Abstract

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) plays fundamental roles in male and female fertility. FSH is a heterodimeric glycoprotein expressed by gonadotrophs in the anterior pituitary. The hormone-specific FSHβ-subunit is non-covalently associated with the common α-subunit that is also present in the luteinizing hormone (LH), another gonadotrophic hormone secreted by gonadotropes and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secreted by thyrotrophs. Several decades of research led to the purification, structural characterization and physiological regulation of FSH in a variety of species including humans. With the advent of molecular tools, availability of immortalized gonadotroph cell lines and genetically modified mouse models, our knowledge on molecular mechanisms of FSH regulation has tremendously expanded. Several key players that regulate FSH synthesis, sorting, secretion and action in gonads and extra-gonadal tissues have been identified in a physiological setting. Novel post-transcriptional and post-translational regulatory mechanisms have also been identified that provide additional layers of regulation mediating FSH homeostasis. Recombinant human FSH analogs hold promise for a variety of clinical applications, whereas blocking antibodies against FSH may prove efficacious for preventing age-dependent bone loss and adiposity. It is anticipated that several exciting new discoveries uncovering all aspects of FSH biology will soon be forthcoming.

Keywords: Pituitary, FSH, LH, Testis, Ovary, Extra-gonadal, Reproduction, MiRNA, Transgenic Mice

Introduction

Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) is a critical regulator of reproductive physiology. It is a heterodimeric glycoprotein that consists of two distinct subunits, α and β. The α-subunit is common to all pituitary and placental glycoprotein hormones whereas the β-subunit is hormone-specific and the heterodimer confers biological activity. The overall regulation of FSH involves control at the level of subunit gene transcription, translation, dimer assembly, formation of different isoforms that influence synthesis and release, and physiological functions (Bousfield, et al. 2006; Narayan, et al. 2018; Pierce and Parsons 1981; Ulloa-Aguirre, et al. 2017). While earlier research has established FSH as an indispensable player in proper functioning of the reproductive axis, recent findings indicate its much wide-spread actions. In this review, we provide the molecular mechanisms driving each phase of FSH regulation from the initiation of its synthesis to ultimate physiological effects, with a focus on identifying the interlink between the encompassing effector pathways.

1. Transcriptional regulation of α-glycoprotein hormone subunit - encoding gene

The α-subunit is expressed in trophoblast, gonadotroph and thyrotroph cell types, and its expression is differentially regulated depending on the specific pituitary or placental cell type. An earlier study showed that a short 18-bp sequence serves as a cAMP response element that is independent of other regulatory elements around the 5′ flanking region of the human CGA promoter (Silver, et al. 1987). In fact, proteins that bind to this cAMP response element positively regulate the alpha subunit gene by cooperative interaction (Nilson, et al. 1989). Another study suggested that placenta-specific expression of human CGA may be evolutionary outcome of a functional cAMP response element whereas a different cis-acting element might be responsible for its expression in the pituitary (Bokar, et al. 1989). It is also known that gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH), produced by the hypothalamus, is a key regulator of Cga mRNA expression (Burrin and Jameson 1989). Transcription of Cga in cultured rat pituitary cells was found to be altered upon pulsatile GnRH administration (Shupnik 1990). Later, two DNA elements were identified that were involved in GnRH mediated expression of the mouse Cga (Schoderbek, et al. 1993). Moreover, the co-localization of GnRH and phorbol myristate acetate (an activator of protein kinase C) responsiveness indicate that the effect of GnRH on transcriptional regulation of mouse Cga is most likely through the PKC pathway.

Various groups also investigated signaling pathways in addition to deciphering DNA elements and transcription factors to better understand their regulatory mechanisms. Maurer et al. identified two unrelated DNA elements and designated them as GnRH-response element (GnRH-RE), an element that was adequate to allow GnRH response, and a pituitary glycoprotein hormone basal element (PGBE), that enhanced basal expression of the α-subunit (Maurer, et al. 1999). GnRH-RE was found to encompass a consensus binding region for the E26 transformation-specific (Ets) family of transcription factors and demonstrated that GnRH induced activation of MAPK pathway, mediated by GnRH-RE, is required and also sufficient enough for the transcriptional activation of Cga gene. Recently it was established that GnRH mediated activation of Cga expression requires stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1) and mitogen through an epigenetically regulated mechanism involving histone modifications (Haj, et al. 2017).

Other than GnRH associated response elements, two upstream regions of the Cga gene were identified that distinctly regulate its basal promoter transcription and PMA-stimulated promoter activity independently in mature gonadotroph cells. Steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) is involved in mediating these activities through its binding site in the promoter (Fowkes, et al. 2002). Fowkes et al. have also shown that GATA factors may be related to ERK activation of transcription and PKC-induced transcription relies partially on ERK interaction on elements downstream of −244 bp of the promoter. Another study from this group reported that SF-1 also significantly increases forskolin-stimulated Cga transcription and a phosphorylation site at the Serine 203 residue seems to be necessary for the activity (Fowkes and Burrin 2003). A recent study has identified the Msh homeobox 1 (Msx1) as a negative regulator that represses the gonadotroph-specific Cga expression. A decline in Msx1 expression in a temporal manner relieves this repression allowing production of the gonadotropic hormones (Xie, et al. 2013). Another study validated the role of Msx1 as a transcription repressor of the Cga gene and demonstrated that the mechanism by which Msx1 regulates inhibition of Cga gene expression involves its interaction with the TATA-binding protein in thyrotrophs (Park, et al. 2015). Other important factors of Cga gene regulation includes Sine oculis-related homeobox 3 (SIX3) homeodomain transcription factors that represses transcription of the alpha subunit in immature gonadotroph cell lines (Xie, et al. 2015).

2. Transcriptional regulation of FSHβ subunit-encoding gene

The β-subunit of FSH confers the specific biological activity of FSH dimer. Hence synthesis of the FSHβ subunit subunit is a rate-limiting step for the production of the biologically active FSH (Papavasiliou, et al. 1986). The production of FSHβ subunit is under tight regulation, and one of the most important points of control is at the level of FSHβ - encoding gene transcription. Its expression is also under a critical temporal regulation as FSHβ - encoding mRNA level was observed to increase about 4 to 5- fold during afternoon of proestrous while the increase was about 3-fold during estrus in rodents (Halvorson, et al. 1994; Ortolano, et al. 1988). Among many regulatory factors, GnRH and activins are key players in controlling FSHβ expression and these both act through independent as well as related pathways.

Regulation of FSHβ - encoding gene expression by GnRH

GnRH is released in a pulsatile manner from neurons in the hypothalamus and reaches pituitary via the hypophyseal-portal system. GnRH receptor is specifically expressed by the gonadotroph cells (Kaiser, et al. 1997; Stojilkovic, et al. 1994; Tsutsumi, et al. 1992). GnRH pulse frequency determines the rate of FSHβ production as many studies have shown that a decrease in GnRH pulse frequency favors FSHβ production over that of LHβ (Dalkin, et al. 2001; Dalkin, et al. 1989; Haisenleder, et al. 1988). FSH levels in serum are reduced by 60–90% in mice without GnRH (Mason, et al. 1986) and administration of GnRH to rats increased Fshb mRNA expression by four-fold (Dalkin et al. 2001), indicating that GnRH regulation of FSHβ takes place at the level of transcription.

Of the several proposed effector pathways by which GnRH regulates mouse FSHβ expression, the major ones include PKC and MAPK signaling pathways (Bonfil, et al. 2004; Coss, et al. 2004; Liu, et al. 2005). The GnRH ligand binding activates GnRH receptors (GnRHR) which increase the activities of calcium/calmodulin kinase II and protein kinase C (PKC) (Haisenleder, et al. 2003; Liu, et al. 2002) via activation of Gq and G11 family of G- proteins (Stanislaus, et al. 1997). GnRHR activation also initiates induction of distinct mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, namely ERK1/2, p38 and JNK (Liu et al. 2002; Roberson, et al. 1995; Sundaresan, et al. 1996). Activation of the MAPK pathway is achieved via PKC (Naor 2009) or through GnRHR association with Raf and calmodulin, which play a key role in mediating Ca2+ action on ERK activation, independent of the phospholipase C activity (Roberson, et al. 2005).

GnRH also regulates FSHβ expression via induction of immediate early genes (IEGs), which includes Jun, Fos, Atf3 and Egr1. One such IEG product is activator protein-1 (AP-1) which consists various Fos and Jun dimeric isoforms (c-Fos, Fra-1, Fra-2, FosB, c-Jun, JunB and JunD) that are induced by GnRH (Kakar, et al. 2003; Wurmbach, et al. 2001). Regulation of Jun and Atf3 by GnRH requires calcium, calcineurin, and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) that confers responsiveness to various genes responsible for FSH synthesis (Binder, et al. 2012). Strahl et.al. identified two AP-1 binding sites within the ovine Fshb promoter sequence that are sufficient enough to stimulate its expression independently (Strahl, et al. 1997; Strahl, et al. 1998). MAPK- mediated GnRH induction of murine Fshb takes place via AP-1interactive sites, where c-Jun and FosB binds to induce the promoter (Coss et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2002). AP-1 proteins have also been shown to regulate human Fshb promoter activity via two specific response elements (Wang, et al. 2008). Integrated GnRH response also requires factors that are associated with basal Fshb expression, like nuclear transcription factor Y (NF-Y) in mouse and upstream stimulatory factor 1 (USF1) in rat, and the mechanism involves interactions of these factors with AP-1 (Ciccone, et al. 2008; Coss et al. 2004). c-Fos knockout mice demonstrate small ovaries and atretic follicles (Johnson, et al. 1992), similar to phenotypes of Fshb knockout mice (Kumar, et al. 1997) indicating a possible key role of this proto-oncogene in regulation of FSHβ. GnRH is also reported to increase c-Fos half-life, thus in turn resulting in increased FSHβ expression (Reddy, et al. 2013). In addition to these factors, the CREB transcription factor was found to be involved in GnRH regulated Fshb expression in rats through interaction at a homologous CRE/AP-1 site (Ciccone et al. 2008), although mice deficient in CREB exhibit unaltered FSH levels suggesting a species-specific role of this factor. It is further demonstrated that inducible cAMP early repressors (ICER) antagonize the CREB stimulatory action to attenuate Fshb transcription at high GnRH pulse frequencies (Ciccone, et al. 2010). It has been recently reported that ICER influenced GnRH control of Fshb expression is mediated via ERK1/2 regulatory pathway (Thompson, et al. 2016).

GnRH stimulation was recently shown to increase intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) via NOX/DUOX mediated activity, suggesting a new concept of ROS involvement as a signaling intermediate in response to GnRH induction (Kim and Lawson 2015). This finding further opens up the possibility that ROS generated by other processes may also influence GnRH stimulation of FSH expression. GnRH induces β-catenin, a classical intermediate of the WNT signaling pathway, which is shown to influence FSHβ production in a murine model (Boerboom, et al. 2015). Another proposed factor is phosphoprotein-enriched in astrocytes 15 (PEA-15) an ERK scaffolding protein present in cytosol. It was suggested to mediate convergence of PKC and MAPK/ERK pathways induced by GnRH (Choi, et al. 2011). GABA alpha4beta3delta receptor agonist DS1 was recently reported to stimulate FSHβ expression in association with the ERK signaling pathway through the activation of Gnrhr promoter (Mijiddorj, et al. 2015). In an alternate mechanism, it was suggested that GnRH regulation of Homer protein homolog 1 (Homer 1) splicing may contribute to FSH expression (Wang, et al. 2014b).

Regulation of FSHβ expression by activin - follistatin - inhibin loop

Activin is a dimeric peptide composed of two identical beta subunits that can have two major isoforms, βA and βB. Activins were identified as gonadal peptides which stimulate the production of FSH (Ling, et al. 1986; Vale, et al. 1986). They bind to the type II receptor, resulting in phosphorylation of the type I receptor (Attisano and Wrana 2002). which then consequently phosphorylates the intracellular proteins Smad2 and Smad3 initiating the signal response cascade. The phosphorylated proteins bind to Smad4 and forms the “activating complex”, which is then translocated to the nucleus where it binds DNA through a direct interaction of Smad-binding elements (SBE) with specific domains on Smad3 and Smad4 (Massague 1998; Shi, et al. 1998) to induce transcription of the FSHβ-encoding gene (Bernard and Tran 2013). It was previously reported that activin induces increased FSH release from the pituitary (Ling et al. 1986) and FSHβ expression in gonadotropes (Weiss, et al. 1995). Three prominent activin-response elements have been identified in the FSHβ-encoding gene promoter region till date. A classical Smad-binding consensus sequence at −267, consisting a palindrome GTCTAGAC, was first proposed to be an important response element in rodents (Bernard 2004; Gregory, et al. 2005; Suszko, et al. 2005), but was later on found to have no significant contribution in activin induction of Fshb (Coss, et al. 2007; McGillivray, et al. 2007). This specific site is not present in human FSHB promoter. Bailey et al. identified three separate elements associated with FSHβ-encoding gene promoter which were essential for activin induction, and these proximal sites are found to be present in all species examined (Bailey, et al. 2004). SMAD associated factors, like Pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 1 (Pbx1) and PBX/Knotted 1 Homeobox 1 (Prep1) proteins were also identified that seem to bind the response elements and aid in tethering of Smads to the promoter following activation (Bailey et al. 2004; Suszko, et al. 2003). In an alternate mechanism, paired-like homeodomain transcription factors 1 and 2 (PITX1 and 2) regulate SMAD 2/3/4-stimulated Fshb transcription through a conserved cis-element (Lamba, et al. 2008). It was recently established that SMAD4 and forkhead box L2 (FOXL2) are essential factors for in vivo transcription of Fshb (Fortin, et al. 2014). Other than the mostly studied SMAD -mediated activation, TAK1 signaling pathway, a member of the MAPKKK family, was recognized as a potent player in the induction of FSHβ - encoding gene transcription by activin (Safwat, et al. 2005). But, a recent study contradicted the idea by demonstrating that activin A signaling is independent of the TAK1 (MAP3K7)/p38 MAPK pathway and depends on SMAD proteins (Wang and Bernard 2012). Other factors that can stimulate activin induction include morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) (Lee, et al. 2007; Nicol, et al. 2008; Otsuka and Shimasaki 2002), but their mechanism of action and associated signaling pathways are not clear.

Inhibin and follistatin are two potent antagonists of activin, regulating its inductive effects via two distinct inhibitory loops. Inhibin is a heterodimer that consists of one subunit identical to activin and another unique alpha subunit (Nakamura, et al. 1998). The production of inhibin from ovarian granulosa cells is stimulated by FSH, which in turn downregulates FSH production. The proposed mechanism of inhibin actions includes competitive inhibition at activin receptors or interaction at inhibin-specific binding sites that alters active activin binding process (Gregory and Kaiser 2004; Robertson, et al. 2004). On the other hand, follistatin, a glycoprotein having nearly ubiquitous expression in various tissues, inhibits activin actions by directly binding to it (Shimasaki, et al. 1988). Taken together, functions of activin, inhibin and follistatin forms a complex regulatory loop that tightly controls FSH production at the level of transcription. A considerable inter-species variation of FSH regulation at the level of transcription was observed as evidenced by the identification of different TATA box and other regulatory elements across species by in silico analysis (Kutteyil, et al. 2017).

Regulation of FSHβ-encoding gene expression by steroid hormones

The expression of FSHβ-encoding gene is under feedback regulation by estrogen and progesterone, both acting at the level of hypothalamus and anterior pituitary. But in rodents, estrogen does not directly modulate Fshb gene expression and seems to have only a partial effect in FSH negative feedback, as post- ovariectomy estrogen treatment does not show total suppression (Shupnik, et al. 1988). It was also reported that the expression of Fshb mRNA was not altered in overiectomized rats (Dalkin, et al. 1993; Shupnik, et al. 1989) or in rat pituitary tissue (Shupnik and Fallest 1994). An in vitro study with murine Fshb promoter also supported these results showing that Fshb expression was not stimulated by estrogen (Thackray, et al. 2006). Hence, it could be postulated that estrogen indirectly modulates expression of the FSHβ-encoding gene by regulating the actions of GnRH, activin or other effectors. It was, in fact, reported that estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) knockout mouse had higher expression of activin B in pituitary (Couse, et al. 2003).

Progesterone (P4), unlike estrogen, imparts both positive and negative feedback on FSHβ-encoding gene expression. It acts indirectly at the level of hypothalamus by regulating GnRH production and directly in the anterior pituitary (Levine, et al. 2001). Many studies have hypothesized that FSHβ-encoding gene expression in the anterior pituitary is induced by progestins (reviewed in detail in (Burger, et al. 2004). Fshb mRNA expression and secretion was blocked by P4 antagonists during pre-ovulatory (Ringstrom, et al. 1997) and secondary FSH surge (Knox and Schwartz 1992) in rats. Murine Fshb promoter was also observed to be induced by P4 in vitro (Thackray et al. 2006). A region of the DNA from −500 and −95 of the proximal promoter, which was previously shown to consist of six response elements in both ovine and mouse genes, was identified to be responsible for progesterone responsiveness, thus explaining the direct involvement of P4 in Fshb gene expression.

Androgens can also directly upregulate FSHβ-encoding mRNA levels in the pituitary. Various studies have reported that testosterone administration on GnRH antagonist treated rodents showed increased Fshb mRNA production (Burger et al. 2004; Paul, et al. 1990; Wierman and Wang 1990). In vitro studies have established that only gonadotrope cells are enough for the induction of FSHβ-encoding mRNA expression, suggesting that the androgen effect takes place uniquely at the pituitary, and the androgen driven activation of ovine and murine Fshb promoters involved the direct binding of androgen receptors to specific hormone response elements (Spady, et al. 2004; Thackray et al. 2006). But, unlike the previous reports, testosterone regulated Fshb transcription is mediated through the activin signaling pathway in both rat model and cell line studies (Burger, et al. 2007).

Other than estrogen, progesterone and androgen, glucocorticoids are also known to regulate FSHβ production in the anterior pituitary. Fshb expression was shown to selectively increase upon glucocorticoid administration in both rats and primary pituitary cultures (Kilen, et al. 1996; Leal, et al. 2003; McAndrews, et al. 1994; Ringstrom, et al. 1991). A summary of major players in transcriptional regulation of FSH subunits is shown in Fig. 1.

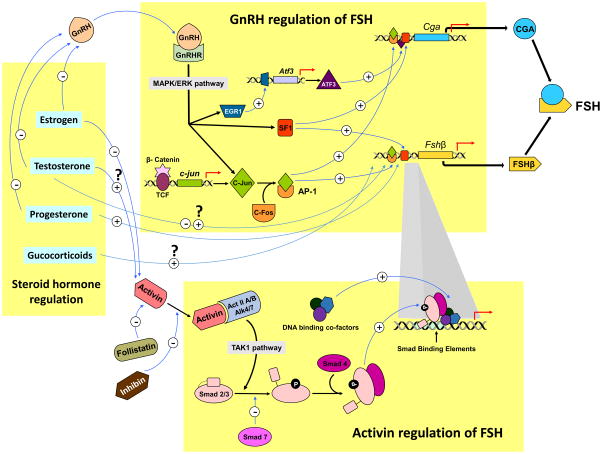

Fig. 1. Transcriptional regulation of FSH subunit - encoding genes.

The three major players that regulate FSH subunit gene transcription include GnRH, activin-inhibin-follistatin and steroids. GnRH binds to GnRH receptors expressed on gonadotropes. MAPK/ERK phosphorylation is one of the major downstream pathways activated by GnRH. These signals are further transmitted by translocation and recruitment of key transcription factors EGR1, ATF3, SF-1 and MAPK pathway -catenin-dependent activation of c-Jun-c-Fos and AP-1 onto α-GSU and FSHβ -encoding gene promoters. Estrogen, progesterone and testosterone can indirectly regulate FSH subunit encoding gene transcription by suppressing GnRH. Testosterone and glucocorticoids can also directly regulate FSHβ subunit - encoding gene transcription. Estrogen and testosterone can also regulate activin regulation of FSHβ subunit - encoding gene transcription. Activins bind to activin receptor type II and phsophorylate ALK4/7 type 1 receptors. This heterotrimeric complex via a TAK1 pathway, phosphorylates receptor-specific SMAD 2/3 transducers which complex with the phosphorylated common SMAD4 and bind to SMAD binding elements on FSHβ - encoding gene promoter. SMAD7 is an inhibitory SMAD that negatively regulates activin action. SMADS cooperatively bind with other co-factors including a key transcription factor, FOXL2 (not shown in the figure). Follistatin and inhibin bind activin and negatively regulate FSHβ subunit - encoding gene transcription.

Other regulators of FSHβ - encoding gene expression

Other than previously discussed major regulatory pathways, many novel mechanisms were identified to influence FSHβ - encoding gene expression in recent years. Unsaturated long-chain fatty acids were shown to suppress the transcriptional activity of the Fshb gene in rats and their effect is mediated via a −2824 to −2343 bp region upstream of the promoter sequence (Moriyama, et al. 2016). Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) is another factor that affects FSH expression via the induction of SMAD2/3 signaling through BMP type 1A receptor activation. It was suggested BMP2 action may involve similar signaling pathway as activins (Wang, et al. 2014c).

3. Post-transcriptional regulation of FSHβ - encoding gene expression

Whereas translational regulation of the FSHβ - encoding gene and its associated pathways have been extensively studied for many years, the effects of post-transcriptional regulation and its implication to the overall FSH synthesis was not clarified until recent years. Recently, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as key players in crosstalk between different gonadal signaling pathways and their activities can effectively inhibit or upregulate a process. They are now considered as important regulators of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. MiRNAs primarily act post-transcriptionally by destabilizing or degrading mRNA in the cytoplasm. They bestow tight control to the overall gene regulation in addition to maintaining mRNA cell specificity (Cui, et al. 2006; Farh, et al. 2005; Lin, et al. 2013; Sood, et al. 2006; Tsang, et al. 2007). FSH regulates the production of a wide range of miRNAs that target genes encompassing diverse signaling pathways (Yao, et al. 2009; Yao, et al. 2010), but not much is known about how miRNAs affect the expression of FSH itself. Most of the studies investigating post-transcriptional regulation of FSH were done in stable cell lines or established primary cultures. To investigate miRNA regulated production of the specific FSHβ subunit in vivo, Wang et al. developed a Dicer knockout mouse model and established that DICER-dependent miRNAs are indispensable for FSHβ production (Wang, et al. 2015).

One important control point of post-transcriptional regulation of FSHβ -encoding mRNA by miRNAs is exerted at the level of GnRH regulation as shown by a targeted pathway analysis approach in porcine pituitary cell cultures (Ye, et al. 2013). Besides identifying miRNAs that regulate GnRH induction of FSHβ - encoding gene, this study identified 3 down- and 10 up-regulated miRNAs that most likely are direct targets the 3′-UTR region of FSHβ-encoding mRNA. Recently, they demonstrated that miR-361-3p directly targets FSHβ -encoding mRNA and negatively regulates its synthesis, providing further functional evidence that miRNA -mediated post-transcriptional modifications are involved in FSH production (Ye, et al. 2017).

Another study identified that miR-132/212 are required for GnRH stimulated expression of FSHβ-encoding mRNA and this induction involves the SIRT1-FOXO1 pathway. MiR-132/212 are also directly involved in post-transcriptional decrease of the sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) deacetylase (Lannes, et al. 2015). Together, a regulatory loop which maintains high levels of miR-125b and low levels of miR-132 desensitizes the gonadotrope cells to GnRH stimuli, thereby disrupting the overall GnRH induction pathway (Lannes, et al. 2016). Although the importance of post-transcriptional regulation of FSH synthesis by miRNAs has been realized, the mechanisms that control the process needs further investigation.

In terms of FSH action, a genome-wide study investigating miRNA signatures in human granulosa cells demonstrated that miRNA mediated post-transcriptional regulation might play a significant role in gonadotropin signaling, and found a novel miRNA that had an intronic origin from the FSH receptor gene (Velthut-Meikas, et al. 2013).

4. Post-translational regulation of FSH

Enzymatic and covalent modifications of the hormone-specific FSHβ subunit polypeptide after its translation is a critical step in the assembly, synthesis and release of the biologically active FSH. The specific structural attributes and their molecular characteristics due to such modifications have been extensively investigated and reviewed (Butnev, et al. 2015; Combarnous 1992; Sood et al. 2006; Stanton, et al. 1996; Stockell Hartree and Renwick 1992). The major post-translational modifications of FSHβ subunit resulting in the formation of different isoforms are N-glycosylation and sialylation, while the contribution of sulphation has no major biological effect on FSH secretion and or function (Bousfield and Dias 2011).

Regulation of FSHβ N-glycosylation

The process of N-glycosylation is mediated by a multi-subunit oligosaccharyl transferase (OST) enzyme complex. The OST complex transfers a previously formed oligosaccharide from a dolichol pyrophosphate molecule to the newly formed FSHβ chain in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi compartments (Baenziger and Green 1988; Butnev, et al. 1996). N-acetyl-D-glucosamine precursors are co-translationally added to the conserved Asn24 and/or Asn7 residues and are consequently converted to complex glycans by branching through addition of various sugar units. There could be one, two or no N-glycans attached onto FSHβ, resulting in the formation of hypo-glycosylated (FSH21/18, missing one glycan chain on an Asn residue) or fully glycosylated (FSH24, having branched glycans on both Asn residues) or de-glycosylated (FSH15, having no glycans on both Asn residues) FSH isoforms. Earlier studies have investigated the alterations in FSH biological activity due to differential glycosylation mainly through in vitro bioassays and radioimmunoassays. It was suggested that different glycosylation variants have the ability to induce changes in receptor stability or conformation. Thus, activation or inhibition of a specific signal transduction pathway in target tissues, could be a FSH glycosylation- dependent feature in FSH signaling (Zambrano, et al. 1999). But the overall conformational integrity of the glycans are not essential for effective receptor-binding but the rate of activity is altered following deglycosylation (Manjunath, et al. 1982).

The state of FSH glycosylation is affected by various physiological conditions. The process of FSH glycosylation and glycan composition changes dynamically throughout the normal menstrual cycle (Wide and Eriksson 2013). Galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT), an enzyme known to modulate production of different FSH glycoforms and its biological activity, was observed to have higher expression during the proestrous and estrous phases in rats (Daude, et al. 1996), indicating a distinct role of estrous cycle in determining the formation of glycosylated species.

Calvo et al. indicated that deglycosylated forms might be less biologically active than their native fully glycosylated forms in granulosa cells (Calvo, et al. 1986). Contrary to this finding, Bousfield et al. showed that hypo-glycosylated FSH (hFSH21/18) was up to 26 times more active than the fully-glycosylated hFSH (hFSH24). The enhanced activity of hFSH21/18 was suggested as a result of availability of more binding sites for hFSH21/18 than that for hFSH24 in the FSH receptor (Bousfield, et al. 2014). Further support came from an in vitro study which confirmed that hFSH21/18 was more effective in inducing cAMP production, CREB phosphorylation, and PKA activity (Jiang, et al. 2015). The first in vivo study by Wang et al. investigated bioactivities of the different FSH glycoforms, using Fshb null mice in a pharmacological rescue approach (Wang, et al. 2016a). This study identified that recombinant hFSH21/18 and hFSH24 glycoforms have identical bioactivities when injected into immature Fshb null mice (Wang et al. 2016a). They also showed that N-glycosylation of FSHβ is needed for its assembly with the α-subunit to form the functional FSH heterodimer in mouse pituitaries, and the FSHβ glycans are determinants of FSH secretion and biological activity in vivo (Wang, et al. 2016b). Previous in vitro studies have also shown that N-linked glycan structures on FSH affect gene expression, thus regulating production of growth factors, proteins and hormones that are required for ovarian granulosa cell functions (Loreti, et al. 2013).

The differential glycosylation of hFSHβ was proposed to be due to selective inhibition of the oligosaccharyl transferase enzyme activity (Bousfield, et al. 2007; Walton, et al. 2001). But how the selective glycosylation of FSHβ subunit is controlled by OST activity, while the α -subunit undergoes full glycosylation in the same cellular compartment is yet to be understood. It may be that different OST isoforms may be involved in the process. OST isoforms in mammals differ in the characteristics of their catalytic subunit (Kelleher, et al. 2003), and it is observed that OST containing the STT3A subunit is involved in the co-translational process of N-glycosylation, while the STT3B subunit is associated with the post-translational modifications (Ruiz-Canada, et al. 2009).

After the highly-conserved N-glycosylation in the ER, the folded proteins are translocated to Golgi where diversity of the glycan forms are generated, and the process of glycan branching is a crucial contributor of this diversity. Glycan branching is mediated by a family of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferases. A single gene encodes GlcNAc transferases I, II, and III in human and mouse, while the two isoforms of both GlcNAc transferases IV and V are encoded by separate genes (Bousfield and Dias 2011). Loss of GlcNAc transferase activity was found to be either embryonic lethal (Ioffe and Stanley 1994) or contributes to various reproductive disorders in mice (Wang, et al. 2001; Williams and Stanley 2009). The high molecular weight tri- and tetra-antennary glycans are synthesized mainly by GlcNAc transferases IV and V.

Regulation of FSHβ sialylation

FSHβ sialylation involves post-translational modification resulting in the addition of sialic acid units to the end of its oligosaccharide chain. FSH contains predominantly sialylated oligosaccharides, unlike LH which has more sulfated oligosaccharides. It was speculated that FSH bound sialic acid residues may aid in targeted translocation to separate secretory granules, thereby providing a regulatory mechanism distinct from other gonadotropins (Baenziger and Green 1988). In vitro bioassay analysis had previously indicated important role of sialic acid in biological activities of equine FSH (Aggarwal and Papkoff 1981). Since number of sialic acid contributes to the overall acidic nature of the FSHβ subunit, sialylation is thought to be responsible for the regulation of the rate of molecular interactions that requires charge specificity. The less acidic or sialylated FSH isoforms may contribute to different or unique hormonal effects at the target cell level (Timossi, et al. 2000). Less sialylated FSH induced increased cAMP release, tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) enzyme activity, estrogen production, along with upregulating cytochrome P450 aromatase and tPA mRNA expression (Barrios-De-Tomasi, et al. 2002). On the other hand, more sialylated glycoforms stimulated an increased expression of alpha-inhibin subunit mRNA, indicating a possible post-translationally controlled feedback inhibitory mechanism mediated by the extent of FSH charge variation. More acidic mixtures of FSH isoforms, which have slower clearance rate than a less acidic mixture, was shown to facilitate follicular maturation in the ovary and stimulate estrogen production in sheep (West, et al. 2002).

Other than enzyme mediated post-translational modification of FSH glycans, GnRH and gonadal steroids can also affect synthesis and release of different FSH isoforms. GnRH is known to induce glycosylation, whereas estradiol aids in the GnRH-induced glycosylation process, suggesting an indirect GnRH driven FSH regulation at the post-translational level. Synthesis of FSH isoforms with differentially linked sialic acids is hormonally regulated in male rats (Ambao, et al. 2009). In addition, testosterone also increases sialylation (Wilson, et al. 1990). Progesterone is known to influence pituitary glycosylation, consequently altering the relative proportions of FSH isoforms in cattle (Perera-Marin, et al. 2008).

After ovarian failure that normally occurs as a function of aging, more acidic FSH becomes dominant and significantly detectable in older premenopausal women (Thomas, et al. 2009). A change in FSH isoform abundance, toward less acidic molecules was also observed in cows with ovulatory follicles compared to those with atretic follicles, and this shift in FSH isoforms is suggested to decide the capability for producing a preovulatory estradiol rise (Butler, et al. 2008). Factors like age, sex and reproductive state can also influence the formation of the type of the FSH isoforms in sheep pituitary (Moore, et al. 2000).

5. Regulation of FSH secretion

FSH is constitutively secreted from the gonadotrope cells via a complex multilayered regulatory process. Moreover, longer half-life in circulation and molecular heterogeneity makes detection of FSH secretory patterns more difficult through peripheral hormone measurements. The regulation of FSH secretion appears to be dominated by factors controlling inhibition of both its synthesis and release. This process includes three major aspects: GnRH signaling, and activin-inhibin-follistatin pathways and control by gonadal steroids (Fig. 2).

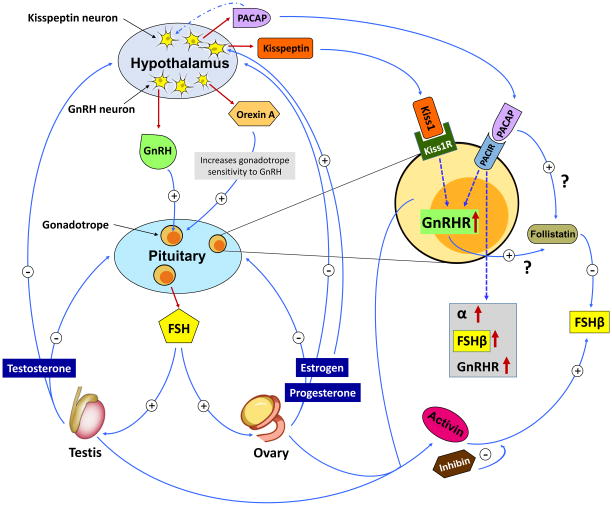

Fig. 2. Regulation of FSH secretion.

GnRH is secreted in pulses form the hypothalamus. Its secretion is regulated by multiple neuropeptides including PACAP and Kisspeptin. GnRH positively regulates FSH synthesis from pituitary. FSH binds to gonadal cell receptors and produce steroids, which directly or indirectly act at the level of the pituitary or hypothalamus, respectively. Both locally produced factors within gonadotropes such as activins, inhibins and follistatin and other peptides such as PACAP and Kisspeptin whose receptors are expressed by gonadotropes, regulate GnRHR-, and FSHβ subunit - encoding genes. Gonads are also an abundant source of activins and inhibins, which act like typical endocrine factors to regulate FSH secretion from pituitary. FSH is mostly constitutively secreted and its synthesis is tightly linked to it secretion.

GnRH mediated regulation of FSH secretion

Only low levels of GnRH are sufficient for the stimulation and maintenance of FSH secretion. FSH release from gonadotropes, unlike that of LH, is tightly associated with its rate of synthesis (McNeilly 1988). Various regulatory neuropeptides and hypothalamic factors are thought to be responsible for GnRH- mediated FSH secretion. Orexin A, synthesized by a small population of cells in the hypothalamus, was found to significantly inhibit GnRH-stimulated FSH release from rat pituitary cells. This neuropeptide was shown to modify GnRH sensitivity of gonadotrophic cells, and its effect may be age- and estrogen - dependent (Martynska, et al. 2014). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) is known to facilitate GnRH mediated secretion of FSH from sheep pituitary gonadotropes, but the increase in release is only seen at concentrations higher than normal physiological limit (Sawangjaroen, et al. 1997). GnRH itself does not directly regulate FSH at the level of secretion, but it regulates mostly at the level of FSH synthesis (McNeilly 1988).

Activin-inhibin-follistatin mediated regulation of FSH secretion

Ling et al. first identified activin as a FSH-releasing factor and coined the name to signify its opposing biological activity compared to inhibin (Ling et al. 1986). Inhibin has structural organization homologous to that of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Earlier investigations on activin-inhibin mediated secretion of FSH was mainly studied in rodent primary pituitary cultures. Gonadotropic secretion of activin B was suggested to provide an autocrine signal that selectively modulated FSH secretion in rat pituitary cells cultures, while FSH inhibitory actions of inhibin and follistatin was attributed to their interference with endogenous activin B or its activity (Corrigan, et al. 1991). It was also previously reported that follistatin suppresses FSH secretion in a highly specific manner since it shows no demonstrable effect on the release of other pituitary hormones (Ying, et al. 1987). Moreover, follistatin -treated pituitary cells showed significantly less depletion of intracellular FSH content than those treated with inhibin. This suggests unlike inhibin, follistatin acts primarily by suppressing FSH secretion. The mode of follistation action consists of binding and neutralization of both activin A and B forms (Schneyer, et al. 2003), and this specific binding to activin is decisive in determining follistatin’s differential biological activity (Sidis, et al. 2002). It was later demonstrated that inhibin immunization with anti-inhibin serum in diestrous rats also significantly increased FSH secretion in vivo (Gordon, et al. 2010).

Regulation of FSH secretion by gonadal steroids

Mechanisms of gonadal steroid hormone regulated FSH secretion are mostly interweaved with both GnRH- mediated and activin-inhibin regulated pathways, indicating the complexity and selective interdependency of these processes. In rodents, estrous cycle plays an important role in dictating this steroid hormone regulated FSH secretion. It was noted that anti-progestins RU486 and ZK98299 affected levels of serum FSH and FSHβ mRNA in a similar manner during proestrus, while they showed divergent patterns on estrus indicating that the active functional state of progesterone receptor/transcriptional activation complex is different during the two cyclic phases (Ringstrom et al. 1997). A study also indicated that estrogen and inhibin both differentially modulate the estrus stage - dependent increased secretion of FSH in bovine pituitary cells (Lane, et al. 2005).

It was also shown that the suppression of both basal and activin-mediated FSH secretion takes place in an estrogen dependent process (Szabo, et al. 1998). Progesterone receptors, upon induction by estradiol, respond to activin-induced signal transduction to regulate FSH release. A study in ovine pituitary cells reported that differential effects of estradiol on FSH secretion in ovine pituitary cells may be indirectly mediated by activin (Baratta, et al. 2001). An in vivo study on rats confirmed the regulation of FSH secretion by estrogen and inhibins, and identified estradiol-17 beta as the major candidate mediating the mechanism (Herath, et al. 2001). The negative estrogen feedback was associated with increased levels of both inhibin isoforms in plasma, while inhibin A seems to be the dominant species during the initiation of the process. The mechanism of estrogen suppression of FSH release in vivo was investigated in pre-pubertal mice in a recent study, which indicated that the process takes place via the activation of estrogen receptor- α in kisspeptin neurons affecting directly affecting GnRH release (Dubois, et al. 2016). Other than estrogen, progesterone, and corticosterone, testosterone is also known to stimulate the release and maintain intracellular levels of FSH by activation of the androgen receptor (directly or as dihydrotestosterone) and conversion to estradiol or activation of estrogen receptors (Hiipakka and Liao 1998; McPhaul and Young 2001). The steroid hormone actions are mediated by activin which involves a tightly regulated actvin/follistatin autocrine-paracrine loop (Bohnsack, et al. 2000).

Other factors regulating FSH secretion

Several other molecular factors, independently or in association with the above described pathways, contribute to the complex regulation of FSH secretion. One of them is corticosterone, which stimulates selectively FSH release (Kilen et al. 1996). Bone morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP-4) exerts inhibitory effects on FSH release, via the induction of Smad1 phosphorylation, and activation of the BMP signaling pathway (Faure, et al. 2005). BMP-4 blocks activin stimulation of FSH release in addition to increasing the 17β - estradiol - mediated suppression of FSH secretion. Adiponectin, a protein involved in glucose regulation and fatty acid catabolism is another factor that increases FSH release from the pituitary gonadotropes (Kiezun, et al. 2014). This establishes a new crosstalk between the glucose- fatty acid metabolic pathways and the reproductive axis.

Roper et al. recently identified synaptotagmin 9 (syt-9), a Ca2+ sensor protein associated with exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells, as a regulator of FSH secretion in vivo (Roper, et al. 2015). Interestingly, they found that syt-9 and FSH were co-localized in pituitaries of female but not male mice. Accordingly, loss of syt-9 reduced FSH secretion only in females, indicating a sex-specific regulation of FSH. A population study on human subjects reported that adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) regulates FSH release. This study identifies a novel pathway of gonadotropin secretion mediated by the adrenal cortex (Aleknaviciute, et al. 2016). Ghrelin, a neuropeptide involved in the regulation of physiological energy balance, was also found to influence FSH secretion in pre-pubertal sheep (Wojcik-Gladysz, et al. 2016). The identification of novel factors from such diverse physiological pathways indicates the complexity of FSH regulation. It further substantiates the idea that various signaling networks, related or unrelated to the direct regulation of the reproductive axis, act in parallel to maintain FSH levels.

6. Regulation of FSH action

The actions of FSH in regulating the reproductive axis have been extensively investigated through years (Howles 2000; Loraine and Schmidt-Elmendorff 1963; Sairam and Krishnamurthy 2001; Simoni, et al. 1999; Smitz, et al. 2016; Zafeiriou, et al. 2000). FSH binds and activates, a 7 transmembrane (7TMR) domain containing FSH receptor (FSHR) expressed in granulosa cells in ovaries and Sertoli cells in testes (Simoni, et al. 1997). Inactivating either Fshb or Fshr leads to consistent reproductive defects (Huhtaniemi, et al. 2006; Layman, et al. 1997; Matthews, et al. 1993) and based on its physiological target, FSH controls distinct biological responses like cell proliferation, differentiation, steroidogenesis, metabolism, and apoptosis (Dias, et al. 2010) (Fig. 3).

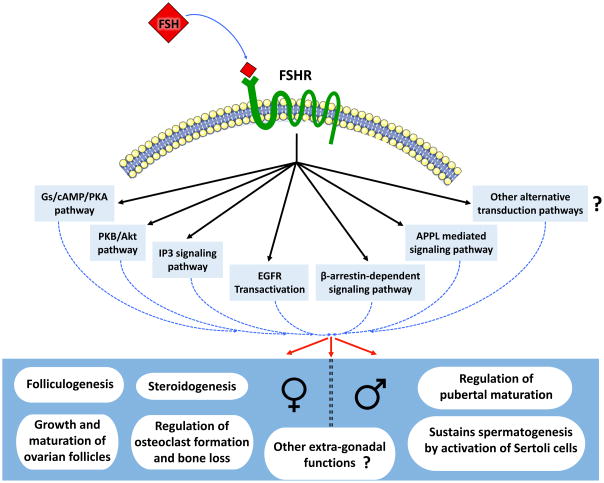

Fig. 3. A summary of different signaling mechanisms that mediate FSH actions in target cells.

FSH binds to G-protein coupled seven transmembrane - spanning FSHRs expressed on target cells. This leads to activation of a battery of signaling pathways depending on the developmental and physiological context. In the female FSH mainly acts to regulate ovarian folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis. Recently, extra-gonadal actions of FSH mediated via FSHRs, have been identified, particularly in osteoclasts in female rodent bones. These observations have implications for understanding and treating bone loss in post-menopausal women. In the male, FSHRs are expressed on Sertoli cells in the testis. FSH regulates pre-pubertal proliferation and maturation of Sertoli cells. Proper maturation of Sertoli cells is essential for maintaining optimal spermatogenesis. Other extra-gonadal functions of FSH have also been proposed but these are yet to be rigorously tested.

Regulation of FSH functions mediated by FSHR

For several decades, the canonical Gs/cAMP/PKA pathway has been considered as the major mechanism by which FSH exerts its actions within target cells (Dattatreyamurty, et al. 1987). But in recent years it has been recognized that FSH binding to its receptor also induces several other signaling pathways, adding to the growing complexity (Gloaguen, et al. 2011). Activation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) was identified as an alternative response of FSH-FSHR binding (Zeleznik, et al. 2003), which was reported to be a cAMP - dependent and PKA - independent pathway (Gonzalez-Robayna, et al. 2000; Meroni, et al. 2002). This involves an exchange protein (EPAC) directly activated by cAMP. Wayne et al. later demonstrated the significance of EPACs in mediating biological activities of FSH (Wayne, et al. 2007). A more recent study suggests that FSH-stimulated ERK activation in granulosa cells involves PKA-dependent inactivation of MAP kinase phosphatase (3MKP3) (Donaubauer, et al. 2016). FSH responsive genes are also regulated by Forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) protein in ovarian granulosa cells via the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/AKT (Herndon, et al. 2016). Insulin like growth factor-2 (IGF-2) expression is also regulated by FSH through the AKT-dependent pathway (Baumgarten, et al. 2015). Further, IGF-1 and FSH signaling pathways are shown to interact in granulosa cells both in vitro and in vivo (Stocco, et al. 2017; Zhou, et al. 2013).

FSHR can couple with other G protein subtypes. FSHR was shown to activate pertussis toxin-sensitive pathways upon binding certain hormone variants or depending upon the specific developmental stage of target cells (Arey, et al. 1997; Crepieux, et al. 2001). FSHR also activates the inositol trisphosphate (IP3) signaling pathway (Quintana, et al. 1994) and interacts directly with Gαq subunit in granulosa cells (Escamilla-Hernandez, et al. 2008). In an alternate signaling mechanism observed in Sertoli cells, the FSH-induced IP3 response was explained via functional coupling of FSHR and tissue transglutaminase (Gαh), which results in PLCδ activation and IP3 accumulation (Lin, et al. 2006).

Other than the well- known heterotrimeric G proteins, G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) and β-arrestins are two other classes of proteins shown to interact specifically with FSHRs upon FSH induction. GRKs and β-arrestins regulate FSHR stimulation by controlling selective sensitization, internalization, and recycling of FSHR (Kishi, et al. 2002; Krishnamurthy, et al. 2003; Marion, et al. 2006; Marion, et al. 2002; Nakamura et al. 1998; Piketty, et al. 2006; Reiter, et al. 2001; Troispoux, et al. 1999). But over last few years, the spectrum of functions performed by β-arrestins has expanded. They also act as signal transducers in a G protein-independent manner at different 7TMRs (Lefkowitz and Shenoy 2005; Reiter and Lefkowitz 2006). Although only FSHR mediated β-arrestin-dependent and G protein-independent activation of ERK and rpS6 has so far been identified as the effector mechanism, it could be predicted that β -arrestins are associated with the G protein-independent activation of a wide array of differential signaling pathways downstream of the FSHR.

β-arrestins are known to function as multifunctional scaffolds interacting with several proteins, thereby facilitating the phosphorylation of numerous intracellular targets at other transmembrane receptors (Whalen, et al. 2011; Xiao, et al. 2007). The adaptor protein phosphotyrosine interacting with PH domain and leucine zipper 1 (APPL1) was reported to directly bind FSHR, consequently triggering downstream signaling cascades. APPL1 was originally suggested to interact with the first intracellular FSHR loop and APPL1 induces FSH-dependent PI3K signaling (Nechamen, et al. 2004). A recent study showed that FSH stimulated activation of the inositol–phosphate calcium pathway requires APPL1 - FSHR interaction (Thomas, et al. 2011). PI3K pathway is also induced by the members of the Src family of kinases in granulosa cells (Wayne et al. 2007). FSH-induced activation of ERK pathway is mediated by Src proteins in granulosa and Sertoli cells (Cottom, et al. 2003; Crepieux et al. 2001). FSH also induced epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) autophosphorylation in granulosa cells via Src activation (Cottom et al. 2003; Wayne et al. 2007). This suggests an important role of EGFR transactivation in relaying the FSH signals in the target cells. In addition, EGRF inhibition reduced the ability of FSH to stimulate CDK4 activation and ERK /Akt phosphorylation in different model systems (Andric and Ascoli 2006; Cottom et al. 2003; Shimada, et al. 2006; Wayne et al. 2007; Yang and Roy 2006). FSH also regulates the initiation of germ cell mitosis/meiosis in embryonic chicken through the involvement of progesterone and upregulation of miR181a. This miRNA inhibits meiotic initiation by suppressing the Nuclear Receptor subfamily 6 Group A member 1 (NR6A1) transcript (He, et al. 2013).

Mouse models for studying FSH actions in vivo

The development of transgenic mouse models contributed to major advancements in the field of reproduction research. Several mouse models were generated that largely facilitated our understanding of how FSH acts in normal reproductive physiology and under pathological conditions. The models belong to two categories. In the gain-of-function, reporter gene (e.g., transgenes encoding subunits of a protein or CRE recombinase enzyme) expression is driven by specific promoter sequences. In the loss-of-function model (knockout, KO), mutations at a target locus are first produced in embryonic stem cell (ES) followed by propagation of the resulting mutant allele through germline (Kumar, et al. 2009). Multiple KO mutations could be combined and an intercross of KO model with a gain-of-function model results in a genetic rescue model. Cell- or tissue-specific deletion of a gene is of interest, since such a technology allows us to investigate molecular mechanisms in a tissue of interest selectively, when global null mutations result in undesired or even lethal phenotypes. LoxP- flanked genes of interest combined with CRE-expressing transgenic lines as drivers are used to achieve such tissue-, cell –specific deletions (Bouabe and Okkenhaug 2013; Deng 2014; Schmidt-Supprian and Rajewsky 2007).

A transgenic mouse model overexpressing the human CGA gene was generated, which did not show any major reproductive abnormalities (Fox and Solter 1988). Kumar et al. developed the first transgenic mouse model for FSH. They demonstrated gonadotroph-specific expression of a 10 kb human FSHB transgene in mouse pituitaries (Kumar, et al. 1992). Overexpression of the human FSHβ subunit did not result in any overt phenotypes in female transgenic mice. Transgenic males, however showed a marginal increase in testis weight without any major male reproductive consequences (Kumar et al. 1992). This mouse model was further used to demonstrate differences in steroid hormone regulation between mouse Fshb and human FSHB gene expression (Kumar and Low 1993, 1995) and GnRH regulation (Kumar and Low 1995). This model also served as a genetic platform to further identify and narrow down regulatory elements controlling human FSHB expression in vivo (Kumar, et al. 2006).

A bi-transgenic human FSH expressing model was developed by a genetic intercross between two independent transgenic lines. One line expressed a human CGA mini-gene and another the FSHB gene. Both the transgenes were expressed from a mouse metallothionein-1 promoter. This ectopic expression of human FSH dimer was achieved at low and very high levels (Kumar, et al. 1999). The low level human FSH expressing mice developed normally, do not display any abnormalities and are fertile. The very high level human FSH - expressing male mice were infertile, displayed hyperandrogenemia and consequently enlarged seminal vesicles but spermatogenesis looked qualitatively normal in testes of these mice (Kumar et al. 1999). The transgenic female mice expressing very high levels of human FSH were infertile, their ovarian histology was normal initially up to 2 weeks, and several abnormalities were noticed by 3 weeks and beyond. In transgenic mice at 6 weeks of age, the ovaries contained many hemorrhagic follicles with totally disrupted folliculogenesis. At this age, serum levels of estrogen, progesterone, testosterone and acitvins were elevated. Very few (~ 5 %) transgenic female mice survived and died by 13 weeks of age presumably secondary to urinary bladder and kidney defects (Kumar et al. 1999). Thus, female mice ectopically expressing high levels of human FSH demonstrate at least some features of polycystic ovarian syndrome in women.

Allan et al. developed another ectopic human FSH dimer expressing line of mice, in which the human FSH subunit encoding cDNA transgenes were engineered in tandem and targeted to liver using a rat insulin II promoter (Allan, et al. 2001). These transgenic mice were later intercrossed with hpg mice and maintained on the hpg genetic background (hpg; hFSH+). Because of a naturally occurring mutation in the Gnrh gene, hpg mice do no produce GnRH and hence gonadotropins and ovarian steroids and are infertile (Allan et al. 2001). Thus, this genetic approach allowed the investigators to test the effects of ectopically expressed human FSH in the absence of LH and gonadal steroids. Male transgenic mice on hpg background, with human FSH at levels > 1 IU/L showed partial rescue of the testis and spermatogenesis phenotypes. Testis size increased and histological analysis revealed that spermatogenesis progressed until early post-meiosis (Allan et al. 2001; Haywood, et al. 2003), similar to the phenotypes observed in Lhb null mice (Ma, et al. 2004). When supplemented with testosterone, spermatogenesis was fully restored in these hpg; hFSH+ mice. Female hpg; hFSH+ mice also showed rescue; the ovarian follicle reserve increased and ovarian histology demonstrated many antral follicles and serum inhibin levels elevated. Surprisingly, hFSH+ transgenic mice alone (not on hpg background) by ~ 6 months of age showed accelerated aging leading to premature ovarian failure (Allan et al. 2001).

Because hpg mice lack both FSH and LH as a result of loss of functional GnRH, to study the in vivo roles of exclusively FSH, a loss of function mouse model for FSH action was generated using embryonic stem cell technology (Kumar et al. 1997). Fshb null mice developed normally and demonstrated reproductive phenotypes. Fshb null males were fertile despite displaying reduced testis size as a result of reduced Sertoli cell and germ cell carrying capacity (Wreford, et al. 2001), reduced sperm number and motility (Kumar et al. 1997). Fshb null females displayed hypoplastic ovaries and uterine horns. Ovarian histology showed a pre-antral stage block in folliculogenesis and no evidence of corpora lutea indicating that these null mice were anovulatory (Kumar et al. 1997). However, in a superovulation protocol, when injected with exogenous hormones, these null female mice responded and released comparable number of oocytes similar to control mice (Kumar et al. 1997). Thus, FSH responsiveness is retained in these null female mice in the absence of FSH ligand from birth. Subsequent studies with Fshb null females showed that FSH regulates transzonal projection mediated communication between granulosa cells and oocytes (Combelles, et al. 2004), gap junction proteins between granulosa cells (Clarke 2018; El-Hayek and Clarke 2015) and epidermal growth factor receptor expression in granulosa cells to prime the follicles for ovulation prior to LH action (El-Hayek, et al. 2014).

Knockout mice lacking Fshr gene display defects in reproductive function in both male and female mice, similar to those seen in mice lacking FSH (Abel, et al. 2000; Dierich, et al. 1998; Kumar et al. 1997). Fshb genetic rescue, activin, inhibin, and follistatin knockouts, FSH glycosylation mutants, FSH re-routed transgenic models were used in various studies to investigate the entire spectrum of FSH actions in vivo (Abel, et al. 2014; Guo, et al. 1998; Jorgez, et al. 2004; Kumar, et al. 1998; Matzuk, et al. 1992; Matzuk, et al. 1995; Sandoval-Guzman, et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014c). Recently, these models were reviewed in detail (Kumar 2016) and summarized in the Table. Inactivating mutations in human FSHB and FSHR are although rare, they have been reported (Huhtaniemi and Themmen 2005; Narayan et al. 2018). While mouse models lacking Fshb are somewhat discordant, those lacking Fshr mostly phenocopy human mutations in the corresponding gene (Kumar 2016).

Table.

Mouse models for FSH synthesis, secretion and action

| Model | Phenotypes | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Cga transgenic | Cell-specific expression and regulation of the human alpha-subunit transgene in the pituitary. No detectable expression in placenta. | (Fox and Solter 1988) |

| Cga knockout | A loss-of-function mutation. Hypogonadism and hypothyroidism. | (Kendall, et al. 1995) |

| Human FSHB transgenic | Human FSHβ-overexpression in pituitary gonadotropes. Increased testis weight in males. No overt phenotypes in females. | (Kumar et al. 1992) |

| MT- CGA/MT-FSHB bi-transgenic | Multiple reproductive defects including hemorrhagic and cystic ovaries in females. Males infertile with enlarged seminal vesicles and elevated serum testosterone. | (Kumar et al. 1999) |

| Fshb knockout | Males fertile with decreased testis size. Females infertile with a per-antral stage block in folliculogenesis. Increased bone density. | (Kumar et al. 1997) |

| Fshb genetic rescue | Testis size, sperm number, and motility defects in Fshb null males rescued. Folliculogenesis resumed normally in females. | (Kumar et al. 1998) |

| FSHB re-routed transgenic | Fshb-null mice rescued by rerouted FSH. Enhanced ovarian follicle survival, increase in ovulation number, and prolonged reproductive lifespan in females. | (Wang, et al. 2014a) |

| FSHB glycosylation mutant transgenic rescue | The double N-glycosylation mutant (Asn7Δ Asn24Δ) transgene fails to rescue Fshb null mice. | (Wang et al. 2016a) |

| Human FSH / hpg transgenic rescue | Males showed increased testis weight up to 5-fold. Females exhibited enlarged ovaries and a strong FSH dose-dependent increase in serum inhibin B levels. | (Allan et al. 2001) |

| Fshr knockout | Phenocopy Fshb null mice. Males fertile but with reduced testes size. Females infertile. | (Abel et al. 2000; Dierich et al. 1998) |

| Activating Fshr transgenic (D580H) | Hemorrhagic cysts, accelerated loss of small follicles, increased gonadotropins, prolactin and elevated estrogen. | (Peltoketo, et al. 2010) |

| Inha knockout | Development of gonadal stromal tumours, elevated levels of serum FSH, activins and estradiol. | (Matzuk et al. 1992) |

| Inha / Fshb double knockout | Slow-growing and less hemorrhagic testicular tumors in males and ovarian tumors in females, and with minimal cachexia. | (Kumar et al. 1999) |

| Acvr2a knockout | Suppressed FSH production and defects in reproductive performance. Males sub - or infertile and exhibit male sexual behavior defects; females with parturition defects. | (Ma, et al. 2005; Matzuk et al. 1995) |

| MT- Follistatin Transgenic | Multiple reproductive defects. Marginally elevated FSH in on line with widespread expression of the FS transgene. | (Guo et al. 1998) |

| Smad3 /Smad4 gonadotroph-specific knockout | Phenocopy of Fshb null mice. | (Li, et al. 2017) |

| Foxl2 knockout | Impaired FSH synthesis and secretion, ovarian function. | (Justice, et al. 2011; Schmidt, et al. 2004; Uda, et al. 2004) |

| Foxl2 gonadotrope-specific knockout | Impaired FSH synthesis and fertility. | (Tran, et al. 2013) |

| Smad4 / Foxl2 double knockout | Phenocopy of Fshb null mice. | (Fortin et al. 2014) |

Extra-gonadal actions of FSH

The central dogma of classical FSH actions in gonads has been challenged in the past decade by studies that demonstrated a direct involvement of FSH in bone physiology (Sun, et al. 2006). FSH levels increase sharply in contrast to declining estrogen levels as observed in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. A direct effect of FSH on the skeletal system was discovered using Fshb and Fshr null mice which have increased bone density (Sun et al. 2006). Gi2α-coupled FSH receptors were identified in osteoclasts and their precursors. An increase in osteoclast formation and function was demonstrated by an FSH- FSHR dependent activation of MEK/Erk, Akt and NF-κB pathways, suggesting a positive correlation of circulating FSH with hypogonadal bone loss (Sun et al. 2006). FSH was also shown to regulate FSHR- induced alveolar bone loss in rats by an estrogen independent process (Liu, et al. 2010). The mechanism of FSH induced increase alveolar bone loss was addressed in a recent study which showed that the FSH effect was mediated by upregulation of the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) protein and the process involves Akt, Erk, and p38 signaling pathways (Zhu, et al. 2016a). A new concept advocated that a reciprocal cross signaling operates between FSHR signaling by FSH and bone morphogenetic protein-9 (BMP-9) induced activation of BMP/Smad signaling in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. This study identified the cross signaling between FSH and BMP-9 promoted osteogenic differentiation (Su, et al. 2017). Controversy exists with regard to FSH actions on bone (Kumar 2018) as data obtained using both mice and humans, contradict the original observations made by Sun et al. (Sun et al. 2006).

In addition to its previously discussed functions in skeletal system, FSH was reported to act on the endothelial cells of human umbilical cord and monocytes (Cannon, et al. 2011; Robinson, et al. 2010; Stilley, et al. 2014b). FSH receptors have been identified in female reproductive tract and the developing placenta, and the functional relevance on this finding was confirmed by the observation that Fshr knockout mice exhibit feto-placental defects (Stilley, et al. 2014a). Low levels of Fshb expression was also detected in various non-ovarian tissues, maternal uterine decidua, placenta and uterine myometrium in pregnant women. Tumor blood vessels were also shown to express FSHRs (Radu, et al. 2010) and FSH action has been implicated in endometriosis (Ponikwicka-Tyszko, et al. 2016). Data are also available on FSH action on prostate tumors (Ide, et al. 2013; Siraj, et al. 2013; Zhu, et al. 2016b). Finally, a blocking antibody against FSH shown to be efficacious in reducing white fat accumulation and conversion to brown fat accompanied by mitochondrial biogenesis in ovariectomised mice (Liu, et al. 2017). The biochemical identity and the key downstream components of extragonadal FSH

receptors are not clear. At least in mouse bone osteoclasts and adipocytes, FSH signaling pathways appear to be different and involve non-cAMP mediated effects (Liu et al. 2017; Sun et al. 2006). The physiological relevance of FSH actions in at least some extragonadal tissues was challenged recently (Stelmaszewska, et al. 2016), yet to be rigorously tested and may require development of novel genetic models (Kumar 2018).

Conclusion

Over the past several decades, studies on FSH have identified the molecular mechanisms for its overall regulation. Starting from signals mediating the initial synthesis to those needed for exerting successful biological actions, every step of FSH regulation is under tight control. Thus, the regulation FSH is highly complex and multilayered. Crosstalk between various signaling pathways modulate specific steps and further adds up to the complexity. As discussed in this review, novel findings related to the transcriptional, translational, post-translational and functional regulatory mechanisms validate that FSH plays a more comprehensive role in controlling various physiological functions than just being classified as a reproductive effector.

Appreciation of diverse functions of FSH and their regulation would be instrumental in developing effective therapies related to both reproductive disorders and other pathological conditions known to be directly or indirectly affected by FSH. For example, with the new understanding that FSH may be a key player in age-related bone loss, effective estrogen and related therapies for bone loss treatment could be implemented. One concept is to develop novel antagonists for both FSH and its receptor. Our knowledge of novel FSH functions in extra-gonadal is currently limited. More comprehensive investigations are needed to decipher the underlying molecular mechanisms that interweave FSH regulation across different physiological systems. A deeper understanding of such mechanisms of the overall FSH regulation will facilitate the development novel hormonal therapies in the coming decade.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research in the Kumar laboratory is supported in part by the NIH grants CA166557, AG029531, AG056046, HD081162 and The Makowski Endowment Funds.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as hindering the impartiality of this review.

References

- Abel MH, Widen A, Wang X, Huhtaniemi I, Pakarinen P, Kumar TR, Christian HC. Pituitary gonadotrophic hormone synthesis, secretion, subunit gene expression and cell structure in normal and follicle-stimulating hormone beta knockout, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor knockout, luteinising hormone receptor knockout, hypogonadal and ovariectomised female mice. J Neuroendocrinol. 2014;26:785–795. doi: 10.1111/jne.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel MH, Wootton AN, Wilkins V, Huhtaniemi I, Knight PG, Charlton HM. The effect of a null mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene on mouse reproduction. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1795–1803. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.5.7456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB, Papkoff H. Relationship of sialic acid residues to in vitro biological and immunological activities of equine gonadotropins. Biol Reprod. 1981;24:1082–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleknaviciute J, Tulen JH, Timmermans M, de Rijke YB, van Rossum EF, de Jong FH, Kushner SA. Adrenocorticotropic hormone elicits gonadotropin secretion in premenopausal women. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2360–2368. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan CM, Haywood M, Swaraj S, Spaliviero J, Koch A, Jimenez M, Poutanen M, Levallet J, Huhtaniemi I, Illingworth P, et al. A novel transgenic model to characterize the specific effects of follicle-stimulating hormone on gonadal physiology in the absence of luteinizing hormone actions. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2213–2220. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambao V, Rulli SB, Carino MH, Console G, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Calandra RS, Campo S. Hormonal regulation of pituitary FSH sialylation in male rats. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;309:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andric N, Ascoli M. A delayed gonadotropin-dependent and growth factor-mediated activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 cascade negatively regulates aromatase expression in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3308–3320. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arey BJ, Stevis PE, Deecher DC, Shen ES, Frail DE, Negro-Vilar A, Lopez FJ. Induction of promiscuous G protein coupling of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor: a novel mechanism for transducing pleiotropic actions of FSH isoforms. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:517–526. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.5.9928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attisano L, Wrana JL. Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baenziger JU, Green ED. Pituitary glycoprotein hormone oligosaccharides: structure, synthesis and function of the asparagine-linked oligosaccharides on lutropin, follitropin and thyrotropin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;947:287–306. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(88)90012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JS, Rave-Harel N, McGillivray SM, Coss D, Mellon PL. Activin regulation of the follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit gene involves Smads and the TALE homeodomain proteins Pbx1 and Prep1. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1158–1170. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baratta M, West LA, Turzillo AM, Nett TM. Activin modulates differential effects of estradiol on synthesis and secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone in ovine pituitary cells. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:714–719. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.2.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios-De-Tomasi J, Timossi C, Merchant H, Quintanar A, Avalos JM, Andersen CY, Ulloa-Aguirre A. Assessment of the in vitro and in vivo biological activities of the human follicle-stimulating isohormones. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;186:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten SC, Convissar SM, Zamah AM, Fierro MA, Winston NJ, Scoccia B, Stocco C. FSH Regulates IGF-2 Expression in Human Granulosa Cells in an AKT-Dependent Manner. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E1046–1055. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard DJ. Both SMAD2 and SMAD3 mediate activin-stimulated expression of the follicle-stimulating hormone beta subunit in mouse gonadotrope cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:606–623. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard DJ, Tran S. Mechanisms of activin-stimulated FSH synthesis: the story of a pig and a FOX. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:78. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.107797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder AK, Grammer JC, Herndon MK, Stanton JD, Nilson JH. GnRH regulation of Jun and Atf3 requires calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:873–886. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerboom D, Kumar V, Boyer A, Wang Y, Lambrot R, Zhou X, Rico C, Boehm U, Paquet M, Celeste C, et al. beta-catenin stabilization in gonadotropes impairs FSH synthesis in male mice in vivo. Endocrinology. 2015;156:323–333. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack BL, Szabo M, Kilen SM, Tam DH, Schwartz NB. Follistatin suppresses steroid-enhanced follicle-stimulating hormone release in vitro in rats. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:636–641. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.3.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokar JA, Keri RA, Farmerie TA, Fenstermaker RA, Andersen B, Hamernik DL, Yun J, Wagner T, Nilson JH. Expression of the glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit gene in the placenta requires a functional cyclic AMP response element, whereas a different cis-acting element mediates pituitary-specific expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5113–5122. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfil D, Chuderland D, Kraus S, Shahbazian D, Friedberg I, Seger R, Naor Z. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, Jun N-terminal kinase, p38, and c-Src are involved in gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated activity of the glycoprotein hormone follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit promoter. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2228–2244. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouabe H, Okkenhaug K. Gene targeting in mice: a review. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1064:315–336. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-601-6_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield GR, Butnev VY, Butnev VY, Hiromasa Y, Harvey DJ, May JV. Hypo-glycosylated human follicle-stimulating hormone (hFSH(21/18)) is much more active in vitro than fully-glycosylated hFSH (hFSH(24)) Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield GR, Butnev VY, Walton WJ, Nguyen VT, Huneidi J, Singh V, Kolli VS, Harvey DJ, Rance NE. All-or-none N-glycosylation in primate follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunits. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;260–262:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield GR, Dias JA. Synthesis and secretion of gonadotropins including structure-function correlates. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011;12:289–302. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield GR, Jia L, Ward DN. Gonadotropins: chemistry and biosynthesis. In: Neill JD, editor. Knobil’s Physiology of Reproduction. 3. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 1581–1634. [Google Scholar]

- Burger LL, Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Marshall JC. Regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene transcription. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33:559–584. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger LL, Haisenleder DJ, Wotton GM, Aylor KW, Dalkin AC, Marshall JC. The regulation of FSHbeta transcription by gonadal steroids: testosterone and estradiol modulation of the activin intracellular signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E277–285. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00447.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrin JM, Jameson JL. Regulation of transfected glycoprotein hormone alpha-gene expression in primary pituitary cell cultures. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1643–1651. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-10-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler ST, Pelton SH, Knight PG, Butler WR. Follicle-stimulating hormone isoforms and plasma concentrations of estradiol and inhibin A in dairy cows with ovulatory and non-ovulatory follicles during the first postpartum follicle wave. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2008;35:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butnev VY, Butnev VY, May JV, Shuai B, Tran P, White WK, Brown A, Smalter Hall A, Harvey DJ, Bousfield GR. Production, purification, and characterization of recombinant hFSH glycoforms for functional studies. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;405:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butnev VY, Gotschall RR, Baker VL, Moore WT, Bousfield GR. Negative influence of O-linked oligosaccharides of high molecular weight equine chorionic gonadotropin on its luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor-binding activities. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2530–2542. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.6.8641207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo FO, Keutmann HT, Bergert ER, Ryan RJ. Deglycosylated human follitropin: characterization and effects on adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-phosphate production in porcine granulosa cells. Biochemistry. 1986;25:3938–3943. doi: 10.1021/bi00361a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon JG, Kraj B, Sloan G. Follicle-stimulating hormone promotes RANK expression on human monocytes. Cytokine. 2011;53:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SG, Ruf-Zamojski F, Pincas H, Roysam B, Sealfon SC. Characterization of a MAPK scaffolding protein logic gate in gonadotropes. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1027–1039. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccone NA, Lacza CT, Hou MY, Gregory SJ, Kam KY, Xu S, Kaiser UB. A composite element that binds basic helix loop helix and basic leucine zipper transcription factors is important for gonadotropin-releasing hormone regulation of the follicle-stimulating hormone beta gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1908–1923. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccone NA, Xu S, Lacza CT, Carroll RS, Kaiser UB. Frequency-dependent regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone beta by pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone is mediated by functional antagonism of bZIP transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1028–1040. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00848-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke HJ. Regulation of germ cell development by intercellular signaling in the mammalian ovarian follicle. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2018:7. doi: 10.1002/wdev.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combarnous Y. Molecular basis of the specificity of binding of glycoprotein hormones to their receptors. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:670–691. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-4-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combelles CM, Carabatsos MJ, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM, Albertini DF. Hormonal control of somatic cell oocyte interactions during ovarian follicle development. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;69:347–355. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan AZ, Bilezikjian LM, Carroll RS, Bald LN, Schmelzer CH, Fendly BM, Mason AJ, Chin WW, Schwall RH, Vale W. Evidence for an autocrine role of activin B within rat anterior pituitary cultures. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1682–1684. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-3-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coss D, Hand CM, Yaphockun KK, Ely HA, Mellon PL. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is critical for synergistic induction of the FSH(beta) gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone and activin through augmentation of c-Fos induction and Smad phosphorylation. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:3071–3086. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]