ABSTRACT

The global spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) is one of the most severe threats to human health in a clinical setting. The recent emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1 among CRE strains greatly compromises the use of colistin as a last resort for the treatment of infections caused by CRE. This study aimed to understand the current epidemiological trends and characteristics of CRE from a large hospital in Henan, the most populous province in China. From 2014 to 2016, a total of 7,249 Enterobacteriaceae isolates were collected from clinical samples, among which 18.1% (1,311/7,249) were carbapenem resistant. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli were the two most common CRE species, with Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPC) and New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases (NDM), respectively, responsible for the carbapenem resistance of the two species. Notably, >57.0% (n = 589) of the K. pneumoniae isolates from the intensive care unit were carbapenem resistant. Furthermore, blaNDM-5 and mcr-1 were found to coexist in one E. coli isolate, which exhibited resistance to almost all tested antibiotics. Overall, we observed a significant increase in the prevalence of CRE isolates during the study period and suggest that carbapenems may no longer be considered to be an effective treatment for infections caused by K. pneumoniae in the studied hospital.

KEYWORDS: carbapenem resistance, Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli

INTRODUCTION

The increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria is recognized as one of the most serious threats to public health worldwide because of the lack of effective antimicrobial drugs in a clinical setting (1, 2). Carbapenems have been considered the most effective antibiotics for the treatment of serious human infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (3). However, their utility has been significantly attenuated by the rapidly increasing prevalence of carbapenemase gene carriage by Enterobacteriaceae, with carbapenem resistance conferred by enzymes such as Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) and New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) (4, 5). Thus, only a limited number of drugs, including polymyxins, fosfomycin, tigecycline, and rifampin, can be used to treat infections caused by these carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains (6, 7). CRE have been classified as an urgent threat by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (in 2013), with up to one-half of patients who develop bloodstream infections caused by CRE succumbing to the illness. CRE strains can be transmitted among patients in a hospital setting, and even more worryingly, the resistance genes can also be transferred to other susceptible bacteria of the same family within an infected host (1, 4).

In China, the incidence of CRE infections has been increasing (8, 9). At the present, the majority of these infections occur in patients receiving significant medical care in hospitals and other health care facilities (1). However, the recent emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1 has increased the severity of these situations (10). Fortunately, the prevalence of clinical mcr-1-carrying Enterobacteriaceae is relatively low at this stage (11, 12). Therefore, to better understand current epidemiological trends and the characteristics of CRE in China, we investigated the prevalence of CRE among isolates collected from one hospital in one of the most populated provinces in China over three consecutive years. We also characterized the main mechanisms conferring carbapenem resistance in the K. pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates collected during this period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling.

All samples were collected between January 2014 and December 2016 from Henan General Hospital, one of the largest hospitals in central China. The hospital contains approximately 3,900 beds, including 250 beds in the intensive care unit (ICU). The clinical samples included blood, urine, pleural fluid, and ascites.

Identification and characterization of clinical isolates.

All of the Enterobacteriaceae were isolated according to a previously described protocol (13). Species identification for each of the isolates was conducted using the Vitek2 system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France) and confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry analysis as per the manufacturer's instructions (Bruker Microflex LT; Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). The presence of carbapenem and colistin resistance genes blaKPC, blaNDM, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA-48, and mcr-1 was detected using PCR analysis as described previously (10, 14). All PCR products of the correct size were sequenced and compared with reference sequences in the GenBank database. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was carried out using pipeline SRST2, which takes Illumina reads as input (15).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The susceptibility of the Enterobacteriaceae isolates to the tested antibiotics was determined by the agar dilution or broth dilution method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (16). The tested antibiotics included cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime, ertapenem, imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, tigecycline, and colistin. The susceptible results for tigecycline and colistin were interpreted according to 2017 EUCAST breakpoints (available at http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/), while the remaining results were interpreted according to the CLSI guidelines (16). CRE were defined as those isolates that showed resistance to one or more of the tested carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem, and ertapenem).

Genome sequencing and analysis of antibiotic resistance genes.

Genomic DNA was extracted using a Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Beijing, China) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Indexed Illumina sequencing libraries were prepared using a TruSeq DNA PCR-free sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the standard protocol and then sequenced by Bionova (Beijing, China) using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform as per the manufacturer's instructions, resulting in 250-bp paired-end reads. The draft genomes were assembled using CLC Genomics Workbench 8.5 (CLC Bio, Aarhus, Denmark). Reference sequences for the antibiotic resistance genes were obtained from the ARG-ANNOT database (17).

Statistical analysis.

A chi-squared test was used to evaluate trends in the proportion of carbapenem-resistant isolates over time, and differences in the proportions of CRE from different departments in the hospital were evaluated by pairwise comparison using the pairwise.prop.test function of the “stats” package available in R statistical software. To detect differences in the prevalence of CRE, a global significance level of 5% was applied, which was adjusted using the “holm” method (18) when multiple comparisons were conducted for individual comparisons.

RESULTS

Overview of Enterobacteriaceae isolates.

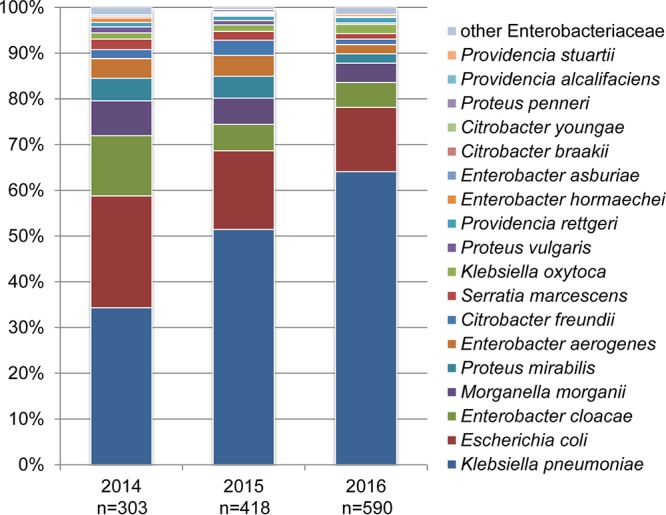

Between 2014 and 2016, a total of 7,249 Enterobacteriaceae isolates were obtained from Henan General Hospital. Of these, 1,311 were characterized as CRE. Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) and carbapenem-resistant E. coli (CREC) were two of the most common species, accounting for 52.9% (697/1,311) and 17.5% (229/1,311) of the total number of CRE isolates, respectively (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). The prevalence rates of other types of CRE, including Enterobacter cloacae, Morganella morganii, Proteus mirabilis, Enterobacter aerogenes, Citrobacter freundii, Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella oxytoca, Proteus vulgaris, Providencia rettgeri, among others, are listed in Table S1.

FIG 1.

Species composition of the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates collected between 2014 and 2016. The number of isolates for each year is shown.

Rising prevalence of carbapenem resistance among Enterobacteriaceae isolates.

A chi-squared test was used to evaluate trends in the prevalence of carbapenem resistance among the isolates by year during the study period. The proportions of both CRE and CRKP isolates among the total number of Enterobacteriaceae isolates increased significantly between 2014 and 2016 (P < 0.0001) (Table 1). Specifically, the proportion of CRE among the total number of Enterobacteriaceae isolates increased from 12.5% (303/2,421) in 2014 to 18.6% (418/2,249) in 2015 and 22.9% (590/2,579) in 2016 (Table 1). The proportion of CRKP among the CRE isolates increased significantly, from 34.3% (104/303) in 2014 to 51.4% (215/418) in 2015 and 64.1% (378/590) in 2016 (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). In comparison, the proportion of CREC among the CRE isolates decreased from 24.4% (74/303) in 2014 to 17.2% (72/418) in 2015 and 14.1% (83/590) in 2016 (P = 0.0002) (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Percentages of carbapenem-resistant isolates among the total number of Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Henan General Hospital, 2014 to 2016

| Yr | No. (%) of carbapenem-resistant isolates/total no. of isolates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniaea | E. colib | Other Enterobacteriaceaeb | Totala | |

| 2014 | 104/524 (19.8) | 74/1,449 (5.1) | 125/448 (27.9) | 303/2,421 (12.5) |

| 2015 | 215/590 (36.4) | 72/1,219 (5.9) | 131/440 (29.8) | 418/2,249 (18.6) |

| 2016 | 378/813 (46.5) | 83/1,246 (6.7) | 129/520 (24.8) | 509/2,579 (22.9) |

| Total | 697/1,927 (36.2) | 229/3,914 (5.9) | 385/1,408 (27.3) | 1,311/7,249 (18.1) |

Data indicate a significant linear increase (P < 0.0001) in the percentage of carbapenem-resistant isolates from 2014 to 2016.

Data indicate no linear relationship between the percentage of carbapenem-resistant isolates and the year.

High prevalence of CRE in the ICU department.

The isolation rates of CRKP and CREC from the ICU were higher than those from other hospital departments. The overall prevalence of carbapenem resistance among the K. pneumoniae isolates was 36.2% (697/1,927), regardless of the department. However, 57.1% (334/589) of K. pneumoniae isolates from the ICU were determined to be carbapenem resistant, which was significantly higher than the proportions from the surgical ward (21.4%, 125/585, P < 0.0001), medical ward (33.9%, 164/484, P < 0.0001), pediatric ward (27.4%, 17/62, P < 0.0001), and other departments (26.7%, 55/207, P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Notably, the total number of K. pneumoniae isolates from the ICU increased almost 3-fold, from 117 in 2014 to 305 in 2016. Moreover, the percentage of CRKP strains among all K. pneumoniae isolated from the ICU increased from 32.5% (38/117) in 2014 to 56.9% (95/167) in 2015 and to 66.6% (203/305) in 2016 (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Similar increases were also observed in most of the other departments, apart from the department of pediatrics. Similarly, the proportion of CREC among all E. coli isolates from the ICU (11.9%, 36/303) was higher than that obtained for the surgical ward (5.5%, 99/1,797), the medical ward (5.5%, 54/986), the pediatric ward (8.5%, 11/130), and other departments (4.2%, 29/698) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Proportion of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolated from different departments at Henan General Hospital, 2014 to 2016

| Organism and hospital department | No. (%) of carbapenem-resistant isolates/total no. of isolatesa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||

| Surgical ward | 29/187 (15.5)Aa | 39/181 (21.5)Aa | 57/217 (26.3)Aa | 125/585 (21.4)Aa |

| Medical ward | 24/143 (16.8)Aa | 48/138 (34.8)BCa | 92/203 (45.3)Bb | 164/484 (33.9)Cb |

| ICU | 38/117 (32.5)Ab | 95/167 (56.9)BCb | 203/305 (66.6)Bc | 336/589 (57.0)Cc |

| Pediatrics | 7/22 (31.8)Aab | 5/17 (29.4)Aab | 5/23 (21.7)Aab | 17/62 (27.4)Aab |

| Other | 6/55 (10.9)Aa | 28/87 (32.2)Ba | 21/65 (32.3)ABab | 55/207 (26.6)ABab |

| Total | 104/524 (19.8)Aa | 215/590 (36.4)Ba | 378/813 (46.4)Cb | 697/1,927 (36.2)Bb |

| E. coli | ||||

| Surgical ward | 32/686 (4.7)Aa | 31/539 (5.8)Aa | 36/572 (6.3)Aa | 99/1,797 (5.5)Aa |

| Medical ward | 15/364 (4.1)Aa | 16/317 (5.0)Aa | 23/305 (7.5)Aa | 54/986 (5.5)Ab |

| ICU | 13/102 (12.7)Ab | 14/95 (14.7)Ab | 9/106 (8.5)Aa | 36/303 (11.9)Ac |

| Pediatrics | 5/41 (12.2)Aab | 2/34 (5.9)Aab | 4/55 (7.3)Aa | 11/130 (8.5)Aabc |

| Other | 9/256 (3.5)Aa | 9/234 (3.8)Aa | 11/208 (5.3)Aa | 29/698 (4.2)Aab |

| Total | 74/1,449 (5.1)Aa | 72/1,219 (5.9)Aa | 83/1,246 (6.6)Aa | 229/3,914 (5.9)Aab |

No common uppercase letters (A to C) in the same row denotes a significant difference in the proportion of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae and E. coli isolates at the 95% confidence level; no common lowercase letters (a to c) in the same column denotes a significant difference in the proportion of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae and E. coli isolates at the 95% confidence level.

Molecular mechanisms of resistance and antimicrobial susceptibility.

To determine the molecular mechanisms associated with carbapenem resistance, 268 CRKP (38.5%) and 34 CREC (14.9%) isolates were randomly selected for detection of the blaKPC, blaNDM, blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaOXA-48 resistance genes. The PCR results indicated that KPC and NDM were major contributors to the carbapenem resistance of the CRKP and CREC isolates collected in this study (Table 3). blaVIM and blaOXA-48 were not detected in any of the isolates. Only one E. coli isolate, from the urine of a female inpatient, was shown to contain the plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1, which coexisted with blaNDM-5. The isolate exhibited resistance to all tested antimicrobial agents except for tigecycline. Whole-genome sequencing indicated that in addition to blaNDM-5 and mcr-1, the isolate contained genes conferring resistance to several other antimicrobial agents, including genes encoding resistance to aminoglycosides [aph(4)-Ia, strA, strB, aadA5, and aac(3)-IId], β-lactams (blaCTX-M-65 and blaTEM-1B), fluoroquinolone (oqxA and oqxB), fosfomycin (fosA), streptogramin B [mph(A)], sulfonamide (sul1 and sul2), tetracycline [tet(A)], and trimethoprim (dfrA17). Multilocus sequence typing indicated that the isolate belonged to ST533.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of different carbapenemases among the carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates

| Organism and carbapenemase | No. of isolates containing indicated carbapenemase/total tested (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | |

| E. coli | ||||

| KPC | 2/13 (15.4) | 0/12 (0.0) | 2/9 (22.2) | 4/34 (11.8) |

| NDM | 8/13 (61.5) | 5/12 (41.7) | 5/9 (55.6) | 18/34 (52.9) |

| IMP | 0/13 (0.0) | 0/12 (0.0) | 0/9 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) |

| Total | 10/13 (76.9) | 5/12 (41.7) | 7/9 (77.8) | 22/34 (64.7) |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||

| KPC | 42/51 (82.4) | 102/112 (91.1) | 93/105 (88.6) | 237/268 (88.4) |

| NDM | 1/51 (1.7) | 7/112 (6.3) | 4/105 (3.8) | 12/268 (4.5) |

| IMP | 3/51 (5.9) | 1/112 (0.9) | 0/105 (0.0) | 4/268 (1.5) |

| Total | 45/51 (88.2)a | 107/112 (95.5)a | 97/105 (92.4) | 249/268 (92.9)a |

Several isolates contained more than one carbapenemase.

The antimicrobial susceptibilities of 249 CRKP isolates and 22 CREC isolates, containing at least one of the KPC, NDM, or imipenem resistance (IMP) genes, to seven drugs (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) commonly used in clinical treatment were also examined. The results indicated that almost all the isolates were resistant to cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime) and amoxicillin-clavulanate (Table S2). The isolates also exhibited high rates of resistance to amikacin (40.9% of CREC and 73.1% of CRKP) and ciprofloxacin (81.8% of CREC and 95.2% of CRKP) (Table S2). Colistin is considered the last-resort agent for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, particularly CRE, and plays an important role in clinical settings. During the study period, colistin was not used for the treatment of CRE infections in this hospital. In the current study, 4.5% (1/22) of CREC and 2.4% (6/249) of CRKP isolates showed resistance to colistin (Table S2).

DISCUSSION

During the 3-year surveillance period, high rates of carbapenem resistance and an increasing trend in the incidence of CRE in normally sterile site cultures, especially those caused by CRKP, were observed at Henan General Hospital. Rapid increases in the prevalence of CRE have been reported globally (8, 9, 19). In Singapore, a sharp increase in the incidence of clinical CRE infections was observed between 2010 and 2011, resulting mainly from a lack of proper intervention (early identification and spatial separation) (19). A nationwide surveillance study of clinical CRE isolates in China from June 2014 to June 2015 indicated that 1.2 to 18.9% of K. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to carbapenems (20). In the current study, the overall prevalence of CRKP (36.2%) among the K. pneumoniae isolates and the prevalence of CRE (18.1%) among the Enterobacteriaceae isolates between 2014 and 2016 were much higher than those recorded by previous reports from the same area (8, 20–22). Previous studies have indicated that CRE infections are associated with poor treatment outcomes (23). As patients in the ICU are usually more vulnerable to bacterial infections, the emergence and high prevalence of CRE represent a deadly threat to these individuals. In our study, CRKP accounted for more than one-half (53.2%, n = 1,311) of the CRE isolates, regardless of the hospital department, and the CRKP isolates from the ICU accounted for almost one-half (48.2%, n = 697) of the total number of CRKP isolates from the hospital (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Of particular concern, the number of K. pneumoniae organisms isolated from the ICU increased significantly during 2014 to 2016, and 66.6% of K. pneumoniae isolates from patients in the ICU in 2016 were carbapenem resistant. These results indicate that carbapenems may no longer be an effective treatment for K. pneumoniae infections in this hospital. Thus, the dissemination of these isolates potentially represents a significant burden to other clinical settings.

Although colistin is considered to be one of the last-resort antibiotics for the treatment of CRE infections, the recent emergence of mcr-1 has significantly compromised the use of colistin in clinical medicine (10). Fortunately, this study determined that the prevalence of colistin-resistant clinical CRKP and CREC isolates was relatively low in this hospital, which is coincident with the results from previous publications (11, 12). In the current study, no CRKP isolates and only one NDM-5-producing CREC isolate was found to be mcr-1 positive. The findings indicate that colistin is still useful for the treatment of CRE in this hospital. The use of colistin in clinical settings was not approved until 2017 in China. Thus, the judicious use of antibiotics is advisable to minimize the development and dissemination of colistin resistance in human isolates.

Accession number(s).

The whole-genome sequencing data obtained in our study for the E. coli isolate containing the plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1 have been deposited in GenBank under accession number PRJNA420595.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 31672604 and 81661138002).

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01932-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wosten MM, Boeve M, Koot MG, van Nuenen AC, van der Zeijst BA. 1998. Identification of Campylobacter jejuni promoter sequences. J Bacteriol 180:594–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho J, Tambyah PA, Paterson DL. 2010. Multiresistant Gram-negative infections: a global perspective. Curr Opin Infect Dis 23:546–553. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833f0d3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vardakas KZ, Tansarli GS, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME. 2012. Carbapenems versus alternative antibiotics for the treatment of bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2793–2803. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R, Chaudhary U, Doumith M, Giske CG, Irfan S, Krishnan P, Kumar AV, Maharjan S, Mushtaq S, Noorie T, Paterson DL, Pearson A, Perry C, Pike R, Rao B, Ray U, Sarma JB, Sharma M, Sheridan E, Thirunarayan MA, Turton J, Upadhyay S, Warner M, Welfare W, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2010. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 10:597–602. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, Schwaber MJ, Daikos GL, Cormican M, Cornaglia G, Garau J, Gniadkowski M, Hayden MK, Kumarasamy K, Livermore DM, Maya JJ, Nordmann P, Patel JB, Paterson DL, Pitout J, Villegas MV, Wang H, Woodford N, Quinn JP. 2013. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis 13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falagas ME, Kopterides P. 2007. Old antibiotics for infections in critically ill patients. Curr Opin Crit Care 13:592–597. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32827851d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taneja N, Kaur H. 2016. Insights into newer antimicrobial agents against Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Insights 9:9–19. doi: 10.4137/MBI.S29459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin S, Fu Y, Zhang Q, Qi H, Wen JG, Xu H, Xu L, Zeng L, Tian H, Rong L, Li Y, Shan L, Xu H, Yu Y, Feng X, Liu HM. 2014. High incidence and endemic spread of NDM-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in Henan Province, China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4275–4282. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02813-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang R, Ichijo T, Hu YY, Zhou HW, Yamaguchi N, Nasu M, Chen GX. 2012. A ten years (2000-2009) surveillance of resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Zhejiang Province, China. Microb Ecol Health Dis 2012:23. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v23i0.11609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X, Yu LF, Gu D, Ren H, Chen X, Lv L, He D, Zhou H, Liang Z, Liu JH, Shen J. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Tian GB, Zhang R, Shen Y, Tyrrell JM, Huang X, Zhou H, Lei L, Li HY, Doi Y, Fang Y, Ren H, Zhong LL, Shen Z, Zeng KJ, Wang S, Liu JH, Wu C, Walsh TR, Shen J. 2017. Prevalence, risk factors, outcomes, and molecular epidemiology of mcr-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in patients and healthy adults from China: an epidemiological and clinical study. Lancet Infect Dis 17:390–399. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan J, Li X, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Zhou Z, Zhang H, Sun L, Ruan Z, Feng Y, Akova M, Yu Y. 2017. Prevalence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae recovered from bloodstream infections in China: a multicentre longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis 17:400–410. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30528-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Carroll KC, Funke G, Landry ML, Richter SS, Warnock DW. 2015. Manual of clinical microbiology, 11th ed ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirel L, Walsh TR, Cuvillier V, Nordmann P. 2011. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 70:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inouye M, Dashnow H, Raven LA, Schultz MB, Pope BJ, Tomita T, Zobel J, Holt KE. 2014. SRST2: rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med 6:90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CLSI. 2016. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 23rd informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S26. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta SK, Padmanabhan BR, Diene SM, Lopez-Rojas R, Kempf M, Landraud L, Rolain JM. 2014. ARG-ANNOT, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:212–220. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01310-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holm S. 1979. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Statistics 6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marimuthu K, Venkatachalam I, Khong WX, Koh TH, Cherng BPZ, Van La M, De PP, Krishnan PU, Tan TY, Choon RFK, Pada SK, Lam CW, Ooi ST, Deepak RN, Smitasin N, Tan EL, Lee JJ, Kurup A, Young B, Sim NTW, Thoon KC, Fisher D, Ling ML, Peng BAS, Teo YY, Hsu LY, Lin RTP, Ong RT, Teo J, Ng OT, Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Singapore Study Group. 2017. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among adult inpatients in Singapore. Clin Infect Dis 64:S68–S75. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang R, Liu L, Zhou H, Chan EW, Li J, Fang Y, Li Y, Liao K, Chen S. 2017. Nationwide surveillance of clinical carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains in China. EBioMedicine 19:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen Y, Xiao WQ, Gong JM, Pan J, Xu QX. 2017. Detection of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (encoded by blaNDM-1) in Enterobacter aerogenes in China. J Clin Lab Anal 31(2). doi: 10.1002/jcla.22044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu A, Zheng B, Xu YC, Huang ZG, Zhong NS, Zhuo C. 2016. National epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria isolated from blood samples in China in 2013. Clin Microbiol Infect 22(Suppl 1):S1–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamma PD, Goodman KE, Harris AD, Tekle T, Roberts A, Taiwo A, Simner PJ. 2017. Comparing the outcomes of patients with carbapenemase-producing and non-carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 64:257–264. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.