Abstract

In this article, we analyze the research experiences associated with a longitudinal qualitative study of residents’ care networks in assisted living. Using data from researcher meetings, field notes, and memos, we critically examine our design and decision making and accompanying methodological implications. We focus on one complete wave of data collection involving 28 residents and 114 care network members in four diverse settings followed for 2 years. We identify study features that make our research innovative, but that also represent significant challenges. They include the focus and topic; settings and participants; scope and design complexity; nature, modes, frequency, and duration of data collection; and analytic approach. Each feature has methodological implications, including benefits and challenges pertaining to recruitment, retention, data collection, quality, and management, research team work, researcher roles, ethics, and dissemination. Our analysis demonstrates the value of our approach and of reflecting on and sharing methodological processes for cumulative knowledge building.

Keywords: caregivers / caretaking, families, long-term health care, longitudinal studies, grounded theory, ethnography, southeastern United States

Qualitative research plays an important role in capturing the experiences of giving and receiving care, including the intersection of formal and informal care (e.g., Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003). Often by necessity, most qualitative research on care relationships and networks is small-scale, incorporates the perspectives of only one or two stakeholders, or involves a cross-sectional design, limiting explanatory power. Our ongoing grounded theory study of residents’ care networks in assisted living, “Convoys of Care: Developing Collaborative Care Partnerships in Assisted Living” involves an innovative complex, large-scale longitudinal research design intended to address these limitations and advance theoretical, empirical, and methodological knowledge.

In this article, we systematically and critically examine our research design and fieldwork experiences and discuss their methodological implications, including lessons learned. Invoking Goffman’s (1959, p. 112) dramaturgical metaphor, we expose our study’s “backstage” by sharing our methodological journey (i.e., the content and trajectory of our approach and research processes) from beginning to the study’s midpoint and completion of the first of two data collection waves. Our focus is on methodological issues. Thus, we present study findings only as they relate to research practices. Discussing methodological issues in depth is not routine scholarly practice, particularly beyond research-team boundaries, but doing so can inform future data collection, facilitate cumulative knowledge building, and lead to scientific advancement.

We begin the examination of our study by contextualizing our research within the broader scientific literature and presenting the key features of our study, including its focus, settings and participants, scope and design, nature and modes of data collection, and analytical approach. Next, we outline the analytical process we used to identify key methodological themes and understand their relationships to key study features. Finally, we examine these relationships, pointing out both the challenges and advantages of each and the lessons we have learned to inform future research, including the second wave of our study.

Research Context

Most frail individuals who receive care, including older adults, are embedded in care networks that involve formal and informal caregivers, require negotiation between parties, and evolve over time in response to multilevel factors and contexts (Gaugler, 2005; Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013). Increasingly, researchers acknowledge the frequent intersections of informal and formal care and the need to understand these linkages (Carpentier & Grenier, 2012), yet existing research does not offer a comprehensive understanding of these networks and how best to study, strengthen, and maintain them. A potentially fruitful research site to examine these linkages is assisted living, a care setting where increasing numbers of older adults with complex care needs reside and where intersections of informal and formal care regularly occur.

Assisted living communities typically offer housing, housekeeping, meals, 24-hour oversight, social activities, and personal care (Carder, O’Keeffe, & O’Keeffe, 2015) and are simultaneously places of residence and sites of work and care. Residents tend to be frail individuals with multiple chronic conditions who require assistance with more than one activity of daily living; almost half have dementia (Caffrey et al., 2012; Sengupta, Harris-Kojetin, & Caffrey, 2015). In the United States, many states prohibit assisted living workers from providing skilled nursing care (Carder et al., 2015), but a growing number of communities have registered nurses and licensed practical nurses on staff (Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Kemp, 2010; Rome & Harris-Kojetin, 2016). Externally provided care, including the full array of home health and hospice services, increasingly is available (Ball, Kemp, Hollingsworth, & Perkins, 2014; Park-Lee et al., 2011), but most hands-on care is provided by a largely unlicensed frontline workforce with low wages, few benefits, heavy workloads, and high turnover rates (Ball et al., 2010; Dill, Morgan, & Kalleberg, 2012). Informal care from families, friends, and volunteers constitutes another essential dimension of care (Ball et al., 2000; Kemp, 2012) as does resident self-care (Ball et al., 2004, 2005). Thus, in assisted living, residents’ care networks typically include multiple care partners, both formal and informal.

Adding to the complexity of assisted living are frequent resident transitions, including transfers to hospitals and other assisted living or rehabilitation facilities (Eckert, Carder, Morgan, Frankowski, & Roth, 2009), dementia care unit moves (Kelsey, Laditka, & Laditka, 2010), death (Ball et al., 2014), and widowhood (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2015). Residents’ informal care networks also are dynamic, owing to work, relationship, and other transitions (Ball et al., 2005). Assisted living social and physical environments constantly evolve in response to changes in residents and policies, administration and staff turnover, remodeling, and so forth (Morgan et al., 2014; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012).

Research has not fully addressed the complexity of care arrangements in assisted living or other care settings where formal and informal care intersect, including how and why care varies and is organized within care networks across time. No known in-depth studies, qualitative or otherwise, include all key stakeholders and involve multiple members of an individual’s informal care network. Understanding the dynamics and nuances of care processes within and across networks and over time requires research designs that typically are cost and time prohibitive, potentially fraught with methodological challenges, and hence seldom, if ever, fully planned and executed.

Key Study Features

We designed the “Convoys of Care” study to address the aforementioned content and methodological gaps in research. Consequently, certain features make our research innovative and poised to advance knowledge, but also represent formidable challenges. The key study features include the focus; settings and participants, scope and design; nature and modes of data collection; and analytic approach. Identifying and explaining these features helps contextualize our methodological themes.

Research Focus

The study focuses on care networks and is guided by the “Convoy of Care” model (Kemp et al., 2013). The overall goal is to learn how to support informal care and care convoys in assisted living in ways that promote residents’ ability to age in place with optimal resident and caregiver quality of life. Derived from our previous grounded theory studies, this care model modifies and expands Kahn and Antonucci’s (1980) “Convoy Model of Social Relations” to include formal care providers. Our care model defines care convoys as:

the evolving community or collection of individuals who may or may not have close personal connections to the recipient or to one another, but who provide care, including help with activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), socio-emotional care, skilled health care, monitoring, and advocacy (Kemp et al., 2013, p. 18).

Consistent with a grounded theory approach, our model acts as a framework that offers a set of “sensitizing concepts” (Blumer, 1969) that provides “a place to start” or “tentative tools” to guide initial data collection and analysis, and helps position the research within relevant theoretical, social, historical, and interactional contexts (Charmaz, 2006, p. 17).

Settings and Participants

Our study is set in eight diverse assisted living settings purposively selected to maximize variation in size, location, ownership, and resident characteristics and involves data collection in two waves. In this article, we focus on data collection from Wave 1 of the study conducted in four sites between 2013 and 2015. In Wave 1, we recruited 28 focal residents, including 11 with cognitive impairment, as well as 114 convoy members (i.e., assisted living staff, external care workers, and informal caregivers). We purposively selected Wave 1 residents to provide information-rich cases (Patton, 2015) that reflected variation in personal characteristics, functional status, and health conditions typical of assisted living residents nationwide, including some residents with substantial cognitive and physical impairment (see online Table 1). When the study is complete, we anticipate a total sample of 50 focal residents and approximately 225 convoy members. Final numbers may vary based on developing categories and emergent theory. Georgia State University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Scope and Design

The convoy model conceptualizes care as a dynamic process involving negotiation among and between multiple care partners over time (Kemp et al., 2013), implying the usefulness of a qualitative approach with an emphasis on understanding meaning, subjective experience, and fluidity of social relations. To understand convoys as they evolved, our study is longitudinal and, insofar as possible, involved all key stakeholders who participated in residents’ care, including their informal and assisted living caregivers and external care providers. We included residents frequently excluded from assisted living research, such as low-income, rural, racial and ethnic minority residents, and those without family.

Nature and Modes of Data Collection

We used multiple modes of data collection: (a) formal, semi-structured in-depth interviews; (b) participant observation; (c) informal interviews during observations and via phone, text, and email; and (d) review of residents’ facility records and visitor logs. Focal residents’ informed consent granted researchers permission to speak with convoy members about their health and care needs and to review facility records. In selecting residents and making initial decisions about their cognitive status, we were guided by assisted living staff, family members, and our own informal assessments— a strategy that has proven successful in our past assisted living research. We used National Institutes of Health (2009) guidelines to assess residents’ ability to provide informed consent. We approached potential resident participants, including those with cognitive impairment, and explained the study, including our approach, risks, and benefits. Following Palmer et al. (2005, p. 728), we asked residents with cognitive impairment: (a) “What is the purposed of the study?” (b) “What are the risks?” and (c) “What are the benefits?” For those unable to answer these questions and provide informed consent, we obtained proxy consent from legally authorized representatives and along with established assent procedures (see Black, Rabins, Sugarman, & Karlawish, 2010). Conceptualizing consent an ongoing process, we sought participants’ permission to speak with them prior to each interaction throughout the study.

Data Collection Duration and Frequency

We followed convoys prospectively over 2 years, or as long as the resident continued to live in the study home. This time frame reflects the national 22-month median assisted living length of stay (Caffrey et al., 2012) and allows for observation of continuity and change. Our goal was to have weekly contact with all focal residents, usually during facility visits, and twice-monthly contact with at least one informal convoy member. During Wave 1, researchers made a total of 809 field visits with 2,224 hours of observation and conducted 142 in-depth interviews. These activities yielded comprehensive, in-depth qualitative data on 28 convoys and four care communities (see online Table 2). This degree of depth and complexity of data collection necessitated an 18-member research team.

Analytic Approach

Our grounded theory approach involves constant comparison whereby data collection, hypothesis generation, and analysis occur simultaneously (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). Through this process, which is ongoing, we seek to understand and conceptualize care relationships, how they are patterned, and the multilevel factors affecting them. Our analysis involves examining convoys and sites holistically and as cases. Beginning in Wave 1, we developed case profiles for each convoy and setting to facilitate the identification of patterns and allow for comparison (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2014) within and across convoys and sites. Convoy profiles document properties and activities, changes over time, influential factors, divergent views, and outcomes for convoy members. Facility profiles describe each setting, focusing on key factors, such as size, location, staffing levels, care culture, policies, and practices and their influence on convoys. The creation of diagrams, charts, and memos are part of our analytic procedures. This cross-convoy/cross-setting analysis is enabling us to specify features characteristic of each convoy/setting or convoy/setting type and those that are shared across all 28 convoys and four sites.

Present Analysis

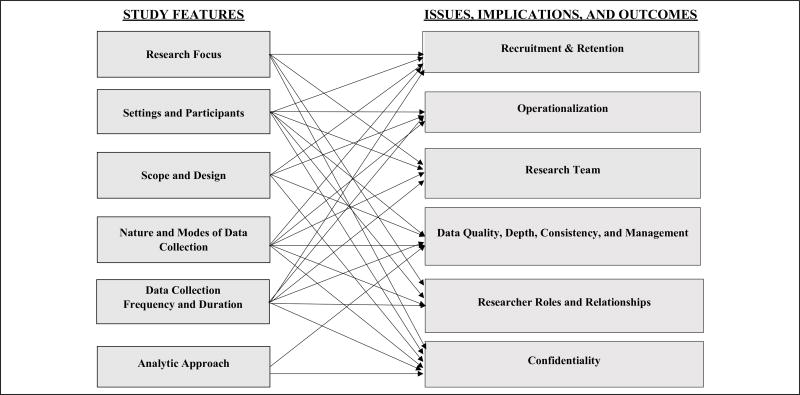

The analytic process for this article centered on methodological matters. In grounded theory, research processes evolve over the course of a study and also are iterative in the sense that researchers may need to “alter procedures to meet the demands of the research situation” (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, p. 13). Reflecting on our research experiences involved analysis of data pertaining to the research process that derived from notes from twice-monthly research-team meetings, field visits, and ongoing analytic memos. Relevant field note data included data coded “research,” which reflected any care interaction or activity participation by a member of the research team, and “operational memos,” which contain methodological issues encountered during the visit. During initial coding of these data, additional categories and subcategories were developed that identified specific study features (e.g., focus, scope, and design) and methodological issues, implications, and outcomes (e.g., recruitment and retention, confidentiality). Next, the relationships between these categories were established, resulting in the development of Figure 1. As Figure 1 illustrates, these features and accompanying areas of methodological influence operate individually and together to shape the research process.

Figure 1.

Study features and methodological issues, implications, and outcomes.

Methodological Issues, Implications, and Outcomes

As shown in Figure 1, our analysis demonstrates that linkages between our key study features have methodological issues, implications, and outcomes related to recruitment and retention, operationalization, the research team, data characteristics, researcher roles and relationships, and confidentiality. Below, we further explore our methodological journey by examining those we identified and pointing out how they relate to features of our study. We discuss advantages and challenges inherent in our study features and our strategies for maximizing and addressing them, respectively. Where appropriate, we offer recommendations and outline changes to Wave 2.

Recruitment and Retention

The research context, focus, scope, duration, and design complexity presented potential challenges to recruiting facilities and individuals willing participate over 2 years. Access to homes was facilitated by our team’s respected reputation and positive connections in the assisted living community and providers’ willingness to showcase their communities. We had pledges of support from administrators of three of the four sites dating back to the proposal-writing phase, 2 years before data collection began. In the interim, our corporately owned home changed ownership and executive directors. Although common in the assisted living corporate world (Khatutsky et al., 2016), the change limited facility assistance with participant recruitment and delayed access to facility records.

The frequency, duration, and sensitive nature of data collection, paired with the tenuous health of the study population, impeded resident recruitment. Ten declined to participate; others were reluctant to talk on the record, were too frail, or believed that participating would be burdensome. One resident agreed and then unexpectedly passed away; chronic pain and frequent hospitalizations prevented formally interviewing another.

Recruitment of different types of convoy members across assisted living settings presented further challenges. Informal caregivers had multiple competing demands, anticipated from existing long-term care research (Kemp, 2008; Morrisey, 2012), and formal caregivers had similarly stressful lives. Our 2-year time frame meant recruitment was ongoing and allowed us to enroll new members as they joined convoys throughout data collection. For example, grandchildren returned from school, out of town family members visited, and health care workers were mobilized. Interviews frequently were scheduled and rescheduled. We were patient, persistent, and adaptive in our research strategies. Conducting phone interviews was a common strategy, particularly for out-of-state caregivers. We also interviewed convoy members in homes, offices, and other locations of their choosing.

Recruitment occasionally was unsuccessful. Consequently, some convoys had more members who participated and richer data than others. Nevertheless, our complex research design and extended time frame, while creating certain challenges, facilitated enrolling initially unavailable individuals and allowed us to access a broader range of stakeholders.

Retention was an ongoing concern, primarily related to resident frailty and caregivers’ personal and work life. As anticipated, focal residents experienced frequent transitions, including health crises and decline, often prompting temporary or permanent changes to care and living arrangements, and health improvements, leading to increased self-care and a reduction of convoy member involvement. Capturing how convoys and care processes adapted to such situations were key areas of inquiry in our study and created challenging research issues, while adding to the richness of the data.

Residents had good and bad days; follow-ups depended on availability, ability, and consent/assent on a given day. Persistence and flexibility on the part of researchers were key strategies. Obtaining direct follow-up data proved especially challenging for residents with progressive cognitive decline. Although our consultant with expertise in working with individuals who have cognitive impairment provided upfront training on optimal communication strategies, we sought guidance from him on specific cases throughout data collection. When changes in cognitive function advanced to the point that some residents could no longer provide detailed data (e.g., on health changes), the research team gathered much of these data from convoy members.

During Wave 1, three focal residents died, two were discharged, and two relocated to other communities. Many had temporary care transitions: 20 were hospitalized, 12 multiple times; four went to a rehabilitation facility; 20 received home care services, including skilled nursing, physical, occupational, and speech therapies; and five received hospice care. These transitions impeded follow-up but provided access to external care providers, who joined residents’ convoys, usually on a short-term basis. When appropriate, we visited focal residents in hospitals and rehabilitation facilities, observed therapeutic care activities, and attended memorial services, allowing observation of how transitions were negotiated, coordinated, and managed within convoys. We were able to formally interview 21 of these external care workers.

Changes in convoy members’ lives affected follow-up data collection and retention. Informal caregivers navigated their own health problems, managed additional care responsibilities, experienced relationship, education, and job changes, went on vacation, and relocated; staff retired, quit, or were terminated. Our extended time frame, though, allowed us to understand the effects of transitions on care and on the structure and function of resident care convoys. At one home, the rapid turnover of multiple long-term staff led to the use of an agency to supply staff as needed, which changed residents’ convoy composition and required them to adjust to caregivers unfamiliar with their needs and preferences.

Operationalization

The operationalization of key concepts was shaped in some cases by multiple study features. For example, although “convoy members” are defined in the “convoys of care” model (Kemp et al., 2013), we sometimes grappled with who in fact belonged in a convoy. Initially, we asked focal residents (or proxies) during formal interviews about the makeup of their informal and formal support networks. However, by using multiple sources and modes of data collection to discover the structure and function of convoys and understand their ebb and flow, we learned about convoy members who often are invisible or misunderstood in more static or cross-sectional research. In certain convoys, we identified “shadow” contributors who provided support, but had not been named or acknowledged by the resident. One resident, for example, identified his son and assisted living staff as sources of support, yet about his daughter-in-law said, “I don’t depend on her for anything.” Over time, we learned that she shopped weekly for his favorite foods, visited regularly, and previously had provided hands-on care, data which confirmed convoy member status.

In other convoys, residents identified caregivers who provided little, if any support as convoy members. We conceptualize these individuals as “honorary” convoy members. They were important to residents and, normatively speaking, might be counted on for support, yet current relationships were estranged or strained and typically incurred emotional or financial costs. Our design allows us to identify, observe, and analyze the full range of relationships and changes over time, as well as to understand residents’ support of others. It also allows us to identify and explore emerging concepts such as “shadow” and “honorary” convoy members that will inform theoretical sampling (Corbin & Strauss, 2015) and help advance theoretical and empirical insights.

Research Team

Our scope and design necessitate a large research team composed of smaller teams assigned to each research site. The team included five investigators, one project manager, one research associate, 10 graduate research assistants, and one consultant. Four investigators, all highly seasoned qualitative researchers familiar with assisted living environments, served as team leads. Our age-, gender-, background-, and research experience-diverse team proved beneficial by allowing for triangulation and a range of perspectives and relationships. For instance, less-experienced researchers offered a fresh perspective, and the balance of younger and older researchers provided important generational exchanges. Differences in race and age between researchers and research participants also proved beneficial. For instance, an older African American participant delighted in “teaching” younger White researchers about African American culture. Non-Jewish researchers interviewing Jewish participants had similar experiences.

Investigators were committed to providing graduate students field researcher experience, a high-risk and high-reward endeavor, particularly given the study’s duration. During Wave 1, five students left the project; one graduated, and four left unexpectedly for personal reasons, placing extra demand on researchers in the affected homes. Hiring new researchers required time to accommodate Institutional Review Board amendments, training, and integration into the team and setting. In two cases, researchers transitioned between homes to ensure adequate coverage. One student who changed homes felt she did not have the “same rapport” or grasp of residents’ “in-depth histories” as she would have by staying in one site. Personnel changes puzzled participants and required explanation. Yet, stable team leadership and a core group of researchers helped preserve consistency and researcher turnover and movement between homes also had positive aspects. New researchers developed “new” relationships, had alternative perspectives, and ultimately have enhanced data quality and, in some cases, facilitated access to participants we previously had difficulty recruiting. While not always possible to predict researcher turnover, we recommend having back up plans in place and if resources allow, a research team that is large and skilled enough to absorb unexpected change.

Data Management, Quality, Depth, and Consistency

The overall scope and design, the duration and breadth of data collection, with a myriad of touch points for focal residents and convoy members across sites, resulted in volumes of data that yielded in-depth information about care relationships, experiences, and processes but also created challenges for data management and information tracking. As Laditka and colleagues (2009) describe, large qualitative projects are time-intensive, demand skillful project management, including the development of clear procedures and protocols, data management tools, and effective communication strategies. Our research team met twice monthly to discuss data collection progress and any problems encountered, including accessing participants, managing relationships, and maintaining adequate coverage. Team members also regularly communicated via phone, email, and text (without participant identifiers), allowing us to quickly address situations in the field. Team leads helped coordinate field visits, interviews, and follow-up communications for each site. The principal investigator, also a team lead, regularly communicated with the other leads and the consultant. The project manager helped to oversee consistency in data collection and management activities across the sites.

During Wave 1, we used multiple data management/analysis programs: (a) SPSS21 to store and manage all participants’ demographic information, focal residents’ health and functional status, and convoy network properties; (b) Microsoft Access to track resident health and convoy changes, participant contact points, and convoy structure and function over time; and (c) NVivo10 to store, manage, and code qualitative data. Our Access database proved cumbersome and a far more powerful database than our data tracking required. During Wave 2, we replaced this database with a more accessible and streamlined, Microsoft Excel database. This database is populated from the data researchers provide about health and convoy transitions in each focal resident’s profile. Researchers are writing focal resident profiles prospectively rather than retrospectively going through the data, a practice which was arduous near the end of Wave 1.

Developing, applying, comparing, and refining a set of “housekeeping” codes (i.e., broad categories of codes organized around our study aims) for our NVivo database took multiple iterations, delaying coding progress. Keeping pace with simultaneously collecting and coding data was challenging. A planned break between waves provided a catch-up opportunity and an opportunity to code Wave 2 data as it is collected.

The study is notable for attempting to obtain a complete picture of residents’ convoys. The inclusion of all stakeholders followed over time allows us to advance knowledge by providing a more complete and complex understanding of care networks than previously existed. However, the nature, depth, and volume of data demand rigorous qualitative analysis, which is time- and labor-intensive. It will be challenging to convey the complexity of our findings within the constrained space of the journal article format (see Morse, 2016).

Our approach also presents challenges to getting the story right. As most qualitative researchers do, we acknowledge the fantasy of absolute truth and anticipated inconsistencies in participant accounts (Patton, 2015). Sometimes, focal residents and convoy members provided inconsistent or incomplete accounts either within their individual narratives or as a collective. Some had different interpretation of events over time or relative to others or concealed or omitted details, possibly to protect their own or others’ identity or because they perceived the details as unimportant. In a few instances, we noted contradictions between participant accounts and facility records regarding focal residents’ health status and clinical diagnoses, particularly surrounding cognitive status (see also Zimmerman, Sloane, & Reed, 2014). One resident, for example, had a diagnosis of dementia, which her daughter felt was inaccurate; researchers observed no evidence of cognitive impairment. This resident had experienced an emotional crisis when her husband died only weeks after they moved to the home, the likely cause of the temporary cognitive loss and the misdiagnosis. Our in-depth and multipronged qualitative approached allowed us to capture and analyze “multiple truths” (see Thomas, 1923) such as these, which are valuable data that must be acknowledged and accounted for analytically to address our study aims and make recommendations to researchers, practitioners and policy makers for developing and supporting collaborative care partnerships.

Studying diverse settings, each with unique culture and organizational structure, also has implications for data quality and consistency. How researchers fit in and were given access within settings differed, which affected the volume and quality of data and demonstrates how facility factors influence the research process. For instance, corporate approval was necessary only at one site. Here, researchers had to coordinate visits with management, and, despite resident consent, administration delayed access to their records until the final months of data collection. Researchers expressed greater difficulty forming relationships with family and staff and described the environment as “very formal” compared with the other sites, where, once permission and informed consent were established, researchers had unrestricted access to the home, residents, and focal resident records and developed a range of relationships, including close connections. Although verbally discussed and worked out in advance, we recommend a formalized document that outlines expectations and timelines for data collection activities, particularly those that are reliant on facility access, such as record review, and is agreed upon by the researchers and facility representatives.

Researcher Roles and Relationships

Building rapport with participants is basic to good qualitative research (Patton, 2015), but alongside the frequency, duration, nature, and focus of our data collection, was a process that rendered the development and management of research-participant relationships a key methodological issue. A related issue pertained to negotiating researcher roles. We had a number of strategies for establishing early on our roles as researchers. All homes posted and circulated flyers with researcher photos and a brief project description. Researchers wore name tags and consistently identified as university researchers. Nonetheless, our roles sometimes were misunderstood; participants assigned us alternate identities. In one setting, for example, researchers frequently were perceived and introduced as volunteers despite ongoing reminders and corrections. Once when a researcher was observing a speech therapy session, the resident referred to researchers as “wonderful volunteers,” even after listening to the researcher describe the project and her role to the therapist. We continue to view such pronouncements as additional opportunities to clarify our roles.

Four researchers had preexisting relationships with care staff and administrators from previous research and aging network connections. Many close researcher–participant relationships were forged. These connections reflect successful rapport- and trust-building and promoted richer data, easier access, and more open communication about significant events, such as focal resident health crises and deaths.

Although unintentional, our presence altered the settings and affected participants’ lives, mostly through relationship-building over time with focal residents and their convoys. Most field researchers became convoy members and sources of support for residents and some family and staff. As documented in assisted living studies of a similar nature (Ball et al., 2005, pp. 13–14), throughout data collection, researchers helped with activities, attended outings, celebrated special events, and provided assistance, such as pushing wheelchairs, helping with technology, retrieving items, moving furniture, and sharing information, books, and photos. Focal residents’ family members routinely thanked us for visiting and spending time with their relative, including a daughter who concluded an email saying, “Thanks again for the friendship you have shown Dad.”

Occasionally, our presence was viewed with ambivalence. A 55-year-old focal resident who resisted developing relationships with the “old people” surrounding him, depended on visits from family and friends for his quality of life and sometimes tried to restrict researcher contact with them, despite incorporating researchers into his own convoy. Obliging him, the researcher interviewed his out-of-town sister by phone after she returned home, rather than during her short visit, and researchers stayed away during a cousin’s twice-monthly visits. Thus, identifying and respecting boundaries became an important requirement of the researcher role and is recommended.

On balance, participants reported positive research experiences. Some found discussions useful, even “cathartic,” including a daughter who ended a follow-up call saying, “Thank-you. I feel like I’ve found a good friend. I always feel better after I talk to you.” The son of a resident with dementia emailed:

I really appreciate your periodic check-ins. Even with my sisters, aunts, and my wife to talk to, this is a very lonesome experience. It’s easy to feel like I’m by myself. I get trapped in my head with my thoughts often enough. It’s such a complicated thing to deal with, emotionally speaking.

Participants commonly viewed us as friends, confidantes, and supporters, again leading to a blurring of our researcher roles. Important ethical issues can arise from a participant misunderstanding the researcher role. Throughout the data collection and analysis processes and following Hewitt’s (2007) conceptualization of an ethical researcher relationship, we sought to acknowledge our biases, maximized rigor, rapport, and respect for participant autonomy, maintained confidentiality, and avoided exploitation.

Participating in research can be disruptive and upsetting, particularly when it involves sensitive topics (Patton, 2015). Institutional review boards and researchers quite rightly focus on evaluating and minimizing participant risk; our consent form identifies emotional upset as a potential risk. Several Wave 1 participants became emotional during interviews. A highly distressed family member struggling to manage caregiving and other aspects of family life accepted a referral list for possible support. Certain participants perceived us as counselors, “therapists,” or care experts. We renegotiated these identities by reinforcing our roles as researchers and by identifying alternative resources. For instance, when a daughter asked a researcher how to manage the holidays without upsetting her mother who had cognitive impairment, the researcher identified resources from the Alzheimer’s Association and relayed advice from our team member with expertise in dementia care. It is essential that researchers anticipate and prepare to address such scenarios in a meaningful way.

Qualitative research on sensitive topics can involve emotional labor and vulnerability for researchers (Dickson-Swift, James, Kippen, & Liamputtong, 2008; emerald & Carpenter, 2015), especially when boundaries are blurred between researcher and friend or therapist (Dickson-Swift, James, Kippen, & Liamputtong, 2006). Anticipating this risk, prior to entering the field investigators provided training and prepared researchers, particularly those new to assisted living environments, about what to expect and how to work with frail adults and the range of stakeholders. Expecting participant decline, relocation, and death, we involved a hospice social worker in our training, and, because of a student’s emotional distress while visiting a frail focal resident, we identified on-campus counseling resources.

In preparation for exiting the field, we began sharing and discussing researcher emotions in team meetings. The principal investigator also encouraged researchers to reflect on and write about experiences in memos, including documenting emotional responses and reflections on fieldwork and analysis. One researcher noted:

I felt like everyone I visited except [one] was in poor health and experiencing declining health and spirits. It made me very sad because I’ve come to know and care about the people that we have been talking to over the last two years.

Researchers also experienced positive, negative, and ambivalent emotions directed at participants, scenarios, and behaviors. As data analysis moves forward, we are keenly aware of the need to examine how researcher biases, including emotional connections between researchers and participants, might enter into our findings. We are using negative case analysis and triangulation of data types, sources, and use of multiple researcher perspectives as strategies to mitigate potential researcher bias.

In hindsight, we could have better equipped researchers to process emotional responses at the outset. Our experience reinforces what others recommend: anticipating, acknowledging, and managing emotional responses in sensitive research (Rager, 2005). Not only, as Gilbert (2001, p. 11) observes, does “awareness and intelligent use of our emotions” benefit “the research process,” but reflexivity is also an effective strategy for emotional processing, promoting self-care, and safeguarding researchers’ emotional well-being (Malacrida, 2007). Fieldwork difficulties of this nature are rarely discussed outside of research teams (Wray, Markovic, & Manderson, 2007), and researcher risk is infrequently or not comprehensively assessed, but should be (Dickson-Swift et al., 2008; emerald & Carpenter, 2015). Debriefing and reflection, accomplished in team meetings, one-on-one discussions, and memoing, became important strategies and are recommended by others (Wray et al., 2007). These techniques sometimes introduced tensions but ultimately strengthened team relationships and cohesion.

Although potentially difficult and as important as the entering process, historically, exiting the field has received infrequent attention (Shaffir, Stebbins, & Turowetz, 1980a). Our close relationships and integration in some sites made leaving somewhat daunting. Concern, though expressed early on, became more intense toward the end. For example, with 4 months of data collection remaining, “Dolly,” a focal resident told a researcher: “Truly one of the best parts of me living here is getting to know y’all.” The researcher reflected, “Dolly’s sentiments were touching and reminded me of how personal this study is and how much we have become involved in their lives … It is going to be difficult to leave.”

We developed group strategies for exiting. For instance, with 6 months remaining in the field, researchers began reminding participants that the end of the study was nearing. Yet, as Shaffir, Stebbins, and Turowetz (1980b, p. 273) note, “the problems, concerns, and ease of field exiting” vary across setting. We thus tailored ways to mark our departure to each site. In three homes, teams worked with staff to develop and host a social event to thank everyone and officially commemorate departure. At the smallest site, a community event seemed inappropriate. Instead, the team lead met with the owners and staff to share preliminary findings, which was disseminated to all participants in a final report. These events and activities advertised our leave-taking and provided a platform to publicly express appreciation and say farewell.

Leaving is shaped by the relationships and identities researchers negotiate in the field (Shaffir et al., 1980b). In our study, to a degree, relationships and identities varied by researcher and participant. Consequently, researchers also negotiated the parameters of leaving the field individually, including whether or not to maintain contact. Those who continue contact are renegotiating their relationships as nonresearchers. In the majority of instances, however, most relationships did not continue. Researchers minimized expectations of continued contact by thanking participants, publicly and privately, verbally and by writing personalized thank-you notes, and by explaining that another study wave involving new settings and participants was on the horizon.

Confidentiality

Our study protocols, procedures, and systems were designed to protect participants’ identity and information. Facilities and participants were assigned numeric codes, which appear on paper files stored in locked file cabinets within a locked office within a locked suite. We store electronic data on a secure, remote, password-protected server within a folder accessible only to active team members, a solution which meets requirements for secure storage, including data protected under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Opportunities for confidentiality breeches increase when research involves networks of connected individuals (Damianakis & Woodford, 2012). Our emphasis on gaining knowledge from entire networks across time created numerous scenarios where confidentiality issues arose. In each home, administrators and staff helped us access residents and families and select focal residents and, subsequently, provided access and answered questions about resident records. Most thus knew the identity of focal residents and, by extension, potential convoy member participants. We could not prevent participants from identifying themselves to others as study participants, but researchers protected convoy member participant identity within families and among staff and care workers.

Maintaining confidentiality with multiple informants over time required constant vigilance. Forbat and Henderson’s (2003) report being “stuck in the middle” when interviewing caregiver-care recipient spousal dyads. Similarly, participants often asked us who we had spoken to and when, as well as what others said on a given topic. We often were caught in large webs of relationships, including those among residents, family members and friends, volunteers, and multiple care workers. Frequent and prolonged contact and our effort to enroll as many convoy members as possible meant numerous opportunities for confidentiality breeches. One researcher described this challenge:

On numerous occasions during this visit and in the past, I was asked for information that, if I’d given, would have breached participant confidentiality or violated ethical rules. The executive director asked me what a focal resident told me about her rent increase; one focal resident asked me about another’s health condition and her daughter asked me where another focal resident was receiving rehab; and the manager asked me about my “take on” a focal resident’s daughter.

Precarious confidentiality situations happened routinely across Wave 1 sites and increased with time. From the participant perspective, asking questions about others was acceptable. Most knew we had information, saw us as accessible and friendly individuals, taking for granted our ability to share. We characterized certain lines of questioning as “ethical landmines,” and discussed them regularly as a team. We redefined landmine questions by seeing them as opportunities to remind participants and others in the setting about our researcher roles and expectations of confidentiality. We endorse this as an effective strategy that neither breached confidentiality nor damaged rapport.

The use of in-depth cases at the facility and convoy levels presents further dilemmas. Consistent with our past research (e.g., Ball et al., 2010, 2014; Kemp et al., 2015), we used pseudonyms for participants and facilities. Yet, the difficulty of protecting identity and confidentiality increases when multiple informants are interviewed in a relationship or network (Damianakis & Woodford, 2012). Forbat and Henderson (2003) recommend “a careful and critical fictionalizing of accounts” (p. 1459). Connidis (2007), for instance, changed names and certain facts in her analysis of sibling networks. We currently are considering “the ethics of what to tell” (Ellis, 2007, p. 24), including what details to omit or change about homes, networks, and individuals. As we enter the dissemination phase, our challenge is maintaining confidentiality without compromising explanatory value.

Conclusion

In this article, we have drawn the curtain to reveal our study’s “backstage” (Goffman, 1959, p. 112) by discussing our methodological journey, good, bad, and otherwise. To a certain extent, this unconventional behavior is risky; it exposes us to the possibility of criticism and praise. Yet, we believe transparency is essential to cumulative knowledge building and can enhance, advance, and strengthen existing research practices and decision making, including how best to carry out research and minimize participant and researcher risk. We hope by sharing the benefits and challenges from our study’s first wave, researchers can learn from our experiences, adapt what works and anticipate and avoid potential pitfalls. We also hope others appreciate the value of our approach and how it expands understanding of care networks beyond existing quantitative or small-scale qualitative studies.

Our experience highlights the dynamism of the research process, particularly when it involves prolonged and in-depth qualitative data collection, and the need for researchers to be aware of and attentive to what transpires as research develops, including contradictions and tensions in the data, ethical considerations, and anticipated and unanticipated researcher intervention in the setting and participants’ lives, and the development of project management protocols. As Janesick (1994) notes, “the dance of qualitative research design” is shaped by ongoing unpredictability and decision making in the field; researchers need to continually assess, refine, and adjust to what they learn and encounter (p. 213). Clear and ongoing communication and the development of effective data management tools and systems are vital to accomplishing research goals. We believe that the credibility of qualitative research is predicated on the credibility of the researchers and use of rigorous data collection and analytic strategies, both of which require planning and are labor- and time-intensive.

Our experiences underscore that entering and exiting the field are important dimensions of the research process; both should be treated in a strategic and thoughtful manner (Shaffir et al., 1980a) and where appropriate, involve collaboration among researchers and with participants to develop the most suitable strategies. Relationships are central to all aspects the research process, including recruitment, retention, and data collection. Researcher roles and relationships often become more complex, even blurry, when the research topic is of a personal and sensitive nature, the focus is on entire networks of connected individuals, and when participant-researcher contact is regular, frequent, and prolonged. It is necessary to acknowledge, plan for, and protect participants and researchers alike (Patton, 2015). Along the way, including in the dissemination stage, key decisions must be made about confidentiality, including what can and should be told and in what venue.

Ultimately, our experiences speak to the value of sharing and reflecting on methodological experiences and decision making. Reflecting on the research process is essential as it helps researchers “look to the future through the practice of anticipation” (Hewitt, 2007, p. 1156). Although written decades ago, Snow’s (1980) commentary on social research methods still rings true:

If ethnographers as well as survey researchers and experimentalists would devote more time and energy to providing explicit accounts of their total research experience and the factors that affect it, then perhaps we could begin to round out and demystify our understanding of the entire research process. (p. 119)

Making our methodological backstage public is our contribution to demystifying qualitative research, particularly as it pertains to the study of long-term care, relationships, and care networks in depth and across time. We encourage others to reflect on their methodological experiences and consider reporting aspects that could strengthen others’ work and help advance the state of scientific methods and knowledge in health research and beyond.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all those who gave so generously of their time and participated in the study. We also are grateful to Carole Hollingsworth and Russell Spornberger for their hard work and dedication to the study. Thank you to Victor Marshall and Frank Whittington for their unwavering support, encouragement, and inspiration.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG044368 (to C.LK.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Candace L. Kemp, PhD, is an associate professor in The Gerontology Institute and Department of Sociology at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Mary M. Ball, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Division of General and Geriatric Medicine in the Department of Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Jennifer Craft Morgan, PhD, is an assistant professor in The Gerontology Institute at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Patrick J. Doyle, PhD, is the corporate director of Alzheimer/Dementia Services for Brightview Senior Living, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Elisabeth O. Burgess, PhD, is an associate professor in The Gerontology Institute and Department of Sociology at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. She is the director of the Gerontology Insitute.

Joy A. Dillard, MA, is project manager for the Convoys of Care study at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Christina E. Barmon, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at Central Connecticut State University in New Britain, Connecticut, USA.

Andrea F. Fitzroy, MA, is a graduate research assistant in The Gerontology Institute and a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Victoria E. Helmly, BA, is a graduate research assistant in The Gerontology Institute and a Master of Social Work student at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Elizabeth S. Avent, BA, is a graduate research assistant and master of arts student in The Gerontology Institute at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Molly M. Perkins, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Division of General and Geriatric Medicine in the Department of Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and Atlanta Site Director for Research for the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC), Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Footnotes

We presented portions of this article at the Southern Gerontological Society meetings in Williamsburg, Virginia, USA in April 2015.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The Table 1 and 2 are available for this article online.

References

- Ball MM, Kemp CL, Hollingsworth C, Perkins MM. “This is our last stop”: Negotiating end-of-life transitions in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2014;30:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Independence in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2004;18:467–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2004.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Patterson V, Hollingsworth C, King S, Combs BL. Quality of life in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2000;19:304–325. doi: 10.1177/073346480001900304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black BS, Rabins PV, Sugarman J, Karlawish JH. Seeking assent and respecting dissent in dementia research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18:77–85. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bd1de2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NH: Prentice Hall; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Moss A, Rosenoff E, Harris-Kojetin L. Residents living in residential care facilities: United States, 2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. (NCHS Data Brief No. 91) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder P, O’Keeffe J, O’Keeffe C. Compendium of residential care and assisted living regulation and policy: 2015 edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier N, Grenier A. Successful linkage between formal and informal care systems: The mobilization of outside help by caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22:1330–1344. doi: 10.1177/1049732312451870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA. Negotiating inequality among adult siblings: Two case studies. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:482–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00378.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Damianakis T, Woodford MR. Qualitative research with small connected communities: Generating new knowledge while upholding research ethics. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22:708–718. doi: 10.1177/1049732311431444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson-Swift V, James EL, Kippen S, Liamputtong P. Blurring boundaries in qualitative health research on sensitive topics. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:853–871. doi: 10.1177/1049732306287526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson-Swift V, James EL, Kippen S, Liamputtong P. Risk to researchers in qualitative research on sensitive topics: Issues and strategies. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:133–144. doi: 10.1177/1049732307309007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill JS, Morgan JC, Kalleberg AL. Making “bad jobs” better: The case of frontline healthcare workers. In: Warhurst C, Findlay P, Tilly C, Carre F, editors. Are bad jobs inevitable? Trends, determinants and responses to job quality in the twenty-first century. New York: Palgrave; 2012. pp. 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Carder PC, Morgan LA, Frankowski AC, Roth EG. Assisted living: The search for home. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt KM. Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review. 1989;14:532–550. doi: 10.2307/258557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C. Telling secrets, revealing lives: Relational ethics in research with intimate others. Qualitative Inquiry. 2007;13:3–29. doi: 10.1177/1077800406294947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- emerald E, Carpenter L. Vulnerability and emotions in research: Risks, dilemmas, and doubts. Qualitative Inquiry. 2015;21:741–750. doi: 10.1177/1077800414566688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forbat L, Henderson J. “Stuck in the middle with you”: The ethics and process of qualitative research with two people in an intimate relationship. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:1453–1462. doi: 10.1177/1049732303255836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. Family involvement in residential longterm care: A synthesis and critical review. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9:105–118. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331310245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert K. Introduction: Why are we interested in emotions? In: Gilbert KR, editor. The emotional nature of qualitative research. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2001. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Anchor Books; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt J. Ethical components of researcher researched relationships in qualitative interviewing. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:1149–1159. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janesick VJ. The dance of qualitative research design: Metaphor, methodolatry, and meaning. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 209–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL, Antonucci TC. Convoys over the life course: A life course approach. In: Baltes PB, Brim O, editors. Life span development and behavior. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 253–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey SG, Laditka SB, Laditka JN. Dementia and transitioning from assisted living to memory care units: Perspectives of administrators in three facility types. The Gerontologist. 2010;50:192–203. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Negotiating transitions in later life: Married couples in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2008;27:231–251. doi: 10.1177/0733464807311656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Married couples in assisted living: Adult children’s experiences providing support. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:239–261. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11416447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Perkins MM. Convoys of care: Theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. Journal of Aging Studies. 2013;27:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Perkins MM. Couples’ social careers in assisted living: Reconciling individual and shared situations. The Gerontologist. 2015 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv025. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatutsky G, Ormond C, Wiener JM, Greene AM, Johnson R, Jessup EA, Harris-Kojetin L. Residential care communities and their residents in 2010: A national portrait. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. (DHHS Publication No. 2016-1041) [Google Scholar]

- Laditka SB, Corwin SJ, Laditka JN, Liu R, Friedman DB, Mathews AE, Wilcox S. Methods and management of the healthy brain study: A large multisite qualitative research project. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(Suppl. 1):S18–S22. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malacrida C. Reflexive journaling on emotional research topics: Ethical issues for team researchers. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:1329–1339. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan LA, Rubinstein RL, Frankowski AC, Perez R, Roth EG, Peeples AD, Goldman S. The facade of stability in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2014;69:431–441. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey B. Ethics and research among persons with disabilities in long-term care. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22:1284–1297. doi: 10.1177/1049732312449389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. Underlying ethnography. Qualitative Health Research. 2016;26:875–876. doi: 10.1177/1049732316645320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Research involving individuals with questionable capacity to consent: Points to consider. 2009 Retrieved from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/questionablecapacity.htm.

- Palmer BW, Dunn LB, Appelbaum PS, Mudaliar S, Thal L, Henry R, Jeste DV. Assessment of capacity to consent to research among older persons with schizophrenia, Alzheimer disease, or diabetes mellitus: Comparison of a 3-item questionnaire with a comprehensive standardized capacity instrument. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:726–733. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park-Lee E, Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Moss AJ, Rosenoff E, Harris-Kojetin LD. Residential care facilities: A key sector in the spectrum of long-term care providers in the United States. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. (NCHS Data Brief No. 78) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative methods and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C. Relational autonomy in assisted living: A focus on diverse care settings for older adults. Journal of Aging Studies. 2012;26:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rager KB. Compassion stress and the qualitative researcher. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:423–430. doi: 10.1177/1049732304272038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rome V, Harris-Kojetin LD. Variation in residential care community nurse and aide staffing levels: United States, 2014. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2016. (National Health Statistics Report No. 91) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta M, Harris-Kojetin L, Caffrey C. Variation in residential care community resident characteristics, by size of community: United States, 2014. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. (NCHS Data Brief No. 223) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffir WB, Stebbins R, Turowetz . Leaving the field. In: Shaffir WB, Stebbins R, Turowetz A, editors. Fieldwork experiences, Qualitative approaches to social research. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1980a. pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffir WB, Stebbins R, Turowetz . Leaving the field in ethnographic research: Reflections on the entrance-exit hypothesis. In: Shaffir WB, Stebbins R, Turowetz A, editors. Fieldwork experiences, Qualitative approaches to social research. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1980b. pp. 261–281. [Google Scholar]

- Snow DA. The disengagement process: A neglected problem in participant observation research. Qualitative Sociology. 1980;3:100–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00987266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WI. The unadjusted girl. Boston: Little, Brown; 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Griffin C, Marshall VW. Reconceptualizing the relationship between “public” and “private” eldercare. Journal of Aging Studies. 2003;17:189–208. doi: 10.1016/S0890-4065(03)00004-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wray N, Markovic M, Manderson L. “Researcher saturation”: The impact of data triangulation and intensive-research practices on the researcher and qualitative research process. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:1392–1402. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin KR. Case study research: Design and methods. 5. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Reed D. Dementia prevalence and care in assisted living. Health Affairs. 2014;33:658–666. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.