Abstract

Objectives

To explore the roles of community cadres in improving access to and retention in care for PMTCT (prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV) services in the context of PMTCT Option B+ treatment scale-up in high burden low-income and lower-middle income countries.

Design/Methods

Qualitative rapid appraisal study design using semistructured in-depth interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) between 8 June and 31 July 2015.

Setting and participants

Interviews were conducted in the offices of Ministry of Health Staff, Implementing partners, district offices and health facility sites across four low-income and lower-middle income countries: Cote D’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Malawi and Uganda. A range of individual interviews and FGDs with key stakeholders including Ministry of Health employees, Implementation partners, district management teams, facility-based health workers and community cadres. A total number of 18, 28, 31 and 83 individual interviews were conducted in Malawi, Cote d’Ivoire, DRC and Uganda, respectively. A total number of 15, 9, 10 and 16 mixed gender FGDs were undertaken in Malawi, Cote d’Ivoire, DRC and Uganda, respectively.

Results

Community cadres either operated solely in the community, worked from health centres or in combination and their mandates were PMTCT-specific or included general HIV support and other health issues. Community cadres included volunteers, those supported by implementing partners or employed directly by the Ministry of Health. Their complimentary roles along the continuum of HIV care and treatment include demand creation, household mapping of pregnant and lactating women, linkage to care, infant follow-up and adherence and retention support.

Conclusions

Community cadres provide an integral link between communities and health facilities, supporting overstretched health workers in HIV client support and follow-up. However, their role in health systems is neither standardised nor systematic and there is an urgent need to invest in the standardisation of and support to community cadres to maximise potential health impacts.

Keywords: public health, human resource management, public health, community cadres

Strengths and limitations of the study.

Inclusion of four diverse countries in Southern, Central and West Africa, at different stages with implementation of PMTCT (prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV) Option B+. The extent of involvement of community cadres in PMTCT in each country reflects this with Malawi and Uganda having more integrated and institutionalised approaches compared with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cote d’Ivoire, which are at an earlier stage of implementation.

Qualitative data collection undertaken with a wide range of stakeholders in four diverse countries to capture implementation experiences and key roles and innovations introduced by community cadres operating within a complex health programme.

A limitation is the field research by rapid appraisal during short country visits. Thus, the impressions presented must be regarded as a snapshot, raising questions for further exploration, particularly regarding the impact of the identified strategies on increasing retention and their potential for scale-up.

This study could not explore the perceptions of women living with HIV and their families regarding the role of community cadres. These would be important to address in future research as the perspectives of patients and their families could differ from healthcare workers and managers.

Introduction

In April 2012, the WHO recommended the use of lifelong triple antiretroviral treatment (ART) for all pregnant and lactating women living with HIV, regardless of CD4 cell count and/or clinical staging (PMTCT Option B+), to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and to keep mothers healthy.1

Lifelong treatment for pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV has also been advocated as a strategy to reduce transmission to HIV-negative partners.2 The WHO further states that this approach would strengthen the effectiveness of the PMTCT programme, through improved linkages with ART programmes.1 3–5

These global recommendations have prompted rapid adoption of Option B+ guidelines across high-burden countries. The WHO identified 22 priority countries encompassing 90% of the world’s population living with HIV and comprising 75% of women in need of PMTCT globally. In those predominantly low-income and middle-income African countries, the proportion of women receiving treatment more than doubled between 2009 and 2015.6 These increases have been largely attributed to the adoption of Option B+, with all priority countries having implemented this approach by 2015.7 Nonetheless, countries face challenges in reaching scale, while health systems and health workers face ever-increasing, complex demands.

Therefore, as more countries endorse lifelong treatment for all individuals living with HIV, health services should implement strategies to ensure good retention in care. Research in Malawi, the first country to implement Option B+, found lower retention in care for pregnant women living with HIV initiated on lifelong ART compared with other adults.8 Uganda, however, reported similar retention rates at 6 months for pregnant women (88%) and other non-pregnant adults (87%).9 A recent review of Option B+ roll out in Malawi10 demonstrated that while women receiving lifelong ART had a higher risk of dropout during the first 2 years following initiation than other adult cohorts, retention rates were similar as the programme matured. This emphasises the need to focus efforts in the first years of implementation, when women are most likely to be lost to follow-up.

While the literature around factors contributing to poor adherence and retention in HIV care is well known,11–13 evidence around strategies to improve retention is limited. One of the serious constraints to scaling up HIV treatment and care is the critical shortage of health workers. With 3% of the global health work force14 and a disproportionate share of people living with HIV, the sub-Saharan African region is increasingly focused on the potential for different community cadres to fill the gap.15–17 This article presents qualitative findings from a rapid appraisal with the objective to explore the roles of community cadres in improving access to and retention in care for PMTCT in the context of treatment scale-up. This paper aims to highlight the different cadres and the wide range of activities they perform.

Methods

Study design

The research was part of an evaluation of the Optimizing HIV Treatment Access (OHTA) initiative for pregnant and breastfeeding women. The initiative, funded by the governments of Sweden and Norway through the Unicef, was undertaken in four countries (Malawi, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Côte d’Ivoire) between 2013 and 2017 in partnership with several international and local implementing partners (IPs).18 The OHTA initiative aimed to support the transition to Option B+ for PMTCT in the DRC and Cote d’Ivoire and to optimise delivery and increase demand in Uganda and Malawi.19 To achieve its aims, OHTA focused among other objectives on strengthening community-facility linkages through establishing or strengthening community-based lay health worker cadres.

We defined community cadres as any lay health workers (paid or voluntary) who: provide care and support for pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV; are trained on PMTCT but have received no formal professional or paraprofessional certificate or tertiary education degree (adapted from Lewin et al, 2010.)20

This descriptive qualitative study21 used rapid appraisal methods22 to explore the roles of community cadres in improving access to and retention in care for PMTCT services. Rapid Appraisal is an approach that draws on multiple data collection methods and techniques to quickly, yet systematically, collect data when time in the field is limited and research findings are needed in a timely manner for decision-makers. Qualitative methodology was chosen as it allows for direct engagement with participants within their social context and this qualitative approach is flexible and adaptive allowing for probing key aspects and multi-level factors experienced by the range of stakeholders involved in PMTCT service delivery.23

Settings and participants

Qualitative data were collected through desk review and individual interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) during country fieldwork of 12 days per country in the DRC, Cote d’Ivoire, Malawi and Uganda between June and July 2015 (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of participants

| Type of interview | Participant category | Number of interviewees/focus group discussion participants |

|

Malawi

Data collection 15–24 June: Districts visited Lilongwe, Mzimba North, Zomba | ||

| Individual interviews (39% female; 61% male) |

Implementing partner | Two females |

| Ministry of Health | One female, two males | |

| Multilateral agency | One female, one male | |

| District management | Five males | |

| Facility-based health workers | Two females, two males | |

| Community-based health worker | One female, one male | |

| Focus Group Discussions (53% female; 47% male) |

Implementing partner | Seven female, four males |

| Ministry of Health | One female, two males | |

| Multilateral agency | Two females; three males | |

| District management | One female, three males | |

| Facility-based health workers | Seven females, five males | |

| Community-based health workers (Health Surveillance Assistants, Male Study Circles, M2M mentor mothers, Community advisory board) |

10 groups (average size nine individuals, mixed gender) | |

|

Côte d’ Ivoire

Data collection 19–31 July: Three districts visited (Port-Bouet, Bouake Sud, Daloa) | ||

| Individual interviews (32% female; 68% male) |

Implementing partner | Four females, six males |

| Ministry of Health | One female, three males | |

| Multilateral agency | Three females, three males | |

| District management | One female, six males | |

| Facility-based health workers | One male | |

| Focus Group Discussions (53% female; 47% male) |

Implementing partner | Four groups (average size 7, mixed gender) |

| District management | One group of two females and four males | |

| Facility-based health workers | One group of two females and one male | |

| Community-based health workers (scouts, lay counsellors, community health workers, traditional leaders) |

Three groups (average size 8, mixed gender) | |

|

Democratic Republic of Congo

Data collection 8–19 June 2015: three health zones in the Katanga Province (Kasenga, Kapemba, Kisanga) | ||

| Individual interviews (29% female; 71% male) |

Implementing partner | Six males |

| Ministry of Health | Two females, six males | |

| Multilateral agency | Four females, six males | |

| District management | One female, three males | |

| Facility-based health workers | Two female, one male | |

| Focus Group Discussions (52% female; 48% male) |

Implementing partner | Five groups (average size 3, mixed gender) |

| Facility-based health workers | One group with four females | |

| Community-based health workers (Relais communautaires, mentor mothers, peer educator) |

Four groups (average size 4, mixed gender) | |

|

Uganda

29 June to 19 July: Greater Kampala and nine districts across three regions (Bugiri, Kamuli, Kaliro, Isingiro, Bushenyi, Ibanda, Moroto, Kotido, Abim) | ||

| Individual interviews (49% female; 51% male) |

Implementing partner | Six females, nine males |

| Ministry of Health | Two females, four males | |

| Multilateral agency | Two males | |

| District management | 30 females, 27 males | |

| Community-based health worker | Two females | |

| Focus Group Discussions (54% female; 46% male) |

Implementing partner | One group with two females and one male |

| Facility-based health workers | Two groups (average size 4, mostly female) | |

| Community-based health workers (scouts, lay counsellors, community health workers, traditional leaders) |

13 groups (average size 5, mixed gender) | |

Sampling and recruitment

In advance of the country visits, potential organisations and individuals for key informant interviews and FGDs were identified through a desk review process and were shared with and amended in collaboration with Unicef headquarters and the Unicef country offices. In compiling the list of potential participants, we gave consideration to gaining as wide a range of opinion as possible so as to ensure a fair representation of how the implementation of PMTCT Option B+ and particularly community involvement was experienced in the four settings.

The Unicef country teams assisted with prescheduling appointments. Before engaging with participants, we explained in detail who we were, why we were visiting and why we wanted to speak with them. When necessary in Uganda and Malawi, especially with community cadres and their supervisors, we used the services of a translator to explain our research aim and the consenting process, while in the DRC and Cote d’Ivoire, all interviews were conducted in French through a translator. One of the research team members was a French national.

Research team

Eight researchers (all women) participated in the study as teams of 3–4 for each country visit. DB, TD, AG, NR, ED and SR had experience undertaking multicountry evaluations and have worked in the area of PMTCT but had no prior relationship with any of the participants.

Data collection

Semistructured interview guides were developed for each category of respondent (Ministry of Health, IPs, district management teams, facility-based health workers and community cadres). The terms of reference excluded beneficiaries.

Each semistructured interview and FGD was conducted by one or more researchers at the interviewees’ workplaces and lasted an average of 45 min, with the support of translators. Interviews were audio-recorded where permission was granted and researchers took notes. Signed informed consent from literate participants and recorded verbal consent from illiterate participants were obtained by the interviewer.

Table 1 shows the numbers of interviews undertaken in each country. The total number of interviews undertaken per country was determined by several considerations including the geographic scope of the OHTA support in each country, regional variations in health services and cultural diversity and ensuring fair representation of all categories of participants. The number of interviews was largest in Uganda as the OHTA programme supported all four regions of the country.

Data analysis

Audio-recorded interviews and FGDs were translated and transcribed into English, and field notes were summarised. We conducted a simple manifest analysis of the qualitative material21 24 and analysed the data both deductively and inductively.25 Deductively, we sought to find answers to predefined questions (eg, what role do community cadres play in delivery of PMTCT Option B+?). Inductively, we tried to understand what new insights could be gleaned from the interviews and our experiences in the field. The analysis was based on the typed interviews, field notes and desk review material (programme reports, policy documents and country plans). Country teams came together to discuss, compare and critique emerging themes and categories. Data were then grouped (via word processor) into final categories, whose results are reported in narrative form in this paper.

Results

Types of community cadres

Interviews identified different community cadres, newly created or strengthened, to support PMTCT services. Table 2 summarises the community cadres involved in the PMTCT response. These community cadres operated either solely in the community, worked from health centres or in combination. Their mandates were PMTCT-specific or ranged across general HIV support and broader health issues. Community cadres included volunteers, such as the ‘Relais communautaires’ in the DRC to the Village Health Teams (VHTs) of Uganda. Others were supported by IPs, such as the mentor mothers in Malawi, Uganda and the DRC, while some were employed directly by the Ministry of Health, such as the Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) of Malawi. Some of these cadres, including the mentor mothers in Uganda or expert client/peer supporters in all four countries, were themselves living with HIV and trained to provide counselling, psychosocial support and peer support to their peers.

Table 2.

Community cadres involved in the PMTCT response

| Health worker | Country | Paid/Volunteer | Formal Gov structure/ Informal |

Facility/ Community-based |

HIV-specific/General | Domains | ||

| Community engagement | Linkage to care | Longitudinal Follow-up | ||||||

| ASCs | Cote d’Ivoire | Not standardised | Formal | Community | General | Participate in community engagement activities with work plans developed by responsible implementing partners, attend weekly review meetings organised by midwives/nurses where registers are reviewed and patients who require follow-up through phones and home visits are identified and assigned to ASCs. | ||

| x | x | x | ||||||

| Assistants sociaux (social assistants) | DRC | Paid | Informal/NGO-based | Facility | HIV-specific | Provide psychosocial support to patients who test HIV-positive. | ||

| x | ||||||||

| Community Counsellors | Cote d’Ivoire | Paid | Informal/NGO-based | Facility | HIV-specific | Serve as the link between the ASCs and facility health workers in addition to providing psychosocial support to women who have tested positive; Manage the referral and counter referral process by consolidating information and monitoring clients’ appointment dashboard. | ||

| x | x | x | ||||||

| Expert Clients/Peer educators (living with HIV) | All 4 | Volunteer | Informal/NGO-based | Combination | HIV-specific |

Responsibilities at facility: client health education sessions; adherence assessment counselling and support; nutritional assessment; maintaining a client appointment system to help facilitate clinic visits and identify missed appointments; developing a search list for clients who miss appointments; following up patients through telephone calls and physical tracking of clients and HIV post-test and pre-ART counselling. At the community level: follow-up clients who miss appointments, continue to provide adherence counselling and support, and conduct home visits for sick patients or those struggling with treatment adherence. |

||

| x | ||||||||

| Health Surveillance Assistants | Malawi | Paid | Formal | Work out of Village clinics in community but report to facility | General | Health education talks, provision of immunisation services, iCCM, home and market inspection, malaria screening, growth monitoring and nutrition education. HIV-related tasks include: HIV prevention, provision of HCT, opportunistic infection management and cotrimoxazole administration, defaulter tracing and general support to ART clients. |

||

| x | x | x | ||||||

| Linkage Facilitator | Uganda | Paid | Informal/NGO-based | Facility | General | Receive all the referrals from the community, help navigate clients to the services they require, consolidate all the referral information and ensure information is fed back to the community. | ||

| x | x | |||||||

| Male Champions | Malawi, Uganda | Volunteer | Informal/NGO-based | Community | General | Conduct door to door peer education and provide health education talks to mobilise men to accompany their partners to access MNCH services: promote increased couple HIV counselling and testing, and in the case of discordant relationships, facilitate partner disclosure and general partner support. | ||

| x | x | |||||||

| Mentor mothers (living with HIV) | DRC, Malawi, Uganda | Paid | Informal/NGO-based | Combination | HIV-specific |

Community level: conduct community health education talks on MNCH and PMTCT topics, conduct household visits of pregnant and lactating women identified and referred by VHTS, conduct referrals and obtain the list of clients missing appointments and HIV-positive mother baby pairs for follow-up. Facility level: group education talks, client triage, HIV pretest education at the ANC clinics, TB and nutrition screening services, individual and couple counselling sessions, active client follow-up through phone calls and home visits (where community mentor mothers do not exist) and provide reminders to patients for their next visits. Mentor mothers also organise psychosocial support groups with the support of health workers and expert clients and participate in integrated outreach activities. |

||

| x | x | x | ||||||

| Relais communautaires | DRC | Volunteer | Formal | Community | General | Promote the use of reproductive health services including ANC attendance and family planning, conduct home visits, and carry out community sensitisation activities. | ||

| x | x | |||||||

| Village Health Committees | Malawi | Volunteer | Formal | Community | General | Conduct village health inspections and mobilise households to participate in immunisation campaigns, child health days and other outreach activities. | ||

| x | x | |||||||

| VHTs | Uganda | Volunteer | Formal | Community | General | Provide a range of health promotion, referral and linkage services. Some HIV-related responsibilities include sensitising communities on HIV prevention, care and treatment, demand generation for MNCH/PMTCT services and referral for HIV counselling and testing (HCT). | ||

| x | x | |||||||

ART, antiretroviral treatment; ASCs, Agents de Sante Communautaire; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo; HCT, HIV counselling and testing; iCCM; integrated community case management of childhood illnesses; MNCH; maternal and child health; NGO, non-governmental organisation; PMTCT, prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV; VHT, village health team.

Activities performed by community cadres

Acting as the interface between communities and health services, community cadres created awareness, generated demand for PMTCT services (raising awareness about service availability and importance of seeking care), referred and followed up pregnant and lactating women living with HIV in the community, to ensure they received appropriate services and remained in care.

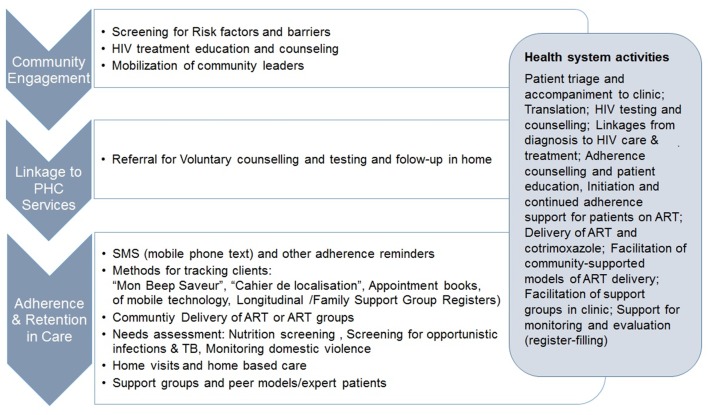

Figure 1 illustrates the roles of community cadres across the PMTCT care continuum.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of community- and facility-based activities for increased service uptake and improved retention in PMTCT care. The roles of community cadres across the PMTCT care continuum, which includes community engagement activities to sensitise the community around the need to test for HIV and access care; linkage to care in which community cadres inform the community around where to access services and refer to care and adherence a strategies to ensure those living with HIV are retained in care. The figure further illustrates the role of community cadres who operate partly out of the health facilities. ANC, Antenatal Care; ART, antiretroviral treatment; EID, Early Infant Diagnosis; HTC, HIV counseling and Testing; PHC, Primary Health Care; PMTCT, prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Community engagement and awareness raising

‘I am not paid anything. I joined this because I felt that the life of other people was very important to me. When I moved to the villages, my first role was to mobilize (provide information and encouragement) women. When I identified any pregnant women, I mobilized them to come to the hospital so that they test. When I send them, I follow them (make a follow-up home visit) to make sure that they have reached the unit.’ (Expert client, Uganda)

Cadres including the Agents de Santé Communautaires (ASCs) of Cote d’Ivoire, Relais communautaires of DRC, and the Expert clients and VHTs and committees of Uganda and Malawi, participated in community dialogues to increase service uptake and retention.

‘They (community cadres) have contributed a lot to the health centre…because we as health workers don’t have time to go into the community to sensitize them (inform them of HIV treatment and prevention available).’ (Facility-based health worker, Cote d’Ivoire)

Health workers reported that participating in an open dialogue with community members and getting the buy-in of leaders helped dispel myths and fears around HIV and addressed challenges with stigma.

‘Thanks to the support of the ASCs, they have been able to meet community leaders and women’s associations, and explained to them transmission of HIV and … what women who are positive and pregnant can do.’ (Nurse, Cote d’Ivoire)

Furthermore, the male champions of Uganda and Malawi actively engaged men to promote increased partner participation in reproductive health and addressed interpersonal barriers to retention including partner disclosure and domestic violence.

‘Male motivators and male study circles conduct door-to-door peer education to encourage fellow men to accompany their wives to ANC, couple HTC, delivery and post-natal checks. But during meetings organised by chiefs, they also take advantage to provide education on a topic.’ (IP, Malawi)

Client follow-up and retention in care

‘Many people still don’t believe in the HIV/AIDS. They still don’t think they need to live, so you find many families are breaking because of HIV/AIDS and so these high levels of stigma is still causing treatment interruptions (because women drop out of care).’ (MOH, Uganda)

Once clients are initiated into care, community cadres focused on counselling and psychosocial support, including formation of support groups and key activities to promote positive living and self-efficacy in HIV management. Community cadres who undertook home visits and followed up patients were perceived to play an integral role in this domain.

‘So we have what we call active-plan follow-up. Every Friday there is a meeting at the facility. That meeting involves the facility mentor mothers and the health facility team, the midwife in charge and community mentor mothers. They map out and say, who are the women who are defaulted, and which parishes do they come from. So they come up with lists and distribute this (to the mentor mothers).’ (IP, Uganda)

Concerns were highlighted about confidentiality and the use of the volunteer cadres for follow-up of individuals living with HIV.

‘There is also a challenge to work with VHTs (Village health teams) with regards to HIV-positive mothers. They don’t want VHTs to know their status, especially with retention. Mothers get very angry when VHTs go to do home visits (likely due to fear of HIV stigma).’ (Facility interview, Uganda)

Communities were often more accepting of these generalist community cadres for broad health promotion activities (such as ANC care, follow-up of mothers postpartum, and their children), while HIV-specific follow-up was preferred from peer supporters and lay counsellors. As many of these HIV-specific community cadres were living with HIV, they could share personal coping strategies and demonstrate the positive impact of treatment adherence through their own experiences.

‘There is very good retention for Option B+ and also good coverage for HIV testing and that in a way is attributed to the Mentor Mothers. Because these are the people who (have) gone through the experience of PMTCT or Option B +… and are able to share with other women, to help them provide some of the counselling, so that they can get the intended care.’ (Malawi, IP)

Peer support was a commonly used role for community cadres in all four countries. Through support networks (treatment buddies, peer supports, mentor mothers, expert clients, support groups), mothers had access to emotional support and motivation and were provided with a platform to share knowledge and experiences.

‘So even the peer clients, the peer mothers work with the VHT members, so they can follow-up their colleagues and bring them back. Then healthcare workers… can do physical follow-up but they also have a bit of issues around, you know, going through the community. And the community knows that, oh, they recognise that house, and there is something wrong with that woman there, you know, that kind of thing, yeah. But mostly the peer, that is where the peer mothers become very successful in following up (to address problems with retention).’ (IP, Uganda)

Such strategies to improve patient retention recognised the time and cost burdens for patients travelling monthly to facilities for ART refills. In Malawi, HSAs were trained to provide ART refills at rural health posts. In this model, clients obtained refills every 3 months, only visiting the clinic for screening every 6 months. Similarly, community ART distribution points in the DRC were run by People Living with HIV. One IP in the DRC piloted the use of an adherence group for HIV-positive women, with one patient responsible each month for picking up ART refills.

‘We are piloting the GAAC model (groups to support community accession), which is an adherence group in the community. One person in the group goes every month to pick up drugs for the group. This is working well in certain areas. The group needs to know each other well for it to work.’ (IP, DRC)

Health facility-based activities

Some community cadres, including linkage facilitators in Uganda and community counsellors in Cote d’Ivoire, were based in facilities full-time or divided their time between community and facility, to support staff with patient triage, educational talks, pretest counselling and referrals to facility staff for HIV-testing. In Malawi, the HSAs performed HIV-testing and counselling after 28 days of formal training and in Uganda lay counsellors conduct HIV testing.

One advantage of this system was that, by performing regular educational, counselling and administrative duties, these paid community cadres focused on guiding patients through the continuum of care and eased the non-clinical workload of midwifes and nurses:

‘They have lay counsellors at health centres permanently, who fill registers and records of pregnant women, and make appointments for treatment, and follow-up women who miss her appointment… The ASCs also have a referral form. In addition to this, the NGO has designed some materials like diaries to monitor the appointments of pregnant women. And when they are completed at field level, they summarize this at the health facility, and then at the health facility they can know how many have been referred.’ (Health worker, Cote d’Ivoire)

Uganda established Family Support Groups to encourage family participation in follow-up ART visits, to improve patient retention. These support groups were often facilitated by nurses, in conjunction with community cadres and mentor mothers. Encouraging women to bring their children ensured exposed children were also monitored, until their 18 months status was ascertained. Furthermore, these groups encouraged women to disclose their status to partners and included them as active participants in family health decisions. Group sessions included a health education talk, scheduled on the same day as ART drug pick-up, to encourage adherence. Support groups on the same day as monthly ART pick-up dates were also occurring in the DRC, Cote d’Ivoire and Malawi.

‘So they support retention in that way, they support the health workers to coordinate family support groups, […] that have been institutionalised by Minister of Health. So in these family support groups, these HIV-positive mums come with their babies. We always insist that facilitators come with the baby and… in m2m we also do what we call a needs assessment, to ensure that, in addition to just getting the education and the testimonies and trying to make each other strong, we ensure that that’s an opportunity to catch up with services that are due, like Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).’ (IP, Uganda)

Patient tracking

In all countries, community cadres supported health workers with tracing women and children who missed appointments. Tools used for longitudinal follow-up varied across settings, generally including client appointment books, agendas to identify those missing appointments and longitudinal facility registers. A combination of phone calls and home visits were used to track patients and reconnect them to services.

‘So when she’s compiling her report, she has a paper-based report that shows loss of month one, loss of month two… and then missed appointments for that month. So as she sending the report to the central level, she’s also thinking of what actions. I was expecting thirty mothers and got fifteen. So, she has to put down actions for the fifteen lost mothers. And then either use of community people or whatever, she has to make sure that she tracks them.’ (National MOH, Uganda)

Limited access to accurate patient information caused a major barrier to finding patients lost to follow-up. In ‘Mon Bip Mon Sauveur’ (My Beep My Saviour) a Cote d’Ivoire initiative, facility staff or ASCs gave women a missed call immediately after they provided phone numbers, to ensure the number was correct. Since a large proportion of the population did not have access to mobile phones or formal addresses, another strategy (‘Cahier de Localisation’ or Location Book) described the area in which patients lived according to landmarks and mapped them to allow easier tracking.

Challenges to the sustainability of community cadres

Concerns were expressed around community cadre remuneration that is mainly dependent on external support and variability in payment schedules.

‘She is saying that these peers, they are widows, and they spend a lot of time here when there is no-one to do any other activities in their homes. And then, on top of that, they have their children who are at school. So they are worried where to get funds for their children. So they are saying, even their funds don’t come in time, because she is saying like after 3 months, so they find that they are really broke.’ (Health worker, Uganda)

Despite some financial support for community cadres undertaking HIV-related activities, these incentives did not amount to a living wage, and retention of these cadres was described as a challenge.

‘For the village health teams, I will say allowance. When we work with them often, we give them some refreshment and some transport. Otherwise, paying them a stipend, like which is regular, no.’ (IP, Uganda)

‘I am not married, so even though the money is little, it still helps me because I have children and it helps me to help them […]. I don’t worry about anything, because I consider myself to have a job.’ (Expert Client, Malawi).

The mothers2mothers model in Uganda and Malawi, mentor mothers in the DRC and the HSAs in Malawi were among the only cadres receiving a regular salary:

‘Mothers to Mothers model, […], is not voluntarily at all, in all in the countries. So we don’t believe in voluntarism. We have a component, one of objectives is empowering women who are living with HIV, and we realise that when you get the stipend and give it to them at the end of the month, it makes more meaning to them. They can be able to invest it, they can be able to do things with it.’ (IP, Uganda)

‘I think that professionalisation of these mums makes them feel maybe valued, and so it really makes a difference.’ (IP, Uganda)

Discussion

This paper highlights the range and characteristics of community cadres engaged to support PMTCT programmes across the four countries. The findings of the paper provide important insights into the unique roles of community cadres and innovative strategies employed by them to support PMTCT. These include family support groups, community adherence groups and active follow-up which can have significant influence on the uptake and retention in HIV care in these low-resourced contexts.

The scale-up of lifelong treatment and investments in newly created cadres or capacity-building of existing cadres have facilitated their engagement in promoting and supporting lifelong HIV treatment at community and facility level. While this paper, reflects a synthesis of a mid-term programmatic evaluation and therefore does not make linkages between activity data and PMTCT-related health outcomes, the synthesis of qualitative investigations from key informant interviews demonstrates the interplay of these community cadres with facility-based interventions in supporting PMTCT scale-up. Investments in increasing community awareness around the benefits of HIV testing and treatment adherence, while addressing stigma and discrimination in the community through positive messaging and the use of peer supporters who openly disclose their status, have been shown in other studies to improve patient retention.26

Once clients are linked to services, the HIV-specific community cadres, largely facility-based, support uptake of and retention in HIV services, through counselling, HIV-testing, home-based care, patient education, adherence counselling, patient SMS reminders and defaulter tracing. Integrating peers into the healthcare team has resulted in positive patient outcomes, where peers motivate behavioural change in people living with HIV, to improve patient retention.26 Furthermore, investments in facility-based lay cadres have eased the clinical workload of health workers, resembling task-shifting in other programmes.27 Operationalising community cadres for the HIV response has to take into consideration interactions between established generalist community cadres covering a range of healthcare activities and cadres created specifically for the HIV response.

The mothers2mothers programme is a successful example of peer-support in PMTCT services across several countries. It hires, remunerates, supervises and supports with external funding women living with HIV to serve as peers in PMTCT programmes. A recent evaluation in Uganda found improved outcomes across a range of health-related indicators, including significantly higher rates of 12-month ART retention (91% vs 64%), uptake of EID at 6–8 weeks (72 vs 46%), ART initiation in infants (61% vs 28%) and partner disclosure (82% vs 70%) in M2M supported sites.28

Ongoing challenges with stigma, geographical access to health services, high levels of poverty and low male partner involvement in maternal and reproductive services make women less likely to remain on treatment. Furthermore, high HIV-prevalence rates, coupled with high fertility rates in these countries, place an increasing burden on health systems for follow-up and support of a growing number of women on ART. It is therefore critical that PMTCT programmes make concerted efforts towards scaling up effective strategies to optimise retention.

With the rapidly increasing HIV care and treatment needs and the accelerating human resource crisis in many African countries, community-based cadres will remain a core feature of health systems. Effective inclusion of these cadres in the health team requires political and financial commitments, regulatory frameworks and mechanisms for supervision and mentoring.17 29 30

In the absence of formal recognition, these cadres will continue to be inadequately resourced and undervalued, undercutting their potential health impacts.31 Community cadres interviewed highlighted a range of challenges for patient follow-up including lack of transport, phones or airtime and insufficient money for transport. Furthermore, remuneration of community cadres is currently not standardised within countries and has the potential to create tensions between cadres and to reduce motivation. These cadres are largely donor-supported and high turnover rates, inadequate job security, formal recognition or harmonisation, threaten the sustainability of achievements. These well-established challenges affecting Community Cadre programmes have been reported for several decades.32 The recent interest in and use of community cadres in response to large-scale ART roll-out appear to pay insufficient attention to these major determinants of success.29

Conclusion

Community cadres can provide an integral link between communities and health facilities, using innovative strategies to support overstretched health workers in HIV client support and follow-up. However, challenges remain including the need to invest in country-specific standardisation of roles, responsibilities and remuneration for the range of community cadres in order to promote sustainability and maximise the potential effectiveness of their activities. Further research is needed to understand which services, strategies and approaches are most effective in improving outcomes along the continuum of care, including the perspectives of women living with HIV and their families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Ministry of Health, UNICEF country office and implementing partners in Cote d’Ivoire, DRC Malawi and Uganda for their assistance with the field visits. We thank all participants for sharing their insights and experiences with us.

Footnotes

Contributors: TD, DB, SR, AG and ED conceptualised the study and developed the protocol and data collection materials. TD, AG, DB, NR, SR and ED participated in the country visits in 2015 and participated in the analysis of interview transcripts. DB and TD prepared the first draft of the paper. All authors reviewed and contributed to subsequent drafts and approved the final version for publication.

Funding: The research was supported by UNICEF New York through a grant from the government of Sweden and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) and the South African Medical Research Council. The South African Medical Research Council supported the time of the authors to write the article. TD is supported by the National Research Foundation, South Africa. Grant number: UNICEF RFPS-USA-2014-501939-SAMRC

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: This study received ethical approval from the South African Medical Research Council (EC014-4/2015) and received permission from each of the following authorities: Malawi: Director of the HIV & AIDS Department in the national Ministry of Health; Uganda: Higher degrees, research and ethics committee, College of Health Sciences, School of Public Health, Makerere University; Cote d’Ivoire: President of the National Committee of Research and Ethics, Ministry of Health; DRC: Director, National AIDS Control Programme (PNLS), Ministry of Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The audio recordings and transcribed interviews are stored in a password protected system with the project team at the South African Medical Research Council office. The privacy of the data is maintained since participants did not consent for data to be shared beyond the research team. However, all data have been consolidated and written up for the purposes of the evaluation and reports published on the SAMRC website in addition to the development of peer reviewed publications.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Programmatic update: use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. Geneva, 2012. (accessed 15 Nov 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rayment M. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2012;38:193–93. 10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNICEF Business Leadership Council. A business case for options B and B+ to eliminate mother to child transmission of HIV by 2015. New York: UNICEF, 2012. (Accessed 5 January 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Presidential Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Scientific Advisory Board. Recommendations for the office of the US Global AIDS coordinator: implications of HPTN 052 for PEPFAR’s Treatment Programs 2011. Washington, 2011. (accessed 10 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bachman G, Pmtct PB. Community: Updates and PEPFAR Perspectives Presentations from the CCABA/UNICEF/UNAIDS/Global Fund/RIATT ‘Road to Washington’ meeting in London. London: UNICEF, 2012. http://www.ccaba.org/wp-content/uploads/Bachman-and-Phelps-presentation.pdf (accessed 15 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haroz D, von Zinkernagel D, Kiragu K. Development and impact of the global plan. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75(Suppl 1):S2–S6. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UNAIDS. On the fast-track to an AIDS-free generation. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2016. (accessed 10 Jan 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tenthani L, Haas AD, Tweya H, et al. Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women (’Option B+') in Malawi. AIDS 2014;28:589–98. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kieffer MP, Mattingly M, Giphart A, et al. Lessons learned from early implementation of option B+: the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation experience in 11 African countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;67 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S188–94. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haas AD, Tenthani L, Msukwa MT, et al. Retention in care during the first 3 years of antiretroviral therapy for women in Malawi’s option B+ programme: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 2016;3:e175–e182. 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)00008-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2009;4:e5790 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geng EH, Nash D, Kambugu A, et al. Retention in care among HIV-infected patients in resource-limited settings: emerging insights and new directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2010;7:234–44. 10.1007/s11904-010-0061-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hodgson I, Plummer ML, Konopka SN, et al. A systematic review of individual and contextual factors affecting ART initiation, adherence, and retention for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS One 2014;9:e111421 10.1371/journal.pone.0111421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maddison AR, Schlech WF. Will universal access to antiretroviral therapy ever be possible? The health care worker challenge. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2010;21:e64–e69. 10.1155/2010/432306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jerome G, Ivers LC. Community health workers in health systems strengthening: a qualitative evaluation from rural Haiti. AIDS 2010;24(Suppl 1):S67–S72. 10.1097/01.aids.0000366084.75945.c9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task- shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Hum Resour Health 2010;8:8:8 10.1186/1478-4491-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rasschaert F, Philips M, Van Leemput L, et al. Tackling health workforce shortages during antiretroviral treatment scale-up--experiences from Ethiopia and Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;57(Suppl 2):S109–S112. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821f9b69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doherty T, Besada D, Rohde S, et al. Report on the external mid-term, formative evaluation of the optimizing HIV treatment access (OHTA) for pregnant and breastfeeding women initiative in Uganda, Malawi, Ivory Coast and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Cape Town, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. UNICEF. Optimizing HIV treatment access for pregnant and breastfeeding women. New York: UNICEF, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;3:CD004015 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London: Sage Publications, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22. USAID Center for Development Information and Evaluation. Using rapid appraisal methods. perfomance monitoring and evaluation TIPS. Washington: USAID, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sprague C, Scanlon ML, Pantalone DW. Qualitative research methods to advance research on health inequities among previously incarcerated women living with HIV in Alabama. Health Educ Behav 2017;44:716–27. 10.1177/1090198117726573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24:105–12. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2006;5:80–92. 10.1177/160940690600500107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. MSF. Reaching 90 90 90. Brussels: MSF, 2016. (accessed 15 Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27. MSF. HIV/TB counseling: who is doing the job? Time for recognition of lay counselors. Brussels: MSF, 2016. (accessed 15 Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zikusooka CM, Kibuuka-Musoke D, Bwanika JB, et al. External evaluation of the m2m mentor mother model as implemented under the STAR-EC Program in Uganda. Cape Town: Mothers to Mothers, 2014. (accessed 15 Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hermann K, Van Damme W, Pariyo GW, et al. Community health workers for ART in sub-Saharan Africa: learning from experience--capitalizing on new opportunities. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:31 10.1186/1478-4491-7-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lehmann U, Van Damme W, Barten F, et al. Task shifting: the answer to the human resources crisis in Africa? Hum Resour Health 2009;7:49 10.1186/1478-4491-7-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mwai GW, Mburu G, Torpey K, et al. Role and outcomes of community health workers in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18586 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lehmann U, Sanders D. Community health workers: what do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2007. (accessed 9 Jan 2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.