Abstract

Objective

To compare cancer-related systematic reviews (SRs) published in the Cochrane Database of SRs (CDSR) and high-impact journals, with respect to type, content, quality and citation rates.

Design

Methodological SR with assessment and comparison of SRs and meta-analyses. Two authors independently assessed methodological quality using an Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR)-based extraction form. Both authors independently screened search results, extracted content-relevant characteristics and retrieved citation numbers of the included reviews using the Clarivate Analytics Web of Science database.

Data sources

Cancer-related SRs were retrieved from the CDSR, as well as from the 10 journals which publish oncological SRs and had the highest impact factors, using a comprehensive search in both the CDSR and MEDLINE.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

We included all cancer-related SRs and meta-analyses published from January 2011 to May 2016. Methodological SRs were excluded.

Results

We included 346 applicable Cochrane reviews and 215 SRs from high-impact journals. Cochrane reviews consistently met more individual AMSTAR criteria, notably with regard to an a priori design (risk ratio (RR) 3.89; 95% CI 3.10 to 4.88), inclusion of the grey literature and trial registries (RR 3.52; 95% CI 2.84 to 4.37) in their searches, and the reporting of excluded studies (RR 8.80; 95% CI 6.06 to 12.78). Cochrane reviews were less likely to address questions of prognosis (RR 0.04; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.09), use individual patient data (RR 0.03; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.09) or be based on non-randomised controlled trials (RR 0.04; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.09). Citation rates of Cochrane reviews were notably lower than those for high-impact journals (Cochrane reviews: mean number of citations 6.52 (range 0–143); high-impact journal SRs: 74.45 (0–652)).

Conclusions

When comparing cancer-related SRs published in the CDSR versus those published in high-impact medical journals, Cochrane reviews were consistently of higher methodological quality, but cited less frequently.

Keywords: methodological systematic review, amstar, quality assessment

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Unique cross-disciplinary comparison of systematic reviews (SRs) in oncology including over 550 SRs.

Methodological assessment using Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews, a validated and widely used tool to evaluate the quality of SRs.

It was not feasible to blind the authors of this study to the source journal of a given review, which may have potentially biased the assessments.

Introduction

The care of patients with cancer continues to be a clinical research priority as documented by an increasing number of publications of different types including systematic reviews (SRs). In fact, in recent years, oncology has been the medical discipline with the highest number of publications and the numbers continue to rise.1 The large number of oncology-related research studies poses a tremendous challenge for patients, healthcare providers and health policy-makers alike when seeking to stay abreast of a particular oncological topic. SRs follow reproducible methods to identify relevant studies for a given question, apply predefined and explicit eligibility criteria, perform assessments of the validity of findings and systematically present the results. In this context, SRs can be helpful in summarising the current best evidence for a particular clinical question to support both individual decision-making and in serving as the basis for clinical practice guidelines.2 3 Cochrane is widely known for having developed many of the methodological standards based on which SRs should be conducted. These standards are specified in the 2016 updated Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR). However, a large number of oncology-related SRs are currently published by clinical journals, high-impact medical journals, oncology focused journals, as well as subspecialty journals. As the number of SRs has steadily increased over the past two decades, their methodological rigour has been drawn into scrutiny.4–6 To date, no study has formally assessed the methodological quality of oncology-related SRs which assume such a prominent place in the medical literature.

In this study, we therefore sought to formally assess the methodological quality, type, content and citation rates of oncology-related SRs, comparing SRs published in high-impact medical journals with those published in the Cochrane Database of SRs (CDSR).

Methods

The design and eligibility criteria of this project were based on an a priori written protocol. Study reporting is provided in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. However, as a methodology-focused review, it was not eligible for a registration in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO).

Patient involvement

Given its methodological focus, we did not evaluate patient-related outcomes. Therefore, we also chose not to involve patients’ input in its design. However, the clear intent of this study is to indirectly benefit the welfare of patients by promoting the development and dissemination of high-quality SRs.

Eligibility criteria

We selected all Cochrane reviews that examined questions related to oncology. We furthermore identified all cancer-related SRs published in the highest impact medical journals, as defined by the InCites Journal Citation Report 2014, from the same time period via an electronic database search. To reflect contemporary reviews, we chose the 5-year period between January 2011 and May 2016 as the study timeframe. We did not apply restrictions with regard to study design or meta-analytic methods, and also included SRs without a meta-analysis. We broadly included studies related to all types of cancer.

The 10 journals with the highest impact factors that published SRs on cancer topics were as follows: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, JAMA, Lancet Oncology, Journal of Clinical Oncology, The BMJ, Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, Journal of the National Cancer Institute and Cancer Research. We did not apply any language restrictions; however, all selected journals published exclusively in English. We excluded SRs with a methodological focus. For our examination, we used the original English version of each Cochrane review (given that foreign language translation exists for many Cochrane reviews). In cases where one or more updates of previously published Cochrane reviews existed, we based our assessment on the most recently published version within the defined timeframe.

Study identification and selection

We identified all cancer-related Cochrane reviews in the CDSR from January 2011 to May 2016 using the built-in ‘Browse by topic’ database function with the options ‘Cancer’ and ‘Stage: Review’. In a parallel step, we conducted a comprehensive literature search of SRs published in the 10 highest impact journals from the same time period on 1 June 2016. An information specialist developed the search strategy for MEDLINE using the following search terms: cancer, leukaemia, tumor, tumour, leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, solid, neoplasm, meta-analysis, systematic review, publication dates: 2011 to 2016. We used the following Medical Subject Headings terms: Neoplasm by Histologic Type and Neoplasms by Site. The full search strategy is provided in the online supplementary appendix. Two authors independently (MG, VMN) and in duplicate performed title and abstract screening, full text screening, and ultimately, selection of reviews to be included. We resolved discrepancies by discussion with one of two other authors (NS, PD).

bmjopen-2017-020869supp001.pdf (454.4KB, pdf)

Quality assessment

We evaluated methodological quality with the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist, by Shea et al.7 The checklist consists of 11 items and was specially developed to assess the methodological quality of SRs and meta-analyses. In cases where AMSTAR combined several items into one criterion, we separated these out into 20 individual items for the sake of transparency but readjusted them into single items for the AMSTAR scoring. A complete list of items can be found in the appendix; answer options were ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘not applicable’. Methods like sensitivity and subgroup analyses, or funnel plots for the assessment of publication bias require a minimum quantity of studies. For example, meaningful interpretations of funnel plots require a threshold of at least 10 studies.8 In SRs where there was evidence that these secondary analyses were planned, but could not be meaningfully conducted, this criterion was rated as fulfilled. Two authors (MG, VMN) performed the quality assessments independently and in duplicate. We resolved disagreements by discussion and with a third author (NS, PD).

Data extraction and extracted items

The included studies were then reviewed in detail as part of a clinical content analysis. We extracted the review type, the study design of the included studies and review question (eg, therapeutic, diagnostic or prognostic) of included studies. We chose the following items to reflect the review content: cancer type (eg, breast, lung, colorectal, but also ‘cancer in general’, ‘mixed’ (but not in general) and ‘other’ (eg, liver metastases or male breast cancer), intervention (eg, chemotherapy, ‘new drug’ (targeted therapies, such as monoclonal antibodies and small molecules)), radiotherapy, surgery, supportive (eg, interventions for cancer-related pain, rehabilitation after cancer treatment, interventions for depression in patients with cancer or adjuvant bisphosphonate treatment for patients with cancer), or not applicable (if prognostic, diagnostic or epidemiological review question), population (adults, children or both), the number of included studies and the number of included patients. A complete list of the 17 criteria can be found in the appendix. To ensure the completeness of our assessment, we obtained and formally considered any additional information from all (online) supplements and appendices. Two authors (MG, VMN) independently extracted these data using a previously piloted form. The data extraction form was designed a priori with consensus of four authors (MG, VMN, NS, PD). Discrepancies were once again resolved through discussion and third author arbitration if necessary (NS, PD).

Citations

We gathered the citation counts for both Cochrane reviews and high-impact journal reviews using the Clarivate Analytics Web of Science database. Citation counts were assessed on 15 February 2017 by two authors independently (AW, MG). For updates of Cochrane reviews, we considered the citations of the respective update(s) and added citations from the original review, as long as the original review and any updates were published within the predefined timeframe of our study.

Data synthesis and analysis

For dichotomous variables, we determined rates, and for continuous variables, we calculated median and IQR, or mean and range. To compare the quality of both groups, we used risk ratios and the corresponding 95% CIs. We defined an event as fulfilling a given quality indicator and have presented these data in forest plots. All statistical analyses were undertaken using Review Manager V.5.3.

Results

Search results

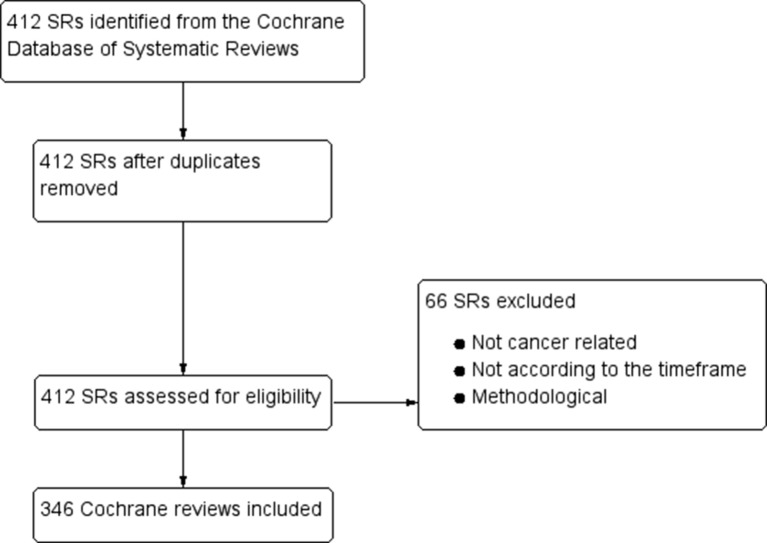

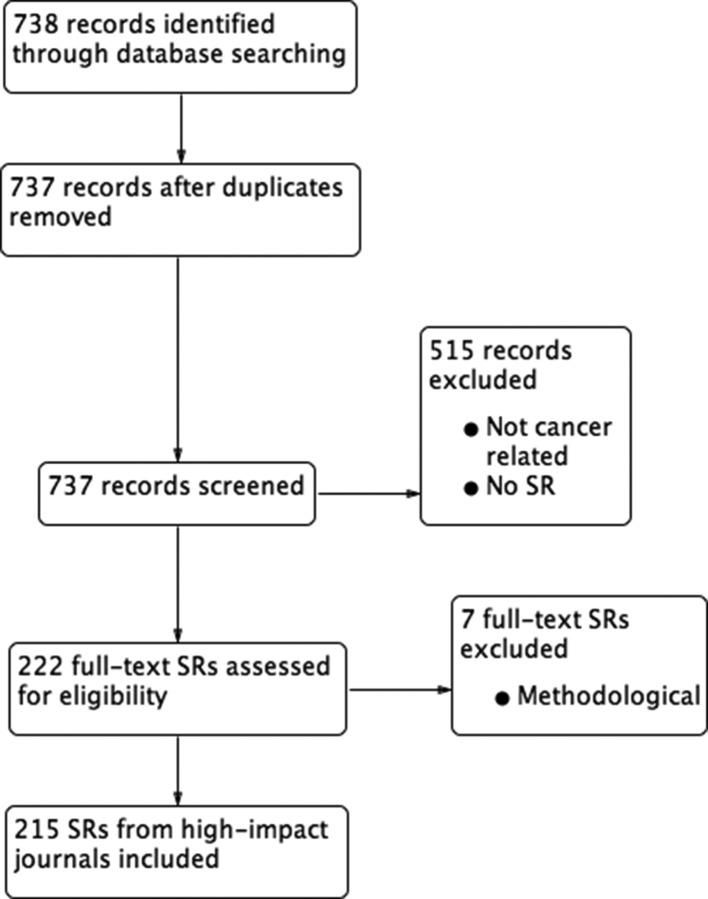

As shown in the study flow chart (figure 1), our search for oncology-related Cochrane reviews identified 412 records, of which 346 were determined to be cancer related and appropriate according to our selection criteria. Our electronic database search for high-impact SRs identified 738 records, of which 215 were ultimately included, excluding seven reviews at the full-text stage which focused on methodological issues (figure 2).9–15 The references of the included articles are provided in the online appendix.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram of Cochrane reviews. SR, systematic review.

Figure 2.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram of high-impact journal SRs. SR, systematic review.

Quality

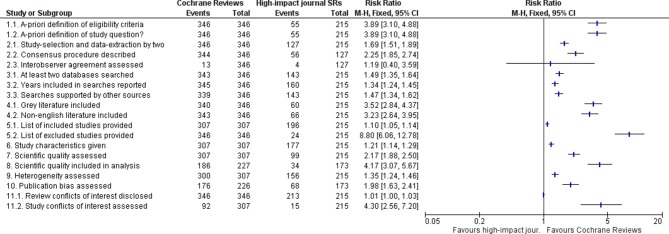

In general, reviews published by Cochrane met each quality criterion to a greater extent than reviews published in high-impact journals (figure 3). Cochrane reviews were more likely to report an a priori design, including the definition of the review question and a planned inclusion and exclusion criteria before conducting the review (both with a risk ratio (RR) of 3.89; 95% CI 3.10 to 4.88) (AMSTAR Item 1). Differences also existed in the inclusion of unpublished and non-English literature; Cochrane reviews were more likely to include unpublished (RR 3.52 (95% CI 2.84 to 4.37)) and non-English studies (RR 3.23 (95% CI 2.64 to 3.95)) (Item 4). Included studies were listed relatively equally between the two (RR 1.10; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.14) comparators, whereas a list of excluded studies, at least those rejected in the course of full-text screening, was provided almost nine times more often by Cochrane reviews (RR 8.80; 95% CI 6.06 to 12.78) (Item 5). Further, a quality assessment of the included studies (using tools such as Cochrane’s Risk of Bias, the Jadad scale or the Newcastle-Ottawa scale) was undertaken over twice as frequently in Cochrane reviews (RR 2.17; 95% CI 1.88 to 2.50) (Item 7). A meta-analysis was conducted in 67% (227/346) of Cochrane reviews and in 80% (173/215) of high-impact journal SRs. A sensitivity analysis based on study quality or risk of bias was more commonly reported in Cochrane reviews (RR 4.17; 95% CI 3.07 to 5.67). Almost 23% (53/227) of Cochrane reviews planned to undertake but did not perform sensitivity analyses due to an insufficient number of included studies, the inclusion of high risk of bias studies only or unclear information regarding study quality. Formal assessments of potential publication bias like funnel plots were undertaken or planned about twice as frequently among reviews produced by Cochrane (RR 1.98; 95% CI 1.63 to 2.41) than in SRs published in high-impact journals. However, 47.3% (107/226) of Cochrane reviews and 1.7% (3/173) of reviews from high-impact journals planned but could not perform such assessments due to an insufficient number of included studies (AMSTAR Item 10). The vast majority of SRs both in Cochrane reviews and high-impact journals disclosed potential conflicts of interest of the SR authors (RR 1.01; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.03). However, potential conflicts of interest of the trials included in the SRs were reported more frequently by Cochrane reviews than by SRs in high-impact journals, with Cochrane reviews being more than four times as likely to provide this information (RR 4.30; 95% CI 2.56 to 7.20) (Item 11).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing to what extent Cochrane reviews and SRs published in high-impact journals meet criteria for methodological quality. SR, systematic review

Characteristics of included SRs

With regard to geographical origin, the largest proportion of Cochrane reviews originated from Europe (67.3%; 233/346) and relatively infrequently originated from North America (7.5%; 26/346); meanwhile, high-impact journal SRs were as likely to come from Europe (44.2%; 95/215) or North America (40.9%; 88/215; table 1). Cochrane reviews were much less likely to use individual patient data (IPD) (RR 0.03; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.09) compared with aggregate study-level data. The majority of Cochrane reviews used the latter (95.7%; 331/346), with only three (0.9%; 3/346) including IPD exclusively, and 12 (3.5%; 12/346) using both types of data. SRs from high-impact journals were also primarily based on study-level data (68.4%; 147/215), but a much larger proportion used IPD (31.2%; 67/216). Network meta-analyses were uncommon among both Cochrane reviews (0.6%; 2/346) and high-impact SRs (2.8%; 6/215).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included Cochrane reviews and high-impact journal SRs

| Cochrane | High-impact journals | |||||||||

| Cochrane reviews (n=346) | Total high-impact journal SRs (n=215) | J Natl Cancer Inst (n=56) |

J Clin Oncol

(n=56) |

Lancet Oncology

(n=53) |

The BMJ

(n=22) |

Lancet

(n=14) |

JAMA

(n=12) |

CA Cancer J Clin

(n=1) |

Cancer Research

(n=1) |

|

| Year first published (number of SR (%)) | ||||||||||

| 2011 | 45 (13.1) | 45 (20.9) | 9 (16.1) | 14 (25) | 13 (24.5) | 2 (9.1) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (25) | ||

| 2012 | 60 (17.3) | 50 (23.2) | 20 (35.7) | 11 (19.6) | 11 (20.8) | 4 (18.2) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (25) | ||

| 2013 | 80 (23.1) | 31 (14.4) | 7 (12.5) | 8 (14.3) | 8 (15.1) | 5 (22.7) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| 2014 | 59 (17.1) | 51 (23.7) | 11 (19.6) | 10 (17.9) | 15 (28.3) | 7 (31.8) | 4 (28.6) | 4 (33.3) | ||

| 2015 | 69 (19.9) | 32 (14.9) | 6) (10.7) | 11 (19.6) | 5 (9.4) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| 2016 | 33 (9.5) | 6 (2.8) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.9) | |||||

| Region (number of SR (%)) | ||||||||||

| Europe | 233 (67.3) | 95 (44.2) | 14 (25) | 20 (35.7) | 34 (64.2) | 12 (54.5) | 13 (92.9) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (100) | |

| North America | 26 (7.5) | 88 (40.9) | 33 (58.9) | 27 (48.2) | 10 (18.9) | 6 (27.3) | 1 (7.1) | 10 (83.3) | 1 (100) | |

| Asia | 49 (14.2) | 16 (7.4) | 6 (10.7) | 3 (5.4) | 3 (5.7) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (8.3) | |||

| Australia/New Zealand | 19 (5.5) | 14 (6.5) | 2 (3.6) | 6 (10.7) | 6 (11.3) | |||||

| South America | 13 (3.8) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.8) | |||||||

| Africa | 6 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (4.5) | |||||||

| Review type (number of SR (%)) | ||||||||||

| Study-level data | 331 (95.7) | 147 (68.4) | 39 (69.6) | 40 (71.4) | 35 (66) | 19 (86.4) | 1 (7.1) | 11 (91.7) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| IPD | 3 (0.9) | 67 (31.2) | 17 (30.4) | 15 (26.8) | 18 (34) | 3 (13.6) | 13 (92.9) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Both | 12 (3.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.8) | |||||||

| Network meta-analysis (number of SR (%)) | 2 (0.6) | 6 (2.8) | 3 (5.4) | 3 (5.7) | ||||||

| Study type (number of SR (%)) | ||||||||||

| RCT | 264 (76.3) | 75 (34.9) | 15 (26.8) | 21 (37.5) | 14 (26.4) | 7 (31.8) | 12 (85.7) | 5 (41.7) | 1 (100) | |

| non-RCT | 5 (1.4) | 85 (39.5) | 27 (48.2) | 16 (28.6) | 27 (50.9) | 12 (54.5) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Both | 77 (22.3) | 46 (21.4) | 9 (16.1) | 19 (33.9) | 9 (17) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (7.1) | 5 (41.7) | ||

| Unclear | 9 (4.2) | 5 (8.9) | 3 (5.7) | 1 (100) | ||||||

| Population (number of SR (%)) | ||||||||||

| Adult | 318 (9.9) | 151 (70.2) | 39 (69.6) | 43 (76.8) | 32 (60.4) | 14 (63.6) | 13 (92.9) | 9 (75) | 1 (100) | |

| Paediatric | 26 (7.5) | 6 (2.8) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.8) | 4 (7.5) | |||||

| Both | 2 (0.6) | 22 (10.2) | 5 (8.9) | 6 (10.7) | 7 (13.2) | 4 (18.2) | ||||

| Unclear | 36 (16.7) | 11 (19.6) | 6 (10.7) | 10 (18.9) | 4 (18.2) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (25) | 1 (100) | ||

| Included studies (median (IQR)) | 6 (2-13) |

18 (10-38,8) |

20 (12–43.8) |

16 (9–36.3) |

24 (12.8–44.8) |

16 (9.6–26.5) |

16 (25–9.8) |

16.5 (10.3–24.8) |

14 | 37 |

| Included patients (median (IQR)) | 1020 (194.5–2845) |

7730 (3288–29423) |

8216 (3288–35568) |

4758.5 (184.5–11 091.8) |

4600 (3033–21137) |

1 17 597 (10 903–890992.3) |

21 471.5 (13 287.5–45 195.8) |

12 813.5 (4075.5–48 067.3) |

3377 | Not reported |

| Citations (median (IQR)) | 3 (1-7) |

46 (18.5–86.5) |

30.5 (9.8–55.3) |

48.5 (18–70.3) |

40 (22-97) |

40 (15–80.3) |

157 (54–351.8) |

101 (45.3–155.8) |

8 | 15 |

CA Cancer J Clin, A Cancer Journal for Clinicians; Cancer Res, Cancer Research; IPD, individual patient data; J Clin Oncol, Journal of Clinical Oncology; J Natl Cancer Inst, Journal of the National Cancer Institute; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SR, systematic review.

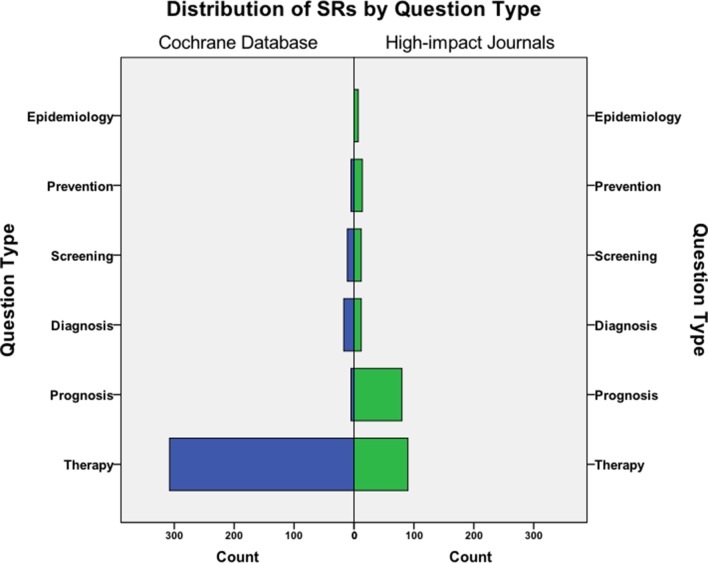

Cochrane reviews predominantly investigated therapeutic (89%; 308/346) questions. Among SRs from high-impact journals, there was also a large number of prognostic reviews (37.2%; 80/215) in addition to therapeutic reviews (41.9%; 90/215; figure 4). Overall, Cochrane reviews were less likely to include non-randomised controlled trials (RR 0.04; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.09). Therapeutic reviews published in the CDSR primarily included randomised controlled trial (RCTs) in 78.6% (242/308) or both RCTs and non-RCTs in 21.1% (65/308). High-impact journal reviews assessing therapeutic questions were primarily based on RCTs (58.9% (53/90)), with only 26.7% (24/90) based on non-RCTs.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Cochrane reviews and high-impact journal SRs by review question. SR, systematic review.

Content of included SRs

91.9% (318/346) of the Cochrane reviews and 70.2% (151/215) of high-impact journal SRs focused on adult study populations. Only 7.5% (26/346) of SRs from the CDSR and 2.8% (6/215) of reviews from high-impact journals focused solely on paediatric patients.

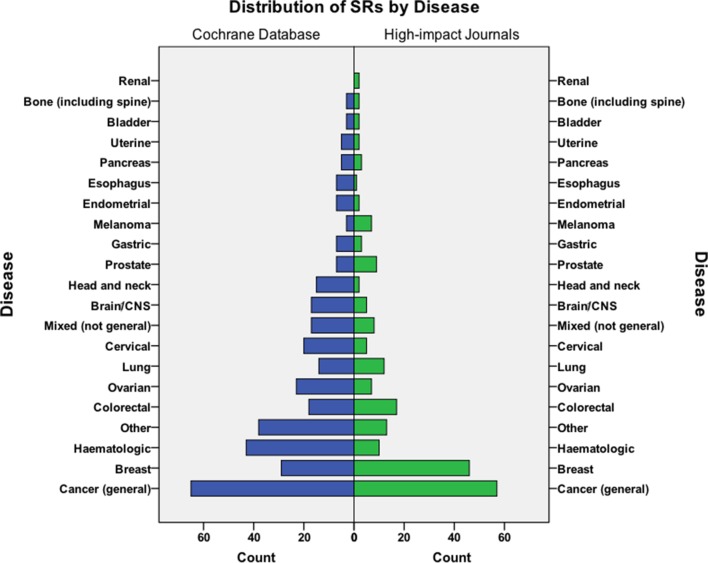

The largest group of Cochrane reviews addressed general cancer topics (eg, supportive measures for patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy) not limited to a specific type of disease (18.8%; 65/346), followed by SRs concerning haematological malignancies (12.4%; 43/346), and breast cancer (8.4%; 29/346; figure 5). Among SRs published in high-impact journals, general cancer topics was also the main category followed by breast cancer in 21.4% (47/215) and colorectal cancer in 7.9% (17/215).

Figure 5.

Distribution of Cochrane reviews and high-impact journal SRs by disease. SR, systematic review.

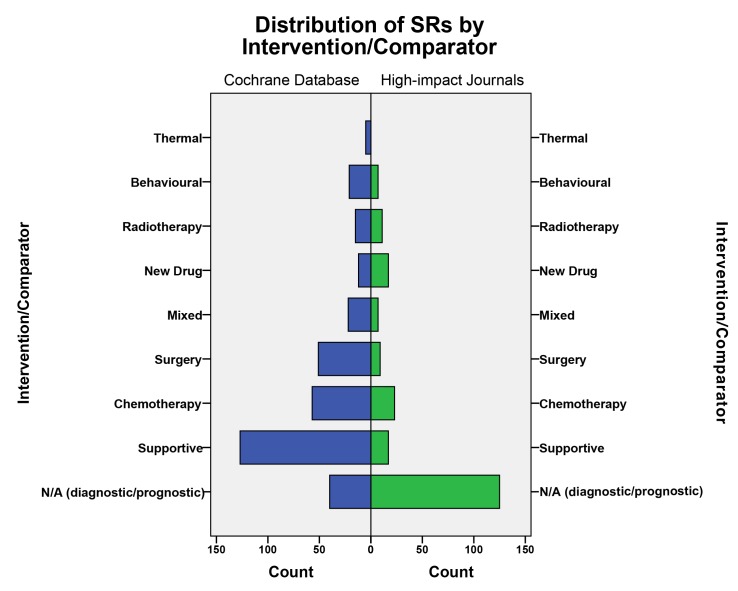

SRs published in Cochrane most commonly examined supportive care interventions (40.3%; 126/313), followed by chemotherapy (20.1%; 63/313), and surgery (16.7%; 49/313; figure 6). Reviews in high-impact journals, on the other hand, predominantly evaluated specific chemotherapy regimens (25.3%; 23/91), new drugs (18.7%; 17/91) and supportive care interventions (18.7%; 17/91).

Figure 6.

Distribution of Cochrane reviews and high-impact journal SRs by intervention. N/A, not applicable; SR, systematic review.

Overall, Cochrane reviews included fewer studies per review than high-impact journal SRs (median: six studies (IQR: 2–13) compared with 18 (18–38.8)) and fewer patients (1020 (194.5–2845) compared with 7730 (3288–29.423)). About 11.3% (39/346) of Cochrane SRs were so-called ‘empty reviews’, meaning the authors could not identify eligible studies to include in their review. Furthermore, 35 (10.1%) reviews retrieved from the CDSR included only one study. In contrast, none of the SRs in high-impact journals were empty or contained only a single study.

Citations

Cochrane reviews were cited considerably less frequently than SRs published in high-impact medical journals. The mean number of citations for Cochrane reviews was 6.92, ranging from 0 to 143. High-impact journal SRs had a mean of 74.45 citations with a range from 0 to 652.

Discussion

Principal findings

This methodological assessment found that Cochrane reviews were conducted with greater methodological rigour than SRs published in high-impact journals but were cited less frequently. The largest gap in terms of methodological quality with regard to an individual AMSTAR criterion was the reporting of excluded studies, which was met by all Cochrane reviews and only 11.2% (24/215) of SRs published by high-impact journals. Other major differences relate to the reporting of possible conflicts of interest of included studies, the existence of an a priori design, the conduct of sensitivity analyses for study quality of included studies and the inclusion of non-published studies. High-impact SRs were more likely to be based on IPD, include non-RCTs and address questions other than therapy, namely prognosis. SRs that included only one or no included studies were published exclusively in the Cochrane Library, and not in high-impact journals.

Strengths and weaknesses of this SR

We performed this study based on an a priori protocol, a comprehensive search strategy and data abstraction in duplicate, which lends strength to the validity of our findings. In addition, we performed a clinical content analysis comparing the two groups of SR sources. The reliability of this work was ensured through adherence to the review methods proposed by PRISMA and Cochrane. Our quality assessment was based on AMSTAR, an instrument previously validated for the assessment of SRs from RCTs which represented the best available tool at the time when we planned and conducted this review.16 17 An updated version of AMSTAR has only recently become available.18

Given its focus on methodological quality, this study is unable to explain the missing link between the high methodological quality of Cochrane reviews and relatively low citation rates. Potential explanations may relate to the clinical topic areas, and too great a focus on evidence from RCTs, which has long been a hallmark of Cochrane reviews. In addition, Cochrane reviews that include none (‘empty reviews’) or only one study are less likely to provide newsworthy results and yield high citation rates.

The Cochrane Library permits copublication of Cochrane reviews in other journals, which is however subject to formal preapproval. A large number of copublished reviews could have potentially biased our results, though we identified only two reviews with this issue; thus, this concern is only of minor relevance.19 20

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other SRs

In 2016, a cross-sectional assessment of SRs was published which included a similar comparison of Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews.5 This assessment was cross-disciplinary and not limited to cancer alone. It consisted of SRs published during a 1-month period in 2014, and only 3% (9/300) of the total assessed SRs came from journals with an impact factor exceeding 10. Most of the randomly selected SRs and Cochrane reviews investigated therapeutic questions. Similar to our study, Cochrane reviews were more likely to fulfil the important methodological criteria such as protocol availability, the inclusion of unpublished and grey literature, an electronic data search in more than two databases, data extraction and study selection performed in duplicate or the assessment of study quality. Findings were also similar with regard to the proportion of reviews that did not perform a sensitivity analysis based on study quality.5 Another similar study by Moher et al documented improved reporting over a 10-year timeframe.4 A variety of other reports, including assessments in other medical research fields, have identified similar deficiencies in the quality of SRs but none of them have specifically focused on oncology-related reviews.6 16 21–26

Meaning of this methodological SR: explanations, implications and further research

Our methodological assessment highlights the major differences that exist among published SRs in oncology. Users of the medical literature should therefore not assume that SRs are equivalent in their design, methodological rigour or validity of their conclusions. Quality criteria for SRs are well established; one key criterion is that of an a priori protocol which governs all aspects of the review process to prevent selective or biased reporting and avoid duplicate publication.27–30 Registration of protocols with platforms such as PROSPERO can aid in holding SRs accountable in this regard; some journals have made this mandatory.31 Deficits in the disclosure of excluded studies, for example, narrow the transparency of study selection, while absence of sensitivity analyses impedes the possibility of readers to assess the findings against the background of study quality. Conflicts of interest may also play a role in the heterogeneity of published SRs.

A practical reason for differences in the reporting quality between Cochrane reviews and high-impact medical journals may lie in the limited space for reporting provided in printed medical journals. A recent assessment of meta-analyses of surgical interventions supports the assumption of the negative association between limited publication space and completeness of reporting.25 Cochrane does not impose space restrictions and as such Cochrane SR authors have more freedom to provide complete reporting. However, given that most journals now offer the opportunity to provide additional e-content on the internet, there should be fewer reasons for less than complete transparency. In this assessment, we took care to include all available content, including online supplementary tables and appendices in our assessment. Published Cochrane reviews typically also undergo a more rigorous development process that includes the compulsory publication of a protocol that has previously undergone internal editorial review and external peer review as specified in the organisation’s MECIR policy. This may be the main reason why Cochrane reviews are much more likely to meet more of the requirements of transparent reporting checklists.1 7 32 33 Journal editors should similarly mandate strict adherence to PRISMA and other reporting guidelines.

Given the considerable investment of resources that goes into development of high-quality Cochrane reviews, their relatively low impact is a concern. It appears critically important that Cochrane editors take greater initiative at directing review authors to topics where the greatest clinical interest lies.

This work demonstrates the need to critically assess SRs prior to using their evidence. For clinicians, the Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature by Murad et al 30 provides a practical framework for assessing the validity, impact and applicability of SRs. For researchers and policy-makers aside from AMSTAR, the recently introduced ROBIS tool allows to comprehensively evaluate possible risk of bias in SRs at the review level.34 At present, it covers SRs with interventional, diagnostic, prognostic and aetiological review questions and involves a three-domain appraisal of the relevance of the respective review, an evaluation of possible risks of bias during the review process and a concluding judgement of overall risk of bias of the review findings.34

Conclusion

Cancer-related SRs that are published in the CDSR demonstrate higher adherence to methodological and reporting standards than cancer-related SRs published in high-impact medical journals but are cited less frequently. Our assessment underscores the importance of performing a critical appraisal of SRs before including their evidence into guideline development or making individual clinical decisions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MG designed the data collection tools and analysis, selected studies, analysed and extracted data, and drafted and revised the paper. VMN designed the data collection tools and analysis, selected studies, analysed and extracted data, and drafted and revised the paper. AW extracted and analysed the data and revised the paper. PD initiated the project, designed the data collection tools and analysis, selected studies, monitored data collection and analysis, and revised the paper. NS initiated the project, designed the data collection tools and analysis, selected studies, monitored data collection and analysis, and revised the paper. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Funding: Two authors received travel grants by Cochrane to attend and present data at the 23rd Cochrane Colloquium in Seoul, 2016. This research received no other specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MG, AW and NS are part of Cochrane Haematological Malignancies, PD is part of Cochrane Urology.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. 2015 Journal Citation Reports®: Clarivate Analytics. 2017.

- 2. Woolf S, Schünemann HJ, Eccles MP, et al. . Developing clinical practice guidelines: types of evidence and outcomes; values and economics, synthesis, grading, and presentation and deriving recommendations. Implement Sci 2012;7:61 10.1186/1748-5908-7-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mulrow CD. Rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994;309:597–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moher D, Tetzlaff J, Tricco AC, et al. . Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLoS Med 2007;4:e78 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. . Epidemiology and Reporting Characteristics of Systematic Reviews of Biomedical Research: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002028 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Han JL, Gandhi S, Bockoven CG, et al. . The landscape of systematic reviews in urology (1998 to 2015): an assessment of methodological quality. BJU Int 2017;119:638–49. 10.1111/bju.13653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. . Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:10 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. . Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flaherty KT, Hennig M, Lee SJ, et al. . Surrogate endpoints for overall survival in metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:297–304. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70007-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. . Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: the Patient Navigation Research Program. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106 dju115 10.1093/jnci/dju115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lemieux J, Goodwin PJ, Bordeleau LJ, et al. . Quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer: an updated systematic review (2001-2009). J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:178–231. 10.1093/jnci/djq508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paoletti X, Oba K, Bang YJ, et al. . Progression-free survival as a surrogate for overall survival in advanced/recurrent gastric cancer trials: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:1667–70. 10.1093/jnci/djt269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Péron J, Pond GR, Gan HK, et al. . Quality of reporting of modern randomized controlled trials in medical oncology: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:982–9. 10.1093/jnci/djs259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zikos E, Ghislain I, Coens C, et al. . Health-related quality of life in small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review on reporting of methods and clinical issues in randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:e78–e89. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70493-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henson L, Gao W, Higginson I, et al. . Emergency department attendance by patients with cancer in the last month of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2015;385:S41 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60356-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, et al. . AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1013–20. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shea BJ, Bouter LM, Peterson J, et al. . External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR). PLoS One 2007;2:e1350 10.1371/journal.pone.0001350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. . AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kong A, Johnson N, Kitchener HC, et al. . Adjuvant radiotherapy for stage I endometrial cancer: an updated Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:1625–34. 10.1093/jnci/djs374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kong A, Johnson N, Kitchener HC, et al. . Adjuvant radiotherapy for stage I endometrial cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2012;4:Cd003916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fleming PS, Koletsi D, Seehra J, et al. . Systematic reviews published in higher impact clinical journals were of higher quality. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:754–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bafeta A, Trinquart L, Seror R, et al. . Analysis of the systematic reviews process in reports of network meta-analyses: methodological systematic review. BMJ 2013;347:f3675 10.1136/bmj.f3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cullis PS, Gudlaugsdottir K, Andrews J. A systematic review of the quality of conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in paediatric surgery. PLoS One 2017;12:e0175213 10.1371/journal.pone.0175213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fleming PS, Seehra J, Polychronopoulou A, et al. . Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews in leading orthodontic journals: a quality paradigm? Eur J Orthod 2013;35:244–8. 10.1093/ejo/cjs016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adie S, Ma D, Harris IA, et al. . Quality of conduct and reporting of meta-analyses of surgical interventions. Ann Surg 2015;261:685–94. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Windsor B, Popovich I, Jordan V, et al. . Methodological quality of systematic reviews in subfertility: a comparison of Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews in assisted reproductive technologies. Hum Reprod 2012;27:3460–6. 10.1093/humrep/des342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Kirkham J, et al. . Bias due to selective inclusion and reporting of outcomes and analyses in systematic reviews of randomised trials of healthcare interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;10:Mr000035 10.1002/14651858.MR000035.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stewart L, Moher D, Shekelle P. Why prospective registration of systematic reviews makes sense. Syst Rev 2012;1:7 10.1186/2046-4053-1-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murad MH, Montori VM, Ioannidis JP, et al. . How to read a systematic review and meta-analysis and apply the results to patient care: users' guides to the medical literature. JAMA 2014;312:171–9. 10.1001/jama.2014.5559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dahm P. Raising the bar for systematic reviews with Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR). BJU Int 2017;119:193–93. 10.1111/bju.13754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. The Cochrane Collaboration. Higgins JG S, ed Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chandler J, Tovey D, Churchill R, et al. . Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews. London: Cochrane, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, et al. . ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:225–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020869supp001.pdf (454.4KB, pdf)