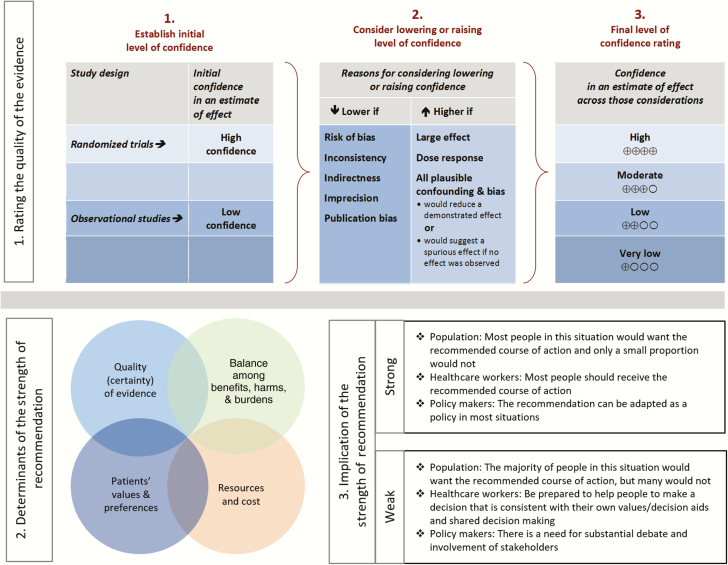

Summarized below are the recommendations made in the new guidelines for chronic pain in patients living with human immunodeficiency virus. The panel followed a process used in the development of other Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines that included a systematic weighting of the strength of recommendation and quality of evidence using the GRADE (grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation) system (Figure 1) [1–5]. A detailed description of the methods, background, and evidence summaries that support each recommendation can be found in the full text of the guidelines.

Abstract

Pain has always been an important part of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease and its experience for patients. In this guideline, we review the types of chronic pain commonly seen among persons living with HIV (PLWH) and review the limited evidence base for treatment of chronic noncancer pain in this population. We also review the management of chronic pain in special populations of PLWH, including persons with substance use and mental health disorders. Finally, a general review of possible pharmacokinetic interactions is included to assist the HIV clinician in the treatment of chronic pain in this population.

It is important to realize that guidelines cannot always account for individual variation among patients. They are not intended to supplant physician judgment with respect to particular patients or special clinical situations. The Infectious Diseases Society of American considers adherence to these guidelines to be voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding their application to be made by the physician in the light of each patient’s individual circumstances.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Summarized below are the recommendations made in the new guidelines for chronic pain in patients living with HIV (PLWH). The Panel followed a process used in the development of other IDSA guidelines that included a systematic weighting of the strength of recommendation and quality of evidence using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system (Figure 1) [1-5]. A detailed description of the methods, background, and evidence summaries that support each of the recommendations can be found in the full text of the guidelines.

Figure 1.

Approach and implications to rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations using the GRADE (grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation) methodology (unrestricted use of the figure granted by the US GRADE Network).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT OF PERSONS LIVING WITH HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS AND CHRONIC PAIN

I. What is the recommended approach to screening and initial assessment for chronic pain in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus?

Recommendations

1. All PLWH should receive, at minimum, the following standardized screening for chronic pain: How much bodily pain have you had during the last week? (none, very mild, mild, moderate, severe, very severe) and Do you have bodily pain that has lasted for more than 3 months? (strong, low). Remark: A response of moderate pain or more during the last week combined with bodily pain for more than 3 months can be considered a positive screen result.

2. For persons who screen positive for chronic pain, an initial assessment should take a biopsychosocial approach that includes an evaluation of the pain’s onset and duration, intensity and character, exacerbating and alleviating factors, past and current treatments, underlying or co-occurring disorders and conditions, and the effect of pain on physical and psychological function. This should be followed by a physical examination, psychosocial evaluation, and diagnostic workup to determine the potential cause of the pain (strong, very low). Remark: A multidimensional instrument such as the brief pain inventory (BPI) or the 3-item patient health questionnaire (PEG; used to assess average pain intensity [P], interference with enjoyment of life [E], and interference with general activity [G]) can be used for pain assessments.

3. Medical providers should monitor the treatment of chronic pain in PLWH, with periodic assessment of progress on achieving functional goals and documentation of pain intensity, quality of life, adverse events, and adherent vs aberrant behaviors (strong, very low). Remark: Reassessments should be conducted at regular intervals and after each change or initiation in therapy has had an adequate amount of time to take effect.

II. What is the recommended general approach to the management of persons living with human immunodeficiency virus and chronic pain?

Recommendations

4. HIV medical providers should develop and participate in interdisciplinary teams to care for patients with complex chronic pain and especially for patients with co-occurring substance use or psychiatric disorders (strong, very low).

5. For patients whose chronic pain is controlled, any new report of pain should be carefully investigated and may require added treatments or adjustments in the dose of pain medications while the new problem is being evaluated (strong, high). Remark: Providers should clearly document the new symptom and consult, if possible, with a provider experienced with pain management in PLWH or with a pain specialist.

III. What is the recommended therapeutic approach to chronic pain in persons with human immunodeficiency virus at the end of life?

Recommendations

6. As PLWH age, their pain experience may change as other age-related and HIV-related comorbidities develop. It is recommended that the clinician address these changes in pain experience in the context of this disease progression (strong, moderate).

7. Critical to maintaining pain control, it is recommended that medical providers and an integrated multidisciplinary team engage in frequent communication with the patient and the patient’s support system (eg, family, caregiver) (strong, low). Remark: Communications should occur at a health literacy level appropriate for the patient and patient’s support system. It may be necessary to schedule longer appointment times to allow both patients and providers to establish and clarify the goals of care.

8. Consultation with a palliative care specialist to assist with pain management and nonpain symptoms and to address goals of care is recommended (strong, low).

9. Patients with advanced illness require a support system beyond the clinic, and timely referrals for palliative or hospice care are recommended. The primary care provider must remain in communication with the patient and family through the end of life to ensure accurate continuity and to preclude a sense of abandonment (strong, low).

IV. What are the recommended nonpharmacological treatments for chronic pain in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus?

Recommendations

10. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is recommended for chronic pain management (strong, moderate). Remark: CBT promotes patient acceptance of responsibility for change and the development of adaptive behaviors (eg, exercise) while addressing maladaptive behaviors (eg, avoiding exercise due to fears of pain).

11. Yoga is recommended for the treatment of chronic neck/back pain, headache, rheumatoid arthritis, and general musculoskeletal pain (strong, moderate).

12. Physical and occupational therapy are recommended for chronic pain (strong, low).

13. Hypnosis is recommended for neuropathic pain (strong, low).

14. Clinicians might consider a trial of acupuncture for chronic pain (weak, moderate). Values and preferences: This recommendation places a relatively high value on the reduction of symptoms and few undesirable effects. Remark: Evidence to date is available only for acupuncture in the absence of amitriptyline and among PLWH with poorer health in the era before highly active antiretroviral therapy.

V. What are the recommended pharmacological treatments for chronic neuropathic pain in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus?

Nonopioid Recommendations

15. Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy is recommended for the prevention and treatment of HIV-associated distal symmetric polyneuropathy (strong, low).

-

16. Gabapentin is recommended as a first-line oral pharmacological treatment of chronic HIV-associated neuropathic pain (strong, moderate). Remark: A typical adult regimen will titrate to 2400 mg per day in divided doses. Evidence also supports that gabapentin improves sleep scores; somnolence was reported by 80% of patients who received gabapentin (strong, low).

a. If patients have an inadequate response to gabapentin, clinicians might consider a trial of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors based on their effectiveness in the general population (weak, moderate).

b. If patients have an inadequate response to gabapentin, clinicians might consider a trial of tricyclic antidepressants (weak, moderate).

c. If patients have an inadequate response to gabapentin, clinicians might consider a trial of pregabalin for patients with post-herpetic neuralgia (weak, moderate).

17 .Capsaicin is recommended as a topical treatment for the management of chronic HIV-associated peripheral neuropathic pain (strong, high). Remark: A single 30-minute application of an 8% dermal patch or cream administered at the site of pain can provide pain relief for at least 12 weeks. Erythema and pain are common side effects for which a 60-minute application of 4% lidocaine can be applied and wiped off before applying capsaicin (strong, high).

18. Medical cannabis may be an effective treatment in appropriate patients (weak, moderate). Values and preferences: This recommendation places a relatively high value on the reduction of symptoms and a relatively low value on the legal implication of medical cannabis possession. Remark: Current evidence suggests medical cannabis may be more effective for patients with a history of prior cannabis use; the potential benefits of a trial of cannabis need to be balanced with the potential risks of neuropsychiatric adverse effects at higher doses, the harmful effects of smoked forms of cannabis in patients with preexisting severe lung disease, and addiction risk to patients with cannabis use disorder.

19. We recommend alpha lipoic acid (ALA) for the management of chronic HIV-associated peripheral neuropathic pain (strong, low). Values and preferences: This recommendation places a high value on providing tolerable medications that may be of some benefit in patients with difficult-to-treat neuropathic pain. Remark: Studies in patients with HIV are lacking; however, there is a growing body of literature of the benefits of ALA in patients with diabetic neuropathy.

20. We recommend against using lamotrigine to relieve HIV-associated neuropathic pain (strong, moderate). Values and preferences: This recommendation places a relatively high value on the discontinuation of neurotoxic agents and on minimizing the incidence of lamotrigine-associated rash and places a relatively low value on the reduction in pain symptoms found in an earlier randomized controlled trial by the same authors. Remark: A benefit was only seen in patients currently receiving neurotoxic antiretroviral therapy (ART), and we recommend discontinuing all neurotoxic ART.

Use of Opioids

21. For PLWH, opioid analgesics should not be prescribed as a first-line agent for the long-term management of chronic neuropathic pain (strong, moderate). Values and preferences: This recommendation places a relatively high value on the potential risk of pronociception through the upregulation of specific chemokine receptors, cognitive impairment, respiratory depression, endocrine and immunological changes, and misuse and addiction.

22. Clinicians may consider a time-limited trial of opioid analgesics for patients who do not respond to first-line therapies and who report moderate to severe pain. As a second- or third-line treatment for chronic neuropathic pain, a typical adult regimen should start with the smallest effective dose and combine short- and long-acting opioids (weak, low). Remark: When opioids are appropriate, a combination regimen of morphine and gabapentin should be considered in patients with neuropathic pain for their possible additive effects and lower individual doses required of the 2 medications when combined.

V. What are the recommended nonopioid pharmacologic treatments for chronic nonneuropathic pain in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus?

Recommendations

23. Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended as first-line agents for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain (strong, high). Remark: Acetaminophen has fewer side effects than NSAIDs. Studies typically used 4 g/day dosing of acetaminophen; lower dosing is recommended for patients with liver disease. Compared to traditional NSAIDs, COX-2 NSAIDs are associated with decreased risk of gastrointestinal side effects but increased cardiovascular risk.

VI. What are the recommended opioid pharmacological treatments for chronic nonneuropathic pain in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus?

Recommendations

24. Patients who do not respond to first-line therapies and who report moderate to severe pain and functional impairment can be considered for a time-limited trial of opioid analgesics (weak, low). Values and preferences: This recommendation places a relatively high value on safer opioid prescribing. The potential benefits of opioid analgesics need to be balanced with the potential risks of adverse events, misuse, diversion, and addiction. Remark: As a second- or third-line treatment for chronic nonneuropathic pain, a typical adult regimen should start with the smallest effective dose, combining short- and long-acting opioids.

25. Tramadol taken for up to 3 months may decrease pain and improve stiffness, function, and overall well-being in patients with osteoarthritis (weak, moderate). Remark: The range of tramadol dosing studied is 37.5 mg (combined with 325 mg of acetaminophen) once daily to 400 mg in divided doses.

VII. What is the recommended approach for assessing the likelihood of developing the negative, unintended consequences of opioid treatment (eg, misuse, substance use disorder, or possible diversion) in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus?

Recommendations

26. Providers should assess all patients for the possible risk of developing the negative, unintended consequences of opioid treatment (eg, misuse, diversion, addiction) prior to prescribing opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic pain (strong, low). Remark: A trial of opioid analgesics for the treatment of moderate-to-severe chronic pain may be reasonable only when the potential benefits of chronic opioid therapy for pain severity, physical function, and quality of life outweigh its potential harms.

VIII. What is the recommended approach to safeguard persons living with human immunodeficiency virus against harm while undergoing the treatment of chronic pain with opioid analgesics?

Recommendations

27. Routine monitoring of patients prescribed opioid analgesics for the management of chronic pain is recommended (strong, very low). Remark: Opioid treatment agreements, urine drug testing (UDT), pill counts, and prescription drug monitoring programs are commonly used tools to safeguard against harms.

28. An “opioid patient–provider agreement (PPA)” is recommended as a tool for shared decision making with all patients before receiving opioid analgesics for chronic pain (strong, low). Remark: PPAs consist of 2 components: informed consent and a plan of care. When a patient’s behavior is inconsistent with the PPA, the provider must carefully consider a broad differential diagnosis.

29. The provider should understand the clinical uses and limitations of UDT, including test characteristics, indications for confirmatory testing, and the differential diagnosis of abnormal results (strong, low). Remark: UDT results should never be used in isolation to discharge patients from care. Rather, results should be used in combination with other clinical data for periodic evaluation of the current treatment plan and to support a clinical decision to safely continue opioid therapy.

IX. What are the recommended methods to minimize adverse effects from chronic opioid therapy in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus?

Recommendations

30. Controlled substances should be stored safely away from individuals at risk of misuse and/or overdose; family members should be educated on the medications and signs of overdose, and the poison control number should be readily visible (strong, low).

31. Clinicians should teach patients and their caregivers about opioid overdose and the use of naloxone to reverse overdose; a naloxone rescue kit should be readily available (strong, moderate).

32. Patient education is recommended to help patients avoid adverse events related to pharmacological interactions (strong, low).

33. Providers should be knowledgeable about common pharmacological interactions and be prepared to identify and manage those drug–drug interactions (strong, low). Providers should follow patients closely when interactions are likely (strong, low).

X. What is the recommended approach to prescribing controlled substances for the management of chronic pain to persons living with human immunodeficiency virus with a history of substance use disorder?

Recommendations

34. Persons with a history of a substance use disorder or addiction should be carefully evaluated and risk stratified in the same manner as all other PLWH with chronic pain (strong, low). Values and preferences: This recommendation places a high value on clinical strategies that neutralize bias and reduce stigma in the care of all PLWH and the possibility of behavior change over time. Remark: A patient’s history of addiction or substance use disorder is not an absolute contraindication to receiving controlled substances for the management of chronic pain. A risk–benefit framework that views controlled substances as medications with unique risks to every patient (“a universal precautions approach”) should be applied uniformly to help providers make fair and informed clinical decisions about controlled substance prescribing.

35. Persons with a history of addiction for whom the risks currently outweigh the benefits of a controlled substance prescription should have their chronic pain reasonably managed by other therapies and should receive emotional support, close monitoring and reassessment, and linkages to addiction treatment and mental health services as indicated (strong, low). Values and preferences: This recommendation places a high value on access to pain management as a fundamental human right with an underlying principle that every person deserves to have his or her pain reasonably managed by adequately trained healthcare professionals and that every medical provider has a duty to listen to and reasonably respond to a patient’s report of pain.

XI. What are the recommended approaches to the pharmacological management of chronic pain in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus who are on methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder?

Recommendations

36. A signed release for the exchange of health information between the provider and the opioid treatment program (OTP) is recommended prior to any controlled substance prescribing (strong, low). Remark: Ongoing communication with the OPT is essential when there are 2 controlled substance prescribers. Sharing information about a patient’s progress in recovery is an important component of the assessment and periodic monitoring of a pain treatment’s risks and benefits, for example, whether to pursue a trial of or to continue or discontinue opioid analgesic therapy.

37. Initial screening with electrocardiogram to identify heart rate corrected QT (QTc) prolongation for all patients on methadone is recommended, with interval follow-up with dose changes. This is especially helpful if the patient is also prescribed other medications that may additively prolong the QTc (eg, certain psychotropics, fluconazole, macrolides, potassium-lowering agents) (strong, low).

38. The splitting of methadone into 6- to 8-hour doses is recommended in order to lengthen the active analgesic effects of methadone with the goal of continuous pain control (strong, low). Remark: Some OTPs may be able to offer a split-dose methadone regimen for patients. Alternatively, the medical provider may need to prescribe the remaining daily doses: 5%–10% of the current methadone dose should be added, usually as an afternoon and evening dose for a total 10%–20% increase over the regular dose for the treatment of opioid use disorder (strong, very low).

39. If prescribing additional methadone is not possible (eg, OTP policy, high baseline methadone dose, prolonged QTc intervals, high risk of diversion, the patient is new to or poorly adherent to the OTP), then an additional medication may be recommended for chronic pain management depending on the etiology of the pain (eg, gabapentin for neuropathic pain, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for musculoskeletal pain, or an additional opioid) (weak, low).

40. Acute exacerbations in pain or “breakthrough pain” should be treated with small amounts of short-acting opioid analgesics in patients at low risk for opioid misuse (strong, low). Remark: Providers and patients should agree on the number of pills that will be dispensed for breakthrough pain, their frequency of use, and the expected duration of this treatment.

XII. What are the recommended approaches to the pharmacological management of chronic pain in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus who are on buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorders?

Recommendations

41. Clinicians should use adjuvant therapy appropriate to the pain syndrome for mild-to-moderate breakthrough pain (strong, moderate). Remark: These adjuvants include, but are not limited to, nonpharmacologic treatments, steroids, nonopioid analgesics, and topical agents. (See section on “nonopioids” for treatment of chronic neuropathic and nonneuropathic pain.)

42. Based on expert opinion, the clinician should increase the dosage of buprenorphine in divided does as an initial step in the management of chronic pain (strong, very low). Remark: Dosing ranges of 4–16 mg divided into 8-hour doses have shown benefit in patients with chronic noncancer pain.

43. Based on expert opinion, clinician’s might switch from buprenorphine/naloxone to buprenorphine transdermal formulation alone (weak, very low).

44. We recommend that if a maximal dose of buprenorphine is reached, an additional long-acting potent opioid such as fentanyl, morphine, or hydromorphone should be tried (strong, low).

45. If usual doses of an additional opioid are ineffective for improving chronic pain, we recommend a closely monitored trial of higher doses of an additional opioid (strong, moderate). Remark: Buprenorphine’s high binding affinity for the μ-opioid receptor may prevent the lower doses of other opioids from accessing the μ-opioid receptor.

46. For patients on buprenorphine maintenance with inadequate analgesia despite the above-mentioned strategies, we recommend transitioning the patient from buprenorphine to methadone maintenance (strong, very low).

XIII. What are the recommended instruments for screening common mental health disorders in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus with chronic pain?

Recommendations

47. Clinicians should fully review a patient’s baseline mental health status for modifiable factors that can impact successful pain management (strong, low). Remark: Potentially modifiable factors include self-esteem and coping skills; recent major loss or grief; unhealthy substance use; history of violence or lack of safety in the home; mood disorders; and history of serious mental illness or suicidal ideation.

48. All patients should be screened for depression with the following 2 questions: During the past 2 weeks have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? During the past 2 weeks have you been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things? (strong, high). Remark: If the patient answers in the affirmative to either question, a follow-up question regarding help should be asked: Is this something with which you would like help?

49. The patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which is in the public domain, is recommended as a screening tool in clinical settings without access to trained mental health professionals as it can be used to diagnose depression (strong, high). Remark: Psychiatric follow-up for a result that is ≥10 (88% sensitivity and 88% specificity for major depression) is recommended, and the clinical site should have a policy for referrals for more in-depth evaluation of these issues.

50. All patients should be screened for comorbid neurocognitive disorders prior to and during use of long-term opioid therapy (strong, low). Remark: Questions administered to elicit cognitive complaints in the Swiss HIV Cohort study (eg, frequent memory loss; feeling slower when reasoning, planning activities, or solving problems; and difficulties paying attention) detected, but have not been tested as screening questions in the clinical setting.

51. It is recommended that all patients with chronic pain have a full neuropsychiatric evaluation with history, physical, and use of the HIV dementia scale or an equivalent to document baseline capacity (strong, high).

Acknowledgments. The Expert Panel expresses its gratitude to external reviewers Drs Robert Arnold, E. Jennifer Edelman, and Romy Parker. The panel also thanks Vita Washington for continued guidance throughout the guideline development process.

Financial support. Support was provided by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

Potential conflicts of interest. The following is a reflection of what has been reported to the IDSA. In order to provide thorough transparency, the IDSA requires full disclosure of all relationships, regardless of relevancy to the guideline topic. Evaluation of such relationships as potential conflicts of interest is determined by a review process that includes assessment by the Standards and Practice Guidelines Committee (SPGC) chair, the SPGC liaison to the development panel, the Board of Directors (BOD) liaison to the SPGC, and, if necessary, the Conflict of Interest Task Force of the board. This assessment of disclosed relationships for possible conflicts of interest is based on the relative weight of the financial relationship (ie, monetary amount) and the relevance of the relationship (ie, the degree to which an association might reasonably be interpreted by an independent observer as related to the topic or recommendation of consideration). The reader should be mindful of this when the list of disclosures is reviewed. A. C. has received research grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. ; GRADE Working Group Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336:1049–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. ; GRADE Working Group GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336:924–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 2008; 336:995–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Dellinger P et al. ; GRADE Working Group Use of GRADE grid to reach decisions on clinical practice guidelines when consensus is elusive. BMJ 2008; 337:a744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:e72–e112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]