Abstract

We have previously reported that the dispersion of spin lattice relaxation rates in the rotating frame (R1ρ) of tissue water protons at high field can be dominated by chemical exchange contributions. Ischemia in brain causes changes in tissue pH which in turn may affect proton exchange rates. Amide proton transfer (APT, a form of chemical exchange saturation transfer) has been shown to be sensitive to chemical exchange rates and able to detect pH changes non-invasively following ischemic stroke. However, the specificity of APT to pH changes is decreased because of the influence of several other factors that affect magnetization transfer. R1ρ is less influenced by such confounding factors and thus may be more specific for detecting variations in pH. Here, we applied a spin-locking sequence to detect ischemic stroke in animal models. Although R1ρ images acquired with a single spin-locking amplitude (ω1) have previously been used to assess stroke, here we use ΔR1ρ, which is the difference in R1ρ values acquired with two different locking fields to emphasize selectively the contribution of chemical exchange effects. Numerical simulations with different exchange rates and measurements of tissue homogenates with different pH were performed to evaluate the specificity of ΔR1ρ to detect tissue acidosis. Spin-lock and APT data were acquired on five rat brains after ischemic strokes induced via middle cerebral artery occlusions (MCAO). Correlations between these data were analyzed at different time points after the onset of stroke. The results show that ΔR1ρ, (but not R1ρ acquired with a single ω1) was significantly correlated with APT metrics consistent with ΔR1ρ varying with pH.

Keywords: Relaxometry, Chemical exchange saturation transfer, Brain ischemia and degeneration, Spin-lock

Graphical Abstract

ΔR1ρ, the difference of R1ρ acquired with low and high locking amplitudes, can emphasize selectively the contribution of chemical exchange effects, and thus provide pH-weighted imaging. Experiments on MCAO induced cerebral ischemia in rats indicate that ΔR1ρ has strong correlation with APT, but shows better image quality.

INTRODUCTION

During ischemia, anaerobic respiration leads to the production of lactate which usually causes tissue acidosis. Imaging of such tissue pH changes would be valuable for the diagnosis, staging, and monitoring of ischemic strokes. For example, pH sensitive imaging has been applied to identify the salvageable penumbra after ischemic events in the brain (1–4). Development of non-invasive and higher sensitivity pH imaging methods could significantly enhance the clinical role of MRI in stroke studies.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) has been used to assess tissue pH during stroke (5). However, due to its low spatial and temporal resolutions, its practical applicability is limited. The chemical exchange rate between solute protons and water protons also depends on physico-chemical factors such as pH and temperature. Imaging methods that produce parametric maps that are sensitive to chemical exchange could provide alternative means to assess variations in tissue pH. Previously, amide proton transfer (APT), a variation of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) from protein and peptide amides, has been shown to be sensitive to tissue pH (6) and has been applied to assess tissue acidosis following ischemic stroke. However, CEST approaches such as APT (7) and amine-water exchange effects (8,9) are not specific solely for chemical exchange but are inherently sensitive to changes in water relaxation time (T1w), which also starts to increase at later time points after ischemia (10,11).

Recently, we reported that chemical exchange effects from fast exchanging pools may provide dominant contributions to the spin-lattice relaxation rate in the rotating frame, R1ρ, at high fields (12). Judicious selection of spin locking powers, and combinations of data acquired with different powers, can isolate the contribution of chemical exchange effects from those of non-chemical exchange related effects (12–14). Moreover, we have confirmed that spin-locking techniques can be made sensitive to changes in pH (13,15), yet remain relatively insensitive to other tissue parameters (16), and thus may provide relatively specific pH imaging. Here, we applied spin-lock sequences to monitor tissue acidosis in an animal stroke model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Contributions to R1ρ

In biological tissues, R1ρ is the superposition of several terms (14),

| (1) |

where R1ρDiff and R1ρEx are the relaxation rates due to water diffusion in the presence of gradients induced by intrinsic susceptibility variations and chemical exchange effects, respectively. R2w is the tissue water intrinsic transverse relaxation rate which is due mainly to dipolar relaxation effects. Here, we call R2win Eq. (1) the intrinsic R2w to distinguish it from the apparent R2w that is measured from multiple-echo sequences. Previous studies have shown that R1ρDiff contributes at very low spin-locking amplitudes (ω1 < 100 Hz) whereas R1ρEx is significant up to relatively high ω1 (several hundreds or thousands Hertz), but disperses as the locking field increases (12,14,17,18). In contrast, the intrinsic R2w is largely independent of ω1 (19). These different dependencies on ω1 provide a means to separate contributions of chemical exchange from those of other mechanisms. Fig. 1 gives an illustration based on a previous publication (18) to show the behavior of R1ρDiff, R1ρEx, and R2w as a function of locking power.

FIG. 1.

Illustration to show the behavior of R1ρDiff, R1ρEx, and R2w as a function of locking power.

Quantification of spin-locking and APT signals

A complete characterization of the dispersion of R1ρ, from which explicit exchange parameters may be extracted (12,14), would require measurements at multiple locking fields, but simpler approaches are more practical yet capture the essential features required to assess pH (13,15). We used the difference of R1ρ at high and moderately low locking powers to quantify the contribution of chemical exchange in spin-lock imaging.

| (2) |

A low value of ω1 = 316 Hz and high value of ω1 = 5620 Hz were chosen to effectively remove the diffusion and non-chemical exchange related effects. To optimize the high power so that the spin-locking techniques are more sensitive to pH, we defined a metric,

| (3) |

APT was quantified by a conventional asymmetric analysis (MTRasym) as well as one normalized by Tlw, which has been shown to be relatively more specific to chemical exchange effects than the conventional quantity MTRasym (20).

| (4) |

| (5) |

where S+ and S- are the labelled signals (acquired with RF irradiation on the solute protons) and the reference signal (acquired with the opposite frequency offset) respectively; S0 is the control signal acquired with no RF irradiation or with RF irradiation very far from the solute resonance frequency.

Sample and animal preparation

One rat was anesthetized with 5% isoflurane (ISO) and euthanized by decapitation. The brain was taken from the freshly sacrificed rat immediately. The intact tissues were washed quickly in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove residual blood. Then after addition of 4 x PBS (w/w), the tissues were homogenized with a motor-driven blade-type homogenizer (Brinkmann Polytron PT3000, Kinematica AG) at max speed ~23000 rpm for 2 × 30 s bursts. The homogenates were divided into two aliquots and pH was titrated to 7.0 and 6.6 at room temperature. The pHs of the two samples were measured with a pH meter before and after MRI measurements to ensure they were stable during the experiments. MRI measurements on the samples were performed as described below at 37 °C.

Five animals were subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusions (MCAO) as described. Anesthesia was induced with 4 % ISO in an induction chamber and maintained at 2–2.5 % during surgery. Lubricant ophthalmic ointment was applied to both eyes prior to surgery and a rectal temperature probe was used to maintain the animals core temperature. Depth of anesthesia was monitored using the paw pinch technique. Under an operating microscope, the left common carotid artery was carefully separated and isolated from the vagus nerve. A 30 mm, silicon-coated, 4-0 nylon suture (Doccol Corporation, Redlands, CA, USA) was routed into the left internal carotid artery and advanced until it occluded the MCA at a depth of 18–20 mm. A suture was tightened around the filament and the incision closed. The surgery took roughly 7 mins. Immediately after surgery, the rats were taken from the surgery room to the MRI scanner. The rats were secured on a custom-built holder using adhesive tape and a bite bar. A breathing sensor (SA instruments Inc., NY, USA) was placed under the ventral surface of the rat body. Breathing rate was monitored throughout the experiments. Animals were anesthetized with 2–3 % ISO for induction and 2 % for maintenance. A warm-air feedback system was used to ensure that the rat rectal temperature was maintained at approximately 37 °C throughout the experiments. At around 30 mins after surgery, the first MRI acquisitions were performed. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

MRI

Spin-lock experiments on tissue homogenates and spin-lock and APT images of rats in vivo were performed using a horizontal 7T Varian small animal magnet. The spin-lock preparation cluster has an initial 90° flip, a pair of on-resonance locking pulses applied along the direction of the transverse magnetization with selectable amplitudes and durations and separated by a 180° refocusing pulse, followed by a −90° flip back to the z direction. R1ρ dispersion curves were acquired with ω1 from 316 Hz to 5620 Hz. Spin-locking time (SLT) was varied as 1, 25, 50, 75, 100 ms and TR was 4 s. Spin-locking signals were acquired with varied ω1 for each SLT to reduce the potential for RF heating effects at high locking fields. The total acquisition time was roughly 4 mins to acquire data to derive each R1ρ dispersion and roughly 80 s to acquire spin-locking signals with two locking powers to calculate only ΔR1ρ.

The APT sequence contained a selective off-resonance rectangular irradiation pulse with amplitude of 1 μT, duration of 5 s and TR of 7 s. S+, S−, and S0 were acquired with RF irradiation frequency offsets at 1050 Hz, −1050 Hz, and 100,000 Hz, respectively (corresponding to 3.5 ppm, −3.5 ppm, and 333.3 ppm at 7 T). The total acquisition time for acquiring CEST signals to calculate MTRasym was roughly 42 s, which is a half of the 80 s taken for acquiring spin-locking signals to calculate only ΔR1ρ.

T1w (1/ R1w) was obtained using a selective inversion recovery (SIR) method (21). Apparent R2w was obtained using five echo times of 30, 50, 70, 90, and 110 ms. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) was also measured using a pulse gradient spin echo sequence with gradients applied simultaneously on three axes (gradient duration = 6 ms, separation = 12 ms, five b-values between 0 and 1000 s/mm2).

All images were acquired using single-shot spin-echo Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) readouts with triple references for phase correction and with matrix size 64 × 64, field of view 30 mm × 30 mm, and one acquisition. Before data acquisition, shimming was carefully performed so that the root mean square (RMS) deviation of B0 was less than 5 Hz. All images were acquired in 30 mins. Baseline and later images were acquired at 1–3 days before and at 0.5–1 h, 1–1.5 h, 1.5–2 h, and 2–2.5 h after the MCAO surgery.

Numerical simulation

Simulations were performed of the expected behavior of a two-pool (solute and water) model using coupled Bloch equations (16). Simulation parameters included: solute longitudinal and transverse relaxation times (1.5 s and 15 ms); water longitudinal and transverse relaxation times (1.5 s and 60 ms); solute concentration and resonance frequency offset (0.005 and 3 ppm). The solute-water exchange rates were set to be 10 kHz and 5 kHz to mimic normal and acidic tissues respectively. Sequence parameters (e.g. ω1, SLT, and B0) were the same as those used in the MRI experiments. The spin-locking signals were obtained numerically by integrating the appropriate differential equations through the sequence using the ordinary differential equation solver (ODE45) in Matlab 2013b (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

Data analysis

All data analyses were performed using Matlab R2013b. Spin-locking and APT images were smoothed by a 3 × 3 median filter before data processing. R1ρ was obtained by fitting the spin-locking data with a mono-exponential function voxel by voxel. The standard deviations and mean values of ΔR1ρ and ADC from the normal tissues in the right hemispheres were measured. Regions of interests (ROIs) in baseline maps were manually drawn on ΔR1ρ maps. ROI within the stroke in each rat obtained at 0.5–1 h were selected in the left hemisphere with ΔR1ρ values more than one standard deviation of those from normal tissues. ROIs of contralateral normal tissue were chosen to mirror the stroke ROIs. These ROIs were also used in other maps acquired at different time point after stroke. Data from those ROIs were used for statistical analysis. Student’s t-tests were employed to evaluate differences in parameters, which were considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05. To compare the lesion boundary between ΔR1ρ map and ADC map, we also drew the lesion boundary on ADC map at 0.5–1 h with ADC values more than one standard deviation of those from normal tissues.

RESULTS

Tissue homogenates

We used numerical simulations with different exchange rates and diluted tissue homogenates with different pH to evaluate the dependence of the spin-locking technique on pH. Fig. 2a and 2c show the simulation results and Figs. 2b and 2d show the measured R1ρ dispersion curves for the homogenates. R1ρ dispersion is clearly influenced by exchange rate or pH; the R1ρ value at low ω1 = 316 Hz (R1ρ(316 Hz)) increases after acidification, whereas the R1ρ value at higher ω1 (e.g. 5620 Hz) decreases after acidification (with a not quite significant p value 0.09 in Fig. 2c). This result is in agreement with a previous report of the effects of pH on exchange rates in the intermediate to fast exchange regime (22) and consistent with the theoretical expression of Chopra et al. (23) discussed below. Fig. 2b and 2d also show that ΔR1ρ values increased with decreasing exchange rate or pH.

FIG. 2.

R1ρ dispersion (a and c) and ΔR1ρ (b and d) from numerical simulations with different ksw (a and b) from measurements of tissue homogenates (diluted with 4 x PBS (w/w)) with different pH (c and d). Error bars in (c and d) represent the standard deviations of 5 measurements on one sample (* p < 0.05).

Animal experiments

Fig. 3 shows the R1ρ dispersion curves, ΔR1ρ(ω1) difference, ΔR1ρ, R1ρ(316 Hz), R1ρ(5620 Hz), MTRasym, normalized MTRasym, R1w, apparent R2w, and ADC on five rat brains before and at different time points after onset of stroke. Fig. 3a shows that the R1ρ dispersion curves from the lesion ROIs changed significantly at 0.5–1 h after onset of stroke. In particular R1ρ decreases at higher locking fields, corresponding to a shift in the inflexion point of the dispersion consistent with a decrease in the exchange rate or a shift to lower pH. Fig. 3c shows that ΔR1ρ values increased significantly consistent with the simulations for relatively fast exchanging protons and effects of decreasing pH in tissue homogenates in Fig. 2. Fig. 3b shows that the optimal high power to make the spin-locking techniques more sensitive to pH is in a range from 1778 Hz to 5620 Hz (note the dip in the curve at 1778 is interpreted as an artifact). R1ρ(5620 Hz), MTRasym, R1w, apparent R2w, and ADC change significantly after onset of stroke, but changes in R1ρ(316 Hz) and the normalized MTRasym did not reach significance, though the latter showed similar trends to MTRasym. The significant variation of R1w in lesion after onset of stroke is in agreement with previous reports (8,24–26), which suggests the necessity to use the normalized MTRasym to increase the specificity of CEST detection of exchange effect for our experimental settings (see following discussions). In addition, slightly elevated R1w in contralateral normal tissue can be also observed. This can be also found in a previous publication (10).

FIG. 3.

R1ρ dispersion (a), ΔR1ρ(ω1) difference (b), ΔR1ρ (c), R1ρ(316 Hz) (d), R1ρ(5620 Hz) (e), MTRasym (f), normalized MTRasym (g), R1w (h), apparent R2w (i), and ADC (j) from stroke lesions (red) and contralateral normal tissues (blue). Error bars represent the standard deviations across subjects (* p < 0.05).

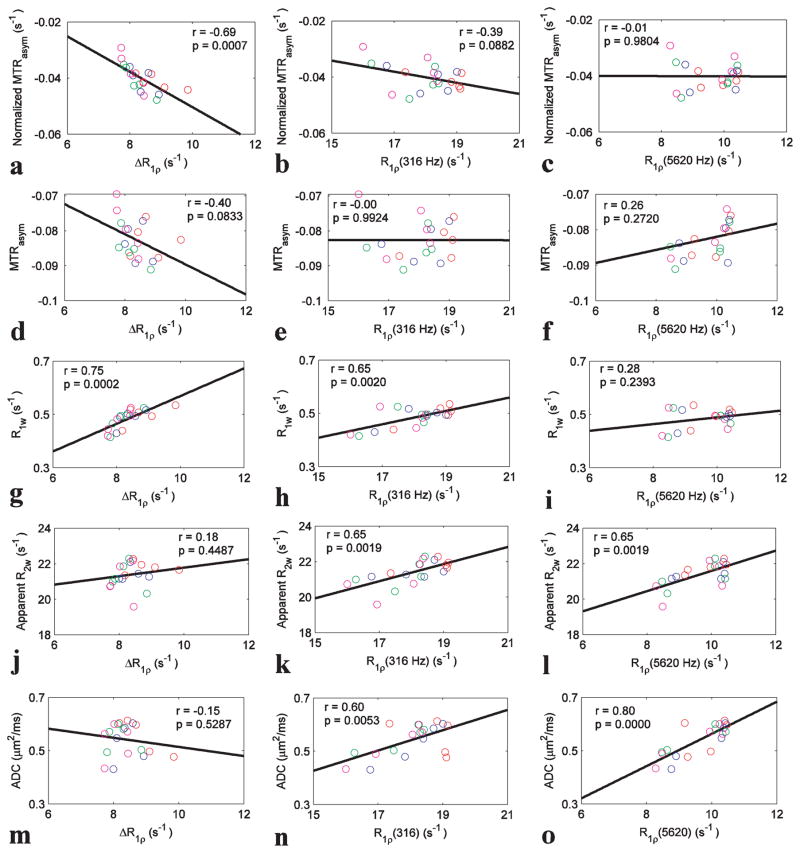

We quantified the correlations between the three spin-locking parameters (ΔR1ρ, R1ρ(316 Hz), and R1ρ(5620 Hz)) and both MTRasym metrics from the ischemic regions at different time points after onset of stroke, and results are shown in Fig. 4. Significant correlations with the normalized MTRasym were found for ΔR1ρ (Fig. 4a, p=0.0007), but not for R1ρ(316 Hz) (Fig. 4b, p=0.0882) or R1ρ(5620 Hz) (Fig. 4c, p=0.9804), confirming that ΔR1ρ, but not R1ρ acquired with a single ω1, is sensitive to the same parameters as the exchange measured by APT. We also correlated the spin-lock parameters with MTRasym, R1w, apparent R2w, and ADC. Significant correlations were found between ΔR1ρ and R1w (Fig. 4g, p=0.0002); between R1ρ(316 Hz) and R1w, apparent R2w, and ADC (Fig. 4h, 0.0020; Fig. 4k, 0.0019; and Fig. 4n, 0.0053, respectively), and between R1ρ(5620 Hz) and apparent R2w and ADC (Fig. 4l, p=0.0019 and Fig. 4o, p=0.0000, respectively).

Fig 4.

Summarized correlations of three spin-locking parameters (ΔR1ρ, R1ρ(316 Hz), and R1ρ(5620 Hz)) with five conventional MRI parameters (normalized MTRasym, MTRasym, R1w, apparent R2w, and ADC). The circles represent the mean values of each ROI from stroke lesion acquired at 0.5–1 h (red), 1–1.5 h (blue), 1.5–2 h (green), and 2–2.5 h (magenta) after onset of stroke. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) and p value of the correlation are provided. The solid line represents the linear regression of all data points.

Figures 5 shows parametric images of ΔR1ρ, normalized MTRasym, MTRasym, R1w, apparent R2w, and ADC, respectively, from a representative rat brain before and at different time points after onset of stroke. Parametric images from other rats are shown in Sup. Fig. S1–S4. The fitting of R1ρ is good which can be seen from the mono-exponential fitting of spin-locking signals in Sup. Fig. S5. It can be seen that lesion regions detected by ΔR1ρ are larger than seen in ADC images. This spatial mismatch suggests that the pH-weighted imaging quantified by ΔR1ρ may be potentially used in detecting the ischemic penumbra (2).

Fig. 5.

Maps of ΔR1ρ, normalized MTRasym, R1w, apparent R2w, and ADC from one representative rat brain before and at different time point after onset of stroke. ROIs of lesion and contralateral normal tissue are shown in ΔR1ρ maps.

DISCUSSION

This study reports the application of spin-locking techniques at high field for the early characterization of ischemic stroke. Through subtraction of R1ρ values acquired at two selected ω1, the contribution of chemical exchange effects can be isolated from those of other non-chemical exchange related effects. Chopra et al. (23) have provided a theoretical expression for the contribution of chemical exchange to R1ρ. The relevant exchange-dependent term depends directly on the ratio , where k is the proton exchange rate and Δω0 is the chemical shift of the exchanging species relative to water. At high locking fields, this increases with k or pH, whereas at low locking fields and high exchange rates (high pH) it can decrease with k. This behavior was seen in tissue homogenates and areas of stroke. Moreover, ΔR1ρ is then expected to increase as k or pH decrease. The precise behavior will depend on the relative values of k and Δω0. From the dispersion curves of the homogenates, the decrease in R1ρ from its low field value to the high locking field value reaches halfway at a locking field of ≈ 1800 Hz, suggesting the mean exchange rate of the protons ≈ 11 kHz. This would be typical of hydroxyls and justifies the choice of parameters in the simulation.

Based on the definition of MTRasym (27) and R1ρ (23), the normalized MTRasym under weak saturation pulse approximation (no direct water saturation (DS) effect) mainly depends on exchange effect, and the R1ρ mainly depends on exchange and R2w. At 9.4 T and with relatively low irradiation power, the DS effect is weak and thus our CEST experiments roughly obey the weak saturation pulse approximation. To evaluate the relative contributions of exchange and R2w, we examined correlations between the three spin-locking parameters and the normalized MTRasym. Significant correlations between ΔR1ρ and the normalized MTRasym in Fig. 4a suggests that ΔR1ρ and APT are sensitive to similar factors affecting exchange rates, which in this case are likely changes in tissue pH. In Fig. 3, both ΔR1ρ and the normalized MTRasym from areas of stroke change at 0.5–1 h, and then return slowly toward the values of contralateral normal tissues, which differs from the behaviors of R1w and R1ρ(5620 Hz) which have larger differences between lesions and contralateral normal tissues at longer time after stroke. This further suggests that ΔR1ρ may reflect the same process as the normalized MTRasym. There is no significant difference between lesion regions and contralateral normal tissues for the normalized MTRasym in Fig. 3g, which may be due to the T1w normalization, which enhances specificity to exchange.

Although spin-locking has been previously applied for detecting ischemic stroke (28–31), most of these studies acquired R1ρ values at only a single locking field ω1, but not ΔR1ρ. Our studies indicate that R1ρ values acquired with a single ω1 do not correlate well with the normalized MTRasym and by themselves cannot isolate the effects of exchange or pH. R1ρ values at any single locking field reflect exchange and dipolar contributions and also scale with the amount of solute within the tissues. After ischemia there are often changes in tissue water caused by edema and/or cellular swelling. The correlations of R1ρ at low and high frequencies with R2w suggest water content did change. Subtraction of R1ρ values from different regions of the dispersion curve will emphasize contributions from exchange that are more specific to pH, but still reflect total tissue composition. Normalization of ΔR1ρ by e.g. the mean R1ρ or some other combination may remove the influence of changes in water content as described in our earlier works (13,14).

Recently, Sun et.al. evaluated the pH-dependence of APT via correlation between the normalized MTRasym and MRS measurements of tissue acidosis (20). Here we performed correlations between spin-locking parameters and the normalized MTRasym to compare their changes over time. The method used to measure MTRasym can be influenced by relayed nuclear overhauser enhancement (rNOE), MT, and MT asymmetry effects (32,33). As a result, the normalized MTRasym images are inhomogeneous and their values are negative in both lesions and contralateral normal tissues. However, rNOE and MT are relatively stable in the acute stage of stroke at sufficiently high irradiation power and long irradiation time, where the dipolar effects dominate the exchange effects (10,34), so the normalized MTRasym is less influenced by potential changes in rNOE and MT due to tissue acidification. Although other quantification methods have been suggested for increasing the specificity of APT imaging, they either require longer acquisition times or reduce the sensitivity. For example, the multiple-pool Lorentzian fit of CEST Z-spectra requires the acquisition of complete Z-spectra at multiple frequencies, which lengthens the total acquisition time and is not appropriate for some practical applications (11,35–40). In addition, some protons, e.g. fast exchanging amine protons, do not produce Lorentzian lineshapes and their effects coalesce with the water peak, which causes errors in multiple-pool Lorentzian fitting (33). Specially designed pulsed saturation schemes e.g. chemical exchange rotation transfer (CERT) (32,41) and variable-delayed multi-pulse saturation (VDMP) (42,43), usually do not need to acquire whole Z-spectra, but they increase specificity at the expense of sensitivity. Here, we performed a 5 s irradiation with power of 1 μT to obtain ~1.5% MTRasym contrast between the lesion and the contralateral normal tissue. In other studies with different sequence parameters (2,6,8,34,44), the MTRasym contrast between the lesion and the contralateral normal tissue was usually higher. However, optimizing APT sequence parameters in vivo is challenging due to overlapping signals from other exchanging pools. For example, the irradiation power may be limited by nearby amines which are more significant at higher powers and contaminate APT signals (33). The inhomogeneous ΔR1ρ and the normalized MTRasym signals in some rat brains in baseline measurements may be caused by inhomogeneous B1 fields to which both methods are sensitive.

Our results disagree with a previous study (45) which found that MTRasym is strongly correlated with MRS-measured pH values in acute stroke models. This discrepancy may be due to the different experimental settings. A recent study indicates that MTRasym is sensitive to T1w with lower irradiation powers, but is roughly insensitive to T1w with higher irradiation powers (46). Longer T1w causes greater MTRasym, but also causes greater DS which decreases MTRasym (47). Therefore, at higher irradiation powers, MTRasym should have reduced dependency on T1w. In the previous study (45) at 4.7 T and with short-pulse irradiation (6.6 ms) and thus broad bandwidth, MTRasym may be affected less by variations in T1w and thus correlated well with pH. By contrast, in our study at 7 T and in Sun et.al.’s study (20) the longer irradiation pulse and lower power used had less DS effect, so MTRasym then depends more on T1w, reducing its correlation with pH. After normalizing for T1w, the normalized MTRasym showed significant correlation with pH. The previous study (45) also showed that R1ρ acquired with ω1 of 2250 Hz correlated with MRS measured pH. At this locking power, R1ρ has contributions from both the apparent R2w and chemical exchange, based on our simulation in Fig. 2a, and thus should depend on pH. However, in principle, a stronger correlation with pH is achieved by removing the apparent R2w.

ΔR1ρ is sensitive to fast exchanging pools such as glutamate, glucose, and proteins. During ischemia, the content of these molecules may change which may confound the interpretation of spin lock imaging. Although the mean exchange rate can be derived from the R1ρ dispersion, a simple two-pool model may not be appropriate for use in complex biological tissues. Another drawback of ΔR1ρ is that it requires high ω1 and thus its specific absorption rate (SAR) is relatively high. In addition, the exchange contribution to R1ρ decreases at lower fields as used in clinical scanners (12), so spin-locking techniques for detecting pH changes may be limited to preclinical applications.

CONCLUSION

We show that ΔR1ρ can be used to provide pH-weighted imaging, and can be applied for characterizing acute ischemic stroke in rat brain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding information

National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, Grant/Award Number: EB017873

Abbreviations used

- R1ρ

spin-lattice relaxation rate in the rotating frame

- APT

amide proton transfer

- CEST

chemical exchange saturation transfer

- R1ρDiff

spin-lattice relaxation rate in the rotating frame due to diffusion through susceptibility gradients

- R1ρEx

spin-lattice relaxation rate in the rotating frame due to chemical exchange effect

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- SIR

selective inversion recovery

- ADC

apparent diffusion coefficient

- EPI

echo planar imaging

- ROI

regions of interest

- MTRasym

magnetization transfer ratio with asymmetric analysis

- rNOE

relayed nuclear overhauser enhancement

- CERT

chemical exchange rotation transfer

- VDMP

variable-delayed multi-pulse saturation

- SAR

specific absorption rate

- SLT

spin-locking time

References

- 1.Sun PZ, Zhou JY, Sun WY, Huang J, van Zijl PCM. Detection of the ischemic penumbra using pH-weighted MRI. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2007;27(6):1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou JY, van Zijl PCM. Defining an Acidosis-Based Ischemic Penumbra from pH-Weighted MRI. Translational Stroke Research. 2012;3(1):76–83. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0110-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tietze A, Blicher J, Mikkelsen IK, et al. Assessment of ischemic penumbra in patients with hyperacute stroke using amide proton transfer (APT) chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2014;27(2):163–174. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harston GWJ, Tee YK, Blockley N, et al. Identifying the ischaemic penumbra using pH-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Brain. 2015;138:36–42. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadian DG, Frackowiak RSJ, Crockard HA, et al. Acute Cerebral-Ischemia - Concurrent Changes in Cerebral Blood-Flow, Energy Metabolites, Ph, and Lactate Measured with Hydrogen Clearance and P-31 and H-1 Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance Spectroscopy. 1. Methodology. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1987;7(2):199–206. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1987.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou JY, Payen JF, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PCM. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(8):1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaiss M, Bachert P. Exchange-dependent relaxation in the rotating frame for slow and intermediate exchange - modeling off-resonant spin-lock and chemical exchange saturation transfer. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2013;26(5):507–518. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zong XP, Wang P, Kim SG, Jin T. Sensitivity and Source of Amine-Proton Exchange and Amide-Proton Transfer Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Cerebral Ischemia. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;71(1):118–132. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin T, Wang P, Zong XP, Kim SG. Magnetic resonance imaging of the Amine-Proton EXchange (APEX) dependent contrast. Neuroimage. 2012;59(2):1218–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Zu ZL, Zaiss M, et al. Imaging of amide proton transfer and nuclear Overhauser enhancement in ischemic stroke with corrections for competing effects. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2015;28(2):200–209. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang XY, Wang F, Afzal A, et al. A new NOE-mediated MT signal at around-1. 6 ppm for detecting ischemic stroke in rat brain. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2016;34(8):1100–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobb JG, Xie JP, Gore JC. Contributions of chemical and diffusive exchange to T1 dispersion. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2013;69(5):1357–1366. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobb JG, Li K, Xie JP, Gochberg DF, Gore JC. Exchange-mediated contrast in CEST and spin-lock imaging. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2014;32(1):28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spear JT, Gore JC. New insights into rotating frame relaxation at high field. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2016;29(9):1258–1273. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zu ZL, Li H, Jiang XY, Gore JC. Spin-Lock Imaging of Exogenous Exchange-Based Contrast Agents to Assess Tissue pH. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zu ZL, Spear J, Li H, Xu JZ, Gore JC. Measurement of regional cerebral glucose uptake by magnetic resonance spin-lock imaging. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2014;32(9):1078–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spear JT, Zu ZL, Gore JC. Dispersion of Relaxation Rates in the Rotating Frame Under the Action of Spin-Locking Pulses and Diffusion in Inhomogeneous Magnetic Fields. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;71(5):1906–1911. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spear JT, Gore JC. Effects of diffusion in magnetically inhomogeneous media on rotating frame spin-lattice relaxation. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2014;249:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin T, Mehrens H, Wang P, Kim SG. Glucose metabolism-weighted imaging with chemical exchange-sensitive MRI of 2-deoxyglucose (2DG) in brain: Sensitivity and biological sources. Neuroimage. 2016;143:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun PZ, Cheung JS, Wang EF, Lo EH. Association between pH-weighted endogenous amide proton chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI and tissue lactic acidosis during acute ischemic stroke. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2011;31(8):1743–1750. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gochberg DF, Gore JC. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging via selective inversion recovery with short repetition times. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;57(2):437–441. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin T, Kim SG. Characterization of non-hemodynamic functional signal measured by spin-lock fMRI. Neuroimage. 2013;78:385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chopra S, Mcclung RED, Jordan RB. Rotating-Frame Relaxation Rates of Solvent Molecules in Solutions of Paramagnetic-Ions Undergoing Solvent Exchange. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1984;59(3):361–372. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grohn OHJ, Makela HI, Lukkarinen JA, et al. On- and off-resonance T-1 rho MRI in acute cerebral ischemia of the rat. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;49(1):172–176. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barber PA, Hoyte L, Kirk D, et al. Early T1- and T2-weighted MRI signatures of transient and permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in a murine stroke model studied at 9. 4 T. Neurosci Lett. 2005;388(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur J, Tuor UI, Zhao Z, et al. Quantified T-1 as an adjunct to apparent diffusion coefficient for early infarct detection: a high-field magnetic resonance study in a rat stroke model. International Journal of Stroke. 2009;4(3):159–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou JY, van Zijl PCM. Chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging and spectroscopy. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2006;48(2–3):109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grohn OHJ, Lukkarinen JA, Silvennoinen MJ, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging assessment of cerebral ischemia in rat using on-resonance T-1 in the rotating frame. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;42(2):268–276. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199908)42:2<268::aid-mrm8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grohn OHJ, Kettunen MI, Makela HI, et al. Early detection of irreversible cerebral ischemia in the rat using dispersion of the magnetic resonance imaging relaxation time, T-1p. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2000;20(10):1457–1466. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kettunen MI, Grohn OHJ, Penttonen M, Kauppinen RA. Cerebral T-1 rho relaxation time increases immediately upon global ischemia in the rat independently of blood glucose and anoxic depolarization. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;46(3):565–572. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jokivarsi KT, Hiltunen Y, Grohn H, et al. Estimation of the Onset Time of Cerebral Ischemia Using T-1 rho and T-2 MRI in Rats. Stroke. 2010;41(10):2335–2340. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.587394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zu ZL, Xu JZ, Li H, et al. Imaging Amide Proton Transfer and Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement Using Chemical Exchange Rotation Transfer (CERT) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;72(2):471–476. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang XY, Wang F, Li H, et al. Accuracy in the quantification of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and relayed nuclear Overhauser enhancement (rNOE) saturation transfer effects. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2017 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin T, Wang P, Zong XP, Kim SG. MR imaging of the amide-proton transfer effect and the pH-insensitive nuclear overhauser effect at 9. 4 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2013;69(3):760–770. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaiss M, Schmitt B, Bachert P. Quantitative separation of CEST effect from magnetization transfer and spillover effects by Lorentzian-line-fit analysis of z-spectra. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2011;211(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desmond KL, Moosvi F, Stanisz GJ. Mapping of Amide, Amine, and Aliphatic Peaks in the CEST Spectra of Murine Xenografts at 7 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;71(5):1841–1853. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang F, Qi HX, Zu ZL, et al. Multiparametric MRI reveals dynamic changes in molecular signatures of injured spinal cord in monkeys. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2015;74(4):1125–1137. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heo HY, Zhang Y, Jiang SS, Lee DH, Zhou JY. Quantitative Assessment of Amide Proton Transfer (APT) and Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement (NOE) Imaging with Extrapolated Semisolid Magnetization Transfer Reference (EMR) Signals: II. Comparison of Three EMR Models and Application to Human Brain Glioma at 3 Tesla. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;75(4):1630–1639. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heo HY, Zhang Y, Lee DH, Hong XH, Zhou JY. Quantitative Assessment of Amide Proton Transfer (APT) and Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement (NOE) Imaging with Extrapolated Semi-Solid Magnetization Transfer Reference (EMR) Signals: Application to a Rat Glioma Model at 4. 7 Tesla. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;75(1):137–149. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leigh R, Knutsson L, Zhou JY, Van Zijl PC. Imaging the physiological evolution of the ischemic penumbra in acute ischemic stroke. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0271678X17700913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zu ZL, Janve VA, Xu JZ, et al. A new method for detecting exchanging amide protons using chemical exchange rotation transfer. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2013;69(3):637–647. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu JD, Yadav NN, Bar-Shir A, et al. Variable Delay Multi-Pulse Train for Fast Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer and Relayed-Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;71(5):1798–1812. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu X, Yadav NN, Zeng HF, et al. Magnetization Transfer Contrast-Suppressed Imaging of Amide Proton Transfer and Relayed Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer Effects in the Human Brain at 7T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;75(1):88–96. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou JY, Wilson DA, Sun PZ, Klaus JA, van Zijl PCM. Quantitative description of proton exchange processes between water and endogenous and exogenous agents for WEX, CEST, and APT experiments. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2004;51(5):945–952. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jokivarsi KT, Grohn HI, Grohn OH, Kauppinen RA. Proton transfer ratio, lactate, and intracellular pH in acute cerebral ischemia. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;57(4):647–653. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heo HY, Lee DH, Zhang Y, et al. Insight into the quantitative metrics of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2017;77(5):1853–1865. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang XY, Wang F, Li H, et al. CEST imaging of fast exchanging amine pools with corrections for competing effects at 9.4 T. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2017 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.