ABSTRACT

Multiplexed detection technologies are becoming increasingly important given the possibility of bioterrorism attacks, for which the range of suspected pathogens can vary considerably. In this work, we describe the use of Luminex MagPlex magnetic microspheres for the construction of two multiplexed diagnostic suspension arrays, enabling antibody-based detection of bacterial pathogens and their related disease biomarkers directly from blood cultures. The first 4-plex diagnostic array enabled the detection of both anthrax and plague infections using soluble disease biomarkers, including protective antigen (PA) and anthrax capsular antigen for anthrax detection and the capsular F1 and LcrV antigens for plague detection. The limits of detection (LODs) ranged between 0.5 and 5 ng/ml for the different antigens. The second 2-plex diagnostic array facilitated the detection of Yersinia pestis (LOD of 1 × 106 CFU/ml) and Francisella tularensis (LOD of 1 × 104 CFU/ml) from blood cultures. Inoculated, propagated blood cultures were processed (15 to 20 min) via 2 possible methodologies (Vacutainer or a simple centrifugation step), allowing the direct detection of bacteria in each sample, and the entire assay could be performed in 90 min. While detection of bacteria and soluble markers from blood cultures using PCR Luminex suspension arrays has been widely described, to our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate the utility of the Luminex system for the immunodetection of both bacteria and soluble markers directly from blood cultures. Targeting both the bacterial pathogens as well as two different disease biomarkers for each infection, we demonstrated the benefit of the multiplexed developed assays for enhanced, reliable detection. The presented arrays could easily be expanded to include antibodies for the detection of other pathogens of interest in hospitals or labs, demonstrating the applicability of this technology for the accurate detection and confirmation of a wide range of potential select agents.

KEYWORDS: anthrax, immunodetection, magnetic beads, multiplex, tularemia, blood culture, plague

INTRODUCTION

The increasing threat of bioterrorist attacks has forced the development of rapid detection and identification methods for a wide range of biological agents. Accurate, rapid detection of these potential threats is crucial for the determination of effective measures that will ensure public health protection (1). Since their emergence, immunological tests have been constantly improved to provide such tools, enabling the detection of pathogens and toxins in clinical and environmental setups. One such advanced technology is the xMAP technology by Luminex. This technology enables the multiplexed detection of different biological agents in one sample and has been applied extensively for bacterium, virus, and toxin detection from several complicated matrices (2–11).

The xMAP technology relies on fluorophore-encoded microsphere beads to distinguish between up to 500 capture-based assays performed simultaneously in a single sample. The microspheres are imbued with two different dyes at different concentrations, creating an array of unique microsphere sets. Each distinct color-coded set can be covalently coated with a capture molecule specific to a particular biological target, allowing the simultaneous capture of multiple analytes from a single sample. Conducted with fluorophore-encoded microsphere beads, immunoassays are enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-like assays that are performed on these bead surfaces. Because of the microscopic size and low density of these beads, assay reactions exhibit solution-phase kinetics. However, once the assay is complete, the solid-phase characteristics allow every single bead to be analyzed discretely in the Luminex instrument. Each bead is probed by two lasers: one that establishes the bead's “identity” and another that determines the presence of the analyte (via a suitable fluorophoric reporter molecule).

In this study, we developed multiplexed tests for the detection of three different biological warfare (BW) agents: Bacillus anthracis, Yersinia pestis, and Francisella tularensis, the etiological agents of anthrax, plague, and tularemia, respectively. These pathogens are tier 1 threat agents that can be used to infect humans via various routes and can result in widespread illness (12–15).

Anthrax is caused by the Gram-positive bacterium B. anthracis and is lethal if untreated (16). The virulence of B. anthracis is attributed to the secreted tripartite toxin complex and anthrax poly-γ-d-glutamic acid capsule (17–19). The endotoxins are composed of three proteins: protective antigen (PA), lethal factor, and edema factor, which combine to cause the toxic effect. Studies have shown that PA (20) and circulating capsular antigen (18) can be used as early markers for disease onset.

Plague, caused by Y. pestis, is another devastating disease that has caused millions of deaths throughout human history. Detection of the pathogen's capsular antigen (F1) as a soluble protein has been reported as a reliable and specific marker of plague infection (21–23). We have recently reported that LcrV protein (V antigen [Vag]), part of the type III secretion system of Y. pestis, can also be used as a soluble disease biomarker for early detection of plague (24).

The last select agent addressed in this study is the Gram-negative bacterium F. tularensis. This pathogen is the causative agent of tularemia, a highly infectious and fatal disease that manifests with severe clinical symptoms (25). Unfortunately, despite several attempts over the years involving proteomic studies (26, 27), no soluble disease biomarkers for disease onset or progression have been established.

Since the identification of a bioterror attack may be discovered only after people start manifesting disease symptoms, we chose to construct multiplexed diagnostic arrays for the early detection of bacteria or disease biomarkers from clinical samples, specifically blood cultures. When a person is hospitalized, taking blood for culture is one of the first steps performed when a blood infection is suspected. At this stage, patients would benefit from a short, robust screening test which can be automated for high-throughput operation and detection/validation of a wide range of possible infections.

While PCR-based Luminex detection from blood cultures has been reported previously (28), antibody-based Luminex detection with commercial or “in-house” kits was described only from whole blood, plasma, sera, or dried blood spots (5, 29–34). In this study, we demonstrated for the first time the successful application of two Luminex multiplexed antibody-based suspension arrays for the detection of bacteria (Y. pestis and F. tularensis) and soluble disease biomarkers (PA, anthrax capsular antigen, F1, and Vag) directly from blood cultures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

This study used Luminex MagPlex-C microspheres, 2.5 × 106 particles/ml, regions 26, 28, 44, 45, and 63 (Luminex, Austin, TX; catalog numbers MC10026-01, MC10028-01, MC10044-01, MC10045-01, and MC10063-01), bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO; catalog number A5611), trehalose (Sigma-Aldrich; catalog number T9531), and streptavidin-R-phycoerythrin (SA-R-PE) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA; catalog number 12-4317-87).

Safety considerations.

B. anthracis, Y. pestis, and F. tularensis have been classified as tier 1 select agents. In the United States, possession, use, storage, or transfer of tier 1 organisms requires approval of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Select Agent Program. Handling of these select agents is subject to select agent regulations and should be carried out in a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) laboratory, according to the international guidelines for the use and handling of pathogenic microorganisms. B. anthracis was handled according to the above-mentioned regulations. Notably, in this study, we used as a model for F. tularensis and Y. pestis attenuated strains, i.e., LVS and EV76, respectively, which are exempt from select agent regulations in the United States (https://www.selectagents.gov/SelectAgentsandToxinsExclusions.html). Since these are BSL2 strains, the work was performed in a BSL2 laboratory. At the end of the work, all cultures and plates were disinfected in hypochlorite (500 ppm).

Bacteria.

B. anthracis strain Vollum ATCC 14578 (Tox+ Cap+) was from the Israel Institute for Biological Research collection. B. anthracis capsule reagent was prepared from the supernatant of B. anthracis Vollum grown in nutrient broth yeast extract (NBY-CO3) medium for 48 h with 10% CO2. The supernatant was supplemented with 10% sodium acetate and 1% acetic acid, and the secreted capsule was precipitated using 2 volumes of ethanol. The pellet was then resuspended in 10% sodium acetate and 1% acetic acid and precipitated again. The resulting pellet was lyophilized and resuspended in distilled water. Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica strain LVS (ATCC 29684) was used in either a live or an inactivated form. Inactivation was achieved by exposure of 5 × 109 CFU/ml to 3 doses of UV radiation at 75,000 μj/cm3. The Y. pestis vaccine strain EV76 was grown on brain heart infusion agar (BHIA; Difco) as previously described (35) and was applied, live or inactivated, with 0.4% formaldehyde. Inactivated bacterial strains were used during assay development and calibration. The PA protein was purified as described previously (20). Purified, recombinant F1 and V Y. pestis antigens were prepared as described previously (36, 37).

Antibodies.

Monoclonal immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody against soluble B. anthracis capsule (MαCAP) was raised against soluble B. anthracis capsule and purified from mouse ascitic fluid using an anti-mouse IgM antibody agarose column (Sigma; A4540). An anti-F. tularensis polyclonal IgG fraction was obtained by HiTrap protein G/A (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) chromatography of hyperimmune rabbit serum immunized with the LVS strain (6 repeated doses of 108 to 109 CFU of inactivated bacteria) according to the manufacturer's instructions and dialyzed using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4; Biological Industries, Beth Haemek, Israel; 02-023-1A). Polyclonal anti-Y. pestis antibodies were prepared as described previously (38). IgG fractions of hyperimmune rabbit anti-F1, anti-LcrV, and anti-PA antibodies were purified using HiTrap protein G, as described above. Monoclonal mouse anti-PA (m55) was described previously (39).

The specificity of the various antibodies was addressed previously. The polyclonal anti-Y. pestis antibodies were characterized against various Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and the closely related enteropathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, using flow cytometry (38). The antibodies did not exhibit any nonspecific binding against these bacteria. As expected, besides the EV76 strain, the antibodies recognized the inactivated, virulent Y. pestis strain Kimberly53 (40). The specificity of the polyclonal antitularemia antibodies was also characterized previously using biolayer interferometry (41), and the antibodies did not exhibit any cross-reactivity with either E. coli or Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium; however, they did successfully detect virulent, inactivated F. tularensis Shue S4. While other bacilli are known to produce a polymer similar to poly-γ-d-glutamic acid (42), the PA antigen is very specific, and the combination of it and anti-poly-γ-d-glutamic acid antibodies (CAP antibodies) indicates the occurrence of an anthrax infection.

Antibody labeling.

Biotinylation of IgG purified antibody fractions was performed using sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin [sulfosuccinimidyl-2-(biotinamido) ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate] (Pierce, Waltham, MA; catalog number 21331) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The number of biotins per antibody was calculated using the HABA [2-(4-hydroxyazobenzene)benzoic acid] method (Pierce; 28050) and was four biotin molecules per antibody on average.

Preparation of microspheres.

Specific antibodies were coupled to unique Luminex beads using a Luminex antibody coupling kit (catalog number 40-50016) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In the coupling reaction, 5 μg of each specific antibody was used per 1 × 106 microbeads. Coupling was confirmed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Bead-based detection assays.

Optimizations of the Luminex tests for each of the individual antigens tested were performed separately. Assays were carried out in a final volume of 100 μl in 96-well black microplates (Greiner; PP F-Bottom chimney well, catalog number 655209). The assay mixture (50 μl) contained both antibody-coupled Luminex magnetic beads (5 × 104 beads/ml) and biotinylated specific reporter antibodies diluted in assay buffer (PBS plus 2% normal rabbit serum plus 0.05% Tween 20) as depicted in Fig. 1. For each of the developed tests, a matrix of reporter antibody concentrations (1 to 4 μg/ml) was scanned to establish the optimized concentration of the biotin-labeled antibody (Bio-Ab). Antigen, diluted in PBS or blood culture (50 μl), was added to the assay mixture and agitated at room temperature for 30 min in an orbital microshaker (Dynatech, England). For the agitation period, plates were covered with aluminum foil (USA Scientific; TempPlate sealing foil, catalog number 2923-0100). The plates were then washed on a microplate washer (Tecan; Hydrospeed, catalog number 30054550) equipped with a smart-2MBS 96-well magnetic plate. Captured beads were resuspended in 50 μl of assay buffer containing 2 μg/ml of SA-R-PE and incubated in the dark for an additional 20 min. After a final wash, the beads were resuspended in 60 μl of PBS, and the resulting R-PE signal was determined using a Luminex MAGPIX.

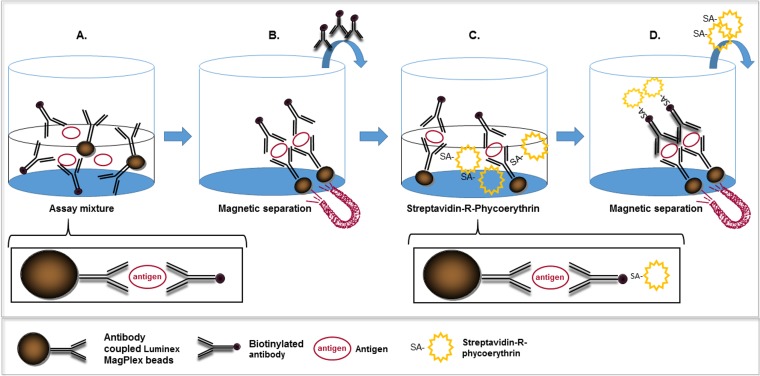

FIG 1.

Schematic representation of the microsphere-based assay utilized in this study. The assay consisted of four consecutive steps: coincubation (30 min) of the antigen-containing sample with a suspension of specific antibody-coated Luminex MagPlex beads and biotinylated specific antibodies, leading to the formation of a sandwich immunoassay linked to the magnetic beads (a), separation of unbound components using magnetic force (b), incubation (20 min) of the sandwich immunoassay with SA-R-PE (c), and separation of unbound components using magnetic force (d). The assay was then resuspended in PBS and analyzed in the Luminex MAGPIX instrument.

Multiplexed suspension assays.

Multiplexed assays were performed as described for the individual assays. Reagents (specific color-coded antibody-coupled beads and biotin-labeled reporter antibodies for each of the antigens) were added concomitantly.

Preparation of clinical samples.

Y. pestis EV76 was grown on BHIA (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ; catalog number 241830) plates at 28°C for 48 h. Colonies were suspended in sterile PBS and added at a defined concentration (500 CFU/ml) into Bactec plus aerobic/F culture vials (BD; catalog number 442192) supplemented with 10 ml of naive human blood. The inoculated blood culture vials were then shaken at 150 rpm at 37°C in a New Brunswick Scientific C76 water bath for different periods (17, 23, 29, and 40 h). Final CFU counts for each vial were determined by plating 0.1-ml quantities of serial 10-fold dilutions on BHIA plates and incubating them for 48 h at 28°C.

F. tularensis subsp. holarctica vaccine strain LVS was grown on CHA plates (GC medium base, supplemented with 1% cystine heart agar; Difco; catalog number 247100-BD) and 1% hemoglobin (BBL; catalog number 212392-BD) at 37°C for 48 h. Individual colonies were grown at 37°C in TSBC (tryptic soy broth [TSB; Difco] supplemented with 0.1% cysteine) to mid-log phase (density of 0.1 to 0.2 at 660 nm), added to Bactec plus aerobic/F culture vials (1 × 104 CFU/ml) supplemented with 10 ml of naive human blood as described for EV76, and shaken for different periods (24, 48, and 72 h). CFU counts were determined by plating on CHA plates.

B. anthracis Vollum spores were inoculated (5 × 106 CFU) in Bactec plus aerobic/F culture and Bact/Alert (bioMérieux Inc. Marcy-l'Étoile, France; catalog number 410851) vials supplemented with 10 ml of naive human blood. The inoculated blood culture was shaken at 70 rpm at 37°C in a New Brunswick Scientific shaker for 24 h. The resulting blood cultures for the different select agents were processed as described in the next section.

Blood culture processing.

For detection of soluble disease biomarkers, blood cultures were centrifuged (14,000 × g for 5 min) and the supernatant was applied directly to the assay. In the case of B. anthracis cultures, supernatants were also filtered (0.22 μm) before application. For bacterial detection, blood cultures were processed via either a Vacutainer or a stepwise centrifugation approach (see Fig. 4). In the first approach, 5 ml of blood culture sample was centrifuged (1400 × g for 10 min) in a Vacutainer serum separation tube (VSST; BD). The resulting bacterial layer, located on the separating gel, was resuspended in 500 μl of PBS, placed in an Eppendorf tube, and washed (PBS). In the second approach, 1.5 ml of culture fluid was centrifuged in a benchtop centrifuge (140 × g for 10 min) to sediment the blood cells. The bacterial fraction in the recovered supernatant was pelleted by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 5 min), washed with 1 ml of PBS, and resuspended in 200 μl of PBS.

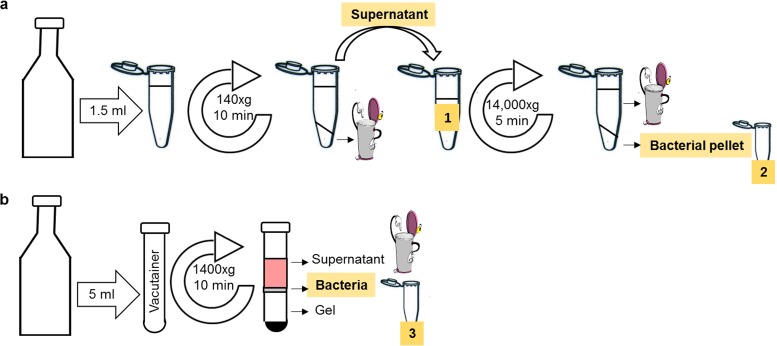

FIG 4.

Blood culture processing procedures for bacterial detection. Blood cultures were processed either with a stepwise centrifugation approach (a) or with a Vacutainer (b). The stepwise centrifugation methodology consisted of a mild centrifugation (140 × g for 10 min) of 1.5 ml of culture fluids. The recovered supernatant (indicated as 1 and highlighted in yellow) was then sedimented (14,000 × g for 5 min), and the pellet (indicated as 2 and highlighted in yellow) was washed with 1 ml of PBS and resuspended in 200 μl of PBS. In the second approach, a 5-ml blood culture sample was centrifuged (1,400 × g for 10 min) in a Vacutainer. The resulting bacterial layer, located on the separating gel, was resuspended in 500 μl of PBS and placed in an Eppendorf tube (indicated as 3 and highlighted in yellow). All bacterium-containing blood fractions that were implemented in the test are indicated in yellow.

Signal analysis.

R-PE signals were calculated as signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios between the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of an antigen (S) or PBS (N)-containing sample for each bead population. A test was considered positive when the S/N ratios were ≥2. This calculation enabled the normalization of multiple experiments and the determination of a universal threshold for positive samples. To evaluate the limit of detection (LOD), the average background MFI readings for each assay were calculated as the mean response of at least six “noise” (PBS) samples for each antibody-coated bead population. The LOD was defined as 5 standard deviations (SDs) above the average background, with a coefficient of variation (CV) of <15%. These values yielded a signal (noise + 5 SDs)-to-noise (average noise) threshold, which was considered the LOD threshold. All tests exhibited S/N ratios that were lower than 2. For simplicity in data presentation and comparison, a value for S/N of ≥2 was set as the positive threshold for all assays in accordance with International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) guidelines for the validation of analytical procedures (43).

Statistical analysis.

The statistical differences between the S/N ratios of the 3 blood samples, processed via the 2 different methodologies, were analyzed using t tests, comparing S/N ratios with GraphPad Prism for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Development of magnetic microsphere-based immunoassays.

The basic principle of the assay used in this study is depicted in Fig. 1. The assay consisted of antibody-coated Luminex MagPlex magnetic beads and antigen-specific biotinylated reporter antibodies that were cosuspended with antigen-containing sample. The resulting sandwich immunoassay linked to the magnetic beads was then washed using a magnetic force, and the beads were resuspended with the reporter molecule SA-R-PE. After another separation step, the beads were resuspended in PBS and analyzed using the Luminex MAGPIX instrument, which enabled differentiation between the unique fluorophore-encoded microbeads and quantitation of the R-PE fluorescence of each bead. The mean fluorescence of each bead population was proportional to the amount of relevant specific antigen in the sample. Throughout, the results are presented as S/N ratios, where the signal arises from the mean fluorescence of an analyte-containing sample and the noise arises from a PBS-containing sample for each bead population. The resulting assays were rapid (total of 60 min) and sensitive and exhibited a wide dynamic range (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

To facilitate the simultaneous detection of the anthrax, plague, and tularemia agents from blood cultures, two separate multiplexed diagnostic arrays were developed. One array enabled the detection of soluble disease biomarkers, and the other enabled the detection of bacterial pathogens.

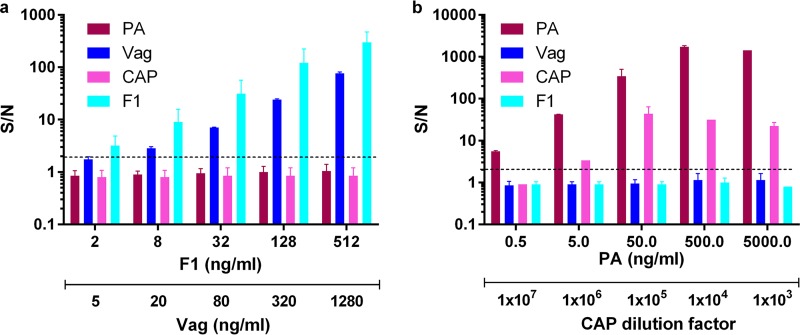

Detection of disease biomarkers from blood cultures utilizing a 4-plex soluble diagnostic array.

A 4-plex diagnostic suspension array was constructed for the sensitive detection of anthrax and plague by means of soluble disease biomarkers. The biomarkers incorporated in the array included PA and anthrax soluble capsular antigen (CAP) for anthrax detection and F1 and V antigen (Vag) for plague detection. To this end, four separate Luminex tests were independently calibrated and incorporated in the array. To demonstrate the applicability of the developed array for antigen detection from blood culture vials, blood cultures containing naive human blood were centrifuged and spiked with a mixture of recombinant F1 and Vag or with a mixture of purified PA and soluble anthrax capsular antigen. The results are presented in Fig. 2. As shown in Fig. 2a, each of the two plague biomarkers was identified in the blood culture (light blue columns for F1 and dark blue columns for Vag). No cross-reactivity was observed on MagPlex beads coupled to anti-PA (Bordeaux columns) or anti-CAP (pink columns) antibodies. Similarly, the PA and CAP anthrax disease markers could be detected from spiked blood culture samples by the MagPlex beads coupled to anti-PA or anti-CAP antibodies. In this case, no cross-reactivity was observed with anti-F1- or anti-Vag-coupled beads (Fig. 2b). These results clearly demonstrate the applicability of the developed array for accurate detection of relevant disease biomarkers from blood cultures. As has been stated, the S/N ratios presented in the graph were calculated with PBS as the background (noise) sample. It is important to note that nonspiked blood cultures showed some quenching of the mean R-PE fluorescence of each bead population compared with PBS. This phenomenon somewhat depended on the blood sample analyzed (person-to-person differences) and was more pronounced for some bead populations than for others. For example, the mean R-PE fluorescence of anti-CAP-coupled beads in PBS was 53 ± 4, while in nonspiked blood cultures, the observed value was 35 ± 5, resulting in a 30 to 35% reduction in assay performance. In comparison, anti-F1-coupled beads demonstrated a mean R-PE fluorescence of 32 ± 3 in PBS and approximately 29 ± 2 in blood cultures, resulting in little to no reduction in assay performance compared to the PBS-spiked assays (Fig. S1). Since this phenomenon was observed only with some bead populations and not with others, it is possible that implementing a different capture antibody in the indicated tests would prevent quenching and as a result improve test sensitivity in blood samples.

FIG 2.

Dose-response curves of multiplexed immunoassays for the detection of spiked soluble disease biomarkers from blood cultures, implementing the 4-plex diagnostic array. Blood cultures (Bactec plus aerobic/F culture vials) containing naive human blood were centrifuged and spiked with recombinant F1 (light blue) and Vag (blue) for plague detection (a) or purified PA (Bordeaux) and soluble anthrax capsular antigen (CAP) (pink) for anthrax detection (b). Points are the averages of at least three independent sets of measurements. Signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios were calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and the limit of detection for each test was determined for S/N ratios to be ≥2 (black dashed line).

Detection of disease biomarkers from inoculated blood cultures utilizing the 4-plex soluble diagnostic array.

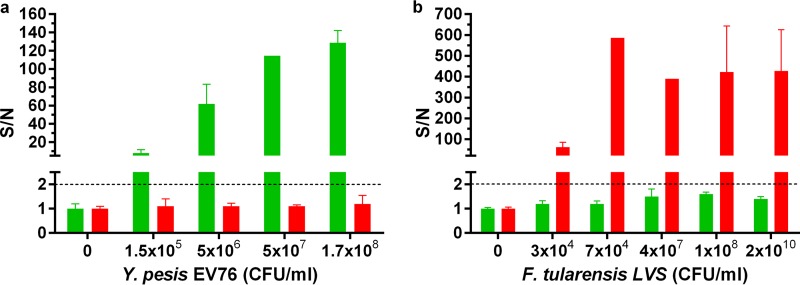

We next wanted to verify that the developed array could be applied for the detection of native proteins produced by the bacteria during growth in the blood culture vial. To this end, the Y. pestis EV76 strain was inoculated into several Bactec blood culture vials containing naive human blood and grown at 37°C for different periods. At the end of the incubation period, blood cultures were centrifuged, and supernatant was collected. The bacterial concentration in each vial was determined based on viable counts. The presence of the soluble disease markers was analyzed directly by the multiplexed array. As can be seen in Fig. 3a, soluble biomarkers could be detected only when bacterial growth was equal to or exceeded 5 × 106 CFU/ml. F1 concentrations, calculated based on the F1 spiked calibration curve (Fig. 2a), varied between two independent experiments: 44, 90, and 2,935 ng/ml of F1 were determined in the cultures containing 5 × 106, 5 × 107, and 1.7 × 108 EV76 CFU/ml, respectively, and 0, 7, and 405 ng/ml of F1 were determined in the cultures containing 1 × 105, 2.5 × 106, and 1.4 × 108 EV76 CFU/ml, respectively. These results indicate that biomarker production fluctuates during growth and is likely dependent on the different conditions implemented in each experiment (a different naive blood source, bacterial concentration variations in the inoculum and in the final plating, etc.). While the exact amount of soluble F1 protein varied between the experiments, both experiments showed that a positive F1 signal was clearly detected for cultures in which bacterial concentrations were as low as 2 × 106 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml.

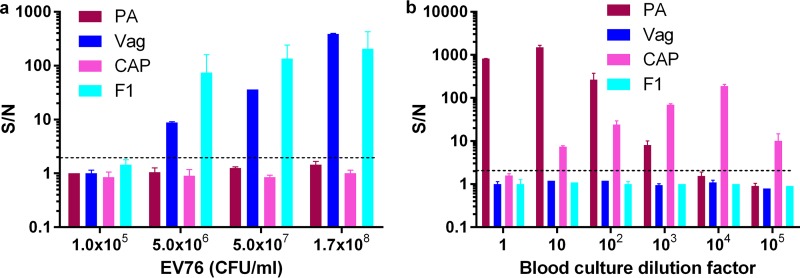

FIG 3.

Detection of native disease biomarkers from inoculated blood cultures utilizing the 4-plex soluble diagnostic array. Blood cultures (Bactec plus aerobic/F culture vials) containing naive human blood were inoculated with Y. pestis EV76 bacteria (a) or B. anthracis Vollum spores (b) and incubated at 37°C. Blood cultures were then centrifuged and plague biomarkers, F1 and Vag, or anthrax biomarkers, PA and capsular antigen, were measured with the soluble 4-plex array. S/N ratios were calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and the limit of detection for each test was determined for S/N ratios to be ≥2 (black dashed line).

To assess anthrax biomarker detection from blood cultures, B. anthracis Vollum spores were inoculated into a blood culture vial and grown at 37°C to an estimated concentration of ∼1 × 108 CFU/ml (based on microscopic observation). In this case, bacterial concentration could not be quantitated accurately due to the extremely long, “chain-like” appearance of B. anthracis in blood cultures. The resulting secreted disease markers were determined in 10-fold-diluted samples, utilizing the 4-plex diagnostic array. The results are presented in Fig. 3b. Both tests (PA in Bordeaux columns and CAP in pink columns) exhibited the “hook” effect (the PA test to a lesser degree), where at high antigen concentrations (for example, the nondiluted blood culture), the reporter antibody was washed out with excess antigen molecules, resulting in a low S/N ratio. This phenomenon typically occurs in homogenic tests due to the simultaneous presence of all reagents. While it prevents accurate quantitation, the “hook” effect does not hinder detection, which is the major aim of these developed tests. For accurate quantitation, the samples must be diluted to within the logarithmic phase of the test. No cross-reactivity was observed on MagPlex beads coupled to anti-F1 (light blue) or anti-Vag (dark blue) antibodies. Surprisingly, the capsular B. anthracis antigen could be detected even after PA was diluted out (1 × 105-fold dilution of the culture). A similar phenomenon was observed in a repeated experiment that was performed with a BactAlert blood culture vial (data not shown). In both cases, using the spiked PA calibration curve, PA, which was secreted by B. anthracis bacteria, was estimated to be in the microgram range (approximately 5.5 μg/ml and 3 μg/ml for Bactec and BactAlert, respectively). Similar PA concentrations were observed in the sera of infected rabbits with estimated bacteremia levels of 1 × 108 CFU/ml (20).

The results presented indicate that the developed 4-plex diagnostic array is suitable for accurate, simultaneous detection of both anthrax and plague via secreted disease biomarkers directly from blood cultures.

Detection of spiked bacteria from blood cultures utilizing a 2-plex diagnostic array.

The previous section demonstrated the implementation of a diagnostic array suitable for the detection of soluble disease biomarkers directly from blood cultures. However, in cases where no soluble disease markers are established, as is the case for tularemia, there is a need for direct bacterial detection. We initially attempted to develop a 3-plex diagnostic array that included anti-CAP, anti-F. tularensis, and anti-Y. pestis antibody-coupled beads. This diagnostic array would have enabled the detection of anthrax, tularemia, and plague simultaneously from blood cultures. However, these attempts failed due to clogging problems that occurred while analyzing B. anthracis-spiked samples (in PBS) in the Luminex instrument, likely due to the bacterial chains formed by anthrax bacteria, resulting in large multibacterium-bead aggregates. Therefore, we settled on the development of a 2-plex diagnostic array for bacterial detection. A 2-plex diagnostic array was assembled and calibrated for detection of Y. pestis and F. tularensis bacteria from blood cultures.

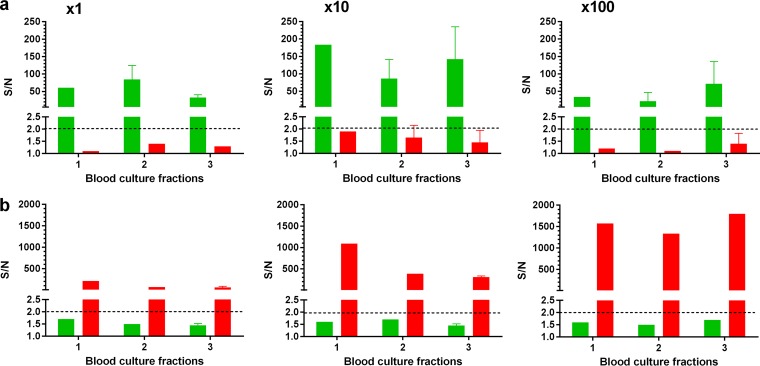

As was demonstrated in the previous sections, the soluble 4-plex diagnostic array was applied for biomarker detection from centrifuged blood culture samples. Since this fraction does not contain bacteria, we applied the 2-plex bacterial detection array on unprocessed blood culture samples that were taken directly from the blood culture vials. Despite the fact that the assay contained two washing steps (Fig. 1), we again encountered clogging problems while reading the assay in the MAGPIX instrument. In this case, clogging was a direct result of the unprocessed blood culture matrix, because no such phenomenon was observed when spiking Y. pestis or F. tularensis in centrifuged blood cultures. Therefore, we decided to assess two possible blood processing methodologies: a stepwise centrifugation approach or a Vacutainer, as depicted in Fig. 4a and b, respectively. The stepwise centrifugation approach was based on previous work, in which blood culture samples were processed for bacterial detection via mass spectrometry (44). The procedure was altered to our needs and consisted of a mild centrifugation step (140 × g for 10 min) for blood cell removal, followed by bacterial sedimentation (14,000 × g for 5 min) from the recovered supernatant. The pellet was then washed and resuspended in PBS, resulting in a 5-fold concentration of the original sample. The second approach consisted of centrifugation of the blood culture sample in a Vacutainer (1,400 × g for 10 min). The resulting bacterial layer, located on the separating gel, was resuspended in PBS, resulting in an estimated 10-fold concentration of the sample. To determine which fraction is suitable for direct detection of bacteria from blood cultures, vials containing naive human blood were inoculated with either Y. pestis strain EV76 or F. tularensis strain LVS and grown to 1 × 108 or 1 × 1010 CFU/ml, respectively. The supernatant fraction after the first mild centrifugation step (indicated as 1 and highlighted in yellow in Fig. 4a), the precipitated bacteria (indicated as 2 and highlighted in yellow in Fig. 4a), and the Vacutainer bacterial fraction (indicated as 3 and highlighted in yellow in Fig. 4b) were assessed for direct application in the 2-plex multiplexed test. The fractions were implemented both as is and in 10-fold dilutions, with the results presented in Fig. 5. As can be seen, the bacteria could be specifically detected, with no cross-reactivity on the nonspecific antibody-coupled bead set. Noninoculated blood cultures, which were processed in a similar manner, did not exhibit any false-positive signal for each of the two developed tests. We found (Fig. 5) that all three fractions (indicated in yellow in Fig. 4) are equally suitable for direct bacterial detection (P values of 0.8 > P > 0.2 for EV76 and LVS), though the Vacutainer fraction (Fig. 5a) (100-fold dilution) demonstrated a slight advantage (P values of 0.09 > P > 0.06). Fractions 2 and 3 were selected for further studies due to the concentration effects achieved by both methodologies (which might be advantageous at lower antigen concentrations).

FIG 5.

Evaluation of blood culture fractions for bacterial detection. Blood cultures (Bactec plus aerobic/F culture vials) containing naive human blood were inoculated with Y. pestis EV76 (green) (a) or F. tularensis LVS (red) (b) and incubated at 37°C to a final concentration of 1 × 108 or 1 × 1010 CFU/ml, respectively (determined by viable counts). The resulting blood cultures were processed with the stepwise centrifugation approach or with a Vacutainer. Fractions 1, 2, and 3 (indicated in yellow in Fig. 4) were tested with the 2-plex diagnostic array, undiluted or at 10- and 100-fold dilutions. S/N ratios were calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and the limit of detection for each test was determined for S/N ratios to be ≥2 (black dashed line).

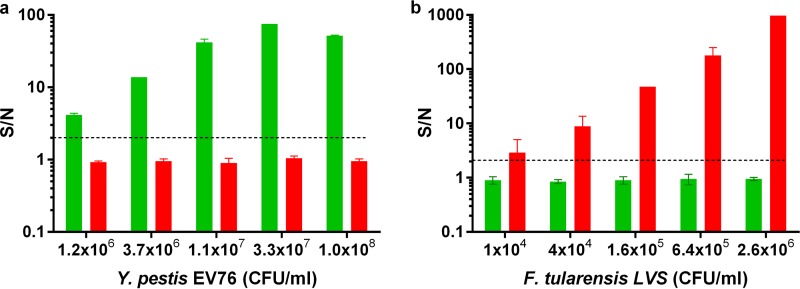

To demonstrate the feasibility of implementing the 2-plex array for bacterial detection, we used the supernatant fraction prepared from naive, noninoculated blood cultures for spiking of inactivated bacteria. As can be seen in Fig. 6, spiked bacteria were detected, with no cross-reactivity and with LODs similar to those in the PBS-spiked samples.

FIG 6.

Dose-response curves of multiplexed immunoassays for the detection of spiked bacteria from blood cultures implementing the 2-plex diagnostic array. Blood cultures (Bactec plus aerobic/F culture vials) containing naive human blood were mildly centrifuged (140 × g for 10 min) and spiked with inactivated Y. pestis EV76 (green) (a) or inactivated F. tularensis LVS (red) (b). Points are the averages of at least three independent sets of measurements. S/N ratios were calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and the limit of detection for each test was determined for S/N ratios to be ≥2 (black dashed line).

Detection of bacterial growth in blood cultures utilizing a 2-plex diagnostic array.

To evaluate the suitability of the 2-plex Luminex array for direct detection of Y. pestis and F. tularensis from blood cultures, both bacterial agents were inoculated into blood culture bottles containing naive human blood. The cultures were grown at 37°C for different durations, and the resulting bacterial concentrations were determined by viable counts. The blood cultures were processed as described, and fractions 2 and 3 were implemented in the multiplexed test. The results obtained with both fractions were similar, and the slightly improved bacterial detection capability attained with the Vacutainer fractions is presented in Fig. 7. As can be seen, plague bacteria could be easily detected when the final bacterial concentration of the unprocessed blood culture was 1 × 105 CFU/ml (Fig. 7a). Importantly, at these bacterial concentrations, no soluble disease biomarkers were detected (Fig. 3a), indicating that the application of the bacterial array resulted in improved plague detection. No cross-reactivity could be observed with the antitularemia-coupled beads.

FIG 7.

Detection of bacteria from inoculated blood cultures utilizing the 2-plex diagnostic array. Blood cultures (Bactec plus aerobic/F culture vials) containing naive human blood were inoculated with Y. pestis EV76 (a) or F. tularensis LVS (b) and incubated at 37°C for different periods. Blood cultures were then processed using the Vacutainer approach, and the presence of Y. pestis (green) or F. tularensis (red) was measured with the 2-plex array. S/N ratios were calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and the limit of detection for each test was determined for S/N ratios to be ≥2 (black dashed line).

Detection of F. tularensis in blood cultures is presented in Fig. 7b. As can be seen, bacteria could be detected in blood cultures at concentrations as low as 3 × 104 CFU/ml. The S/N ratio observed was quite high (60 ± 20 for different blood cultures from separate experiments containing 1 × 104 to 3 × 104 CFU/ml of bacteria), indicating that the assay would likely be suitable for bacterial detection in samples containing even lower concentrations of bacteria. Again, no cross-reactivity was observed.

DISCUSSION

This work demonstrates the first-time application of Luminex xMAP technology for multiplexed, antibody-based detection of bacterial agents and their related disease biomarkers directly from blood cultures. A 4-plex diagnostic array enabled the simultaneous detection of anthrax and plague using 4 different soluble biomarkers, and a 2-plex diagnostic array enabled the direct detection of both the Y. pestis and F. tularensis pathogens.

The use of two biomarkers for the detection of each disease (PA and capsular antigen for anthrax and F1 and Vag for plague) provides built-in confirmation and reduces the likelihood of both false-negative and false-positive results. The addition of the 2-plex bacterial array increases the credibility and reliability of the diagnostic tests, especially for the identification of atypical Y. pestis strains, such as F1-negative mutants (45, 46). Moreover, in the absence of specific symptoms, impeding detection using standard human biomarkers, it is of great significance that the multiplexed assays enable direct detection of the etiological bacterial agents.

A major benefit of the multiplexed tests is their applicability for disease detection in real-life scenarios, such as clinical labs. The assays enable the detection of 0.5 ng/ml of PA, 2 ng/ml of F1, and 5 ng/ml of Vag or 1 × 104 CFU/ml of F. tularensis and 1 × 106 CFU/ml of Y. pestis within 90 min (blood processing plus multiplexed test) directly from blood cultures. Bacterial growth in the blood cultures is a prerequisite for detection, and the incubation period depends on several factors, such as the bacterial strain, its growth rate, the initial bacterial concentration, etc., and can last between a couple of hours and several days. To eliminate the possibility of both false-positive and false-negative results, the U.S. guidelines advise that once a patient is suspected to be positive for a tier 1 agent, the samples must be shipped to a Laboratory Response Network (LRN) laboratory, where specific and sensitive diagnostic tests can be performed. However, in the clinical sentinel lab, each suspected tier 1 infection is confirmed by a flowchart-recommended series of classical microbiological assays that include growth-based assays (striking on different agar plates and incubating for 1 to 3 days depending on the bacteria) as well as enzymatic and activity-based tests (for B. anthracis, a gamma phage sensitivity and catalase and motility tests; for Y. pestis, catalase, oxidase, indole, and urease tests; and for F. tularensis, oxidase and β-lactamase tests) (47). The immunodetection-based assays presented in this work could complement or even replace any of the recommended growth-based microbiological assays. These assays offer a simple, reliable, and effective result in less than 2 h using a propagated blood culture, while one to several days is required for the growth-related tests. The ability to perform multiple tests simultaneously instead of several independent tests for each antigen reduces time and enables identification while eliminating several predetermined agents, as demonstrated by the two arrays presented in this study. Moreover, the ability to dry the complete bead-based homogeneous immunoassays for long-term storage at room temperature enables simple and easy transportation and handling in remote locations, as was recently shown by us (48). Here we demonstrate that our Luminex-based suspension arrays could be lyophilized and reconstituted successfully, with little immunoassay activity impairment (Fig. S2).

A confirmation of infection is of great importance for tier 1 agents, as it enables disease containment, which is critical, particularly when the agent in question is infective, as is the case for plague. A rapid positive identification also enables the adjustment of patient antibiotic treatment, as well as the administration of prophylactic treatment to at-risk populations when necessary. Globally, a positive identification of a tier 1 agent may indicate a possible bioterrorism event (49), which has tremendous epidemiological and logistical implications and requires decontamination as well as the recruitment of emergency response agencies.

In the process of developing the assay, we encountered a few obstacles that might be of common interest to other developers/users. Instrument clogging is a familiar problem for users of every flow cytometry-like technology that implements micrometer tubing. In the MAGPIX instrument, this type of problem is indicated by the equipment software when the number of analyzed beads is insufficient for the accurate determination of a positive sample, leading to statistically insignificant results. Clogging was encountered during assay development while attempting to directly detect B. anthracis cells because of large multibacterium-bead aggregates that formed due to the long bacterial chains of B. anthracis. However, as indicated by the successful detection of F. tularensis and Y. pestis, this setup efficiently detects planktonic as well as multicell bacteria. Filamentous bacterial growth might impair the test and must be considered when developing assays for other pathogens. For B. anthracis, we overcame aggregation by directly detecting soluble antigens. A second case of clogging was found to be caused by a matrix effect, and it was solved by implementing two short (20 min), interchangeable blood processing methodologies. These procedures removed residual contaminants that originated from the blood culture bottles, thus enabling the direct application of the blood culture samples in the machine.

In this report, we describe the development of two multiplexed arrays that rapidly and sensitively identify tier 1 pathogens in blood cultures and can be incorporated into hospital laboratories. The developed tests were successfully implemented for the multiplexed detection of both soluble biomarkers and bacteria from blood cultures. This general platform can easily be expanded to include other pathogens of interest in hospitals or clinical microbiology laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01479-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kellogg M. 2010. Detection of biological agents used for terrorism: are we ready? Clin Chem 56:10–15. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.139493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunbar SA, Vander Zee CA, Oliver KG, Karem KL, Jacobson JW. 2003. Quantitative, multiplexed detection of bacterial pathogens: DNA and protein applications of the Luminex LabMAP system. J Microbiol Methods 53:245–252. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(03)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garber EA, Venkateswaran KV, O'Brien TW. 2010. Simultaneous multiplex detection and confirmation of the proteinaceous toxins abrin, ricin, botulinum toxins, and Staphylococcus enterotoxins A, B, and C in food. J Agric Food Chem 58:6600–6607. doi: 10.1021/jf100789n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JS, Taitt CR, Ligler FS, Anderson GP. 2010. Multiplexed magnetic microsphere immunoassays for detection of pathogens in foods. Sens Instrum Food Qual Saf 4:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s11694-010-9097-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kofoed K, Schneider UV, Scheel T, Andersen O, Eugen-Olsen J. 2006. Development and validation of a multiplex add-on assay for sepsis biomarkers using xMAP technology. Clin Chem 52:1284–1293. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.067595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satterly NG, Voorhees MA, Ames AD, Schoepp RJ. 2017. Comparison of MagPix assays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of hemorrhagic fever viruses. J Clin Microbiol 55:68–78. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01693-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheppard CL, Harrison TG, Smith MD, George RC. 2011. Development of a sensitive, multiplexed immunoassay using xMAP beads for detection of serotype-specific Streptococcus pneumoniae antigen in urine samples. J Med Microbiol 60:49–55. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.023150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silbereisen A, Tamborrini M, Wittwer M, Schurch N, Pluschke G. 2015. Development of a bead-based Luminex assay using lipopolysaccharide specific monoclonal antibodies to detect biological threats from Brucella species. BMC Microbiol 15:198. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0534-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simonova MA, Valyakina TI, Petrova EE, Komaleva RL, Shoshina NS, Samokhvalova LV, Lakhtina OE, Osipov IV, Philipenko GN, Singov EK, Grishin EV. 2012. Development of xMAP assay for detection of six protein toxins. Anal Chem 84:6326–6330. doi: 10.1021/ac301525q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamborrini M, Holzer M, Seeberger PH, Schurch N, Pluschke G. 2010. Anthrax spore detection by a Luminex assay based on monoclonal antibodies that recognize anthrose-containing oligosaccharides. Clin Vaccine Immunol 17:1446–1451. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00205-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reslova N, Michna V, Kasny M, Mikel P, Kralik P. 2017. xMAP technology: applications in detection of pathogens. Front Microbiol 8:55. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis J, Oyston PC, Green M, Titball RW. 2002. Tularemia. Clin Microbiol Rev 15:631–646. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.631-646.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huxsoll DL. 1992. Narrowing the zone of uncertainty between research and development in biological warfare defense. Ann N Y Acad Sci 666:177–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb38029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jernigan JA, Stephens DS, Ashford DA, Omenaca C, Topiel MS, Galbraith M, Tapper M, Fisk TL, Zaki S, Popovic T, Meyer RF, Quinn CP, Harper SA, Fridkin SK, Sejvar JJ, Shepard CW, McConnell M, Guarner J, Shieh WJ, Malecki JM, Gerberding JL, Hughes JM, Perkins BA, Anthrax Bioterrorism Investigation Team. 2001. Bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax: the first 10 cases reported in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 7:933–944. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inglesby TV, Dennis DT, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Friedlander AM, Hauer J, Koerner JF, Layton M, McDade J, Osterholm MT, O'Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Schoch-Spana M, Tonat K. 2000. Plague as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. JAMA 283:2281–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meselson M, Guillemin J, Hugh-Jones M, Langmuir A, Popova I, Shelokov A, Yampolskaya O. 1994. The Sverdlovsk anthrax outbreak of 1979. Science 266:1202–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.7973702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collier RJ, Young JA. 2003. Anthrax toxin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19:45–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.140655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gates-Hollingsworth MA, Perry MR, Chen H, Needham J, Houghton RL, Raychaudhuri S, Hubbard MA, Kozel TR. 2015. Immunoassay for capsular antigen of Bacillus anthracis enables rapid diagnosis in a rabbit model of inhalational anthrax. PLoS One 10:e0126304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mourez M. 2004. Anthrax toxins. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 152:135–164. doi: 10.1007/s10254-004-0028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobiler D, Weiss S, Levy H, Fisher M, Mechaly A, Pass A, Altboum Z. 2006. Protective antigen as a correlative marker for anthrax in animal models. Infect Immun 74:5871–5876. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00792-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chanteau S, Rahalison L, Ratsitorahina M, Mahafaly Rasolomaharo M, Boisier P, O'Brien T, Aldrich J, Keleher A, Morgan C, Burans J. 2000. Early diagnosis of bubonic plague using F1 antigen capture ELISA assay and rapid immunogold dipstick. Int J Med Microbiol 290:279–283. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Splettstoesser WD, Rahalison L, Grunow R, Neubauer H, Chanteau S. 2004. Evaluation of a standardized F1 capsular antigen capture ELISA test kit for the rapid diagnosis of plague. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 41:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams JE, Arntzen L, Tyndal GL, Isaacson M. 1986. Application of enzyme immunoassays for the confirmation of clinically suspect plague in Namibia, 1982. Bull World Health Organ 64:745–752. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flashner Y, Fisher M, Tidhar A, Mechaly A, Gur D, Halperin G, Zahavy E, Mamroud E, Cohen S. 2010. The search for early markers of plague: evidence for accumulation of soluble Yersinia pestis LcrV in bubonic and pneumonic mouse models of disease. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 59:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLendon MK, Apicella MA, Allen LA. 2006. Francisella tularensis: taxonomy, genetics, and immunopathogenesis of a potential agent of biowarfare. Annu Rev Microbiol 60:167–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eyles JE, Unal B, Hartley MG, Newstead SL, Flick-Smith H, Prior JL, Oyston PC, Randall A, Mu Y, Hirst S, Molina DM, Davies DH, Milne T, Griffin KF, Baldi P, Titball RW, Felgner PL. 2007. Immunodominant Francisella tularensis antigens identified using proteome microarray. Proteomics 7:2172–2183. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaur R, Alam SI, Kamboj DV. 2017. Immunoproteomic analysis of antibody response of rabbit host against heat-killed Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Curr Microbiol 74:499–507. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1217-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balada-Llasat JM, LaRue H, Kamboj K, Rigali L, Smith D, Thomas K, Pancholi P. 2012. Detection of yeasts in blood cultures by the Luminex xTAG fungal assay. J Clin Microbiol 50:492–494. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06375-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Codorean E, Raducanu A, Albulescu L, Tanase C, Meghea A, Albulescu R. 2011. Multiplex cytokine profiling in whole blood from individuals occupationally exposed to particulate coal species. Rom Biotechnol Lett 16:6748–6759. [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Jager W, Bourcier K, Rijkers GT, Prakken BJ, Seyfert-Margolis V. 2009. Prerequisites for cytokine measurements in clinical trials with multiplex immunoassays. BMC Immunol 10:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lerman I, Hauger R, Sorkin L, Proudfoot J, Davis B, Huang A, Lam K, Simon B, Baker DG. 2016. Noninvasive transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation decreases whole blood culture-derived cytokines and chemokines: a randomized, blinded, healthy control pilot trial. Neuromodulation 19:283–290. doi: 10.1111/ner.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moncunill G, Aponte JJ, Nhabomba AJ, Dobano C. 2013. Performance of multiplex commercial kits to quantify cytokine and chemokine responses in culture supernatants from Plasmodium falciparum stimulations. PLoS One 8:e52587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva D, Ponte CG, Hacker MA, Antas PR. 2013. A whole blood assay as a simple, broad assessment of cytokines and chemokines to evaluate human immune responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens. Acta Trop 127:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skogstrand K, Thorsen P, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Schendel DE, Sorensen LC, Hougaard DM. 2005. Simultaneous measurement of 25 inflammatory markers and neurotrophins in neonatal dried blood spots by immunoassay with xMAP technology. Clin Chem 51:1854–1866. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.052241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tidhar A, Flashner Y, Cohen S, Levi Y, Zauberman A, Gur D, Aftalion M, Elhanany E, Zvi A, Shafferman A, Mamroud E. 2009. The NlpD lipoprotein is a novel Yersinia pestis virulence factor essential for the development of plague. PLoS One 4:e7023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zauberman A, Cohen S, Levy Y, Halperin G, Lazar S, Velan B, Shafferman A, Flashner Y, Mamroud E. 2008. Neutralization of Yersinia pestis-mediated macrophage cytotoxicity by anti-LcrV antibodies and its correlation with protective immunity in a mouse model of bubonic plague. Vaccine 26:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holtzman T, Levy Y, Marcus D, Flashner Y, Mamroud E, Cohen S, Fass R. 2006. Production and purification of high molecular weight oligomers of Yersinia pestis F1 capsular antigen released by high cell density culture of recombinant Escherichia coli cells carrying the caf1 operon. Microb Cell Fact 5:P98. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-5-S1-P98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zahavy E, Heleg-Shabtai V, Zafrani Y, Marciano D, Yitzhaki S. 2010. Application of fluorescent nanocrystals (q-dots) for the detection of pathogenic bacteria by flow cytometry. J Fluoresc 20:389–399. doi: 10.1007/s10895-009-0546-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenfeld R, Marcus H, Ben-Arie E, Lachmi BE, Mechaly A, Reuveny S, Gat O, Mazor O, Ordentlich A. 2009. Isolation and chimerization of a highly neutralizing antibody conferring passive protection against lethal Bacillus anthracis infection. PLoS One 4:e6351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vagima Y, Zauberman A, Levy Y, Gur D, Tidhar A, Aftalion M, Shafferman A, Mamroud E. 2015. Circumventing Y. pestis virulence by early recruitment of neutrophils to the lungs during pneumonic plague. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004893. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mechaly A, Cohen H, Cohen O, Mazor O. 2016. A biolayer interferometry-based assay for rapid and highly sensitive detection of biowarfare agents. Anal Biochem 506:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Candela T, Fouet A. 2006. Poly-gamma-glutamate in bacteria. Mol Microbiol 60:1091–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.ICH. November 1996. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline. Validation of analytical procedures: text and methodology. ICH, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christner M, Rohde H, Wolters M, Sobottka I, Wegscheider K, Aepfelbacher M. 2010. Rapid identification of bacteria from positive blood culture bottles by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time of flight mass spectrometry fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol 48:1584–1591. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01831-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis KJ, Fritz DL, Pitt ML, Welkos SL, Worsham PL, Friedlander AM. 1996. Pathology of experimental pneumonic plague produced by fraction 1-positive and fraction 1-negative Yersinia pestis in African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops). Arch Pathol Lab Med 120:156–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drozdov IG, Anisimov AP, Samoilova SV, Yezhov IN, Yeremin SA, Karlyshev AV, Krasilnikova VM, Kravchenko VI. 1995. Virulent non-capsulate Yersinia pestis variants constructed by insertion mutagenesis. J Med Microbiol 42:264–268. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-4-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Association of Public Health Laboratories, American Society for Microbiology. 2016. Clinical laboratory preparedness and response guide. Association of Public Health Laboratories, Silver Spring, MD: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/laboratory-sciences/sentinel-lab-blue-book.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mechaly A, Marx S, Levy O, Yitzhaki S, Fisher M. 2016. Highly stable lyophilized homogeneous bead-based immunoassays for on-site detection of bio warfare agents from complex matrices. Anal Chem 88:6283–6291. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Toole T, Mair M, Inglesby TV. 2002. Shining light on “Dark Winter.” Clin Infect Dis 34:972–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.