Abstract

Variants in HNF1A encoding hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α (HNF-1A) are associated with maturity-onset diabetes of the young form 3 (MODY 3) and type 2 diabetes. We investigated whether functional classification of HNF1A rare coding variants can inform models of diabetes risk prediction in the general population by analyzing the effect of 27 HNF1A variants identified in well-phenotyped populations (n = 4,115). Bioinformatics tools classified 11 variants as likely pathogenic and showed no association with diabetes risk (combined minor allele frequency [MAF] 0.22%; odds ratio [OR] 2.02; 95% CI 0.73–5.60; P = 0.18). However, a different set of 11 variants that reduced HNF-1A transcriptional activity to <60% of normal (wild-type) activity was strongly associated with diabetes in the general population (combined MAF 0.22%; OR 5.04; 95% CI 1.99–12.80; P = 0.0007). Our functional investigations indicate that 0.44% of the population carry HNF1A variants that result in a substantially increased risk for developing diabetes. These results suggest that functional characterization of variants within MODY genes may overcome the limitations of bioinformatics tools for the purposes of presymptomatic diabetes risk prediction in the general population.

Introduction

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a dominantly inherited subtype of diabetes, estimated to account for 1–2% of all diabetes cases and is caused by mutations across 10 or more genes (1). MODY arises most commonly from mutations in HNF1A (2) and GCK (3,4), and less commonly from mutations in HNF4A (5), HNF1B (6), and INS (7). Genetic studies in multiethnic cohorts have shown that variants in MODY genes may also predispose carriers to the risk of diabetes later in life (8–10). In the hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α (HNF1A) gene, population-specific variants with very low minor allele frequency (MAF) have demonstrated an increased risk for type 2 diabetes in selected populations. The HNF1A E508K rare variant (MAF 0.45% in Mexicans and almost absent in other populations) is associated with type 2 diabetes in the Mexican population (odds ratio [OR], 5.48; P = 4.4 × 10−7) (11), and the G319S variant is associated with early-onset type 2 diabetes in the Oji-Cree population (OR 4.0 in homozygous carriers and OR 1.97 in heterozygous carriers) (12). Meta-analyses have shown the common variants I27L and A98V slightly increase the type 2 diabetes risk (I27L: OR 1.09; P = 8.1 × 10−15; MAF 33%; A98V: OR 1.22; P = 5.1 × 10−10; MAF 2.7%) (13). Although concurrent large association studies conclude that common variants in HNF1A (MAF >5%) do not associate with type 2 diabetes (14,15), certain combinations of variants (I27L and A98V) have, in vivo, shown a modest but significant association with impairment in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. I27L alone has been associated with an increased type 2 diabetes risk (OR 1.5; P = 0.002) in elderly (age >60) and overweight (BMI >25 kg/m2) patients (OR 2.3; P = 0.002) (16).

The spectrum of the in vitro functional consequence of HNF1A variants differs largely. Analyses of HNF1A mutations that cosegregate with familial early-onset diabetes (MODY) have demonstrated that they most often cause diabetes as a result of HNF-1A haploinsufficiency (loss of function), by none or severely impaired binding and transactivation of HNF-1A target genes (<∼30% compared with wild-type), and/or by reducing HNF-1A protein stability (17–19). Similar investigations of the type 2 risk variants G319S and E508K have shown a milder effect on HNF-1A function compared with MODY variants by reducing the HNF-1A transactivation potential to <40–60% (11,20), whereas DNA binding properties have remained intact. The functional consequence of common variants, however, are mild when assessed alone (∼70% transactivation by L27 and ∼60% by V98) compared with combined (∼50% by L27 and V98) variants (16). The DNA binding properties and protein levels of these common variants have remained intact.

A diagnosis of MODY can alter treatment and is important for prognostic evaluation (21), and identification of individuals at risk for diabetes later in life can target lifestyle interventions (22). The increasing availability of next-generation sequencing offers an opportunity to identify individuals who carry variants that may cause MODY or elevate the diabetes risk.

The spectrum of rare coding variants in seven of the most common MODY genes was recently investigated in well-phenotyped cohorts of the general population (23). This study concluded that 0.5–1.5% of randomly selected individuals carry rare variants that are interpreted as causal for MODY in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) or fulfill bioinformatics criteria for pathogenicity but that most of these carriers were euglycemic through middle age. We hypothesized that among these rare variants, only a subset might predispose to type 2 diabetes and that they could be better distinguished from benign variants and MODY variants using functional investigations compared with the bioinformatics variant prediction tools commonly used in biomedical research.

To test this hypothesis, we focused on rare coding variants identified in the HNF1A gene, assessing HNF-1A function. HNF-1A is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of several liver- and pancreas-specific genes involved in glucose transport and glucose/amino acid/lipid metabolism (24), and mutations in HNF1A are associated with the most common form of MODY in most populations (MODY3) (25), resulting in reduced β-cell insulin secretion and an early disease onset (before 25–35 years).

Research Design and Methods

Study Design

We sought to investigate whether the functional classification of HNF1A rare variants can inform models of diabetes risk prediction in the general population. By studying all protein-coding HNF1A rare variants identified by exome sequencing in the three well-phenotyped population cohorts (described below), using 1) bioinformatics tools used to aid medical diagnostics or 2) functional assays assessing transactivation, DNA binding ability, and nuclear localization, we could estimate the effect of individual variants and diabetes risk. We reasoned that risk variants could be validated based on statistics from a public knowledge base for type 2 diabetes genetics (http://www.type2diabetesgenetics.org).

Variant Selection and Phenotypic Description of the Study Populations

We studied protein-coding rare variants in HNF1A identified by exon sequencing and reported in a recent study (23). The variants were identified in 4,115 random individuals from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) Offspring cohort (n = 1,653), the Jackson Heart Study (JHS) cohort (n = 1,691), and type 2 diabetes case and control patients ascertained from the extremes of genetic risk (extreme type 2 diabetes [T2D] cohort, n = 771).

The FHS is a three-generation prospective family study of individuals of European ancestry designed to identify factors that contribute to cardiovascular disease, and the Offspring cohort consists of 5,124 adult children and spouses (enrolled in 1971) of the original participants (26). The JHS is a large community-based observational study of participants who are of African American origin. The study participants, who were recruited from urban and rural areas of the Jackson, Mississippi, metropolitan statistical area, consist of 6,500 men and women and 400 families (27). The extreme T2D cohort was originally selected from 27,500 individuals in three prospective cohorts: the Malmö Preventive Project (Sweden) (28), the Scania Diabetes Registry (Sweden), and the Botnia Study (Finland), selecting lean and young case patients with type 2 diabetes and old and obese control patients. Individuals with age of diabetes diagnosis younger than 35 years were excluded in an attempt to avoid consideration of patients with type 1 diabetes or MODY. In general, the individuals in the three cohorts differ in sex, age, and BMI. JHS individuals had a higher mean BMI (and represented by more women) than individuals in the FHS cohort, whereas the mean age was higher in FHS. Mean fasting plasma glucose values were approximately similar across the cohort case and control patients but were highest in JHS case patients.

Bioinformatics Classification

We used five different in silico prediction tools to classify the variants bioinformatically: sorting tolerant from intolerant (SIFT) (29), PolyPhen-2 (HumVar model), Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) (30), MutationTaster (31), and Align Grantham Variation and Grantham Deviation (GVGD) (32,33). For CADD we used a cutoff value of 15 (>15, pathogenic). The variants were assigned two classes: likely pathogenic or unlikely pathogenic. A variant was classified as likely pathogenic if it was scored as pathogenic in at least four of the five variant interpretation software tools used. A variant was classified as unlikely pathogenic if it was scored as pathogenic in less than four of the five variant interpretation software tools used.

Functional Assays

Plasmids

We used human pancreatic HNF1A cDNA (National Center for Biotechnology Information Entrez Gene BC104910.1) in the pcDNA3.1/HisC vector (Thermo Fisher) for the functional studies (19), and all HNF1A variants were made using the QuikChange XL Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies). We verified the sequence of all constructs by Sanger sequencing. Constructs encoding the HNF1A mutants p.P112L, p.R263C, p.Q446*, and p.P447L, previously reported to cause MODY3 (18,19), were used as controls in the functional assays. One plasmid preparation was prepared for each of the 27 rare variants and compared with multiple wild-type (n >3) and MODY control variant plasmid preparations (n >2). Reporter gene constructs used in the transactivation assay were pGL3-RA, containing the rat albumin promoter and HNF-1A recognition sequence (nucleotide −170 to +5) next to the Firefly luciferase gene (pGL3-Basic vector backbone; Promega), and the control reporter vector pRL-SV40 (Promega), encoding the Renilla luciferase gene.

Transactivation Analysis

HeLa cells, grown as described previously (19), were cotransfected with reporter plasmid pGL3-RA, internal control pRL-SV40, and wild-type HNF1A or HNF1A variant plasmids. Empty vector pcDNA3.1/HisC was used as a control for the basal activity of promoter. Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transcriptional activity on the rat albumin promoter was measured 24 h posttransfection with the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega) in a Chameleon luminometer (Hidex). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized by correction for transfection efficiency of Renilla luciferase (internal control). p.P112L and p.P447L were included as MODY control HNF1A variants for severely reduced transactivation activity.

Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Localization by Immunofluorescence

Nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of wild-type and HNF-1A variant proteins were assessed by an indirect immunofluorescence assay, as described previously (11). HeLa cells were transfected for 24 h with wild-type or HNF1A variant plasmids using the protocol described by jetPRIME (Polyplus). HNF-1A was detected using primary antibody anti-Xpress and secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (Thermo Fisher). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher). Finally, cells were analyzed on a TCS SP2 confocal microscope (Leica) with a ×63 objective. Images were analyzed with the Leica Application Suite (LAS). The MODY variant p.Q466* was included as a control for impaired localization (cytosolic retention) (34). A minimum of 200 cells was analyzed for nuclear versus nuclear and cytosolic staining.

DNA Binding Analysis

We used an in vitro coupled transcription and translation system (TNT Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System; Promega) for expression of HNF-1A proteins essentially as described before (34). An electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed to investigate the ability of equal amounts of in vitro synthesized HNF-1A proteins to bind to a [γ-32P]-radiolabeled rat albumin oligonucleotide containing an HNF-1A binding site. For this, bound products were analyzed by 6% DNA retardation gel electrophoresis (Thermo Fisher), followed by autoradiography (LAS-1000 Plus; Fujifilm Medical System). DNA binding was quantified using the intensity of HNF-1A protein-oligonucleotide complexes (from two independent expression reactions and three separate gel analyses) using Image Gauge 3.12 software (Fujifilm Medical Systems). MODY variants p.P112L and p.R263C were included as controls for severely reduced and no DNA binding ability, respectively.

Protein Expression Analysis

Wild-type and HNF-1A variant protein expression levels were measured using cell lysates from transfected HeLa cells lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with HNF-1A antibody (Cell Signaling). We quantified protein levels by densitometric analysis and normalized to actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Statistical Analyses

Experiments were performed on at least three independent occasions with three parallels, unless otherwise specified, and all data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student t test, and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

We used counts from the Supplementary Table 3 in Flannick et al. (23) for all statistical analyses to discern whether groups of variants were associated with diabetes in the three study cohorts. Variants were grouped based on classifiers (bioinformatics vs. functional evaluation). Counts of carriers were summarized separately for individuals with diabetes and control subjects for each class in each cohort and meta-analyzed using a fixed-effect model performed by the method of Mantel and Haenszel, as implemented with the Metan version 9 module in Stata/IC 13.0 software (StataCorp LP), with each study cohort treated as a separate group. All results are presented as ORs with 95% CIs with nominal P values from the meta-analysis.

Results

In this study, we evaluated 27 nonsynonymous HNF1A variants with MAF <1% found in individuals from three population-based cohorts described in the research design and methods (23). Of these, 18 variants have been reported before in the literature, and 9 variants have not been reported previously (Table 1). We found no association with type 2 diabetes for the whole group of 27 rare nonsynonymous HNF1A alleles (n = 62 carriers) (MAF 0.75%; OR 1.52; 95% CI 0.86–2.69; P = 0.15) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Functional and bioinformatic evaluation of rare nonsynonymous HNF1A variants from the study cohorts (23)

| Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Functional evaluation (this study) |

Previously reported |

Bioinformatic evaluation/population frequencies |

Variant classification |

Number of variant carriers |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional activity | DNA binding | Nuclear localization | Phenotype/family segregation | Functional effect | HGMD | Ref. | SIFT | PolyPhen-2 (HumVar) | Align GVGD | MutationTaster | CADD | ExAC | 1000G | Bioinformatic evaluation (this study) | According to clinical diagnostic practice | FHS cohort |

JHS cohort |

T2D cohort |

|||||

| DM | No DM | DM | No DM | DM | No DM | ||||||||||||||||||

| (n = 218) (n/MAF) |

(n = 1,435) (n/MAF) |

(n = 346) (n/MAF) |

(n = 1,345) (n/MAF) |

(n = 362) (n/MAF) |

(n = 409) (n/MAF) |

||||||||||||||||||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||||||||||||

| c.335C>T | P112L | 14 | 19 | — | MODY/yes | TA <30%, DNA-binding 30–40% (19, 34); TA ∼50% (35) | MODY | (19, 34, 35, 47) | Del | Prob | C65 | Disease causing | 34 | — | — | Likely pathogenic (5/5) | Class 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| c.1340C>T | P447L | 18 | — | — | MODY/yes | TA ≤20%, low DNA-binding (18, 48) | MODY | (2, 18, 37, 48, 49) | Del | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 34 | — | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| c.787C>T | R263C | — | 5 | — | MODY/T2D/yes | TA <30%, no DNA-binding (19, 36) | MODY | (19, 36, 50) | Del | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 35 | 9.13 × 10−6 | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| c.1396C>T | Q466* | — | — | 15 | MODY/NA | TA <30%, NL ∼3% (19, 34) | MODY | (19, 34) | — | — | — | — | 40 | — | — | NA | Class 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| c.965A>G | Y322C | 30 | — | 63 | Uncertain MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (51) | Del | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 24,7 | 0.000132 | Yes | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 3 | — | — | 3 (0.43) | 3 (0.11) | — | — |

| c.818_820del | E275del | 30 | 44 | 68 | MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (52) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | NA | Class 3 | 1 (0.23) | 0 | — | — | — | — |

| c.392G>A | R131Q | 35 | 58 | 59 | MODY/yes | TA ∼50% (18, 53) | MODY | (2, 18, 53, 54) | Del | Prob | C35 | Disease causing | 34 | 8.25 × 10−6 | — | Likely pathogenic (5/5) | Class 3 | — | — | — | — | 1 (0.14) | 0 |

| c.1522G>A | E508K | 40 | — | 59 | Uncertain MODY/T2D/no | TA ∼40%; NL ∼60% (11) | MODY | (11, 51, 55) | Del | Poss | C0 | Disease causing | 32 | 0.0004403 | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 2 | 1 (0.23) | 0 | — | — | — | — |

| c.1405C>T | H469Y | 41 | — | 80 | MODY/T1D/no | NA | — | (25, 52, 56) | Del | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 23,5 | 0.0001613 | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 2 | 0 | 2 (0.07) | 0 | 1 (0.037) | — | — |

| c.1544C>A | T515K | 46 | — | 74 | Uncertain MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (51) | Del | Poss | C0 | Disease causing | 35 | 6.634 × 10−5 | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 3 | — | — | 1 (0.15) | 0 | — | — |

| c.1541A>G | H514R | 51 | — | 57 | T2D/no | NA | T2D | (57, 58) | Tol | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 22,5 | 0.0002903 | — | Unlikely pathogenic (3/5) | Class 3 | 1 (0.23) | 0 | — | — | — | — |

| c.1513C>A | H505N | 54 | — | 64 | Uncertain MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (51) | Tol | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 26,1 | 0.000108 | Yes | Unlikely pathogenic (3/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | — | — | — | — |

| c. 298C>A | Q100K | 57 | 71 | 86 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Tol | Ben | C0 | Disease causing | 20,9 | 1.162 × 10−6 | — | Unlikely pathogenic (2/5) | Class 3 | — | — | 1 (0.15) | 0 | — | — |

| c.307G>A | V103M | 59 | 65 | 78 | MODY/NA | NA | — | (59, 60) | Tol | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 25,6 | 3.61 × 10−5 | — | Unlikely pathogenic (3/5) | Class 2 | 1 (0.23) | 0 | — | — | — | — |

| c.1696C>A | H566N | 59 | — | 73 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Tol | Ben | C0 | Disease causing | 23,1 | — | — | Unlikely pathogenic (2/5) | Class 3 | — | — | 0 | 1 (0.037) | — | — |

| c.142G>A | E48K | 61 | — | 75 | Uncertain MODY/T1D/conflicting results | NA | MODY | (61, 62) | Tol | Ben | C0 | Disease causing | 18,32 | 0.0001564 | — | Unlikely pathogenic (2/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | — | — | — | — |

| c.1360A>G | S454G | 64 | — | 78 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Tol | Ben | C0 | Disease causing | 10,98 | — | — | Unlikely pathogenic (1/5) | Class 3 | — | — | — | — | 1 (0.14) | 0 |

| c.1469T>C | M490T | 63 | — | 73 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Del | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 25,8 | 9.36 × 10−6 | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 3 | — | — | — | — | 0 | 1 (0.12) |

| c.1748G>A | R583Q | 63 | — | 78 | Late-onset NIDDM/T2D/no | NA | MODY | (63–65) | Tol | Ben | C0 | Disease causing | 23,6 | 0.0005041 | Yes | Unlikely pathogenic (2/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 4 (0.14) | — | — | — | — |

| c.92G>A | G31D | 65 | — | 81 | Uncertain MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (61, 66–69) | Del | Ben | C0 | Disease causing | 22,8 | 0.0007105 | Yes | Unlikely pathogenic (3/5) | Class 2 | 0 | 5 (0.17) | 1 (0.15) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.12) |

| c.854C>T | T285M | 64 | — | 87 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Del | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 24 | 2.889 × 10−5 | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | — | — | — | — |

| c.185A>G | N62S | 65 | — | 70 | Uncertain MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (64) | Tol | Poss | C0 | Disease causing | 22,1 | 0.0001206 | — | Unlikely pathogenic (3/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | 0 | 1 (0.037) | — | — |

| c.1532A>G | Q511R | 66 | — | 73 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Del | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 28 | 1.66 × 10−5 | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | — | — | — | — |

| c.1729C>G | H577D | 69 | — | 74 | T1D/uncertain MODY/no | NA | — | (70, 71) | Del | Ben | C0 | Disease causing | 24,2 | 0.0001424 | Yes | Unlikely pathogenic (3/5) | Class 2 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | — | — | — | — |

| c.533C>T | T178I | 67 | — | 79 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Del | Ben | C0 | Disease causing | 18,39 | — | — | Unlikely pathogenic (3/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | — | — | — | — |

| c.827C>G | A276G | 69 | — | 70 | Uncertain MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (51, 72) | Del | Poss | C0 | Disease causing | 28,7 | — | — | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | — | — | — | — |

| c.1165T>G | L389V | 68 | — | 79 | Uncertain MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (51, 73, 74) | Tol | Poss | C0 | Disease causing | 12,49 | 0.0005422 | Yes | Unlikely pathogenic (2/5) | Class 2 | — | — | 4 (0.58) | 14 (0.52) | — | — |

| c.290C>T | A97V | 71 | — | 85 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Del | Poss | C65 | Disease causing | 25,2 | 6.689 × 10−5 | — | Likely pathogenic (5/5) | Class 3 | — | — | 0 | 1 (0.037) | — | — |

| c.824A>C | E275A | 78 | — | 81 | NA/NA | NA | — | — | Del | Prob | C0 | Disease causing | 26,5 | 3.661 × 10−5 | Yes | Likely pathogenic (4/5) | Class 3 | 0 | 1 (0.035) | — | — | — | — |

| c.341G>A | R114H | 83 | — | 81 | Uncertain MODY/NA | NA | MODY | (74, 75) | Tol | Ben | C0 | Polymorphism | 22,9 | 3.318 × 10−5 | — | Unlikely pathogenic (1/5) | Class 3 | — | — | 1 (0.15) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.12) |

| c.586A>G |

T196A |

101 |

— |

85 |

Uncertain MODY/NA |

NA |

MODY |

(51, 76) |

Tol |

Ben |

C0 |

Disease causing |

14,81 |

0.0003306 |

— |

Unlikely pathogenic (1/5) |

Class 2 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0 |

1 (0.12) |

| c.293C>T | A98V | 62 | — | 84 | Risk T2D | Reduced effect in combination with L27 | Serum C-peptide and insulin response | (13, 16, 77) | Del | Ben | C0 | Polymorphism | 23,4 | 0.03672 | Yes | Unlikely pathogenic (2/5) | Class 1 | 9 (2.06) | 53 (1.85) | 4 (0.58) | 16 (0.59) | 32 (4.4) | 21 (2.6) |

| c.1460G>A | S487N | 83 | — | 83 | Cardiovascular disease, increased risk/earlier age of diagnosis | Low | Cardiovascular disease, increased risk, association with | (16, 74, 78, 79) | Del | Ben | C0 | Polymorphism | 15,32 | 0.3465 | Yes | Unlikely pathogenic (2/5) | Class 1 | 148 (33.9) | 890 (31) | 90 (13) | 336 (12.5) | 227 (31.4) | 249 (30.4) |

| c.79A>C | L27I* | 86 | — | 86 | Risk T2D | I27L: small effect | Insulin resistance, association with | (13, 62, 74) | Tol | Ben | C0 | Polymorphism | 25,6 | 0.3533 | Yes | Unlikely pathogenic (1/5) | Class 1 | 165 (37.8) | 936 (32.6) | 95 (13.7) | 318 (11.8) | 259 (35.7) | 277 (33.9) |

The variants are ranged based on their functional effect, and MODY control variants and common variants are separated from the rare HNF1A variants from the study cohorts by a solid line. We used five in silico tools for the bioinformatics classification: SIFT, PolyPhen-2 (HumVar), Align GVGD, MutationTaster, and CADD. SIFT predictions: Del, deleterious; Tol, tolerated. PolyPhen-2 (HumVar) predictions: Prob, probably damaging, Poss, possibly damaging; Ben, benign. Align GVGD: the prediction classes form a spectrum (C0, C35, C65), with C65 most likely to interfere with function and C0 least likely. MutationTaster: Disease causing or polymorphism. For CADD we used a cutoff threshold of 15 (>15 pathogenic). For a variant to be classified as likely pathogenic, it was scored as pathogenic in at least four of the five variant interpretation software tools used. For a variant to be classified as unlikely pathogenic, it was scored as pathogenic in less than four of the five variant interpretation software tools used.

DM, diabetes mellitus; n, number of carriers; NA, not annotated; 1000G, 1000 Genomes.

Table 2.

Association analysis between bioinformatics classification of HNF1A rare variants and type 2 diabetes in study cohorts

| Bioinformatic classification | FHS cohort |

JHS cohort |

Extreme T2D cohort |

Meta-analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM (n = 218) | No DM (n = 1,435) | DM (n = 346) | No DM (n = 1,345) | DM (n = 362) | No DM (n = 409) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | OR (95% CI)* | P value | |

| All rare variants | 4 (1.8) | 20 (1.4) | 11 (3.2) | 21 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.0) | 1.52 (0.86–2.69) | 0.15 |

| Likely pathogenic | 1 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 4 (1.2) | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 2.02 (0.73–5.60) | 0.18 |

| Likely benign | 3 (1.4) | 14 (1.0) | 7 (2.0) | 16 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.7) | 1.34 (0.67–2.69) | 0.40 |

We used five in silico tools for the bioinformatics classification: SIFT, PolyPhen-2 (HumVar), Align GVGD, MutationTaster, and CADD (Table 1). For a variant to be classified as likely pathogenic, it was scored as pathogenic in at least four of the five variant interpretation software tools used. For a variant to be classified as unlikely pathogenic, it was scored as pathogenic in less than four of the five variant interpretation software tools used.

DM, diabetes mellitus; n, number of carriers.

*ORs were estimated by formal fixed-effect meta-analysis performed by the method of Mantel and Haenszel.

Bioinformatics Classification

The variants were assigned to two classes, as described in research design and methods, using five in silico prediction tools (SIFT, PolyPhen2, CADD, MutationTaster, and Align GVGD) (Table 1). Following such a method, 11 of the 27 low-frequency nonsynonymous variants were classified as likely pathogenic (Table 1) and showed no association with diabetes risk (MAF 0.22%, OR 2.02; 95% CI 0.73–5.60; P = 0.18) (Table 2).

Functional Evaluation

We performed a separate evaluation of variant consequence on in vitro protein function. Because HNF-1A is a transcription factor, we performed two separate functional tests focusing on transactivation and nuclear localization of all 27 rare variants. For comparison, we also analyzed three of the common HNF1A variants (MAF >1%) identified in the cohorts (p.L27I, p.A98V, and p.S487N) and four previously characterized MODY3-causing variants (p.P112L, p.R263C, p.P447L, and p.Q466*) (18,19,34). The positions of these variants within the HNF-1A protein sequence are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Position of HNF1A variants in the HNF-1A protein sequence identified in the study cohorts. Schematic illustration shows rare nonsynonymous HNF1A variants (orange), common variants (gray), and MODY3-associated variants (blue) identified in the cohorts studied (7). The total number of rare mutations reported in MODY families to date (25) is shown as the number for each functional domain.

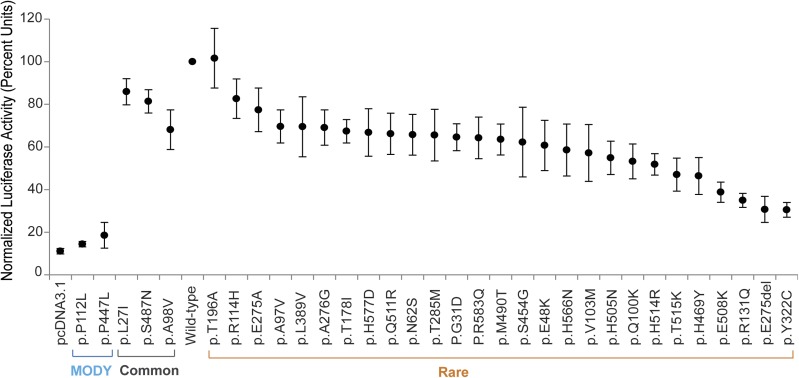

First, we investigated the effect of individual variants on HNF-1A transcriptional activity in transiently transfected HeLa cells using a luciferase reporter construct, whose expression is regulated by HNF-1A binding to a rat albumin promoter (Fig. 2). As a control for severely reduced transcriptional activity, we used two well-characterized MODY3-causing variants (p.P112L and p.P447L) (18,19). The individual effect of the 27 rare variants on normal HNF-1A transcriptional activity varied, ranging from no effect/nearly normal activity to substantial effect (<60% activity compared with wild-type) (Fig. 2), but could be clearly distinguished from the severe effects demonstrated by the MODY3-causing controls (<20% activity).

Figure 2.

Assessment of transcriptional activity of HNF-1A protein variants using a luciferase reporter assay. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with wild-type or variant HNF1A plasmids together with reporter plasmids pGL3-RA and pRL-SV40. Luciferase measurements are given in percentage activity compared with wild-type. Each point represents the mean (the range bars indicate the 95% CIs) of nine readings. Three parallel readings were conducted on each of 3 experimental days. Two MODY variants and three common variants were included in the study.

Second, we monitored the nuclear versus cytoplasmic localization of the HNF-1A variant proteins using transiently transfected HeLa cells (Fig. 3). This assay was designed to detect impaired nuclear protein transport, a loss-of-function mechanism described for certain MODY variants (19). A previously reported MODY3-causing variant, p.Q466*, known to be retained in the cytoplasm, was included for comparison (34). Most of the 27 HNF-1A variant proteins demonstrated efficient nuclear translocation similar to wild-type HNF-1A, with a strong immunofluorescent signal restricted to the cell nucleus in most of the cells counted (Fig. 3). A few variants showed a reduced number of cells with nuclear accumulation alone (<60%) but not to the extent of the p.Q466* MODY control variant included, demonstrating a strongly reduced number of cells with nuclear staining alone (<20%) and increased cytoplasmic accumulation. Functional data of all variants are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Analysis of nuclear localization of HNF-1A protein variants in HeLa cells. Cells were transiently transfected for 24 h and Xpress-epitope–tagged HNF-1A protein variants detected by immunofluorescence. A: Subcellular localization in a minimum of 200 cells was assessed for each HNF1A variant. The percentage of cells with nuclear accumulation alone is presented. B: Representative images of cells of the two most impaired nuclear localization variants. One MODY3 variant (p.Q466*) with abnormal subcellular localization was included as a control. HNF-1A was detected using tag-specific antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 (green). DNA staining (DAPI) is shown in blue. In more detail, the cytoplasmic signals of the cells expressing p.R131Q were more uniform, whereas the cells expressing p.H514R revealed a pattern resembling aggregated particles. For the purpose of clarity, the nuclei and cell membrane have been marked with a white line.

Diabetes Risk Prediction

We next tested whether the two functional assays could improve classification of variants that increase the risk of diabetes. Variants were first subdivided according to a range of different thresholds (percentage transcriptional activity or percentage nuclear localization compared with wild-type) (Table 3). Association with diabetes was then tested for each transactivation (TA) model. As summarized in Table 3, a model including variants having a modest effect on TA (>70% activity) or nuclear localization (>80% of all cells analyzed) did not perform differently from a model that includes all rare variants. In contrast, a model only including variants with a strong effect on normal HNF-1A function (i.e., <60% TA activity, or <70% in nuclear localization) compared with wild-type showed a strong and significant association with diabetes risk (OR 5.04; 95% CI 1.99–12.80; P = 0.0007; and OR 4.44; 95% CI 1.50–13.12; P = 0.007, respectively). Combining these two models did not increase the association compared with classification by TA only. Moreover, the effect sizes remained similar for the range of stricter classes (<40% and <50% activity compared with wild-type), albeit with decreasing levels of significance as fewer alleles met the stricter criteria.

Table 3.

Functional classification of HNF1A variants and their association with type 2 diabetes in the study cohorts (23)

| Classification model | FHS cohort |

JHS cohort |

Extreme T2D cohort |

Meta-analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM (n = 218) | No DM (n = 1,435) | DM (n = 346) | No DM (n = 1,345) | DM (n = 362) | No DM (n = 409) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | OR (95% CI)* | P value | |

| TA <40% | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 5.91 (1.69–20.68) | 0.005 |

| TA <50% | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0,3) | 0 (0) | 3.77 (1.22–11.70) | 0.02 |

| TA <60% | 4 (1.8) | 3 (0.2) | 5 (1.4) | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 5.04 (1.99–12.80) | 0.0007 |

| TA <70% | 4 (1.8) | 19 (1.3) | 10 (2.9) | 20 (1.5) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 1.67 (0.92–3.04) | 0.09 |

| TA <80% | 4 (1.8) | 20 (1.4) | 10 (2.9) | 21 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 1.60 (0.88–2.90) | 0.12 |

| NL <60% | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 9.85 (1.09–89.12) | 0.04 |

| NL <70% | 3 (1.4) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 4.44 (1.50–13.12) | 0.007 |

| NL <80% | 4 (1.8) | 11 (0.8) | 8 (2.3) | 19 (1.4) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 1.90 (0.99–3.64) | 0.05 |

| TA <60% or NL <60% | 4 (1.8) | 20 (1.4) | 10 (2.9) | 21 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 5.04 (1.99–12.80) | 0.0007 |

| TA <60% or NL <70% | 4 (1.8) | 4 (0.3) | 5 (1.4) | 6 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 4.19 (1.73–10.12) | 0.001 |

| TA >60% and NL >70% | 0 (0) | 17 (1.2) | 6 (1.7) | 16 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.0) | 0.77 (0.35–1.72) | 0.53 |

Selected cutoffs shown in boldface type. DM, diabetes mellitus; n, number of carriers; NL, nuclear localization; TA, transcriptional assay.

*ORs were estimated by formal fixed-effect meta-analysis performed by the method of Mantel and Haenszel.

Thus, our data suggest that a reduction to <60% of normal TA function is the best discriminator between diabetes risk and neutral HNF1A variants. By using this classification, we were able to classify as functionally impaired 11 variants (Y322C, E275del, R131Q, E508K, H469Y, T515K, H514R, Q100K, H505N, V103M, and H566N), with a cumulative carrier frequency of 0.44% (i.e., allele frequency of 0.22%) in the studied populations (Tables 1 and 3), and the remaining rare variants showed no evidence of association (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.35–1.72; P = 0.53) (Table 3). Notably, only 5 of the 11 functionally impaired variants had a consistently high pathogenicity score in the bioinformatics prediction tools (Table 1), illustrating the challenges with inferring biological function from in silico classifications alone.

Replication

As an independent replication of the observed associations, we searched the publically available Type 2 Diabetes Genetics Database (http://www.type2diabetesgenetics.org) for all rare HNF1A variants investigated in our assays. In that database, we identified 16 of the 27 studied variants (Supplementary Table 1). The class of functionally impaired alleles that were present in this database (n = 7 variants) was significantly associated with type 2 diabetes (OR 3.01; 95% CI 1.87–4.83; P = 2 × 10−6), but no association was seen for the nonimpaired class (P = 0.70) (Table 4). The replication signal was dominated by the Mexican p.E508K variant, but the remaining variants also showed a consistent direction of effect (OR 1.63; 95% CI 0.85–3.10; P = 0.14). These numbers support the chosen thresholds as predictive of diabetes risk, although much larger samples of variant carriers will be necessary to fully calibrate the estimated risk from functionally impaired HNF1A variants.

Table 4.

Enrichment of functionally impaired HNF1A alleles in the type 2 diabetes genetics database*

| Case subjects (n = 8,379) | Control subjects (n = 8,478) | OR (95% CI)† | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Impaired | 68 (0.81) | 23 (0.27) | 3.01 (1.87–4.83) | 2.0 × 10−6 |

| Nonimpaired | 35 (0.42) | 39 (0.46) | 0.91 (0.58–1.44) | 0.70 |

*Web site address: http://www.type2diabetesgenetics.org.

†ORs and corresponding P values were calculated using the χ2 test.

HNF-1A Loss-of-Function Mechanism

To better understand the molecular mechanism for the loss of function mediated by the predicted risk variants (according to our transactivation assay), we extended our functional investigations for the 11 variants that demonstrated the strongest association with diabetes risk in the cohorts (activity <60% compared with wild-type). Because 4 of the 11 variants are located in the DNA-binding domain of HNF-1A, we used an electrophoretic mobility shift assay to test whether impaired DNA binding could be the explanation for the reduced TA (Supplementary Fig. 1). Two MODY3 variants (p.P112L and p.R263C) previously shown to severely reduce DNA binding were included for comparison. Using equal amounts of wild-type versus variant proteins, we observed significantly reduced DNA binding (P < 0.05) for one variant (p.E275del) (Supplementary Fig. 1A and B), explaining its inability to fully transactivate. The level of binding was, however, not as weak (44%) as the MODY-causing control variants included for severely reduced DNA binding (<20%).

We also questioned whether the low TA capacity of the 11 variants could be caused by reduced expression of HNF-1A. Indeed, we observed a significantly lower level of expressed protein (P < 0.05) for 4 of the 11 variants investigated (p.Y322C, p.E508K, p.H514R, and p.T515K) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Discussion

We have investigated the potential pathogenic effect of 27 rare HNF1A variants previously identified in the FHS and JHS population-based cohorts, and Swedish and Finnish type 2 diabetes case and control subjects ascertained from the extremes of genetic risk (23). Using traditional bioinformatics tools to classify these variants into likely/unlikely pathogenicity resulted in only a nonsignificant trend between their predicted pathogenicity and type 2 diabetes. Using functional assays, however, we revealed a model in which transcriptional activity of <60% was robustly associated with type 2 diabetes. We found a similar albeit weaker effect in an independent publicly available data set (www.type2diabetesgenetics.org) (P = 2.0 × 10−6), with some residual effect left after excluding the well-known p.E508K Mexican risk variant (P = 0.14). Studies of rare variants are intrinsically challenging, because power decreases rapidly with decreasing allele frequencies and effect estimates will have large uncertainties. The current sample is powered to detect an OR of >2.0 given variants present in 1% of the study population and an OR >2.9 for variants with a combined 0.44% carrier frequency such as found for the 60% TA threshold (at nominal significance) (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Thus, much larger replication samples are needed if the true effects of these rare variants are in the lower end of our risk estimate. Likewise, the small numbers of individuals carrying impaired variants make it challenging to disentangle possible difference among the three cohorts.

Although our functional assay demonstrated reduced HNF-1A function for 11 of the 27 rare variants, we emphasize that the degree of functional impairment (TA <60%) is much less pronounced than what is seen for true HNF1A MODY variants that show dominant disease transmission in families (Table 1). These variants show an almost complete lack of HNF-1A function with transcriptional activity and/or DNA binding <20% compared with the normal protein (18,19,34–37).

The penetrance of MODY variants is estimated at ∼63% by age 25, increases to 93.6% by age 50, and to 98.7% by age 75 (38). Although the clinical expression of MODY varies between families and even within families (39,40), most carriers will develop diabetes during their life-time compared with the two- to fivefold increased risk estimated for variants characterized in the current study. The effects are similar to the recently reported p.E508K variant associated with a fivefold increased type 2 diabetes risk in the Mexican and Latino population (11). The variant appears in ∼2.1% of individuals with type 2 diabetes and in 0.35% in control subjects in these populations but are apparently absent in other populations. The E508K allele has also demonstrated incomplete penetrance, suggesting that it is a moderate diabetes allele and different from the true HNF1A MODY variants that demonstrate high disease penetrance (38). Reduced penetrance of another HNF1A variant (G319S) and variable clinical presentation of type 2 diabetes has also been shown (12). The G319S variant, which is private for the Oji-Cree population and common among individuals with diabetes (40%), influences the age of onset of type 2 diabetes, BMI, and plasma glucose levels through a gene-dosage effect. Homozygous individuals for the S319 allele were diagnosed at an earlier age and had lower BMI and higher plasma glucose levels than the heterozygous (G319/S319) carriers (12).

Our findings may have clinical implications. Our data indicate that as much as 0.44% of the general population may carry HNF1A variants, with considerable effect on diabetes risk. Such information may lead to increased awareness of the relevance of HNF1A screening in diabetes laboratories in patients with a (non-MODY) late-onset type 2–like diabetes.

Moreover, compared with traditional bioinformatics tools, functional studies of HNF1A gene variants seem needed to better translate genomic signals and may be a faithful indicator of the true effect of these variants as risk factors for type 2 diabetes (this principle may be applicable also for other genes and change the way of how to investigate the effect of gene variants in complex diseases). Only 5 of the 11 variants identified as functionally impaired in our study were consistently scored as damaging by commonly used variant assessment software. Likewise, HGMD labeled many apparently neutral variants as MODY, which is in accordance with other studies showing that HGMD has to be used with caution (41). These limitations are not fully overcome by the manual five-class classification system used by many diagnostics laboratories, (42) including ours. This system is only applicable to Mendelian disease. Thus, most of the variants fall into the class 3 (variant of unknown significance) or class 2 (likely benign) categories (Table 1), as exemplified with the E508K variant that is associated with a fivefold increased risk of type 2 diabetes but does not show strong familial segregation and low penetrance compared with MODY criteria.

Although the magnitude of reduced HNF-1A function is larger for HNF1A variants causing MODY3 (38,43,44) compared with the reduced function observed for the rare HNF1A variants investigated in this report, a natural question is whether sulfonylurea treatment might be beneficial for subjects carrying HNF1A variants with <60% TA activity or <70% in the nuclear localization assay (11). To our knowledge, no studies have systematically explored whether the Oji-Cree or the Mexican Americans carrying HNF1A variants with some degree of functional impairment are more responsive to sulfonylurea compared with type 2 diabetes without the variants. Still, this might be interesting to explore in future clinical studies.

A limitation of our study is that the 27 HNF1A variants investigated were identified in relatively small cohorts and may not be representative across other samples and populations. However, our study was performed in two population-based cohorts of different genetic and environmental backgrounds (here Europeans and African Americans) (23), thus providing some evidence to support that this is not a restricted phenomenon in a particular cohort or ancestry group. Hence extending the study to surveys of an even wider range of human populations by investigating larger cohorts of multiethnic backgrounds will be important. By this, the relevance of personal genomic sequencing the HNF1A gene for disease risk prediction can be better evaluated (45).

The current study was restricted to functional investigations of variants in the most commonly affected MODY gene, HNF1A, where common variation with small effects on type 2 diabetes risk have also been found at least in some populations (11,12,16). Our findings illustrate that functional assays can pinpoint rare HNF1A variants of high effect on type 2 diabetes risk, thus suggesting that in-depth functional assays could be a fruitful approach to also detect additional low-frequency variants in other reported MODY genes (23), as was found for PPARG, a gene implicated in lipodystrophy and insulin resistance (46).

In conclusion, we have shown here that functional verification of the biological effect of rare HNF1A variants identified by high throughput sequencing of large populations is needed to distinguish impaired from neutral variants and to correctly estimate the risk for developing MODY and type 2 diabetes. Functional assays can play an important role in rigorous evaluation of variants’ causality. Until now, predictive genetic testing of variants causing type 2 diabetes has not been relevant because of small effects in few populations. To fully determine the true power of such risk variants, follow-up studies of functional analysis of gene variants from larger cohorts should be performed. Our study highlights the necessity of increased awareness regarding the relevance of MODY genes, and HNF1A in particular, in the contribution of type 2 diabetes risk.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Funding. This work was supported by grants and fellowships from the translational fund of Bergen Medical Research Foundation, KG Jebsen Foundation, University of Bergen, Research Council of Norway, Western Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse Vest), Norwegian Diabetes Foundation, and European Research Council. L.B. and P.R.N. obtained funding.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article reported.

Author Contributions. L.A.N., I.A., J.F., J.M., N.B., S.J., and L.B. analyzed and interpreted the data. L.A.N., S.J., L.B., and P.R.N. wrote the manuscript. I.A., J.F., J.M., A.M., L.G., D.A., S.J., L.B., and P.R.N. contributed with intellectual input and revision of the manuscript. I.A., S.J., L.B., and P.R.N. designed the study. J.F. and S.J. performed the statistical analyses. L.A.N. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this work were presented in abstract form at the at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes Annual Meeting, Vienna, Austria, 15–19 September 2014, and at the 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Boston, MA, 5–9 June 2015.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db16-0460/-/DC1.

D.A. is currently affiliated with Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Molven A, Njølstad PR. Role of molecular genetics in transforming diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2011;11:313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamagata K, Oda N, Kaisaki PJ, et al. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY3). Nature 1996;384:455–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Froguel P, Vaxillaire M, Sun F, et al. Close linkage of glucokinase locus on chromosome 7p to early-onset non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Nature 1992;356:162–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hattersley AT, Turner RC, Permutt MA, et al. Linkage of type 2 diabetes to the glucokinase gene. Lancet 1992;339:1307–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamagata K, Furuta H, Oda N, et al. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1). Nature 1996;384:458–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horikawa Y, Iwasaki N, Hara M, et al. Mutation in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta gene (TCF2) associated with MODY. Nat Genet 1997;17:384–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, Patch AM, et al.; Neonatal Diabetes International Collaborative Group . Insulin mutation screening in 1,044 patients with diabetes: mutations in the INS gene are a common cause of neonatal diabetes but a rare cause of diabetes diagnosed in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes 2008;57:1034–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy MI. Genomics, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2339–2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winckler W, Weedon MN, Graham RR, et al. Evaluation of common variants in the six known maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) genes for association with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2007;56:685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris AP, Ferreira T. Fine-mapping type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci with the Metabochip. In 63rd Annual Meeting of The American Society of Human Genetics Boston,MA, 2013, p. Abstract 768W [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estrada K, Aukrust I, Bjørkhaug L, et al.; SIGMA Type 2 Diabetes Consortium . Association of a low-frequency variant in HNF1A with type 2 diabetes in a Latino population. JAMA 2014;311:2305–2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegele RA, Cao H, Harris SB, Hanley AJ, Zinman B. The hepatic nuclear factor-1alpha G319S variant is associated with early-onset type 2 diabetes in Canadian Oji-Cree. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:1077–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaulton KJ, Ferreira T, Lee Y, et al.; DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium . Genetic fine mapping and genomic annotation defines causal mechanisms at type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. Nat Genet 2015;47:1415–1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winckler W, Burtt NP, Holmkvist J, et al. Association of common variation in the HNF1alpha gene region with risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2005;54:2336–2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weedon MN, Owen KR, Shields B, et al. A large-scale association analysis of common variation of the HNF1alpha gene with type 2 diabetes in the U.K. Caucasian population. Diabetes 2005;54:2487–2491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmkvist J, Cervin C, Lyssenko V, et al. Common variants in HNF-1 alpha and risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2006;49:2882–2891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamagata K, Yang Q, Yamamoto K, et al. Mutation P291fsinsC in the transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha is dominant negative. Diabetes 1998;47:1231–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaxillaire M, Abderrahmani A, Boutin P, et al. Anatomy of a homeoprotein revealed by the analysis of human MODY3 mutations. J Biol Chem 1999;274:35639–35646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjørkhaug L, Sagen JV, Thorsby P, Søvik O, Molven A, Njølstad PR. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha gene mutations and diabetes in Norway. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:920–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Triggs-Raine BL, Kirkpatrick RD, Kelly SL, et al. HNF-1alpha G319S, a transactivation-deficient mutant, is associated with altered dynamics of diabetes onset in an Oji-Cree community. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:4614–4619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Małecki M, Skupień J. Problems in differential diagnosis of diabetes types. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2008;118:435–440 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy MI. Genomic medicine at the heart of diabetes management. Diabetologia 2015;58:1725–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flannick J, Beer NL, Bick AG, et al. Assessing the phenotypic effects in the general population of rare variants in genes for a dominant Mendelian form of diabetes. Nat Genet 2013;45:1380–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odom DT, Zizlsperger N, Gordon DB, et al. Control of pancreas and liver gene expression by HNF transcription factors. Science 2004;303:1378–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colclough K, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Saint-Martin C, Flanagan SE, Ellard S. Mutations in the genes encoding the transcription factors hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha and 4 alpha in maturity-onset diabetes of the young and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Hum Mutat 2013;34:669–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol 1979;110:281–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sempos CT, Bild DE, Manolio TA. Overview of the Jackson Heart Study: a study of cardiovascular diseases in African American men and women. Am J Med Sci 1999;317:142–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berglund G, Eriksson KF, Israelsson B, et al. Cardiovascular risk groups and mortality in an urban Swedish male population: the Malmö Preventive Project. J Intern Med 1996;239:489–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc 2009;4:1073–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet 2014;46:310–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010;7:248–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavtigian SV, Deffenbaugh AM, Yin L, et al. Comprehensive statistical study of 452 BRCA1 missense substitutions with classification of eight recurrent substitutions as neutral. J Med Genet 2006;43:295–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathe E, Olivier M, Kato S, Ishioka C, Hainaut P, Tavtigian SV. Computational approaches for predicting the biological effect of p53 missense mutations: a comparison of three sequence analysis based methods. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34:1317–1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bjørkhaug L, Ye H, Horikawa Y, Søvik O, Molven A, Njølstad PR. MODY associated with two novel hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha loss-of-function mutations (P112L and Q466X). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;279:792–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu JY, Chan V, Zhang WY, Wat NM, Lam KS. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha gene in Chinese MODY families: prevalence and functional analysis. Diabetologia 2002;45:744–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Q, Yamagata K, Yamamoto K, et al. Structure/function studies of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha, a diabetes-associated transcription factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999;266:196–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soutoglou E, Viollet B, Vaxillaire M, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M, Talianidis I. Transcription factor-dependent regulation of CBP and P/CAF histone acetyltransferase activity. EMBO J 2001;20:1984–1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearson ER, Starkey BJ, Powell RJ, Gribble FM, Clark PM, Hattersley AT. Genetic cause of hyperglycaemia and response to treatment in diabetes. Lancet 2003;362:1275–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fajans SS, Bell GI. Phenotypic heterogeneity between different mutations of MODY subtypes and within MODY pedigrees. Diabetologia 2006;49:1106–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miedzybrodzka Z, Hattersley AT, Ellard S, et al. Non-penetrance in a MODY 3 family with a mutation in the hepatic nuclear factor 1alpha gene: implications for predictive testing. Eur J Hum Genet 1999;7:729–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorschner MO, Amendola LM, Turner EH, et al.; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grand Opportunity Exome Sequencing Project . Actionable, pathogenic incidental findings in 1,000 participants’ exomes. Am J Hum Genet 2013;93:631–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plon SE, Eccles DM, Easton D, et al.; IARC Unclassified Genetic Variants Working Group . Sequence variant classification and reporting: recommendations for improving the interpretation of cancer susceptibility genetic test results. Hum Mutat 2008;29:1282–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Søvik O, Njølstad P, Følling I, Sagen J, Cockburn BN, Bell GI. Hyperexcitability to sulphonylurea in MODY3. Diabetologia 1998;41:607–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shepherd M, Shields B, Ellard S, Rubio-Cabezas O, Hattersley AT. A genetic diagnosis of HNF1A diabetes alters treatment and improves glycaemic control in the majority of insulin-treated patients. Diabet Med 2009;26:437–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shepherd M, Ellis I, Ahmad AM, et al. Predictive genetic testing in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY). Diabet Med 2001;18:417–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Majithia AR, Flannick J, Shahinian P, et al.; GoT2D Consortium; NHGRI JHS/FHS Allelic Spectrum Project; SIGMA T2D Consortium; T2D-GENES Consortium . Rare variants in PPARG with decreased activity in adipocyte differentiation are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:13127–13132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hameed S, Ellard S, Woodhead HJ, et al. Persistently autoantibody negative (PAN) type 1 diabetes mellitus in children. Pediatr Diabetes 2011;12:142–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas H, Badenberg B, Bulman M, et al. Evidence for haploinsufficiency of the human HNF1alpha gene revealed by functional characterization of MODY3-associated mutations. Biol Chem 2002;383:1691–1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansen T, Eiberg H, Rouard M, et al. Novel MODY3 mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha gene: evidence for a hyperexcitability of pancreatic beta-cells to intravenous secretagogues in a glucose-tolerant carrier of a P447L mutation. Diabetes 1997;46:726–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwasaki N, Oda N, Ogata M, et al. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha/MODY3 gene in Japanese subjects with early- and late-onset NIDDM. Diabetes 1997;46:1504–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bellanné-Chantelot C, Carette C, Riveline JP, et al. The type and the position of HNF1A mutation modulate age at diagnosis of diabetes in patients with maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY)-3. Diabetes 2008;57:503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tatsi C, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Vazeou-Gerassimidi A, et al. The spectrum of HNF1A gene mutations in Greek patients with MODY3: relative frequency and identification of seven novel germline mutations. Pediatr Diabetes 2013;14:526–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ekholm E, Nilsson R, Groop L, Pramfalk C. Alterations in bile acid synthesis in carriers of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α mutations. J Intern Med 2013;274:263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delvecchio M, Ludovico O, Menzaghi C, et al. Low prevalence of HNF1A mutations after molecular screening of multiple MODY genes in 58 Italian families recruited in the pediatric or adult diabetes clinic from a single Italian hospital. Diabetes Care 2014;37:e258–e260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Forlani G, Zucchini S, Di Rocco A, et al. Double heterozygous mutations involving both HNF1A/MODY3 and HNF4A/MODY1 genes: a case report. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2336–2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bennett JT, Vasta V, Zhang M, Narayanan J, Gerrits P, Hahn SH. Molecular genetic testing of patients with monogenic diabetes and hyperinsulinism. Mol Genet Metab 2015;114:451–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Behn PS, Wasson J, Chayen S, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha coding mutations are an uncommon contributor to early-onset type 2 diabetes in Ashkenazi Jews. Diabetes 1998;47:967–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gragnoli C, Cockburn BN, Chiaramonte F, et al. Early-onset type II diabetes mellitus in Italian families due to mutations in the genes encoding hepatic nuclear factor 1 alpha and glucokinase. Diabetologia 2001;44:1326–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Balamurugan K, Bjørkhaug L, Mahajan S, et al. Structure-function studies of HNF1A (MODY3) gene mutations in South Indian patients with monogenic diabetes. Clin Genet 2016;90:486–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radha V, Ek J, Anuradha S, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Mohan V. Identification of novel variants in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha gene in South Indian patients with maturity onset diabetes of young. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:1959–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thanabalasingham G, Huffman JE, Kattla JJ, et al. Mutations in HNF1A result in marked alterations of plasma glycan profile. Diabetes 2013;62:1329–1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Møller AM, Dalgaard LT, Pociot F, Nerup J, Hansen T, Pedersen O. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha gene in Caucasian families originally classified as having type I diabetes. Diabetologia 1998;41:1528–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Urhammer SA, Rasmussen SK, Kaisaki PJ, et al. Genetic variation in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha gene in Danish Caucasians with late-onset NIDDM. Diabetologia 1997;40:473–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ellard S, Colclough K. Mutations in the genes encoding the transcription factors hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha (HNF1A) and 4 alpha (HNF4A) in maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Hum Mutat 2006;27:854–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Owen KR, Stride A, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Etiological investigation of diabetes in young adults presenting with apparent type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2088–2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chèvre JC, Hani EH, Boutin P, et al. Mutation screening in 18 Caucasian families suggest the existence of other MODY genes. Diabetologia 1998;41:1017–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rose RB, Bayle JH, Endrizzi JA, Cronk JD, Crabtree GR, Alber T. Structural basis of dimerization, coactivator recognition and MODY3 mutations in HNF-1alpha. Nat Struct Biol 2000;7:744–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rebouissou S, Vasiliu V, Thomas C, et al. Germline hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha and 1beta mutations in renal cell carcinomas. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shankar RK, Ellard S, Standiford D, et al. Digenic heterozygous HNF1A and HNF4A mutations in two siblings with childhood-onset diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2013;14:535–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McDonald TJ, Colclough K, Brown R, et al. Islet autoantibodies can discriminate maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) from Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2011;28:1028–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lambert AP, Ellard S, Allen LI, et al. Identifying hepatic nuclear factor 1alpha mutations in children and young adults with a clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:333–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poitou C, Francois H, Bellanne-Chantelot C, et al. Maturity onset diabetes of the young: clinical characteristics and outcome after kidney and pancreas transplantation in MODY3 and RCAD patients: a single center experience. Transpl Int 2012;25:564–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Terryn S, Tanaka K, Lengelé JP, et al. Tubular proteinuria in patients with HNF1α mutations: HNF1α drives endocytosis in the proximal tubule. Kidney Int 2016;89:1075–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bodian DL, McCutcheon JN, Kothiyal P, et al. Germline variation in cancer-susceptibility genes in a healthy, ancestrally diverse cohort: implications for individual genome sequencing. PLoS One 2014;9:e94554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pihoker C, Gilliam LK, Ellard S, et al.; SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group . Prevalence, characteristics and clinical diagnosis of maturity onset diabetes of the young due to mutations in HNF1A, HNF4A, and glucokinase: results from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:4055–4062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Galán M, García-Herrero CM, Azriel S, et al. Differential effects of HNF-1α mutations associated with familial young-onset diabetes on target gene regulation. Mol Med 2011;17:256–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Sulem P, et al. Identification of low-frequency and rare sequence variants associated with elevated or reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2014;46:294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang Y, Zhou TC, Liu YY, et al. Identification of HNF4A mutation p.T130I and HNF1A mutations p.I27L and p.S487N in a Han Chinese family with early-onset maternally inherited type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res 2016;2016:3582616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Buchbinder S, Zorn M, Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP, Müller M, Schilling T. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) caused by a novel nonsense mutation E41X in the HNF-1α gene. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2011;119:182–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.