Abstract

Objectives

To review association of the obesity pandemic with appearance of cancers in young adults under age 50, and to define potential mechanisms by which obesity may accelerate development of malignancy.

Methods

A comprehensive narrative review was performed to integrate preclinical, clinical and epidemiologic evidence describing the association of obesity with cancer in young adults based on a search of PubMed and Google databases.

Results

Results from over 100 publications are summarized. Although they differ in age groups analyzed and incidence of obesity, sufficient data exists to suggest an influence of the obesity pandemic on the increase of cancer among young adults.

Conclusion

Cancer in young adults, is occurring with increasing frequency. Overweight and obesity has become a major public health issue reaching pandemic proportions. Excess weight is associated with increased cancer risk, morbidity and mortality. Multiple murine models indicate that obesity not only increases cancer incidence, but also accelerates its development. Thus, the possibility exists that overweight and obesity may be contributing to appearance of specific malignancies at younger ages. This prospect, in association with the worldwide expansion of obesity, suggests an impending explosive increase in obesity associated cancers in young adults.

Keywords: Obesity, Cancer, Young Adults

Introduction

Cancer in young adults is being reported with increasing frequency and has become a matter of urgent concern (1). At the same time, overweight and obesity has become a major public health issue, both in children and adults, reaching pandemic proportions on a worldwide basis (2, 3). While it has been clearly documented that excess weight is associated with both increased risk of occurrence and increased morbidity and mortality for multiple malignancies (4–6), there has been relatively little focus on impact of overweight and obesity on shifts in timing of cancer appearance to individuals of younger age. However, recent CDC data indicate an increase in overweight and obesity associated cancers in 20 to 49 year old individuals (Supplement 1). Importantly, multiple murine models indicate that obesity and obesogenic diets, not only increase the incidence of malignancy, but also accelerate its development and shift its occurrence to earlier ages. (5, 7–17).

Thus, the possibility needs to be considered that overweight and obesity may be contributing significantly to the clinical appearance of some malignancies at younger ages. This prospect, in association with the continued worldwide expansion of obesity (2, 3), suggests an impending explosive increase in obesity associated cancers in young adults. Anticipation of the potential dire consequences of this evolution, compel careful epidemiologic monitoring, more research on mechanisms by which obesity promotes and accelerates cancer, especially in young adults, development of focused strategies for prevention, and potentially new approaches to screening and care.

The goals of this article are 1) to enhance awareness of the obesity cancer linkage; 2) to illustrate how both obesity and obesogenic diets may shift appearance of obesity promoted cancers to younger age groups, especially into the 20 to 50 year old age group; 3) to examine preclinical murine models and potential mechanisms by which obesity and obesogenic diets accelerate the appearance of malignancy; 4) to review the epidemiologic and clinical evidence indicating where this may already be happening; 5) to identify which obesity associated cancers are most likely to pose this threat; and 6) to consider approaches to better document and avert the crisis.

Obesity Cancer Linkage

Although adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancers have been operationally defined as those occurring in the 15 to 39 year old age group (18), this article is focused on malignancies, most commonly associated with patients over age 50, that have recently been reported with increasing frequency in the younger than 50 year old age group. Moreover, since this article examines the impact of obesity on cancers in young adults, it will concentrate on the 13 cancers listed in Table 1, which based on epidemiologic review by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), have been identified as having sufficient evidence to be linked to excess body fat (6). It will not include discussion of tumors such as sarcoma, acute leukemia and others that may occur in young adults but have not been clearly linked to obesity. It also will not consider malignancies such as hematologic malignancies, prostate cancer and others, where evidence for an association with obesity has not reached the level of significance as those recently reported (6). In this article, we use the following categories of Body Mass Index (BMI) (weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters), normal weight as BMI of 18.5 to 24.9, overweight as BMI of 25.0 to 29.9, obesity BMI of 30 or more; and severe or morbid obesity as BMI ≥40 (6).

Table 1.

Relation Obesity Associated Cancers to Young Adult Malignancies and Murine Models

| Obesity Associated Cancer* (6) | U.S. Incidence × 10−3≠ (19) | Population Attributable Fraction % (21) |

Peak Age Incidence Years∞ (20) | Usual Age Range Years≈ (20) All years where Incidence > 15% |

Percent New Cases in 20–44 Year Age Group◆ (20) |

Murine Models DIO & HFD Promoted Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/F | ||||||

| Breast | 253 | −/14 | 62 | 55–84 | 10.5 | MMTV-TGFα (7) |

| Colon & Rectal | 135 | 32/17 | 67 | 45–84 | 5.8 | APCMin (8) |

| Kidney | 63 | 25/34 | 64 | 55–74 | 7.8 | |

| Endometrial | 61.3 | −/48 | 62 | 45–74 | 7.3 | Pten+/−(16) |

| Thyroid | 57 | 32/5 | 51 | 20–64 | 23.9 | ThrbPV/PV Pten+/− (13) |

| Pancreas | 54 | 14/11 | 70 | 55–84 | 2.4 | KrasG120 Conditional (9, 10) |

| Liver | 41 | NA | 63 | 55–84 | 2.5 | C57BL/6J (11) MUP-UPA (12) |

| Myeloma | 30 | NA | 69 | 55–84 | 3.5 | KwLwRij (14) |

| Gastric Card | 28 | NA | 68 | 55–84 | 6.2 | |

| Meningioma▪ | 27 | NA | 58 | 45–74▪ | 16.8 | |

| Ovary | 22 | −/7 | 63 | 45–84 | 10.6 | KpB (15) |

| Esoph AC | 17 | 44/48 | 67 | 55–84 | 2.3 | L2-1L-1B (17) |

| Gall Bladder | 7 | −/53 | 85+◦ | 65–90◦ | NA |

Obesity associated cancers identified by 2016 IARC analysis (6).

U.S. incidence of specific cancers from American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2017 (19).

Peak age incidence from SEER Cancer Statistics 1975–2014 (20).

Usual age range years from SEER Cancer Statistics (20) combining all decades with incidence ≥ 15% for each malignancy.

Percent New U.S. Cases in 20–54 Year Age Group from SEER Cancer Statistics (20) combining 20–34, 35–44 & 45–54 Year Old Age Groups.

Boxes indicate malignancies among top 20 invasive cancers in U.S. 20–39 Years Old (18).

Boxes indicate malignancies among top 20 invasive cancers in U.S. 20–39 Years Old (18).

Age range for Meningioma provided for all primary brain tumors (19).

Gall bladder age incidence and range from U.K. Data, 2015 (92).

Table 1, column 1, lists the 13 tumors recently reported by the IARC where there is sufficient evidence to identify an association between obesity and specific malignancies (6). Listed in column 2, these malignancies are arranged in order of annual incidence of US new cases (19, 20). Column 3 lists the US population attributable fraction (PAF) as the percentage of each malignancy attributed to obesity for both males and females (21). These data demonstrate an important contribution of obesity to cancers of colon and rectum, thyroid, esophagus and kidney in men, and to kidney, endometrium, esophagus and gall bladder cancers in women. With 253,000 new cases of breast cancer in the United States, a 14% PAF calculates to 35,420 new cases per year attributable to obesity. For colorectal cancer (CRC), adjusting for male/female distribution and PAF, indicates 22,655 new cases CRC in men and 10,812 new cases in women attributable to obesity. Applying similar calculations to the incidence and PAF data provided in Table 1, indicates that in 2017, more than 144,000 of those cancers occurring in the U.S. were attributable to obesity. However, this number probably is an underestimate since PAF’s are not available for several of the obesity associated malignancies such as liver, myeloma, gastric cardia or meningioma.

The 4th and 5th columns indicate the peak and usual age range incidence for each of these tumors. The median age of all cancers diagnosed in the U.S. is 66 years old. While most are diagnosed in patients older than 50 (20), appearance of thyroid, ovarian, endometrial and CRC cancers and meningiomas are not uncommon in patients younger than 50 (20). Strikingly, as shown in 6th column, of the 13 IARC obesity associated malignancies, at least 9 (shown in blue) have been reported as occurring in young adults, and are in the top 20 AYA cancers (18). The last column indicates murine model systems where nine of the malignancies have been shown to be accelerated and become more aggressive in association with obesity (7–17).

Obesity Accelerates Cancer Development

From a mechanistic viewpoint, overweight/obesity are generally considered to be promoters of cancer progression (5). Thus overweight/obesity promote cancer by multiple concurrent mechanisms including ; 1) stimulation of low grade inflammation and oxidative stress with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF, and increased Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), the latter may also contribute to mutagenesis; 2) alteration of growth promoting factor levels, especially insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), which increases in association with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance; 3) altered sex steroid hormones with increased conversion of androgens to estrogens resulting from increased adipose tissue production of aromatase, the enzyme responsible for this conversion; 4) altered adipocytokine proteins including increased growth promoting and pro-inflammatory components such as leptin, retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), resistin, visfatin and reduced growth controlling adipokines such as adiponectin; 5) alterations in intestinal microbiome with expansion of tumor promoting species such as Fusobacteria ; and 6) mechanical effects of obesity such as those leading to hiatal hernia, gastro esophageal reflux disease predisposing to Esophogeal Adeno Carcinoma (5).

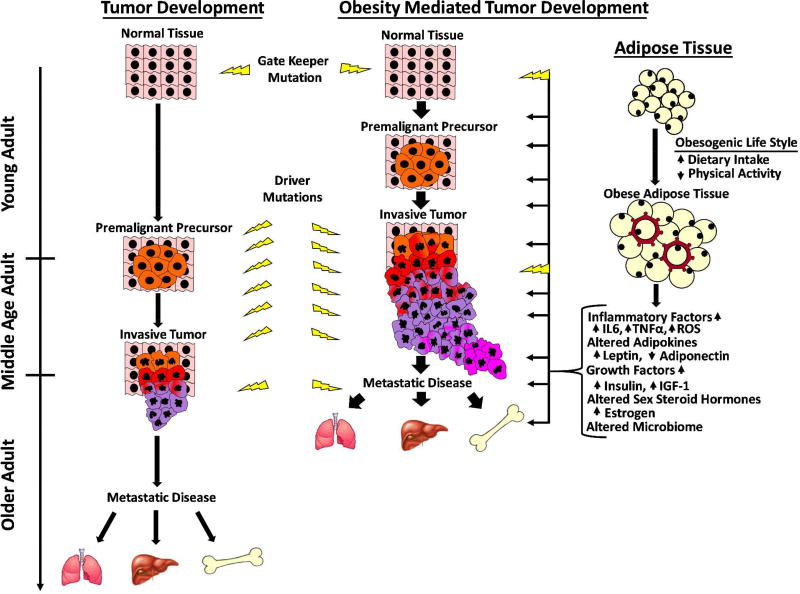

Figure 1 provides a conceptual model, supported by multiple murine studies, of how obesity impacts cancer by accelerating its development. (7–17). As postulated for development of colon cancer, and now widely accepted for multiple malignancies, sporadic tumors are initiated with mutation in a gate keeper gene (13, 22, 23), sometimes similar to those mutations causing hereditary cancer syndromes. Mutated cells then progress through a multistage process in which multiple genetic changes ultimately lead to development of a benign premalignant, then malignant neoplasm with invasive and subsequently metastatic properties. For CRC, transformation from normal epithelium to benign adenoma, ultimately leading to frank cancer and metastatic disease is projected to require at least seven independent genetic events and possibly mutation in as many as 15 driver genes (24) as well as multiple epigenetic alterations (25). In some cases, this process may require long latent periods extending to multiple decades to progress from normal epithelium to frank cancer.

Figure 1.

Timeline Obesity Promoted Acceleration of Cancer Progression

The rate of progression to invasive cancer is determined by multiple factors including mutation and proliferation rates which are respectively affected by DNA damage response - DNA repair systems and a host of growth factors. It may vary among different tumors and even among different transformed clones in the same individual. Thus obesity may enhance mutation rates by generation of increased ROS. Importantly, however, high fat diets (HFD) and diet induced obesity (DIO) have been shown to accelerate tumor growth rates in association with production of increased growth factors, such as Insulin, IGF-1, Leptin, RBP4 and others (8, 26, 27). As shown in Figure 1, development of obesity, usually due to combination of HFD and decreased physical activity, results in expanded fat mass, characterized by increased number and size of adipocytes, some of which undergo necrosis and become surrounded by macrophages to form crown-like structures with a propensity for releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, and TNFα (28). In addition, expanded and inflamed adipose tissues may provide increased levels of multiple growth promoting cytokines, adipokines and hormones, many of which accelerate the multistage transition from normal tissue to invasive and metastatic cancer. This process not only accounts for the accelerated development of tumors in the presence of adipose tissue excess, it also explains why patients with obesity driven cancers may present with more advanced tumors at earlier ages. Thus, the long latent period required for initial presentation of many tumors provides the basis for obesity to impact the process and, in fact, accelerate both the appearance and extent of clinical disease. Accordingly, it is expected that initial mutations for sporadic cancer will occur with similar frequency and at similar ages in both normal patients and those with obesity. In addition, it is possible that obesity associated inflammation and ROS may further contribute to mutagenesis and cancer initiation. Nonetheless, the metabolic and growth promoting consequences of concurrent or prior obesity can provide the stimulus for accelerated development of cancer and associated comorbidities including death.

Systems Demonstrating Obesity Promotes & Accelerates Development of Malignancies

The shortening of the latent period from benign to malignant disease in association with obesity has been most clearly demonstrated at the clinical level where disease associated monoclonal immunoglobulin provides a biomarker for early detection and demonstration that obesity accelerates conversion of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Unknown Significance, (MGUS) to Multiple Myeloma (MM) (29). In further support of this proposal, that obesity does not initiate, but rather promotes cancer progression, is the demonstration that almost all murine models in which obesogenic diets and DIO promote tumors, requires experimental utilization of genetically modified animals, containing cancer predisposing genes, or transplantation of pre-existing tumor cell lines (5, 7–17).

It is noteworthy that in some murine models, HFD has been shown to promote CRC and breast cancer in mice that are resistant to DIO (7, 8, 30). These studies indicate that pro-inflammatory and growth promoting effects of HFD, even in the absence of DIO, may accelerate tumor progression. Other murine systems show that even after HFD induced DIO and subsequent weight loss, the tumor promoting effects of obesity may endure for varying time periods, thereby providing a model for promotion of adult tumors by childhood, adolescent and young adult obesity (7, 8, 30)

The contribution of pro-inflammatory and growth promoting factors as mediators in the HFD and DIO accelerated malignancies is further illustrated by the demonstration that tumor promoting effects of obesity can be abrogated by molecular or pharmacologic interference with pro-inflammatory and growth promoting pathways such as pharmacologic inhibition of receptors for insulin or IGF-1 (31), molecular interference with leptin receptor (32), and genetic and pharmacologic interference with pro-inflammatory activity of complement system (8). It is further noteworthy that not all HFD are equal in promoting malignancy as shown by olive oil, an important component of the Mediterranean diet, protecting against HFD acceleration of gastrointestinal neoplasia in APCMin mice (8).

Clinical & Epidemiologic Evidence Indicating Obesity Shifts Malignancies To Younger Ages

From a clinical and epidemiological viewpoint, we focus initially on colorectal cancer which has become one of the major adult tumors generating alarm for its increasing appearance in young adults (33). CRC, usually occurring between ages 45–84 with peak incidence at 67 years old (20), and uncommonly seen in young adults, is now being increasingly identified in both men and women, below age 50 (20) (34–39), with greater increase noted for left-sided sigmoid and rectosigmoid CRC then right-sided CRC (35).

Analysis of SEER Population and multiple Hospital Based Cancer Registries, covering periods from 1973 to 2017, indicate that CRC incidence has remained stable and/or decreased in people over 50 by as much as 3% per year. In contrast, CRC has shown an average 1.5% increase per year among 20–40 year old men and women (40, 41). Moreover, younger patients were noted to present with more advanced, higher stage, more poorly differentiated disease and those presenting with stage IV CRC showed inferior survival.

The overall decrease in incidence of colorectal cancer has been attributed to expanded screening programs and removal of early premalignant adenomas. Because of the much higher incidence of CRC in older individuals, these programs have been primarily targeted at patients over 50. Thus, increase in incidence and more advanced stage at presentation among young adults has been attributed, in part, to lack of screening and to tumor promotion by lifestyle factors including obesity, consumption of red and processed meat, and possibly alcohol and tobacco use (35, 42).

Many of the above reports point to a concurrent increase of obesity and CRC in the young. Some document increased obesity and cancer in the same population, however few provide obesity demographics in the CRC patients (38). And, although not specific for young adults, some series indicate an association of obesity with increased risk of sigmoid and rectosigmoid cancers (43).

In an important study of over 1.1 million Israeli, Jewish men with 19.5 million person years follow up, overweight and obesity in adolescents aged 16–19, was associated with a substantially increased risk for colon cancer (HR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.17 – 2.0) but not for rectal cancer in adult years. The median age for patients with newly diagnosed colon cancer was 43.3 ±8.7 years, thereby supporting an association of adolescent detected obesity with young adult colon cancer (37) and suggesting effects of obesity over a long latent period of cancer development.

In addition to its association with increased risk for CRC, obesity is also associated with a twofold increase in risk for colorectal adenoma (CRA), a premalignant precursor to CRC (44). CRAs, are commonly reported in patients younger than age 55 (45) and are noted to be more advanced in patients with obesity (46). In a study of people examined across the age range from 30 to greater than 70 years, high BMI was identified as a risk factor for CRA in 30–39 year old men and 40–49 year old women (36). Thus, subjects with overweight or obesity are at increased risk for developing CRC and its precursor, CRA, during young adulthood. Moreover, obesity has been shown to precede the diagnosis of CRA and CRC by long latent periods (47).

In summary, the clinical development of CRA and CRC fit well with the model provided in Figure 1, including increased and early development of obesity associated benign adenoma preceeding cancer with a long latent period providing time for impact of obesity stimulated growth factors to accelerate tumor development. Moreover, in addition to decreased screening in young adults, obesity promoted progression may help explain why CRC in the young is more advanced at time of presentation (33).

While this discussion has focused on sporadic colorectal neoplasia and its increasing appearance in young adults, additional insight is provided by patients with known inherited predispositions to CRC including Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) or Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colon Cancer (HNPCC), bearing respectively, mutations in the gatekeeper genes, Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC), or mismatch repair (MMR) genes, MLH1, MSH2, MSG6, PMS2, EPCAM (48). These patients commonly develop CRA or CRC at younger ages, where CRC risk has been shown to be increased in association with excess weight (49, 50). In a study of 937 HNPCC carriers, followed at 14 institutions, with median age enrollment 44.9 years (36–53 years), obesity was associated with a 2.4-fold greater risk for CRC compared to normal and underweight reference groups. Interestingly, there was no increase in risk in HNPCC patients with obesity randomly assigned to aspirin, 600 mg daily, suggesting that obesity promoted CRC in HNPCC patients may be reduced by regular aspirin use (51).

Female breast cancer is the most common US malignancy included on the IARC-obesity associated cancer list, with peak incidence at 62 years and usual age range 55–84 (20). Breast cancer in post-menopausal women is usually estrogen receptor positive and is associated with increased risk in association with obesity (4). Of the tumors listed in Table 1, breast cancer is unique in that a major variety, premenopausal breast cancer, characterized by estrogen receptor negative status, has been noted to occur at a relatively constant rate of 40% by age 40 (52) and obesity is associated with an overall decreased risk of premenopausal breast cancer (53). Thus, because of the already significant occurrence of premenopausal breast cancer in patients under 40 it is difficult to determine an obesity shift to younger age. However, premenopausal women at high risk for breast cancer, including prior history of lobular carcinoma in situ, generally considered a multifocal premalignant precursor, show significantly increased risk of developing breast cancer in association with obesity (54). These high risk premenopausal women fit well into the latent process depicted in Figure 1 that is accelerated by obesity. Moreover, unique insight is provided by patients with Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), tumors that lack expression of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (55). These tumors, commonly identified in premenopausal women, are refractory to hormonal and cytotoxic chemotherapy (55). In a retrospective review of invasive breast cancer among 1064 patients from Walter Reed Hospital, 160 patients had TNBC of which 89 were below age 50 and 148 were overweight or obese. Thus, TNBC in all patients, including those younger than age 50 is highly associated with obesity (56).

Further insight is provided by patients with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) where 80% cases are attributed to mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2 (57). In a series of 176 multigenerational kindreds, earlier appearance of breast cancer was noted in successive generations with age at diagnosis shifting from 51.8 years old in grandparents, to 48.7 years old in parents, followed by 41.9 years in probands and 34.7 in children (58). The shift to earlier age in successive generations was attributed to life style factors including obesity. In other studies, weight gain and number of pregnancies were shown to significantly increase risk of breast cancer whereas weight loss between age 18 and 30 years was associated with decreased risk of breast cancer (59).

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), peak incidence age 60–74 years, is a noninvasive breast cancer precursor, unusual before age 35. DCIS has recently undergone a marked increase in detection and occurrence from an incidence of 1.8 per 100,000 in 1973-75 to 32.5 in 2004. The increase has mainly occurred in patients older than 50, however DCIS has been noted to be increased in all age groups in association with obesity (60). Thus the breast cancer precursor DCIS, familial breast cancer associated with BRCA mutation and TNBC are all increasing in incidence in young adults and the increases are associated with obesity (54–60).

Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), the third most common IARC obesity associated malignancy (6), has a peak incidence for diagnosis at age 64 (20), however, several retrospective series reported RCC patients younger than 45 (61). Although up to 60% of patients with RCC are reported as overweight/obese (62), the specific percentage of patients under 45 with excess weight has not been reported. However, in a case control study of 1,214 patients and 1,234 controls, early adult obesity was associated with a 60% increase in risk for RCC (63).

Endometrial Cancer in the US is the most common malignancy of the female genital tract. It is most frequently diagnosed in postmenopausal women, aged 45–74 years (19, 20). However, 2–14% of endometrial cancers are reported to occur in women 40 years and younger (64). Sporadic endometrial cancers in the young are usually associated with high BMI and with obesity rates reported to range from 37–60% (64). Many of these patients have polycystic ovary syndrome characterized by obesity, menstrual irregularity, infertility and enlarged ovaries with multiple ovarian cysts (64).

Thyroid cancer commonly occurs in young adults with 28% of new diagnoses in the 20–40 year old age group. Its incidence in patients under 65 is increasing (65), extending down to the 45–49 year old age group in some South American countries (66). In contrast to many tumors discussed in this series, thyroid cancer in young adults is usually curable since it most frequently is detected early as an asymptomatic neck mass. Cases in young adults show a female preponderance, appear to be differentiated, with papillary histology being more frequent than follicular, and frequently harbor a mutation in the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK, Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathway (65).

Pancreatic cancer with peak incidence in 70–80 year olds is uncommonly observed below age 45 and is increasing in frequency (19, 20). Individuals who had overweight or obesity between ages 20 to 39 years had 2–6 years earlier onset of pancreatic cancer compared to normal weight controls (67). A recent UK survey conducted between 1998 to 2006 showed no change in incidence rate for males under 50 years, however, a slight increased incidence was reported in females in the 20–39 year old group (68). In a retrospective review covering 1993 to 2008, 33 patients (5.7%) were identified in the 50 year or younger age range. Only 3 (9%) had obesity compared to 4 (12%) of matched controls (69).

Hepatocellular Cancer (HCC), with overall incidence in Western countries peaking in 60–70 year olds, is one of the most common cancers on a worldwide basis (70). Incidence rates in the US have increased by 2.5 – 3 fold over the past 35 years (71). On a global basis, HCC is associated with liver injury from different etiologies including viral infections with Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C; hepatotoxins including aflatoxin, chronic alcohol abuse, and metabolic alterations that occur with obesity, the latter leading to metabolic syndrome, consisting of obesity, diabetes, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia (72). The common pathway by which each of these insults leads to HCC includes liver damage, followed by inflammation, usually leading to cirrhosis then HCC, thereby providing an extended latent period for obesity promoted carcinogenesis.

Obesity mediated liver damage progresses through Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) showing steatosis, lipid deposition in liver cells, without inflammation, proceeding to Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis (NASH) characterized by further fatty acid deposition, ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes with inflammation, leading to fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC (72). In Western countries, where overweight/obesity are common, NAFLD is present in 20–40% of the general population (72). The increase in obesity and its comorbidities including diabetes and metabolic syndrome in Western countries, is projected to promote the incidence of HCC, especially in Hispanic men and African American women (73).

Since NAFLD is a predisposing risk factor for HCC, it is noteworthy that NAFLD is increasing in young adults in association with the increased incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome (74). Thus NAFLD in young adults, 18–30 year olds, has increased 2.5 fold over the past 3 decades and is reported to be present in more than half (57.4%) of young adults with morbid obesity (74).

In a recent US study, the Liver Cancer Pooling Project, composed of 14 separate cohorts, containing 2,087 cases, with prospectively measured BMI and waist circumference, showed that excess weight at time of enrollment was associated with liver cancer in a dose response manner (71). Although most of the cohorts enrolled “older” Americans, 85 were younger than 50 at time of enrollment and 18 of these were diagnosed with liver cancer before age 50, three of whom had obesity at time of enrollment (Campbell, P & Newton, C. – Personal Communication). This observation, that 18 of 85 patients developed liver cancer before age 50 and the high incidence of NAFLD in young adults with obesity indicates the importance of careful surveillance of HCC as another malignancy likely to increase in young adults.

Multiple Myeloma (MM), characterized by malignant proliferation of plasma cells, anemia, elevated levels of a circulating monoclonal immunoglobulin, destructive bone lesions and renal failure is the second most common hematologic malignancy in the US and the only primary malignancy of blood cells included by the IARC as related to obesity (6). MM is diagnosed with a peak incidence of approximately 69 years, and has maintained a constant incidence for at least the past 3 decades (75). However, in 3 series reported since 1992, MM has been reported in patients younger than 45 with an incidence of 2.2, 9.6 and 15% (76, 77). None of these series reported BMI. In a pooled analysis of 242 MM cases in patients younger than 50 compared to 1758 age matched controls, patients showed a significant positive association of elevated BMI with risk of MM and a greater than two fold increase in MM risk for patients with severe obesity (78). Moreover, the incidence of MM has been noted to be increased in patients who reported heavy compared to lean body shapes during childhood and adolescence (75) providing support for a potentially long latent period for the impact of obesity on malignancy development Interestingly, chromosomal abnormalities characteristic of MM have been rated to be no different in patients above or below age 45 (79).

Monoclonal Gammopathy of Unknown Significance (MGUS), characterized by restricted proliferation of a predominant clone of plasma cells, not exceeding 10% of marrow cells and absence of diagnostic criteria for MM (80), is considered a universal premalignant precursor of MM with variable rates of progression (81). MGUS, identified in large population screenings by detection of circulating monoclonal immunoglobulins, is most common in the 80–96 year age group, however, it has significantly been reported in patients younger than age 50, where in some cases it is projected to have been present for latent periods in excess of 20 years (82). Obesity has been shown to be associated with increased risk for MGUS in women (83). Interestingly, although it is considered a premalignant condition, MGUS shares many of the genetic and cytogenetic changes noted in MM including activation of c-myc, del(17p), t(4:14) and 1q gains (81). In a retrospective study of 7878 MGUS patients identified through the US Veterans Health Administration database, 39.8% were overweight and 33% were obese. Moreover, risk of transformation of MGUS to MM was increased with obesity and black race (29, 83).

Esophageal Adeno Carcinoma (EAC) and Gastric Cardia Adenocarcinoma (GCAC), both malignancies of glandular epithelium originating near the gastroesophageal junction, have undergone a rapid increase in incidence over the past 2–3 decades (84, 85). They are consistently associated with overweight/obesity and 10% of patients presenting with EAC are noted to have morbid obesity (86). Although EAC has a peak incidence in the 80 year old age group (87), in a retrospective study of 374 patients treated for EAC between 2000 to 2007, 63 or 16.8% were under age 50 (86). EAC may be preceded by a premalignant precursor, Barrett’s Esophagus, commonly seen in younger patients, where it is associated with chronic inflammation, gastro esophageal reflux disease and obesity (87).

In addition to their association with obesity at time of diagnosis, occurrence of both EAC and GCAC in later years is increased following elevated BMI during early adulthood (age 20) and with progressive weight gain between ages 30 and 50 (73). In addition to the overall increase in occurrence of BE in young adults (87) there has been a notable increase in EAC in patients under age 40 and more than 10% of patients undergoing surgery for EAC are reported to be ≤ 50 years old (88).

Meningioma constitutes 20–30% of all intracranial neoplasms with peak incidence in men in the 60–69 year age group and in the 70–79 year age group in women (89, 90). Cranial irradiation and obesity are risk factors, (89) sometimes with long latent periods of more than 20 years between radiation and diagnosis of meningioma. Meningioma in the pediatric age group is seen as part of hereditary syndromes such as Neurofibromatosis with inherited, NF2 mutations. Somatic mutations of NF2 gene are frequently identified in sporadic cases of meningioma (90). In a report of 35 patients from a single institution and meta-analysis of over 450 patients, meningioma occurring during first 3 decades of life, with an average age at diagnosis of 25 years, had a female predominance but no notation of occurrence of obesity (90).

In contrast to many of the other cancers discussed in this article, Epithelial Ovarian Cancers (EOC), are not uncommon among young women where they are thought to coincide with activity of the female reproductive cycle (19, 20). Increased BMI is a risk factor for EOC and elevated levels of IGF-1, which frequently accompany obesity, are thought to contribute (91). Mutation of Mismatch Repair Genes (MMR) including germ line mutations occur in a small percentage of patients under 40.

Gall bladder cancer, a rare malignancy in the US, with peak incidence in the 80 year old group, is rarely seen or reported in patients under 50 (92). Risk factors for Gall Bladder cancer include obesity and chronic inflammation associated with gall stone disease. Chronic inflammation of 15 or more years has been estimated to result in gall bladder cancer in genetically predisposed individuals. Treatment of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis by surgical removal of the gall bladder has significantly decreased the incidence of gall bladder cancer (93).

Association Between Obesity Linked and Young Adult Cancers

Of the 13 cancers identified by the IARC as being associated with increased body fatness (6), most have their highest incidence rates in older adults. However, five of the 13 obesity associated cancers including breast, thyroid, uterus, ovary and stomach cancer have been identified by US SEER data as occurring in the top 20 cancers in 20–39 year old females and five of the 13, including colorectal, thyroid, kidney, stomach and liver cancer have been identified in the top 20 in 20–39 year old males (18). Of the 13 IARC obesity associated malignancies, all but gallbladder cancer have been well documented to occur in significant numbers in the under 50 year old age group and four of these malignancies, colorectal, breast, thyroid, and possibly pancreatic cancer in women are reported to be increasing in the young adult population. Moreover, five premalignant precursors including CRA for CRC, BE for EAC, NAFLD for HCC, DCIS for breast cancer, and MGUS for MM are reported to be increasing in the young adult population in association with obesity. In addition, excess body weight and/or weight gain has been noted to precede presentation of these malignancies by long latent periods in some cases by multiple decades.

In summary, many of the malignancies noted to occur with increasing frequency in young adults are among the 13 obesity associated cancers. With the expanding worldwide incidence of overweight and obesity in children and young adults, the long latency period associated with many sporadic cancers, the demonstration in humans and animal models that obesity accelerates the development of cancer, and the probability that even obesity at young age has a long term effect on tumor progression, it is highly likely, if not imminent that obesity will lower age of occurrence across the age spectrum shifting multiple malignancies to younger age groups in general, and to the young adult population in particular.

Overall, this assessment is limited since many of the reports of malignancies in young adults do not provide anthropomorphic measurements. Moreover, evaluation of these data often underestimates obesity since patients with advanced malignancy frequently present for evaluation after significant weight loss. Further evidence of an association of cancer and obesity in young adults will require more consistent reporting of anthropomorphic data at time of diagnosis as well as premorbid data when available. Since body mass may be considerably reduced at time of cancer diagnosis, it is important that these data be monitored in a prospective fashion among the healthy pediatric and YA population and made available for analysis if and when malignancy is diagnosed. However, documenting and reporting this information is critically important to more firmly establish the relation of obesity to young adult cancers.

Disrupting the Linkage Between Obesity and Young Adult Cancers

These data cited above portends an imminent threat of the impact of the obesity pandemic on an age shift in occurrence of obesity associated malignancies including their appearance in young adults. This occurrence will require increased cooperation between adult, adolescent and pediatric oncologists, endocrinologists and weight management professionals for effectively evaluating and dealing with the looming crisis. The most effective way to curtail development of this problem is to prevent expansion of the obesity pandemic in both children and adults. This is a critical challenge since there are already 110 million children and adolescents and 640 million adults with obesity on a worldwide basis who constitute the at risk pool for development of obesity accelerated malignancies (94, 95). Moreover, this at risk population is even further expanded by the demonstration that the effects of overweight/obesity may have a long latent period and in some cases, precede the diagnosis of malignancy by decades. Thus an important goal for medical professionals and supporting agencies is to encourage obesity prevention, weight loss and increased physical activity, in both children and young adults (3). In some cases, extreme measures such as bariatric surgery are being considered in children and young adults with obesity because of the potential consequences of disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome and fatty liver disease. Special attention needs to be focused on detecting, monitoring and reversing metabolic syndrome in all patients, especially young adults.

Interestingly, the demonstration that ASA reduced incidence of CRC in young HNPCC patients who were obese, (51) indicates the importance of further research to improve cancer prevention strategies in patients with hereditary cancer syndromes and in young adults that are overweight or obese more broadly (51). Like ASA, potential chemopreventive agents for obese YA must be relatively nontoxic and safe for long term administration. Metformin, extensively used for treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, has already been shown, at low dose, to be safe and reduce recurrence of colorectal adenoma in nondiabetic patients following initial polyp resection (96). Since obesity promoted cancers have been shown, in some cases, to involve epigenetic changes (97), other potential opportunities for chemoprevention in YA includes the use of epigenetic targeted therapies (98).

In terms of screening the young adult population for early signs of malignancy, what is clearly needed is a series of easily administered, minimally invasive and cost effective screening tools. These might include training and encouraging young women with obesity to perform breast self-examination, regular thyroid palpation by medical and dental practitioners, stool DNA testing for both upper and lower GI pathologies (99), and further development of screening blood tests for circulating DNA, circulating tumor cells and other potential biomarkers (100). Since overweight and obesity are lifestyle consequences, it is possible that they can be sufficiently altered by lifestyle modifications to avert the impending expansion of young adult cancers.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this subject? Please remember to also include this between the title page and structure abstract in your paper

-

-

Cancer in young adults is increasing.

-

-

Obesity is at pandemic levels.

-

-

Obesity increases risks of morbidity and mortality for 13 human cancers.

What does this study add? Please remember to also include between the title page and structured abstract in your paper

-

-

Reviews clinical epidemiologic evidence for appearance of 13 human obesity-linked cancers in young adults.

-

-

Reviews animal and human data showing obesity accelerates cancer development.

-

-

Provides mechanism for obesity accelerating cancer shifting appearance to younger age group.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: During preparation of this manuscript, Dr. Berger was supported by NIH Grants; BETRNet U54CA163060, GI SPORE P50CA150964 & RO1 M000969.

Thanks to Anne Baskin for help with illustration.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bleyer A, Barr R, Hayes-Lattin B, Thomas D, Ellis C, Anderson B. The distinctive biology of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Nature reviews Cancer. 2008;8(4):288–98. doi: 10.1038/nrc2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apovian CM. The Obesity Epidemic — Understanding the Disease and the Treatment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(2):177–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1514957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietz WH. Obesity and Excessive Weight Gain in Young Adults: New Targets for Prevention. Jama. 2017;318(3):241–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nature reviews Cancer. 2004;4(8):579–91. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger NA. Obesity and Cancer Pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1311:57–76. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body Fatness and Cancer — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(8):794–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleary MP. Impact of Obesity on Development and Progression of Mammary Tumors in Preclinical Models of Breast Cancer. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2013;18(3):333–43. doi: 10.1007/s10911-013-9300-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doerner SK, Reis ES, Leung ES, Ko JS, Heaney JD, Berger NA, et al. High-Fat Diet-Induced Complement Activation Mediates Intestinal Inflammation and Neoplasia, Independent of Obesity. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2016;14(10):953–65. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson DW, Hertzer K, Moro A, Donald G, Chang HH, Go VL, et al. High-fat, high-calorie diet promotes early pancreatic neoplasia in the conditional KrasG12D mouse model. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2013;6(10):1064–73. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khasawneh J, Schulz MD, Walch A, Rozman J, Hrabe de Angelis M, Klingenspor M, et al. Inflammation and mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation link obesity to early tumor promotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(9):3354–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802864106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill-Baskin AE, Markiewski MM, Buchner DA, Shao H, DeSantis D, Hsiao G, et al. Diet-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in genetically predisposed mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(16):2975–88. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagawa H. Recent advances in mouse models of obesity- and nonalcoholic steatohepatitisassociated hepatocarcinogenesis. World journal of hepatology. 2015;7(17):2110–8. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i17.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim T-M, Laird PW, Park PJ. The Landscape of Microsatellite Instability in Colorectal and Endometrial Cancer Genomes. Cell. 2013;155(4) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lwin ST, Olechnowicz SW, Fowler JA, Edwards CM. Diet-induced obesity promotes a myelomalike condition in vivo. Leukemia. 2015;29(2):507–10. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Metzinger MN, Lewellen KA, Cripps SN, Carey KD, Harper EI, et al. Obesity Contributes to Ovarian Cancer Metastatic Success through Increased Lipogenesis, Enhanced Vascularity, and Decreased Infiltration of M1 Macrophages. Cancer Res. 2015;75(23):5046–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu W, Cline M, Maxwell LG, Berrigan D, Rodriguez G, Warri A, et al. Dietary vitamin D exposure prevents obesity-induced increase in endometrial cancer in Pten+/− mice. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2010;3(10):1246–58. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quante M, Bhagat G, Abrams JA, Marache F, Good P, Lee MD, et al. Bile acid and inflammation activate gastric cardia stem cells in a mouse model of Barrett-like metaplasia. Cancer cell. 2012;21(1):36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bleyer A, Barr R. Cancer in young adults 20 to 39 years of age: overview. Seminars in oncology. 2009;36(3):194–206. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer Facts and Figures 2017. Atlanta, Georgia: The American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howlander N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary C, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014 [webpage] Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2016. [cited 2017 09/01/2017]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, Renehan PAG, Stevens GA, Ezzati PM, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87(2):159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones S, Chen WD, Parmigiani G, Diehl F, Beerenwinkel N, Antal T, et al. Comparative lesion sequencing provides insights into tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(11):4283–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712345105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science (New York, NY) 2007;318(5853):1108–13. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen AJ, Saiakhova A, Corradin O, Luppino JM, Lovrenert K, Bartels CF, et al. Hotspots of aberrant enhancer activity punctuate the colorectal cancer epigenome. Nature communications. 2017;8:14400. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen DH, LeRoith D. Obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cancer: the insulin and IGF connection. Endocrine-related cancer. 2012;19(5):F27–45. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karunanithi S, Levi L, DeVecchio J, Karagkounis G, Reizes O, Lathia JD, et al. RBP4-STRA6 Pathway Drives Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance and Mediates High-Fat Diet-Induced Colon Carcinogenesis. Stem cell reports. 2017;9(2):438–50. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iyengar NM, Brown KA, Zhou XK, Gucalp A, Subbaramaiah K, Giri DD, et al. Metabolic Obesity, Adipose Inflammation and Elevated Breast Aromatase in Women with Normal Body Mass Index. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2017;10(4):235–43. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang SH, Luo S, Thomas TS, O'Brian KK, Colditz GA, Carlsson NP, et al. Obesity and the Transformation of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance to Multiple Myeloma: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim EJ, Choi M-R, Park H, Kim M, Hong JE, Lee J-Y, et al. Dietary fat increases solid tumor growth and metastasis of 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma cells and mortality in obesity-resistant BALB/c mice. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2011;13(4):R78-R. doi: 10.1186/bcr2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novosyadlyy R, Leroith D. Insulin-like growth factors and insulin: at the crossroad between tumor development and longevity. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2012;67(6):640–51. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng Q, Dunlap SM, Zhu J, Downs-Kelly E, Rich J, Hursting SD, et al. Leptin deficiency suppresses MMTV-Wnt-1 mammary tumor growth in obese mice and abrogates tumor initiating cell survival. Endocrine-related cancer. 2011;18(4):491–503. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Livingston EH, Ko CY. Rates of colon and rectal cancers are increasing in young adults. The American surgeon. 2003;69(10):866–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connell LC, Mota JM, Braghiroli MI, Hoff PM. The Rising Incidence of Younger Patients With Colorectal Cancer: Questions About Screening, Biology, and Treatment. Current treatment options in oncology. 2017;18(4):23. doi: 10.1007/s11864-017-0463-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegel RL, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1695–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SE, Shim KN, Jung SA, Yoo K, Moon IH. An association between obesity and the prevalence of colonic adenoma according to age and gender. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(8):616–23. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levi Z, Kark JD, Barchana M, Liphshitz I, Zavdi O, Tzur D, et al. Measured body mass index in adolescence and the incidence of colorectal cancer in a cohort of 1.1 million males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(12):2524–31. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JY, Jung YS, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, et al. Different risk factors for advanced colorectal neoplasm in young adults. World journal of gastroenterology. 2016;22(13):3611–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i13.3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karanikas M, Esebidis A. Increasing incidence of colon cancer in patients <50 years old: a new entity? Annals of translational medicine. 2016;4(9):164. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.04.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.You YN, Xing Y, Feig BW, Chang GJ, Cormier JN. Young-onset colorectal cancer: is it time to pay attention? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):287–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, Bednarski BK, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975–2010. JAMA surgery. 2015;150(1):17–22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67(3):177–93. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, Mi MP. Obesity in youth and middle age and risk of colorectal cancer in men. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 1992;3(4):349–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00146888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ortiz AP, Thompson CL, Chak A, Berger NA, Li L. Insulin resistance, central obesity, and risk of colorectal adenomas. Cancer. 2012;118(7):1774–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atkin W, Wooldrage K, Brenner A, Martin J, Shah U, Perera S, et al. Adenoma surveillance and colorectal cancer incidence: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. The Lancet Oncology. 2017;18(6):823–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30187-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grahn SW, Varma MG. Factors that increase risk of colon polyps. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2008;21(4):247–55. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1089939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haggar FA, Boushey RP. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2009;22(4):191–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn MM, de Voer RM, Hoogerbrugge N, Ligtenberg MJ, Kuiper RP, van Kessel AG. The genetic heterogeneity of colorectal cancer predisposition - guidelines for gene discovery. Cellular oncology (Dordrecht) 2016;39(6):491–510. doi: 10.1007/s13402-016-0284-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Duijnhoven FJ, Botma A, Winkels R, Nagengast FM, Vasen HF, Kampman E. Do lifestyle factors influence colorectal cancer risk in Lynch syndrome? Familial cancer. 2013;12(2):285–93. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9645-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mork ME, You YN, Ying J, Bannon SA, Lynch PM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, et al. High Prevalence of Hereditary Cancer Syndromes in Adolescents and Young Adults With Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3544–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Movahedi M, Bishop DT, Macrae F, Mecklin JP, Moeslein G, Olschwang S, et al. Obesity, Aspirin, and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Carriers of Hereditary Colorectal Cancer: A Prospective Investigation in the CAPP2 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3591–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.9952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anders CK, Johnson R, Litton J, Phillips M, Bleyer A. Breast cancer before age 40 years. Seminars in oncology. 2009;36(3):237–49. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pike MC, Spicer DV, Dahmoush L, Press MF. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiologic reviews. 1993;15(1):17–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cecchini RS, Costantino JP, Cauley JA, Cronin WM, Wickerham DL, Land SR, et al. Body Mass Index and the Risk for Developing Invasive Breast Cancer among High-Risk Women in NSABP P-1 and STAR Breast Cancer Prevention Trials. Cancer Prevention Research. 2012;5(4):583. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sturtz LA, Melley J, Mamula K, Shriver CD, Ellsworth RE. Outcome disparities in African American women with triple negative breast cancer: a comparison of epidemiological and molecular factors between African American and Caucasian women with triple negative breast cancer. BMC cancer. 2014;14:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Feldman GL. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer due to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2010;12(5):245–59. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181d38f2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guindalini RS, Song A, Fackenthal JD, Olopade OI, Huo D. Genetic anticipation in BRCA1/BRCA2 families after controlling for ascertainment bias and cohort effect. Cancer. 2016;122(12):1913–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kotsopoulos J, Olopado OI, Ghadirian P, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, Isaacs C, et al. Changes in body weight and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2005;7(5):R833–43. doi: 10.1186/bcr1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Virnig BA, Tuttle TM, Shamliyan T, Kane RL. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment, and outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(3):170–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taccoen X, Valeri A, Descotes JL, Morin V, Stindel E, Doucet L, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in adults 40 years old or less: young age is an independent prognostic factor for cancer-specific survival. European urology. 2007;51(4):980–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Albiges L, Hakimi AA, Xie W, McKay RR, Simantov R, Lin X, et al. Body Mass Index and Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Clinical and Biological Correlations. J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beebe-Dimmer JL, Colt JS, Ruterbusch JJ, Keele GR, Purdue MP, Wacholder S, et al. Body mass index and renal cell cancer: the influence of race and sex. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2012;23(6):821–8. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826b7fe9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garg K, Soslow RA. Endometrial carcinoma in women aged 40 years and younger. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(3):335–42. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0654-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ying AK, Huh W, Bottomley S, Evans DB, Waguespack SG. Thyroid cancer in young adults. Seminars in oncology. 2009;36(3):258–74. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Borges AKdM, Miranda-Filho A, Koifman S, Koifman RJ. Thyroid Cancer Incidences From Selected South America Population-Based Cancer Registries: An Age-Period-Cohort Study. Journal of Global Oncology. 2017 doi: 10.1200/JGO.17.00024. JGO.17.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li D, Morris JS, Liu J, Hassan MM, Day RS, Bondy ML, et al. Body mass index and risk, age of onset, and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Jama. 2009;301(24):2553–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.(NCIN) NCIN. Is pancreatic cancer becoming more common in the young? [cited 2017 10/4/2017];NCIN Data Briefing. 2011 Available from: www.ncin.org.uk/databriefings.

- 69.Tingstedt B, Weitkamper C, Andersson R. Early onset pancreatic cancer: a controlled trial. Annals of gastroenterology. 2011;24(3):206–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kew MC. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Journal of hepatocellular carcinoma. 2014;1:115–25. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S44381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Campbell PT, Newton CC, Freedman ND, Koshiol J, Alavanja MC, Beane Freeman LE, et al. Body Mass Index, Waist Circumference, Diabetes, and Risk of Liver Cancer for U.S. Adults. Cancer Res. 2016;76(20):6076–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu J, Shen J, Sun TT, Zhang X, Wong N. Obesity, insulin resistance, NASH and hepatocellular carcinoma. Seminars in cancer biology. 2013;23(6 Pt B):483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Petrick JL, Kelly SP, Liao LM, Freedman ND, Graubard BI, Cook MB. Body weight trajectories and risk of oesophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinomas: a pooled analysis of NIH-AARP and PLCO Studies. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(7):951–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doycheva I, Watt KD, Alkhouri N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescents and young adults: The next frontier in the epidemic. Hepatology. 2017;65(6):2100–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.29068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carson KR, Bates ML, Tomasson MH. The skinny on obesity and plasma cell myeloma: a review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(8):1009–15. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blade J, Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma in young patients: clinical presentation and treatment approach. Leukemia & lymphoma. 1998;30(5–6):493–501. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yanamandra U, Saini N, Chauhan P, Sharma T, Khadwal A, Prakash G, et al. AYA-Myeloma: Real-World, Single-Center Experience Over Last 5 Years. Journal of adolescent and young adult oncology. 2017 doi: 10.1089/jayao.2017.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Birmann BM, Andreotti G, De Roos AJ, Camp NJ, Chiu BCH, Spinelli JJ, et al. Young Adult and Usual Adult Body Mass Index and Multiple Myeloma Risk: A Pooled Analysis in the International Multiple Myeloma Consortium (IMMC) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(6):876–85. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0762-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sagaster V, Kaufmann H, Odelga V, Ackermann J, Gisslinger H, Rabitsch W, et al. Chromosomal abnormalities of young multiple myeloma patients (<45 yr) are not different from those of other age groups and are independent of stage according to the International Staging System. European journal of haematology. 2007;78(3):227–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2006.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Offord JR, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1362–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dhodapkar MV. MGUS to myeloma: a mysterious gammopathy of underexplored significance. Blood. 2016;128(23):2599–606. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-692954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Therneau TM, Kyle RA, Melton LJ, 3rd, Larson DR, Benson JT, Colby CL, et al. Incidence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and estimation of duration before first clinical recognition. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(11):1071–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Landgren O, Rajkumar SV, Pfeiffer RM, Kyle RA, Katzmann JA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among black and white women. Blood. 2010;116(7):1056–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-262394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK. The changing epidemiology of esophageal cancer. Seminars in oncology. 1999;26(5 Suppl 15):2–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pera M, Cameron AJ, Trastek VF, Carpenter HA, Zinsmeister AR. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Gastroenterology. 1993;104(2):510–3. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90420-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oezcelik A, Ayazi S, DeMeester SR, Zehetner J, Abate E, Dunn J, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus in the young. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2013;17(6):1032–5. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Runge TM, Abrams JA, Shaheen NJ. Epidemiology of Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2015;44(2):203–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Portale G, Peters JH, Hsieh CC, Tamhankar AP, Almogy G, Hagen JA, et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients < or = 50 years old: delayed diagnosis and advanced disease at presentation. The American surgeon. 2004;70(11):954–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shao C, Bai LP, Qi ZY, Hui GZ, Wang Z. Overweight, obesity and meningioma risk: a metaanalysis. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e90167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Prabhu VC, Perry EC, Melian E, Barton K, Guo R, Anderson DE. Intracranial meningiomas in individuals under the age of 30; Analysis of risk factors, histopathology, and recurrence rate. Neuroscience Discovery. 2014;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brokaw J, Katsaros D, Wiley A, Lu L, Su D, Sochirca O, et al. IGF-I in epithelial ovarian cancer and its role in disease progression. Growth factors (Chur, Switzerland) 2007;25(5):346–54. doi: 10.1080/08977190701838402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.UK CR. Gallbladder Cancer Incidence Statistics. 2016 Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancertype/gallbladder-cancer/incidence#heading-One.

- 93.Castro FA, Koshiol J, Hsing AW, Devesa SS. Biliary tract cancer incidence in the United States-Demographic and temporal variations by anatomic site. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(7):1664–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ezzati MN-RC. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1377–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Higurashi T, Hosono K, Takahashi H, Komiya Y, Umezawa S, Sakai E, et al. Metformin for chemoprevention of metachronous colorectal adenoma or polyps in post-polypectomy patients without diabetes: a multicentre double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17(4):475–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00565-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rossi EL, de Angel RE, Bowers LW, Khatib SA, Smith LA, Van Buren E, et al. Obesity-Associated Alterations in Inflammation, Epigenetics, and Mammary Tumor Growth Persist in Formerly Obese Mice. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2016;9(5):339–48. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jones PA, Issa JP, Baylin S. Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nature reviews Genetics. 2016;17(10):630–41. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moinova H, Leidner RS, Ravi L, Lutterbaugh J, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Chen Y, et al. Aberrant vimentin methylation is characteristic of upper gastrointestinal pathologies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(4):594–600. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Friedrich MJ. Going With the Flow: The Promise and Challenge of Liquid Biopsies. Jama. 2017;318(12):1095–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.