Abstract

Introduction

Postoperative delirium is a serious and common complication in older adults following total joint arthroplasties (TJA). It is associated with increased risk of postoperative complications, mortality, length of hospital stay and postdischarge institutionalisation. Thus, it has a negative impact on the health-related quality of life of the patient and poses a large economic burden. This study aims to characterise the incidence of postoperative delirium following TJA in the South East Asian population and investigate any risk factors or associated outcomes.

Methods and analysis

This is a single-centre prospective observational study recruiting patients between 65 and 90 years old undergoing elective total knee arthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty. Exclusion criteria included patients with clinically diagnosed dementia. Preoperative and intraoperative data will be obtained prospectively. The primary outcome will be the presence of postoperative delirium assessed using the Confusion Assessment Method on postoperative days 1, 2 and 3 and day of discharge. Other secondary outcomes assessed postoperatively will include hospital outcomes, pain at rest, knee and hip function, health-related quality of life and Postoperative Morbidity Survey-defined morbidity. Data will be analysed to calculate the incidence of postoperative delirium. Potential risk factors and any associated outcomes of postoperative delirium will also be determined.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Singapore General Hospital Institutional Review Board (SGH IRB) (CIRB Ref: 2017/2467) and is registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov registry (Identified: NCT03260218). An informed consent form will be signed by all participants before recruitment and translators will be made available to non-English-speaking participants. The results of this study will be presented at international conferences and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal. The data collected will also be made available in a public data repository.

Trial registration number

Keywords: postoperative, delirium, total joint arthroplasty, incidence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to evaluate the incidence of postoperative delirium in the elderly above 65 years old following total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty in Singapore.

Association of variables to occurrence of postoperative delirium that have not been well studied such as handgrip strength, STOP-Bang score and long-term outcomes including knee function and health-related quality of life will be analysed.

The Confusion Assessment Method will be used, which is a gold standard measure for detection of delirium.

The study is conducted in a single centre in Singapore which may limit the generalisability of the results of the study.

Delirium will be only assessed once a day, and the presence of delirium may be missed due to the fluctuating nature of the condition.

Introduction

Delirium is a neurocognitive disorder characterised by a disturbance in attention, level of consciousness and cognition, in which symptoms are acute in onset and may fluctuate in severity throughout the day.1 Delirium is a common perioperative complication in older adults following total joint arthroplasty (TJA). The incidence of postoperative delirium following TJA may be as high as 17%,2 although there are no data from the South East Asian population, exposing a knowledge gap.

Patients with delirium after any surgery have an increased risk of major postoperative complications and increased mortality.3 4 They also experience significantly longer hospital stay and are at increased risk of subsequent postdischarge institutionalisation,4–6 which increases total procedural cost.7 With the demand of total hip arthroplasty (THA) expected to rise by almost twofold and that for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) by almost sevenfold by 2030,8 postoperative delirium is likely to become a significant health and economic burden. However, the impact of delirium on outcomes after TJA has not been well reported, identifying a potential knowledge gap. Furthermore, due to these various negative outcomes of postoperative delirium, it is important to characterise the risk factors associated with postoperative delirium. Older age has been reported as one of the most important risk factors for developing postoperative delirium.9 10 According to an existing study, the average age of the population undergoing TJA is 71 years, and majority of patients are 65 years or older (81.3% for total knee replacement and 69.5% for total hip replacement).7 Thus, the population under study is particularly at risk to postoperative delirium. Other important predisposing risk factors include pre-existing cognitive impairment, poor physical status and alcohol abuse.5 9 10 While these are common risk factors for the TJA population, few studies have investigated if these risk factors also predispose to postoperative delirium following TJA specifically. There is a need to investigate the presence of other risk factors particular to TJA, especially if any are modifiable. As most of such operations are elective, there may be an opportunity to address the modifiable risk factors to optimise the patient prior to the surgery or to implement perioperative management strategies to mitigate the negative outcomes of postoperative delirium.

Given the limited knowledge on the incidence, risk factors and outcomes of postoperative delirium in the South East Asian population, together with the increasing number of older adults undergoing TJA, this study’s primary aim is to characterise the incidence of delirium among older adults undergoing elective TJA. Our secondary aim is to identify risk factors of postoperative delirium following elective TJA among the elderly, including demography, comorbidities, clinical laboratory data and drugs used in the perioperative period. Our final aim is to investigate the impact of postoperative delirium on the immediate and longer term postoperative recovery after TJA. Identifying such risk factors and associated clinical or functional outcomes may be important in guiding perioperative care of prospective patients undergoing TJA.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (SingHealth CIRB 2017/2467) prior to starting the study. This is a single-centre, prospective observational study conducted at a tertiary public hospital in Singapore (Singapore General Hospital (SGH)). SGH is the largest hospital in Singapore with 1597 beds in 2013.11 A total of 1500 TKA surgeries were performed in SGH in 2007, accounting for 65% of all TKA surgeries in Singapore.12

Study population

Patients aged between 65 and 90 undergoing elective total joint (hip or knee) replacement surgery in SGH will be screened for eligibility. A minimum age of 65 years old was chosen to be recruited based on the original study which developed and validated Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).13 Exclusion criteria include patients who are unable to give their own consent for the surgery and anaesthesia. Patients with clinically diagnosed dementia will also be excluded from the study as they are deemed not to have capacity for consent.

All eligible patients will be identified from the appointment list of attendees of the preoperative evaluation clinic (PEC) at SGH where the patients attend for preoperative assessment and counselling by the anaesthetists. Patients between 65 and 90 years old undergoing TKA or THA will be approached and invited to enrol into the study. Informed consent will be obtained then.

Preoperative data

We will collect the patients’ baseline characteristics preoperatively. This will allow for the identification of risk factors or correction of confounding factors during the analysis of the results.

Data on cognitive status

Before the operation, each patient will be interviewed to assess their baseline cognitive status. The Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) will be used, which is an 11-question screening tool used to evaluate the cognitive aspects of mental function.14 It measures domains of cognitive function including memory, attention, language, praxis and visuospatial ability. A score of 0–30 can be obtained with higher values denoting better cognitive function. A score of <24 suggests cognitive impairment. The test was adapted for use in Singapore, and the changes and reasons for the changes are shown in the table in online supplementary file 1. In addition, the test will be administered in English, Chinese or Malay, according to the language the participant is most well-versed in. The Chinese version of MMSE that will be used was previously validated in Shanghai15 and in Singapore.16 The Malay version of MMSE that will be used was developed by translation from the English version. The Chinese and Malay versions of MMSE have similar test questions and are scored the same way as the English version, but there are some differences shown in online supplementary file 2. However, a recent study in Singapore has shown that there were significant ethnic differences in unadjusted MMSE scores using the different versions of MMSE. These differences were not eliminated after accounting for known correlates of MMSE performance such as socioeconomic status, comorbid illnesses, functional health status and health-related behaviours.17

bmjopen-2017-019426supp001.pdf (232.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019426supp002.pdf (284.1KB, pdf)

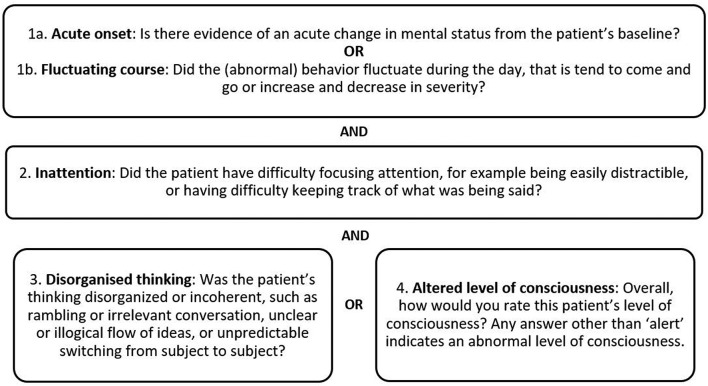

The CAM will also be performed prior to the operation to obtain the patient’s baseline score. CAM is a screening instrument for delirium intended for use by non-psychiatrically trained clinicians based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III-R criteria.18 It involves an interview where delirium can be diagnosed using the CAM algorithm based on four criteria: (1) acute onset or fluctuating course; (2) inattention; (3) disorganised thinking; and (4) altered level of consciousness, as can be seen in figure 1. Delirium is said to be present if criteria 1 and 2 and either of 3 or 4 are present. CAM has a sensitivity of 94%–100%, specificity of 90%–95% and high interobserver reliability.13 This enables a new case of delirium in the postoperative period to be detected.

Figure 1.

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) criteria: at least one criterion on each of the three rows must be met for a positive result.

Other data

Sensory impairment will be assessed during the preoperative interviews. Patients will be asked to wear their visual or hearing aids during these interviews. A patient will be considered to have visual or hearing impairment if the research member conducting the interview is unable to perform the interview normally due to the sensory impairment, such as raising his/her voice for a patient with impaired hearing. The preoperative MMSE assessment provides a useful tool in assessing for visual impairment as it has several vision-dependent items (naming objects, following a written command, instructions to handle a piece of paper, writing a sentence, copying a diagram).19

The grip strength of each patient will also be measured using the JAMAR Plus+ Digital Hand Dynamometer (Sammons Preston, Bolingbrook, IL). Hand dynamometry has acceptable reliability and validity for measurement of grip strength,20 which can serve as an indicator of muscle function and physical fitness. The normative value of handgrip strength for elderly in Singapore has recently been published, decreasing from 18.6 and 29.3 kg for women and men, respectively, in the 65–69 age group to 12.4 and 18.5 kg in the 85+ age group.21

The patient baseline characteristics will be obtained from the medical records. All perioperative data will be prospectively entered into the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database. This will include data regarding patient’s demographics, smoking history, alcohol history, pre-existing medical conditions and preoperative medications.

Each patient will also be rated preoperatively by an anaesthesiologist in the PEC based on the American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification.22 It is a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represents a completely healthy fit patient and 5 represents a moribund patient who is not expected to live 24 hours with or without surgery. For our analysis, we will be calculating each patient’s perioperative risk based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index.23 Nineteen different comorbid medical conditions are assigned weights of 1, 2, 3 and 6 according to the degree to which they predicted mortality, and the sum of these values gives the final score. It is a valid method of estimating risk of mortality resulting from comorbidities.24 The STOP-Bang score will also be calculated for each patient. The STOP-Bang questionnaire was a good screening tool for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnoea, with a sensitivity of 89.0% and accuracy of 79.1%.25 Preoperative laboratory results, including data about haemoglobin or creatinine level, will also be collected.

Preoperative baseline functional scores for TKA (Oxford Knee Score (OKS), Knee Society Function Score (KSFS) and Knee Society Knee Score (KSKS)) and for THA (Harris Hip Score (HHS) and Parker Mobility Score (PMS)) will be obtained from the patient by trained staff at the Orthopaedic Diagnostic Centre (ODC). These assessments will be further discussed in the ‘Postoperative data’ section.

The preoperative data collection form (DCF) can be seen in online supplementary file 3.

bmjopen-2017-019426supp003.pdf (435.7KB, pdf)

Intraoperative data

Data regarding the surgery will be collected. Intraoperative data include type of arthroplasty performed (TKA or THA), type of anaesthesia (spinal, general or other anaesthesia), use of femoral nerve block, intraoperative drug use, tourniquet time, intra-articular injections and blood transfusion (number of pints transfused). Occurrence of hypotension, which is defined as a mean arterial pressure <60 mm Hg, and its duration will also be recorded.

Postoperative data

Primary outcome

The primary outcome will be the presence of postoperative delirium following TJA. Each patient will be assessed for delirium on postoperative days (POD) 1, 2 and 3 in the wards at 07:00 as well as the day of discharge. Delirium will not be evaluated on POD 0 due to difficulty in differentiating delirium from the effects of residual anaesthesia.

CAM will be used to detect postoperative delirium and delirium severity. Delirium is said to be present if the patient meets the CAM criteria for any of the postoperative assessments. Patients assessed to have delirium will be referred to the psychiatrists for a formal diagnosis based on the DSM-V criteria and for further management.

Short-term secondary outcomes

Postoperative complications will be assessed by the Postoperative Morbidity Survey (POMS). This is a 9-point survey that can be easily used by clinicians to characterise short-term postoperative morbidity in their respective settings.26 It is designed to only identify morbidity of a type and severity that could prolong length of stay (LOS). Using POMS, postoperative morbidity outcomes can be dichotomised into two categories—the absence and presence of morbidity. The POMS instrument can be seen in online supplementary file 4. POMS will be assessed on PODs 3, 5, 8 and 15, as recommended by the original literature.26 It has also been reported to have good inter-rater reliability and acceptability to patients.27

bmjopen-2017-019426supp004.pdf (334.3KB, pdf)

In addition, the Comprehensive Complication Index (CoCI) will also be used to assess postoperative complications, which is based on the widely established Clavien-Dindo classification. The score is the sum of all complications attributable to a single procedure, weighted according to their respective severities. The index thus integrates the severity of all major and minor postoperative complications in a patient, minimising the risk of ignoring minor complications. The score ranges from 0 (no complications) to 100 (death).28 The CoCI will be assessed on the day of discharge and POD 30. It is more sensitive than other existing traditional endpoints to detect treatment effects on postoperative morbidity.28

Other postoperative outcomes that will be obtained include postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), LOS and 30-day readmission rates. A 30-day readmission is defined as readmission within 30 days of initial admission. The reason for readmission will also be obtained.

Long-term secondary outcomes

Longer term outcomes such as functional and health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) outcomes will also be recorded by the ODC total joint registry at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years and 5 years postoperatively. The ODC tracks clinical outcome measures during preoperative and postoperative functional assessments of the patients in SGH. Their total joint registry contains data about outcomes from knee and hip arthroplasties.

For patients undergoing TKA, knee function will be measured using the new KSKS and KSFS.29 The physician-derived KSKS measures alignment, stability, joint motion and symptoms experienced. The patient-derived KSFS evaluates use of walking aids and supports, ability to complete standard activities of daily living and discretionary activities. The KSKS and KSFS each range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). Both provide a validated rating of the functional outcome of the patient and knee prosthesis after TKA.30 In addition, the OKS31 will also be used, which is a 12-item, patient-assessed questionnaire designed specifically for use in patients undergoing TKA.7 It assesses an individual’s pain and physical disability. Each item is scored from 1 (least difficulty/severity) to 5 (most difficulty/severity), and individual item scores are summed to yield an overall score ranging from 12 (no pain or limitation) to 60 (severe pain or limitation). A lower OKS indicates a better outcome. It has good reliability, construct and content validity, and sensitivity to clinically important changes over time.31 32 It correlates strongly with pain but less with postoperative functioning.33

For patients undergoing THA, hip function will be measured using the HHS.34 The HHS is a clinician-based tool to assess the outcomes of hip surgery such as THA. It contains four subscales—pain severity, function, absence of deformity and range of motion. The total score ranges from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). It showed high validity and reliability when used to study the clinical outcome of THA.35 Hip function will also be measured using the PMS.36 A score of 1 represents a patient who does not require a walking aid and has no restriction in walking distance, while a score of 10 represents a patient who is mostly bedbound. It is reliable and a valid predictor of in-hospital and long-term outcomes.36–38 Outcomes for THA will only be recorded at 6 months and 2 years, unlike the other long-term secondary outcomes.

HRQoL will be assessed based on the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)39 to obtain a baseline score. It consists of 36 questions categorised into eight domains (physical functioning, bodily pain, role limitations due to physical health problems, role limitations due to personal or emotional problems, emotional well-being, social functioning, energy/fatigue and general health perceptions). This instrument is shown in online supplementary file 5. Higher scores indicate better health status and quality of life.

bmjopen-2017-019426supp005.pdf (556.5KB, pdf)

Days alive and out of hospital (DAOH) will also be determined for each patient at 1, 6 and 12 months to assess the overall impact of postoperative delirium on morbidity and mortality. DAOH will be calculated based on death date (if present) and duration of all subsequent hospitalisations until the follow-up date. This will be recorded as a percentage by dividing the DAOH by the total potential follow-up period, which is the time period between the operation and the respective dates of follow-up (1, 6 and 12 months). %DAOH is a useful measure as it emphasises the deaths occurring early in follow-up and takes into account the severity (duration) of any hospitalisation.40

Postoperative risk factors

Other postoperative data will be collected as variables for risk factors.

Postoperative pain at rest will be evaluated using the pain visual analogue scale during the same visit as CAM on PODs 1, 2 and 3. Each patient will score pain experienced at rest on a scale, with 0=no pain and 10=maximum pain.

Sensory impairment will also be assessed during the postoperative interviews similar to the preoperative assessments.

The postoperative DCF can be seen in online supplementary file 6.

bmjopen-2017-019426supp006.pdf (436.2KB, pdf)

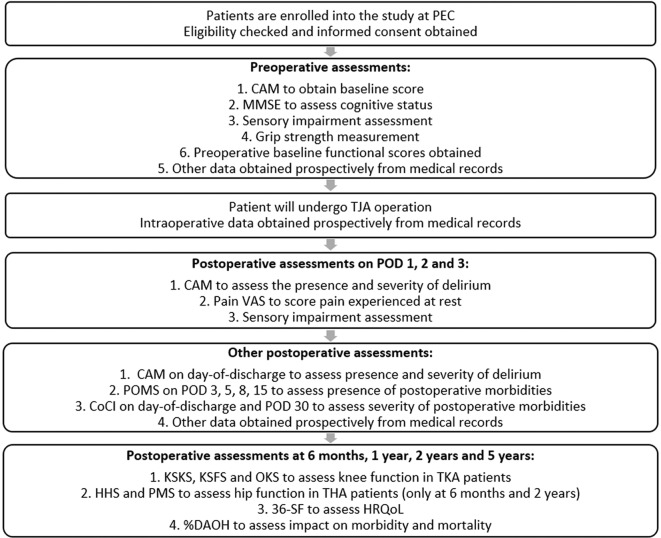

The flow chart shown in figure 2 depicts a patient’s journey starting from enrolment in the PEC.

Figure 2.

Flow chart depicting a patient’s timeline during the study. CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; CoCI, Comprehensive Complication Index; DAOH, days alive and out of hospital; HHS, Harris Hip Score; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; KSFS, Knee Society Function Score; KSKS, Knee Society Knee Score; MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; OKS, Oxford Knee Score; PEC, preoperative evaluation clinic; PMS, Parker Mobility Score; POD, postoperative day; POMS, Postoperative Morbidity Survey; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TJA, total joint arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Data management

Patient data will be kept confidential throughout the study. All electronic study data entry, storage and analysis will be done according to institutional data security policy using password-protected data in secure systems.

The patient data collected will be deidentified and the key kept securely separated with access limited to principal investigator and coinvestigators. A study-related identification number given to each patient will be used on the case report form. Research members will enter the deidentified data into the REDCap tool hosted on a secure server at SGH.36 The hard copy of the research data will be securely stored within the department. The soft copy of research data will be saved in a password-protected file and will be stored in institution-approved login-protected system and encrypted hard drive. Only study members will have access to the data.

Power and sample size calculations

The primary aim of the study is to characterise the incidence of postoperative delirium following TJA, which is estimated at around 10% based on existing literature.2 Using this estimate, 150 patients are enough to detect the incidence with a precision of 5% and confidence level of 95%.

However, this study will also aim to detect potential factors which may be correlated to postoperative delirium by logistic regression. Thus, we will target to recruit 500 patients such that we are able to investigate the risk factors and associated outcomes of postoperative delirium using multiple logistic models while minimising the limitation of a small number of events of postoperative delirium.

Statistical analyses

The incidence of postoperative delirium following TJA using the standard formula—the number of patients diagnosed to have postoperative delirium divided by the total number of patients in the study, and the result expressed as a percentage.

Potential risk factors of postoperative delirium will also be identified by comparing the perioperative data recorded between the patients with and without postoperative delirium. Data will first be summarised using descriptive statistics including mean, SD, median, range and frequency tables. Univariate analyses will then be used to identify the differences between the two groups. Data of continuous variables will be compared using the Student’s t-test (normally distributed data) or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (not normally distributed data). Data of categorical variables will be compared by Pearson’s Χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test.

The variables which are statistically significant or close to significant (P value <0.05 or <0.1) between the two groups of patients will then be selected for inclusion in a multivariate logistic regression model. This will determine the independent predictors of postoperative delirium. The final model will be determined by sensitivity analysis. The sensitivity analysis can help us to understand the contribution of each parameter to the model outputs, investigate which parameter will have the biggest influence and then refine the model to obtain the final model which is statistically and clinically meaningful. OR will be used to describe the correlation of them with postoperative delirium.

Postoperative outcomes which are associated with the incidence of postoperative delirium will also be examined by comparing patients with and without postoperative delirium. The postoperative POMS score, CoCI score, incidence of PONV, LOS, incidence of 30-day readmission and %DAOH will be similarly compared using Student’s t-test and Pearson’s Χ2 test as appropriate.

For the long-term postoperative outcomes, the median postoperative SF-36 for each domain, KSKS, KSFS, OKS, HHS and PMS scores applicable at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years and 5 years will be compared with the median preoperative baseline scores using the Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank test. The tests with a change greater than the minimally clinically important difference (MCID) will be identified. The MCID values for each test will be obtained from the pre-existing literature. These variables will then be analysed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to identify the predictors of the long-term postoperative test scores. All predictor variables will be incorporated into the multivariate ANCOVA model. Analyses will be performed separately for the various tests that demonstrated changes greater than MCID.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Singapore General Hospital Institutional Review Board (SGH IRB) (CIRB Ref: 2017/2467) and is registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov registry (Identified: NCT03260218). In the event of any important protocol modifications, all investigators, SGH IRB and trial participants will be notified.

The results of this study will be presented at international conferences and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal. The data collected will also be made available in a public data repository.

All eligible participants will be approached by the research assistant during their visit to the PEC. They will be given an explanation about the study, a patient information sheet and a consent form. They will then be given an ample time to consider if they would like to participate in the study. They will also be allowed to ask questions freely. If the participant expresses an interest to participate in the study, a written consent will be obtained. The consent forms are in English. However, participants from non-English-speaking backgrounds will be provided a translator. For illiterate participants, an accompanying family member will be approached to verify and witness the consent process.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HRA and SRT designed and conceptualised the study, prepared and revised the draft manuscript, approved the final manuscript for submission and were involved in statistical calculations. SJL, HRBAR, RHS, ES and EYS designed and conceptualised the study, revised the draft manuscript and approved the final manuscript for submission. HY designed and conceptualised the study, revised the draft manuscript, approved the final manuscript for submission and was involved in statistical calculations. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: Hairil Rizal Abdullah is supported by the Singhealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre Nurturing Clinician Scientists Scheme Award, (12/FY2017/P1/15-A29).

Disclaimer: Singhealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre has no role in the design of this study and will not have a role in the analysis and interpretation of the results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Singapore General Hospital Institutional Review Board (SGH IRB) (CIRB Ref: 2017/2467).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth Edition Arlington: VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott JE, Mathias JL, Kneebone AC. Incidence of delirium following total joint replacement in older adults: a meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2015;37:223–9. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudolph JL, Marcantonio ER. Review articles: postoperative delirium: acute change with long-term implications. Anesth Analg 2011;112:1202–11. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182147f6d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Rasmussen LS, et al. Independent vascular and cognitive risk factors for postoperative delirium. Am J Med 2007;120:807–13. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA 1994;271:134–9. 10.1001/jama.1994.03510260066030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, et al. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;304:443 10.1001/jama.2010.1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovald ST, Ong KL, Malkani AL, et al. Complications, mortality, and costs for outpatient and short-stay total knee arthroplasty patients in comparison to standard-stay patients. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:510–5. 10.1016/j.arth.2013.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:780 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raats JW, van Eijsden WA, Crolla RM, et al. Risk Factors and Outcomes for Postoperative Delirium after Major Surgery in Elderly Patients. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136071 10.1371/journal.pone.0136071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, et al. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:204–12. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00047.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singapore General Hospital. Quick facts. 2017. https://www.sgh.com.sg/about-us/more-about-sgh/pages/quickfacts.aspx (accessed 14 Jul 2017).

- 12.Singapore General Hospital. Adult reconstructive service. 2014. https://www.sgh.com.sg/departments/ortho/services/pages/adult-reconstructive-service.aspx (accessed 14 Jul 2017).

- 13.Inouye SK, et al. Clarifying Confusion: The Confusion Assessment Method. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:941 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzman R, Zhang MY, Ouang-Ya-Qu, et al. A Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination; impact of illiteracy in a Shanghai dementia survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:971–8. 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90034-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahadevan S, Lim PP, Tan NJ, et al. Diagnostic performance of two mental status tests in the older chinese: influence of education and age on cut-off values. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15:234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng TP, Niti M, Chiam PC, et al. Ethnic and educational differences in cognitive test performance on mini-mental state examination in Asians. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;15:130–9. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000235710.17450.9a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inouye SK. Confusion Assessment Method. © 1988, 2003, Hospital Elder Life Program. Ann Intern Med 1988;1990:941–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pye A, Charalambous AP, Leroi I, et al. Screening tools for the identification of dementia for adults with age-related acquired hearing or vision impairment: a scoping review. Int Psychogeriatrics 2017:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Volland G, et al. Reliability and validity of grip and pinch strength evaluations. J Hand Surg Am 1984;9:222–6. 10.1016/S0363-5023(84)80146-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ong HL, Abdin E, Chua BY, et al. Hand-grip strength among older adults in Singapore: a comparison with international norms and associative factors. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:176 10.1186/s12877-017-0565-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daabiss M. American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification. Indian J Anaesth 2011;55:111–5. 10.4103/0019-5049.79879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–51. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasad KT, Sehgal IS, Agarwal R, et al. Assessing the likelihood of obstructive sleep apnea: a comparison of nine screening questionnaires. Sleep Breath 2017;21:909–17. 10.1007/s11325-017-1495-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett-Guerrero E, Welsby I, Dunn TJ, et al. The use of a postoperative morbidity survey to evaluate patients with prolonged hospitalization after routine, moderate-risk, elective surgery. Anesth Analg 1999;89:514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grocott MP, Browne JP, Van der Meulen J, et al. The Postoperative Morbidity Survey was validated and used to describe morbidity after major surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:919–28. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J, et al. The Comprehensive Complication Index. Ann Surg 2013;258:1–7. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318296c732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, et al. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;248:13–14. 10.1097/00003086-198911000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scuderi GR, Bourne RB, Noble PC, et al. The new Knee Society Knee Scoring System. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:3–19. 10.1007/s11999-011-2135-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, et al. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998;80:63–9. 10.1302/0301-620X.80B1.7859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garratt AM, Brealey S, Gillespie WJ; DAMASK Trial Team. Patient-assessed health instruments for the knee: a structured review. Rheumatology 2004;43:1414–23. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Hove RP, Brohet RM, van Royen BJ, et al. High correlation of the Oxford Knee Score with postoperative pain, but not with performance-based functioning. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 2016;24:3369–75. 10.1007/s00167-015-3585-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1969;51:737–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Söderman P, Malchau H. Is the Harris hip score system useful to study the outcome of total hip replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;384:189–97. 10.1097/00003086-200103000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker MJ, Palmer CR. A new mobility score for predicting mortality after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993;75:797–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kristensen MT, Bandholm T, Foss NB, et al. High inter-tester reliability of the new mobility score in patients with hip fracture. J Rehabil Med 2008;40:589–91. 10.2340/16501977-0217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kristensen MT, Foss NB, Ekdahl C, et al. Prefracture functional level evaluated by the New Mobility Score predicts in-hospital outcome after hip fracture surgery. Acta Orthop 2010;81:296–302. 10.3109/17453674.2010.487240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ariti CA, Cleland JG, Pocock SJ, et al. Days alive and out of hospital and the patient journey in patients with heart failure: Insights from the candesartan in heart failure: assessment of reduction in mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Am Heart J 2011;162:900–6. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019426supp001.pdf (232.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019426supp002.pdf (284.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019426supp003.pdf (435.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019426supp004.pdf (334.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019426supp005.pdf (556.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019426supp006.pdf (436.2KB, pdf)