Abstract

Purpose:

To address research gaps regarding women Veterans’ alcohol consumption and mortality risk as compared to non-Veterans, the current study evaluated whether alcohol consumption amounts differed between women Veterans and non-Veterans, whether Veterans and non-Veterans within alcohol consumption groups differed on all-cause mortality, and whether Veteran status modified the association between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality.

Design and Methods:

Six alcohol consumption groups were created using baseline data from the Women’s Health Initiative Program ( N = 145,521): lifelong abstainers, former drinkers, less than 1 drink/week (infrequent drinkers), 1–7 drinks/week (moderate drinkers), 8–14 drinks/week (moderately heavy drinkers), and 15 or more drinks/week (heavy drinkers). The proportions of Veteran and non-Veteran women within each alcohol consumption category were compared. Mortality rates within each alcohol consumption category were compared by Veteran status. Cox proportional hazard models, including a multiplicative interaction term for Veteran status, were fit to estimate adjusted mortality hazard (rate) ratios for each alcohol consumption category relative to a reference group of either lifelong abstainers or moderate drinkers.

Results:

Women Veterans were less likely to be lifelong abstainers than non-Veterans. Women Veterans who were former or moderate drinkers had higher age-adjusted mortality rates than did non-Veterans within these alcohol consumption categories. In the fully adjusted multivariate models, Veteran status did not modify the association between alcohol consumption category and mortality with either lifelong abstainers or moderate drinkers as referents.

Implications:

The results suggest that healthcare providers may counsel Veteran and non-Veteran women in similar ways regarding safe and less safe levels of alcohol consumption.

Keywords: Mortality risk, Drinking, Veteran status, Postmenopausal women, Health behavior practices

The Women’s Health Initiative Program (WHI) has provided an unprecedented window into postmenopausal women’s health. Because of the vast numbers of women involved, it has been possible to focus on key subsets of women whose health risks and concerns may be unique ( Garcia et al., 2014 ; Valanis et al., 2000 ). One such group is the roughly 3,700 women in the WHI who reported serving in the U.S. military. Other studies using large, nationally representative datasets have found that compared to women non-Veterans, women Veterans report inferior general health, higher incidence of unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking and lack of exercise, and higher incidence of mental and chronic health conditions ( Lehavot, Hoerster, Nelson, Jakupcak, & Simpson, 2012 ; Lehavot et al., 2014 ). The first study conducted that compared Veterans and non-Veterans using the WHI data found health disparities consistent with these previous studies and also found higher rates of all-cause mortality for Veterans relative to non-Veterans ( Weitlauf et al., 2015 ). Thus, research on various modifiable health-risk behaviors associated with early mortality that may differentially affect women Veterans is indicated.

Women Veterans, Alcohol Consumption, and Mortality

Various levels of alcohol consumption may constitute modifiable risk behaviors that could contribute to the mortality disparity apparent for women Veterans relative to non-Veterans. Most of the extant research on women Veterans’ drinking has been conducted with VA patients and only a few studies have compared women Veterans at large to women non-Veterans (see Hoggatt et al., 2015 for a systematic review of literature pertaining to women Veterans’ alcohol and drug use). The population-based studies compared rates of binge drinking between Veteran and non-Veteran women ( Grossbard et al., 2013 ; Lehavot et al., 2012 , 2014 ), and one of these also compared rates of heavy drinking ( Grossbard et al., 2013 ). None of these studies found significant differences between women Veterans and non-Veterans. A fourth study that utilized national survey and VA data reported the rates of positive screens for alcohol misuse among past-year drinkers were comparable for women non-Veterans and Veterans (35% and 37%, respectively; Delaney et al., 2014 ). Although these results suggest that women Veterans may not have an elevated risk for engaging in heavy alcohol consumption or problematic alcohol use relative to non-Veteran women, additional comparisons of different drinking parameters using data from other large scale studies, such as the WHI, could increase confidence in the consistency of findings or could identify more nuanced differences that may help healthcare providers of women Veterans to optimally screen and treat their patients. Comparisons using the WHI data would also provide specific information about women 50 years of age and older.

Among women in the general population, being a lifelong abstainer, a former drinker, or a current heavy drinker are all associated with elevated risk of early mortality compared to being a moderate drinker ( Bertoia et al., 2013 ; Di Castelnuovo et al., 2006 ; Fuchs et al., 1995 ; Klatsky & Udaltsova, 2007 ; Liao, McGee, Cao, & Cooper, 2000 ; McCaul et al., 2010 ; Wang et al., 2014 ). A study using the WHI data reported similar results regarding the relationships between alcohol consumption categories and mortality rates up to 8 years post-baseline ( Freiberg et al., 2009 ). This study also reported that the relationship between alcohol consumption levels and mortality varied by race/ethnicity ( Freiberg et al., 2009 ), suggesting the importance of evaluating subgroups of women to understand who might be at particular risk in order to optimize screening and care provision. One study among women VA patients found that those with severe alcohol misuse on a standard screening measure had seven times the 2-year mortality risk of women scoring in the mild misuse range ( Harris, Bradley, Bowe, Henderson, & Moos, 2010 ). However, because this study analyzed data from VA patients only, it does not address the issue of whether various alcohol consumption levels have differential bearing on mortality risk for women Veterans and non-Veterans.

Comparisons between Veteran and non-Veteran women based on the full range of alcohol consumption levels, including being either a lifelong abstainer or a former drinker, have not yet been undertaken, and no studies have compared Veteran and non-Veteran women’s mortality risk in the context of different alcohol consumption levels. Thus, it is unclear whether the relationships between alcohol consumption and mortality seen for women at large are pertinent to the subgroup of women Veterans in the WHI. The current study explored questions related to each of these gaps in the literature by comparing rates of membership in various alcohol consumption groups across women Veterans and non-Veterans, assessing whether mortality rates within each alcohol consumption group were comparable for Veterans and non-Veterans, and evaluating whether Veteran status modifies the relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality rates. Consistent with other studies on alcohol and mortality ( Di Castelnuovo et al., 2006 ; Fuchs et al., 1995 ; Klatsky & Udaltsova, 2007 ), we treated both lifelong abstainers and moderate drinkers as reference groups.

Design and Methods

Study Design

The WHI program consisted of three clinical trials (CT) that evaluated hormone therapy, dietary modification, and calcium and vitamin D supplementation as well as an observational study. The study design and implementation for the WHI study have been described in detail elsewhere ( Anderson et al., 2003 ; Langer et al., 2003 ; Women’s Health Initiative Study Group, 1998 ). Briefly, women were recruited at 40 clinical centers in the United States and were eligible to participate if they were aged 50–79 years, postmenopausal, planned to remain in the area, did not report having been an excessive drinker in the past 5 years (i.e., (a) self-evaluated “excessive drinker,” (b) had consumed the equivalent of a fifth of liquor in 1 day, or (c) had 2 or more weeks of drinking seven or more drinks each day), did not report needing to use more drugs to feel desired effects, did not report serious emotional problems that would interfere with study participation, and had an estimated survival of at least 3 years; the CTs each had additional eligibility criteria. A total of 161,808 women were enrolled from 1993 to 1998. The 145,521 participants who provided information on Veteran status were included in the current analyses. The main WHI program was completed in 2005, but two WHI Extension Studies enabled the continuation of data collection and outcomes assessment through 2015.

At the baseline assessment, participants completed standardized questionnaires about demographics, health behavior, and psychosocial characteristics and these data were used to characterize the exposure and covariate measures for the current analyses. Mortality data were collected through 2014, thus comprising between 16 and 21 years of study follow-up.

The study procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at all 40 of the participating clinical centers. All of the participants provided written informed consent at WHI baseline and again at enrollment in each of the Extension Studies. The VA Puget Sound Healthcare System Institutional Review Board and Research and Development office reviewed and approved the current study.

Measures

Veteran Status

Veteran status was consistent with having responded affirmatively to the question, “Have you served in the U.S. armed forces on active duty for a period of 180 days or more?”

Alcohol Consumption Groups

Consumption of alcohol was characterized based on the responses to two questions, the first being “During your entire life, have you had at least 12 drinks of any kind of alcoholic beverage?” The second question was asked as part of a validated Food Frequency (paper-based) Questionnaire (FFQ), which was answered independently by each participant and estimated to take approximately 45min to complete ( Patterson et al., 1999 ). The primary section of the FFQ is comprised of 122 foods or food groups and asked about the average frequency of intake in the previous 3 months, with nine options ranging from never to over six daily for beverages. Specific alcoholic beverages itemized in the FFQ were beer, wine, and liquor. The FFQ also included a question about the participants’ usual serving size (small, medium, or large), referencing a medium-sized serving of beer as 12 ounces, wine as 6 ounces, and liquor as 1.5 ounces. The alcohol intake questions on the WHI FFQ were validated in a subsample of women using 4-day food records and interviewer-obtained 24-hr food recalls with a correlation of 0.86 ( Patterson et al., 1999 ).

Based on the responses to the alcohol consumption questions, women were categorized into the following groups: (a) consumed alcohol on fewer than 12 occasions in their lives (lifelong abstainers), (b) drank in the past but reported no longer drinking (former drinkers), (c) consumed less than 1 drink per week (infrequent drinkers), (d) consumed 1–7 drinks per week (moderate drinkers), (e) consumed 8–14 drinks per week (moderately heavy drinkers), and (f) consumed 15 or more drinks per week (heavy drinkers). These groupings are primarily focused on weekly number of drinks rather than drinks per day as was the case in most other epidemiological studies of mortality and alcohol consumption ( di Castelnuovo et al., 2006 ; Wang et al., 2014 ). This was done because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) guidelines indicate that up to seven drinks per week is the recommended safe limit for women (Centers for Disease Control, n.d.; http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm ; Rehm, Gmel, Sempos, & Trevisan, 2003 ).

Model Covariates: Demographic and Health Behavior Variables

In keeping with the Biopsychosocial Model of Health and Aging ( Seeman & Crimmins, 2001 ; see discussion in Editorial 1 by Reiber & LaCroix, forthcoming), we considered demographic characteristics and health-risk behaviors that have been found to vary between Veterans and non-Veterans and that also affect mortality rates as potential confounders of the association between alcohol consumption and mortality.

Demographic variables included age, race/ethnicity, marital status, living alone, family income, and highest educational level completed. Age was calculated using date of birth and date of baseline visit information. All other demographic variables were self-reported.

Tobacco use was measured in pack-years, calculated using self-reported years of smoking and the average number of cigarettes smoked per day. Height and weight were measured by study staff at the baseline health examination visit using a calibrated stadiometer and standard scale and without outdoor clothing. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Obesity was characterized as a BMI greater than or equal to 30.0 kg·m −2 , as defined in the Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1988 ). Physical activity level was characterized as the total energy expended in metabolic equivalent hours per week calculated from self-reported frequency and duration of walking and mild to strenuous exercise ( Ainsworth et al., 1993 ).

All-Cause Mortality

All deaths that occurred from baseline through 2010 were adjudicated through the following means: trained physicians using hospital or medical records, coronary or autopsy reports, death certificates, or National Death Index reports. After 2010, the deaths of some participants were confirmed through such adjudication practices as well as through direct notification from the decedent’s family, friends, or personal physician. The National Death Index (plus) was checked over the course of the study for all participants, including those lost to follow-up or those who did not consent to participate in the Extension Studies. The last National Death Index search was conducted in 2013 and captured deaths through 2011, but information on deaths from other sources was available through 2014.

Statistical Analysis

The distributions of the demographic characteristics and health behaviors were compared by Veterans status. Frequencies were calculated for categorical variables, and we tested for differences in the distribution of these variables by Veteran status using Pearson chi-square tests. Means and SD were reported for continuous variables, and differences by Veteran status were assessed with t -tests. The age-adjusted predicted probabilities of being in an alcohol consumption group for Veterans and non-Veterans were derived from a multinomial logistic regression model, using the six-category alcohol consumption variable as the outcome. Age-standardized mortality rates (per 1,000 persons) were calculated by alcohol consumption group for Veterans and non-Veterans, and differences between Veterans’ and non-Veterans’ mortality rates within each alcohol consumption group were compared. The entire WHI sample in age decades was used as the standard population for age-standardized rates.

Cox proportional hazards models were fit to estimate the association between alcohol consumption group at baseline and all-cause mortality. Alcohol consumption groups were coded as dummy variables to estimate associations relative to either lifelong abstainers or moderate drinkers (i.e., we fit two sets of models, one for each of the reference groups). We estimated mortality hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that describe the relative change in mortality rates associated with being in a given alcohol consumption group relative to the reference group. In each of the two sets, we fit three successive models: (a) alcohol consumption groups only (yielding crude HRs), (b) alcohol consumption groups and baseline age (age-adjusted HRs), and (c) alcohol consumption groups, baseline age, and all other covariates defined above (fully adjusted HRs). Event times were characterized from time of enrollment to death or censored at last known follow-up. We checked model assumptions by examining the Martingale residuals and found no obvious violations ( Therneau, Grambsch, & Fleming, 1990 ).

To evaluate whether the relationship between alcohol consumption group and all-cause mortality varied between Veterans and non-Veterans (i.e., whether Veteran status was a modifier of the alcohol–mortality association), our models included product terms for Veteran status and each of the alcohol group indicator variables, thus enabling us to evaluate effect measure modification (heterogeneity) of the HRs between alcohol consumption category and mortality by Veteran status based on Wald tests of whether the coefficients on the product terms were equal to 0. The HRs for mortality and each alcohol consumption group were estimated separately for women Veterans and non-Veterans via postestimation using the fitted model that included all product terms (regardless of whether tests for whether coefficients on the product terms were different from 0 were statistically significantly). All analyses were completed using SAS v9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

Of the 145,521 WHI women who reported whether they were Veterans at baseline, 3,719 (2.6%) reported being Veterans. Demographic characteristics and health behaviors at baseline by Veterans status are shown in Table 1 . Veteran women were an average of 3.8 years older at baseline compared to non-Veterans and were more likely to be White, not married, and a college graduate. Veteran women were also more likely to be a former or current smoker at baseline but had higher average levels of physical activity.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Veteran Status

| Characteristic | Veteran, n = 3,719 | Non-Veteran, n = 141,802 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years, mean ( SD ) | 67.1 (7.9) | 63.3 (7.2) | <.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <.0001 | ||

| White | 3,239 (87.4) | 116,617 (82.5) | |

| Black | 263 (7.1) | 12,874 (9.1) | |

| Other | 204 (5.5) | 11,938 (8.4) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Presently married or marriage like | 1,807 (48.7) | 88,189 (62.4) | |

| Divorced/separated | 686 (18.5) | 22,709 (16.1) | |

| Widowed | 835 (22.5) | 24,358 (17.2) | |

| Never married | 381 (10.3) | 6,063 (4.3) | |

| Family income, n (%) | <.0001 | ||

| <$20,000 | 629 (17.9) | 21,823 (16.5) | |

| $20,000–$49,999 | 1,728 (49.2) | 58,778 (44.4) | |

| ≥$50,000 | 1,157 (32.9) | 51,799 (39.1) | |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | <.0001 | ||

| High school, GED, or less | 443 (12.0) | 31,708 (22.5) | |

| Some college | 1,522 (41.1) | 53,197 (37.8) | |

| College graduate or higher | 1,740 (47.0) | 55,975 (39.7) | |

| Health behaviors | |||

| Smoking status, n (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 1,631 (44.8) | 71,573 (51.1) | |

| Past smoker | 1,693 (46.5) | 58,838 (42.0) | |

| Current smoker | 317 (8.7) | 9,552 (6.8) | |

| Pack-years, mean ( SD ) | 13.4 (21.9) | 9.9 (18.5) | <.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m 2 , mean ( SD ) | 27.9 (5.8) | 27.9 (6.0) | .39 |

| Body mass index categories | .06 | ||

| Underweight | 44 (1.2) | 1,248 (0.9) | |

| Normal weight | 1,247 (33.9) | 48,639 (34.6) | |

| Overweight | 1,321 (35.9) | 48,524 (34.5) | |

| Obese | 1,068 (29.0) | 42,083 (30.0) | |

| Physical activity, MET-hours per week, mean ( SD ) | 13.2 (14.1) | 12.5 (13.7) | .003 |

| Baseline alcohol use, n (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Lifelong abstainer | 250 (7.9) | 15,521 (12.6) | |

| Former drinker | 769 (24.2) | 26,357 (21.3) | |

| Consumes <1 drink/week | 712 (22.4) | 28,900 (23.4) | |

| Consumes 1–7 drinks/week | 1,116 (35.1) | 40,758 (33.0) | |

| Consumes 8–14 drinks/week | 202 (6.3) | 6,777 (5.5) | |

| Consumes ≤15 drinks/week | 135 (4.2) | 5,171 (4.2) |

Note: GED, General Equivalency Degree; MET, metabolic equivalent.

Alcohol Consumption Categories by Veteran Status

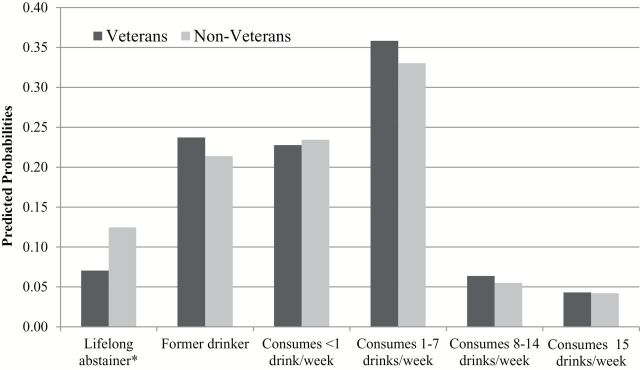

In descriptive (unadjusted) analyses, the proportions of women within each alcohol consumption category differed overall between Veterans and non-Veterans ( Table 1 ). Women Veterans were less likely to report being a lifelong abstainer, but more likely to report being a former drinker or someone who consumes 1–14 drinks per week. Examination of the age-adjusted predicted probabilities showed that only women in the lifelong abstainer group differed significantly across Veteran status ( Figure 1 ): for Veterans, the predicted probability was 7.1% (95% CI: 6.2%–7.9%) compared to 12.5% (95% CI: 12.3%–12.7%) for non-Veteran women ( p < .01).

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted predicted probabilities of being in an alcohol consumption group by Veteran status.

* p <.01 comparing Veterans to non-Veterans.

Mortality Rates by Veteran Status Within Alcohol Consumption Categories

The age-adjusted mortality rates for each alcohol consumption group by Veteran status are shown in Table 2 . Veterans and non-Veterans’ mortality rates differed significantly only within the former drinker and the moderate alcohol consumption groups, with Veterans having higher mortality rates than non-Veterans within each of these categories ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

All-Cause Mortality Rates by Baseline Drinking Behavior and Veteran Status

| No. of events | Total person-years | Age-adjusted rate a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Veterans | |||

| Lifelong abstainer | 77 | 3,581.7 | 14.4 |

| Former drinker | 288 | 10,535.5 | 20.6 b |

| Consumes <1 drink/week | 229 | 10,263.1 | 14.4 |

| Consumes 1–7 drinks/week | 348 | 16,366.7 | 14.1 b |

| Consumes 8–14 drinks/week | 64 | 2,939.7 | 13.4 |

| Consumes ≤15 drinks/week | 54 | 1,911.0 | 20.4 |

| Non-Veterans | |||

| Lifelong abstainer | 3,414 | 226,648.4 | 13.7 |

| Former drinker | 6,636 | 381,457.7 | 17.1 b |

| Consumes <1 drink/week | 5,385 | 440,039.0 | 12.6 |

| Consumes 1–7 drinks/week | 7,051 | 629,326.3 | 11.6 b |

| Consumes 8–14 drinks/week | 1,252 | 104,959.6 | 12.2 |

| Consumes ≤15 drinks/week | 1,179 | 78,088.5 | 15.8 |

Notes: a Standard population is all WHI in age decades.

b Age-adjusted mortality rate difference between Veterans and non-Veterans; p = .01.

Modification of Veteran Status on the Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Mortality

Lifelong Abstainers as Referent

In the unadjusted model for alcohol consumption category and mortality, with lifelong abstainers as the referent, the coefficients on the product terms for Veteran status in the infrequent and moderate drinker categories were statistically significant. These results indicate that there was less of an apparent protective effect of these alcohol consumption categories for Veterans than for non-Veterans relative to being a lifelong abstainer ( Table 3 ). Modification by Veteran status was no longer statistically significant after adjustment for age and subsequent adjustment for all covariates.

Table 3.

Mortality HRs Associated With Baseline Alcohol Use by Veteran Status With Lifelong Abstainers as Referent

| Crude HR (95% CI) | Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Fully adjusted HR a (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Veterans | |||

| Lifelong abstainer | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Former drinker | 1.30 (1.01–1.67) | 1.32 (1.03–1.70) | 1.05 (0.81–1.38) |

| Consumes <1 drink/week | 1.04 (0.80–1.35) b | 1.04 (0.80–1.34) | 0.87 (0.66–1.15) |

| Consumes 1–7 drinks/week | 0.98 (0.77–1.26) b | 0.91 (0.71–1.16) | 0.84 (0.64–1.09) |

| Consumes 8–14 drinks/week | 1.00 (0.72–1.40) | 0.90 (0.65–1.26) | 0.71 (0.50–1.01) |

| Consumes ≤15 drinks/week | 1.32 (0.93–1.87) | 1.30 (0.92–1.84) | 0.95 (0.65–1.39) |

| Non-Veterans | |||

| Lifelong abstainer | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Former drinker | 1.15 (1.11–1.20) | 1.28 (1.23–1.34) | 1.06 (1.02–1.11) |

| Consumes <1 drink/week | 0.79 (0.76–0.82) b | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) |

| Consumes 1–7 drinks/week | 0.72 (0.69–0.75) b | 0.84 (0.81–0.88) | 0.80 (0.76–0.83) |

| Consumes 8–14 drinks/week | 0.76 (0.71–0.81) | 0.88 (0.82–0.93) | 0.79 (0.74–0.85) |

| Consumes ≤15 drinks/week | 0.98 (0.91–1.04) | 1.17 (1.09–1.25) | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) |

Notes: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

a Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, WHI study arm, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, body mass index, and physical activity. Results for Veterans and Non-Veterans were obtained using postestimation prediction based on the fitted model with product terms for alcohol use category and Veteran status.

b p < .05 for product term of alcohol use category and Veteran status.

Estimated HRs for Veterans and non-Veterans for each alcohol consumption category are displayed in Table 3 . Based on the unadjusted mortality HRs for Veteran women , former drinkers had higher mortality rates than lifelong abstainers (the HR was greater than 1 and statistically significant). However, this association was attenuated and no longer statistically significant after full adjustment. For Veteran women in all other alcohol consumption groups, relative to lifelong abstainers, no statistically significant crude or adjusted associations with mortality were observed. Based on the unadjusted mortality HRs for non-Veteran women , former drinkers had higher mortality rates than did lifelong abstainers, and the HRs were greater than 1 and statistically significant even after adjustment for age and other covariates. In contrast, the crude mortality HRs for non-Veteran women who were infrequent drinkers, moderate drinkers, and moderately heavy drinkers indicated statistically significant lower mortality rates relative to lifelong abstainers ( Table 3 ); the HRs were slightly attenuated but remained statistically significant with age-only and full adjustments. Among non-Veterans, heavy drinkers had lower mortality rates relative to lifelong abstainers after adjustment for covariates.

Moderate Drinkers as Referent

In the unadjusted model using moderate drinkers as the referent, the coefficients on the product terms for Veteran status and the lifelong abstainer and former drinker categories on mortality were statistically significant. These results indicate that the apparent harmful effect associated with being in either of these categories relative to being in the moderate drinker category was attenuated for Veterans compared with non-Veterans ( Table 4 ). Modification by Veteran status was no longer statistically significant in the age- and fully adjusted models.

Table 4.

Mortality HRs Associated With Baseline Alcohol Use by Veteran Status With Moderate Drinkers (Consumes 1–7 Drinks per Week) as Referent

| Crude HR (95% CI) | Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | Fully adjusted HR a (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Veterans | |||

| Lifelong abstainer | 1.02 (0.80–1.30) b | 1.10 (0.86–1.41) | 1.19 (0.92–1.55) |

| Former drinker | 1.32 (1.13–1.55) b | 1.45 (1.24–1.70) | 1.26 (1.07–1.48) |

| Consumes <1 drink/week | 1.06 (0.90–1.25) | 1.14 (0.97–1.35) | 1.04 (0.87–1.24) |

| Consumes 1–7 drinks/week | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Consumes 8–14 drinks/week | 1.02 (0.78–1.33) | 0.99 (0.76–1.30) | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) |

| Consumes ≤15 drinks/week | 1.34 (1.01–1.79) | 1.43 (1.07–1.90) | 1.14 (0.83–1.55) |

| Non-Veterans | |||

| Lifelong abstainer | 1.40 (1.34–1.45) b | 1.19 (1.14–1.24) | 1.26 (1.20–1.32) |

| Former drinker | 1.61 (1.56–1.66) b | 1.52 (1.47–1.58) | 1.34 (1.29–1.39) |

| Consumes <1 drink/week | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) |

| Consumes 1–7 drinks/week | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Consumes 8–14 drinks/week | 1.06 (1.00–1.13) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 1.00 (0.93–1.06) |

| Consumes ≤15 drinks/week | 1.36 (1.28–1.45) | 1.39 (1.31–1.48) | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) |

Notes: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

a Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, WHI study arm, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, body mass index, and physical activity. Results for Veterans and Non-Veterans were obtained using postestimation prediction based on the fitted model with product terms for alcohol use category and Veteran status.

b p < .05 for product term of alcohol use category and Veteran status.

The models that used moderate drinkers as the reference group are presented in Table 4 . Among Veterans , former drinkers had higher mortality rates (i.e., a crude HR greater than 1) relative to moderate drinkers, and this HR remained statistically significant after adjusting for age and other covariates. Veteran women who were heavy drinkers had higher mortality rates in the crude and age-adjusted models, respectively, but the HR was not significant after full adjustment. Relative to women Veterans who were moderate drinkers, no differences in mortality rates were observed for lifelong abstainers, infrequent drinkers, and moderately heavy drinkers. For non-Veterans , women who were lifelong abstainers, former drinkers, infrequent drinkers, and heavy drinkers had significantly higher mortality rates than moderate drinkers in the crude, age-adjusted, and fully adjusted models.

Discussion

This study evaluated whether alcohol consumption levels differed between women Veterans and non-Veterans, whether Veterans and non-Veterans within each alcohol consumption group differed in their rates of all-cause mortality, and whether Veteran status modified the association between alcohol consumption group and all-cause mortality. In the process of evaluating whether Veteran status modified the association between alcohol consumption group and mortality, we were able to replicate findings regarding alcohol and mortality among women in the context of this large WHI dataset of over 145,000 postmenopausal women who were followed for up to 21 years.

Alcohol Consumption Groups by Veteran Status and Mortality Risk

With regard to membership in the various alcohol consumption groups, we found that Veteran women were significantly less likely than non-Veterans to be lifelong abstainers. Additionally, we found nearly identical age-adjusted probabilities of women Veterans (4.3%) and non-Veterans (4.2%) who were heavy drinkers (15+ drinks/week). To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare rates of lifelong alcohol abstention and detailed current (baseline) alcohol consumption between women Veterans and non-Veterans. Our finding that women Veterans and non-Veterans had similar proportions of heavy drinkers is consistent with previous population-based studies that found no differences in rates of binge ( Grossbard et al., 2013 ; Lehavot et al., 2012 , 2014 ) or heavy drinking ( Grossbard et al., 2013 ) between Veteran and non-Veteran women.

In age-adjusted analyses, mortality rates within each drinker group were higher for women Veterans than non-Veterans in the former and moderate drinker groups. The reasons for these elevated mortality rates among Veterans are not clear, but it is plausible that there are risk factors for early mortality that are disproportionately distributed across both alcohol consumption groups and Veteran status. For example, a careful examination of smoking behavior would be reasonable given the consistent finding in this and other studies that women Veterans are more likely to be smokers than women non-Veterans ( Lehavot et al., 2012 ). Drinking and smoking commonly co-occur ( Falk, Yi, & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 2006 ), and there is heavy mortality risk associated with smoking ( Iversen, Hannaford, Lee, Elliott, & Fielding, 2010 ; Shaw & Agahi, 2012 ).

When lifelong abstainers were used as the referent group, Veteran status modified the relationship between alcohol consumption group and all-cause mortality rates only in the unadjusted model. In unadjusted analyses, the lower rates of mortality for infrequent and moderate drinkers relative to lifelong abstainers were only evident for non-Veterans and were not observed for Veterans. However, these findings were attenuated in the age-adjusted and fully adjusted models. When moderate drinkers were used as the referent group, we similarly found that Veteran status modified the relationship between alcohol consumption group and all-cause mortality only in the unadjusted model, such that Veteran status was associated with lower risk of early mortality among lifelong abstainers or former drinkers relative to moderate drinkers. Again, these findings were no longer significant in the age-adjusted and fully adjusted models. This general pattern, where some crude HRs differed by Veteran status but the adjusted HRs did not, indicates that the higher mortality rates seen among Veterans in the unadjusted models may be accounted for by one or more of these factors and not by Veteran status. These findings further suggest that identifying correlates of moderate drinking, such as smoking, that put Veteran women at elevated risk of mortality relative to their non-Veteran peers is an important next step.

Our overall findings from the models with lifelong abstainers as the referent group are largely consistent with the extant literature. We found that infrequent drinkers, moderate drinkers, and moderately heavy drinkers had lower relative rates of mortality compared to lifelong abstainers (see Wang et al., 2014 ), while former drinkers had higher relative rates of mortality ( Klatsky & Udaltsova, 2007 ), even after accounting for age, other demographic characteristics, and key health-risk behaviors, such as pack years of smoking. Although these findings were only significant for non-Veterans, the HRs for the two groups of women were similar (the wider CIs for the HRs among Veteran women reflect the smaller sample size of Veteran women in the WHI). We did not, however, find that women who were heavy drinkers were at elevated risk of mortality relative to lifelong abstainers, which is not consistent with most other research in this area ( di Castelnuovo et al., 2006 ; Klatsky & Udaltsova, 2007 ; Wang et al., 2014 ) but is consistent with the other study using the WHI data ( Freiberg et al., 2009 ). This could be due, in part, to the WHI’s exclusion of women reporting excessive alcohol or drug use in the 5 years preceding the baseline assessment.

When moderate drinkers were used as the referent group, being a heavy drinker was associated with higher rates of all-cause mortality among the large sample of non-Veteran women in unadjusted, age-adjusted, and fully adjusted models. Additionally, consistent with the extant literature, we did not find strong evidence of a difference between moderately heavy drinkers and moderate drinkers with regard to all-cause mortality rates ( Knott, Coombs, Stamatakis, & Biddulph, 2015 ; McCaul et al., 2010 ). However, we did find that being a former drinker was associated with significantly elevated risk of mortality relative to being a moderate drinker ( di Castelnuovo et al., 2006 ).

Clinical Implications

Although the results from the fully adjusted models suggested that Veteran status does not modify the relationship between alcohol consumption categories and mortality risk, we did find that within the group of former drinkers and within the group of moderate drinkers, women Veterans were at increased risk of mortality compared with non-Veterans in age-adjusted analyses. As noted above, these findings suggest that it may not be the drinking itself that is increasing women Veterans’ risk but the presence of other risk behaviors, such as smoking, that frequently co-occur with drinking. While further research in this area is warranted, providers who treat women Veterans are encouraged to evaluate other potential known risk factors for early mortality, such as smoking status, of those who are former and moderate drinkers, so that appropriate interventions may be provided to mitigate risk of early mortality among these women.

The finding that being a heavy drinker was associated with a higher rate of mortality relative to moderate drinking suggests that heavier drinkers would likely benefit from advice to moderate their alcohol consumption. A recent meta-analysis indicated that heavy drinkers who either abstain or reduce their drinking to moderate levels reduced their risk of mortality compared with heavy drinkers who did not reduce their alcohol consumption ( Roerecke, Gual, & Rehm, 2013 ). Although heavier drinking women may remain at relatively higher risk of death than those with consistent moderate alcohol consumption, even after cutting back or stopping drinking, information on the health risks of heavy drinking, including higher mortality rates, may be useful to build women’s motivation to change unhealthy drinking behavior.

Our finding that women who drank more than 7 drinks/week (i.e., above the federal guidelines for safer alcohol consumption) but less than 15 drinks/week were at lower risk for all-cause mortality than lifelong abstainers and did not differ appreciably from moderate drinkers, also warrants comment. This finding is consistent with the broader literature on women, alcohol consumption, and all-cause mortality ( Knott et al., 2015 ; McCaul et al., 2010 ), but it potentially poses a conundrum for women and their healthcare providers in terms of providing clear guidance about safe levels of drinking. Although all-cause mortality is clearly an important health outcome, it needs to be considered in the larger context of health and overall quality of life, with decisions about amounts of alcohol consumption integrating these broader considerations. For example, prior research has demonstrated that women who consumed seven or more drinks per week on average at baseline were at elevated risk for later onset nonmelanoma skin cancer ( Kubo et al., 2014 ) and some types of breast cancer ( Allen et al., 2009 ; Li et al., 2010 ). Thus, women with risk factors associated with certain health conditions may want to be more conservative in their alcohol consumption and refrain from drinking at the higher end of the range associated with overall reduced risk of all-cause mortality (i.e., 8–14 drinks/week).

Another group of particular interest is former drinkers—those who drank at some level in the past but were no longer drinking at the WHI baseline assessment. Our results showed that this group had a higher all-cause mortality rate relative to both lifelong abstainers and moderate drinkers. Unfortunately, the WHI data do not provide systematic information about why women stopped drinking and we therefore do not know whether the decision was based on health or social concerns related to alcohol use or to some other, unrelated issue. Whatever may be driving this relationship, our results suggest that it would behoove former drinkers and their care providers to be especially vigilant in managing other risk factors (e.g., smoking, obesity, hypertension) to mitigate any increased risk for early mortality that may be associated with past drinking. In order to manage these issues successfully, population-based alcohol screening may be supplemented by a further determination of whether nondrinkers are lifelong abstainers or former drinkers. This is especially relevant for women Veterans since a sizeable proportion of those reporting no past-year drinking are likely to be former drinkers rather than being lifelong abstainers in light of their significantly lower rates of lifelong abstention relative to non-Veterans. Within VA, clinical alcohol screening can determine whether Veterans report no drinking in the past year, but currently there is no systematic effort to identify those at risk for early mortality based on former drinker status.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The current study has a number of strengths, including the availability of a large sample of Veteran and non-Veteran women who have been followed longitudinally for 16–21 years. Detailed information about alcohol consumption was collected at baseline that allowed us to create groups that were meaningfully anchored to the federal guidelines regarding safe drinking levels for women and to the extant literature. The rich dataset also provided sufficient detail to adjust for many key demographic and other health-risk behaviors that could confound the associations between drinking category and mortality and that have been included in prior evaluations of alcohol consumption levels and mortality.

The study also has several limitations. The WHI excluded women with heavy alcohol or drug use in the past 5 years due to concerns that they would be unable to comply with the study requirements. Thus, as noted above, this may have resulted in some underestimation of the risks associated with being a heavy drinker because the higher end of the consumption spectrum was curtailed. We also lacked diagnostic information regarding SUD and other psychiatric diagnoses as well as mental health and substance abuse treatment history information. There were also a sizeable number of women (approximately 16,000) who did not provide information on their Veteran status. This subset of women is only likely to include about 400 Veterans based on their representation among respondents, and therefore their exclusion from the analyses is unlikely to have much impact on our results. Additionally, despite the rich set of covariates included in our models, there may have been residual confounding by unmeasured factors. In the last few years of follow-up, a proportion of deaths were identified via direct reporting of family, friends, or personal physician. This direct reporting might have resulted in an underreporting of Veterans’ deaths since these women were less likely to be in a marriage-like relationship at baseline.

We also chose to focus solely on reports of drinking at baseline and did not incorporate later available drinking data or examine the relationship between drinking trajectories over time and mortality risk. This could have under- (or over-) estimated the risks associated with various alcohol consumption groups, particularly for former drinkers, as it is possible that women who were drinking at baseline later became former drinkers. Although future research on drinking trajectories and mortality risk within the WHI would help address this issue, data from another longitudinal study of women over the age of 50 found that relatively few (approximately 11%) significantly increased or decreased their drinking levels over a 10-year period ( Bobo & Greek, 2011 ). We also did not differentiate between types of alcoholic beverages consumed (i.e., beer, wine [red vs. other], spirits), which may have obscured protective or harmful effects associated with particular type of alcohol consumed ( Di Minno et al., 2011 ). Additionally, because the data were unavailable, we did not take into account the amount of drinking per occasion. Weekly amounts can mask binge drinking, which has been found to be associated with higher mortality rates ( Breslow & Graubard, 2008 ). Because of this limitation, we were unable to evaluate whether consuming one alcoholic beverage per day conferred any protective effects for mortality, as has been found by other investigators ( O’Keefe, Bhatti, Bajwa, DiNicolantonio, & Lavie, 2014 ).

Conclusions

These study findings help begin to fill important gaps in the literature pertaining to Veteran women, alcohol consumption, and mortality. We were able to explore these relationships in the context of a large, longitudinal sample that includes both Veterans and non-Veterans. This study also lends further credence to the robust literature indicating that alcohol consumption may be associated with both increased longevity and increased risk of early mortality, depending on the amount consumed per week and whether one is a lifelong abstainer or a former drinker. In addition, results indicated that women Veterans were less likely than non-Veterans to be lifelong abstainers and that women Veterans who were former drinkers and moderate drinkers had elevated mortality rates compared to non-Veteran women in the same drinking categories, indicating the need to examine potential factors contributing to this disparity. Finally, we did not find appreciable differences in the relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality by Veteran status in fully adjusted models. Thus, Veteran status does not appear to modify the relationship between alcohol consumption levels and mortality. These results suggest that healthcare providers may counsel Veteran and non-Veteran women in similar ways regarding safe and less safe levels of alcohol consumption. We further recommend that providers treating women who are former drinkers and moderately heavy drinkers be particularly thorough in their clinical assessments and healthcare delivery to optimally safeguard these women’s health and longevity.

Funding

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201 100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System. The research reported here was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service FOP14-439 and the VA Office of Women’s Health. The contents herein do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Ainsworth B. E. Haskell W. L. Leon A. S. Jacobs D. R. Montoye H. J. Sallis J. F. , & Paffenbarger R. S . ( 1993. ). Compendium of physical activities: Classification of energy costs of human physical activities . Medicine Science in Sports Exercise , 25 , 71 – 80 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen N. E. Beral V. Casabonne D. Kan S. W. Reeves G. K. Brown A. , & Green J . ( 2009. ). Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women . Journal of the National Cancer Institute , 101 , 296 – 305 . doi :10.1093/jnci/djn514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. L. Manson J. Wallace R. Lund B. Hall D. Davis S. , … Prentice R. L . ( 2003. ). Implementation of the Women’s Health Initiative study design . Annals of Epidemiology , 13 , S5 – S17 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoia M. L. Triche E. W. Michaud D. S. Baylin A. Hogan J. W. Neuhouser M. L. , … Eaton C. B . ( 2013. ). Long-term alcohol and caffeine intake and risk of sudden cardiac death in women . American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 97 , 1356 – 1363 . doi :10.3945/ajcn.112.044248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo J. K. , & Greek A. A . ( 2011. ). Increasing and decreasing alcohol use trajectories among older women in the U.S. across a 10-year interval . International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 8 , 3263 – 3276 . doi :10.3390/ijerph8083263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R. A. , & Graubard B. I . ( 2008. ). Prospective study of alcohol consumption in the United States: Quantity, frequency, and cause-specific mortality . Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research , 32 , 513 – 521 . doi :10.1093/aje/kwr210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control . (n.d.). Retrieved January 5, 2015 , from http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm

- Delaney K. E. Lee A. K. Lapham G. T. Rubinsky A. D. Chavez L. J. , & Bradley K. A . ( 2014. ). Inconsistencies between alcohol screening results based on AUDIT-C scores and reported drinking on the AUDIT-C questions: Prevalence in two US national samples . Addiction Science & Clinical Practice , 9 , 1 – 9 . doi :10.1186/1940-0640-9-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Castelnuovo A. Costanzo S. Bagnardi V. Donati M. B. Iacoviello L. , & de Gaetano G . ( 2006. ). Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: An updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies . Archives of Internal Medicine , 166 , 2437 – 2445 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Minno M. N. Franchini M. Russolillo A. Lupoli R. Iervolino S. , & Di Minno G . ( 2011. ). Alcohol dosing and the heart: updating clinical evidence . Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis , 37 , 875 – 884 . doi :10.1055/s-0031-1297366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D. E. Yi H. , & Hiller-Sturmhofel S . ( 2006. ). An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders . Alcohol Health & Research , 29 , 162 – 171 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg M. S. Chang Y. Kraemer K. L. Robinson J. G. Adams-Campbell L. L. , & Kuller L. L . ( 2009. ). Alcohol consumption, hypertension, and total mortality among women . American Journal of Hypertension , 22 , 1212 – 1218 . doi :10.1038/ajh.2009.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs C. S. Stampfer M. J. Colditz G. A. Giovannucci E. L. Manson J. E. Kawachi I. , … Rosner B . ( 1995. ). Alcohol consumption and mortality among women . New England Journal of Medicine , 332 , 1245 – 1250 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia L. Qi L. Singh K. Kosoy R. Nassir R. Fijalkowski N. , … Seldin M. F . ( 2014. ). Relationship between glaucoma and admixture in postmenopausal African American women . Ethnicity & Disease , 24 , 399 – 405 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossbard J. R. Lehavot K. Hoerster K. D. Jakupcak M. Seal K. H. , & Simpson T. L . ( 2013. ). Relationships among veteran status, gender, and key health indicators in a national young adult sample . Psychiatric Services , 64 , 547 – 553 . doi :10.1176/appi.ps.003002012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. H. S. Bradley K. A. Bowe T. Henderson P. , & Moos R . ( 2010. ). Associations between AUDIT-C and mortality vary by age and sex . Population Health Management , 13 , 263 – 268 . doi :10.1089/pop.2009.0060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggatt K. J. Jamison A. L. Lehavot K. Cucciare M. A. Timko C. , & Simpson T. L . ( 2015. ). Substance misuse, abuse, and dependence in women veterans: A systematic review of the literature . Epidemiologic Reviews , 37 , 23 – 37 . doi :10.1093/epirev/mxu010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen L. Hannaford P. C. Lee A. J. Elliott A. M. , & Fielding S . ( 2010. ). Impact of lifestyle in middle-aged women on mortality: Evidence from the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study . British Journal of General Practice , 60 , 563 – 569 . doi :10.3399/bjgp10X515052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatsky A. L. , & Udaltsova N . ( 2007. ). Alcohol drinking and total mortality risk . Annals of Epidemiology , 17 , S63 – S67 . doi :10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.014 [Google Scholar]

- Knott C. S. Coombs N. Stamatakis E. , & Biddulph J. P . ( 2015. ). All cause mortality and the case for age specific alcohol consumption guidelines: Pooled analyses of up to 10 populations based cohorts . The British Medical Journal , 350 , 1 – 13 . doi :10.1136/bmj.h384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo J. Henderson M. Desai M. Wactawski-Wende J. Stefanick M. , & Tang J . ( 2014. ). Alcohol consumption and risk of melanoma and non-melanoma . Cancer Causes Control , 25 , 1 – 10 . doi :10.1007/s10552-013-0280-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer R. D. White E. Lewis C. E. Kotchen J. M. Hendrix S. L. , & Trevisan M . ( 2003. ). The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study: Baseline characteristics of participants and reliability of baseline measures . Annals of Epidemiology , 13 , S107 – S121 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K. Hoerster K. D. Nelson K. M. Jakupcak M. , & Simpson T. L . ( 2012. ). Health indicators for military, veteran, and civilian women . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 42 , 473 – 480 . doi :10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K., Katon J. G., Williams E. C., Nelson K. M., Gardella C. M., Reiber G. E., Simpson T. L . ( 2014. ). Sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted infections in a nationally representative sample of women veterans and nonveterans . Journal of Women’s Health , 23 , 246 – 252 . doi :10.1089/jwh.2013.4327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. I. Chlebowski R. T. Freiberg M. Johnson K. C. Kuller K. Lane D. , … Prentice R . ( 2010. ). Alcohol consumption and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer by subtype: The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study . Journal of the National Cancer Institute , 102 , 1422 – 1431 . doi :10.1093/jnci/djq316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y. McGee D. L. Cao G. , & Cooper R. S . ( 2000. ). Alcohol intake and mortality: Findings from the National Health Interview surveys (1988–1990) . American Journal of Epidemiology , 151 , 651 – 659 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul K. A. Ameida O. P. Hankey G. J. Jamrozik K. Byles J. E. , & Flicker L . ( 2010. ). Alcohol use and mortality in older men and women . Addiction Research Report , 105 , 1391 – 1400 . doi :10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J. H. Bhatti S. K. Bajwa A. DiNicolantonio J. J. , & Lavie C. J . ( 2014. ). Alcohol and cardiovascular health: The dose makes the poison…or the remedy . Mayo Clinic Proceedings , 89 , 382 – 393 . doi :10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson R. E. Kristal A. R. Tinker L. F. Carter R. A. Bolton M. P. , & Agurs-Collins T . ( 1999. ). Measurement characteristics of the Women’s Health Initiative Food Frequency Questionnaire . Annals of Epidemiology , 9 , 178 – 187 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J. Gmel G. Sempos C. T. , & Trevisan M . ( 2003. ). Alcohol–related morbidity and mortality . Retrieved January 5, 2015 , from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh27-1/39-51.htm

- Reiber G. E. , & LaCroix A . (forthcoming). Older Women Veterans and the Women’s Health Initiative. Editorial 1 Special Supplement . The Gerontologist . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M. Gual A. , & Rehm J . ( 2013. ). Reduction of alcohol consumption and subsequent mortality in alcohol use disorders: Systematic review and meta-analyses . Journal of Clinical Psychiatry , 74 , 1181 – 1189 . doi :10.4088/JCP.13r08379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T. E. , & Crimmins E . ( 2001. ). Social environment effects on health and aging . Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 954 , 88 – 117 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw B. A. , & Agahi N . ( 2012. ). A prospective cohort study of health behavior profiles after age 50 and mortality risk . Biomedical Central Public Health , 12 , 1 – 10 . doi :10.1186/1471-2458-12-803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau T. M. Grambsch P. M. , & Fleming T. R . ( 1990. ). Martingale-based residuals for survival models . Biometrika , 77 , 147 – 160 . [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . ( 1988. ). Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health. DHHS (PHS) Publication No. 88-50210 .

- Valanis B. G. Bowen D. J. Bassford T. Whitlock E. Charney P. , & Carter R. A . ( 2000. ). Sexual orientation and health: Comparisons in the women’s health initiative sample . Archives of Family Medicine , 9 , 843 – 853 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Xue H. Wang Q. Hao Y. Li D. Gu D. , & Huang J . ( 2014. ). Effect of drinking on all-cause mortality in women compared with men: A meta-analysis . Journal of Women’s Health , 23 , 373 – 381 . doi :10.1089/jwh.2013.4414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitlauf J. C. Lacroix A. Z. Bird C. E. Woods N. F. Washington D. L. Katon J. G. , … Stefanick M. L . ( 2015. ). Prospective analysis of health and mortality risk in veteran and non-veteran participants in the Women’s Health Initiative . Women’s Health Issues , 25 , 648 – 656 . doi :10.1016/j.whi.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Women’s Health Initiative Study Group . ( 1998. ). Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study . Control Clinical Trials , 19 , 61 – 109 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]