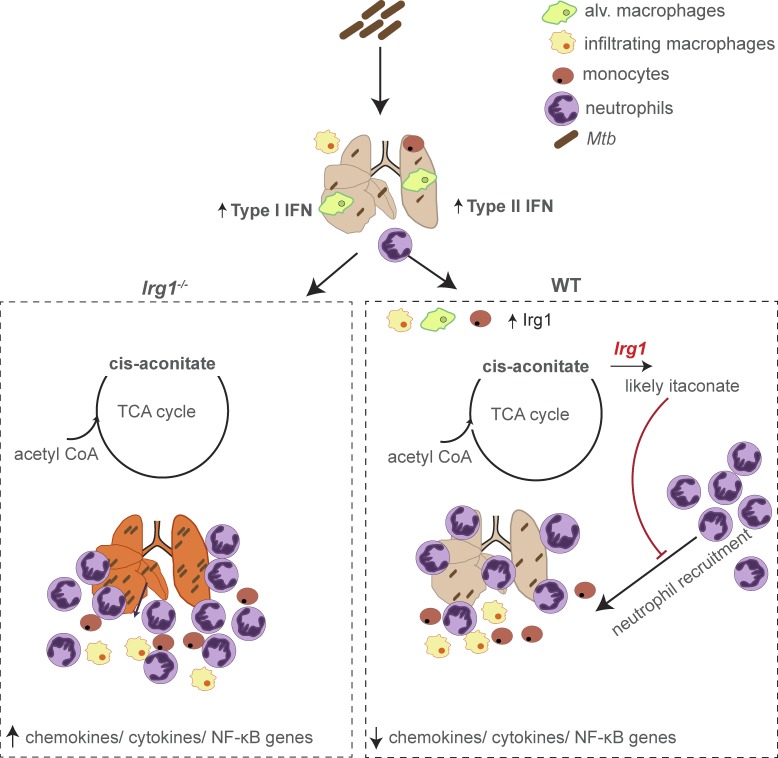

Nair et al. define a key role for Irg1 in minimizing the pathological immune response associated with Mtb infection. Using Irg1−/− and Irg1fl/fl conditional mice, detailed immune cell analysis, and transcriptional profiling, their data supports a model where Irg1 expression in myeloid cell subsets tempers inflammation and controls the recruitment and infection of neutrophils during Mtb infection.

Abstract

Immune-Responsive Gene 1 (Irg1) is a mitochondrial enzyme that produces itaconate under inflammatory conditions, principally in cells of myeloid lineage. Cell culture studies suggest that itaconate regulates inflammation through its inhibitory effects on cytokine and reactive oxygen species production. To evaluate the functions of Irg1 in vivo, we challenged wild-type (WT) and Irg1−/− mice with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and monitored disease progression. Irg1−/−, but not WT, mice succumbed rapidly to Mtb, and mortality was associated with increased infection, inflammation, and pathology. Infection of LysM-Cre Irg1fl/fl, Mrp8-Cre Irg1fl/fl, and CD11c-Cre Irg1fl/fl conditional knockout mice along with neutrophil depletion experiments revealed a role for Irg1 in LysM+ myeloid cells in preventing neutrophil-mediated immunopathology and disease. RNA sequencing analyses suggest that Irg1 and its production of itaconate temper Mtb-induced inflammatory responses in myeloid cells at the transcriptional level. Thus, an Irg1 regulatory axis modulates inflammation to curtail Mtb-induced lung disease.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the etiologic agent of tuberculosis (TB), causes up to 8.8 million new clinical infections and 1.4 million deaths annually (World Health Organization, 2016). In the mouse model of TB, the acute phase of infection is marked by exponential growth of the bacteria in the lungs. In its persistence phase, Mtb undergoes a metabolic shift, triggered by changes in nutrient availability as substrates for glycolysis become limited (Bloch and Segal, 1956). The bacterial glyoxylate shunt pathway is an alternative anaplerotic pathway that facilitates the use of fatty acids as a carbon source for biosynthetic pathways and generation of ATP. Mtb strains encode at least one and sometimes two isocitrate lyases (ICL1 and ICL2) that function within the glyoxylate shunt (Höner Zu Bentrup et al., 1999; Dunn et al., 2009). Mutation of the ICL genes has provided evidence for a role of the glyoxylate shunt in Mtb pathogenesis (McKinney et al., 2000; Muñoz-Elías and McKinney, 2005).

The host Immune-Responsive Gene 1 (Irg1; also called Acod1) is a mitochondrial enzyme induced under inflammatory conditions that produces the metabolite itaconate by decarboxylating cis-aconitate, a TCA cycle intermediate (Michelucci et al., 2013). Because itaconate production in myeloid cells reportedly inhibits bacterial ICLs, it has gained interest as an endogenous antibacterial effector molecule (McFadden and Purohit, 1977). This role was supported by a study showing that nonphysiologically relevant (25 mM) concentrations of itaconate had bacteriostatic effects on Mtb growth during liquid culture under conditions requiring the glyoxylate shunt pathway (Michelucci et al., 2013).

Beyond its possible antibacterial functions, itaconate also links immune cell metabolism and inflammatory responses. Irg1 is highly expressed in macrophages in response to proinflammatory stimuli that induce type I and type II IFN signaling (Degrandi et al., 2009). In bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs), itaconate suppressed the production of mitochondrial ROS as well as proinflammatory cytokines, including IL1-β, IL6, and IL12p70 (Lampropoulou et al., 2016). This capacity to modulate inflammation could be of particular importance during Mtb infection because excessive immune responses can prevent bacterial clearance and cause pathology (Nandi and Behar, 2011; Kimmey et al., 2015).

We addressed the function of Irg1 in regulating immune responses and Mtb pathogenesis using Irg1−/− and Irg1fl/fl conditional gene-deleted mice. A complete absence of Irg1 during Mtb infection resulted in severe pulmonary disease and ultimately death, with greater numbers of infected myeloid cells and higher production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Irg1 expression in myeloid cell subsets was necessary to control neutrophil recruitment, Mtb infection, and immune-mediated tissue injury. Our studies define a key role for Irg1 in regulating immune cell metabolism in subsets of myeloid cells, which minimizes the pathological immune response that contributes to pulmonary disease caused by Mtb.

Results and discussion

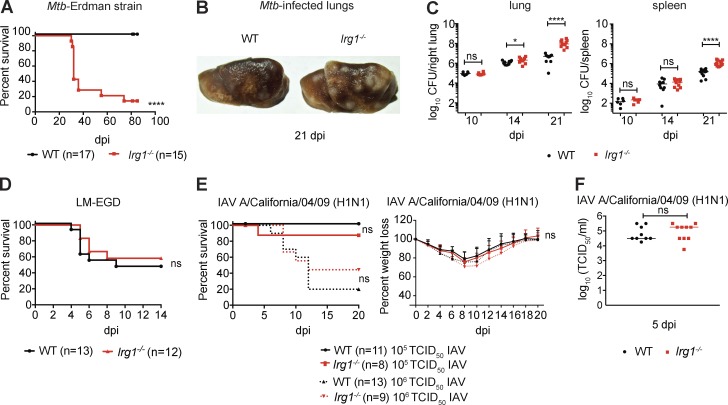

To determine the role of Irg1 during Mtb infection, Irg1−/− C57BL/6N mice were monitored for clinical and bacterial outcomes after aerosol inoculation with the Mtb Erdman strain. Whereas all WT mice survived past 80 d postinfection (dpi), ∼75% of Irg1−/− mice succumbed to Mtb within 30 d, a phenotype similar to animals lacking IFN-γ signaling (Fig. 1 A; Cooper et al., 1993; Flynn et al., 1993; Nandi and Behar, 2011). At 21 dpi, the lungs of Irg1−/− mice infected with Mtb had larger numbers and sizes of macroscopic lesions compared with infected WT mice (Fig. 1 B). Although bacterial levels were similar in the lungs and spleens of WT and Irg1−/− mice at 10 dpi, by 14 and 21 dpi, the Mtb burden was ∼3- and 25-fold higher, respectively, in the lungs of Irg1−/− compared with WT mice (P < 0.01; Fig. 1 C, left). At 21 dpi, Mtb burden also was approximately eightfold higher in the spleens of Irg1−/− compared with WT mice (Fig. 1 C, right). We also tested the effects of Irg1 on Listeria monocytogenes (strain EGD), an intracellular bacterium administered by intravenous injection, and Influenza A virus (IAV strain A/California/04/2009 H1N1), a respiratory pathogen inoculated by intranasal route (Fig. 1, D–F). Loss of Irg1 expression in mice did not result in altered susceptibility to Listeria monocytogenes (Fig. 1 D) or IAV infection (Fig. 1, E and F).

Figure 1.

Irg1 is essential for host resistance to Mtb. (A–C) WT and Irg1−/− mice were infected with aerosolized Mtb. (A) Survival analysis. (B) Gross pathology of lungs at day 21. (C) Mtb burden (GFP+ Erdman strain) was measured at days 10 (n = 6), 14 (n = 10), and 21 (n = 11–12) after infection. (D) WT and Irg1−/− mice were inoculated intravenously with Listeria monocytogenes (LM) and monitored for survival (n = 12–13). (E and F) WT and Irg1−/− mice were infected intranasally with IAV and monitored for survival and weight loss (E), and lung viral burden at 5 dpi (F; n = 9–10). (A–F) All data are from at least two independent experiments. Statistical differences are indicated. (C, E [right], and F) Mann-Whitney test: *, P < 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant. (A, D, and E [left]) Log-rank test. ns, not significant. Error bars designate SEM.

The strain of Mtb used in this study, Erdman, encodes two ICL genes, ICL1 and ICL2. In vivo, Δicl1 Mtb strains replicate normally during the acute phase, but are attenuated during the chronic, persistent phase of infection, whereas Δicl2 Mtb strains show no defects in infection (McKinney et al., 2000; Muñoz-Elías and McKinney, 2005). Δicl1 Δicl2 strains are avirulent in vivo, possibly because ICL has additional methylisocitrate lyase activity that prevents toxic accumulation of propionyl-CoA (Muñoz-Elías and McKinney, 2005; Muñoz-Elías et al., 2006; Savvi et al., 2008). To test the impact of Irg1 on the bacterial glyoxylate shunt in vivo, we infected WT and Irg1−/− mice with WT and isogenic Δicl1 Mtb strains. As anticipated, 100% of WT mice infected with WT or Δicl1 Mtb survived infection over an 80-d time course (Fig. S1 A). In contrast, all Irg1−/− mice infected with Δicl1 Mtb succumbed to infection without differences in mean time to death (Fig. S1 A) or relative weight loss (Fig. S1 B) compared with the isogenic WT Mtb strain. Moreover, Δicl1 bacterial titers in the lung and the spleen of Irg1−/− mice were ∼83- and ∼12-fold higher than in WT mice, respectively (Fig. S1 C). Because Δicl1 Mtb lacks a fully functional glyoxylate shunt pathway, yet is still virulent in Irg1−/− mice, Irg1 likely restricts Mtb infection in vivo independently of its activity on ICL1.

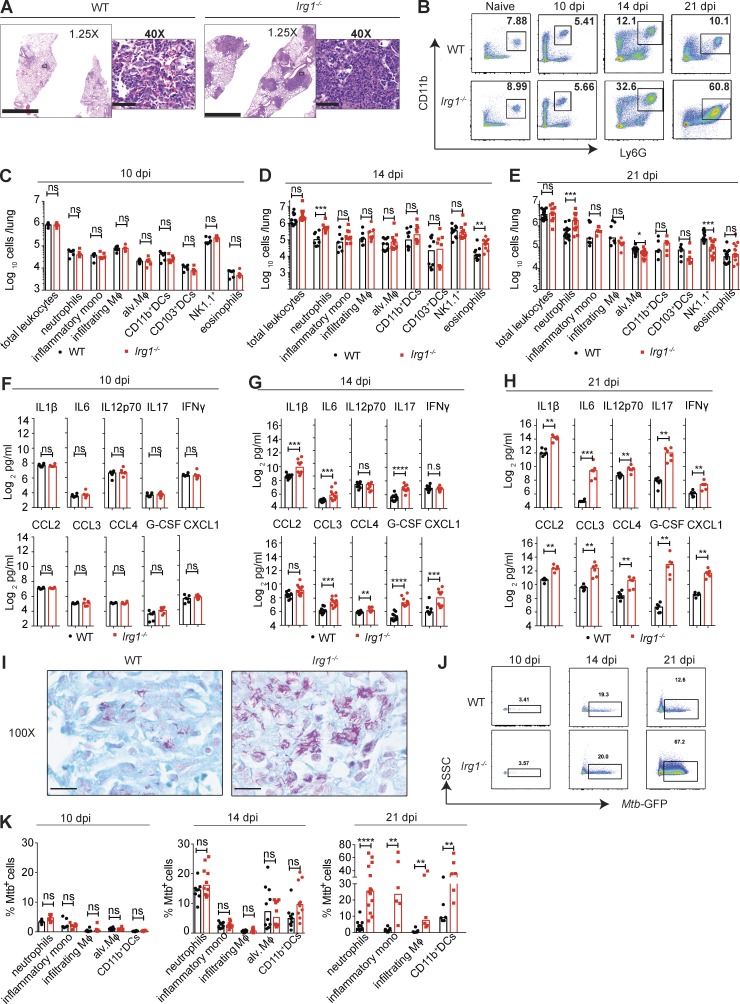

We next evaluated whether Irg1-dependent regulation of inflammatory responses (Lampropoulou et al., 2016) contributed to Mtb pathogenesis. We infected WT and Irg1−/− mice with an Mtb strain expressing GFP (Mtb-GFP) that has the same virulence properties as WT Mtb (Fig. S1 F). Histological analysis at 21 dpi showed that lung lesions from Mtb-GFP–infected Irg1−/− mice were larger in size with denser cellular infiltrates (Fig. 2 A). To define the composition of these infiltrates, we profiled immune cells in Mtb-GFP–infected lungs by flow cytometry (gating strategy defined in Fig. S2 A). At 10 dpi, no differences in the number of neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes, infiltrating macrophages, alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer (NK) and NKT cells, or eosinophils were detected in the lungs of WT and Irg1−/− mice (Fig. 2, B and C). However, by day 14, infected lungs from Irg1−/− mice had greater numbers of neutrophils (approximately fourfold) and eosinophils (threefold) than WT mice, and this difference remained at day 21 for neutrophils (Fig. 2, B, D, and E). At 21 dpi, lungs from Irg1−/− mice also had lower numbers of alveolar macrophages (1.3-fold) and NK1.1+ cells (approximately threefold). Analysis of other innate immune cell populations in the lungs at 14 and 21 dpi revealed no significant differences in numbers of inflammatory monocytes, infiltrating macrophages, and infiltrating and resident dendritic cells between Mtb-GFP–infected WT and Irg1−/− mice. In addition, no differences in the numbers of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and B cells were found between WT and Irg1−/− mice at 21 dpi (Fig. S2 B).

Figure 2.

Irg1 modulates inflammatory responses in the lung after Mtb infection. Mice were infected with aerosolized Mtb-GFP. (A) Histopathology was visualized by H&E staining of lungs at 21 dpi. Images are representative of two independent experiments. Bars: 2.5 mm (1.25×); 50 µm (40×). (B) Flow cytometry plots for neutrophils as a percentage of total CD45+ cells in lungs before Mtb infection and at 10, 14, and 21 dpi. Data are representative of results from n = 6–15 mice depending on the time point. (C–E) Number of innate immune cell populations in lungs at 10 dpi (C; n = 6), 14 dpi (D; n = 10), and 21 dpi (E; n = 6–15). (F–H) Cytokine and chemokine levels in the Mtb-infected lungs at 10 dpi (F; n = 6), 14 dpi (G; n = 10), and 21 dpi (H; n = 6). (I) Acid-fast bacilli in Mtb-infected lungs at 21 dpi. Images are representative of two independent experiments. Bars, 10 µm. (J) Flow cytometry plots for Mtb-GFP+ neutrophils in lungs at 10, 14, and 21 dpi. SSC, side scatter. (K) The percentage of Mtb-GFP-positive cells in indicated cell types at 10 (n = 6), 14 (n = 8–10), and 21 (n = 6–15) dpi. All data are pooled from at least two independent experiments. (C–H and K) Bars indicate median values. Statistical differences were determined by Mann-Whitney test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant). Mφ, macrophages. See also Figs. S1 and S2.

We measured the effect of Irg1 on the accumulation of inflammatory mediators in the lung during Mtb-GFP infection. Equivalent levels of chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines in lung homogenates of WT and Irg1−/− mice were detected at 10 dpi (Fig. 2 F and Fig. S2 C). By 14 dpi, higher levels of several proinflammatory cytokines (IL1-β, IL6, IL17, and G-CSF) and chemokines (CXCL1, CCL3, and CCL4) were detected in the lungs of Irg1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 2 G), although TNF-α levels remained unchanged (Fig. S2 C). By 21 dpi, all proinflammatory cytokines (IL1-β, IL6, IL12p70, IL17, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and G-CSF) and chemokines (CCL2, CXCL1, CCL3, and CCL4) measured were higher in the lungs of Irg1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 2 H and Fig S2 C).

Because Irg1−/− mice infected with WT or Δicl1 Mtb succumbed to infection at equivalent rates (Fig. S1 A), we investigated if the inflammatory responses in these mice was similar. Δicl1 Mtb–infected Irg1−/− mice also showed increased accumulation of neutrophils in their lungs at 21 dpi (Fig. S1 D). Correspondingly, proinflammatory cytokines (IL1-β, IL6, IL12p70, IL17, G-CSF, and IFN-γ) and chemokines (CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, and CXCL1) were higher in Δicl1 Mtb–infected Irg1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. S1 E). The similar levels of increased neutrophil accumulation in response to both WT and Δicl1 Mtb in Irg1−/− mice supports the hypothesis that the defect in controlling Mtb infection in these mice is independent of ICL1 activity and a fully functional glyoxylate shunt pathway.

We evaluated whether accumulating myeloid cells in the lung were infected with Mtb. At 21 dpi, lung lesions were the preferred sites for Mtb infection, with greater numbers of acid-fast bacilli present in Irg1−/− mice (Fig. 2 I). To analyze infection in each myeloid cell type, we monitored the presence of Mtb-GFP by flow cytometry. At 10 and 14 dpi, each myeloid cell type in WT and Irg1−/− lungs was infected at similar frequencies (Fig. 2, J and K). By 21 dpi, lungs from Irg1−/− mice had higher percentages of infected neutrophils (eightfold), inflammatory monocytes (19-fold), infiltrating macrophages (19-fold), and CD11b+ dendritic cells (approximately threefold) compared with WT mice (Fig. 2, J and K). Collectively, this data suggests that Irg1 regulates inflammatory responses, which controls the recruitment of multiple types of myeloid cells, many of which become targets for subsequent rounds of Mtb infection. Irg1 did not have a direct effect on Mtb infectivity in cell culture, as no differences in bacterial titers were detected in WT and Irg1−/− BMDMs (Fig. S1 G).

In macrophage-lineage cells from zebrafish, Irg1 was suggested to promote antibacterial effects by regulating the use of fatty acids, which are substrates for mitochondrial ROS (mROS) production (Hall et al., 2013). To determine whether Irg1−/− mice had less mROS expression in key myeloid cells as an explanation for the failure to control Mtb infection, we evaluated mROS levels in neutrophils in vivo at 21 dpi. However, neutrophils from Mtb-infected Irg1−/− mice had a higher expression of mROS (Fig. S2 D). Exogenous itaconate treatment of activated BMDMs in vitro also was shown to suppress mROS and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression (Lampropoulou et al., 2016). Consistent with these findings, Irg1−/− mice had a higher frequency and number of iNOS-producing neutrophils (Fig. S2 D). Thus, the higher production of mROS and iNOS in Irg1−/− neutrophils suggests these cells are in a hyperinflamed state, rather than being defective in these antimicrobial mediators.

To begin to define which cell types required Irg1 expression to control Mtb infection, we established reciprocal bone marrow chimeric mice by replacing the WT and Irg1−/− recipient marrow with the donor marrow cells from Irg1−/− and WT mice or using WT marrow into donor WT mice as controls (Fig. S3 A). Whereas WT → WT and WT → Irg1−/− mice survived Mtb infection for over 80 dpi, Irg1−/−→ WT mice succumbed to Mtb infection by 32 dpi, demonstrating that the protective response was derived from Irg1-sufficient radiosensitive cells (Fig. S3 B). Mtb titers in the lungs and the spleen of Irg1−/− → WT mice were higher than WT → WT mice at 21 dpi (∼10-fold and threefold, respectively; Fig. S3 C). At 21 dpi Irg1−/−→ WT mice had greater accumulation of neutrophils in their lungs than WT → WT mice (Fig. S3 D), whereas no differences in recruitment of other innate immune populations were seen.

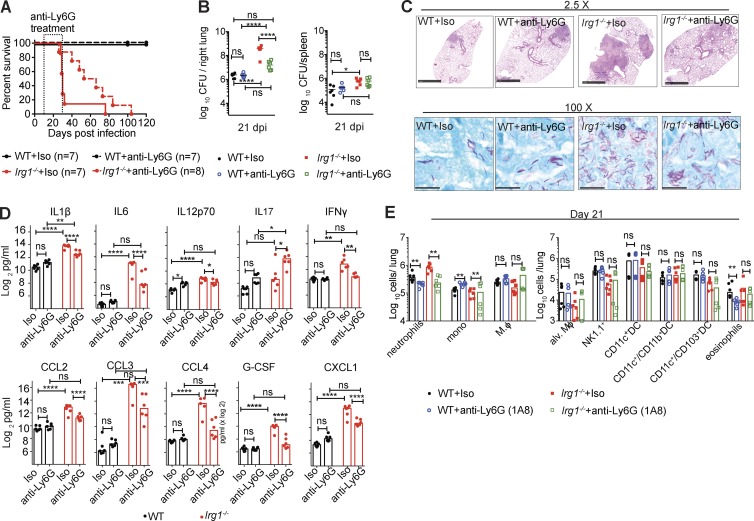

Excessive neutrophil recruitment is associated with progression of Mtb disease (Nandi and Behar, 2011; Kimmey et al., 2015). To test whether the susceptibility of the Irg1−/− mice to Mtb infection was a result of the increased accumulation of neutrophils in the lung, we administered a neutrophil-depleting (anti-Ly6G) or isotype control antibody to WT and Irg1−/− mice, beginning on day 10 with repeated injections every other day through day 34. Treatment of Irg1−/− mice from day 10 to 34 with anti-Ly6G prolonged survival during Mtb infection (Fig. 3 A). Depletion of neutrophils starting at day 10 also resulted in reduced Mtb burden in the lungs at 21 dpi (19-fold) compared with isotype control–treated Irg1−/− mice. However, the levels of Mtb in neutrophil-depleted Irg1−/− mice still were higher (ninefold) than in antibody-treated WT mice (Fig. 3 B), indicating that recruitment and infection of neutrophils partially contributed to the higher bacterial burden in Mtb-infected Irg1−/− mice. Correspondingly, diminished numbers of bacilli were present in lung sections of Irg1−/− mice treated with anti-Ly6G mAb compared with the isotype control (Fig. 3 C). Lung lesions from Mtb-infected, anti-Ly6G mAb-treated Irg1−/− mice were smaller than isotype-treated counterparts (Fig. 3 C). Cytokine and chemokine levels in the lung also were decreased in neutrophil-depleted Irg1−/− mice at 21 dpi (Fig. 3 D). At 21 dpi, as expected, anti-Ly6G mAb treatment of Irg1−/− mice had reduced the number of neutrophils compared with isotype control–treated animals (Fig. 3 E and Fig. S2 E). With the exception of a small decrease in numbers of inflammatory monocytes, the recruitment of which could be altered by decreases in lung cytokine and chemokine expression as a result of neutrophil depletion, all other innate immune cell subsets were unaffected by neutrophil depletion (Fig. 3 E). Once the neutrophil depletion treatment was stopped and neutrophils were allowed to accumulate in the lung, disease ensued and all Irg1−/− mice succumbed to infection. Thus, depletion of neutrophils mitigates the bacterial and proinflammatory pathological phenotypes observed at day 21 after infection in Irg1−/− mice, and a dysfunctional neutrophil response contributes to the susceptibility of these mice to Mtb infection.

Figure 3.

Depletion of neutrophils enhances survival of Mtb-infected Irg1−/− mice. WT and Irg1−/− mice were infected with aerosolized Mtb and treated with anti-Ly6G or isotype control antibodies as described in the Materials and methods. (A) Survival analysis (n = 7–8). (B) Mtb burden in the lung at 21 dpi (n = 7–8). Lines indicate median values. (C) Lung histopathology and acid-fast bacilli at 21 dpi were visualized with H&E (top) and acid-fast (bottom) stains. Images are representative of two independent experiments. Bars: 1 mm (top); 100 µm (bottom). (D) Cytokine levels at 21 dpi (n = 6). (E) Innate immune cell populations in the lung at 21 dpi (n = 6). All data are pooled from two independent experiments. Statistical differences were determined via one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction (B and D) and Mann-Whitney test (E; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant). See also Fig. S2.

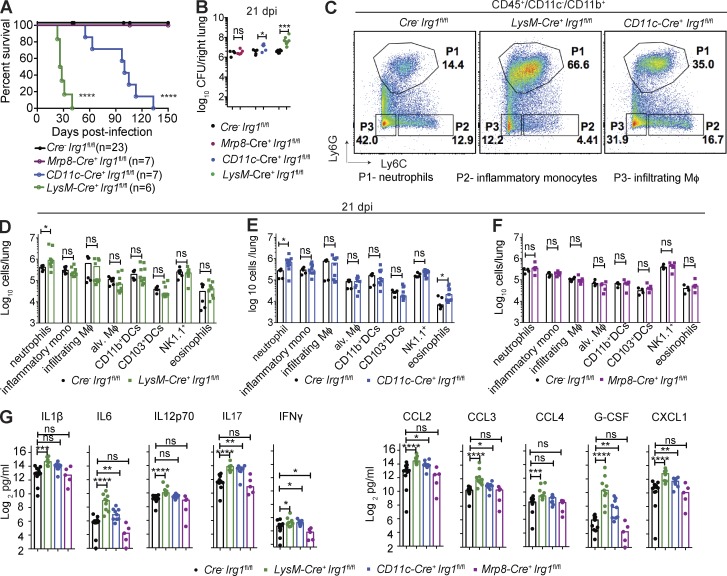

We next sought to identify the cell types that expressed Irg1 and modulated neutrophil accumulation and Mtb disease pathogenesis. Because Irg1 is expressed principally in cells of myeloid lineage (Degrandi et al., 2009; Hall et al., 2013; Michelucci et al., 2013; Lampropoulou et al., 2016), we tested its role in Mtb infection in different myeloid cell subsets using mice lacking Irg1 expression in neutrophils (Mrp8-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl), alveolar macrophages and some dendritic cells (CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl), or monocytes/macrophages, alveolar macrophages, neutrophils, and some dendritic cells (LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl; Fig. S3, E–G). Although all Cre−Irg1fl/fl and Mrp8-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice survived past 150 dpi, all LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice succumbed to Mtb within 40 dpi, a phenotype similar to Irg1−/− mice (Fig. 4 A). In comparison, all CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice succumbed to Mtb by 135 dpi. Consistent with these survival results, Mtb levels in the lungs of Mrp8-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice were similar to littermate Cre− Irg1fl/fl controls, whereas CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl and LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice both had greater pulmonary bacterial burden at 21 dpi (∼3.5-fold and 14-fold, respectively; Fig. 4 B). At 21 dpi, both LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl and CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice had greater numbers of neutrophils in their lungs than Cre− Irg1fl/fl mice (Fig. 4, C–E), but Mrp8-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice did not (Fig. 4 F). Loss of Irg1 expression in myeloid cells (LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice) resulted in higher levels of cytokines and chemokines in the lungs at 21 dpi (Fig. 4 G). Loss of Irg1 expression in alveolar macrophages and some dendritic cell subsets from CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice also resulted in greater amounts of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. In comparison, deletion of Irg1 in neutrophils had little effect on cytokine responses. These data show that Irg1 expression in CD11c+ and LysM+ cell subsets regulates neutrophil recruitment and inflammation. Although neutrophils mediate Mtb-induced immunopathology in Irg1−/− mice, their cell-intrinsic expression of Irg1 is dispensable for this process.

Figure 4.

Loss of Irg1 in myeloid cell subsets confers susceptibility to Mtb. Mice were infected with aerosolized Mtb. (A) Survival analysis of Cre− Irg1fl/fl, Mrp8-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl, CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl, and LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice (n = 6–23) after Mtb infection. (B) Mtb burden in lungs of Cre− Irg1fl/fl (n = 15), Mrp8-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl (n = 5), CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl (n = 9), and LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl (n = 9) mice at 21 dpi. Lines indicate median values. (C) Flow cytometry plots of lung neutrophils (P1), inflammatory monocytes (P2), and infiltrating macrophages (P3) as a percentage of the total CD45+ CD11c−CD11b+ population in Cre− Irg1fl/fl, LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl, and CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl mice at 21 dpi. (D–F) Quantitation of myeloid cells in lungs of Cre− Irg1fl/fl (n = 6) and LysM-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl (D; n = 9), Cre− Irg1fl/fl (n = 5) and CD11c-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl (E; n = 9), and Cre− Irg1fl/fl (n = 4) and Mrp8-Cre+ Irg1fl/fl (F; n = 5) mice at 21 dpi. Mφ, macrophages. (G) Cytokine levels at 21 dpi (n = 5–14). All data are pooled from at least two independent experiments. Bars indicate median values. Statistical differences were determined via log-rank test with a Bonferroni post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons (A; ****, P < 0.0001) and Mann-Whitney test (B and D–G; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not-significant). See also Fig. S3.

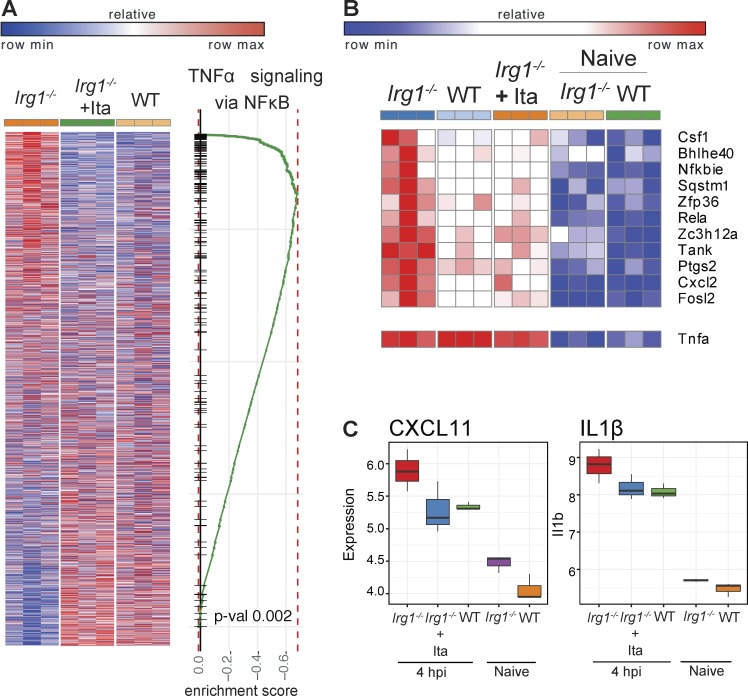

To gain insight into why a lack of Irg1 expression in myeloid cells resulted in excessive accumulation of neutrophils in Irg1−/− mice during Mtb infection, we compared the expression profiles of Mtb-infected WT and Irg1−/− BMDMs. Within just 4 h of Mtb infection, the transcriptional signature in Irg1−/− BMDMs differed markedly from WT BMDMs. Many of the genes that were up-regulated in Irg1−/− cells after Mtb infection were down-regulated in WT BMDMs (Fig. 5 A). Exogenous addition of physiologically relevant doses of itaconate (0.25 mM; Michelucci et al., 2013; Lampropoulou et al., 2016) to Mtb-infected Irg1−/− BMDMs switched the transcriptional signature to one similar to Mtb-infected WT BMDMs (Fig. 5 A). This result suggests that the effect of Irg1 deletion on transcriptional profiles was principally a result of the loss of itaconate production. Pathway enrichment analysis indicated that a lack of Irg1 expression in Mtb-infected BMDMs resulted in induction of inflammatory and chemoattractant genes downstream of NF-κB signaling, and correspondingly, addition of itaconate to Irg1−/− BMDMs reverses this effect (Fig. 5, B and C). These data show that Irg1 and its product itaconate function to limit inflammation during Mtb infection at the transcriptional level.

Figure 5.

Irg1 alters the transcriptional signature in Mtb-infected BMDMs. (A–C) Transcriptomic data from WT, Irg1−/−, and Irg1−/− + itaconate (Ita)–treated BMDMs infected with Mtb and analyzed at 4 h postinfection (hpi). (A) Heat map comparing the transcriptional changes that occur at 4 hpi in Irg1−/− BMDMs ± Ita and WT BMDMs (left). Genes that are up-regulated in WT BMDMs also are enriched in Irg1−/− + itaconate BMDMs at 4 hpi. Columns and rows show conditions and genes, respectively. Genes are ranked according to significance of differential expression and direction of change. Plot shows the running score for NF-κB gene set as the analysis moves down the ranked list (right). (B and C) Gene set enrichment analysis comparison for genes in NF-κB signaling (B) and inflammatory chemokine CXCL11 and IL1-β (C) between WT versus Irg1−/−, WT versus Irg1−/− + Ita, and Irg1−/− + Ita versus Irg1−/− BMDMs. Error bars designate SEM.

How does Irg1 regulate inflammation during Mtb infection? Irg1 has been reported to suppress production of TLR-triggered NF-κB–dependent cytokines, including TNF-α, through induction of the negative regulator A20 (Li et al., 2013; Jamal Uddin et al., 2016). Although an increased inflammatory response was detected in the lungs of Irg1−/− mice at 14 dpi, we failed to detect differences in TNF-α levels compared with WT lung homogenates. Thus, in the context of Mtb infection Irg1 appears to modulate inflammatory responses by dampening expression of a selected subset of NF-κB regulated genes. Analogously, exogenous itaconate treatment of activated macrophages or LPS treatment of Irg1−/− macrophages also did not affect TNF-α levels relative to their respective controls (Lampropoulou et al., 2016).

In summary, our experiments establish an essential role of Irg1 in regulating neutrophil-dependent inflammation during Mtb infection of the lung. We show that Irg1, likely through its ability to convert the TCA cycle intermediate cis-aconitate to itaconate, shapes the host immune responses through an immunometabolism axis to curtail Mtb-induced lung disease. As mouse Irg1 is ∼80% identical in amino acid sequence to human IRG1 with all five predicted cis-aconitate decarboxylase domains fully conserved (Michelucci et al., 2013), the development of pharmacological agents that enhance Irg1 function or promote itaconate production might minimize pathological inflammatory responses that cause severe lung injury associated with TB disease progression.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All procedures involving animals were conducted following the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for housing and care of laboratory animals and performed in accordance with institutional regulations after protocol review and approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine (protocol no. 20160118). Washington University is registered as a research facility with the United States Department of Agriculture and is fully accredited by the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The Animal Welfare Assurance is on file with Office for Protection from Research Risks–NIH. All animals used in these experiments were subjected to no or minimal discomfort. All mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, which is approved by the American Veterinary Association Panel on Euthanasia.

Mice

C57BL/6N (WT) mice were either purchased from Charles River or bred in-house. No differences in survival or disease progression during Mtb infection were observed in Irg1+/+ littermate controls or Irg1+/+ C57BL/6N mice obtained from Charles River in three independent experiments. B6.SJL (CD45.1) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Irg1−/− mice (embryonic stem cells obtained from KOMP [C57BL/6N background, reporter-tagged insertion with conditional potential, MGI: 103206]) were generated at Washington University and have been described previously (Lampropoulou et al., 2016). Adult mice (6–13 wk of age) of both sexes were used, and sex was randomized between experiments. Cre− Irg1fl/fl mice were generated as described previously (Coleman et al., 2015) with two loxP sites flanking exon 4 of Irg1. Irg1−/− mice were bred with FLPe “deleter” mice (Kanki et al., 2006) to facilitate deletion of lacZ and neomycin resistance cassettes between FRT sites and create Irg1fl/+ founder mice. The founder mice were backcrossed to C57BL6/J background using speed congenic approaches (>99% purity) and then interbred to generate Irg1fl/fl mice. These animals were crossed with Mrp8-Cre+–, LysM-Cre+– and CD11c-Cre+–(Jackson Laboratory) expressing mice to delete exon 4 of Irg1 from specific subsets of myeloid cells.

Generation of bone marrow chimeric mice

Bone marrow chimeric mice were generated by irradiation (900 Gy) of WT or Irg1−/− recipients and reconstitution with 107 bone marrow cells from WT or Irg1−/− donors. 6–8 wk after bone marrow transplantation, Irg1−/− (CD45.2) → WT (CD45.1), WT (CD45.1) → Irg1−/− and WT (CD45.1) → WT (CD45.2), and WT (CD45.1) + Irg1−/− (CD45.2) → WT (CD45.1) mice were bled to confirm chimerism by flow cytometry before Mtb infection.

Mouse infections

Mtb cultures in logarithmic growth phase (OD600 = 0.5–0.8) were washed with PBS + 0.05% Tween 80, sonicated to disperse clumps, and diluted in sterile water. Mice were exposed to 1.6 × 108 CFUs of Mtb, a dose chosen to deliver 100–200 CFUs of aerosolized Mtb per lung using an inhalation exposure system (Glas-Col). For each infection, lungs were harvested from at least two control mice, homogenized, and plated on 7H11 agar to confirm the input CFU dose. The mean dose determined at this time point was assumed to be representative of the dose received by all other mice infected concurrently. Mtb burden was determined after homogenizing the superior, middle, and inferior lobes of the lung or the entire spleen and plating serial dilutions on 7H11 agar. Colonies were counted after 3 wk of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Listeria monocytogenes (strain EGD) was stored at mid–logarithmic growth as frozen glycerol stocks. Thawed bacteria were diluted into pyrogen-free saline for intravenous injection into mice at a dose of 105 bacteria/mouse in 200 µl.

Mice were infected with IAV strain A/California/04/2009 H1N1 by intranasal inoculation of 105 or 106 tissue culture dose. At 5 dpi viral titer was assessed from bronchoalveolar (BAL) fluid by tissue culture dose.

Neutrophil depletions

Mice were administered 200 µg of anti-Ly6G mAb (1A8; BioXCell) or rat IgG2a isotype control mAb (2A3; BioXCell) diluted in sterile PBS (Hyclone) by intraperitoneal injection every 48 h, beginning at 10 dpi and ending at 20 or 34 dpi, depending on the experiment. For confirmation of depletion during survival experiments, lungs from one anti-Ly6G treated Irg1−/− control mouse and one isotype treated Irg1−/− control mouse were harvested from each independent experiment and analyzed by flow cytometry for reduction in CD45+/CD11b+Ly6Cmid cells.

Infection of BMDMs

Macrophages were obtained by culturing bone marrow cells in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, 100 U penicillin per ml, 100 µg streptomycin per ml, and 22 ng M-CSF (Peprotech)/ml for 6 d at 37°C, 5% CO2. Fresh media was added on day 3 of culture. After 6 d of culture, nonadherent cells were discarded. Adherent macrophages were switched into antibiotic-free media and seeded at 105 cells per well and 9 × 105 cells per well in tissue culture-treated 96- and 6-well plates, respectively. In some cases, macrophages were treated with physiologically relevant concentrations of 0.25 mM itaconic acid (Sigma) for 12 h before inoculation with Mtb (Michelucci et al., 2013). Mtb was grown to midlog phase, washed with PBS, sonicated to disperse clumps, and resuspended in antibiotic-free macrophage culture media. Macrophage cultures were inoculated by adding Mtb-containing media at a multiplicity of infection of 1 and centrifuging for 10 min at 200 g. Cells were washed twice with PBS to remove unbound Mtb, fresh culture media was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. In some cases, culture media was supplemented with 0.25 mM itaconic acid.

Bacterial cultures

Mtb strain Erdman and its derivatives were cultured at 37°C in 7H9 broth (Sigma) or on 7H11 agar (BD Difco) medium supplemented with 10% oleic acid/albumin/dextrose/catalase, 0.5% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween 80 (broth only). Listeria monocytogenes (strain EGD) was grown in a shaking culture in brain–heart infusion broth at 37°C to midlogarithmic growth, washed in PBS, and frozen as glycerol stocks at −80°C.

Generation of Mtb mutants

Mtb-GFP was generated by transforming the Mtb strain Erdman with a plasmid (pMV261-kan-GFP) that drives constitutive expression of GFP under the control of the hsp60 promoter. Cultures were grown in the presence of kanamycin to ensure plasmid retention. Δicl1 Mtb was generated by transducing the Mtb strain Erdman with a phage containing homology to nucleotides 556805–557527 and 558797–559447 to replace the endogenous icl1 gene with a hygromycin resistance cassette. Mutants were selected by culture on hygromycin-containing 7H11 agar. Individual hygromycin-resistant colonies were expanded by inoculation into hygromycin-supplemented 7H9 media. Replacement of the icl1 gene with the hygromycin resistance cassette was confirmed by Southern blotting of genomic DNA from expanded cultures.

Viral cultures

A/California/04/2009 H1N1 influenza viral stocks were prepared as previously described (Williams et al., 2016).

BAL lavage of IAV infected mice

For analysis of BAL fluid, mice were sacrificed by Avertin overdose, followed by anterior neck dissection and cannulation of the trachea with a 22-G catheter. BAL was performed with three washes of 0.8 ml of sterile Hanks’ balanced salt solution. BAL fluid was centrifuged and the cell-free supernatant was collected and stored for viral titer analysis.

Flow cytometry

Mice were perfused with sterile PBS and left lobes of lungs were digested at 37°C with 630 µg/ml collagenase D (Roche) and 75 U/ml DNase I (Sigma). All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200. Single cell suspensions were preincubated with Fc Block antibody (BD PharMingen) in PBS + 2% heat-inactivated FBS for 10 min at room temperature before staining. Cells were incubated with antibodies against the following markers: V500 anti-CD45.1 (clone A20), AF700 anti-CD45.2 (clone 104; eBioscience), AF700 anti-CD45 (clone 30 F-11), APC-Cy7 anti-CD11c (clone N418), PE anti-Siglec F (clone E50-2440; BD), PE-Cy7 anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8), PB or Qdot605 anti-Ly6C (clone AL-21/HK1.4; Biolegend/BD), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD11b (clone M1/70), APC anti-CD103 (clone 2E7; eBioscience), PB anti-CD3 (clone 17A2), PE-Cy7, APC anti-CD4 (clone RM4-5), PE-Cy7 anti-CD8 (clone53-6.7), anti-NK1.1 (clone PK136), and APC anti-Nos2 (clone CXNFT; all from eBioscience). Intracellular ROS were stained with MitoSOX red dye (Thermo Fisher). Absolute cell counts were determined using TruCount beads (BD). Cells were stained for 20 min at 4°C, washed, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS for 20 min at 4°C. Flow cytometry data were acquired on a cytometer (LSR Fortessa; BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Gating strategies are depicted in Fig. S2.

Cytokine/chemokine quantification

Lungs were homogenized in 5 ml of PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80. Homogenates were filtered (0.22 µm) twice and analyzed by BioPlex-Pro Mouse Cytokine 23-Plex Immunoassay (Bio-Rad).

Histology and imaging

Lung samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin (Thermo Fisher). Gross pathology images were acquired using a Power Shot G9 camera (Canon). For detailed histological analysis, lung lobes were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with H&E (Pulmonary Morphology Core, Washington University). Mtb bacilli were stained with Ziehl-Neelsen stain (Pulmonary Morphology Core). Images were acquired using NanoZoomer 2.0-HT System (Hamamatsu) or an Eclipse E400 camera (Nikon).

RNA-seq

BMDMs were harvested at 4 h after Mtb infection, and RNA was extracted using TRIZol reagent (Invitrogen). mRNA was extracted with oligo-dT beads (Invitrogen) and cDNA synthesized using custom oligo-dT primer with a barcode and adaptor-linker sequence (CCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-XXXXXXXX-T15). Samples were pooled based on Actb qPCR values, RNA–DNA hybrids degraded with acid-alkali treatment and a second sequencing linker (5′-AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTG-3′) was ligated with T4 ligase (NEB). After SPRI bead cleanup (Agencourt AMPure XP; Beckman Coulter), the mixture was PCR-enriched (12 cycles) and SPRI-purified, yielding final strand-specific RNA-seq libraries. Libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 (Illumina) using 40 × 10 bp paired-end sequencing. Second read (read-mate) was used for sample demultiplexing. Files obtained from the sequencing center were demultiplexed with fastq-multx tool. Fastq files for each sample were aligned to mm10 genome (Release M8 Gencode; GRCm38.p4) using STAR. Each sample was evaluated according to a variety of both pre- and postalignment quality control measures with Picard tools. Aligned reads were quantified using a quant3p script (Computer Technologies Laboratory, 2016) to account for specifics of 3′ sequencing: higher dependency on good 3′ annotation and lower level of sequence specificity close to 3′ end. Actual read counts were performed by HTSeq with enriched genome annotation and alignment with fixed multimapper flags. DESeq2 was used for analysis of differential gene expression. Preranked GSEA analysis was used to identify pathway enrichments in hallmark and canonical pathways.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All data are from at least two independent biological experiments with multiple mice in each group. No blinding was performed during animal experiments. Statistical differences were calculated using Prism 7 (GraphPad) using log-rank Mantel-Cox tests (survival), unpaired two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests (to compare two groups with nonparametric data distribution), and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (to compare more than two groups with parametric data distribution). Differences with a p-value of <0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Data and software availability

RNA-seq data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository under reference series number GSE98458.

Online supplemental materials

Further details including generation of Mtb mutants, protocols for bacterial cultures, viral cultures, BAL lavage, flow cytometry, chemokine/cytokine quantification, histology, imaging, RNA-seq, quantification, and statistical analysis can be found in the online supplemental methods. Fig. S1 shows that Irg1−/− mice are susceptible to ΔIcl1 Mtb, and infection of WT-Mtb or Mtb-GFP in WT and Irg1−/− mice and BMDM. Fig. S2 defines cellular infiltrates in the lungs of WT and Irg1−/− mice after Mtb infection and depletion of neutrophils in the lung. Fig. S3 shows that radiosensitive hematopoietic cells promote Irg1-mediated responses against Mtb and assessment of Irg1 exon 4 deletion in conditional gene-targeted mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 AI04972 (to M.S. Diamond), R01 AI118938 (to A.C.M. Boon), R01 AI125618 (to M.N. Artyomov), a Beckman Young Investigator Award from the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation (to C.L. Stallings), a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator Award (to C.L. Stallings), a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to B.T. Edelson), and the NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant (S10 RR027552) supported this study. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft supported S. Nair. The National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE-1143954) supported J.P. Huynh and A. Gounder. The government of the Russian Federation, grant 074-U01, supported E. Esaulova.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: S. Nair, J.P. Huynh, C.L. Stallings, and M.S. Diamond conceived and designed the study. S. Nair and J.P. Huynh contributed equally and performed many of the in vivo infection experiments with Mtb, histology, immunological experiments, flow cytometry, and data analysis. V. Lampropoulou worked with S. Nair and J.P. Huynh in setting up in vitro infections of neutrophils. E. Loginicheva, E. Esaulova, V. Lampropoulou, and M.N. Artyomov performed the RNA-seq analysis. S. Nair and M.S. Diamond are responsible for the breeding and genotyping of the Irg1−/− and Irg1fl/fl mouse colonies. A.P. Gounder and A.C.M. Boon designed and performed IAV infection experiments, and S. Nair analyzed the data. E.A. Schwarzkopf and T.R. Bradstreet performed Listeria monocytogenes infections, and B.T. Edelson performed the analysis. S. Nair, J.P. Huynh, M.N. Artyomov, M.S. Diamond, and C.L. Stallings contributed to study design. S. Nair and J.P. Huynh wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was edited initially by M.S. Diamond and C.L. Stallings, and subsequently by V. Lampropoulou, M.N. Artyomov, B.T. Edelson., A.C.M. Boon, and A.P. Gounder.

References

- Bloch H., and Segal W.. 1956. Biochemical differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis grown in vivo and in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 72:132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.L., Brennan K., Ngo T., Balaji P., Graham R.M., and Smith N.J.. 2015. Rapid Knockout and Reporter Mouse Line Generation and Breeding Colony Establishment Using EUCOMM Conditional-Ready Embryonic Stem Cells: A Case Study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 6:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Computer Technologies Laboratory 2016. quant3p. A set of scripts to 3′ RNA-seq quantification. Available at: https://github.com/ctlab/quant3p (Accessed February 27, 2018).

- Cooper A.M., Dalton D.K., Stewart T.A., Griffin J.P., Russell D.G., and Orme I.M.. 1993. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J. Exp. Med. 178:2243–2247. 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degrandi D., Hoffmann R., Beuter-Gunia C., and Pfeffer K.. 2009. The proinflammatory cytokine-induced IRG1 protein associates with mitochondria. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:55–68. 10.1089/jir.2008.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn M.F., Ramírez-Trujillo J.A., and Hernández-Lucas I.. 2009. Major roles of isocitrate lyase and malate synthase in bacterial and fungal pathogenesis. Microbiology. 155:3166–3175. 10.1099/mic.0.030858-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J.L., Chan J., Triebold K.J., Dalton D.K., Stewart T.A., and Bloom B.R.. 1993. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 178:2249–2254. 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.J., Boyle R.H., Astin J.W., Flores M.V., Oehlers S.H., Sanderson L.E., Ellett F., Lieschke G.J., Crosier K.E., and Crosier P.S.. 2013. Immunoresponsive gene 1 augments bactericidal activity of macrophage-lineage cells by regulating β-oxidation-dependent mitochondrial ROS production. Cell Metab. 18:265–278. 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höner Zu Bentrup K., Miczak A., Swenson D.L., and Russell D.G.. 1999. Characterization of activity and expression of isocitrate lyase in Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 181:7161–7167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal Uddin M., Joe Y., Kim S.K., Oh Jeong S., Ryter S.W., Pae H.O., and Chung H.T.. 2016. IRG1 induced by heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide inhibits LPS-mediated sepsis and pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 13:170–179. 10.1038/cmi.2015.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki H., Suzuki H., and Itohara S.. 2006. High-efficiency CAG-FLPe deleter mice in C57BL/6J background. Exp. Anim. 55:137–141. 10.1538/expanim.55.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmey J.M., Huynh J.P., Weiss L.A., Park S., Kambal A., Debnath J., Virgin H.W., and Stallings C.L.. 2015. Unique role for ATG5 in neutrophil-mediated immunopathology during M. tuberculosis infection. Nature. 528:565–569. 10.1038/nature16451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampropoulou V., Sergushichev A., Bambouskova M., Nair S., Vincent E.E., Loginicheva E., Cervantes-Barragan L., Ma X., Huang S.C., Griss T., et al. 2016. Itaconate Links Inhibition of Succinate Dehydrogenase with Macrophage Metabolic Remodeling and Regulation of Inflammation. Cell Metab. 24:158–166. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang P., Wang C., Han C., Meng J., Liu X., Xu S., Li N., Wang Q., Shi X., and Cao X.. 2013. Immune responsive gene 1 (IRG1) promotes endotoxin tolerance by increasing A20 expression in macrophages through reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 288:16225–16234. 10.1074/jbc.M113.454538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden B.A., and Purohit S.. 1977. Itaconate, an isocitrate lyase-directed inhibitor in Pseudomonas indigofera. J. Bacteriol. 131:136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney J.D., Höner zu Bentrup K., Muñoz-Elías E.J., Miczak A., Chen B., Chan W.T., Swenson D., Sacchettini J.C., Jacobs W.R. Jr., and Russell D.G.. 2000. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature. 406:735–738. 10.1038/35021074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelucci A., Cordes T., Ghelfi J., Pailot A., Reiling N., Goldmann O., Binz T., Wegner A., Tallam A., Rausell A., et al. 2013. Immune-responsive gene 1 protein links metabolism to immunity by catalyzing itaconic acid production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:7820–7825. 10.1073/pnas.1218599110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Elías E.J., and McKinney J.D.. 2005. Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 are jointly required for in vivo growth and virulence. Nat. Med. 11:638–644. 10.1038/nm1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Elías E.J., Upton A.M., Cherian J., and McKinney J.D.. 2006. Role of the methylcitrate cycle in Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism, intracellular growth, and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1109–1122. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05155.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi B., and Behar S.M.. 2011. Regulation of neutrophils by interferon-γ limits lung inflammation during tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 208:2251–2262. 10.1084/jem.20110919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvi S., Warner D.F., Kana B.D., McKinney J.D., Mizrahi V., and Dawes S.S.. 2008. Functional characterization of a vitamin B12-dependent methylmalonyl pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for propionate metabolism during growth on fatty acids. J. Bacteriol. 190:3886–3895. 10.1128/JB.01767-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G.D., Pinto A.K., Doll B., and Boon A.C.. 2016. A North American H7N3 Influenza Virus Supports Reassortment with 2009 Pandemic H1N1 and Induces Disease in Mice without Prior Adaptation. J. Virol. 90:4796–4806. 10.1128/JVI.02761-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2016. Global tuberculosis report. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23098en/s23098en.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository under reference series number GSE98458.