Abstract

A comprehensive public health strategy for adolescent suicide prevention includes upstream prevention strategies, strategies for risk recognition, and services for those at risk. Interpersonal trauma and substance use are important prevention targets as each is associated with risk for suicide attempts. Multiple prevention programs target these factors; however, the Family Check-Up, designed to reduce substance use and behavioral problems, also has been associated with reduced suicide risk. Several youth screening instruments have shown utility, and a large-scale trial is underway to develop a computerized adaptive screen. Similarly, several types of psychotherapy have shown promise, and sufficiently powered studies are underway to provide more definitive results. The climbing youth suicide rate warrants an urgent, concerted effort to develop and implement effective prevention strategies.

Introduction

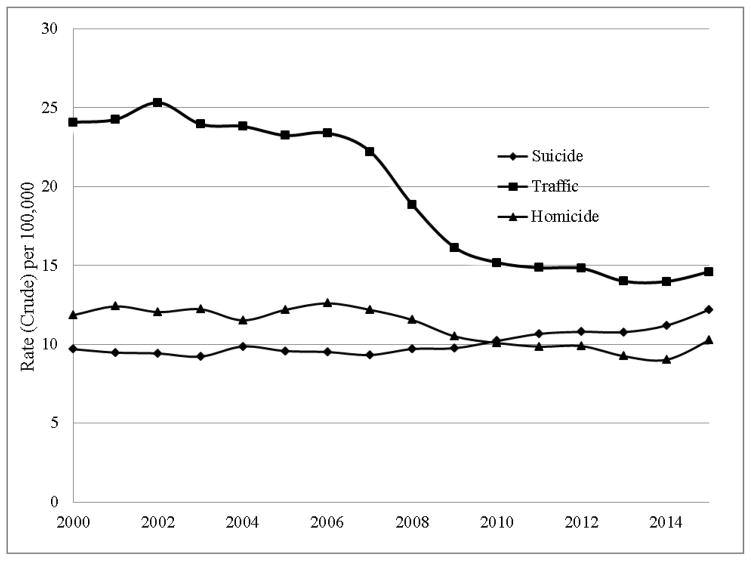

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults in the United States [CDC, 1] and the third leading cause of death in this age group worldwide [2]. Despite increasing attention to this problem [3], the rate of suicide in the United States (U.S.) has gradually increased since the turn of the century [CDC, 1]. In fact, among young people (ages 14–25 years), the change in rate from 9.70 in 2000 to 12.19 in 2015 (per year, per 100,000 people) reflects a 25.7% increase. This stands out dramatically when contrasted with the decline in traffic fatalities among young people in the U.S. during this same period (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Suicide, Traffic, and Homicide Rates for Youth, Ages 14–25, in the U.S., 2000–2015. These archival, de-identified data are reproduced from a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), Fatal Injury Reports, 2000–2015. Retrieved from https://cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal_injury_reports.html

A comprehensive report of suicide prevention strategies (societal, community, relationship and individual levels), with at least some evidence to suggest their potential effectiveness, was recently published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [4]. In the present article, we highlight selective research relevant to youth suicide prevention that aligns with two categories in this report: “Create Protective Environments” and “Identify and Support Those at Risk.” Few would dispute the societal value of (a) creating protective environments to reduce the likelihood of youth suicide risk, and (b) supporting youth already at elevated risk for suicide.

Create Protective Environments - Environmental and Family Contexts

We consider several possible targets for suicide prevention that relate to the physical, emotional, and/or behavioral safety of children’s environments. Positive changes in these contexts have the potential for a long-term impact on the prevalence of youth suicide.

Interpersonal Trauma/Violence

The prevention of early developmental adversities, such as interpersonal trauma, warrants focused consideration in relation to suicide prevention. Exposure to interpersonal trauma has been repeatedly linked with suicide risk. In a recent meta-analysis of 29 longitudinal studies of youth and young adults, ages 12–26, exposure to interpersonal violence (childhood maltreatment, bullying, dating and community violence) was linked prospectively to suicide attempts and deaths [5]. In fact, the investigators identified a 10-fold risk for suicide among youth exposed to interpersonal violence and argued that the elimination of childhood exposure to interpersonal violence would be associated with a 9% reduction in the rate of suicide attempts. This relation between exposure to physical and sexual abuse and suicide risk has been documented regardless of developmental stage of first exposure to maltreatment [6]. Recent meta-analyses also have reported that bully victimization and bully perpetration are both associated with suicidal ideation and attempts [7], and that the chronicity of victimization is associated with suicide risk, even when accounting for previous suicide risk factors [8].

Such research findings argue for the importance of developing evidence-based strategies to prevent child maltreatment and bullying/victimization, particularly as such upstream preventive interventions have the potential to impact a broad range of distal outcomes, including suicide risk [9]. Regarding interventions studied thus far, Positive Parenting Program interventions have been associated with improvements in parenting skills and self-efficacy [10]; child abuse prevention training for childcare professionals has resulted in improved knowledge, attitudes, and preventive behaviors [11]; and school-based programs have been associated with increases in children’s self-protective skills and knowledge [12]. However, taking into consideration the publication bias against studies with non-significant findings, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials did not find significant effects of intervention programs on the prevention or reduction of child maltreatment [13]. In the area of bullying prevention, a recent meta-analysis considered the effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs and reported modest program-related reductions in bullying and victimization frequency [14]. As research on the prevention of childhood maltreatment and bullying/victimization moves forward, it is recommended that researchers incorporate suicide-related outcomes in their studies [15]. There is currently much research activity in this area, and bullying prevention programs currently under development are incorporating online education with tailoring to youths’ bullying experiences [16] and text-messaging-based information, practice, and encouragement [17].

Alcohol and Drug Use

Alcohol and other substance use availability, including opportunities for use, are reflections of environmental and family contextual risk as well as adolescent behavioral choices. Alcohol use differentiates groups of youth who experience suicide thoughts from those who have made a suicide attempt [18]. Similarly, illicit drug use has been associated concurrently with suicide attempts among adolescents [19], and injection substance use among adolescents has been associated with increased risk for making a suicide attempt [20]. Given the challenges in distinguishing those who only think about suicide from those who make a suicide attempt [21], this research suggests that substance use facilitates the transition from ideation to action and points to an intervention target among youth experiencing suicidal ideation.

The Family Check-Up (FCU) is a school-based prevention program designed to reduce substance use and behavioral problems among adolescents [22]. Combining universal, selected, and indicated interventions, FCU targets parenting skills and family functioning. In a randomized, controlled study with 6th grade students, engagement in FCU was associated with reductions in suicide risk (thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, ideation with a plan, suicide attempt) at two time points in young adulthood [23]. This is an excellent example of the re-analysis of outcome data to determine cross-over effects for suicide-related outcomes.

Reducing Access to Lethal Means

Means restriction interventions can include large-scale policies that make it difficult for youth to access lethal weapons, medications, or environments [24], or counseling focused on removing dangerous items from the environment. Means restriction counseling conducted in pediatric emergency settings has been found to be acceptable to staff and parents, and to result in parental behavior changes [25]. Following a 1.5-hour online training for clinicians, 89% of eligible youth received lethal means counseling; follow-up interviews suggested that parents retained the message and acted to restrict lethal means in the home [25]. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that means restriction counseling is rarely used, even in the presence of suicide risk [26]. Increased attention is needed to workforce training and the dissemination of feasible, culturally sensitive means restriction practices.

Identify and Support Youth at Risk for Suicide

Recognizing and Responding to Youth at Risk

One strategy for facilitating the recognition of youth at risk for suicide is to train community members, “gatekeepers” in recognizing youth at risk and responding in a manner that is supportive and facilitates linkage to services [4]. At a population level, the multi-state evaluation of the Garrett Lee Smith (GLS) Youth Suicide prevention grant indicated that gatekeeper training was associated with a one-year reduction in youth suicide deaths and non-lethal suicide attempts [27, 28]. Although not a randomized trial design and with variability in programming between counties, analyses controlled for demographic variation between counties. Unfortunately, differences were not maintained; rates of suicide and suicide attempts did not differ between intervention and comparison counties two years after the training [27, 28]. Other studies suggest that longer trainings may improve case identification and referrals for treatment [29, 30]. Taken together, research indicates a modest, short-term benefit for gatekeeper training, suggesting its potential value as one component of a broader suicide prevention safety net.

A related strategy for the possible recognition of suicide risk involves social media. Evidence suggests that youth and young adults are using social media platforms to communicate suicidal thoughts or intent [e.g., 31]. Recent initiatives, such as the options provided by Facebook to flag concerning posts and access support services, suggest the potential of social media to play a preventive role [32]. Most research to date, however, has been descriptive or focused on the feasibility or effectiveness of case identification approaches [33]. An example of this is a study that reported the potential of a machine learning algorithm to identify individuals at high risk for suicide based on Twitter data [e.g., 34]. Empirical studies are needed to ascertain the impact of these approaches on youth suicide risk.

A third strategy for facilitating the recognition of youth suicide risk is proactive, suicide risk screening, which has been implemented in multiple settings with a variety of screening tools [35, 36]. The ASQ [Ask Suicide-Screening Questions; 37] is a 4-item instrument with questions about current suicidal ideation (better off dead, wish to die, current thoughts of suicide) and history of suicide attempt. In a recent study enrolling youth who presented to a pediatric ED with psychiatric complaints, Ballard and colleagues [38] found evidence for the feasibility of screening and demonstrated high sensitivity for the prediction of return ED visits for suicide-related complaints, although specificity was limited. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale [CSSRS; 39] is another commonly used screening and risk assessment instrument that has also shown reasonably good psychometric properties for the prediction of return ED visits for suicide-related complaints [40]. Nevertheless, because suicidal ideation is only a modest predictor of suicide attempts within clinical samples of adolescents [41] and has failed to predict suicide attempts among males in the year following their psychiatric hospitalization [42], a multi-component measure that goes beyond screening for suicidal ideation and previous suicide attempts may be important. Using the Tri-Risk Factor screen, which also considers co-occurring depression and alcohol/substance abuse as a positive screen [43], King and colleagues documented the utility of screening youth for suicide risk in medical emergency departments and the predictive importance of number of positive risk indicators endorsed [44]. Finally, an NIMH-funded study, Emergency Department Screen for Teens at Risk for Suicide (ED-STARS), is currently being implemented to develop and validate a computerized adaptive screen – brief and tailored -- for teen suicide risk [45].

Reducing Suicide Risk Using Psychotherapy and Brief Interventions

Despite consensus on the need for suicide-specific interventions, there are currently no well-established treatments (positive results of two independent randomized controlled trials) shown to reduce or prevent suicide-related thinking, behavior or deaths by suicide in youth [46]. Nevertheless, there are several promising psychotherapy approaches [46, 47]. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents (DBTA), based on a biosocial theory, is a modification of the adult focused DBT treatment [48]. DBTA includes individual treatment for affect regulation and distress tolerance, behavioral chain analyses to address self-harming behaviors, skill building, family work, and consultation [49]. Recent findings from pre-post studies with American Indian/Alaskan Native teens in a residential substance abuse facility [50] and youth seeking services in an intensive outpatient setting [51] demonstrated clinically significant improvements, and a recently completed NIMH-funded randomized controlled clinical trial will provide critical additional information about the efficacy of DBTA [52].

Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT) draws on family systems, attachment, and developmental theories to target adolescent’s relationship with parents [53]. Studies have demonstrated benefits of ABFT relative to waitlist control or treatment as usual (TAU) in reducing teen’s depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation [e.g., 54]. ABFT has also been examined for feasibility and acceptability as an after-care intervention for youth recently discharged from a psychiatric inpatient unit for suicide-related risk and for youth with comorbid considerations [55]. A NIMH-funded randomized controlled clinical trial of ABFT (vs. non directive supportive therapy with parent psychoeducation) will provide important additional information [56].

The Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youth Program (SAFETY) [57, 58] is a cognitive-behavioral and DBT-informed 12-week intervention that recruits suicide attempting/self-harming youth, linking them to both an individual and family therapist. Treatment goals include increasing protective supports, decreasing suicide-related behaviors, safety planning, and means restriction. A small, nonrandomized intervention development trial of 35 youth demonstrated promising effects [58]. In the first RCT of SAFETY, 42 youth with a history of suicide attempt or self-harm in the past 3 months were assigned to SAFETY or Enhanced TAU [57]. At 3-month follow-up, participation in SAFETY significantly lowered the risk of a suicide attempt.

Although there is more to learn, evidence is accumulating to support the promise of suicide risk screening and suicide-specific therapeutic interventions for youth. Moreover, several adequately sized and powered federally funded trials are currently underway that will provide important new information.

Conclusions

Additional research is necessary to inform the development of an effective and comprehensive public health approach to adolescent suicide prevention. This is likely to include upstream prevention strategies, strategies for the recognition of suicide risk, and treatment and related services for those at risk. We argue that our adolescent suicide prevention research portfolio should include a focus on the prevention of interpersonal violence and substance abuse, as well as the promotion of safe environments for children and adolescents. It also should include sufficiently powered, independently conducted replication trials for promising screening instruments, psychotherapies, and brief interventions. The climbing adolescent suicide rate warrants an urgent, concerted effort to develop, disseminate, and implement more effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Highlights.

Interpersonal violence and substance use are risks for youth suicide attempts.

The Family Check-Up program has been associated with reduced suicide risk.

Means restriction education is associated with parental behavior change.

Suicide risk screening tools can identify previously unrecognized suicide risk.

Several psychotherapies targeting youth suicide risk have shown promise.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Taylor McGuire for her superb assistance with literature searches and referencing.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. More than 1.2 million adolescents die every year, nearly all preventable. 2017 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/yearly-adolescent-deaths/en/

- 3.Suicide Prevention Resource Center, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. Zero Suicide in health and behavioral health care. 2015 Available from: http://zerosuicide.sprc.org.

- 4.Stone DM, Holland KM, Bartholow BN, Crosby AE, Davis SP, Wilkins N. Preventing suicide: A technical package of policies, programs, and practice. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5**.Castellví P, Miranda-Mendizábal A, Parés-Badell O, Almenara J, Alonso I, Blasco MJ, … Alonso J. Exposure to violence, a risk for suicide in youths and young adults. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2017;135(3):195–211. doi: 10.1111/acps.12679. The authors conducted a meta-analysis of 29 studies to assess the association and magnitude of effects between early exposure to interpersonal violence and subsequent suicide attempt and suicide death. Results indicate that such early exposure confers significant risk for both suicide attempts and suicide death, suggesting that child maltreatment and other forms of victimization are important targets for suicide prevention. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez SH, Tse J, Wang Y, Turner B, Millner AJ, Nock MK, Dunn EC. Are there sensitive periods when child maltreatment substantially elevates suicide risk? Results from a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Depression and anxiety. 2017 doi: 10.1002/da.22650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt MK, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Polanin JR, Holland KM, DeGue S, Matjasko JL, … Reid G. Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e496–e509. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8*.Geoffroy M-C, Boivin M, Arseneault L, Turecki G, Vitaro F, Brendgen M, … Côté SM. Associations between peer victimization and suicidal ideation and suicide attempt during adolescence: Results from a prospective population-based birth cohort. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;55(2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.11.010. Using a general population sample of children born in Quebec, the authors examined whether adolescents who are victimized by peers are at heightened risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Results indicated that victimization is associated with increased risk even after taking into account current levels of suicidality and mental health problems. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reider EE, Sims BE. Family-based preventive interventions: Can the onset of suicidal ideation and behavior be prevented? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2016;46(Supplemental 1):S3–S7. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poole MK, Seal DW, Taylor CA. A systematic review of universal campaigns targeting child physical abuse prevention. Health Education Research. 2014;29(3):388–432. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rheingold AA, Zajac K, Chapman JE, Patton M, de Arellano M, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Child sexual abuse prevention training for childcare professionals: An independent multi-site randomized controlled trial of stewards of children. Prevention Science. 2015;16(3):374–385. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh K, Zwi K, Woolfenden S, Shlonsky A. School-based education programs for the prevention of child sexual abuse. Research on Social Work Practice. 2015:1–23. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004380.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Euser S, Alink LR, Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. A gloomy picture: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reveals disappointing effectiveness of programs aiming at preventing child maltreatment. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2387-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiménez-Barbero JA, Ruiz-Hernández JA, Llor-Zaragoza L, Pérez-García M, Llor-Esteban B. Effectiveness of anti-bullying school programs: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;61:165–175. [Google Scholar]

- 15.King CA. Asking or not asking about suicidal thoughts. The possibility of "added value" research to improve our understanding of suicide. APA Monitor on Psychology. 2016;47(7):36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timmons-Mitchell J, Levesque DA, Harris LA, III, Flannery DJ, Falcone T. Pilot test of StandUp, an online school-based bullying prevention program. Children & Schools. 2016;38(2):71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ybarra ML, Prescott TL, Espelage DL. Stepwise development of a text messaging-based bullying prevention program for middle school students (bullydown) JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2016;4(2):e60. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McManama O’Brien KH, Becker SJ, Spirito A, Simon V, Prinstein MJ. Differentiating adolescent suicide attempters from ideators: Examining the interaction between depression severity and alcohol use. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2014;44(1):23–33. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ammerman BA, Steinberg L, McCloskey MS. Risk-taking behavior and suicidality: The unique role of adolescent drug use. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016:1–11. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1220313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Liu RT, Case BG, Spirito A. Injection drug use is associated with suicide attempts but not ideation or plans in a sample of adolescents with depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;56:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klonsky ED, May AM. Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: a critical frontier for suicidology research. Suicide and life-threatening behavior. 2014;44(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Kavanagh KA. Everyday parenting: A professional’s guide to building family management skills. Research Press Publishers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23**.Connell AM, McKillop HN, Dishion TJ. Long-term effects of the family check-up in early adolescence on risk of suicide in early adulthood. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2016;46(Supplemental 1):S15–S22. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12254. The authors longitudinally examined the effects of the Family Check-Up, a school-based, family-focused program designed to reduce substance use and behavior problems. The progrm was associated with reduced suicide risk at ages 18–19 and ages 28–30 years. This study documents the crossover effects of this program on suicide risk and the potential importance of early preventive interventions as a strategy for reducing suicide. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barber CW, Miller MJ. Reducing a suicidal person’s access to lethal means of suicide: A research agenda. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;47(3):S264–S272. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Runyan CW, Becker A, Brandspigel S, Barber C, Trudeau A, Novins D. Lethal means counseling for parents of youth seeking emergency care for suicidality. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(1):8–14. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.11.28590. The authors trained psychiatric emergency clinicians to provide lethal means counseling to parents of children seeking emergency services due to suicide risk. Parents were receptive to the counseling, resulting in most parents reportedly locking up medications or guns in their homes. These findings demonstrate the feasibility and potential value, in terms of suicide prevention, of adding a counseling protocol to the discharge process within pediatric psychiatric emergency services. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers SC, DiVietro S, Borrup K, Brinkley A, Kaminer Y, Lapidus G. Restricting youth suicide: Behavioral health patients in an urban pediatric emergency department. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2014;77(3):S23–S28. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walrath C, Garraza LG, Reid H, Goldston DB, McKeon R. Impact of the Garrett Lee Smith youth suicide prevention program on suicide mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(5):986–993. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Godoy Garraza L, Walrath C, Goldston DB, Reid H, McKeon R. Effect of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Suicide Prevention Program on suicide attempts among youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(11):1143–1149. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1933. The authors examined the impact of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Suicide Prevention Program (GLS program) by comparing counties that implemented GLS with counties that shared key characteristics but were not exposed to GLS. The GLS counties reported lower suicide attempt rates the year following program implementation; these differences were not sustained the following year. This study demonstrates the effectiveness of GLS activities and the probable importance of sustaining them over time for continued impact. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Condron DS, Garraza LG, Walrath CM, McKeon R, Goldston DB, Heilbron NS. Identifying and referring youths at risk for suicide following participation in school-based gatekeeper training. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2015;45(4):461–476. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ewell Foster CJ, Burnside AN, Smith PK, Kramer AC, Wills A, King CA. Identification, response, and referral of suicidal youth following Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2016 doi: 10.1111/sltb.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cash SJ, Thelwall M, Peck SN, Ferrell JZ, Bridge JA. Adolescent suicide statements on MySpace. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16(3):166–174. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bever L. Facebook hopes artificial intelligence can curb the ‘terribly tragic’ trend of suicides. The Intersect. 2017 Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2017/02/08/why-mental-health-professionals-say-live-streaming-suicides-is-a-very-concerning-trend/?utm_term=.34b9f72ebe73.

- 33.Robinson J, Cox G, Bailey E, Hetrick S, Rodrigues M, Fisher S, Herrman H. Social media and suicide prevention: a systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015;10(2):103–121. doi: 10.1111/eip.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braithwaite SR, Giraud-Carrier C, West J, Barnes MD, Hanson CL. Validating machine learning algorithms for twitter data against established measures of suicidality. JMIR Mental Health. 2016;3(2) doi: 10.2196/mental.4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horowitz LM, Ballard ED, Pao M. Suicide screening in schools, primary care and emergency departments. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2009;21(5):620–627. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283307a89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.King CA, Ewell Foster C, Rogalski KM. Teen suicide risk: A practitioner guide to screening, assessment, and management. Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, Ballard E, Klima J, Rosenstein DL, … Pao M. Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): A brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166(12):1170–1176. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballard ED, Cwik M, Van Eck K, Goldstein M, Alfes C, Wilson ME, … Wilcox HC. Identification of at-risk youth by suicide screening in a pediatric emergency department. Prevention Science. 2017;18(2):174–182. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0717-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, … Shen S. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gipson PY, Agarwala P, Opperman KJ, Horwitz AG, King CA. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): Predictive validity with adolescent psychiatric emergency patients. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2015;31(2):88–94. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huth-Bocks AC, Kerr DCR, Ivey AZ, Kramer AC, King CA. Assessment of psychiatrically hospitalized suicidal adolescents: Self-report instruments as predictors of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(3):387–395. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802b9535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King CA, Jiang Q, Czyz EK, Kerr DC. Suicidal ideation of psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents has one-year predictive validity for suicide attempts in girls only. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42(3):467–477. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9794-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.King CA, O’Mara RM, Hayward CN, Cunningham RM. Adolescent suicide risk screening in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009;16(11):1234–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King CA, Berona J, Czyz E, Horwitz AG, Gipson PY. Identifying adolescents at highly elevated risk for suicidal behavior in the emergency department. Journal of Child Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2015;25(2):100–108. doi: 10.1089/cap.2014.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Institute of Mental Health. Personalized screen to ID suicidal teens in 14 ERs: Aimed to help front-line clinicians save lives. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glenn CR, Franklin JC, Nock MK. Evidence-based treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Clinician’s Research Digest: Child and Adolescent Populations. 2015;33(3):3. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54(2):97–107. e102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mehlum L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg M, Haga E, Diep LM, Laberg S, … Sund AM. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(10):1082–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. Guilford Press; 2007. Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beckstead DJ, Lambert MJ, DuBose AP, Linehan M. Dialectical behavior therapy with American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents diagnosed with substance use disorders: Combining an evidence based treatment with cultural, traditional, and spiritual beliefs. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;51:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.James S, Freeman K, Mayo D, Riggs M, Morgan JP, Schaepper MA, Montgomery SB. Does insurance matter? Implementing dialectical behavior therapy with two groups of youth engaged in deliberate self-harm. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2015;42(4):449–461. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0588-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Institutes of Health. Project information: Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for adolescents with bipolar disorder. 2016 Available from: https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=9029354&icde=29474674&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=2&csb=default&cs=ASC.

- 53.Ewing ESK, Diamond G, Levy S. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed and suicidal adolescents: theory, clinical model and empirical support. Attachment & Human Development. 2015;17(2):136–156. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2015.1006384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, Diamond GM, Gallop R, Shelef K, Levy S. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(2):122–131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diamond GS, Russon J, Levy S. Attachment-based family therapy: A review of the empirical support. Family Process. 2016;55(3):595–610. doi: 10.1111/famp.12241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Institutes of Health. Project information: Attachment-Based Family Therapy for suicidal adolescents. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asarnow JR, Hughes JL, Babeva KN, Sugar CA. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment for suicide attempt prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58*.Asarnow JR, Berk M, Hughes JL, Anderson NL. The SAFETY Program: a treatment-development trial of a cognitive-behavioral family treatment for adolescent suicide attempters. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(1):194–203. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.940624. The authors conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of the Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youths (SAFETY) program, a cognitive-behavioral DBT-informed family treatment aimed at reducing suicide attempt (SA) risk. Results support the safety and efficacy of SAFETY for reducing SA risk among youths presenting to the emergency department with SA or self-harm. This study suggests that cognitive behavioral therapy with a family component can be helpful to youth at risk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]