Abstract

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is an orphan, fatal, adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder of uncertain etiology that is clinically characterized by various combinations of parkinsonism, cerebellar, autonomic, and motor dysfunction. MSA is an α-synucleinopathy with specific glioneuronal degeneration involving striatonigral, olivopontocerebellar, and autonomic nervous systems but also other parts of the central and peripheral nervous systems. The major clinical variants correlate with the morphologic phenotypes of striatonigral degeneration (MSA-P) and olivopontocerebellar atrophy (MSA-C). While our knowledge of the molecular pathogenesis of this devastating disease is still incomplete, updated consensus criteria and combined fluid and imaging biomarkers have increased its diagnostic accuracy. The neuropathologic hallmark of this unique proteinopathy is the deposition of aberrant α-synuclein in both glia (mainly oligodendroglia) and neurons forming glial and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions that cause cell dysfunction and demise. In addition, there is widespread demyelination, the pathogenesis of which is not fully understood. The pathogenesis of MSA is characterized by propagation of misfolded α-synuclein from neurons to oligodendroglia and cell-to-cell spreading in a “prion-like” manner, oxidative stress, proteasomal and mitochondrial dysfunction, dysregulation of myelin lipids, decreased neurotrophic factors, neuroinflammation, and energy failure. The combination of these mechanisms finally results in a system-specific pattern of neurodegeneration and a multisystem involvement that are specific for MSA. Despite several pharmacological approaches in MSA models, addressing these pathogenic mechanisms, no effective neuroprotective nor disease-modifying therapeutic strategies are currently available. Multidisciplinary research to elucidate the genetic and molecular background of the deleterious cycle of noxious processes, to develop reliable biomarkers and targets for effective treatment of this hitherto incurable disorder is urgently needed.

Keywords: α-synuclein, diagnostic criteria, glio-neuronal degeneration, multiple system atrophy, oligodendroglial proteinopathy, pathogenesis, prion-like seeding

INTRODUCTION

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a rare, rapidly progressing, fatal neurodegenerative disorder of uncertain etiology that is clinically characterized by a variable combination of parkinsonism, cerebellar impairment, autonomic and motor dysfunctions [1]. The term MSA was coined 1969 to pool previously described neurological entities: olivopontocerebellar atrophy (OPCA), the Shy-Drager syndrome, and striatonigral degeneration (SND) [2]. Together with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), MSA belongs to the group of α-synucleinopathies, which are morphologically characterized by abnormal accumulation of fibrillary α-synuclein (αS) [3–6]. αS inclusions in oligodendroglia are the recognized neuropathologic hallmarks of MSA [7] and may even represent a primary pathologic event [8]. Degeneration of multiple neuronal pathways over the course of the disease causes a multifaceted clinical picture. Depending on the predominant clinical phenotype, the disease is sub-classified into a parkinsonian variant (MSA-P) associated with SND, a cerebellar (MSA-C) variant with OPCA with predominant cerebellar features, and a combination of both forms, referred to as “mixed” MSA [9, 10]. The underlying molecular mechanisms are poorly understood, but converging evidence suggests a “prion-like” spreading of misfolded αS to represent a key event in the pathogenic cascade leading to systemic neurodegeneration of this oligodendroglioneuronal proteinopathy [8, 11–16]. Due to overlapping clinical presentations, the distinction between early stage MSA, PD, and atypical parkinsonian disorders (pure autonomic failure or adult-onset cerebellar ataxia) may be difficult [17–22].

Although symptomatic therapies are available for parkinsonism and autonomic failures, their response is often poor if not absent, and no effective disease-modifying therapies are currently available. However, due to remarkable progress in our understanding of the etiopathogenesis of MSA, novel therapeutic targets have emerged from preclinical studies and interventional trials [23]. The focus of the present review is the current knowledge on the neuropathology and etiopathogenesis of MSA.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY

MSA is an orphan disease with an estimated incidence of 0.6–0.7 cases per 100,000 person-years, with a range of 0.1 to 3.0 cases per 100,000 person-years [24], whereas studies from Russia and Northern Sweden reported incidences of 0.1 and 2.4 per 100,000 person-years, respectively [25, 26]. Prevalence estimates range from 1.9 to 4.9 [27, 28] and may reach up to 7.8 after the age of 40 [29]. The incidence increases with age up to 12/100,000 above 70 years [30]. In the Western hemisphere, MSA-P involves about 70 to 80% [31], whereas MSA-C is more frequent in Asian populations accounting for about 67–84%, mixed phenotypes being more common [32–35], probably due to genetic or environmental factors [1, 6]. The motor symptom onset is 56±9 years, with both sexes equally affected [36]. However, like PD, 20 to 75% of MSA cases have a prodromal/preclinical phase with non-motor symptoms including cardiovascular autonomic failure, urogenital and sexual dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, REM sleep behavior disorder, and respiratory disorders, which may precede the motor presentation by months to years [9, 37, 38]. Average age of onset is earlier in MSA-C compared to MSA-P [39, 40], the latter showing a trend to reach more disability [41]. The duration after clinical diagnosis is usually 6 to 10 (mean 9.5) years [23, 31, 42, 43], with few patients surviving more than 15 years [44, 45]. Mean survival is usually similar for both phenotypes [39, 45–47]. Others reported a mean survival time of 7.9 years for MSA-P, with a 5-year survival of 78% [48] or a 43% death rate during 3 years of follow-up [49]. A Pan-American multicenter study revealed that 68% of the participants presented with MSA-P, with an age at onset of 61.5 years and the others with MSA-C at 57.4 years [50]. A prospective cohort study in the US reported a median survival from symptom onset of 9.8 (95% CI 8.8–10.7) years [51]. A Japanese group found that patients with initial cerebellar ataxia had a better prognosis than those with initial parkinsonism or autonomic failure [40]. Early development of severe autonomic failure more than tripled the risk of shorter survival [52, 53]. A recent meta-analysis identified the following variables as unfavorable predictors of survival: severe dysautonomia, early development of combined autonomic and motor features, and early falls; conversely, MSA phenotypes and sex did not predict survival [54]. Among clinically diagnosed synucleinopathies with parkinsonism, MSA-P had the highest risk of death compared with reference patients [55].

ETIOLOGY AND GENETICS

The causes of MSA are unknown; however, as for other neurodegenerative diseases, a complex interaction of genetic and environmental mechanisms seems likely [56]. MSA is a predominantly sporadic disease and a family history of parkinsonism or ataxia is defined as a non-supporting feature in the current diagnostic criteria [9]. However, familial aggregation of parkinsonism has been observed in MSA [57, 58], and autopsy-proven familial cases have been reported. In a few pedigrees, the disease has been transmitted in an autosomal dominant or recessive inheritance pattern [44, 59–62]. Unlike PD, no single gene mutation linked to familial forms and no definite risk factors have been identified. A loss-of-function mutation in the COQ2 gene, encoding the coenzyme Q10 (COQ10)-synthesizing enzyme (4-hydroxybenzoate-polyprenyl transferase), was reported in Japanese familial and sporadic cases [63–66], the association being particularly strong for MSA-C [67–69]. A case of familial MSA was associated with compound heterocygous nonsense (R387X) and missense (V393A) mutations in COQ2 [70]. However, the link between COQ2 gene and MSA risk was not confirmed in other patient populations [64, 66, 71–74]. The COQ2 V393A polymorphism is associated with MSA in other Asian populations than Japanese [68, 75]. This implies that COQ2 polymorphisms are region-specific and do not represent common genetic factors for MSA. Decreased levels of COQ10 in plasma and cerebellum of MSA patients regardless of the COQ2 phenotype indicate impaired COQ biosynthesis which may contribute to the pathogenesis of MSA [76–79] through decreased electron transport in mitochondria and increased vulnerability to oxidative stress [65]. Changes of sequence TMEM230 gene have been reported in MSA patients in southwest China [80], while no differences were found in the genotype distribution and allele frequency of polymorphisms in VMAT2 and TMEM106B between MSA and controls [81]. A discordant loss of copy numbers of SHC 2 was found in monozygotic twins and Japanese patients with sporadic MSA, but not in the US [71, 82]. SNCA polymorphism (encoding αS and other loci), suggested to be associated with increased risks for MSA [83–85], was not confirmed in different patient cohorts [73, 83, 86–89]. Other studies showed that some SNCA polymorphisms are not likely a common cause of MSA in the Chinese population [90]. Two single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the SNCA locus showed a significant association with MSA in European patients [84], while no SNCA multiplications were seen in a series of 58 pathologically confirmed MSA cases [91]. A recent genome-wide association study did not detect any genome-wide significant association between tagged single nucleotide polymorphisms and MSA risk [87]. αS mRNA levels were comparable between MSA and controls, suggesting that αS expression is not the fundamental cause of MSA. A G51D SNCA mutation in British families was associated with autosomal dominant parkinsonism and neuropathologic findings comparable to both PD and MSA [92, 93], and a similar pathology was reported in a Finnish family with a novel αS mutation A53E [94]. The occurrence of glial cytoplasmic inclusion (GCI)-like oligodendroglial inclusions in familial PD due to SNCA mutations also suggests that both disorders form a continuum of αS pathology with related etiologies [95]. The same risk variants of the SNCA gene are also associated with risks for PD [96, 97], which indicates shared pathogenic mechanisms between these two synucleinopathies. On the other hand, there is little genetic evidence linking SNCA to MSA [98]. No SNCA mutations have been identified in true sporadic MSA, and no protein-changing Mendelian gene mutations have been identified in rare families [99]. Screening for PD causal genes (MAPT, PDYN, Parkin, PINK1, LRRK2) did not reveal any association with MSA [100–103], although MAPT H1 variation has been suggested to be associated with risk of MSA [104]. Contribution of LRRK2 exonic variants to susceptibility are under discussion [105, 106]. Gaucher-disease-associated glucocerebrosidase (GBA) variants were associated with MSA [107], but whether the GBA gene L444P mutation modifies the risk for MSA deserves further studies [108]. Among 108 autopsy-confirmed British MSA cases, one heterozygous GBA mutation (0.92%) versus 1.17% in controls was observed [109]. No association between other GBA mutations [110] nor with C9ORF expansions have been found [111, 112]. Mutations in the gene encoding the F-box only protein 7 (FBXO7) that immunochemically were detected in large proportions of αS positive inclusions (Lewy bodies (LBs), GCIs) were suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of synucleinopathies [113], but no pathogenic mutations in FBXO7 among PD and MSA patients of Japanese or other ethnicities were observed [114]. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-1031C) gene polymorphism was increased significantly in Japanese MSA patients compared with controls [115]. Other nucleotide polymorphisms (FBXO47, ELOVL7, and EDN1) were suggested as gene products, but none of the single polymorphisms reached genome-wide significance [116]. While rs75932628 triggering TREM2 was shown to increase the risk for AD, no association with the risk for MSA was observed [117]. A meta-analysis suggested that polymorphisms of the LINGO1 and LINGO2 (Nogo receptor-interacting protein-1 and – 2) decrease the risk of PD but not of MSA [118].

Other genes coding for apolipoprotein E, dopamine β-hydroxylase, ubiquitin, and leucine-rich kinase 2 showed no association with MSA [119], whereas polymorphism of several genes involved in inflammatory processes have been associated with elevated MSA risk, e.g., there was a fivefold risk to develop MSA with homozygosity for interleukin-1A allele, and the α-1-antichymotrypsin AA genotype (ACT-AA) is associated with an earlier onset and faster disease progression [120]. Another study showed association of MSA with polymorphisms of genes involved in oxidative stress [121]. A recent genome-wide study of a large MSA cohort and population-matched controls found an estimated heritability at 2.09–6.65%, which could be due to the presence of misdiagnosed cases in the cohorts and questions a common genetic background of MSA [87].

RNA analyses of MSA brain tissue have revealed alterations in a number of genes including α- and β-immunoglobuline [122], dysregulation of micro-RNAs (miRNA) resulting in downregulation of the carrier family SLC1A1 and SLC6, and dysregulation of miR-202 and miR-96 [123, 124]. miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression. miRNA expression profiles from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue revealed downregulation of miR-129-2-3p and miR-129-5p in the pons and cerebellum that was confirmed in frozen tissue from MSA patients [125]. Circulating miRNAs were differentially expressed [126]. Strand-specific RNA-sequencing analysis of MSA brain transcriptome showed disruption of long intervening non-coding RNAs (incRNAs) in the frontal cortex along with protein coding genes related to iron metabolism and immune response regulation indicating another level of complexity in transcriptional pathology of MSA [127, 128]. Analysis of the prion protein (PRNP) gene in MSA showed that the homozygous state of position 129 is not a risk factor for MSA and no other variants of the PRNP gene were associated with increased risk for MSA [100]. PRNP M129V homozygosity in MSA [129] was obviously not confirmed. However, other recent studies with MSA-derived αS aggregates have shown that they have a similar ability to undergo template-directed propagation, like PrP prions, and evidence is now emerging that αS aggregates can have different protein conformations, referred as strains, similar to what has been shown in prion disease [130]. These data suggest that αS becomes a prion in MSA, which supports its recent classification as a prion disease [13, 98], although there are challenges to the hypothesis that MSA is a prion disease.

A few epidemiological studies support the notion that epigenetic factors or environmental toxins may be associated with the risk of developing MSA [131, 132]. Due to limitations of environmental studies, there are no convincing data to correlate increased risk of MSA with occupational and daily habits such as exposure to solvents, pesticides, or other toxins like mercury or cyanide [133, 134]. An occupational story of farming related to higher MSA risk [134] could not be replicated [135–137]. Herbal medications have been shown to constitute an MSA risk factor for the Korean population [136]. A history of smoking was less frequent in MSA patients [138]. The association of alcohol consumption with MSA is under discussion [137]. Overall, no single occupational or environmental factor was shown to modify the disease risk.

In conclusion, all studies on the etiology of MSA suffer from limited numbers of cases as the disease is rare and frequently underdiagnosed, and differentiation from other parkinsonian syndromes is difficult, particularly in early disease stages. The definite diagnosis of MSA can only be made at postmortem examination, which, however, is missing in the majority of cases involved in genetic or epidemiological studies, contributing to their inconclusive results.

NEUROPATHOLOGY

Macroscopy

Naked eye inspection of the MSA brain may show mild diffuse cortical atrophy in the frontal lobes and significant atrophy of the cerebellum and pontine base. A few cases with severe frontal or temporal atrophy [139–141], and one case with asymmetrical temporal atrophy were reported [142]. Slicing the brain reveals atrophy and dark brownish discoloration of the posterolateral putamen due to deposition of lipofuscin, neuromelanin, and increased iron content in this area [143]. Pallor of substantia nigra (SN) and locus ceruleus (LC) are common, but without midbrain atrophy. MSA-C presents with various degrees of paleo- and neocerebellar atrophy, narrowing of the cerebellar folia, decrease and brown discoloration of the cerebellar white matter, the degeneration of which is more severe than of the cerebellar cortices [144]. The superior cerebellar peduncle and deep cerebellar nuclei are preserved. Severe atrophy of the pontine basis and middle cerebellar peduncle may be associated with reduction in size of the inferior olivary nucleus. The macroscopic changes in MSA-C cases may occasionally be difficult to distinguish from some spinocerebellar atrophias (SCA), especially SCA1 [145, 146].

Histopathology

The histological core features of MSA encompass four major types of different severity: (1) Specific αS immunoreactive inclusion pathology with four types of inclusions, i.e., GCIs within oligodendrocytes, also referred to as Papp-Lantos bodies [147], the presence of which is required for the postmortem diagnosis of definite MSA [7]. Less frequent are glial nuclear (GNI), neuronal cyotoplasmic (NCI), and neuronal nuclear inclusions (NNI), astroglial cytoplasmic inclusions and neuronal threads, also composed of αS [148]; (2) selective neuronal loss and axonal degeneration involving multiple regions of the nervous system with brunt on the striatonigral and OPC systems; (3) myelin degeneration with pallor and reduction in myelin basic protein (MBP), with accompanying astrogliosis; and (4) microglial activation [149]. GCIs and the resulting neurodegeneration occur in typical multisystemic distribution involving not only the striatonigral and OPC systems, but also autonomic nuclei of the brainstem (LC, nucleus raphe, dorsal vagal nuclei, etc.), spinal cord, sacral visceral pathways [132, 150, 151], and the peripheral nervous system [49, 152, 153], characterizing MSA as a multi-system/-organ disorder [86, 154, 155].

The degree of neuronal loss and cellular inclusions in different brain areas is related to the MSA motor subtype of SND and OPCA [156, 157]. Quantitative analyses of neuronal loss and GCI density showed a positive correlation between both lesions and an increase with disease duration [156, 158–160]. Region-specific astrogliosis is positively correlated with αS pathology in MSA in contrast to PD [161]. In general, the degree of astrogliosis parallels the severity of neurodegeneration [156]. Microglial activation in degenerating regions accompanies GCI pathology and is more abundant in white matter areas with mild to moderate demyelination [162]. In MSA-C, the cerebellar subcortical white matter and cerebellar brainstem projections are the earliest foci of αS pathology, followed by an involvement of other central nervous system (CNS) regions. The severity of GCIs correlated with demyelination, and loss of Purkinje cells increased with disease duration [163].

Inclusion pathology

The ultrastructure and biochemical composition of GCIs and other inclusions have been reviewed [4, 147, 149, 164–166]. Ultrastructurally, the GCIs are non-membrane bound cytoplasmic aggregates composed of loosely packed and coated or straight filaments 15–40 nm in diameter consisting of polymerized αS and filaments associated with granulated material related to cytoplasmic organelles such as mitochondria and secretory vesicles [167, 168]. NCIs consist of a meshwork of randomly arranged loosely packed granule-associated 18–28 nm filaments, similar to GCIs [167], while NNIs are composed of densely packed fibrillary structures forming bundles. Immuno-electron microscopy showed αS labelling of both granular and filamentous structures [169]. GCIs are characterized by aggregation of phosphorylated (Ser129) αS similar to LBs, forming the central core of the inclusion [147, 170]. In addition, they contain ubiquitin, and a number of other proteins such as tau, tubulin, heat shock, aggresomal and microtubule-associated proteins [171], synphilin, p25α (tubulin polymerization-promoting protein/TPPP, an OLG-specific phosphoprotein), oligodendroglial markers, p62 kinases, AMBRA1 (autophagy/beclin 1 regulator 1), MT-III metallothionein, etc. (see Table 1a,b). GCIs of MSA are both Campbell-Switzer- and Gallyas-Braak-positive, whereas LBs are negative for Gallyas-Braak stain [204]. Purification of αS containing inclusions revealed that GCIs consist of 11.9% αS, 2.8% α-β-crystallin, and 1.7% 14-3-3 protein compared to 8.5, 2.0 and 1.5% in LBs [205]. In early disease stages, diffuse αS staining in neuronal nuclei and cytoplasm occurs in many gray matter areas, suggesting that primary aggregation of nonfibrillary αS occurs in neurons [141]. In surviving striatal neurons as well as in GCI-containing oligodendrocytes of MSA patients, IRS-1pS312 staining was significantly increased, indicating their insulin resistance [206].

Table 1a.

List of protein constituents and their major functions identified in glial

| Protein identified by routine immunohistochemistry or mass spectrometry (MS+) | Main function / Cellular process | Reference |

| α-Synuclein (MS+) (Syn 202, 205, 215 > SNL-4 > LB509 > Syn 208), (S129-P, S87-P) | Presynaptic vesicle release | [173, 174] |

| β-Tubulin (MS+), α-Tubulin (MS+)b | Microtubule nucleation | [171] |

| HDAC6 (histone deacetylase 6)b | Tubulin degradation | |

| 20S proteasome subunitsb | ||

| p62/SQSTM1 (26 kDa protein/sequestosome 1)b | Autophagy | |

| 14-3-3 protein (in subset of GCIs) | Signal transduction | [175] |

| Elk1 | Transcription factor | [176] |

| Bcl-2 (MS+) | Apoptosis | |

| P39 | CDK5-activator | [177] |

| Carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme IIa (MS+) | ||

| cdk-5 (cyclin-dependent kinase 5) (MS+) | Cell cycle regulation | [178] |

| Midkinea | Neurotrophic factor | [179] |

| τ2 (reversible on exposure to detergent) | Microtubule-associated | [180, 181] |

| Isoform of 4-repeat tau protein (hypo-phosphorylated) (MS+) | Microtubule-associated | |

| DARPP32 | Regulation of signal transduction | [182] |

| Dorfin | Protein degradation | [183] |

| Heat shock proteins Hsc70, Hsp70b Hsp90b (MS+) | Protein folding | |

| DJ-1 | ||

| LRRK2 | [184] | |

| Rab5, Rabaptin-5 | Endocytosis regulation | [185] |

| Parkin | [184] | |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) | Signal transduction | [178] |

| NEDD-8 (MS+) | Protein degradation | |

| Other microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs): MAP-1A and -1B; MAP-2 isoform 1, and isoform 4 (all MS+) | ||

| Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (P13K) (MS+) | ||

| p25α/TPPP (MS+) (tubulin polymerization-promoting protein) | ||

| Septin-2, –3, –5, –6 and –9 | ||

| Synphilin-1 | αS interaction protein (SNCAIP) | [186] |

| Transferrina | ||

| HtrA2/Omi | Apoptosis | [187] |

| Ubiquitin (MS+) SUMO-1 (small ubiquitin modifier 1) | Protein degradation | |

| Leu-7a | [188] | |

| p62-co-localization with α-Syn (inconsistent) | [189] | |

| AMBRA1 | Autophagy regulation | |

| NBR1 - autophagic adapter protein | Autophagy | [190] |

| Metallothionein-III (MT-III) | Metal binding | [191] |

| α-β-Crystallin | Protein folding | [192] |

| NUB-1 (negative regulator of ubiquitin-like protein 1) | Negative regulation of NEDD8 | [193, 194] |

| Parkin co-regulated gene (PACRG) | Regulation of cell death | [195] |

| Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) | Protein folding | [196, 197] |

| F-box only protein 7 (FBXO7) | Ubiquitination | [198] |

| XIAP (x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein) | regulation of apoptosis | [199] |

Table 1b.

Candidate proteins that have so far eluded detection by routine immunohistochemistry

| Actin, γ-1, and γ-2 propeptides (MS+) |

| Amyloid-β precursor protein (MS+) |

| β-Synuclein (MS+) |

| Cytokeratin |

| Desmin |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (MS+) |

| Myelin basic protein (MBP)-3, –4, –5 (MS+) |

| Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), α- and β-isoforms (MS+) |

| Myosin (9 distinct isoforms) (MS+) |

| Neurofilaments (NF-3, NF-HC, NF-LC) (MS+) |

| Vimentin |

Distribution of lesions

GCIs occur in an anatomically selective manner and are widely distributed in cerebral gray and white matter, with highest densities in deeper laminae of motor cortex, dorsolateral putamen, globus pallidus, subthalamus, SNpc, pontine basal nuclei, motor nuclei of V, VII, and XII cranial nerves, pontomedullary reticular nuclei, cerebellum, intermediolateral column of the spinal cord, and preganglionic autonomic nerve structures [147]. In white matter, they are most numerous beneath the motor cortex, in external and internal capsule, corpus callosum, corticospinal tracts, and cerebellar white matter [207–209]. Accumulation of phosphorylated αS also occurs in subpial and periventricular astrocytes after long disease duration [210]. However, since αS-positive astrocytes in these regions also occur in LB disease, they may not be a specific feature of MSA [211]. Positive correlation between neuronal loss and the density of GCIs highlights their pivotal role for neuronal death [119, 166], while in the SN severe neuronal loss is associated with relatively low density of GCIs, indicating that certain areas are affected earlier in the disease course and have been burnt out [86]. Much less frequent are GNIs showing a similar distribution as GCIs, while the density of NCIs and NNIs is unrelated to that of GCIs [212]. NCIs seem to be more widespread than previously assumed and show a hierarchical pattern related with the duration of the disease, but independent of the pattern of neuronal destruction, suggesting that other factors may induce the subtype-dependent neuronal loss related to cognitive dysfunction [154].

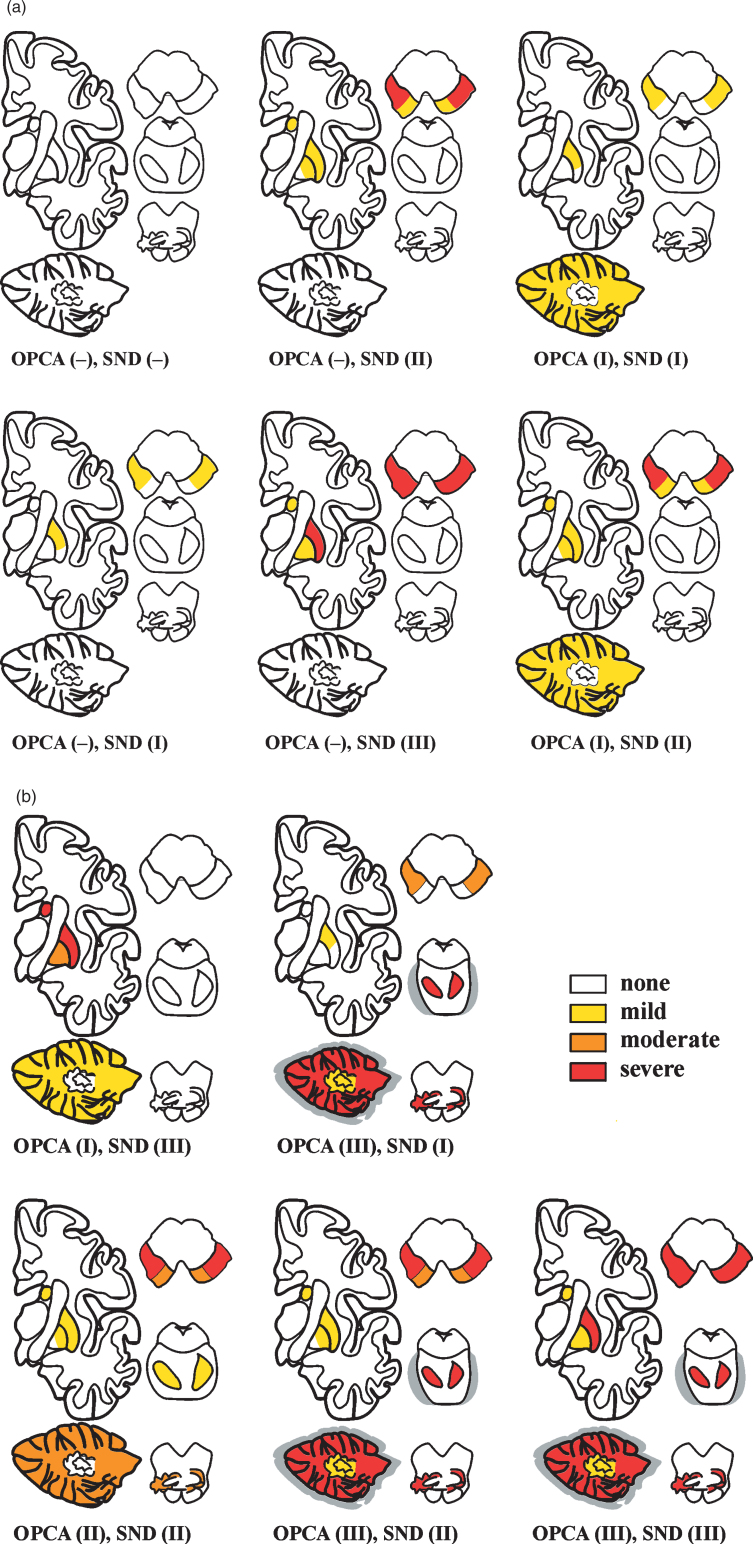

Based on semiquantitative assessment of GCI density, neuronal loss, and gliosis, the striatonigral and OPC lesions were graded into four degrees of severity indicated by an SND+ OPCA score and related to both clinical key features and disease duration [213] (see Fig. 1). While this grading scale revealed a low correlation between both systems and the natural history of the disorder, a similar system showed an overlap between them [158]. Stereological studies of the basal ganglia in MSA revealed a substantial loss of neurons in SN, putamen, and globus pallidus (p < 0.01) and to a lesser extent in caudate nucleus (p < 0.03). A lower number of oligodendrocytes was only observed in putamen (p < 0.04) and globus pallidus (p < 0.01), whereas the number of astrocytes was higher in putamen (p < 0.04) and caudate nucleus (p < 0.01). Higher numbers of microglia were found in all examined regions with greatest difference in the otherwise unaffected red nucleus (p < 0.01). These data support the region-specific patterns of pathological changes in MSA [214]. Another neuropathological study showed that the striatonigral region was most severely affected in 34%, the OPC in 17%, while in almost half the cases both regions were equally affected [156]. These data differ from Japanese studies, where OPC pathology was greatest in up to 40% and 18% showed predominant striatonigral damage, reflecting the different phenotypical presentations among populations [32, 215]. In view of the frequent overlap and mixed forms, the value of grading systems to determine the evolution of MSA is under discussion [86, 96].

Fig.1.

Schematic distribution of various combination types of SND and OPCA in 42 autopsy-proven cases of MSA (22 MS-P, 20 MS-C), showing different severity of morphological lesions (from [213]).

Neurodegeneration with cell loss and gliosis in MSA not only involves the striatonigral and OPC systems, but affects many other parts of the central, autonomic, and peripheral nervous system underpinning the multisystem character of the disease [4, 86, 149, 154]. Consistently and severely affected areas are putamen, caudate nuclei, SN, pontine and medullary tegmental nuclei, inferior olive, and cerebellar white matter; moderately affected are motor cortex and globus pallidus; and mild lesions occur in cingulate cortex, hypothalamus, nucleus basalis Meynert, thalamus, subthalamus, and pontine tegmentum [216]. The posterior putamen is involved in early disease stages [217].

Although cortical involvement in MSA was considered rare in earlier studies, more robust methods showed around 20% reduction of neurons in motor and supplementary motor cortex [218]. Early degeneration of the basal ganglia drives late onset cortical atrophy [219]. Betz cell loss and astrocytosis in cerebral cortex have been described in proven MSA cases [220–223], degeneration of frontal and temporal neocortices affects more lower laminae than upper ones [224]. Stereological studies found significantly fewer neurons in frontal and parietal cortex of MSA brains compared with controls and significantly more astrocytes and microglia in frontal, parietal, and temporal cortex, whereas no change in the total number of oligodendrocytes was seen in any of the neocortical regions [225]. This indicates that the involvement of the neocortex is more widespread than previously thought. Neocortical neuronal loss was significantly more severe in MSA patients with impaired executive function and cognitive impairment [225–228], while recent MRI studies, although showing widespread cortical, subcortical, and white matter alterations, suggested only a marginal contribution of cortical pathology to cognitive deficits but more impact of focal fronto-striatal degeneration [229]. The presence of LB-like inclusions in neocortex [154], of frequent globular NCIs in the medial temporal region [230, 381] and in the perirhinal cortex without hippocampal involvement [231] were associated with cognitive or behavioral impairment, while others found no pathological differences between MSA cases with and without cognitive changes [232]. Although volumetric MRI analysis suggested hippocampal atrophy in MSA, little information on neuronal loss in hippocampus is available. Recent studies suggested that a greater burden of NCIs in the limbic regions is associated with CI in MSA [233].

Reduced neuronal numbers in the anterior olfactory nucleus and intrabulbar part of the primary olfactory (pyriform) cortex may underlay olfactory dysfunction in MSA [234], although this is less pronounced than in PD. Progressive retinal ganglion cell loss has been observed in MSA, both in vivo and by neuropathologic assessment [235–237]. More relative preservation of the temporal sector of the retinal nerve fiber layer and less severe atrophy of the macular ganglion cell layer complex, due to damaged large myelinated optic nerve fibers, differ from that in PD [238]. Retinal thinning worsens with disease progression and severity [235].

Demyelination and gliosis

Demyelination with variable intensity is frequent in MSA and mainly involves the striatonigral and OPC region, the external capsule and cerebellar white matter [162], in MSA-C the frontal and occipital white matter [239]. These changes are detected during lifetime by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) MRI [240, 241], specifically in putamen and middle cerebellar peduncle [242–245], but no portion of the nervous system appears to be spared [144]. Demyelination is associated with reduction in myelin proteins including sphingomyelin, sulfatide, and galactoceramide by about 50% [246]. Whether myelin loss is a secondary event attributable to neuronal loss or a primary lesion, which in turn leads to neuronal and axonal loss, is unknown, but it also may be related to oligodendroglial dysfunction. Loss of oligodendroglial TPPP/p25α immunoreactivity correlated significantly with the degree of microglial reaction and loss of MBP density as a marker of tract degeneration [15]. White matter degeneration causes destruction of neuronal loops, leading to dysfunction of the whole-brain network [247], and may be related to disorders of cerebral autoregulation [248].

Gliosis is invariably described in the degenerating areas of MSA brain [156, 249]. In general, the degree of region-specific astrogliosis parallels the severity of neurodegeneration and correlates positively with αS pathology in MSA [162, 250] in contrast to PD [251]. Significantly increased monoaminoxidase B (MAO-B), a biomarker of astrogliosis, in degenerating putamen (+83%), was associated with astrogliosis, and positive correlation with αS accumulation, while less severe increase of MAO-B in SN (+10%) was positively related with that of membrane-bound αS. MAO-A decreased moderately only in atrophic MSA putamen (–27%) and was not changed in SN in PD, thus distinguishing astrocyte behavior in these disorders [252].

Microglial activation, accompanying αS pathology and phagocytosing degenerating myelin, is prominent in degenerating regions (putamen, pallidum, SN, pons, and prefrontal cortex) [253], in particular in white matter tracts that provide input to the cerebellum and extrapyramidal system [162, 254]. It can be visualized both histologically [254] and by in vivo PET imaging [255]. Activation of TRL4 and myeloperoxidase, a key enzyme for the production of reactive oxygen species in phagocytic cells, has been reported in activated MSA microglia [256–258]. A trend of increased M1 compared to M2 activation, identified by co-localization of TSPO with CD68 immunoreactivity [259], suggests that microglial activation is at least in part determined by oligodendroglial GCIs in affected areas. Stereological studies in the white matter revealed a significant increase of microglia (∼100%) without concomitant astrogliosis and absence of significant oligodendroglial degeneration [260]. In summary, there is evidence that microglia cells play an important role in the initiation of progression of MSA like in other neurodegenerative diseases [261, 262]. This is supported by transgenic mouse models indicating an active contribution of microglial activation to pathogenesis of the disease [263] by triggering neuroinflammatory responses in the MSA brain [264].

Lesions of the autonomic and peripheral neuronal system

Degenerative involvement of preganglionic autonomic neurons of the brainstem and spinal cord underlies the multidomain autonomic failure in MSA [49, 151, 265, 266]. The supraspinal lesion sites include the cholinergic neurons of the ventrolateral nucleus ambiguus [267, 268], pedunculo-pontine/laterodorsal tegmental nuclei [269], ventral periaqueductal DAergic neurons, which may contribute to excessive daytime sleepiness [270], the medullary arcuate nucleus [271], the noradrenergic LC [157], the serotonergic medullary groups (nucleus raphe magnus, obscurus, and pallidus) and ventrolateral medulla [53, 272], ventromedullary neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptor immunoreactive neurons [273], the caudal raphe neurons with sparing of the rostral part [274, 275], the catecholaminergic neurons of the rostral ventrolateral medulla (C1 group), and noradrenergic neurons of the caudal ventrolateral medulla (A1 group) [267, 276]. Loss of A5 noradrenergic neurons was comparable to that in LC and pontine tegmentum [277]. The medullary catecholaminergic and serotonergic systems are involved even in the early stages of MSA, and dysfunction of the medullary serotonergic system could be responsible for sudden death [278]. Further involved areas are the dorsal vagal nucleus [267], the periaqueductal gray [150, 279], the Edinger-Westphal nucleus and posterior hypothalamus [280] including the histaminergic tuberomamillary neurons [281], the tuberomammillary nucleus [280, 282], and suprachiasmatic nucleus [267]. Affected is also the ponto-medullary reticular formation [160, 283], while the branchimotor neurons of the nucleus ambiguus are preserved [284]. Adrenergic neurons are more susceptible than serotonergic neurons. The density of αS did not correlate with neuronal loss (ranging from 47 to 70%) in any of these medullary areas and there was no correlation between αS burden and disease duration for any regions of interest, indicating that loss of monoaminergic neurons may progress independently from αS accumulation [285]. Mild degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerves can occur in MSA, which accounts for mild to moderate decrease in the numbers of tyrosine hydroxylase but not of neurofilament-immunoreactive nerve fibers in the epicardium and for the slight decrease in cardiac uptake of 123Imetaiodobenzylguanidine (123IMIBG) by SPECT assessing postganglionic presynaptic nerve endings. However, depletion of cardiac sympathetic nerve is closely related to the presence of αS pathology in the sympathetic ganglia of the CNS [208, 286]. At lower levels of the autonomous nervous system lesions involve sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the intermediolateral cell column of the thoracolumbar spinal cord [157, 287], sympathetic ganglia, and Schwann cells in autonomic nerves [211]. Spinal cord pathology is further characterized by neuronal loss in the Onuf’s nucleus in the lumbosacral region [157, 288], and minor or rarely severe loss of upper and lower motor neurons [289, 290], while the involvement of anterior horn cells is under discussion [157, 291].

Involvement of the peripheral nervous system in MSA includes αS aggregates in sympathetic ganglia, skin nerve fibers [292, 293], and Schwann cells [293a], contrasting with axonal predominance of αS pathology in DLB [293b] which have also been described in MSA models but without functional deficits [153]. However, others showed lack of phosphorylated αS immunoreactivity in dermal fibers in contrast to PD [293, 294]. Filamentous aggregations of αS were found in the cytoplasm of Schwann cells in cranial, spinal, and autonomic nerves in MSA [49, 211, 295], and reduced sudomotor nerve density suggests pre- and postganglionic denervation [296, 296a].

αS pathology has been reported in the enteric nervous system [297].

Iron in MSA

Iron depositions in the putamen of MSA patients are a hallmark of the disease [298]. Unfortunately, there is unsatisfactory data about alterations of iron metabolism in MSA and the relevance of iron in the pathogenesis of this disorder. However, there is recent evidence of iron deficiency due to iron dysregulation in MSA indicating a deficit in bioavailable iron in MSA [299], whereas iron accumulation in MSA-P may be an epiphenomenon of the degenerative process [300]. To the best of our knowledge, no proteomic study of light chain ferritin levels have been performed in MSA, as in corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) [301]. Iron can convert native αS into a β-sheet conformation and promotes/accelerates its aggregation either directly or via increasing levels of oxidative stress. Interestingly, αS has been identified to have a ferrireductase activity and an iron-regulated element on mRNA level, implying a direct interaction between iron and αS [302].

Postmortem analyses have revealed increased iron content and associated neuronal loss particularly in the putamen of MSA, while others observed it also in the SN, globus pallidus, and caudate nucleus of MSA patients [298, 303–306]. Although severe neuronal loss in LC was described, alterations in iron concentration have not been documented there [307]. There is evidence that iron content (Fe3 +) in globus pallidus and SN is more pronounced in MSA than in PD, DLB, and controls, being similar to the levels found in PSP [257, 307].

However, reduction in bioavailable iron was shown recently in MSA by a detailed postmortem analyses of human brain tissue (MSA, PD, and control) assessing iron, ferritin, transferrin receptor (TfR) and ferroportin distribution in pons, putamen, and SN [299]. In MSA, there are increased ferritin levels in pons (2.5-fold) and putamen (4.5-fold), an increase in iron stored within ferritin (2-fold) in pons and activated microglial cells with intense ferritin staining in SN and pons. Interestingly, the transporter ferroportin was decreased in MSA pons and putamen (0.75) in contrast to upregulation of ferroportin in SN in PD. Co-localization analyses of pons revealed selective expression of ferroportin in neurons and the Golgi apparatus which was observed in a filiform manner around the nucleus in PD and controls, while in MSA pons the ferroportin signal was weaker and more diffusely distributed—a pattern which is also seen in SN of PD patients. TfR expression was unchanged in pons and SN in PD, MSA, and controls, while putamen showed decreased TfR expression in PD compared to controls and MSA. The results of this study suggest that neurodegeneration is accompanied by region-specific differences in iron dysregulation which might be regarded as disease specific patterns in MSA, where limited iron export coupled with an increase in ferritin iron load results in decreased bioavailability of iron in MSA pons [302]. A dysregulation of iron export coupled with an increase in ferritin iron was detected to a lesser extent also in putamen. Although it is still unclear whether iron accumulation is rather a consequence and secondary event in the cascade of neuronal degeneration than a primary cause. Correlating the severity of putamen atrophy and iron accumulation suggests that iron accumulation is a secondary effect of neurodegeneration as significantly increased iron in the putamen is associated with advanced atrophy compared to moderate iron accumulation in globus pallidus along with less severe atrophy [302].

Subtypes of MSA

Pathological and clinical studies have shown that MSA has a wider range of presentations than previously thought, which expands the list of differential diagnoses. Several subtypes of MSA do not fit into the current classification [308]:

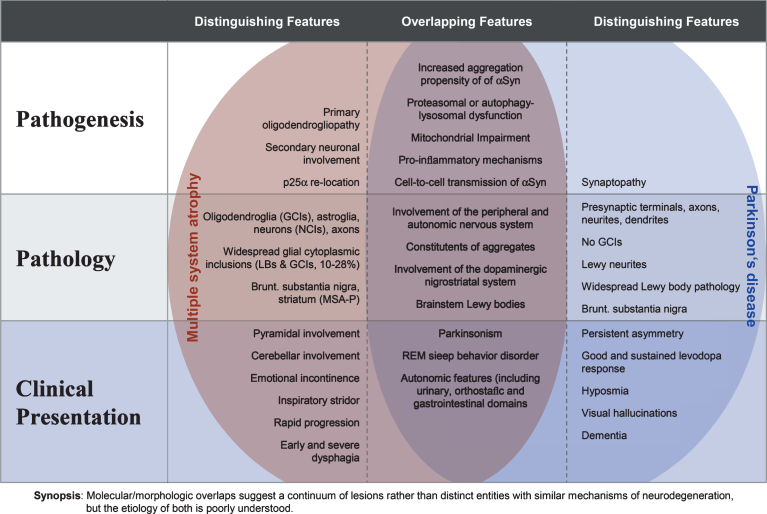

“Minimal change” MSA-P is a rare aggressive form with GCIs and neurodegeneration almost restricted to SN and putamen, thus representing “pure” SND [309–312], suggesting that GCI formation is an early event and may be responsible for some of the clinical symptoms of MSA. One patient with “minimal” MSA-C showed widespread GCIs with NCIs and NNIs restricted to pontine basis, cerebellar vermis and inferior olivary nuclei, associated with neuronal loss indicating a common link between both lesions in early stages of the disease [313]. Co-existence of “minimal changes” MSA with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease was reported in a 64-year-old Spanish woman [314]. Postmortem detection of MSA pathology in neurologically normal individuals (prodromal/preclinical MSA) with GCIs limited to the pons and inferior olivary nuclei and mild neuronal loss restricted to SN is extremely rare [315, 316], suggesting that this region may be afflicted first in MSA-P. The presence of GCIs may represent an age-related phenomenon not necessarily processing to overt clinical disease, classifying these cases as “incidental MSA” similar to incidental Lewy body disease [317]. The other extreme are “benign” MSA cases with prolonged survival up to 15 years or more in 2-3% of MSA patients [43, 318]. Most of them showed a slowly progressing parkinsonism resembling PD in the first 10 years of disease with subsequent rapid deterioration after development of autonomic failure, before which correct diagnosis was difficult. Late onset of both cardiovascular autonomic and urinary voiding disorders were suggested to be responsible for prolonged survival in MSA irrespective of its subtype [319]. Many of these patients developed motor fluctuations and levodopa-induced choreiform dyskinesias, which would have indicated deep brain stimulation, not recommended for MSA patients [320, 321]. These rare long surviving patients with MSA-P were considered “benign” forms [43], whereas other cases with clinical course of 18 years revealed extensive distribution of GCIs in CNS [322]. A non-motor variant of pathologically confirmed MSA showed neither parkinsonism nor cerebellar symptoms [323]. Overlapping and distinguishing features of MSA and PD are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig.2.

Overlapping and distinguishing features of MSA and PD at the pathogenic, neuropathologic and clinical level (modified from [22]).

An atypical form of MSA with abundant αS inclusions was identified as frontotemporal lobe degeneration with αS (FTLD-synuclein) in the presence of SND and variable OPC degeneration, but in the absence of autonomic dysfunction [324, 325]. Another case of an MSA-P phenotype due to FTLD-TDP type A with severe striatal degeneration and mild cerebellar involvement was described recently [326]. Rare cases with pathologic hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72, a gene linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and FTLD, demonstrated clinical and neuroimaging features indistinguishable from MSA [327]. A rare cerebello-brainstem-dominant form of x-linked adrenoleukodystrophy should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of MSA [328]. These and other subtypes should be considered in establishing a correct diagnosis early in the course of MSA, which has implications for prognosis, selection of treatment and counseling of patients and their families.

Concomitant pathologies

Like other neurodegenerative disorders, many of which occurring in advanced age, various diseases are occasionally associated with MSA. The presence of LBs, the hallmark of PD and DLB, in MSA ranged from 10 to 23% [86, 329], whereas in Japanese MSA cases no concomitant Lewy pathology was found [215]. Extremely rare association of early stage MSA (striatonigral degeneration) with widespread LBs, referred to as “transitional variant” of PD and MSA [330], is of unknown significance. A synucleinopathy with features of both MSA and DLB was described [331]. Concomitant Alzheimer-like lesions in MSA are less frequent than in age-matched controls, mainly observed in old age [329], although recently MSA was reported in a male aged 69 years with pre-existing AD [332]. Studies of 139 MSA cases revealed chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) pathology in 6% and aging-related tau astrogliopathy pathology [332a] in 8%. Since seven of 8 MSA/CTE cases had low Braak NFT stages (≤ III), age-related tau pathology would not be expected to make CTE pathology, and a small subset of these individuals had no history of contact sports or head trauma [333]. TDP-43 pathology, frequently observed in old brains, AD, certain forms of FTLD, and motor neuron disease [158], is generally rare in MSA, predominantly located in medio-temporal lobe and subcortical brain areas, suggested to represent an age-related “incidental” phenomenon [6], and no fused in sarcoma lesions were found in MSA brain [334]. An infantile MSA case linked to neuronal intranuclear myelin inclusion disease [335] appears questionable. Co-occurrence of MSA and PSP is very rare, with only four cases being reported in the literature [336]. The frequency of argyrophilic grains, a 4-repeat tauopathy, of approximately 20% in a Japanese MSA series [337], was similar to that reported in PSP [338]. The presence of unusual tau-positive cytoplasmic inclusions in astroglia of a few MSA brains, not co-localized with αS positive GCIs, suggested that tau may be related to a degenerative pathway different from that induced by αS [339]. The relevance of tau-positive (more 4-R than 3-R tau) inclusions in the astroglia in a single MSA brain [340] is unknown, although an interaction between different pathological proteins in neurodegenerative disorders suggests shared common pathogenic mechanisms [341–346].

There is still an open debate whether multiple sclerosis can cause parkinsonian symptoms or the co-existence of both diseases is accidental [347]. So far, only 45 cases of co-occurring parkinsonism and MSA have been reported, but CSF αS data are lacking [347, 348]. The association of MSA and multiple sclerosis has been reported only in two cases based on clinico-radiological and/or CSF findings [349, 350]. Despite essential differences in the neuropathology and etiopathogenesis of MSA and multiple sclerosis, and their rare co-occurrence, there is multiple pathogenic overlap between both disorders with similar basic mechanisms, resulting in chronic degeneration [155].

Clinical presentation

Parkinsonism, with rigidity, slowness of movements, postural instability, gait disability, and tendency to fall, characterizes the poorly levodopa-responsive motor presentation of MSA-P [23]. The motor findings are rarely asymmetrical [351]. Rest tremor is rare, whereas irregular postural and action tremor may occur [352, 353]. Cerebellar ataxia, wide-based gait, uncoordinated limb movements, action tremor, downbeat nystagmus, and hypometric saccades predominate in MSA-C [354]. Hyperreflexia and a Babinski sign may occur in 30–50% of patients, while abnormal postures, such as bent spine, antecollis, and hand or foot dystonia are rare [354]. Dysphonia, repeated falls, drooling, dysphagia, dystonia, and pain occur in advanced stages of the disease [355]. Spinal myoclonus in a MSA-C patient was caused by αS deposition in spinal cord [356]. Among non-motor symptoms, observed in 75–95% of patients [357], autonomic failure, in particular urogenital (urinary incontinence, impaired M. detrusor contractibility) and cardiovascular disorders, are frequent early features of MSA, but are not specific for this disease [353, 358, 359]. On the other hand, autonomic dysfunction may be the only presenting feature in some MSA patients [360]. Severe orthostatic hypotension is the main symptom of cardiovascular autonomic failure, often manifested as recurrent syncope, dizziness, nausea, headache, and weakness, but it is also seen in many other conditions [361]. Cardiovascular autonomic failure associated with degeneration of the nucleus ambiguus has been reproduced in the MSA mouse model [268]. Orthostatic hypotension usually occurs after the onset of genitourinary symptoms. Other non-motor features include constipation (in one third of the patients), vasomotor failure with diminished sweating (hypohydrosis) [362, 363], pupillomotor abnormalities and oculomotor dysfunctions [364]. Excessive daytime sleepiness shows a frequency similar to that encountered in PD [365, 366], and a similar frequency in Caucasian and Japanese MSA patients [367]. Gender differences were apparent for depression (women > men) and early autonomic failure (men > women) [357]. The prevalence of REM sleep behavior disorder, often preceding the onset of the motor disorders, is 88% or more [368, 369]. Restless legs syndrome is more prevalent in MSA as compared to the general population [370]. Respiratory disturbances including diurnal or nocturnal inspiratory stridor and sleep apnea are frequent and may occur together [371, 372], the latter representing a major cause of death in MSA [373, 374]. Reduced orexin (associated with sleep apnea syndrome) immunoreactivity has been observed in the nucleus basalis of Meynert in MSA [375].

Dementia and visual hallucinations, characteristic for DLB, are rare symptoms of MSA [9], although mild cognitive impairment [376, 377] and frontal-lobe dysfunction with attention and execution deficits or emotional incontinence driven by focal striatofrontal degeneration [229] do occur. Emotional and behavioral changes, including depression, anxiety, and panic attacks affect about one-third of MSA patients [354, 378, 379]. Applying the Movement Disorder Society diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease-dementia, 11.7% of MSA patients were demented on level-2 examinations, executive dysfunction was seen in 52%, memory impairment in 15%, and language and visuospatial dysfunctions in 14% and 13%, respectively [380]. MSA-P and MSA-C were suggested to have different cognitive and mood profiles [381]. Cognitive deficits correlate with frontal atrophy and disease duration [382]. MSA is featured by a relentless worsening of the motor and non-motor symptoms, with more rapid progress at the onset [31]. The causes of death usually include (aspiration) bronchopneumonia, suffocation, or sudden death [31]. Older age at onset and early severe autonomic failure are negative prognostic factors, whereas a cerebellar phenotype and later onset of autonomic failure predict slower disease progression [1, 46, 52]. Because of its protean manifestations, MSA can be misdiagnosed, or disorders with other etiologies and pathologies can mimic MSA, especially at disease onset, as shown by a retrospective autopsy study in a cohort of patients with the clinical diagnosis of MSA, where only 62% were confirmed at autopsy [19]. Autonomic failure may be indistinguishable from pure autonomic failure or parkinsonism with autonomic failure. MSA-C patients presenting with late-onset cerebellar ataxia and additional autonomic failure can mimic genetic, toxic, or immune-mediated ataxias, spinocerebellar ataxia, or late-onset Friedreich’s ataxia [247]. MSA-C can be misdiagnosed as sporadic adult-onset cerebellar ataxia [383]. Conversely, patients with sporadic adult-onset cerebellar ataxia can be misdiagnosed as having MSA, when they develop urinary dysfunction or orthostatic hypotension [17]. SCAs, a group of autosomal dominant genetic disorders, is characterized by progressive degeneration of the cerebellum and its efferent and afferent connections, but a significant proportion of these patients have apparently sporadic cerebellar ataxia [384–386]. Some SCAs (2, 3, 6, and 17) may develop parkinsonism with nigrostriatal degeneration [387, 388], sometimes even without cerebellar dysfunction. They can be misdiagnosed as MSA-P when accompanied by autonomic failure, while others may mimic MSA-C [389]. A family with SCA1 triplet repeat expression and MSA-C-like clinical presentation [146] at postmortem showed multilocal neurodegeneration and sparse argyrophilic inclusions positive for tau and ubiquitin; but since αS immunochemistry was unavailable at that time, a definite diagnosis of MSA could not be made. SCA3 gene variants may also act as susceptibility factors for the development of MSA-C [390], whereas SCA6 is not commonly associated with MSA [120]. A prospective evaluation of 1,500 patients with progressive cerebellar ataxia identified 11% MSA-C cases [391]. Therefore, genetic testing for SCAs should be included in the diagnostic workup for MSA [392]. Other genetic disorders which can clinically mimic MSA include fragile X-associated ataxia syndrome, Perry syndrome, and other autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias [18, 393, 394]. However, fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome is rare in MSA [395]. The accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of MSA is still unsatisfactory with a positive predictive value even in the later stages ranging from 60 to 90% [19, 396, 397], but the true rate of over- or under-diagnosis of MSA is not known. Various disorders which may mimic an MSA phenotype have been revised recently [23].

CLINICAL DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

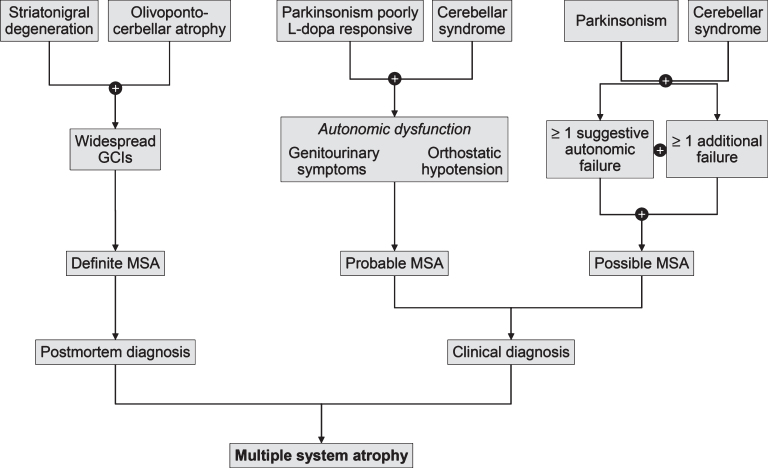

Revised consensus guidelines define 3 degrees of certainty of the clinical diagnosis of MSA: definite, probable, and possible [9] (Fig. 3).

Fig.3.

Diagnostic scheme for MSA according to the current consensus diagnostic criteria.

Definite MSA requires postmortem evidence of widespread αS-positive inclusions with concomitant SND or OPCA [7].

Probable MSA is defined as a sporadic, progressive disorder in adults, clinically characterized by severe autonomic failure, involve urinary dysfunction and poorly levodopa-responsive parkinsonism or cerebellar ataxia.

Possible MSA can be diagnosed, when a sporadic, progressive adult-onset disorder with parkinsonism or cerebellar ataxia is accompanied by at least one of the additional features suggesting autonomic or urogenital dysfunction plus one other clinical or neuroimaging abnormality. Recognition of patients with early or possible MSA may be supported by including one or more “red flags” (warning signs); two or more out of six red flags had a specificity of 98.3% and a sensitivity of 84.2% [353, 354]. Recent studies confirmed the validity and reliability of an eight-item pilot scale for the assessment of early MSA symptoms [398].

The revised consensus criteria regard dementia as a non-supportive feature of MSA [9]. However, recent evidence suggests that dementia occurs in up to 31% of MSA patients [399–401], indicating that the diagnosis of MSA cannot be excluded by the presence of dementia, although the molecular and structural correlates of cognitive decline are still unclear [232, 233, 400].

Biomarkers

No reliable diagnostic and prognostic fluid biomarkers are currently available, although many studies suggest that a combination of CSF biomarkers, such as DJ-1, phospho-tau, light chain neurofilament protein, and Aβ42 may be helpful in the differential diagnosis between MSA and other parkinsonian disorders [6, 402]. Oxidized DJ-1 protein levels in erythrocytes can be used as a marker for the differential diagnosis of PD and MSA [403]. The results of proteomics for biomarker discovery and miRNA expression need further evaluation [400a]. As cardiac sympathetic postganglionic denervation distinguishes PD from MSA patients showing intact innervation, 123IMIBG scan can help differentiation of the two disorders with a pooled specificity of 77% (95%, CI: 68–84%) [404]. Despite some overlap with PD (reduced 123IMIBG uptake), the presence of normal or only mildly reduced tracer uptake, supports the diagnosis of MSA-P [405, 406]. In patients with isolated autonomic failure, 123IMIBG myocardial scintigraphy may be a valuable predictor of conversion to MSA [407]. However, several interactions limit the value of this method [408]. Odor identification tests showing severe loss of smell may exclude MSA [409], separating PD from MSA with a sensitivity of 76.7% and a specificity of 95.7% [410].

MRI abnormalities including the “hot-cross bun” sign, a cruciform hyperintensity in the pons [411] and the “putaminal rim sign” that marks hyperintensity bordering the dorsolateral margin of the putamen in T2-weighted MRI reflecting degeneration and iron (Fe3 +) deposition may differentiate MSA-P from PD [412–417]. They are, however, non-specific signs and, therefore, not included in the recent consensus criteria [9], while putaminal atrophy shows 92.3% specificity but low sensitivity (44.4%) for distinguishing MSA-P from PD [418]. The combination of “swallow-tail” sign and putaminal hypointensity can increase the accuracy of discrimination between MSA and idiopathic PD [419]. Others showed significantly increased putaminal MD (mean diffusivity) volumes in the small anterior region of interest in MSA-P versus PD [420]. Another key distinguishing feature is the extensive and widespread volume loss across the entire brain in MSA-P, which is not seen in PD [421]. In quantitative MRI studies, the bilateral R2* increase in putamen best separated MSA-P patients from PD [422], consistent with susceptibility weighted imaging results demonstrating higher iron deposition in putamen versus PD [423]. DTI allows differentiation between PD and MSA-P, the latter showing higher values of the apparent diffusion coefficient in the inner capsule, corona radiata, and lateral periputaminal white matter [424] and other pathological differences between MSA-P and PD [425]. Combined use of diffusion ratios, magnetic susceptibility values/quantitative susceptibility mapping allowed differentiation of MSA-P and MSA-C from other parkinsonian syndromes, with sensitivities and specificities of 81–100% [425a]. The relevance of non-specific MRI features in MSA has been critically reviewed recently [426]. Abnormalities in left anterior thalamic radiation and bilateral corticospinal tract are specific for MSA in relation to PD and controls [427]. Elevated putaminal apparent diffusion coefficient and 123IMIBG tests are also useful for differentiation between MSA and PD [428]. FDG-PET can distinguish MSA-P from PD by showing different patterns of decreased glucose metabolism with a specific positive predicting value of 97% [429]. For autonomic function testing, symptomatic causes have to be excluded before attributing them to MCA. Imaging of presymptomatic DAergic functions using 123Iβ-CIT SPECT may not satisfactorily separate MSA from PD, whereas DAD2 receptor ligands that target postsynaptic DAergic functions differentiate PD (normal or increased signal) from MSA (reduced signal) [240]. Dopamine transporter (DaT) imaging showed more prominent and earlier DaT loss in anterior caudate and ventral putamen in MSA than in PD [430, 431], although normal DaT imaging does not exclude MSA [432]. In autopsy-confirmed cases a greater asymmetry of striatal binding was seen in MSA than in PD [433], but it is highly correlated with postmortem SN cell loss [434]. 18F-dopa PET showed more widespread basal ganglia dysfunction in MSA than in PD without evidence of early compensatory increase in Dopa uptake [435]. Ancillary investigations for MSA have been summarized recently [1, 23, 436, 437]. The diagnostic validity of skin punch biopsies for the demonstration of αS deposits in Schwann or other cells in peripheral nerves in MSA patients is under discussion and needs further evaluation in pathologically confirmed cases [210, 292, 293].

PATHOGENESIS

General mechanisms

Although our understanding of MSA remains incomplete, evidence from animal models and human postmortem studies indicate that the accumulation of misfolded αS, particularly in oligodendroglia, plays an essential role in the disease process [155, 164, 443]. MSA is currently considered a synucleinopathy with specific (oligodendro-) glioneuronal degeneration, associated with early myelin dysfunction and neuronal degeneration related to retrograde axonal disease [8, 444, 445]. Although it is tempting to speculate that primary neuronal pathology leads to secondary oligodendroglial degeneration as suggested by the finding that NCIs are more widespread than previously assumed and exist in areas lacking GCIs [154], the robust observation that distribution and severity of neurodegeneration reflect subregional GCI densities supports the assumption that MSA is a primary oligodendrogliopathy [15, 164, 166]. The causative role of GCI pathology in introduction of the neurodegenerative process was confirmed experimentally in transgenic mice overexpressing human αS in oligodendrocytes [446–449].

The selectivity of the neurodegeneration in MSA is determined by the concerted interaction of multiple noxious factors, among them ectopic αS accumulation in oligodendrocytes, “prion-like” propagation of misfolded αS, proteasomal and mitochondrial dysfunction [8, 124], dysregulation of myelin lipids [246, 450], genetic polymorphism [118, 121], microglial activation [257], neuroinflammation [261, 451], proteolytic disturbance, autophagy [191]. and other factors contributing to oxidative stress, which is suggested to be a major pathogenic factor in MSA and related diseases [452, 453]. This suggests a multi-mechanistic hypothesis of the etiopathogenesis of MSA [454].

α-Synuclein and prions

αS, a heat stable cytosolic protein, primarily located in presynaptic nerve terminals, when present in oligodendrocytes in human MSA and transgenic models, has undergone post-translational modification (oxidation, phosphorylation, nitration, etc.) enhanced by oxidative stress [455, 456]. αS in GCIs is phosphorylated at residue Ser-129 and ubiquitinated like in LBs in PD and DLB [457–459].

Biochemical studies revealed a significant accumulation of membrane-associated αS in affected regions of MSA brains containing both neuronal and glial inclusions [251], but most of the soluble αS was also present in areas with few GCIs, suggesting that altered solubility precedes the formation of GCIs and that an increase in soluble monomeric αS could result in a conversion into abnormal insoluble, filamentous aggregations. Various levels of αS isoforms were seen, 140 and 112 isoforms as well as aggregation-prone synphilin-A and parkin isoforms being significantly increased, whereas αS 126 was decreased [460]. These changes of isoform expression profiles suggest alterations in regulation of transcriptions and in protein-protein interactions that may be important in protein aggregation processes being key pathways in the pathogenesis of MSA [460]. The toxicity of αS in its different forms is still undecided, with some reporting a cytoprotective function of αS aggregation in insoluble deposits [461, 462], while others suggest that oligomeric αS is the most toxic form of the protein [463–465].

The source of αS in GCIs and the role of many protein components are enigmatic, although GCIs express αS mitochondrial RNA (mRNA) [466]. Widespread mRNA dysregulation in MSA has been recapitulated in murine models [124]. A number of studies indicates that αS oligomers are released by neurons and taken up by surrounding oligodendrocytes to form GCIs [467]. Incubation of recombinant αS with an oligodendrocyte cell line demonstrated its ability to take up and to accumulate αS into GCI-like structures [459]. SNCA transcripts identified in oligodendrocyte lienage cells may not be the origin of αS in GCIs and MSA [6]. Accumulation of αS in oligodendrocytes induces their dysfunction resulting in reduced trophic support and demyelination shown in the MBP-h/αS mouse model [468, 469]. The leading role of GCI pathology is supported by the “minimal change” (MC-MSA) forms, where severe GCI burden is associated with less severe neuronal loss but shorter disease duration [312].

Changes in MBP levels in MSA brain suggest myelin lipid dysfunction [246, 469, 470], which together with aberration in protein distribution may lead to myelin deficit [471], a crucial pathomechanism in MSA [172]. Elevated matrix metalloproteinase activity may also contribute to the disease process by promoting blood-brain barrier dysfunction and myelin degeneration [472]. Oligodendroglial dysfunction supports the notion that neurodegeneration may occur secondary to demyelination and lack of trophic support by GCI-bearing oligodendroglia [232], but the causative mechanisms of demyelination are not yet fully understood. The temporal evolution of αS pathology in PD [473] and postmortem demonstration of αS inclusions within grafted fetal neurons transplanted into PD brains [474–476] suggested that spreading/propagation of pathological αS species is a mechanism underlying disease progression in α-synucleinopathies [459, 477]. Evidence from human studies, cell culture and animal models has strengthened the concept that pathology arising from neurodegeneration-related proteins such as αS, amyloid-β, and tau, may propagate in a “prion-like” fashion [478, 479]. On the other hand, the prion hypothesis of selective neuronal vulnerability may be another important factor contributing to specific patterns of neurodegeneration [480]. Increasing evidence supports the notion that αS, which is primarily generated by neurons, can be toxic once released to the extracellular environment [481, 482]. It can then propagate to other neurons or glia and to other functionally connected networks in a “prion-like” fashion [16, 483–486]. Propagation and accumulation of αS in glial cells could lead to activation of these cells and subsequent neuroinflammation [261, 487, 488]. Progressive neurodegeneration in MSA results from αS protein misfolding into a self-templating prion confirmation that spreads throughout the brain [491]. Neuroinflammation may also favor the formation of intracellular αS aggregates as a consequence of cytokine release and the shift to a non-inflammatory environment [441]. Pathogenic mechanisms leading to elevated αS levels in neurons underlie neuronal secretion and subsequent uptake of αS by oligodendrocytes [489]. Homogenates containing αS derived from brain biopsy samples from MSA patients triggered aggregates of phosphorylated αS and a neurodegenerative cascade in mice that was compatible with human MSA pathology [130, 490]. Current data indicating that MSA prions are remarkably stable and resistent to inactivation strongly suggest caution when working with materials that might contain αS prions [491]. In vitro studies and animal models have also confirmed the seeding ability of αS [459, 492–494], and that MSA is caused by a unique strain of αS assemblies [130, 495–497]. The existing data suggest that neuron-derived αS with conformational changes contributes to the formation of GCIs, that primary oligodendroglia dysfunction may cause accumulation of αS fibrils in their cytoplasm, and that cell-to-cell spreading of αS may initiate new aggregate formation as the disease propagates [14, 498, 499]. Viral-induced oligodendroglial expression of αS allows replicating some of the key features of MSA, e.g., how αS accumulation in selected oligodendroglial populations contribute to the pathophysiology of the disease [500, 501].

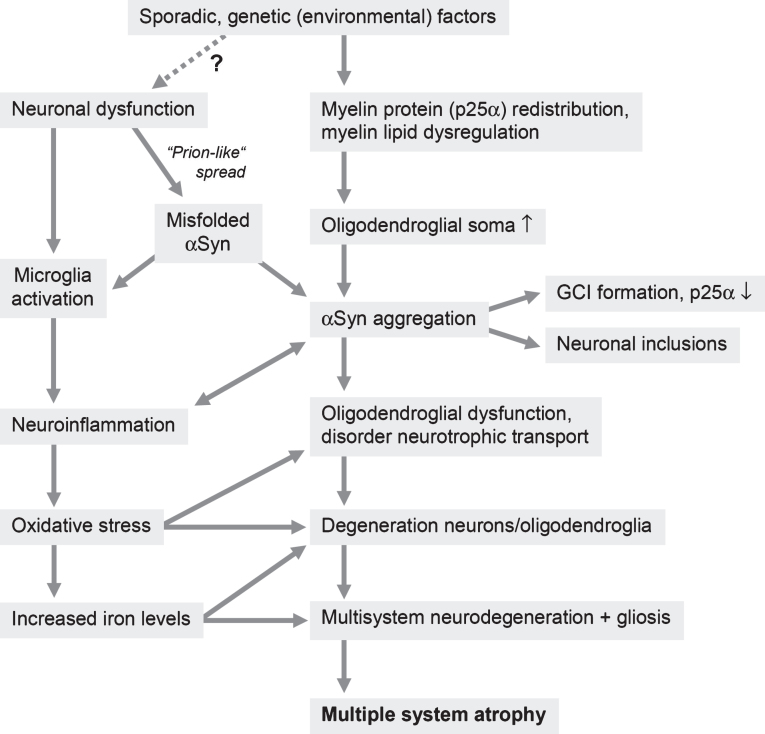

Current view on the pathogenic pathways of MSA (see Fig. 4)

Fig.4.

Putative pathogenic pathways of MSA (modified from [502]).

Although major advances have been achieved in understanding the pathophysiological structure of αS [495, 496, 503, 504], the first hit that triggers the neurodegenerative cascade remains to be elucidated. In the light of in vitro studies, suggesting that the oligodendroglial-specific phosphoprotein-25α (p25α) relocation from the myelin sheath to the oligodendroglial cytoplasm followed by cytoplasmic accumulation of p25α is an intriguing early finding in MSA [505, 506]. It functions in the stabilization of microtubules and the differentiation of oligodendrocytes [507] and is associated with myelin dysfunction, reduction in full-length MBP, demyelination of small-caliber axons, and an increase in oligodendroglial soma size, preceding αS aggregation [505]. The interaction between p25α, a potent stimulator of αS aggregation [505, 508, 509], and αS promotes its phosphorylation and aggregation into insoluble oligomers with later formation of GCIs. These changes and decrease in p25α in oligodendrocytes containing αS positive GCIs imply that mitochondrial dysfunction may lead to secondary p25α relocation [510]. The aberrant αS undergoing fibrillation then aggregates to form GCIs, enhanced by misplaced p25α, which is being incorporated into inclusions before αS [511]. The role of the microtubule-associated TPPP/p25 in PD and related diseases has recently been reviewed. Aggregation of αS interferes with oligodendrocytes, preventing the formation of mature oligodendroglial cells [512, 513]. Transgenic expression of human αS indicated that accumulation of αS in oligodendroglia induces subsequent degeneration of both oligodendroglia and neurons [468, 514]. Enhanced FAS (Fas cell surface death receptor) gene expression is an early hallmark of oligodendroglial pathology in MSA that may be related to αS dependent degeneration [262, 515]. Differential involvement of the cystein protease inhibitor cystein C that is associated with increased risk of neurodegeneration in MSA phenotypes supports its role in MSA pathogenesis [516]. Formation of GCIs interferes with oligodendroglial and neuronal trophic transport leading to death of these cells and to initiation of neuroinflammation by activation of quiescent microglia [451]. The association of GCI burden and activated microglial cells [254] suggests that αS triggers neuroinflammatory responses. This was corroborated by experimental studies both in vitro and in vivo [261, 263, 517]. Microglia activation may contribute to the neurodegenerative process in MSA via increased levels of reactive oxygen species in degenerating areas [258]. However, the mechanisms inducing αS dependent microglia activation remain to be elucidated [249]. It can be speculated, that the paradoxical protein expression in pons of MSA (with increased tissue iron, increased ferritin, and decreased ferroportin indicating reduction of bioavailable iron) is associated with neuroinflammation as hepcidin is induced by cytokines and may result in chronic diseases like anemia with elevation of total body iron with reduced bioavailable iron [518]. Changes in T-cell-associated cytokines may shed light on immune mechanisms that contribute to MSA [519]. Increased mRNA levels of GSK3β that is involved in neuroinflammatory pathways, MHC class II+ and CD45+ positive cells in prefrontal cortex of MSA suggest widespread neuroinflammatory reactions in MSA pathogenesis [520].

Finally, the cell death mechanisms are poorly understood. Increased iron levels in degenerating brain areas suggested that oxidative stress may play a significant role in the selected neuronal death in MSA, and microglial activation may contribute to increased levels of reactive oxygen species in the degenerating areas [258]. Loss of phosphoprotein DARPP-32 and calbindin-D 28k in areas of less prominent or absent neuronal loss indicates that calcium toxicity and disturbance of the phosphorylated state of proteins are early events in MSA pathogenesis [520]. The apoptosis-modulating proteins Bax and Bcl-X are increased, which may lead to initiation of apoptosis in the affected areas [521]. Pathological and biochemical analyses revealed that autophagy/beclin1 regulator 1 (AMBRA1) is a component of the pathological hallmark and upstream autophagy proteins are impaired in the MSA brain. AMBRA1 is a novel hub binding protein of αS and plays a central role through the degradative dynamics of αS [191]. Mechanisms possibly related to cell death in MSA include X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) which is upregulated in GCI- and NCI-bearing cells [200], proteasomal or autophagosomal dysfunction [522], supported by experimental studies [469, 523]. αS accumulation in cells may induce metabolic imbalance, which may promote cell death. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase upregulation in neurons and oligodendrocytes suggests a possible response to apoptotic signals in these cells [524]. Further mechanisms include proteasomal [525] or autophagosomal dysfunctions [522, 526], supported by experimental studies [258, 469, 523], or an altered communication between neurons and oligodendrocytes due to perturbation of their neurotrophic transport [527].

CURRENT THERAPIES

So far there are no causative or disease-modifying treatments available and symptomatic therapies are limited [1, 49]. Levodopa responsiveness has been reported initially in 83% of MSA-P patients [353], but the effect is usually transient, and only 31% showed a response for a period of 3.5 years [31]. In some patients, motor fluctuations with wearing-off phenomena or off-bound dystonia were observed [438]. Deep brain stimulation could not be recommended for MSA [321], while active immunization against αS and combination with anti-inflammatory treatment may be promising therapeutic strategies [16, 439–442]. New strategies targeting αS are in progress [23, 436, 443], based on completed or ongoing interventional trials by the MSA Coalition [23]. Therefore, there is a strong need to clarify the pathogenic mechanisms in MSA in order to develop new therapeutic strategies options.

CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER OUTLOOK

Current evidence supports the hypothesis that misfolded αS contributes to oxidative stress through a pathway that induces microglial activation and antioxidant response requiring an additional protein structure [528], but oxidative stress appears unlikely to represent the sole mechanism for αS aggregation. Region specific increased accumulation of intracellular iron in pons and putamen in MSA may indicate its local dysregulation due to a deficit of bioavailable iron [299]. While experimental studies support the involvement of the proteasome and autophagosome dysfunction in oligodendroglial α-synucleinopathy [258, 523], excitotoxic cell death was not aggravated by GCI pathology [529]. The burden of neuronal pathology appears to increase multifocally as an effect of disease duration associated with increasing overall αS burden, the underlying mechanisms of which as well as of those leading to widespread demyelination need further elucidation.

In conclusion, the cascade of events that underlies the pathogenesis of MSA is currently not completely understood. Recent studies using animal models that only partly replicate the human pathology and the molecular dynamics of the neurodegenerative process have provided some progress in our understanding of MSA pathogenesis. Relocation of p25α from the myelin sheaths to the oligodendroglial soma (due to mitochondrial dysfunction), with formation of cytoplasmic p25α inclusions seems to precede aggregation of transformed αS assemblies in oligodendrocytes. This is associated with disruption of myelin homeostasis. The source of αS in oligodendrogliosis is unclear, but it contains αS mRNA expression and αS may be secreted by neurons and taken up by oligodendrocytes to form GCIs. Secondary events in the oligodendroglial inclusion pathway include reduced trophic support to axons and neurons by reduced glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, proteolytic dysbalance, and energy failure are further essential factors in the cascade leading to neurodegeneration in MSA. The disease is currently viewed as a primary synucleinopathy with specific (oligodendro)glial-neuronal degeneration developing secondarily via the oligo-myelin-axon-neuron complex [155], and also has been listed among the predominant oligodendroglial proteinopathies [15]. Strong evidence against a primary neuronal pathology with formation of GCIs resulting from secondary accumulation of pathological αS that may be of neuronal origin [527], is the fact that GCIs are the hallmark of MSA and not of PD, a disease with similar lesion patterns of αS immunoreactive inclusions (LBs) but no or few GCIs, which differentiates the two disorders [451]. Although the source of αS in both disorders is under discussion, “prion-like” spreading of the misfolded protein, oxidative damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, proteolytic dysbalance, dysregulation of myelin lipids, neuroinflammation, and energy failure are the essential noxious factors in the cascade leading to the pathogenesis of systemic neurodegeneration in this unique proteinopathy. Multidisciplinary research to further elucidate the pathologic mechanisms of neurodegeneration in MSA in order to develop reliable biomarkers for early diagnosis and disease-modifying therapies of this hitherto incurable disorder is strongly needed.