Abstract

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK or PCK) catalyzes the first rate-limiting step in hepatic gluconeogenesis pathway to maintain blood glucose levels. Mammalian cells express two PCK genes, encoding for a cytoplasmic (PCPEK-C or PCK1) and a mitochondrial (PEPCK-M or PCK2) isoforms, respectively. Increased expressions of both PCK genes are found in cancer of several organs, including colon, lung and skin, and linked to increased anabolic metabolism and cell proliferation. Here, we report that the expressions of both PCK1 and PCK2 genes are downregulated in primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and low PCK expression was associated with poor prognosis in patients with HCC. Forced expression of either PCK1 or PCK2 in liver cancer cell lines results in severe apoptosis under the condition of glucose deprivation and suppressed liver tumorigenesis in mice. Mechanistically, we show that the proapoptotic effect of PCK1 requires its catalytic activity. We demonstrate that forced PCK1 expression in glucose-starved liver cancer cells induced TCA cataplerosis, leading to energy crisis and oxidative stress. Replenishing TCA intermediate α-ketoglutarate or inhibition of reactive oxygen species production blocked the cell death caused by PCK expression. Taken together, our data reveal that PCK1 is detrimental to malignant hepatocytes and suggest activating PCK1 expression as a potential treatment strategy for patients with HCC.

Keywords: Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, gluconeogenesis, apoptosis, liver cancer

INTRODUCTION

Altered cellular metabolism is a common feature of many different types of cancers.1, 2 One notable metabolic alteration in tumors cells is elevated aerobic glycolysis, commonly referred to as the Warburg effect,3 which supports tumor growth in part by accumulating glycolytic intermediates for anabolic biosynthesis. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a primary malignancy of the liver and the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide. A major function of the liver is to provide fuel, in the form of glucose, to other organs in the human body through either degradation of glycogen (glycogenolysis) or synthesis of glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors such as amino acids and glycerol (gluconeogenesis). While much attention has been paid to glycolytic regulation during tumorigenesis, emerging evidence is linking altered expression of gluconeogenic enzymes with tumorigenesis; in particular, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK or PEPCK) genes. Mammalian cells express two PCK genes which encode a cytoplasmic (PCK1) and a mitochondrial (PCK2) isozymes, respectively, and catalyze the same reaction of converting oxaloacetate (OAA) to phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP).4–6 PCK1 catalyzes the first rate-limiting reaction of gluconeogenesis in the cytoplasm. The physiological function of PCK2 in mitochondria, which lacks other enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis, is not well understood at present. Elevated expression of PCK1 is found in colon cancer and is linked to increased glucose and glutamine utilization, supporting anabolic pathway and cell proliferation.7 Similarly, increased expression of PCK2 gene was found in bladder, breast, and kidney and non-small cell lung cancers and plays a critical function of supporting the growth of glucose-deprived cancer cells in vitro.8, 9 These findings suggest an oncogenic function of PCK genes during the development of tumor in these organs.

Although gluconeogenic enzymes and gluconeogenesis reactions are localized in the cytosol, the substrate of PCK1 and PCK2, oxaloacetate (OAA), is produced mainly in mitochondria by either pyruvate carboxylase (PC) or TCA enzyme malate dehydrogenase (MDH). The conversion of OAA to PEP catalyzed by PCK1 is closely linked to the TCA flux which is reciprocally modulated by the processes of replenishing (anaplerosis) and removal (cataplerosis) of TCA intermediates.10–12 Although present as a minor activity in other tissues, anaplerosis and cataplerosis are highly active in liver cells and their balance is critical for the functioning of TCA cycle.12 In fact, flux through anaplerosis and cataplerosis is greater than the oxidation of acetyl-CoA in the TCA cycle in liver.10 One major reaction of cataplerosis is the transport of OAA from the mitochondria and decarboxylation to PEP by PCK1 or PCK2, which removes intermediates from the TCA cycle.11–13 In addition to gluconeogenesis, cataplerotic enzyme PCK, via producing PEP, also play a major role in feeding two other biosynthetic pathways, glyceroneogenesis and serine and other amino acid synthesis.5 A function of PCK2 in promoting the production of glycolytic/gluconeogenic intermediates has been to be important for the growth in NSCLC.8, 9 The regulation of gluconeogenesis and cataplerosis, and by extension, the function of PCK genes, in liver and kidney are distinctively different from other organs as they are the only two organs in the human body that express all genes required for a functional gluconeogenic pathway. In the present study, we demonstrate that in contrast to the elevated expression and benefit of PCK1 or PCK2 in other types of cancer,7, 8 the expressions of both PCK1 and PCK2 genes are downregulated in HCC. We demonstrate that forced PCK expression in glucose-starved liver cancer cells induced high ROS level as well as energy crisis, leading to cell apoptosis under low glucose condition. Further, we reveal cataplerosis induced by PCK1 as the major mechanism of liver cancer cell death and demonstrate that forced PCK1 expression efficiently suppresses liver tumor growth in a primary mouse HCC model.

Results

Downregulation of PCK1 and PCK2 are simultaneously in HCC

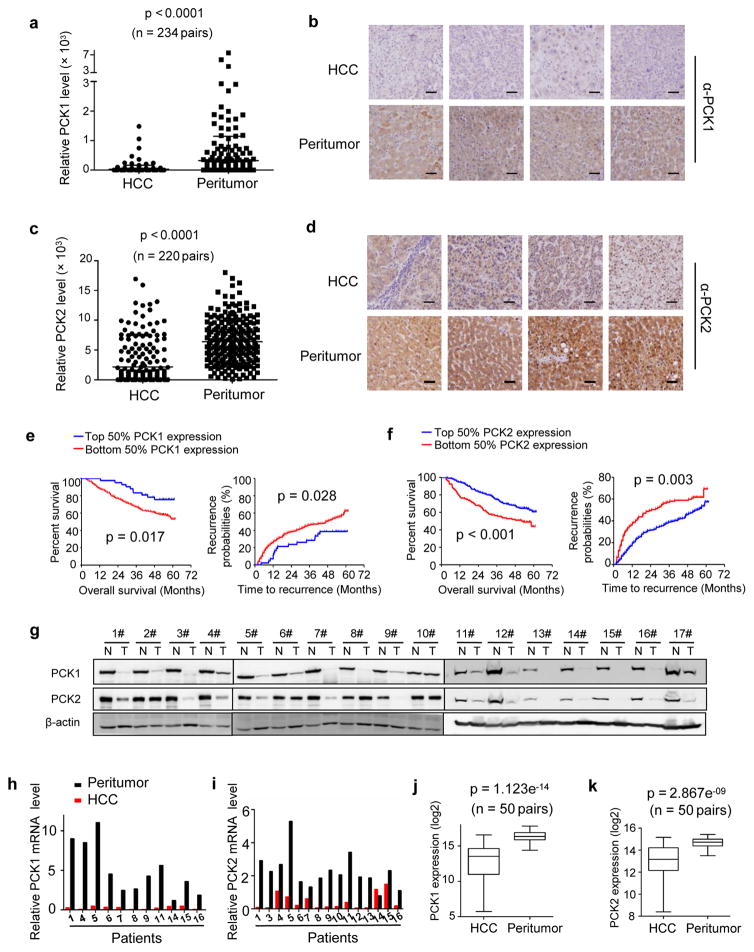

To examine the expression and clinical relevance of PCK1 and PCK2 in HCC, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining on a tissue microarray composed of more than 220 human primary liver tumors and paired normal liver tissues (Fig. 1a–d). Strikingly, and in contrast with previously reported upregulation of both genes in other cancer types, we found that the expression of both PCK1 and PCK2 significantly (p < 0.0001 for both genes) decreased in human liver tumors when compared with normal, adjacent liver tissues. Furthermore, lower expression of either PCK1 or PCK2 was significantly associated with lower overall survival rate and higher tendency of recurrence of HCC patients (Fig. 1e, f). Direct Western blotting analysis of additional 17 primary human liver tumors and normal, adjacent liver tissues confirmed the dramatic downregulation of both PCK1 and PCK2 in HCC when compared to the normal, adjacent liver tissues (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. S1a). To determine if PCK1 and PCK2 are downregulated at the level of transcription, we measured the mRNA levels of PCK1 and PCK2 from another 16 independent HCC patients. This experiment showed that mRNA levels of both PCK genes were significantly decreased in HCC compared to normal, adjacent liver tissues (Fig. 1h, i and Supplementary Fig. S1b, c). These results are further supported by the interrogation of the RNA-seq data from 50 pairs of human liver tumors available from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) liver hepatocellular carcinoma project (Fig. 1j, k). Together, these results demonstrate that unlike other types of cancers, both PCK1 and PCK2 are downregulated in liver cancer through, at least in part, a transcriptional mechanism, and that lower PCK expression is associated with poor prognosis.

Figure 1. The expression of PCK1 and PCK2 was significantly decreased in HCC and low PCK expression was associated with poor prognosis in patients with HCC.

(a) Statistical analysis of PCK1 protein levels from 234 pairs of human liver tumors and adjacent normal liver tissues determined by IHC staining. The intensities of PCK1 proteins were quantified using the Motic Images Advanced software. The horizontal bars represent means of PCK1 protein level within each group (***p < 0.001). (b) Representative IHC staining of PCK1 from 4 pairs of patient samples described in (a). Scale bars: 50 μm. (c) Statistical analysis of PCK2 protein levels from 220 pairs of human liver tumors and adjacent normal liver tissues determined by IHC staining. Quantification was described in (a). The horizontal bars represent means of PCK2 protein level within each group (***p < 0.001). (d) Representative IHC staining of PCK2 from 4 pairs of patient samples described in (c). Scale bars: 50 μm. (e) Kaplan-Meier survival curve and probability recurrence curve of the 234 HCC patients separated into two groups by PCK1 protein levels in tumors. High and low PCK1 expressions were quantified by the intensities of PCK1 staining described in (a). (*p < 0.05). (f) Kaplan-Meier survival curve and probability recurrence curve of the 220 HCC patients separated into two groups by PCK2 protein levels in tumors. High and low PCK2 protein levels were quantified by the intensities of PCK2 staining described in (c). (** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (g) The protein levels of PCK1 and PCK2 were downregulated in 17 additional patient liver tumors determined by Western blotting. (h and i) The mRNA level of PCK1 (h) and PCK2 (i) in patient-matched normal liver and tumor tissues was analyzed by RT-PCR. (j and k) Boxplot of normalized PCK1 (j) and PCK2 (k) mRNA levels in 50 pairs of human normal liver and HCC tissues provided by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) project (https://gdc-portal.nci.nih.gov/projects/TCGA-LIHC). Box plots represent the 25th to 75th percentiles with median, and the whiskers represent the maximum and the minimum value. Statistical significance was determined by Wilcoxon rank sum test. p =1.123e−14 for PCK1 and p = 2.867e−09 for PCK2.

PCK1 promotes liver cancer cell death under low glucose

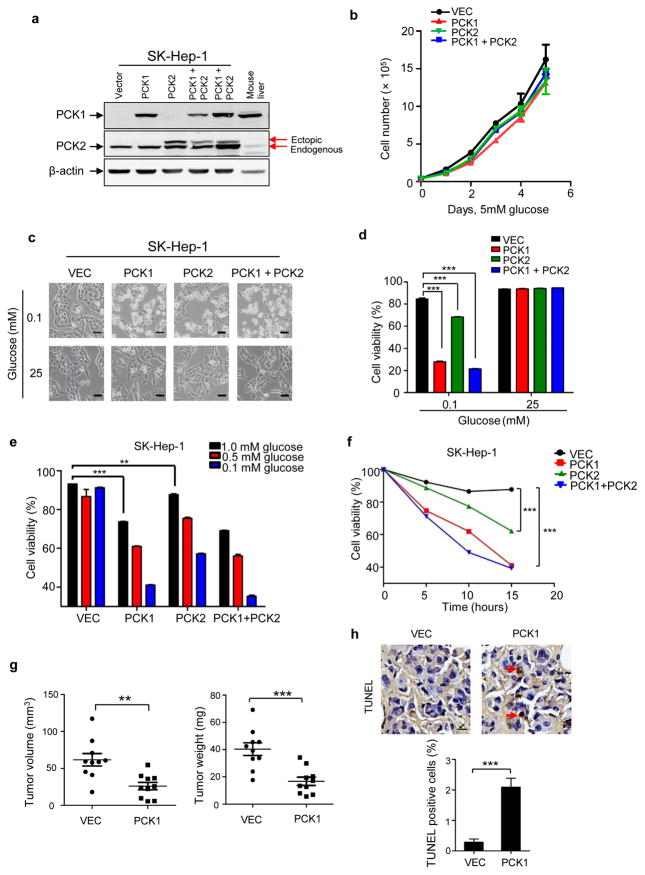

To investigate the functional significance of PCK1 and PCK2 downregulation in HCC progression, we first examined a panel of six liver cancer cell lines for the expression levels of PCK1 and PCK2. While PCK2 is consistently expressed in all six cell lines, PCK1 is expressed in only two cell lines, HepG2 and Hep3B, and is almost undetectable in the other four liver cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Next, we knocked down of PCK1 in HepG2 cells and found that depletion of PCK1 significantly increased cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig. S2b, c). This result suggests a function of PCK1 in suppressing HCC cell proliferation, consistent with a tumor suppressive function in vivo. We then selected SK-Hep-1 cell line for subsequent studies to determine the functional consequence and mechanism of elevated PCK1 expression as it expresses nearly no PCK1 and relatively low PCK2, which mimics the expression pattern in HCC. We generated SK-Hep-1 cells that stably express individual PCK1, PCK2 or both PCKs (Fig. 2a). PCK1 was expressed to a level close to that in mouse normal liver tissue and PCK2 was expressed to a level comparable to the endogenous PCK2. Neither forced expression of PCK1, PCK2 nor combination of both significantly affected cell growth under normal culture condition (Fig. 2b). Considering that glucose concentration is generally lower in tumors than that in normal tissue [e.g.14], we cultured SK-Hep-1 cells stably expressing individual PCK1, PCK2 and both PCKs under low glucose condition (0.1 mM). Surprisingly, enforced expression of PCK1 caused dramatic cell death under low glucose condition compared to control cells (Fig. 2c). Ectopic expression of PCK2 also increased cell death, although to a lesser extent. Co-expression of both PCKs caused most significant death of glucose-starving cells (Fig. 2d). The extent of cell apoptosis inversely correlates with glucose concentration and positively correlates with time course (Fig. 2e, f), further supporting the notion that elevated PCK cause cell death in glucose deprived conditions. Further confirming this result, ectopic expression of PCK1 in another liver cancer cell line, SMMC-7721, also caused severe cell death under low glucose condition (Supplementary Fig. S2d–f). The milder effect of promoting the death in glucose-deprived cells by enforced PCK2 expression than PCK1 expression may be due in part to the fact that PCK2 requires PCK1 to exert its effect on gluconeogenesis.6 We therefore focused on PCK1 in our subsequent studies.

Figure 2. PCK1 promotes liver cancer cell death after glucose starvation.

(a) Establishment of SK-Hep-1 cells that stably express flag-PCK1, flag-PCK2 or both proteins. PCK1 and PCK2 expression levels were detected by specific antibodies. Endogenous PCK1 in SK-Hep-1 cells was not detected due to its low expression level. The upper band in PCK2 blotting indicates the ectopic flag-PCK2. (b) Neither ectopic expression of PCK1 nor PCK2 affected cell proliferation cultured in media containing 5 mM of glucose. Results are mean cell numbers ± SD of triplicate samples. (c) Ectopic expression of PCK1 or PCK2 led to cell death under low glucose condition. SK-Hep-1 cells ectopically expressing indicated PCK gene were cultured in high (25 mM) or low (0.1 mM) glucose conditions for 10 h. Photos were taken under a phase-contrast microscope. Scale bars: 50 μm. (d) Quantification of cell viability in (c) was performed by cell counting after trypan blue staining. Results are mean cell viability ± SD of triplicate samples (***p < 0.001). (e) Apoptosis of SK-Hep-1 cells ectopically expressing indicated PCK gene after cultured under low glucose (0.1, 0.5, 1 mM) condition for 10 h. Cells were stained by propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry. (f) Apoptosis of SK-Hep-1 cells ectopically expressing indicated PCK gene after cultured under 0.1 mM glucose for indicated time. Cell viability was determined by propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V FITC staining. Results are mean cell viability ± SD of triplicate samples (***p < 0.001). (g) Ectopic expression of PCK1 suppressed xenograft tumor growth. SK-Hep-1 cells expressing empty vector or PCK1 were injected subcutaneously into the left and right flanks of 10 nude mice, respectively. At 4 weeks after injection, tumors were collected and measured by weight and volume. Values are mean tumor weight/volume ± SD of ten mice within each group (***p < 0.001). (h) Higher percentages of TUNEL positive cells in PCK1 expressing xenograft tumors indicated a significant cell apoptosis (***p < 0.001). Scale bars: 10 μm. Values are mean percentages of TUNEL positive cells ± SD of six slides within each group.

To investigate PCK1 function in liver cancer progression in vivo, we implanted SK-Hep-1 stable cells harboring empty vector or PCK1 expression into nude mice and determined xenograft tumor growth (Supplementary Fig. S2g). Consistent with its role in promoting cell apoptosis, ectopic expression of PCK1 significantly suppressed xenograft tumor growth (Fig. 2g). Cell apoptosis in the xenograft tumor tissues was determined by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining. Significant more (7 folds) TUNEL positive cells were observed in xenograft tumors derived from PCK1 expressing cells compared to cells expressing control empty vector (Fig. 2h), indicating that PCK1 expression promote apoptosis of liver tumor cells in vivo.

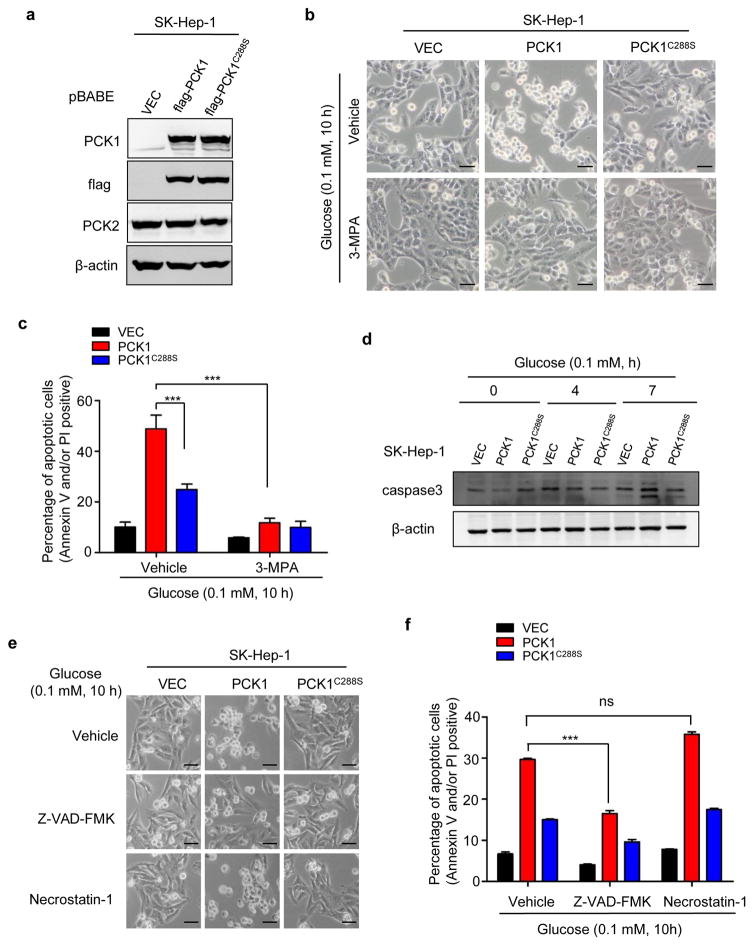

PCK1-promoted death of glucose-deprived cells requires its enzymatic activity and is mediated by caspase-dependent apoptosis

To determine whether the catalytic activity of PCK1 is required to cause cell death, a catalytically inactive PCK1(C288S) mutant15 was stably expressed in SK-Hep-1 cells (Fig. 3a). C288S mutation substantially reduced the cell death induced by glucose deprivation (Fig. 3b, c). Moreover, 3-mercaptopicolinic acid (3-MPA), a specific inhibitor of PCK1,16 almost completely inhibited the death of PCK-expressing cells under low glucose condition (Fig. 3b,c). These data indicate that the enzymatic activity of PCK1 is required for its effect in promoting glucose-deprived liver cancer cell death.

Figure 3. PCK1 induced death of glucose-deprived cells is dependent on PCK1 enzymatic activity and mediated by caspase-dependent apoptosis.

(a) Verification and comparison of ectopically expressed flag-tagged PCK1C288S mutant and wildtype PCK1. (b) Inhibition of PCK1 activity abolished its ability in promoting cell death after glucose deprivation. SK-Hep-1 cells ectopically expressing PCK1 or PCK1C288S described in (a) were cultured in media containing 0.1 mM of glucose in the absence or presence of PCK1 inhibitor 3-MPA (100 μM) for 10 h. Photos were taken using a phase-contrast microscope. Scale bars: 50 μm. (c) Quantification of cell death were detected by Annexin V and PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are the percentage of Annexin V and/or PI positive cells ± SD of triplicate samples (***p < 0.001). (d) Ectopic expression of PCK1 induced Caspase 3 cleavage. SK-Hep-1 cells were cultured in media containing 0.1 mM of glucose for the durations indicated. Caspase 3 level was detected by Western blotting. (e and f) Caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, but not necroptosis inhibitor Necrostatin-1, prevented the death of cells ectopically expressing PCK1 after glucose deprivation. SK-Hep-1 cells ectopically expressing PCK1 or PCK1C288S described in (a) were cultured in media containing 0.1 mM of glucose in the presence of Z-VAD-FMK (20 μM) or Necrostatin-1 (50 mu;M) for 10 h. Dead cells were examined and quantified by Annexin V and PI staining. Scale bars in (e): 50 mu;m. Results are the percentages of dead cells ± SD of triplicate samples (***p < 0.001; ns, no significance).

Cells stably expressing wild-type PCK1, but not vector, exhibited cleavage of caspase-3, a marker for the activation of apoptosis, after cultured in glucose-free medium for 10 h (Fig. 3d). Expression of catalytic inactive PCK1(C288S) mutant reduced, but not completely inhibited the cleavage of caspase-3. This is consistent with a partial inhibition of cell apoptosis by the PCK1(C288S) mutant when compared with the wild type PCK1 (Fig. 3b, c). Treatment of cells with Z-VAD-FMK, a pan-caspase inhibitor, significantly reduced the death of PCK1-expressing SK-Hep-1 liver cancer cells after glucose starvation (Fig. 3e, f). In contrast, Necrostatin-1, a necroptosis inhibitor, had no effect on cell death (Fig. 3e, f). Collectively, these data demonstrate that PCK1 induces liver cancer cell death under low glucose condition through apoptosis and requires its enzymatic activity.

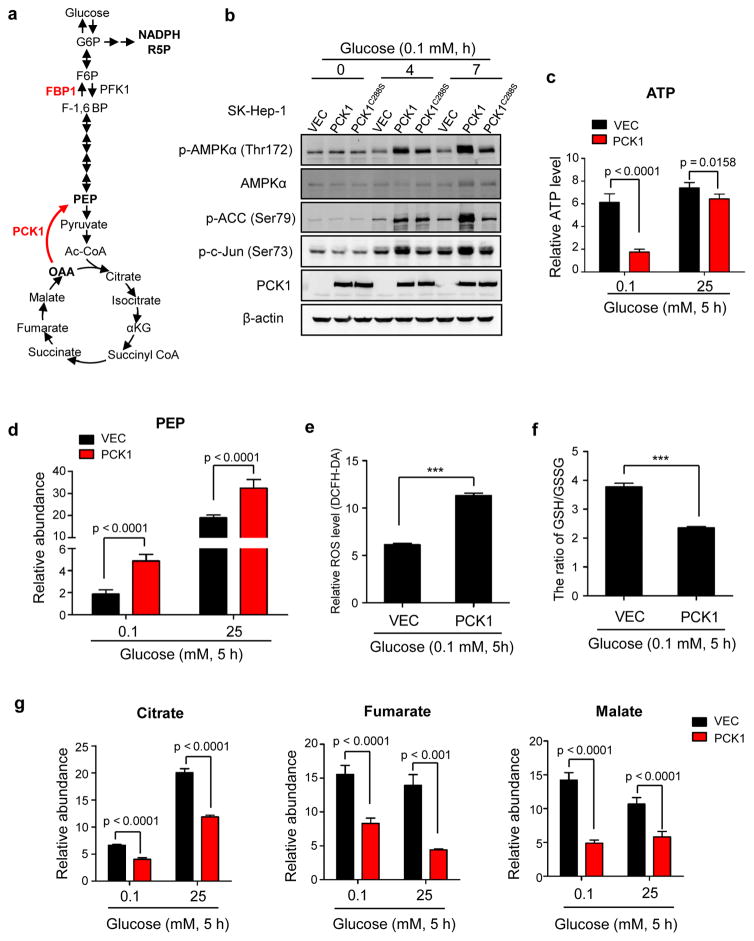

Enforced PCK1 expression induces TCA cataplerosis, energy crisis and oxidative stress in glucose-starved HCC cells

In addition to its well-known role of catalyzing the conversion of OAA to PEP in gluconeogenesis (Fig. 4a), PCK1 is also involved in energy generation and TCA cycle maintenance through regulating TCA cataplerosis.7, 17, 18 In searching for the mechanism underlying the pro-apoptotic effect of elevated PCK1 expression, we observed that ectopic expression of wild-type PCK1, but not catalytic inactive PCK1(C288S) mutant, significantly increased the phosphorylation of AMPKα1 on Thr172, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) on Ser79, and c-Jun on Ser73 under low glucose condition (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that elevated PCK1 expression in glucose-starving liver cancer cells may cause a stress condition linked to energy crisis. Supporting this notion, PCK1 expression in SK-Hep-1 dramatically reduced cellular ATP level by 4 folds in cells cultured in low glucose medium, but not in normal medium (Fig. 4c). Ectopic expression of PCK1 in another HCC cell line SMMC-7721 also significantly reduced ATP level in glucose-starved condition (Supplementary Fig. S3a).

Figure 4. PCK1 induced TCA cataplerosis, energy crisis and oxidative stress in liver cancer cells.

(a) A diagram illustrating the reactions catalyzed by PCK1 in regulating TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis. PFK1, phosphofructokinase1; FBP1, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 1. G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; F-1,6-BP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; OAA, oxaloacetate; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate. (b) PCK1 activated AMPKα1 in glucose-deprived cells. SK-Hep-1 cells expressing empty vector, wildtype or mutant PCK1 were cultured in media containing 0.1 mM of glucose for the durations indicated. Phospho-AMPKα1 (Thr172), phospho-ACC (Ser79) and phospho-c-Jun (Ser73) were examined by Western blotting. (c) Ectopic expression of PCK1 decreased cellular ATP level in glucose starved cells. SK-Hep-1 cells expressing empty vector or PCK1 were cultured in media containing 0.1 mM or 25 mM of glucose for 5 h, followed by measurement of cellular ATP level as described in Methods. Values represent mean ATP levels ± SD of quintuplicate samples (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001). (d) Relative abundance of PEP was increased in cells ectopically expressing PCK1. SK-Hep-1 cells expressing empty vector or PCK1 were cultured under conditions as described in (c). Relative abundance of cellular PEP was determined by LC-MS. Values represent mean PEP levels ± SD of quintuplicate samples (***p < 0.001). (e) Ectopic expression of PCK1 resulted in higher ROS level. SK-Hep-1 cells expressing empty vector or PCK1 were cultured in media containing 0.1 mM of glucose for 5 h. ROS level was detected by DCFH-DA staining as described in Methods. Values represent mean ROS level ± SD of triplicate samples (***p < 0.001). (f) Ectopic expression of PCK1 reduced GSH/GSSG ratio. SK-Hep-1 cells expressing empty vector or PCK1 were cultured under conditions described in (e). Cellular levels of GSH and GSSG were determined by LC-MS. Values represent mean ratios of GSH/GSSG ± SD of quadruplicate samples (***p < 0.001). (g) Relative abundance of citrate, malate and fumarate was significantly decreased in cells ectopically expressing PCK1. SK-Hep-1 cells expressing empty vector or PCK1 were cultured under conditions as described in (c). GC-MS was performed to detect the cellular levels of these metabolites. Values represent mean abundance of indicated metabolites ± SD of quintuplicate samples (***p < 0.001).

To elucidate how elevated PCK1 expression may affect ATP production and energy homeostasis, we performed mass spectrometry analysis to determine the glycolytic and TCA intermediates. As expected, PEP, the catalytic product of PCK1, was significantly increased in PCK1 expressing cells (Fig. 4d). 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG), a succeeding intermediate after PEP on the gluconeogenic pathway, was also increased; likely due to the equilibration of reversible reactions catalyzed by non-rate-limiting enzymes enolase and phosphoglycerate mutase (Supplementary Fig. S3b). 3PG can bind to and inhibit the activity of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, which catalyzes the conversion of 6-phosphogluconate to ribulose-5-phosphate on the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP).19 Ribose-5-phosphate (R5P), the succeeding intermediate after ribulose-5-phosphate, was decreased in PCK1 expressing, glucose-starving cells (Supplementary Fig. S3c).

R5P is a major intermediate of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) that protects cells against oxidative damage. A decrease in R5P suggests attenuated PPP and increased oxidative stress, leading us to examine the redox state of SK-Hep-1 cells. We found that the ROS level was dramatically elevated by two folds in PCK1-expressing, glucose-deprived SK-Hep-1 cells (Fig. 4e). Consistently, the ratio of GSH/GSSG was also significantly lower in PCK1 expressing SK-Hep-1 cells (Fig. 4f). Likewise, ectopic expression of PCK1 in another HCC cell line SMMC-7721 also resulted in higher ROS level culturing in low glucose media (Supplementary Fig. 3d), further supporting that elevated PCK1 induces oxidative stress.

Elevated PCK1 expression also led to a significant decrease in the relative abundance of citrate, fumarate and malate in whether SK-Hep-1 cells were cultured in glucose-rich (25 mM) or deprived (0.1 mM) media (Fig. 4g), indicating a severe TCA cataplerosis. Furthermore, the abundance of citrate, fumarate, malate and succinate was significantly reduced in PCK1-expressing glucose-starved SMMC-7721 cells (Supplementary Fig. S3e). Collectively, these data suggest that enforced PCK1 expression triggers glucose-deprived liver cancer cell death by causing truncated gluconeogenesis, energy crisis, TCA cycle cataplerosis and high ROS levels.

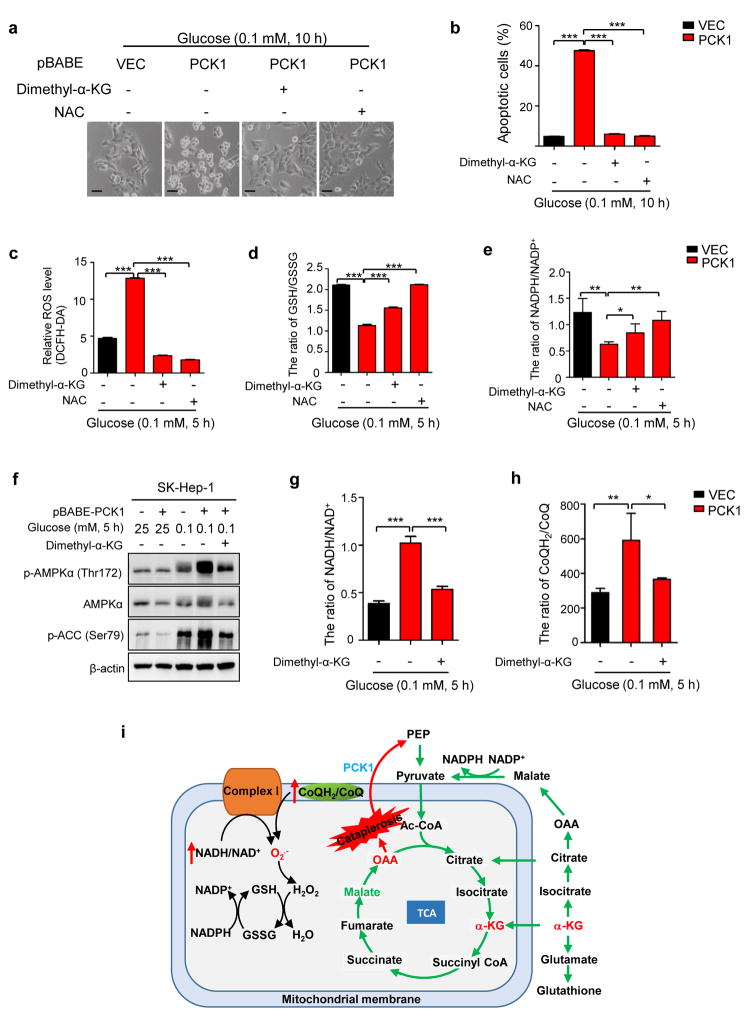

ROS suppression or α-KG replenishment blocks cell death caused by PCK1 expression under low glucose condition

To elucidate the role of ROS in PCK1 induced cell death, we treated cells with N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC), an inhibitor of ROS. Treatment of NAC in both SMMC-7721 and SK-Hep-1 significantly blocked cell death caused by PCK1 expression under low glucose condition (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. S4a). As PCK1 leads to a severe decrease in the relative abundance of TCA cycle intermediates (Fig. 4), we replenished TCA cycle with several cell membrane-permeable precursors of metabolic intermediates (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Interestingly, addition of dimethyl-α-ketoglutarate (dimethyl-α-KG) also significantly rescued the cell death of PCK1 expressing SMMC-7721 and SK-Hep-1 cells under low glucose condition (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. S4a). To a lesser extent, addition of cell-permeable pyruvate, succinate and malate also reduced the apoptosis of glucose-deprived cells caused by elevated PCK1 expression (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Addition of cell-permeable dimethyl-α-ketoglutarate also increased the levels of intracellular α-KG, fumarate, malate and citrate (Supplementary Fig. S4c), indicating an effective TCA anaplerosis. Addition of dimethyl-fumarate led to more severe cell death (Supplementary Fig. S4b), probably due to toxicity of the chemical.20, 21

Figure 5. ROS suppression or α-KG replenishment completely blocked the death of liver cancer cells ectopically expressing PCK1 upon glucose deprivation.

(a) Supplement of dimethyl-α-KG and NAC blocked the death of cells ectopically expressing PCK1 after glucose deprivation. SK-Hep-1 cells expressing empty vector or PCK1 were cultured in media containing 0.25 mM of glucose in the absence or presence of dimethyl-α-KG (5 mM) or NAC (10 mM) for 12 h. Photos were taken under a phase-contrast microscope. Scale bars: 50 μm. (b) Quantification of cell death in (a). Dead cells were detected by PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. Values represent mean percentages of dead cells ± SD of triplicate samples (***p < 0.001). (c, d and e) Dimethyl-α-KG and NAC reversed the upregulation of ROS levels (c) and downregulation of GSH/GSSG (d), and NADPH/NADP+ ratio (e) in PCK1-expressing, glucose-deprived cells. Values represent mean ROS levels ± SD of triplicate samples for (c), mean GSH/GSSG ratio ± SD of triplicate samples for (d), and mean NADPH/NADP+ ratio of triplicate samples for (e), respectively (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). (f) Supplement of dimethyl-α-KG reduced the phosphorylation of AMPKα1 and ACC in PCK1-expressing, glucose-deprived cells. (g and h) Supplement of dimethyl-α-KG inhibited the elevation of NADH/NAD+ in mitochondria (g) and CoQH2/CoQ (h) ratios induced by ectopic PCK1 expression. The ratio of NADH/NAD+ (g) in the mitochondria of cells was measured as described in Methods and the CoQH2/CoQ (h) ratios were estimated from the succinate/fumarate ratio. Values in (g) represent mean ratios of NADH/NAD+ ± SD of triplicate samples. Values in (h) represent mean ratios of CoQH2/CoQ ± SD of quintuplicate samples. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). (i) A working model that demonstrates ROS suppression or α-KG replenishment completely blocks death of liver cancer cells ectopically expressing PCK1 after glucose deprivation.

Previous studies demonstrated that α-KG plays a crucial role in redox homeostasis through increasing subsequent fumarate levels, which binds to and activates ROS-scavenging enzyme Gpx1.22 Indeed, either dimethyl-α-KG or NAC completely reversed the elevation of ROS induced by ectopic PCK1 expression under low glucose condition (Fig. 5c). High GSH/GSSG and NADPH/NADP+ ratios scavenge ROS and maintain cellular redox balance.23 We found that dimethyl-α-KG also partially reversed the decreases of GSH/GSSG and NADPH/NADP+ ratio in PCK1-expressing, glucose-deprived cells, while NAC completely reversed the decreases (Fig. 5d, e). In addition, supplement of dimethyl-α-KG may also increase cellular ATP level and alleviate energy stress, as indicated by the decreased phosphorylation of AMPKα1 and ACC (Fig. 5f). As ROS is mainly generated in mitochondria respiratory chain from complex I, high NADH/NAD+ ratio in mitochondrial matrix and high ratio of reduced coenzyme Q (CoQH2) to the oxidized Q (CoQ) contribute to superoxide (O2.−) generation.24 The ratio of NADH/NAD+ and CoQH2/CoQ were increased by two folds in PCK1 expressing cells compared to control cells (Fig. 5g, h). Consistently, this change was also reversed by the addition of dimethyl-α-KG (Fig. 5g, h). Collectively, these data indicate that α-KG and NAC inhibit apoptosis of PCK1-expressing, glucose-deprived liver cancer cells by preventing TCA cataplerosis and oxidative stress (Fig. 5i).

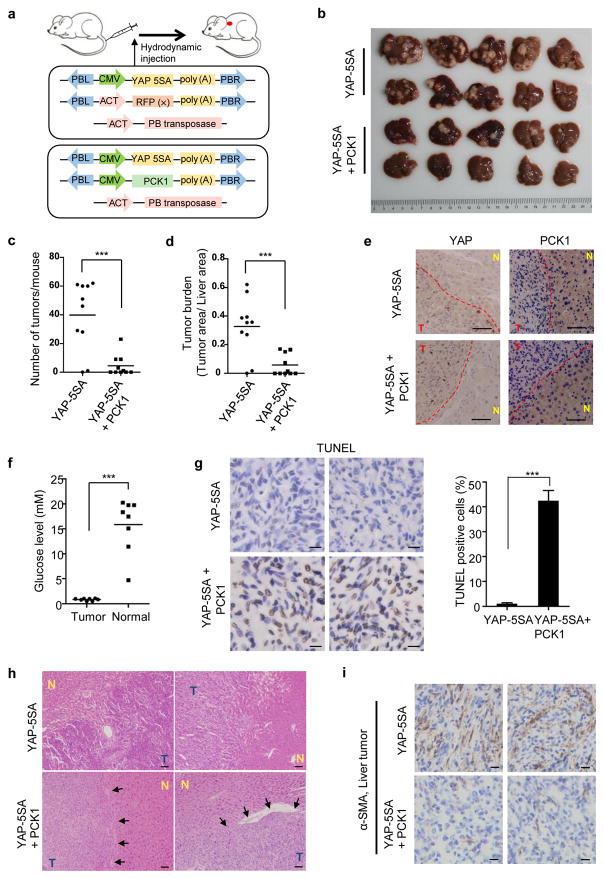

PCK1 suppresses liver tumorigenesis in vivo

We further investigated the functional roles of PCK1 in liver tumorigenesis using a model of inducible mouse primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Hydrodynamic injection of plasmids encoding YAP(5SA) and the piggyBac transposase which promotes chromosomal integration of co-injected plasmid induced liver tumors around 100 days post-injection.25 Consistent with its downregulation in human HCC, PCK1 was also significantly reduced in YAP-5SA induced mouse liver tumors (Supplementary Fig. S5a). Taking the advantage of the YAP(5SA) model, we hydrodynamically co-injected transposon plasmids encoding PCK1 together with YAP-5SA and the piggyBac transposase (Fig. 6a). Expression of exogenous YAP and PCK1 was readily detected in mouse liver 24 hours post injection, and co-expression of PCK1 did not appreciably affect the expression of YAP(5SA) (Supplementary Fig. S5b). Four months after injection, a number of visible tumors were observed on the surface of livers injected with YAP(5SA) (Fig. 6b), which is in accordance with a previous study.25 In contrast, expression of PCK1 significantly reduced the number of liver tumors and liver tumor burden on mice livers induced by the YAP(5SA) (Fig. 6c, d). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining demonstrated a consistent higher level of nuclear YAP(5SA) expression in tumor tissues than adjacent normal tissues in either group (Fig. 6e). PCK1 expression, on the other hands, was consistently lower in tumor cells when compared with adjacent normal tissues, regardless whether it is the tumors developed in YAP(5SA) singularly injected or YAP(5SA) and PCK1 co-injected mice. We analyzed the concentration of glucose within the microenvironment of 8 primary mouse liver tumors and normal, adjacent liver tissues. Our data showed that the glucose level of the tumor interstitial fluid (~0.8 mM) was approximately 19 times lower than that of the normal liver (~15 mM) (Fig. 6f), indicating a glucose-deprived condition. Higher percentage of TUNEL positive cells were observed in tumors developed from YAP(5SA)/PCK1 co-injected liver (Fig. 6g). This result provides additional evidence supporting that PCK1 negatively regulates tumor growth.

Figure 6. PCK1 suppresses liver tumorigenesis in vivo.

(a) Schematic of liver tumorigenesis model by the hydrodynamic injection. Transposon plasmid encoding YAP(5SA) and either vector or PCK1 were mixed at a ratio of 1:2, and were delivered into mice by hydrodynamic injection together with piggyBac transposase. (b–d) Ectopic expression of PCK1 significantly suppressed YAP(5SA) induced liver tumorigenesis. Mice were sacrificed at 4 months after hydrodynamic injection, and livers were collected and photographed (b). Tumor numbers (c) were counted and liver tumor area (d) was calculated using ImageJ software. The horizontal bars represent mean tumor numbers (c) and mean tumor area (d) of ten mice within each group (***p < 0.001). (e) Representative IHC staining of YAP and PCK1 of mice livers from each group. Dashed lines separate tumor tissues from adjacent normal liver tissues. Scale bars: 50 μm. T: liver tumor; N: adjacent normal liver tissue. (f) The glucose concentration in interstitial fluid of eight primary mouse liver tumors and normal, adjacent liver tissues (***p < 0.0001). (g) Much higher percentage of TUNEL positive cells was shown in liver tumors developed in mice co-injected with YAP(5SA) and PCK1 than tumors developed in mice injected with YAP(5SA) (***p < 0.001). Two representative IHC staining of TUNEL in each group were shown. Scale bars: 10 μm. (h) Histological diagnosis of HCC by H&E staining showed significant pathological differences between livers injected with YAP(5SA) and YAP(5SA)/PCK1. Arrows show representative capsules in H&E slides of livers co-injected with YAP(5SA) and PCK1, which separated tumor from adjacent normal liver tissue. Scale bars: 50 μm. T: liver tumor; N: adjacent normal liver tissue. (i) Much more severe fibrosis was shown in liver tumors developed in mice injected with YAP(5SA) than tumors developed in mice co-injected with YAP(5SA) and PCK1. Two representative IHC staining of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in each group were shown. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining also revealed some histological difference between YAP(S5A) singularly injected and YAP(S5A)-PCK1 co-injected liver tumors. YAP-5SA tumors displayed more disorganized lobular structure when compared with either adjacent normal tissues or tumors developed from YAP(5SA)/PCK1 co-injected liver. Moreover, liver tumors developed in mice co-injected with YAP(5SA) and PCK1 were smaller and often surrounded by an outer fibrous capsule (Fig. 6h), indicating a lack of metastasis potential. In comparison, no clear boundaries can be seen between tumors and adjacent normal tissues in the livers injected with YAP(5SA), indicating an invasive nature and a high risk of metastasis. Furthermore, liver tumors induced by YAP(5SA) have much more stromal cells when compared with those tumors developed in mice co-injected with YAP(S5A) and PCK1 plasmids (Fig. 6i). The interaction between stromal and tumor cells is known to play a major role in cancer progression.26, 27 Together, these phenotypes indicate that compared to liver tumors developed in mice injected with YAP(5SA), liver tumors that developed in mice co-injected with YAP(5SA) and PCK1 grew slower and less aggressively, supporting the notions that downregulation of PCK1 benefits liver tumor growth while forced PCK1 expression efficiently suppresses liver tumorigenesis in vivo.

Discussion

PCK1 plays critical regulator roles in controlling gluconeogenesis and its dysfunction has been linked to diabetes, obesity, insulin resistance, fatty liver, and other metabolic diseases.11, 13 Recent studies had linked altered PCK expression with cancer development. Increased expressions of PCK1 and its mitochondrial homologue PCK2 are found in cancer of several organs, including colon, lung and skin, and linked to increased anabolic metabolism and cell proliferation.7–9 These findings suggest an oncogenic function of PCK genes in the tissues. Surprisingly, we found that in more than 200 pairs of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and surrounding normal tissues we have examined, the expression of PCK1 and PCK2 were both significantly downregulated in HCC. Similar PCK1 downregulation was also previously observed in a smaller cohort of HCC.28 We determined the functional significance of PCK downregulation in HCC by showing that forced expression of either PCK1 or PCK2 in liver cancer cell lines led to significant apoptosis under low glucose condition. We provide a mechanism underlying growth inhibition and tumor suppressive function of PCK gene in liver cells by causing TCA cataplerosis, energy crisis and excessive oxidative damages in glucose-deprived liver cells. In contrast, the function of PCK appears to be important for maintaining anabolic metabolism in other type of cells. In colon cancer cells, PCK1 increases glucose uptake and glutamine utilization,7 while in lung cancer cells, mitochondrial PCK2 supports anabolic metabolism by promoting glutamine-to- OAA-to-PEP conversion.8 These results indicate that the functional consequence of gluconeogenic PCK1 and PCK2 expression are distinctively different during the development of tumors in different tissues; exhibiting an oncogenic activity in some cancer type such as non-gluconeogenic lung and colon tissues while suppressing the growth of tumors in other tissues or organs such as gluconeogenic livers. This notion is consistent with a previous report that fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP1), the second rate-limiting enzyme of gluconeogenic pathway, is depleted in clear cell renal carcinoma (ccRCC), the cancer of the other major gluconeogenic organ, kidney.29 Similarly, forced expression of FBP1 inhibited ccRCC cell growth in culture and also in a mouse liver cancer model. Hence, gluconeogenic enzymes may play different roles in non-gluconeogenic and gluconeogenic tissues. It is currently not clear how PCK expression results in such contrasting consequences in different cells, facilitating anabolic metabolism in some tissues and causing TCA cataplerosis and subsequent energy crisis in others. Further investigations on the precise mechanism of PCK1 will still be needed to illuminate why PCK1 has different functions in different tissues.

Upon glucose deprivation, enforced PCK1 expression induced cataplerosis results in severe reduction of TCA intermediates, leading to energy crisis and ROS increase. Supporting the notion that TCA cataplerosis causes cell death, supplement cells with TCA intermediate, α-KG, effectively rescued PCK1-induced energy crisis, oxidative stress and apoptosis of glucose-deprived liver cancer cells. In our study, a ROS inhibitor, NAC, also completely rescued PCK1-induced liver cancer cell death. It’s known that excessive TCA cataplerosis flux could provoke oxidative metabolism and induce oxidative stress.11 Although the increase of mitochondrial NADH/NAD+ ratio in PCK1-expressing cells could partially explain the ROS increase, whether the oxidative metabolism was changed and how the ROS was accumulated in PCK1-expressing liver cancer cells still need further exploration.

A major finding of this study is that forced expression of PCK1 significantly inhibited liver tumorigenesis in vivo in mice. Using a mouse model of inducible mouse primary hepatocellular carcinoma, we found that forced expression of PCK1 suppressed liver tumor growth induced by the oncoprotein YAP(5SA). Not only the rate of liver tumorigenesis was reduced by PCK1 expression, the YAP(5SA)/PCK1 liver tumors that developed in the mice were more benign on histology. PCK genes, although their expression significantly downregulated in HCC, are rarely mutated. These observations raise an intriguing possibility that inducing PCK gene expression may be exploited as a strategy for the treatment of HCC.

Methods

Chemical reagents, antibodies and plasmids

3-mercaptopicolinic acid, Z-VAD-FMK and Necrostatin-1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Dimethyl-2-oxoglutarate, dimethyl-fumarate, dimethyl-succinate and dimethyl-malate were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry, Sodium pyruvate and L-glutamine were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and dichlorofluorescin diacetate from Beyotime.

Antibodies against PCK1 (ab28455, Abcam), PCK2 (ab70359, Abcam) and YAP1 (ab52771, Abcam), phospho-AMPKα (Thr172) (Cell Signaling Technology, 2535), AMPKα (Cell Signaling, 2532), phospho-ACC (Ser79) (Cell Signaling, 11818) and phospho-c-Jun (Ser73) (Cell Signaling, 3270) were purchased commercially.

pBABE-Flag-PCK1 and pQCXIH-Flag-PCK2 were cloned from cDNA provided by Dr. Jiahuai Han (Xiamen University, Xiamen, China). The PB[CMV-myc-YAP-5SA]DS, PB[Act-RFP]DS and Act-PB Transposase plasmids were generous gifts from Dr. Bin Zhao (Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China). The PB[CMV-flag-PCK1]DS donor plasmids were constructed by excising Act-RFP from the PB[Act-RFP]DS plasmid and ligating the corresponding fragments excised from pQCXIH vectors.

Intracellular ROS, ATP level, NADPH/NADP+ ratio, mitochondrial NADH/NAD+ ratio and CoQH2/CoQ ratio measurements

Total intracellular ROS was determined by staining cells with dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA, Beyotime). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD AccuriTM C6). Intracellular ATP level, NADH/NAD+ ratio and NADPH/NADP+ ratio was determined using ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime), NAD/NADH Quantitation Colorimetric Kit (Biovision) and NADP/NADPH Quantitation Colorimetric Kit (Biovision) according to manufacturer’s instructions, respectively. Mitochondria was isolated as described30 for detecting mitochondrial NADH/NAD+ ratio. The ratio of CoQH2/CoQ was estimated as previously described11.

Intracellular metabolites measurements

The intracellular levels of PEP, 3PG, R5P, GSH and GSSG were determined by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The relative abundance of α-KG, succinate, citrate, fumarate and malate were detected using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The mass spectrometry was performed as previously described31 and analyzed using the Analyst Software (version 1.6).

Cell viability assay

Cell apoptosis was determined by using a commercial FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen), except for Figure 2D, in which cell viability was determined by cell counting after staining with trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, cells were collected, washed twice with cold PBS, and re-suspended in 1× Binding Buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; 140 mM NaCl; 2.5 mM CaCl2) at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml. FITC Annexin V (5 μl) and PI (5 μl) were added to 100 μl of the solution, followed by incubation for 15 min at room temperature (RT) in the dark. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD AccuriTM C6).

Xenograft and hydrodynamic injection

For Xenograft experiments, nude mice (athymic nu/nu, male, 6 weeks old; Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal) were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 105 SK-Hep-1 cells harboring empty vectors on the left flank, and cells with stable expression of PCK1 on the right flank, respectively. Mice were sacrificed 4 weeks after injection, and xenograft tumors were dissected and analyzed.

For hydrodynamic injection, male ICR mice (4 weeks of age, weighing 20–25 g) were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal. For each mouse, 60 μg of transposon plasmids and 10 μg of transposase-expressing plasmids were diluted in sterile Ringer’s solution in a volume equal to 10% of body weight and injected within 5 to 7 seconds through the tail vein.

Animals were randomly assigned to subcutaneous injection and hydrodynamic injection. Xenograft tumor experiments and hydrodynamic injection on mice were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Fudan University.

Tissue immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded liver cancer and matched normal liver tissue microarrays were obtained from Shanghai Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University. Freshly dissected mouse liver tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at RT, and embedded in a paraffin block. Paraffin-embedded slides were deparaffinized in xylene for 2 times, 3 min each, rehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions. After two washes in PBS for 5 min each, antigen retrieval was performed in Citrate Antigen Retrieval Solution (Beyotime) by boiling for 10 min. After cooling down to RT and rinsing with PBS for two times, the slides were blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum in PBS for 1 h at RT. Then, various primary antibodies were applied in a concentration of 8 μg/mL overnight at 4 °C. After wash with PBS, HRP conjugated secondary antibodies were added onto the slides for 1 h at RT. DAB substrate solution was used to reveal the color of antibody staining.

Glucose measurement

Isolation of liver interstitial fluid was performed as described32 and the glucose levels were determined using Glucose (GO) Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Cell culture

All the cancer cell lines were obtained from ATCC except SMMC-7721, BEL-7404 and L-O2 cell lines, which were gifts from Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences. MCF7 and A498 were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 units/ml penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen). SK-Hep-1, Hep3B, HepG2, SMMC-7721, L-O2, BEL-7404, HEK-293T and HEK-293 were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS. 786-O was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS. All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma and confirmed as negative. For low glucose treatment, cells were maintained in glucose-free DMEM (Life Technologies) with 10% dialyzed FBS (Gibco), supplemented with various concentrations of glucose. Dimethyl-2-oxoglutarate (5 mM), dimethyl-fumarate (0.2 mM), dimethyl-succinate (5mM), dimethyl-malate (5 mM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), L-glutamine (2 mM), NAC (10 mM), 3-MPA (100 μM), Z-VAD-FMK (20 μM) and necrostatin-1 (50 μM) were supplemented to the medium along with low glucose.

Virus infection

Retroviruses were employed to stably express PCK1 or PCK2 in SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells using pBABE and pQCXIH vectors respectively. Retroviral vectors were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells together with two packing plasmids expressing VSVG and GAG. Thirty-six hours after transfection, viruses in supernatant were collected and used to infect SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells. Cells stably expressing PCK1 or PCK2 were selected in puromycin (2 μg/mL) or hygromycin (50 μg/ml), respectively.

Retroviruses were used to stably knock down PCK1 in HepG2 cells using pMKO.1 vector. The sequences of siRNA targeting human PCK1 were present as following:

siPCK1 #1: GCACATCCCAACTCTCGATTT

siPCK1 #2: GCAGATCTGAAAGGCACACTT

Cell proliferation assay

SK-Hep-1 or HepG2 cells were seeded at 40,000 cells/well or 50,000 cells/well, in triplicate into 6-well plates and cell numbers were counted per day for 5 d or 7 d, respectively

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed by SDS gel-loading buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS and 0.0005% bromophenol blue. The lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Then, separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk diluted in TBST (20 mM Tris, 135 mM NaCl, and 0.02% Tween 20) for 1 h at RT, and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Primary antibodies were detected by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by exposure to ECL Plus (Thermo Fisher Technology).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from liver tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using oligo-dT primers in TransScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix supplied by Transgene Biotech and preceded to real-time PCR with gene-specific primers in the presence of SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa) in a 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). β-actin was used as a housekeeping control. Primer sequences were present as following:

PCK1-F: 5′-GAGAAAGCGTTCAATGCCAG-3′

PCK1-R: 5′-ATGCCGATCTTTGACAGAGG-3′

PCK2-F: 5′-AGCCTCTTCCACCTGGTGTT-3′

PCK2-R: 5′-AATCGAGAGTTGGGATGTGC-3′

Actin-F: 5′-GCACAGAGCCTCGCCTT-3′

Actin-R: 5′-GTTGTCGACGACGAGCG-3′

Statistics

Statistical analysis and graphical presentation were performed using Prism 5 (GraphPad), except for TCGA data analysis, which was presented by R language. Data shown are from one representative experiment of at least three independent experiments and are given as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis of significance was based on the two-tailed Student’s t-test for all the figures, except for Figure 1J and 1K, which was calculated by Wilcoxon rank sum test, and except for Figure 5H, which was based on the one-tailed Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was provided for all cases and the variance among groups was not statistically different. The sample sizes were determined on the basis of previous experience in the laboratory and pre-specified effect sizes considered to be biological significant. No samples or animals were excluded from any analyses and all replicates were authentic biological replicates. Blind analysis was not performed in this study.

Human study approval

Written informed consent was obtained from each HCC patients who underwent surgery at the Liver Cancer Institute, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. This study was approved by the Zhongshan Hospital Research Ethics Committee.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bin Zhao (Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China) for providing plasmids used for inducing liver tumor in mice, including PB[CMV-myc-YAP-5SA]DS, PB[Act-RFP]DS and Act-PB Transposase. We thank Xiaocan Guo for technical help on hydrodynamic injection. We also thank Dr. Jiahuai Han (Xiamen University, Xiamen, China) for generously offering cDNAs for human PCK1 and PCK2 genes. This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2017ZX10203207-002-004 to H.X.Y.), the 973 Program (No. 2015CB910401 to Y.X.), the NSFC grants (No. 31570784 and 81773190 to H.X.Y.), and NIH grants (CA163834 to Y.X.; CA196878 and GM51586 to K.L.G.).

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

Kun-Liang Guan is co-founder of Vivace Therapeutics.

References

- 1.Hsu PP, Sabatini DM. Cancer cell metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell. 2008;134:703–707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess SC, He T, Yan Z, Lindner J, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, et al. Cytosolic Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase Does Not Solely Control the Rate of Hepatic Gluconeogenesis in the Intact Mouse Liver. Cell Metab. 2007;5:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Kalhan SC, Hanson RW. What Is the Metabolic Role of Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase? J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27025–27029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.040543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Méndez-Lucas A, Duarte JA, Sunny NE, Satapati S, He T, Fu X, et al. PEPCK-M expression in mouse liver potentiates, not replaces, PEPCK-C mediated gluconeogenesis. J Hepatol. 2013;59:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montal ED, Dewi R, Bhalla K, Ou L, Hwang BJ, Ropell AE, et al. PEPCK Coordinates the Regulation of Central Carbon Metabolism to Promote Cancer Cell Growth. Mol Cell. 2015;60:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent EE, Sergushichev A, Griss T, Gingras MC, Samborska B, Ntimbane T, et al. Mitochondrial Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase Regulates Metabolic Adaptation and Enables Glucose-Independent Tumor Growth. Mol Cell. 2015;60:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leithner K, Hrzenjak A, Trötzmüller M, Moustafa T, Köfeler HC, Wohlkoenig C, et al. PCK2 activation mediates an adaptive response to glucose depletion in lung cancer. Oncogene. 2014;34:1044–1050. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunny NE, Parks EJ, Browning JD, SCB Excessive Hepatic Mitochondrial TCA Cycle and Gluconeogenesis in Humans with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Metab. 2011;14:804–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satapati S, Kucejova B, Duarte JA, Fletcher JA, Reynolds L, Sunny NE, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism mediates oxidative stress and inflammation in fatty liver. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4447–4462. doi: 10.1172/JCI82204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owen OE, Kalhan SC, Hanson RW. The Key Role of Anaplerosis and Cataplerosis for Citric Acid Cycle Function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30409–30412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beale EG, Harvey BJ, Forest C. PCK1 and PCK2 as candidate diabetes and obesity genes. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2007;48:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirayama A, Kami K, Sugimoto M, Sugawara M, Toki N, Onozuka H, et al. Quantitative Metabolome Profiling of Colon and Stomach Cancer Microenvironment by Capillary Electrophoresis Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4918–4925. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunten P, Belunis C, Crowther R, Hollfelder K, Kammlott U, Levin W, et al. Crystal structure of human cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase reveals a new GTP-binding site. J Mol Biol. 2001;316:257–264. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balan MD, McLeod MJ, Lotosky WR, Ghaly M, Holyoak T. Inhibition and Allosteric Regulation of Monomeric Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase by 3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid. Biochemistry. 2015;54:5878–5887. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgess SC, Hausler N, Merritt M, Jeffrey FM, Storey C, Milde A, et al. Impaired tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in mouse livers lacking cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48941–48949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakimi P, Johnson MT, Yang J, Lepage DF, Conlon RA, Kalhan SC, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and the critical role of cataplerosis in the control of hepatic metabolism. Nutr Metab. 2005;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hitosugi T, Zhou L, Elf S, Fan J, Kang HB, Seo JH, et al. Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 coordinates glycolysis and biosynthesis to promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:585–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan LB, Martinez-Garcia E, Nguyen H, Mullen AR, Dufour E, Sudarshan S, et al. The proto-oncometabolite fumarate binds glutathione to amplify ROS-dependent signaling. Mol Cell. 2013;51:236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng L, Cardaci S, Jerby L, MacKenzie ED, Sciacovelli M, Johnson TI, et al. Fumarate induces redox-dependent senescence by modifying glutathione metabolism. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6001. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin L, Li D, Alesi GN, Fan J, Kang HB, Lu Z, et al. Glutamate Dehydrogenase 1 Signals through Antioxidant Glutathione Peroxidase 1 to Regulate Redox Homeostasis and Tumor Growth. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabharwal SS, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles’ heel? Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nrc3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen S, Guo X, Yan H, Lu Y, Ji X, Li L, et al. A miR-130a-YAP positive feedback loop promotes organ size and tumorigenesis. Cell Res. 2015;25:997–1012. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernandez-Gea V, Toffanin S, Friedman SL, JM L. Role of the microenvironment in the pathogenesis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:512–527. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tlsty TD, Coussens LM. Tumor Stroma and Regulation of Cancer Development. Annu Rev Pathol-Mech. 2006;1:119–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao Y, Keller ET, Garfield DH, Shen K, Wang J. Stromal cells in tumor microenvironment and breast cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, Qiu B, Lee DS, Walton ZE, Ochocki JD, Mathew LK, et al. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase opposes renal carcinoma progression. Nature. 2014;513:251–255. doi: 10.1038/nature13557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang H, Zhou L, Shi Q, Zhao Y, Lin H, Zhang M, et al. SIRT3-dependent GOT2 acetylation status affects the malate-aspartate NADH shuttle activity and pancreatic tumor growth. EMBO J. 2015;34:1110–1125. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma S, Jiang B, Deng W, Gu ZK, Wu FZ, Li T, et al. D-2-hydroxyglutarate is essential for maintaining oncogenic property of mutant IDH-containing cancer cells but dispensable for cell growth. Oncotarget. 2015;6:8606–8620. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haslene-Hox H, Oveland E, Berg KC, Kolmannskog O, Woie K, Salvesen HB, et al. A New Method for Isolation of Interstitial Fluid from Human Solid Tumors Applied to Proteomic Analysis of Ovarian Carcinoma Tissue. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.