Abstract

Located at 6q22–23, Ccn6 (WISP3) encodes for a matrix-associated protein of the CCN family, characterized by regulatory, rather than structural, roles in development and cancer. CCN6, the least studied member of the CCN family, shares the conserved multimodular structure of CCN proteins, as well as their tissue and cell-type specific functions. In the breast, CCN6 is a critical regulator of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions (EMT) and tumor initiating cells. Studies using human breast cancer tissue samples demonstrated that CCN6 messenger RNA and protein are expressed in normal breast epithelia but reduced or lost in aggressive breast cancer phenotypes, especially inflammatory breast cancer and metaplastic carcinomas. Metaplastic carcinomas are mesenchymal-like triple negative breast carcinomas, enriched for markers of EMT and stemness. RNAseq analyses of the TCGA Breast Cancer cohort show reduced CCN6 expression in approximately 50% of metaplastic carcinomas compared to normal breast. Our group identified frameshift mutations of Ccn6 in a subset of human metaplastic breast carcinoma. Importantly, conditional, mammary epithelial-cell specific ccn6 (wisp3) knockout mice develop invasive high-grade mammary carcinomas that recapitulate human spindle cell metaplastic carcinomas, demonstrating a tumor suppressor function for ccn6. Our studies on CCN6 functions in metaplastic carcinoma highlight the potential of CCN6 as a novel therapeutic approach for this specific type of breast cancer.

Keywords: Metaplastic, Spindle cell, Epithelial to mesenchymal, EMT, CCN6, WISP3, Breast cancer, Stem cells, Knockout mouse, MMTV-cre

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy and a leading cause of cancer-related death in women in the world. However, the events leading to cancer initiation and progression are still not fully understood, and there still is no cure for the ~20% of patients with distant metastasis. Studies have demonstrated that invasive carcinomas of the breast constitute a heterogeneous group of malignancies with different invasive and metastatic abilities. This heterogeneity is evident by different gene expression patterns, various histological morphologies under the light microscope, and different clinical behaviors and treatment responses.

The histopathological classification of invasive breast carcinomas depends on their degree of differentiation, which reflects how closely a tumor forms glandular structures and the cellular pleomorphism (Tavassoli 1992). Most invasive carcinomas of the breast are ductal, accounting for approximately 80% of tumors. Invasive lobular carcinomas account for 10–15% of all breast cancers, and the remainder constitute special histological types including metaplastic carcinoma, and others. The development of molecular classifications based on gene expression profiling demonstrated that breast carcinomas may be subclassified as luminal A, luminal B, HER2, and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) subtypes, which includes the mesenchymal and mesenchymal-stem like groups with the histological features of metaplastic carcinomas (Hennessy et al. 2009; Perou et al. 1999; 2000; Pollack et al. 1999).

Metaplastic breast carcinomas are a subtype of TNBC defined by the presence of glandular and non-glandular components (Devilee 2003; Rakha et al. 2015; Turner and Reis-Filho 2006). The non-glandular component results most of the times from mesenchymal differentiation and includes cells with spindle, osseous, or cartilaginous features. Metaplastic carcinomas constitute ~1.5% of all breast cancers, and up to 14% of tumors in African and African-American women (Abouharb and Moulder 2015; Pang et al. 2012). These tumors do not respond well to conventional chemotherapy, and with the exception of the low-grade fibromatosis-like subtype, metaplastic carcinomas have a higher propensity for metastasis compared to other TNBC, with a 5-year overall survival is 54% versus 73%, respectively (Song et al. 2013). Understanding the pathobiology of metaplastic carcinomas is critical to develop new and effective treatments.

Metaplasia is the reversible change in which one adult cell type is replaced by another adult cell type, and it is currently thought to arise from genetic reprogramming of stem cells. A mechanism by which cells may undergo metaplasia during tumorigenesis is through an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). Through this process, tumor cells acquire molecular and phenotypic changes resulting in spindle morphology and dysfunctional cell-cell adhesion, leading to invasion and metastasis (Hugo et al. 2007; Peinado et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2004). EMT was shown to induce the acquisition of breast cancer stem cell properties (Mani et al. 2008). One of the most frequent molecular alterations in the EMT process is the loss of membranous E-cadherin, which facilitates cell detachment (Hugo et al. 2007; Peinado et al. 2007). Metaplastic carcinomas are characterized by reduced or negative E-cadherin expression. Recent genomic analyses showed that metaplastic carcinomas harbor TP53 mutations and frequent PI3K and Wnt pathway gene alterations, including mutations (Badve et al. 2011; Hennessy et al. 2009; Ng et al. 2017; Turner and Reis-Filho 2006; Turner et al. 2007). Our laboratory has demonstrated that a subset of human metaplastic carcinomas harbor CCN6 (WISP3) frameshift mutations (Hayes et al. 2008). Here, we will present the body of evidence implicating the matricellular protein CCN6 (WISP3) in the pathogenesis of metaplastic carcinomas, and discuss the mechanisms of CCN6-mediated tumor suppressor function.

The matricellular protein CCN6 (WISP3)

The CCN family consists of six matrix-associated signaling modulators - CCN1 (Cyr61), CCN2 (CTGF), CCN3 (Nov), CCN4 (WISP1), CCN5 (WISP2), and CCN6 (WISP3) (Jun and Lau 2011; Perbal et al. 2003; Perbal 2004, 2005, 2006). The CCN family members are cysteine rich, glycosylated proteins that are secreted and modulate multiple functions in development and disease (Jun and Lau 2011; Kubota and Takigawa 2013). They share a secretory signal peptide at the N-terminus, which facilitates their extracellular localization (Perbal 2001; Yang and Lau 1991). The signal peptide is followed by four highly conserved functional domains: the insulin-like growth factor binding domain (IGFBP) which contains the IGF binding consensus sequence (GCGCCXXC), the Von Willebrand factor type C repeat (VWC) domain, the thrombospondin type-1 repeat (TSP-1) that binds a wide range of extracellular targets such as TGF-β, integrins, and collagen V, and the cysteine knot (CT) domain that also exists in the structure of several TGF-β family members (Bork 1993; Lau 2016). The IGFBP and VWC domains are connected to the TSP and CT domains via a variable ‘hinge’ region (Byun et al. 2001; Grotendorst and Duncan 2005; Holbourn et al. 2008; Imai et al. 2000; Yang and Lau 1991). Despite the strong similarities in protein sequence and structure, CCN family members can display similar functions as well as opposite roles in carcinogenesis. In breast cancer, CCN1 and CCN2 mainly act as oncoproteins while CCN5 and CCN6 are known for their tumor suppressive roles (reviewed in (Kleer 2016)).

CCN6 mutations were reported in patients with progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia, and deregulated expression of CCN6 was found in colon and in inflammatory breast cancer (Hurvitz et al. 1999; Pennica et al. 1998; van Golen et al. 1999). Genomic studies showed that the chromosome arm 6q, where Ccn6 is located, frequently presented allelic imbalance in human breast cancer (Chappell et al. 1997; Fujii et al. 1996; Rodriguez et al. 2000). Interestingly, sequencing of human metaplastic carcinoma tissue samples discovered a frameshift mutation in Ccn6 (Hayes et al. 2008), suggesting a causal tumor suppressor role for CCN6.

CCN6 restrains breast cancer growth and metastasis through regulation of cancer cell plasticity

Similar to human tissue samples, CCN6 expression is low in metastasizing breast cancer cell lines with spindled morphology, compared to non-tumorigenic breast cells. Our studies demonstrated that ectopic expression of CCN6 in aggressive breast cancer cell lines with low CCN6 expression reduced growth and invasion in vitro, and tumor volume and metastasis in vivo (Huang et al. 2010; 2016; Kleer et al. 2002; Lorenzatti et al. 2011; Pal et al. 2012a; Zhang et al. 2005). The most striking data from these experiments were the profound morphological change induced by CCN6 in breast cancer cells, and a significant reduction in tumor initiating cells compared to controls.

Ectopic CCN6 overexpression in triple negative spindled breast cancer cell lines changed their morphology towards better-differentiated epithelial cells compared to controls (Huang et al. 2010; Pal et al. 2012a, b). These changes were observed in vitro and in vivo, and were associated with a gene and protein expression pattern characteristic of a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition with upregulation of cytokeratin 18, E-cadherin, downregulation of the mesenchymal marker vimentin, and reduction of EMT transcription factors ZEB1, Slug, and Snail (Huang et al. 2008, 2016; Lorenzatti et al. 2011). Consistent with these observations, CCN6 shRNA downregulation in non-tumorigenic breast cells induced a bona fide EMT in two and three dimensional culture systems, morphologically and at the protein and gene expression levels, and triggered a highly invasive and motile phenotype (Huang et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2005).

The mechanistic and functional connection between EMT and stemness has been well-established in development and in cancer (Mani et al. 2008; Polyak and Weinberg 2009). The strong effect of CCN6 on epithelial cell morphology led us to hypothesize that CCN6 may also be a regulator of stemness in breast cancer. Indeed, our studies indicate that ectopic CCN6 overexpression in triple negative invasive breast cancer cells reduced the number of tumor initiating cells and reduced their ability to form tumors in limiting dilution studies in vivo (Huang et al. 2016). In these experiments, we identified that CCN6 inhibited a NOTCH1/Slug axis to reduce breast cancer tumor initiating cell populations. Taken together, studies demonstrate that CCN6 is a central regulator of breast cancer cell plasticity, which links epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions and tumor initiating cells.

CCN6 is a secreted matrix-associated protein that modulates growth factor signaling pathways

CCN6, similar to other CCN family members, is secreted in the extracellular medium. CCN6 was detected in the conditioned medium of breast cancer cells with ectopic CCN6 overexpression. Studies demonstrated that CCN6 containing conditioned media was able to suppress proliferation and growth of breast cancer cells (Kleer et al. 2004). Similarly, human recombinant CCN6 protein was sufficient to reduce breast cancer growth and invasion compared to vehicle treated cells (Pal et al. 2012a).

Despite efforts, a high affinity CCN-specific receptor has not been identified to date, studies have demonstrated that CCN proteins bind to integrins, including αvβ3, αvβ5, α5β1, α6β1, to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), growth factors, and receptors including NOTCH, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins (LRPs), and the cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P/IGF-2R) (recently reviewed in (Lau 2016)). The ability of CCN proteins to bind various receptors and signaling proteins may account for the context dependent and the multiple biological functions of CCNs. This ability also highlights the role of CCN proteins, including CCN6, as extracellular signaling regulatory hubs, which are attractive therapeutic targets.

While it remains an open question whether CCN6 binds to insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) or IGF receptors, extracellular CCN6 protein has been shown to interfere with IGF signaling in breast cancer cells to reduce proliferation and invasion. Studies have showed that CCN6 containing conditioned medium blocked the growth and invasion promoting effects of IGF1 and reduced IGF-mediated activation of IGF-1R, pERK1/2, pAKT1, and pIRS1 in aggressive breast cancer cells (Kleer et al. 2004). Concordantly, another study in an immortalized human mammary epithelial cell line, HME, using the knock-down approach showed that inhibition of CCN6 expression promoted anchorage dependent/independent growth and enhanced the growth effect of IGF-I (Zhang et al. 2005). More recently, our group uncovered a link between secreted CCN6 and EMT regulators by demonstrating that CCN6 inhibited the effects of IGF-1 on ZEB1 upregulation in breast cancer cells (Lorenzatti et al. 2011).

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is a well-known EMT inducer (Barcellos-Hoff and Akhurst 2009; de Caestecker et al. 2000). Using co-immunoprecipitation and surface plasmon resonance, our group has discovered that CCN6 binds directly and with high affinity to BMP4, a member of the TGF-β superfamily (Pal et al. 2012b). Development of domain specific CCN6 deletion mutants, we identified that the TSP domain is required for BMP4 binding, and for the invasion inhibitory function of CCN6 in triple negative breast cancer cells. These studies led to the discovery that CCN6-BMP4 binding reduces BMP4 signaling through p-38/TAK1 pathway, leading to reduced invasion and migration of breast cancer cells. In addition to BMP4, Pal et al. found that CCN6 regulates the expression of type III TGF-β receptor (TβRIII), hence, controls the expression of α6 integrin and E-cadherin, maintains the apical-basal polarity and preserves the acinar organization in 3D cultures (Pal et al. 2012b). The inverse correlation between CCN6, BMP4, and TβRIII protein expression was also evident in human breast cancer tissue samples (Pal et al. 2012a, b). Collectively, these data demonstrate that CCN6 is an extracellular regulator of several important growth factor signaling pathways including BMP4 and IGF, and that CCN6 modulates their tumor promoting effects on the breast epithelium.

CCN6 emerges as a tumor suppressor for high-grade spindle metaplastic carcinomas of the breast

Global deletion and overexpression mouse models were previously developed to investigate the role of CCN6 in skeletal alterations, with no discernible phenotype (Kutz et al. 2005; Nakamura et al. 2009). To define the role of CCN6 in mammary gland development and tumorigenesis, our lab has generated a conditional, mammary epithelial cell-specific Ccn6 knockout mouse model (Martin et al. 2017). Using Cre/loxp-mediated recombination, we specifically inactivated the Ccn6 gene in the mammary epithelium, by intercrossing the floxed Ccn6 mice with the MMTV-Cre mice. The offspring were genotyped using primers specific for various Ccn6 alleles (i.e. floxed, wild-type, and deleted) and with primers specific for Cre.

Underscoring the relevance of earlier studies in cell lines and in xenograft models which demonstrate that CCN6 regulates EMT and cell plasticity, Ccn6fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mice developed invasive mammary carcinomas with histopathological features and gene signatures resembling human spindle cell metaplastic breast carcinoma. Ccn6fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mice formed tumors with high frequency (72%) and all tumors that developed exhibited spindle metaplastic histology. Ccn6fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mammary tumors were highly aggressive with mitotically active spindle cells that invaded adjacent breast and skeletal muscle, and metastasized in 46% of the cases. The non-neoplastic mammary gland of Ccn6fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mice displayed a variety of histological abnormalities including secretory hyperplasia and atypical ductal hyperplasia, similar to the human counterparts.

The hypobranching phenotype and defects in ductal bifurcation observed during development of the mammary glands of Ccn6fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mice highlights a role for Ccn6 in mammary gland morphogenesis and may have implications for tumor initiation. It is interesting to note that a similar phenotype has been reported after deletion of classical tumor suppressors including Brca1 and Brca2 (Ferguson et al. 2012; McAllister et al. 2002; Xu et al. 1999). Because Ccn6-related tumorigenesis is characterized by an initial growth disadvantage it is not unexpected that tumor formation occurs after a long latency, as observed in Brca1 conditional knockout mice (Xu et al. 1999).

The observation that Ccn6fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mice mammary glands showed delayed age-related involution with residual terminal end buds and brown fat after 8 months of age may shed light into preneoplastic progression. Defective age-related involution with persistent brown adipose has been reported in mammary glands from adult Brca1 mutant mice prior to development of poorly differentiated carcinomas (Jones et al. 2011). Recent studies in human tissues showed that defective age-related lobular involution is significantly associated with increased risk for breast cancer (Milanese et al. 2006; Radisky and Hartmann 2009). In particular, postmenopausal women with delayed age-related involution have a 3-fold increased risk of breast cancer compared with women with normal involution (Milanese et al. 2006; Radisky and Hartmann 2009).

Ccn6fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mice mammary tumors also resemble human metaplastic carcinomas at the transcriptional level. Comparison of the expression profile of orthologous genes between mouse and human metaplastic carcinomas, resulted in a common 87-gene signature. Among the 87 shared genes (10 up- and 77 are downregulated) were several that have been previously studied as markers of human metaplastic carcinoma including downregulated expression of Cdh1, Cldn3, Cldn4, and Krt19 (Hennessy et al. 2009; Koker and Kleer 2004; Rungta and Kleer 2012; Zhang et al. 2012). These studies also uncovered genes that have not been considered in this context previously. Among the top upregulated genes were Hmga2, Igfbp2, and Hbegf. Hmga2 (high mobility group AT-hook 2) was previously reported to promote EMT and metastasis by activating the TGFβ receptor II signaling (Morishita et al. 2013). Igf2bp2 (p62/IMP2), a member of the family of insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding proteins, is regulated through activation of IGF receptors, and promotes breast cancer cell migration and reduces adhesion in TNBC cells (Li et al. 2015). Hbegf (heparin binding EGF-like growth factor) induces breast cancer intravasation and metastasis (Zhou et al. 2014). Among the most significantly shared downregulated genes were Foxa1, Spint1 and 2, and Ddr1. Foxa1 is an important regulator of the ERα and the androgen receptor, whose silencing increases invasion and induces an aggressive, basal-like breast cancer phenotype (Bernardo and Keri 2012). Spint 1 and 2 (hepatocyte growth factor activation inhibitors HAI-1 and HAI-2) are potent matriptase inhibitors reducing invasion and metastasis in TNBC (Parr and Jiang 2006). The Discoidin Domain Receptor 1 (Ddr1), a collagen-binding receptor tyrosine kinase, is associated with worse survival in women with TNBC (Toy et al. 2015).

Conclusion and perspective

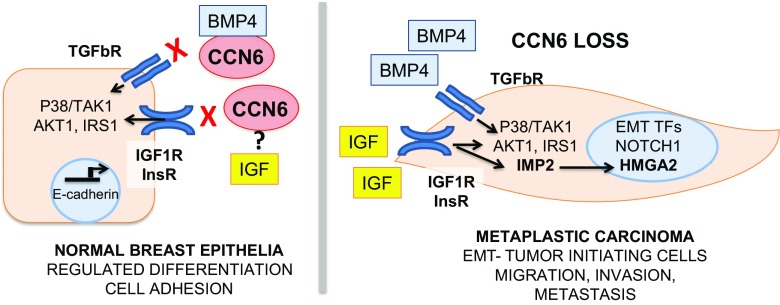

CCN6, the least studied member of the CCN protein family, is a powerful regulator of breast tumorigenesis. Loss of CCN6 gives rise to one of the most lethal forms of invasive breast cancer, spindle metaplastic carcinomas. Further studies are needed to understand how extracellular CCN6 regulates EMT and cancer cell plasticity, which are the critical CCN6 protein domains responsible for the tumor suppressor function, and elucidate novel CCN6 binding partners and receptors that transmit CCN6 extracellular tumor suppressor signals into breast epithelia. Our current working hypothesis is illustrated in Fig. 1. The recent development of Ccn6fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mice, a unique mouse model of spindle metaplastic carcinoma, will accelerate the discovery of disease drivers and biomarkers, and enable testing new therapies against these aggressive tumors.

Fig. 1. Working hypothesis on the tumor suppressor function of CCN6 in breast cancer.

CCN6 is secreted from normal breast epithelial cells and regulates the epithelial cell phenotype and differentiation by modulating the growth and invasion promoting effects of BMP4 and IGF. CCN6 loss, due to mutations or other mechanisms, results in deregulated BMP4 and IGF signaling, with increased p-38/TAK1 activation, and activation of IRS1 and AKT1. Our recent studies demonstrate that CCN6 loss results in upregulated expression of IMP2/IGF2BP2 and the architectural transcription factor HMGA2, two oncofetal proteins involved in IGF and TGF-β signaling that are upregulated in aggressive cancers and are important inducers of EMT and invasion. At least in part through these mechanisms, CCN6 loss leads to EMT and increased tumor initiating cells and to the development of spindle metaplastic carcinomas

Funding

This work was supported by NIH/NCI grant R01CA125577 to CGK.

References

- Abouharb S, Moulder S. Metaplastic breast cancer: clinical overview and molecular aberrations for potential targeted therapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2015;17:431. doi: 10.1007/s11912-014-0431-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badve S, Dabbs DJ, Schnitt SJ, Baehner FL, Decker T, Eusebi V, Fox SB, Ichihara S, Jacquemier J, Lakhani SR, et al. Basal-like and triple-negative breast cancers: a critical review with an emphasis on the implications for pathologists and oncologists. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:157–167. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos-Hoff MH, Akhurst RJ. Transforming growth factor-beta in breast cancer: too much, too late. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:202. doi: 10.1186/bcr2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo GM, Keri RA. FOXA1: a transcription factor with parallel functions in development and cancer. Biosci Rep. 2012;32:113–130. doi: 10.1042/BSR20110046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork P. The modular architecture of a new family of growth regulators related to connective tissue growth factor. FEBS Lett. 1993;327:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80155-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun D, Mohan S, Baylink DJ, Qin X. Localization of the IGF binding domain and evaluation of the role of cysteine residues in IGF binding in IGF binding protein-4. J Endocrinol. 2001;169:135–143. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell SA, Walsh T, Walker RA, Shaw JA. Loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 6q in preinvasive and early invasive breast carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1324–1329. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Caestecker MP, Piek E, Roberts AB. Role of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cancer (In Process Citation) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1388–1402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.17.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilee FTAP, editor. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the breast and female genital organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BW, Gao X, Kil H, Lee J, Benavides F, Abba MC, Aldaz CM. Conditional Wwox deletion in mouse mammary gland by means of two Cre recombinase approaches. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Zhou W, Gabrielson E. Detection of frequent allelic loss of 6q23-q25.2 in microdissected human breast cancer tissues. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 1996;16:35–39. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199605)16:1<35::AID-GCC5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotendorst GR, Duncan MR. Individual domains of connective tissue growth factor regulate fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation. FASEB J. 2005;19:729–738. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3217com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MJ, Thomas D, Emmons A, Giordano TJ, Kleer CG. Genetic changes of Wnt pathway genes are common events in metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4038–4044. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, Gilcrease MZ, Krishnamurthy S, Lee JS, Fridlyand J, Sahin A, Agarwal R, Joy C, et al. Characterization of a naturally occurring breast cancer subset enriched in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stem cell characteristics. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4116–4124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbourn KP, Acharya KR, Perbal B. The CCN family of proteins: structure-function relationships. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:461–473. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Zhang Y, Varambally S, Chinnaiyan AM, Banerjee M, Merajver SD, Kleer CG. Inhibition of CCN6 (Wnt-1-induced signaling protein 3) down-regulates E-cadherin in the breast epithelium through induction of snail and ZEB1. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:893–904. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Gonzalez ME, Toy KA, Banerjee M, Kleer CG. Blockade of CCN6 (WISP3) activates growth factor-independent survival and resistance to anoikis in human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3340–3350. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Martin EE, Burman B, Gonzalez ME, Kleer CG. The matricellular protein CCN6 (WISP3) decreases Notch1 and suppresses breast cancer initiating cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:25180–25193. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo H, Ackland ML, Blick T, Lawrence MG, Clements JA, Williams ED, Thompson EW. Epithelial--mesenchymal and mesenchymal--epithelial transitions in carcinoma progression. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:374–383. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurvitz JR, Suwairi WM, Van Hul W, El-Shanti H, Superti-Furga A, Roudier J, Holderbaum D, Pauli RM, Herd JK, Van Hul EV, et al. Mutations in the CCN gene family member WISP3 cause progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia. Nat Genet. 1999;23:94–98. doi: 10.1038/12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Moralez A, Andag U, Clarke JB, Busby WH, Jr, Clemmons DR. Substitutions for hydrophobic amino acids in the N-terminal domains of IGFBP-3 and -5 markedly reduce IGF-I binding and alter their biologic actions. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18188–18194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LP, Buelto D, Tago E, Owusu-Boaitey KE (2011) Abnormal mammary adipose tissue environment of brca1 mutant mice show a persistent deposition of highly vascularized multilocular adipocytes. J Cancer Sci Ther (Suppl 2):004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jun JI, Lau LF. Taking aim at the extracellular matrix: CCN proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:945–963. doi: 10.1038/nrd3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleer CG. Dual roles of CCN proteins in breast cancer progression. J Cell Commun Signal. 2016;10:217–222. doi: 10.1007/s12079-016-0345-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleer CG, Zhang Y, Pan Q, van Golen KL, Wu ZF, Livant D, Merajver SD. WISP3 is a novel tumor suppressor gene of inflammatory breast cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:3172–3180. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleer CG, Zhang Y, Pan Q, Merajver SD. WISP3 (CCN6) is a secreted tumor-suppressor protein that modulates IGF signaling in inflammatory breast cancer. Neoplasia. 2004;6:179–185. doi: 10.1593/neo.03316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koker MM, Kleer CG. p63 expression in breast cancer: a highly sensitive and specific marker of metaplastic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1506–1512. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000138183.97366.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota S, Takigawa M. The CCN family acting throughout the body: recent research developments. Biomol Concepts. 2013;4:477–494. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2013-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutz WE, Gong Y, Warman ML. WISP3, the gene responsible for the human skeletal disease progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia, is not essential for skeletal function in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:414–421. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.414-421.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LF. Cell surface receptors for CCN proteins. J Cell Commun Signal. 2016;10:121–127. doi: 10.1007/s12079-016-0324-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Francia G, Zhang JY. p62/IMP2 stimulates cell migration and reduces cell adhesion in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32656–32668. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzatti G, Huang W, Pal A, Cabanillas AM, Kleer CG. CCN6 (WISP3) decreases ZEB1-mediated EMT and invasion by attenuation of IGF-1 receptor signaling in breast cancer. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1752–1758. doi: 10.1242/jcs.084194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin EE, Huang W, Anwar T, Arellano-Garcia C, Burman B, Guan JL, Gonzalez ME, Kleer CG. MMTV-cre;Ccn6 knockout mice develop tumors recapitulating human metaplastic breast carcinomas. Oncogene. 2017;36:2275–2285. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister KA, Bennett LM, Houle CD, Ward T, Malphurs J, Collins NK, Cachafeiro C, Haseman J, Goulding EH, Bunch D, et al. Cancer susceptibility of mice with a homozygous deletion in the COOH-terminal domain of the Brca2 gene. Cancer Res. 2002;62:990–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanese TR, Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Vierkant RA, Maloney SD, Pankratz VS, Degnim AC, Vachon CM, Reynolds CA, et al. Age-related lobular involution and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1600–1607. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita A, Zaidi MR, Mitoro A, Sankarasharma D, Szabolcs M, Okada Y, D'Armiento J, Chada K. HMGA2 is a driver of tumor metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4289–4299. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Cui Y, Fernando C, Kutz WE, Warman ML. Normal growth and development in mice over-expressing the CCN family member WISP3. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0040-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CKY, Piscuoglio S, Geyer FC, Burke KA, Pareja F, Eberle CA, Lim RS, Natrajan R, Riaz N, Mariani O, et al. The landscape of somatic genetic alterations in metaplastic breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3859–3870. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal A, Huang W, Li X, Toy KA, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Kleer CG. CCN6 modulates BMP signaling via the smad-independent TAK1/p38 pathway, acting to suppress metastasis of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4818–4828. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal A, Huang W, Toy KA, Kleer CG. CCN6 knockdown disrupts acinar organization of breast cells in three-dimensional cultures through up-regulation of type III TGF-beta receptor. Neoplasia. 2012;14:1067–1074. doi: 10.1593/neo.121322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J, Toy KA, Griffith KA, Awuah B, Quayson S, Newman LA, Kleer CG. Invasive breast carcinomas in Ghana: high frequency of high grade, basal-like histology and high EZH2 expression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2055-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr C, Jiang WG. Hepatocyte growth factor activation inhibitors (HAI-1 and HAI-2) regulate HGF-induced invasion of human breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1176–1183. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennica D, Swanson TA, Welsh JW, Roy MA, Lawrence DA, Lee J, Brush J, Taneyhill LA, Deuel B, Lew M, et al. WISP genes are members of the connective tissue growth factor family that are up-regulated in wnt-1-transformed cells and aberrantly expressed in human colon tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14717–14722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. NOV (nephroblastoma overexpressed) and the CCN family of genes: structural and functional issues. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:57–79. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.2.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. CCN proteins: multifunctional signalling regulators. Lancet. 2004;363:62–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal BATM. CCN proteins: a new family of cell growth and differentiation regulators. London: World Scientific Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. The CCN3 protein and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;587:23–40. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-5133-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B, Brigstock DR, Lau LF. Report on the second international workshop on the CCN family of genes. Mol Pathol. 2003;56:80–85. doi: 10.1136/mp.56.2.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM, Jeffrey SS, van de Rijn M, Rees CA, Eisen MB, Ross DT, Pergamenschikov A, Williams CF, Zhu SX, Lee JC, et al. Distinctive gene expression patterns in human mammary epithelial cells and breast cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9212–9217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack JR, Perou CM, Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Pergamenschikov A, Williams CF, Jeffrey SS, Botstein D, Brown PO. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy-number changes using cDNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 1999;23:41–46. doi: 10.1038/14385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radisky DC, Hartmann LC. Mammary involution and breast cancer risk: transgenic models and clinical studies. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14:181–191. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9123-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakha EA, Tan PH, Varga Z, Tse GM, Shaaban AM, Climent F, van Deurzen CH, Purnell D, Dodwell D, Chan T, et al. Prognostic factors in metaplastic carcinoma of the breast: a multi-institutional study. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:283–289. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C, Causse A, Ursule E, Theillet C. At least five regions of imbalance on 6q in breast tumors, combining losses and gains. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2000;27:76–84. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(200001)27:1<76::AID-GCC10>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rungta S, Kleer CG. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast: diagnostic challenges and new translational insights. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:896–900. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0166-CR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Liu X, Zhang G, Song H, Ren Y, He X, Wang Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Sun S, et al. Unique clinicopathological features of metaplastic breast carcinoma compared with invasive ductal carcinoma and poor prognostic indicators. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:129. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli FA (1992) Classification of metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. Pathol Annu 27:89–119 [PubMed]

- Toy KA, Valiathan RR, Nunez F, Kidwell KM, Gonzalez ME, Fridman R, Kleer CG. Tyrosine kinase discoidin domain receptors DDR1 and DDR2 are coordinately deregulated in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:9–18. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS. Basal-like breast cancer and the BRCA1 phenotype. Oncogene. 2006;25:5846–5853. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS, Russell AM, Springall RJ, Ryder K, Steele D, Savage K, Gillett CE, Schmitt FC, Ashworth A, et al. BRCA1 dysfunction in sporadic basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2126–2132. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Golen LK, Davies S, Wu ZF, Wang Y, Bucana CD, Root H, Chandrasekharappa S, Strawderman M, Ethier SP, Merajver SD (1999) A novel putative low-affinity insulin-like growth factor-binding protein, LIBC (lost in inflammatory breast cancer), and RhoC GTPase correlate with the inflammatory breast cancer phenotype. Clin Cancer Res 5:2511–2519 [PubMed]

- Xu X, Wagner KU, Larson D, Weaver Z, Li C, Ried T, Hennighausen L, Wynshaw-Boris A, Deng CX. Conditional mutation of Brca1 in mammary epithelial cells results in blunted ductal morphogenesis and tumour formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:37–43. doi: 10.1038/8743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang GP, Lau LF. Cyr61, product of a growth factor-inducible immediate early gene, is associated with the extracellular matrix and the cell surface. Cell Growth Differ. 1991;2:351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Pan Q, Zhong H, Merajver SD, Kleer CG. Inhibition of CCN6 (WISP3) expression promotes neoplastic progression and enhances the effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 on breast epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R1080–R1089. doi: 10.1186/bcr1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Toy KA, Kleer CG. Metaplastic breast carcinomas are enriched in markers of tumor-initiating cells and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:178–184. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BP, Deng J, Xia W, Xu J, Li YM, Gunduz M, Hung MC. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3beta-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:931–940. doi: 10.1038/ncb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZN, Sharma VP, Beaty BT, Roh-Johnson M, Peterson EA, Van Rooijen N, Kenny PA, Wiley HS, Condeelis JS, Segall JE. Autocrine HBEGF expression promotes breast cancer intravasation, metastasis and macrophage-independent invasion in vivo. Oncogene. 2014;33:3784–3793. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]