Abstract

Objectives

To explore the causes of the gender gap in antibiotic prescribing, and to determine whether women are more likely than men to receive an antibiotic prescription per consultation.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected electronic medical records from The Health Improvement Network (THIN).

Setting

English primary care.

Participants

Patients who consulted general practices registered with THIN between 2013 and 2015.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Total antibiotic prescribing was measured in children (<19 years), adults (19–64 years) and the elderly (65+ years). For 12 common conditions, the number of adult consultations was measured, and the relative risk (RR) of being prescribed antibiotics when consulting as female or with comorbidity was estimated.

Results

Among 4.57 million antibiotic prescriptions observed in the data, female patients received 67% more prescriptions than male patients, and 43% more when excluding antibiotics used to treat urinary tract infection (UTI). These gaps were more pronounced in adult women (99% more prescriptions than men; 69% more when excluding UTI) than in children (9%; 0%) or the elderly (67%; 38%). Among adults, women accounted for 64% of consultations (62% among patients with comorbidity), but were not substantially more likely than men to receive an antibiotic prescription when consulting with common conditions such as cough (RR 1.01; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.02), sore throat (RR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.01) and lower respiratory tract infection (RR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.01). Exceptions were skin conditions: women were less likely to be prescribed antibiotics when consulting with acne (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.69) or impetigo (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.88).

Conclusions

The gender gap in antibiotic prescribing can largely be explained by consultation behaviour. Although in most cases adult men and women are equally likely to be prescribed an antibiotic when consulting primary care, it is unclear whether or not they are equally indicated for antibiotic therapy.

Keywords: antibacterial agents, prescriptions, electronic health records, antibiotic prescribing, consultation, gender bias

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is one of the first to explore the underlying causes of the large gap in the number of antibiotics prescribed to men and women in primary care.

Findings are derived from a large, representative sample of primary care patients in England.

Extensive mapping of diagnostic codes to clinical conditions made it possible to analyse prescribing across a range of conditions and to account for comorbidity.

Identification of antibiotics that are used to treat urinary tract infection (UTI) but rarely other conditions in this setting (trimethoprim and nitrofurantoin) allowed for approximation of UTI prescribing despite incomplete diagnostic coding.

The data do not include indicators of antibiotic appropriateness, such as severity of illness, and so the clinical appropriateness of gender differences in prescribing could not be evaluated.

Introduction

Reducing the unnecessary use of antibiotics is as an essential means of mitigating the emergence of antimicrobial resistance and its associated costs,1 2 but prescribing reductions are not without risk. The causes and magnitudes of prescribing vary substantially between practices and prescribers,3–5 and sweeping, uncalibrated interventions could jeopardise some patients while failing to prevent unnecessary prescribing in others. In order to safely and effectively reduce antibiotic use, it is imperative to understand how and to whom antibiotics are prescribed.

Gender is a key determinant of antibiotic prescribing. A recent meta-analysis across primary care in nine high-income countries found that women received more antibiotics than men in all age groups except those >75, with women aged 16–54 receiving 36%–40% more antibiotics than men of the same age.6 Similarly, across English and Welsh primary care, the rate of antibiotic prescribing has been found to be 40% higher in female than in male patients.7 Although the latter figure dates from 1996, gender disparities in England have more recently been observed in out-of-hours and paediatric care, with women and girls receiving more antibiotic prescriptions than men and boys.8 9

There are several proposed explanations for this gender gap. First, some infectious diseases affect men and women differently. In particular, urinary tract infection (UTI) is more common in adult women than in men and accounts for over 20% of antibiotic prescriptions in English primary care.10 11 However, respiratory tract infections (RTI) account for more than twice as many prescriptions as UTI,11 and women are not more susceptible to these conditions than men,12–14 although gender differences in comorbidity may underlie some variation in prescribing. Second, as in many countries,15 16 women in the UK consult their general practitioner (GP) more often than men,17–19 and consultation rate is linked to antibiotic prescribing.5 Previous studies of relatively small samples of patients with RTI have found that gender differences in consultation are proportionate to differences in prescribing,20 21 but it is unclear whether or not this is true across a greater range of conditions, when taking comorbidity into account, and using a more recent, nationally representative sample of patients. Finally, other social and behavioural factors may also play a role. For example, men and women communicate differently with health professionals, and prescribers may have biases that affect their willingness to prescribe antibiotics during consultations with women versus men.22 23 Ultimately, it remains unknown to what extent these and other factors combine to explain the gender gap in antibiotic prescribing.6

Here, gender differences in antibiotic prescribing were analysed using a large, representative sample of primary care patients in England. Antibiotic prescribing in male and female children, adults and the elderly was compared at the population level. The influence of gender on prescribing was assessed by controlling for consultation and comorbidity, and calculating the proportions of adult men and women who received systemic antibiotic prescriptions when presenting to primary care with a suite of common conditions. These prescribing proportions facilitate a deeper understanding of the causes of the gender gap in antibiotic prescribing, and may inform prescribing intervention design.

Methods

This study used data from English general practices registered with The Health Improvement Network (THIN), a UK-based primary care electronic medical record database. Practices were included that provided data for at least one full calendar year between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2015; there were 349 such practices in 2013, 285 in 2014, and 191 in 2015. Anonymised patient data were extracted from these practices that met acceptable standards for research data collection. All systemic antibiotic prescriptions (antibiotics from British National Formulary Chapter 5.1,24 excluding antituberculosis and antileprosy drugs) recorded in THIN were analysed by patient gender and age. Patient age at the time of consultation was used to classify patients as children (aged 0–18 years), adults (19–64 years) and the elderly (65+ years). Due to a very large sample size, proportions of antibiotics prescribed to male versus female patients are reported without CIs.

Read Codes (the diagnostic codes used in THIN) were analysed to quantify the number of male and female consultations for acute presentations of 12 common conditions that are treated with antibiotics to varying degrees: acne, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cough, gastroenteritis, impetigo, influenza-like illness (ILI), lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), otitis media, sinusitis, sore throat and upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). A vast number of Read Codes are used in THIN, and the methods used to assign specific Read Codes to different conditions and to link Read Codes to acute antibiotic prescriptions are described elsewhere.11 The ratio of female to male consultations (F:M) was then calculated to quantify gender differences in consultation for each of these conditions.

In THIN, a large proportion of UTI consultations are poorly coded, particularly in patients consulting for UTI prophylaxis or chronic/recurrent UTI. However, between 2013 and 2015 in English primary care, the antibiotics used to prevent and treat the vast majority of UTIs—trimethoprim and nitrofurantoin—were rarely used for other conditions.11 25 Prescriptions of trimethoprim and nitrofurantoin were thus used as a proxy measure for prescribing for UTI.

Prescribing proportions were then calculated by dividing the total number of prescriptions for a given condition by the number of consultations for that condition. To account for patients who consulted more than once, robust SEs were used when calculating prescribing proportions. These data were also used to calculate the relative risk (RR) of being prescribed an antibiotic when consulting as female as opposed to male. In the main analysis, consultations were included if they occurred at a patient’s primary registered practice, but in a sensitivity analysis all patient consultations recorded in THIN were included. Patients with comorbidity were analysed separately from otherwise ‘healthy’ patients (ie, those without comorbidity) to minimise potential biases in consultation and prescribing due to gender differences in background health status. Further, the RR of being prescribed an antibiotic when consulting with comorbidity was also calculated for each condition and gender. Comorbidities were identified by the Read Codes that indicate qualification for the free seasonal influenza vaccination programme: asthma, chronic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, chronic neurological disease and immunosuppressive disease.26 Patients who received at least two prescriptions of systemic or inhaled corticosteroids or immunosuppressive drugs in the 365 days prior to their consultation were also included in this group, since these drugs indicate an increased risk of serious complications after (respiratory tract) infections.26

All data were analysed using STATA V.13.1 and R V.3.1.

Results

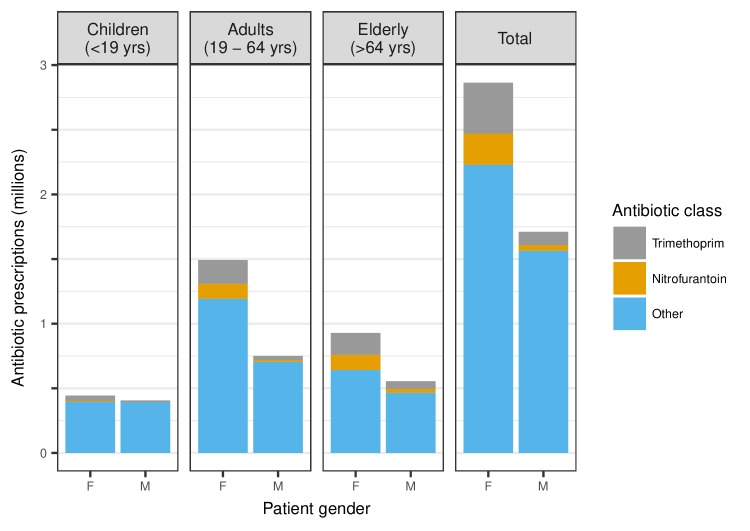

Of all antibiotic prescriptions observed in THIN between 2013 and 2015 (n=4 574 363), the majority (62.6%) were in female patients (figure 1). Adult women received approximately twice (99.0%) as many antibiotic prescriptions as adult men, whereas elderly women and girls received 67.4% and 9.2% more prescriptions, respectively, than elderly men and boys. Nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim accounted for 17.1% of all prescriptions, 81.3% of which were prescribed to female patients. The prescribing gender gap narrowed in all age groups when these antibiotics were removed, and became negligible in children (0.3%), but adult and elderly women still received, respectively, 69.2% and 37.7% more antibiotic prescriptions than adult and elderly men.

Figure 1.

All systemic antibiotic prescriptions recorded in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) between 2013 and 2015, stratified by gender and age group. Antibiotics used to treat urinary tract infection (UTI) (trimethoprim and nitrofurantoin) are identified separately from all other antibiotics.

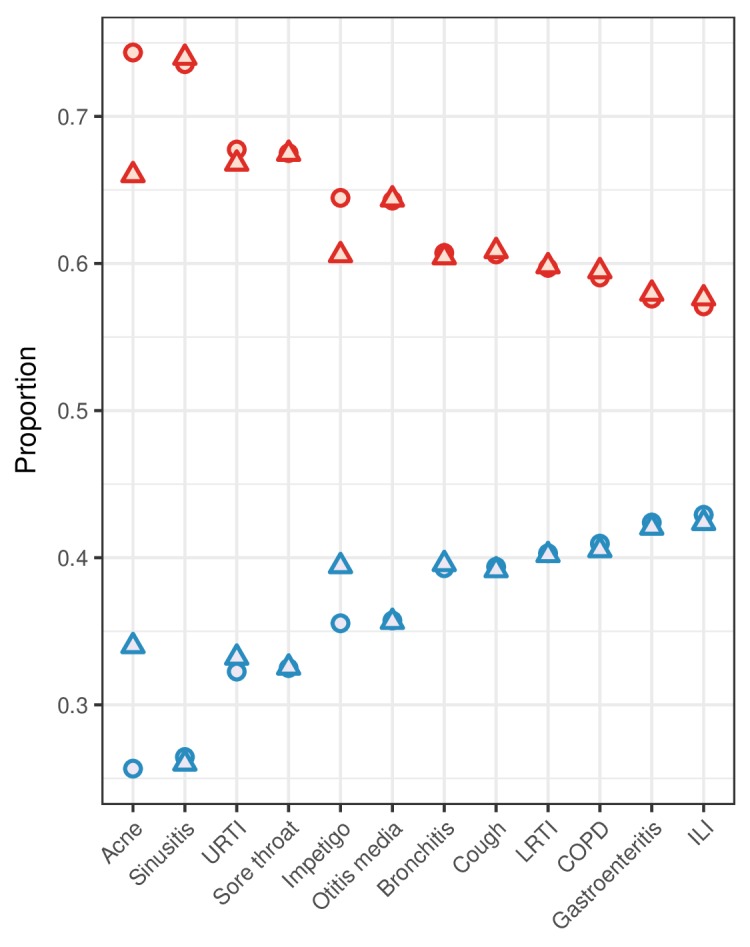

Healthy adult women consulted primary care more than men for all 12 of the conditions included in this study, accounting for 64.3% of all consultations (61.9% among patients with comorbidity). The biggest gender gaps in consultation were in acne (F:M 2.90) and sinusitis (F:M 2.78). However, there was little gender difference in the proportions of healthy adult patients who received antibiotic prescriptions when consulting (table 1). The greatest gaps were in acne, where 60% of consulting men received systemic antibiotics compared with 41% of women (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.66 to 0.69), and in impetigo, where, respectively, 62% and 52% of men and women received prescriptions (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.88). In all other conditions, the difference between the proportions of men and women who received antibiotic prescriptions when consulting was ≤2%, although these gaps were statistically significant in cough (F>M, P=0.02), LRTI (F>M, P=0.02), sinusitis (F>M, P<0.001) and URTI (M>F, P<0.001). These results held in a sensitivity analysis when consultations and prescriptions outside of patients’ primary registered practice were included (see online supplementary appendix). Further, with the exception of acne and impetigo, the proportions of all antibiotics prescribed to men and women for different conditions were proportionate to the proportions of all consultations made by men and women for those conditions (figure 2). Accordingly, the proportions of all antibiotics prescribed to women for each condition correlate strongly with the proportions of consultations made by women (Spearman’s r=0.92; P<0.001), but not with the proportions of women who received prescriptions when consulting with those conditions (Spearman’s r=0.28; P=0.38).

Table 1.

Primary care consultations and antibiotic prescribing proportions per consultation in adult men and women (aged 19–64 years) with and without comorbidity for 12 different conditions. Only consultations from patients’ primary registered practices are included.

| Number of consultations (% of total) | F:M consultation ratio |

Proportion of patients receiving prescription when consulting (95% CI) | Relative risk of receiving antibiotic prescription when consulting as female (95% CI) (P value) | |||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |||

| Acne | 25 676 (74) | 8864 (26) | 2.90 | 41% (40% to 41%) | 60% (59% to 61%) | 0.67 (0.66 to 0.69) (<0.001) |

| Acne with comorbidity | 2344 (66) | 1185 (34) | 1.98 | 40% (38% to 42%) | 55% (52% to 58%) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.78) (<0.001) |

| Bronchitis | 7085 (61) | 4584 (39) | 1.55 | 83% (83% to 84%) | 84% (83% to 86%) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.00) (0.14) |

| Bronchitis with comorbidity | 3101 (60) | 2065 (40) | 1.50 | 87% (86% to 89%) | 89% (88% to 91%) | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00) (0.03) |

| COPD | 3274 (59) | 2271 (41) | 1.44 | 76% (74% to 78%) | 75% (73% to 77%) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) (0.25) |

| COPD with non-respiratory comorbidity | 1287 (56) | 1029 (44) | 1.25 | 73% (70% to 76%) | 70% (69% to 72%) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) (0.02) |

| Cough | 158 614 (61) | 103 058 (39) | 1.54 | 48% (48% to 49%) | 48% (48% to 48%) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) (0.02) |

| Cough with comorbidity | 68 353 (60) | 46 210 (40) | 1.48 | 58% (57% to 58%) | 56% (56% to 57%) | 1.03 (1.02 to 1.04) (<0.001) |

| Gastroenteritis | 41 870 (58) | 30 810 (42) | 1.36 | 6% (6% to 6%) | 6% (6%–6%) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.08) (0.65) |

| Gastroenteritis with comorbidity | 12 184 (57) | 9216 (43) | 1.32 | 8% (7% to 8%) | 7% (7% to 8%) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.14) (0.49) |

| ILI | 10 569 (57) | 7946 (43) | 1.33 | 20% (19% to 20%) | 19% (18%–20%) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) (0.47) |

| ILI with comorbidity | 1951 (57) | 1468 (43) | 1.33 | 25% (23% to 27%) | 29% (27% to 31%) | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.97) (0.02) |

| Impetigo | 5272 (64) | 2907 (36) | 1.81 | 52% (51% to 54%) | 62% (60% to 63%) | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.88) (<0.001) |

| Impetigo with comorbidity | 1139 (66) | 598 (34) | 1.90 | 54% (51% to 57%) | 63% (58% to 66%) | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.94) (<0.001) |

| LRTI | 52 996 (60) | 35 777 (40) | 1.48 | 91% (91% to 92%) | 91% (91% to 91%) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) (0.02) |

| LRTI with comorbidity | 36 693 (60) | 24 519 (40) | 1.50 | 91% (90% to 91%) | 90% (89% to 90%) | 1.01 (1.01 to 1.02) (<0.001) |

| Otitis media | 11 773 (64) | 6545 (36) | 1.80 | 84% (84% to 85%) | 84% (83% to 85%) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) (0.58) |

| Otitis media with comorbidity | 2556 (65) | 1400 (35) | 1.83 | 85% (84% to 87%) | 84% (82% to 86%) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) (0.41) |

| Sinusitis | 46 221 (74) | 16 625 (26) | 2.78 | 88% (88% to 89%) | 86% (86% to 87%) | 1.02 (1.02 to 1.03) (<0.001) |

| Sinusitis with comorbidity | 12 013 (73) | 4394 (27) | 2.73 | 90% (90% to 91%) | 89% (88% to 90%) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.03) (0.006) |

| Sore throat | 136 117 (68) | 65 531 (32) | 2.08 | 57% (56% to 57%) | 57% (56%–57%) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) (0.67) |

| Sore throat with comorbidity | 24 376 (67) | 11 968 (33) | 2.04 | 53% (52% to 54%) | 50% (49% to 51%) | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.08) (<0.001) |

| URTI | 90 295 (68) | 42 998 (32) | 2.10 | 34% (34% to 34%) | 36% (35% to 36%) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.97) (<0.001) |

| URTI with comorbidity | 22 995 (65) | 12 515 (35) | 1.84 | 45% (45% to 46%) | 45% (44% to 46%) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) (0.96) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ILI, influenza-like illness; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

Figure 2.

For common conditions in general practice, the proportions of all consultations (circles) and antibiotic prescriptions (triangles) attributed to women (red) and men (blue). Consultations and prescriptions include all adult patients (aged 19–64) without comorbidity consulting at their primary registered practice. Conditions are ordered by consultation proportion. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ILI, influenza-like illness; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

bmjopen-2017-020203supp001.pdf (421.9KB, pdf)

These gender differences in prescribing were broadly similar among adults with comorbidity. Women with comorbidity were substantially less likely than men with comorbidity to receive antibiotic prescriptions when consulting with acne (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.78) or impetigo (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.94) (table 1), and also ILI (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.97), but for all other conditions the difference between the proportions of men and women who received prescriptions when consulting was ≤3%. Again, among patients with comorbidity, the proportions of antibiotics prescribed to women for each condition correlate strongly with the proportions of consultations made by women (Spearman’s r=0.78; P=0.005), but not with the proportion of women who received prescriptions when consulting with those conditions (Spearman’s r=0.41; P=0.19).

Patients with comorbidity were generally more likely than those without comorbidity to receive antibiotic prescriptions when consulting (see online supplementary appendix). In both men and women, the greatest of these differences were in URTI, cough and ILI, where the proportion of patients who received antibiotics when consulting was approximately 6%–12% higher among patients with comorbidity. Patients with comorbidity were also more likely to receive a prescription when consulting with bronchitis, gastroenteritis and sinusitis. However, among women consulting with sore throat and LRTI, and among men consulting with sore throat, LRTI and acne, the proportions of patients who received antibiotics when consulting were significantly lower among patients with comorbidity than among otherwise healthy patients.

Discussion

This study affirms that there is still a substantial gender gap in antibiotic prescribing in English primary care, and shows that this gap is in large part unexplained by gender differences in UTI and comorbidity. The prescribing gap is most pronounced in adults, with women receiving approximately twice as many antibiotic prescriptions as men, and 70% more when excluding antibiotics used to treat UTI. These differences in prescribing are proximate to differences in health-seeking behaviour, with healthy adult women consulting primary care approximately 80% more than healthy adult men across the 12 conditions included in this study. Accordingly, men and women are just as likely to be prescribed antibiotics when consulting with most common RTIs. These findings provide strong support for the hypothesis that higher antibiotic prescribing in adult women is primarily driven by a higher consultation rate.

This study has a number of strengths. First, THIN is a robust data source that is representative of the English primary care patient population.27 Second, the extensive mapping of Read Codes to clinical conditions made it possible to analyse prescribing across a range of conditions and to account for comorbidities, which differ between men and women and influence whether or not a practitioner prescribes. Third, since UTI in English primary care was almost always treated with trimethoprim or nitrofurantoin during the years of this study, and since these antibiotics were rarely used to treat other conditions in primary care,11 25 it was possible to approximate total prescribing for UTI despite incomplete diagnostic coding. There were also limitations to this work, the largest being that the clinical appropriateness of prescribing could not be determined, and so it was not possible to evaluate whether consulting men and women were differently indicated for antibiotics, and hence whether equal prescribing proportions in RTIs are clinically justified. Further, other patient characteristics that may covary with gender and consultation behaviour, such as socioeconomic status, could not be considered. Finally, the quality of diagnostic coding varies within and between practices, which may bias estimates of consultation and prescribing.

It is well observed that rates of primary care consultation and antibiotic prescribing are substantially higher in adult women than in adult men,6–8 17–19 but previous work has been unable to show that the gender gap in antibiotic prescribing can primarily be attributed to consultation, as opposed to other relevant factors such as UTI, comorbidity and other patient and prescriber behaviours. These findings build on two previous studies of antibiotic prescribing in primary care between 1997–2006 and 2007–2008, respectively.20 21 Both studies found similar male and female prescribing proportions in a selection of RTIs, but were conducted in a limited subset of patients and did not account for comorbidities, non-respiratory conditions, patients consulting outside of their registered practice, or gender differences in gross antibiotic prescribing at the population level.

Antibiotic prescribing was proportionate to consultation for most conditions, but skin conditions were notable exceptions: men consulted much less with acne and impetigo but were substantially more likely than women to receive an antibiotic prescription when consulting (although acne is unique in that women but not men can be treated with combination oral contraceptives, confounding gender comparisons in antibiotic prescribing). Although women consult more frequently, they are not known to suffer from greater incidence or severity of disease in the conditions included here.12 13 Studies have also shown that men tend to consult later in the course of their illness and may have a higher threshold to seeking care.18 28 29 When prescribing is truly reflective of patient need (eg, as in skin conditions, due to low diagnostic uncertainty), a higher prescribing proportion in men may be expected if, on average, less frequent and/or delayed consultation is coupled with more severe clinical presentation. Yet, for the remaining conditions in this study—predominantly RTIs—prescribing proportions in male and female patients were strikingly similar despite vast differences in consultation. This may be indicative of imprudent prescribing. In non-skin conditions there is often (1) considerable diagnostic uncertainty (eg, difficulty in differentiating acute bronchitis and pneumonia in primary care) and (2) uncertainty around subjective, insensitive or unspecific clinical severity markers (eg, reliance on patient symptom reporting and other clinical features that poorly predict benefit from antibiotic treatment).30 31 Faced by these uncertainties, GPs may prescribe antibiotics precautiously—and imprudently—to a large proportion of patients with RTI, regardless of disease severity, resulting in high prescribing proportions in all patients.

Although imprudent prescribing has been the target of numerous antimicrobial stewardship interventions, it remains obstinate in English primary care,32 and the combination of high consultation rates among female patients and overly precautious antibiotic prescribing behaviour among GPs could result in a disproportionate share of inappropriate (ie, unnecessary) antibiotic prescriptions in women. However, previous studies of gender differences in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing have found mixed results,21 33 and it remains to be shown whether men and women in UK primary care differ in their objective clinical need for antibiotics when consulting with RTIs and other common conditions. Yet, regardless of whether or not women are more likely to receive an inappropriate prescription per consultation, it is likely that a higher level of antibiotic prescribing in women is accompanied by a greater total number of inappropriate prescriptions.

Conclusions

This study reaffirms known gender gaps in health-seeking behaviour and antibiotic prescribing, and shows that, with exceptions, adult men and women in English general practice are equally likely to receive an antibiotic prescription when seeking care for common conditions, and that gender differences in the number of antibiotics prescribed are largely driven by differences in consultation behaviour. Equal prescribing proportions may seem to indicate relative parity in how men and women are treated when they consult, but women consult vastly more than men yet have not been shown to suffer from more frequent or severe infection in the conditions included in this study. It is thus plausible that a higher rate of consultation in women is coupled with a milder average clinical presentation, but that overly precautious GPs prescribe even when antibiotics are not clinically necessary, resulting in high rates of prescribing in all patients. Given the urgent need to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing, it is crucial to more deeply understand how and to whom antibiotics are overprescribed. To this end, future work should further investigate gender differences in the clinical (in)appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing in primary care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

DRMS and FCKD contributed equally.

Contributors: DRMS and KBP conceived and designed the study. KBP extracted the data from The Health Improvement Network database. FCKD and KBP conducted the analyses. DRMS, JVR, KBP and TS carried out the interpretation of data. DRMS drafted the manuscript. FCKD, JVR, KBP and TS critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version prior to submission.

Funding: This work was funded internally by Public Health England.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study received approval from THIN’s Scientific Review Committee (reference number 16THIN-071-A2).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This analysis is based on a large sample from The Health Improvement Network, provided by IMS Health. The authors’ licence for using these data precludes the sharing of raw data with third parties.

References

- 1.Department of Health. UK five year antimicrobial resistance strategy 2013 to 2018. London: Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shallcross LJ, Davies DS. Antibiotic overuse: a key driver of antimicrobial resistance. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:604–5. 10.3399/bjgp14X682561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler CC, Rollnick S, Pill R, et al. Understanding the culture of prescribing: qualitative study of general practitioners' and patients' perceptions of antibiotics for sore throats. BMJ 1998;317:637–42. 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadieux G, Tamblyn R, Dauphinee D, et al. Predictors of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care physicians. CMAJ 2007;177:877–83. 10.1503/cmaj.070151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pouwels KB, Dolk FCK, Smith DRM, et al. Explaining variation in antibiotic prescribing between general practices in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73(Suppl 2):ii19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schröder W, Sommer H, Gladstone BP, et al. Gender differences in antibiotic prescribing in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:1800–6. 10.1093/jac/dkw054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majeed A, Moser K. Age- and sex-specific antibiotic prescribing patterns in general practice in England and Wales in 1996. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:735–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayward GN, Fisher RFR, Spence GT, et al. Increase in antibiotic prescriptions in out-of-hours primary care in contrast to in-hours primary care prescriptions: service evaluation in a population of 600 000 patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:2612–9. 10.1093/jac/dkw189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider-Lindner V, Quach C, Hanley JA, et al. Secular trends of antibacterial prescribing in UK paediatric primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66:424–33. 10.1093/jac/dkq452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol 2010;7:653–60. 10.1038/nrurol.2010.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolk FCK, Pouwels KB, Smith DRM, et al. Antibiotics in primary care in England: which antibiotics are prescribed and for which conditions? J Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73(Suppl 2):ii2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutiérrez F, Masiá M, Mirete C, et al. The influence of age and gender on the population-based incidence of community-acquired pneumonia caused by different microbial pathogens. J Infect 2006;53:166–74. 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falagas ME, Mourtzoukou EG, Vardakas KZ. Sex differences in the incidence and severity of respiratory tract infections. Respir Med 2007;101:1845–63. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sue K. The science behind "man flu". BMJ 2017;359:j5560 10.1136/bmj.j5560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinkhasov RM, Wong J, Kashanian J, et al. Are men shortchanged on health? Perspective on health care utilization and health risk behavior in men and women in the United States. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:475–87. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vos HM, Schellevis FG, van den Berkmortel H, et al. Does prevention of risk behaviour in primary care require a gender-specific approach? A cross-sectional study. Fam Pract 2013;30:179–84. 10.1093/fampra/cms064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Hunt K, Nazareth I, et al. Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003320 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs 2005;49:616–23. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keene J, Li X. Age and gender differences in health service utilization. J Public Health 2005;27:74–9. 10.1093/pubmed/fdh208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulliford M, Latinovic R, Charlton J, et al. Selective decrease in consultations and antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections in UK primary care up to 2006. J Public Health 2009;31:512–20. 10.1093/pubmed/fdp081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagger K, Nielsen ABS, Siersma V, et al. Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and demand for antibiotics in patients with upper respiratory tract infections is hardly different in female versus male patients as seen in primary care. Eur J Gen Pract 2015;21:118–23. 10.3109/13814788.2014.1001361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alspach JG. Is there gender bias in critical care? Crit Care Nurse 2012;32:8–14. 10.4037/ccn2012727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns 2009;76:356–60. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British national formulary: antibacterial drugs. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosello A, Pouwels KB, Domenech de Cellès M, et al. Seasonality of urinary tract infections in the United Kingdom in different age groups: longitudinal analysis of The Health Improvement Network (THIN). Epidemiol Infect 2018;146:37–45. 10.1017/S095026881700259X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public Health England. Influenza: the green book, chapter 19. London: Public Health England, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blak BT, Thompson M, Dattani H, et al. Generalisability of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database: demographics, chronic disease prevalence and mortality rates. Inform Prim Care 2011;19:251–5. 10.14236/jhi.v19i4.820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briscoe ME. Why do people go to the doctor? Sex differences in the correlates of GP consultation. Soc Sci Med 1987;25:507–13. 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90174-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banks I. No man’s land: men, illness, and the NHS. BMJ 2001;323:1058–60. 10.1136/bmj.323.7320.1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cals J, Hopstaken R. Lower respiratory tract infections: treating patients or diagnoses? J Fam Pract 2006;55:545–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jakobsen KA, Melbye H, Kelly MJ, et al. Influence of CRP testing and clinical findings on antibiotic prescribing in adults presenting with acute cough in primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2010;28:229–36. 10.3109/02813432.2010.506995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smieszek T, Pouwels KB, Dolk FCK, et al. Potential for reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in English primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73(Suppl 2):ii36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barlam TF, Morgan JR, Wetzler LM, et al. Antibiotics for respiratory tract infections: a comparison of prescribing in an outpatient setting. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015;36:153–9. 10.1017/ice.2014.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020203supp001.pdf (421.9KB, pdf)