONCLUSIONS

Caregiver support and non-pharmacological interventions to manage symptoms like BPSD are the main ingredients of dementia care. Psychosocial management forms the first line and shall be given to all with BPSD. Psychosocial interventions work best when it is contextualized to the socio-cultural environment and the setting of care. Family and professional caregivers should be considered as key collaborators. Provision of relevant information, education and seamless support to caregivers, will be very crucial in dementia care. There is unmet need for such help and guidance. The families engaged in the care of a person affected by dementia will benefit from such support and this is especially so there are behavioral symptoms which are difficult to mange in home setting Some may benefit from pharmacological interventions but this shall be provided under supervision and needs to be monitored.[1-20]

WEBSITES FOR FURTHER INFORMATION

https://www.alz.org/documents_custom/141209-CognitiveAssessment Too-kit-final.pdf

See Dementia Module of mhGAP Intervention Guide of WHO www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/mhGAP_intervention_guide_02/en/

https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2016/204/5/clinical-practice-guidelines-dementia-australiawww.ipa-online.org/- international psychogeriatric association

https://www.ipa-online.org/publications/guides-to-bpsd- IPA Complete Guides to Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)

RESOURCES FOR INFORMATION TO THE CAREGIVERS

Alzheimer's Disease International https://www.alz.co.uk/

Alzheimers and Related Diseases Society of India https://www.ardsi.org/

WEBSITES FOR FURTHER INFORMATION

https://www.alz.org/documents_custom/141209-CognitiveAssessmentToo-kit-final.pdf

See Dementia Module of mhGAP Intervention Guide of WHO www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/mhGAP_intervention_guide_02/en/

https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2016/204/5/clinical-practice-guidelinesdementia-australiawww.ipa-online.org/- international psychogeriatricassociation

https://www.ipa-online.org/publications/guides-to-bpsd- IPA CompleteGuides to Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)

RESOURCES FOR INFORMATION TO THE CAREGIVERS

Alzheimer's Disease International https://www.alz.co.uk/

Alzheimers and Related Diseases Society of India https://www.ardsi.org/

REFERENCES

- 1.Stewart R. Mild cognitive impairment--the continuing challenge of its “real-world” detection and diagnosis. Arch.Med.Res. 2012;43(8):609–14. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tripathi M, Vibha D. Reversible dementias. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;51(Suppl 1):S52–5. PubMed PMID: 21416018; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3038529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. PubMed PMID: 1202204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathuranath PS, Nestor PJ, Berrios GE, Rakowicz W, Hodges JR. A brief cognitive test battery to differentiate Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2000 doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000434309.85312.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fillenbaum GG, Chandra V, Ganguli M, et al. Development of an activities of daily living scale to screen for dementia in an illiterate rural older population in India. Age Ageing. 1999;28:161–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, Ferris SH, Franssen E, Georgotas A. Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKeith IG, Boeve BF. Dickson DWet al Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017 Jul 4;89(1):88–100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. 5th edition. Arlington, VA: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson Kertesz, Robert P. H, Albert M, Boone K, Miller B. L, Cummings J, Neary D. F. D, Snowden J. S, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M. A. F Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farooq M. U, Min J, Goshgarian C, Gorelick P. B. Pharmacotherapy for Vascular Cognitive Impairment. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):759–776. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0459-3. doi:10.1007/s40263-017-0459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kales H. C, Gitlin L. N, Lyketsos C. G. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h369. doi:101136/bmj.h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi H, Ohnishi T, Nakagawa R, Yoshizawa K. The comparative efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(8):892–904. doi: 10.1002/gps.4405. doi:10.1002/gps.4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda S. G, Huntley J, Ames D, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsunaga S, Kishi T, Iwata N. Combination therapy with cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;18(5) doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu115. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyu115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brien J. T, Holmes C, Jones M, Jones R, Livingston G, McKeith I, Burns A. Clinical practice with anti-dementia drugs: A revised (third) consensus statement from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31(2):147–168. doi: 10.1177/0269881116680924. doi:10.1177/0269881116680924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien J. T, Thomas A. Vascular dementia. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1698–1706. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00463-8. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stinton C, McKeith I, Taylor J. Pharmacological Management of Lewy Body Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):731–742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121582. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker Z, Possin K. L, Boeve B. F, Aarsland D. Lewy body dementias. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1683–1697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00462-6. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00462-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]