This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial evaluates the authors evaluate contact lens adherence and its association with visual outcome in a cohort of children treated for unilateral cataract surgery.

Key Points

Question

How successful is contact lens wear in children following unilateral cataract surgery during infancy if contact lenses are provided at no charge to caregivers?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial, most families reported that their child wore a contact lens more than 80% of waking hours from the time of cataract extraction through age 5 years.

Meaning

Adherence to wearing contact lenses provided at no charge is high through age 5 years by most caregivers of children with unilateral aphakia.

Abstract

Importance

Although contact lenses have been used for decades to optically correct eyes in children after cataract surgery, there has never been a prospective study looking at contact lens adherence in children with aphakia, to our knowledge.

Objective

To evaluate contact lens adherence and its association with visual outcome in a cohort of children treated for unilateral cataract surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of 57 infants born from August 22, 2004, to April 25, 2008, who were randomized to 1 of 2 treatments and followed up to age 5 years. Data analysis was performed from August 9, 2016, to December 7, 2017.

Interventions

Unilateral cataract extraction and randomization to implantation of an intraocular lens vs contact lens to correct aphakia.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Contact lens adherence was assessed by a 48-hour recall telephone interview that was administered every 3 months starting 3 months after surgery to age 5 years. A traveling examiner assessed visual acuity in patients at aged 4.5 years. Adherence to prescribed contact lens use was estimated as the mean percentage of waking hours as reported in 2 or more interviews for each year of life.

Results

Of 57 infants who were randomized to contact lens treatment, 32 (56%) were girls, and 49 (86%) were white. A total of 872 telephone interviews were completed. In year 1, a median of 95% participants wore their contacts lenses nearly all waking hours (interquartile range [IQR], 84%-100%); year 2, 93% (IQR, 85%-99%); year 3, 93% (IQR, 85%-99%); year 4, 93% (IQR, 75%-99%); and year 5, 89% (IQR, 71%-97%). There was a tendency for poorer reported adherence at older ages (F = 3.86, P < .001). No differences were identified when the results were analyzed by sex, insurance coverage, or age at cataract surgery. Using linear regression, children who wore the contact lens for a greater proportion of waking hours during the entire study period tended to have better visual acuity at age 4.5 years, even after accounting for adherence to patching (partial correlation = –0.026; P = .08).

Conclusions and Relevance

These results confirm that it is possible to achieve a high level of aphakic contact lens adherence over a 5-year period in children.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00212134

Introduction

The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS) was designed to compare visual outcomes in children who were aged 1 to 6 months at the time of unilateral congenital cataract surgery and were randomized to either optical correction with contact lenses or intraocular lenses. Children who were randomized to the aphakia group were treated with a contact lens. At age 4.5 years, about 20% of treated eyes had visual acuity of 20/32 or better, 30% had 20/40 to 20/100 acuity, and 50% had 20/200 or worse acuity. Visual results were comparable for optical correction with either a contact lens or an intraocular lens at age 1 and 4.5 years, but significantly more infants randomized to intraocular lens implantation required additional intraocular surgeries. Therefore, we recommended that the eyes of infants undergoing surgical procedures for a unilateral cataract during the first 6 months of life be left aphakic and be optically corrected with a contact lens.

Parental adherence to the treatment regimen of patching and visual correction with a contact lens or spectacles is believed to play an important role in the visual outcome of children with unilateral congenital cataracts. We have previously shown that adherence to patching is associated with visual acuity, and overall about 10% to 14% of the variation in visual acuity at age 4.5 years in the IATS could be attributed to patching adherence. In previous publications, we described the clinical findings for children who were randomized to contact lens wear. We now report contact lens adherence for the infants randomized to contact lens wear in the IATS.

Methods

The overall design of the IATS has been reported previously, and the full trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. The IATS is a multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing intraocular lens and contact lens treatment after unilateral congenital cataract surgery in children 6 months or younger who were born between August 22, 2004, and April 25, 2008. Data analysis was performed from August 9, 2016, to December 7, 2017. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of all the participating institutions and was in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian of all patients before randomization.

Contact Lens Correction

Within 1 week after cataract surgery, patients randomized to this group were fitted with either a silicone elastomer (Silsoft Super Plus; Bausch & Lomb) or gas permeable (X-cel Specialty Contacts) contact lens with a +2.00 diopter overcorrection to provide a near-point correction. The choice of the type of contact lens fitted was a shared decision between investigators and caregivers. The lens power was adjusted for infinity at approximately age 2 years along with spectacle overcorrection with a straight top bifocal with a +3.00 diopter add. Patients were evaluated by both the surgeon and the IATS certified contact lens professional at each study visit, and parameter changes were made as needed to optimize the power and fit of the lens. Contact lenses were supplied at no cost to caregivers. Whenever a contact lens was prescribed, 2 contact lenses were dispensed so that a spare contact lens would be available in the event that a lens was lost. A complete description of the fitting process, contact lens characteristics, and adverse events have been reported previously. IATS investigators were only allowed to implant a secondary intraocular lens in an aphakic eye if a child was deemed to be an unsuccessful contact lens trial by the IATS Executive Committee. A patient was considered to be an unsuccessful contact lens trial if they wore a contact lens for fewer than 4 hours per day on average for a period of 8 consecutive weeks. Contact lens use prior to secondary intraocular lens implantation was included in all analyses.

Evaluation of Adherence

Adherence to contact lens use was assessed using adherence interviews of the caregivers. The assessment of adherence was modeled after dietary assessments that have been used in a variety of epidemiologic studies, including in preschool-aged children.

For this study, adherence was evaluated using quarterly 48-hour recall telephone interviews. During the study period, interviews assessing patching and contact lens adherence were performed approximately every 3 months, starting 3 months after the surgical procedure. The timing of the interviews was determined using an algorithm that distributed the preferred day of the call evenly throughout the week.

The adherence interview was a 30-minute, semistructured telephone interview conducted in the primary caregiver’s preferred language (ie, English, Spanish, Portuguese) by study staff at the Data Coordinating Center to minimize any concerns that the caregiver might have about confidentiality of the interview. For each family, the staff member who interviewed the caregiver was the same. The adherence interview was designed to gain information about the proportion of time that the child wore the contact lens during the previous 48 hours while awake. The structure of the interviews used questions about the child’s activities, sleep and wake times, meal times, bath times, etc, as anchors to improve recall. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire for assessing adherence to patching have previously been described.

For the current analyses, we estimated the mean percentage of waking hours that each child wore their contact lens during 5 separate times: from surgery to age 11 months, from 12 to 23 months, from 24 to 35 months, from 36 to 47 months, and from 48 to 60 months because age may impact adherence to contact lens use. Additionally, we limited analyses within each time to participants who had completed at least 2 adherence interviews during the time window to minimize the impact of day-to-day variation in reported contact lens use. We also calculated an overall percentage of waking hours spent wearing the contact lens during the 5-year period as a mean of the percentage reported in each of the 5 times. This analysis was limited to children for whom adherence to contact lens use was reported in at least 2 interviews during at least 4 of the 5 times.

Patching Regimen

Caregivers were instructed to have their child wear an adhesive occlusive patch over the unoperated eye for 1 hour per day for each month of age until age 8 months. Thereafter, patching was prescribed for one-half of waking hours.

Visual Acuity Assessment

Monocular optotype acuity was assessed at age 4.5 years (+1 month) by a masked traveling examiner using the Amblyopia Treatment Study-HOTV test. Patients were tested wearing their best correction, which had been updated at their last study visit 3 months earlier. Visual acuity was tested first in the aphakic/pseudophakic eye. The eye not being tested was occluded.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS software (version 23; IBM). The overall mean percentage of waking hours spent wearing a contact lens was estimated using a normal distribution. Differences in mean adherence by age were assessed using repeated measures analyses of variance. Differences in mean adherence by other characteristics such as sex, the availability of private health insurance, and age at the time of surgery (≤48 days and >48 days) were assessed using repeated measures analyses of variance. Multiple linear regression was used to assess the relationship between percentage of waking hours patched and visual acuity. Additionally, as the distribution of means across the population was highly skewed, with most children wearing a contact lens nearly 100% of waking hours, we repeated analyses using nonparametric statistics.

Results

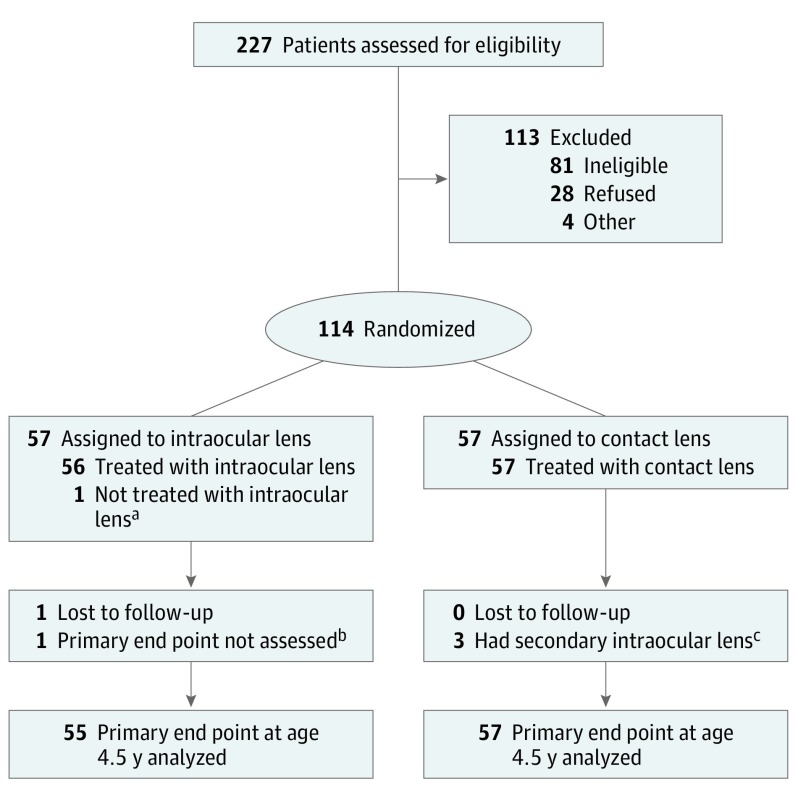

Of 114 patients enrolled in the study, 57 (50%) were randomized to contact lens treatment (Figure 1). The median age for the contact lens group at the time of cataract surgery was 1.8 months (interquartile range, 1.1-3.1 months); 32 (56%) were girls, and 49 (86%) were white. Two patients had nonamblyopic no light perception or light perception visual acuity shortly after surgery and did not receive optical correction and therefore were not included in the analysis. Three patients had secondary intraocular lenses implanted between age 1 and 5 years after being deemed unsuccessful contact lens trials. In all 3 cases, caregivers were unable to manage the application and removal of contact lenses in their child’s eye. All 3 patients wore silicone elastomer lenses only. Of the remaining 52 eyes in patients who wore contact lenses, 24 (46%) were treated with silicone elastomer lenses only, 11 (21%) were treated with gas permeable lenses only, and 17 (33%) used both lens types and/or soft contact lenses at various times. Of the 41 patients wearing silicone elastomer lenses between age 1 and 5 years, 28 (68.3%) wore a lens on a continuous wear schedule (7-21 nights); 6 (14.6%), on a daily wear basis; and 3 (7.3%), alternated between daily and continuous wear. The wear schedule was not documented for 4 patients. Children wearing a gas permeable lens wore the lens on a daily wear basis.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram for the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study.

aOne patient was found to have stretching of the ciliary processes intraoperatively after randomization to the intraocular lens group. The investigator decided that an intraocular lens could not be safely implanted, and the patient’s aphakia was treated with a contact lens.

bOne patient had developmental delay and could not complete the HOTV acuity test at age 4.5 years.

cTwo patients had a secondary intraocular lens implanted at age 1.3 and 3.0 years after randomization. A third patient had a secondary intraocular lens implanted at 4.7 years after randomization and after the primary end point was assessed but before the last clinical examination at age 5 years.

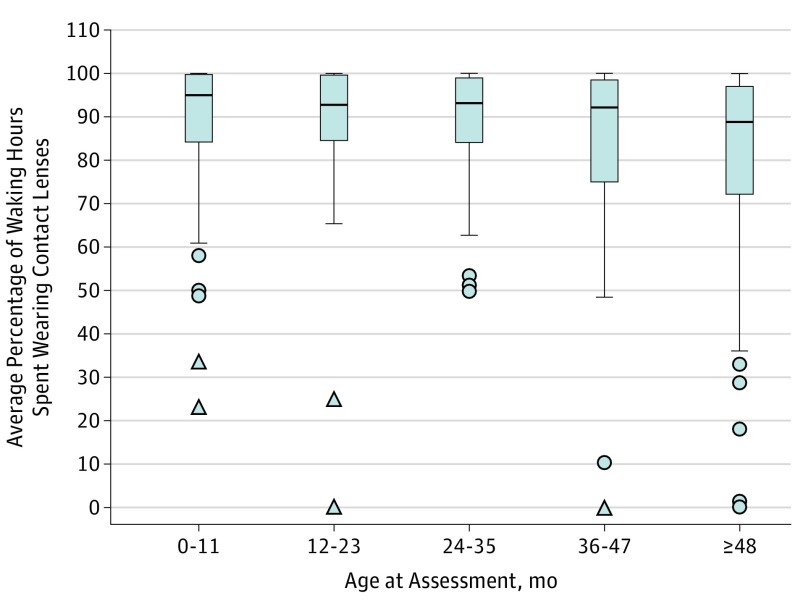

A total of 872 telephone interviews were completed for children randomized to the contact lens group. Prior to age 5 years, more than half of all children randomized to receive a contact lens wore the lens at least 90% of waking hours. In year 5, the median reported use was 89% of waking hours (Table). There was a tendency for poorer reported adherence at older ages (F = 3.86, P < .001 for repeated measures analysis of variance with Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment) (Figure 2). However, there were a number of individuals who reported wearing their contact lens for less than 90% of waking hours in 1 age group but in a later age group reported better adherence.

Table. Reported Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses From Ages 1 to 5 Years in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study .

| Age, mo | No. (%)a | Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Wore Contact Lens >80% of Waking Hours | Wore Contact Lens >90% of Waking Hours | ||

| <12 | 50 (90.9) | 87.6 (17.9) | 95.0 (83.7-99.8) | 40 (80.0) | 33 (66.0) |

| 12-24 | 52 (94.5) | 87.5 (18.4) | 92.8 (84.6-99.8) | 41 (78.9) | 33 (63.4) |

| 24-36 | 48 (87.2) | 85.6 (18.7) | 93.2 (80.9-99.5) | 37 (77.0) | 32 (66.7) |

| 36-48 | 48 (87.2) | 80.6 (27.5) | 92.2 (75.0-98.6) | 33 (68.8) | 29 (60.4) |

| >48 | 44 (80.0) | 76.0 (29.7) | 88.8 (70.7-97.1) | 28 (63.6) | 21 (47.7) |

| Overall | 47 (85.4)b | 85.6 (13.1) | 88.3 (81.9-94.1) | 38 (80.9) | 21 (44.7) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Number of participants who had completed at least 2 adherence interviews in the year.

Number of participants who had completed at least 2 adherence interviews in at least 4 of 5 years.

Figure 2. Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses by Age in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study.

The horizontal line in the middle of the box indicates median; the top and bottom borders of the boxes, 75th and 25th percentiles; the whiskers, 2 SD from the median; circles, outliers; and triangles, extreme outliers.

Additional analyses were performed to evaluate potential predictors of contact lens adherence, including sex, private insurance, and age at time of the surgical procedure. Using repeated-measures analysis of variance, there were no statistically significant differences in contact lens use by sex (F = 0.08, P = –0.72), insurance coverage (F = 0.012, P = .91), or age at cataract surgery (F = 0.07, P = .79) (eFigures 1 to 3 in Supplement 2).

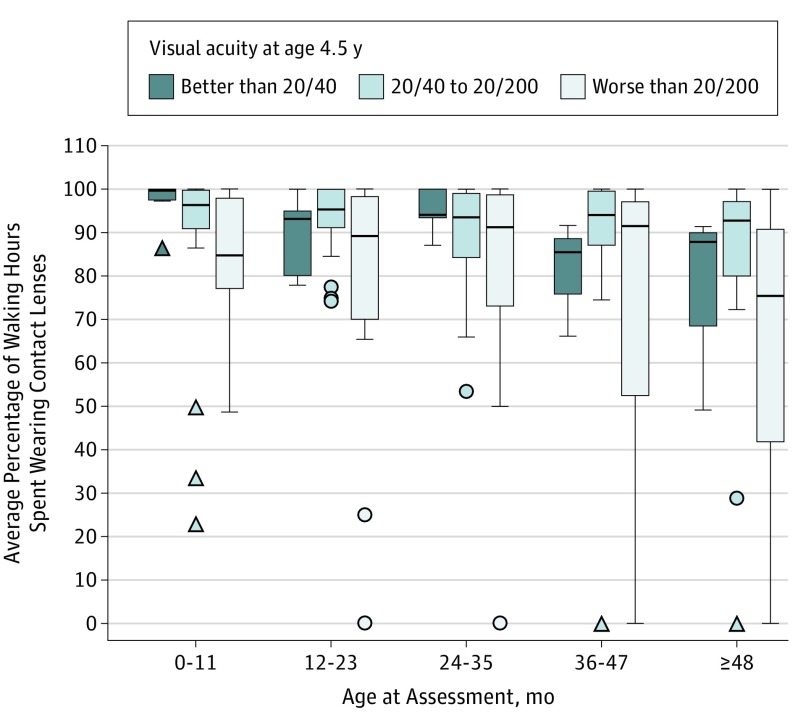

We evaluated the contact lens adherence in groups defined by the visual acuity outcome at age 4.5 years (20/32 or better, 20/40-20/200, or worse than 20/200) (Figure 3). In linear regression, a greater mean number of hours of contact lens use during the 5-year period tended to be associated with better visual acuity at age 4.5 years (partial correlation = –0.26; P = .08) even after accounting for the number of hours spent wearing an occlusive patch. Together, mean waking hours wearing the patch and mean percentage of waking time spent wearing a contact lens accounted for 12% of the variation in visual acuity.

Figure 3. Visual Acuity and Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses by Age in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study.

The horizontal line in the middle of the box indicates median; the top and bottom borders of the boxes, 75th and 25th percentiles; the whiskers, 2 SD from median; circles, outliers; and triangles, extreme outliers.

We also evaluated the relationship between reported patching and contact lens adherence. Children with more reported hours of patching also had a greater percentage of waking hours wearing a contact lens with Pearson correlation coefficients ranging from 0.16 between age 24 and 36 months (Pearson r = 0.13; P = .36) to 0.043 between age 48 and 60 months (Pearson r = 0.43; P < .01). The correlation was highest in the first year and after age 36 months. Although it is not surprising that patients with poor adherence to one form of therapy would be less adherent to another, this means that it may be difficult to separate the relationship between visual acuity and contact lens adherence from visual acuity and occlusion therapy adherence.

Discussion

We found that most families reported that their child wore a contact lens more than 80% of their waking hours from the time of cataract extraction through age 5 years. Only 3 children randomized to contact lens use stopped wearing them for adherence reasons.

We are unaware of any previous studies that have evaluated aphakic contact lens adherence in children after congenital cataract surgery. Most other studies evaluating contact lens use after congenital cataract surgery have been retrospective, to our knowledge. For example, Autrata et al reported the visual outcomes for 23 children who underwent unilateral congenital cataract surgical procedures, and their eyes were optically corrected with aphakic contact lenses, but they did not report contact lens adherence. Although the cohort study by Solebo et al was a prospective study, patients were not randomized to different optical treatments, and no contact lens adherence data have been published to date from this study.

We were unable to show a clear relationship between contact lens adherence and visual outcomes. There are a number of possible reasons for this. First, contact lens adherence was quite high in our series, and there may be only a small additional benefit to wearing a contact lens for all waking hours even in an aphakic eye. Second, there are likely many other factors that influenced visual outcomes in addition to contact lens adherence, including patching adherence, age at surgery, socioeconomic factors, and adverse events. Lastly, our sample size may have been too small to identify a significant relationship between contact lens adherence and visual outcomes.

In our study, 3 of 57 patients (6%) randomized to contact lens wear underwent secondary intraocular lens placement before age 5 years. In all 3 cases, it was because caregivers had difficulty applying and removing contact lenses rather than adverse events arising from wearing contact lenses. Most previous studies have reported a higher contact lens failure rate, to our knowledge. Mittelviefhaus et al reported 20 of 90 children (22%) discontinued contact lens wear after congenital cataract surgery: 12 with aphakia in 1 eye and 8 in both eyes. The most common reasons cited for discontinuing contact lens use included poor vision, parental noncompliance, and patient intolerance. Ozbek et al reported 5 of 51 children (10%) discontinued silicone elastomer contact lens wear after congenital cataract surgery. The reasons cited for doing so included the frequent loss of lenses or financial problems (n = 3) and recurrent irritation and corneal infiltrates (n = 2). Loudot et al reported that 3 of 17 children (17%) discontinued gas permeable contact lens use because their caregiver had problems manipulating the lenses. Amaya et al reported that 12 of 83 children (15%) discontinued hydrogel contact lens use because caregivers had difficulty handling the lenses, frequent lens loss, hypoxic corneal ulcerations, and caregiver preference for glasses. The hypoxic corneal ulcerations were likely related to the low oxygen transmissibility of hydrogel contact lenses in high plus powers. Finally, Aasuri et al reported that one-third of children with aphakia switched to glasses or had an intraocular lens implanted within 6 months of being fitted with silicone elastomer contact lenses. The high contact lens adherence rate in the IATS is likely due to many factors such as the lenses being provided at no cost to caregivers, quarterly telephone interviews assessing contact lens adherence, and participating surgeons only implanting secondary intraocular lenses if patients met strict contact lens failure criteria.

The cost of contact lenses is likely a significant factor affecting contact lens adherence for many children after congenital cataract surgery. Russell et al reported that on average, children in the IATS cohort required 11 silicone elastomer replacement lenses or 17 gas permeable replacement lenses from infancy to age 5 years. Kruger et al estimated that the cost of supplies (eg, contact lenses, spectacles, and patches) is twice as high for children randomized to aphakia and contact lens wear compared with primary intraocular lens implantation. Because the cost of these supplies is not covered by most public or private health insurance plans in the United States, this is a significant obstacle for many children wearing contact lenses on a long-term basis. This is 1 of the reasons cited for considering primary intraocular lens implantation during infancy despite the higher rate of adverse events and additional intraocular surgeries associated with intraocular lens implantation in this age group. The high success rate of contact lens wear following congenital cataract surgery in countries with socialized health care systems suggests that cost is an important factor when treating children with aphakic contact lenses. The IATS provides further evidence that when the economic burden of contact lens use is removed from caregivers, excellent contact lens adherence can be achieved. It is the opinion of the authors that both public and private health insurance should cover the cost of aphakic contact lenses for children, given their important role in the visual rehabilitation of these eyes after cataract surgery.

Limitations

There are a number of potential limitations to the current analyses, particularly the estimates of contact lens adherence. First, there may be substantial day-to-day variation in contact lens use. We attempted to minimize this concern by not having the caregiver informed ahead of time about the timing of the call, by averaging at least 3 adherence assessments, and by having adherence interviews conducted on both weekdays and weekends. Second, caregivers may overreport their adherence to prescribed contact lens use. Further, the specific instrument that we used to assess adherence has not been externally validated. However, errors in the percentage of waking hours spent wearing contact lenses is unlikely to have a substantial impact on our findings, particularly because more than 50% of the children wore contact lenses on an extended-wear basis. Additionally, by having the interviews completed by the same person each time and by ensuring that the interview was not associated with clinical care, we attempted to minimize the risk of caregivers exaggerating contact lens use stemming from a social desirability bias. Although it would be preferable to have objective measures of contact lens adherence, at this point, no such devices are available. Furthermore, we have previously shown that reported adherence to prescribed occlusion therapy in this population is similar to that reported for similar populations using occlusion dose monitors. Finally, patching adherence may be a confounding variable for contact lens adherence because we have shown that they correlate closely with one another. A key concern, however, is that the provision of contact lenses to participants’ families may reduce financial barriers to contact lens use. Therefore, contact lens use in other contexts may not be as high as we report here.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that most caregivers were able to manage contact lens application and removal and achieve high levels of adherence to full-time contact lens wear for their child. We also found that there was no significant effect of sex, private insurance as an indicator of socioeconomic status, or age at time of surgery on contact lens adherence.

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Reported Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses from Age 1 to 5 Years vs Sex in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study

eFigure 2. Reported Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses From Age 1 to 5 Years as a Function of Private vs Public Health Insurance in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study

eFigure 3. Reported Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses From Age 1 to 5 Years vs Age at Cataract Surgery (<49 days vs 49 days or older) in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study

References

- 1.Lambert SR, Buckley EG, Drews-Botsch C, et al. ; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study: design and clinical measures at enrollment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):21-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert SR, Lynn MJ, Hartmann EE, et al. ; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . Comparison of contact lens and intraocular lens correction of monocular aphakia during infancy: a randomized clinical trial of HOTV optotype acuity at age 4.5 years and clinical findings at age 5 years. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(6):676-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert SR, Buckley EG, Drews-Botsch C, et al. ; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . A randomized clinical trial comparing contact lens with intraocular lens correction of monocular aphakia during infancy: grating acuity and adverse events at age 1 year. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(7):810-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plager DA, Lynn MJ, Buckley EG, Wilson ME, Lambert SR; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . Complications in the first 5 years following cataract surgery in infants with and without intraocular lens implantation in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(5):892-898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birch EE, Stager DR. Prevalence of good visual acuity following surgery for congenital unilateral cataract. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(1):40-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drews-Botsch C, Celano M, Cotsonis G, Hartmann EE, Lambert SR; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . Association between occlusion therapy and optotype visual acuity in children using data from the infant aphakia treatment study: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(8):863-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell B, DuBois L, Lynn M, Ward MA, Lambert SR; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study contact lens experience to age 5 years. Eye Contact Lens. 2017;43(6):352-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell B, Ward MA, Lynn M, Dubois L, Lambert SR; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study contact lens experience: one-year outcomes. Eye Contact Lens. 2012;38(4):234-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drews-Botsch C, Cotsonis G, Celano M, Lambert SR. Assessment of adherence to visual correction and occlusion therapy in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2016;3:158-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Autrata R, Rehurek J, Vodicková K. Visual results after primary intraocular lens implantation or contact lens correction for aphakia in the first year of age. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219(2):72-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solebo AL, Russell-Eggitt I, Cumberland PM, Rahi JS; British Isles Congenital Cataract Interest Group . Risks and outcomes associated with primary intraocular lens implantation in children under 2 years of age: the IoLunder2 cohort study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(11):1471-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartmann EE, Lynn MJ, Lambert SR; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . Baseline characteristics of the infant aphakia treatment study population: predicting recognition acuity at 4.5 years of age. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;56(1):388-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman SF, Lynn MJ, Beck AD, Bothun ED, Örge FH, Lambert SR; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . Glaucoma-related adverse events in the first 5 years after unilateral cataract removal in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(8):907-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittelviefhaus H, Mittelviefhaus K, Gerling J. Etiology of contact lens failure in pediatric aphakia. Indications for intraocular lenses? [in German]. Ophthalmologe. 1998;95(4):207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozbek Z, Durak I, Berk TA. Contact lenses in the correction of childhood aphakia. CLAO J. 2002;28(1):28-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loudot C, Jourdan F, Benso C, Denis D. Aphakia correction with rigid contact lenses in congenital cataract [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2012;35(8):599-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaya LG, Speedwell L, Taylor D. Contact lenses for infant aphakia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74(3):150-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aasuri MK, Venkata N, Preetam P, Rao NT. Management of pediatric aphakia with silsoft contact lenses. CLAO J. 1999;25(4):209-212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruger SJ, DuBois L, Becker ER, et al. ; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . Cost of intraocular lens versus contact lens treatment after unilateral congenital cataract surgery in the infant aphakia treatment study at age 5 years. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(2):288-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Reported Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses from Age 1 to 5 Years vs Sex in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study

eFigure 2. Reported Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses From Age 1 to 5 Years as a Function of Private vs Public Health Insurance in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study

eFigure 3. Reported Percentage of Waking Hours Spent Wearing Contact Lenses From Age 1 to 5 Years vs Age at Cataract Surgery (<49 days vs 49 days or older) in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study