Abstract

Introduction

Numerous studies have identified the importance of parenting behaviors to the wellbeing of children with chronic physical conditions. Synthesizing the findings of these studies has potential to identify which parenting behaviors are associated with specific aspects of child wellbeing.

Methods

We retrieved research reports addressing the relationship between parenting behaviors and wellbeing in children with chronic physical conditions and categorized parenting behaviors based on Skinner’s (2005) core dimensions of parenting (warmth, rejection, structure, chaos, autonomy support, and coercion) Through meta-analysis, we examined relationships between parenting dimension and child wellbeing variables.

Results

54 reports from 47 unique studies met inclusion criteria. Parent warmth was associated with less child depression, better quality of life, better physical functioning, and fewer externalizing behavior problems. Parent rejection was associated with more child depression, internalizing/externalizing behavior problems, and poorer physical functioning. Parent structure was associated with better child physical functioning. Parent chaos was associated with poorer child physical functioning. Parent autonomy support was associated with better quality of life and fewer externalizing behavior problems. Parent coercion was associated with more child depression, poorer quality of life, poorer physical function, and more internalizing behavior problems.

Conclusion

The results identify multiple, potentially modifiable parenting dimensions associated with wellbeing in children with a chronic condition, which could be targeted in developing family-focused interventions. They also provide evidence that research using Skinner’s core dimensions could lead to conceptualization and study of parenting behaviors in ways that would enable comparison of parenting in a variety of health and sociocultural contexts.

Keywords: meta-analysis, systematic review, parenting, child wellbeing, chronic illness

Introduction

Childrearing is a challenging undertaking for all parents, but parents of children with chronic physical conditions (CPC) face additional challenges related to their child’s special needs such as incorporating a complex treatment regimen into family life, advocating on the child’s behalf to school and health care personnel, and acting to ensure the child’s optimal development and quality of life (Barlow, & Ellard, 2006; Raina, et al., 2004). Described as “parenting plus” by Ray (2002) and “vigilant parenting” by Meakins, Ray, Hegadoren, Rogers, and Rempel (2015), parenting a child with a CPC involves integrating ordinary parenting behaviors not directly linked to the child’s special needs (e.g., supervising a child on a playground) with extraordinary parenting behaviors specific to the management of the child’s condition (e.g., monitoring a diabetic child’s blood glucose).

A substantial body of research describes the extraordinary challenges parents encounter and strategies they develop to care for a child with a CPC (Coffey, 2006). Less attention has been directed to studying ordinary aspects of parenting a child with a CPC (e.g., expressing affection, disciplining). Although acknowledging differences in ordinary and extraordinary parenting behaviors, Meakins and colleagues (2015) reported that the underlying dimensions were similar, and Mooney-Doyle and Deatrick (2016) concluded that despite the extraordinary work of parenting a child with a serious illness, parents described both the ordinary and extraordinary as part of the expected work of parenting.

Studies addressing the underlying dimensions of parenting a child with a CPC have focused on comparing parents of a child with a CPC to those of parents of healthy children. Through meta-analysis of 325 reports, Pinquart (2013) identified differences between the two groups, with parents of children with a CPC demonstrating less parental warmth, more demandingness, and more overprotection than parents of healthy children. Although identifying differences, the analysis did not link these underlying parenting dimensions to child wellbeing variables. Examination of these linkages is needed to determine if observed differences reflect positive adaptions by parents of children with a CPC or problematic parenting behaviors that put children at risk. Recognizing that both ordinary and extraordinary parenting behaviors are grounded in common underlying parenting dimensions, the aim of this analysis was to synthesize the research on the relationship between these dimensions and child wellbeing.

The organizing framework for examining parenting behaviors was Skinner, Johnson, and Snyder’s (2005) conceptualization of dimensions of parenting. Based on a review of parenting studies published between 1941 and 2001. Skinner et al. identified six core dimensions of parenting: warmth, rejection, structure, chaos, autonomy support, and coercion (Table 1).

Table 1.

Core Dimensions of Parenting

| Dimensions: | Definition |

|---|---|

| Warmth | Expression of love & caring, acceptance, kindness, regard |

| Rejection | Expression of active dislike, hostility, harshness, derision, disapproval, over- reactivity, explosiveness |

| Structure | Predictable, consistent, & clear expectations, guidelines, and rules for mature behavior; consistent & appropriate limit-setting, firm control |

| Chaos | Inconsistent, erratic, unpredictable, undependable behavior, lax control |

| Autonomy Support | Allows freedom of expression & action; encourages independent problem-solving, active participation in decision-making; communicates respect & deference for child opinions |

| Coercion | Restrictive, over-controlling, intrusive, strict obedience demanded, punitive discipline, psychological control, autocratic |

Note: adapted from Skinner et al. 2005.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

This systematic review and meta-analysis is part of the NIH-funded Family Synthesis Study, a mixed-methods project (Sandelowski, Voils et al. 2013) designed to map the intersection of family life and childhood CPCs through a series of syntheses. Our presentation is guided by the checklist for reporting reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies proposed in Stroup et al. (2000).

In the Family Synthesis Study, chronic physical condition (CPC) was defined as lasting or expected to last at least one year and producing or expected to produce sequelae for the child such as limitation in function/activity, medication dependency and/or need for medical care or related services beyond what is usual for a child of the same age (Bethell et al. 2014). A detailed account of the search process and the investigators’ conceptualization of family research are reported elsewhere (Havill et al. 2014, Knafl et al. 2015, http://familysynthesis.unc.edu/home). Briefly, nine databases were searched for English-language reports published between January 1, 2000 and March 31, 2014 using general search terms for family, child, and chronic condition in addition to search terms for specific diseases (e.g. arthritis, diabetes) resulting in 1,028 reports that met inclusion criteria and were entered into the Family Synthesis Study database.

Data were extracted from all reports in the Family Synthesis Study database using a standardized template that captured characteristics of the sample, study design, measures, and findings. One member of the research team extracted data from each report and a second member checked it for accuracy and completeness against the published report. Divergent interpretations of what should be included in an extraction were resolved through discussion with a third team member.

A strength of the Family Synthesis Study is the comprehensiveness of its search, which provided a database of publications that could be synthesized to address multiple different research questions. Prior analyses have addressed the relationship between family functioning and child wellbeing (Leeman, Crandell, Lee, Bai, Sandelowski, & Knafl, 2016), the transition of condition management from parent to child in children with Cystic Fibrosis (Leeman, Sandelowski, Havill, & Knafl, 2015), and the positioning of family in intervention studies (Knafl, Havill, Leeman, Fleming, Crandell, & Sandelowski, 2016). This analysis is distinct in its focus on parenting.

For the present analysis, we searched the Family Synthesis Study database for reports assessing the relationship between parent role performance and child wellbeing. Parent role performance was defined as parenting style (e.g. authoritarian, permissive) or parenting behavior(e.g. acceptance, control). Child wellbeing was defined as child physical functioning (e.g. metabolic control for a child with diabetes, respiratory function for a child with asthma) or psychosocial health and functioning (e.g. anxiety, depression).

Quality appraisal

In a review of guidelines for quality assessment in observational studies, Sanderson et al. (2007) noted three fundamental quality domains: appropriate selection of participant, appropriate measure of variables, and appropriate control for confounding. While control for confounding is most relevant to syntheses with a specific hypothesis about a single exposure and outcome, the other two domains are an appropriate basis for our quality assessment. Additionally, observational studies are prone to reporting bias, where non-significant relationships are not mentioned. Guidelines for reporting observational studies (von Elm et al, 2007) recommend that statistical tests be reported for all planned analyses, regardless of statistical significance. Based on these guidelines, each report was assessed for the following internal and external validity threats: reporting bias (selective reporting of results), non-representative sampling (low response rates, not representative of target population), and approach to measurement (validity, reliability) (Sanderson et al. 2007; von Elm et al. 2007).

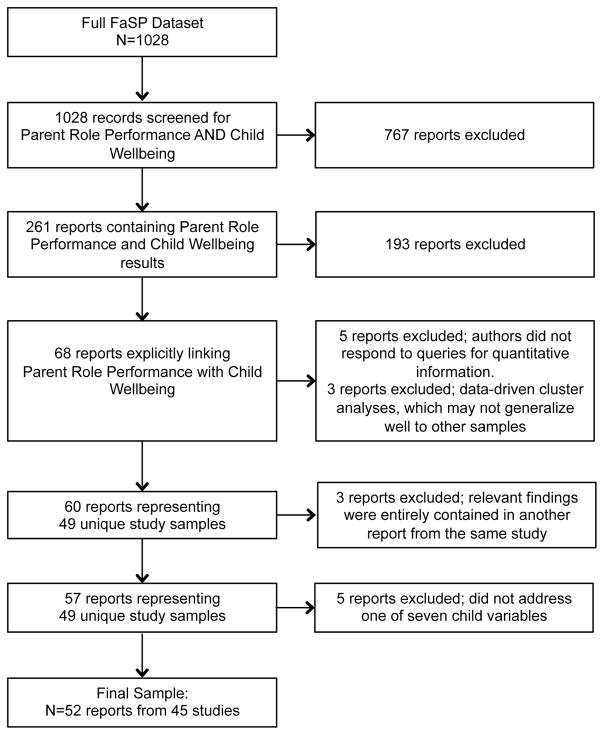

Five reports were excluded (see Figure 1) because insufficient numerical data were available. Potential reporting bias was identified in one of the remaining studies, where quantitative details about the relationship between one parent and child dimension was not available. Twenty-five of the 52 included studies reported information on participation; the average participation rate was 67% (SD=22%, range=21–100%). Where information was provided on sample representativeness, participants tended to be less sick with lower sociodemographic risk than non-participants. There was little evidence of measurement concerns, with the most notable being a lack of evidence of psychometric validation for some instruments. Although there are imperfections, each individual report had enough merit to warrant inclusion, and no report was excluded for reasons of quality.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for study of the relationship between parenting and child well-being.

Synthesis

We identified 68 reports that addressed at least one parent role performance/child wellbeing link. Using authors’ description of the variables and the measures used in the studies, two members of the research team independently grouped parent role performance variables within each of Skinner et al.’s (2005) six dimensions and grouped child wellbeing variables to create a parsimonious list of dimensions of wellbeing. Disagreements were resolved through further discussion with the research team to reach consensus. Table 1 provides an overview of the six parenting dimensions, including definitions and variables. We grouped child wellbeing into five dimensions: anxiety, depression, physical functioning, overall quality of life (derived from a general or physical quality of life measure), psychosocial quality of life, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems.

Effect sizes were calculated for all findings linking parent role performance with child wellbeing. Authors were contacted to obtain missing quantitative information. These calculations were supported by the use of Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software v2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

We then clustered findings linking the same parenting dimension and child wellbeing dimension, including no more than one finding from each study within a cluster. When multiple findings within a cluster came from the same study population, we used the following criteria to choose a single effect size: (a) results from mothers as opposed to fathers (to promote comparability with other studies; mothers were by far the dominant parent studied.); (b) results from child-reported over parent-reported measures; (c) results derived from general over disease-specific measures and (d) results from the largest sample in cases of multiple reports from the same parent study where the variables addressed were the same and the samples were overlapping but not identical. In addition, because findings were overwhelmingly cross-sectional, we excluded results where there was a time lag between the parent and child variables.

Before synthesis, we reversed some of the effect sizes in order to maintain comparable interpretations across studies. For example, Rodenburg et al. (2013) and Greene et al. (2010) both studied the impact of chaotic parenting on physical functioning. Rodenburg et al. (2006) measured physical functioning using HbA1c in children with diabetes, with high scores indicating poorer physical functioning, but Greene et al. (2010) measured physical functioning in children with diabetes using a functional status measure, with high scores indicating better physical functioning. In these examples, a positive effect size would mean something different for each study. A uniform definition was needed, so we defined high scores on child physical functioning to indicate better functioning and thus changed the sign of the effect size (correlation) between chaotic parenting and HbA1c in Rodenburg et al. (2006). Similar reversals of signs were made for parent variables.

Because of different inclusion criteria, sampling procedures, measurement tools, and other sources of variation across studies, we expected heterogeneity in the effect sizes within each cluster of conceptually similar relationships between parent and child variables (Higgins & Green, 2011). To account for this heterogeneity, we used random-effects meta-analysis to generate our estimates. We also applied a commonly-used statistic for describing heterogeneity, I2, which quantifies the proportion of variability in effect sizes due to heterogeneity (as opposed to chance variability). We considered a cluster with an I2 of ≥ 50% in a random effects model to have “substantial heterogeneity” (Higgins & Green, 2011), requiring further examination before pooling. No cluster exceeded this limit (highest I2 was 11.4%).

Relationships between parent and child wellbeing dimensions were summarized by pooled correlation coefficients and p-values, with p<.05 considered statistically significant. For the purposes of interpretation, significant relationships were considered strong at or above 0.5; moderate from 0.3 to <0.5; and weak below 0.3 (Cohen, 1988).

Lastly, we explored the potential impact of publication bias on results by examining funnel plots and testing for asymmetry (Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider, and Minder, 1997).

Results

The final sample for this review included 52 reports from 45 unique studies. Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al. 2009) diagram detailing the search process beginning with the 1,028 reports in the Family Synthesis Study database.

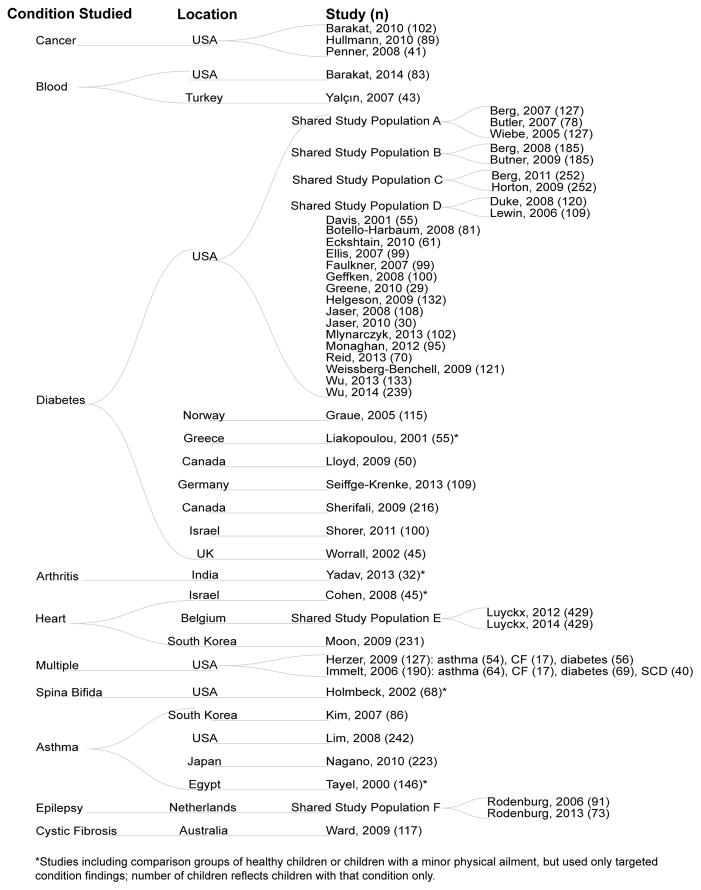

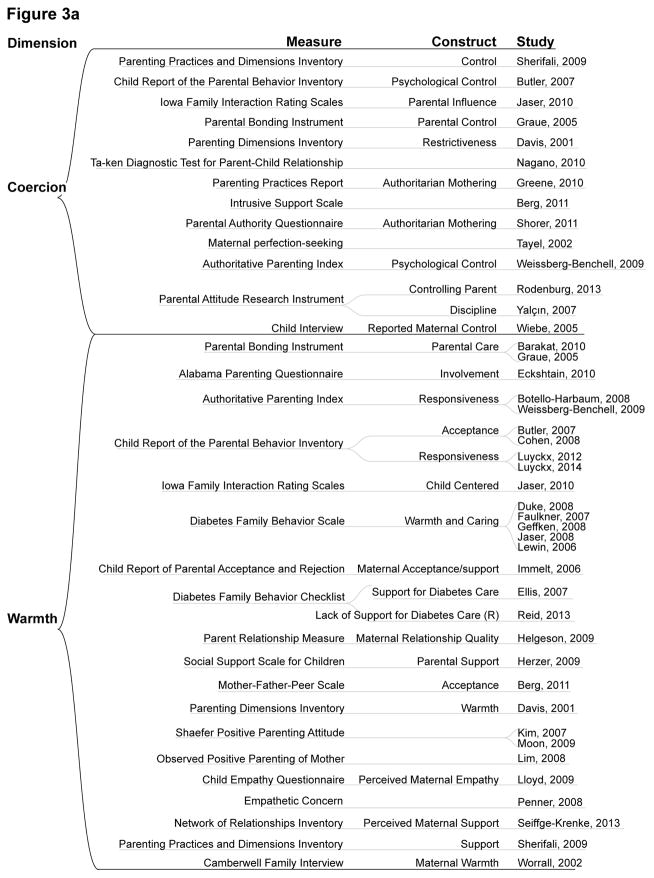

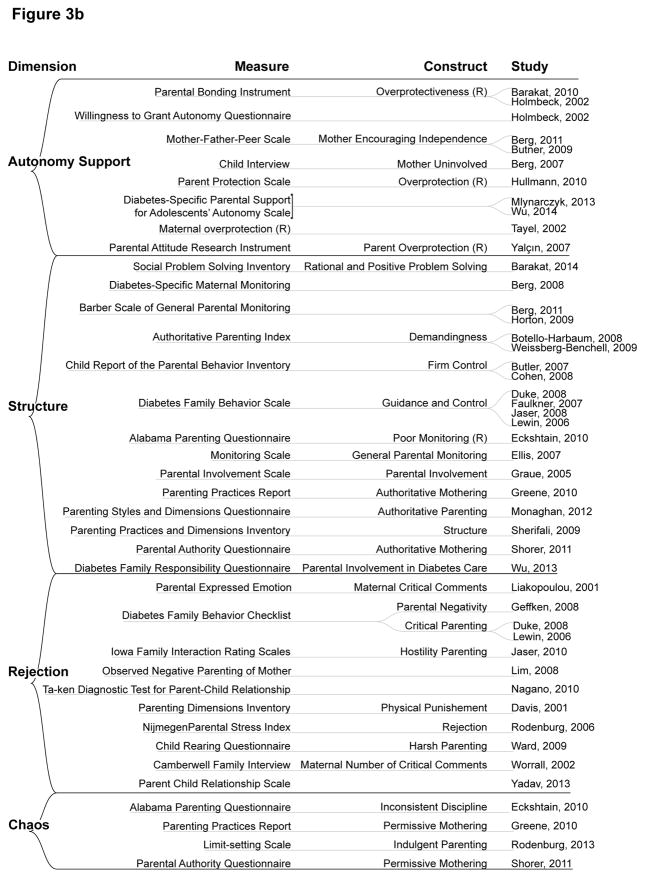

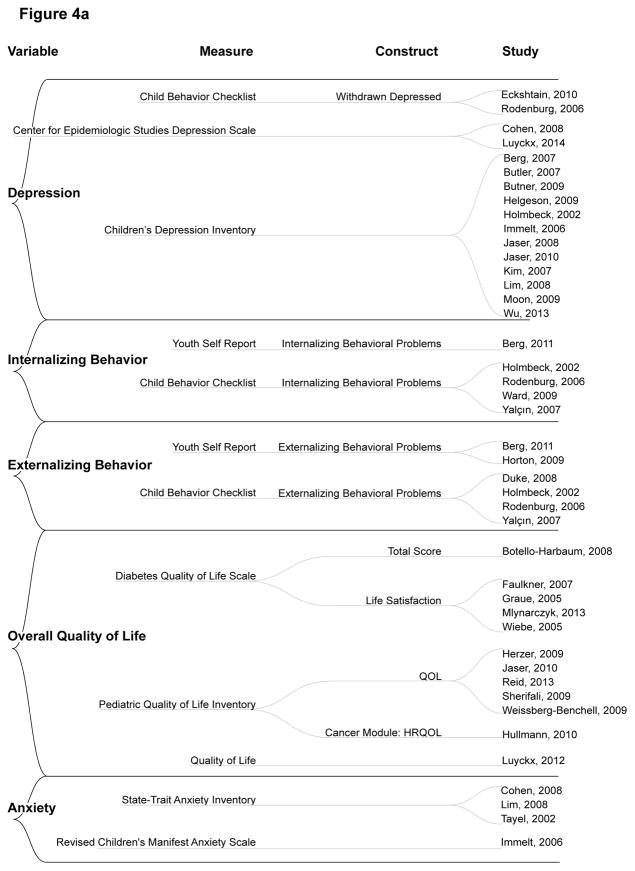

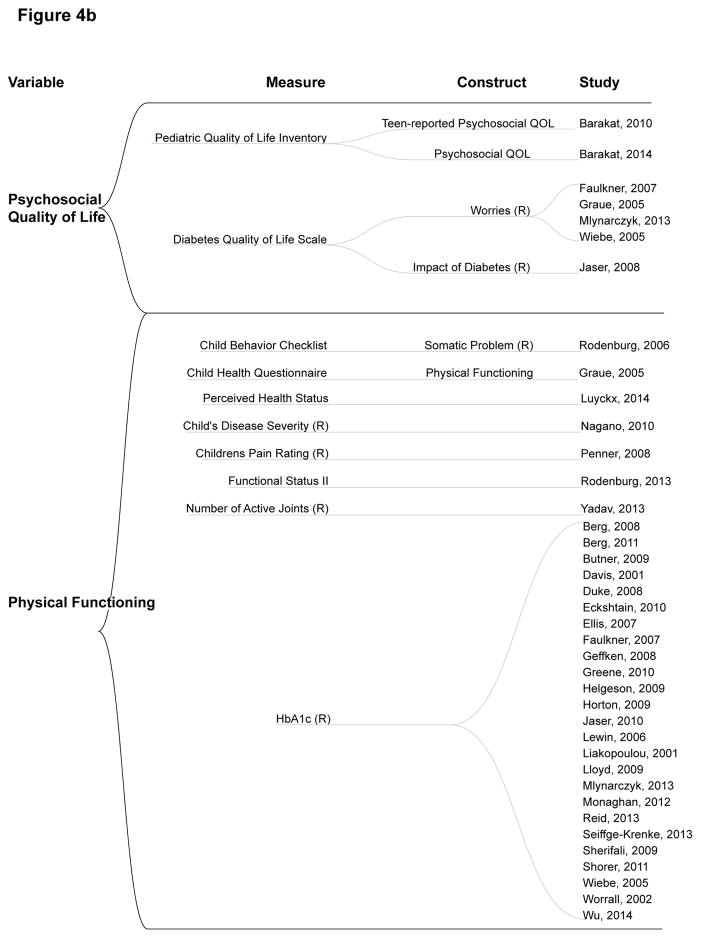

As shown in Figure 2, diabetes was the condition most often addressing parent role performance (30 of 52) reports. Of the 52 reports, 35 were from studies conducted in North America and 9 in Europe. Twenty-three studies were conducted by interdisciplinary teams composed of physicians, social scientists, nurses, educators, and/or public health professionals. Twenty-two studies identified investigators from a single discipline: medicine, social science, nursing, or public health. Figures 3 and 4 summarize the measures used to study each parenting and child wellbeing dimension. Warmth was the most studied parenting dimension, and the least studied was chaos. The most- and least-studied child wellbeing variables were physical functioning and anxiety, respectively. The most frequently studied parent-child relationship was between parental warmth and child physical functioning.

Figure 2.

Description of reports included in sample

Figure 3. Parent Dimensions with associated measures, constructs, and studies.

Note: (R)=reverse scored to maintain combinability with other measures.

Figure 4. Child wellbeing with associated measures, constructs, and studies.

Note: (R)=reverse scored to maintain combinability with other measures.

Summary of findings by parenting dimensions

Table 2 summarizes the relationships between parenting dimensions and child wellbeing. Although most effects are the result of pooling results across two or more studies, nine (e.g., the relationship between chaos and child depression) are from a single study. The empty cells in Table 2 show that not all relationships were studied.

Table 2.

Results for each Parent-Child Relationship Cluster: No. of Reports/Children, r(p)

| Parent dimensions | Child wellbeing variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Anxiety | Depression | QoL | Psych. QoL | Physical Functioning | Internalizing | Externalizing | |

| Warmth | 3/477, −0.15 (0.2) | 11/1632, −0.34 (<.001) | 9/1288, 0.26 (<.001) | 4/424, 0.35 (0.01) | 18/2132, 0.14 (0.001) | 1/252, −0.27 (<.001) | 2/372, −0.26 (<.001) |

|

| |||||||

| Rejection | 1/242, 0.12 (0.06) | 3/363, 0.35 (<.001) | 1/30, −0.13 (0.5) | 10/860, −0.25 (<.001) | 2/208, 0.4 (<.001) | 2/211, 0.46 (0.01) | |

|

| |||||||

| Structure | 1/45, −0.17 (0.27) | 5/425, 0.01 (0.95) | 5/632, 0.16 (0.13) | 4/405, 0.1 (0.06) | 12/1480, 0.16 (<.001) | 1/252, −0.11 (0.08) | 2/372, −0.08 (0.13) |

|

| |||||||

| Chaos | 1/61, 0.04 (0.76) | 4/263, −0.17 (0.01) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Autonomy Support | 1/146, −0.22 (0.04) | 3/380, −0.1 (0.56) | 2/191, 0.24 (<.001) | 2/204, −0.004 (0.96) | 4/778, 0.01 (0.86) | 3/363, −0.14 (0.15) | 2/320, −0.27 (<.001) |

|

| |||||||

| Coercion | 1/146, 0.22 (0.04) | 2/108, 0.33 (<.001) | 5/609, −0.21 (0.03) | 2/242, −0.2 (0.32) | 10/1220, −0.08 (0.01) | 1/252, 0.17 (0.01) | 2/295, 0.16 (0.29) |

Parent warmth and child wellbeing

Warmth had a moderate significant association with less child depression and better psychosocial quality of life. Warmth was weakly but significantly associated with better overall child quality of life, with better child physical functioning, and with fewer child externalizing behavior problems. Warmth had a weak but significant negative association with child internalizing behaviors, based on only one study. Warmth was not significantly associated with child anxiety.

Parent rejection and child wellbeing

Rejection was moderately and significantly associated with child depression, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems. Rejection was weakly but significantly associated with poorer child physical functioning and was not significantly associated with child anxiety or overall quality of life.

Parent structure and child wellbeing

Though relationships between structure and all child wellbeing variables were studied, the only significant relationship was a weak association with better child physical functioning.

Parent chaos and child wellbeing

Chaos was weakly but significantly associated with poorer child physical functioning and not significantly associated with child depression.

Parent autonomy support and child wellbeing

Autonomy support was weakly but significantly associated with better overall child quality of life, fewer externalizing behavior problems, and with lower child anxiety. Autonomy support was not significantly associated with depression, psychosocial quality of life, physical functioning, or internalizing behavior problems.

Parent coercion and child wellbeing

Coercion was moderately and significantly associated with child depression; it was weakly but significantly associated with poorer overall child quality of life and poorer physical functioning. Coercion was weakly but significantly associated with child anxiety and child internalizing behavior problems. Coercion was not significantly associated with child psychosocial quality of life or externalizing behavior problems.

Further details about each included report are available in Supplemental Table 1. Supplemental Figure 1 describes the authors’ disciplines and countries in which research was conducted, and Supplemental Figure 2 presents exactly which reports contributed to each result in Table 2.

Assessment of potential publication bias

An interpretable funnel plot should be based on at least 10 studies (Sterne et al., 2011), applying only to five of the results in Table 2. Evidence of asymmetry was found for two results: warmth and physical functioning (p=.004) and coercion and physical functioning (p=.02). Using the trim and fill method (Duval and Tweedie, 2000), estimates of true effects are r=.06 and −.05 respectively, compared to r=.14 and −.08 in Table 2, with warmth remaining statistically significant but coercion having p>.05.

Discussion

This meta-analysis deepens our understanding of factors contributing to the wellbeing of children with a CPC by addressing how specific dimensions of parenting were related to various aspects of child wellbeing. The sample included studies examining a diverse array of parenting dimensions, but investigators directed relatively more attention to parental warmth (30 studies) and structure (20 studies) than the other dimensions. In view of parents’ key role in preparing children to assume increasing responsibility for managing the treatment regimen (Allen, Channon, Lowes, Atwell, & Lane, 2011; Anderson, et.,al, 2009; Dupuis, Duhamel, & Gendron, 2011), it was surprising that relatively few studies (N=10) addressed autonomy support, especially given the number of studies of children with diabetes. Regarding child wellbeing, physical functioning was the dimension studied most frequently (32 studies), with fewer investigators studying quality of life (20 studies), psychological functioning (18 studies of anxiety or depression), and problematic behaviors (11 studies). There was a notable absence of studies addressing more positive aspects of child functioning such as self-efficacy and resilience and parents’ contributions to enhancing children’s strengths and capabilities.

All six of Skinner’s core dimensions of parenting were significantly related to one or more child wellbeing variables, but all effect sizes were in the weak to moderate range. Thus, although the analysis provides evidence that general dimensions of parenting can both foster and impede optimal child wellbeing, the weak to moderate strength of the relationships points to the importance of addressing a a broader array of variables influencing child wellbeing.

The results are interesting in terms of Pinquart’s (2013) findings that parents of a child with a CPC had lower levels of responsiveness (warmth) and higher levels of demandingness (coercion) and overprotection (lack of autonomy support) than parents of healthy children. Our analysis identified warmth and coercion as parenting dimensions consistently associated with child wellbeing. These results provide insights as to which differences identified by Pinquart are especially salient because of their relationship to child wellbeing. As such, they are likely targets for interventions aimed at enhancing parents’ capacity to address the parenting challenges of raising a child with a CPC. However, more research would be needed to determine optimal levels of these variables and how these might differ over time or across conditions

Most research testing interventions for parents of a child with a CPC has focused on increasing parents’ knowledge and skill set related to adhering to the treatment regimen. Far less attention has been directed to addressing parenting styles and behaviors (i.e., parent role performance). In our prior review (Knafl et al., 2016) of 70 family-focused interventions involving children with a CPC, we found that the majority of the interventions engaged parents in order to improve their ability to manage treatments, with relatively few addressing parent role performance. Johnson, Kent, and Leather (2005) have highlighted the need for effective family therapy interventions, especially those addressing parenting in healthcare settings. Also needed are studies that address possible moderators of parenting behaviors so that interventions might be tailored to family structure, child developmental level, and condition type. Adaptive intervention designs such as MOST (Multiphase Optimization Strategy) allow investigators to adapt interventions to the unique characteristics of patients and family members that moderate intervention efficacy. As such, they provide promising options for testing complex, multifaceted interventions (Collins, 2013).

Limitations

Like any synthesis of research findings, the findings from this analysis are constrained by limitations in the studies included in the analysis. Most challenging was the variation in the way the same concept, such as warmth or rejection, was used in the primary research reports to mean different things. In some cases, the same measuring tools or portions thereof were used to represent different concepts. We used our best judgment in discerning what authors intended and what the measure addressed in grouping parent role performance and child wellbeing relationships, and the heterogeneity analysis provided evidence that the groupings were conceptually meaningful. However, in their review of 164 parenting measures, Hurley and colleagues (2014) raised serious concerns about the psychometric underpinnings of most. Their detailed description of the focus and characteristics of the 25 measures for which some psychometric data were available is an excellent resource for investigators and clinicians. Alderfer and colleagues’ (2008) review of family measures judged to be relevant for both clinicians and researchers is another excellent measurement resource. The inclusion of both parenting and family measures in future studies would serve to situate parenting behaviors in the broader context of family roles and relationships.

Although this review addressed a range of CPCs, diabetes was by far the most studied condition, limiting our ability to explore condition-specific differences in the studied relationships. We also were unable to address the influence of other possible moderators such as family structure or child’s developmental level on the relationship between parent role performance and child wellbeing.

There was considerable variation in the amount of data available for each parent dimension and/or child wellbeing variable. Thus, less-studied concepts (e.g. child anxiety or chaotic parenting) present with less statistical power to detect a relationship where one exists. Empty cells in Table 2 or cells with lower sample size and high p-values may reflect lack of research about the relationship rather than a complete lack of relationship.

There was some evidence of funnel plot asymmetry. In addition to being a symptom of publication or reporting bias, funnel plot asymmetry can be caused by chance, heterogeneity, or differing methodological quality in small vs. large studies (Sterne et al., 2011). We found no evidence of heterogeneity using I2, and the fixed effects estimates were similar to the random effects estimates, also discounting heterogeneity as a cause. The small number of studies in each synthesis make it possible that chance caused the funnel plot asymmetry, but we prefer to conservatively consider the effects as potential overestimates.

Conclusion

With these important caveats in mind, this review nevertheless supports the usefulness of a research agenda using core dimensions of general parenting as an organizing framework. Such an agenda would ensure that dimensions are worded and studied in comparable ways that enable systematic comparisons to be made of parenting in a wide variety of health, sociocultural, and national contexts. At the same time, it is important to bear in mind the family context in which parents enact their role and develop interventions that address or take into account this context. A research agenda allowing more systematic and precise comparisons to be made might assist researchers better to differentiate general from illness-specific parent dimensions (and to develop interventions more precisely targeted on specific clusters of general and illness-specific parent-child interactions.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Profile of Included Reports (N=52)

Supplemental Figure 1: Study Team Disciplines and Country

Supplemental Figure 2: Studies used for each child wellbeing/parent dimension relationship.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The Family Synthesis Study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research grant “Mixed-Methods Synthesis of Research on Childhood Chronic Conditions and Family” (R01 NR012445, 9/1 2011—6/30 2016).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Contributor Information

Jamie L. Crandell, Research Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing & Department of Biostatistics.

Margarete Sandelowski, Boshamer Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing.

Jennifer Leeman, Associate Professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing.

Nancy L. Havill, Research Associate, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing.

Kathleen Knafl, Frances Hill Fox Distinguished Professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing.

References (* included in synthesis)

- Alderfer MA, Fiese BH, Gold JI, Cutuli JJ, Holmbeck GN, Goldbeck L, et al. Evidence-based assessment in pediatric psychology: Family measures. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:1046–1061. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsmo83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D, Channon S, Atwell C, Lane C. Behind the scenes: The changing roles of parents in the transition from child to adult diabetes service. Diabetic Medicine. 2011;28:994–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BJ, Holmbeck G, Iannotti RJ, McKay SV, Lochrie A, Volkening L, et al. Dyadic measures of the parent-child relationship during the transition to adolescence and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Families, Systems, & Health. 2009;27(2):141–152. doi: 10.1037/a0015759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Barakat LP, Daniel LC, Smith K, Renée Robinson M, Patterson CA. Parental problem-solving abilities and the association of sickle cell disease complications with health-related quality of life for school-age children. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2014;21(1):56–65. doi: 10.1007/s10880-013-9379-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Barakat LP, Marmer PL, Schwartz LA. Quality of life of adolescents with cancer: Family risks and resources. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):63–63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Ellard D. The psychosocial wellbeing of children with chronic disease, their parents and siblings: An overview of the research evidence base. Child: Care Health & Development. 2006;32(1):19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Berg CA, Butler JM, Osborn P, King G, Palmer DL, Butner J, et al. Role of parental monitoring in understanding the benefits of parental acceptance on adolescent adherence and metabolic control of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):678–683. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Berg CA, King PS, Butler JM, Pham P, Palmer D, Wiebe DJ. Parental involvement and adolescents’ diabetes management: The mediating role of self-efficacy and externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(3):329–339. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Berg CA, Wiebe DJ, Beveridge RM, Palmer DL, Korbel CD, Upchurch R, et al. Mother-child appraised involvement in coping with diabetes stressors and emotional adjustment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(8):995–1005. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell CD, Newacheck PW, Fine A, Strickland BB, Antonelli RC, Wilhelm CL, et al. Optimizing health and health care systems for children with special health care needs using the life course perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2014;18(2):467–477. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Botello-Harbaum M, Nansel T, Haynie DL, Iannotti RJ, Simons-Morton B. Responsive parenting is associated with improved type 1 diabetes-related quality of life. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2008;34(5):675–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00855.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brace MJ, Smith MS, McCauley E, Sherry DD. Family reinforcement of illness behavior: A comparison of adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome, juvenile arthritis, and healthy controls. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2000;21(5):332–339. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200010000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Butler JM, Skinner M, Gelfand D, Berg CA, Wiebe DJ. Maternal parenting style and adjustment in adolescents with type I diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(10):1227–1237. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Butner J, Berg CA, Osborn P, Butler JM, Godri C, Fortenberry KT, et al. Parent-adolescent discrepancies in adolescents’ competence and the balance of adolescent autonomy and adolescent and parent well-being in the context of type 1 diabetes. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(3):835–849. doi: 10.1037/a0015363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey JS. Parenting a child with chronic illness: A metasynthesis. Pediatric Nursing. 2006;32(1):51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- *.Cohen M, Mansoor D, Gagin R, Lorber A. Perceived parenting style, self-esteem and psychological distress in adolescents with heart disease. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2008;13(4):381–388. doi: 10.1080/13548500701842925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L. Optimizing family interventions. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) In: McHale S, McHale P, Amato P, Booth A, editors. Emerging methods in family research. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff AJ. Identifying children with special healthcare needs in the National Health Interview Survey: A new resource for policy analysis. Health Services Research. 2004;39(1):53–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Davis CL, Delamater AM, Shaw KH, La Greca AM, Eidson MS, Perez-Rodriguez JE, et al. Brief report: Parenting styles, regimen adherence, and glycemic control in 4- to 10-year-old children with diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26(2):123–129. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Duke DC, Geffken GR, Lewin AB, Williams LB, Storch EA, Silverstein JH. Glycemic control in youth with type 1 diabetes: Family predictors and mediators. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(7):719–727. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis F, Duhamel F, Gendron S. Transitioning care of an adolescent with cystic fibrosis: Development of systemic hypothesis between parents, adolescents, and health care professionals. Journal of Family Nursing. 2011;17:291–311. doi: 10.1177/1074840711414907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–563. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Eckshtain D, Ellis D, Kolmodin K, Naar-King S. The effects of parental depression and parenting practices on depressive symptoms and metabolic control in urban youth with insulin dependent diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35(4):426–435. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ellis DA, Podolski C, Frey M, Naar-King S, Wang B, Moltz K. The role of parental monitoring in adolescent health outcomes: Impact on regimen adherence in youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(8):907–917. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Faulkner MS, Chang L. Family influence on self-care, quality of life, and metabolic control in school-age children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2007;22(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Geffken GR, Lehmkuhl H, Walker KN, Storch EA, Heidgerken AD, Lewin, et al. Family functioning processes and diabetic ketoacidosis in youths with type I diabetes. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2008;53(2):231–237. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.53.2.231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Hanestad BR, Søvik O. Health-related quality of life and metabolic control in adolescents with diabetes: The role of parental care, control, and involvement. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2005;20(5):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Greene MS, Mandleco B, Roper SO, Marshall ES, Dyches T. Metabolic control, self-care behaviors, and parenting in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A correlational study. Diabetes Educator. 2010;36(2):326–336. doi: 10.1177/0145721710361270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havill N, Leeman J, Shaw-Kokot J, Knafl K, Crandell J, Sandelowski M. Managing large-volume literature searches in research synthesis studies. Nursing Outlook. 2014;62(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Helgeson VS, Siminerio L, Escobar O, Becker D. Predictors of metabolic control among adolescents with diabetes: A 4-year longitudinal study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(3):254–270. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Herzer M, Umfress K, Aljadeff G, Ghai K, Zakowski SG. Interactions with parents and friends among chronically ill children: Examining social networks. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30(6):499–508. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c21c82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [updated March 2011] Available from http://handbook.cochrane.org. [Google Scholar]

- *.Holmbeck GN, Johnson SZ, Wills KE, McKernon W, Rose B, Erklin S, et al. Observed and perceived parental overprotection in relation to psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with a physical disability: The mediational role of behavioral autonomy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):96–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.70.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Horton D, Berg CA, Butner J, Wiebe DJ. The role of parental monitoring in metabolic control: Effect on adherence and externalizing behaviors during adolescence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(9):1008–1018. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hullmann SE, Wolfe-Christensen C, Meyer WH, McNall-Knapp RY, Mullins LL. The relationship between parental overprotection and health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer: The mediating role of perceived child vulnerability. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(9):1373–1380. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley K, Huscroft-D’Angelo J, Trout A, Griffith A, Epstein M. Assessing parenting skills and attitudes: A review of the psychometrics of parenting measures. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23:812–823. doi: 10.1007/s1826-013-9733-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Immelt S. Psychological adjustment in young children with chronic medical conditions. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2006;21(5):362–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Jaser SS, Grey M. A pilot study of observed parenting and adjustment in adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their mothers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35(7):738–747. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Jaser SS, Whittemore R, Ambrosino JM, Lindemann E, Grey M. Mediators of depressive symptoms in children with type 1 diabetes and their mothers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(5):509–519. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G, Kent G, Leather J. Strengthening the parent-child relationship: A review of family interventions and their use in medical settings. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2005;31(1):25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kim DH, Yoo IY. Factors associated with depression and resilience in asthmatic children. Journal of Asthma. 2007;44(6):423–427. doi: 10.1080/02770900701421823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen A, Raina P, Reineking S, Dix D, Pritchard S, O’Donnell M. Developing a literature base to understand the caregiving experience of parents of children with cancer: A systematic review of factors related to parental health and well-being. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2007;15(7):807–818. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl KA, Havill NL, Leeman J, Fleming L, Crandell JL, Sandelowski M. The nature of family engagement in interventions for children with chronic conditions. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2016;39:690–723. doi: 10.1177/0193945916664700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Leeman J, Havill N, Crandell J, Sandelowski M. Delimiting family in syntheses of research on childhood chronic conditions and family life. Family Process. 2015;54(1):173–184. doi: 10.1111/famp.12101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman J, Crandell J, Lee A, Bai J, Sandelowski M, Knafl K. Family functioning and the well-being of children with chronic conditions: A meta-analysis. Research in Nursing & Health. 2016;39:229–243. doi: 10.1002/nur.21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman J, Sandelowski M, Havill N, Knafl K. Parent-to-Child Transition in Managing Cystic Fibrosis: A Research Synthesis. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2015;7:167–183. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lewin AB, Heidgerken AD, Geffken GR, Williams LB, Storch EA, Gelfand KM, et al. The relation between family factors and metabolic control: The role of diabetes adherence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(2):174–183. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Liakopoulou M, Alifieraki T, Katideniou A, Peppa M, Maniati M, Tzikas D, et al. Maternal expressed emotion and metabolic control of children and adolescents with diabetes mellitus. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2001;70(2):78–85. doi: 10.1159/000056230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lim J, Wood BL, Miller BD. Maternal depression and parenting in relation to child internalizing symptoms and asthma disease activity. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(2):264–273. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lloyd SM, Cantell M, Pacaud D, Crawford S, Dewey D. Brief report: Hope, perceived maternal empathy, medical regimen adherence, and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(9):1025–1029. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Luyckx K, Goossens E, Rassart J, Apers S, Vanhalst J, Moons P. Parental support, internalizing symptoms, perceived health status, and quality of life in adolescents with congenital heart disease: Influences and reciprocal effects. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;37(1):145–155. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9474-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Luyckx K, Missotten L, Goossens E, Moons P for the i-DETACH Investigators. Individual and contextual determinants of quality of life in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51(2):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meakins L, Ray L, Hegadoren K, Rogers LG, Rempel GR. Parental vigilance in caring for their children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatric Nursing. 2015;41(1):31–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mlynarczyk SM. Adolescents’ perspectives of parental practices influence diabetic adherence and quality of life. Pediatric Nursing. 2013;39(4):181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Monaghan M, Horn IB, Alvarez V, Cogen FR, Streisand R. Authoritative parenting, parenting stress, and self-care in pre-adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2012;19(3):255–261. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9284-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Moon JR, Huh J, Kang IS, Park SW, Jun T, Lee HJ. Factors influencing depression in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Heart & Lung - the Journal of Acute and Critical Care. 2009;38(5):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney-Doyle K, Deatrick J. Parenting in the face ot childhood life-threatening conditions: The ordinary in the context of the extraordinary. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2016;14:187–198. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Nagano J, Kakuta C, Motomura C, Odajima H, Sudo N, Nishima S, et al. The parenting attitudes and the stress of mothers predict the asthmatic severity of their children: A prospective study. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. 2010;4(1):12–12. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Penner LA, Cline RJ, Albrecht TL, Harper FW, Peterson AM, Taub JM, et al. Parents’ empathic responses and pain and distress in pediatric patients. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2008;30(2):102–113. doi: 10.1080/01973530802208824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Peterson CC, Palermo TM. Parental reinforcement of recurrent pain: The moderating impact of child depression and anxiety on functional disability. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29(5):331–341. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M. Do the parent-child relationship and parenting behaviors differ between families with a child with and without chronic illness? A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2013;38(7):708–721. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina P, O’Donnell M, Schwellnus H, Rosenbaum P, King G, Brehaut J, … Wood E. Caregivng process and caregiver burden: Conceptual models to guide research and practice. BMC Pediatrics. 4:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LD. Parenting and childhood chronicity: Making visible the invisible work. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2002;17(6):424–438. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.127172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Reid A, Balkhi A, St Amant J, McNamara J, Silverstein J, Navia L, et al. Relations between quality of life, family factors, adherence, and glycemic control in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Childrens Health Care. 2013;42(4):295–310. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2013.842455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rodenburg R, Meijer AM, Dekovic M, Aldenkamp AP. Family predictors of psychopathology in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47(3):601–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rodenburg R, Meijer A, Scherphof C, Carpay J, Augustijn P, Aldenkamp AA, et al. Parenting and restrictions in childhood epilepsy. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2013;27(3):497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Crandell J, Leeman J. Synthesizing qualitative and quantitative research findings. In: Beck CT, editor. Routledge International Handbook of Qualitative Nursing Research. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. pp. 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: A systematic review and annotated bibliography. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;36(3):666–676. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Seiffge-Krenke I, Laursen B, Dickson DJ, Hartl AC. Declining metabolic control and decreasing parental support among families with adolescents with diabetes: The risk of restrictiveness. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2013;38(5):518–530. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sherifali D, Ciliska D, O’Mara L. Parenting children with diabetes: Exploring parenting styles on children living with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educator. 2009;35(3):476–483. doi: 10.1177/0145721709333268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Shorer M, David R, Schoenberg-Taz M, Levavi-Lavi I, Phillip M, Meyerovitch J. Role of parenting style in achieving metabolic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1735–1737. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E, Johnson S, Snyder T. Six dimensions of parenting: A motivational model. Parenting. 2005;5(2):175–235. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0502_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. for the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Jama. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Tayel KY, Attia MS, Mounier GM, Naguib KM. Anxiety among school age children suffering from asthma. The Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association. 2000;75(1–2):179–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP for the STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(8):573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ward C, Massie J, Glazner J, Sheehan J, Canterford L, Armstrong D, et al. Problem behaviours and parenting in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2009;94(5):341–347. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.150789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Weissberg-Benchell J, Nansel T, Holmbeck G, Chen R, Anderson B, Wysocki T, et al. for the Steering Committee of the Family Management of Diabetes Study. Generic and diabetes-specific parent-child behaviors and quality of life among youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(9):977–988. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wiebe DJ, Berg CA, Korbel C, Palmer DL, Beveridge RM, Upchurch R, et al. Children’s appraisals of maternal involvement in coping with diabetes: Enhancing our understanding of adherence, metabolic control, and quality of life across adolescence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30(2):167–178. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Worrall-Davies A, Owens D, Holland P, Haigh D. The effect of parental expressed emotion on glycaemic control in children with type 1 diabetes: Parental expressed emotion and glycaemic control in children. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;52(2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wu YP, Hilliard ME, Rausch J, Dolan LM, Hood KK. Family involvement with the diabetes regimen in young people: The role of adolescent depressive symptoms. Diabetic Medicine. 2013;30(5):596–602. doi: 10.1111/dme.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wu Y, Rausch J, Rohan J, Hood K, Pendley J, Delamater A, et al. Autonomy support and responsibility-sharing predict blood glucose monitoring frequency among youth with diabetes. Health Psychology. 2014;33(10):1224–1231. doi: 10.1037/hea0000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Yadav A, Yadav TP. A study of school adjustment, self-concept, self-esteem, general wellbeing and parent child relationship in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;80(3):199–206. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0804-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Yalçýn SS, Durmuşoğlu-Şendoğdu M, Gümrük F, ünal S, Kargi E, Tuğrul B. Evaluation of the children with β-thalassemia in terms of their self-concept, behavioral, and parental attitudes. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2007;29(8):523–528. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3180f61b56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Profile of Included Reports (N=52)

Supplemental Figure 1: Study Team Disciplines and Country

Supplemental Figure 2: Studies used for each child wellbeing/parent dimension relationship.