Abstract

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG), severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, occurs in 0.3–2% of pregnancies and is associated with maternal and fetal morbidity. The cause of HG remains unknown, but familial aggregation and results of twin studies suggest that understanding the genetic contribution is essential for comprehending the disease etiology. Here, we conduct a genome-wide association study (GWAS) for binary (HG) and ordinal (severity of nausea and vomiting) phenotypes of pregnancy complications. Two loci, chr19p13.11 and chr4q12, are genome-wide significant (p < 5 × 10−8) in both association scans and are replicated in an independent cohort. The genes implicated at these two loci are GDF15 and IGFBP7 respectively, both known to be involved in placentation, appetite, and cachexia. While proving the casual roles of GDF15 and IGFBP7 in nausea and vomiting of pregnancy requires further study, this GWAS provides insights into the genetic risk factors contributing to the disease.

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a severe form of nausea and vomiting associated with unfavourable outcomes during pregnancy. Here, Fejzo et al. perform genome-wide scans for HG and pregnancy nausea and vomiting and identify genetic associations at two loci implicating the genes GDF15 and IGFBP7.

Introduction

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) affects 50–90% of pregnant women1 and as many as 18% of pregnant women take medication to treat this condition2. Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is the most severe form and occurs in 0.3–2% of pregnancies3. Its clinical presentation includes severe intractable vomiting, often associated with dehydration, weight loss (>5% pre-pregnancy weight), ketonuria, nutritional deficiencies, and electrolyte disturbances4. The severity of the disease has been well documented, for instance with the death of author Charlotte Brontë5. To this day, HG remains the second leading cause of hospitalization during pregnancy6.

Despite the prevalence of NVP and the gravity of HG, decades of research have failed to identify the cause, and a clinically proven, safe, and effective treatment has yet to be found7. While the absence of NVP is associated with a higher risk of miscarriage8, having the most severe form of nausea and vomiting (HG) is also associated with poor fetal outcomes including preterm birth, neurodevelopmental delay, and vitamin K deficient embryopathy9–11. Several possible etiological factors have been investigated but the cause is unknown. Support for a genetic component to NVP come from twin studies in Finnish, Norwegian, and Spanish cohorts12,13. Heritability estimates for presence of NVP are as high as 73%13. Mothers and sisters of women affected by HG are at increased risk compared to mothers and sisters of unaffected women14. The risk of HG is increased by 17-fold for sisters of HG patients, and there is a >27-fold increased risk of mother–daughter recurrence when a mother has HG with two daughters15,16.

The aim of this study is to use human genetics as a stepping-stone towards elucidating the causes of HG. Herein, we report a genome-wide association study (GWAS) aimed at identifying variants that influence the risk of HG. We performed two genome-wide association scans, one for a binary HG phenotype, and one for an ordinal phenotype related to HG (severity of NVP). The key findings were replicated in two independent populations of women with clinically defined HG.

Results

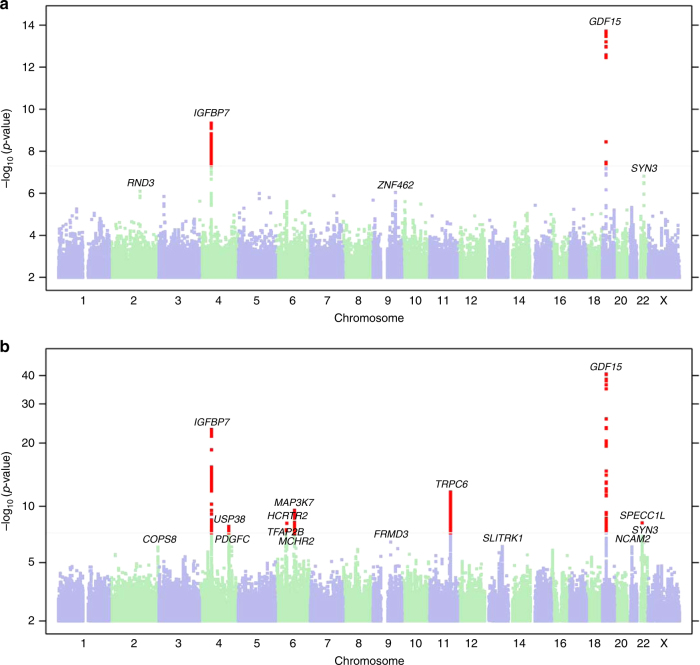

Genome-wide association scan of the binary phenotype

For SCAN1, we compared the ends of the clinical spectrum of NVP, HG versus absence of NVP. Participants were female customers of 23andMe, who consented to participate in research, are of European ancestry, and have completed the relevant on-line surveys. A total of 1306 research participants reporting that they received intravenous fluid (IV) therapy for NVP were classified as HG cases, and 15,756 participants who reported no NVP served as controls. Cohort statistics are shown in Table 1. Manhattan and quantile–quantile plots are shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a, respectively, and SNP-level QC information is shown in Supplementary Table 1b.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of unrelated female individuals of European descent included in SCAN1

| Phenotype | Group | Total | Female | Age < 30 | 30–44 | 45–59 | ≥60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HG | Case | 1306 | 1306 | 45 (3%) | 431 (33%) | 555 (42%) | 275 (21%) |

| Control | 15,756 | 15,756 | 392 (2%) | 3487 (22%) | 5357 (34%) | 6520 (41%) |

Fig. 1.

Genome-wide association scans for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. The Manhattan plot shows distribution of association test statistics vs. genomic position for a SCAN1 (binary phenotype), and b SCAN2 (ordinal phenotype). The Manhattan plot shows distribution of association test statistics versus genomic position. Chromosomes are arranged along the X-axis. Log10-scaled p-values are shown on the Y-axis. The loci with positions with p < 5 × 10−8 are shown in red and the loci with p < 10−6 are labeled with names of nearest genes

Most significantly associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or insertion or deletion polymorphisms (indels) in each locus are shown in Table 2. Two loci, chr19p13.11 (rs45543339, OR = 0.67, 95% CI [0.60, 0.74], p = 1.9 × 10−14) and chr4q12 (rs143409503, OR = 0.75 [0.69, 0.82], p = 4.5 × 10−10), reached genome-wide significance (p < 5 × 10−8). The 99% credible set for the chr19p13.11 association signal overlapped two genes, GDF15 and LRRC25 (see Supplementary Figure 2), and contained a common missense variant in GDF15 (rs1058587, p.H202D, MAF = 0.25, OR = 0.68 [0.62, 0.75], p = 3.4 × 10–14) in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the lead SNP rs45543339 (r2 = 0.98, D′ = 0.99). The chr4q12 association signal fell within an intergenic region with the closest genes being an uncharacterized lncRNA LOC101928851 (~18.7 kbp away from rs143409503) and protein-coding gene IGFBP7 (~380 kbp away from rs143409503). In addition, there were three more association signals with p < 10−6 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the genome-wide association study of no NVP vs HG (SCAN1) with p < 10−6. The directions of odds ratios (OR) correspond to the minor allele, listed second

| Cytoband | Marker | Position | Alleles | MAF | SCAN1 p-value | SCAN1 OR | SCAN1 95% CI | SCAN2 p-value | SCAN2 effect size | SCAN2 95% CI | Gene context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19p13.11 | rs45543339 | 19:18503194 | C/T | 0.25 | 1.9 × 10−14 | 0.668 | [0.601,0.743] | 5.7 × 10−39 | −0.104 | [−0.120, −0.890] | [LRRC25] |

| 4q12 | rs143409503 | 4:58351064 | −/AGC | 0.34 | 4.5 × 10−10 | 0.752 | [0.687,0.824] | 6.8 × 10−25 | −0.073 | [−0.087, −0.0587] | IGFBP7—[] |

| 22q12.3 | rs5998706 | 22:33440890 | C/T | 0.49 | 1.6 × 10−7 | 0.786 | [0.717,0.860] | 3.5 × 10−5 | −0.03 | [−0.044, −0.016] | [SYN3] |

| 2q23.3 | rs114571265 | 2:150910809 | G/C | 0.024 | 8.3 × 10−7 | 0.388 | [0.253,0.595] | 3.6 × 10−4 | −0.087 | [−0.133, −0.039] | MMADHC—[]—RND3 |

| 9q31.2 | rs56108151 | 9:109514426 | A/G | 0.095 | 9.2 × 10−7 | 0.677 | [0.575,0.797] | 5.9 × 10−4 | −0.034 | [−0.062, −0.017] | TMEM38B—[]—ZNF462 |

Genome-wide association scan of the ordinal phenotype

For SCAN2, we next conducted a genome-wide association scan of the 53,731 unrelated female 23andMe research participants of European descent, using NVP severity as an ordinal response: none (N = 14,988), slight (N = 14,292), moderate (N = 17,786), severe (N = 5445), and very severe NVP (N = 1220), coded on a scale of 0 to 4. Details of the definition of each response based on the survey data can be found in the Methods section. Cohort statistics are shown in Table 3. Manhattan and quantile–quantile plots are shown in Fig. 1b, and SNP-level QC information is shown in Supplementary Table 1c.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of unrelated female individuals of European descent included in SCAN2

| Phenotype | Group | Total | Age < 30 | 30–44 | 45–59 | ≥60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVP | None | 14,988 | 373 (2.5%) | 3332 (22.2%) | 5129 (34.2%) | 6154 (41.1%) |

| Slight | 14,292 | 233 (1.6%) | 2635 (18.4%) | 4831 (33.8%) | 6593 (46.1%) | |

| Moderate | 17,786 | 391 (2.2%) | 3692 (20.8%) | 6233 (35.0%) | 7470 (42.0%) | |

| Severe | 5445 | 140 (2.6%) | 1298 (23.8%) | 1580 (29.0%) | 2427 (44.6%) | |

| Very severe | 1220 | 42 (3.4%) | 409 (33.5%) | 519 (42.5%) | 250 (20.5%) |

The two most strongly associated loci in SCAN2 were also genome-wide significant in SCAN1: chr19p13.11 (rs16982345, β = −0.104 [−0.12, −0.089], p = 2.4 × 10−41) and chr4q12 (rs143409503, β = −0.072 [−0.086, −0.058], p = 9.2 × 10−24). Five additional regions reached genome-wide significance in SCAN2 (Table 4; Supplementary Figure 3) and there were eight additional association signals in SCAN2 with p < 10−6 (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 4.

Results of GWAS of NVP as an ordinal response (SCAN2) with p < 5 × 10−8. The directions of effect correspond to the minor allele, listed second

| Cytoband | Marker | Position | Alleles | MAF | p-value | β | 95% CI | SCAN1 p-value | SCAN1 OR | SCAN1 95% CI | Gene context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19p13.11 | rs16982345 | 19:18500722 | G/A | 0.25 | 2.4 × 10−41 | −0.104 | [−0.120, −0.089] | 6.81 × 10−15 | 0.68 | [0.615, 0.751] | GDF15[]-LRRC25 |

| 4q12 | rs143409503 | 4:58351064 | −/AGC | 0.34 | 9.2 × 10−24 | −0.072 | [−0.086,−0.058] | 1.86 × 10−10 | 0.752 | [0.688, 0.822] | IGFBP7—[] |

| 11q22.1 | rs2508362 | 11:101260798 | A/G | 0.199 | 1.7 × 10−12 | 0.06 | [0.043,0.076] | 1.06 × 10−04 | 0.819 | [0.741, 0.904] | PGR—[]–TRPC6 |

| 6q15 | rs4707680 | 6:92294371 | T/C | 0.427 | 2.8 × 10−10 | 0.043 | [0.030, 0.056] | 5.79 × 10−02 | 0.924 | [0.851, 1.00] | MAP3K7-[] |

| 22q11.23 | rs201838815 | 22:24753023 | T/− | 0.02 | 5.8 × 10−9 | −0.159 | [−0.212, −0.105] | 2.88 × 10−02 | 0.685 | [0.480, 0.979] | [SPECC1L,SPECCl-ADORA2A] |

| 6p12.1 | rs7761177 | 6:55151343 | T/C | 0.495 | 6.2 × 10−9 | −0.039 | [−0.052, −0.026] | 1.70 × 10−06 | 0.82 | [0.755, 0.889] | HCRTR2-[]–GFRAL |

| 4q31.21 | rs4690766 | 4:144030040 | G/C | 0.358 | 1.3 × 10−8 | −0.04 | [−0.054, −0.026] | 1.02 × 10−01 | 0.932 | [0.856, 1.01] | INPP4B—[]–USP38 |

Replication

Two loci were genome-wide significant in both association scans and were selected for replication genotyping. Given that the replication cohorts contain information on HG as a binary trait and that HG is the more clinically relevant phenotype, three additional loci with p < 10−6 in the binary trait scan (SCAN1) were also selected for replication. The first replication cohort (HG-IV) included 789 women with HG requiring IV fluid treatment and 606 controls reporting normal NVP. The second replication cohort (HG-TPN) included only women at the extreme ends of the clinical spectrum, 110 women requiring total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and 143 women reporting no NVP. Basic demographics of the replication cohorts are shown in Table 5. Over 90% of participants self-reported that they were of European descent.

Table 5.

Demographic characteristics of the replication cohorts HG-IV consisting of HG patients treated with intravenous (IV) fluids and controls with untreated NVP, and HG-TPN consisting of HG patients treated with total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and controls with no NVP

| Total | Year born (average) | Ethnicity (European descent) | Attended college | Advanced degree | First child year born | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HG-IV | ||||||

| HG | 789 | 1977 | 90% | 61% | 19% | 2003 |

| Control | 606 | 1975 | 92% | 62% | 18% | 2002 |

| HG-TPN | ||||||

| HG | 110 | 1976 | 90% | 61% | 26% | 2002 |

| Control | 143 | 1974 | 93% | 51% | 25% | 2001 |

We selected rs16982345 in the chr19p13.11 locus as a proxy for the lead SNP rs45543339 (r2 = 0.98, D′ = 0.99) for replication in HG-IV (because rs16982345 had a commercially available high quality SNP assay using the Taqman genotyping system). rs16982345 was successfully genotyped in 789 individuals with clinically defined HG and 581 controls reporting normal NVP using the TaqMan genotyping platform (Table 6). The call rate was >95%. The replication results for rs16982345 were supportive of the GWAS result (p = 2.8 × 10−7, OR = 1.63 [1.35, 1.98]).

Table 6.

Replication results based on Fisher’s exact test for the two most significantly associated loci in SCAN1 and SCAN2: rs16982345 (chr19p13.11), rs4865234 (chr4q12), and the three association signals in SCAN1 with p > 5 × 10−8 and p < 1 × 10−6, rs5754397 (SYN3) rs78353059 (MMADHC/RND3), and rs56108151 (TMEM38B/ZNF462)

| N | Genotype 1 | Genotype 2 | Genotype 3 | p-value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs16982345 | GG | AG | AA | ||||

| HG-IV | 789 | 540 | 229 | 20 | |||

| CONTROL | 581 | 330 | 210 | 41 | 2.80 × 10−7 | 1.63 | 1.35–1.98 |

| HG-TPN | 103 | 68 | 33 | 2 | |||

| NO NVP | 136 | 75 | 51 | 10 | 0.04 | 1.61 | 1.01–2.60 |

| rs4865234 | AA | AG | GG | ||||

| HG-IV | 778 | 404 | 312 | 62 | |||

| CONTROL | 603 | 259 | 273 | 71 | 3.50 × 10−4 | 1.35 | 1.14–1.59 |

| HG-TPN | 110 | 64 | 38 | 8 | |||

| NO NVP | 143 | 57 | 66 | 20 | 2.81 × 10−3 | 1.81 | 1.21–2.73 |

| rs5754397 | CC | CT | TT | ||||

| HG-IV | 774 | 218 | 353 | 203 | |||

| CONTROL | 606 | 180 | 273 | 153 | 0.51 | 0.95 | 0.82–1.11 |

| HG-TPN | 106 | 37 | 44 | 25 | |||

| NO NVP | 141 | 44 | 64 | 33 | 0.72 | 1.07 | 0.74–1.56 |

| rs78353059 | AA | AG | GG | ||||

| HG-IV | 779 | 735 | 42 | 2 | |||

| CONTROL | 596 | 561 | 34 | 1 | 0.82 | 1.07 | 0.66–1.71 |

| HG-TPN | 105 | 99 | 6 | 0 | |||

| NO NVP | 136 | 125 | 11 | 0 | 0.62 | 1.43 | 0.48–4.80 |

| rs56108151 | AA | AG | GG | ||||

| HG-IV | 780 | 625 | 150 | 5 | |||

| CONTROL | 594 | 495 | 97 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.59–1.02 |

| HG-TPN | 108 | 86 | 22 | 0 | |||

| NO NVP | 141 | 117 | 23 | 1 | 0.64 | 0.86 | 0.45–1.65 |

The number (N) for each group is the total number of samples that were successfully genotyped. The call rate was >95%. OR estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values were computed using 2 × 2 contingency tables in R. The effect allele is assumed to be the allele in the left-most (i.e., first) homozygous cell

We also successfully genotyped the variant in 103 women with HG who required TPN and 136 women who reported no NVP in at least two pregnancies (HG-TPN). The genotyping results had comparable effect size, but were not significant after multiple testing correction (p = 0.04, OR = 1.61 [1.01, 2.60]) (Table 6).

We also performed replication of the second genome-wide significant locus. rs4865234 was used as a proxy for rs143409503 (r2 = 0.95, D′ = 1.0) (because rs143409503 is an indel, which cannot be assayed using the TaqMan genotyping system). rs4865234 replicated in HG-IV (p = 3.5 × 10−4, OR = 1.35 [1.14, 1.59]) (Table 6). The genotyping results of DNA from HG-TPN were also supportive (p = 2.8 × 10−3, OR = 1.81 [1.21, 2.73]).

The three additional SNPs with p < 10−6 in the binary trait scan (rs5754397, rs78353059, rs56108151) did not replicate in HG-IV nor in HG-TPN (p > 0.05, see Table 6).

Combined analysis

For the replicated loci, we combined the replication results with SCAN1 using a fixed-effect meta-analysis (Table 7). Briefly, this test computes a weighted average of odds-ratio estimates across studies while accounting for standard errors. For rs16982345 on chr19p13.11, we estimated a meta-OR of 1.50 [1.38, 1.65] (p = 2.12 × 10−19). Heterogeneity of individual effect sizes did not appear to influence the combined estimate (phet = 0.66). For rs4865234 on chr4q12, the meta-OR was 1.33 [1.23, 1.62] (p = 9.29 × 10−12) with little evidence of effect size heterogeneity (phet = 0.727).

Table 7.

Results of meta-analysis of SCAN1 and replication cohorts

| SNP | CHR | BP | A0 | A1 | Study | HG | CONTROL | OR | 95% CI | p-value | Het p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 Freq | A1 Freq | ||||||||||

| rs16982345 | chr19 | 18500722 | A | G | SCAN1 | 0.8 | 0.73 | 1.47 | [1.33, 1.63] | 6.81E−15 | – |

| HG-IV | 0.83 | 0.75 | 1.63 | [1.35, 1.98] | 2.80E−07 | – | |||||

| HG-TPN | 0.82 | 0.74 | 1.61 | [1.01, 2.60] | 4.00E−02 | – | |||||

| META | – | – | 1.5 | [1.38, 1.65] | 2.12E−19 | 6.62E−01 | |||||

| rs4865234 | chr4 | 58355015 | G | A | SCAN1 | 0.7 | 0.64 | 1.32 | [1.20, 1.43] | 7.95E−10 | – |

| HG-IV | 0.72 | 0.66 | 1.43 | [1.16, 1.79] | 9.00E−04 | – | |||||

| HG-TPN | 0.75 | 0.63 | 1.82 | [1.20, 2.70] | 2.81E−03 | – | |||||

| META | – | – | 1.33 | [1.23, 1.62] | 9.29E−12 | 7.27E−01 |

A1 is the allele associated with increased risk of HG

Conditional analyses

In order to identify additional association signals, we performed stepwise conditional analysis at all loci that reached genome-wide significance in either SCAN1 or SCAN2. Conditional analysis detected secondary associations in the chr19p13.11 locus in SCAN1 and in the chr19p13.11 and PGR/TRPC6 loci in SCAN2 (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figures 4 and 5). LD between the primary and secondary signals is low (r2 < 0.01), suggesting that they are independent signals corresponding to multiple risk variants within the locus.

The secondary signal in the chr19p13.11 locus identified from SCAN1 (rs1054221, OR = 1.38 [1.22, 1.56], p = 1.7 × 10−7) maps within the 3′ UTR of GDF15. The secondary signal from SCAN2 in this same locus is a common, single-nucleotide deletion with an effect comparable to the primary association (rs34345957, β = 0.11 [0.089, 0.13], p = 1.1 × 10−28, MAF = 0.14), located in the intron of LRRC25, and in high LD (r2 = 0.98, D′ = 1.0) with the secondary signal in SCAN1. The tertiary association signal within the chr19p13.11 locus in SCAN2 is weaker (rs4808787, β = −0.037 [−0.053, −0.021], p = 6.0 × 10−6) and is located in the 5′ UTR of the long isoform of PGPEP1.

Functional analyses of chr19p13.11 and chr4q12 genomic loci

The genomic context of the replicated loci chr19p13.11 and chr4q12 was analyzed using HaploReg17 (Supplementary Data 1). Within those two regions, we analyzed A) the index SNPs for strongest association in SCAN1 (rs45543339 and rs143409503) and the proxy SNPs that were confirmed in B) the independent replication cohort (rs16982345 and rs4865234).

The lead SNP at chr19p13.11, rs45543339, was located in an intron of LRRC25, and the only notable functional annotation was an eQTL for KCNN1 in mucosa of the esophagus. rs16982345, which is within the 99% credible set at this locus and is in tight LD (r2 = 0.98) with the lead SNP rs45543339, is located within an intron of GDF15 (Supplementary Data 1 and 2). It overlapped enhancer histone marks in three tissues, including placenta, and DNAse hypersensitivity sites in nine tissues, including ovary. A summary of the variants in LD with the lead SNP and associated with altered GDF15 expression is shown in Supplementary Data 217–20,39–42,44, with the full list of variants in LD with the lead SNP identified using HaploReg listed in Supplementary Data 1. One of the variants associated with HG in SCAN1, rs17725099 (p = 1.03 × 10−13) and in LD with rs16982345 (r2 = 0.77), was the top association signal (β = 0.16, p = 1.47 × 10–107) in a conference abstract which identified variants influencing GDF15 levels in patients with cardiovascular disease18. The SNP rs17725099 was also associated with circulating levels of GDF15 in the first study to report on the heritability of GDF15 plasma concentration19. In addition, rs1058587, a SNP in perfect LD (r2 = 1) with the lead SNP and a part of the 99% credible set at this locus in SCAN1, has previously been associated with altered GDF15 expression. Expression levels of GDF15 were compared in an in vitro model between the cell line DU145 transfected with wild-type GDF15 (rs1058587, C allele) and GDF15 (rs1058587, G allele)20. The C allele of rs1058587 was associated with increased GDF15 levels in the in vitro model and was also the risk allele associated with HG, providing evidence that the direction of effect is toward higher levels of GDF15 for HG compared to controls.

The lead indel at chr4q12, rs143409503, mapped to an intergenic region with the closest protein-coding gene being IGFBP7, ~380 kbp away from the marker. No notable features were identified using HaploReg17, the GTEx portal, nor ExSNP21 databases. Other phenotypes associated with SNPs in GDF15 and IGFBP7 are reported in Supplementary Note 141–56.

Discussion

This GWAS of HG identified two genome-wide significant signals that were subsequently replicated in the larger of two independent cohorts (HG-IV). The most significantly associated locus on chr19p13.11 contained genes GDF15 and LRRC25. While we cannot be certain which gene or genes are implicated, SNPs in LD with the associated variants at the chr19p13.11 locus were found to be associated with altered expression of GDF15. In addition, the gene encoding the receptor for GDF15, the brainstem-restricted receptor GFRAL22, was associated with NVP in SCAN2 (Table 4) adding further evidence supporting a previously unknown biological connection between GDF15 and HG. While the results of this study do not establish a causal link between GDF15 and HG, the association between this gene and HG is of particular importance because it highlights the possibility of a pathway involved in the etiology of the condition. GDF15 encodes a TGF-β superfamily member that is expressed at its highest levels in the trophoblast cells of the placenta23. The protein is found in maternal serum and increases significantly in the first two trimesters23. GDF15 is believed to suppress production of proinflammatory cytokines in order to facilitate placentation and maintain pregnancy24. In addition to its role in pregnancy, GDF15 has been shown to be a regulator of physiological body weight and appetite via activation of neurons in the hypothalamus and area postrema (vomiting center) of the brainstem25,26. It is also notable that abnormal overproduction of GDF15 in cancer was recently found to be the key driver of cancer anorexia and cachexia which, like HG, exhibits symptoms of chronic nausea and weight loss27,28. Of particular clinical interest, inhibition of GDF15 restored appetite and weight gain in a mouse model of cancer cachexia28, suggesting a therapeutic strategy that may be applicable to patients with HG, if GDF15 proves to be the implicated gene.

The other locus that reached genome-wide significance and was confirmed in the independent replication cohort, is chr4q12. Although there were no genes that can be directly related to the association signal, the protein-coding gene closest to the lead variant is IGFBP7. We have not found eQTLs that link the variants associated in this study to expression of IGFBP7, however, this can be explained at least in part by a lack of eQTL data in relevant tissues during pregnancy. The notably similar and functionally relevant roles of IGFBP7 and GDF15 (in placentation, cachexia, and feeding behavior) make a compelling argument for IGFBP7 despite the lack of evidence linking the association signal to its expression. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) is a gene involved in implantation and decidualization of the pregnant uterus29. Like GDF15, IGFBP7 is significantly upregulated after implantation and highly expressed in the developing placenta30. Inhibition of IGFBP7 caused pregnancy loss in a mouse model by shifting uterine cytokines to Th1 type dominance and repressing uterine decidualization30. Thus IGFBP7 may play roles in both miscarriage and in the severity of NVP, providing a genetic mechanism for the protective effect of NVP. In addition, like GDF15, evidence points to IGFBP7 as a promising biomarker for cachexia associated with end-stage disease29. An intriguing finding is that the Drosophila homolog of IGFBP7 has been suggested to play a role in neuronal coordination between metabolic status and feeding behavior, potentially, like with HG, causing food aversion to normally attractive food, even when starving, and vice versa31.

The strengths of this study include the well-defined phenotype and large sample sizes in two scans and the HG-IV replication sample. The strong independently replicated association signals, and the fact that both candidate genes have roles in early pregnancy when HG sets in, support these genes as functional as well as positional candidate genes30,32. However, it is important to replicate the findings reported herein, both using larger replication sample sizes (for HG-TPN vs no NVP) and in studies of different ethnicities to determine whether the findings can be validated and generalized to other populations. Another caveat is that while the conditional analysis yielded additional association signals at chr19p13.11 that may act independently of the lead association signal, they were not replicated. Replication is necessary to determine if additional independent variants are associated at this locus. Finally, the lack of eQTL data and considerable distance between the chr4q12 association signal and the closest gene IGFBP7 is a noteworthy limitation.

Future research should focus on functional follow-up. Since GDF15 and IGFBP7 levels are upregulated during placentation and cachexia23,24,28,29, and downregulated prior to miscarriage30,32, serum concentrations of GDF15 and IGFBP7 should now be studied in pregnant women with and without HG. If GDF15 or IGFBP7 prove to be relevant, it is conceivable that drugs targeting these proteins may have clinical utility in treating HG. Such a study may also lead to new methods for prediction and diagnosis. In addition, the SCAN2 results suggest a great potential for discovering additional loci associated with HG or NVP. Finally, the findings herein suggest an answer to an age-old paradox. HG can lead to prolonged dehydration and undernutrition, which can be detrimental to maternal and fetal health and can decrease reproductive fitness. The dual roles of GDF15 and IGFBP7 in maintaining pregnancy and in increasing the risk of HG may provide a molecular explanation for why NVP still exists in nature.

Methods

Human subjects for GWAS

GWAS participants were customers of 23andMe, Inc. who consented to participate in research, and provided answers to the morning sickness-related questions. Two genome-wide association scans were performed, for (1) a binary HG phenotype and (2) an ordinal phenotype related to HG. Phenotype definitions are described below. Due to the nature of the phenotype definitions, some research participants were included in both association scans. All research participants included in the analysis provided informed consent and answered on-line surveys according to a human subjects protocol approved by Ethical & Independent Review Services, a private institutional review board.

Phenotype definitions

For the binary HG phenotype analyzed in SCAN1, we compared two ends of the clinical spectrum of NVP: 1306 research participants who reported via an on-line survey that they received IV therapy for NVP were classified as HG cases and 15,756 participants who reported no NVP served as controls. The phenotype definition was ascertained using the interview questions listed in Supplementary Note 2. For the ordinal phenotype related to HG analyzed in SCAN2, data were pulled from four questions also listed in Supplementary Note 2.

Genotyping and imputation and association testing

A total of 17,062 females in SCAN1 and 53,731 females in SCAN2 were genotyped on one of four custom Illumina genotyping arrays and additional genotypes were imputed using the September 2013 release of the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 133 reference haplotypes as described previously34,35. 16,165 individuals in SCAN1 were also included in SCAN2. Breakdown of the number of participants in specific phenotype categories in SCAN1 and SCAN2 are shown in Supplementary Table 1a. Fields that contain 5 or fewer individuals have been masked to protect the privacy of 23andMe customers. All females were filtered to select for European ancestry, and close relatives were removed. We performed logistic (SCAN1) and linear (SCAN2) regression assuming an additive model for allelic effects on NVP, using age and five principal components of genetic ancestry as covariates. Our previously published analysis of categorical phenotypes using ordinal and linear regression showed high concordance between resulting p-values36. Due to comparative ease of implementation and lower computational burden, we used linear regression in SCAN2.The SNP-level quality control information is shown in Supplementary Tables 1b and 1c. Test statistics were further adjusted for the genomic control inflation factor of λ = 1.044 for SCAN1 and λ = 1.087 for SCAN2. The index SNPs were identified by choosing the SNPs with the strongest association in each associated region. Each region contained SNPs with p < 10−5 that were grouped into intervals separated by a gap of a minimum of 250 kbp. The SNP with the smallest p-value within each interval was chosen as the lead SNP.

Credible sets

To account for the uncertainty in identifying the true causal variant within an association signal, we computed 99% credible sets at each locus. Under the assumptions that there is a single causal variant at a locus and that this variant was genotyped in the association study, 99% credible sets are defined as smallest sets of variants that are 99% likely, based on posterior probability, to contain the causal variant37. While these assumptions are not always true in practice, credible sets provide a helpful summary of the available evidence that one of the SNPs contained in them is causal, and may help in fine-mapping the association signal.

Replication cohorts

The first replication cohort (HG-IV) included 789 HG cases treated with IVs and 606 controls with NVP that did not require treatment. The second replication cohort (HG-TPN) included 110 cases requiring TPN due to HG and 143 controls reporting no NVP in any of at least two pregnancies. All participants gave informed consent. This study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board.

Phenotype definition in the replication cohort

Affected individuals were included if they had an HG diagnosis and were treated with IV fluids and/or TPN. Participants affected by HG recruited acquaintances that were non-blood related and had at least two pregnancies lasting more than 27 weeks gestation. Controls were eligible to participate in the study if they reported normal or no NVP, did not lose weight due to nausea/vomiting, and did not receive medical attention due to NVP.

Recruitment of the replication cohort

For the replication study, the source population for HG cases included patients residing in the US. The majority of cases were recruited through a posting from 2007 to 2017 on the Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation website (www.HelpHer.org). Minors (under 18 years) were excluded because the risk to benefit ratio to control minors would be difficult to justify and the study requires controls to have had two pregnancies, which is uncommon in minors. Women with pregnancies with chromosome abnormalities and multiple gestations were excluded due to possible distinct etiologies for NVP in these cases. Medical records and recruitment of an acquaintance with at least two pregnancies to serve as a control, were requested of each case. All participants were required to go over an information sheet by phone and return a signed information sheet with all elements of consent in order to enroll in the study.

Sample collection

Saliva samples were collected for DNA analysis from all cases and controls. DNA Genotek saliva kits (Oragene, Ottawa, Canada) were mailed to all cases and controls. The saliva collection kit is self-administered and comes with directions for submitting 2 ml of saliva into a collection vial and returning the sample to the study site via an addressed and postage-paid return envelope provided with the collection kit.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from the saliva samples according to manufacturer’s instructions (Oragene, Ottawa Canada). Using the kit, we have successfully isolated, on average, 197 µg of DNA of high quality (260/280 1.84) from 2 ml of saliva. The low end of expected DNA quantity reported by the manufacturer is 30 µg/ml of saliva or 60 µg/sample. After the extraction, the DNA was stored at −20 °C.

Quality control for replication data

The TaqMan genotyping platform was performed on 384-well plates with a minimum of two blank samples per plate and a minimum of two duplicate samples per plate. Once genotypes were determined from the first 384-well plate, a minimum of three positive controls or one positive control for each genotype was added to the remaining plates. The minimum call rate for each SNP was >95%.

Genotyping and statistical analysis in the replication study

rs16982345, the SNP with the strongest association to NVP in the chr19p13.11 locus was selected for genotyping in the replication sample HG-IV consisting of 789 cases and 606 controls. For the non-coding marker rs16982345 in chr19p13.11, genotyping a minimum of 780 cases and 580 controls, and assuming a proportion of the GG genotype similar to SCAN1 (0.53 for controls and 0.64 for cases), we estimated a power greater than 97% to detect between-group genotype differences using a two-sample, two-sided test of proportions at significance level alpha = 0.05.

In addition, we genotyped an extreme cohort (HG-TPN) consisting of 110 women who reported TPN for HG and 143 controls with no NVP in two or more pregnancies. TaqMan genotyping primers for rs16982345 were available from Thermo Fisher Scientific and Applied Biosystems PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (TaqMan) was used for large-scale screening. The call rate was >95%.

Genotypes were tested for significant association with HG using Fisher’s exact test using 2 × 2 contingency tables counting the number effect vs non-effect alleles for cases and controls using R.

The SNP rs4865234 was genotyped as a proxy for the most significant association signal at chr4q12 because the most significant association signal, rs143409503, is an indel, which cannot be assayed using the TaqMan genotyping system. The SNP rs4865234 is in tight LD with rs143409503 (r2 = 0.95, D′ = 1.0) and genotyped on DNA isolated from HG-IV and HG-TPN cohorts as stated previously for rs16982345.

The 3 additional loci that reached significance p < 10−6 in the binary trait scan (SCAN1) were also genotyped in the two replication cohorts (HG-IV and HG-TPN) using the TaqMan genotyping platform. The SNP rs5754397 was used as a proxy for the lead SNP rs5998706 (r2 = 0.55, D′ = 0.83), and the SNP rs78353059 was used as a proxy for the lead SNP rs114571265 (r2 = 0.87, D′ = 1.0) because they were the closest SNPs listed in HaploReg17 to the lead SNP with an available commercially validated assay from Thermo Fisher Scientific and they also reached significance p < 10−6 in SCAN1. The lead SNP rs56108151 was commercially available and used for genotyping the two replication cohorts.

Meta-analysis of SCAN1 and replication

We performed a fixed-effect meta-analysis using the R language and software meta to compute the weighted average odds-ratio across the replication group and SCAN1 for sites rs16982345 and rs4865234. The fixed-effect meta-analysis assumes that there exists a true underlying effect in the population and combines individual study estimates (e.g., replication and SCAN1) to obtain a meta estimate. This assumption may be invalid in practice due to differences in linkage disequilibrium patterns across studies, or differences in covariates included. To test for hetereogeneity in effects across studies, or significant study-wide variance, we estimated Cochran’s Q38 for each SNP. This measures the variance across studies using the meta estimate as the true mean, which can be tested in a null-hypothesis framework under a distribution. Here, the number of studies is , so our heterogeneity p-values reflect a one-tailed test under a distribution.

Conditional analysis

The stepwise conditional analysis detects statistically independent signals in a GWAS locus. At each step, we assessed association between variants within 20 kbp around a GWAS locus and the HG or related ordinal phenotype, using top SNPs from preceding steps as additional covariates. This was repeated until no significant association was detected at p < 10−5. Finally, we fit a joint model with all of the primary and secondary signals and evaluated its goodness of fit through the likelihood ratio test (LRT) against the model with just the primary signal. The reported effect sizes of the secondary signals are from the joint model, and the p-values are from the likelihood ratio test comparing the full model with the leave-one-out models.

In silico functional follow-up

We used the HaploReg17 v4.1 tool to identify SNPs in the haplotype blocks containing the two significant GWAS association signals, their LD r2 and D′ scores, associated alleles, allele frequencies, genes, functional annotation, conservation, regulatory elements, protein-binding sites, motif changes, and eQTLs. We queried the two most significant loci identified, chr19p13.11 and chr4q12. Within those two regions, we analyzed SNPs with HaploReg, which uses LD information from the 1000 Genomes Project33. The LD threshold in HaploReg v4.1 was set at r2 = 0.2: the population used for LD calculations was the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 1 European descent: the source for epigenomes was the ChromHMM (Core 15-state model); the mammalian conservation algorithms GERP and SiPhy-omega, and positions are shown relative to GENCODE genes (Supplementary Data 1). HaploReg v4.1 includes GWAS and eQTL (including GTEx) and GRASP eQTL updates which were queried for the SNPs and included in Supplementary Data 1.

We also queried the GTEx portal and ExSNP integrated eQTL databases21 for the top candidate genes (based on loci identified in this study and similar function in early pregnancy reported previously30,32, GDF15 and IGFBP7) to identify eQTLs (17 and 28 studies, respectively) included in the databases. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health, and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. The data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from (https://gtexportal.org/home/bubbleHeatmapPage/) the GTEx Portal on 05 May 2017. The SNPs identified were cross checked with the SNPs identified in haplogroups by HaploReg.

Functional annotation of all SNPs (SNPs r2 > 0.2 with SNPs in the two loci that were found to be in coding regions by HaploReg were queried for all predicted consequences using the 1000 Genomes Project33.

Finally, published studies reporting SNPs linked to altered expression of the top candidate genes (GDF15 and IGFBP7) and SNPs in the top candidate genes reported in association studies in the GWAS catalog (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/ accessed on May 2017) and/or in published studies were cross checked with the SNPs identified in HaploReg to determine whether they are in LD with the SNPs linked to HG in our study.

Code availability

All relevant software, including version details, used for the primary GWAS and conditional analyses are described in the references included in the Methods section. All relevant codes with respect to the replication are available from the author M.S.F. (mfejzo@mednet.ucla.edu).

Data availability

Qualified researchers can contact apply.research@23andMe.com to gain access to full GWAS summary statistics following an agreement with 23andMe that protects 23andMe participant privacy. All relevant replication data are available from the author M.S.F. (mfejzo@mednet.ucla.edu).

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files(PDF 799 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the 23andMe research participants for their contributions to this study. We are grateful to the participants with HG and their acquaintances that participated in the follow-up study. This work was supported, in part, by the participants and by 23andMe, Inc. This work was also funded, in part, by the Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation, the Paul and Janis Plotkin Family Foundation, and grants U01 CA188392; U01-CA194393; R01-HG009120.

Author contributions

M.S.F. contributed to the overall study design, enrollment, implementation, data analysis, analysis for the replication study, and writing of the manuscript. O.V.S., J.F.S., I.B.H., and V.V. contributed to the GWAS analyses and interpretation, and manuscript preparation, K.W.M. contributed to the enrollment for the follow-up study, F.P.S. contributed to the study design for statistical analyses and manuscript preparation, N.M. contributed to the statistical analyses and manuscript preparation, D.J.S. contributed laboratory resources, and P.M.M. contributed to the data analysis and manuscript preparation. Members of the 23andMe research team provided infrastructure and support for data collection and GWAS analysis.

Competing interests

O.V.S., J.F.S., I.B.H., V.V. and members of the 23andMe research team are or have been employed by 23andMe, Inc. and may own stock or stock options in the company. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Marlena S. Fejzo, Olga V. Sazonova.

A full list of members of the 23andMe Research Team appears at the end of the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-03258-0.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marlena S. Fejzo, Email: mfejzo@mednet.ucla.edu

23andMe Research Team:

Michelle Agee, Babak Alipanahi, Adam Auton, Robert K. Bell, Katarzyna Bryc, Sarah L. Elson, Pierre Fontanillas, Nicholas A. Furlotte, David A. Hinds, Bethann S. Hromatka, Karen E. Huber, Aaron Kleinman, Nadia K. Litterman, Matthew H. McIntyre, Joanna L. Mountain, Elizabeth S. Noblin, Carrie A. M. Northover, Steven J. Pitts, Janie F. Shelton, Suyash Shringarpure, Chao Tian, Joyce Y. Tung, and Catherine H. Wilson

References

- 1.Clark S. M., Costantine M. M., & Hankins G. D. Review of NVP and HG and early pharmacotherapeutic intervention. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2012, 252676 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Piwko C, Koren G, Babashov V, Vicente C, Einarson TR. Economic burden of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in the USA. J. Popul Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;20:e149–e160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallen B. Hyperemesis during pregnancy and delivery outcome: a registry study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1987;26:291–302. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(87)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verberg MF, Gillott DJ, Al-Fardan N, Grudzinskas JG. Hyperemesis gravidarum, a literature review. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2005;11:527–539. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drife JO. Saving Charlotte Brontë. BMJ. 2012;344:e567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazmararian JA, et al. Hospitalizations during pregnancy among managed care enrollees. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthews, A., Haas, D. M., O’Mathúna, D. P. & Dowswell, T. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9, CD000145 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Hinkle SN, et al. Association of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy with pregnancy loss: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016;176:1621–1627. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fejzo MS, et al. Antihistamines and other prognostic factors for adverse outcome in hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013;170:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fejzo MS, Magtira A, Schoenberg FP, Macgibbon K, Mullin PM. Neurodevelopmental delay in children exposed in utero to hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015;189:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toriello HV, et al. Maternal vitamin K deficient embryopathy: association with hyperemesis gravidarum and Crohn disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2013;161A:417–429. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corey LA, Berg K, Solaas MH, Nance WE. The epidemiology of pregnancy complications and outcome in a Norwegian twin population. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;80:989–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colodro-Conde L, et al. Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy is highly heritable. Behav. Genet. 2016;46:481–491. doi: 10.1007/s10519-016-9781-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vellacott ID, Cooke EJA, James CE. Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Int J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1988;27:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(88)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, et al. Familial aggregation of hyperemesis gravidarum. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:230e.1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vikanes A, et al. Recurrence of hyperemesis gravidarum across generations: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2010;29:340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward, L. D. & Kellis, M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D930–D934 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Eriksson, N. et al. Genetic effects on levels of growth differentiation factor 15 - a PLATO genomics study. In Annual Meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics (American Society of Human Genetics, 2013).

- 19.Ho JE, et al. Clinical and genetic correlates of growth differentiation factor-15 in the community. Clin. Chem. 2012;58:1582–1591. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.190322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Chrysovergis K, Bienstock RJ, Shim M, Eling TE. The H6D variant of NAG-1/GDF15 inhibits prostate xenograft growth in vivo. Prostate. 2012;72:677–689. doi: 10.1002/pros.21471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu CH, Pal LR, Moult J. Consensus genome-wide expression quantitative trait loci and their relationship with human complex trait disease. OMICS. 2016;20:400–414. doi: 10.1089/omi.2016.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu, J.-Y. et al. Non-homeostatic body weight regulation through a brainstem-restricted receptor for GDF15. Nature550, 255–259 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Moore AG, et al. The transforming growth factor-ss superfamily cytokine macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 is present in high concentrations in the serum of pregnant women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;85:4781–4788. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marjono AB, et al. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 in gestational tissues and maternal serum in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancy. Placenta. 2003;24:100–106. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai, V. W. et al. TGF-b superfamily cytokine MIC-1/GDF15 is a physiological appetite and body weight regulator. PLoS ONE8, e55174 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Tsai, V. W. et al. The anorectic actions of the TGFβ cytokine MIC-1/GDF15 require an intact brainstem area postrema and nucleus of the solitary tract. PLoS ONE9, e100370 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Lerner L, et al. Plasma growth differentiation factor 15 is associated with weight loss and mortality in cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015;6:317–324. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lerner L, et al. MAP3K11/GDF15 axis is a critical driver of cancer cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:467–482. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loncar G, Omersa D, Cvetinovic N, Arandjelovic A, Lainscak M. Emerging biomarkers in heart failure and cardiac cachexia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:23878–23896. doi: 10.3390/ijms151223878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, Z. K., Wang, R. C., Han, B. C., Yang, Y. & Peng, J. P. A novel role of IGFBP7 in mouse uterus: regulating uterine receptivity through Th1/Th2 lymphocyte balance and decidualization. PLoS ONE7, e45224 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bader R, et al. The IGFBP7 homolog Imp-L2 promotes insulin signaling in distinct neurons of the Drosophila brain. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:2571–2576. doi: 10.1242/jcs.120261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong S, et al. Serum concentrations of macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 (MIC 1) as a predictor of miscarriage. Lancet. 2004;363:129–130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature526, 68–74 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Hromatka BS, et al. Genetic variants associated with motion sickness point to roles for inner ear development, neurological processes and glucose homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:2700–2708. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tung, J. Y., et al. Efficient replication of over 180 genetic associations with self-reported medical data. PLoS ONE6, e23473 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Jones AV, et al. GWAS of self-reported mosquito bite size, itch intensity and attractiveness to mosquitoes implicates immune-related predisposition loci. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:1391–1406. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, et al. Bayesian refinement of association signals for 14 loci in 3 common diseases. Nat. Genet. 44, 1294–1301 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Schwarzer, G., Carpenter, J. R. & Rücker, G. Meta-analysis with R (Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2015).

- 39.Lappalainen T, et al. Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature. 2013;501:506–511. doi: 10.1038/nature12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barreiro LB, et al. Deciphering the genetic architecture of variation in the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:1204–1209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115761109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ek WE, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation study identifies genes associated with the cardiovascular biomarker GDF-15. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:817–827. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Athiyarath R, George B, Mathews V, Srivastava A, Edison ES. Association of growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) polymorphisms with serum GDF15 and ferritin levels in β-thalassemia. Ann. Hematol. 2014;12:2093–2095. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, et al. The haplotype of the growth-differentiation factor 15 gene is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy in human essential hypertension. Clin. Sci. 2009;118:137–145. doi: 10.1042/CS20080637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown, D. A. et al. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1: a new prognostic marker in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 6658–6664 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Locke AE, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Julià A, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a novel locus at 6q22.1 associated with ulcerative colitis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:6927–6934. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arakawa S1, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for exudative age-related macular degeneration in the Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1001–1004. doi: 10.1038/ng.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun Y1, et al. TNFRSF10A-LOC389641 rs13278062 but not REST-C4orf14-POLR2B-IGFBP7 rs1713985 was found associated with age-related macular degeneration in a Chinese population. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013;54:8199–8203. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lauc, G. et al. Loci associated with N-glycosylation of human immunoglobulin G show pleiotropy with autoimmune diseases and haematological cancers. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003225 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Yang BZ, Han S, Kranzler HR, Palmer AA, Gelernter J. Sex-specific linkage scans in opioid dependence. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2017;174:261–268. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel YM, et al. The contribution of common genetic variation to nicotine and cotinine glucuronidation in multiple ethnic/racial populations. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2015;24:119–127. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang YJ, et al. The functional IGFBP7 promoter −418G> A polymorphism and Risk of Head and Neck Cancer. Mutat. Res. 2010;702:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicoletti P, et al. Genomewide pharmacogenetics of bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw. The role of RBMS3. Oncologist. 2012;17:279–287. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fan Y1, et al. Genome-wide association study for pigmentation traits in Chinese Holstein population. Anim. Genet. 2014;45:740–744. doi: 10.1111/age.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.García-Gámez, E. et al. Using regulatory and epistatic networks to extend the findings of a genome scan: identifying the gene drivers of pigmentation in merino sheep. PLoS ONE6, e21158 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Luo W, et al. Genome-wide association study of porcine hematological parameters in a Large White×Minzhu F2 resource population. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012;8:870–881. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files(PDF 799 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers can contact apply.research@23andMe.com to gain access to full GWAS summary statistics following an agreement with 23andMe that protects 23andMe participant privacy. All relevant replication data are available from the author M.S.F. (mfejzo@mednet.ucla.edu).