Abstract

Objectives

To explore the views of maternity service users and professionals towards obstetric consultant presence 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Design

Semistructured interviews conducted face to face with maternity service users and professionals in March and April 2016. All responses were analysed together (ie, both service users’ and professionals’ responses) using an inductive thematic analysis.

Setting

A large tertiary maternity unit in the North West of England that has implemented 24/7 obstetric consultant presence.

Participants

Antenatal and postnatal inpatient service users (n=10), midwives, obstetrics and gynaecology specialty trainees and consultant obstetricians (n=10).

Results

Five themes were developed: (1) ‘Just an extra pair of hands?’ (the consultant’s role), (2) the context, (3) the team, (4) training and (5) change for the consultant. Respondents acknowledged that obstetrics is an acute specialty, and consultants resolve intrapartum complications. However, variability in consultant experience and behaviour altered perception of its impact. Service users were generally positive towards 24/7 consultant presence but were not aware that it was not standard practice across the UK. Professionals were more pragmatic and discussed how the implementation of 24/7 working had affected their work, development of trainees and potential impacts on future consultants.

Conclusions

The findings raised several issues that should be considered by practitioners and policymakers when making decisions about the implementation of 24/7 consultant presence in other maternity units, including attributes of the consultants, the needs of maternity units, the team hierarchy, trainee development, consultants’ other duties and consultant absences.

Keywords: obstetrics, thematic analysis, Nhs, service users, midwives, consultants

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to qualitatively explore views towards 24/7 consultant presence in any specialty.

A diverse sample of service users was recruited in terms of occupation, (anticipated) mode of birth and antenatal and postnatal women.

All professionals were white females and therefore the views of males and professionals of other ethnicities were not captured in this study which may limit the transferability of findings.

The service users were sampled from a large tertiary unit, specialising in complex births, and therefore, the findings should be extrapolated to non-tertiary units with caution.

Introduction

In the UK maternity care for low-risk women is midwifery-led. Involvement of obstetricians occurs when a woman’s pregnancy and/or birth is deemed high-risk or intrapartum complications occur.1 In response to the burden of obstetric complications, rising birth rate and medicolegal claims, national organisations have recommended that obstetric consultant presence should be increased in UK National Health Service (NHS) maternity units.2–7 Recently, guidelines have shifted focus to extend consultant presence to 7 days a week.8 While recommendations imply that increased consultant presence in the maternity unit translates into safer labour and delivery outcomes, there is a lack of evidence to demonstrate that this is the case.9 10

A meta-analysis of six studies compared resident consultant presence to on-call consultant cover and found that the risk of instrumental delivery was 14% higher in the on-call group than the resident group.11 A larger meta-analysis of 15 studies comparing maternal and neonatal outcomes during increased consultant presence found that the likelihood of emergency caesarean section decreased and likelihood of normal vaginal delivery increased when hours of rostered consultant presence per week increased.12 However, studies that compared times during no consultant presence (eg, a registrar-led shift) versus a consultant-led shift or compared weekend consultant presence with weekday consultant presence showed no significant difference in outcome. Thus, something other than consultant presence impacts on obstetric outcomes, such as concomitant increase in midwifery staffing or strengthened cohesiveness of the team. Consultant presence 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (24/7 CP) may also affect service users (SUs) and staff in ways that cannot be detected using quantitative measurements of outcomes alone.

A recent commentary highlighted the need to investigate staff provision in maternity units through quantitative and qualitative approaches and recommended the exploration of patient and staff perceptions.13 As qualitative methodology offers flexibility and scope to capture the impact beyond quantitative measurements of obstetric outcome, this study aimed to (A) understand how SUs and professionals at this unit viewed 24/7 CP and (B) use these views to identify any issues around 24/7 CP on the maternity unit that could further improve SU and professionals’ experiences.

Methods

Setting

St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, UK, is a tertiary maternity unit delivering over 9000 babies per year. The maternity unit serves an ethnically and socially diverse population with a high-level of need. The population has high levels of deprivation and perinatal and child mortality. Maternity services in Manchester were reconfigured in 2012: two smaller adjacent units were closed and St Mary’s capacity increased. 24/7 CP was introduced in St Mary’s Hospital in September 2014.

Participants

SUs were included if they were 18 years or older and inpatients at St. Mary’s Hospital maternity unit after 28 weeks’ gestation or prior to discharge after giving birth, because consultants are involved in the care of antenatal as well as postnatal women. Women with limited ability to speak and understand English were excluded due to difficulties in obtaining informed consent and conducting interviews. Eligible professionals were over 18 years old and included midwives, obstetrics and gynaecology specialty trainees (ST1–ST7) and consultant obstetricians.

Procedure

Eligible SUs were identified by a member of the clinical team who had been briefed on the study eligibility criteria. Professionals were approached by email and during team handovers. Prior to the interview, participants were asked to provide written consent and demographic information. Interviews were conducted face to face by HER in a private office or by the woman’s bedside. Two semistructured interview schedules were developed: one for SUs and one for professionals (see online supplementary appendix 1 and 2) and were initially piloted with two SUs and two professionals. Both interview schedules were developed after careful consultation of the existing literature and through several research group discussions. Both interview schedules were amended after piloting to include clear explanations of what 24/7 CP is and specific prompts were added, which were informed by the pilot interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded and lasted 10–25 min. All interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim, and all transcripts were double checked for consistency. Pseudonyms were used, and identifiable information was removed.

Analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was used and adopted a realist epistemology, which asserts truth is as it appears.14 Triangulation of findings by realist researchers demonstrates more reliability across the findings.14 All transcripts were analysed together following the step-by-step guide outlined in Braun and Clarke.15

Reflexivity and methodological quality

Reflexivity sees the researcher consider their position and influence on the research, and it can be used to promote rigour.16 HER, a research assistant, is a female with no experience of childbirth but experience of interviewing mothers and fathers during the postnatal period. HER had no prior relationship with the participants prior to the study commencement. AW, a senior lecturer, clinical psychologist and mother, has extensive experience of and expertise in perinatal mental health and qualitative research. SV is a consultant obstetrician (since 2001) and a mother. AEPH is an academic consultant obstetrician with over 10 years of working at this unit and a father. All authors met regularly to discuss recruitment, the interview schedules, data collection and theme development.

Theoretical and methodological memos were recorded throughout the research to record additional points of interest during the interviews and to record any decisions made by the research team.

Results

Sample

During March and April 2016 (~18 months after the introduction of 24/7 CP), we recruited a convenience sample of 10 SUs and 10 professionals, whereby data saturation was reached (see tables 1 and 2 for SUs’ and professionals’ demographics, respectively).

Table 1.

Service users’ chracteristics

| Antenatal | ||||||||||

| Pseudonym | Age (years) |

Ethnicity | Marital status | Occupation | Birth risk (low/moderate/high) | Gestation (weeks) | Anticipated mode of delivery | Number of other child(ren) | Age(s) of other child(ren) (years) | Previous mode(s) of delivery |

| Amelia | 22 | White | Cohabiting | Part-time student | High | 33 | NVD | 2 | 4/2 | NVD/NVD |

| Jessica | 27 | White | Married | Dental nurse | Moderate | 30 | ElCS | 1 | 4 | EmCS |

| Natasha | 29 | Black | Married | Care worker | High | 28 | NVD | 3 | 9/8/5 | NVD/NVD/NVD |

| Lindsey | 30 | White | Married | Legal Personal Assistant | High | 38 | ElCS | 0 | – | – |

| Claire | 31 | White | Cohabiting | Retail manager | Moderate | 39 | NVD | 0 | – | – |

| Postnatal | ||||||||||

| Pseudonym | Age (years) | Ethnicity | Marital status | Occupation | Birth risk (low/moderate/high) | Age of baby(ies) (days) |

Mode of delivery | Number of other child(ren) | Age(s) of other child(ren) (years) | Previous mode(s) of delivery |

| Helen | 39 | White | Married | Administrator | High | 3 | ElCS | 1 | 15 | EmCS |

| Sarah | 32 | White | Married | Nursing assistant | Low | 1 | NVD | 2 | 4/2 | NVD/NVD |

| Ava | 34 | Asian | Married | Solicitor | Low | 1 | Forceps | 0 | – | – |

| Ella | 27 | White | Cohabiting | Clerical officer | High | 5 | EmCS | 0 | – | – |

| Katie | 35 | White | Cohabiting | Caterer | High | 6 | NVD | 1 | 17 | NVD |

ElCS, elective caesarean section; EmCS, emergency caesarean section; NVD, normal vaginal delivery.

Table 2.

Professionals’ characteristics

| Pseudonym | Gender | Age (years) | Ethnicity | Marital status | Post | Time in post (years) |

| Karen | Female | 45 | White | Married | Consultant | 8.5 |

| Carla | Female | 35 | White | Married | Consultant | 0.75 |

| Annie | Female | 42 | White | Married | Consultant | 4.5 |

| Cathy | Female | 45 | White | Cohabiting | Consultant | 7.5 |

| Jocelyn | Female | 31 | White | Cohabiting | ST1 | 0.5* |

| Imogen | Female | 33 | White | Cohabiting | ST6 | 1.5 |

| Erin | Female | 32 | White | Married | ST4 | 3 |

| Olivia | Female | 28 | White | Single | Midwife | 2 |

| Milly | Female | 24 | White | Cohabiting | Midwife | 3 |

| Beth | Female | 54 | White | Married | Midwife | 17 |

*Not employed at St. Mary’s prior to the implementation of 24/7 consultant presence.

ST, specialty trainee.

Findings

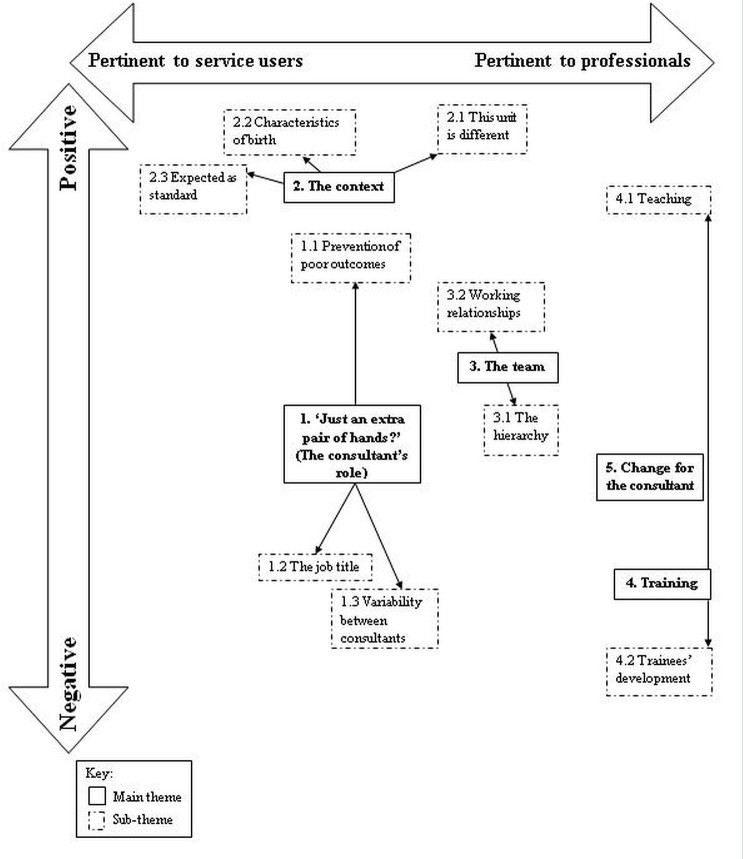

Five broad themes were developed with 10 corresponding subthemes: (1) ‘Just an extra pair of hands?’ (the consultant’s role), (2) the context, (3) the team, (4) training and (5) change for the consultant (see figure 1 for thematic diagram). Antenatal and postnatal SUs, trainees, midwives and consultants provided data for themes 1, 2 and 3. Trainees, midwives and consultants contributed to theme 4, and theme 5 only consisted of consultants’ contributions. Diversity is reported to ensure openness regarding disconfirmatory findings. Quotations are presented to facilitate judgements of trustworthiness.

Figure 1.

Thematic diagram of service users’ and professionals’ views of 24/7 obstetric consultant presence.

Theme 1: ‘Just an extra pair of hands?’ (the consultant’s role)

Many SUs and professionals mentioned consultants as supernumerary. The theme’s title was taken from their descriptions of consultant input as ‘an extra person’ (Helen, postnatal) and ‘it’s more pairs of hands than necessarily needing the seniority’ (Karen, consultant). The theme was equally salient for both SUs and professionals and outlines how they viewed the consultant’s role both positively and negatively with regards to 24/7 CP. This theme was divided into three subthemes: prevention of poor outcomes, the job title and variability between consultants.

Prevention of poor outcomes

This subtheme consisted of mostly positive views towards 24/7 CP. SUs often perceived consultants to be the individuals who made decisions and could rectify intrapartum problems quickly; speed and decision making were mentioned in the majority of SUs’ responses.

…you would want consultants to be there and making all the major decisions. (Sarah, postnatal)

A consultant can just make that decision there and then… whereas the doctors have got to wait then go and speak to their consultant. (Ella, postnatal)

Very few SUs and professionals provided an experience when a consultant had been required to prevent a poor outcome. However, both spoke about the need to have a consultant prospectively, that is, the consultant’s ability to prevent poor outcomes. Specifically, trainees were fearful of negative outcomes when a consultant was not available to support them quickly.

If I’m a trainee at a district hospital and I’m the only one at night time and I have to wait for my consultant to come on site… you’re in a position where something could potentially really go wrong and that support might not be there. (Jocelyn, ST1)

However, consultants often cited the limited evidence to support increased consultant presence and did not comment on whether they felt it had a positive impact on patient outcomes.

The main problem is there isn’t any evidence that it improves patient care. (Cathy, consultant)

The job title

Responses were mixed with regards to whether consultant presence on a maternity unit was essential. Some professionals felt that a consultant should be present 24/7 in the same way as other members of the team were (eg, midwives). The identity as a consultant-led unit was used to strengthen the argument for continuous consultant presence.

[I]n a consultant-led, high-risk unit you need to have a consultant there 24/7, you wouldn’t have a midwifery-led unit without midwives overnight. (Milly, midwife)

However, trainees and consultants felt that SUs did not understand the staff hierarchy, and therefore SUs did not differentiate between consultant care, trainee care or midwifery care.

I think the reality is for most women in labour, they’re pretty happy to see a doctor. Most people don’t actually understand the difference between a junior reg[istrar] and a senior reg[istrar]. Quite frankly, as a woman in obstetrics, they just think you’re the midwife anyway, so it doesn’t really matter. (Erin, ST4)

Thus, from an SU’s view, competent medical care provided by any labour ward professional was more important than the job title of the provider. Furthermore, some SUs voiced negative views towards consultants’ continual presence on the unit, expressing that having rapport with other professionals and very limited contact with consultants negated the need for 24/7 CP.

If you’ve got a good rapport with the midwife, I don’t see why the consultants necessarily need to be present all the time. (Lindsey, antenatal)

I don’t think it makes much difference because you don’t really get to see them. (Katie, postnatal)

Variability between consultants

Some SUs expressed that 24/7 CP was a positive change, but this was dependent on individual consultants.

It is a good idea depending on the consultants. (Katie, postnatal)

Professionals, particularly consultants, stated that variable behaviour and abilities of consultants could compromise the impact of 24/7 CP.

I do think there are some of the consultants who still go to bed… who maybe go to bed inappropriately and there are some incidents coming through where, actually, that consultant should have been present and they’re not. (Karen, consultant)

The implementation of 24/7 CP required that several new consultant posts were filled. One consultant strongly expressed concerns that rapid filling of these posts had resulted in the appointment of consultants with varying competence, inferring that consultants’ skills and attributes should be considered alongside their presence on the unit.

I think the filling of 10 posts all at the same time, which we didn’t achieve, but even trying to do that all at the same time meant that we’ve appointed some people who, if we’d only been appointing one or two people, wouldn’t have got appointed. (Cathy, consultant)

Theme 2: the context

Participants often compared the area of obstetrics to other areas of medicine and/or the unit to other maternity units in order to highlight the reasons why 24/7 CP was a positive change. This theme, pertinent for both SUs and professionals, encapsulates the contextual factors that surround birthing and the maternity unit. It was divided into three subthemes: this unit is different, characteristics of birth and expected as standard.

This unit is different

All SUs cited the unit’s reputation and the perceived expertise of professionals as a reason for choosing to give birth at St. Mary’s, often expressing that they felt safer than at other maternity units. However, as most SUs were not aware that the unit has been providing 24/7 CP or that this cover is not routinely implemented nationwide, they did not cite this as a reason for perceiving the unit as different to others.

They tried to move us to [another hospital], but I know that this has got a really good reputation for the maternity, so I opted to stay here. (Lindsey, antenatal)

I thought it was the best hospital, and with having twins, with all the top doctors. (Katie, postnatal)

The varied, high-risk and complex patient population cared for by the unit was cited as a feature which made St. Mary’s different to other units and was the main reason given for the necessity of 24/7 CP by professionals. Some believed that complexity and risk would only increase in the future.

The kind of things that we get here are not anywhere near as simple as other units. Here we get life threatening haemorrhages at four to eight litres, in another smaller unit like the tiny one I was working in before I came here, they would consider 500mls, which here is a normal blood loss, they consider that serious. (Imogen, ST6)

We are such a high-risk unit, you need to have that consultant input constantly. (Beth, Midwife)

Characteristics of birth

The varied and unpredictable nature of labour and birthing was also deemed an important reason for 24/7 CP, although more salient for SUs.

[E]very woman is different, every baby is different and every situation is different so here it is very important to have a consultant with that. (Jessica, antenatal)

The potential for ‘things to go wrong quickly’ was expressed by both professionals and SUs as a unique characteristic of obstetrics as opposed to other specialities. Interestingly, the issue of unpredictability during birth was focused on more by postnatal SUs, perhaps because they were able to consider and articulate the risks of birth.

…just in case things go wrong, things can quite quickly go wrong. (Helen, postnatal)

Professionals held similar views that complications could arise quickly, obstetrics is an area of medicine that is truly 24/7 and indicated that consultant presence was needed due to these characteristics.

I think it can only ever be a good thing, especially if you’re in obstetrics which is so quick in how things can so suddenly deteriorate. (Erin, ST4)

Expected as standard

It came as a surprise to all SUs that not all maternity units have 24/7 CP because they had expected that it was standard practice.

I wasn’t very aware of it (24/7 CP) at all actually. (Ava, postnatal)

I can’t even believe that I didn’t know that they didn’t have a consultant on 24/7 everywhere else. (Ella, postnatal)

Hence, they expressed appreciation for St. Mary’s but also overwhelmingly endorsed that it should be a requirement for all maternity units.

So we are the lucky ones… I think it should be spread to every hospital in England. It is not only Manchester or St. Mary’s that people would need consultants. (Natasha, antenatal)

Although this subtheme was more pertinent to SUs, one professional also highlighted SUs’ expectation of continual consultant presence.

The general public expect to be seen by a consultant day or night, and I think it’s the way that most acute specialities are going to go. (Carla, consultant)

Theme 3: the team

The impact of 24/7 CP on the workings of the multidisciplinary maternity team was an important issue raised. Although a more pronounced theme for professionals, particularly midwives, some SUs discussed multidisciplinary relationships. The theme, divided into the subthemes of the hierarchy and working relationships, outlines the mixed views towards the relationships between consultants and other professionals and the consultants’ position within the team.

The hierarchy

The leadership provided by 24/7 CP due to the consultant’s position within the team hierarchy was viewed favourably. SUs expressed that the consultants’ authority was a support for other professionals

I think it’s support for the midwives as well because you could have a really inexperienced midwife that is put in a position and if they don’t have that authority to go to and ask that question or make that decision on the ward, then it’s not really fair on them. (Claire, antenatal)

Similarly, professionals reported that consultants directed the team and took responsibility; it was suggested this started to occur more when 24/7 CP was implemented. Thus, strong leadership was valued by other professionals in this team.

Before we kind of felt a bit like we were just left to our own devices, no one wanted to take charge or responsibility for the postnatal ward… we needed a bit of control from consultants in order to help us manage it more effectively. (Olivia, midwife)

However, one consultant reported that midwives were less likely to seek the support of trainees, favouring the authority of consultants, which could disadvantage trainees’ professional development.

One negative that I could potentially see from it is that the midwives might tend to, not ignore, but not go to the junior doctors if they know that there is someone senior there that’s able to make a definite decision. (Carla, consultant)

Working relationships

In contrast to the desire for a consultant leadership role, some participants expressed negative views regarding working relationships between consultants and midwives. Some SUs felt that midwives were not able to voice their opinion when clinical decisions were being made, which was particularly salient for SUs who had a negative experience of consultant contact.

I just don’t like the fact that the midwives aren’t able to say anything. It’s up to the consultant. (Lindsey, antenatal)

Although this was not discussed as a perceived consequence of the change to 24/7 CP, it was suggested that this strain on working relationships occurred more frequently.

There’s a bit more of, how shall I say it, butting of heads if you like from certain people. They just want it done their way because they’re in charge. (Beth, midwife)

However, some midwives felt that the similar working hours had a positive impact, made the team more cohesive and reduced the power imbalance between the two professional groups.

I guess it breaks down barriers between us and them, because if they’re doing the same terrible shifts then you know that they’re not just swanning in as and when they feel like it. They’re doing the grind, they’re doing the nights and weekends… you feel that you’re all in it together, rather than them kind of lording it over you when they come in. (Milly, midwife)

Theme 4: training

Although views were mixed, all professionals spoke about how the training of midwives and trainees had been affected by 24/7 CP. The theme, pertinent to trainees and consultants, was divided into two subthemes: teaching and trainees’ development.

Teaching

Two factors for improving training were identified: time and consultant engagement. Trainees and consultants felt there were more opportunities for out-of-hours training and midwives also reported that they learnt more from consultants than trainees due to consultants’ knowledge and time to train others.

[Y]ou get better training overall, because I think you have access to supervision 24/7, there’s more availability to get supervised in more procedures out of hours. (Erin, ST4)

I have a bit more knowledge than them [junior doctors] on certain things. So I don’t feel I learn as much from junior doctors whereas I learn more from consultants who sometimes have a bit more time or a bit more knowledge about certain things. (Olivia, midwife)

However, the role of consultant engagement was highlighted by trainees and consultants: although consultants were on the unit out of hours, this could actually reduce consultant engagement in training others.

Even though you have the so-called presence of a consultant it also depends on how much they’re involved with or their engagement with trainees. (Jocelyn, ST1)

One consultant stated that consultants were more inclined to carry out procedures themselves out of hours than train others in order to save time.

They should get better training in the middle of the night on delivery suite because we are there. Equally there can be more of a temptation to just get on and do it because it’s three in the morning and if you do it yourself, you’re back doing something else in 20 min rather than 40 min. (Cathy, consultant)

Trainees’ development

Although professionals held some favourable views towards the impact of 24/7 CP on training opportunities, they expressed negativity when discussing the development of trainees as consultants of the future. Both trainees and consultants felt 24/7 CP could reduce trainees’ autonomy, confidence, clinical judgement and their ability to cope with stress.

I think one problem with 24/7 consultant presence is some of our junior registrars, there are one or two who are relaxed all the time from an educational putting-themselves forward perspective… I think actually you can then get away with a hell of a lot because they constantly step back… the more senior they get, the more the stress increases. If they don’t learn that and learn to cope with that early on, they’re never going to manage as a consultant. (Imogen, ST6)

I know some of my colleagues, when I was a registrar, felt that the presence of a consultant there could be quite interfering and perhaps they wouldn’t be able to use their own clinical judgement and make independent decisions. (Carla, consultant)

Participants spoke of how the presence of a more senior clinician impeded trainees’ ability to develop autonomy as practicing doctors, which is an important issue to be acknowledged by other maternity units and specialties considering implementing 24/7 CP.

If individuals are never left to make decision on their own, they never learn that autonomy to be able to make decisions. I think that’s one issue that we will find moving forward, the consultants of the future will be much less experienced. (Annie, consultant)

Theme 5: change for the consultant

Consultants spoke about how their lives had changed as a result of 24/7 CP, both in and out of the unit. This theme was one of the main focal points of consultants’ responses and encapsulates the issues that have and will affect consultants’ lives. Responses were more anecdotal for this theme and consultants drew on their positive and negative experiences before and after the implementation.

Many consultants expressed concerns regarding the competency of trainees under trainees’ development, but this issue was also raised in relation to consultant workload. Consultants, who felt that trainees’ capabilities had reduced, also felt that consultants were now required to do lower grade work to fill the skills gap of the trainees.

Junior doctors are becoming less and less competent at the sort of things that I might have been competent at as a senior registrar and so more and more you find yourself needing to do things that as a senior registrar or a registrar I would have dealt with without bothering a consultant. (Annie, consultant)

Change to the length of consultants’ shifts was also deemed a consequence of the implementation. Prior to 24/7 CP, consultants could work their rostered shift in the hospital then stay on-call from home (with the possibility of being called to the hospital). Hence, consultants could have worked for 24–48 hours whereas, since 24/7 CP, consultants work set shifts on the unit of 12.5 hours. This consequence was viewed positively because of the certainty that consultants could rest after a shift.

I don’t care how busy I am, because the most I’m normally going to be in is 13 hours. I don’t have that nagging feeling all the time - ‘am I going to have to try to keep this pace for 24 hours?’. (Karen, consultant)

Some consultants reported that 24/7 CP had had a negative impact on consultants’ professional development opportunities. The issue of balancing off-ward duties, such as meetings, with wards shifts was difficult, especially when working on the night-rota and because NHS management operate in office hours.

It makes work much more difficult because the day before and the day after night shift, you’re technically not in work meetings even though I think I’m reasonably good at planning… The Trust […] is terrible at giving you a week’s notice - ‘we’ve changed that meeting to that date’. Then if it’s the day after your night on call you either don’t go or you go when you’re supposed to be in recovery time. (Cathy, consultant)

Furthermore, issues for workers such as management of absences, and the impact they have on the labour ward team, were also highlighted as an area that required improvement when looking ahead.

I think one of the big problems with it is that we didn’t quite anticipate how you manage sick leave and short-term absences, which I don’t think have been properly sorted out. (Annie, consultant)

Discussion

Main findings

Five themes and 10 subthemes were developed. Both SUs and professionals acknowledged that consultants resolved intrapartum complications in an acute specialty in which complications arise quickly, although the effect was dependent on individual consultants’ skills and behaviour. SUs responses were generally positive towards the implementation, and they were surprised when made aware that 24/7 CP was not standard practice across the UK. Professionals’ responses were more pragmatic and included how 24/7 CP had affected their own work, development of trainees and the impact on the consultants of the future.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to qualitatively explore views towards 24/7 CP in any specialty and addresses Prior et al’s13 call for research to explore perceptions in relation to staff provision in maternity units. Furthermore, a diverse sample of SUs was recruited in terms of ethnicity, (anticipated) mode of birth and antenatal and postnatal women. However, all professionals were white females, and therefore, the views of males and professionals of other ethnicities were not captured in this study. This study also focused on interviewing midwives and obstetricians because they were primarily affected by the change to 24/7 CP. This approach may have resulted in data saturation being reached prematurely and may limit the transferability of findings. However, the gender mix reflects the female predominance as 79% of trainees are women,17 and midwifery is overwhelmingly female (in 2001 the midwifery workforce in England and Wales was 99% female and 1% male).18 However, future work should consider sampling a greater range of participants, both in terms of gender and ethnicity, and also members of different professional groups (eg, anaesthetists, neonatologists and managers), because participants from these groups may hold different views about 24/7 CP.

Furthermore, the SUs were all inpatients at St. Mary’s which suggests they had chosen to give birth in a hospital or were required to receive hospital care; this may result in a participation bias. Selection bias was limited as the initial approach about the study was made by the clinical team, independent of the researchers. However, some women in high-income countries are choosing to give birth away from the labour ward setting.19 Although, these individuals may not be directly affected by the move to 24/7 CP, qualitative researchers should approach such individuals in order to obtain more varied views towards consultant presence. Finally, St. Mary’s is a large tertiary unit, specialising in complex births and admits women from a large geographical area. Therefore, these findings should be extrapolated to non-tertiary units with caution.

Interpretation

Participants spoke of consultants’ ability to rectify intrapartum problems and make decisions quickly, suggesting that an increase in consultant presence would improve patient outcomes. However, the impact of increased consultant presence on outcomes is not fully understood,9–12 and this was highlighted by consultants. Participants also believed that SUs were happy to be seen by any competent member of staff, not just a consultant. This view is disputed in the surgical literature, which advocates that the consultant role is a ‘quality kite mark’ and reduces a patient’s concern about whether they are receiving the best quality care as well as worrying about their illness.20 However, maternity services in the UK are organised differently to other specialities, and a normal birth is not a medical procedure. Most women (57%) report just seeing a midwife during pregnancy and birth,21 and consultant intervention is not deemed a necessity in all births. Therefore, the consultant job title alone was not reason enough to implement 24/7 CP. Furthermore, the variability of consultants’ behaviour and attributes was seen as an issue that could compromise the impact of 24/7 CP. Attitudes and behaviours of caregivers have been found to influence women’s birth experiences more than pain relief and intrapartum interventions.22

As a large, tertiary maternity unit, St. Mary’s Hospital cares for a high-risk, complex population. Increasing case complexity is cited as one of the drivers for increasing obstetric consultant presence.23 However, this rationale is not fully applicable to smaller non-tertiary units. Participants noted the acute and unpredictable nature of complications in pregnancy and birth. Women were aware that emergencies can happen during birth as described in Larkin et al24 mixed methods study, which found women preferred not to have a consultant present during the birth but appreciated their presence during an emergency. To attend in such circumstances requires 24/7 CP, and this study found that SUs expected 24/7 CP as standard across all maternity units. As 80% of women were not aware of the four possible places to give birth (home, free-standing midwifery unit, alongside midwifery unit and consultant-led unit),21 the reason all SU respondents felt 24/7 CP should be standard may be due to an inaccurate perception that all maternity units are consultant-led.

Although participants highlighted that 24/7 CP could strain working relationships, the benefits of consultants’ leadership at the top of the hierarchy for the team was highlighted. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists states ‘the consultant’s role starts with demonstrating leadership: teaching and supporting trainees, midwives and nurses at all times’.6 However, midwives describe finding it difficult to facilitate normal births in an obstetric-led unit due to the obstetrician’s powerful position at the top of the hierarchy and dominant decision making.25 This raises the question of whether more detailed guidance on how consultants should support other professionals is needed to ensure a more cohesive labour ward team within a 24/7 CP model.

Trainees and consultants highlighted that 24/7 CP should result in more training opportunities out of hours. A systematic review of several specialities found enhanced supervision of trainees had a positive impact on patient-related and education-related outcomes.26 Despite this, respondents identified that in practice this increased supervision could also have a negative impact on trainee development, an issue also identified in a debate against 24/7 CP on the labour ward.27 A more in-depth analysis of confidence, clinical judgement and obstetric ability of trainees trained in hospitals of varying levels of consultant presence should be undertaken to shed light on this important issue for the future.

Consultants were positive towards the predictability of shift duration and appreciated uninterrupted rest when at home. However, they also felt they were carrying out more low-grade work, struggled to balance day-time duties when working night shifts and that absences were not managed adequately. These negative issues highlight the importance of thorough preparation prior to implementing a change to consultant working and future consultations with staff offer a direction to resolve these issues.

Conclusion

This is the first qualitative study to understand how maternity SUs and professionals view 24/7 CP. The findings raised several major issues that should be considered by practitioners and policymakers when deciding whether to implement 24/7 CP in maternity units across the UK. These issues were the attributes of the consultants, necessity on non-tertiary units, the team hierarchy, trainee development, consultants’ other duties and consultant absences. This study paves the way for more detailed research into each of these issues. Finally, other units that introduce 24/7 CP should consider further evaluation of 24/7 working to further improve maternity services.

bmjopen-2017-019977supp001.pdf (189.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019977supp002.pdf (200.1KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Charity for funding the writing of this manuscript and its Online Open publication. Additionally, we would like to thank all of the service users and professionals at St. Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, who participated and for their openness and honesty during interviews.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study concept and design. HER conducted all interviews. HER, AW and AEPH contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. HER developed the first draft of the manuscript, and AW, SV and AEPH revised all manuscript drafts and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Charity.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ‘South Central – Hampshire A’ Research Ethics Committee on 7 January 2016 (15/SC/0774) and the Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development department on 3 February 2016 (R04201).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available from a repository. Anonymised transcripts are available on request.

References

- 1.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, et al. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;9:CD004667 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Healthcare Commission. Towards better births: a review of maternity services in England. London: Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health Service Litigation Authority. Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts. Maternity. Clinical Risk Management Standards. London: National Health Service Litigation Authority, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.. The future role of the consultant: a working party report. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal College of Midwives, Royal College of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Safer childbirth: minimum standards for the organisation and delivery of care in labour. London: RCOG Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Responsibility of consultant on-call. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Labour ward solutions. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2010.. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Providing quality care for women: obstetrics and gynaecology workforce. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight HE, van der Meulen JH, Gurol-Urganci I, et al. Birth "Out-of-Hours": an evaluation of obstetric Practice and outcome according to the presence of senior obstetricians on the labour ward. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002000 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis EA, Barr C, Thomas K. The mode of delivery in women taken to theatre at full dilatation: does consultant presence make a difference? J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;31:229–31. 10.3109/01443615.2011.553692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson J, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. Resident consultant obstetrician presence on the labour ward versus other models of consultant cover: a systematic review of intrapartum outcomes. BJOG 2017;124:1311–20. 10.1111/1471-0528.14527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid HE, Hayes D, Wittkowski A, et al. The effect of senior obstetric presence on maternal and neonatal outcomes in UK NHS maternity units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2017;124:1321–30. 10.1111/1471-0528.14649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prior M, Draycott T, Burden C. Resident consultant cover may become part of 21st century maternity care, but it is not a panacea. BJOG 2017;124:1332 10.1111/1471-0528.14686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madill A, Jordan A, Shirley C. Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. Br J Psychol 2000;91:1–20. 10.1348/000712600161646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baillie L. Promoting and evaluating scientific rigour in qualitative research. Nurs Stand 2015;29:36–42. 10.7748/ns.29.46.36.e8830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.General Medical Council. The state of medical education and practice in the UK. London: General Medical Council, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yar M, Dix D, Bajekal M. Socio-demographic characteristics of the healthcare workforce in England and Wales-- results from the 2001 Census. Health Stat Q 2006;32:44–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodnett ED, Downe S, Walsh D. Alternative versus conventional institutional settings for birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD000012 10.1002/14651858.CD000012.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bentley L, Church J. Should our health service be consultant-led or consultant-delivered? The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 2008;90:160–1. 10.1308/147363508X303584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Redshaw M, Heikkila K. Delivered with care: a national survey of women’s experience of maternity care 2010. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;3:CD003766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandall J, Horner C, Sadler E, et al. Staffing in maternity units: getting the right people in the right place at the right time. London: The King’s Fund, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larkin P, Begley CM, Devane D. Women’s preferences for childbirth experiences in the Republic of Ireland; a mixed methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:19 10.1186/s12884-016-1196-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keating A, Fleming VE. Midwives' experiences of facilitating normal birth in an obstetric-led unit: a feminist perspective. Midwifery 2009;25:518–27. 10.1016/j.midw.2007.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farnan JM, Petty LA, Georgitis E, et al. A systematic review: the effect of clinical supervision on patient and residency education outcomes. Acad Med 2012;87:428–42. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824822cc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roach V. 24-hour consultant labour ward cover should be mandatory in tertiary obstetric hospitals: AGAINST: 24-hour consultant presence doesn’t enhance training and supervision of trainees. BJOG 2016;123:1379 10.1111/1471-0528.13756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019977supp001.pdf (189.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019977supp002.pdf (200.1KB, pdf)