Abstract

The hallmark symptom of chronic heart failure (HF) is severe exercise intolerance. Impaired perfusive and diffusive O2 transport are two of the major determinants of reduced physical capacity and lowered maximal O2 uptake in patients with HF. It has now become evident that this syndrome manifests at least two different phenotypic variations: heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF and HFrEF, respectively). Unlike HFrEF, however, there is currently limited understanding of HFpEF pathophysiology, leading to a lack of effective pharmacological treatments for this subpopulation. This brief review focuses on the disturbances within the O2 transport pathway resulting in limited exercise capacity in both HFpEF and HFrEF. Evidence from human and animal research reveals HF-induced impairments in both perfusive and diffusive O2 conductances identifying potential targets for clinical intervention. Specifically, utilization of different experimental approaches in humans (e.g., small vs. large muscle mass exercise) and animals (e.g., intravital microscopy and phosphorescence quenching) has provided important clues to elucidating these pathophysiological mechanisms. Adaptations within the skeletal muscle O2 delivery-utilization system following established and emerging therapies (e.g., exercise training and inorganic nitrate supplementation, respectively) are discussed. Resolution of the underlying mechanisms of skeletal muscle dysfunction and exercise intolerance is essential for the development and refinement of the most effective treatments for patients with HF.

Keywords: diffusive O2 transport, exercise intolerance, exercise training, heart failure, HFpEF, HFrEF, perfusive O2 transport, skeletal muscle microcirculation

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of chronic heart failure (HF) and other forms of cardiovascular disease is predicted to exceed 40% of the U.S. population by 2030 (54). HF is a chronic syndrome with high morbidity and mortality (8) resulting from ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy, valvular incompetence, hypertension, or diabetes inducing a “perfect storm” of systems dysfunction that coalesces to impair skeletal muscle function (40, 57, 95b). Thus HF severity can be measured by the reduction in exercise tolerance and O2 transport-utilization pathway impairment [maximal O2 uptake, V̇o2max, speed of V̇o2 kinetics (14, 95b, 126)]. Research efforts in recent decades have identified multiple aspects of HF-induced skeletal muscle dysfunction including blunted endothelium-dependent arteriolar vasodilation, capillary involution and cessation of red blood cell flux in many capillaries, increased muscle deoxygenation, fiber atrophy and weakness, mitochondrial rarefaction, and compromised metabolism. Not only are these targets for therapeutic intervention themselves, but also improved skeletal muscle function and exercise capacity can help reduce/reverse cardiac remodeling, enhanced sympathetic stimulation, and immune system dysfunction (40, 57, 95b). Acceptance of this bidirectionality between central and peripheral function and dysfunction has spurred interest in improving skeletal muscle function to benefit outcomes for patients with HF.

V̇o2max constitutes the best predictor of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (47). Thus deconditioning may be an extremely important element in the pathophysiology of HF, but it does not appear to be an obligatory component. Specifically, in the rat model of HF, Simonini and colleagues (114) demonstrated that animals' postmyocardial infarction developed HF dysfunction with a level of cage activity that was not different from their sham-operated controls. Improvement in V̇o2max induced by exercise training benefits exercise tolerance and quality of life and reduces morbidity and mortality for patients with HF (41) with cardiac transplantation being safely deferred in patients whose V̇o2max is >14 ml O2·min−1·kg−1 (84). Unfortunately, the potential rewards of cardiac rehabilitation are seldom realized, in part, due to its cost, lack of availability, and high dropout rates (43). This is tragic because exercise training produces a sustained improvement in functional capacity and quality of life in patients with HF (7). Better understanding of the mechanistic bases for HF-induced muscle dysfunction can be harnessed to design more effective and sustainable therapeutic strategies, for example, exercise programs, applied across the HF continuum.

Recent advances in HF treatment targeting skeletal muscle include 1) application of high-intensity interval training to achieve larger increases in V̇o2max (106, 128), 2) combination of aerobic and resistance exercise to improve V̇o2max and increase muscle mass (40), 3) exploration of small muscle mass exercise and training (28–30), 4) acute and chronic nitrate supplementation to increase muscle blood flow (Q̇), exercise economy, and exercise capacity (34, 42, 132, 133), and 5) phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors to increase muscle oxygenation, speed V̇o2 kinetics, and increase exercise capacity (115, 116). From these and other investigations, it has become apparent that discriminating the contribution of perfusive (i.e., blood flow × arterial O2 content, Q̇O2) and diffusive (DO2) O2 transport within skeletal muscle and assessment of muscle microvascular oxygenation (Fig. 1) provides powerful insights into HF-induced muscle dysfunction and the mechanistic bases for the potential therapeutic impact of these treatment strategies.

Fig. 1.

Oxygen uptake (V̇o2) plotted as a function of venous or microvascular Po2 (Wagner diagram). Top: a schematic illustration of the perfusive [V̇o2 = Q̇O2 (Ca − )] and diffusive (V̇o2 = DO2 × Po2) components that interact to determine peak oxygen uptake (V̇o2max). Note that the Fick principle line is not straight because it is directly reflective of the hemoglobin dissociation curve. Therefore, a left-shifted hemoglobin dissociation curve (greater hemoglobin O2 affinity), resulting in a lower venous Po2, will bisect the Fick law line earlier and will reduce V̇o2max and vice versa. The slope of the straight line emanating from the origin is determined by the diffusing capacity (DO2) of the muscle(s). What is often not appreciated within the Wagner diagram is that fractional O2 extraction (Ca − ) will be determined by the ratio of muscle diffusing capacity (DO2) to blood flow (Q̇) according to Ca − = V̇o2/Q̇O2 = Q̇O2 (), where β is the slope of the O2 dissociation curve in the physiological range (105). That the ratio DO2/Q̇ determines fractional O2 extraction explains how a high Ca − can be preserved by a very low Q̇ even in the face of a pathologically reduced DO2 as in HFrEF. Bottom: V̇o2max is plotted for individuals with chronic heart failure (HFrEF) and healthy control subjects. Note that the patients with HF (HFrEF) exhibit attenuated perfusional (Fick principle curve shifted downward) and diffusional (decreased slope of the Fick law line) conductances that contribute to the significant reductions in V̇o2max.

Although many patients with HF have a dilated left ventricle with reduced systolic function and stroke volume, it has increasingly been recognized that clinical manifestations of HF (shortness of breath and fluid overload) can be associated with a normal-sized heart and seemingly normal systolic function. Accordingly, HF is now categorized as reduced (HFrEF) vs. preserved (HFpEF) ejection fraction. HFpEF is more common in older people, women, obese individuals, and those with a history of hypertension and diabetes (8). Notably, 48% of these patients have at least five major comorbidities compared with 37% of patients with HFrEF (16). One of the most important distinctions of patients with HFpEF is that traditional pharmacological therapies used to treat HFrEF such as neurohumoral inhibition have not improved patient quality of life or survival (109). Observations in animal muscles have revealed that a substantial portion of the capillary bed does not support red blood cell flux in HFrEF, and this is believed to be responsible, in part, for the reduced DO2 and impaired blood-myocyte O2 flux (72, 104). Whether this occurs in HFpEF is not known. However, there is emerging evidence that patients with HFpEF display far lower fractional O2 extractions at maximal exercise than seen in HFrEF (24) and that compared with HFrEF, skeletal muscle atrophy and dysfunction may not be present (107). These observations suggest a very different microvascular pathology in HFpEF and quite possibly a contrasting aberration of the muscle Q̇O2-to-V̇o2 profile during exercise.

This brief review will use the eponymous “Wagner diagram” to explore the perfusive and diffusive mechanisms underlying the predations of HFrEF and HFpEF on muscle O2 transport/utilization and exercise intolerance (Fig. 1). The Wagner diagram graphically portrays the interactions of perfusive {Fick principle [V̇o2 = Q̇ (Ca − )]} and diffusive [Fick’s law of diffusion (V̇o2 = DO2 × )] O2 transport from measurements of V̇o2max and effluent muscle Po2 (), where Ca and CV are the arterial and venous O2 concentration, respectively. This formulation is powerful, in part, because it reveals the interdependence between these O2 delivery elements and their synergy that explains changes in V̇o2max in response to pathologies such as HF and also the upregulation of the O2 transport pathway with exercise training and other adaptive stressors. Key recent findings employing both human patients and animal HF models will be integrated and provide a foundation for understanding effective therapeutic interventions and identifying potentially fruitful directions for further investigation.

Two significant and somewhat common complications to interpreting the impact of HF on the O2 transport pathway are pertinent here. 1) Often only the highest V̇o2 measured on an incremental or ramp exercise test is recorded as peak V̇o2 (i.e., V̇o2peak) or incorrectly as V̇o2max. The issue here is that without a plateau of V̇o2 during further increases in work rate, the investigators cannot be certain that their measurement is the upper limit of O2 transport/utilization as opposed to lack of effort, muscular pain, premature fatigue, or other limitations incurred before V̇o2max is achieved (95c). Resorting to so-called secondary criteria such as age-predicted maximal heart rate, blood lactate, or respiratory exchange ratio to “validate” that V̇o2max was attained can substantially underestimate the true V̇o2max (97). This situation is unfortunate because imposition of a brief exhausting exercise bout at a work rate higher than that reached on the incremental/ramp test can be used in patients with HF and yield an unequivocal V̇o2max (14, 95c). 2) Often systemic measurements of cardiac output and fractional O2 extraction (i.e., arterial-venous O2 content) are presumed incorrectly to discriminate between so-called central (i.e., cardiac) vs. peripheral (i.e., muscle) dysfunction. This issue and its impact on data interpretation are detailed below in the section entitled Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction.

O2 Supply and Demand Limitations in Patients with HFrEF: Large vs. Small Muscle Mass Exercise

Studies of exercise limitation in HFrEF have predominantly used standard cycle ergometry, resulting in the recruitment of most of the lower limb musculature as well as some upper body muscles to accomplish the work (Fig. 2, top; Refs. 98, 99). With the lowered maximal cardiac output associated with HFrEF, involvement of such a large muscle mass is thought to be the major factor limiting exercise tolerance in this population. It has previously been recognized that skeletal muscle function and plasticity in HFrEF may be better assessed by changing exercise modality from conventional cycle exercise to a small muscle mass exercise, such as single-leg knee extension (Fig. 2, bottom; Refs. 4, 81, 82, 98, 120, 121). However, identifying the role of centrally limited O2 supply vs. compromised peripheral O2 utilization (15, 125) using this approach in both healthy matched controls and patients with HFrEF had, until relatively recently (28), never been attempted.

Fig. 2.

A schematic representation of the relatively small ratio of cardiac capacity to skeletal muscle recruitment during standard cycle ergometry (top), the much greater ratio during single-leg knee extension (bottom), and the subsequently contrasting physiological responses to these exercise paradigms. Arrows designate relative change from resting.

Evidence of a skeletal muscle metabolic reserve.

As revealed by assessment of cardiac output during both cycle and knee-extension (KE) exercise (28), switching from large to small muscle mass exercise, a cardiac reserve (the ability to increase cardiac output to meet metabolic demand) becomes available to both patients with HFrEF and controls during KE exercise. With this important proof of concept in place, measurement of one-leg V̇o2peak and subsequent normalization to recruited muscle mass (98) during KE exercise unveils a muscle Q̇ and metabolic reserve (the ability of the muscle to meet energetic demand via oxidative metabolism) in patients with HFrEF and controls (28). This finding in patients with HFrEF was identical to that of controls, presumably as a consequence of the documented cardiac reserve for this exercise modality. There is extensive evidence for HFrEF inducing a shift in skeletal muscle fiber type distribution toward more type II/IIb as well as reducing oxidative capacity and mitochondrial volume density and enzymes consequent to muscle atrophy, myopathy, or both (26, 48, 85, 86). Therefore, in this population, it is important to note that a metabolic reserve remains at maximal exercise, as exposed clearly by freeing the skeletal muscle from the restraints imposed by the failing heart using KE exercise.

This skeletal muscle metabolic reserve was also demonstrated when patients with HFrEF increased their V̇o2peak 7% by breathing 100% O2 (i.e., raised arterial O2 content) during maximal cycle (5% increase in power) but not KE exercise (28). This contrasted with the healthy controls who failed to increase V̇o2peak above that attained in normoxia in either modality (28). This observation suggests that in patients with HFrEF, O2 supply to the skeletal muscle is limited during cycling exercise, a condition not extant during KE. This differential response may be due to the fact that Q̇O2 per unit muscle mass is already elevated during KE. The control subject responses were consistent with the literature in terms of healthy but sedentary human muscle failing to improve when provided with greater O2 availability (15, 125), suggesting ambient O2 levels are either perfectly matched or in excess of metabolic capacity.

Contribution of perfusive and diffusive O2 transport in limiting V̇o2peak.

The contributions of perfusive (bulk Q̇O2) and diffusive (movement of O2 from hemoglobin to mitochondria; Fig. 3) elements in determining V̇o2peak in patients with HFrEF was recently partitioned (28). Specifically, as detailed in introduction, the Wagner diagram presents the interactions of perfusive and diffusive O2 transport in a model that links maximum V̇o2 and effluent muscle Po2 () to explore maximal exercise limitations (Fig. 4; Ref. 125). For cycle exercise, if the only difference between the controls and the patients with HFrEF was the reduced perfusive component of O2 transport (reduced cardiac output), then V̇o2peak would fall from A to B (15). However, in addition to the lower perfusive component of O2 transport, the patients with HFrEF also have an attenuated DO2 (diffusive component) resulting in a greater fall in V̇o2peak from A to C (Fig. 4). Exactly the same schematic illustrates the KE exercise studies because, despite that cycle exercise was undoubtedly completely taxing cardiac output capacity and KE exercise had a cardiac reserve, both the perfusive and diffusive components of O2 transport of the patients with HFrEF were diminished in each exercise model (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Top: schematic illustration of Fick’s law applied to blood-myocyte O2 transport within the skeletal muscle microcirculation. Po2mv constitutes the main driving pressure for transmembrane O2 flux given that intracellular Po2 (Po2intracel) approximates 0 during contractions [approximately 1–3 mmHg; particularly during maximal exercise (101)]. The direct consequence of reduced Po2mv with HFrEF is thus impaired blood-myocyte O2 transport. [Adapted from Hirai et al. (57).] DO2m, muscle O2 diffusing capacity; in, interstitium; p, plasma; RBC, red blood cell; V̇o2; O2 flux. See main text for further details. Bottom: spinotrapezius muscle microvascular Po2 (Po2mv) profiles during the rest-contraction transient in healthy and HF rats with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Note that HFrEF speeds the kinetics of Po2mv fall, thus lowering muscle microvascular oxygenation across the transient (blue area). Time 0 denotes the onset of contractions. Arrow designates the lowering of microvascular Po2 by HFrEF during contractions. [Adapted from Poole et al. (95b).]

Fig. 4.

A schematic representation of the perfusive (Q̇O2) and diffusive (DO2) components that interact to determine V̇o2peak in patients with HFrEF and healthy controls during both cycle (large muscle mass) and knee-extensor (KE; small muscle mass) exercise. Note, if reductions in V̇o2peak in HFrEF were entirely due to reductions in Q̇O2, then the response would follow from point A to B (without any change in the DO2). However, the reductions in V̇o2peak for both cycle and KE exercise in HFrEF were found to follow from point A to C. With this scenario, reductions in DO2 also contributed to the reductions in V̇o2peak in HFrEF as demonstrated by the changes in the slope of the line from B to C. These reductions in DO2 occurred in HFrEF without any demonstrable change in muscle venous Po2 (or muscle venous O2 content) and thus without any changes in arterial-venous O2 content difference.

These apparently common limitations in what appear to be very different maximal exercise scenarios (cycle and KE exercise) discriminate important functional peripheral difference between controls and patients with HFrEF. Specifically, with their measured cardiac output capacity during cycle exercise (28), the patients with HFrEF were expected to match, but could not, the KE Q̇ of the controls (28). We considered that this reduced Q̇ and Q̇O2 resulted from an elevated norepinephrine spillover for KE exercise that was also apparent during cycle exercise (Fig. 4; Ref. 28). As for this and many other previous studies, the potential role of heart failure medications (only β-blockers were discontinued) to influence this peripheral muscle Q̇ response cannot be dismissed. Importantly, animal investigations can circumvent these confounding effects and shed further light on these issues.

To understand better the diffusive O2 transport differences between patients with HFrEF and healthy controls, it is important to note the similarity in arterial-venous O2 difference that occurred in the presence of an attenuated DO2 (28). This was the consequence of the lower blood flow of the patients with HFrEF that permitted a longer capillary transit time for O2 offloading. However, the DO2 estimation (which is expressed per unit of time) takes this longer period for gas exchange into account revealing that, despite the adoption of a small muscle mass exercise model, DO2 remained significantly attenuated in the patients with HFrEF (Fig. 4). This distinction between arterial-venous O2 extraction (which is the result of both perfusive O2 delivery and diffusive O2 transport) and DO2 (which is solely a consequence of diffusive O2 movement) provides important mechanistic insight into the limitations to O2 transport specific to patients with HFrEF. Indeed, these data reveal that during both cycle and KE exercise, the patients with HFrEF exhibit an attenuated ability for diffusive O2 transport from blood to myocytes, and this contributes to the reduction in exercise capacity in both large and small muscle mass exercise scenarios.

O2 supply and demand limitations in patients with HFrEF: insight from small muscle mass exercise training.

Traditional cardiac rehabilitation has employed whole body exercise, which challenges a large muscle mass and therefore taxes the central circulation (30, 37, 50, 94, 95b). This approach has consistently yielded significant improvements in exercise capacity in patients with HFrEF (45, 94). However, as whole body exercise induces a complex interaction between central hemodynamic and peripheral responses, such an observation clouds the respective roles of central and peripheral adaptations to exercise training. In an attempt to address this uncertainty, several studies have employed small muscle mass training, which was considered unlikely to stimulate central hemodynamic adaptations, and then challenged the patients with whole body exercise (81, 120, 121). Although this innovative approach has revealed that muscle-specific training can indeed improve whole body exercise capacity in patients with HFrEF (81, 120, 121), the indirect physiological assessments used in these studies mean that the mechanisms responsible for this positive outcome had, until recently (28), escaped recognition.

Small muscle mass exercise training-induced changes in O2 transport.

Previously, building on our (96, 104) initial work in a rat model of HFrEF, the contributions of both the perfusive and diffusive elements in determining V̇o2peak were documented in patients with HFrEF (28). These findings were then contrasted with age- and activity-matched healthy controls. Subsequently, the effect of small muscle mass (KE) exercise training (no change in maximal cardiac output) on the perfusive and diffusive components of O2 transport was determined in patients with HFrEF and contrasted with healthy age- and activity-matched controls (28). Surprisingly, the deficits in Q̇O2 and DO2 attenuating V̇o2peak in patients were evident equally at cycle and KE maximal exercise. Importantly, after 8 wk of KE training, KE V̇o2peak of patients with HFrEF matched or exceeded that of normal healthy, but untrained, controls. This demonstrated that the muscles of the patients with HFrEF retained considerable adaptive plasticity for O2 transport and utilization (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 5.

Improvement in skeletal muscle diffusional conductance (DO2) in relation to leg V̇o2peak during maximal cycle and knee-extensor (KE) exercise afforded by 8 wk of KE training in patients with HFrEF compared with healthy sedentary controls. Note, the correlation coefficient only represents the relationship between the individual data.

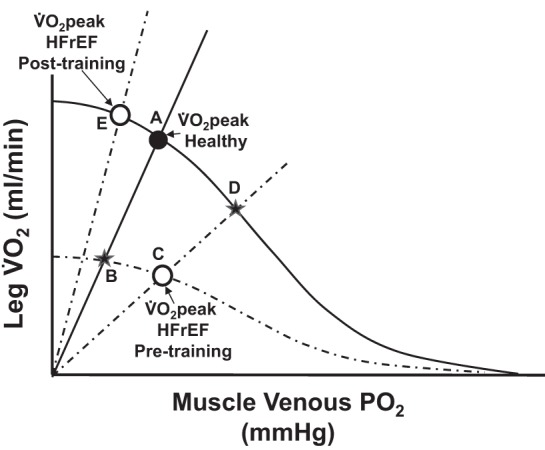

Fig. 6.

A schematic illustration of the perfusive and diffusive components that interact to determine leg V̇o2peak in both HF (HFrEF) and control subjects during cycle (large muscle mass) and knee-extensor exercise (KE; small muscle mass) and the subsequent changes as a consequence of KE training. Solid lines represent Fick’s law and principle lines for the healthy sedentary controls (intersecting at A; V̇o2peak Healthy), whereas the dotted lines represent the patients with HFrEF. Following training, both groups share the solid Fick principle line. In both exercise modalities, before training, the patients with HFrEF exhibited attenuated perfusive and diffusive oxygen transport as evidenced by their V̇o2peak being defined by the intercept of lower Fick’s law and principle lines (C) with B indicating the less severe reduction in V̇o2peak had the patients only revealed a reduction in perfusive O2 transport. KE training corrected both of these deficits, without increasing cardiac output, restoring both skeletal muscle perfusive and diffusive O2 transport and therefore allowing V̇o2peak to equal or exceed (KE) that of the healthy sedentary controls (E). D represents the consequence of exercise training if the increase in V̇o2peak had only been driven by an increase in perfusive O2 transport (C to D).

Again, the Wagner diagram helps us appreciate that before exercise training, both the perfusive and diffusive components of O2 transport of the patients were attenuated, regardless of exercise modality (Figs. 4 and 6). Consequent to KE training, these were restored for both modalities in a similar fashion. Specifically, before KE training, it can be seen in Fig. 6 that if the only difference between the controls and the patients with HFrEF was the reduced perfusive component of O2 transport, then V̇o2peak would have fallen from A to B as a result of this pathology (15). However, in addition to the lower perfusive component of O2 transport, the patients with HFrEF also revealed a significantly attenuated DO2 (Figs. 4–6) that induced an even greater fall in V̇o2peak from A to C (Fig. 6). Exercise training resulted in both a Q̇-driven increase in perfusive O2 transport (C to D) and the restoration of DO2 to that of controls (C to B) or higher (overall increase from C to E), which drove the substantial increase in V̇o2peak (Figs. 5 and 6).

These findings have several important implications. First, patients with HFrEF exhibit plasticity in their ability to respond to exercise training both in terms of increases in skeletal muscle Q̇ and diffusional O2 transport. Second, both of these KE training-induced adaptations (augmented peripheral perfusive and diffusive O2 transport) translate into improvements in whole body exercise capacity (cycle) of patients with HFrEF without a requisite improvement in cardiac function.

Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction

Scope of the problem.

As with HFrEF, the hallmark symptom in clinically stable patients with HFpEF is severe exercise intolerance, measured objectively as decreased V̇o2peak, and is associated with reduced quality of life and survival (75, 108). Given the lack of effective pharmacological treatment options, understanding the role of skeletal muscle(s) in exercise intolerance in the burgeoning population of older patients with HFpEF is of great importance.

Determinants of impaired V̇o2peak: role of HF phenotype.

The mechanisms responsible for the reduced V̇o2peak may differ between patients with HFrEF and patients with HFpEF (Table 1; Refs. 24, 38). An invasive hemodynamic study by Katz et al. (68) reported that peak exercise femoral vein O2 content was significantly lower in severely deconditioned (V̇o2peak <14 ml·kg−1·min−1) patients with HFrEF compared with patients with HFpEF. Notably, near-complete O2 extraction (femoral vein O2 ≤1.1 ml/dl) was reported in two patients with HFrEF with a V̇o2peak <12 ml·kg−1·min−1. More recently, Dhakal et al. (24) compared patients with HFpEF with patients with HFrEF during maximal upright cycle exercise using invasive right heart and radial arterial catheterization coupled with gas analyses. V̇o2peak (absolute or indexed to body weight), cardiac output (index), stroke volume (index), mean arterial pressure, and mixed venous oxygen content were significantly higher in HFpEF, whereas peak exercise systemic Ca − difference was significantly lower (also see Ref. 38).

Table 1.

Acute hemodynamic responses during maximal whole body exercise: role of HF phenotype

| Variable | HFrEF vs. HFpEF |

|---|---|

| V̇o2, l/min | ↓ (24, 75) |

| V̇o2, ml·kg−1·min−1 | ↓ (24), ↔ (38, 68, 75) |

| Cardiac output, l/min | ↓ (24) |

| Cardiac index, l·min−1·m−2 | ↓ (24, 38) |

| Stroke volume, ml/min | ↓ (24) |

| Stroke volume index, l·min−1·m−2 | ↓ (24, 38) |

| Heart rate, beats/min | ↔ (24, 68, 75) |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | ↓ (24, 38), ↔ (68) |

| Arterial O2 content, ml/dl | ↔ (24) |

| Mixed venous O2 content, ml/dl Femoral venous O2 content, ml/dl |

↓ (24) ↓ (68) |

| Arterial-venous O2 content difference, ml/dl | ↑ (24, 38) |

As seen graphically in Fig. 4, the high fractional O2 extraction in HFrEF does not mean that muscle O2 diffusing capacity (DO2) is either normal or enhanced. Rather, as fractional O2 extraction is determined principally by the ratio of DO2 to Q̇ [DO2/Q̇ (99)], extremely low muscle Q̇ will increase fractional O2 extraction even in the face of a reduced DO2 (see Muscle Microcirculation section below for a detailed explanation). Accordingly, Wilson and colleagues (127) reported that those patients with HFrEF with the lowest maximal exercise cardiac output and muscle Q̇ also had the highest leg fractional O2 extraction. It is possible that the decreased O2 extraction in HFpEF vs. HFrEF may be the result of even poorer capillary hemodynamics (decreased proportion of capillaries sustaining red blood cell flux, decreased hematocrit, and/or aberrant Q̇O2/V̇o2 matching), but this remains to be investigated.

Differential muscle Q̇ and oxygenation response to exercise in HFrEF and HFpEF.

To date, only a few studies have compared lower-extremity vascular function and exercise leg Q̇ in clinically stable patients with HFrEF and patients with HFpEF. Hundley et al. (63), using phase-contrast MRI, measured flow-mediated dilation in the superficial femoral artery in response to 5 min of cuff ischemia (an endothelial-dependent stimulus) in 10 patients with HFrEF (mean age: 74 yr, V̇o2peak: 12 ml·kg−1·min−1), 9 patients with HFpEF (mean age: 73 yr, V̇o2peak: 13 ml·kg−1·min−1), and 11 healthy control subjects (mean age: 71 yr, V̇o2peak: 20 ml·kg−1·min−1). The major finding was that superficial femoral artery flow-mediated dilation was significantly reduced in HFrEF vs. HFpEF and controls and was positively associated with V̇o2peak in HFrEF and controls (63). Accordingly, the significantly higher V̇o2peak (~200 ml/min) during upright cycle exercise in patients with HFpEF vs. patients with HFrEF (24, 75), may be due, in part, to greater maximal muscle Q̇ as a result of less severe peripheral arterial endothelial (or microvascular) dysfunction. In this case, the reduced fractional O2 extraction would be driven by the elevated Q̇ (i.e., DO2/↑Q̇) whether or not DO2 was reduced to the same extent in HFpEF as HFrEF. In addition, Thompson et al. (119) recently reported significantly faster leg V̇o2 and leg Q̇ kinetics in the recovery period following submaximal one-leg KE in patients with HFpEF vs. patients with HFrEF (mean response time, MRT: 47 vs. 95 s, and MRT: 135 vs. 292 s, respectively). It is crucial to appreciate, however, that maximal leg Q̇ during KE is reduced in patients with HFpEF compared with healthy controls, implicating impaired muscle vasodilatory function (5, 78), but this effect does not appear to be as severe as for HFrEF. Intriguingly, the ~25% lower leg Q̇ in HFpEF occurred while cardiac output was >70% higher than in HFrEF, such that a clear maldistribution of cardiac output was present (78).

Whether excessive sympathoexcitation occurs in HFpEF and, if it does, whether it is similar to that found in HFrEF (134) has not been determined. If hypersympathoexcitation is present in HFpEF, it is by no means certain that the degree of chronic vasoconstriction produced in the small feed arteries and arterioles of muscle would be similar between HFpEF and HFrEF. Such differences in vasoconstrictive tone would impact the effects of HFpEF on the magnitude of the overall Q̇ response to exercise (i.e., differences in the balance of vasoconstrictors vs. vasodilators) and, crucially, the distribution of that Q̇ among organs and between and within skeletal muscles. Both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system, and in HFrEF sympathoexcitation elevates norepinephrine in association with increased tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α (12)]. Elevated cytokines, especially TNF-α, downregulate endothelial nitric oxide expression and impair endothelial nitric oxide stability (3, 122), compromising NO production and bioavailability. Interestingly, the vasodilatory capacity of arteriolar vascular ATP-sensitive K+ channels appears to be preserved in HFrEF (61), but, nonetheless, the contracting muscles experience a severely blunted Q̇ response to exercise consequent to increased active vasoconstriction and decreased NO bioavailability (95b). Far less is known regarding the pathology of arteriolar function in HFpEF than HFrEF. Thus there is the likelihood that the distinctly different Q̇ distributions found in HFpEF vs. HFrEF result from a unique pattern of dysfunctional arteriolar regulation that remains to be defined in patients with HFpEF.

O2 supply and demand limitations in patients with HFpEF.

All previous investigations into the limitations to V̇o2peak in patients with HFpEF, compared with controls, have utilized whole body measurements of venous O2 content (), arterial-to-venous O2 content difference (Ca − ), or venous partial pressure of O2 () during maximal exercise to “determine” the peripheral limitations to V̇o2peak (1, 10–12, 24, 49, 74). Use of these systemic measurements has likely contributed to the equivocal nature of the findings from these studies, with evidence supporting both the presence (10, 24, 49, 74) and absence (81, 86, 97) of peripheral limitations to V̇o2peak. This is because such measurements do not actually allow for the peripheral limitations to be resolved, as Q̇O2 and DO2 are necessarily assessed and interpreted in an integrative manner (Figs. 4 and 6). Specifically, because fractional O2 extraction is determined by the ratio of muscle DO2 to Q̇ (which is implicit in the Wagner diagram), pathologically lowered muscle Q̇ can elevate fractional O2 extraction even when DO2 is compromised. A similar issue was previously evident in the initial studies of patients with HFrEF, where or measurements were interpreted as evidence for peripheral limitations not influencing exercise tolerance and that the sole limitation resided in cardiac dysfunction (68, 126). This misinterpretation endured until investigations using the rat myocardial infarction model of HFrEF demonstrated severe microcirculatory dysfunction that would predicate a very low DO2 (72, 104). Subsequently, a series of studies assessed the peripheral limitations to V̇o2peak in these patient populations and revealed that, despite normal , Ca − , and values, DO2 was greatly (~30%) diminished in patients with HFrEF (Refs. 28, 29; Fig. 4). There are extensive differences between HFrEF and HFpEF phenotypes (50). Given that cardiac-focused therapies have proven largely unsuccessful in HFpEF (37, 132), it is crucial to assess accurately whether peripheral limitations to V̇o2peak, and therefore exercise tolerance, are present in these patients and, if so, their mechanistic bases.

What can be concluded at present is that the diminished V̇o2peak in patients with HFpEF (as for patients with HFrEF) is the consequence of an attenuation of both whole body Q̇O2 and DO2. The evidence that leg Q̇O2 may be less affected in HFpEF than HFrEF (63, 78) suggests that peripheral limitations to V̇o2peak, especially as regard DO2, are very likely to be present in HFpEF. However, their extent and the balance between structural or functional alterations remain to be determined. What is intriguing is that previous evidence in rat soleus muscle indicates that, with respect to fiber atrophy and oxidative function, HFpEF are far less affected than HFrEF (107). Moreover, the success of acute nitrate-based therapeutic interventions in patients with HFpEF to increase V̇o2peak and muscle function indicates a deranged vascular functional component (132). From the above, it is evident that comprehensive investigations of muscle Q̇O2 and DO2 at maximal exercise are needed to evaluate muscle dysfunction in HFpEF as has been performed in HFrEF. It is hoped that this approach will help identify unique therapeutic strategies for the patient with HFpEF.

Muscle Microcirculation

As presented above, principally because HFrEF increases fractional O2 extraction at a given metabolic rate (V̇o2), until quite recently it was erroneously considered that muscle DO2 was preserved in HF. However, the previous sections have demonstrated that HF (HFrEF and HFpEF) causes a substantial deficit in muscle function and that, at least for HFrEF, there is clear evidence for both impaired perfusional (Q̇O2) and diffusional (DO2) conductances as evident from the Wagner diagram (Fig. 4; Refs. 57, 95b). Based on experimental studies in animals, we will now consider microcirculatory function as a foundation for appreciating how HFrEF affects skeletal muscle to delineate the mechanistic bases for 1) reduced DO2, 2) inability to match Q̇O2 to V̇o2 effectively, and 3) why, unlike HFrEF, HFpEF may result in lowered fractional O2 extraction. Subsequently, this will allow exploration of how nitric oxide-based therapeutic strategies and also exercise training may function to improve exercise tolerance and muscle V̇o2, thereby increasing patient quality of life and reducing morbidity/mortality in HF.

How the muscle microcirculation functions in health.

As diametrically opposed to the Kroghian theory where the majority of capillaries are “closed” in resting muscle and therefore can be recruited during contractions, multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that most (>80%) of capillaries support red blood cell (RBC) flux in resting muscle (95a). Thus the increased Q̇O2 and DO2 during contractions necessary for enhanced blood-myocyte O2 flux can occur by means of elevated RBC velocity primarily in already-flowing capillaries, increased capillary hematocrit [from ~15% toward the 45% seen systemically (73)], and a longitudinal recruitment of capillary endothelial surface area by extending the length of capillary that becomes functionally important for blood-myocyte O2 flux (95a). Whereas mean capillary Po2 falls from rest to exercise, intramyocyte Po2 decreases to just 2–3 mmHg (101), which helps preserve the blood-myocyte O2 gradient. The endothelial surface layer (termed glycocalyx by some) is considered important for controlling RBC velocity and hematocrit, but its precise role in health and disease remains to be defined (95a, 135). Similarly, whereas myoglobin historically is touted to improve intramyocyte O2 diffusion, the demonstration that genetically engineered mice without myoglobin can survive (albeit with enlarged hearts, increased capillarity, and increased hematocrit) and exercise reasonably well question its overriding importance (39). New discoveries regarding the role of intracellular membranes in facilitating intramyocyte O2 transport also challenge existing paradigms in this regard (17).

Impact of HF on muscle microcirculation.

Although HF causes a modicum of capillary involution and shifts toward a greater fast-twitch fiber population, the primary deficits appear to be functional rather than structural (57, 95b, 104, 130). Thus there is a correlation between the elevated cardiac filling pressures (i.e., left ventricular end-diastolic pressure) and infarction size and the proportion of the capillary bed that does not support RBC flux either at rest (72) or, crucially, during contractions (73, 104). This contention is reinforced by the reduced impact of the nonspecific nitric oxide synthase enzyme inhibitor NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) to decrease locomotory muscle Q̇O2 in HF (59, 60), the restoration of healthy microvascular Po2 profiles (and thus Q̇O2-to-V̇o2 matching) during muscle contractions by exogenously applied NO (25, 36), and the improvements in locomotory muscle Q̇ during running found after inorganic supplementation in HF rats (34, 42). Human studies in healthy individuals have determined that supplementation improves muscle oxygenation, V̇o2 kinetics, and exercise tolerance (65, 66). Of note, these effects are also present in patients with HF (HFrEF) when treated with the PDE inhibitor sildenafil (116). That muscle and microvascular Po2s fall much faster (and to far lower levels) in HF following the onset of exercise (25) and that this effect is countered by improved NO bioavailability (36) and PDE inhibition (116) at least, in part, by elevated muscle Q̇O2 (34, 42) helped inspire investigation of nitrate supplementation in patients with class III/IV HF (HFpEF). Thus that HF places skeletal muscle and V̇o2 kinetics in the Q̇O2-dependent domain dictates that enhanced muscle Q̇O2 has substantial potential to improve exercise energetics (95b).

If patients with HF recruit proportionally more fast-twitch fibers, the active skeletal muscle (or regions thereof) would be expected to have an inherently lower microvascular Po2 (6). Moreover, impaired HF-induced Q̇O2-to-V̇o2 mismatch will compound this effect (25, 57). Consequently, during exercise, the locomotor muscles will provide the necessary environment for the final reduction to NO (32–35). Accordingly, Zamani and colleagues (132) used a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover experimental design to assess the potential for a single dose of 12.9 mM delivered as beetroot juice to improve cardiovascular function and exercise performance in HFpEF. This single-dose treatment demonstrated that supplementation reduced systemic vascular resistance and elevated cardiac output, increasing both V̇o2peak and exercise performance significantly. Thus the potential was identified for longer-term therapy to improve cardiac rehabilitation outcomes and reduce recidivism. However, there was the concern that repeated treatment would lead to tolerance (as seen for isosorbide dinitrate, an organic ) and potentially methemoglobinemia. To help resolve these concerns, Zamani et al. (133) dosed patients with HFpEF for 3 wk with up to 18 mM /day and demonstrated improved exercise economy and performance. Unfortunately, the blood sampling routine required to establish the / pharmacokinetics negated any significant increase in V̇o2peak. However, administration of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire evidenced that their overall symptoms were improved as was their exercise economy and capacity and crucially that concerns regarding methemoglobinemia and/or tolerance were unfounded.

Collectively, this evidence supports that skeletal muscle represents an important locus of pathology and exercise dysfunction in HFpEF. Thus targeting improved NO bioavailability via supplementation improves muscle perfusive (and potentially diffusive) O2 conductance increasing muscle O2 transport and elevating exercise capacity. These effects may translate to improved adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs and also general physical activity, both of which are key to restoring the quality of life and decreasing morbidity and mortality in HF.

Key muscle microcirculatory questions in HF.

By definition, the inability for a substantial proportion of the capillary bed to support RBC flux will decrease the number and volume of RBCs in close approximation to the myocytes (104), which is a primary determinant of muscle DO2 (31, 95a) and may account for the very low DO2 found in HF muscles (Fig. 4). In addition, without these capillaries supporting RBC flux, the vascular resistance arising from the capillary bed will increase and, in concert with impaired arteriolar vasodilation [increased sympathetic tone and lack of sensitivity to and decreased concentration of vasodilators including NO bioavailability (95b)], will contribute to a reduced perfusive Q̇O2 (Fig. 4). This situation will be exacerbated by any venous congestion resulting from fluid retention due to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation and the elevation of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (87). All of these effects will presumably detract from the ability to match Q̇O2 to V̇o2 within and across contracting muscles (53), helping explain the low DO2 in both patients with HFrEF and patients with HFpEF and providing clues to the reduced fractional O2 extraction seen exclusively in HFpEF (49). In this regard, it is pertinent that the slow twitch soleus muscle in rats with HFpEF is relatively well-preserved compared with HFrEF, demonstrating less atrophy, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction in conjunction with a different profile of circulating inflammatory cytokines (107). In and of themselves, these differences cannot explain the lowered fractional O2 extraction seen in HFpEF vs. HFrEF, highlighting the need for microvascular and muscle oxygenation intravital studies in HFpEF muscles.

Exercise training remains a key rehabilitation technique in patients with HF (37, 40). There is growing hope that therapeutic strategies that target the NO pathways (/ supplementation, PDE inhibitors, and possibly the latest-generation soluble cGMP activators that invoke vasodilation downstream from NO) will prove valuable adjuncts to helping to improve the efficacy of exercise training. Central to that mission is determining to what degree each of these therapeutic strategies restores skeletal muscle Q̇O2 and DO2, capillary hemodynamics, and Q̇O2-to-V̇o2 matching.

Exercise Training in Chronic Heart Failure: Skeletal Muscle Microvascular Adaptations

The rise of exercise training in the treatment of heart failure.

Exercise training is a powerful nonpharmacological strategy to remediate skeletal muscle O2 transport and utilization impairments in HF (51, 57). Indeed, a wealth of evidence today supports the adoption of training and cardiac rehabilitation in the treatment of patients with HF (7, 19, 20, 37, 38, 46, 46a, 118). However, such exercise-based clinical practice was not formally introduced until approximately 30 years ago following the publication of the first randomized controlled trials in the early 1990s (18, also see 117, 118). Before this paradigm shift in the clinical management of the disease, physical activity restriction and bed rest were endorsed for virtually all patients with HF irrespective of their disease severity (e.g., 88, 89). The clinical relevance of exercise training rests on the fact that, despite the vast array of pharmacological options available currently to the patient with HFrEF, unlike exercise training (19, 29, 38, 46, 46a, 118), drug treatment has failed to reverse deficits in skeletal muscle oxygenation and improve exercise tolerance appreciably (7, 115). Evidence to date suggests that the physiological mechanisms underpinning these improvements differ between patients with HFrEF and patients with HFpEF. Specifically, whole body or small muscle mass training is associated with favorable cardiovascular and skeletal muscle adaptations that result in increased Q̇O2 and extraction by the exercising muscle in HFrEF (19, 29, 38, 46, 46a, 118). In contrast, the exercise training-mediated increase in V̇o2peak in patients with HFpEF is primarily due to peripheral skeletal muscle-vascular adaptations that result in increased O2 extraction by the active muscle (38, 50). In summary, evidence to date suggests that the contribution that central and peripheral mechanisms play in limiting V̇o2peak and their improvement with exercise training are dependent on HF phenotype. Exercise training plays an especially important role in the clinical care of HFpEF (73a, 93) given that medication trials have failed to improve clinical outcomes and currently no effective pharmacological treatment is available for these patients (52, 95, 111).

Mechanistic insight into HF-induced microvascular impairments.

The HF syndrome is associated with multiple impairments along the O2 transport pathway from the lungs down to skeletal muscle mitochondria (52, 95b). Within the microcirculation, dynamic mismatch between Q̇O2 and V̇O2 drastically reduces muscle microvascular Po2 during transitions in metabolic demand (25) and, consequently, impairs the driving force for blood-myocyte O2 transfer according to Fick’s law of diffusion (Fig. 3). This has profound negative consequences on muscle oxidative metabolism and contractile performance (62, 95b) and constitutes a major contributor to poor exercise tolerance in patients with HF [HFrEF (115)].

As detailed above, functional rather than structural impairments appear to account for most of the pathological microvascular Po2 profile during muscle contractions in HFrEF. Accordingly, pharmacological manipulation of the NO vasodilatory pathway with l-NAME reduces NO bioavailability and replicates the HFrEF condition in healthy muscle [i.e., by reducing microvascular Po2 and speeding its fall during contractions (36)]. On the other hand, increased NO bioavailability with the donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) in HFrEF muscle elevates microvascular Po2 and slows its dynamic fall during contractions, mimicking healthy muscle responses (36). These data are consistent with intrinsic endothelium dysfunction and impaired NO-dependent vasodilation during contractions in HF skeletal muscle (60, 67, 78) and suggest that increased NO bioavailability following exercise training (2, 45, 123) could help reverse aberrant microvascular Po2 responses.

Exercise training in the treatment of microvascular oxygenation deficits in HFrEF.

Skeletal muscle plasticity is preserved in HFrEF such that improvements in perfusive and diffusive O2 transport are evident with exercise training (Figs. 5 and 6; Refs. 29, 56). These adaptations hold important clinical implications for their potential to oppose the pathophysiological consequences of HF on microvascular Q̇O2 [i.e., reduced RBC flux and proportion of RBC-flowing capillaries in the case of HFrEF (72, 104)]. Improved perfusive and diffusive O2 conductances support faster rates of oxidative phosphorylation (i.e., faster V̇o2 kinetics) and minimize the reliance on anaerobic glycolysis and finite energy sources during contractions in trained HF muscle (57, 95b). As a result, attenuated perturbations of the intracellular environment of contracting skeletal muscle (e.g., changes in phosphocreatine, creatine, and ADP concentrations and pH) contribute to greater exercise tolerance in these patients after training (57, 95b).

We have employed the rat model of HFrEF [via myocardial infarction induced by left coronary artery ligation (91)] to investigate the effects of exercise training on skeletal muscle microvascular function and identify mechanisms underlying improved exercise tolerance in this disease (56). Figure 7, top, illustrates that endurance exercise training elevates effectively microvascular Po2 at the onset of submaximal contractions (i.e., slowed Po2mv kinetics) in HFrEF muscle. As the time course of microvascular Po2 is directly proportional to the dynamic Q̇O2/V̇o2 matching, slower Po2mv on-kinetics with training reveals a faster rate of adjustment in capillary Q̇O2 during contractions in trained compared with sedentary HFrEF rats (25, 56). Critical to understanding the mechanisms underpinning these responses, the relative contributions of both perfusive and diffusive O2 transport to enhanced microvascular Po2 (i.e., reduced fractional or %O2 extraction) after training can be resolved based on the relationship below describing their interdependence (105):

where DO2 is muscle O2 diffusing capacity, β corresponds to the slope of the O2 dissociation curve in the physiologically relevant range, and Q̇ is muscle blood flow. Given that β is unlikely to be impacted appreciably by HF and/or exercise training, alterations in fractional O2 extraction (and, therefore, microvascular Po2) will depend chiefly on the DO2/Q̇ ratio. In this sense, slower microvascular Po2 on-kinetics in trained HFrEF rats is indicative of reduced DO2/Q̇ ratio and suggests that adaptations in perfusive (Q̇; mainly RBC flux) rather than diffusive O2 transport (DO2) are relatively greater and contribute more to enhancing contracting muscle microvascular oxygenation in this disease (56).

Fig. 7.

Top: spinotrapezius muscle microvascular Po2 (Po2mv) profiles during the rest-contractions transient in sedentary and endurance exercise-trained HF rats with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Time 0 denotes the onset of contractions. SE bars are omitted for clarity. The inset displays the overall dynamics of Po2mv fall during contractions (mean response time; MRT) in sedentary (S) and exercise-trained (T) HFrEF rats. Note that exercise training slows Po2mv kinetics (↑MRT), thus increasing muscle microvascular oxygenation across the transient (red area). Gray arrow demonstrates training effect. Bottom: changes in muscle microvascular oxygenation (ΔPo2area) with SNP and l-NAME in sedentary and exercise-trained HFrEF rats. ΔPo2area is calculated as the difference in the area under the Po2mv curve between control and SNP or l-NAME superfusion conditions. Note the lack of differences in ΔPo2area between sedentary and exercise-trained HFrEF rats with l-NAME. This is consistent with the nonobligatory role of NO in microvascular oxygenation adaptations to exercise training in HFrEF skeletal muscle. [Adapted from Hirai et al. (57).] l-NAME, NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (nonspecific NO synthase blocker); SNP, sodium nitroprusside (NO donor). *P < 0.05 vs. sedentary HFrEF. See main text for further details.

Role of NO in microvascular oxygenation adaptations to training in HFrEF.

As noted above, alterations in NO bioavailability modulate the dynamic Q̇O2/V̇o2 matching during metabolic transitions in health and disease (95b). In HFrEF muscle, impairments in NO-mediated function contribute to blunted functional hyperemia (60, 67) and microvascular oxygenation deficits (36, 117) during muscle contractions. Conversely, exercise training is capable of combating many of the disturbances caused by HFrEF (57) and ameliorates NO-induced vasodilation by elevating endogenous NO bioavailability (45, 123). In agreement with this notion, our (55) previous studies in healthy muscle demonstrate that exercise training elevates microvascular oxygenation across the rest-contraction transient (i.e., slower Po2mv kinetics) partly via enhanced NO mechanisms.

Based on these observations, the specific functional role of NO on microvascular oxygenation adaptations to training in HFrEF was investigated under SNP and l-NAME superfusion conditions. This approach revealed that increased NO bioavailability with SNP slowed the overall dynamics of the Po2mv fall in both sedentary and trained HFrEF rats, whereas decreased NO bioavailability with l-NAME had no effects on Po2mv kinetics in either group relative to the respective control condition (56). The latter responses contrast markedly with those observed in healthy rats, in which l-NAME abolished the differences in microvascular oxygenation between sedentary and trained animals evident during the control condition (55). Taken together, these data indicate that although exercise training improves Q̇O2/V̇o2 matching in both health and disease, different mechanisms control such adaptations at the level of the muscle microcirculation. In HFrEF muscle, improved NO-mediated function might not be obligatory to improve microvascular oxygenation (i.e., slow microvascular Po2 kinetics) and to increase the driving pressure for blood-myocyte O2 flux during contractions (56). Figure 7, bottom, summarizes these findings and indicates the lack of changes in muscle microvascular oxygenation with l-NAME between sedentary and exercise-trained HFrEF rats. It is interesting to note that the nonobligatory role of NO in training adaptations in HFrEF has also been observed in conduit vessels (80), revealing that considerable improvements in other vasodilatory pathways such as prostaglandins (131) must take place. Compensation by select well-preserved mechanisms of skeletal muscle microvascular oxygenation control in HFrEF [e.g., vascular ATP-sensitive K+ channels (61)] could also protect against exaggerated transient hypoxia during metabolic transitions.

Therapeutic interventions targeting skeletal muscle NO bioavailability: nitrate supplementation.

As mentioned above, inorganic nitrate supplementation is emerging as a potential therapeutic strategy for ameliorating exercise intolerance in chronic diseases, including HF (60, 67). This intervention operates within the nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway and does not rely on the reaction catalyzed by NO synthase or molecular oxygen as a substrate (66). In fact, reduction of nitrite to bioactive NO in vivo via this pathway is facilitated in hypoxic and acidic conditions, which are likely to be found during heavy/severe intensity exercise in the contracting HF skeletal muscle (66). Prominent effects of nitrate supplementation in health include increased local perfusion and oxygenation, enhanced muscle contractility and resistance to fatigue, lowered O2 cost of muscle contractions, and reduced arterial blood pressure (65, 66). These initial reports set the stage for exploring the therapeutic potential of nitrate supplementation in heart failure. To date, nitrate and nitrite interventions have produced consistent improvements in cardiorespiratory function and exercise tolerance in patients with HFpEF (10a, 27, 132, 133) but not in patients with HFrEF (21, 58, 71). The latter is surprising given the encouraging results from the in vitro (22, 77) and animal (34, 42) findings related to HFrEF pathophysiology. Also, in contrast with much of the literature in healthy individuals, mixed results have been reported in other patient populations such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (9, 70, 79, 113), peripheral artery disease (69, 90), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (41, 112). Although the exact bases for these discrepancies have yet to be resolved, certain components of standard cardiovascular pharmacological therapy could blunt responses to nitrate in patients with HFrEF. Chronic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition, for instance, is known to improve NO-mediated vasodilation in HFrEF skeletal muscle (124) and may confound interpretation of human studies. Pertinent to the focus of this review, whether nitrate therapy could augment cardiorespiratory and/or muscle metabolic adaptations to exercise training in HF remains unclear. The ergogenic effects of nitrate supplementation could also extend beyond those on NO bioavailability as described above and allow higher exercise intensities to be performed over the course of a given training program (65). Interestingly, recent investigations on the effect of dietary nitrate via beetroot juice (albeit at a relatively low dose; 6.1 mmol/nitrate, 3/wk) have failed to show any synergism with endurance exercise training in patients with HFpEF (108). Further studies are thus required to establish whether the same holds for the higher nitrate doses proven to be effective for the patients with HFpEF (e.g., 129, 133) and/or patients with HFrEF.

Perspectives

Exercise training promotes a plethora of improvements in physiological, functional, and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure (7, 20, 37). Within the skeletal muscle microcirculation, these adaptations positively impact the O2 transport-utilization system, thereby raising microvascular Po2 across metabolic transients [i.e., slower Po2mv on-kinetics (56)]. This, in turn, facilitates blood-myocyte O2 transfer as described by Fick’s law of diffusion and supports oxidative metabolism and contractile performance (62, 95b). Unfortunately, despite substantial beneficial results, low adherence to exercise training programs remains a major concern in patient clinical care (20, 37). These issues have been documented mainly in HFrEF to date (23) but are likely to be present in the population of patients with HFpEF as well. New and refined strategies are thus warranted to improve further the effectiveness of exercise training in populations of patients with HF. In this context, accumulating evidence indicates that high-intensity interval training not only may evoke greater improvements in V̇o2peak, but also may be associated with higher compliance compared with more traditional, low-intensity endurance exercise training programs (20, 64). Moreover, despite some conflicting results in the clinical setting (21, 58, 71, 110), the potential exists for nitrate supplementation therapy to serve as an exercise training adjunct for patients with HFrEF (21, 71, 83, 92) and HFpEF (10a, 27, 132, 133).

Conclusions

Although the central tenet of HF, a reduction in both cardiac output and O2 transport capacity, characterizes both HFrEF and HFpEF, they present as distinct disease phenotypes. However, far less is known about HFpEF, especially with regard to skeletal muscle function. The exercise intolerance of HFrEF is accompanied by impaired vascular function, capillary rarefaction and the absence of RBC flux in a considerable proportion of capillaries at rest and during contractions, decreased NO bioavailability, reduced microvascular O2 pressures, and elevated muscle deoxygenation, leading to Q̇O2-to-V̇o2 mismatching (57, 95b). Muscle DO2 is reduced, and there is also mitochondrial oxidative impairment with elevated oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction in HFrEF. V̇o2 kinetics become Q̇O2-dependent and slowed in concert with exercise intolerance (Fig. 8). Patients with HFrEF respond to exercise training using both large and small muscle mass paradigms that act to improve muscle perfusive (Q̇O2) and diffusive (DO2) O2 transport, thereby increasing exercise tolerance. Importantly, Esposito and colleagues (Figs. 5 and 6; Refs. 28–30) found that knee-extensor (i.e., small muscle mass) training benefits whole body exercise performance and Rognmo et al. (106) and Wisløff et al. (128) that high-intensity interval training is especially effective for increasing V̇o2peak. The efficacy of these paradigms remains to be tested in HFpEF.

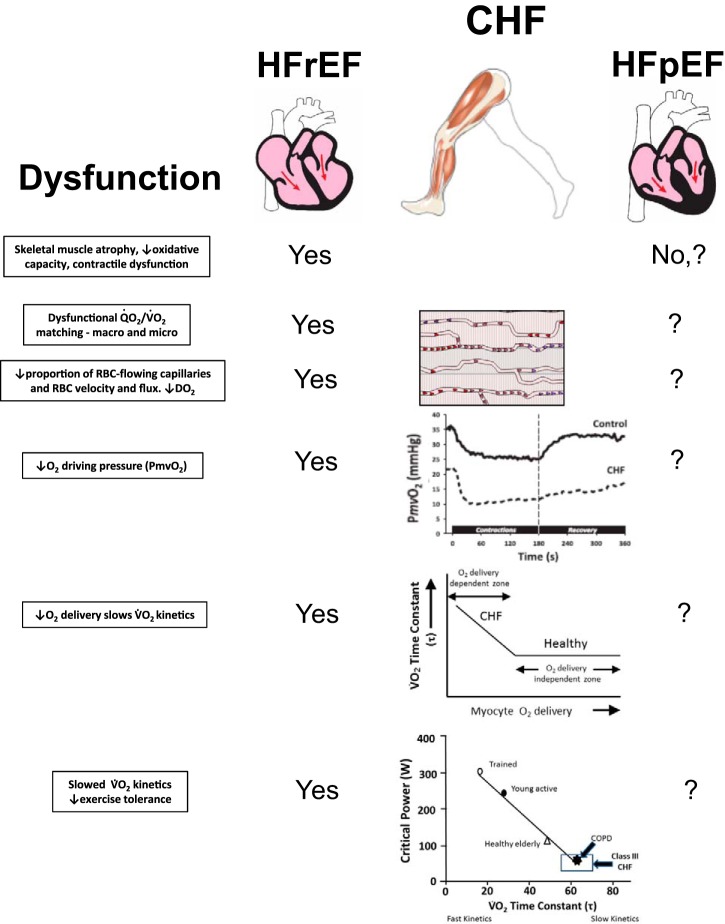

Fig. 8.

Central tenets of impaired muscle Q̇O2 as a primary cause of exercise intolerance in HFrEF and HFpEF. Notably, each cause of dysfunction in HFrEF is amenable to improvement with exercise training or nitrate/nitrite supplementation. In HFpEF, muscle structure and oxidative capacity may be better preserved, but reduced fractional O2 extraction suggests Q̇O2/V̇o2 mismatching and low DO2. Nitrate supplementation in HFpEF enhances vascular function and increases in Q̇O2 raising exercise economy and capacity. As indicated, far less is known regarding muscle microvascular structure and function in HFpEF than HFrEF, making this a fertile area for investigation. Such information will be key to designing more effective therapeutic strategies, which are greatly needed in the burgeoning population of patients with HFpEF. No refers to either absence of these deficits or a lack of evidence, and ? is unknown. CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

When compared with patients with HFrEF, patients with HFpEF appear to retain vascular function (63) and, in rats, muscle oxidative function is better preserved (107). What is surprising is that fractional O2 extraction could be far lower than in their HFrEF counterparts. The mechanistic bases for this response likely involve decreased muscle DO2 (Fig. 9) but remain to be defined. It is notable that the insightful evidence provided by muscle oxygenation (near-infrared spectroscopy, phosphorescence quenching), intravital microscopy of capillary function (animal muscles), magnetic resonance spectroscopy, femoral venous catheterization, and V̇o2 kinetics in HFrEF have yet to be accomplished in HFpEF (Fig. 8). There is some evidence, however, that fractional O2 extraction is improved by exercise training in these patients (50, 52), but the degree to which this is driven by better Q̇O2-to-V̇o2 matching across and within skeletal muscles and improved DO2 of the contracting musculature has not been resolved. Indeed, these are potentially fruitful areas for future research, and the hypothetical scenario for the very low DO2 in HFpEF muscle depicted in Fig. 9 suggests that very large benefits may be derived from therapeutic treatments, either exercise training or pharmacological, that increase DO2. Moreover, muscle oxidative function and exercise capacity in both patients with HFrEF and patients with HFpEF will benefit acutely from an improvement in vascular function that is driven by either enhanced NO bioavailability or cGMP activation (57). Whether such treatments applied chronically can potentiate the effects of training or improve patient participation in cardiac exercise rehabilitation programs are exciting possibilities.

Fig. 9.

A schematic illustration of the perfusive and diffusive components that interact to determine V̇o2max in both HFrEF and HFpEF conditions. Solid lines represent Fick’s law and principle lines for the HFpEF condition and the V̇o2max measured before and after exercise training. The dotted lines represent the untrained sedentary HFrEF condition. Note that, hypothetically, V̇o2max before exercise training is similar between the HFrEF and HFpEF condition but that the HFrEF may have a greater arterial-venous O2 content difference (greater reduction in venous or microvascular Po2) compared with the HFpEF counterpart. This greater arterial-venous O2 content difference would be associated with a larger reduction in perfusive O2 transport (Fick principle) in the HFrEF condition. In contrast, HFpEF may have a larger reduction in diffusive O2 transport (Fick’s law) when compared with the HFrEF condition. Potential effects of exercise training are depicted for the HFpEF condition demonstrating that significant changes in diffusive O2 transport (associated with exercise training-induced changes at the microcirculatory level) may produce significant increases in V̇o2max with potentially little or no changes in perfusive O2 transport.

GRANTS

D. C. Poole is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-50306 and HL-108328 and an Innovative Award from the Terry Johnson Cancer Foundation. R. S. Richardson is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-091830, Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research & Development Service Merit Awards E6910-R, E1697-R, and E2323-I, Veterans Affairs Small Projects in Rehabilitation Research (SPiRE) Award E1433-P, and a Veterans Affairs Senior Research Career Scientist Award E9275-L. M. J. Haykowsky is supported by the Moritz Chair of Geriatric Nursing Research, College of Nursing and Health Innovation at the University of Texas and National Institute of Nursing Research Grant R15-NR-016826. D. M. Hirai is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the College of Human Ecology, Kansas State University (Manhattan, KS). T. I. Musch's research is supported by a SMILE Award from the College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University (Manhattan, KS).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.C.P., R.S.R., M.J.H., D.M.H., and T.I.M. prepared figures; D.C.P., R.S.R., M.J.H., D.M.H., and T.I.M. drafted manuscript; D.C.P., R.S.R., M.J.H., D.M.H., and T.I.M. edited and revised manuscript; D.C.P., R.S.R., M.J.H., D.M.H., and T.I.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abudiab MM, Redfield MM, Melenovsky V, Olson TP, Kass DA, Johnson BD, Borlaug BA. Cardiac output response to exercise in relation to metabolic demand in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 15: 776–785, 2013. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams V, Alves M, Fischer T, Rolim N, Werner S, Schütt N, Bowen TS, Linke A, Schuler G, Wisloff U. High-intensity interval training attenuates endothelial dysfunction in a Dahl salt-sensitive rat model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Appl Physiol (1985) 119: 745–752, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01123.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnoletti L, Curello S, Bachetti T, Malacarne F, Gaia G, Comini L, Volterrani M, Bonetti P, Parrinello G, Cadei M, Grigolato PG, Ferrari R. Serum from patients with severe heart failure downregulates eNOS and is proapoptotic: role of tumor necrosis factor-α. Circulation 100: 1983–1991, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.19.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen P, Adams RP, Sjøgaard G, Thorboe A, Saltin B. Dynamic knee extension as model for study of isolated exercising muscle in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 59: 1647–1653, 1985. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.5.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett-O’Keefe Z, Lee JF, Berbert A, Witman MA, Nativi-Nicolau J, Stehlik J, Richardson RS, Wray DW. Hemodynamic responses to small muscle mass exercise in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1512–H1520, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00527.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behnke BJ, McDonough P, Padilla DJ, Musch TI, Poole DC. Oxygen exchange profile in rat muscles of contrasting fibre types. J Physiol 549: 597–605, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belardinelli R, Georgiou D, Cianci G, Purcaro A. 10-Year exercise training in chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 1521–1528, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics–2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 135: e146–e603, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry MJ, Justus NW, Hauser JI, Case AH, Helms CC, Basu S, Rogers Z, Lewis MT, Miller GD. Dietary nitrate supplementation improves exercise performance and decreases blood pressure in COPD patients. Nitric Oxide 48: 22–30, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhella PS, Prasad A, Heinicke K, Hastings JL, Arbab-Zadeh A, Adams-Huet B, Pacini EL, Shibata S, Palmer MD, Newcomer BR, Levine BD. Abnormal haemodynamic response to exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 13: 1296–1304, 2011. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Borlaug BA, Koepp KE, Melenovsky V. Sodium nitrite improves exercise hemodynamics and ventricular performance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 66: 1672–1682, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Russell SD, Kessler K, Pacak K, Becker LC, Kass DA. Impaired chronotropic and vasodilator reserves limit exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 114: 2138–2147, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, Redfield MM. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 56: 845–854, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowen TS, Cannon DT, Murgatroyd SR, Birch KM, Witte KK, Rossiter HB. The intramuscular contribution to the slow oxygen uptake kinetics during exercise in chronic heart failure is related to the severity of the condition. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 378–387, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00779.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardús J, Marrades RM, Roca J, Barberà JA, Diaz O, Masclans JR, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Wagner PD. Effects of on leg V̇o2 during cycle ergometry in sedentary subjects. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30: 697–703, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamberlain AM, St Sauver JL, Gerber Y, Manemann SM, Boyd CM, Dunlay SM, Rocca WA, Finney Rutten LJ, Jiang R, Weston SA, Roger VL. Multimorbidity in heart failure: a community perspective. Am J Med 128: 38–45, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clanton TL, Hogan MC, Gladden LB. Regulation of cellular gas exchange, oxygen sensing, and metabolic control. Compr Physiol 3: 1135–1190, 2013. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coats AJ, Adamopoulos S, Meyer TE, Conway J, Sleight P. Effects of physical training in chronic heart failure. Lancet 335: 63–66, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90536-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coats AJ, Adamopoulos S, Radaelli A, McCance A, Meyer TE, Bernardi L, Solda PL, Davey P, Ormerod O, Forfar C, Conway J, Sleight P. Controlled trial of physical training in chronic heart failure. Exercise performance, hemodynamics, ventilation, and autonomic function. Circulation 85: 2119–2131, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.85.6.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coats AJ, Forman DE, Haykowsky M, Kitzman DW, McNeil A, Campbell TS, Arena R. Physical function and exercise training in older patients with heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 14: 550–559, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coggan AR, Leibowitz JL, Spearie CA, Kadkhodayan A, Thomas DP, Ramamurthy S, Mahmood K, Park S, Waller S, Farmer M, Peterson LR. Acute dietary nitrate intake improves muscle contractile function in patients with heart failure: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Circ Heart Fail 8: 914–920, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, Yang BK, Waclawiw MA, Zalos G, Xu X, Huang KT, Shields H, Kim-Shapiro DB, Schechter AN, Cannon RO 3rd, Gladwin MT. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med 9: 1498–1505, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deka P, Pozehl B, Williams MA, Yates B. Adherence to recommended exercise guidelines in patients with heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 22: 41–53, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10741-016-9584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhakal BP, Malhotra R, Murphy RM, Pappagianopoulos PP, Baggish AL, Weiner RB, Houstis NE, Eisman AS, Hough SS, Lewis GD. Mechanisms of exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the role of abnormal peripheral oxygen extraction. Circ Heart Fail 8: 286–294, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diederich ER, Behnke BJ, McDonough P, Kindig CA, Barstow TJ, Poole DC, Musch TI. Dynamics of microvascular oxygen partial pressure in contracting skeletal muscle of rats with chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 56: 479–486, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00545-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drexler H, Riede U, Münzel T, König H, Funke E, Just H. Alterations of skeletal muscle in chronic heart failure. Circulation 85: 1751–1759, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.85.5.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggebeen J, Kim-Shapiro DB, Haykowsky M, Morgan TM, Basu S, Brubaker P, Rejeski J, Kitzman DW. One week of daily dosing with beetroot juice improves submaximal endurance and blood pressure in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 4: 428–437, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esposito F, Mathieu-Costello O, Shabetai R, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Limited maximal exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: partitioning the contributors. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 1945–1954, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esposito F, Reese V, Shabetai R, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Isolated quadriceps training increases maximal exercise capacity in chronic heart failure: the role of skeletal muscle convective and diffusive oxygen transport. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 1353–1362, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esposito F, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Incremental large and small muscle mass exercise in patients with heart failure: evidence of preserved peripheral haemodynamics and metabolism. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 213: 688–699, 2015. doi: 10.1111/apha.12423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Federspiel WJ, Popel AS. A theoretical analysis of the effect of the particulate nature of blood on oxygen release in capillaries. Microvasc Res 32: 164–189, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(86)90052-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferguson SK, Hirai DM, Copp SW, Holdsworth CT, Allen JD, Jones AM, Musch TI, Poole DC. Effects of nitrate supplementation via beetroot juice on contracting rat skeletal muscle microvascular oxygen pressure dynamics. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 187: 250–255, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson SK, Hirai DM, Copp SW, Holdsworth CT, Allen JD, Jones AM, Musch TI, Poole DC. Impact of dietary nitrate supplementation via beetroot juice on exercising muscle vascular control in rats. J Physiol 591: 547–557, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.243121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferguson SK, Holdsworth CT, Colburn TD, Wright JL, Craig JC, Fees A, Jones AM, Allen JD, Musch TI, Poole DC. Dietary nitrate supplementation: impact on skeletal muscle vascular control in exercising rats with chronic heart failure. J Appl Physiol (1985) 121: 661–669, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00014.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferguson SK, Holdsworth CT, Wright JL, Fees AJ, Allen JD, Jones AM, Musch TI, Poole DC. Microvascular oxygen pressures in muscles comprised of different fiber types: impact of dietary nitrate supplementation. Nitric Oxide 48: 38–43, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.09.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferreira LF, Hageman KS, Hahn SA, Williams J, Padilla DJ, Poole DC, Musch TI. Muscle microvascular oxygenation in chronic heart failure: role of nitric oxide availability. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 188: 3–13, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]