Abstract

Affective instability and interpersonal stress are key features of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). They were shown to co-vary in the daily lives of patients in a recent ambulatory assessment study (Hepp et al., 2017) that observed comparatively larger positive associations between interpersonal stressors and negative affect in individuals with BPD than those with depressive disorders. The present study sought to replicate these findings, collecting data on hostility, sadness, fear, and rejection or disagreement events from 56 BPD and 60 community control participants for twenty-one days, six times a day. Using identical statistical procedures, the positive associations between momentary rejection/disagreement and hostility, sadness, and fear were replicated. Again replicating the original study, the rejection-hostility, rejection-sadness, and disagreement-hostility associations were significantly stronger in the BPD group. Time-lagged analyses extended the original study, revealing that rejection was associated with subsequent hostility and sadness more strongly in the BPD group, as was disagreement with subsequent hostility and fear. Though small, we argue that the observed group differences reflect meaningful pervasive responses in a daily life context. Future research should consider these when implementing affect regulation strategies that are applicable in interpersonal contexts for all individuals, but particularly those with BPD.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder, interpersonal problems, negative affect, rejection, ambulatory assessment

Introduction

Affective instability is a hallmark feature of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) that is theorized to result from a heightened dispositional sensitivity to emotions and marked affective reactivity to external and internal stressors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Crowell, Beauchaine, & Linehan, 2009). Previous studies have identified negative interpersonal events (especially rejection) as external stressors that are associated with affective instability in BPD. In experimental studies, BPD participants reported stronger increases in negative affect (NA) following rejection compared to control participants (Dixon-Gordon, Chapman, Lovasz, & Walters, 2011; Dixon-Gordon, Gratz, Breetz, & Tull, 2013). Ambulatory Assessment (AA; see Trull & Ebner-Priemer, 2013) studies that collected data in BPD individuals’ daily lives showed stronger associations between momentary rejection and NA in BPD than in control participants (Sadikaj, Moskowitz, Russell, Zuroff, & Paris, 2013; Sadikaj, Russell, Moskowitz, & Paris, 2010) and positive associations between rejection and aversive tension (Stiglmayr et al., 2005) as well as between rejection, disagreement and NA (Chaudhury et al., 2017). Importantly, both experimental (Beeney, Levy, Gatzke-Kopp, & Hallquist, 2014; Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler, & Walters, 2015; Renneberg et al., 2012) and AA studies (Berenson, Downey, Rafaeli, Coifman, & Paquin, 2011; Miskewicz et al., 2015) also provide evidence for a more specific association between rejection and hostility/anger-like constructs.

A recent study (Hepp et al., 2017) sought to examine the specificity of such associations by simultaneously modeling three subtypes of NA (hostility, sadness, fear) and two different interpersonal stressors (rejection, disagreement) in 80 individuals with BPD and 51 depressed individuals using AA. In both groups, disagreement and rejection were positively associated with concurrent hostility, sadness, and fear at the momentary- and day-levels. Importantly, the disagreement-hostility associations were significantly stronger in the BPD group at both levels, as were the rejection-hostility and rejection-sadness associations at the day level. This suggested that hostile affect is particularly reactive to interpersonal stressors in those with BPD.

The present study sought to replicate these findings in a separate BPD sample and a community control group. Mirroring the original study, hostility, sadness, fear, rejection and disagreement were assessed. The three affects were selected because they are explicitly mentioned in the DSM-5 affective instability criterion of BPD, which requires “a marked reactivity of mood (e.g., intense episodic dysphoria, irritability, or anxiety […]” (APA, 2013, p. 663). Beyond replication, we aimed to extend Hepp et al. (2017) by providing replication with a different control group and extending the findings to lagged relationships. The original study demonstrated associations between NA and interpersonal stressors only in the same time-period, whereas the present study employed a modified data collection protocol that allowed us to assess the temporal ordering of NA and interpersonal stressors.

Hypotheses

H1: Previous AA studies have shown positive associations between momentary rejection or disagreement and general NA in BPD (Chaudhury et al., 2017; Sadikaj et al., 2013; Sadikaj et al., 2010), and Hepp et al. (2017) extended these findings to specific types of negative affect. We expected to replicate the positive concurrent associations of rejection and disagreement with hostility, sadness, and fear that Hepp et al. (2017) reported.

H2: Previous studies using experimental (e.g., Chapman et al., 2015; Renneberg et al., 2012) and AA methods (e.g., Berenson et al., 2011; Miskewicz et al., 2015) have shown a positive association between hostility/anger-like constructs and rejection. Hepp et al. (2017) extended this to disagreement and showed some specificity for BPD. We thus similarly expected to find significantly stronger associations of hostility with rejection and disagreement in those with BPD.

H3: Hepp et al. (2017) focused on concurrent relationships between NA and interpersonal stressors, while the present study aimed to extend these to lagged relationships. We expected rejection and disagreement events to positively predict hostility, sadness, and fear at the following time-point (on average 2 hours later). We further expected this effect to be stronger in the BPD group because affect in BPD is more likely to be influenced by past interpersonal stressors due to affective instability (APA, 2013).

Method

Participants

A total of 116 participants aged 18 to 45 who reported consuming alcohol at least once a week were recruited from local psychiatric outpatient clinics and community advertisements. Exclusion criteria were: current treatment for alcohol use, unsuccessful efforts to reduce/stop alcohol use, past-year physiological withdrawal symptoms, current psychosis, intellectual disability, severe neurological dysfunction, or previous head trauma. Further details are reported in Lane, Carpenter, Sher, and Trull (2016).

The BPD group included 56 individuals who met criteria for BPD, endorsed the affective instability criterion, and were currently in treatment. The 60 community control participants (COM) did not meet criteria for BPD or affective instability. BPD participants did not differ from COM participants regarding age (BPD: M=26.0, SD=7.2; COM: M=26.7, SD=7.1; t(114)=0.50, p=.618) or gender, with similar percentages of women in both groups (BPD=82.1% women; COM=75.0%, χ2(1)=0.87, p=.350). The majority of participants in both groups were of Caucasian ethnicity (BPD=83.9%; COM=85.0%, χ2(4)=2.64, p=.620), had an annual income less than $25,000 (BPD=75.0%; COM=38.3%, χ2(4)=16.72, p=.002), and were single or never married (BPD=73.2%; COM=64.4%, χ2(4)=7.56, p=.109).

Thirteen COM participants (21.7%) had a current anxiety disorder, nine (15.0%) a current substance use disorder, one (1.7%) a current mood disorder, and one (1.7%) met criteria for avoidant personality disorder. Thirty-six BPD participants (64.3%) had a current anxiety disorder, twenty-nine (51.8%) another personality disorder, twenty-two (39.3%) a current mood disorder, twenty-two (39.3%) a current substance use disorder, and four (7.1%) a current eating disorder. BPD participants were more likely than COM participants to meet criteria for all of the aforementioned comorbid diagnostic categories (all ps<.035).

Procedure

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Missouri (protocol 1133597), and written informed consent was provided prior to in-person participation. Diagnoses were determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) and the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1994). Interrater reliabilities, computed for a subsample of 20 participants, were strong for the diagnosis of BPD (κ=0.88), a current anxiety disorder (κ = .89), a current substance use disorder (κ = 1.00), a current alcohol use disorder (κ = 1.00), and moderate for any current mood disorder (κ = .77).

Eligible participants completed self-report questionnaires and were taught the AA procedures during an orientation session for which they were paid $10. AA data were then collected via electronic diaries (Palm Tungsten™ E2 handheld computer) that participants carried for approximately 21 days (M=21.6, SD=2.1). The electronic diaries prompted participants to answer questions randomly six times a day. In addition to the random prompts, event-contingent prompts for alcohol consumption, smoking, and non-suicidal self-injury were included. As interpersonal stressors were not assessed at the event-contingent prompts, these were not included in the present analyses. For information regarding the event-related prompts, see Lane et al. (2016). Participants were paid up to $50 after each week in the study depending on compliance, and were also paid $10 for completing additional self-report questionnaires at the end of the study. Compliance in this sample was high; participants on average completed 90.3% of the random prompts.

Measures

Negative affect

At each random prompt, participants rated their momentary affect on the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Extended version items (PANAS-X, Watson & Clark, 1999). Participants indicated the level of their affect within the past 15 minutes (1=very slightly/not at all, 5=extremely). Beyond the general negative/positive affect items, an additional 11 items to complete the hostility (6 items), sadness (5 items), and fear (6 items) scales were presented and items within each of the three scales were aggregated into mean scores for each person at any given prompt. For each person, individual day means were computed by averaging all the momentary scores within a day. These day means were then averaged into a person mean. Following Shrout and Lane (2012), we estimated multilevel reliability coefficients for each NA subscale. The reliabilities of individuals’ average affect ratings across the diary period were excellent (all RKFs>.88), reliabilities of any single time point rating were good (all RKRs>.84), and the reliabilities in the change of subscale ratings across time were adequate to good (all RCs>.72).

Interpersonal stressors

At each random prompt, participants indicated if they had felt rejected by or had had a disagreement with their romantic partner, boss/teacher, co-worker, roommate, friend, parent, sibling, child, or any other family member since last prompted (yes/no answer). The endorsements were aggregated into two dichotomous variables, indicating whether any rejection or any disagreement had occurred (as soon as participants selected rejection/disagreement for at least one interaction partner, this variable became 1, otherwise it was coded 0). The two momentary variables were aggregated by day to obtain two variables indicating the proportion of prompts where disagreement/rejection was endorsed. Lastly, these day means were aggregated by person to obtain two variables indicating the proportion of days on which disagreement/rejection was endorsed. In the BPD group, 359 rejection (7.9% of prompts) and 349 disagreement events (7.7% of prompts) were reported in total. COM participants reported a total of 110 rejections (2.2% of prompts) and 167 disagreements (3.3% of prompts). Between and within-person correlations for the NA scales and interpersonal events are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Data analysis

The data analytic design for the replication part of the study was identical to that of the original study (Hepp et al., 2017), employing a multivariate multi-level model. In model 1, momentary hostility, sadness, and fear were (simultaneously) predicted by momentary rejection and disagreement, interacted with group. Model 2 used the lagged scores of momentary rejection and disagreement (lagged by one prompt) and the difference score between current and lagged rejection/disagreement to predict current hostility, sadness, and fear (simultaneously). The lagged score was included to assess the effects of previous rejection/disagreement on current NA (which was assessed on average 2 hours later). The difference score was included because it mathematically adjusts for the current value of rejection/disagreement and thus helps to isolate the actual lagged effects of interest. The lagged and difference scores were interacted with a group dummy.

Both models statistically adjusted for the day- and person-level scores of rejection and disagreement, to ensure that we were able to isolate the momentary effects as intended. The day- and person level predictors were also interacted with the group variable. Both models further adjusted for the lagged criterion scores and included the covariates weekday, weekend (5PM Friday through 5PM Sunday), study day, and time elapsed since the participant awoke.

Momentary predictors were centered on the participant’s day mean, daily predictors on the person mean, and person-level predictors on the sample mean. Random intercepts were modelled for each person and day for each of the multivariate criteria. Analyses were performed in R using the lmer function from the package lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2014). Significance tests were conducted using the package lmerTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen, 2014). Model equations and results from power analyses for these models are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Results

Replication

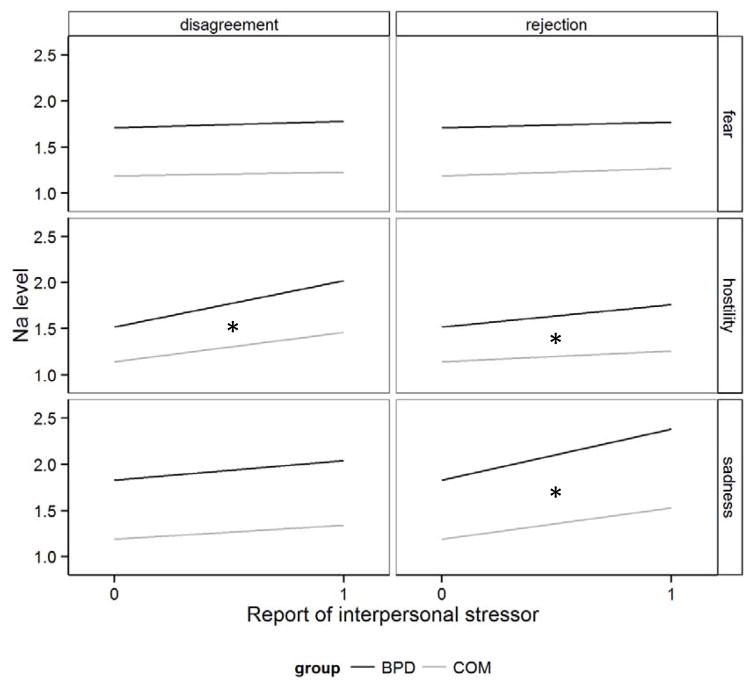

The concurrent effects of rejection, disagreement, and group on NA are presented in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 1. Momentary rejection showed a positive association with hostility and sadness in both groups, and these associations were significantly stronger for BPD individuals (rejection×Group on hostility: Est=0.13, β=0.04, SE=0.05, p=.009; rejection×Group on sadness: Est=0.21, β=0.06, SE=0.05, p<.001). Momentary disagreement was positively associated with hostility and sadness in both groups, and the association with hostility was significantly stronger for BPD individuals (disagreement×Group: Est=0.17, β=0.07, SE=0.04, p<.001). Pseudo R2 values, computed following Snijders and Bosker (2012), indicated that 21–26% of random effects and residual variance in the negative affects was explained by the predictors (R2hostility=.21, R2fear=.21, R2sadness=.26).

Table 1.

Estimates, standard errors, and p-values for group, rejection, and disagreement predicting hostility, sadness, and fear (simultaneously) in a multivariate multi-level model.

| Predictors | Hostility | Sadness | Fear | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borderline | Community | Borderline | Community | Borderline | Community | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| b | β | SE | p | b | β | SE | p | b | β | SE | P | b | β | SE | p | b | β | SE | p | b | β | SE | p | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Mom rej | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | .004 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .019 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | .067 |

| Day rej | 0.41 | 0.10 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.10 | <.001 | 1.25 | 0.23 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.80 | 0.13 | 0.14 | <.001 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.11 | <.001 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.05 | .037 |

| Person rej | 0.41 | 0.10 | 0.69 | .556 | 3.72 | 0.54 | 1.39 | .009 | 2.24 | 0.25 | 0.85 | .010 | 3.12 | 1.72 | 0.35 | .068 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.13 | .241 | 3.08 | 1.51 | 0.45 | .044 |

| Mom dis | 0.50 | 0.19 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | .003 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | .259 |

| Day dis | 0.84 | 0.20 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.08 | <.001 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.08 | <.001 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.05 | .006 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.03 | .226 |

| Person dis | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.72 | .295 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 1.18 | .718 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.91 | .621 | 0.06 | 1.46 | 0.01 | .965 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.11 | .324 | 0.68 | 1.28 | 0.09 | .596 |

| BPD group | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0.07 | .004 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.08 | <.001 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.55 | <.001 | ||||||||||||

Note. Mom=momentary, rej=rejection, dis=disagreement. The model adjusted for lagged hostility, sadness, and fear and the covariates weekday, weekend, study day, and time since participant awoke. Group was coded Borderline=0 for the Borderline columns and community=0 for the community columns. Significant group differences are highlighted in boldface.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the concurrent effects of momentary interpersonal stressors on negative affect, presented by group and separately for rejection and disagreement and for each of the negative affect criteria. Parameters used to generate the plot where extracted from Table 1. A ‘*’ indicates a significant difference between BPD and COM slopes.

Extension

Table 2 presents the effects of the lagged scores of rejection and disagreement (adjusted for their difference scores) on NA. Lagged rejection showed a positive association with hostility and sadness in both groups, with significantly stronger associations in the BPD group (lagged_rejection×Group on hostility: Est=0.24, β=0.08, SE=0.08, p=.002; lagged_rejection×Group on sadness: Est=0.32, β=0.09, SE=0.08, p<.001). Lagged disagreement was positively associated with hostility and sadness in both groups, and the association with hostility was significantly stronger in the BPD group (lagged_disagreement×Group: Est=0.21, β=0.08, SE=0.07, p=.002). The association between lagged disagreement and fear was positive only in the BPD group (lagged_disagreement×Group: Est=0.14, β=0.05, SE=0.07, p=.046). Pseudo R2 was .22 for hostility, R2=.26 for sadness, and R2=.21 for fear. We repeated both the concurrent and lagged model adjusting for comorbid anxiety disorders in both groups and for drinking events during the random prompts and all results replicated (see Supplementary Materials).

Table 2.

Estimates, standard errors, and p-values for group, lagged rejection and lagged disagreement predicting hostility, sadness, and fear (simultaneously) in a multivariate multi-level model.

| Predictors | Hostility | Sadness | Fear | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borderline | Community | Borderline | Community | Borderline | Community | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| b | β | SE | p | b | β | SE | p | b | β | SE | P | b | β | SE | p | b | β | SE | p | b | β | SE | p | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Rej lag | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.07 | .030 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.04 | .088 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 | .314 |

| Dis lag | 0.63 | 0.24 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.42 | 0.16 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.04 | .001 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | .909 |

| Rej diff | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.04 | .004 | 0.58 | 0.24 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | .028 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | .082 |

| Dis diff | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | .430 |

| BPD group | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.07 | .004 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.08 | <.001 | 0.26 | 0.55 | 0.07 | <.001 | ||||||||||||

Note. Mom=momentary, rej=rejection, dis=disagreement. The model adjusted for lagged hostility, sadness, and fear and the covariates weekday, weekend, study day, and time since participant awoke. Group was coded Borderline=0 for the Borderline columns and community=0 for the community columns. Significant group differences are highlighted in boldface.

Discussion

The present study replicated a study, which demonstrated positive associations of momentary hostility, sadness, and fear with rejection and disagreement in BPD individuals’ daily lives (Hepp et al., 2017). All six positive associations at the momentary level (rejection/disagreement each predicting hostility/sadness/fear) were replicated. These findings corroborate previous experimental and AA evidence of a positive relationship between NA and rejection (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2011; Dixon-Gordon et al., 2013; Sadikaj et al., 2013; Sadikaj et al., 2010) and between NA and disagreement (Chaudhury et al., 2017) in BPD. Extending previous work, Hepp et al. (2017) and the present study included both different subtypes of NA and different types of interpersonal stressors. Importantly, we employed a multivariate model, testing the effects of rejection and disagreement on all three affects simultaneously. This not only isolates unique variance attributable to rejection and disagreement as in models with a single criterion, but also adjusts model estimates and standard errors due to measurement correlation within and across the criteria. Note that all interaction effects except person-level rejection×group on hostility remained significant after correcting for multiple testing, following Benjamini and Hochberg (1995).

The original study used a depressed control group, whereas BPD individuals in the present study were compared to community controls. Regarding group differences, the disagreement-hostility association was replicated most closely; it was stronger in the BPD group at the momentary and day-level in both the original and current study. We further replicated a stronger day-level rejection-sadness association for BPD individuals, which extended to the momentary level in the current study, where the groups also differed. Lastly, we observed a stronger rejection-hostility association for BPD individuals at the momentary level, while the original study found this at the day level, corroborating previous evidence from experimental and AA studies (Beeney et al., 2014; Berenson et al., 2011; Chapman et al., 2015; Miskewicz et al., 2015; Renneberg et al., 2012).1

In the additional lagged models, lagged rejection and disagreement showed positive associations with subsequent hostility and sadness in both groups and lagged disagreement with fear in the BPD group. Importantly, the associations for rejection-hostility, rejection-sadness, disagreement-hostility and disagreement-fear were significantly stronger in the BPD group. Thus, in addition to the concurrent effects, interpersonal stressors were likely to impact NA that occurred on average 2 hours later. These stronger effects for the BPD group may illustrate the increased affective reactivity of BPD individuals that is postulated in theories of BPD (Crowell et al., 2009).

It is important to note that the effect sizes for group differences in the stressor-affect associations (reported in an r metric) ranged from very small to small when considering the total variation observed across moments, days, and persons. As such, one may interpret these effects as having relatively little impact, in an absolute sense, given the myriad people, places, and contexts individuals encounter in their everyday lives. While this is a valid interpretation, we would hesitate to minimize their meaningfulness. Hox (2010) and Snijders and Bosker (2012) warn against strict reliance on effect size estimates in clustered designs because the relative variances of the different levels are lost upon standardization. In the current data, there was generally three times the variability at the momentary level compared to the person level, and two times the variability at the daily level compared to the person level. Therefore, accounting for even small amounts of variability (e.g., 1–2% each) at a level of analysis where situations are constantly changing can be quite meaningful because such effects bring continuity and consistency to otherwise diverse and random contexts (cf. Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003). Indeed, though BPD individuals exhibit greater reactivity to interpersonal stressors to a relatively small extent compared to community individuals, the finding that they do so consistently across contexts illustrates that it is pervasive and could contribute to their overall generalized dysfunction.

Also noteworthy is that there were some associations that were not significantly different across groups, namely (concurrent and lagged) rejection-fear and disagreement-sadness. Nevertheless, a majority of these associations were statistically significant for both groups individually. These patterns similarly parallel the findings of Hepp et al. (2017) despite different comparison groups, suggesting that while there are robust associations in a transdiagnostic sense, there are certain combinations of interpersonal stressors and emotional reactions that are stronger for those with BPD. Further investigation regarding whether such effects are similar across other comparison groups or indeed different is needed.

Limitations and Implications

A major limitation of this study is that while the lagged models helped establish a time-sequence of events, we cannot say that interpersonal stressors are the cause for the observed NA increases at the following time-points. It is possible that other types of stressors (e.g. intrapersonal stressors such as negative memories) or those that occurred when data were not sampled account for a proportion of the observed affective changes. The different time frames of assessment for NA and rejection/disagreement also play into this limitation: NA was assessed for “the past 15 minutes”, whereas interpersonal stressors were reported “since the last prompt”, rendering the temporal ordering less clear than if both had been assessed with regard to “right now” (but likely at the cost of missing the majority of interpersonal stressors). A study design with more frequent or event-contingent sampling may further elucidate this relationship, and the combination of clinical and healthy control groups could establish further specificity for BPD. Future studies should also consider assessing the strength or impact of interpersonal stressors, as this may explain the magnitude of the affective change. It is possible that BPD individuals encounter more severe stressors or appraise them as such. Relatedly, the set of targeted interpersonal stressors should be extended beyond rejection and disagreement.

A further potential limitation is the inclusion criterion of weekly alcohol consumption, as alcohol use may have impacted the association of interpersonal stress and NA. Likewise, the high rate of comorbidity in BPD individuals and the presence of some psychopathology in COM individuals is a potential limitation, as it is unclear how psychopathology other than BPD may have contributed to the results. To account for potential influences of alcohol use and psychopathology beyond BPD, we repeated our analyses adjusting for current anxiety disorders (the most prominent psychopathology in both groups) as well as alcohol use. In both cases the results replicated (see Supplementary Materials). Nonetheless, even with regard to BPD pathology our sample was somewhat selective because it included BPD individuals that were currently in treatment. Thus, we may have sampled BPD individuals that were at the more severe end of the BPD continuum, who likely exhibit the strongest associations between the constructs of interest. If we had assessed BPD pathology dimensionally, the effects might have been smaller than the interaction effects we report. Ultimately, it would be instructive to replicate the present findings using a dimensional approach to BPD pathology.

In sum, the current results and Hepp et al. (2017) suggest that rejection and disagreement are positively associated with hostility, sadness, and fear in BPD. We demonstrated this relationship in BPD individuals’ daily lives at the momentary level, showing that NA is relatively higher at the same occasions that rejection/disagreement is reported, but also that NA remains elevated at follow-up prompts that occur on average two hours later.

Supplementary Material

General Scientific Summary.

The experience of intense and quickly changing negative emotions is a key symptom of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). We found that stressful interpersonal events, such as feeling rejected or having a disagreement, increase the intensity of negative emotions, especially anger, sadness, and fear, in the daily lives of individuals with BPD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health research grants R21 MH069472 (Trull), P60 AA11998 (Trull/Andrew C. Heath), T32 AA013526 (Sher).

Footnotes

A detailed discussion of day-and person-level effects is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package (Version 1.1–7) Journal of Statistical Software. 2014;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Beeney JE, Levy KN, Gatzke-Kopp LM, Hallquist MN. EEG asymmetry in borderline personality disorder and depression following rejection. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2014;5(2):178–185. doi: 10.1037/per0000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berenson KR, Downey G, Rafaeli E, Coifman KG, Paquin NL. The rejection–rage contingency in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(3):681–690. doi: 10.1037/a0023335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54(1):579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Dixon-Gordon KL, Butler SM, Walters KN. Emotional reactivity to social rejection versus a frustration induction among persons with borderline personality features. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2015;6(1):88–96. doi: 10.1037/per0000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury SR, Galfalvy H, Biggs E, Choo TH, Mann JJ, Stanley B. Affect in response to stressors and coping strategies: an ecological momentary assessment study of borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 2017;4(8):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40479-017-0059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Linehan MM. A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(3):495–510. doi: 10.1037/a0015616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Chapman AL, Lovasz N, Walters K. Too upset to think: The interplay of borderline personality features, negative emotions, and social problem solving in the laboratory. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2(4):243–260. doi: 10.1037/a0021799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL, Breetz A, Tull M. A laboratory-based examination of responses to social rejection in borderline personality disorder: the mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2013;27(2):157–171. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2013.27.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MG, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorder–patient ed. (SCID-I/P, Version 2) New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hepp J, Lane SP, Carpenter RW, Niedtfeld I, Brown WC, Trull TJ. Interpersonal Problems and Negative Affect in Borderline Personality and Depressive Disorders in Daily Life. Clinical Psychological Science. 2017;5(3):470–484. doi: 10.1177/2167702616677312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. 2. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models (Version 2.0–20). [Computer software] 2014 http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/index.html.

- Lane SP, Carpenter RW, Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Alcohol Craving and Consumption in Borderline Personality Disorder When, Where, and With Whom. Clinical Psychological Science. 2016;4(5):775–792. doi: 10.1177/2167702615616132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskewicz K, Fleeson W, Arnold EM, Law MK, Mneimne M, Furr RM. A contingency-oriented approach to understanding borderline personality disorder: Situational triggers and symptoms. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2015;29(4):486–502. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2015.29.4.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured interview for DSM-IV personality disorders. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Renneberg B, Herm K, Hahn A, Staebler K, Lammers CH, Roepke S. Perception of social participation in borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2012;19(6):473–480. doi: 10.1002/cpp.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadikaj G, Moskowitz D, Russell JJ, Zuroff DC, Paris J. Quarrelsome behavior in borderline personality disorder: Influence of behavioral and affective reactivity to perceptions of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(1):195–207. doi: 10.1037/a0030871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadikaj G, Russell JJ, Moskowitz D, Paris J. Affect dysregulation in individuals with borderline personality disorder: Persistence and interpersonal triggers. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2010;92(6):490–500. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.513287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout P, Lane SP. Psychometrics. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 302–320. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglmayr C, Grathwol T, Linehan M, Ihorst G, Fahrenberg J, Bohus M. Aversive tension in patients with borderline personality disorder: a computer-based controlled field study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;111(5):372–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Ebner-Priemer U. Ambulatory assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:151–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.