Abstract

These guidelines are intended for use by healthcare professionals who care for children and adults with suspected or confirmed infectious diarrhea. They are not intended to replace physician judgement regarding specific patients or clinical or public health situations. This document does not provide detailed recommendations on infection prevention and control aspects related to infectious diarrhea.

Keywords: diarrhea, infectious, diagnostics, management, prevention

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The following evidence-based guidelines for management of infants, children, adolescents, and adults in the United States with acute or persistent infectious diarrhea were prepared by an expert panel assembled by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and replace guidelines published in 2001 [1]. Public health aspects of diarrhea associated with foodborne and waterborne diarrhea, international travel, antimicrobial agents, immunocompromised hosts, animal exposure, certain sexual practices, healthcare-associated diarrheal infections, and infections acquired in childcare and long-term care facilities will be referred to in these guidelines, but are not covered extensively due to availability of detailed discussions of this information in other publications. For recommendations pertaining to Clostridium difficile, refer to the existing IDSA/Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) guidelines on C. difficile infections, which are in the process of being updated.

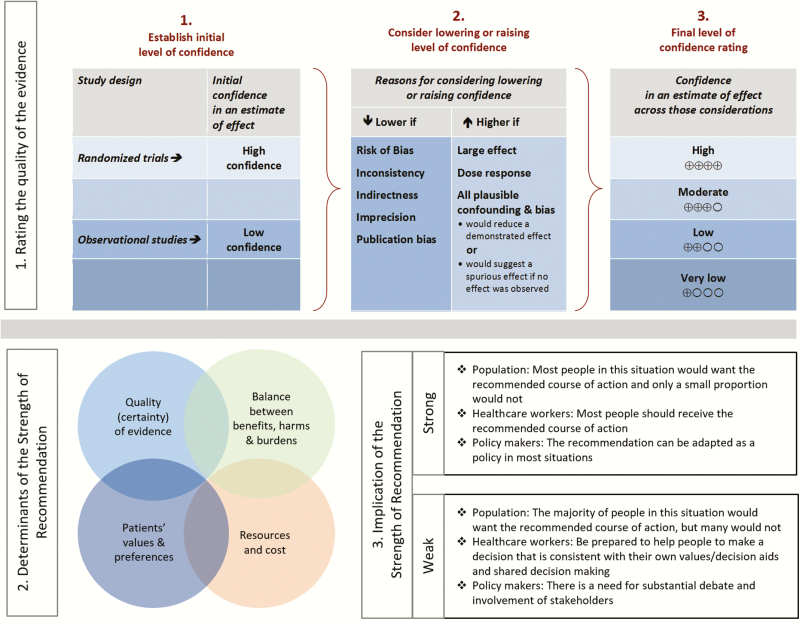

Summarized below are recommendations made in the updated guidelines for diagnosis and management of infectious diarrhea. The Panel followed a process used in development of other IDSA guidelines [2] which included a systematic weighting of the strength of recommendation and quality of evidence using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [3–7]. A detailed description of the methods, background, and evidence summaries that support each of the recommendations can be found online in the full text of the guidelines.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF INFECTIOUS DIARRHEA

Clinical, Demographic, and Epidemiologic Features

I. In people with diarrhea, which clinical, demographic, or epidemiologic features have diagnostic or management implications? (Tables 1–3)

Table 1.

Modes of Acquisition of Enteric Organisms and Sources of Guidelines

| Mode | Title | URL | Author/Issuing Agency |

|---|---|---|---|

| International travel | Expert Review of the Evidence Base for Prevention of Travelers’ Diarrhea | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19538575 | DuPont et al [10] |

| Medical Considerations Before International Travel | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27468061 | Freedman et al [12] | |

| The Yellow Book | http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/ yellowbook-home-2014 | CDC | |

| Travelers Health | http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel | CDC | |

| Immunocompromised hosts | Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents | http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/ adult_oi.pdf | CDC/NIH/HIVMA/IDSA |

| Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Exposed and HIV-Infected Children | http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/ oi_guidelines_pediatrics.pdf | CDC/NIH/HIVMA/IDSA | |

| Foodborne and waterborne | Surveillance for Foodborne Disease Outbreaks—United States, 2009–2010 | http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ mm6203a1.htm?s_cid=mm6203a1_w | CDC |

| Food Safety | http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/ | CDC | |

| Healthy Water | http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/healthywater | CDC | |

| Antimicrobial-associated (C. difficile) | Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children 2017 Update (in press) | http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/651706 | IDSA/SHEA |

| 2010 Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults | https://www.idsociety.org/ Organ_System/#Clostridiumdifficile | IDSA/SHEA | |

| Healthcare-associated | Healthcare-Associated Infections | http://www.cdc.gov/hai/ | CDC |

| Child care settings | Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs | http://nrckids.org. | AAP, APHA, NRC |

| Recommendations for Care of Children in Special Circumstances—Children in Out- of-Home Child Care (pp 132–51) | http://redbook.solutions.aap.org/redbook.aspx | AAP | |

| Managing Infectious Diseases in Child Care and Schools | http://ebooks.aappublications.org/content/managing-infectious-diseases-in-child-care-and-schools-3rd-edition | AAP | |

| Long-term care settings | Nursing Homes and Assisted Living (Long- term Care Facilities) | http://www.cdc.gov/longtermcare/ | CDC |

| Infection Prevention and Control in the Long-term Care Facility | http://www.shea-online.org/assets/files/position-papers/ic-ltcf97.pdf | SHEA/APIC | |

| Zoonoses | Compendium of Measures to Prevent Disease Associated With Animals in Public Settings | http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ rr6004a1.htm?s_cid=rr6004a1_w | CDC |

| Exposure to Nontraditional Pets at Home and to Animals in Public Settings: Risks to Children | http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ content/122/4/876 | Pickering et al [9] | |

| Review of Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Recommendations for One Health Initiative | http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/19/12/12-1659_ article.htm | Rubin et al [13] |

Abbreviations: AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; APHA, American Public Health Association; APIC, Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HIVMA, HIV Medicine Association; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NRC, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education; SHEA, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

Table 2.

Exposure or Condition Associated With Pathogens Causing Diarrhea

| Exposure or Condition | Pathogen(s) |

|---|---|

| Foodborne | |

| Foodborne outbreaks in hotels, cruise ships, resorts, restaurants, catered events | Norovirus, nontyphoidal Salmonella, Clostridium perfringens, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Campylobacter spp, ETEC, STEC, Listeria, Shigella, Cyclospora cayetanensis, Cryptosporidium spp |

| Consumption of unpasteurized milk or dairy products | Salmonella, Campylobacter, Yersinia enterocolitica, S. aureus toxin, Cryptosporidium, and STEC. Listeria is infrequently associated with diarrhea, Brucella (goat milk cheese), Mycobacterium bovis, Coxiella burnetii |

| Consumption of raw or undercooked meat or poultry | STEC (beef), C. perfringens (beef, poultry), Salmonella (poultry), Campylobacter (poultry), Yersinia (pork, chitterlings), S. aureus (poultry), and Trichinella spp (pork, wild game meat) |

| Consumption of fruits or unpasteurized fruit juices, vegetables, leafy greens, and sprouts | STEC, nontyphoidal Salmonella, Cyclospora, Cryptosporidium, norovirus, hepatitis A, and Listeria monocytogenes |

| Consumption of undercooked eggs | Salmonella, Shigella (egg salad) |

| Consumption of raw shellfish | Vibrio species, norovirus, hepatitis A, Plesiomonas |

| Exposure or contact | |

| Swimming in or drinking untreated fresh water | Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Giardia, Shigella, Salmonella, STEC, Plesiomonas shigelloides |

| Swimming in recreational water facility with treated water | Cryptosporidium and other potentially waterborne pathogens when disinfectant concentrations are inadequately maintained |

| Healthcare, long-term care, prison exposure, or employment | Norovirus, Clostridium difficile, Shigella, Cryptosporidium, Giardia, STEC, rotavirus |

| Child care center attendance or employment | Rotavirus, Cryptosporidium, Giardia, Shigella, STEC |

| Recent antimicrobial therapy | C. difficile, multidrug-resistant Salmonella |

| Travel to resource-challenged countries | Escherichia coli (enteroaggregative, enterotoxigenic, enteroinvasive), Shigella, Typhi and nontyphoidal Salmonella, Campylobacter, Vibrio cholerae, Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia, Blastocystis, Cyclospora, Cystoisospora, Cryptosporidium |

| Exposure to house pets with diarrhea | Campylobacter, Yersinia |

| Exposure to pig feces in certain parts of the world | Balantidium coli |

| Contact with young poultry or reptiles | Nontyphoidal Salmonella |

| Visiting a farm or petting zoo | STEC, Cryptosporidium, Campylobacter |

| Exposure or condition | |

| Age group | Rotavirus (6–18 months of age), nontyphoidal Salmonella (infants from birth to 3 months of age and adults >50 years with a history of atherosclerosis), Shigella (1–7 years of age), Campylobacter (young adults) |

| Underlying immunocompromising condition | Nontyphoidal Salmonella, Cryptosporidium, Campylobacter, Shigella, Yersinia |

| Hemochromatosis or hemoglobinopathy | Y. enterocolitica, Salmonella |

| AIDS, immunosuppressive therapies | Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Cystoisospora, microsporidia, Mycobacterium avium–intercellulare complex, cytomegalovirus |

| Anal-genital, oral-anal, or digital-anal contact | Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, E. histolytica, Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium as well as sexually transmitted infections |

Abbreviations: ETEC, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

Table 3.

Clinical Presentations Suggestive of Infectious Diarrhea Etiologies

| Finding | Likely Pathogens |

|---|---|

| Persistent or chronic diarrhea | Cryptosporidium spp, Giardia lamblia, Cyclospora cayetanensis, Cystoisospora belli, and Entamoeba histolytica |

| Visible blood in stool | STEC, Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Entamoeba histolytica, noncholera Vibrio species, Yersinia, Balantidium coli, Plesiomonas |

| Fever | Not highly discriminatory—viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections can cause fever. In general, higher temperatures are suggestive of bacterial etiology or E. histolytica. Patients infected with STEC usually are not febrile at time of presentation |

| Abdominal pain | STEC, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, noncholera Vibrio species, Clostridium difficile |

| Severe abdominal pain, often grossly bloody stools (occasionally nonbloody), and minimal or no fever | STEC, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, and Yersinia enterocolitica |

| Persistent abdominal pain and fever | Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis; may mimic appendicitis |

| Nausea and vomiting lasting ≤24 hours | Ingestion of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin or Bacillus cereus (short-incubation emetic syndrome) |

| Diarrhea and abdominal cramping lasting 1–2 days | Ingestion of Clostridium perfringens or B. cereus (long-incubation emetic syndrome) |

| Vomiting and nonbloody diarrhea lasting 2–3 days or less | Norovirus (low-grade fever usually present during the first 24 hours in 40% if infections) |

| Chronic watery diarrhea, often lasting a year or more | Brainerd diarrhea (etiologic agent has not been identified); postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome |

Abbreviation: STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

Recommendations

1. A detailed clinical and exposure history should be obtained from people with diarrhea, under any circumstances, including when there is a history of similar illness in others (strong, moderate).

2. People with diarrhea who attend or work in child care centers, long-term care facilities, patient care, food service, or recreational water venues (eg, pools and lakes) should follow jurisdictional recommendations for outbreak reporting and infection control (strong, high).

II. In people with fever or bloody diarrhea, which clinical, demographic, or epidemiologic features have diagnostic or management implications? (Tables 1–3)

Recommendations

3. People with fever or bloody diarrhea should be evaluated for enteropathogens for which antimicrobial agents may confer clinical benefit, including Salmonella enterica subspecies, Shigella, and Campylobacter (strong, low).

4. Enteric fever should be considered when a febrile person (with or without diarrhea) has a history of travel to areas in which causative agents are endemic, has had consumed foods prepared by people with recent endemic exposure, or has laboratory exposure to Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi and Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Paratyphi (strong, moderate). In this document, Salmonella Typhi represents the more formal and detailed name Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi, and Salmonella Paratyphi corresponds to the Paratyphi serovar.

III. What clinical, demographic, or epidemiologic features are associated with complications or severe disease? (Tables 2 and 3)

Recommendations

5. People of all ages with acute diarrhea should be evaluated for dehydration, which increases the risk of life-threatening illness and death, especially among the young and older adults (strong, high).

6. When the clinical or epidemic history suggests a possible Shiga toxin–producing organism, diagnostic approaches should be applied that detect Shiga toxin (or the genes that encode them) and distinguish Escherichia coli O157:H7 from other Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC) in stool (strong, moderate). If available, diagnostic approaches that can distinguish between Shiga toxin 1 and Shiga toxin 2, which is typically more potent, could be used (weak, moderate). In addition, Shigella dysenteriae type 1, and, rarely, other pathogens may produce Shiga toxin and should be considered as a cause of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), especially in people with suggestive international travel or personal contact with a traveler (strong, moderate).

7. Clinicians should evaluate people for postinfectious and extraintestinal manifestations associated with enteric infections (strong, moderate) [8].

Diagnostics

IV. Which pathogens should be considered in people presenting with diarrheal illnesses, and which diagnostic tests will aid in organism identification or outbreak investigation?

Recommendations

8. Stool testing should be performed for Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, C. difficile, and STEC in people with diarrhea accompanied by fever, bloody or mucoid stools, severe abdominal cramping or tenderness, or signs of sepsis (strong, moderate). Bloody stools are not an expected manifestation of infection with C. difficile. STEC O157 should be assessed by culture and non-O157 STEC should be detected by Shiga toxin or genomic assays (strong, low). Sorbitol-MacConkey agar or an appropriate chromogenic agar alternative is recommended to screen for O157:H7 STEC; detection of Shiga toxin is needed to detect other STEC serotype (strong, moderate).

9. Blood cultures should be obtained from infants <3 months of age, people of any age with signs of septicemia or when enteric fever is suspected, people with systemic manifestations of infection, people who are immunocompromised, people with certain high-risk conditions such as hemolytic anemia, and people who traveled to or have had contact with travelers from enteric fever–endemic areas with a febrile illness of unknown etiology (strong, moderate).

-

10. Stool testing should be performed under clearly identified circumstances (Table 2) for Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, C. difficile, and STEC in symptomatic hosts (strong, low). Specifically,

a. Test for Yersinia enterocolitica in people with persistent abdominal pain (especially school-aged children with right lower quadrant pain mimicking appendicitis who may have mesenteric adenitis), and in people with fever at epidemiologic risk for yersiniosis, including infants with direct or indirect exposures to raw or undercooked pork products.

6. In addition, test stool specimens for Vibrio species in people with large volume rice water stools or either exposure to salty or brackish waters, consumption of raw or undercooked shellfish, or travel to cholera-endemic regions within 3 days prior to onset of diarrhea.

11. A broader set of bacterial, viral, and parasitic agents should be considered regardless of the presence of fever, bloody or mucoid stools, or other markers of more severe illness in the context of a possible outbreak of diarrheal illness (eg, multiple people with diarrhea who shared a common meal or a sudden rise in observed diarrheal cases). Selection of agents for testing should be based on a combination of host and epidemiologic risk factors and ideally in coordination with public health authorities (strong, moderate).

12. A broad differential diagnosis is recommended in immunocompromised people with diarrhea, especially those with moderate and severe primary or secondary immune deficiencies, for evaluation of stool specimens by culture, viral studies, and examination for parasites (strong, moderate). People with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) with persistent diarrhea should undergo additional testing for other organisms including, but not limited to, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Cystoisospora, microsporidia, Mycobacterium avium complex, and cytomegalovirus (strong, moderate).

13. Diagnostic testing is not recommended in most cases of uncomplicated traveler’s diarrhea unless treatment is indicated. Travelers with diarrhea lasting 14 days or longer should be evaluated for intestinal parasitic infections (strong, moderate). Testing for C. difficile should be performed in travelers treated with antimicrobial agent(s) within the preceding 8–12 weeks. In addition, gastrointestinal tract disease including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) should be considered for evaluation (strong, moderate).

14. Clinical consideration should be included in the interpretation of results of multiple-pathogen nucleic acid amplification tests because these assays detect DNA and not necessarily viable organisms (strong, low).

15. All specimens that test positive for bacterial pathogens by culture-independent diagnostic testing such as antigen-based molecular assays (gastrointestinal tract panels), and for which isolate submission is requested or required under public health reporting rules, should be cultured in the clinical laboratory or at a public health laboratory to ensure that outbreaks of similar organisms are detected and investigated (strong, low). Also, a culture may be required in situations where antimicrobial susceptibility testing results would affect care or public health responses (strong, low).

16. Specimens from people involved in an outbreak of enteric disease should be tested for enteric pathogens per public health department guidance (strong, low).

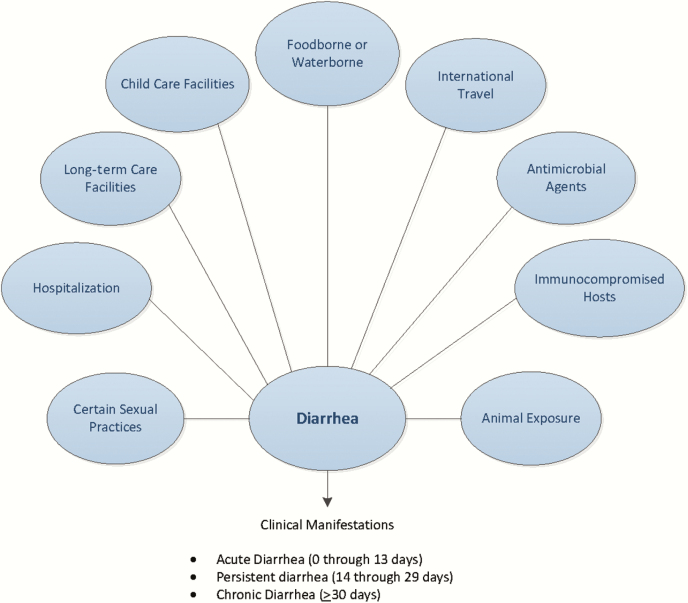

Figure 1.

Considerations when evaluating people with infectious diarrhea. Modified from Long SS, Pickering LK, Pober CG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 4th ed. New York: Elsevier Saunders, 2012.

V. Which diagnostic tests should be performed when enteric fever or bacteremia is suspected?

Recommendation

17. Culture-independent, including panel-based multiplex molecular diagnostics from stool and blood specimens, and, when indicated, culture-dependent diagnostic testing should be performed when there is a clinical suspicion of enteric fever (diarrhea uncommon) or diarrhea with bacteremia (strong, moderate). Additionally, cultures of bone marrow (particularly valuable if antimicrobial agents have been administered), stool, duodenal fluid, and urine may be beneficial to detect enteric fever (weak, moderate). Serologic tests should not be used to diagnose enteric fever (strong, moderate).

VI. When should testing be performed for Clostridium difficile?

Recommendation

18. Testing may be considered for C. difficile in people >2 years of age who have a history of diarrhea following antimicrobial use and in people with healthcare-associated diarrhea (weak, high). Testing for C. difficile may be considered in people who have persistent diarrhea without an etiology and without recognized risk factors (weak, low). A single diarrheal stool specimen is recommended for detection of toxin or a toxigenic C. difficile strain (eg, nucleic acid amplification testing) (strong, low). Multiple specimens do not increase yield.

VII. What is the optimal specimen (eg, stool, rectal swab, blood) for maximum yield of bacterial, viral, and protozoal organisms (for culture, immunoassay, and molecular testing)? (Table 4)

Table 4.

Laboratory Diagnostics for Organisms Associated With Infectious Diarrhea

| Etiologic Agent | Diagnostic Procedures | Optimal Specimen |

|---|---|---|

| Clostridium difficile | NAAT | Stool |

| GDH antigen with or without toxin detection followed by cytotoxin or Clostridium difficile toxin or toxigenic C. difficile strain | ||

| Salmonella enterica, Shigella spp, Campylobacter spp | Routine stool enteric pathogen culturea or NAAT | Stool |

| Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi (enteric fever) | Routine culture | Stool, blood, bone marrow, and duodenal fluid |

| Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli | Culture for E. coli O157:H7b and Shiga toxin immunoassay or NAAT for Shiga toxin genes |

Stool |

| Yersinia spp, Plesiomonas spp, Edwardsiella tarda, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli (enterotoxigenic, enteroinvasive, enteropathogenic, enteroaggregative) | Specialized stool culture or molecular assaysc or NAAT | Stool |

| Clostridium perfringens | Specialized procedure for toxin detectiond | Stool |

| Bacillus cereus, S. aureus | Specialized procedure for toxin detectiond | Food |

| Clostridium botulinum | Mouse lethality assay (performed at a state public health laboratory, or CDC) e,f,g | Serum, stool, gastric contents, vomitus |

|

Entamoeba

histolytica; Blastocystis hominih; Dientamoeba fragilish; Balantidium coli; Giardia lamblia; nematodes (generally not associated with diarrhea) including Ascaris lumbricoides, Strongyloides stercoralisi, Trichuris trichiura, hookworms; cestodes (tapeworms); trematodes (flukes) |

Ova and parasite examination including permanent stained smeari or NAAT | Stool Duodenal fluid for Giardia and Strongyloides |

| E. histolytica |

E. histolytica species-specific immunoassay or NAAT |

Stool |

| G. lamblia j | EIA or NAAT | Stool |

| Cryptosporidium spp [11]j | Direct fluorescent immunoassay, EIA, or NAAT | Stool |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis, Cystoisospora bellik | Modified acid-fast staink performed on concentrated specimen, ultraviolet fluorescence microscopy, or NAAT |

Stool |

| Microsporidia (now classified as a fungus) | Modified trichrome staink performed on concentrated specimen |

Stool |

| Histologic examination with electron microscopic confirmation | Small bowel biopsy | |

| Calicivirus (norovirus, sapovirus)k; enteric adenovirus; enterovirus/ parechovirusk; rotavirus | NAAT | Stool |

| Rotavirus, enteric adenovirus | EIA | Stool |

| Enteric adenovirusl; enterovirus/parechovirus | Viral culture | Stool |

| Cytomegalovirus | Histopathological examination | Biopsy |

| Cytomegalovirus culture | Biopsy |

The field of rapid diagnostic testing is rapidly expanding. We expect that additional diagnostic assays will become available following publication of these guidelines, specifically panel-based molecular diagnostics, including NAAT. Contact the laboratory for instructions regarding container, temperature, and transport guidelines to optimize results.

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test.

aRoutine stool culture in most laboratories is designed to detect Salmonella spp, Shigella spp, Campylobacter spp, and E. coli O157 or Shiga toxin–producing E. coli, but this should be confirmed with the testing laboratory.

bIt is recommended that laboratories routinely process all stool specimens submitted for bacterial culture for the presence of Shiga toxin–producing strains of E. coli including O157:H7. However, in some laboratories, O157:H7 testing is performed only by specific request.

cSpecialized cultures or molecular assays may be required to detect these organisms in stool specimens. The laboratory should be notified whenever there is a suspicion of infection due to one of these pathogens.

d Bacillus cereus, Clostridium perfringens, and Staphylococcus aureus are associated with diarrheal syndromes that are toxin mediated. An etiologic diagnosis is made by demonstration of toxin in stool for C. perfringens and demonstration of toxin in food for B. cereus and S. aureus.

eToxin assays are either performed in public health laboratories or referred to laboratories specializing in such assays.

fTesting for Clostridium botulinum toxin is either performed in public health laboratories or referred to laboratories specializing in such testing. The toxin is lethal and special precautions are required for handling. Class A bioterrorism agent and rapid sentinel laboratory reporting schemes must be followed. Immediate notification of a suspected infection to the state health department is mandated.

gImplicated food materials may also be examined for C. botulinum toxin, but most hospital laboratories are not equipped for food analysis.

hThe pathogenicity of Blastocystis hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis remains controversial. In the absence of other pathogens, they may be clinically relevant if symptoms persist. Reporting semiquantitative results (rare, few, many) may help determine significance and is a College of American Pathologists accreditation requirement for participating laboratories.

iDetection of Strongyloides in stool may require the use of Baermann technique or agar plate culture.

j Cryptosporidium and Giardia lamblia testing is often offered and performed together as the primary parasitology examination. Further studies should follow if the epidemiologic setting or clinical manifestations suggest parasitic disease.

kThese stains may not be routinely available.

lEnteric adenoviruses may not be recovered in routine viral culture.

Recommendation

19. The optimal specimen for laboratory diagnosis of infectious diarrhea is a diarrheal stool sample (ie, a sample that takes the shape of the container). For detection of bacterial infections, if a timely diarrheal stool sample cannot be collected, a rectal swab may be used (weak, low). Molecular techniques generally are more sensitive and less dependent than culture on the quality of specimen. For identification of viral and protozoal agents, and C. difficile toxin, fresh stool is preferred (weak, low).

Figure 2.

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

VIII. What is the clinical relevance of fecal leukocytes or lactoferrin or calprotectin in a person with acute diarrhea?

Recommendation

20. Fecal leukocyte examination and stool lactoferrin detection should not be used to establish the cause of acute infectious diarrhea (strong, moderate). There are insufficient data available to make a recommendation on the value of fecal calprotectin measurement in people with acute infectious diarrhea.

IX. In which clinical scenarios should nonmicrobiologic diagnostic tests be performed (eg, imaging, chemistries, complete blood count, and serology)?

Recommendations

21. Serologic tests are not recommended to establish an etiology of infectious diarrhea or enteric fever (strong, low), but may be considered for people with postdiarrheal HUS in which a stool culture did not yield a Shiga toxin–producing organism (weak, low).

22. A peripheral white blood cell count and differential and serologic assays should not be performed to establish an etiology of diarrhea (strong, low), but may be useful clinically (weak, low).

23. Frequent monitoring of hemoglobin and platelet counts, electrolytes, and blood urea nitrogen and creatinine is recommended to detect hematologic and renal function abnormalities that are early manifestations of HUS and precede renal injury for people with diagnosed E. coli O157 or another STEC infection (especially STEC that produce Shiga toxin 2 or are associated with bloody diarrhea) (strong, high). Examining a peripheral blood smear for the presence of red blood cell fragments is necessary when HUS is suspected (strong, high).

24. Endoscopy or proctoscopic examination should be considered in people with persistent, unexplained diarrhea who have AIDS, in people with certain underlying medical conditions as well as people with acute diarrhea with clinical colitis or proctitis and in people with persistent diarrhea who engage in anal intercourse (strong, low). Duodenal aspirate may be considered in select people for diagnosis of suspected Giardia, Strongyloides, Cystoisospora, or microsporidia infection (weak, low).

25. Imaging (eg, ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging) may be considered to detect aortitis, mycotic aneurysms, signs and symptoms of peritonitis, intra-abdominal free air, toxic megacolon, or extravascular foci of infection in older people with invasive Salmonella enterica or Yersinia infections if there is sustained fever or bacteremia despite adequate antimicrobial therapy or if the patient has underlying atherosclerosis or has recent-onset chest, back, or abdominal pain (weak, low).

X. What follow-up evaluations of stool specimens and nonstool tests should be performed in people with laboratory-confirmed pathogen-specific diarrhea who improve or respond to treatment, and in people who fail to improve or who have persistent diarrhea?

Recommendations

26. Follow-up testing is not recommended in most people for case management following resolution of diarrhea (strong, moderate). Collection and analysis of serial stool specimens using culture-dependent methods for Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi or Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Paratyphi, STEC, Shigella, nontyphoidal Salmonella, and other bacterial pathogens are recommended in certain situations by local health authorities following cessation of diarrhea to enable return to child care, employment, or group social activities (strong, moderate). Practitioners should collaborate with local public health authorities to adhere to policies regarding return to settings in which transmission is a consideration (strong, high).

27. A clinical and laboratory reevaluation may be indicated in people who do not respond to an initial course of therapy and should include consideration of noninfectious conditions including lactose intolerance (weak, low).

28. Noninfectious conditions, including IBD and IBS, should be considered as underlying etiologies in people with symptoms lasting 14 or more days and unidentified sources (strong, moderate).

29. Reassessment of fluid and electrolyte balance, nutritional status, and optimal dose and duration of antimicrobial therapy is recommended in people with persistent symptoms (strong, high).

Empiric Management of Infectious Diarrhea

XI. When is empiric antibacterial treatment indicated for children and adults with bloody diarrhea and, if indicated, with what agent?

a. What are modifying conditions that would support antimicrobial treatment of children and adults with bloody diarrhea?

b. In which instances should contacts be treated empirically if the agent is unknown?

Recommendations

-

30. In immunocompetent children and adults, empiric antimicrobial therapy for bloody diarrhea while waiting for results of investigations is not recommended (strong, low), except for the following:

a. Infants <3 months of age with suspicion of a bacterial etiology.

b. Ill immunocompetent people with fever documented in a medical setting, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, and bacillary dysentery (frequent scant bloody stools, fever, abdominal cramps, tenesmus) presumptively due to Shigella.

c. People who have recently travelled internationally with body temperatures ≥38.5°C and/or signs of sepsis (weak, low). See https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/the-pre-travel-consultation/travelers-diarrhea.

31. The empiric antimicrobial therapy in adults should be either a fluoroquinolone such as ciprofloxacin, or azithromycin, depending on the local susceptibility patterns and travel history (strong, moderate). Empiric therapy for children includes a third-generation cephalosporin for infants <3 months of age and others with neurologic involvement, or azithromycin, depending on local susceptibility patterns and travel history (strong, moderate).

32. Empiric antibacterial treatment should be considered in immunocompromised people with severe illness and bloody diarrhea (strong, low).

33. Asymptomatic contacts of people with bloody diarrhea should not be offered empiric treatment, but should be advised to follow appropriate infection prevention and control measures (strong, moderate).

34. People with clinical features of sepsis who are suspected of having enteric fever should be treated empirically with broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy after blood, stool, and urine culture collection (strong, low). Antimicrobial therapy should be narrowed when antimicrobial susceptibility testing results become available (strong, high). If an isolate is unavailable and there is a clinical suspicion of enteric fever, antimicrobial choice may be tailored to susceptible patterns from the setting where acquisition occurred (weak, low).

35. Antimicrobial therapy for people with infections attributed to STEC O157 and other STEC that produce Shiga toxin 2 (or if the toxin genotype is unknown) should be avoided (strong, moderate). Antimicrobial therapy for people with infections attributed to other STEC that do not produce Shiga toxin 2 (generally non-O157 STEC) is debatable due to insufficient evidence of benefit or the potential harm associated with some classes of antimicrobial agents (strong, low).

XII. When is empiric treatment indicated for children and adults with acute, prolonged, or persistent watery diarrhea and, if indicated, with what agent?

a. What are modifying conditions that would support empiric antimicrobial treatment of children and adults with watery diarrhea?

b. In which instances, if any, should contacts be treated empirically if the agent is unknown?

Recommendations

36. In most people with acute watery diarrhea and without recent international travel, empiric antimicrobial therapy is not recommended (strong, low). An exception may be made in people who are immunocompromised or young infants who are ill-appearing. Empiric treatment should be avoided in people with persistent watery diarrhea lasting 14 days or more (strong, low).

37. Asymptomatic contacts of people with acute or persistent watery diarrhea should not be offered empiric or preventive therapy, but should be advised to follow appropriate infection prevention and control measures (strong, moderate).

Directed Management of Infectious Diarrhea

XIII. How should treatment be modified when a clinically plausible organism is identified from a diagnostic test?

Recommendation

38. Antimicrobial treatment should be modified or discontinued when a clinically plausible organism is identified (strong, high).

Supportive Treatment

XIV. How should rehydration therapy be administered?

Recommendations

39. Reduced osmolarity oral rehydration solution (ORS) is recommended as the first-line therapy of mild to moderate dehydration in infants, children, and adults with acute diarrhea from any cause (strong, moderate), and in people with mild to moderate dehydration associated with vomiting or severe diarrhea.

40. Nasogastric administration of ORS may be considered in infants, children, and adults with moderate dehydration, who cannot tolerate oral intake, or in children with normal mental status who are too weak or refuse to drink adequately (weak, low).

41. Isotonic intravenous fluids such as lactated Ringer’s and normal saline solution should be administered when there is severe dehydration, shock, or altered mental status and failure of ORS therapy (strong, high) or ileus (strong, moderate). In people with ketonemia, an initial course of intravenous hydration may be needed to enable tolerance of oral rehydration (weak, low).

42. In severe dehydration, intravenous rehydration should be continued until pulse, perfusion, and mental status normalize and the patient awakens, has no risk factors for aspiration, and has no evidence of ileus (strong, low). The remaining deficit can be replaced by using ORS (weak, low). Infants, children, and adults with mild to moderate dehydration should receive ORS until clinical dehydration is corrected (strong, low).

43. Once the patient is rehydrated, maintenance fluids should be administered. Replace ongoing losses in stools from infants, children, and adults with ORS, until diarrhea and vomiting are resolved (strong, low).

XV. When should feeding be initiated following rehydration?

Recommendations

44 Human milk feeding should be continued in infants and children throughout the diarrheal episode (strong, low).

45. Resumption of an age-appropriate usual diet is recommended during or immediately after the rehydration process is completed (strong, low).

Ancillary Management

XVI. What options are available for symptomatic relief, and when should they be offered?

Recommendations

46. Ancillary treatment with antimotility, antinausea, or antiemetic agents can be considered once the patient is adequately hydrated, but their use is not a substitute for fluid and electrolyte therapy (weak, low).

47. Antimotility drugs (eg, loperamide) should not be given to children <18 years of age with acute diarrhea (strong, moderate). Loperamide may be given to immunocompetent adults with acute watery diarrhea (weak, moderate), but should be avoided at any age in suspected or proven cases where toxic megacolon may result in inflammatory diarrhea or diarrhea with fever (strong, low).

48. Antinausea and antiemetic (eg, ondansetron) may be given to facilitate tolerance of oral rehydration in children >4 years of age and in adolescents with acute gastroenteritis associated with vomiting (weak, moderate).

XVII. What is the role of a probiotic or zinc in treatment or prevention of infectious diarrhea in children and adults?

Recommendations

49. Probiotic preparations may be offered to reduce the symptom severity and duration in immunocompetent adults and children with infectious or antimicrobial-associated diarrhea (weak, moderate). Specific recommendations regarding selection of probiotic organism(s), route of delivery, and dosage may be found through literature searches of studies and through guidance from manufacturers.

50. Oral zinc supplementation reduces the duration of diarrhea in children 6 months to 5 years of age who reside in countries with a high prevalence of zinc deficiency or who have signs of malnutrition (strong, moderate).

XVIII. Which asymptomatic people with an identified bacterial organism from stool culture or molecular testing should be treated with an antimicrobial agent?

Recommendations

51. Asymptomatic people who practice hand hygiene and live and work in low-risk settings (do not provide healthcare or child or elderly adult care and are not food service employees) do not need treatment, except asymptomatic people with Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi in their stool who may be treated empirically to reduce potential for transmission (weak, low). Asymptomatic people who practice hand hygiene and live and work in high-risk settings (provide healthcare or child or elderly adult care and are food service employees) should be treated according to local public health guidance (strong, high).

Prevention

XIX. What strategies, including public health measures, are beneficial in preventing transmission of pathogens associated with infectious diarrhea?

Recommendations

52. Hand hygiene should be performed after using the toilet, changing diapers, before and after preparing food, before eating, after handling garbage or soiled laundry items, and after touching animals or their feces or environments, especially in public settings such as petting zoos (strong, moderate).

53. Infection control measures including use of gloves and gowns, hand hygiene with soap and water, or alcohol-based sanitizers should be followed in the care of people with diarrhea (strong, high). The selection of a hand hygiene product should be based upon a known or suspected pathogen and the environment in which the organism may be transmitted (strong, low). See https://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007IP/2007isolationPrecautions.html.

54. Appropriate food safety practices are recommended to avoid cross-contamination of other foods or cooking surfaces and utensils during grocery shopping, food preparation, and storage; ensure that foods containing meats and eggs are cooked and maintained at proper temperatures (strong, moderate).

55. Healthcare providers should direct educational efforts toward all people with diarrhea, but particularly to people with primary and secondary immune deficiencies, pregnant women, parents of young children, and the elderly as they have increased risk of complications from diarrheal disease (strong, low).

56. Ill people with diarrhea should avoid swimming, water-related activities, and sexual contact with other people when symptomatic while adhering to meticulous hand hygiene (strong, low).

XX. What are the relative efficacies and effectiveness of vaccines (rotavirus, typhoid, and cholera) to reduce and prevent transmission of pathogens associated with infectious diarrhea, and when should they be used?

Recommendations

57. Rotavirus vaccine should be administered to all infants without a known contraindication (strong, high).

58. Two typhoid vaccines (oral and injectable) are licensed in the United States but are not recommended routinely. Typhoid vaccination is recommended as an adjunct to hand hygiene and the avoidance of high-risk foods and beverages, for travelers to areas where there is moderate to high risk for exposure to Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi, people with intimate exposure (eg, household contact) to a documented Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi chronic carrier, and microbiologists and other laboratory personnel routinely exposed to cultures of Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi (strong, high). Booster doses are recommended for people who remain at risk (strong, high).

59. A live attenuated cholera vaccine, which is available as a single-dose oral vaccine in the United States, is recommended for adults 18–64 years of age who travel to cholera-affected areas (strong, high). See https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/vaccines.html.

XXI. How does reporting of nationally notifiable organisms identified from stool specimens impact the control and prevention of diarrheal disease in the United States?

Recommendation

60. All diseases listed in the table of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System at the national level, including those that cause diarrhea, should be reported to the appropriate state, territorial, or local health department with submission of isolates of certain pathogens (eg, Salmonella, STEC, Shigella, and Listeria) to ensure that control and prevention practices may be implemented (strong, high).

Notes

Acknowledgments. The expert panel expresses its gratitude for thoughtful reviews of an earlier version by Drs Herbert Dupont, Richard L. Guerrant, and Timothy Jones. The panel thanks the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) for supporting guideline development, and specifically Vita Washington for her continued support throughout the guideline process. Appreciation is expressed to Dr Nathan Thielman for his contributions to the initial stages of guideline development and Dr Faruque Ahmed for his continued support and guidance regarding the GRADE system. Many thanks to Reed Walton for her assistance at many levels, William Thomas for help with the literature review, and Bethany Sederdahl for her editorial assistance.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Financial support. Support for these guidelines was provided by the IDSA.

Potential conflicts of interest. The following list is a reflection of what has been reported to the IDSA. To provide thorough transparency, the IDSA requires full disclosure of all relationships, regardless of relevancy to the guideline topic. Evaluation of such relationships as potential conflicts of interest is determined by a review process which includes assessment by the Standards and Practice Guidelines Committee (SPGC) Chair, the SPGC liaison to the development panel and the Board of Directors liaison to the SPGC and if necessary, the Conflicts of Interest (COI) Task Force of the Board. This assessment of disclosed relationships for possible COI will be based on the relative weight of the financial relationship (ie, monetary amount) and the relevance of the relationship (ie, the degree to which an association might reasonably be interpreted by an independent observer as related to the topic or recommendation of consideration). The reader of these guidelines should be mindful of this when the list of disclosures is reviewed. The institution at which A. L. S. is employed has received research grants from the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and the Gerber Foundation, from which she has received salary support, and she has received honoraria from SLACK and travel subsidies from International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (https://isappscience.org/) to attend annual meetings. J. C. has received research grants from the US Army, and stocks and bonds from Ariad and SIS Pharmaceuticals. A. C. has received research grants from CSL Behring and National Health & Medical Research. J. A. C. has received research grants from the CDC, National Institutes of Health (NIH), UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and New Zealand Health Research Council. J. M. L.’s institution has received research grants from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Pfizer, PCIRN, Dynavax, and Afexa. T. S. has received research grants from Merck, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada, and CIHR; has received honoraria from Merck, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Wyeth, and Pendopharm; and has served as a consultant on research contracts for Merck, Rebiotix, Acetlion, and Sanofi Pasteur. P. I. T. has received research grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the NIAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. C. W. has received research grants from the NIH, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck, and served as a consultant for Pfizer and Thera Pharmaceuticals. C. A. W. has received research grants from NIH, NIAID and received a patent from the University of Virginia. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Guerrant RL Van Gilder T Steiner TS, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:331–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Handbook on clinical practice guideline development, 2015 Available at: http://www.idsociety.org/uploadedFiles/IDSA/Guidelines-Patient_Care/IDSA_Practice_Guidelines/IDSA%20Handbook%20on%20CPG%20Development%2010.15.pdf. Accessed 15 January 2015.

- 3. Guyatt GH. U.S. GRADE Network. Approach and implications to rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations using the GRADE methodology Available at: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/. Accessed July 2015.

- 4. Guyatt GH Oxman AD Kunz R, et al. ; GRADE Working Group Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336:1049–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guyatt GH Oxman AD Kunz R, et al. ; GRADE Working Group Incorporating considerations of resources use into grading recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336:1170–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guyatt GH Oxman AD Vist GE, et al. ; GRADE Working Group GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336:924–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jaeschke R Guyatt GH Dellinger P, et al. ; GRADE Working Group Use of GRADE grid to reach decisions on clinical practice guidelines when consensus is elusive. BMJ 2008; 337:a744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen SH Gerding DN Johnson S, et al. ; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31:431–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pickering LK Marano N Bocchini JA Angulo FJ; Committee on Infectious Diseases Exposure to nontraditional pets at home and to animals in public settings: risks to children. Pediatrics 2008; 122:876–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DuPont HL Ericsson CD Farthing MJ, et al. . Expert review of the evidence base for prevention of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med 2009; 16:149–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baron EJ Miller JM Weinstein MP, et al. . A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:e22–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freedman DO Chen LH Kozarsky PE. Medical considerations before international travel. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:247–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rubin C Myers T Stokes W, et al. . Review of institute of medicine and national research council recommendations for One Health initiative. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:1913–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]