Abstract

Objective

First, to investigate the intertester reliability of clinical shoulder instability and laxity tests, and second, to describe the mutual dependency of each test evaluated by each tester for identifying self-reported shoulder instability and laxity.

Methods

A standardised protocol for conducting reliability studies was used to test the intertester reliability of the six clinical shoulder instability and laxity tests: apprehension, relocation, surprise, load-and-shift, sulcus sign and Gagey. Cohen’s kappa (κ) with 95% CIs besides prevalence-adjusted and bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK), accounting for insufficient prevalence and bias, were computed to establish the intertester reliability and mutual dependency.

Results

Forty individuals (13 with self-reported shoulder instability and laxity-related shoulder problems and 27 normal shoulder individuals) aged 18–60 were included. Fair (relocation), moderate (load-and-shift, sulcus sign) and substantial (apprehension, surprise, Gagey) intertester reliability were observed across tests (κ 0.39–0.73; 95% CI 0.00 to 1.00). PABAK improved reliability across tests, resulting in substantial to almost perfect intertester reliability for the apprehension, surprise, load-and-shift and Gagey tests (κ 0.65–0.90). Mutual dependencies between each test and self-reported shoulder problem showed apprehension, relocation and surprise to be the most often used tests to characterise self-reported shoulder instability and laxity conditions.

Conclusions

Four tests (apprehension, surprise, load-and-shift and Gagey) out of six were considered intertester reliable for clinical use, while relocation and sulcus sign tests need further standardisation before acceptable evidence. Furthermore, the validity of the tests for shoulder instability and laxity needs to be studied.

Keywords: reliability, shoulder, instability, laxity, clinical test

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of the study is the use of a three-phased standardised study protocol.

Presentation of raw findings increases transparency and interpretation of study findings.

No valid gold standard for including shoulder instability and laxity subjects was used.

A 50/50 prevalence of positive and negative tests for all six tests was not accomplished.

Introduction

Shoulder complaints, affecting shoulder-related quality of life (QoL), are frequent and may be caused by shoulder instability and/or laxity1 due to traumatic or non-traumatic injuries to the shoulder joint.2 The traumatic shoulder instability is mainly prompted by a high-impact injury during sports participation, resulting in a shoulder dislocation, predominantly in anterior direction.3 The non-traumatic shoulder instability is usually related to repetitive overhead activities and/or patients with generalised joint hypermobility or glenohumeral hyperlaxity, often referred to as multidirectional shoulder instability.2 4 5

Irrespectively of aetiology, shoulder instability and laxity is often accompanied by a variety of symptoms, including shoulder discomfort, pain besides glenohumeral subluxations and/or repeated dislocations.6–8 Clinically, shoulder instability and laxity are diagnosed and verified by a group of shoulder pain and instability provoking/relief tests, supplemented by shoulder laxity tests.9 10 The former tests usually include the anterior shoulder instability and laxity tests; apprehension, relocation and surprise, and the laxity tests consisting of the load-and-shift, sulcus sign and Gagey tests.11–13 An ongoing discussion is the use of pain as a diagnostic criterion in diagnosing anterior shoulder instability with the clinical tests apprehension, relocation and surprise.14–16 In one way, it may be a confounding factor, since pain has shown to be less predictive and reliable as a diagnostic criterion.14 On the contrary though, others have suggested that unrecognised and underlying glenohumeral instability may lead to repetitive microtrauma and painful shoulder conditions,15 16 justifying pain as diagnostic criterion when testing for anterior shoulder instability.

Nonetheless, symptoms may become chronic, and lead to reduced work and sports capability,17–19 and with exercise-based management as the most often recommended first-choice treatment.20 21 Hence, early diagnosis using reliable and accurate clinical tests to guide focused treatment is essential. Few studies, though, have investigated the reliability of clinical shoulder instability and laxity tests showing large variations in reliability and with limited methodological quality, hampering interpretation and comparison with other studies.14 22 23

Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the intertester reliability of commonly used clinical shoulder instability and laxity tests and second to describe the mutual dependency for each test evaluated by each tester, in a group of sports-active individuals with and without self-reported shoulder problems.

Materials and methods

Study design

An intertester reliability study was conducted involving two physiotherapists as intertester examiners. A third physiotherapist (study coordinator), not involved in the actual intertester reliability study (test phase), managed all practical aspects during the study period. The Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies, a consensus document on how to report reliability and agreement studies, were followed.24 A standardised protocol for reliability studies, consisting of three phases: preparation and training of clinical tests, overall agreement and test phase (the actual reliability study), was applied.25 Two early career physiotherapists with 6 months clinical experience were involved in the intertester reliability study. A test protocol describing each clinical test was developed and subsequently used by the two testers to practice all tests in order to reach uniformity and mutual agreement in performing and interpreting each test. In the overall agreement phase, the two testers examined 19 individuals (8 affected shoulders and 11 normal shoulders). The two testers were mutually blinded to the health status of the individuals (affected shoulders vs normal shoulders) and also to each other’s test results. Before proceeding to the final study phase, the two testers needed an overall agreement of at least 80% based on findings from the six clinical shoulder tests.25 In the actual intertester reliability test phase, the two testers examined a new group of individuals with affected, respectively, normal shoulders with the six clinical shoulder tests. The procedure was the same as in the agreement phase, meaning that testers were blinded to the health status of the individuals and each other’s test results.

Study subjects

A sample size of at least 40 individuals was targeted based on recommendations for performing clinical reliability studies.25 Sixty-five individuals (women and men (aged 18–60 years)) were recruited and screened for eligibility from Metropolitan University College, Copenhagen, and Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg University Hospital, Copenhagen, resulting in an included number of 13 individuals with instability-related and/or laxity-related shoulder problems (hereinafter referred to as shoulder affected) versus 27 normal shoulder individuals, respectively.

Shoulder affected individuals answering yes to at least one of two questions (“Do you have a sense of shoulder instability?” and “Have you ever had a shoulder injury?”) were eligible for a clinical shoulder examination performed by the study coordinator. The shoulder affected individuals were then included if they present with at least one positive clinical shoulder test out of the following: apprehension, relocation, surprise, load-and-shift, sulcus sign or Gagey. Individuals with normal shoulders were recruited through public advertisements followed by a telephone interview and included if they present with no self-reported shoulder pathology or complaints. In general, any individuals with prior shoulder surgery were excluded. In the actual test phase, individuals completed a short questionnaire with basic demographic details (age, gender, weight, height), in addition to the following: pain level during rest and activity (Numeric Pain Rating Scale),26 shoulder injury ever (yes/no), subjective shoulder instability (yes/no) and sports-related activity (hours/week). Further, all individuals completed the patient-reported Western Ontario Shoulder Instability (WOSI) questionnaire designed to measure shoulder function and QoL in patients with shoulder instability and laxity symptoms.27 The time period between each test phase was approximately 2 weeks, and new subjects were included for each phase. Only the study phase is reported in the current manuscript. The study was exempted for notification to the Danish Health Research Study Board due to the non-invasive and non-treating study design. However, oral and written consent was provided from all individuals and, ethical guidelines were followed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.28

Clinical tests

The clinical shoulder tests consisted of three shoulder joint-provoking tests for anterior shoulder instability (apprehension, relocation and surprise) besides three shoulder laxity tests (load-and-shift, sulcus sign and Gagey) (table 1).11 13 14 22 23 29

Table 1.

Performance and evaluation of the clinical shoulder instability and laxity tests

Verbal introduction:

|

| Clinical tests | Description | Placing of hands, etc | Evaluation (Nominal, dichotom ous data) |

| Apprehension | Individuals placed supine with the shoulder being tested close to the edge of the examination table. Shoulder positioned in 90° of abduction, elbow flexed to 90°. Examiner moves the shoulder into maximal external rotation. |

One hand around the wrist of the individual with the other hand gently placed in front of the shoulder. Elbow supported at the examiner’s thigh. | Subjective or objective presence of apprehension and/or pain? Rated as either positive or negative. |

| Relocation | From the end position of the apprehension test the humeral head is gently forced posteriorly. | Examiner’s fifth finger placed close to the lateral part of the acromion with the wrist positioned anteriorly at the humeral head. | Relief of apprehension and/or pain? Rated as either positive or negative. |

| Surprise | From end position of the relocation test the posteriorly directed force at the humeral head is quickly removed. | Removal of examiner’s wrist from the anterior part of the shoulder. | Subjective or objective reproduction of apprehension and/or pain. Rated as either positive or negative. |

| Load-and-shift | Individual placed supine with scapula resting at the examination table. Humeral head is loaded gently into the glenoid through axial pressure at the elbow. | Examiner’s one hand placed at the olecranon with the individual’s hand positioned between the examiner s torso and elbow. | Humeral head movement evaluated by the use of a four-level laxity scale. |

| Anterior direction | Shoulder positioned in the scapular plane in 90° of abduction with elbow flexed. Humeral head gently shifted in anterior direction. | Examiner ’ s hand placed on top of the shoulder with the fingers on the backside of the glenohumeral head to move it anteriorly. | 0=little to almost no movement 1=humeral head moves up onto the glenoid. 2=humeral head moves beyond the glenoid, but relocates spontaneously once pressure is released. 3=humeral head moves beyond the glenoid and remains dislocated Rated as positive when scored 2 or 3. |

| posterior direction | Shoulder positioned in the scapular plane in 20° of abduction with elbow flexed. Humeral head gently shifted in posterior direction. | Examiner ’ s wrist placed at the anterior part of the humeral head to move it posteriorly. | |

| Sulcus sign | Individuals sitting upright. Shoulder in neutral position (0° rotation). Examiner pulls the distal part of the humerus in a caudal direction. | One hand placed above the epicondyles of humerus. Examiner’s other hand is used to measure the subacromial distance with a ruler. | Rated as positive with measurements exceeding 1 cm. |

| Gagey | Individuals sitting upright. The shoulder girdle is stabilised to prevent the shoulder girdle to elevate while the individual’s arm is passively moved into end range in horizontal abduction. A mirror in front of the individual is used to evaluate the shoulder abduction angle. | Examiner’s Forearm placed on top of the shoulder girdle with the other hand placed around the elbow joint. | Rated as positive with abduction exceeding 105°. |

The apprehension test (table 1, figure 1) was positive if glenohumeral apprehension and/or pain were evoked during testing whereas relief of symptoms with the relocation test (table 1, figure 2) was regarded as a positive test. As for the apprehension, the surprise test (table 1, figure 3) was positive if glenohumeral apprehension and/or pain were evoked during testing. The load-and-shift test (table 1, figures 4 and 5) was rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0 to 3 (best to worst; 0=little glenohumeral movement; 3=humeral head moves beyond the glenoid rim and remains dislocated).12 Also, to enhance mutual agreement between testers when performing the load-and-shift test, only the direction (anterior vs posterior) with most glenohumeral head translation was scored. Sulcus sign (table 1, figure 6) was objectively measured in centimetre (continuous scale) by use of a small ruler according to previously used grading scales as follows: I (<1 cm translation), II (1–2.0 cm translation) or III (>2.0 cm translation).29 Finally, Gagey test (table 1, figure 7) was rated as positive with passive abduction above 105°.13

Figure 1.

Apprehension.

Figure 2.

Relocation.

Figure 3.

Surprise.

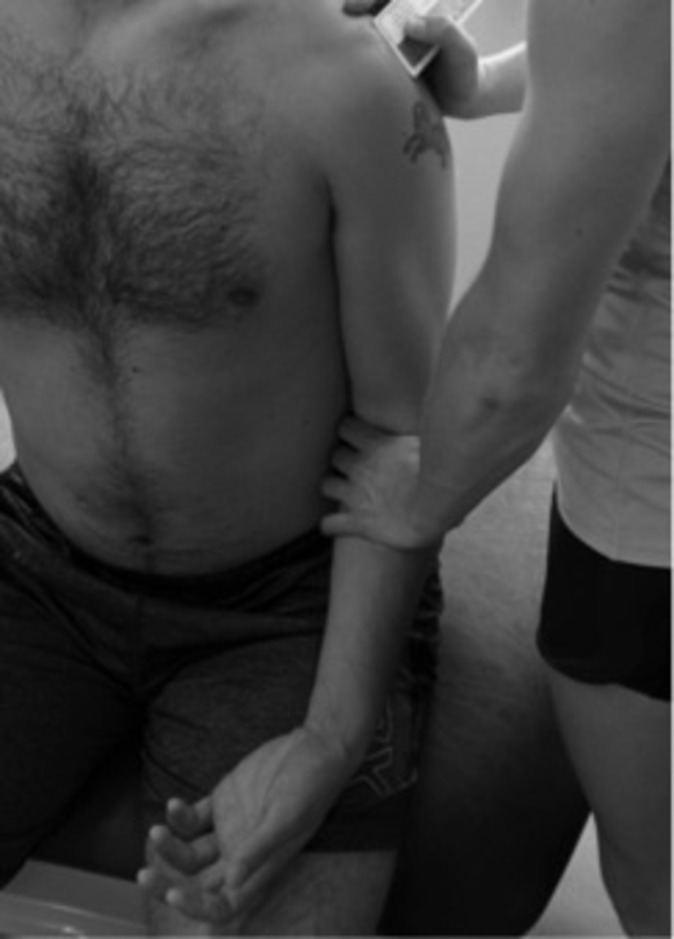

Figure 4.

Load-and-shift—anterior direction.

Figure 5.

Load-and-shift—posterior direction.

Figure 6.

Sulcus sign.

Figure 7.

Gagey.

Statistics

Demographics and descriptive data were tested for normality by visual inspection of histograms and Shapiro-Wilk’s test. Group differences (affected shoulders vs normal shoulders) were tested by Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, whereas Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used for parametric and non-parametric distributed data, respectively.

Apprehension, relocation, surprise and Gagey tests were dichotomous variables whereas the load-and-shift and sulcus sign tests were dichotomised to also allow for nominal statistics. Thus, load-and-shift was rated positive when scored 2 or 3, while for sulcus sign a positive rating was equal to measurements exceeding 1 cm.29 For transparency, data from each test is presented by 2×2 contingency tables besides the use of McNemar’s test for significant between-tester differences. Furthermore, observed and expected agreements are presented along with prevalence and bias30 indexes. Reliability was evaluated with the use of Cohen’s kappa (κ) coefficients including 95% CIs.25 Also, since kappa is sensitive to imbalances in prevalence and bias (eg, if a 50/50 distribution of positive and negative tests cannot be accomplished) the use of prevalence-adjusted and bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK) calculation is a valid supplement to the original kappa values.30 31 By definition, PABAK reflects the ideal situation, thereby accounting for variation of prevalence and bias between testers (as presented in the ‘real’ world).32 PABAK calculation is performed by adjusting for high or low prevalence by computing the average of cells a and d in a cross table, substituting this value for the actual values in those cells. Similarly, an adjustment for bias is achieved by substituting the mean of cells b and c for those actual cell values.30 Finally, the relationship for each tester between the individual tests and the classification (mutual dependency) by self-reported shoulder problems was tested by Cohen’s kappa (κ) coefficients and the characterisation of the groups was tested with Fisher’s exact tests.

The classification system proposed by Landis and Koch was used to interpret reliability as follows: 0.00–0.20 (Slight); 0.21–0.40 (Fair); 0.41–0.60 (Moderate); 0.61–0.80 (Substantial) and 0.81–1.00 (Almost perfect).33

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA), V.22, was used for all statistical analyses, with P<0.05 interpreted as significant.

Results

Characteristics of the participating individuals are presented in table 2. Demographics showed no difference between the individuals with affected shoulders (n=13) and normal shoulders (n=27). Furthermore, both groups (92% and 74%; P=0.18) were relatively active with a weekly participation in sports-related activity for more than 4 hours per week. However, as expected due to the design, affected shoulders had significantly higher pain during activity (4.23 vs 1.44; P=0.02), higher frequency of shoulder injury ever (62% vs <1%; P<0.001), higher subjective shoulder instability (69 vs 11%; P<0.001) and worse total WOSI score (506 vs 136; P=0.001) (table 2).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics, study phase

| Affected shoulders (n=13) | Normal shoulders (n=27) | P value | |

| Sex (women/men) | 8/5 | 21/6 | 0.28 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 28 (9) | 29 (7) | 0.72 |

| Weight (kg),* mean (SD) | 71.0 (12.8) | 74.9 (23.4) | 0.59 |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 174.0 (8.6) | 173.4 (7.9) | 0.82 |

| Pain, rest (NPRS 0–10), mean (SD) | 1.08 (1.44) | 0.41 (1.15) | 0.12 |

| Pain, activity (NPRS 0–10), mean (SD) | 4.23 (2.92) | 1.44 (2.12) | <0.05 |

| Shoulder injury ever, n (%) | 8 (62) | 1 (4) | <0.001 |

| Subjective shoulder instability, n (%) | 9 (69) | 3 (11) | <0.001 |

| Sports-related activity (>4 hours/week), n (%) | 12 (92) | 20 (74) | 0.18 |

| WOSI domains, mean (SD) | |||

| Physical symptoms (0–1000) | 225 (165) | 60 (78) | <0.05 |

| Sports, recreation, work (0–400) | 103 (93) | 24 (47) | <0.05 |

| Lifestyle (0–400) | 58 (57) | 13 (21) | <0.05 |

| Emotions (0–300) | 121 (94) | 39 (49) | <0.05 |

| WOSI total score (0–2100), mean (SD) | 506 (362) | 136 (174) | <0.001 |

*Significance level P<0.05.

NPRS, Numeric Pain Rating Scale; WOSI, Western Ontario Shoulder Instability.

Prevalence of positive tests was especially low for the load-and-shift test (table 3), and significant between-tester differences were found for relocation and sulcus sign tests (P=0.021) (not shown in tables).

Table 3.

Contingency tables with findings from tester A and B

| Apprehension | A | Relocation | A | Surprise | A | ||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||||

| B | Yes | 14 | 4 | B | Yes | 6 | 2 | B | Yes | 14 | 4 |

| No | 3 | 19 | No | 8 | 24 | No | 3 | 19 | |||

| Load-and-shift | A | Sulcus | A | Gagey | A | ||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||||

| B | Yes | 1 | 0 | B | Yes | 7 | 1 | B | Yes | 8 | 3 |

| No | 2 | 37 | No | 9 | 23 | No | 1 | 28 | |||

Reliability varied between κ 0.39–0.73 (95% CI 0.00 to 1.00), indicating fair (relocation; κ 0.39), moderate (load-and-shift, sulcus sign; κ 0.43 and 0.48) and substantial (apprehension, surprise, Gagey; κ 0.65–0.73) reliability (table 4). The prevalence index of all six tests ranged from 0.05 to 0.44, (lowest for load-and-shift, relocation and sulcus; 0.05, 0.28 and 0.30), whereas the bias index ranged from 0.03 to 0.20 (highest for relocation and sulcus). PABAK improved reliability for relocation, load-and-shift, sulcus sign and Gagey test, now corresponding to moderate (relocation and sulcus sign; κ 0.50), substantial (Gagey; κ 0.80) and almost perfect (load-and-shift; κ 0.90) reliability (table 4).

Table 4.

Reliability of six clinical shoulder instability and laxity tests

| Observed agreement | Expected agreement | Prevalence index | Bias index | κ (95% CI) | PABAK | |

| Apprehension | 0.83 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.65 (0.38 to 0.85) | 0.65 |

| Relocation* | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.39 (0.07 to 0.68) | 0.50 |

| Surprise | 0.83 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.65 (0.38 to 0.85) | 0.65 |

| Load-and-Shift | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.48 (0.00 to 1.00) | 0.90 |

| Sulcus sign* | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.43 (0.17 to 0.72) | 0.50 |

| Gagey | 0.90 | 0.62 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.73 (0.46 to 0.94) | 0.80 |

*Significant intertester differences.

PABAK, prevalence-adjusted and bias-adjusted kappa.

The κ values for mutual dependency indicate that apprehension, relocation and surprise tests for both examiners were the most frequently used tests for characterising self-reported shoulder problems (table 5). This was further confirmed by the significant group difference in the presence of positive tests.

Table 5.

Kappa statistics for mutual dependency of the individual tests and self-reported shoulder problems for each tester

| Observed agreement | Expected agreement | Prevalence index | κ | P value (AS/NS) |

|

| Apprehension | |||||

| Examiner A | 0.75 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.003 |

| Examiner B | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.04 |

| Relocation* | |||||

| Examiner A | 0.83 | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.61 | <0.001 |

| Examiner B | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.08 |

| Surprise | |||||

| Examiner A | 0.75 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.003 |

| Examiner B | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.04 |

| Load-and-shift | |||||

| Examiner A | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.03 |

| Examiner B | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.33 |

| Sulcus sign* | |||||

| Examiner A | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.52 |

| Examiner B | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Gagey | |||||

| Examiner A | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.10 |

| Examiner B | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.08 |

*Significant intertester differences.

AS, affected shoulder; NS, normal shoulder.

Discussion

The intertester reliability across the selected six clinical shoulder instability and laxity tests ranged from fair to substantial. Use of PABAK calculations improved intertester reliability to substantial and almost perfect across most tests, except for the relocation and sulcus sign tests. The tests most often used to characterise self-reported shoulder instability and laxity (mutual dependency) were apprehension, relocation and surprise tests.

The intertester reliability for the apprehension, relocation and surprise was higher than, or equivalent, to previously reported results of these tests using the same diagnostic procedures (apprehension and/or pain).23 Specifically for the apprehension and surprise test, the present κ values were somewhat higher than previously reported (0.65 vs 0.44–0.45). The reason for this may be that the current study included both affected and normal shoulder individuals as opposed to only including symptomatic subjects.23 This may have increased subject variation, known to affect reliability positively. Also, PABAK calculations did not affect the overall reliability of the apprehension and surprise tests, probably due to an optimal prevalence index of positive and negative tests (close to 0.50). For the relocation test, the existing intertester reliability was almost similar to previously reported (κ 0.39 vs 0.44),23 however, lower. Apparently, the primary reason for the current poor reliability in relocation was presence of systematic bias between testers, as indicated by the actual raw data (contingency tables) and the statistical significant interexaminer difference. Likewise, systematic bias between testers was also found for the sulcus sign test in the present study. Hypothetically, this may be explained by intertester variability in the force produced to translate the humeral head in posterior (relocation test) or inferior (sulcus sign test) direction, in the current study. This is, however, only speculative and further studies are needed to standardise these tests.

Reliability for the present sulcus sign test was slightly lower than previously reported (κ 0.39 vs >0.50).22 23 The discrepancy in reliability observed may be due to the use of different test positions with participants in the current study sitting upright29 as opposed to a previous lying test position.22 However, due to the presence of systematic bias in both the relocation and sulcus sign test, PABAK did not affect the overall reliability much.

For the load-and-shift test, reliability was relatively low (including wide CI). This may be due to the current low prevalence index below 50%, which is the optimum prevalence in reliability studies.25 However, the present dichotomous rating of the load-and-shift test (meaning that only individuals that could either subluxate or dislocate the shoulder during testing was deemed positive) may have influenced the prevalence of positive tests largely. Therefore, using PABAK, reliability of the load-and-shift test improved considerably (from moderate to almost perfect). Nevertheless, different statistics (kappa vs Intraclass Correlation Coefficients), different scoring systems (dichotomous rating (positive yes/no) versus four-point grading scale (0–3)23 and inclusion of shoulder asymptomatic athletes only22 make comparison across studies difficult.

Finally, reliability of the Gagey test was substantial and PABAK did not affect reliability much due to a nearly optimal prevalence and low bias between testers. Unfortunately, there is no other study to compare with.

Although the current study was designed to investigate reliability, and not diagnostic accuracy, the mutual dependency between the individual tests and self-reported shoulder problems was analysed. It revealed that the tests most often used to characterise those with and without self-reported shoulder instability and laxity (mutual dependency) proved to be the apprehension, relocation and surprise tests. This may indicate a relationship between these tests, which may come as no surprise, since these tests are a continuum of the apprehension test and, thus, closely related.9 Nevertheless, for clinicians it is of interest to specify the clinical characteristics of patients with self-reported shoulder problems. Thus, the current prevalence of positive tests may mirror these characteristics of the included patients and should be taken into consideration in the management of such musculoskeletal conditions. It is recommended to develop and test the clinimetric properties of a more comprehensive test battery for evaluating such self-reported shoulder problems. No prior studies were found addressing mutual dependency of the current tests for shoulder instability and laxity, which hampers comparison.

The present study has several limitations. First, the lack of standardised measurement of the amount of force exerted by the two testers during especially the relocation and sulcus sign test may have limited the current inter-tester reliability. Further standardisation in both performance and interpretation is therefore needed. Also, the current study did not randomise the order of the clinical tests. However, we do not believe this to have biased the reliability of the data, since the same order was used for both testers.

Second, no valid gold standard for classifying shoulder instability and laxity was used. To compensate for this, self-reported confirmation of shoulder-related problems was applied, but this was not reflected in the current WOSI scores, which were relatively low. Lack of a more objective gold standard may have decreased diagnostic accuracy, however, not reliability, which was the primary objective of the present study. Also, in the group with normal shoulders, one individual reported to have had a previous shoulder injury and three individuals reported subjective shoulder instability, which does not comply with the inclusion criteria for being regarded as shoulder healthy in the current study. At the clinical session, a self-reported questionnaire was completed regarding demographic data and historical information. Apparently, in the baseline questionnaire three shoulder healthy individuals answered yes to perceiving instability in their shoulder and one had had a previous shoulder injury, even though they all had reported no shoulder trouble during the telephone inclusion interview. However, as depicted in table 2, WOSI and pain scores in the group with normal shoulders seem not to be influenced severely by these four individuals. Also, recalculations of demographic data and mutual dependency with the revised classification into affected/normal shoulders did not change the mutual dependency of the most frequently used tests for classification into affected/normal shoulders, and neither was kappa and demographics affected (data not shown).

Third, due to a relative short recruitment period besides difficulties in recruiting subjects with shoulder instability and laxity only 13 subjects with an affected shoulder were included. Naturally, this also affected the prevalence of positive and negative test findings meaning that the prevalence of 0.50, as recommended in reliability studies,25 in all six tests was not accomplished. However, to overcome this, PABAK calculations was used and reported along with kappa, to show transparently how data would have been with equal distributions of positive and negative test results. Nevertheless, future studies should use inclusion criteria of more established shoulder instability and laxity conditions, and, if possible, verified by objective criteria as surrogate for a gold standard of shoulder instability and laxity. This may optimise prevalence as well as diagnostic accuracy in studies where this is a further aim.

The strengths of the study are the use of standardised procedures (including blinding to patient status and the use of a three-phased protocol for conducting reliability studies). Also, presentation of raw data, using contingency tables, along with kappa and PABAK values, increases data transparency and improves interpretation of the reliability study.

Conclusions

This study showed acceptable intertester reliability for four of six clinical shoulder instability and laxity tests in relatively sports active individuals with and without self-reported shoulder problems. However, relocation and sulcus sign tests need further standardisation before being recommended for use in clinical practice. Based on the frequency and mutual dependency of the current tests, especially apprehension and surprise tests seem important in the characterisation of self-reported shoulder problems. Future research on the validity of tests for shoulder instability and laxity is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Physiotherapists Rasmus Fitzner, Pernille Madsen and Jacob Hansen from Metropolitan University College, Copenhagen, Denmark for recruitment and testing of study participants. Furthermore, a special thanks to Bispebjerg Frederiksberg University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark for providing facilities for data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: HE, KGI, CML and BJ-K conceived and designed the study and interpreted the results. HE and BHK recruited study participants and collected data. HE performed the statistical analysis. HE drafted the manuscript with KGI, CML, BHK and BJ-K contributing to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. HE is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by Region of Southern Denmark’s Research fund and The Danish Rheumatism Association.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Luime JJ, Koes BW, Hendriksen IJ, et al. . Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol 2004;33:73–81. 10.1080/03009740310004667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrar NG, Malal JJ, Fischer J, et al. . An overview of shoulder instability and its management. Open Orthop J 2013;7:338–46. 10.2174/1874325001307010338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goss TP. Anterior glenohumeral instability. Orthopedics 1988;11:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron KL, Duffey ML, DeBerardino TM, et al. . Association of generalized joint hypermobility with a history of glenohumeral joint instability. J Athl Train 2010;45:253–8. 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chahal J, Leiter J, McKee MD, et al. . Generalized ligamentous laxity as a predisposing factor for primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:1238–42. 10.1016/j.jse.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodson CC, Cordasco FA. Anterior glenohumeral joint dislocations. Orthop Clin North Am 2008;39:507–18. 10.1016/j.ocl.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaggi A, Lambert S. Rehabilitation for shoulder instability. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:333–40. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.059311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Reinold MM. Non-operative rehabilitation for traumatic and atraumatic glenohumeral instability. N Am J Sports Phys Ther 2006;1:16–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hegedus EJ, Goode AP, Cook CE, et al. . Which physical examination tests provide clinicians with the most value when examining the shoulder? Update of a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:964–78. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganestam A, Attrup ML, Hølmich P, et al. . ’Evaluation of clinical practice of shoulder examination amon ten experienced shoulder surgeons'. Journal of Orthopaedic Research and Physiotherapy 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luime JJ, Verhagen AP, Miedema HS, et al. . Does this patient have an instability of the shoulder or a labrum lesion? JAMA 2004;292:1989–99. 10.1001/jama.292.16.1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzannes A, Murrell GA. Clinical examination of the unstable shoulder. Sports Med 2002;32:447–57. 10.2165/00007256-200232070-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagey OJ, Gagey N. The hyperabduction test. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:69–74. 10.1302/0301-620X.83B1.10628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo IK, Nonweiler B, Woolfrey M, et al. . An evaluation of the apprehension, relocation, and surprise tests for anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:301–7. 10.1177/0095399703258690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silliman JF, Hawkins RJ. Classification and physical diagnosis of instability of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993:7–19. 10.1097/00003086-199306000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavallo RJ, Speer KP. Shoulder instability and impingement in throwing athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:18–25. 10.1097/00005768-199804001-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsen FA, Zuckerman JD. Anterior glenohumeral instability. Clin Sports Med 1983;2:319–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson CM, Howes J, Murdoch H, et al. . Functional outcome and risk of recurrent instability after primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in young patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:2326–36. 10.2106/JBJS.E.01327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Kampen DA, van den Berg T, van der Woude HJ, et al. . Diagnostic value of patient characteristics, history, and six clinical tests for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013;22:1310–9. 10.1016/j.jse.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warby SA, Pizzari T, Ford JJ, et al. . The effect of exercise-based management for multidirectional instability of the glenohumeral joint: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014;23:128–42. 10.1016/j.jse.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson K, Growse A, Korda L, et al. . The effectiveness of rehabilitation for nonoperative management of shoulder instability: a systematic review. J Hand Ther 2004;17:229–42. 10.1197/j.jht.2004.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy AS, Lintner S, Kenter K, et al. . Intra- and interobserver reproducibility of the shoulder laxity examination. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:460–3. 10.1177/03635465990270040901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzannes A, Paxinos A, Callanan M, et al. . An assessment of the interexaminer reliability of tests for shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2004;13:18–23. 10.1016/j.jse.2003.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kottner J, Audigé L, Brorson S, et al. . Guidelines for reporting reliability and agreement studies (GRRAS) were proposed. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:96–106. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patijn J, Remvig L. "Reproducibility And Validity 2007-Protocol Formats For Diagnostics Procedures In Manual/Musculoskeletal Medicine." In, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, et al. . Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis 1978;37:378–81. 10.1136/ard.37.4.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkley A, Griffin S, McLintock H, et al. . The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability. The western ontario shoulder instability index (WOSI). Am J Sports Med 1998;26:764–72. 10.1177/03635465980260060501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2000;284:3043–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bahk M, Keyurapan E, Tasaki A, et al. . Laxity testing of the shoulder: a review. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:131–44. 10.1177/0363546506294570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther 2005;85:257–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:423–9. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90018-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoehler FK. Bias and prevalence effects on kappa viewed in terms of sensitivity and specificity. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:499–503. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00174-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.