Abstract

Uterine perforation during hysteroscopic operative procedures is a potential complication well known to gynaecologists. Uterine septa are a commonly encountered Müllerian anomaly related to pregnancy loss and infertility. Hysteroscopic resection of septa has shown to improve pregnancy outcome. There are limited case reports of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies after hysteroscopic septal resection. Our patient had a hysteroscopic septal resection done a year prior which was complicated by a uterine fundal perforation, left to spontaneously heal after immediate sealing with cautery. The patient conceived spontaneously soon after and underwent an emergency caesarean section for severe pre-eclampsia. Intraoperatively, after removal of the placenta, we discovered a 3 cm symmetrical circular defect at the fundus of the uterus with no myometrium or serosa. The potentially disastrous consequences of this silent uterine rupture were mitigated due to another life-threatening condition which prevented the onset of labour.

Keywords: pregnancy, reproductive medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology, surgery

Background

Operative hysteroscopy has become the standard of care for uterine anomalies like adhesions, septa, submucous myomas and polyps.1 The incidence of uterine perforation during hysteroscopic surgeries is reported to be 1% to 2%.2

Uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies is being increasingly reported after hysteroscopy through case reports. Some of the risk factors for subsequent rupture appear to be the use of monopolar cautery during septal resection and the occurrence of uterine perforation. Due to limited studies, it cannot be ascertained whether this risk is due to the congenitally weakened uterus or due to operative intervention. This case reiterates the risks of uterine rupture in pregnancies following septal resection.

Case history

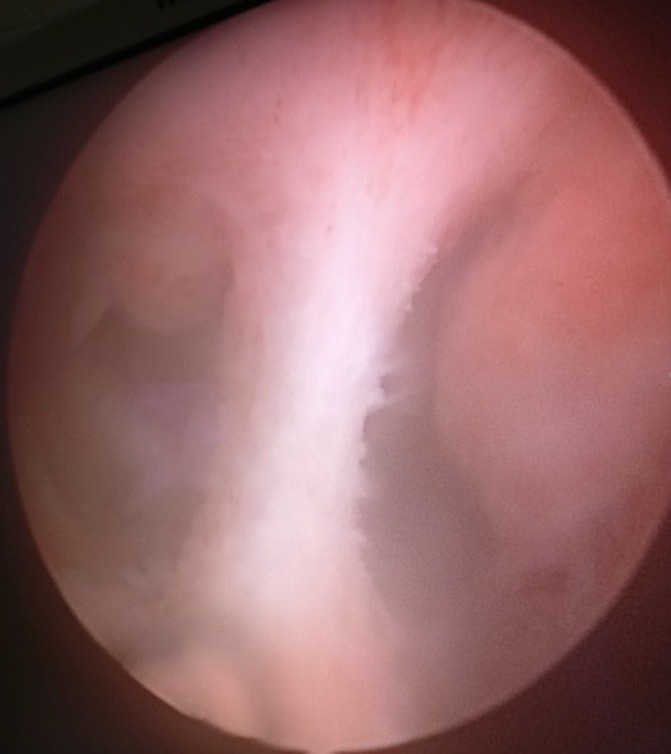

Our patient, aged 29 years, was a case of complex congenital heart disease with persistent ductus arteriosus corrected by two surgeries at 6 months and 2 years of age. She had a prior history of irregular menstrual cycles and primary infertility for 2 years, on the evaluation of which she was found to have a complete uterine septum (figure 1) extending from fundus to cervix. She underwent a hysteroscopic septal resection a year ago, using a resectoscope (monopolar cautery). The surgery was complicated by perforation of the uterus at the fundus, <0.5 cm, which was sealed using bipolar cautery and left to spontaneously heal. Our patient also had postoperative complication of the lower limb deep vein thrombosis which required embolectomy and thereafter anticoagulant therapy with warfarin.

Figure 1.

Hysteroscopic view of complete uterine septum.

She was not followed up postoperatively with ultrasonography, hysterosalpingography or relook hysteroscopy. She conceived spontaneously 2 months after the procedure, and due to the irregularity of her menstrual cycles, her pregnancy was detected at 5 months gestation, with warfarin having been taken throughout. The level II ultrasound was suggestive of corpus callosum agenesis. Her early pregnancy was uneventful.

Her placenta was found to be fundo-anterior in location on ultrasonography done in the 32nd week for growth parameters.

Treatment

At 35 weeks gestation, she was admitted for pre-eclampsia, started on labetalol and switched over from warfarin to heparin. At 36+3 weeks gestation, she developed severe pre-eclampsia with blood pressure exceeding 180/110 mm Hg and was started on magnesium sulfate infusion.

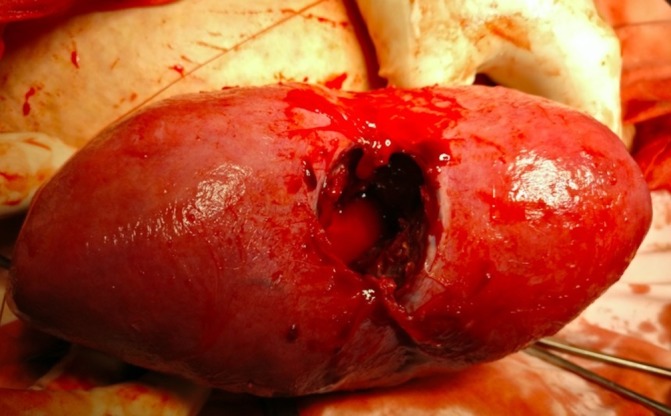

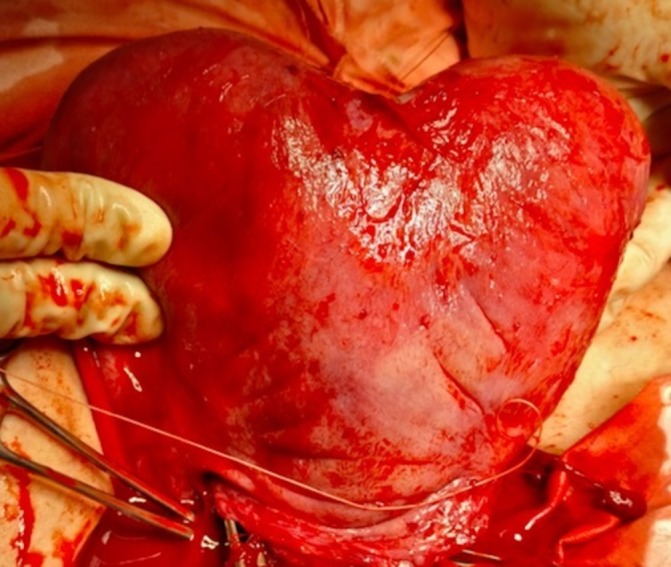

We performed an emergency lower segment caesarean section. Intraoperatively, the baby was transverse in presentation with an Apgar score of 9/8. The placenta was fundo-anterior and delivered uneventfully with no evidence of abruption or adherence. The uterus was exteriorised due to persistent bleeding and so we noticed a perforation at the fundus, approximately 3 cm in diameter, symmetrical, with no myometrium or serosa (figure 2). This was a case of a spontaneous uterine rupture which could have occurred in the antenatal period or intraoperatively. Although the uterine anomaly was classified as septate during laparoscopy, it appeared like a bicornuate uterus during caesarean section (figure 3), according to the European classification.

Figure 2.

Symmetrical circular uterine fundal defect created by expansion of perforation during septal resection. There is no myometrium or serosa in this area.

Figure 3.

The appearance of a uterine anomaly during pregnancy.

We repaired the defect by compressing the uterus anteriorly–posteriorly and suturing the edges with 1–0 vicryl (figure 4). There was considerable intraoperative haemorrhage of 2 L for which we gave a high dose of oxytocin infusion, rectal prostaglandin E1 and intramyometrial and intramuscular prostaglandin F2a, and performed bilateral uterine artery ligation. We packed the uterus with a roller gauze pulled out vaginally and inserted a pelvic drain.

Figure 4.

Uterine defect repaired by anterior–posterior apposition and suturing with 1–0 vicryl.

Our patient was stable in the postoperative period, and the uterine pack removed within 12 hours.

Outcome

This case report is unique in that one life-threatening condition, namely severe pre-eclampsia, necessitated an emergency caesarean section, which saved the patient and her baby from another life-threatening condition, namely uterine rupture. Had our patient gone into spontaneous labour, she could have gone into haemorrhagic shock with undiagnosed bleeding from the placenta into the peritoneal cavity via the defective segment of the uterus or extension of the existent defect. We can only hypothesise the outcomes which were assuaged by mere serendipity, as we had no prior suspicion for this possibility.

Postoperative period was uneventful, and our patient went home with a healthy baby girl 7 days later.

We could not perform tubal ligation (according to Indian law) or insert an intrauterine contraceptive device for fear of future perforation. We discharged the patient with the strict advice to avoid pregnancy due to risk of subsequent rupture.

Discussion

Uterine rupture after hysteroscopic septal resection is a rare but real risk. Myometrial damage is proposed to be the cause. This case shows that it is indeed myometrial thinning that leads to the risk of rupture. At the location of the defect identified, there was no myometrium or serosa. Our review of the literature shows that uterine rupture postseptal resection has been described in only case reports thus far.

The prevalence of uterine anomalies is 5.5% in the unselected population, 8.0% in infertile women, 13.3% in those with a history of miscarriage and 24.5% in those with miscarriage and infertility. Arcuate uterus is most common in the unselected population, whereas septate uterus is the most common anomaly in high-risk populations.3 Some studies report the pregnancy loss in septate uteri to be as high as 70%, with the proposed mechanisms being poor blood supply to the septum resulting in poor implantation, poor embryo growth and relative cervical insufficiency.4

Septal resection is an increasingly common surgery, an easy endoscopic day care procedure with uncommon morbidity. The complications include intraoperative perforation, cervical laceration and uterine perforation during resection. The rate of uterine perforation ranges from 1% to 3%, depending on the operator and institute.5 Roy et al described a uterine perforation rate of 1.2% with a caesarean section rate of 43.2% for obstetric reasons.6 Ergenoglu et al described a case of recurrent uterine ruptures in consecutive pregnancies in a patient who had undergone septal resection for recurrent abortions, each occurring earlier in gestation than the previous, causing fetal loss and considerable maternal morbidity.7 Senthilles et al analysed 14 case reports in the literature describing uterine rupture after operative hysteroscopy, with uterine perforation occurring in eight of the cases and electrosurgery used in nine case.1 Conturso and Howe in two separate studies reported no abnormalities in the scar after perforation during septal resection during serial 4 weekly transvaginal ultrasounds until spontaneous rupture occurred at 28 and 33 weeks.8 9 Kerimis et al reported the detection of rupture in a patient who had undergone uncomplicated septal resection during labour by the loss of beat-to-beat variability of the fetal heart; during laparotomy, a 7 cm defect was observed between the cornua.10

The current literature shows that there is paucity of evidence to predict the risk, timing or presentation of uterine rupture after operative hysteroscopy. It may occur after a complicated or uncomplicated procedure, remote from term, during labour, and can present in the form of haemorrhagic shock, persistent abdominal pain over the site of the rupture, fetal distress or, worst of all, silent. Our case was that of a silent spontaneous rupture, which could have been deadly if labour had commenced and the defect had extended to a major vessel.

Both physicians and patients need to consider these possibilities in future pregnancies before planning any hysteroscopic surgery.

Learning points.

Hysteroscopic septal resection is a commonly performed endoscopic procedure for infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss which has a potential risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.

Uterine perforation and use of monopolar electrocautery may be risk factors for rupture.

An uncomplicated septal resection does not preclude the possibility of rupture.

Rupture can present at any time during pregnancy, in the form of shock, pain or silently as in our case, leading to fetal distress or loss.

Patients should be informed about this remote risk prior to hysteroscopic surgery and during pregnancy.

Footnotes

Contributors: AAD was involved in the conception, drafting and editing of the article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sentilhes L, Sergent F, Roman H, et al. Late complications of operative hysteroscopy: predicting patients at risk of uterine rupture during subsequent pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005;120:134–8. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jansen FW, Vredevoogd CB, van Ulzen K, et al. Complications of hysteroscopy: a prospective, multicenter study. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:266–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, et al. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2011;17:761–71. 10.1093/humupd/dmr028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Homer HA, Li TC, Cooke ID. The septate uterus: a review of management and reproductive outcome. Fertil Steril 2000;73:1–14. 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith DC, Donohue LR, Waszak SJ. A hospital review of advanced gynecologic endoscopic procedures. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170:1635–42. 10.1016/S0002-9378(12)91828-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy KK, Singla S, Baruah J, et al. Reproductive outcome following hysteroscopic septal resection in patients with infertility and recurrent abortions. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;283:273–9. 10.1007/s00404-009-1336-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ergenoglu M, Yeniel AO, Yıldırım N, et al. Recurrent uterine rupture after hysterescopic resection of the uterine septum. Int J Surg Case Rep 2013;4:182–4. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conturso R, Redaelli L, Pasini A, et al. Spontaneous uterine rupture with amniotic sac protrusion at 28 weeks subsequent to previous hysteroscopic metroplasty. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003;107:98–100. 10.1016/S0301-2115(02)00242-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howe RS. Third-trimester uterine rupture following hysteroscopic uterine perforation. Obstet Gynecol 1993;81:827–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerimis P, Zolti M, Sinwany G, et al. Uterine rupture after hysteroscopic resection of uterine septum. Fertil Steril 2002;77:618–20. 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)03222-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]