Abstract

Background

older patients admitted to hospitals are at risk for hospital-acquired morbidity related to immobility. The aim of this study was to implement and evaluate an evidence-based intervention targeting staff to promote early mobilisation in older patients admitted to general medical inpatient units.

Methods

the early mobilisation implementation intervention for staff was multi-component and tailored to local context at 14 academic hospitals in Ontario, Canada. The primary outcome was patient mobilisation. Secondary outcomes included length of stay (LOS), discharge destination, falls and functional status. The targeted patients were aged ≥ 65 years and admitted between January 2012 and December 2013. The intervention was evaluated over three time periods—pre-intervention, during and post-intervention using an interrupted time series design.

Results

in total, 12,490 patients (mean age 80.0 years [standard deviation 8.36]) were included in the overall analysis. An increase in mobilisation was observed post-intervention, where significantly more patients were out of bed daily (intercept difference = 10.56%, 95% CI: [4.94, 16.18]; P < 0.001) post-intervention compared to pre-intervention. Hospital median LOS was significantly shorter during the intervention period (intercept difference = −3.45 days, 95% CI: [−6.67,−0.23], P = 0.0356) compared to pre-intervention. It continued to decrease post-intervention with significantly fewer days in hospital (intercept difference= −6.1, 95% CI: [−11,−1.2]; P = 0.015) in the post-intervention period compared to pre-intervention.

Conclusions

this is a large-scale study evaluating an implementation strategy for early mobilisation in older, general medical inpatients. The positive outcome of this simple intervention on an important functional goal of getting more patients out of bed is a striking success for improving care for hospitalised older patients.

Keywords: mobilisation, frail, acute care hospital, older people, implementation

Background

Older patients admitted to hospital are at increased risk for hospital-acquired morbidity related to immobility [1]. Bed rest is a contributor to iatrogenic complications including delirium, decubitus ulcers, pneumonia, and muscle atrophy [2]. Each day spent immobile is associated with 1% to 5% loss of muscle strength in an older person [3]. In a vulnerable senior, this can quickly result in the loss of the ability to transfer and ambulate independently.

Early mobilisation strategies targeting clinicians have demonstrated benefits in patients with stroke, pneumonia, and hip fracture [4–7]. Early mobilisation protocols decreased length of stay (LOS) and increased patient’s functional status and likelihood of being discharged home [5, 8–10]. However, more recent studies of early mobilisation showed mixed results, suggesting the need to tailor the strategy to the individual’s condition [11–14]. Despite evidence documenting mobilisation benefits, hospitalised older patients spend the majority of their time in bed [15, 16]. In acute care hospitals, general medical inpatient units have one of the oldest patient populations [17]; older patients spend a median of 4% of the day out of bed [15, 16]. No large-scale studies have evaluated the implementation of early mobilisation in this setting. Our aim was to implement and evaluate an evidence-based strategy targeting staff to promote early mobilisation in older hospitalised patients. We were interested in implementing it in a ‘real world’ setting, reflecting constraints in resources, aligning with hospital initiatives, and facilitating sustainability.

Methods

We used a pragmatic, quasi-experimental interrupted time series (ITS) design to evaluate the impact of the staff intervention on the primary outcome, patient mobilisation, over 3 time periods—pre-intervention (10 weeks), during intervention (8 weeks) and post-intervention (20 weeks). We completed the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines [18] and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist [19] (see Supplementary data, Appendix 1, available at Age and Ageing online). We used an integrated knowledge translation approach whereby researchers and knowledge users worked together to design and implement the process [20]. This study builds on a pilot study conducted in four Toronto hospitals. Complete methods were described in a previous publication [21]. The protocol was approved by the research ethics board at each hospital.

Study setting and participants

Patients were those aged 65 years and older admitted to inpatient medicine units. Patients receiving palliative care or on bed rest were excluded. The study was conducted between January 2012 and December 2013 in 14 university-affiliated hospitals in Ontario, Canada.

Study design

The intervention focused on implementing three messages: (i) patients should be assessed for mobilisation status within 24 h of admission; (ii) mobilisation should occur at least three times a day; (iii) mobility should be progressive and scaled, tailored to the patient’s abilities. These messages were chosen based on systematic reviews [4, 22] and feasibility.

At each hospital, the local implementation team included a physician leader, education coordinator and research coordinator. No funding was provided for the intervention strategy or for the local implementation team; funding was provided for the research coordinator.

The strategy used to implement the mobilisation messages targeting staff was multi-component and tailored to local context. All hospitals were required to provide interprofessional education and educational tools; additional strategies were selected based on appropriateness and context (e.g. reminders, local opinion leaders, patient/caregiver education materials). Hospitals were provided resources (e.g. education modules, checklists, mobility algorithms) to implement the intervention and invited to use or adapt these, or develop new materials. Intervention details are available in the protocol paper [21] and are freely accessible available through the MOVE Portal (http://movescanada.ca/user/login). All hospitals received implementation coaching from the central Mobilisation of Vulnerable Elders in Ontario (MOVE ON) team, had access to an online community of practice, and collaborated in monthly teleconferences. Coaches worked with each local implementation team to select intervention strategies mapped to identified barriers and facilitators, collected through focus groups with interprofessional care staff and using the theoretical domains framework (see Supplementary data, Appendix 2, available at Age and Ageing online) [23] and evidence on intervention effectiveness.

Measures

The primary outcome was mobilisation status of patients assessed on twice-weekly visual audits (on random weekdays) that took place three times daily. Patients were considered mobilised if the visual audit identified the patient to be out of bed. The focus was on early mobilisation, aligned with evidence from studies that included out of bed mobilisation, recognising the critical need to focus on mobilisation and not just ambulation [4, 6, 12, 13]. Visual audits were conducted by a research coordinator; this method was evaluated using three independent auditors and had high inter-rater agreement (kappa 0.83). We also tested it against continuous rounding every 15 min for 6 h over 2 days (positive likelihood ratio 12.2 (95% confidence interval [CI]: [3.22, 46.46]) and negative likelihood ratio 0.06 (95% CI: [0.02, 0.25])). Secondary outcomes were hospital LOS, rate of injurious falls, discharge destination and functional status. We collected data on eligible patients including age, gender, place of residence prior to admission, and admitting diagnosis from chart reviews and hospital decision support data. Alongside, we conducted a process evaluation including a log of intervention strategies (including adherence).

Statistical analysis

Daily mobility of patients, recorded from 3 audits/day, was summarised as the proportion of patients mobilised (out of bed) each day. This proportion was averaged over the two audit days to provide an estimate of daily mobility for a given week. This was done pre- (10 weeks, 20 assessment points), during (8 weeks, 16 assessment points) and post-intervention (20 weeks, 40 assessment points) for each hospital. This proportion was averaged across all the hospitals to provide an overall estimate of daily mobility. ITS analysis using a segmented linear regression model was performed to examine the impact of the intervention on mobility [24]. Presence of serial autocorrelation between mobility across the different time points was assessed using the Durbin–Watson’s statistic [25] and when statistically significant, adjustment for autocorrelation was done [26]. Hospital-level ITS analysis was performed to investigate the site-level performance of the intervention and variation in mobility. Results from the ITS analysis were presented in the form of slope and intercept differences, as well as observed and predicted differences across the time periods.

Median hospital LOS in a given week was considered from all participating hospitals pre, during and post-intervention. Discharge date was used to classify patients into pre, during and post-intervention periods. The weekly median LOS was then averaged overall hospitals to provide an overall trend in LOS across time in an ITS framework. ITS with segmented regression was performed to investigate the intervention impact on LOS; results are presented in the form of slope and intercept differences and observed differences across the time periods. To detect a 10% decrease for the patients being in bed after the intervention, based on a power of 0.8 and type I error of 0.05, correlation for AR(1) of 0.4 and proportion of patients being in bed before the intervention at 66%, the total number of required data collection (or assessment) points was 38. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software [27] and statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Participants and units

Thirty-two units in 14 hospitals participated in MOVE ON (one to five per hospital). About 14,540 patients (mean age 79.9 years [standard deviation [SD] 8.32]) contributed data; 53.3% were female. There was an average of 33 beds per unit (range 14–72) among the mostly medical units (one cardiovascular unit).

A total of 115,025 observations from 12,490 patients (mean age 80.0 years [SD 8.36]) in 11 hospitals were combined in the overall analysis; participant characteristics are in Table 1. Three hospitals were excluded from the overall analysis (N = 2,050); one due to incomplete data, and two because the units included complex continuing care patients who were not comparable to an acute care population. We conducted site-level ITS analysis for these 3 hospitals (see Supplementary data, Appendix 3, available at Age and Ageing online).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics for the 11 sites included in the ITS analysis

| Overall | Pre | During | Post | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects (N) | 12,490 | 3,318 | 2,786 | 6,386 |

| Age [mean (sd)] | 80.0 (8.36) | 80.0 (8.22) | 80.1 (8.48) | 79.9 (8.37) |

| Gender M:F [n (%)] | 5,781 (46.3): 6,709 (53.7) | 1,569 (47.3): 1,749 (52.7) | 1,316 (47.2): 1,470 (52.8) | 2,896 (45.3): 3,490 (54.7) |

| Top 5 most responsible discharge diagnoses [n (%)] | ||||

| Gastrointestinala | 1,148 (9.2) | 331 (10.0) | 228 (8.2) | 589 (9.2) |

| Malignant neoplasm | 1,115 (8.9) | 278 (8.4) | 242 (8.7) | 595 (9.3) |

| Pneumonia | 977 (7.8) | 232 (7.0) | 219 (7.9) | 526 (8.2) |

| Congestive heart failure | 802 (6.4) | 221 (6.7) | 181 (6.5) | 400 (6.3) |

| Infections | 749 (6.0) | 203 (6.1) | 175 (6.3) | 371 (5.8) |

| Place of residence prior to admission (%) | ||||

| Nb | 7,786 | 1,821 | 1,777 | 4,188 |

| Private home, apartment or condominium | 4,845 (62.2) | 1,061 (58.3) | 1,099 (61.8) | 2,685 (64.1) |

| Acute facilityc | 494 (6.3) | 157 (8.6) | 106 (6.0) | 231 (5.5) |

| Nursing home or long-term care home | 2,077 (26.7) | 513 (28.2) | 477 (26.8) | 1,087 (25.9) |

| Rehabilitation facilityc | 293 (3.8) | 74 (4.0) | 79 (4.4) | 140 (3.4) |

| Other | 77 (1.0) | 16 (0.9) | 16 (0.9) | 45 (1.1) |

aGastrointestinal diagnoses include gastroenteritis, peptic ulcer disease, reflux, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticular disease, constipation, obstruction, GI bleeding, liver and biliary diseases.

bAdjusted sample size based on available patient information on place of residence prior to admission.

cWhen transferred from another acute or rehabilitation facility, the patient’s place of residence prior to admission is not known.

Primary outcome: patient mobilisation

Overall results

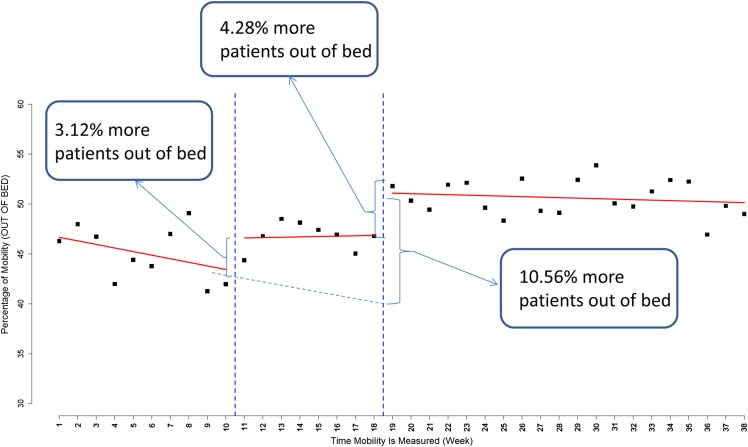

In the overall ITS analysis for the 11 hospitals, significantly more patients were out of bed per day post-intervention compared to pre-intervention (intercept difference = 10.56%, 95% CI: [4.94, 16.18]; P < 0.001; Figure 1). During the intervention, more patients were out of bed per day compared to pre-intervention but this was not statistically significant (intercept difference = 3.12%, 95% CI: [−0.53, 6.76]). Post-intervention, mobilisation continued to increase compared to both the pre-intervention and intervention periods (see Supplementary data, Appendix 4, available at Age and Ageing online). During the post-intervention period, significantly more patients (intercept difference = 4.28%, 95% CI: [1.29, 7.27], P = 0.005) were mobilised compared to the intervention period, indicating sustained intervention impact. At the end of the study period (Week 38), the observed average daily mobility was 47.03% compared to 41.97% at the end of the pre-intervention period (Week 8).

Figure 1.

Overall weekly visual audit results for proportion of patients out of bed.

During the intervention, the rate of change in daily mobilisation increased by 0.40% per week compared to pre-intervention; this was not statistically significant (slope change = 0.40%, 95% CI: [−0.32, 1.11]). Post-intervention, the rate of change in daily mobilisation continued to increase at 0.31% per week but was not statistically significant (slope change = 0.31, 95% CI: [−0.13, 0.75]). Supplementary data, Appendix 5, available at Age and Ageing online provides the differences in observed and predicted proportions of patients mobilised at the end of each period.

Hospital-specific results

The hospital-specific results are consistent with respect to impact of the intervention on patient mobilisation; data from the majority of the sites (10/11) showed the intervention increased daily mobilisation of patients (see Supplementary data, Appendices 6–8, available at Age and Ageing online). For the 3 sites removed from the overall ITS analysis, an increase in patient mobilisation was observed during intervention in all three sites (see Supplementary data, Appendix 8, available at Age and Ageing online).

Secondary outcomes

Length of stay

Overall results

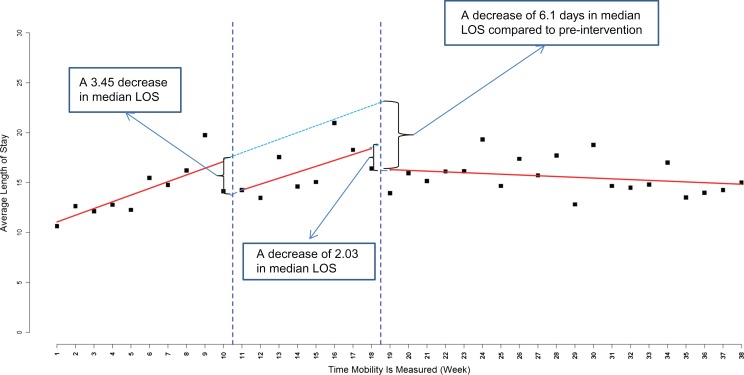

In the post-intervention period, the median LOS was significantly shorter (intercept difference = −6.1 days, 95% CI: [−11,−1.2]; P = 0.015) compared to the pre-intervention period, and 2.03 days (95% CI: [−4.65,0.60], P = 0.1299) shorter compared to the intervention period (Figure 2). At the end of the pre-intervention period, median LOS was observed to be 12.38 days. During the intervention period, there was a significant decrease in median LOS (intercept difference = −3.45 days, 95% CI: [−6.67, −0.23]; P = 0.0356) averaged across all sites. Median LOS increased during the intervention but was not statistically significant (slope change = −0.08, 95% CI: [−0.7, 0.55]) compared to pre-intervention. The trend in median LOS (see Supplementary data, Appendix 9, available at Age and Ageing online) showed that the rate of decline in LOS in the post-intervention period was significantly different compared to the rate of change during the pre-intervention period (slope difference = −0.75, 95% CI: [−1.13,−0.36], P < 0.001 = 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Change in length of stay.

Hospital-specific results

A high correlation between reduced LOS and increase in mobilisation rates was observed across sites, where 92.3% of the sites showed an increase in mobilisation during or post-intervention and a decrease in LOS during these periods. In sites where there was no increase in mobility due to the intervention, there was no decrease in LOS (see Supplementary data, Appendices 10 and 11, available at Age and Ageing online).

Other

Local decision support data on falls and functional status was inadequate for full analysis but available data are provided in Supplementary data, Appendices 12–14, available at Age and Ageing online. No statistically significant differences were found in discharge destination.

Data on which implementation strategies were delivered at each site are available in Suppementary data, Appendix 15, at Age and Ageing online.

Discussion

This study represents the first large-scale study to evaluate implementation of early mobilisation in older medical patients. Delivering the intervention across multiple hospitals resulted in 10% more patients out of bed at the end of the study and a significant decrease in the median LOS. Patient mobilisation rates improved both during and after implementation. Our results are important given that the intervention was implemented without new resources aside from funding for a research coordinator; this indicates buy-in and facilitates sustainability. Several factors likely contributed to the intervention’s success including the hospitals’ ability to adapt the intervention to local context [28] by understanding local barriers and facilitators [29] and mapping these to behaviour change theory and intervention strategies [23].

Our results are aligned with studies that showed benefit of mobilising patients with stroke, hip fracture and pneumonia [4–6] and those admitted to critical care [12]. Other studies have found early mobilisation of patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and stroke led to worse outcomes [11]. Overall, these studies highlight the importance of tailoring mobility to the patient’s condition, ensuring that the patient is medically stable before intensive rehabilitation [11, 12].

We observed a significant decrease in median LOS and the findings were consistent across hospitals. Other external factors may have affected LOS; however, in 10 of 14 sites a decrease in LOS correlated with improvement in mobilisation rates in intervention and post-intervention periods. In 3 of the 4 remaining sites, increased mobilisation during the intervention period resulted in a delayed effect on LOS, where a decreased LOS was observed post-intervention. This is to be expected since many patients admitted during the intervention period would likely be discharged post-intervention.

Our study has several strengths. The primary outcome was objective with high inter-rater reliability. Mobilisation was the outcome, consistent with evidence from trials showing benefit to patients being out of bed [4, 6, 12, 13]. Our sample included 14 hospitals and over 10,000 audited patients, making this the largest study of an early mobilisation implementation strategy to date. We assessed implementation activities and quality through an intervention process template [23]. Finally, research funding was used for evaluation and central implementation coaching; hospitals provided in-kind resources to deliver the implementation intervention, facilitating the sustainability and scalability. We did not conduct an economic analysis, but all 14 hospitals delivered the intervention without any additional resources. To date, 65 hospitals worldwide have implemented MOVE ON.

There are limitations of our study. First, the method of assessment (i.e. visual audits) was a surrogate for continuous direct observation or use of electronic monitoring devices; cost of these alternatives was prohibitive. With our approach we may have underestimated mobilisation, however, this surrogate measure was feasible and reliable and is used to assess hand hygiene compliance [30]. An alternative would be a subjective measure of mobility (e.g. self-report) however, these measures also have limitations such as adherence. Second, we did not collect information about external factors that may have impacted LOS. Third, none of the hospitals routinely collected patient-level data on mobility but with MOVE ON, some have initiated it. Fourth, we were not able to provide analysis of patient outcomes such as functional status due to clinical documentation limitations. Fifth, the rate of discharge to long-term care facility was high. This may reflect hospital coding issues related to multipurpose facilities with long-term care, rehabilitation and independent living co-located. Sixth, we were not able to analyse impact of mobilisation on falls due to data quality issues, a recognised limitation of fall reporting [31]. Nor did we examine for outcomes such as delirium, decubitus ulcers, venous thrombosis, complications associated with immobility. Although these are clinically relevant outcomes, implementation studies targeting behaviour change, typically use the behaviour change (mobilisation) as the outcome when there is a direct association between the behaviour change and the clinical outcomes.

MOVE ON engaged multiple hospitals to implement a contextualised intervention to promote early mobilisation of hospitalised seniors. Following the intervention, hospital units had significantly higher patient mobility rates.

Key points.

Evidence suggests that early mobilisation initiatives can effectively improve patient outcomes in older adults.

The MOVE ON program is a multi-component, interprofessional early mobilisation initiative.

MOVE ON improved patient mobility and decreased LOS.

MOVE ON can be tailored to various healthcare settings and builds on existing infrastructure to facilitate sustainability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Charmalee Harris for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. We would like to thank members of the MOVE ON Collaborators: Baycrest Health Sciences: Sylvia Davidson, Terumi Izukawa, Shelly-Ann Rampersad; Hamilton Health Sciences: Sharon Marr, Anne Pizzacalla; Health Sciences North: Andrea Lee, Christine Paquette, Debbie Szymanski; Kingston General Hospital: Richard Jewitt, Rachael Morkem, Johanna Murphy, Terry Richmond; London Health Sciences Centre: Trish Fitzpatrick, Alexander Nicodemo, Mary-Margaret Taabazuing; Montfort Hospital: Emily Escaravage, John Joanisse, Philippe Marleau, Carolyn Welch; Mount Sinai Hospital: Natasha Bhesania, Rebecca Ramsden, Samir K. Sinha, Tracy Smith-Carrier; North York General Hospital: Krysta Andrews, Gabriel Chan, Norma McCormack, Maria Monteiro, Kam Tong Yeung; The Ottawa Hospital: Frederic Beauchemin, Lara Khoury, Barbara Power, Vicki Thomson; St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton: Vincent G. DePaul, Diana Hatzoglou, Miranda Prince, Bashir Versi; St. Michael’s Hospital: Wai-Hin Chan, Rami Garg, Christy Johnson, Christine Marquez, Julia E. Moore, Kasha Pyka, Lee Ringer, Alistair Scott, Sharon E. Straus, Judy Tran, Maria Zorzitto; Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre: Ummukulthum Almaawiy, Deborah Brown, Shima Deljoomanesh, Jocelyn Denomme, Barbara Liu, Beth O’Leary; Thunder Bay Regional Health Sciences Centre: Hanan ElSherif, Jennifer Hawley, Terry Robertshaw; University Health Network: Mary Kay McCarthy, Andrew Milroy, Anne Vandeursen.

Further acknowledgements can be found in Appendix 16 in the Supplementary data on the journal website.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Authors’ contributions

B.L. and S.E.S. conceived the study. BL wrote the first draft of the paper, with all authors commenting on it and subsequent drafts. B.L., U.A., J.E.M., W.C., S.K., J.E., J.H. and S.E.S. made substantial contributions to conception, design, project management, data analysis and interpretation. Contributing authors made substantial contributions to the work reported in this manuscript including study design, data collection and interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

Funding for this project has been received from the Council of Academic Hospitals of Ontario’s (CAHO) Adopting Research To Improve Care (ARTIC) Program, the Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan for the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario, and the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto. In-kind funding has been provided by the Regional Geriatric Program of Toronto, the Knowledge Translation Program of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s, and the following hospitals: Baycrest Health Sciences, Hamilton Health Sciences, Health Sciences North, Kingston General Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre, Montfort Hospital, Mount Sinai Hospital, North York General Hospital, The Ottawa Hospital, St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, Thunder Bay Regional Health Sciences Centre, University Health Network. S.E.S. is funded by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by the research ethics board at each participating hospital. Research Ethics Board (REB) of St. Michael’s Hospital (REB# 11–261), Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

References

- 1. Gillick MR, Serrell NA, Gillick LS. Adverse consequences of hospitalization in the elderly. Soc Sci Med 1982; 16: 1033–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asher RA. The dangers of going to bed. Br Med J 1947; 2: 967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118: 219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cumming TB, Collier J, Thrift A, Bernhardt J. The effect of very early mobilization after stroke on psychological well-being. J Rehabil Med 2008; 40: 609–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oldmeadow LB, Edwards ER, Kimmel LA, Kipen E, Robertson VJ, Bailey MJ. No rest for the wounded: early ambulation after hip surgery accelerates recovery. ANZ J Surg 2006; 76: 607–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mundy LM, Leet TL, Darst K, Schnitzler MA, Dunagan WC. Early mobilization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2003; 124: 883–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chippala P, Sharma R. Effect of very early mobilisation on functional status in patients with acute stroke: a single-blind, randomized controlled trail. Clin Rehabil 2016; 30: 669–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS et al. . Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 373: 1874–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fisher SR, Kuo YF, Graham JE, Ottenbacher KJ, Ostir GV. Early ambulation and length of stay in older adults hospitalized for acute illness. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170: 1942–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chandrasekaran S, Ariaretnam SK, Tsung J, Dickison D. Early mobilization after total knee replacement reduces the incidence of deep venous thrombosis. ANZ J Surg 2009; 79: 526–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greening NJ, Williams JE, Hussain SF et al. . An early rehabilitation intervention to enhance recovery during hospital admission for an exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014; 349: g4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernhardt J, Langhorne P, Lindley RI et al. . Efficacy and safety of very early mobilisation within 24 h of stroke onset (AVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M et al. . Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 1377–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD Jr et al. . Comparison of posthospitalization function and community mobility in hospital mobility program and usual care patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57: 1660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Callen BL, Mahoney JE, Grieves CB, Wells TJ, Enloe M. Frequency of hallway ambulation by hospitalized older adults on medical units of an academic hospital. Geriatr Nurs 2004; 25: 212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ettinger WH. Can hospitalization-associated disability be prevented? JAMA 2011; 306: 1800–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ogrinc G, Mooney SE, Estrada C et al. . The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care 2008; 17(Suppl 1):i13–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I et al. . Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Br Med J 2014; 348: g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB et al. . Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006; 26: 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu B, Almaawiy U, Moore JE, Chan WH, Straus SE. MOVE ON Team Evaluation of a multisite educational intervention to improve mobilization of older patients in hospital: protocol for mobilization of vulnerable elders in Ontario (MOVE ON). Implement Sci 2013; 3: 76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke 2008; 39: 390–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Marquez C et al. . MOVE ON Team Mapping barriers and intervention activities to behaviour change theory for Mobilization of Vulnerable Elders in Ontario (MOVE ON), a multi-site implementation intervention in acute care hospitals. Implement Sci 2014; 9: 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002; 27: 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Durbin J. Testing for serial correlation in least-squares regressions when some of the regressors are lagged dependent variables. Econometrica 1970; 38: 410–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cochrane D, Orcutt G. Application of least squares regression to relationships containing auto correlated error terms. J Am Stat Assoc 1949; 44: 32–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27. R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009; 4: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C et al. . Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (4): CD005470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reisinger HS, Yin J, Radonovich L et al. . Comprehensive survey of hand hygiene measurement and improvement practices in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Infect Control 2013; 41: 989–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oliver D. Prevention of falls in hospital inpatients: agendas for research and practice. Age Ageing 2004; 33: 328–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.