Abstract

Cells address challenges to protein folding in the secretory pathway by engaging endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized protective mechanisms that are collectively termed the unfolded protein response (UPR). By the action of the transmembrane signal transducers IRE1, PERK, and ATF6, the UPR induces networks of genes whose products alleviate the burden of protein misfolding. The UPR also plays instructive roles in cell differentiation and development, aids in the response to pathogens, and coordinates the output of professional secretory cells. These functions add to and move beyond the UPR’s classical role in addressing proteotoxic stress. Thus, the UPR is not just a reaction to protein misfolding, but also a fundamental driving force in physiology and pathology. Recent efforts have yielded a suite of chemical genetic methods and small molecule modulators that now provide researchers with both stress-dependent and -independent control of UPR activity. Such tools provide new opportunities to perturb the UPR and thereby study mechanisms for maintaining proteostasis in the secretory pathway. Numerous observations now hint at the therapeutic potential of UPR modulation for diseases related to the misfolding and/or aggregation of ER client proteins. Growing evidence also indicates the promise of targeting ER proteostasis nodes downstream of the UPR. Here, we review selected advances in these areas, providing a resource to inform ongoing studies of secretory proteostasis and function as they relate to the UPR.

1. Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is responsible for secretory proteostasis, involving the coordinated folding, processing, quality control, and trafficking of ~1/3 of the proteome. Protein folding is a highly complex and error-prone process, requiring a delicate balance between function and risk of aggregation in crowded biological microenvironments where total protein concentrations can range from 100–400 mg/mL (Gershenson et al. 2014; Hartl et al. 2011). ER clients, which include secreted, membrane, and lysosomal proteins, face additional challenges, including unique post-translational modifications (e.g., N-glycosylation) that require specialized cellular machinery (Aebi 2013), oxidative folding processes associated with selective disulfide bond formation (Tu and Weissman 2004), and both spatial and temporal restraints on the completion of folding, modification, assembly, and transport steps. Cells account for this complexity via a diverse array of folding (Hartl et al. 2011) and quality control mechanisms (Smith et al. 2011a), some of which are only recently coming to light. The resulting balance of protein synthesis, folding, and recycling is essential for health. Dysregulated proteostasis in the secretory pathway underpins a diverse array of diseases.

Maintaining secretory proteostasis requires the ability to dynamically respond to challenges such as protein misfolding, often by large-scale remodeling of the ER and the ER proteostasis environment (Walter and Ron 2011). The unfolded protein response (UPR; Figure 1) is the central stress response pathway involved. The three arms of the metazoan UPR are controlled by the signal transducers IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 (Cox et al. 1993; Harding et al. 1999; Haze et al. 1999; Tirasophon et al. 1998). Activation of these ER transmembrane proteins induces a transcriptional response mediated by three transcription factors, XBP1s (Calfon et al. 2002; Yoshida et al. 2001), ATF4 (Harding et al. 2000; Vattem and Wek 2004), and ATF6f (ATF6-fragment) (Adachi et al. 2008). This coordinated transcriptional response alleviates the burden of protein misfolding in the secretory pathway by upregulating ER chaperone, quality control, and secretion mechanisms (Adachi et al. 2008; Harding et al. 2000; Shoulders et al. 2013b). UPR activation also inhibits protein translation to lower the net nascent protein load on the ER, a process mediated primarily by PERK activation and subsequent phosphorylation of eIF2α (Harding et al. 1999), but also influenced by the selective degradation of ER-directed mRNA transcripts by IRE1 (Hollien et al. 2009; Moore and Hollien 2015). If proteostasis cannot be restored, pro-apoptotic mechanisms within the UPR are engaged leading to programmed cell death primarily through induction of the transcription factor CHOP downstream of PERK.

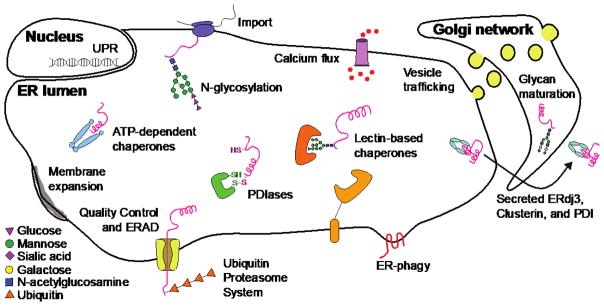

Figure 1. The unfolded protein response (UPR).

Accumulation of misfolding proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) activates the transmembrane protein UPR signal transducers PERK, IRE1, and ATF6. Dimerization and auto-phosphorylation of PERK and IRE1, or trafficking to the Golgi and subsequent proteolytic processing of ATF6, result in the production of the UPR transcription factors by enhancing translation of ATF4, splicing XBP1 mRNA to yield XBP1s, and releasing ATF6f from the Golgi membrane. These transcription factors proceed to the nucleus and remodel the ER proteostasis environment by upregulating chaperones, quality control components, and other UPR target genes to maintain or recover secretory proteostasis. PERK can globally reduce the nascent protein load on the ER via phosphorylation of eIF2α, a pathway that can be similarly induced by the integrated stress response. The RNase domain of activated IRE1 degrades several ER-targeted transcripts and may play a related role.

While extensive research has yielded a relatively well-defined picture of the UPR, the discovery of new regulatory mechanisms continues to shape our understanding of how the UPR relates to ER homeostasis. The ER not only functions as a protein-folding factory, but also participates in calcium storage and lipid biosynthesis (Fu et al. 2011). Along these lines, a recent study highlighted the capacity of IRE1’s membrane spanning domain to activate the protein in response to lipid perturbation even when the luminal protein misfolding stress-sensing domain is deleted using CRISPR/Cas9 (Kono et al. 2017). Moreover, the ER is involved in cellular responses to oxidative stress, metabolic imbalance, and pathogen invasion (Malhotra and Kaufman 2007; Roy et al. 2006; Volmer and Ron 2015). Each of these processes is modulated by the UPR. Thus, despite its moniker, the UPR is not simply a reaction to protein misfolding, but is instead a fundamental driving force for physiology and pathology. The central roles of the UPR in health and disease have catalyzed the development of methods to modulate the UPR, with the goal of better understanding key regulatory axes and identifying opportunities to influence phenotypic outcomes. Below, we review our current picture of the metazoan UPR in the context of secretory proteostasis, from its connections to health and disease (Section 2), to methods for selectively perturbing the UPR and their potential applications in disease therapy (Section 3), to efforts to target downstream nodes in ER proteostasis (Section 4).

2. The UPR in Health and Disease

Key functional nodes within the ER proteostasis network include chaperones, quality control mechanisms, post-translational modifiers, and trafficking pathways (Figure 2). Each of these nodes is dynamically regulated by the UPR to match proteostatic capacity to demand, thereby maintaining balanced levels of protein folding and quality control both during normal cellular function and under stressful conditions.

Figure 2. Representative nodes in the secretory proteostasis network.

Diverse proteins and pathways collectively modulate folding, secretion, quality control, and/or degradation of ER clients. ATP-dependent chaperones and PDIases assist in the folding of client proteins, as do lectin-based chaperones such as calnexin and calreticulin. Terminally misfolded proteins are typically cleared by ER-associated degradation (ERAD) via the ubiquitin-proteasome system. ER-phagy can serve as a counterpart to membrane expansion mechanisms, reducing organelle size to regulate ER proteostasis. Meanwhile, calcium flux, vesicle trafficking, and UPR-mediated changes in the chaperone: client balance, import, disulfide bond formation, and N-glycosylation of nascent polypeptides help to maintain or create favorable folding conditions and buffer ER protein-folding capacity. A handful of chaperones, includingERdj3, can accompany proteins to the extracellular space.

2.1 Development, Professional Secretory Cells, and Immunity

The UPR has critical roles during development that have been demonstrated in several model systems (Coelho et al. 2013; Shen et al. 2001). In particular, UPR activation appears to upregulate ER-resident chaperones and signaling pathways, which work collectively to relieve stress and regulate development in differentiating cells (Dalton et al. 2013; Laguesse et al. 2015; Reimold et al. 2001). For example, upon B-cell differentiation into plasma cells, the ER undergoes extensive XBP1-driven expansion (Reimold et al. 2001; Shaffer et al. 2004), in part to accommodate high levels of antibody synthesis. B-Cell differentiation in vitro also induces the UPR-regulated proteins XBP1s, BiP and Grp94. Notably, the process occurs without expression of CHOP or inhibition of protein translation, suggesting that a physiologic UPR need not involve all three UPR arms, in contrast to the case of attenuating stress-induced protein misfolding. Moreover, induction of XBP1, BiP and Grp94 transcripts apparently occurs prior to any significant protein-folding load on the ER, suggesting further differences between developmental and stress-associated signaling pathways (Gass et al. 2002). Other professional secretory cells such as pancreatic β-cells, hepatic cells, and osteoblasts also must sustain high rates of ER client protein synthesis, folding, and secretion, and thus rely on the UPR and its downstream signaling mechanisms for survival and function.

Other work highlights roles of the UPR in cellular responses to pathogen invasion. Binding of unfolded cholera toxin A subunit induces IRE1α ribonuclease activity but not the canonical UPR involving PERK and ATF6 (Cho et al. 2013). The fragments of endogenous mRNA produced by IRE1α prompt RIG-I to activate NF-κB and interferon signaling. Other work indicates that Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in macrophages promote splicing of XBP1 to optimize the production of proinflammatory cytokines (Martinon et al. 2010), although XBP1s can also be essential in protecting against the effects of prolonged inflammation (Adolph et al. 2013; Richardson et al. 2010). Intriguingly, viral pathogens are capable of hijacking the UPR to promote proliferation in host cells. For example, IRE1 activity is critical for the replication of at least some strains of the influenza virus (Hassan et al. 2012). In contrast, HSV1 suppresses both PERK and IRE1 signaling: glycoprotein B interacts with the luminal domain of PERK to block kinase activation, the late viral protein γ1 34.5 recruits PP1α to dephosphorylate eIF2α, and the UL41 protein acts as an endoribonuclease to degrade XBP1 mRNA (Zhang et al. 2016). Similarly, recent studies of L. pneumophila, the organism responsible for Legionnaires’ disease, show that the pathogen forestalls a prototypical ER stress response by repressing translation of a subset of UPR-associated genes to prevent host-cell apoptosis that would otherwise be induced (Hempstead and Isberg 2015; Treacy-Abarca and Mukherjee 2015). The relevant bacterial effector proteins may serve as springboards for biomimetic approaches to modulate UPR pathways.

2.2 Emerging Functions of the UPR

Beyond established roles in development and immunity, new functions for and consequences of the UPR continue to emerge. ER recycling via ER-phagy is critical for ER homeostasis (Bernales et al. 2006), and several constituent biochemical pathways were recently mapped (Fumagalli et al. 2016; Khaminets et al. 2015). A possible role for the IRE1-XBP1s arm of the UPR in inducing such ER-phagy may exist (Margariti et al. 2013). By reducing organelle size and/or disposing of dysfunctional ER regions, UPR induction of selective ER-phagy could serve as a counterpart to membrane expansion mechanisms for resolving ER stress (Schuck et al. 2009).

The discovery that the IRE1-XBP1s axis of the UPR is responsible for cell non-autonomous UPR activation (Taylor and Dillin 2013) is also intriguing. Such cell-to-cell communication of stress is likely to have important biological consequences that merit further investigation. ATF6 activation was recently shown to increase not just expression but also secretion of ERdj3, an ER-localized HSP40 co-chaperone (Genereux et al. 2015). The consequent co-secretion of ERdj3 with misfolded client proteins may be protective for the origin cell or ameliorate harmful protein aggregation in the extracellular milieu. Stress-induced ERdj3 secretion thus provides a mechanism by which the UPR can modify not just ER but also extracellular proteostasis.

Emerging functions of the UPR described above focus on direct modulation of protein folding and production. In addition to these mechanisms, a role for the ER in regulating the extent of protein post-translational modifications has emerged. For example, two groups showed that the UPR can modulate hexosamine biosynthesis to promote ER client clearance and prolong life in the face of chronic protein misfolding stress (Denzel et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014). These studies suggest that UPR activation, and especially the IRE1-XBP1s arm of the UPR, may enhance the extent of client protein N- and O-glycosylation and/or modify oligosaccharyltransferase efficiency. While the consequences merit further investigation, N-glycosylation promotes both ER client folding by providing access to the lectin-based chaperone machinery and the identification of misfolded proteins for ER-associated degradation (ERAD) via the lectin-based quality control machinery, providing a potential rationale for IRE1-XBP1s enhanced N-glycosylation (Ruiz-Canada et al. 2009).

Surprisingly, the UPR can also remodel the actual molecular architecture of N-glycans added to ER client proteins by modulating their biosynthesis (Dewal et al. 2015). Stress-independent activation of XBP1s changes transcript levels of N-glycan modifying enzymes, leading to altered mature glycan structures on model secreted N-glycoproteins. More work is required to establish the biological relevance and consequences of this phenomenon. However, this newly established connection between N-glycan signatures and the UPR suggests that the UPR may unexpectedly influence processes such as cell–cell interactions, cell–matrix interactions, and trans-cellular communication by actually modifying the molecular structure of secreted ER clients (Dewal et al. 2015).

2.3 Dysregulated ER Proteostasis and Disease

When proteostasis networks function properly, cells maximize production of properly folded, functional proteins. Meanwhile, quality control mechanisms ensure that only folded proteins are transported to their final locations, while production of misfolded and aggregated proteins is minimized (Figure 3a). The UPR regulates this process by sensing the accumulation of misfolded proteins, whether due to genetic mutations or adverse physiological conditions, and remodeling the ER proteostasis network to resolve emerging problems.

Figure 3. Proteostasis (im)balances in health and disease.

(A) When proteostasis is properly balanced, production of folded, functional client proteins and quality control surveillance are maximized, while misfolding and aggregation are minimized. Maintaining the balance between production of folded, functional proteins and quality control or clearance of misfolded, non-functional proteins is essential for health. In protein misfolding/aggregation disorders linked to defects in ER proteostasis, (B) insufficient quality control, (C) hyperactive quality control and failed folding, and/or (D) failed clearance leading to intracellular protein aggregation and chronic ER stress/UPR activation can all cause a pathologic loss of proteostasis balance. Modulating proteostasis network activities holds potential to resolve such defects.

Chronically dysregulated ER proteostasis, unresolved by the UPR, leads to diverse protein misfolding and aggregation-related diseases. For many mutations that destabilize or prevent the folding of a protein, the UPR may in principle have the potential to resolve the proteostatic defect – if it is activated. However, just one mutant protein misfolding in a background of thousands of well-behaved proteins may not always be a sufficient signal to trigger a protective UPR. In other cases, the ER may be overwhelmed by high concentrations of an aggregating mutant protein, leading to chronic ER stress and cellular apoptosis. In either scenario, pharmacologic perturbation of the UPR could be therapeutically useful. Moreover, many cancer cells rely on constitutive activation of pro-survival pathways (in particular the IRE-XBP1s arm) within the UPR (Chen et al. 2014b; Jamora et al. 1996; Mimura et al. 2012). This observation suggests that UPR inhibition could also prove valuable for diseases that do not stem directly from protein misfolding.

2.4 Concept Summary

Even this cursory survey of the roles of the UPR in health and disease reveals a striking functional spectrum. Beyond the traditional UPR, IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 participate in various normal physiological processes, upregulating UPR-associated transcripts to facilitate differentiation and sustain the activity of professional secretory cells. Studies on different models of pathogen infection demonstrate that UPR arms also can be selectively suppressed or activated in order to bypass cytotoxic stress-signaling pathways and promote cell survival. Such mechanisms are appealing starting points for efforts to better understand and manage cases of chronic ER stress associated with disease. Finally, recent findings suggest new roles for the UPR in regulating extracellular proteostasis and signaling, perhaps via post-translational alterations in ER client protein molecular structures(Dewal et al. 2015).

3. Targeting the UPR to Modulate ER Proteostasis

The intrinsic functions of the UPR in development and immunity, regulating cell survival and death, and resolving proteostatic stress have motivated extensive method development efforts to uncover small molecule UPR activators and inhibitors. Such tools are enabling detailed dissection of innate UPR function and revealing the therapeutic potential associated with targeting the UPR. This section reviews selected chemical genetic and small molecule approaches to modulate the UPR, and briefly describes insights obtained using such methods in disease model systems.

3.1 Stress-Dependent Methods to Modulate the UPR

Traditional approaches to activate the UPR rely on small molecules that cause ER stress. Such compounds include tunicamycin, which inhibits protein N-glycosylation; thapsigargin, which disrupts ER calcium homeostasis; and dithiothreitol, which reduces disulfides. All these methods globally and strongly activate the UPR by inducing extensive protein misfolding and aggregation. While such strategies have proven valuable for mapping UPR signaling pathways, they are less suited for mechanistic work as they induce high and physiologically irrelevant levels of stress. Moreover, these compounds are not helpful for therapeutic proof-of-principle studies, as the cytotoxic and pleiotropic side effects of their use obscure any potentially beneficial effects of UPR activation.

One approach to bypass these issues is to administer very low concentrations of ER toxins to induce only moderate stress (Rutkowski et al. 2006). Alternatively, a chemical genetic strategy was recently pioneered to transiently activate the UPR without inducing apoptosis (Raina et al. 2014). The method involves expressing an ER-targeted HaloTag protein that can be conditionally destabilized by conjugation to a small molecule hydrophobic tag (HyT36). Treatment of ER-targeted HaloTag-expressing cells with HyT36 destabilizes the protein, causing mild but acute accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER and consequent UPR activation. While the mechanistic details are not yet fully elucidated, the ERHT/HyT36 system provides a valuable tool to study aspects of global UPR activation distinct from the stress-independent, arm-selective techniques described below.

3.2 Stress-Independent Methods to Modulate the UPR

An important element of any strategy to discover and validate small molecule UPR arm activators is verifying that the compounds directly and selectively activate a particular arm of the UPR, without inducing ER protein misfolding or other forms of stress. To address this concern, recent work has delineated comprehensive transcriptional profiling strategies to validate stress-independent, arm-specific UPR activators (Plate et al. 2016). While several small molecule leads have been developed that activate endogenous IRE1 and/or ATF6 (Mendez et al. 2015; Plate et al. 2016), potency and selectivity, as well as mechanistic characterization, will benefit from further work. Selective small molecule activators of endogenous PERK have thus far proven elusive. On the other hand, salubrinal (Boyce et al. 2005), guanabenz (Tsaytler et al. 2011), ISRIB (Sidrauski et al. 2015), and Sephin1 (Das et al. 2015) can modulate the PERK-induced translational block either up or down by altering eIF2α phosphorylation status (Figure 1). Other explanations for the biological phenotypes induced by guanabenz and Sephin1 may also prove relevant (Crespillo-Casado et al. 2017). Notably, these compounds also modulate overlapping aspects of the integrated stress response, rendering such small molecules neither UPR- nor PERK-specific. For example, salubrinal also targets the constitutively expressed eIF2α phosphatase CReP (Boyce et al. 2005). Finally, while small molecule inhibitors of endogenous IRE1 have been well characterized (Cross et al. 2012; Volkmann et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2012), compounds that inhibit ATF6 are only now beginning to emerge (Gallagher and Walter 2016).

Given the paucity of small molecules to modulate arms of the UPR in a stress-independent manner, over the past fifteen years the field has turned to chemical genetic approaches. One strategy involves fusion of PERK’s kinase domain to a tandem-modified FK506-binding domain, Fv2E. Treatment with the small molecule AP20187 induces Fv2E-PERK dimerization, auto-phosphorylation, and downstream PERK signaling (Lin et al. 2009; Lu et al. 2004). The Fv2E fusion strategy was also applied to recapitulate the regulated RNase activity of IRE1 (Back et al. 2006). A complementary strategy based on bump-hole protein engineering employs an I624G mutation to allow binding of a small molecule ligand in the ATP pocket of IRE1, but not other kinase active sites, resulting in selective, stress-independent activation of IRE1’s RNase domain. Addition of the ligand 1NM-PP1 to cells expressing IRE1αI624G results in selective IRE1-dependent XBP1 mRNA splicing in the absence of ER stress (Dan et al. 2008; Han et al. 2009; Papa et al. 2003). These PERK and IRE1-targeted chemical genetic strategies allow for uncoupling of UPR arm activation from stress, but require careful engineering of cells to ensure minimal background signaling and robust inducibility. Their application has helped to clarify the consequences of ER stress. For example, chronic PERK activity, but not 1NM-PP1-induced IRE1 activity, is cytotoxic, suggesting a model in which the duration of PERK signaling regulates cell survival versus apoptosis decisions (Lin et al. 2009). Intriguingly, the advent of RNase inhibitors targeting wild-type IRE1, such as KIRA6, revealed that IRE1 can also promote apoptosis through formation of oligomers with hyperactive RNase activity (Ghosh et al. 2014). Thus, cell fate may not necessarily determined by opposing signals from IRE1 and PERK, but rather by the degree and timescale of activation (whether homeostatic or cytotoxic) experienced by both kinases.

An alternative chemical genetic strategy is to confer small molecule-dependent activity upon the UPR transcription factors, independent of the upstream signal transducers IRE1, PERK, and full-length ATF6. This approach has proven most successful for XBP1s and ATF6f (Figure 1). In the simplest case, tetracycline (Tet)-regulated expression of the UPR transcription factors ATF6f (Okada et al. 2002) and XBP1s (Lee et al. 2003; Shoulders et al. 2013b) under control of the Tet-repressor domain has been applied in several model systems. A challenge is the requirement for incorporation of the Tet-repressor in target cells and tissues. Moreover, Tet control of protein expression is rarely dose-dependent, resulting in high, non-physiologic levels of the Tet-inducible gene (Shoulders et al. 2013a; Shoulders et al. 2013b). Such overexpression of UPR transcription factors can cause off-target mRNA upregulation and often induces apoptosis, limiting its applicability.

More recently, destabilized domains (Banaszynski et al. 2006; Iwamoto et al. 2010) were leveraged to achieve orthogonal activation of XBP1s and/or ATF6f in a single cell. Fusing a destabilized variant of the dihydrofolate reductase from E. coli (DHFR) to the N-terminus of ATF6f results in a constitutively expressed DHFR.ATF6f fusion protein that is directed to rapid proteasomal degradation. Addition of the small molecule pharmacologic chaperone trimethoprim stabilizes DHFR, preventing degradation and allowing the DHFR-fused ATF6f transcription factor to function (Shoulders et al. 2013b). A related approach was used to control the activity of the XBP1s transcription factor, via fusion to an FKBP12 destabilized domain that can be stabilized by the small molecule Shield-1 (Shoulders et al. 2013a). The method requires minimal cell engineering, can be used in virtually any cell line of interest (including primary cells), and provides for highly dose-dependent control of transcription factor activity within the physiologically relevant regime. Moreover, fusion of destabilized domains to dominant negative versions of the UPR transcription factors can permit small molecule-dependent inhibition of endogenous transcription factor activity (Shoulders et al. 2013a). The advantages of destabilized domains for conferring small molecule control onto UPR and other stress-responsive transcription factors (Moore et al. 2016) have led to their adoption by a number of research groups in studies of stress-responsive signaling.

Chemical genetic strategies provide valuable temporal and ligand concentration-dependent control of UPR arm activity. However, they must be applied with caution to ensure that engineered domains are compatible with the natural function of the target protein. IRE1I624G, for example, does not share the same mechanism of activation as wild-type IRE1, and may exhibit altered kinase activity; similarly, the fusion of destabilized domains to UPR transcription factors may alter their function. Expression levels of engineered proteins, whether dictated by the leakiness of the system or by copy number per cell, must also be optimized. Thus, while such strategies have enabled substantial progress in the UPR field (especially with regard to potential therapeutic benefits of UPR activation in disease model systems, discussed below), they do not ablate the need for highly selective and potent small molecule UPR modulators that function independently of protein misfolding stress.

3.3. Activating the UPR to Address Diseases Linked to Dysregulated ER Proteostasis

Small molecule and chemical genetic methods to modulate the UPR, including those described above, have been extensively applied to test whether UPR-mediated remodeling of the ER proteostasis network is a viable strategy to address ER protein misfolding- and aggregation-related diseases. In particular, various approaches have been used to address dysregulated proteostasis associated with the three types of defects highlighted in Figure 3.

In the first category of pathologic ER proteostasis defects, protein misfolding/aggregation diseases manifest owing to a combination of underactive quality control and insufficient folding activity (Figure 3b). The insufficient ER proteostasis environments that characterize such disorders stem from the inability to sense misfolding of an individual mutant protein and/or the permitted secretion of malformed, aggregration-prone proteins into the extracellular milieu.

One example of underactive quality control is the transthyretin (TTR) amyloidoses, wherein misfolded or unstable TTR escapes the ER and later aggregates in peripheral tissues (Johnson et al. 2012). TTR is a secreted tetrameric protein whose extracellular disassembly provides the necessary template for oligomers to form (Hammarstrom et al. 2001; Hammarstrom et al. 2003). Numerous mutations destabilize the tetramer, accelerating disassembly, aggregation, and disease pathology. Two treatments currently exist: (1) gene therapy via liver transplantation, as the liver is the primary source of TTR, and (2) small molecule pharmacologic chaperones that stabilize secreted TTR tetramers and thereby prevent oligomerization (Johnson et al. 2012).

An alternative potentially synergistic possibility is enhancing the stringency of ER quality control, perhaps via UPR-mediated remodeling of the ER proteostasis network to reduce the secretion and promote the degradation of destabilized TTR variants. By lowering misfolding TTR concentrations in the sera, this strategy would likely reduce pathologic oligomer formation. Indeed, stress-independent activation of ATF6 using the chemical genetic DHFR.ATF6f construct (Section 3.2) preferentially directs destabilized TTR variants towards ERAD, drastically reducing their secretion (Chen et al. 2014a; Shoulders et al. 2013b). Importantly, the approach does not influence the secretion of stable, wild-type TTR. These results hint at the potential of stress-independent UPR activation to improve cellular capacity to prevent the secretion of misfolded, potentially toxic species. Stress-independent XBP1s and/or ATF6 activation is also effective in preventing the secretion of amyloidogenic light chain (Cooley et al. 2014). Such findings motivated significant efforts to identify small molecule activators of ATF6 that appear very promising and may provide leads for clinical development (Plate et al. 2016).

A second, less intuitive category of ER proteostasis defects arises when cells execute an overly stringent survey of client protein folding status (Figure 3c). As in cases of healthy proteostasis, aggregation is minimized, but a slow-folding or moderately misfolded ER client is prematurely directed to degradation when, if given sufficient time or assistance, it could have adopted a sufficiently folded, functional state to avert pathology. Such indiscriminate degradation owing to excessively stringent quality control results in loss-of-function phenotypes. Onset of disease occurs when the amount of protein present and able to function in its natural location falls below the required threshold of essential biological activity. Relaxed quality control may, in these cases, allow such ER clients to adopt sufficiently folded, functional states to traffic to their destinations and thereby ameliorate disease.

One case where hyperactive quality control appears to be associated with pathology is the lysosomal storage diseases. An example is Gaucher’s disease, which is caused by mutations that destabilize glucocerebrosidase (GCase). GCase is a hydrolytic enzyme that folds in the ER and is then trafficked to the lysosome, where it degrades encapsulated glycolipids. Misfolding-prone and destabilized GCase variants can be identified by overly stringent ER quality control machinery and targeted for degradation by the proteasome (Ron and Horowitz 2005). Even a slight improvement in trafficking to the lysosome would likely provide therapeutic benefit. Mu and coworkers discovered that global UPR activation by induction of mild ER stress significantly enhances trafficking of the L444P GCase variant to the lysosome in an IRE1- and PERK-dependent manner, with a corresponding decrease in degradation (Mu et al. 2008b). The resulting enhancement in lysosomal GCase activity can be synergistically enhanced by co-administration of GCase-stabilizing pharmacologic chaperones. More recently, both modulation of Ca2+ concentrations in the ER and knockdown of specific ER proteostasis network components like FKBP10 and ERdj3, which direct GCase to degradation, were shown to provide similar benefits (Mu et al. 2008a; Ong et al. 2010; Ong et al. 2013; Tan et al. 2014). Thus, reducing quality control stringency via UPR-mediated and/or more targeted perturbations of the ER proteostasis network may hold potential for diseases associated with hyperactive quality control.

A third category of disease-causing ER proteostasis defects emerges when protein misfolding or aggregation in the ER causes chronically unresolved stress and consequent cellular dysfunction. While the IRE1 and ATF6 arms of the UPR can help cells tolerate such chronic stress, as has been observed in fly models of retinal degeneration (Ryoo et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2007), chronic activation of the PERK arm leads directly to apoptosis. Thus, long-term UPR activation can severely threaten tissue homeostasis (Figure 3d), engendering a vicious cycle in which protein misfolding caused by mutations, aging, and the like results in cell death, increasing the demand on surviving cells in a given tissue to produce folded, functional protein. The increased protein-folding load placed on the surviving cells results in additional chronic ER stress, UPR activation, and further tissue loss. Unresolved chronic ER stress is associated with a wide variety of disorders and diseases, including obesity and neurodegeneration (Lindholm et al. 2006). Strategies to inhibit UPR-mediated apoptosis could be valuable in these situations, as could methods to alleviate chronic stress by enhancing folding or quality control (as in Figures 3b and 3c).

UPR-mediated ER proteostasis network remodeling has shown promise for several diseases where aggregation is observed in the ER. For example, ATF6 and PERK activation enhance clearance of mutant, aggregating rhodopsin variants that cause retinitis pigmentosa (Chiang et al. 2012). Similarly, ATF6 activation assists the clearance of the aggregating Z variant of α-1-antitrypsin that normally causes inflammation-induced hepatotoxicity (by a gain-of-function mechanism) and/or proteolytic damage to lung tissue (by a loss-of-function mechanism) (Smith et al. 2011b). Clearance of these protein aggregates from the ER is thus an attractive therapeutic strategy. An alternative approach, instead of activating UPR arms, is to simply lower the net protein load on the ER and allow endogenous mechanisms to resolve the proteostasis defect. This strategy involves application of molecules that function downstream of PERK to translationally attenuate the protein folding challenge faced by the ER. Related strategies have shown promise in both diabetes- and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-related model systems (Boyce et al. 2005; Das et al. 2015; Tsaytler et al. 2011).

While the division of disease-causing ER proteostasis defects into the three categories in Figures 3b–d provides valuable context, few diseases fit seamlessly. For example, lax quality control that permits excessive accumulation of mutant GCase variants may cause chronic, damaging ER stress and/or disrupt general protein trafficking mechanisms, a mechanism that could well be biologically relevant for Gaucher’s disease. Intriguingly, GCase deficiency promotes neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease, possibly through the loss of stabilizing effects on α-synuclein oligomers or by inducing lysosome dysfunction, providing further evidence that multiple shared mechanisms may underlie and connect otherwise disparate pathologies (Abeliovich and Gitler 2016). Another pertinent example is the collagenopathies such as osteogenesis imperfecta (Forlino and Marini 2016), which appear to encompass all three types of ER proteostasis defects described above. Collagen is a challenging protein to fold (DiChiara et al. 2016), with both globular and triple-helical regions, abundant and critical post-translational modifications, and dimensions too large for standard COP-II transport vesicles. Numerous mutations in collagen strands and in components of the collagen proteostasis network cause diverse collagenopathies, depending on the specific type of collagen involved. Mutations can lead to intracellular collagen accumulation and chronic ER stress, can cause collagen strands to be subjected to excessive quality control and degradation, and/or produce variants that functionally disrupt tissue architecture (Fitzgerald et al. 1999; Mirigian et al. 2016). Whether ER proteostasis imbalances can be remedied in osteogenesis imperfecta and the other collagenopathies remains to be determined, but such pathologies do highlight the complexity associated with many protein misfolding-related diseases.

3.4 Concept Summary

Directly targeting particular arms of the UPR via stress-dependent and -independent approaches will require minimizing off-target effects and separating overlapping activities, whether this entails uncoupling an apoptotic, late-stage UPR from a stress-sensing, early-stage UPR, uncoupling IRE1 kinase from RNase activity, or uncoupling UPR activation from ER stress. While the development of improved methods continues, the application of existing tools to various model systems confirms the therapeutic potential of adapting secretory proteostasis through the UPR. Although the details of the energy landscapes of misfolding and aggregation-prone proteins are unique, we note that they often share features in terms of their interactions with the ER proteostasis network. Focusing on commonalities may thus yield broadly applicable rather than disease-specific therapeutic approaches.

4. Beyond the UPR

The preceding discussion emphasizes the substantial promise of UPR modulation to resolve disease-causing ER proteostasis defects. However, global remodeling of the ER proteostasis network by UPR perturbation could have deleterious effects on wild-type, well-behaved proteins or on innate functions of the UPR. Targeted drug delivery to diseased tissues could help sidestep off-target effects, but remains difficult. Alternatively, although the UPR is the master regulator of the ER proteostasis network (Figure 2), it is still just one of many hubs (Figure 4). In many cases, it may be possible to design small molecules that target proteostasis nodes downstream of the UPR’s transcription/translation response to resolve proteostasis defects. Such approaches could have a larger therapeutic window owing to more precise manipulation of specific mechanisms. Testing these strategies requires selective chemical biology and genetic tools to manipulate the activities of chaperones, quality control pathways, and the like. In addition to the example of translational attenuation discussed above, this section briefly considers two other nodes downstream of the UPR where targeted investigation has become increasingly possible: the ER’s ATP-dependent chaperones and ERAD-mediated quality control.

Figure 4. Targeting functional nodes in the ER proteostasis network.

Representative hubs in the ER proteostasis network; colored boxes give a qualitative measure of methods available to modulate each node. Red: few and/or poorly characterized tools; blue: many and/or well-characterized tools. Nodes from Fig. 2 are aligned with the broader axes of quality control, folding, degradation, and secretion. For many diseases, coordinated regulation of multiple nodes in one or more of the relevant pathways may produce the most therapeutic benefit.

4.1 Targeting ATP-Dependent Chaperone Systems in the ER

The ATP-dependent chaperones Grp94 (a heat shock protein 90, or Hsp90, isoform), BiP (a heat shock protein 70, or Hsp70, isoform) and their corresponding Hsp40-like co-chaperones and nucleotide exchange factors are central components of the ER proteostasis network (Figure 2). They play key roles both in assisting client protein folding and in recognizing and targeting misfolded proteins for quality control. Given the importance of dysregulated proteostasis in cancer and other diseases, Hsp90 inhibitors have been particularly sought after as therapeutics. A number of potent inhibitors have been discovered (McCleese et al. 2009; Schulte and Neckers 1998; Shi et al. 2012; Whitesell et al. 1994) and show promise in cancer model systems. However, the high sequence and structural similarity of Hsp90 isoforms (Chen et al. 2005) poses difficulties for the design of selective small molecule inhibitors. Indeed, the most widely used Hsp90 inhibitors target multiple Hsp90 isoforms. Such promiscuity remains a significant challenge, even among compounds reported to be selective for the ER-resident isoform Grp94 (Liu and Street 2016). Particularly with respect to ER proteostasis, development of selective Grp94 inhibitors is essential to reduce undesirable cytotoxicity and ensure that only the intended proteostasis network nodeis targeted.

Fortunately, the ATP binding pocket of Grp94 is the most distinctive amongst the Hsp90 chaperone isoforms (Soldano et al. 2003), and recent progress in developing chemical tools for targeting Grp94 is encouraging. Rigorous structure-based analyses revealed that certain members of the purine-scaffold series bind a Grp94-specific hydrophobic pocket, permitting functional characterization of the effects of Grp94 inhibition in cancer cells (Patel et al. 2013). Other compound classes also show substantial promise, including radamide derivatives like BnIm, the first Grp94-selective inhibitor discovered (Duerfeldt et al. 2012). Improvements on BnIm have yielded even more potent Grp94 inhibitors (Crowley et al. 2016). As such chemical tools have become available, various groups have begun to test the consequences of Grp94 inhibition in protein misfolding-related disease model systems. For example, BnIm-mediated Grp94 inhibition ameliorates excessive quality control of the Ala322Asp variant of GABAA receptors, whose insufficient trafficking is associated with specific forms of epilepsy (Di et al. 2016). Such results are reminiscent of the ability of UPR activation to reduce excessive quality control of GCase (Mu et al. 2008b). Here, however, targeting an ER proteostasis node downstream of the UPR offers a more specific biological response.

Selective inhibition of the ER’s Hsp70 analogue BiP has proven more challenging. Eukaryotes express as many as thirteen Hsp70 isoforms (Kampinga et al. 2009), including BiP in the ER, mtHsp70 in mitochondria, the constitutive cytosolic Hsc70, and the inducible cytosolic isoform Hsp72. Moreover, BiP association with IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 regulates UPR signaling, making it difficult to target the chaperone without also inducing the UPR (Carrara et al. 2015; Pincus et al. 2010). While a few small molecules have been introduced as BiP inhibitors, it is not clear that they act selectively. Nonetheless, because BiP facilitates proper folding of nascent polypeptide chains, targets misfolded proteins for ERAD, and regulates ER stress signaling, selective modulation of BiP activities remains a promising avenue for resolving ER proteostasis defects. The identification of JG-98 as an inhibitor of the Bag3–Hsp72 interaction suggests that targeting protein–protein interactions of co-chaperones with BiP could be a viable alternative strategy for modulating BiP activity in the absence of small molecules that directly and selectively bind to BiP (Li et al. 2015; Li et al. 2013). The discovery that reversible AMPylation regulates BiP function may likewise yield new opportunities to target BiP activity with selective small molecules(Preissler et al. 2016).

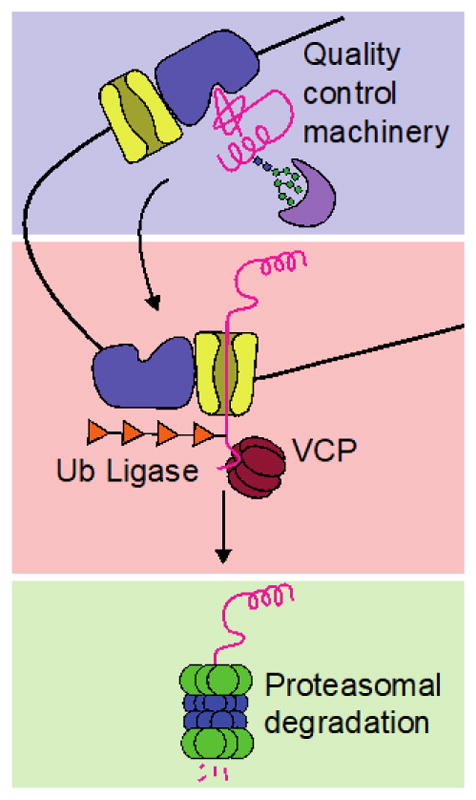

4.2. Targeting ERAD

Quality control mediated by ERAD is another proteostasis node downstream of the UPR where selective modulation offers substantial promise in disease. The process requires coordination of many different proteins in the ER lumen, lipid bilayer, and the cytosol in order to recognize, capture, transport, and degrade aberrant ER client proteins that pose a threat to cell health (Smith et al. 2011a). ERAD can be viewed as a three-step process, involving (1) selection/recognition of misfolded ER clients, (2) retrotranslocation to the cytosol, and (3) proteasomal degradation (Figure 5). The detailed mechanism involves intricate networks of chaperone–chaperone and chaperone–client interactions, as well as transport machines that we are only beginning to understand in biochemical detail (Christianson et al. 2011; Stein et al. 2014; Timms et al. 2016).

Figure 5. Advances in understanding and adapting ERAD.

Current methods primarily modulate ERAD by influencing transport and/or degradation of misfolded substrates (indicated by red and green boxes, respectively). Other promising targets for therapeutic intervention include the E3 ligase Hrd1 (blue box), which interacts with a broad range of protein substrates via its co-chaperones, and is involved in the selection of terminally misfolded ER clients for ERAD.

The selection/recognition step of ERAD has thus far proven challenging to target selectively, whereas substantial progress has been made in modulating retrotranslocation and degradation. For example, diverse and potent small molecules are available for proteasome inhibition (Kisselev et al. 2012). Targeting the proteasome has proven therapeutically valuable in multiple myeloma, where treatment with bortezomib or other inhibitors appears to enhance proteotoxic load in the ER, triggering stress-induced apoptosis (Obeng et al. 2006). However, proteasome inhibition can also be severely toxic for normal cells, and it disrupts protein recycling not just in the ER but also in other subcellular compartments.

The need for more selective modulators of ERAD prompted the search for inhibitors of ER retrotranslocation, and specifically for inhibitors of VCP/p97. VCP/p97 is an ATPase that assists in the extraction of misfolded proteins from the ER for proteasomal degradation, and also participates in other biological processes via its “segregase” activity (Meyer et al. 2012; Rabinovich et al. 2002). A number of VCP inhibitors have been identified via high-throughput screening and optimization efforts, ranging from the promiscuous first-generation compound Eeyarestatin I (Fiebiger et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2008), to more potent second-generation inhibitors like DBeQ (Chou et al. 2011) and the allosteric inhibitor NMS-873 (Magnaghi et al. 2013). Rigorous biophysical characterization of compound selectivity and mechanism of action, including the recent determination of a cryo-EM structure of a VCP-inhibitor complex, will continue to guide inhibitor optimization (Banerjee et al. 2016). Meanwhile, application of existing inhibitors has begun to reveal the potential of VCP inhibition to reduce excessive quality control of misfolding ER client proteins in a manner that is considerably more selective than proteasome inhibition (Han et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2011).

The promising results obtained by perturbing ER proteostasis network nodes downstream of the UPR motivate extensive further investigation in this area. As highlighted in Figure 4, we still lack small molecule tools to modulate many of these nodes. The emergence of such tools will open new opportunities for mechanistic studies and disease therapies. In the meantime, Cas9-based methods for transcriptional regulation of individual proteostasis network components in a highly selective, small molecule dose-dependent manner (Maji et al. 2017) should assist the prioritization of nodes for future method development. The continued advance of high-throughput genetic screening, as recently outlined in two reports that combine CRISPR technology with single cell RNA-seq, also provides opportunities for identifying new targets (Dixit et al. 2016; Adamson et al. 2016).

4.3 Concept Summary

Advances in targeting Hsp90 and ERAD exemplify how much fruitful ground lies beyond IRE1, ATF6, and PERK. Proteomic and high-throughput genetic screening approaches constitute a critical first step in identifying relevant nodes for specific diseases. Where key downstream nodes are known, the next task is to develop tools and modulators of sufficient potency for mechanistic work and drug development. As is the case for Hsp90 and other abundant protein families, researchers must not only identify what isoform is important for a particular process, but also whether and how the relevant isoform can be targeted. Due to high sequence and structural similarities between isoforms, this second question will likely continue to be a significant hurdle to modulating nodes downstream of the UPR. However, recent progress in Grp94 and VCP inhibition offers hope that combined biophysical and biochemical approaches will yield similar advances for isoform-specific targeting of other ER proteostasis network components.

5. Conclusions

As the master regulator of proteostasis in the secretory pathway, the UPR plays critical roles in both health and disease. Various groups have demonstrated UPR participation in organ development and innate immunity; more recently, others have revealed alternate cellular mechanisms for resolving stress, whether in the form of newly-discovered extracellular chaperones, membrane expansion, or changes to the oxidative folding environment. The advent of diverse chemical and chemical genetic methods now allows researchers to more precisely control UPR arm activation and inhibition, opening new doors to study not only the fundamental biology of the UPR and the secretory pathway, but also the potential of UPR modulation for therapeutic intervention. When selecting from existing tools to modulate or perturb the UPR, researchers must balance specificity with how much engineering or deviation from the natural system is required. The development of improved compounds to target both the UPR and downstream secretory proteostasis network nodes remains an urgent need and, when realized, will surely yield significant new findings. As the field continues to progress, we anticipate not only the elucidation of new functions of the UPR and improved mechanistic understanding, but also the emergence of additional disease-modifying UPR-and ER -targeted therapeutic strategies.

References

- Abeliovich A, Gitler AD. Defects in trafficking bridge Parkinson’s disease pathology and genetics. Nature. 2016;539:207–216. doi: 10.1038/nature20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi Y, Yamamoto K, Okada T, Yoshida H, Harada A, Mori K, et al. ATF6 is a transcription factor specializing in the regulation of quality control proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Struct Funct. 2008;33:75–89. doi: 10.1247/csf.07044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson B, et al. A multiplexed single-cell CRISPR screening platform enables systematic dissection of the unfolded protein response. Cell. 2016;167:1867–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolph TE, et al. Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2013;503:272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature12599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi M. N-Linked protein glycosylation in the ER. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2430–2437. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SH, Lee K, Vink E, Kaufman RJ. Cytoplasmic IRE1α-mediated XBP1 mRNA splicing in the absence of nuclear processing and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18691–18706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaszynski LA, Chen LC, Maynard-Smith LA, Ooi AGL, Wandless TJ. A rapid, reversible, and tunable method to regulate protein function in living cells using synthetic small molecules. Cell. 2006;126:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, et al. 2.3 angstrom resolution cryo-EM structure of human p97 and mechanism of allosteric inhibition. Science. 2016;351:871–875. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernales S, McDonald KL, Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:2311–2324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce M, et al. A selective inhibitor of eIF2α dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science. 2005;307:935–939. doi: 10.1126/science.1101902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, Till JH, Hubbard SR, Harding HP, Clark SG, Ron D. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrara M, Prischi F, Nowak PR, Kopp MC, Ali MM. Noncanonical binding of BiP ATPase domain to Ire1 and Perk is dissociated by unfolded protein CH1 to initiate ER stress signaling. eLife. 2015;4:e03522. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Piel WH, Gui LM, Bruford E, Monteiro A. The HSP90 family of genes in the human genome: Insights into their divergence and evolution. Genomics. 2005;86:627–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Genereux JC, Qu S, Hulleman JD, Shoulders MD, Wiseman RL. ATF6 activation reduces the secretion and extracellular aggregation of destabilized variants of an amyloidogenic protein. Chem Biol. 2014a;21:1564–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, et al. XBP1 promotes triple-negative breast cancer by controlling the HIF1α pathway. Nature. 2014b;508:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang WC, Hiramatsu N, Messah C, Kroeger H, Lin JH. Selective activation of ATF6 and PERK endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling pathways prevent mutant rhodopsin accumulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:7159–7166. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JA, et al. The unfolded protein response element IRE1αsenses bacterial proteins invading the ER to activate RIG-I and innate immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:558–569. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Chou TF, et al. Reversible inhibitor of p97, DBeQ, impairs both ubiquitin-dependent and autophagic protein clearance pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4834–4839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JC, et al. Defining human ERAD networks through an integrative mapping strategy. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;14:93–105. doi: 10.1038/ncb2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho Dina S, et al. XBP1-independent IRE1 signaling is required for photoreceptor differentiation and rhabdomere morphogenesis in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2013;5:791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CB, Ryno LM, Plate L, Morgan GJ, Hulleman JD, Kelly JW, Wiseman RL. Unfolded protein response activation reduces secretion and extracellular aggregation of amyloidogenic immunoglobulin light chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:13046–13051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406050111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespillo-Casado A, Chambers JE, Fischer PM, Marciniak SJ, Ron D. PPP1R15A-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2αis unaffected by Sephin1 or Guanabenz. eLife. 2017:e26109. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross BCS, et al. The molecular basis for selective inhibition of unconventional mRNA splicing by an IRE1-binding small molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E869–E878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley VM, et al. Development of glucose regulated protein 94-selective inhibitors based on the BnIm and radamide scaffold. J Med Chem. 2016;59:3471–3488. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton RP, Lyons DB, Lomvardas S. Co-opting the unfolded protein response to elicit olfactory receptor feedback. Cell. 2013;155:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan H, Upton JP, Hagen A, Callahan J, Oakes SA, Papa FR. A kinase inhibitor activates the IRE1α RNase to confer cytoprotection against ER stress. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2008;365:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das I, et al. Preventing proteostasis diseases by selective inhibition of a phosphatase regulatory subunit. Science. 2015;348:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzel MS, et al. Hexosamine pathway metabolites enhance protein quality control and prolong life. Cell. 2014;156:1167–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewal MB, et al. XBP1s links the unfolded protein response to the molecular architecture of mature N-glycans. Chem Biol. 2015;22:1301–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di XJ, Wang YJ, Han DY, Fu YL, Duerfeldt AS, Blagg BS, Mu TW. Grp94 protein delivers γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors to Hrd1 protein-mediated endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:9526–9539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.705004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiChiara AS, Taylor RJ, Wong MY, Doan ND, Rosario AM, Shoulders MD. Mapping and exploring the collagen-I proteostasis network. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:1408–1421. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b01083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit A, et al. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting molecular circuits with scalable single-cell RNA profiling of pooled genetic screens. Cell. 2016;167:1853–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerfeldt AS, et al. Development of a Grp94 inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9796–9804. doi: 10.1021/ja303477g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebiger E, Hirsch C, Vyas JM, Gordon E, Ploegh HL, Tortorella D. Dissection of the dislocation pathway for type I membrane proteins with a new small molecule inhibitor, eeyarestatin. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1635–1646. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J, Lamande SR, Bateman JF. Proteasomal degradation of unassembled mutant type I collagen pro-α1(I) chains. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27392–27398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlino A, Marini JC. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet. 2016;387:1657–1671. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00728-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S, et al. Aberrant lipid metabolism disrupts calcium homeostasis causing liver endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity. Nature. 2011;473:528–531. doi: 10.1038/nature09968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F, et al. Translocon component Sec62 acts in endoplasmic reticulum turnover during stress recovery. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:1173–1184. doi: 10.1038/ncb3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher CM, Walter P. Ceapins inhibit ATF6α signaling by selectively preventing transport of ATF6α to the Golgi apparatus during ER stress. eLife. 2016;5:e11880. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JN, Gifford NM, Brewer JW. Activation of an unfolded protein response during differentiation of antibody-secreting B cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49047–49054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genereux JC, et al. Unfolded protein response-induced ERdj3 secretion links ER stress to extracellular proteostasis. EMBO J. 2015;34:4–19. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershenson A, Gierasch LM, Pastore A, Radford SE. Energy landscapes of functional proteins are inherently risky. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:884–891. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R, et al. Allosteric inhibition of the IRE1α RNase preserves cell viability and function during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell. 2014;158:534–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstrom P, Schneider F, Kelly JW. Trans-suppression of misfolding in an amyloid disease. Science. 2001;293:2459–2462. doi: 10.1126/science.1062245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstrom P, Wiseman RL, Powers ET, Kelly JW. Prevention of transthyretin amyloid disease by changing protein misfolding energetics. Science. 2003;299:713–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1079589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D, et al. IRE1α kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell. 2009;138:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DY, Di XJ, Fu YL, Mu TW. Combining valosin-containing protein (VCP) inhibition and suberanilohydroxamic acid (SAHA) treatment additively enhances the folding, trafficking, and function of epilepsy-associated gamma-aminobutyric acid, type A (GABA(A)) receptors. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:325–337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.580324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek R, Schapira M, Ron D. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan IH, et al. Influenza A viral replication is blocked by inhibition of the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) stress pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4679–4689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.284695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempstead AD, Isberg RR. Inhibition of host cell translation elongation by Legionella pneumophila blocks the host cell unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E6790–6797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508716112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N, Walter P, Weissman JS. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto M, Björklund T, Lundberg C, Kirik D, Wandless TJ. A general chemical method to regulate protein stability in the mammalian central nervous system. Chem Biol. 2010;17:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamora C, Dennert G, Lee AS. Inhibition of tumor progression by suppression of stress protein GRP78/BiP induction in fibrosarcoma B/C10ME. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7690–7694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Connelly S, Fearns C, Powers ET, Kelly JW. The transthyretin amyloidoses: From delineating the molecular mechanism of aggregation linked to pathology to a regulatory agency-approved drug. J Mol Biol. 2012;421:185–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampinga HH, et al. Guidelines for the nomenclature of the human heat shock proteins. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaminets A, et al. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum turnover by selective autophagy. Nature. 2015;522:354–358. doi: 10.1038/nature14498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisselev AF, van der Linden WA, Overkleeft HS. Proteasome inhibitors: An expanding army attacking a unique target. Chem Biol. 2012;19:99–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono N, Amin-Wetzel N, Ron D. Generic membrane spanning features endow IRE1α with responsiveness to membrane aberrancy. Mol Biol Cell. 2017 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-03-0144. mbc E17-03-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguesse S, et al. A dynamic unfolded protein response contributes to the control of cortical neurogenesis. Dev Cell. 2015;35:553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, et al. Validation of the Hsp70-Bag3 protein-protein interaction as a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:642–648. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, et al. Analogues of the allosteric heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) inhibitor, MKT-077, as anti-cancer agents. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:1042–1047. doi: 10.1021/ml400204n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JH, Li H, Zhang YH, Ron D, Walter P. Divergent Effects of PERK and IRE1 Signaling on Cell Viability. PLoS One. 2009;4:e0004170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm D, Wootz H, Korhonen L. ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:385–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Street TO. 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine is not a paralog-specific Hsp90 inhibitor. Protein Sci. 2016;25:2209–2215. doi: 10.1002/pro.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PD, et al. Cytoprotection by pre-emptive conditional phosphorylation of translation initiation factor 2. EMBO J. 2004;23:169–179. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi P, et al. Covalent and allosteric inhibitors of the ATPase VCP/p97 induce cancer cell death. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:548–U544. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maji B, Moore CL, Zetsche B, Volz SE, Zhang F, Shoulders MD, Choudhary A. Multidimensional chemical control of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:9–11. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress: a vicious cycle or a double-edged sword? Antiox. Redox Signal. 2007;9:2277–2293. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margariti A, et al. XBP1 mRNA splicing triggers an autophagic response in endothelial cells through BECLIN-1 transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:859–872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.412783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Chen X, Lee AH, Glimcher LH. TLR activation of the transcription factor XBP1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:411–418. doi: 10.1038/ni.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleese JK, et al. The novel HSP90 inhibitor STA1474 exhibits biologic activity against osteosarcoma cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2792–2801. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez AS, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-independent activation of unfolded protein response kinases by a small molecule ATP-mimic. eLife. 2015;4:e05434. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer H, Bug M, Bremer S. Emerging functions of the VCP/p97 AAA-ATPase in the ubiquitin system. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:117–123. doi: 10.1038/ncb2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura N, et al. Blockade of XBP1 splicing by inhibition of IRE1 alpha is a promising therapeutic option in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:5772–5781. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-366633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirigian LS, et al. Osteoblast malfunction caused by cell stress response to procollagen misfolding in α2(I)-G610C mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:1608–1616. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CL, Dewal MB, Nekongo EE, Santiago S, Lu NB, Levine SS, Shoulders MD. Transportable, chemical genetic methodology for the small molecule-mediated inhibition of heat shock factor 1. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:200–210. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K, Hollien J. IRE1-mediated decay in mammalian cells relies on mRNA sequence, structure, and translational status. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:2873–2884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-02-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu T-W, Fowler DM, Kelly JW. Partial restoration of mutant enzyme homeostasis in three distinct lysosomal storage disease cell lines by altering calcium homeostasis. PLoS Biol. 2008a;6:e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu TW, Ong DS, Wang YJ, Balch WE, Yates JR, 3rd, Segatori L, Kelly JW. Chemical and biological approaches synergize to ameliorate protein-folding diseases. Cell. 2008b;134:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeng EA, Carlson LM, Gutman DM, Harrington WJ, Lee KP, Boise LH. Proteasome inhibitors induce a terminal unfolded protein response in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107:4907–4916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Yoshida H, Akazawa R, Negishi M, Mori K. Distinct roles of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) in transcription during the mammalian unfolded protein response. Biochem J. 2002;366:585–594. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong DS, Mu TW, Palmer AE, Kelly JW. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ increases enhance mutant glucocerebrosidase proteostasis. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:424–432. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong DS, Wang YJ, Tan YL, Yates JR, 3rd, Mu TW, Kelly JW. FKBP10 depletion enhances glucocerebrosidase proteostasis in Gaucher disease fibroblasts. Chem Biol. 2013;20:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa FR, Zhang C, Shokat K, Walter P. Bypassing a kinase activity with an ATP-competitive drug. Science. 2003;302:1533–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1090031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel PD, et al. Paralog-selective Hsp90 inhibitors define tumor-specific regulation of HER2. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:677–684. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus D, Chevalier MW, Aragon T, van Anken E, Vidal SE, El-Samad H, Walter P. BiP binding to the ER-stress sensor Ire1 tunes the homeostatic behavior of the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plate L, et al. Small molecule proteostasis regulators that reprogram the ER to reduce extracellular protein aggregation. eLife. 2016;5:e15550. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preissler S, Rato C, Perera LA, Saudek V, Ron D. FICD acts bifunctionally to AMPylate and de-AMPylate the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone BiP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;24:23–29. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich E, Kerem A, Frohlich KU, Diamant N, Bar-Nun S. AAA-ATPase p97/Cdc48p, a cytosolic chaperone required for endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:626–634. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.626-634.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina K, Noblin DJ, Serebrenik YV, Adams A, Zhao C, Crews CM. Targeted protein destabilization reveals an estrogen-mediated ER stress response. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:957–962. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimold AM, et al. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412:300–307. doi: 10.1038/35085509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson CE, Kooistra T, Kim DH. An essential role for XBP-1 in host protection against immune activation in C. elegans. Nature. 2010;463:1092–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature08762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron I, Horowitz M. ER retention and degradation as the molecular basis underlying Gaucher disease heterogeneity. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2387–2398. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy CR, Salcedo SP, Gorvel JP. Pathogen-endoplasmic-reticulum interactions: in through the out door. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:136–147. doi: 10.1038/nri1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Canada C, Kelleher DJ, Gilmore R. Cotranslational and posttranslational N-glycosylation of polypeptides by distinct mammalian OST isoforms. Cell. 2009;136:272–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski DT, et al. Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo HD, Domingos PM, Kang MJ, Steller H. Unfolded protein response in a Drosophila model for retinal degeneration. EMBO J. 2007;26:242–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck S, Prinz WA, Thorn KS, Voss C, Walter P. Membrane expansion alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress independently of the unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:525–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte TW, Neckers LM. The benzoquinone ansamycin 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin binds to HSP90 and shares important biologic activities with geldanamycin. Cancer Chemo Pharm. 1998;42:273–279. doi: 10.1007/s002800050817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer AL, et al. XBP1, downstream of blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2004;21:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, et al. Complementary signaling pathways regulate the unfolded protein response and are required for C. elegans development. Cell. 2001;107:893–903. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, et al. EC144 is a potent inhibitor of the heat shock protein 90. J Med Chem. 2012;55:7786–7795. doi: 10.1021/jm300810x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoulders MD, Ryno LM, Cooley CB, Kelly JW, Wiseman RL. Broadly applicable methodology for the rapid and dosable small molecule-mediated regulation of transcription factors in human cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2013a;135:8129–8132. doi: 10.1021/ja402756p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoulders MD, et al. Stress-independent activation of XBP1s and/or ATF6 reveals three functionally diverse ER proteostasis environments. Cell Rep. 2013b;3:1279–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrauski C, McGeachy AM, Ingolia NT, Walter P. The small molecule ISRIB reverses the effects of eIF2αphosphorylation on translation and stress granule assembly. eLife. 2015;4:e05033. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MH, Ploegh HL, Weissman JS. Road to ruin: Targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2011a;334:1086–1090. doi: 10.1126/science.1209235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SE, Granell S, Salcedo-Sicilia L, Baldini G, Egea G, Teckman JH, Baldini G. Activating transcription factor 6 limits intracellular accumulation of mutant α1-antitrypsin Z and mitochondrial damage in hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2011b;286:41563–41577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldano KL, Jivan A, Nicchitta CV, Gewirth DT. Structure of the N-terminal domain of GRP94 - Basis for ligand specificity and regulation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48330–48338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Ruggiano A, Carvalho P, Rapoport TA. Key steps in ERAD of luminal ER proteins reconstituted with purified components. Cell. 2014;158:1375–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan YL, Genereux JC, Pankow S, Aerts JM, Yates JR, 3rd, Kelly JW. ERdj3 is an endoplasmic reticulum degradation factor for mutant glucocerebrosidase variants linked to Gaucher’s disease. Chem Biol. 2014;21:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RC, Dillin A. XBP-1 is a cell-nonautonomous regulator of stress resistance and longevity. Cell. 2013;153:1435–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]