Abstract

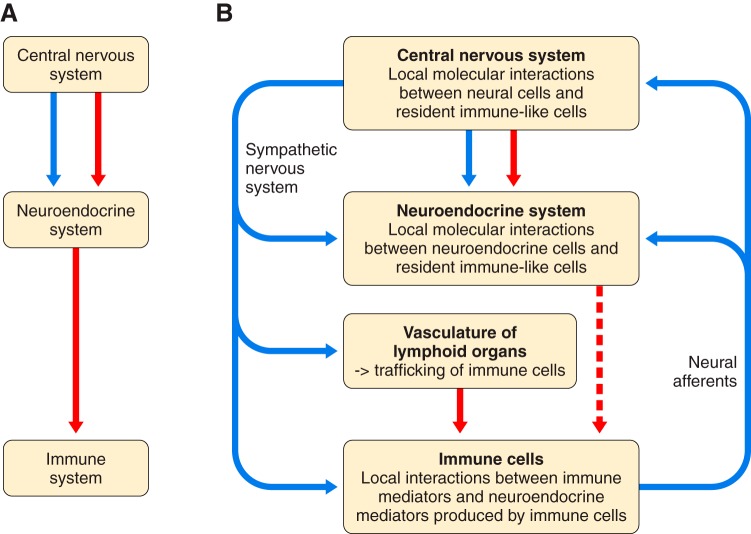

Because of the compartmentalization of disciplines that shaped the academic landscape of biology and biomedical sciences in the past, physiological systems have long been studied in isolation from each other. This has particularly been the case for the immune system. As a consequence of its ties with pathology and microbiology, immunology as a discipline has largely grown independently of physiology. Accordingly, it has taken a long time for immunologists to accept the concept that the immune system is not self-regulated but functions in close association with the nervous system. These associations are present at different levels of organization. At the local level, there is clear evidence for the production and use of immune factors by the central nervous system and for the production and use of neuroendocrine mediators by the immune system. Short-range interactions between immune cells and peripheral nerve endings innervating immune organs allow the immune system to recruit local neuronal elements for fine tuning of the immune response. Reciprocally, immune cells and mediators play a regulatory role in the nervous system and participate in the elimination and plasticity of synapses during development as well as in synaptic plasticity at adulthood. At the whole organism level, long-range interactions between immune cells and the central nervous system allow the immune system to engage the rest of the body in the fight against infection from pathogenic microorganisms and permit the nervous system to regulate immune functioning. Alterations in communication pathways between the immune system and the nervous system can account for many pathological conditions that were initially attributed to strict organ dysfunction. This applies in particular to psychiatric disorders and several immune-mediated diseases. This review will show how our understanding of this balance between long-range and short-range interactions between the immune system and the central nervous system has evolved over time, since the first demonstrations of immune influences on brain functions. The necessary complementarity of these two modes of communication will then be discussed. Finally, a few examples will illustrate how dysfunction in these communication pathways results in what was formerly considered in psychiatry and immunology to be strict organ pathologies.

I. INTRODUCTION

Our understanding of physiology has benefited greatly from the advances in molecular biology that have been at the origin of the explosive development of genetics and -omic techniques. What used to be a rarity a few decades ago, studying the expression and function of a given molecule within a different physiological system from the one in which it was first identified, has now become the norm. Communication signals and signaling pathways are commonly studied in different physiological systems using the same tools. This is the case, for instance, for purinergic signaling, which is investigated by immunologists for its role in macrophage function and plasticity (57) and by neurobiologists for its regulatory activity on synaptic plasticity (203). Blurring of the boundaries between disciplines is probably the main outcome of this wave of research. However, this situation is still relatively new, and the transition to it has been very progressive.

This is well reflected in the history of the research efforts in neural–immune interactions (TABLE 1) (1). What was initially of interest to only a few practitioners in psychosomatic medicine—the influence of personality factors and emotional states on sensitivity to disease, or more generally the interrelationships among mind, body, and environment in health and disease—became an object of scientific investigation in the 1950s, when it was brought into the laboratory to be subjected to a reductionist approach (139). Not surprisingly, retrospectively, but at the time difficult for hardcore pathologists to admit, biobehavioral factors, in the form of exposure to well-defined stressors, were found to influence the initiation and progression of various infectious and noninfectious diseases in animal models of pathology. Once it became possible to assess immune functions in a routine manner using techniques borrowed from clinical immunology, these influences were ascribed to modulation of immune responses by activation of the stress pathways. The predominant stress pathways that were investigated were the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the activation of which results in the release of cortisol or corticosterone (depending on the species), and the sympathetic nervous system, the activation of which results in the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine.

Table 1.

The early decades of research that shaped the field of neuroimmune interactions

| Early Neuroimmune Research |

|---|

| 1. The psychosomatic approach: |

| Psychological factors and emotions influence disease onset and progression (allergies, peptic ulcer, cancer, autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases) |

| 2. The biobehavioral approach: |

| Experimental stressors impact immune functions (1964: Solomon proposes the term “psychoimmunology”) |

| The immune system can be modulated by conditioned stimuli (Metalnikov and Chorine, 1926; Ader, 1974) |

| 3. The cellular communication approach: |

| Immune cells express neurotransmitter receptors (Szentivanyi, 1958; Hadden, 1970–5; Pert, 1985) |

| Immune cells produce brain and pituitary peptides (Blalock, 1980) |

| 4. The neuroanatomical approach: |

| Innervation of the spleen and other lymphoid organs by the autonomic nervous system (Felten, 1980) |

| 5. The effect of immune factors on the neuroendocrine system: |

| Interleukin-1 activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by acting in the brain (Besedovsky and Del Rey, 1975) |

The study of psychological modulation of immunity, initially conducted at Institut Pasteur in Paris, France in the 1920s using Pavlovian conditioned stimuli (157), was revived in the 1970s by Ader and Cohen (2), who rediscovered the phenomenon of conditioned immunosuppression. Working at the University of Rochester Medical Center, they showed that it is possible to increase the immunosuppressive effect of cyclophosphamide by presenting rats with the taste of a saccharin solution previously paired with exposure to the poisonous side effects of cyclophosphamide (2). These were key experiments that indirectly revealed the existence of an intricate network of bidirectional communications between the central nervous and the immune systems. Such communication pathways had been suspected before but not yet demonstrated. Therefore, they were not amenable to mechanistic analysis.

The field of research that studies the basic aspects of neural–immune interactions was variously labeled neuroimmunomodulation, neuroimmunoendocrinology, or psychoneuroimmunology, depending on which scientific discipline predominated at the time. However, this new wave of interdisciplinary research gained momentum in the scientific community at large only when the pathways of communication between the nervous system and the immune system were elucidated. In a nonconcerted effort, neuroanatomists demonstrated the existence of a sympathetic innervation of primary and secondary lymphoid organs (71), neuroendocrinologists described the expression and function of neuroendocrine receptors on immune cells (95, 177), and cell biologists showed that activated immunocytes express and release molecular factors previously identified in the neuroendocrine system, such as adrenocorticotrophin, which is processed from proopiomelanocortin in lymphocytes in the same manner as in the anterior pituitary (212, 213). The emphasis on brain-to-immune, rather than immune-to-brain, communication pathways was mainly due to the active involvement of neuroendocrinologists in the field and to the progress made in the elucidation of the chemical nature and receptor mechanisms of most neuroendocrine factors (93).

Although the existence of an immune-to-brain communication pathway had been inferred by Besedovsky et al. (17), whose elegant physiological studies demonstrated activation of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system during the peak antibody response in mice vaccinated with a T-cell antigen, the molecular nature of this communication pathway took longer to be elucidated. Cloning and recombinant expression of cytokines, the autocrine and paracrine communication factors between immune cells, did not take place before the early 1980s (60). The ability of the first cloned cytokine interleukin (IL)-1β to activate the HPA axis and induce some of the physiological changes observed in a mouse model of antibody response to sheep red blood cells was reported in 1986, shortly after the demonstration of the pyrogenic activity of this cytokine (16).

As previously presented in Physiological Reviews, basic communication mechanisms between the nervous and immune systems include the immune production and function of neuroendocrine peptide hormones (22), the effects of neuroendocrine hormones on the immune system and the innervation of lymphoid organs by the sympathetic nervous system (142), and the regulatory effects of cytokines on the HPA axis (232). The objective of this review is not to update this information but to introduce a new perspective: the fascinating complementarity between short-range and long-range communication mechanisms between the nervous and the immune systems.

Studies of long-range communication mechanisms were initially favored, certainly because of the strong predominance of neuroendocrinology and neuroanatomy in the emerging field of psychoneuroimmunology. Communication from the nervous system to the immune system was believed to take place exclusively via circulating hormones produced by the neuroendocrine system (e.g., cortisol, but also growth hormone and prolactin) and via neurotransmitters (e.g., epinephrine and norepinephrine) released in the vicinity of immune cells by nerve endings in primary and secondary lymphoid organs. However, the discovery that immune cells can themselves produce and release neuroendocrine factors and neuromediators led to a shift in interest from long-range to short-range communication pathways.

Similarly, communication from the immune system to the brain was initially seen as involving circulating immune factors acting indirectly on the brain via the formation of brain-penetrant molecules (prostaglandins) in brain areas where the blood-brain barrier is leaky, the so-called circumventricular organs. This was how endogenous pyrogens were perceived as being responsible for the development of the fever response to infectious pathogens. It took time for neurobiologists to realize that brain innate immune cells actually produce the same cytokines as those originally characterized as endogenous pyrogens and that these locally produced cytokines are responsible for the various components of the response of the host to infection. It took even longer to recognize that cytokines produced locally by brain cells are responsible for intricate functional and structural interactions between endothelial cells, glia, and neurons.

II. NEURAL AND HORMONAL INFLUENCES ON THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

A. Innervation of Lymphoid Organs: Sympathetic Versus Parasympathetic Innervation

There is much anatomic and functional evidence for a role of the autonomic nervous in the regulation of immunity (142). Most of the neuroanatomical studies on innervation of lymphoid organs were carried out during the 1970s–1980s. They revealed the existence of a dense sympathetic innervation of all lymphoid organs. Sympathetic nerves travel with the vasculature but separate from it when entering lymphoid organs. They terminate in close contact with parenchymal T lymphocytes and plasma cells, forming what has been termed “neuroeffector junctions” (71). The nerve fibers that innervate lymphoid organs contain various neuropeptides that are colocalized or not with norepinephrine, including vasoactive intestinal peptide, neuropeptide Y, substance P, Met-enkephalin, and neurotensin.

Most peripheral organs in the body are innervated by branches of both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems. The immune system is apparently an exception: no neuroanatomical evidence exists for a parasympathetic or vagal nerve supply to any immune organ, with the possible exception of lymphoid tissue in the respiratory and alimentary tracts (164). This is in contrast to results from earlier tracing studies of innervation (37), which were subsequently corroborated by visualization of the synthesizing enzyme choline-O-acetyltransferase and the degradation enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which act on the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (36). However, these observations were dismissed because of the presence of artifacts in the tracing studies that were caused by the spillover of large doses of tracers (142, 164) and the existence of a nonneuronal acetylcholine expression system in lymphocytes (79). Lymphocytes contain all the components required to constitute an independent, nonneuronal cholinergic system, including acetylcholine, its synthesizing and degrading enzymes, and muscarinic and cholinergic receptors. The fact that expression of the components of this nonneuronal cholinergic system varies during T-cell activation as well as in response to cholinergic agents indicates that acetylcholine synthesized by T cells can act as an autocrine or paracrine factor (115).

The possibility of a parasympathetic innervation of lymphoid organs was reexamined recently, thanks to a new neural-tract tracing methodology based on specific labeling of choline acetyltransferase-expressing cells by the tdTomato fluorescent protein, which can be utilized in appropriate transgenic lines of mice (81). Cholinergic innervation emanating from enteric neurons was apparent only in the intestinal lamina propria of the gastrointestinal tract. Cholinergic fibers were found to come in close contact with macrophages, plasma cells, and lymphocytes located in the intestinal mucosa, and to a lesser degree with immune cells within the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Cholinergic innervation of the spleen is very sparse and comes from a small subset of cholinergic sympathetic postganglionic neurons located in the paravertebral and/or prevertebral chains. These fibers are often associated with periarteriolar catecholaminergic fibers. A few of them terminate in lymphocyte-containing areas of the white pulp. Nonneuronal choline acetyltransferase cells are clearly visible in the spleen and consist mainly of B cells and fewer T cells.

Another factor of confusion in the identification of cholinergic innervation of lymphoid organs is the existence of a catecholaminergic-to-cholinergic transmission switch in some sympathetic fibers influenced by signals, such as leukemia inhibitory factor, produced by the innervated target. Although this is a marginal phenomenon, it has been described in particular for the sympathetic fibers that innervate sweat glands in mammalian footpads (69) and the periosteum (6). Because the density of catecholaminergic neurons that innervate inflamed tissue decreases in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the possibility of a catecholamine-to-cholinergic transition of sympathetic nerve fibers was investigated in a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis. Cholinergic sympathetic fibers became apparent several weeks after the induction of arthritis under the influence of leukemia inhibitory factor. However, catecholaminergic-to-cholinergic transition only affected those fibers that innervate healthy tissue adjacent to the inflammatory tissue (217).

The remarkable saga of the anti-inflammatory cholinergic reflex proposed by Kevin Tracey in the 2000s illustrates very well the various ingredients of the controversy about the parasympathetic innervation of lymphoid organs (171). The saga began with the discovery of unexpected pharmacological properties of a new anti-inflammatory drug developed by Tracey for the treatment of sepsis, tetravalent guanylhydrazone (CNI-1493). CNI-1493 was developed on the basis of its ability to inhibit the production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) and other macrophage inflammatory cytokines in response to sepsis induced by administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Tracey discovered that this lead compound was much more potent when injected into the lateral ventricle of the brain than when administered systemically (29). This finding was interpreted to indicate that CNI-1493 activates a neural pathway that links the brain to peripheral macrophages. This neural pathway was claimed to be the vagus nerves, as cutting the vagus nerves abrogated the anti-inflammatory activity of CNI-1493, whereas electrically stimulating the peripheral end of vagal nerves mimicked it (30).

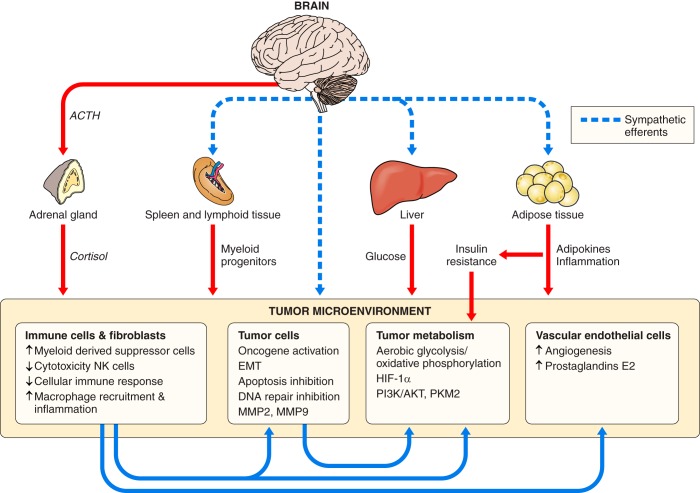

Indifferent to the controversies surrounding the possible existence of a parasympathetic innervation of lymphoid organs, Tracey (231) proposed that cholinergic vagal nerves act on macrophages to suppress the production of TNF and other inflammatory mediators. This neural communication pathway from the central nervous system to the immune system was presented as being part of an anti-inflammatory reflex whose afferent arm was the production of inflammatory cytokines by activated innate immune cells (see sect. III) and whose efferent arm was the activation of cholinergic efferents downregulating cytokine production by innate immune cells (FIGURE 1). Muscarinic cholinergic stimulation was proposed to mediate the central component of the anti-inflammatory pathway, whereas activation of nicotinic receptors containing an α7 receptor subunit mediated the downregulatory effect of acetylcholine on macrophages (242). What was still lacking in the characterization of this anti-inflammatory pathway, however, was an anatomically characterized target for the efferent vagal innervation (137).

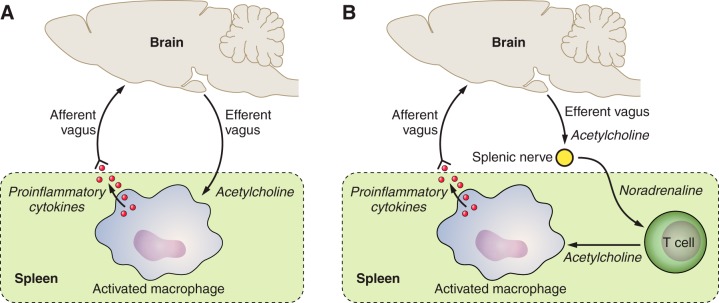

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the inflammatory reflex. A: the initial model of the inflammatory reflex that was proposed originally by Tracey (231). Proinflammatory cytokines released by activated innate immune cells activate the afferent vagus nerves. This sensory input activates in a reflex-like manner neuronal cell bodies of the efferent vagus nerves. The resulting activation of the dorsal vagal complex recruits the efferent cholinergic vagus nerves that downregulate inflammation. B: the revised model of the inflammatory reflex. The parasympathetic branch of the vagus nerves activates the splenic nerves. Activation of this sympathetic nerve results in the recruitment of acetylcholine-producing T cells that downregulate inflammation.

This target was proposed to be the spleen, as sectioning of the splenic nerves abrogated the anti-inflammatory signature of splenic macrophages that developed in response to vagal nerve stimulation (107). In the absence of a direct cholinergic innervation of the spleen, these findings were interpreted to indicate that sympathetic postganglionic splenic nerves indirectly transmitted the cholinergic vagal message to splenic macrophages (192). The problem was that this neuroanatomic circuit implied an adrenergic, instead of cholinergic, transmission of the neural message to macrophages. The missing cholinergic link surfaced later, with the discovery that T cells that produce and release acetylcholine in the spleen could be called to the rescue (FIGURE 1) (193). Microdialysis of the spleen and mass spectrometry analysis of the dialysate samples were used to demonstrate that vagus nerve stimulation leads indirectly to the release of acetylcholine in situ. The lack of an effect of vagus nerve stimulation in nude mice lacking T cells, together with adoptive transfer experiments of acetylcholine containing T cells to nude mice, confirmed the role of T lymphocytes in the anti-inflammatory reflex. Still missing was a demonstration that acetylcholine-containing T cells expressed β2-adrenergic receptors and were located in close proximity to sympathetic splenic nerves. This was subsequently confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis of spleen sections in mice expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein under the control of transcriptional regulatory elements for choline acetyltransferase (193).

Whether this last element of the puzzle puts a triumphant final brick on the saga of the anti-inflammatory reflex (171) is not yet certain. The existence of an indirect vagal innervation of the spleen by splenic nerves has been disputed, because vagal preganglionic neurons do not synaptically connect to sympathetic postganglionic neurons, and vagal nerve stimulation does not recruit splenic neurons (33). These last negative findings are in accordance with the features of the very sparse cholinergic innervation of the spleen described above (81). An alternative is that stimulation of the vagus nerves actually recruits lymphocytes, including acetylcholine-synthesizing cells, from the lymphoid tissue of the gut that is innervated by vagal nerves. These T cells would then be able to migrate to various organs, including the spleen (148), and exert there their local anti-inflammatory activity. As pointed out by Besedovsky a few decades ago, immune-cell trafficking and recirculation require a tight control of blood supply to lymphoid organs, including the spleen. Interactions between locally produced cytokines and sympathetic nerve fibers contribute to this control (187, 188). During sepsis that drives the inflammatory reflex, as studied by Tracey, there is a dramatic increase in splenic blood flow. This increase is secondary to an inhibition of the sympathetic vasoconstrictor tonus at the postganglionic and prejunctional levels. This results in a decrease in the release of norepinephrine, and possibly other neuromediators, by sympathetic nerve fibers in response to locally produced IL-1β (187). In other terms, nerve-driven changes in functionality of immune cells in vivo could well be due to cytokine-induced alterations in the blood supply of the lymphoid organ under investigation, especially when this lymphoid organ is devoid of lymphatic circulation, which is the case with the spleen. This observation necessitates reexamination of the importance of sympathetic nerve endings in controlling immune cell trafficking, circulation, and homing.

In conclusion of this section, innervation of the lymphoid organs is predominantly sympathetic. Parasympathetic innervation of lymphoid organs appears to be limited to the gut lymphoid tissue. The possibility that innervation regulates immune cell functionality by modulating blood supply of lymphoid organs requires further investigation.

B. Influences of Catecholamines on Immune Cells

Innate immune cells express the β2, α1, and α2 subtypes of adrenergic receptors, whereas adaptive immune cells express primarily the β2 subtype of adrenergic receptor (164). Activation of β2-adrenergic receptors triggers a signaling cascade involving the formation of cAMP, which activates either protein kinase A (PKA) or the guanine exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (EPACs) (124). PKA signals via cytoplasmic kinases such as p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) or the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) transcription factor. EPACs further signal via the Rap family of small Ras-like GTPases. Ligation of the β2 adrenergic receptor can also activate β-arrestins that connect to multiple signaling pathways, including p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase MAPKs, and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB).

Not surprisingly, an abundant literature describes the in vitro effects of various adrenergic receptors agonists and antagonists on immune cells and the signaling pathways involved in these effects. For adaptive immunity, most of the research effort has focused on the consequence of activating β2-adrenergic receptors in CD4+ T cells, Th1, and B cells. Th2 cells do not express β2-adrenergic receptors, at least in the mouse system. Stimulation of β2-adrenergic receptors usually inhibits T-cell responses, although activation effects have also been described. For instance, in vitro exposure of CD4+ T cells to norepinephrine or terbutaline decreased IL-2 production in response to polyclonal activation with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (185). However, norepinephrine also promoted naive CD4+ T-cell differentiation into Th1 cells that produced more interferon (IFN)-γ than did nonexposed cells (224). In vivo studies show that chemical sympathetic denervation decreases the intensity of delayed-type hypersensitivity, confirming a positive role of catecholamines in Th1 cell-driven immune responses (143). In B cells, the signaling pathway activated by β2-adrenergic receptor activation involves a PKA-dependent, CREB-mediated pathway that converges with that activated by CD86 ligation to enhance the magnitude of an immunoglobulin (Ig) G1 response. Activation of β2-adrenergic receptors also enhances the IgE response but via a PKA-dependent, hematopoietic tyrosine phosphatase/p38 MAPK-mediated pathway (173).

Because macrophages and monocytes express α1-adrenergic, α2-adrenergic, and β2-adrenergic receptors, their response to adrenergic stimulation is more complex. In general, the production of inflammatory cytokines is inhibited by β2-adrenergic receptor activation, whereas it is enhanced by α1-adrenergic or α2-adrenergic receptor stimulation (108, 110, 173, 215). However, adrenergic stimulation also promotes myeloid cell recruitment and migration to the site of injury, such that β2-adrenergic receptor antagonism might be beneficial. This is the case, for instance, in mice submitted to repeated episodes of social defeat. Activation of β2-adrenergic receptors facilitates the recruitment and trafficking of monocytes to the brain, resulting in prolonged activation of microglia and development of anxiety-like behavior (250).

It is important to note that this effect of β2-adrenergic receptor activation on egress of monocytes from the bone marrow is opposite to that observed on egress of lymphocytes from lymph nodes (163). In the latter case, β2-adrenergic receptor activation actually enhances retention of lymphocytes into lymphoid organs via chemokine receptors (CC-chemokine receptor 7 for B cells and CXC-chemokine receptor type 4 for T cells). Catecholamines acting on endothelial cell adhesion molecules and chemokines produce a similar dissociation in the modulation of the innate and adaptive immune system during the dark-light cycle. This dissociation is orchestrated by molecular clocks via adrenergic nerves (155, 202). Periods of activity associated with high adrenergic tone are characterized by increased recruitment of myeloid cells in tissues and sequestration of lymphocytes from general circulation into lymphoid organs. As proposed by Scheiermann et al. (202), this would help the innate immune system to be prepared for higher risk of infection during the active phase of the cycle while keeping the adaptive immune system at bay.

In addition to serving as coordination molecules between physiological and immune processes when released from autonomic nerves, catecholamines can serve other roles when produced locally (134). Epinephrine and norepinephrine are produced and released by normal T cells and exert their functions in an autocrine or paracrine manner via classic adrenergic receptors on T cells. Lymphocytes contain the machinery to synthesize and degrade catecholamines, and they produce and release more catecholamines when activated (147, 182). This is particularly the case in lymphocytes from the mesenteric lymph nodes (182), where catecholamines modulate lymphocyte trafficking, local vascular perfusion, cytokine production, and functional activity of lymphocytes.

Phagocytic cells (macrophages and neutrophils) also are able to release high levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine when activated. This is associated with enhanced expression of catecholamine synthesizing and degrading enzymes (73). Blockade of α2-adrenoreceptors, but not β2-adrenoreceptors, in a model of inflammation-induced lung injury reduced the intensity of vascular leakage, whereas administration of an α2-adrenergic agonist had the opposite effect. Experiments showing that depletion of T cells and administration of reserpine to achieve sympathetic denervation did not alter the effects of α2-adrenergic agents eliminated the possibility that T cells or sympathetic innervation produce these effects. In addition, blockade of tyrosine hydroxylase or dopamine-β-hydroxylase diminished the inflammatory response, whereas inhibition of the catecholamine-O-methyl transferase enzyme increased lung injury. These results were interpreted by the authors to suggest that the phagocytic system can function as a diffusely expressed adrenergic organ. Enhancement of the local inflammatory response by phagocyte-produced catecholamines was found to be mediated by increased production of inflammatory mediators via activation and translocation of NF-κB (74).

C. Glucocorticoids

1. Anti-inflammatory versus proinflammatory activity of glucocorticoids

In line with the original observation by Selye of an involution of the thymus and other lymphoid organs in response to stress (205) and the subsequent demonstration of the immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids (101), glucocorticoids have traditionally been seen as the hormonal mediators of the immunosuppressive effects of stressors. We will not delve into the details of the vast literature on the effects of stress on immunity, as this topic has been reviewed on several occasions and it is not directly relevant to the present review (3, 9, 160, 169, 204, 220).

Glucocorticoids act on their cellular targets by binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs). GRs normally reside in the cytosol in the form of a protein complex that brings together heat-shock proteins and FK506 binding protein 52. Upon binding to their ligand, GRs dissociate from this complex to form monomers or dimers and translocate to the nucleus The anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids are mediated by transcriptional repression following nuclear translocation and tethering of monomeric GRs to the glucocorticoid-response elements of transcription factors such as NF-κB, activator protein (AP)-1, and IFN-regulating factor-3 (234). This results in the downregulation of genes coding for inflammatory mediators, enzymes, and adhesion molecules. Although the hypothesis is still controversial, GR dimerization and transactivation are thought to play an important role in the anti-inflammatory activity of glucocorticoids. This phenomenon is illustrated by data obtained in GR(dim/dim) mutant mice that show reduced GR dimerization and increased sensitivity to TNF-induced inflammation, and to experimental models of sepsis induced by LPS or cecal ligation and puncture (123, 235).

Glucocorticoids can be proinflammatory under certain conditions. This effect can be secondary to the selection of corticoid-resistant inflammatory cells, such as pathogenic Th17 cells that overexpress IL-23 receptor and multidrug-resistance protein and that are found in inflamed gut tissue from patients with Crohn’s disease (186). The proinflammatory effect of glucocorticoids may also result from inhibition of the production and release of anti-inflammatory factors, or conversely from enhanced production and release of proinflammatory mediators. In the first case, dexamethasone administered 24 h before LPS was found to enhance the placenta’s proinflammatory cytokine response to LPS as a consequence of the inhibition of lipoxin A4 synthesis (255). In the second case, it is the dose of glucocorticoids that makes the difference: as mentioned above, physiological glucocorticoid levels can be proinflammatory in some circumstances, whereas high or pharmacological levels are anti-inflammatory. For instance, low doses of glucocorticoids increase the production of macrophage migration inhibitory factor, and this effect is sufficient to override glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of cytokine production and release by LPS-stimulated monocytes (39).

The proinflammatory effects of endogenous levels of corticosteroids have been demonstrated in the brain (214). As in the placenta, these effects are observed only if the glucocorticoid response occurs ahead of the inflammatory stimulus. Maier and his colleagues (76) have repeatedly observed that acute or chronic exposure to stressors 24 h before administration of LPS sensitizes or primes the inflammatory response to LPS. This priming effect is observed not only in peripheral macrophages (112), but also in microglia isolated from the hippocampus of stressed rats (75). The microglial release of high-mobility group box-1 (HMGB1), an endogenous damage-associated molecular pattern, has been proposed to mediate stress-induced priming via activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 and recruitment of the NLRP3 inflammasome (77).

2. Autocrine/paracrine signaling by extra-adrenal glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are considered to be prototypical hormonal factors that are produced and released into the general circulation by the adrenal cortex to act on distant target organs. The discovery of extra-adrenal production and release of glucocorticoids acting locally as paracrine or autocrine communication signals was therefore unexpected (226). The very first organ in which extra-adrenal steroidogenesis was identified was the thymus. This ran contrary to the commonly held belief that the thymus is the main target for glucocorticoids produced by the adrenal gland. In the mouse, the thymus typically responds to glucocorticoids by massive apoptosis of CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes and involution (92). However, all the elements necessary for the local production and release of corticosterone are present in murine thymic epithelial cells, as demonstrated in vitro (175). Furthermore, co-culturing of thymic epithelial cells with thymocytes induced apoptosis of thymocytes. This effect was blocked by a GR antagonist as well as by inhibitors of the enzymes involved in the production of corticosterone. Thymocytes produce corticosterone in an age-dependent manner that is concurrent with thymocyte differentiation into CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and thymus involution (181). Several ingenious studies have confirmed the physiological role in vivo of the local production of glucocorticoids in the thymus and have demonstrated their independence from circulating glucocorticoids (226). In general, the findings of these studies confirm that thymic-derived glucocorticoids locally regulate thymocyte development, the rate of naive T-cell formation, and the seeding in the periphery of recent thymic emigrants. This function of thymic glucocorticoids would complement the role of adrenal glucocorticoids in regulating strong and systemic immune responses (226).

Extra-adrenal glucocorticoid synthesis has also been identified in intestinal epithelial cells that are part of the proliferating cells of the crypts of the intestinal mucosa. Locally formed glucocorticoids have both an inhibitory and a costimulatory role in intestinal T-cell activation (45). On the basis of observation that the expression of steroidogenic genes is decreased in colon biopsies of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, it has been proposed that the local synthesis of glucocorticoids is important for controlling intestinal inflammation and immune responses (48).

Skin inflammation induces glucocorticoid synthesis by keratinocytes. As the skin possesses all the components of a local HPA axis, glucocorticoid synthesis in the skin can act in a manner complementary to the HPA axis to inhibit local inflammation and promote wound healing (257).

D. Other Hormones and Neuropeptides

After showing that human leukocyte IFN-α has strong antigenic relatedness to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and endorphins (24), Smith et al. (213) demonstrated that induction of IFN-α in mice by inoculation with a noncytotoxic avian virus, the Newcastle disease virus, simultaneously caused a time-dependent increase in corticosterone production by spleen lymphocytes. The culprit turned out not to be an ACTH-like moiety of IFN-α but leukocyte-derived ACTH produced by the processing of leukocyte proopiomelanocortin in a manner similar to what takes place in the anterior pituitary. As proopiomelanocortin is at the origin of β-endorphin, the stage was set for a quest for ACTH and opioid receptors and their signaling pathways in lymphocytes (23). Classic opioid binding sites had already been described on leukocytes (253), and it did not take long to confirm the presence of ACTH receptors on lymphocytes (31, 46). Other precursors of opioid peptides, prodynorphin, which is at the origin of dynorphin and Leu-enkephalin, and preproenkephalin, which is responsible for Met-enkephalin and Leu-enkephalin, were found to be expressed in leukocytes of several species, together with their receptors (68, 252). Whether opioid peptides produced by immunocytes function as communication signals within the immune system or between the immune system and the neuroendocrine system could then be investigated.

On the basis of the observation that enkephalins promote activity of immunocytes at baseline and suppress activity of activated immune cells, it was proposed that these molecules function as fine tuners of the immune response (68). Evidence of immune-to-nerve communication for immune-derived peptides was extensively described in the field of inflammation-mediated pain. Opioid-containing immunocytes migrate to the site of inflammation, where they release β-endorphin that activates peripheral opioid receptors on sensory nerves to attenuate pain (38, 207, 219). The release of opioid peptides from immune cells is mediated by several signal molecules, including corticotrophin-releasing hormone, norepinephrine, and IL-1β, the production and release of which are upregulated at the site of inflammation (FIGURE 2) (218).

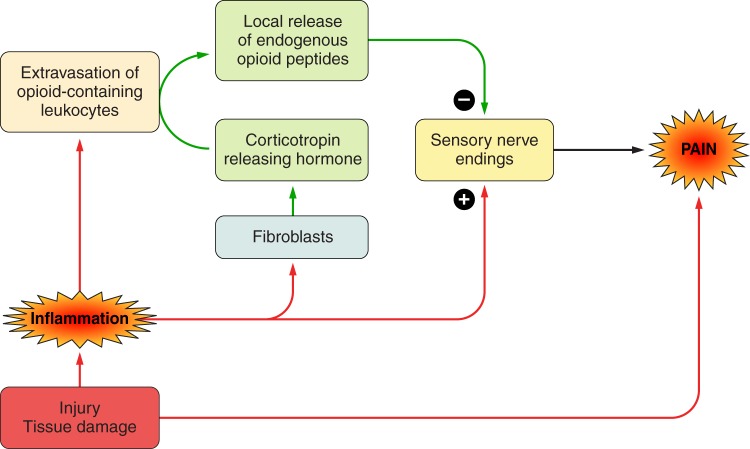

FIGURE 2.

Role of opioid-containing leukocytes in the regulation of inflammation-induced pain. Proinflammatory cytokines released by activated innate immune cells sensitize sensory nerve endings, resulting in an amplification and prolongation of the initial pain reaction triggered by activation of nociceptors in response to the injury. The pain response is downregulated by endogenous opioid peptides released by locally infiltrating opioid containing leukocytes in response to corticotropin releasing hormone produced by fibroblasts. [Adapted from Stein et al. (218).]

The possibility that prolactin and growth hormone regulate immunity by a paracrine/autocrine, rather than hormonal, mechanism was recognized early in the study of the immune properties of these peptides. As with other hormones, the hormonal role of these peptides was described first. The initial observations were made in hypophysectomized rats in which both the deficient antibody response to sheep red blood cells and the delayed-type hypersensitivity response to dinitrochlorobenzene could be restored by replacement treatment with exogenous prolactin or growth hormone (162). This effect could be easily explained by the presence of specific binding sites for prolactin and growth hormone on T and B lymphocytes. Unexpectedly, the potent immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine was found to increase circulating levels of prolactin, and administration of the dopamine agonist bromocriptine blocked cyclosporine’s immunosuppressive properties when administered at doses that abrogated cyclosporine-induced increase in prolactin levels (43). These findings were initially interpreted to suggest that hyperprolactinemia mediates the immunosuppressive effects of cyclosporine. However, further studies showed that cyclosporine and prolactin compete with each other for binding to prolactin receptors on lymphocytes (196) and that part of the signal reaching prolactin receptors is actually a prolactin/growth hormone-related polypeptide produced locally by stimulated lymphocytes (103, 195).

The immunomodulatory activities of growth hormone and prolactin have been reviewed extensively in the past 25 yr (61, 116, 117, 236, 248), and there is no need to reiterate this information. We know now that the production and release of growth hormone and prolactin are regulated by immune factors in both the pituitary gland and in lymphocytes, and the many different effects of these peptides on immune cells can be explained by the intervention of posttranscriptional and posttranslational processes generating various isoforms and variants of these peptides (176, 246).

E. Summary

Numerous studies carried out in vitro and in vivo show that catecholamines released by sympathetic nerve fibers have potent modulatory effects on immune cells. Some of these effects are mediated by alterations in monocyte and lymphocyte trafficking. In addition, immune cells can produce catecholamines that act locally as paracrine or autocrine communication factors in similar or different physiological processes. However, the importance of this last mechanism in immunophysiology and immunopathology has not yet been fully appreciated. Like catecholamines, glucocorticoids can be produced by immune cells in lymphoid tissues and exert local actions on different physiological processes that are in general complementary to those mediated by circulating glucocorticoids produced by the adrenal gland. This action is not necessarily immunosuppressive as glucocorticoids can be proinflammatory in some conditions. The same duality in the modality of action of other hormones and neuropeptides is also apparent.

III. IMMUNE INFLUENCES ON THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

A. Historical Perspective

The existence of immune influences on the nervous system took longer to be recognized and studied than that of neuroendocrine influences on the immune system. The reason is that the molecular nature of immune communication signals (monokines and interleukins, generally grouped together under the name of cytokines) was not elucidated until the 1980s, and these molecules were just not available for physiological studies. The first cytokine to be cloned and produced by recombinant technology was actually a monokine, IL-1. Research on cytokine actions in the brain stemmed from two independent lines of research. The first one was the physiology of fever, which was and still is part of mainstream physiology. The second one was immunophysiology. This last line of research took longer to emerge because of its very marginal place at the boundary between immunology and physiology.

Fever can be defined as a regulated increase in the set point for temperature regulation. Because the set point for temperature regulation is elevated, the feverish organism generates more heat by thermogenesis and actively maintains it by minimizing thermolysis. Fever is not caused by a direct action of microbial pathogens on the brain thermoregulatory centers. It is induced by soluble factors that are released by activated leukocytes, the so-called endogenous pyrogens. The problem faced initially by fever physiologists was that the molecular identity of endogenous pyrogens could not be characterized based solely on their in vivo pyrogenic activity, because available assays lacked specificity. This difficulty was eventually overcome by the development of an appropriate in vitro assay, the lymphocyte activating factor assay (83, 84). Based on this assay, the first endogenous pyrogen, IL-1, was cloned in 1984 (8, 140). Other cytokines that have since been found to act as endogenous pyrogens include IFN- α, TNF, and IL-6 (59). IL-1 represents two different cytokines, IL-1α and IL-1β, produced by two different genes. Most of the early literature on IL-1 refers to IL-1β. Unless mentioned otherwise, we keep this convention in the present review.

The understanding that immune signals could control the immune system via a downregulating neuroendocrine feedback loop involving cytokine action on the brain emerged within the context of immunophysiology. Immunophysiologists reasoned that, like any other physiological system in the body, the immune system requires two levels of regulation: a self-regulatory process that is intrinsic to the immune system, and an external regulatory loop that makes use of the central nervous system and its means of communication with the rest of the body, i.e., the autonomic nervous system and the neuroendocrine system. While mainstream immunologists focused primarily on the self-contained, self-monitored immune system, Besedovsky and Sorkin relentlessly searched for evidence of extrinsic regulation. They hypothesized that if extrinsic regulation exists, it should make use of immune factors able to signal the brain to recruit neuroendocrine factors with immunomodulatory activity. Pivotal to their research was the demonstration that the mounting of an antibody response was associated with increased activity of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system (18); before this discovery, the immune response was believed to be regulated only intrinsically within the immune system. In mice and in rats injected with sheep red blood cells (a T-cell-dependent antigen), the peak of the immune response coincided with an increase in glucocorticoid blood levels (18). In addition, this peak was preceded by decreased norepinephrine in the spleen that was inversely related to the magnitude of the immune response (54). At the functional level, Besedovsky and Sorkin showed that the glucocorticoid response to an antigenic stimulation is required for antigenic competition. Antigenic competition refers to the inhibition exerted by an immune response to a first antigen relative to the immune response to a second non-cross-reactive antigen. This form of competition does not occur in adrenalectomized mice, which are unable to mount a glucocorticoid response to the first antigen (19). To search for the immunological factors that signal the ongoing immune response to the brain neuroendocrine circuits, Besedovsky and Sorkin injected supernatants of in vitro activated lymphocytes into naive mice and identified what they called a “glucocorticoid increasing factor” (20). In collaboration with Dinarello, who had just cloned IL-1 and had obtained sufficient quantities of a recombinant form of it to inject to mice, Besedovsky and his colleagues were then able to demonstrate that this cytokine activated the pituitary-adrenal axis in a manner similar to the glucocorticoid increasing factor (16). Because there was still some uncertainty about the exact site of action of IL-1 to induce glucocorticoid release, it was important to show that this effect was mediated in the hypothalamus, rather than in the pituitary or the adrenal cortex (14). With this demonstration of the role of IL-1 in a brain-mediated immunoregulatory loop, the stage was finally set for further studies on the mechanisms of these regulatory processes.

As we will see, studies of the influence of immune communication signals on the central nervous system followed the same path of reasoning as the one that led to our understanding of the influence of neuroendocrine communication signals on the immune system. The consideration of long-range interactions between the immune system and the brain via hormonal-like factors predominated for some time; gradually, however, the study of short-range interactions based on immune factors produced locally in the nervous system gained favor.

B. Pyrogenic Effects of Cytokines

The conventional view of fever in infectious diseases holds that the fever response is mediated by endogenous pyrogens released by activated mononuclear phagocytes into the general circulation. This explains why most experimental studies of fever involved intravenous injection of endogenous pyrogens into naive experimental animals. This route of injection continued to be used even after recombinant cytokines became available, despite the fact that cytokines do not behave as circulating communication factors.

The sequence of events leading to the production of inflammatory cytokines by innate immune cells in response to pathogenic microorganisms has been identified. Specialized monocyte/macrophage membrane receptors identified as Toll-like receptors recognize specific molecular moieties of pathogens called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (72, 191). Activation of Toll-like receptors by PAMPs and by danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that are released by damaged cells from the host triggers a signaling cascade that culminates in the synthesis and release of proinflammatory cytokines (170). LPS, for instance, activates Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) on monocytes and macrophages. This requires the association of LPS to a specific binding protein, LPS-binding protein (LBP). The LPS-LBP protein complex associates with still another membrane protein, cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14), before recruiting another extracellular protein, myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD-2). Activation of TLR4 recruits two pathways, a myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88)-dependent pathway and a MyD88-independent pathway. MyD88 recruits IL-1 receptor associated kinases (IRAKs) and the adaptor molecules TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAF6) that lead to activation of both mitogen-activated protein kinases Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38, and transcription factor nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB). JNK and p38 activate, respectively, CREB and activator protein 1 (AP1). CREB, AP1, and NF-κB are important for the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines. The MyD88-independent pathway recruits TRAF3 and induces interferon-regulatory factor (IRF3) signaling leading to expression of type I interferons and interferon-inducible genes (170). The MyD88 pathway is shared with other TLRs including TLR2, TLR5, and TLR11 while the MyD88-independent pathway is shared with TLR3.

In terms of communication, the concept that predominated initially was that proinflammatory cytokines were released by innate immune cells into the general circulation and acted at distance. Because of their big molecular size and their hydrophilic nature, proinflammatory cytokines could not cross the blood-brain barrier. They acted instead on those parts of the brain that are devoid of a blood-brain barrier, the so-called circumventricular organs. In the case of the fever response, the target circumventricular organ was the organum vasculosum laminae terminalis (OVLT). At the level of the OVLT, cytokines induced the synthesis of prostaglandins E2 (PGE2). PGE2 are formed from arachidonic acid by cyclooxygenase (COX-1 and COX-2)-dependent synthesis of prostanglandin H2 and further transformation by prostaglandin synthases. PGE2 diffused inside the brain parenchyma and activated PGE2 receptors located on thermosensitive neurons in the anterior preoptic area of the hypothalamus (25). This mode of action of proinflammatory cytokines was well accepted in the scientific community of fever physiologists until further studies revealed a much more complex circuitry than originally anticipated (70, 194, 200).

Fever in response to LPS is characterized actually by a biphasic course. The first wave of fever originates in the liver. It is mediated by activation of the complement cascade and release of constitutive COX-1- and COX-2-dependent PGE2 by liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) (26). The released PGE2 activates vagal afferents that terminate in the nucleus tractus solitarius and project to the ventromedial part of the hypothalamus via the ventral noradrenergic bundle. The second wave is mediated by the production of inflammatory cytokines at the periphery. These cytokines induce the synthesis and release of brain cytokines, including IL-6 which is mainly produced by astrocytes. Brain cytokines ultimately stimulate the production and release of PGE2 by perivascular cells and cerebral endothelial cells; this occurs mainly along venules after induction of the PGE2 synthesizing enzymes COX-2 and microsomal PGE synthase-1 (70, 200). Centrally produced PGE2 activate PGE2 receptors 3 (EP3) that are present on thermosensitive neurons in the median preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus. This second wave of fever is supported by the synthesis and release of PGE2 by cerebral endothelial cells. The neural circuitry activated by PGE2 acting on EP3 receptors involves two populations of preoptic GABAergic neurons that ultimately control cutaneous vasoconstriction and adipose tissue thermogenesis via the autonomic nervous system (200). The gradual recovery of fever is mediated by the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines both peripherally and centrally (194) and by the dampening of cytokine synthesis in activated macrophages under the effect of heat stress (66, 70).

C. Activation of the Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis by Cytokines

The neuroendocrine response to an infectious agent cannot be monitored with the same temporal precision as variations in body temperature. This certainly explains why the response of the HPA axis to peripheral immune stimulation is usually described as monophasic rather than multiphasic. Nonetheless, two phases can be distinguished: an earlier phase occurring 1–2 h after injection of LPS, and a sustained response still apparent 6 h after treatment (64). Earlier studies of the ACTH and corticosterone response to an intraperitoneal injection of IL-1 revealed that these responses took longer to develop than the usual response to an exteroceptive stressor, 2 h for the peak ACTH and corticosterone response instead of 15–30 min (16). The sustained phase of the HPA axis response to LPS is dependent on the production and release of PGE2 by the brain vasculature in a COX-2- and mPGES-1-dependent manner (64). PGE2 acts in a paracrine manner to stimulate EP1 and EP3 expressing catecholaminergic neurons in the ventrolateral medulla of the brain (150). These neurons project to CRH containing neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (67). The late phase of the HPA axis is temporally dependent on an inducible PGE2 synthesis interacting with an earlier neuronal afferent signal involving constitutive COX-1-dependent PGE2 synthesis in perivascular cells and endothelial cells of the brain vasculature (64, 80). The relative involvement of perivascular cells and endothelial cells depends on the stimulus: IL-1 appears to activate only perivascular cells, while LPS activates both perivascular cells and endothelial cells (206). In addition, perivascular cells exert an inhibitory effect on the response of endothelial cells to LPS that becomes apparent once they are artificially eliminated. However, this account of the role of perivascular cells in the HPA axis response to IL-1 does not fit with immunohistochemistry data showing a selective expression of IL-1 receptors in brain endothelial cells but not in perivascular cells (128). Cell-specific deletion of IL-1 receptors confirms the immunohistochemistry data. Mice lacking IL-1 receptors in hematopoietic cells including perivascular macrophages still respond to IL-1 injected systemically by increased plasma levels of ACTH and corticosterone; this is no longer the case in mice lacking IL-1 receptors in brain vascular cells (151).

The possibility that LPS acts in the adrenal cortex rather than in the hypothalamus to increase circulating corticosterone levels was ruled out by studies of mice with adrenocortical cell-specific deletion of MyD88. This did not impair the HPA axis response to systemic LPS, confirming the effects of LPS take place at the level of the hypothalamus or the pituitary (113). There is evidence that cytokines, including IL-1 and IL-2, can act directly on pituitary cells and increase the release of various pituitary peptides, including ACTH (15, 114). However, the relevance of this activity for the in vivo HPA axis response to immune stimuli is still unclear (154), although there is evidence for direct cytokine action on the pituitary in conditions of prolonged exposure to cytokines after ACTH release has been initiated by CRH (208). Folliculo-stellate cells in the anterior pituitary act as an important source of IL-6 that influences hormonal output from the anterior lobe in a paracrine manner (56, 58).

CRH-containing parvocellular neurons in the rat hypothalamus also produce vasopressin, which strongly potentiates CRH-induced ACTH secretion and augments several actions of extra hypothalamic CRH in the brain. The acute effects of IL-1 on the HPA axis are mediated predominantly by CRH, since they are abolished by CRH immunoneutralization (14). However, CRH immunoneutralization is less effective after repeated administration of IL-1. This is due to phenotypic changes in the expression of CRH and vasopressin in hypothalamic parvocellular neurons, with vasopressin dominating over CRH (230). A similar increase in vasopressin stores in CRH-containing neurons occurs several days after injection of a single dose of IL-1. This phenotypic switch affecting CRH-containing neurons is not specific to IL-1; it is also observed after endotoxin administration and in response to electric foot shocks and social defeat, but not after other types of stressors. The increased expression of vasopressin in CRH-containing neurons is responsible for the cross-sensitization phenomenon that can develop in response to stressors occurring in succession: administration of IL-1 at a given time point sensitizes the response to a different stressor that occurs later (229).

The activating effects of cytokines on the HPA axis are limited by the glucocorticoid resistance that develops in response to inflammation. Glucocorticoid resistance typically occurs in humans in response to repeated injections of IFN-α. It takes place at the level of the hippocampus rather than the pituitary (87). This is not an artifact due to the administration of exogenous cytokines, since it also develops in virus-infected organisms (13, 158). Mechanisms include disruption of glucocorticoid receptor translocation and DNA binding, and alterations in glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation status (172).

D. Behavioral Effects of Cytokines

The most visible face of the response to an infectious agent is the sickness behavior that develops in ill individuals. Inactivity, decreased responsiveness to external stimuli, sleepiness, decreased appetite, and social withdrawal are the usual signs of a microbial infection. Agitation can occur as a prodrome, but this is rare. These behavioral alterations are often associated with malaise and pain. They are part of a whole repertoire of disease-control strategies that enable organisms to adapt to the very expensive metabolic cost of mounting an immune response and a fever (99, 100). Because behaviorists are usually not interested in the behavior of sick individuals and physiologists rarely engage in lengthy descriptions of behavioral activities, the study of cytokine-induced sickness behavior lagged behind studies of cytokine-induced fever and HPA axis activation. It became more mainstream only after identification of the relationship between sickness behavior and symptoms of depression (53).

The behavioral alterations that develop in animals injected with LPS or cytokines recapitulate those observed in ill individuals (37, 81). The intensity and duration of sickness behavior can be easily measured by reduction in spontaneous activities such as exploration of a novel conspecific or ambulatory activity in a familiar or novel environment (119). Reduced appetite can be measured by decreases in food and water intake. More elaborate indexes of sickness behavior include decreased motivation in tasks requiring an effort to access the reward and impaired cognitive abilities in tasks based on recognition of a novel object, acquisition of context-dependent fear conditioned response, and spatial memory (49, 50, 156, 180).

Neal Miller was the first researcher to propose that the changes in behavior that develop in ill individuals are the expression of a motivational state that competes with usual behavioral activities, rather than just a decrease in these behaviors. He based this hypothesis on the observation that rats injected with endotoxin were less willing to work for food, water, and a rewarding electrical stimulation in their lateral hypothalamus, but they were still able to increase their response rate for gaining some rest when put into a forced wheel-running apparatus (159). This flexibility in the behavioral response to a stimulus depending on the environment and the consequences of the response is typical of a motivated behavior. Competition between the motivational state of sickness and another form of motivated behavior, maternal behavior, was elegantly demonstrated in later studies carried out in lactating mice injected with LPS. LPS-treated dams behaved in a sick way by lying immobile and being apparently indifferent to their pups. However, when their pups were dispersed in the cage and the nest removed and replaced by cotton wool, dams emerged out of their apathy and actively engaged in retrieving pups to the cage location where the cotton wool was placed. They still did not engage in nest building unless submitted to an ambient temperature of 6°C (7). The interoceptive feelings associated with sickness behavior have been studied in human volunteers inoculated with typhoid vaccine or injected with a small dose of LPS. Depressed mood, anhedonia, and fatigue are the typical symptoms that develop in these conditions (35, 63, 97, 130).

The inflammatory signals that mediate sickness behavior are transmitted to the brain by the neural afferents that innervate the site of the body at which the inflammatory response takes place. When LPS is injected into the peritoneal cavity, the vagus nerve is the predominant neural pathway, as demonstrated by subdiaphragmatic vagotomy experiments (27) or by reversible inactivation of the dorsal vagal complex using local injection of bupivacaine (149). Recruitment of neural communication pathways combines with activation of macrophage-like cells in circumventricular organs by circulating pathogen-associated molecular patterns. This results in the local synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines that slowly diffuse into the neural compartment by volume diffusion while actively recruiting macrophages and microglia “en passant” (52, 126, 239). The involvement of brain proinflammatory cytokines in sickness behavior induced by systemic administration of cytokines or LPS has been repeatedly demonstrated by blocking experiments in which cytokine antagonists such as IL-1RA, a specific antagonist of IL-1 type I receptor, have been administered into the lateral ventricle of the brain in rodents injected with cytokines or LPS at the periphery (51, 118, 127). The specific brain areas that mediate sickness behavior have been difficult to delineate. There are several reasons for this, starting with the diffuse nature of microglial activation in the brain in response to systemic inflammation, as evidenced by positron emission tomography with ligands of the 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) in monkeys and humans injected with endotoxin (96, 198). TSPO is expressed on the outer mitochondrial membrane of microglia and is prominently upregulated in response to inflammation. Its level of expression in resting microglia is normally low but increases rapidly in activated microglia. This explains why imaging expression of TSPO is used as a marker of microglial activation despite the many limitations of the currently available TSPO radiotracers (240).

The second reason for the difficulties encountered in delineating the brain areas that mediate sickness behavior is that these brain areas differ according to the behavioral process affected by inflammation. Decreases in food intake culminating in anorexia are unlikely to be mediated by the same neuronal networks as fatigue or even anhedonia. Most of the research on neuroanatomy of sickness behavior has focused on endotoxin-induced anorexia and the role of prostaglandins and feeding modulating peptides, including proopiomelanocortin, leptin, neuropeptide Y, agouti-related protein, and ghrelin, and their neural targets in the hypothalamus (e.g., Refs. 62, 178, 200). This field of research has expanded beyond sickness behavior because of the somewhat paradoxical role of hypothalamic inflammation in the resetting of energy homeostasis that is associated with obesity (233). More in tune with the concept of sickness behavior, decreased social interactions in rats in response to LPS have been shown to be mediated by forebrain IL-1 acting on the central amygdala and dorsolateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in a prostaglandin-independent manner (127). In addition to causing social withdrawal, LPS has aversive properties that can be evidenced using conditioned taste aversion or conditioned place aversion (78, 247). Acquisition of a conditioned place aversion in response to LPS has been shown to be mediated by COX-1-dependent synthesis of PGE2 by endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier. PGE2 acts on EP1 receptors located on dopamine D1 receptor-expressing neurons, with expression of the aversion being dependent on GABA-mediated inhibition of dopaminergic cells (78). The predominant involvement of prostaglandins rather than brain cytokines in this behavior is probably due to the time interval between injection of LPS and conditioned place aversion training (10 min). This time interval is much too short for induction of a cytokine cascade in response to LPS both at the periphery and in the brain.

Systemic inflammation caused by injection of LPS or proinflammatory cytokines is associated with motivational deficits that can best be characterized using effort tasks, in which animals have to exert a sustained effort to obtain an expected reward. In mice trained to obtain a sweet milk reward according to a progressive ratio 10 schedule (requiring 1 response for the first reward, 10 for the second, 20 for the third, and so on), administration of IL-1 decreased the breaking point, i.e., the ratio at which mice stopped responding for the reward (131). This was not due to a decreased sensitivity to reward, since LPS-treated mice trained to nose poke a switch key for a highly preferred food (chocolate pellets) by responding 10 times in succession and another key for a less-preferred food (grain pellets) by responding only once continued to respond more on the key giving them access to the highly preferred food than on the key giving them access to grain pellets (237). In terms of neurotransmitters, inflammatory stimuli have a profound depressive effect on activity of orexin-expressing neurons (82, 91). Orexinergic neurons are located in the perifornical lateral hypothalamic area and regulate motivational arousal, thanks to their widespread projections to the rest of the brain. These neurons are inhibited by neurotensin-expressing GABAergic interneurons that sense systemic inflammation indirectly via alterations in leptin (91). The link between orexin and motivation is provided by orexin-dependent glutamatergic projections onto dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (28).

Despite its strong relatedness to fever, there is clear evidence that sickness behavior is mediated by mechanisms different from those of fever. The range of behaviorally active cytokines does not fully overlap with that of pyrogens; for instance, IL-6 has no behavioral effect despite its potent pyrogenic activity and its activating effects on the HPA axis (133). In the same manner, subdiaphragmatic vagotomy abrogates decreases in social exploration induced by LPS but has inconsistent effects on the fever response (141). In addition, injections of IL-1RA into the lateral ventricle of the brain abrogate LPS-induced decreases in social interactions but have no effect on fever and activation of the HPA axis (127).

In summary, the effects of pathogenic microorganisms on thermoregulation, the HPA axis, and behavior are dependent on the de novo production of cytokines by activated innate immune cells. Transmission of this peripheral immune message to the brain involves multiple communication pathways with a possible relay in visceral organs such as the liver. These communication pathways ultimately recruit either other communication signals elaborated by brain microvascular endothelial cells, e.g., prostaglandins, or the same communication signals, e.g., IL-1, produced by brain innate immune cells (perivascular macrophages and micoglia). Prostaglandins are prominently involved in very short-term responses to inflammation (<1 h), whereas brain cytokines are more important for relatively longer responses (several hours) (FIGURE 3).

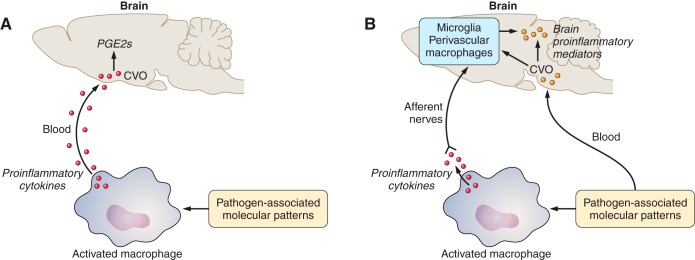

FIGURE 3.

Immune-to-brain communication pathways. In response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns such as lipopolysaccharide sensed by Toll-like receptors and the inflammasome (not represented in the figure), activated macrophages produce and release proinflammatory cytokines in their microenvironment, including IL-1β (red circles). As presented in A, proinflammatory cytokines were initially supposed to be released in the general circulation and act at the level of circumventricular organs (CVO) where the blood-brain barrier is fenestrated. Proinflammatory cytokines were proposed to induce there the release of lipophilic prostaglandin E2 acting as secondary messengers on neurons. However, the demonstration that immunelike cells in the brain including meningeal and perivascular macrophages and microglia produce and release brain proinflammatory cytokines led to a different representation illustrated in B. The peripheral immune signal is relayed to the brain by afferent nerves. This neural message together with slowly diffusing cytokines produced at the level of circumventricular organs and prostaglandins produced by brain endothelial cells in response to circulating pathogen-associated molecular patters results in the production of brain cytokines by activated microglia. Overspill of cytokines in the general circulation can also be transported for some of them into the brain side of the blood-brain barrier (not represented in the figure).

E. Role of Brain Cytokines in Synaptic Plasticity

Cytokines are not only expressed in the brain in response to peripheral immune stimuli. They are also present constitutively in the brain. Despite their expression levels being much lower than those of their inducible counterparts, they play an important role in synaptic physiology and plasticity. One example is the constitutive regulation by glial TNF of the surface expression of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors on hippocampal neurons. Exposure of cultured hippocampal neurons to TNF increased the levels of surface AMPA receptors in the plasma membrane of synapses, whereas blockade of endogenous TNF by treating cultures with a soluble form of the TNF receptor 1 had the reverse effect (12). Similar effects were obtained in hippocampal slices. In both cases, the influence of TNF on AMPA receptor trafficking resulted in rapid changes in synaptic strength at glutamate excitatory synapses. Further studies showed that these effects are specific to TNF and do not generalize to other inflammatory cytokines (221). They are mediated by TNFR1 and phosphoinositol-3-kinase activation. In addition, TNF also increased the endocytosis of surface GABAA receptors, resulting in a decrease in inhibitory synaptic transmission. The adaptive role of TNF in the regulation of synapses varies depending on the brain area. While cortical pyramidal cells and motor neurons behave like hippocampal neurons in their response to TNF, this is not the case for striatal neurons. TNF drives the internalization of AMPA receptors and reduces corticostriatal synaptic strength on GABAergic medium spiny neurons of the dorsolateral striatum (135).

TNF acts not only on neurons but also on astrocytes. Constitutive TNF is able to control glutamate release from astrocytes, as demonstrated by the inability of astrocytes from TNF or TNF receptor knockout mice to release glutamate in response to the activation of P2Y1 receptors by ATP released during synaptic activity. Because of this deficiency, the process of gliotransmission is impaired. The lack of astrocyte-dependent activation of presynaptic N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors compromises both synaptic transmitter release and synaptic strengthening at the level of glutamatergic synapses (199).

In contrast to what was thought originally, constitutive TNF is produced not by neurons but by microglia. Microglia are the resident macrophage population of the central nervous system. Beyond their role as phagocytic cells in the central nervous system when activated by injury or microbial infection, microglial cells are also involved in the development and maintenance of normal synaptic function. Like most tissue macrophages, microglia do not originate from blood monocytes or meningeal macrophages but from yolk sac primitive macrophages during early development (65, 85). They persist by self-renewal in the central nervous system until adulthood and do not need to be replenished by peripheral cells from the circulation (86). Their differentiation and maintenance are dependent on CSF-1 and IL-34 (90, 179, 243), both acting via CSF-1 receptors.

The formation of mature neural circuits requires the activity-dependent elimination or pruning of inactive synapses. Microglia play an important role in this process, as demonstrated by their ability to engulf synaptic material during postnatal development in the mouse (174). They make use of several signaling pathways for this, including the classic complement cascade that is part of the innate immune system. Working on the mouse reticulogeniculate system, Stevens and colleagues (201, 223) demonstrated in an elegant series of experiments that the complement protein C1q, the initiating protein in the classical complement cascade, and the downstream complement protein C3 localize to immature synapses and are necessary for the developmental pruning of nonfunctional reticulogeniculate synapses. C1q and C3 bind to C3 receptors that are expressed by microglia. These receptors are upregulated in microglia during the period of synaptic elimination and are downregulated later on. Furthermore, C3 receptor knockout mice displayed reduced microglial phagocytic function and sustained deficits in eye-specific segregation of synaptic inputs in the reticulogeniculate system and in synaptic connectivity (201). What is remarkable here is the analogy of function in the immune system and in the central nervous system: in both systems, complement proteins clear cellular material that has been tagged at its membrane surface for elimination (222). In the central nervous system, this process requires a close cooperation between synapse targets and microglia.

Microglial cells interact with neurons and synapses via several signaling pathways other than the complement cascade. One of these signaling pathways involves the chemokine CX3CL1, also known as fractalkine, and its receptor CX3CR1. Chemokines are used by hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissues to attract immune target cells by chemotaxis. In the central nervous system, CX3CL1 is mostly expressed by neurons and CX3CR1 is uniquely expressed on microglial cells (5, 138). Mice lacking the fractalkine receptor displayed a transient deficit in synaptic pruning during the second and third postnatal weeks, together with electrophysiological signs of synaptic abnormalities (174). However, this was probably due to the role of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling pathway in microglia migration into the brain during development rather than to the involvement of this pathway in the tagging of synapses to be eliminated, given the reduced microglial density in the brains of CX3CR1 knockout mice compared with littermate controls.

Another signaling pathway makes use of LBP that tags synapses in the developing hippocampus (245). In the innate immune system, LBP acts as an acute phase protein and is necessary for LPS to bind to membrane-bound CD14 on macrophages before being able to activate TLR4 (258). LBP is also temporarily expressed on hippocampal synapses during development, in close association with CD14 surface molecules present on microglia cells (245). In rodents, early life stress in the form of daily brief pup-dam separations is well known to cause increased anxiety-like behavior at adulthood. Early life stress decreased the expression of synaptic but not plasmatic LBP. Genetic deletion of LBP resulted in increased spine density and abnormal spine morphology in the hippocampus, and this was associated with increased anxiety-like behavior at adulthood. These intriguing results point to a possible role for LBP in the development and function of hippocampal synapses during the first weeks of life (245).

F. Summary

The neuroendocrine perspective that initially dominated studies of the neural effects of cytokines left little room for the possibility of a local action of these molecules in the central nervous system despite the fact that cytokines were initially described by immunologists as autocrine and paracrine communication factors. It is only after cytokines were identified in the brain with their receptors that this notion changed. Cytokines are not only induced in the central nervous system in response to peripheral immune stimuli but in addition they are expressed there constitutively and serve as important plasticity factors in the formation and stabilization of neuronal circuits during development.

IV. ALTERATIONS IN THE COMMUNICATION BETWEEN THE IMMUNE AND THE NERVOUS SYSTEM: FROM PHYSIOLOGY TO PATHOLOGY