Abstract

Introduction

Prescription-drug use in the USA has increased by more than 60% in the last three decades. Prevalence of prescription-drug use among pregnant women is currently estimated around 50%. Prevalence of illicit drug use in the USA is 14.6% among pregnant adolescents, 8.6% among pregnant young adults and 3.2% among pregnant adults. The first step in identifying problematic drug use during pregnancy is screening; however, no specific substance-use screener has been universally recommended for use with pregnant women to identify illicit or prescription-drug use. This study compares and validates three existing substance-use screeners for pregnancy—4 P’s Plus, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Quick Screen/Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and the Substance Use Risk Profile-Pregnancy (SURP-P) scale.

Methods and analysis

This is a cross-sectional study designed to evaluate the sensitivity, specificity and usability of existing substance-use screeners. Recruitment occurs at two obstetrics clinics in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. We are recruiting 500 participants to complete a demographic questionnaire, NIDA Quick Screen/ASSIST, 4 P’s Plus and SURP-P (ordered randomly) during their regularly scheduled prenatal appointment, then again 1 week later by telephone. Participants consent to multidrug urine testing, hair drug testing and allowing access to prescription drug and birth outcome data from electronic medical records. For each screener, reliability and validity will be assessed. Test–retest reliability analysis will be conducted by examining the results of repeated screener administrations within 1 week of original screener administrations for consistency via correlation analysis. Furthermore, we will assess if there are differences in the validity of each screener by age, race and trimester.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland (HP-00072042), Baltimore, and Battelle Memorial Institute (0619–100106433). All participants are required to give their informed consent prior to any study procedure.

Keywords: pregnancy, biochemical verification, nida quick screen/assist, surp-p, 4p’s plus, substance use screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will provide insight into the substance-use screener(s) that works best to identify illicit drug use and prescription-drug misuse during pregnancy, using hair and urinalysis for biochemical verification of long-term and short-term substance use in a convenience sample of 500 pregnant women.

The study will provide evidence of screener usefulness and acceptability in prenatal clinic settings that could inform US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations for substance-use screening during pregnancy.

The study uses electronic medical records to capture prescribed drugs and birth-outcome data of enrolled participants to assess for associations between substance use in pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes.

A limitation of this study is the reliance on a convenience sample from two urban clinics rather than a national sample.

Findings from this study will not be generalisable to pregnant adolescents who were not included in our study sample.

Introduction

Abuse of prescription and illicit drugs in pregnancy is a growing cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in the USA. According to data from the 2012 and 2013 US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the rate of current illicit drug use (including non-medical use of prescription drugs) in pregnant adolescents and women was 14.6% among adolescents (aged 15–17 years), 8.6% among young adults (aged 18–25 years) and 3.2% among adults (aged 26–44 years).1 The consequences of this problem include spontaneous abortions, stillbirths, low birth weight, prematurity, neonatal abstinence syndrome and congenital malformations.2

Given the relatively high frequency of provider–patient contact during the prenatal period, obstetrical care providers have the unique opportunity to identify substance abuse in pregnancy. Furthermore, for pregnant women from socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, obstetricians often serve as primary care physicians and typically are the only contact these women have with the healthcare system.3 Prenatal screening for drug use is an important way to identify drug abuse in pregnancy, as strongly recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).4 But, while validated alcohol and tobacco screeners have been recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force, there is currently no universally recommended validated screening tool for identifying illicit drug use in pregnancy.

Currently, three separate validated tools exist that screen for use of more than one substance among pregnant women: The Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST); the 4 P’s Plus; and the Substance Use Risk Profile–Pregnancy (SURP-P).5–8 ASSIST has been validated across several populations, but it has not yet been formally validated with pregnant women.5 A modified ASSIST, with items on tobacco and alcohol use removed, was incorporated by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to their Quick Screen as a follow-up to the four-question prescreener; this is referred to as the NIDA Quick Screen/ASSIST. The 4 P’s Plus was designed to identify drug use in pregnancy and has been validated with pregnant women.7 The 4 P’s Plus is brief but is associated with a licensing fee which may be a hindrance to widespread use. The SURP-P is a validated scale composed of three questions that can differentiate between populations of pregnant women at low risk or high risk for substance use.8 The SURP-P is a simple and flexible tool for identifying possible substance use in pregnancy; however, a further screen is required for identifying those who would require treatment.

To bridge this gap and identify the most universally valid and reliable screening tool for drug abuse in pregnancy, this study aims to compare and validate three existing substance-use screeners—4 P’s Plus, NIDA Quick Screen/ASSIST and the SURP-P scale—among a cross-section of 500 pregnant women presenting to two obstetrics clinics in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. The overarching goal of this effort is to determine which screening tool is most effective in identifying prescription-drug abuse and illicit drug use among pregnant women and acceptable among patients and clinicians so that evidence-based guidance may be offered.

Methods/design

Specific aims

Specific aims of this study are to: (a) conduct validity analyses to determine sensitivity, specificity, usability (test–retest reliability) and how each scale compares with the others and to the gold standard of urine and hair drug testing in identifying prescription and illicit drug use; (b) determine the impact of clinic population variables (age, race, trimester of pregnancy) on validity of the three substance-use screeners; and (c) assess birth outcomes (birth weight, gestational age, head circumference and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions) associated with the most widely used prescription drug and multidrug exposure.

Study design

This study is a cross-sectional study that evaluates the sensitivity, specificity and usability of existing substance-use screeners. We chose this study design following an extensive search of the literature, an overall assessment of feasibility and consultation with stakeholders (eg, clinicians, pregnant women and substance-use researchers). We believe that a cross-sectional study such as ours is appropriate for the evaluation of the accuracy and reliability of these screeners. We were also aided by the knowledge that the prevalence of substance use in pregnancy is high.1 This implies that we are likely to obtain good sensitivity and specificity estimates, with narrow CIs, in a cross-sectional design which is favourable in terms of cost and feasibility.

Setting

The study is being implemented at two urban obstetrics clinics which serve diverse populations of pregnant women. The study plans to recruit 500 participants to complete a demographic questionnaire, followed by a randomised order of the NIDA Quick Screen/NIDA-modified ASSIST, 4 P’s Plus and SURP-P. Participants are recruited during their regularly scheduled prenatal appointment, then contacted again 1 week later by telephone to re-administer the screeners. Participants consent to multidrug urine testing, hair drug testing and access to prescription-drug and birth-outcome data from electronic medical records (EMR).

Recruitment sites

We are recruiting participants from two obstetrics outpatient clinics from January 2017 to January 2018. Currently, all obstetrical patients are screened for use of drugs, alcohol and tobacco at their first prenatal visit by medical staff. Additionally, all new obstetrical patients receive an in-depth evaluation by a social worker which includes a more detailed assessment of both substance use and mental health disorder history.

In the first clinic, which is the larger of the two clinics, most patients (97%) are publicly insured with medical assistance and are over the age of 20 (80%). This clinic’s population is primarily African-American and low-income, all of whom undergo urine toxicological screening for substance-use identification. Based on preliminary data obtained from the clinic, about 950 individual obstetrical patients are cared for at this clinic annually. In the second (smaller) clinic, approximately 500 pregnant women are cared for annually. Most patients (87%) have commercial insurance, and 13% have either medical assistance or Medicare. Most are over the age of 20 years (90%). Due to varying insurance coverage for urine toxicology screens, patients in this office do not universally undergo urine toxicology screening but all are screened for drug use using various interview techniques by their obstetrical care providers at their first prenatal visit. Based on historical data, we expect about 500 individual obstetrical patients to be cared for in this clinic across all trimesters of pregnancy in the 1 year of study recruitment.

Across both study sites, our source population covers a diverse set of participants and captures pregnant women across all socioeconomic categories, insurance types, ethnicities and drug-use patterns. This ensures that our study results are generalisable to most populations of pregnant women.

Study population

In the first clinic, of the estimated 950 individual obstetrical patients cared for at this clinic annually, we anticipated approaching 403 (50%), and expected 322 (80%) or more to agree to participate in this study.

In the second clinic, of the approximately 500 pregnant women cared for annually, we expect at least 450 (90%) to meet eligibility criteria. We anticipate approaching 225 pregnant women (50%) and expect 180 (80%) or more to agree to participate in this study.

Expected participation percentages are based on a similar grant-funded study that recruited pregnant smokers from the same population and required consent for urine testing (cotinine) and birth-data abstraction from EMR.

Participant eligibility criteria include the following: (a) currently pregnant (predetermined by clinic staff), (b) age 18 or older, (c) able to speak and understand English sufficiently to provide informed consent and (d) natural hair length at least 3 cm to allow for substance-use testing.

If eligibility criteria are met, research staff then obtain informed consent and medical releases for urine collection, hair drug testing and prescription-drug and birth-outcome data abstraction from the EMR.

Ethics and dissemination

All participants are required to give their informed consent prior to any study procedure. All research staff complete ethics training via the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative annually.

Study procedures

Approach

All patients entering the clinics for prenatal appointments are approached by research staff at check-in and asked to read a brief description of the study to determine their interest in participating (excluding those previously approached). Research staff keep track of which patients have been approached already to avoid repetitive recruitment efforts. The study description includes a section requesting basic demographic information (if they would allow its use for anonymous, grouped analysis) and at the bottom asks potential participants to note their interest and return to clinic staff. There are check boxes for ‘not interested’ (with additional space beneath for noting reasons for lack of interest) and ‘interested in learning more’. Patients who are not interested in the study are not to be contacted further; however, the basic demographic information provided is used for comparative analyses with study participants to assess for selection bias. If a patient expresses interest, the research staff approaches her as she waits for her prenatal appointment either on the same day or at a future prenatal appointment.

Recruitment

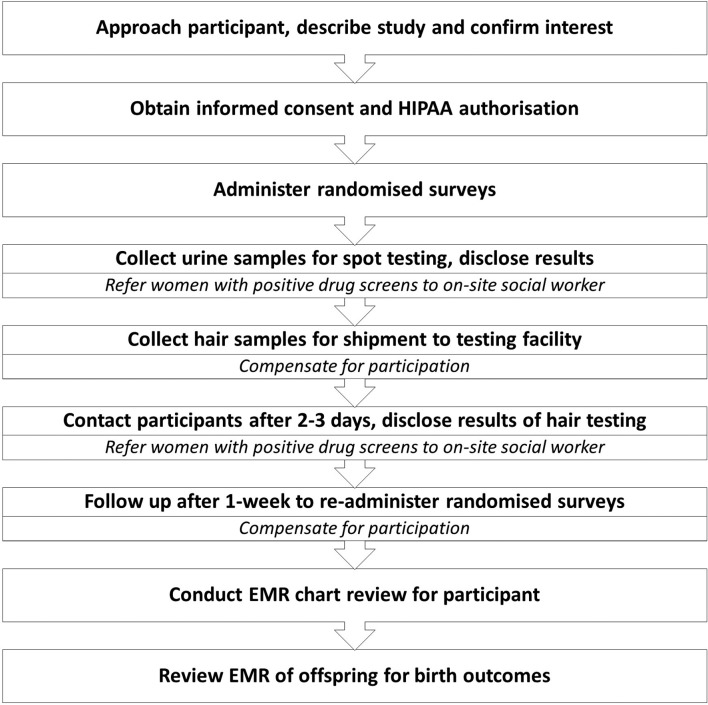

At the enrolment visit, the staff escorts potential participants from the waiting area to a private room, further describes the study and determines whether potential participants meet all eligibility criteria. If eligibility criteria are met, the staff obtains informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorisation (for urine collection, hair drug testing and prescription-drug and birth-outcome data abstraction from the EMR). Women who refuse to participate are thanked for their time, and no further contact is made. The research visit takes 20–30 min. Enrolled participants are compensated for their time using a reloadable gift card for their time. The typical patient wait time to see medical staff at each clinic is from 30 minutes to 1 hour, so data collection does not typically interfere with medical visits. See figure 1 for study procedures.

Figure 1.

Study procedures. EMR, electronic medical records; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Self-report measures

Participants complete a demographic questionnaire. Afterwards, the NIDA Quick Screen/NIDA-modified ASSIST, 4 P’s Plus and SURP-P surveys are administered on a Wi-Fi enabled iPad Pro through SurveyMonkey (ie, online survey software). See table 1 for description of surveys and the timing of administration during the study. These surveys are assigned to participants in a random sequence; this randomisation service is provided by SurveyMonkey. The questions are read aloud by the interviewer and entered directly into SurveyMonkey so that electronic submission is instantaneous, and data can be obtained by the research team at any time.

Table 1.

Study Instruments

| Instrument | Description/construct | Use in study |

| Demographic questionnaire | 20-Item questionnaire that collects demographic and general information such as age, marital status, education, employment status, ethnicity and reproductive history. | Enrolment |

| NIDA Quick Screen/ASSIST | 9-Item combined NIDA Quick Screen and modified-ASSIST to screen for tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs. | Enrolment, 1-week follow-up |

| 4 P’s Plus | 4-Item screener for alcohol and general substance use. | Enrolment, 1-week follow-up |

| SURP-P | 3-Item screener for alcohol and substances | Enrolment, 1-week follow-up |

ASSIST, Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; NIDA, National Institute on Drug Abuse; SURP-P, Substance Use Risk Profile-Pregnancy.

Biochemical measures

Participants are asked to consent that urine collected for their prenatal appointment that day is also tested for various drugs by research staff (table 2). If sufficient urine is unavailable for testing, participants are given bottled water and asked to provide another sample prior to leaving the clinic. Participants must also consent to hair testing which involves the cutting of approximately 100 strands of hair from the crown of the head (or other body hair if head hair is unavailable). Samples are then shipped to an external laboratory on the same day for drug testing using mass spectrometry.

Table 2.

Drug detection windows and cut-offs for urine and hair testing

| Drug class | Detection window | Confirmation cut-off | |

| URINE | Cocaine (COC) | 2–4 Days | 300 ng/mL |

| Marijuana (THC) | 15–30 Days | 50 ng/mL | |

| Opiates (OPI) | 2–4 Days | 2000 ng/mL | |

| Amphetamines (AMP) | 2–4 Days | 1000 ng/mL | |

| Methamphetamines (mAMP) | 3–5 Days | 1000 ng/mL | |

| Phencyclidine (PCP) | 7–14 Days | 25 ng/mL | |

| Benzodiazepines (BZO) | 3–7 Days | 300 ng/mL | |

| Barbiturates (BAR) | 4–7 Days | 300 ng/mL | |

| Methadone (MTD) | 3–5 Days | 300 ng/mL | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) | 1000 ng/mL | ||

| Oxycodone | 2–4 Days | 100 ng/mL | |

| Propoxyphene | 1–2 Days | 300 ng/mL | |

| Buprenorphine (BUP; Suboxone, Subutex) | 2–3 Days | 10 ng/mL | |

| HAIR | Marijuana (THC) | Up to 90 days | |

| Amphetamines (AMP) | Up to 90 days | ||

| Cocaine (COC) | Up to 90 days | ||

| Opiates (OPI) | Up to 90 days | ||

| Phencyclidine (PCP) | Up to 90 days |

All women who screen positive on either biological multidrug test or any one of the screeners are contacted immediately (for urine and screener results) or within 72 hours (for hair results) to detail the results of her test, encourage the participant to talk with her physician about her substance use and offer her referrals to community resources for treatment that mirror what is currently given to patients by medical staff in each clinic. They are encouraged to speak with the on-site clinic social worker who can provide further support.

Birth outcome measures

Birth outcome data, including miscarriage, stillbirth, birth weight, gestational age, head circumference and NICU admissions, as well as a list of drugs prescribed during pregnancy and their dosage are collected by research staff via the EMR and entered into SurveyMonkey.

Participant follow-up

After completion of this research visit, participants are contacted once more by telephone 1 week after completing the surveys to complete the three screeners again to assess test–retest reliability. The average time commitment for the call is about 10–15 minutes, and on completion, $25 is loaded onto the reloadable gift card provided the week prior.

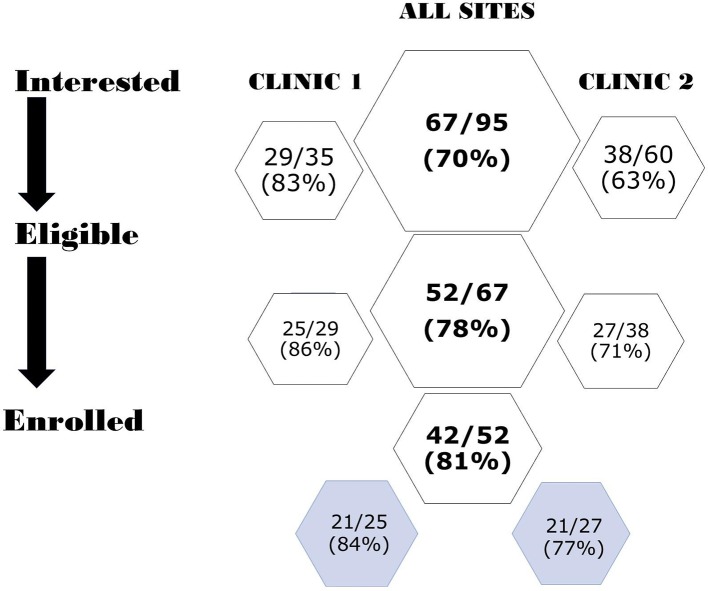

Pilot study

To examine the recruitment process and determine acceptability from the target population of substance-using pregnant women prior to the start of the study, we conducted a 1-month pilot study. Each step of the recruitment process was reviewed to determine where improvements could be made.

We recruited 21 participants from each site for a total of 42 participants (table 3). Mean age (SD) of participants was 30.1 years (5.64). By race/ethnicity, 11 participants (26.2%) were white, 25 (59.5%) were black/African-American, 4 (9.5%) were Asian, 1 (2.4%) was Hispanic and 1 (2.4%) was of other race. About 24.4% tested positive for illicit drugs on urine testing, 22% tested positive on hair sample testing. Seven (7) participants (16.7%) were lost to follow-up.

Table 3.

Pilot study participant characteristics

| Characteristics, n=42 | Clinical site | ||

| Clinic 1 | Clinic 2 | Both sites | |

| Number of participants | 21 | 21 | 42 |

| Participant age in years, mean (SD) | 27.10 (5.09) | 33.05 (4.54) | 30.07 (5.64) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| African-American/black | 18 (85.7) | 7 (33.3) | 25 (59.5) |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (9.5) |

| Caucasian/white | 2 (9.5) | 9 (42.9) | 11 (26.2) |

| Hispanic, Latino or Chicano | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.4) |

| Some other group | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| Trimester, n (%) | |||

| First | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (9.5) |

| Second | 6 (28.6) | 6 (28.6) | 12 (28.6) |

| Third | 13 (61.9) | 13 (61.9) | 26 (61.9) |

| Urine results, n (%) | |||

| Negative for all substances | 15 (71.4) | 16 (80.0) | 31 (75.6) |

| Positive for at least one substance | 6 (28.6) | 4 (20.0) | 10 (24.4) |

| Hair results, n (%) | |||

| Negative for all substances | 12 (60.0) | 18 (85.7) | 30 (73.2) |

| Positive for at least one substance | 7 (35.0) | 2 (9.5) | 9 (22.0) |

| Invalid | 1 (5.0) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (4.9) |

| Study disposition, n (%) | |||

| Study completes | 19 (90.48) | 16 (76.2) | 35 (83.3) |

| Lost to follow-up | 2 (9.52) | 5 (23.8) | 7 (16.7) |

Results from the pilot study confirmed the feasibility of this study. Eligibility criteria did not appear too restrictive, given the eligibility rate of 78% (although slightly lower than anticipated; figure 2). Overall, there was good comprehension of surveys, a low refusal rate for hair sampling (1 refusal/95 approached, 1.1%) and high study enrolment (figure 2). The recruitment process, on an average, took 40 minutes.

Figure 2.

Pilot study participation.

Power and sample size

The sample size of 500 participants was chosen based on power analyses for the primary study questions. Based on a one-sample binomial approach, with a sample size of 500 participants, we can be 95% confident that the false-negative rate in the population is under 10% (assuming no more than 35 individuals test positive in the biologic drug tests without a positive survey screener result). Similarly, we can be 95% confident that the false-negative rate in the population is under 5% (assuming no more than 15 individuals test positive in the urine drug test without a positive survey screen result in the study). According to McNemar’s test, if at least 15% of the study participants have disagreement between any pair of survey results, 500 is a sufficient sample size to determine significant disagreement.

After a preliminary sample size of 500 was chosen, a power analysis was conducted to determine the detectable differences in age, race and trimester with a sample size of 500. The power of the test of proportions was calculated based on the difference in the proportion of false negatives in each age group, race and trimester of pregnancy. Assuming recruitment of an equal number of women aged 18–25 years and women 26 and older, and that their respective positive screener results are 20% and 10%, then the power to detect that difference is 0.88. If the respective screener results are 15% and 20%, then the power is much lower (0.31). If we further assume that recruitment of 23% white women and 77% non-white women and that white women have a false-negative rate of 5% and non-white women have a false-negative rate of 15%, then the power is high (0.87). Similarly, if we assume recruitment of an equal number of women in each of the three trimesters of pregnancy and that women in one trimester have a false-negative rate of 20% while women in another trimester have a false-negative rate of 35%, then the power is high (0.87).

Analysis

For each screener, reliability and validity (convergent/discriminant validity) will be assessed, including calculating correlation coefficients between each pair of screeners and between each screener and the appropriate biologic drug tests. Test–retest reliability analysis will be conducted by examining the results of repeated screener administrations within 1 week of original screener administrations for consistency via correlation analysis. The sensitivity and specificity of each instrument will be calculated, presented and interpreted. Each survey instrument will be compared with the gold standard (hair and urine sample drug testing) by comparing the false-negative rates to a predetermined limit of acceptability. If the upper one-sided 95% binomial CI around the false-negative rate in the sample is less than that limit, then the survey instrument is considered acceptable. The 4 P’s Plus and SURP-P survey screeners will be compared with both urine and hair testing in the assessment of their sensitivity and specificity in relation to short-term and long-term drug use, respectively. The NIDA Quick Screen/NIDA-modified ASSIST screener will be compared with urine testing, while particular questions from the screener regarding long-term drug use will be compared with hair testing.

Furthermore, we will assess if there are differences in the validity of each screener by age, race and trimester. The false-negative rate for each screener will be presented by age, race and trimester. A two-sided test of proportions will be conducted to test for significant differences in false-negative rates between age, race and trimester for each screener. Χ2 tests (or Fisher’s exact tests if subgroup sizes are small) may be conducted to determine whether the distribution of responses on each survey instrument is similar for age, race and trimester. To examine differences in screener validity by age, race and trimester, logistic regression models will be fitted to the data. To separately analyse differences in probability of false-positive results and false-negative results on each survey, data will be stratified by screener and screener result (positive or negative) for a total of six models. In each model, the dependent variable will be coded 1 for invalid screener result (false negative or false positive) and 0 for valid screener result (true negative or true positive). Independent variables for age, race and trimester will be added to the models to test whether they have a significant effect on the probability of an invalid screener result. Two-way interaction terms will be included in the model if they are found to have significant effects. In order to stratify results by trimester, if trimester or any two-way interaction term including trimester is a significant effect in the models for any of the screeners, probabilities of false-positive/false-negative result will be presented separately by each trimester.

Finally, the prevalence of prescription and illicit drug use will be calculated based on hair test results and self-report. Prevalence of multidrug exposure will also be calculated. An analysis of variance model will be fitted to the data with a fixed effect for drug use (negative, positive, positive for multidrug exposure) to test for significant differences in birth weight, gestational age and head circumference based on participant hair drug test results. Significant differences will be noted and discussed. The relative risk of NICU admission, stillbirth and miscarriage will be examined. A risk ratio will be calculated and will quantify the percentage difference in these three variables between those with positive hair drug tests versus negative drug test. The risk ratio takes on values between zero and infinity. A risk ratio of one means that there is no difference in NICU admissions, stillbirth or miscarriage between the participants’ biologic drug test results. A risk ratio very small (close to zero) or very large means a large difference between NICU admissions, stillbirth or miscarriage based on the hair drug test results. Approximate 95% CIs for the relative risk will be calculated. The same relative risk ratios and 95% CIs will be calculated for a positive biologic drug test for multidrug exposure versus positive for a single-drug exposure. Further, relative risk ratios will be computed with 95% CIs stratified by trimester.

Discussion

Our ongoing research has five aspects of significance. First, the importance of screening pregnant women and the public-health impact of the current research is tied directly to the negative health consequences associated with illicit-drug and prescription- drug use during pregnancy. Second, it uses both urine and hair testing to enable us to examine past 90-day substance-use history with precision. Hair analysis provides nearly twice the number of positives due to its longer detection window, but often cannot capture very recent use. Urinalysis supplements hair analysis to allow for the most comprehensive validation of screeners possible. Third, the study compares three screeners acknowledged by the WHO to screen for multiple substances to each other and to the biological screeners (gold standard). This is the first study to conduct a direct, head-to-head comparison of multiple screening tools for prescription-drug and illicit-drug use among pregnant women, while also using biologic measures as a gold standard against which to compare. Fourth, the study uses EMR to capture prescribed drugs and birth outcome data of enrolled participants. The ability to access a participant’s prescription-drug orders enables better tracking and distinction between prescription-drug use and abuse, while birth outcome data allows for determination of associations between specific drug use and birth outcomes. Fifth, the study has the potential to shift clinical practice towards universal standardised substance-use screening.

Despite the significant contributions of this work, it is not without limitations. Though the study will enrol a large sample of pregnant women, it is a convenience sample from two prenatal clinics in an urban area. We have attempted to increase generalisability by enrolling women from two clinics with different population characteristics: one clinic serves low-income, Medicaid-eligible, primarily African-American women and the other serves privately insured, primarily white women. Second, there is a possibility of selection bias. Incentive may be more appealing to those who have lower socioeconomic status, individuals with more time may be those willing to take the study and pregnant women who use substances may not want to participate. For the latter point, we have obtained a certificate of confidentiality and ensured participants that their data will not be shared with anyone including clinic staff. Finally, our study is limited to adults. Though our initial protocol included adolescents, the institutional review board did not allow for ‘no-benefit’ studies enrolling pregnant adolescents. This is an important area for further exploration, given that pregnant adolescents report higher substance-use rates than pregnant adults in national surveys.

The primary innovation of this project is that it may provide a final evidence-based recommendation for the tool(s) best suited to screen for illicit and prescription drugs among a diverse sample of pregnant women. The provision of this evidence-based guidance to clinicians is a concrete application of findings that is rare in public health research. We recognise that screening is a first step; also important is the need for a public health focus on treatment of substance use during pregnancy to enhance the odds of a successful pregnancy outcome. Barriers to treatment that are imperative to address are the potential legal repercussions of identifying substance use during pregnancy that exist in some states9 and unintentional breach of confidentiality.10 There is a strong need for a re-examination of state policies so that women are not punished for having a treatment need.

Substance use during pregnancy, and specifically prescription-drug and illicit-drug use, are high-priority topics for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WHO, ACOG, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, NIDA and the National Institutes of Health. Universal screening has the potential to greatly enhance maternal and infant health outcomes and reduce healthcare costs. Specifically, the current research supports the following Healthy People 2020 public health goals and objectives which include reducing maternal illness and complications due to pregnancy; increasing the proportion of pregnant women who receive adequate prenatal care’ increasing abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes and illicit drugs among pregnant women; and increasing the proportion of women delivering a live birth who received preconception care services and practised key recommended preconception health behaviours.

This research addresses an important problem by identifying a valid substance-use screening instrument for illicit and prescription drugs among pregnant women that is accurate, brief and acceptable to both patients and healthcare providers in a primary care setting. Identifying and validating one instrument that functions the closest to the ‘gold standard’ of biologic testing (ie, urine and hair) and disseminating this information widely will increase the likelihood that primary care clinics nationwide may adopt a quick and easy screener universally. We may find that one instrument does not stand out but that each has its distinct advantages and disadvantages; in this case, the performance of each measure will be detailed with recommendations for which screener may work the best with a given population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: VC-C conceived the study. VC-C, EAO, ENP, KT, BK and KM participated in the drafting of the manuscript and each approved the final draft.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA041328.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study is approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Maryland (HP-00072042), Baltimore; and Battelle Memorial Institute (0619-100106433). All participants are required to give their informed consent prior to any study procedure.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No.(SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scholle SH, Kelleher K. Assessing primary care performance in an obstetrics/gynecology clinic. Women Health 2003;37:15–30. 10.1300/J013v37n01_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, American Society of Addiction Medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:79–80. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256496e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction 2002;97:1183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. . A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1155–60. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chasnoff IJ, Wells AM, McGourty RF, et al. . Validation of the 4P’s Plus screen for substance use in pregnancy validation of the 4P’s Plus. J Perinatol 2007;27:744–8. 10.1038/sj.jp.7211823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yonkers KA, Gotman N, Kershaw T, et al. . Screening for prenatal substance use: development of the Substance Use Risk Profile-Pregnancy scale. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:827 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ed8290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guttmacher Institute. State laws and policies: substance use during pregnancy. 2017. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/substance-use-during-pregnancy (accessed 18 Dec 2017).

- 10.Knight KR. Addicted pregnant poor. North Carolina, US: Duke University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.