Abstract

Introduction:

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic inflammatory, autoimmune, mucocutaneous disease of unknown etiology. The first line of treatment for oral LP (OLP) has been corticosteroids, but because of their adverse effects, alternative therapeutic approaches are being carried out, of which the recent natural alternative is propolis.

Aim:

This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of topical propolis in the management of OLP.

Materials and Methods:

The research group consisted of 27 patients diagnosed with symptomatic OLP, among which 15 patients were in the control group and the rest 12 were in the study group. The patients in the control group received triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% (topical application) while the patients in the study group received propolis gel. Both the groups were evaluated for pain and erythema at baseline (1st visit), first follow-up (7th day), and second follow-up (14th day) using numerical rating scale and modified oral mucositis index.

Results:

The patients in both the study and control groups showed a statistically significant reduction (P = 0.000 for the study group and P = 0.000 for the control group) in pain and erythema scores from baseline to second follow-up visit. However, on comparison of the reduction in pain and erythema scores between the two groups, the difference was found to be statistically insignificant (P = 0.255).

Statistical Analysis Used:

Chi-square and Cramer's V test were used.

Conclusion:

The topical propolis was found to be of comparative effectiveness with respect to triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% in the management of OLP.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, oral lichen planus, propolis

Introduction

The mouth is a mirror of health or disease, a guardian, or early warning system. The oral cavity is considered as a window to the body because oral manifestations accompany many systemic diseases. In many instances, oral involvement presages the appearance of other symptoms or lesions at other locations.[1]

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory, autoimmune, mucocutaneous disease of unknown etiology. The strange name of the condition was provided by the British physician Erasmus Wilson, who first described it in 1869. He named it so as the lesions on the skin looked similar to the tree mosses growing on the rocks. In Greek, “lichen” means tree moss, and in Latin, “planus” means flat.[2]

As the exact causative factor for OLP is a matter of conflict, the failure to achieve appropriate or exact treatment for it may be the reason for its incomplete regression. The first line of treatment for OLP has been corticosteroids,[3] but because of their adverse effects, alternative therapeutic approaches are being carried out.

Recently, use of natural drugs, such as propolis, has gained considerable interest. It is a sticky, resinous substance which is collected by the honey bees from the sap, leaves, and buds of plants, and then mixed with secreted beeswax.[4] It has been used in folk medicine for thousands of years and is also known as Russian penicillin.[5]

Propolis being extremely high in bioflavonoid content has antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory properties.[4] These properties have prompted investigators to check its efficacy on various oral diseases, namely lichen planus (LP), oral candidiasis, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, radiation mucositis, denture stomatitis, and herpes labialis.[6]

A study conducted in the past has obtained favorable results in the management of OLP using topical propolis.

With this background in mind, this study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of topical propolis in the management of OLP and to further strengthen the previously obtained results.

Materials and Methods

Source of data

The study participants comprised of dental outpatients visiting the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, JSS Dental College and Hospital, Jagadguru Sri Shivarathreeshwara University, Mysore.

Method of collection of data

The study sample was collected through purposive sampling. Twenty-seven individuals of either gender, satisfying the following eligibility criteria, and those willing to participate in the study were selected for the study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with clinically diagnosed atrophic/erosive OLP(based on modified WHO clinical criteria, 2003)[7]

Individuals willing to be a part of the study, who sign the informed consent form, and who find it convenient to appear for follow-ups as required by the study.

Patients who had not used systemic or topical glucocorticosteroids for at least past 2 weeks

Patients who agree not to use any other medication such as analgesics and anesthetics in either topical form or systemic form during the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients not willing to be a part of the study

Patients with lichenoid lesions thought to arise as a hypersensitivity reaction to drugs and dental materials

Patients on long-term glucocorticosteroid therapy

Pregnant and lactating female patients

Patients allergic to bee products.

The patients were informed about the study parameters, and signed informed consent was taken. The patients in the control group received triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% while the patients in the study group received 5% propolis. Patients in both the groups were instructed to apply the paste on the lesion three times a day for 15 days and were asked to refrain from eating, drinking, and rinsing for at least 30 min after topical application.

Symptom score for OLP was considered at baseline using numerical rating scale (NRS) ranging from 0 (no oral discomfort) to 10 (worst imaginable oral discomfort) [Figure 1].[8]

Figure 1.

Numerical rating scale

The clinical signs of OLP were measured at baseline using a semi-quantitative scale, modified oral mucositis index (MOMI), validated for measurement of clinical signs of OLP. An oral examination was conducted and atrophic and erosive changes were quantified based on severity and the number of sites involved. An intensity score for erythema ranging from 0 to 3 was used:

0 = normal

1 = mild erythema

2 = moderate erythema

3 = severe erythema.

The score for ulcerations was based on area of ulceration:

0 = no ulcerations

1 = between 0 and 0.25 cm2

2 = between 0.25 and 1 cm2

3= ≥1 cm2.

The following clinical parameters were assessed during follow-up:

Pain: NRS

Erythema and ulceration: MOMI

Side effects.

The patients were followed up after 7 and 15 days. Readings for all clinical parameters for each patient from baseline to subsequent visits were recorded. The patients were inquired for side effects if any.

The data were entered into the computer using Microsoft excel and were analyzed using SPSS software for windows (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

The data were tabulated and subjected to the following statistical analysis, i.e., the Cramer's V and Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Preparation of propolis

Preparation of propolis was done in the Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy, Mysore.

Chemicals used

Ethanol, starch powder, carbopol 934, triethanolamine (TEA), methylparaben, propylparaben, and peppermint oil.

Equipment used

Digital weighing balance, Magnetic stirrer, and Propeller mixer.

The propolis was cleaned using sterile hand gloves and was cut into small pieces, and 400 g of cleaned propolis was considered for the present study.

A sterilized 1000 ml beaker was filled with about 500 ml of absolute alcohol and approximately 400 g of propolis was added. It was then covered with aluminum foil which was kept in a warm dark place for 7 days to achieve complete extraction.

After 7 days, the contents in the conical flask were filtered using filter paper, and the solution was collected in a clean beaker. It was then subjected to evaporation using the magnetic stirrer to remove excess of solvent. The temperature was maintained at 40°C.

The resultant thick dark brown-colored liquid of 100 ml was collected in a clean beaker, and 500 gm of starch (99% pure) was added to remove the stickiness as well as to transform the extract to a powder form.

Then, 1% carbopol solution (2 g in 200 ml of water) was prepared separately in a sterilized beaker to which 0.40 g of methylparaben, 0.30 g of propylparaben, and 0.75 ml of peppermint oil were added and stirred continuously to get a homogeneous mixture.

The starch-mixed propolis powder extract was then added to the beaker and homogenized using propeller mixer at 250 rpm for 15 min. After that, 1 ml of TEA (neutralizing agent/thickening agent) was added to thicken the solution into a gel of desired consistency.

Finally, the preparation was packed in the preweighed sterilized aluminium tubes and sealed. It was packed in such a way that 1 aluminium tube contains 25 gm of the formulation and 1 g of the formulation consists 0.2 g of the extract. Therefore, each aluminium tube consists of 5 gm of propolis extract.

Results

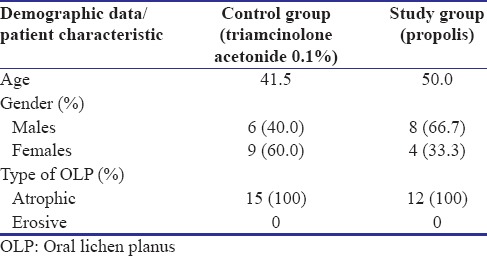

Of the 27 patients enrolled in the study, 15 were in the control group and 12 were in the study group. The patients in the control group received triamcinolone acetonide 0.1%, and the patients in the study group received propolis. They were instructed to apply the paste on the lesion three times a day for 15 days and were asked to report on the 7th and the 15th day. Demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Graph 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to age, sex, clinical characteristic, pain, and erythema scores at baseline.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the study participants and patient characteristics

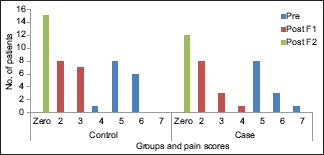

Graph 1.

Change in pain scores from baseline to first follow-up, first follow-up to second follow-up visit, and baseline to second follow-up visit in the study and control groups

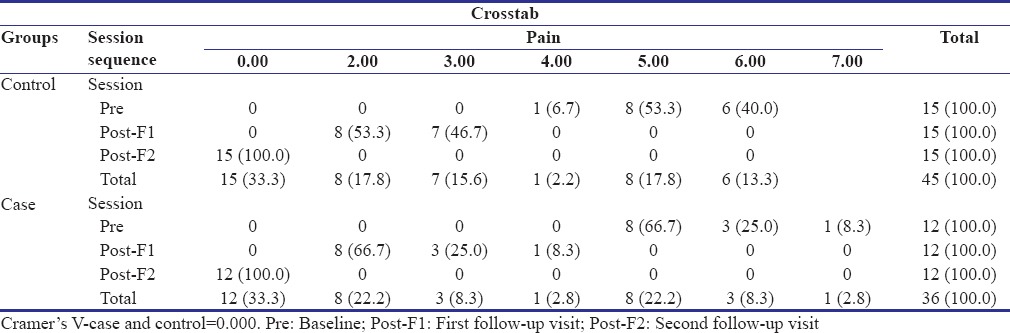

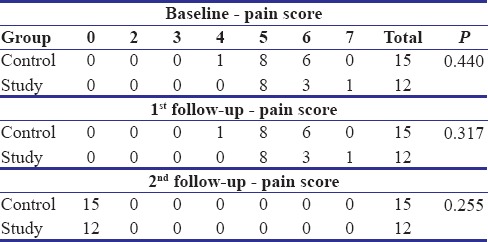

The patients in both the groups, i.e., the study group and the control group reported a complete reduction in the intensity of pain at the second follow-up visit [Table 2]. An overall statistically significant improvement in the pain scores was found from baseline to second follow-up visit in both the groups (P = 0.000), but no significant differences were observed between the two groups (P = 0.255).

Table 2.

Comparison of distribution of individuals according to the improvement in pain scores from baseline to second follow-up visit in the study and control groups

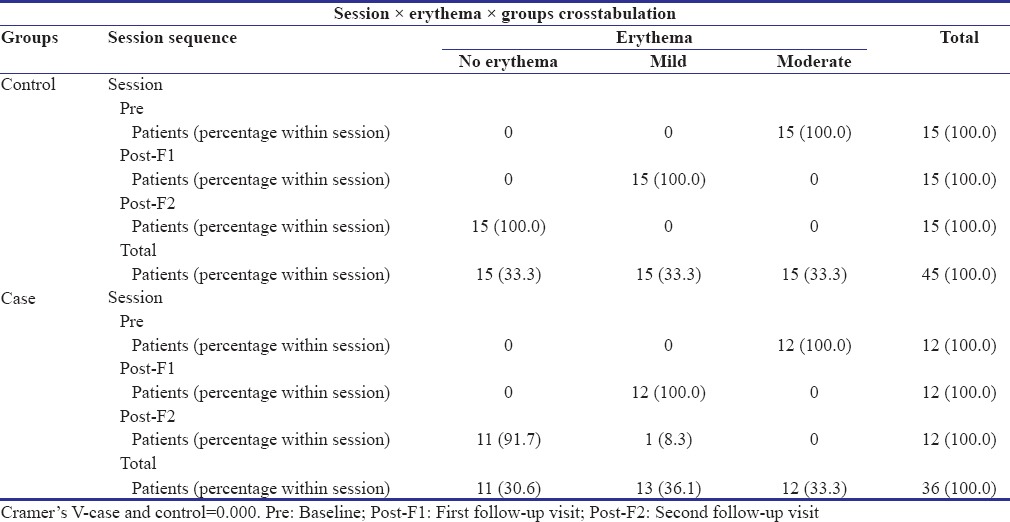

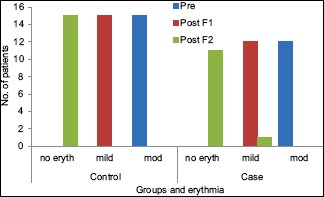

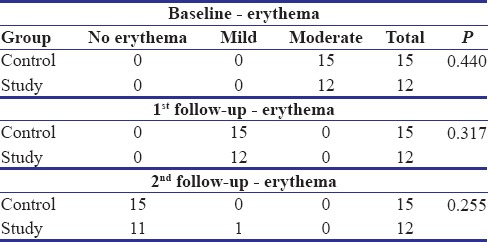

In the control group, all the patients reported complete resolution of erythema at the second follow-up visit [Table 3 and Graph 2]. An overall statistically significant improvement was found in the erythema scores in the control group patients from baseline to second follow-up visit (P = 0.000).

Table 3.

Comparison of distribution of individuals according to the improvement in erythema scores from baseline to second follow-up visit in the study and control groups

Graph 2.

Change in erythema scores from baseline to first follow-up, first follow-up to second follow-up visit, and baseline to second follow-up visit in the study and control groups

Among 12 patients in the study group, 11 patients reported complete resolution of erythema and 1 patient had a score of 1 (mild erythema). There was an overall improvement in the erythema scores which was statistically significant [Table 2]. However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups (P = 0.255).

The patients in the study and control group showed a statistically significant reduction (P = 0.000 for the study group and P = 0.000 for the control group) in the pain and erythema scores from baseline to second follow-up visit. However, on comparison of the reduction in pain and erythema scores between the two groups, the difference was found to be statistically insignificant (P = 0.255) [Table 4a and b]. In other words, an intragroup analysis showed significant differences in each group, but the intergroup analysis did not show any significant differences.

Table 4a.

Comparison of baseline, first, and second follow-up values for various parameters of study and control groups

Table 4b.

Comparison of baseline, first, and second follow-up values for various parameters of study and control groups

Discussion

LP is a chronic inflammatory, autoimmune, mucocutaneous disease of unknown etiology. As the exact causative factor for OLP is a matter of conflict, the failure to achieve appropriate or exact treatment for it may be the reason for its incomplete regression. The first line of treatment for OLP has been corticosteroids, but because of their adverse effects, alternative therapeutic approaches are being carried out.[3]

Recently, use of natural drugs, such as propolis, has gained considerable interest. It is a sticky, resinous substance which is collected by the honey bees from the sap, leaves, and buds of plants, and then mixed with secreted beeswax. It has been used extensively in ayurvedic medicine for centuries, as it has a diversity of therapeutic properties including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, antitumor, and immunomodulatory effect.[4] These properties have prompted investigators to check its efficacy on various oral diseases, namely LP, oral candidiasis, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, radiation mucositis, denture stomatitis, and herpes labialis.[9]

The role of the immune system as a primary factor in the pathogenesis of LP has become established in recent years. It is attributed to the basal layer degeneration and band-like infiltration of T lymphocytes and macrophages. T helper 1 and T helper 2 are the well-known independent subdivisions of T cells. Recently, a third “T helper” subdivision has been recognized, which plays a principal role in defense against extracellular pathogens. This subdivision of T cells controls immune and inflammatory responses through secretion of cytokines such as Interleukin 17. This family of T cells provides a new route for cooperation between innate and acquired immunity. The major role of IL-17 is to increase the expression of threatening factors for colony chemokines, metalloproteinase, and IL-6. Therefore, IL-17 is a strong stimulator for recalling, activating, and immigration of neutrophils, production of INF-alpha, IL-B from macrophages, and recalling eosinophils.[10]

In a study by Zenouz et al., it was proven that propolis administration significantly decreased IL-17 serum levels, VAS means, and the maximum lesion sizes in patients with symptomatic OLP.[11]

A study conducted by Zyada et al. also obtained favorable results in the management of OLP using topical propolis.[12]

Hence, we hypothesized that propolis could minimize the underlying inflammatory mechanism by lowering the levels of IL-17, thereby preventing the destruction of the basement membrane by the lymphocytes.

With this background in mind, this study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of topical propolis in the management of OLP and to further strengthen the previously obtained results.

The demographic pattern and clinical profile of OLP patients were also recorded in our study. According to our study, the patients were in the age group of 28–60 years and their mean age was 45.3 years which was almost similar to the study conducted by Tak, Gumru, Mostafa, and Chitturi.

The study conducted by Chitturi et al. comprised of 58 patients from the age group of 11–70 years and their mean age was 45.72 years.[13]

According to the study conducted by Mostafa and Ahmed, Tak and Chalkoo, and Gümrü, the mean age was found to be 48 years, 43 years, and 49.8 years, respectively.[14,15,16]

In the present study, the mean age was 45.3 years which was more than the mean age reported by Keshari et al. and Munde et al. and lower than the mean age reported by Ingafou et al., Gandolfo et al., and Xue et al. This variation might be due to the difference in ethnicity and geographic locations.[17,18,19,20,21]

The mean age group reported by Keshari et al., Munde et al., Ingafou et al., Gandolfo et al., and Xue et al. was 39.9 years, 36.9 years, 50.4 years, 52 years, and 56.7 years, respectively.

According to our study, no sex predilection (male: female – 1.08:1) was noted which was similar to the studies conducted by Chitturi et al., Ingafou et al., Lacy et al., and Anjum et al. where the male to female ratio was found to be 1:1.[21,22]

Many studies claim that OLP is more predominant in females as they are more prone to stress and hormonal imbalance. However, in our study, we observed an equal distribution between males and females and this might be due to the small sample size as compared to other studies.

In the studies conducted by Munde et al., Tak and Chalkoo, and Chitturi et al., the most common symptomatic form of LP was the erosive form. However, in the present study, the atrophic form was found to be more prevalent which is similar to a study conducted by Keshari et al. This variation could be due to the smaller sample size.[13,15,18]

The most common site where OLP was seen in our study was in the buccal mucosa, followed by gingiva. This is in accordance with the studies conducted by Tak and Chalkoo, Munde et al., and Mostafa and Ahmed.[14,15,19]

The study conducted by Chainani-Wu et al. has reported that more than one mucosal surface can be involved which is in accordance with our study wherein a combination of gingiva and buccal mucosa was seen.[23]

In the present study, the patients in both the groups, i.e., the study group and the control group reported a complete reduction in the intensity of pain at the second follow-up visit. An overall statistically significant improvement in the pain scores was found from baseline to second follow-up visit in both the groups, but no significant differences were observed between the two groups. In other words, an intragroup analysis showed significant differences in each group, but the intergroup analysis did not show any significant differences.

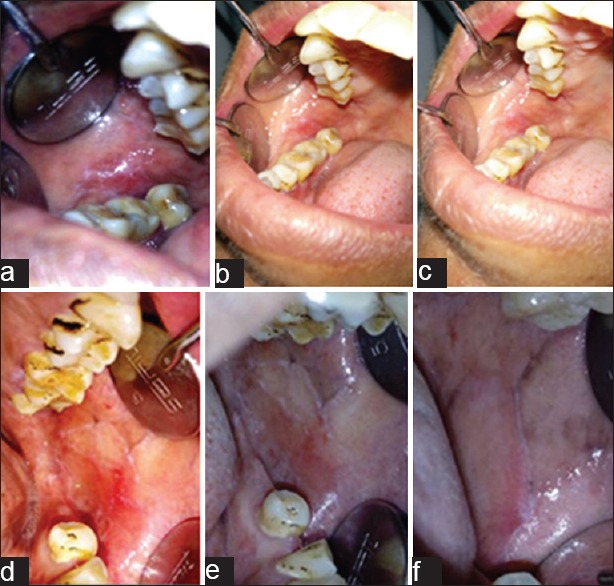

In the control group, all the patients reported complete resolution of erythema at the second follow-up visit. An overall statistically significant improvement was found in the erythema scores in the control group patients from baseline to second follow-up visit [Figure 2a–c].

Figure 2.

(a) Patient with atrophic lichen planus at baseline visit included in the study group. (b) Reduction in severity of erythema following treatment with propolis at first follow-up visit. (c) Further reduction in erythema at the second follow-up visit. (d) Patient with atrophic lichen planus at baseline visit included in the control group. (e) Reduction in severity of erythema following treatment with triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% at first follow-up visit. (f) Further reduction in erythema at the second follow-up visit

Among 12 patients in the study group, 11 patients reported complete resolution of erythema and 1 patient had a score of 1 (mild erythema). There was an overall improvement in the erythema scores which was statistically significant. However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups [Figure 2d–f].

The result of our study is comparable to the study conducted by Zydaa et al. to evaluate the efficacy of propolis in the management of LP. They also proved that propolis showed to be a promising pharmacological agent for inhibiting epithelial cell proliferation and has anti-inflammatory effect.[12]

According to our study, propolis is comparative in its efficacy to corticosteroids. It must be enunciated that topical propolis does not accord any adverse effects, unlike topical corticosteroids. Chiefly, the fatalistic effects demonstrated in topical steroid use such as oral candidiasis, mucosal atrophy, telangiectasia, hypersensitivity reactions, hypopigmentation, and delayed wound healing were eliminated in topical propolis use.[24]

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to be conducted using propolis obtained from South Asia as a topical preparation in the management of OLP. Considering its safety, wide availability, and low cost, propolis could be a novel alternative therapeutic modality in the management of inflammatory conditions such as OLP.

Limitations and future recommendation

A major limitation of this study was the small sample size. A larger sample size would have allowed for stronger statistical analysis. Another limitation of the study was the dependence on patient's compliance which could not be monitored. Furthermore, since the patients were followed up only till 14 days, the recurrence rate of LP could not be elicited.

Future studies can be conducted using a larger sample size to further authenticate the effectiveness of propolis. A longer follow-up period will help in demonstrating a difference in the recurrence rate of LP among the study and the control groups.

Conclusion

The current study comprised of 27 patients diagnosed with OLP, among which 15 patients were in the control group and the rest 12 were in the study group. The patients in the control group received triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% while the patients in the study group received 5% propolis. Both the groups were evaluated for pain and erythema at baseline (1st visit), first follow-up (7th day), and second follow-up (14th day).

The following conclusions were drawn: the topical propolis was found to be as effective as triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% in the management of OLP. It has both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, which may significantly contribute to its clinical effects.

No adverse reactions were noted with the use of topical propolis, and it was also found to be effective at the prescribed dose, i.e., 5% propolis.

Considering the chronicity of the disease and the need for the long-term treatment modalities, propolis can be proposed as a better treatment modality for OLP.

Considering the safety, wide availability, and low cost, propolis should be considered as a novel alternative therapeutic modality in the management of OLP. Hence, we conclude that our results provided practical hints for the better management of OLP. However, more research with larger sample size is necessary for a full evaluation of the efficacy of propolis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mehrotra V, Devi P, Bhovi TV, Jyoti B. Mouth as a mirror of systemic diseases. Gomal J Med Sci. 2010;8:235–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudhia BB, Dudhia SB, Patel PS, Jani YV. Oral lichen planus to oral lichenoid lesions: Evolution or revolution. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015;19:364–70. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.174632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burket L, Greenberg M, Glick M, Ship J. Hamilton, Ont: BC Decker; 2008. Burket's Oral Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagh VD. Propolis: A wonder bees product and its pharmacological potentials. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2013;2013:308249. doi: 10.1155/2013/308249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuropatnicki AK, Szliszka E, Krol W. Historical aspects of propolis research in modern times. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:964149. doi: 10.1155/2013/964149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arshiya Ara S, Ashraf S, Arora V, Rampure P. Use of apitherapy as a novel practice in the management of oral diseases: A review of literature. J Contemp Dent. 2013;3:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Meij EH, van der Waal I. Lack of clinicopathologic correlation in the diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on the presently available diagnostic criteria and suggestions for modifications. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:507–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chainani-Wu N, Silverman S, Jr, Reingold A, Bostrom A, Lozada-Nur F, Weintraub J. Validation of instruments to measure the symptoms and signs of oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain S, Gupta RR, Sharma V, Batra M. Propolis in oral health: A natural remedy. World J Pharm Sci. 2014;2:90–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pouralibaba F, Babaloo Z, Pakdel F, Aghazadeh M. Serum level of interleukin 17 in patients with erosive and non erosive oral lichen planus. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2013;7:91–4. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2013.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zyada MM, El-Said Elewa M, El-Meadawy S, El-Sharkawy H. Effectiveness of topical mucoadhesive gel containing propolis in management of patients with atrophic and erosive oral lichen planus: Clinical and immunohistochemical study. Egypt Dent Assoc. 2012;58:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zenouz TA, Mehdipour M, Abadi RT, Shokri J, Rajaee M, Aghazadeh M, et al. Effect of use of propolis on serum levels of il-17 and clinical symptoms and signs in patients with ulcerative oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119:166–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chitturi RT, Sindhuja P, Parameswar RA, Nirmal RM, Reddy BV, Dineshshankar J, et al. Aclinical study on oral lichen planus with special emphasis on hyperpigmentation. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:S495–8. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.163513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mostafa B, Ahmed E. Prevalence of oral lichen planus among a sample of the Egyptian population. J Clin Exp Dent. 2015;7:e7–e12. doi: 10.4317/jced.51875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tak MM, Chalkoo AH. Demographic, clinical profile of oral lichen planus and its possible correlation with thyroid disorders: A case-control study. Int J Sci Stud. 2015;3:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gümrü B. A retrospective study of 370 patients with oral lichen planus in turkey. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:e427–32. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keshari D, Patil K, Mahima VG. Efficacy of topical curcumin in the management of oral lichen planus: A randomized controlled-trial. J Adv Clin Res Insights. 2015;2:197–203. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munde AD, Karle RR, Wankhede PK, Shaikh SS, Kulkurni M. Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus: A retrospective study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:181–5. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.114873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingafou M, Leao JC, Porter SR, Scully C. Oral lichen planus: A retrospective study of 690 British patients. Oral Dis. 2006;12:463–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandolfo S, Richiardi L, Carrozzo M, Broccoletti R, Carbone M, Pagano M, et al. Risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma in 402 patients with oral lichen planus: A follow-up study in an Italian population. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacy MF, Reade PC, Hay KD. Lichen planus: A theory of pathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;56:521–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anjum R, Singh J, Kuduva S. A clinicohistopathologic study and probable mechanism of pigmentation in oral lichen planus. World J Dent. 2012;3:330–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chainani-Wu N, Silverman S, Jr, Lozada-Nur F, Mayer P, Watson JJ. Oral lichen planus: Patient profile, disease progression and treatment responses. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:901–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta M, Pawar CP, Gupta M. Topical corticosteroids: Applications in dentistry. Santosh Univ J Health Sci. 2015;1:99–101. [Google Scholar]