Abstract

Objective

To systematically identify and describe self-management interventions for adult patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Setting

Community-based.

Participants

Adults with CKD stages 1–5 (not requiring kidney replacement therapy).

Interventions

Self-management strategies for adults with CKD.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Using a scoping review, electronic databases and grey literature were searched in October 2016 to identify self-management interventions for adults with CKD stages 1–5 (not requiring kidney replacement therapy). Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-RCTs, qualitative and mixed method studies were included and study selection and data extraction were independently performed by two reviewers. Outcomes included behaviours, cognitions, physiological measures, symptoms, health status and healthcare.

Results

Fifty studies (19 RCTs, 7 quasi-experimental, 5 observational, 13 pre-post intervention, 1 mixed method and 5 qualitative) reporting 45 interventions were included. The most common intervention topic was diet/nutrition and interventions were regularly delivered face to face. Interventions were administered by a variety of providers, with nursing professionals the most common health professional group. Cognitions (ie, changes in general CKD knowledge, perceived self-management and motivation) were the most frequently reported outcome domain that showed improvement. Less than 1% of the interventions were co-developed with patients and 20% were based on a theory or framework.

Conclusions

There was a wide range of self-management interventions with considerable variability in outcomes for adults with CKD. Major gaps in the literature include lack of patient engagement in the design of the interventions, with the majority of interventions not applying a behavioural change theory to inform their development. This work highlights the need to involve patients to co-developed and evaluate a self-management intervention based on sound theories and clinical evidence.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, scoping review, self-management, person centered-care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of our study is that it is the first scoping review to apply the principles of patient-oriented research, where patient partners were engaged in determining the research question, advising us on search terms and reviewing the results to ensure we captured and reported the data meaningfully.

Our scoping review is comprehensive in nature, with inclusion of all study designs and consideration of self-management features that have not been investigated previously.

Due to the heterogeneous nature of the literature, it was challenging to synthesise the data. To address this challenge the two reviewers used two standardised tools to independently extract data and independently coded the outcomes into categories using the revised Self- and Family Management Framework.

A limitation of our scoping review is that we were unable to assess the self-management outcomes in terms of sustained changes in behaviour, physiological and health status.

We were unable to draw conclusions regarding the most effective self-management intervention for adult patients with chronic kidney disease, keeping in mind that our aim was to review the breadth of the current literature and present the gaps that exist.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with adverse health outcomes, poor quality of life and high healthcare costs.1 Patients with CKD often experience a number of comorbidities including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and depression.2 They must balance the medical management of their kidney disease and other chronic conditions with demands of their daily lives, including managing the emotional and psychosocial consequences of living with chronic disease. In a recent CKD research priority setting study, individuals with non-dialysis CKD, their caregivers, clinicians and policy-makers identified the need to develop optimal strategies to enable patients to manage their CKD and related comorbidities to slow or prevent the progression to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).3 International data in research priority setting for kidney disease also highlights self-management as a top priority to prevent progression.4

Self-management interventions aim to facilitate an individual’s ability to make lifestyle changes and manage symptoms, treatment and the physical and psychosocial consequences inherent in living with CKD and associated comorbidities.5 Self-management of CKD involves focusing on illness needs (developing knowledge, skills and confidence to manage medical aspects), activating resources (identifying and accessing resources and supports) and living with the condition (learning to cope with the condition and its impact on their lives as well as the emotional consequences of the illness).6 Self-management requires patient engagement; however, the degree to which patients are able or willing to participate in self-management can vary, and individual and health system factors may serve as facilitators or barriers to self-management processes.7

Despite the high prevalence of CKD and its impact on patient outcomes, there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of self-management interventions. Prior systematic reviews8–11 and three integrative reviews12–14 found that self-management interventions were variable in their effectiveness for managing and preventing progression of CKD. While these reviews add to the knowledge base, they have restricted inclusion criteria (eg, study type, patient population) and unclear reporting strategies (ie, describing complex self-management interventions in detail and providing structured accounts of the interventions and outcomes). In particular, features of self-management interventions such as person centeredness, applicability to comorbidities associated with CKD, physiological and non-physiological outcomes and application of any behavioural change theories are often lacking. Self-management interventions need to be tailored to suit diverse patient needs and preferences as well as the local healthcare context.7 Therefore, investigating the ‘who’, ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of self-management interventions is crucial. We used recognised literature synthesis and reporting guidelines, along with engagement of our patient partners in determining the research question and search terms as well as reviewing the results to ensure we captured and reported the data meaningfully.

To our knowledge, there is no literature synthesis that systematically and comprehensively summarises the breadth of evidence found in primary quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research regarding self-management interventions for adult patients with CKD. We used a scoping review methodology to understand the range and types of interventions including both educational and support interventions for CKD to inform the future design of a self-management intervention. Specifically, we conducted a scoping review to identify and describe self-management interventions for adult patients with CKD (stages 1–5; non-dialysis, non-transplant).

Materials and methods

We used a scoping review methodology to enable us to incorporate a broad range of studies and to summarise the knowledge from a variety of sources and types of evidence.15 Our aim was to identify gaps in literature related to CKD self-management interventions and inform future research. A unique and important aspect was the involvement of ‘patient partners’. Through a national initiative, Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome CKD (Can-SOLVE CKD), patients work side by side with researchers, clinicians and decision makers to address patient-oriented research priorities.16 Our research team includes Can-SOLVE CKD patient partners with CKD and caregivers.16 Using the Joanna Briggs Institute framework for scoping reviews, we undertook the following steps: (1) identified the research question, (2) identified relevant studies, (3) completed study selection, (4) charted, collated, summarised and reported the results (5) and consulted with our patient partners.15 17 These steps were iterative to ensure comprehensive inclusion of the literature and continued meaningful engagement with our patient partners. This work involves identifying, reviewing and categorising data from primary articles and does not involve human participants and is exempt from ethics approval.

Research aim

Our scoping review aimed to determine the available self-management interventions for adults aged 18 years and over and diagnosed with CKD stages 1–5 (not requiring dialysis or transplant).

Search and selection of studies

We worked with an information specialist (DL) to identify key words that represented the population (CKD) and the intervention (self-management). We searched a broad range of information sources including the following online databases: MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL Plus and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for published studies, with no limits on date (inception to October 2016), language, age or study design. We also searched Web of Science from 2006 to October 2016 to capture recently published meeting abstracts and summaries. Using the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology (CADTH) Grey Matters approach,18 we searched Google Canada, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) agencies (Canada, Australia, Ireland, UK and USA) and Clinical Trials databases (Biomed Central—ISRCTN Registry, US National Institutes of Health, ClinicalTrials.gov) during October 2016 with no language restrictions (online supplementary table 1). Our search strategy for grey literature was guided by the specific database (ie, Google search operators, website search filters) and was completed within a single session for each search strategy to ensure consistency due to the dynamic nature of the internet (online supplementary table 2). Two reviewers (BK and MD) also reviewed the reference lists of included studies, along with those identified in past systematic and integrative reviews of our research topic. We contacted authors of relevant protocols and conference abstracts to ascertain if their work and findings were published.

bmjopen-2017-019814supp001.pdf (252.2KB, pdf)

A study was included if the population involved adults with CKD (stages 1–5, non-dialysis, non-transplant). Self-management interventions included strategies, tools or resources in any delivery format (print, electronic, face to face and so on) that facilitated an individual’s ability to make lifestyle changes or to manage symptoms, treatment or the physical and psychosocial consequences inherent in living with CKD and other associated comorbidities. Interventions targeted only at selection of treatment for ESKD (ie, dialysis, kidney transplant) were excluded. Other self-management interventions or standard care were considered as a comparison. We included primary studies that used quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods. Systematic and integrative reviews were identified for the purpose of reviewing their included studies for potential relevant studies. We excluded case series, case studies, case reports, clinical practice guidelines, theses and opinion-driven reports (editorials, non-systematic or literature/narrative reviews).

Three reviewers (BK, MD and BH) performed an initial screen of titles and abstracts using a citation screening tool. To determine inter-rater reliability, a calibration exercise was performed by the three reviewers. Pilot testing a random sample of 50 citations achieved good agreement (kappa=0.79) at which point the three reviewers screened the remaining titles and abstracts. Two reviewers (BK and MD) followed a similar procedure for identifying relevant full text studies, with good agreement between the two reviewers (kappa=0.78). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and obtaining consensus between the three reviewers.

Charting, collating and summarising the data

We developed a data extraction form based on the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist.19 This checklist provides a template to structure accounts of an intervention (eg, goal of intervention, materials used, who delivered the intervention and how, where, when and how much and how well the intervention was delivered). We also used the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) data collection form20 to ensure we were comprehensive in extracting relevant study characteristics as outlined by Cochrane EPOC group. Study characteristics (eg, study design, country of origin, publication year), population characteristics (eg, CKD stage, comorbidities) and self-management intervention characteristics (eg, topics, format, target audience, providers, location, dose, duration and so on) were documented. For the study outcomes, the two reviewers (BK and MD) independently coded each outcome into categories identified by Grey et al (eg, behaviours, cognitions, physiological measures, symptoms, health status, healthcare and other).6 We pilot tested the form on a random sample of 10 eligible studies and once consensus between the two reviewers was reached, we independently abstracted data from the remaining eligible studies. Data were categorised and reported descriptively (ie, counts and frequencies). For qualitative studies, we identified the methodology and key concepts presented by the authors.

Consultation with patient partners

Patient partners were engaged throughout this work, specifically to provide input on the research question, search strategies (eg, grey literature sources) and reviewing the final results. The results were presented and discussed at the national Can-SOLVE CKD meeting.

Results

Search results

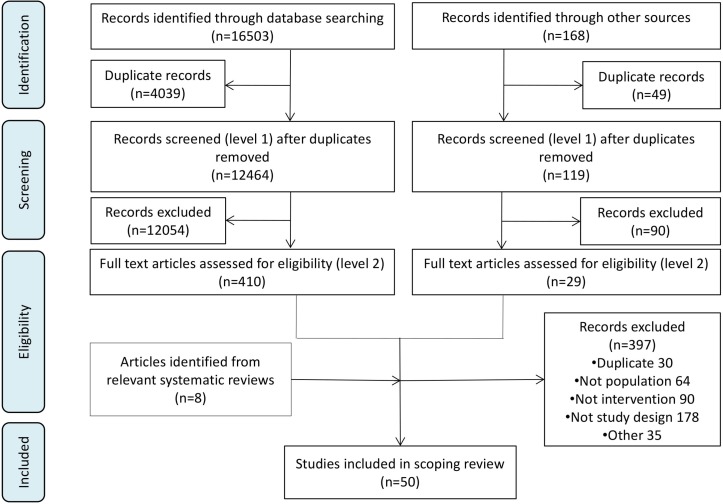

From 12 583 unique citations (figure 1), we included 50 full text studies.21–70

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

Description of studies

A summary of the 50 studies included in this review is provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in scoping review

| Characteristic | Studies (n=50) |

| Study design | |

| Randomised controlled trial | 19 |

| Pre-post test | 13 |

| Quasi-experimental (controlled/non-random) | 7 |

| Observational | 5 |

| Qualitative | 5 |

| Mixed methods | 1 |

| Origin of study | |

| USA | 10 |

| UK | 7 |

| Australia | 6 |

| Canada | 5 |

| Taiwan | 5 |

| Netherlands | 3 |

| Spain | 3 |

| Italy | 2 |

| Japan | 2 |

| New Zealand | 2 |

| Sweden | 2 |

| Brazil | 1 |

| Denmark | 1 |

| Korea | 1 |

| Year of publication | |

| 2012–2016 | 32 |

| 2007–2011 | 11 |

| Prior | 7 |

The most common study designs were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (38%). Non-RCTs consisted of quasi-experimental (14%), observational (10%), pre-post intervention (26%), qualitative (10%) and mixed methods (2%). The studies were conducted in 14 countries, including the USA (20%), UK (14%) and Australia (12%). Most studies were published in the last 5 years (64%).

Patient population characteristics

The target population in most studies was CKD (72%) and 15 studies mentioned CKD plus one or more associated comorbidities. The average ages of participants reported across studies were 50.2 to 74.3 years.

Description of self-management interventions

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of the self-management interventions. Five studies reported the same self-management intervention;21–25 therefore, 45 interventions were summarised. The most common intervention topic was diet/nutrition (64%) and the least common topics were symptom management and lifestyle (13% and 11%, respectively). The most frequent modes of delivering the intervention were face to face (80%), multiple (ie, more than one mode) (71%) and print (64%). Electronic was the least common delivery mode (16%). Interventions were administered by a variety of providers. The most common category of providers was ‘other’ (56%), which was made up of various types of health professionals and lay people. However, the most common identifiable group of providers were nursing professionals (49%). Patient volunteer/mentor was the least common (9%). The outpatient setting was the most common location for providing the self-management intervention (51%), and the inpatient setting was the least popular (2%). Many studies did not report the intervention language (53%), but 12 languages were represented and seven studies reported that they provided the intervention in multiple languages.

Table 2.

Overall characteristics of self-management interventions

| Variable | Intervention count (n=45) |

| Intervention topics | |

| Diet/nutrition | 29 |

| General CKD knowledge | 18 |

| Other (ie, advanced care planning, meditation) | 18 |

| Medication | 17 |

| Modalities | 13 |

| Physical activity | 13 |

| Comorbidities | 11 |

| Symptom management | 6 |

| Lifestyle | 5 |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Face to face (ie, group, one-on-one) | 36 |

| Multiple modes | 32 |

| 29 | |

| Distance (ie, telephone, email) | 13 |

| Digital (ie, DVD, PowerPoint, audio recording) | 8 |

| Electronic (ie, website, mobile application) | 7 |

| Type of providers | |

| Other* | 25 |

| Nurse/nurse practitioner | 22 |

| Dietitian | 14 |

| Multiple providers | 13 |

| Social worker | 6 |

| Physician/primary care physician | 6 |

| Nephrologist/nephrology fellows | 5 |

| Patient volunteer/mentor | 4 |

| Pharmacist | 1 |

| Location of intervention | |

| Outpatient | 23 |

| Not specified | 12 |

| Community (non-clinic)† | 10 |

| Patient home | 10 |

| Multiple locations | 7 |

| Inpatient | 1 |

| Intervention languages | |

| Not Specified | 24 |

| English | 10 |

| Multiple languages | 7 |

| Mandarin | 4 |

| Spanish | 3 |

| Taiwanese | 3 |

| Dutch | 2 |

| Cantonese | 1 |

| French | 1 |

| Greek | 1 |

| Italian | 1 |

| Japanese | 1 |

| Swedish | 1 |

| Vietnamese | 1 |

| Intervention development | |

| Use of framework or theory | 9 |

| Codesigned with patients | 4 |

*Other providers: Trained research assistant, lay health worker, Bengali worker, Educators (health, cook, diabetic), online tool, physician assistant, exercise physiologist, technician, psychologist, employment expert, instructor, interpreter, physiotherapist, patient, principal investigator.

†Community: gym, grocery store, "study room".

CKD, chronic kidney disease.

In terms of intervention development, only 20% of studies mentioned the use of evidence such as theories or frameworks. These included the transtheoretical model of behaviour change, social cognitive theory and chronic care model.26–30 Less than 1% of the studies involved patients in the design of the intervention, where patients were interviewed regarding intervention content.26 31–33

Description of quantitative study outcomes and results

Characteristics of the quantitative study outcomes are presented in table 3. Twenty-three (46%) studies measured physiological outcomes (ie, laboratory tests, body composition and so on). The least common outcomes reported by studies were health status and healthcare (each 10%) and symptoms (ie, fatigue) (4%). Table 4 summarises the details of the quantitative studies. We categorised the overall study results descriptively as improved, unchanged or worse. Many studies had more than one outcome measure (eg, one measure improved, another had no change) and they were reported as mixed results. Based on this method of categorization, 89 outcomes were reported, of which 61% improved, 20% had no change, 1% worsened and 13% had mixed results. Four of the results were reported as not applicable as the outcomes were not relevant. Of the 54 outcome categories that improved, 15 were cognition, 9 were physiological measures, 8 were behaviours, 8 were individual outcomes, 5 were health status, 4 were healthcare, 4 were intervention specific and 1 was symptom management.

Table 3.

Summary of quantitative study outcomes*

| Common outcomes | Description | Number of studies | Number of studies in which outcome improved |

| Physiological measures | Changes in laboratory tests, blood pressure, body composition, functional/performance tests and cardiovascular risk | 23 | 9 |

| Cognitions | Changes in general CKD knowledge, self-efficacy, self-management, motivation, perceived stress, anxiety and fear | 21 | 15 |

| Behaviours | Adherence to diet, medication, physical activity, sleep, blood pressure control | 13 | 8 |

| Individual outcomes | QOL, well-being and general satisfaction | 11 | 8 |

| Intervention specific | Reporting of general concepts regarding feasibility of intervention, enjoyment and interest in intervention | 9 | 4 |

| Healthcare | Measurements of cost effectiveness, healthcare utilisation and access | 5 | 4 |

| Health status | Measurements of morbidity and mortality (ie, time to dialysis, survival, all-cause mortality) | 5 | 5 |

| Symptoms | Changes in overall symptoms (ie, pain, fatigue) | 2 | 1 |

*Based on primary and distal outcomes from Grey et al.6

CKD, chronic kidney disease; QOL, quality of life.

Table 4.

Summary of quantitative studies

| Study and year (Reference) |

Design | Target population | Study size Age (years) |

Intervention topic(s) | Provider(s) | Delivery format | Description of intervention | Study outcomes | Study results |

| RCT | |||||||||

| Binik et al (1993)34 | RCT | Pre-RRT CKD (creatinine>350 μmol/L and rising rapidly) | 204 (E=87, C=92, not part of education=25) Age: 50.2 |

|

Trained research assistant |

|

‘Enhanced education’:

Comparator: standard care |

Health status:

|

|

| Gillis et al (1995)35 | RCT | CKD 3–5 | 840 (unclear) Age: NR |

|

Dietician |

|

‘Modification of diet in renal disease’:

Comparator: standard protein diet |

Cognitions:

|

|

Individual outcomes:

|

|

||||||||

|

Devins et al (2003)36 |

RCT | CKD (creatinine<300 μmol/L and deemed to need RRT in 6–18 months) |

297 (E=149, C=148) Age: 58.6 |

|

Social worker |

|

‘Psychoeducation’:

Comparator: standard care |

Health status:

|

|

|

Devins et al (2005)37 |

RCT | CKD with progressive reduction in kidney function |

335 (E=172, C=163) Age: 47.4–53.9 |

|

Health educator |

|

‘Psychoeducation session’:

Comparator: standard care |

Health status:

|

|

|

Campbell et al (2008)38 |

RCT | CKD 4–5 | 47 (E=24, C=23) Age: 68.5–72.6 |

|

Dietician |

|

‘Individual nutritional counselling’:

Comparator: standard care |

Individual outcomes:

|

|

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

|

Byrne et al (2011)26 |

RCT | CKD 1–4+HTN | 81 (E=40, C=41) Age: 62.8–65.4 |

|

Nurse |

|

‘Structured education session’:

Comparator: standard care |

Intervention specific:

|

|

|

Chen et al (2011)39 |

RCT | CKD 3–5 | 54 (E=27, C=27) Age: 68.2 |

|

Nurse, dietician, nephrologist, peers, volunteers |

|

‘Self-management Support’:

Comparator: standard care |

Physiological measures:

|

|

Health status:

|

|

||||||||

| Flesher et al (2011)40 | RCT | CKD 3–4+HTN | 40 (E=23, C=17) Age: 63.4 |

|

Nurse, exercise physiologist, dietician, cook educator |

|

‘Cooking and exercise class’:

Comparator: standard care |

Physiological measures:

|

|

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

|

Joboshi et al (2012)41 |

RCT | CKD | 31 (E=19, C=12) Age: 69.8 |

|

Nurse |

|

‘EASE (encourage autonomous self-enrichment) programme’:

Comparator: standard care |

Cognitions:

|

|

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

| Williams et al (2012)42 | RCT | CKD 2–4 (diabetic kidney disease)+DM+HTN |

75 (E=39, C=41) Age: 67 |

|

Nurse |

|

‘Multifactorial intervention’:

Comparator: standard care |

Physiological measures:

|

|

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

|

Williams et al (2012)43 |

RCT | CKD 2–4+DM+ cardiovascular disease |

78 (E=40, C=38) Age: 74.31 |

|

Nurse, interpreter |

|

‘Self-efficacy Medication Intervention (SEM)’:

Comparator: standard care |

Intervention specific:

|

|

Cognitions:

|

|

||||||||

Healthcare:

|

|

||||||||

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

Individual outcomes:

|

|

||||||||

| de Brito-Ashurst et al (2013)44 | RCT | CKD 3–5+HTN (BP>130/80) +Bengali population |

56 (E=28, C=28) Age: 55.7–60.7 |

|

Dietician and Bengali worker |

|

‘Diet advice’:

Comparator: standard care |

Physiological measures:

|

|

|

Paes-Barreto et al (2013)45 |

RCT | CKD 3–5 | 89 (E=43, C=46) Age: 63.4 |

|

Dietician |

|

‘Nutrition education programme’:

Comparator: standard care |

Behaviours:

|

|

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

|

Blakeman et al (2014)46 |

RCT | CKD 3 | 436 (E=215, C=221) Age: 72.1 |

|

Lay health worker |

|

‘Information and telephone-guided access to community services’:

Comparator: standard care |

Cognitions:

|

|

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

Individual outcomes:

|

|

||||||||

|

McManus et al (2014)47 |

RCT | HTN (BP>130/80) +CKD3 or DM or CHD |

555 (E=277, C=278) Age: 69.3–69.6 |

|

General practitioner, patient |

|

‘Self-monitoring of BP and self-titration of medications’:

Comparator: standard care |

Physiological measures:

|

|

Healthcare:

|

|

||||||||

Symptom mgmt.:

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Park et al (2014)48 | RCT | CKD3+HTN+ African-American |

15 Age: 58.7 |

|

Principle investigator, patient |

|

‘Mindfulness meditation (MM)’

Comparator: BP education |

Physiological measures:

|

|

|

Howden et al (2015)49 |

RCT | CKD 3–4 and >1 uncontrolled cardiovascular risk factor |

72 (E=36, C=36) Age 60.2–62.0 |

|

Nurse practitioner, social worker, exercise physiologist, dietician, psychologist, diabetes educator |

|

‘Exercise training and lifestyle intervention’:

Comparator: standard care |

Physiological measures:

|

|

|

Leehey et al (2016)50 |

RCT | CKD 2–4+DM2+BMI>30+ persistent proteinuria |

36 (Exercise+diet = 18, Diet=18) Age: 66 |

|

Personal trainer |

|

‘Structured exercise programme’:

Comparator: diet counselling only |

Physiological measures:

|

|

|

Montoya et al (2016)30 |

RCT | CKD 4 | 30 (E=16, C=14) Age: 67.9–68.3 |

|

Nephrologist, nurse practitioner, dietician, social worker |

|

‘Nurse practitioner facilitated CKD group visit’:

Comparator: standard care |

Cognitions:

|

|

Individual outcomes:

|

|

||||||||

| Non-RCT | |||||||||

| Robinson et al (1988)51 | Obs | CKD | 25 Age: NR |

|

NR |

|

‘Renal Bingo’:

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

Intervention specific:

|

|

||||||||

|

Klang et al (1998)52 |

QE | CKD 4–5 | 56 (E=28, C=28) Age: 54–58 |

|

Nurse, physician, social worker, dietician, physiotherapist |

|

‘Pre-dialysis patient education’:

Comparator: standard care |

Individual outcomes:

|

|

|

Cupisiti et al (2002)53 |

PP | CKD 3b-5 | 20 Age: NR |

|

NR |

|

‘Vegetarian diet’:

Comparator: conventional protein diet |

Individual outcomes:

|

|

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

|

Gutiérrez Vilaplana et al (2007)57 |

PP | CKD | 24 Age: 64.5 |

|

Nurse, patient volunteers |

|

‘Education Intervention’

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

Intervention specific:

|

|

||||||||

|

Pagels et al (2008)55 |

Obs | CKD | 58 Age: 65 |

|

Nurse |

|

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

Intervention specific:

|

|

||||||||

| Yen et al (2008)56 | PP | CKD 3 | 66 Age: 67.4 |

|

Nephrologist, nurse, dietician, social worker |

|

‘Educational intervention’:

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

|

Gutiérrez-Vilaplana et al (2009)54 |

PP | CKD 4–5 | 41 Age: 60.56 |

|

Nurse, physician, technician, three expert patients |

|

‘Teaching group’:

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

|

Wu et al (2009)58 |

QE | CKD 3–5 | 573 (E=287, Cohort=286) Age: 63.4 |

|

Nurse, social worker, dietician, HD/PD patient volunteers, physicians |

|

‘Multidisciplinary predialysis education (MPE)’:

Comparator: standard care |

Health status:

|

|

Healthcare:

|

|

||||||||

| Wierdsma et al (2011)59 | QE | CKD | 54 (E=28, C=26) Age: 55–59 |

|

Nurse practitioner |

|

‘Motivational interviewing’:

Comparator: standard care |

Cognitions:

|

|

|

Aguilera Florez et al (2012)60 |

Obs | CKD | 19 Age: 58 |

|

Nurse, physiotherapist, dietician, pharmacist, psychologist, coordinators, nephrologist, patient mentors |

|

‘Escuela ERCA’:

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

Individual outcomes:

|

|

||||||||

|

Choi et al (2012)61 |

QE | CKD 1–5 | 61 (E=31, C=30) Age: 53.93–58.33 |

|

Physician, nurse, dietician |

|

‘Face-to-face SM programme’:

Comparator: general maintenance |

Cognitions:

|

|

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

| Kao et al (2012)27 | QE | CKD 1–4 | 94 (E=45, C=49) Age: 73.17 |

|

Instructor |

|

‘Exercise education intervention’:

Comparator: standard care |

Behaviours:

|

|

Cognitions:

|

|

||||||||

Symptom management:

|

|

||||||||

| Diamantidis et al (2013)62 | PP | CKD 3–5 | 108 Age: 64 |

|

Online tool |

|

‘Disease-specific safety information’:

Comparator: none |

Intervention specific:

|

|

| Kazawa et al (2013)31 | PP | CKD 3–4 (diabetic nephropathy) | 30 Age: 67 |

|

Nurse |

|

‘SM skills programme’:

Comparator: none |

Individual outcomes:

|

|

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

| Lin et al (2013)63 | PP | CKD 1-3a | 37 Age 67.42 |

|

Nurse |

|

‘SM programme’:

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

Physiological measures:

|

|

||||||||

| Murali et al (2013)28 | PP | CKD 4 | 12 Age: 68 |

|

Online tool |

|

‘Dietary assessment and evaluation tool’:

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

Intervention specific:

|

|

||||||||

| Nauta et al (2013)32 | PP | CKD | 22 Age: 55.2–59.8 |

|

Online tool |

|

‘Lifestyle management tool’:

|

Cognitions:

|

|

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

| Thomas and Bryar (2013)33 | MM | Diabetic nephropathy (DM+microalbuminuria) | 176 (E=116, C=60) Age: NR |

|

NR |

|

‘SM package’:

Comparator: standard care |

Physiological measures:

|

|

| Walker et al (2013)64 | PP | CKD with high risk of Progression+DM2+HTN + albuminuria | 52 Age: 57.5 |

|

Nurse, nurse practitioner |

|

‘Nurse practitioner intervention in primary care setting’:

Comparator: none |

Behaviours:

|

|

| Wright Nunes et al (2013)65 | QE | CKD 1–5 | 556 (E=155, Cohort=401) Age: 57 |

|

Nephrology fellows |

|

‘Physician-delivered education too’

Comparator: ‘historical group’—who developed sheet |

Cognitions:

|

|

Intervention specific:

|

|

||||||||

|

Walker et al (2014)24 |

PP | CKD with high risk of Progression+DM2+HTN + albuminuria | 52 Age: 57.5 |

|

Nurse, nurse practitioner |

|

|

Physiological measures:

|

|

Cognitions:

|

|

||||||||

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

| Enworom et al (2015)66 | QE | CKD 1–4 | 49 (E=25, C=24) Age: 73 |

|

Nurse practitioner, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialist |

|

‘Kidney Disease Education (KDE)’

Comparator: no KDE |

Physiological measures:

|

|

Cognitions:

|

|

||||||||

| Vann et al (2015)29 | PP | CKD 3b-4 | 9 Age: mean NR |

|

Nurse practitioner |

|

‘CKD Education Programme’

Comparator: none |

Cognitions:

|

|

Behaviours:

|

|

||||||||

|

Cupisiti et al (2016)67 |

Obs | CKD 3b-5 | 823 (E=305, C=518) Age: 69–74 |

|

Dietician |

|

‘Nutritional Treatment’

Comparator: standard care |

Physiological measures:

|

|

Healthcare:

|

|

||||||||

Individual outcomes:

|

|

||||||||

| Ong et al (2016)68 | PP | CKD 4–5 | 45 Age: 59.4 |

|

Mobile application |

|

‘Smartphone based SM system’

Comparator: none |

Physiological measures:

|

|

Intervention specific:

|

|

||||||||

| Penaloza-Ramos et al (2016)25 | Obs | HTN (BP>130/80)+CKD stage three or CVA/TIA or DM or MI or angina or CABG | NR Age: NA |

|

General practitioner, patient |

|

|

Healthcare:

|

|

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Outcome improved post intervention.

Outcome improved post intervention.

Outcome worsened post intervention.

Outcome worsened post intervention.

Outcome unchanged post intervention.

Outcome unchanged post intervention.

Outcome had mixed results (some improved and/or some worsened and/or some did not change).

Outcome had mixed results (some improved and/or some worsened and/or some did not change).

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; C, control; CALD, culturally and linguistically diverse; CHD, coronary heart disease; CHEERS, Controlling Hypertension: Education and Empowerment Renal Study; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; E, experimental; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESA, erthropoiesis stimulating agents; ESRD, early stage renal disease; HTN, hypertension; MM, mixed methods; NR, not reported; Obs, observational; PP, pre-post intervention; QE, quasi-experimental; QOL, quality of life; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SM, self-management; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Description of qualitative study outcomes and results

Table 5 summaries the findings from six qualitative studies that explored patient perspectives, one of these being a mixed methods study. All studies used semistructured interviews and one also used a questionnaire. The aims of all these studies were to examine patient perspectives’ regarding the self-management interventions they were involved in. Due to the variety of interventions (eg, intervention topics, delivery mode and providers of the intervention), it was difficult to summarise findings into meaningful categories. Overall, patients highlighted that interventions needed to be individualised and tailored to their specific situations and preferences (eg, awareness of having CKD, stage of CKD, knowledge of the disease, access to resources and so on).

Table 5.

Summary of qualitative studies

| Study (Reference) |

Target population | Number of participants | Aim/Intervention | Methods | Summary of findings |

| Blickem et al 21 | CKD stage 3 | 20 | ‘To explore the experience of patient-led assessment for network support (PLANS) from the perspectives of participants and telephone support workers.’ (p. 1) Intervention: see table 4 Blakeman et al 46 |

Interviews and focus groups: no analytic methodology discussed |

|

| Heiden et al 69 | CKD predialysis, dialysis, transplant | 5 | To identify participant’s perspective regarding a ‘web application prototype to help make decisions regarding diet restrictions and phosphate binder dosage.’ (p. 544) Intervention: Website tool for patients that included three components—diet/fluid education; diet registry and phosphate binder decision support tool. |

Interviews: no analytic methodology discussed |

|

| Jansen et al 70 | CKD stages 4–5 | 7 | Feasibility of ‘a psychosocial intervention to assist ESRD patients and their partners in integrating renal disease and treatment into daily activities, primary work and thereby increasing autonomy.’ (p. 280) Intervention: group teaching and handbook regarding coping strategies and goals based on self-regulation, social learning and self-determination theories. |

Interviews: no analytic methodology discussed |

|

| Thomas et al 33 | Type 1 or 2 DM with microalbuminuria | 5 (3 face-to-face interviews) | To evaluate ‘whether patients understood the content of the pack and whether they could make any recommendations.’ (p. 275) Intervention: see table 4 Thomas et al 30 |

Questionnaire and interview: no analytic methodology discussed |

|

| Williams et al 22 | CKD stages 2–4 with diabetes and cardiovascular disease | 26 | ‘Examine the perceptions of a group of CALD participants with comorbid diabetes, chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease … using an intervention to influence their medication self-efficacy.’ (p. 1271) Intervention: see table 4 Williams et al 43 |

Interviews: Ritchie and Spencer thematic approach |

|

| Williams et al 23 | CKD stages 2–4, with coexisting diabetes and hypertension | 39 | Individual perceptions of a ‘telephone call using a motivational interviewing approach to improve medication adherence in participants with coexisting diabetes, CKD and hypertension.’ (p. 472) Intervention: see table 4 Williams et al 42 |

Interviews: Ritchie and Spencer thematic approach |

|

CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review involving patients as research partners to identify and summarise self-management interventions for adults with CKD. The scoping review methodology enabled us to systematically summarise a broad range of self-management interventions and describe their features. We identified 50 studies that investigated self-management interventions for adults with CKD, with considerable variation in interventions, outcomes assessed and results obtained (ie, some improved and/or some worsened and/or some did not change). We found that self-management interventions for CKD is an emerging area with most studies published within the last 5 years which may be related to the growing recognition of the importance of incorporating patients and their families in managing their disease to improve outcomes.7

Our findings are similar to prior reviews reporting that the design of self-management interventions for CKD has not been theoretically driven and they have been predominately designed by healthcare professionals without input from patients.13 14 Person-centred care is changing how healthcare professionals deliver care to patients, but more importantly how patients and their families are actively involved in self-managing their chronic conditions.71 Engaging patients by having them co-design self-management interventions will ensure that patient preferences based on their values, culture and psychosocial needs will be addressed in the self-management intervention.12–14 Through our current national partnership with patients, researchers and clinicians, we have the opportunity to obtain patient perspectives, along with incorporating a behaviour change theory to inform the future design of a self-management intervention for CKD.

Only 28% of studies that we identified included patients with CKD plus other comorbidities, despite the common presence of comorbidities in this patient population. Less than one-quarter of included studies provided information on how to manage comorbid conditions such as tracking lab results and symptom management. This highlights the need to consider ‘whole person care’, where the self-management intervention needs to encompass the physical, mental and emotional needs of the patient72 73 that are important to them as well as meeting the individuals desires by collaboration between relevant providers.71

Forty-five different self-management interventions were identified, with one or more topics presented in a variety of formats and by a variety of providers. Symptom management and lifestyle topics were not included in many of the interventions. Based on prior work,3 non-dialysis patients with CKD have indicated that these were important topics for them in managing their CKD with an aim to slow the progression of CKD and will be important to consider in the development of future interventions. Face to face was the most common delivery format while electronic (internet or mobile application) was least common, with many studies reporting multiple formats (ie, face to face and printed materials). With the expansion of electronic platforms for supporting patients and providers in the uptake of evidence-based care, there is the potential to use an electronic format to support patients in self-managing their CKD and other comorbidities.74 It is worth noting that there was variability in duration and frequency of face to face encounters, from a single session to multiple sessions over weeks to months. While varied options for in-person delivery is good if it meets the needs of the patients and their families, it may not be feasible on a larger scale due to the resources required. Only five studies looked at self-management healthcare cost-effectiveness, healthcare utilisation and access, each measuring different end-points with mixed results. Future self-management interventions should include the essential principles to self-management (eg, accessing relevant health information, adhering to multiple treatment protocols, changing health behaviours, shared decision making with healthcare providers),7 75 along with evaluation of the cost-effectiveness and resource utilisation.

The majority of studies did not identify a single primary outcome but rather multiple outcomes. We found that physiological outcomes (ie, blood pressure) were the most commonly reported and symptoms were the least mentioned. These findings demonstrate the lack of patient-driven outcomes that may be important to them, for example, a patient’s individual health goals across a variety of dimensions (ie, symptoms, mobility, social and role function in the family or community) that could possibly maximise their quality of life. Work by Tong et al (2015) highlights this concept, where patients with CKD are more interested in treatment choices that influence non-traditional clinical outcomes such as impact on family and lifestyle.72 A holistic approach should be considered where mental and psychosocial outcomes are investigated, rather than just physiological endpoints.

Our findings from the qualitative studies looking at patient perspectives are inconclusive because of the limited number of studies and the heterogeneity of the interventions. Havas et al 12 similarly reported a lack of research related to patient perspectives on self-management in CKD.12 There is also a lack of qualitative studies overall, which could provide valuable information regarding attitudes and challenges of self-management interventions from the perspective of both providers and patients.

Strengths of our study include the comprehensive nature of our search, inclusion of all study designs and consideration of self-management features that have not been investigated previously. We also engaged patient partners in determining the research question, advising us on search terms, grey literature sources and reviewing the results to ensure we captured and reported the data meaningfully. One of the main limitations was the challenge in synthesising the data given its heterogeneous nature. To address this challenge, the two reviewers used two standardised tools TIDieR19 and the EPOC tool20 to independently extract data and independently coded the outcomes into categories using the revised Self-and Family Management Framework.6 Also, we were unable to assess the self-management outcomes in terms of sustained changes in behaviour, physiological and health status. A final limitation was our inability to draw conclusions regarding the most effective self-management intervention for adult patients with CKD, keeping in mind that our aim was to review the breadth of the current literature and present the gaps that exist.

Overall, we found considerable variation in self-management interventions for adults with CKD with respect to their content and delivery as well as the outcomes assessed and results obtained. Major gaps in the literature include the lack of patient engagement in the design of the self-management intervention, along with the lack of a behavioural change theory to inform their design. Our future research will incorporate intervention frameworks to codevelop and evaluate a self-management intervention based on a sound behavioural theory involving our national patient partners, specialists, primary care providers and decision makers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Diane Lorenzetti for providing support and direction regarding search strategies. We would also like to thank Sarah Gil in assisting us with acquiring full text studies.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the research idea and study design. MD and BKK acquired the data. MD, BKK and BRH completed data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting and revisions. They also read and approved the final manuscript. BRH and PR provided mentorship.

Funding: MD is a recipient of the 2016 Alberta SPOR Graduate Studentships in Patent- Oriented Research. Alberta SPOR Graduate Studentships in Patient-Oriented Research are jointly funded by Alberta Innovates and the Canadian Institute of Health Research. BRH is supported by the Roy and Vi Baay Chair in Kidney Research, Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR).

Disclaimer: The funding organisations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; data collection, analysis and interpretation or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The following data will be available, study protocol and analysis plan, to anyone who wishes to access them and will be available immediately following publication from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Arora P, Vasa P, Brenner D, et al. Prevalence estimates of chronic kidney disease in Canada: results of a nationally representative survey. CMAJ 2013;185:e417–23. 10.1503/cmaj.120833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Guthrie B, et al. Comorbidity as a driver of adverse outcomes in people with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2015;88:859–66. 10.1038/ki.2015.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hemmelgarn BR, Pannu N, Ahmed SB, et al. Determining the research priorities for patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis. Nephrology, dialysis . Transplantation 2017;32:847–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tong A, Chando S, Crowe S, et al. Research priority setting in kidney disease: a systematic review. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2015;65:674–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011;43:no–64. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grey M, Schulman-Green D, Knafl K, et al. A revised Self- and Family Management Framework. Nurs Outlook 2015;63:162–70. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Novak M, Costantini L, Schneider S, et al. Approaches to self-management in chronic illness. Semin Dial 2013;26:188–94. 10.1111/sdi.12080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lopez-Vargas PA, Tong A, Howell M, et al. Educational interventions for patients with CKD: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;68:353–70. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mason J, Khunti K, Stone M, et al. Educational interventions in kidney disease care: A systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;51:933–51. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee MC, Wu SV, Hsieh NC, et al. Self-management programs on eGFR, depression, and quality of life among patients with chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. Asian Nurs Res 2016;10:255–62. 10.1016/j.anr.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin MY, Liu MF, Hsu LF, et al. Effects of self-management on chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;74:128–37. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Havas K, Bonner A, Douglas C. Self-management support for people with chronic kidney disease: Patient perspectives. J Ren Care 2016;42:7–14. 10.1111/jorc.12140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bonner A, Havas K, Douglas C. Self-management programmes in stages 1-4 chronic kidney disease: A literature review. J Ren Care 2014;40:194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Welch JL, Johnson M, Zimmerman L, et al. Self-management interventions in stages 1 to 4 chronic kidney disease: an integrative review. West J Nurs Res 2015;37:652–78. 10.1177/0193945914551007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levin A. Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD). CIHR Grant 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). Grey Matters: A practical search tool for evidence-based medicine. https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters (accessed Sep 2015).

- 19. Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist. http://www.equator-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/TIDieR-Checklist-PDF (accessed Sept 2016).

- 20. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) data collection.http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors (accessed Oct 2016).

- 21. Blickem C, Kennedy A, Jariwala P, et al. Aligning everyday life priorities with people’s self-management support networks: an exploration of the work and implementation of a needs-led telephone support system. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:262 10.1186/1472-6963-14-262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Williams A, Manias E, Cross W, et al. Motivational interviewing to explore culturally and linguistically diverse people’s comorbidity medication self-efficacy. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1269–79. 10.1111/jocn.12700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams A, Manias E. Exploring motivation and confidence in taking prescribed medicines in coexisting diseases: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2014;23:471–81. 10.1111/jocn.12171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Walker RC, Marshall MR, Polaschek NR. A prospective clinical trial of specialist renal nursing in the primary care setting to prevent progression of chronic kidney: a quality improvement report. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:155 10.1186/1471-2296-15-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Penaloza-Ramos MC, Jowett S, Mant J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of self-management of blood pressure in hypertensive patients over 70 years with suboptimal control and established cardiovascular disease or additional cardiovascular risk diseases (TASMIN-SR). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:902–12. 10.1177/2047487315618784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Byrne J, Khunti K, Stone M, et al. Feasibility of a structured group education session to improve self-management of blood pressure in people with chronic kidney disease: an open randomised pilot trial. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000381 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kao Yu‐Hsiu, Huang Yi‐Ching, Chen Pei‐Ying, Kao Y, Huang Y, Chen P, et al. The effects of exercise education intervention on the exercise behaviour, depression, and fatigue status of chronic kidney disease patients. Health Educ 2012;112:472–84. 10.1108/09654281211275827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murali S, Arab L, Vargas R, et al. Internet-based tools to assess diet and provide feedback in chronic kidney disease stage IV: a pilot study. J Ren Nutr 2013;23:e33–e42. 10.1053/j.jrn.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vann JC, Hawley J, Wegner S, et al. Nursing intervention aimed at improving self-management for persons with chronic kidney disease in North Carolina Medicaid: A pilot project. Nephrol Nurs J 2015;42:239–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Montoya V, Sole ML, Norris AE. Improving the care of patients with chronic kidney disease using group visits: a pilot study to reflect an emphasis on the patients rather than the disease. Nephrol Nurs J 2016;43:207–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kazawa K, Moriyama M. Effects of a self-management skills-acquisition program on pre-dialysis patients with diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Nurs J 2013;40:141–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nauta J, van der Boog J, Slegten J, 2013. Web-based lifestyle management for chronic kidney disease. eTELEMED 2013, The Fifth International Conference on eHealth, Telemedicine, and Social Medicine, Nice, France 141–6 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas N, Bryar R. An evaluation of a self-management package for people with diabetes at risk of chronic kidney disease. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2013;14:270–80. 10.1017/S1463423612000588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Binik YM, Devins GM, Barre PE, et al. Live and learn: patient education delays the need to initiate renal replacement therapy in end-stage renal disease. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993;181:371–6. 10.1097/00005053-199306000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gillis BP, Caggiula AW, Chiavacci AT, et al. Nutrition intervention program of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study: a self-management approach. J Am Diet Assoc 1995;95:1288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Devins GM, Mendelssohn DC, Barré PE, Binik YM, et al. Predialysis psychoeducational intervention and coping styles influence time to dialysis in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;42:693–703. 10.1016/S0272-6386(03)00835-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Devins GM, Mendelssohn DC, Barré PE, et al. Predialysis psychoeducational intervention extends survival in CKD: a 20-year follow-up. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;46:1088–98. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Campbell KL, Ash S, Bauer JD. The impact of nutrition intervention on quality of life in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Clin Nutr 2008;27:537–44. 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen SH, Tsai YF, Sun CY, et al. The impact of self-management support on the progression of chronic kidney disease-a prospective randomized controlled trial. Nephrology, Dialysis. Transplantation 2011;26:3560–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Flesher M, Woo P, Chiu A, et al. Self-management and biomedical outcomes of a cooking, and exercise program for patients with chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 2011;21:188–95. 10.1053/j.jrn.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Joboshi H, Oka M, Takahashi S, et al. Effects of the EASE program in chronic kidney disease education: A randomized controlled trial to evaluate self-management. J Jpn Acad Nurs Sci 2012;32:21–9. 10.5630/jans.32.1_21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Williams A, Manias E, Walker R, et al. A multifactorial intervention to improve blood pressure control in co-existing diabetes and kidney disease: a feasibility randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:2515–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05950.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Williams AM, Liew D, Gock H, et al. Working with CALD groups: testing the feasibility of an intervention to improve medication self- management in people with kidney disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Renal Society of Australasia Journal 2012;8:62–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Brito-Ashurst I, Perry L, Sanders TA, et al. The role of salt intake and salt sensitivity in the management of hypertension in South Asian people with chronic kidney disease: a randomised controlled trial. Heart 2013;99:1256–60. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paes-Barreto JG, Silva MI, Qureshi AR, et al. Can renal nutrition education improve adherence to a low-protein diet in patients with stages 3 to 5 chronic kidney disease? J Ren Nutr 2013;23:164–71. 10.1053/j.jrn.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Blakeman T, Blickem C, Kennedy A, et al. Effect of information and telephone-guided access to community support for people with chronic kidney disease: randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e109135 10.1371/journal.pone.0109135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McManus RJ, Mant J, Haque MS, et al. Effect of self-monitoring and medication self-titration on systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: the TASMIN-SR randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:799 10.1001/jama.2014.10057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Park J, Lyles RH, Bauer-Wu S. Mindfulness meditation lowers muscle sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in African-American males with chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2014;307:R93–R101. 10.1152/ajpregu.00558.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Howden EJ, Coombes JS, Strand H, Douglas B, et al. Exercise training in CKD: efficacy, adherence, and safety. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:583–91. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leehey DJ, Collins E, Kramer HJ, et al. Structured exercise in obese diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled Trial. Am J Nephrol 2016;44:54–62. 10.1159/000447703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Robinson JA, Robinson KJ, Lewis DJ. Games: a motivational educational strategy. Anna J 1988;15:277–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klang B, Björvell H, Berglund J, et al. Predialysis patient education: effects on functioning and well-being in uraemic patients. J Adv Nurs 1998;28:36–44. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cupisti A, Morelli E, Meola M, et al. Vegetarian diet alternated with conventional low-protein diet for patients with chronic renal failure. J Ren Nutr 2002;12:32–7. 10.1053/jren.2002.29595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gutiérrez Vilaplana JM, Zampieron A, Craver L, et al. Evaluation of psychological outcomes following the intervention ’teaching group': study on predialysis patients. J Ren Care 2009;35:159–64. 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2009.00113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pagels A, Wang M, Magnusson A, et al. Using patient diary in chronic illness care: Evaluation of a tool promoting self-care. Vard I Norden 2008;28:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yen M, Huang JJ, Teng HL. Education for patients with chronic kidney disease in Taiwan: a prospective repeated measures study. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:2927–34. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gutiérrez Vilaplana Josep Mª, Samsó Piñol E, Cosi Ponsa J, et al. Evaluación de la intervención enseñanza: grupo en la consulta de enfermedad renal crónica avanzada. Revista de la Sociedad Española de Enfermería Nefrológica 2007;10:280–5. 10.4321/S1139-13752007000400004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wu IW, Wang SY, Hsu KH, et al. Multidisciplinary predialysis education decreases the incidence of dialysis and reduces mortality--a controlled cohort study based on the NKF/DOQI guidelines. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:3426–33. 10.1093/ndt/gfp259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wierdsma J, van Zuilen A, van der Bijl J. Self-efficacy and long-term medication use in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care 2011;37:158–66. 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Aguilera Florez AI, Velasco MP, Romero LG, et al. A little-used strategy in caring for patients with chronic kidney disease: Multidisciplinary education of patients and their relatives. Enferm Nefrol 2012;15:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Choi ES, Lee J. Effects of a face-to-face self-management program on knowledge, self-care practice and kidney function in patients with chronic kidney disease before the renal replacement therapy. J Korean Acad Nurs 2012;42:1070–8. 10.4040/jkan.2012.42.7.1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Diamantidis CJ, Fink W, Yang S, et al. Directed use of the internet for health information by patients with chronic kidney disease: prospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e251 10.2196/jmir.2848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lin CC, Tsai FM, Lin HS, et al. Effects of a self-management program on patients with early-stage chronic kidney disease: a pilot study. Appl Nurs Res 2013;26:151–6. 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Walker R, Marshall MR, Polaschek NR. Improving self-management in chronic kidney disease: a pilot study. Renal Society of Australasia Journal 2013;9:116–25. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wright Nunes J, Greene JH, Wallston K, et al. Pilot study of a physician-delivered education tool to increase patient knowledge about CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;62:23–32. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Enworom CD, Tabi M. Evaluation of kidney disease education on clinical outcomes and knowledge of self-management behaviors of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Nurs J 2015;42:363–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cupisti A, D’Alessandro C, Di Iorio B, et al. Nutritional support in the tertiary care of patients affected by chronic renal insufficiency: report of a step-wise, personalized, pragmatic approach. BMC Nephrol 2016;17:124 10.1186/s12882-016-0342-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ong SW, Jassal SV, Miller JA, et al. Integrating a Smartphone-Based Self-Management System into usual care of advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:1054–62. 10.2215/CJN.10681015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Heiden S, Buus AA, Jensen MH, et al. A diet management information and communication system to help chronic kidney patients cope with diet restrictions. Stud Health Technol Inform 2013;192:543–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jansen DL, Heijmans M, Rijken M, et al. The development of and first experiences with a behavioural self-regulation intervention for end-stage renal disease patients and their partners. J Health Psychol 2011;16:274–83. 10.1177/1359105310372976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Brummel‐Smith K, Butler D, Frieder M, et al. The American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered, C. (2016). Person‐centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Chadban S, et al. Patients' experiences and perspectives of living with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:689–700. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hutchinson TA, Hutchinson N, Arnaert A. Whole person care: encompassing the two faces of medicine. CMAJ 2009;180:845–6. 10.1503/cmaj.081081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Trisolini M, Roussel A, Zerhusen E, et al. Activating chronic kidney disease patients and family members through the Internet to promote integration of care. Int J Integr Care 2004;4:e17 10.5334/ijic.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ong SW, Jassal SV, Porter E, et al. Using an electronic self-management tool to support patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD): a CKD clinic self-care model. Semin Dial 2013;26:195–202. 10.1111/sdi.12054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019814supp001.pdf (252.2KB, pdf)