Abstract

Background: Increasing bacterial infections as well as a rise in bacterial resistance call for the development of novel and safe antimicrobial agents without inducing bacterial resistance. Nanoparticles (NPs) present some advantages in treating bacterial infections and provide an alternative strategy to discover new antibiotics. Here, we report the development of novel self-assembled fluorescent organic nanoparticles (FONs) with excellent antibacterial efficacy and good biocompatibility.

Methods: Self-assembly of 1-(12-(pyridin-1-ium-1-yl)dodecyl)-4-(1,4,5-triphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)pyridin-1-ium (TPIP) in aqueous solution was investigated using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The bacteria were imaged under a laser scanning confocal microscope. We evaluated the antibacterial efficacy of TPIP-FONs in vitro using sugar plate test. The antimicrobial mechanism was explored by SEM. The biocompatibility of the nanoparticles was examined using cytotoxicity test, hemolysis assay, and histological staining. We further tested the antibacterial efficacy of TPIP-FONs in vivo using the S. aureus-infected rats.

Results: In aqueous solution, TPIP could self-assemble into nanoparticles (TPIP-FONs) with characteristic aggregation-induced emission (AIE). TPIP-FONs could simultaneously image gram-positive bacteria without the washing process. In vitro antimicrobial activity suggested that TPIP-FONs had excellent antibacterial activity against S. aureus (MIC = 2.0 µg mL-1). Furthermore, TPIP-FONs exhibited intrinsic biocompatibility with mammalian cells, in particular, red blood cells. In vivo studies further demonstrated that TPIP-FONs had excellent antibacterial efficacy and significantly reduced bacterial load in the infectious sites.

Conclusion: The integrated design of bacterial imaging and antibacterial functions in the self-assembled small molecules provides a promising strategy for the development of novel antimicrobial nanomaterials.

Keywords: antibacterial materials, self-assembly, aggregation-induced emission, bacterial imaging, antimicrobial activity.

Introduction

Despite the availability of antibiotics, bacterial infections remain one of the major causes of deaths worldwide. This is due to the emergence of bacterial resistance which has become a global health challenge threatening public health 1. In the United States alone, more than 2 million people suffer from antibiotic-resistant infections each year, and at least 23,000 people die as a result of these infections 2. The bacterial resistance can be attributed to various mechanisms, such as activation of antibiotic efflux pumps, inactivation of antibiotic degradation enzymes, decreased antibiotic permeation and formation of biofilm 3. To treat drug-resistant bacterial infections, numerous antimicrobial materials have been developed recently, such as cationic polymers 4-7, antimicrobial peptides 8-13, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) 14-19, and metal-containing NPs 20-22. Among these, cationic polymers have some beneficial properties, such as broad-spectrum antibacterial features and the ability for easy functionalization. However, they can also cause a certain degree of hemolysis in vivo and exert some cytotoxicity to human cells inhibiting their application as an antibacterial agent 23, 24. Although antimicrobial peptides (AMP) are efficient, their application is still restricted because of the high cost, limited stability (when composed of L-amino acids), poor photolytic stability, and poorly-studied toxicology and pharmacokinetics 25, 26.

AgNPs are popular antimicrobial inorganic NPs and show a higher antimicrobial activity against multidrug resistant (MDR) bacteria 27, 28. However, the toxic side effects of AgNPs on humans, like spasms, gastrointestinal disorders, and even death, limit their therapeutic application 17, 29. Moreover, studies indicated that AgNPs could cause potential immunotoxicity 30, 31. Other metal-containing NPs also have limitations for antibacterial treatments in vivo due to the accumulation of toxicity. Therefore, it is critical to design and synthesize innovative antibacterial materials with efficient activity and decent biocompatibility for clinical treatments.

Besides countering the issue of drug-resistance, developing a new method for quick bacterial detection is also important for microbial infection treatment and controlling the spread of disease 32, 33. Gram staining has been the standard method to differentiate bacterial species into two large groups, gram-positive and gram-negative 34. However, this method is prone to generate false positive results 35. Other methods, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) 36, 37 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 38-39 with high sensitivity and reproducibility, have been reported for microbial detection. Nevertheless, these technologies require lengthy and laborious procedures 40 thereby delaying the critical diagnosis and response to infectious emergencies. Recently, fluorescence assay has been demonstrated as an effective method to detect bacteria in different biological environments 41-47. For example, antibiotics(vancomycin and daptomycin)-modified fluorophores and nanoparticles are synthesized for targeted bacterial detection 12, 41, 48-50. Multidrug resistant bacteria, however, would not be detected by the antibiotic-modified probes thus leading to false negative results. Furthermore, the administration of sub-lethal doses of antibiotics may promote unexpected antimicrobial resistance.51

NPs hold great potential for both antibacterial application and rapid detection of pathogens due to their unique physicochemical properties that feature a large surface area to volume ratio and a versatile surface chemistry 52-55 Specifically, the large surface area of nanomaterials can enhance their interactions with microbes. Also, NPs are believed to be more effective and less likely to induce resistance in most drug-resistant cases, since their antimicrobial properties involve direct contact with the bacterial cell wall, instead of penetrating into the cell, making most bacterial antibiotic-resistant mechanisms irrelevant 56-59. Therefore, the nano-antibacterial agents may be less prone to induce resistance in bacteria than traditional antibiotics.

Molecular self-assembly is a spontaneous association of individual components into well-ordered structures assisted by non-covalent interactions including electrostatic interaction, hydrogen bonding, π-π interaction, charge-transfer interactions, and hydrophobic effect 60, 61. Among the reported self-assembled nano-materials, small molecule self-assembled nanomaterials have received much attention for their photo-stability, biocompatibility, diversity, and flexibility in molecular design 62-64. However, to the best of our knowledge, the usage of small molecule self-assembled nanomaterials in diagnostic and therapeutic platforms against microbial infections is still lacking.

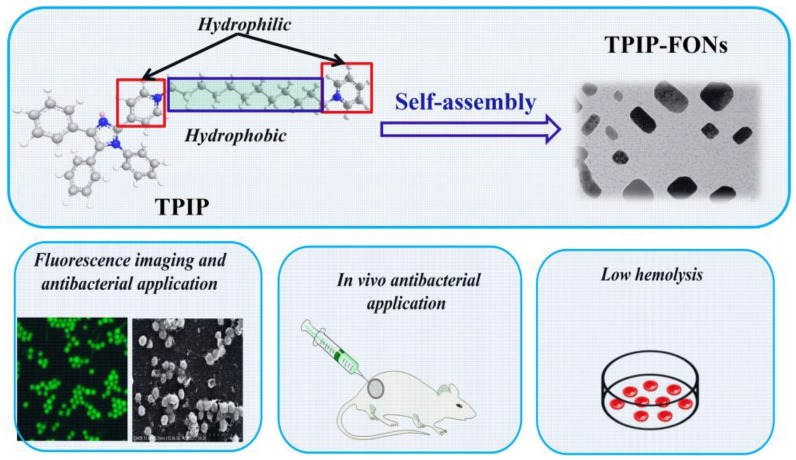

Recently, based on tetraphenyl imidazole-cored molecular rotors, our group developed a novel series of AIEgens with good photo-stability, high water solubility, and good biocompatibility. It was reported that tetraphenyl imidazole derivatives could self-assemble into nanoparticles for chemical sensing or imaging of gram-positive bacterial strains 65, 66. In this study, inspired by the antimicrobial activity of the imidazole moiety 67-69 and the excellent antibacterial effect of quaternary ammonium compounds 70-72, we designed a cationic bola-type small molecule by combining tetraphenyl imidazole core with quaternary ammonium group (TPIP) for fast microbial detection and bacterial infection treatment. TPIP is composed of three components (Scheme 1): (1) the substituted imidazole is used as the AIEgen with antibacterial activity, (2) the alkyl chain can tune the spatial positioning of the positive charge in molecules and reduce the toxicity of small cationic molecules, and (3) the pyridinium salt group serving as the hydrophilic terminal group has an antimicrobial effect. This bola-type molecule can self-assemble into nanoparticles (TPIP-FONs) in aqueous solution without fluorescence, while it emits intense green fluorescence after bonding with gram-positive bacteria. The in vitro antimicrobial activity studies revealed that TPIP-FONs have excellent antibacterial activity. The low cytotoxicity and negligible hemolysis activity of TPIP-FONs allowed us to treat bacterial infections in vivo. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the small molecule self-assembled nanomaterials enabling bacterial imaging and antibacterial action.

Scheme 1.

Schematics of the structure of TPIP and its self-assembled nanoparticles (TPIP-FONs) with low hemolysis and the antibacterial application in vitro and in vivo.

Experimental section

Materials and instruments

Vitamin B1, benzaldehyde, aniline (99.5%), and 1, 12-dibromo dodecane (98%) were purchased from Energy Chemical Co., Ltd (China). Two compounds (4-pyridine carboxaldehyde (98%) and pyridine) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (China). Mannitol Salt Agar was purchased from Beijing Land Bridge Technology Co., Ltd (China). All bacterial strains were acquired from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), USA. Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium, fetal bovine serum, penicillin G (100 U mL-1), streptomycin (100 U mL-1) and 0.25% trypsin solution were purchased from Gibco (USA). AT-II cells and L02 cells were from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences. Ultrapure water was obtained by using a Millipore water purification system (Merck Millipore, Germany). Other chemical reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial chemical suppliers and used without further purification.

UV-vis absorption spectra were performed on a UV-2550 scanning spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). Fluorescent spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu RF-5301 equipped with a 1 cm quartz cell. Dynamic light scattering measurements were performed at 25 oC on Zestier Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd, UK). The morphology of TPIP-FONs was characterized by JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The morphology of bacteria was characterized by S-3400N scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were measured on a Bruker AVII-400 MHz or 500 MHz spectrometers with chemical shifts reported in ppm (in DMSO-d6 or CDCl3, TMS as internal standard). HRMS was obtained on an Orbitrap Velos Pro LC-MS spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, American).

Preparation of TPIP-FONs

A stock solution of TPIP (1×10-3 M) was prepared from dimethyl sulfoxides. Thirty microliters of this solution was added to phosphate buffer (3 mL) maintained at pH 7.4, and the solution (10 μM) was kept at room temperature. Nanoparticles formation was confirmed by DLS and TEM analyses for which the solution was dropped casting on freshly cleaved mica surface or carbon-coated copper grid (400 mesh), respectively, after drying under vacuum.

Bacterial cultures and staining assays

A single colony of bacteria S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, Streptococcus, A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, or E. coli on solid Luria-Bertani (LB) medium was transferred to 10 mL of liquid culture medium and grown at 37 °C for 12 h with 180 rpm rotation. The concentration of bacteria was determined by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Subsequently, 109 colony forming unit (CFU) (OD600 = 109 CFU mL-1) of bacteria was transferred to a 1.5 mL EP tube. Bacteria were harvested by centrifuging at 5000 rpm for 3 min. After removal of the supernatant, 500 µL TPIP-FONs were added to the EP tube with PBS, making the final concentration of TPIP-FONs to 20×10-6 M). After vortexing to disperse, the bacteria were incubated at room temperature for 10 min. S. aureus samples were diluted into various concentrations (from 3×107 to 3×108 CFU mL-1) by using sterile saline, then 10 µL TPIP-FONs (50×10-6 M) was added to the 90 µL bacterial solutions, and incubated for 10 min. The fluorescence of solutions was recorded by fluorescence spectrophotometer.

Bacterial imaging

For fluorescence images, 10 µL of the stained bacterial solution was transferred to a glass slide and covered with a coverslip. The bacteria were imaged under a laser scanning confocal microscope using 400-440 nm excitation filter, and 490 nm long pass emission filters.

Kirby-Bauer antibiotic testing

The antibacterial efficacy of TPIP-FONs against P. aeruginosa or S. aureus was examined by Kirby-Bauer antibiotic testing. P. aeruginosa or S. aureus were diluted to approximately 1.0×107 CFU mL-1 with LB broth, and 50 µL of the bacterial suspension was inoculated on LB agar plates. The same disk containing different concentrations of TPIP-FONs solution was placed at the center of the plates, and cultured overnight at 37 oC. The diameter of the inhibition zone around the disk indicated the antibacterial activity.

Bacterial kinetic test: Bacteria in the log phase (1×106 to 1×107 CFU mL-1) treated with different concentrations of TPIP-FONs were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured at 37 °C. During the culture process, the optical density at 600 nm of each well was monitored at different times.

Mannitol salt agar plate

The TPIP-FONs were mixed with mannitol salt agar medium at various concentrations (0-8 μg/mL). After the agar was cooled to room temperature, S. aureus suspensions (1×105 to 1×106 CFU mL-1) were plated onto the above agar plates and incubated at 37 °C.

SEM characterization of bacteria

The bacteria in the logarithmic phase were treated with TPIP-FONs (2 μg/mL) for 2 h at 37 °C on a shaker bed at 200 rpm. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 3 min and washed with sterile saline three times, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4 °C and dehydrated with a sequential treatment of 50%, 70%, 85%, 90%, and 100% ethanol for 10 min each, and gold sputter-coated and observed by SEM.

Rats infection model: SD rats (200-230 g in weight) were purchased from the Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. (Hunan, China). All animal experimental procedures were performed according to the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation with the approval of the animal care committee of Central South University. To evaluate the in vivo antibacterial effect of TPIP-FONs, the S. aureus-infected rat model was developed. 200 µL of log-phase S. aureus cells (1×109 CFU mL-1) resuspended in sterile saline was injected into the rats. Two days after infection, 100 µL PBS with or without 200 μg/mL of TPIP-FONs was injected into the infectious site once a day. All rats were sacrificed after 2 days of treatment, and the infectious tissues and major organs (heart, liver, lung, kidney, and spleen) were processed for further analysis. To determine the number of bacteria, the infectious tissues were separated and homogenized in normal saline (0.5 mL). Aliquots of diluted (1:10, 1:100 and 1:1000) homogenized tissues were plated on mannitol salt agar plates (six plates per sample), and the number of colonies was counted.

Hemolysis assay

Hemolysis assay was conducted on RBCs. Human whole blood (2 mL) was donated by a healthy male volunteer. RBCs were centrifuged for five times and re-suspended using 10 mL PBS. 0. 4 mL of different concentrations (0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 µg mL-1) of TPIP-FONs dissolved in PBS were added to 0.1 mL of RBC solution. After incubation at 37 °C for 2 h, the supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The absorbance value of the supernatant was measured at 570 nm. RBCs in PBS and water were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. All samples were prepared in triplicates. The hemolysis percentage was calculated using the following formula:

| Hemolysis (%) = (sample absorbance - negative control absorbance)/(positive control absorbance - negative control absorbance) ×100. |

Histological staining

All SD rats were randomly divided into two groups. PBS-treated (control) group and TPIP-FONs-treated group (100 μL, 200 μg/mL) once daily. After administration for 2 d, major organs were separated and fixed in 4% formalin solution, then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined using a digital microscope.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and characterization of TPIP

The bola-type molecule TPIP was synthesized as shown in Figure 1a. 2-hydroxy-1,2-diphenylmethane (compound 1) was prepared by thiamine hydrochloride-mediated benzoin condensation reaction. Oxidation of compound 1 afforded the corresponding benzil (compound 2). The tetraphenyl imidazole (compound 3) was obtained by a one-pot two-steps multicomponent reaction of 4-pyridinecarboxaldehyde, primary aromatic amine, benzyl, and ammonium acetate. Compound 3 was reacted with 1, 12-dibromo dodecane to yield the intermediate 4. The reaction of this intermediate with pyridine afforded the final TPIP. All compounds were characterized by NMR and MS.

Figure 1.

(a) Synthetic route of the bola-type molecule TPIP. (b) Fluorescent spectra of TPIP in THF-water mixtures with different THF fractions (ƒw). (c) Plots of fluorescent intensity vs. THF fractions of TPIP. (d) DLS analysis of TPIP (10 μM) assemblies obtained from water. (e) TEM analysis of TPIP (10 μM) rectangular assemblies obtained from water.

To determine the characteristics of AIE, we used water and THF as the solvent and non-solvent. As shown in Figure 1b and Figure 1c, TPIP showed weak fluorescence in aqueous solution and fluorescent quantum efficiency (φF) was 0.023. While the THF ƒw > was 80 (fraction by volume %), the emission of TPIP dramatically increased. This phenomenon resulted from the aggregations formed by TPIP which led to blocking the non-radiative relaxation pathways of its excited state, indicating that TPIP had a significant AIE effect. It is well known that some parameters, such as conductivity, surface tension, and fluorescence intensity of the solution significantly change around the critical aggregation concentration (CAC) 73, 74. Therefore, CAC value of TPIP could be measured readily by the method of conductivity and fluorescence variation. When TPIP was dissolved in water, the conductivity (k), as a function of the concentration of TPIP, was measured to determine its CAC in water (Figure S1a). The conductivity increased linearly as the concentration of TPIP increased up to 20 µM. However, when the concentration was higher than 20 µM, the plot was linear with a lower slope. The two linear segments in the curve and a sudden decrease of the slope indicated that the CAC value was approximately 20 µM. The fluorescence intensity at 500 nm versus the corresponding TPIP concentration is plotted in Figure S1b. The fluorescence of TPIP gradually arose with the increase in the concentration. Obviously, one inflection point appeared at around 20 µM (equal to the CAC obtained from the conductivity test), thus suggesting a change in the aggregation state.

Next, we investigated the photo-physical characteristics of TPIP-FONs. As shown in Figure S2a, the maximum absorption wavelength of TPIP-FONs was at 385 nm, and the TPIP-FONs solution exhibited weak fluorescence emission (Φ=0.023) (Figure S2b). The aggregate of TPIP had weak emission because of its loosely packed characteristics with enough free volume to consume radiative energy by intramolecular rotation. Subsequently, the self-assembled behavior of TPIP in aqueous solution was investigated by using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The DLS studies showed that the aggregates of TPIP (10 µM) had an average diameter of 313 nm (PDI: 0.296) and a broad size distribution (Figure. 1d) indicating that these aggregates may not be simple spherical assemblies. Furthermore, the TEM experiments were conducted to assist the visualization of nanostructures self-assembled from TPIP in water. Figure 1e shows a rectangular structure of the aggregates and the average diameter of 100-300 nm for TPIP-FONs. This aggregate of TPIP had weak emission owing to its loosely packed characteristics and still had enough free volume to consume radiative energy by the intramolecular rotation.

Detection of bacteria

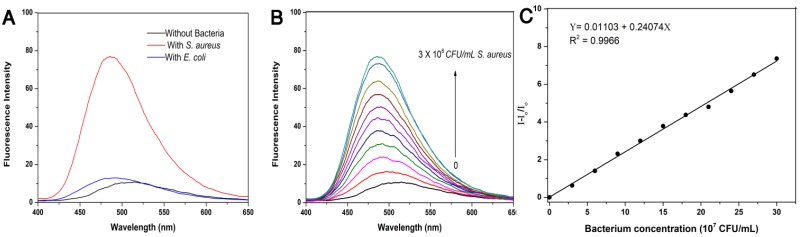

Given that TPIP has two quaternary ammonium structures with a positive charge while the cell wall of bacteria is negatively charged, we hypothesized that the electrostatic interaction between TPIP and the bacterial cells might alter the aggregation state of TPIP resulting in fluorescence emission, which could be used for the detection of bacteria. We, therefore, explored the fluorescence sensing ability of TPIP-FONs towards different species of bacteria. As shown in Figure 2a, the solution of TPIP-FONs exhibited weak fluorescence emission in the absence of bacteria while, upon addition of S. aureus cells, 8 times higher emission intensity was observed than that of TPIP-FONs alone. In sharp contrast, the fluorescence intensity of the solution was almost unchanged in the presence of the gram-negative E. coli cells. The selective “turn-on” detection was due to the strong interaction between TPIP-FONs and cell walls of gram-positive bacteria, S. aureus. Since the cell wall is mainly composed of negatively charged teichoic acids and a thick peptidoglycan layer, they are more likely to bind to quaternary ammonium compounds than gram-negative bacteria which is composed of a lipopolysaccharide-linked outer membrane 71, 75. We then investigated the fluorescence response of TPIP-FONs to different concentrations of S. aureus. As shown in Figure 2b, upon addition of S. aureus cells, the fluorescence intensity constantly increased with the maximum emission wavelength blue-shifted from ~510 nm to ~490 nm. Importantly, the fluorescence intensity of TPIP-FONs showed an almost linear relationship between S. aureus concentrations in the range of 3×107 to 3×108 CFU mL-1 (Figure 2c). The limit of detection was determined to be 5.2×105 CFU mL-1 which was calculated by 3σ/k (σ is the standard deviation of blank measurements, n=11, and k is the slope of the linear equation). We performed additional experiments and detected the bacteria from 0 to 3×107 CFU mL-1. As shown in Figure S3, the fluorescence intensity of TPIP-FONs showed an almost linear relationship between S. aureus concentrations in the range of 9×105 to 3×107 CFU mL-1. The R2 presented a better linear relationship in the wide range as compared to the short range. The fluorescence “turn-on” detection of bacteria with good accuracy and large linear relationship region enabled its further application for detecting bacteria in the clinic.

Figure 2.

(a) Fluorescence emission spectra of TPIP-FONs (5 μM) with/without 3×108 CFU mL-1 of S. aureus or E. coli. Excitation wavelength: 380 nm. (b) Fluorescence intensity of TPIP-FONs aqueous solution upon addition of varying amounts of S. aureus cells. (c) Fluorescence intensity (I-Io/Io) at 490 nm against concentrations of S. aureus cells.

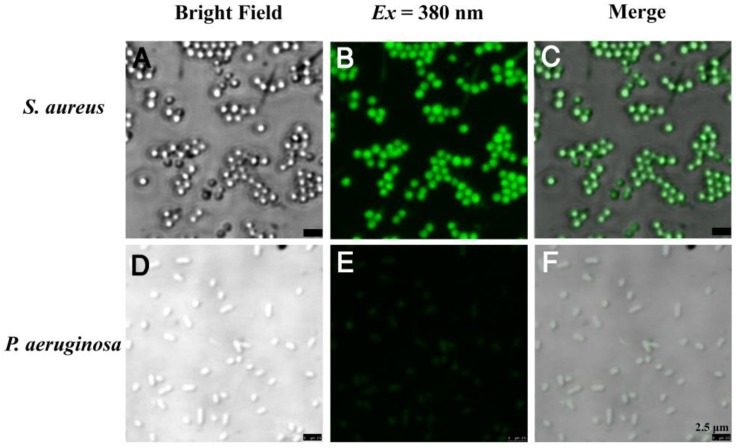

The bola-type amphiphilic molecule TPIP contained positively charged amines and the long alkyl chain signifying hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity, respectively. At the concentrations below CAC, TPIP-FONs showed very weak fluorescence in aqueous solution, and were able to turn on their fluorescence after binding with gram-positive bacteria. Due to their AIE characteristics, the unbound molecules of TPIP exhibited faint fluorescence and only those bounded to bacteria lit up. This unique property provides an opportunity for the direct identification of bacteria without washing process. We next applied TPIP-FONs for imaging the bacteria. As shown in Figure 3, TPIP-FONs could be used to selectively image the gram-positive S. aureus bacteria while the gram-negative P. aeruginosa bacteria were rarely stained. Furthermore, we also used TPIP-FONs for imaging three additional gram-positive (S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, and Streptococcus) and three gram-negative bacteria (A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, and E. coli). The results shown in Figure S4 and Figure S5 further confirmed that TPIP-FONs specifically stained gram-positive bacteria. This selective imaging of gram-positive bacteria was due to the different cell wall structures of gram-positive and negative bacteria.

Figure 3.

Confocal fluorescence images of (a-c) S. aureus and (d-f) P. aeruginosa bacteria after incubation with 5 μM TPIP-FONs for 10 min and visualized under bright field; excitation at 380 nm, and the overlay.

Antimicrobial activity of TPIP-FONs in vitro

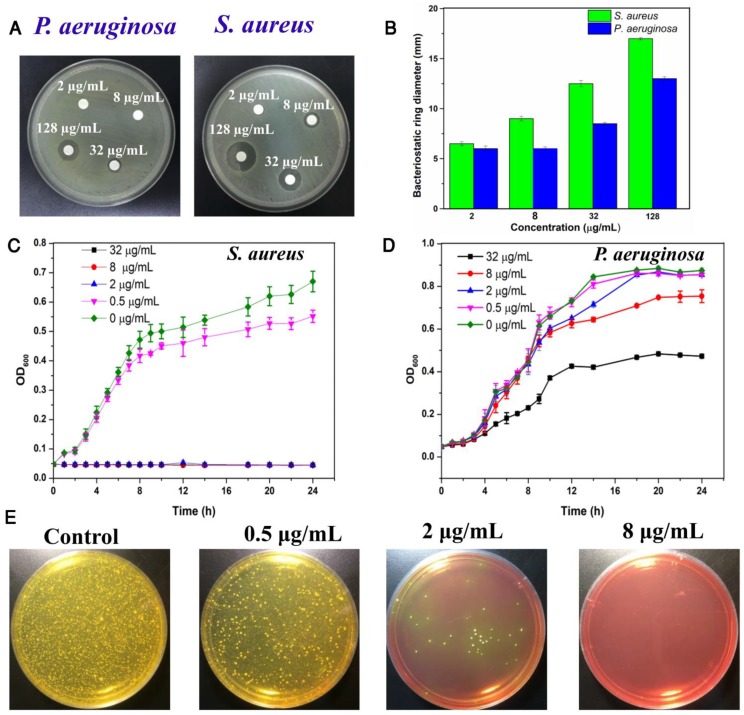

Considering the excellent antibacterial activity of quaternary ammonium and imidazole compounds, we hypothesized that TPIP-FONs has potent antibacterial activity. To this end, the activity of TPIP-FONs was measured by agar diffusion test, a test of the antibiotic sensitivity of bacteria. Figure 4a and Figure 4b show the results of inhibition zones treated with different concentration of TPIP-FONs for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, respectively. When the concentration of TPIP-FONs was 8 μg mL-1, the inhibition zone for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus was 0.6 cm and 0.9 cm, respectively. The concentration of TPIP-FONs was as low as 32 μg mL-1 showed significant antibacterial activity against S. aureus (The inhibition zone close to 1.25 cm). However, at the same concentration, the inhibition zone for P. aeruginosa was only 0.85 cm. Also, when the concentration of TPIP-FONs reached 128 μg mL-1, the antibacterial ring diameter of S. aureus (1.7 cm) was significantly larger than that of P. aeruginosa (1.3 cm). The results suggested that TPIP-FONs have better antibacterial activity against S. aureus than P. aeruginosa because gram-positive bacteria have more negative charge 77 resulting in the stronger interaction with TPIP-FONs than gram-negative bacteria.

Figure 4.

(a) Inhibition zones of different concentrations of TPIP against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. (b) The bacteriostatic ring diameters of different samples. (c) Inhibitory effect of different concentrations of TPIP on the growth of S. aureus as a function of incubation time. (d) Inhibitory effect of different concentrations of TPIP on the growth of P. aeruginosa as a function of incubation time. (e) Photographs of the agar plates of S. aureus after treatments with different concentrations of TPIP.

To quantitatively evaluate the antibacterial activity of TPIP-FONs, the growth kinetics of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in liquid media were studied. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600 is recognized as the characteristic peak for determining the bacterial number) at different incubation times. The results showed that TPIP-FONs could inhibit the growth of S. aureus within 24 h at a concentration of 2 µg mL-1 (Figure 4c). In contrast, even at a concentration of 32 µg mL-1, the growth of P. aeruginosa was not inhibited for 24 h (Figure 4d). To further explore its antibacterial activity, we also measured the growth kinetics of E. coli and C. albicans. In case of E. coli, when the concentration of TPIP-FONs reached 8 µg mL-1, the bacterial growth was significantly inhibited within 24 h (Figure S6). The growth of C. albicans was also completely inhibited by 2 µg mL-1 TPIP-FONs (Figure S7). The MICs (minimum inhibitory concentration) of TPIP-FONs against different bacteria are shown in Table S1. The results further confirmed that TPIP-FONs exhibited an excellent antibacterial activity which could be observed with naked eyes. The agar plate experiments for S. aureus were also carried out (Figure 4e). Compared to the group without treatment, 0.5 µg mL-1 of TPIP-FONs showed a slight inhibitory effect on S. aureus. When the concentration of TPIP-FONs was increased to 2 µg mL-1, the number of S. aureus colonies significantly decreased, but some bacteria were still alive. In the presence of 8 µg mL-1 TPIP-FONs, S. aureus was killed effectively and almost no colony formed on the plate. These results proved the excellent antibacterial efficacy of TPIP-FONs against S. aureus.

Antimicrobial mechanism

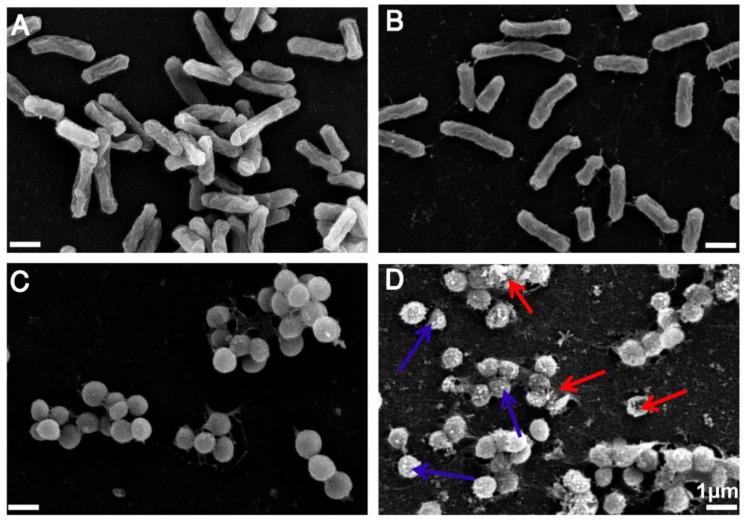

Having demonstrated the excellent antimicrobial activity of TPIP-FONs, we further investigated their antibacterial mechanism. To this end, we tested the morphological changes of E. coli and S. aureus before or after incubation with TPIP-FONs (2 µg mL-1) by SEM observations. As shown in Figure 5a and Figure 5c, both E. coli and S. aureus without TPIP-FONs treatment exhibited integrity of the membrane structure with a smooth surface. After incubation with TPIP-FONs for 2 h, the cell walls of S. aureus became wrinkled and damaged, and the leakage of intracellular contents could be observed (Figure 5d). Moreover, some outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) formed on the cell membrane after incubation with TPIP-FONs, which could be ascribed to the instability of cell membranes. 79 The formation of OMVs was also observed in bacteria treated with cationic antibiotics such as polymyxin and gentamicin. 78, 79 In contrast, after the treatment of E. coli cells with TPIP-FONs at the same concentration, almost no morphological changes could be observed between treated and untreated cells (Figure 5a and 5b). These results indicated that TPIP-FONs could exhibit better antibacterial activity against S. aureus than E. coli. Normally, gram-positive bacteria have a single phospholipid membrane and a thicker cell wall composed of peptidoglycan, whereas gram-negative bacteria are encapsulated by two cell membranes and fairly thin peptidoglycan. Therefore, quaternary ammonium compounds and other membrane-targeting antiseptics tend to exhibit decreased activity against gram-negative species. 70 The ability of bacterial cell wall disruption enables TPIP-FONs to effectively combat bacterial drug resistance, making it difficult for bacteria to develop drug tolerance. We believe that the possible antimicrobial mechanism of TPIP-FONs is through the following sequential events. First, electrostatic interactions between the positively-charged pyridinium head and the negatively-charged teichoic acids are followed by the permeation of alkyl chain of TPIP into the intramembrane region of gram-positive bacteria. Subsequently, increase of microbial cell membrane permeability, osmotic damage, and leakage of cytoplasmic material out of the cell eventually lead to cell death.

Figure 5.

(a) SEM images of E. coli without treatment of TPIP-FONs. (b) SEM images of E. coli with the treatment of 2 µg/mL TPIP-FONs for 2 h. (c) SEM images of S. aureus without treatment of TPIP-FONs. (d) SEM images of S. aureus with the treatment of 2 µg/mL TPIP-FONs for 2 h. Red arrows indicate the damage of bacterial cells. Blue arrows show the formation of outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) on the surface of bacteria cells.

In vivo antimicrobial activity

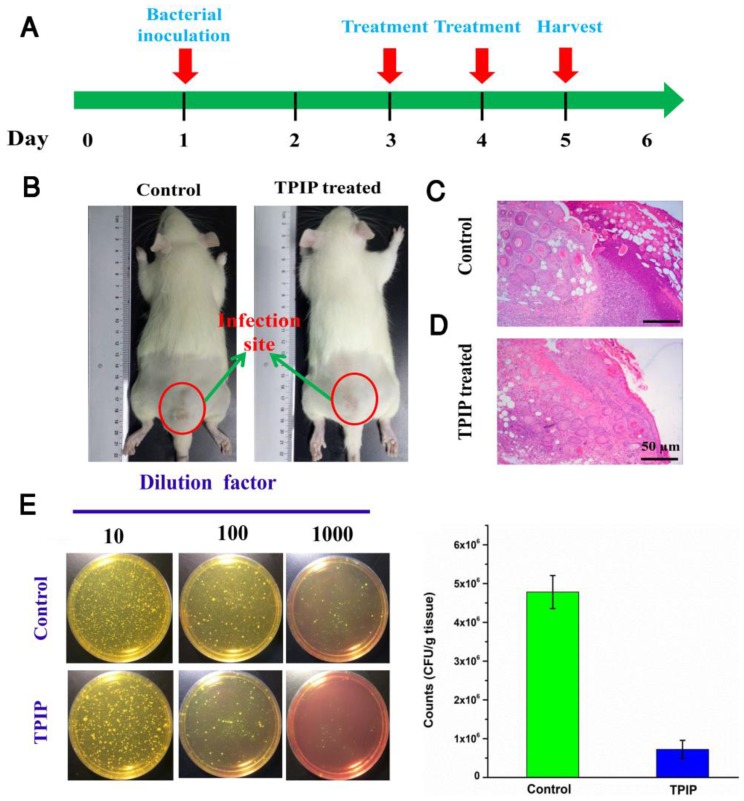

We further evaluated the antibacterial efficacy of TPIP-FONs in vivo using the S. aureus-infected rats. The rats were divided into two groups, the PBS-treated group (control) and the TPIP-FONs-treated group. The drugs were injected once a day. During the therapy, no obvious change in the activity and body weight was observed. Obvious skin infection could be observed in the PBS-treated group (Figure 6b and Figure S8a), whereas the TPIP-treated group exhibited slight skin infection after the 4th day of treatment. We next examined the treatment effect by hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E staining). As shown in Figure 6c, a large number of inflammatory cells and fragmentary epidermal layer appeared on the skin tissue of infection sites in the control groups, while fewer inflammatory cells were observed on the skin tissue of rats treated with TPIP-FONs for 2 days (Figure 6d). Therapeutic efficacy was further evaluated by enumerating the bacterial counts in the mannitol high salt agar medium for the homogenized tissue dispersions from the infectious site (Figure 6e). The number of S. aureus colonies from the infected tissues was 4.78×106 CFU g-1 after treatment with PBS. Tissues of rats treated with TPIP-FONs showed a bacterial burden of 7.2×105 CFU g-1, which was a significant reduction (with 85% bactericidal efficacy) compared to the control group. Thus, it can be concluded that TPIP-FONs exhibited an excellent antibacterial effect in vivo.

Figure 6.

(a) The schematic diagram of S. aureus-infected rat model and the therapeutic evaluation TPIP-FONs. (b) Photographs of S. aureus-infected rat treated with PBS (control) or TPIP-FONs solution. (c & d) Histological images of the skin from the control group and from the group treated with TPIP-FONs. (e) Photographs of the bacterial colonies and corresponding statistical histogram derived from the homogenized tissue dispersion of the infected sites injected with PBS and TPIP-FONs. The tissue dispersions were diluted (10, 100 and 1000 times) and plated on mannitol high salt agar medium at 37 °C for 12 hours.

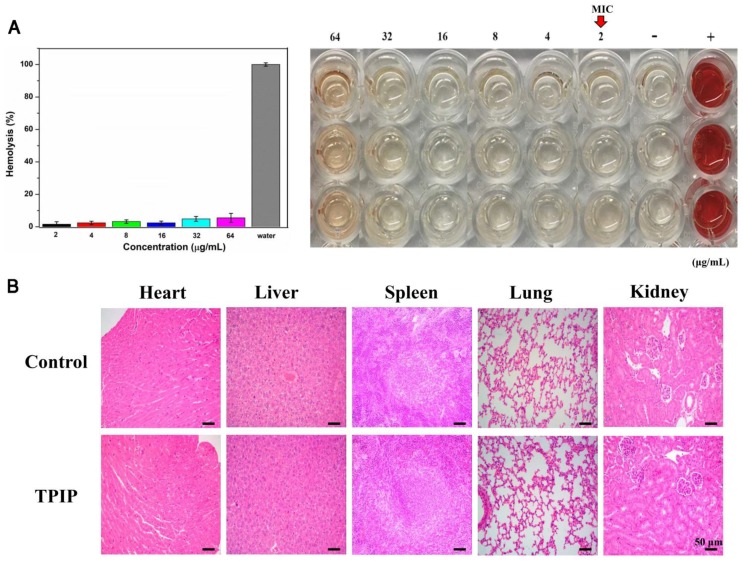

Biological safety of TPIP-FONs

For therapeutic use of antibacterial drugs, it is important to ensure that they have significant activity against bacteria but exhibit low toxicity to mammalian cells, in particular, red blood cells (RBCs). 29, 80 To determine the cytocompatibility of TPIP-FONs, the cytotoxicity of TPIP-FONs to AT II (normal lung cells) and L02 (normal liver cells) cells was evaluated by the MTT assay. As shown in Figure S9, the cell viability of AT-II or L02 cells was over 80% at a concentration of up to 64 µg mL-1, which was much higher than the MICs for S. aureus. The hemolytic activity of TPIP-FONs against red blood cells was also tested. In this experiment, RBCs in PBS and water solution were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. At a concentration of up to 64 µg mL-1, no obvious hemolytic activity (hemolysis rate: 5.22%) of TPIP-FONs was observed (Figure 7a). The results demonstrated that TPIP-FONs had good biocompatibility with mammalian cells and human RBCs. Finally, the in vivo toxicity of TPIP-FONs was also evaluated. The main organs of rats including the heart, lung, liver, kidney, and spleen were collected and examined histopathologically. TPIP-FONs treatment showed negligible effects on the normal anatomical structures of various organs compared to untreated controls (Figure 7b), demonstrating the safety of TPIP-FONs as a potential therapeutic agent.

Figure 7.

(a) Hemolysis assay of TPIP-FONs at several concentrations on human RBCs for 30 min at 37 °C. The mixture was centrifuged to detect the cell-free hemoglobin in the supernatant. RBCs incubated with PBS and water were used as negative (-) and positive (+) controls, respectively. (b) Histological evaluation of different organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) from rats treated with PBS and TPIP-FONs.

Conclusion

In summary, we constructed, for the first time, a bola type of molecule TPIP with AIE property, high water solubility, and antibacterial effect. TPIP can self-assemble into a rectangular structure of nanoparticles in aqueous solution. Due to the superior optical properties, TPIP-FONs can recognize and image gram-positive bacteria without any washing procedure. The imaging mechanism can be explained by the synergistic electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions between the negatively charged gram-positive bacterial cell wall and the self-assembled nanoparticles of TPIP-FONs. SEM observations indicate that the nanoparticles cause disruption of the cytoplasmic membrane and leakage of cytoplasm. In vitro antimicrobial activity suggests that TPIP-FONs have excellent antibacterial activity against S. aureus. Most importantly, TPIP-FONs exhibit intrinsic biocompatibility towards mammalian RBCs. Because of the low cytotoxicity and negligible hemolysis activity, TPIP-FONs can be used as an antibacterial agent in vivo. The integrated design of bimodal bacterial imaging with the antibacterial function of the self-assembled small molecules represents a novel strategy towards the construction of next-generation “theranostics” system in the field of bacterial prevention/treatment. Thus, TPIP-FONs exert a futuristic impact on the development of self-assembled small molecule antimicrobial nanomaterials for biomedical applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671756 and 81741134), Key Research Project of Science and Technology Foundation of Hunan Province (2017SK2090). We thank Varadha Balaji Venkadakrishnan for their efforts for language improvement. The authors also acknowledge the NMR measurements by the Modern Analysis and Testing Center of CSU.

Abbreviations

- DLS

Dynamic Light Scattering

- TEM

Transmission Electron Microscopy

- AIE

Aggregation-Induced Emission

- MIC

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- RBCs

Red blood cells

- CAC

Critical Aggregation Concentration

- OMVs

outer membrane vesicles.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

References

- 1.Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S, Brower C, Røttingen J-A, Klugman K. et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet. 2016;387:168–175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Control CfD, Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khameneh B, Diab R, Ghazvini K, Bazzaz BSF. Breakthroughs in bacterial resistance mechanisms and the potential ways to combat them. Microb Pathogen. 2016;95:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng VWL, Ke X, Lee AL, Hedrick JL, Yang YY. Synergistic codelivery of membrane-disrupting polymers with commercial antibiotics against highly ipportunistic bacteria. Adv Mater. 2013;25:6730–6. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li P, Zhou C, Rayatpisheh S, Ye K, Poon YF, Hammond PT. et al. Cationic peptidopolysaccharides show excellent broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities and high selectivity. Adv Mater. 2012;24:4130–7. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z, Yuan H, Liang H. Synthesis of multifunctional cationic poly(p-phenylenevinylene) for selectively killing bacteria and lysosome-specific imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:9260–4. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b01609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li P, Poon YF, Li W, Zhu H-Y, Yeap SH, Cao Y. et al. A polycationic antimicrobial and biocompatible hydrogel with microbe membrane suctioning ability. Nat Mater. 2011;10:149–56. doi: 10.1038/nmat2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Xu K, Wang H, Tan PJ, Fan W, Venkatraman SS. et al. Self-assembled cationic peptide nanoparticles as an efficient antimicrobial agent. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:457–63. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salick DA, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Design of an injectable β-hairpin peptide hydrogel that kills methicillin-resistant S. aureus. Adv Mater. 2009;21:4120–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Some S, Ho S-M, Dua P, Hwang E, Shin YH, Yoo H. et al. Dual functions of highly potent graphene derivative-poly-L-lysine composites to inhibit bacteria and support human cells. ACS Nano. 2012;6:7151–61. doi: 10.1021/nn302215y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li NN, Li JZ, Liu P, Pranantyo D, Luo L, Chen JC. et al. An antimicrobial peptide with an aggregation-induced emission (AIE) luminogen for studying bacterial membrane interactions and antibacterial actions. Chem Commun. 2017;53:3315–8. doi: 10.1039/c6cc09408b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Zhang M, Li B, Chen D, Dong X, Wang Y. et al. Versatile antimicrobial peptide-based ZnO quantum dots for in vivo bacteria diagnosis and treatment with high specificity. Biomaterials. 2015;53:532–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peschel A, Sahl H-G. The co-evolution of host cationic antimicrobial peptides and microbial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:529–36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma VC, Kharwar RN, Gange AC. Biosynthesis of antimicrobial silver nanoparticles by the endophytic fungus Aspergillus clavatus. Nanomedicine. 2010;5:33–40. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai X, Guo Q, Zhao Y, Zhang P, Zhang T, Zhang X. et al. Functional silver nanoparticle as a benign antimicrobial agent that eradicates antibiotic-resistant bacteria and promotes wound healing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:25798–807. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b09267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao F, Ju E, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Liu C, Li W. et al. An efficient and benign antimicrobial depot based on silver-infused MoS2. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4651–4659. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chernousova S, Epple M. Silver as antibacterial agent: ion, nanoparticle, and metal. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:1636–53. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barras A, Martin FA, Bande O, Baumann J-S, Ghigo J-M, Boukherroub R. et al. Glycan-functionalized diamond nanoparticles as potent E. coli anti-adhesives. Nanoscale. 2013;5:2307–16. doi: 10.1039/c3nr33826f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukherjee S, Chowdhury D, Kotcherlakota R, Patra S. Potential theranostics application of bio-synthesized silver nanoparticles (4-in-1 system) Theranostics. 2014;4:316–35. doi: 10.7150/thno.7819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao S, Abu-Esba L, Turkyilmaz S, White AG, Smith BD. Multivalent dendritic molecules as broad spectrum bacteria agglutination agents. Theranostics. 2013;3:658–66. doi: 10.7150/thno.6811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cha S-H, Hong J, McGuffie M, Yeom B, VanEpps JS, Kotov NA. Shape-dependent biomimetic inhibition of enzyme by nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity. ACS Nano. 2015;9:9097–105. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Applerot G, Lipovsky A, Dror R, Perkas N, Nitzan Y, Lubart R. et al. Enhanced antibacterial activity of nanocrystalline ZnO due to increased ROS-mediated cell injury. Adv Funct Mater. 2009;19:842–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sovadinova I, Palermo EF, Huang R, Thoma LM, Kuroda K. Mechanism of polymer-induced hemolysis: nanosized pore formation and osmotic lysis. Biomacromolecules. 2010;12:260–8. doi: 10.1021/bm1011739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Y, Long Y, Li Q-L, Han S, Ma J, Yang Y-W. et al. Layer-by-layer (LBL) self-assembled biohybrid nanomaterials for efficient antibacterial applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:17255–63. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b04216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hancock RE, Sahl H-G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1551–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marr AK, Gooderham WJ, Hancock RE. Antibacterial peptides for therapeutic use: obstacles and realistic outlook. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:468–72. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jo Y-K, Kim BH, Jung G. Antifungal activity of silver ions and nanoparticles on phytopathogenic fungi. Plant Dis. 2009;93:1037–43. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-93-10-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazzaz BSF, Khameneh B, Jalili-Behabadi M-m, Malaekeh-Nikouei B, Mohajeri SA. Preparation, characterization and antimicrobial study of a hydrogel (soft contact lens) material impregnated with silver nanoparticles. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014;37:149–52. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter AP, Brown JS, Bharti B, Wang A, Gangwal S, Houck K. et al. An environmentally benign antimicrobial nanoparticle based on a silver-infused lignin core. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10:817–23. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Jong WH, Van Der Ven LT, Sleijffers A, Park MV, Jansen EH, Van Loveren H. et al. Systemic and immunotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in an intravenous 28 days repeated dose toxicity study in rats. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8333–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Sun J, Li X, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Wang C. et al. Controllable synthesis of monodispersed silver nanoparticles as standards for quantitative assessment of their cytotoxicity. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1714–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson BA, Salyers AA, Whitt DD, Winkler ME. Bacterial pathogenesis: a molecular approach: American Society for Microbiology (ASM); 2011.

- 33.Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L. et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:228–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oethinger M, Warner DK, Schindler SA, Kobayashi H, Bauer TW. Diagnosing periprosthetic infection: false-positive intraoperative Gram stains. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:954–60. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1589-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grunow R, Splettstoesser W, McDonald S, Otterbein C, O'Brien T, Morgan C. et al. Detection of Francisella tularensis in biological specimens using a capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, an immunochromatographic handheld assay, and a PCR. Clin Diagn Lab Immun. 2000;7:86–90. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.1.86-90.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swanink C, Meis J, Rijs A, Donnelly JP, Verweij PE. Specificity of a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting Aspergillus galactomannan. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:257–60. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.257-260.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mothershed EA, Whitney AM. Nucleic acid-based methods for the detection of bacterial pathogens: present and future considerations for the clinical laboratory. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;363:206–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muyzer G, De Waal EC, Uitterlinden AG. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microb. 1993;59:695–700. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.695-700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reller LB, Weinstein MP, Petti CA. Detection and identification of microorganisms by gene amplification and sequencing. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1108–14. doi: 10.1086/512818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng D, Yu M, Fu F, Han W, Li G, Xie J. et al. Dual recognition strategy for specific and sensitive detection of nacteria using aptamer-coated magnetic beads and antibiotic-capped gold nanoclusters. Anal Chem. 2016;88:820–5. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aw J, Widjaja F, Ding Y, Mu J, Liang Y, Xing BG. Enzyme-responsive reporter molecules for selective localization and fluorescence imaging of pathogenic biofilms. Chem Commun. 2017;53:3330–3. doi: 10.1039/c6cc09296a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng W, Wang X, Xu P, Liu G, Eden HS, Chen X. Molecular imaging of apoptosis: from micro to macro. Theranostics. 2015;5:559–82. doi: 10.7150/thno.11548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ning X, Lee S, Wang Z, Kim D, Stubblefield B, Gilbert E. et al. Maltodextrin-based imaging probes detect bacteria in vivo with high sensitivity and specificity. Nat Mater. 2011;10:602–7. doi: 10.1038/nmat3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang M, Zhu PP, Xin P, Si W, Li ZT, Hou JL. Synthetic channel specifically inserts into the lipid bilayer of Gram-positive bacteria but not that of mammalian erythrocytes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:2999–3003. doi: 10.1002/anie.201612093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao E, Chen Y, Chen S, Deng H, Gui C, Leung CW. et al. A luminogen with aggregation-induced emission characteristics for wash-free bacterial imaging, high-throughput antibiotics screening and bacterial susceptibility evaluation. Adv Mater. 2015;27:4931–7. doi: 10.1002/adma.201501972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Syal K, Mo M, Yu H, Iriya R, Jing W, Guodong S. et al. Current and emerging techniques for antibiotic susceptibility tests. Theranostics. 2017;7:1795–805. doi: 10.7150/thno.19217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung HJ, Reiner T, Budin G, Min C, Liong M, Issadore D. et al. Ubiquitous detection of gram-positive bacteria with bioorthogonal magnetofluorescent nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2011;5:8834–41. doi: 10.1021/nn2029692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhong D, Zhuo Y, Feng Y, Yang X. Employing carbon dots modified with vancomycin for assaying Gram-positive bacteria like staphylococcus aureus. Biosen Bioelectron. 2015;74:546–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Oosten M, Schäfer T, Gazendam JA, Ohlsen K, Tsompanidou E, De Goffau MC. et al. Real-time in vivo imaging of invasive-and biomaterial-associated bacterial infections using fluorescently labelled vancomycin. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2584–91. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohanski MA, DePristo MA, Collins JJ. Sublethal antibiotic treatment leads to multidrug resistance via radical-induced mutagenesis. Mol Cell. 2010;37:311–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cavalieri F, Tortora M, Stringaro A, Colone M, Baldassarri L. Nanomedicines for antimicrobial interventions. J Hosp Infect. 2014;88:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu X, Radovic-Moreno AF, Wu J, Langer R, Shi J. Nanomedicine in the management of microbial infection-overview and perspectives. Nano Today. 2014;9:478–98. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Q, Wu Y, Lu H, Wu X, Chen S, Song N. et al. Construction of supramolecular nanoassembly for responsive bacterial elimination and effective bacterial detection. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:10180–89. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b00873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu MX, Wang X, Yang YW. Polymer nanoassembly as delivery systems and anti-bacterial toolbox: from PGMAs to MSN@ PGMAs. Chem Rec. 2017 doi: 10.1002/tcr.201700036. DOI: 10.1002/tcr.201700036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beyth N, Houri-Haddad Y, Domb A, Khan W, Hazan R. Alternative antimicrobial approach: nano-antimicrobial materials. Evid Based Compl Alternat Med. 2015;2015:246012–27. doi: 10.1155/2015/246012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Natan M, Banin E. From Nano to Micro: using nanotechnology to combat microorganisms and their multidrug resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2017;41:302–22. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L, Hu C, Shao L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:1227–49. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S121956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xie S, Manuguri S, Proietti G, Romson J, Fu Y, Inge A K. et al. Design and synthesis of theranostic antibiotic nanodrugs that display enhanced antibacterial activity and luminescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:8464–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708556114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science. 2001;294:1684–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhattacharya S, Samanta SK. Soft-nanocomposites of nanoparticles and nanocarbons with supramolecular and polymer gels and their applications. Chem Rev. 2016;116:11967–2028. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao T, Yang S, Cao X, Dong J, Zhao N, Ge P. et al. A smart self-assembled organic nanoprobe for protein-specific detection: design, synthesis, application and mechanism studies. Anal Chem. 2017;89:10085–93. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao Y, Thorkelsson K, Mastroianni AJ, Schilling T, Luther JM, Rancatore BJ. et al. Small-molecule-directed nanoparticle assembly towards stimuli-responsive nanocomposites. Nat Mater. 2009;8:979–85. doi: 10.1038/nmat2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma Y, Mou Q, Sun M, Yu C, Li J, Huang X. et al. Cancer theranostic nanoparticles self-assembled from amphiphilic small molecules with equilibrium shift-induced renal clearance. Theranostics. 2016;6:1703–16. doi: 10.7150/thno.15647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gao T, Cao X, Ge P, Dong J, Yang S, Xu H. et al. A self-assembled fluorescent organic nanoprobe and its application for sulfite detection in food samples and living systems. Org Biomol Chem. 2017;15:4375–82. doi: 10.1039/c7ob00580f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao T, Cao X, Dong J, Liu Y, Lv W, Li C. et al. A novel water soluble multifunctional fluorescent probe for highly sensitive and ultrafast detection of anionic surfactants and wash free imaging of Gram-positive bacteria strains. Dyes Pigm. 2017;143:436–43. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao D, Zhao S, Zhao L, Zhang X, Wei P, Liu C. et al. Discovery of biphenyl imidazole derivatives as potent antifungal agents: design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship studies. Bioorg Med Chem. 2017;25:750–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Anderson EB, Long TE. Imidazole-and imidazolium-containing polymers for biology and material science applications. Polymer. 2010;51:2447–54. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Riduan SN, Zhang Y. Imidazolium salts and their polymeric materials for biological applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:9055–70. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60169b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jennings MC, Minbiole KP, Wuest WM. Quaternary ammonium compounds: an antimicrobial mainstay and platform for innovation to address bacterial resistance. ACS Infect Dis. 2015;1:288–303. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang X, Chen X, Yang J, Jia H-R, Li Y-H, Chen Z. et al. Quaternized silicon nanoparticles with polarity-sensitive fluorescence for selectively imaging and killing gram-positive bacteria. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26:5958–70. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sambhy V, Peterson BR, Sen A. Antibacterial and hemolytic activities of pyridinium polymers as a function of the spatial relationship between the positive charge and the pendant alkyl tail. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1250–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yao Y, Chi X, Zhou Y, Huang F. A bola-type supra-amphiphile constructed from a water-soluble pillar [5] arene and a rod-coil molecule for dual fluorescent sensing. Chem Sci. 2014;5:2778–82. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guan W, Zhou W, Lu C, Tang BZ. Synthesis and design of aggregation-induced emission surfactants: direct observation of micelle transitions and microemulsion droplets. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:15160–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yuan H, Liu Z, Liu L, Lv F, Wang Y, Wang S. Cationic conjugated polymers for discrimination of microbial pathogens. Adv Mater. 2014;26:4333–8. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bartholomew JW, Mittwer T. The gram stain. Bacteriol Rev. 1952;16:1–29. doi: 10.1128/br.16.1.1-29.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhao Y, Tian Y, Cui Y, Liu W, Ma W, Jiang X. Small molecule-capped gold nanoparticles as potent antibacterial agents that target Gram-negative bacteria. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12349–56. doi: 10.1021/ja1028843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vaara M, Vaara T. Polycations as outer membrane-disorganizing agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;24:114–22. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.1.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kadurugamuwa JL, Clarke AJ, Beveridge TJ. Surface action of gentamicin on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5798–805. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5798-5805.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rizzello L, Cingolani R, Pompa PP. Nanotechnology tools for antibacterial materials. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:807–21. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.