Abstract

Glucose is absorbed through the intestine by a transepithelial transport system initiated at the apical membrane by the cotransporter SGLT-1; intracellular glucose is then assumed to diffuse across the basolateral membrane through GLUT2. Here, we evaluated the impact of GLUT2 gene inactivation on this transepithelial transport process. We report that the kinetics of transepithelial glucose transport, as assessed in oral glucose tolerance tests, was identical in the presence or absence of GLUT2; that the transport was transcellular because it could be inhibited by the SGLT-1 inhibitor phlorizin, and that it could not be explained by overexpression of another known glucose transporter. By using an isolated intestine perfusion system, we demonstrated that the rate of transepithelial transport was similar in control and GLUT2−/− intestine and that it was increased to the same extent by cAMP in both situations. However, in the absence, but not in the presence, of GLUT2, the transport was inhibited dose-dependently by the glucose-6-phosphate translocase inhibitor S4048. Furthermore, whereas transport of [14C]glucose proceeded with the same kinetics in control and GLUT2−/− intestine, [14C]3-O-methylglucose was transported in intestine of control but not of mutant mice. Together our data demonstrate the existence of a transepithelial glucose transport system in GLUT2−/− intestine that requires glucose phosphorylation and transfer of glucose-6-phosphate into the endoplasmic reticulum. Glucose may then be released out of the cells by a membrane traffic-based pathway similar to the one we previously described in GLUT2-null hepatocytes.

After intake and digestion, carbohydrates are absorbed in the small intestine of mammals by a two-step transport system. In the first step, glucose is concentrated in the cells by a mechanism catalyzed by the apically located sodium-dependent glucose transporter SGLT-1. This symporter uses the electrochemical gradient of two sodium ions to transport one glucose molecule (1). The second step is the release of the intracellular glucose into the interstitial space by a mechanism thought to occur by facilitated diffusion via the glucose transporter GLUT2 (2) located in the basolateral membrane.

It is generally believed that SGLT-1 is the only translocator for entry of glucose into the enterocytes. The most forward evidence comes from patients suffering from glucose/galactose malabsorption, a potentially fatal condition, which is caused by inactivating mutations in SGLT-1 (3). In contrast, the contribution of GLUT2 to the second step of transepithelial glucose transport rests mainly on its immunolocalization to the basolateral membrane domain (4) and on studies of glucose transport in vesicles derived from these membranes, which showed properties compatible with the presence of GLUT2 (5). Thus, whereas GLUT2 may contribute to the second step of transepithelial glucose transport, separate mechanisms also may exist.

Recently, GLUT2−/− mice were generated (6). They showed a diabetic-like phenotype and died between 2 and 3 wk after birth because of a defect in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Re-expressing either GLUT1 or GLUT2, in their β cells by transgenesis, allowed the mice (RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− or RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/−) to survive and breed (7). Because these rescued GLUT2−/− mice still did not express GLUT2 in the intestine, they should have shown symptoms of glucose/galactose malabsorption if this transporter also was required for intestinal glucose absorption. However, oral glucose load still resulted in normal rate of glucose appearance in the blood, indicating that GLUT2 was not strictly required (7). Similarly, human individuals with Fanconi-Bickel syndrome, caused by inactivation in both allele of GLUT2 (8), did not present abnormal carbohydrate ingestion (9–11).

Here, we therefore investigated the GLUT2-independent mechanisms by which glucose can be absorbed in the intestine in the absence of GLUT2. In particular, we used the newly developed isolated intestine perfusion technique that allows precise monitoring of transepithelial glucose transport (12, 13). We demonstrated that, in the absence of GLUT2, transepithelial transport proceeded with a normal kinetics. It was, however, inhibited by a glucose 6-P translocase inhibitor and did not allow transport of the nonphosphorylated substrate 3-O-methylglucose. These data are consistent with the existence of a separate pathway for glucose release from intestine that requires glucose phosphorylation, transport into the endoplasmic reticulum, and after dephosphorylation, release through a membrane-traffic based mechanism.

Methods

Mice.

Mice (RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/−) were from our colonies. They were derived from GLUT2−/− mice (6) by transgenic re-expression of GLUT1 in the pancreatic β cells under the control of the rat insulin promoter (RIP) (7). Control mice were C57BL/6.

Northern Blot Analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from various tissues by the acid guanidinium thiocyanate technique (14) and analyzed for the presence of GLUT1, 2, 3, 5, 8, and 9 mRNA by Northern blot analysis as described (15, 16).

Oral Glucose Tolerance Tests and Fructose Measurements.

Oral glucose tolerance tests were carried out with mice that had fasted for 18 h. An oral bolus of 60–75 μl of a 40 mg/ml glucose solution was given to the mice. Phlorizin was diluted in propylenglycol (1 g/3 ml) and 0.4 g/kg was administered orally 5 min before glucose administration and also was added to the glucose bolus. Control-treated mice received the same volumes of propylenglycol and glucose solution. Blood glucose was monitored at the indicated times from tail vein blood and by using a glucose meter (Glucotrend, Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Isolated, Nonrecirculating, Joint Perfusion of Small Bowel and Liver of Mice.

This perfusion system is an isolated, single path, vascular perfusion with an erythrocyte-free perfusion medium via the coeliac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery. This system allowed the direct measurement of intestinal glucose absorption as an increase in portal glucose concentration because the portal vein is the draining vessel of the gut.

The preparation was performed in analogy to the established perfusion system of the rat (12) with some modifications because of the smaller scale and higher tissue fragility of the mice. The mice (21–32 g) were anaesthetized by an i.p. injection of pentobarbital (20 mg/kg). After the opening of the abdomen, a cannula was introduced into the superior mesenteric artery, the inferior vena cava was cut open with a lancet, and a nonrecirculating perfusion of intestine and liver was started at a hydrostatic pressure of 120 cm H2O and a flow rate of ≈8 ml/min. The cannula was fixed within the superior mesenteric artery with the ligatures. Spleen, pancreas, and stomach were resected after ligating their arteries and veins. A cannula was introduced into the thoracic aorta and the tip was forwarded to the ostium of the coeliac trunk and fixed with ligatures in this position followed by starting a perfusion with a hydrostatic pressure of 120 cm H2O and a flow rate of 5 ml/min. Then a plastic catheter was placed through the pylorus in the lumen of the duodenum. The coecum was incised and the intestinal content washed out with a warmed saline solution. During the experiments, the duodenal catheter was used to apply the luminal glucose bolus. Afterward, a cannula for the vascular outflow was introduced into the right atrium and the tip positioned at the inflow of the hepatic vein into the inferior vena cava and fixed. After dissection of intestine and liver from the body this organ block was transferred into an organ bath filled with a warmed saline solution. Finally, a flexible catheter was introduced into the portal vein to obtain perfusion medium samples for subsequent determination of glucose concentrations. The preparations were finished after ≈60 min and the experiments started after a preperfusion period of 20 min.

The perfusion medium consisted of a Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing 5 mM glucose, 2 mM lactate, 0.2 mM pyruvate, 1 mM glutamine, 3% dextran, and 1% BSA, equilibrated with a gas mixture of O2/CO2 (19:1). The luminal glucose bolus (1.1 mmol in 0.25 ml of 0.9% NaCl solution within 1 min) was applied immediately postpyloric into the duodenum. The glucose-6-phosphate translocase S4048 was a generous gift of A. W. Herling (Aventis, Frankfurt). Glucose was measured with glucose dehydrogenase (17). Fructose was measured by using hexokinase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and phosphoglucose isomerase (18).

Results

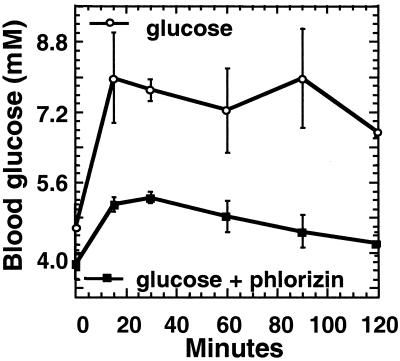

To evaluate whether glucose absorption occurred via a transcellular pathway, oral glucose tolerance tests were performed with or without addition of phlorizin, an inhibitor of the SGLT-1. Fig. 1 shows that phlorizin administration greatly reduced appearance of glucose in the blood, indicating that absorption was mostly through a transcellular route.

Figure 1.

Intestinal glucose absorption in the absence of GLUT2 is through a transcellular route. Fasted RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice were subjected to an oral glucose tolerance test with or without simultaneous oral administration of phlorizin, an inhibitor of SGLT1. In the absence of phlorizin, there was a rapid rate of appearance of glucose in the blood, which was markedly reduced by SGLT-1 blockade. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 4–6 mice for each point.

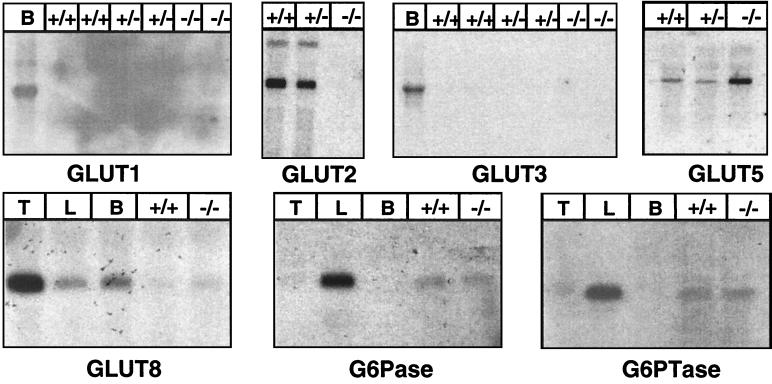

Because the absence of the GLUT2 might have been compensated for by another member of the GLUT family we analyzed, by Northern blotting, the expression of the known glucose transporters in the intestine of control and RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice. Fig. 2 shows that there was no GLUT2 expression in the RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice. There was also no expression of GLUT1 or GLUT3. GLUT8 (16) was present at approximately the same low level in control and mutant intestine, and GLUT9 (19) was not expressed (not shown). Expression of GLUT5, a fructose transporter located in the apical membrane of epithelial cells (20, 21) and whose expression is known to be up-regulated in diabetes (22), was increased, however.

Figure 2.

Northern blot analysis of glucose transporter, glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), and glucose-6-phosphate translocase (G6PTase) mRNA expression in intestine of control (+/+), GLUT2+/− (+/−), and RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− (−/−) mice. GLUT1 is not detectable in any of the mRNA preparations except in brain (B) mRNA preparations. GLUT2 is present in control and heterozygous mRNA preparations but not detectable in RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice. GLUT3 is not detectable in any preparation; GLUT8 is expressed at the same very low level in control and GLUT2-deficient intestine. GLUT5 is expressed at relatively low level in control (+/+) and heterozygous mice (+/−) RNA preparation and is increased in mRNA preparations from RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice. G6Pase and G6PTase are at the same level in control and mutant intestines. Control RNAs are from brain (B), testis, (T), or liver (L).

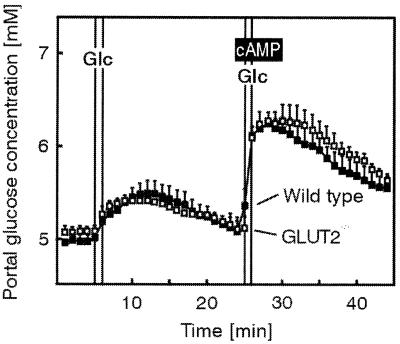

To more precisely examine the kinetics of transepithelial glucose transport in the GLUT2−/− mice, the isolated jointly perfused small intestine and liver was used. Fig. 3 shows that the rate of glucose appearance in the portal vein after an application of a glucose bolus into the intestinal lumen was similar in control and GLUT2−/− intestine for magnitude and kinetics. cAMP acutely increases glucose absorption via SGLT1 in the isolated, perfused small intestine as well as in isolated enterocytes (23). To evaluate whether the cAMP-increased glucose absorption via SGLT1 might exceed the capacity of the GLUT2-independent transport system in the basolateral membrane, perfusion experiments with arterial infusion of cAMP were performed. As shown in Fig. 3, the cAMP-stimulated transepithelial glucose transport was similar in small intestine from control and GLUT2-deficient mice.

Figure 3.

Basal and cAMP-stimulated glucose absorption in the isolated perfused intestine and liver of control (wild-type) and RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice. Intestine and liver were perfused via the superior mesenteric artery and the coeliac trunk with a Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate buffer. Glucose (Glc) (150 mg within 1 min) was applied as an intraluminal bolus in minute 6 and again in minute 26; it was absorbed as indicated by the increase in portal glucose concentration. From the 23rd to the 29th minute of the experiment, cAMP (effective concentration 10 μM) was infused into the mesenteric artery. Values are means ± SEM of 5–6 experiments each.

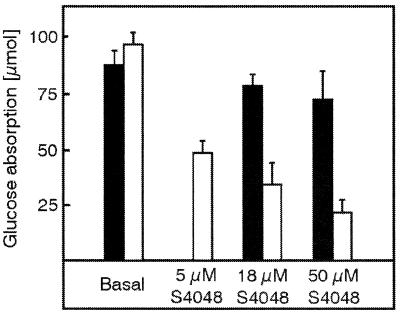

In livers from RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice, we proposed that glucose could be released into the circulation directly from the endoplasmic reticulum where it is generated by hydrolysis of glucose-6-phosphate (15). Therefore, if a similar mechanism accounted for glucose release on the serosal side of the epithelial cells, transport should be inhibited by the chlorogenic acid derivative S4048, which blocks the glucose-6-phosphate translocase within the membrane of the endoplasmatic reticulum (24, 25). In perfused intestine from wild-type mice, increasing concentrations of S4048 only slightly decreased glucose absorption (Fig. 4). However, glucose absorption in the intestine of RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice was concentration-dependently decreased to only 25% of the maximal rate with maximum inhibition reached at 50 μM of S4048.

Figure 4.

Basal and S4048-inhibited glucose absorption in the isolated perfused intestine and liver of control (closed bars) and RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− (open bars) mice. Intestine and liver were perfused as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Glucose absorption is calculated by the area under the portal glucose concentration curve multiplied by the flow rate. Glucose (150 mg within 1 min) was applied as an intraluminal bolus in minute 6 and again in minute 41. From the 11th to the 45th minute of the experiment, S4048 was infused with the effective concentrations given in the figure into the mesenteric artery. Values are means ± SEM of 4–5 experiments each.

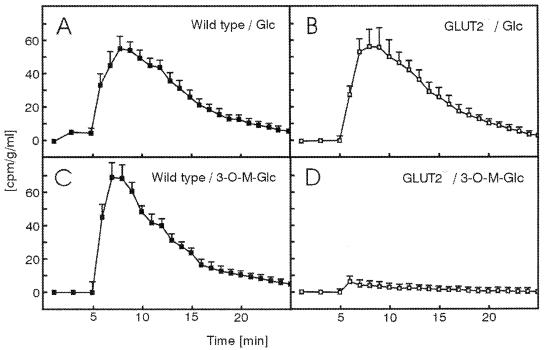

To evaluate whether phosphorylation of glucose was required, we measured the rate of transepithelial transport of [14C]3-O-methylglucose, which is a substrate for SGLT-1, GLUT2, and all other known glucose transporters but is not phosphorylated by hexokinases. Fig. 5 A and B shows that the transport of [14C]glucose proceeded with the same kinetics in control and GLUT2−/− intestines, in agreement with the data obtained with nonlabeled glucose presented above. In contrast, whereas [14C]3-O-methylglucose was transported with the same kinetics as [14C]glucose in control intestine, its absorption in GLUT2−/− intestine was almost completely suppressed (Fig. 5 C and D).

Figure 5.

Absorption [14C]glucose or [14C]3-O-methylglucose in the isolated perfused intestine and liver of control (wild type) and GLUT2−/−mice. Intestine and liver were perfused as described in the legend to Fig. 3. [14C]glucose or [14C]3-O-methylglucose (1 μCi) was applied as an intraluminal bolus in minute 6. Samples of the perfusion medium (100 μl) were obtained, transferred to scintillation fluid, and counted for radioactivity. Values are means ± SEM of four experiments.

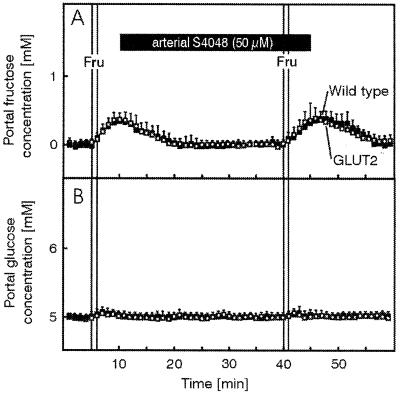

Together the above data indicate that glucose transport through intestinal epithelial cells in the absence of GLUT2 requires glucose phosphorylation and a functional glucose-6-phosphate translocase. Ttransepithelial glucose transport may thus use a membrane traffic-based pathway issued from the endoplasmic reticulum for delivery of glucose to the serosal side. However, GLUT5 expression is increased in the mutant mice and, in human, this transporter also has been found in the basolateral membrane of enterocytes (26). Although it is not known whether there is a similar basolateral expression in the mouse, we needed to determine, first, whether fructose transepithelial transport still occurred in the mutant mice and, second, if this fructose pathway also could account for glucose transport. To address these questions, we performed intestine fructose perfusion experiments in the absence and presence of S4048. Fig. 6 shows that the kinetics of fructose appearance in the portal vein after injection of a luminal bolus was not different in the presence or absence of GLUT2. Importantly, fructose transport was not reduced in the GLUT2−/− intestine by S4048 present at a concentration giving maximal inhibition of glucose transport. Furthermore, Fig. 6 also shows that no conversion of fructose to glucose occurred during the transport process.

Figure 6.

Basal and S4048-unaltered fructose absorption in the isolated perfused intestine and liver of control (closed symbols) and RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− (open symbols) mice. Intestine and liver were perfused as described in the legend to fig. 3. Fructose (Fru, 150 mg within 1 min) was applied as an intraluminal bolus in minute 6 to determine basal absorption and again in minute 41 to evaluate the influence of S4048 on fructose absorption. From the 11th to the 45th minute of the experiment S4048 (50 μm, effective concentration) was infused into the mesenteric artery. (A) Portal fructose concentrations. (B) Portal glucose concentrations. Values are means ± SEM of four experiments each.

As we propose that glucose transport involves glucose-6-phosphate translocase and glucose-6-phosphatase action, we determined the expression of these genes in the intestine of control and RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 2, both mRNA were found to be expressed at the same level in control and mutant mice, but at lower level than in liver of control mice, in agreement with published data (27, 28).

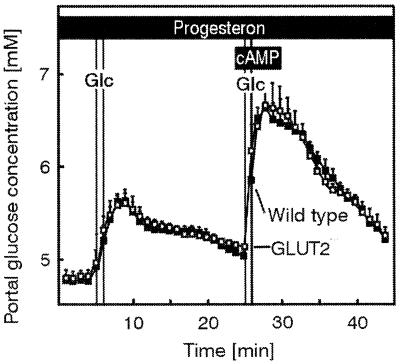

In a preceding study of glucose output from liver, it was observed that progesterone acutely inhibited glucose release in GLUT2−/− but not in control hepatocytes. This inhibitory effect, however, could not be detected on transcellular glucose transport in GLUT2−/− intestine, neither in basal conditions nor on cAMP-stimulated transport (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Glucose transport in control and GLUT2−/− intestine. Effect of progesterone. No effect of progesterone on basal and cAMP-stimulated glucose absorption in the isolated perfused intestine and liver of control (wild type) and GLUT2−/− mice. Intestine and liver were perfused as described in the legend to Fig. 3; however, progesterone (10 μg/ml) was added to the perfusion medium. Glucose (Glc) (150 mg within 1 min) was applied as an intraluminal bolus in minute 6 and again in minute 26. From the 23rd to the 29th minute of the experiment, cAMP (effective concentration 10 μM) was infused into the mesenteric artery. Values are means ± SEM of 4–5 experiments each.

Discussion

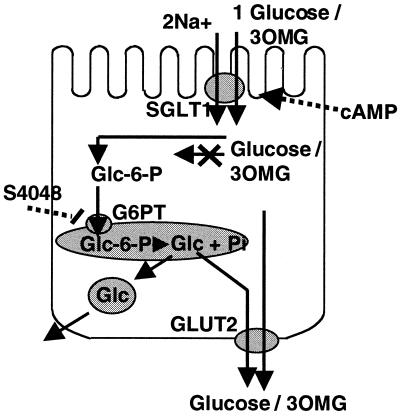

The present study using the isolated, perfused small intestine and liver demonstrated the existence of a different mechanism for glucose transepithelial transport across the basolateral membrane of enterocytes when the glucose transporter GLUT2 is present or absent. This mechanism allowed the same kinetics of transport as in control epithelial cells even after cAMP-stimulated glucose absorption. However, it required a metabolizable form of glucose as a substrate and a functioning glucose-6-phosphate translocase.

This study was prompted by the observation that in RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice an oral glucose load still resulted in a normal kinetics of glucose appearance in the blood. This result was unexpected because GLUT2 is the major, if not only, glucose transporter present in the basolateral membrane of intestinal epithelial cells. In an attempt to identify the mechanism of GLUT2-independent glucose transport across the basolateral membrane, intestinal perfusion experiments were performed. They showed no difference in transport rate between control and GLUT2−/− intestines either in basal or cAMP-stimulated conditions.

In principle, in RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− animals glucose could use a paracellular pathway caused by opening of the tight junctions. Because in vivo glucose absorption could be markedly reduced by phlorizin, a competitive inhibitor of the SGLT-1, absorption must have occurred transcellularly. However, the question remained, how translocation of glucose across the basolateral membrane might take place. This translocation cannot be the rate-limiting step of the absorptive process because even the increased amounts of glucose entering the enterocytes after stimulation with cAMP did not override its capacity. A possible escape way for glucose in the RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice could be an adaptive up-regulation of another GLUT. By means of Northern blotting, expression of GLUT1, GLUT3, and GLUT9 could not be detected. GLUT8, an intracellularly located transporter, which can also use 3-O-methylglucose as a substrate (16), was present at the same low level as in control mice. These data indicate that no other members of the GLUT family compensate for the lack of GLUT2 in the basolateral membrane. Therefore, glucose absorption in the intestines of RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice must occur via a transcellular pathway with the SGLT-1 being the involved translocator in the apical membrane and the rate-limiting step.

Transport in the mutant cells was inhibited by the chlorogenic acid derivative S4048, which blocks glucose-6-phosphate translocase. This protein transports glucose-6-phosphate from the cytosol into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum where the active site of glucose-6-phosphatase is located. Reduction in the rate of glucose transepithelial transport by S4048 therefore indicated that in GLUT2−/− cells glucose had to be phosphorylated and then transported into the endoplasmic reticulum for its subsequent release from the cells. That glucose phosphorylation was required was further supported by the observation that [14C]3-O-methylglucose, which is a substrate for SGLT-1 but which cannot be phosphorylated by the hexokinases, was not transported in the GLUT2−/− intestine but was normally transported in control intestine.

Fructose transepithelial transport in intestine is initiated at the apical side by GLUT5 and is thought to be released through the basolateral membrane by GLUT2. However, in human, GLUT5 has been reported to be also found in the basolateral membrane of intestinal epithelial cells (26); a similar localization has not yet been established in the mouse. In addition, GLUT5 also may transport glucose, although this also has not been described for the mouse transporter. Therefore, we tested whether fructose transport was impaired in the absence of GLUT2. Our fructose perfusion experiments showed that transport of this hexose was as efficient in control and mutant intestines. Furthermore, fructose was not converted to glucose during this transport process and there was no inhibition of transport by S4048. This finding therefore suggests, first, that GLUT5 also may be located in the basolateral membrane to account for fructose release on the serosal side, second, that fructose does not need to be converted into glucose for its release outside of the cells, and third, that an active glucose-6-phosphate translocase was not required for fructose transport. Finally and most importantly, glucose and fructose are unlikely to share the same pathway to exit the cells because glucose release, in contrast to that of fructose, can be blocked by S4048.

Glucose uptake by GLUT2−/− hepatocytes is almost entirely blocked but the rate of glucose output is unchanged (15, 29). This pointed to the existence of an alternative glucose transport mechanism across the membrane of hepatocytes. Further characterization demonstrated that this alternative mechanism was low-temperature sensitive and could be inhibited by progesterone but was not sensitive to the classical inhibitors of intracellular transport brefeldin A and monensin. Therefore, we proposed that in the absence of GLUT2, glucose was released from hepatocytes by a membrane-traffic based mechanism, most likely originating from the endoplasmic reticulum and leading directly to the plasma membrane. We also presented evidence that this pathway may coexist with a GLUT2-dependent pathway in normal hepatocytes. In intestine, the alternative pathway also seems to be present in wild-type enterocytes. In these cells, S4048 with a concentration of 50 μM reduced glucose absorption by 15%. Therefore, in the normal situation with expression of GLUT2, glucose is released into the circulation via both the transporter and the membrane traffic-based mechanism. In GLUT2-deficient enterocytes, the alternative pathway can completely compensate for the lack of GLUT2. However, one difference between hepatocytes and intestine is that progesterone inhibited glucose release only from hepatocytes but not transport in enterocytes. The reason for this differential effect is not known but may reflect cell-specific differences in the glucose release mechanism or reduced progesterone access to the cell cytoplasm in the present experiments.

Fig. 8 summarizes the observations made in the present study and proposes a model for glucose transepithelial glucose transport in GLUT2−/− epithelial cells. This model is similar to that proposed for glucose release from GLUT2−/− hepatocytes. The experiments performed here, however, are complementary to those performed with hepatocytes. In particular, we could directly demonstrate a requirement for glucose entry into the endoplasmic reticulum for its eventual release out of the cells. In hepatocytes, this experiment could not be performed because we were studying release of glucose newly synthesized from pyruvate. In addition, the fact that 3-O-methylglucose could not be transported across the intestinal epithelium in the absence of GLUT2 strongly argues in favor of phosphorylation of glucose being required. Together these studies further support the model for a membrane traffic-based mechanism for glucose release not only from hepatocytes but also from intestinal epithelial cells.

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanism for glucose transepithelial transport in the absence of GLUT2. Glucose enters the epithelial cells by a process catalyzed by the cotransporter SGLT-1. Intracellular cAMP activates the transepithelial transport by a mechanism possibly involving phosphorylation of SGLT-1. The glucose accumulated intracellularly can diffuse out of the cells by facilitated diffusion through GLUT2. In the absence of GLUT2, transepithelial transport requires glucose to be phosphorylated into glucose-6-phosphate followed by its entry into the endoplasmic reticulum where it is hydrolyzed to glucose and phosphate. Glucose is then released out the cells by a mechanism based on membrane traffic. In wild-type cells, glucose can probably re-enter the cytosol and diffuse out of the cell through GLUT2. This model is in agreement with the observation that 3-O-methylglucose, which cannot be phosphorylated, is not transported across the epithelial cells in GLUT2−/− intestine and in agreement with the fact that transport of glucose can be blocked by the glucose-6-phosphate translocase inhibitor S4808. This model is similar to that proposed for glucose output from the GLUT2−/− hepatocytes (29).

In this context, it should also be noted that RIPGLUT1×GLUT2−/− mice are glycosuric, indicating impaired kidney glucose reabsorption, an observation also made in Fanconi-Bickel patients. Glucose reabsorption in the kidney involves different transepithelial transport systems. In the proximal convoluted tubule, the apical cotransporter is SGLT-2 and GLUT2 is in the basolateral membrane. In the straight part, the apical cotransporter is SGLT-1 and the basolateral membrane transporter is GLUT1 (30). The observed glycosuria of the mutant mice therefore indicates that glucose reabsorption is strongly impaired in the absence of GLUT2, suggesting that the alternative pathway for glucose transport does not exist in the renal epithelial cells.

Finally, the existence of a membrane traffic-based pathway for glucose transport in intestinal epithelial cells or for glucose exit from hepatocytes may be required to compartmentalize glucose away from the cytosol. Indeed, glucose and glucose-6-phosphate are potent allosteric regulators of glycogen phosphorylase and glycogen synthase, respectively, (31, 32), which together stimulate glycogen synthesis. Glucose also stimulates the expression of glucose-sensitive genes such as those for pyruvate kinase, fatty acid synthase, or GLUT2 itself (33–35). Thus, when glucose production is required to prevent development of hypoglycemia, an increase in cytosolic glucose concentration could paradoxically stimulate glucose storage and use. Cytosolic glucose build-up could be prevented, however, if glucose produced in the endoplasmic reticulum is released without re-entering the cytoplasm. Whether this pathway is regulated by the metabolic or hormonal state of the organism is not yet known, however.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Hunger and Birgit Döring for expert technical assistance and Dr. Emile van Schaftingen for the glucose-6-phosphate translocase cDNA. This work was supported by Grant 31–46958.96 from the Swiss National Science Foundation (to B.T.).

Abbreviation

- RIP

rat insulin promoter

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Hediger M A, Rhoads D B. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:993–1026. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.4.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorens B. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:G541–G553. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.4.G541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin M G, Turk E, Lostao M P, Kerner C, Wright E M. Nat Genet. 1996;12:216–220. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorens B, Cheng Z-Q, Brown D, Lodish H F. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C279–C258. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.2.C279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheeseman C I. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1050–1056. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90948-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillam M-T, Hümmler E, Schaerer E, Yeh J-Y, Birnbaum M J, Beermann F, Schmidt A, Dériaz N, Thorens B. Nat Genet. 1997;17:327–330. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorens B, Guillam M-T, Beermann F, Burcelin R, Jaquet M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23751–23758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santer R, Schneppenheim R, Dombrowski A, Götze H, Steinmann B, Schaub J. Nat Genet. 1997;17:324–326. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odièvre M. Rev Inst Hépatol. 1966;16:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brivet M, Moatti N, Corriat A, Lemonnier A, Odièvre M. Pediatr Res. 1983;17:157–161. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198302000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manz F, Bickel H, Brodehl J, Feist D, Gellissen K, Geschll-Bauer B, Gilli G, Helwig H, Nützenadel W, Waldherr R. Pediatr Nephrol. 1987;1:509–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00849262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stümpel F, Kucera T, Gardemann A, Jungermann K. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1863–1869. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stümpel F, Kucera T, Gardemann A, Jungermann K. In: Liver Innervation. Shimazu T, editor. London: John Libey; 1996. pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillam M-T, Burcelin R, Thorens B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12317–12321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibberson M, Uldry M, Thorens B. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4607–4612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banauch D, Brümmer W, Ebeling W, Metz H, Rendrey H, Leybold K, Rick W. Z Klin Chem Klin Biochem. 1975;13:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wetterauer U, Heite H J. Arch Dermatol. 1976;2:239–248. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doege H, Bocianski A, Joost H G, Schurmann A. Biochem J. 2000;350:771–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burant C F, Takeda J, Brot-Laroche E, Bell G I, Davidson N O. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14523–14526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahraoui L, Rousset M, Dussaulx E, Darmoul D, Zweibaum A, Brot-Laroche E. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:G312–G318. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.3.G312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burant C F, Flink S, Depaoli A M, Chen J, Lee W-S, Hediger M A, Buse J B, Chang E B. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:578–585. doi: 10.1172/JCI117010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stümpel F, Scholtka B, Jungermann K. FEBS Lett. 1998;410:515–519. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00628-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemmerle H, Burger H-J, Below P, Schubert G, Rippel R, Schindler P W, Paulu E, Herling A W. J Med Chem. 1997;40:137–145. doi: 10.1021/jm9607360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arion W J, Canfield W K, Ramos F C, Su M L, Burger H-J, Hemmerle H, Schubert G, Below P, Herling A W. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;351:279–285. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blakemore S J, Aledo J C, James J, Campbell F C, Lucocq J M, Hundal H S. Biochem J. 1995;309:7–12. doi: 10.1042/bj3090007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chatelain F, Pégorier J-P, Minassian C, Bruni N, Tarpin S, Girard J, Mithieux G. Diabetes. 1998;47:882–889. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.6.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croset M, Rajas F, Zitoun C, Hurot J-M, Montano S, Mithieux G. Diabetes. 2001;50:740–746. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.4.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burcelin R, Muñoz M C, Guillam M-T, Thorens B. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10930–10936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorens B, Lodish H F, Brown D. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C286–C294. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.2.C286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carabaza A, Ciudad C J, Baque S, Guinovart J J. FEBS Lett. 1992;296:211–214. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80381-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bollen M, Keppens S, Stalmans W. Biochem J. 1998;336:19–31. doi: 10.1042/bj3360019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaulont S, Kahn A. FASEB J. 1994;8:28–35. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.1.8299888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girard J, Ferré P, Foufelle F. Annu Rev Nutr. 1997;17:325–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.17.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferraris R P, Diamond J. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:257–302. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]