Abstract

Objectives: Invasive mold infections associated with Aspergillus species are a significant cause of mortality in immunocompromised patients. The most frequently occurring aetiological pathogens are members of the Aspergillus section Fumigati followed by members of the section Terrei. The frequency of Aspergillus terreus and related (cryptic) species in clinical specimens, as well as the percentage of azole-resistant strains remains to be studied.

Methods: A global set (n = 498) of A. terreus and phenotypically related isolates was molecularly identified (beta-tubulin), tested for antifungal susceptibility against posaconazole, voriconazole, and itraconazole, and resistant phenotypes were correlated with point mutations in the cyp51A gene.

Results: The majority of isolates was identified as A. terreus (86.8%), followed by A. citrinoterreus (8.4%), A. hortai (2.6%), A. alabamensis (1.6%), A. neoafricanus (0.2%), and A. floccosus (0.2%). One isolate failed to match a known Aspergillus sp., but was found most closely related to A. alabamensis. According to EUCAST clinical breakpoints azole resistance was detected in 5.4% of all tested isolates, 6.2% of A. terreus sensu stricto (s.s.) were posaconazole-resistant. Posaconazole resistance differed geographically and ranged from 0% in the Czech Republic, Greece, and Turkey to 13.7% in Germany. In contrast, azole resistance among cryptic species was rare 2 out of 66 isolates and was observed only in one A. citrinoterreus and one A. alabamensis isolate. The most affected amino acid position of the Cyp51A gene correlating with the posaconazole resistant phenotype was M217, which was found in the variation M217T and M217V.

Conclusions: Aspergillus terreus was most prevalent, followed by A. citrinoterreus. Posaconazole was the most potent drug against A. terreus, but 5.4% of A. terreus sensu stricto showed resistance against this azole. In Austria, Germany, and the United Kingdom posaconazole-resistance in all A. terreus isolates was higher than 10%, resistance against voriconazole was rare and absent for itraconazole.

Keywords: cryptic species, Aspergillus section Terrei, susceptibility profiles, azoles, Cyp51A alterations

Introduction

In the last decade, the taxonomy and nomenclature of the previously morphologically defined genus Aspergillus changed, mainly due to comprehensive molecular phylogenetic studies and the introduction of the single name nomenclature (Samson et al., 2011, 2014; Alastruey-Izquierdo et al., 2013). With the introduction of molecular identification methods morphologically similar species were split into several cryptic species (Balajee et al., 2009a,b; Samson et al., 2011; Gautier et al., 2014). Samson et al. (2011) recognized 13 species in section Terrei: A. terreus sensu stricto (s.s.), A. alabamensis, A. allahabadii, A. ambiguus, A. aureoterreus, A. carneus, A. floccosus, A. hortai, A. microcysticus, A. neoafricanus, A. neoindicus, A. niveus, and A. pseudoterreus. In 2015, Guinea et al. (2015) described A. citrinoterreus as a new species of the section Terrei and subsequently A. bicephalus and A. iranicus were introduced (Arzanlou et al., 2016; Crous et al., 2016), resulting in a total of 16 accepted species.

Aspergillus terreus s.s., an important cause of fungal infections in immunocompromised patients, is reported as second or third most common pathogen of invasive aspergillosis (Baddley et al., 2003; Lass-Flörl et al., 2005; Blum et al., 2008). Treatment of infections caused by A. terreus s.s. and other section Terrei species (Walsh et al., 2003; Risslegger et al., 2017) may be difficult because of intrinsic amphotericin B resistance (Sutton et al., 1999; Escribano et al., 2012; Hachem et al., 2014; Risslegger et al., 2017). In addition, the emergence of A. terreus sensu lato (s.l.) isolates with reduced azole-susceptibility was reported (Arendrup et al., 2012; Won et al., 2017). Azole resistance in A. terreus s.s. and A. fumigatus is associated with mutations and alterations of the lanosterol-14-α steroldemethylase gene (Cyp51A), a key protein in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (Chowdhary et al., 2015, 2017). However, aside from mutations in the primary target gene, also other less known mechanisms (e.g., efflux pumps, overexpression of cyp51) were found to be involved in azole resistance (Arendrup, 2014; Rivero-Menendez et al., 2016).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the frequency of A. terreus s.s. and phenotypically similar (cryptic) species in a global set of clinical isolates and to screen for the presence of azole resistance.

Materials and methods

Fungal isolates

During an international A. terreus survey (Risslegger et al., 2017) various A. terreus sensu lato (s.l.) isolates were sent to and collected at the Medical University of Innsbruck by members of the ISHAM-ECMM-EFISG TerrNet Study group (www.isham.org/working-groups/aspergillus-terreus). Isolates were from Europe (n = 390), Middle East (n = 70), South America (n = 10), North America (n = 7), and South Asia (n = 19). A total of 498 strains, including isolates collected in Innsbruck within the last years, were analyzed (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1), 495 were of clinical and 3 of environmental origin. For two isolates, the source is unknown. Isolates were cultured on Sabouraud's agar (Becton Dickinson, France), incubated at 37°C and stored in Sabouraud's broth with glycerin at −20°C.

Antifungal susceptibility testing

Susceptibility to itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole was determined by using reference broth microdilution according to EUCAST (www.EUCAST.org) and ETest® (bioMérieux, France). ETest® MICs were rounded to the next higher EUCAST concentrations and isolates displaying high MICs (≥0.25 mg/L for posaconazole, ≥2.0 mg/L for each, voriconazole and itraconazole) with ETest® were evaluated according to EUCAST. MIC50 and MIC90 were calculated for all studied section Terrei strains and each individual species. EUCAST clinical breakpoints (CBP) for Aspergillus fumigatus (see Table 3) were applied for wild typ and non-wildtyp categorization, as CBP for Aspergillus terreus are not available.

Molecular identification

Genomic DNA was extracted by a method using CTAB (Lackner et al., 2012), and partial β-tubulin gene was amplified using bt2a/bt2b as previously described (Balajee et al., 2009a; Kathuria et al., 2015). KAPA2G Robust HotStart ReadyMix PCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems, USA) was used as master mix and PCR products were cleaned with ExoSAP-IT. For sequencing the BigDye XTerminator purification kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used. Sequencing was performed with the 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA) and data were analyzed with Bionumerics 6.6. Software (Applied Maths, Belgium). Generated sequences were compared with an in-house database of the Westerdijk Institute containing all available Aspergillus reference sequences.

Sequencing of lanosterol 14-α sterol demethylase gene (cyp51A)

Azole-resistant isolates (Table 3) and a control set of susceptible isolates (Supplementary Table S2) underwent Cyp51A sequencing. Cyp51A genes were amplified by PCR, using KAPA2G Robust HotStart ReadyMix PCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems, USA) and in-house designed primers described by Arendrup et al. (2012). In short, PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min 30 s, and a final elongation step of 72°C for 10 min. Primers used for Cyp51A sequencing are provided in Supplementary Table S3. PCR products were cleaned with ExoSAP-IT and for sequencing the BigDye XTerminator purification kit was used. Sequencing was performed with the 3500 Genetic Analyzer and data were analyzed with Bionumerics 6.6. Software and Geneious 8 (Biomatters Limited).

Results and discussion

Epidemiology of cryptic species

Reports on cryptic species within the genus Aspergillus are on the rise (Balajee et al., 2009b; Alastruey-Izquierdo et al., 2013; Negri et al., 2014; Masih et al., 2016) and display variabilities in antifungal susceptibility (Risslegger et al., 2017). Negri et al. (2014) observed an increase of cryptic Aspergillus species causing fungal infections, and others calculated a prevalence of 10–15% of cryptic Aspergillus species in clinical samples (Balajee et al., 2009b; Alastruey-Izquierdo et al., 2013).

The present study analyzed a large number of isolates (n = 498) collected from Europe, Middle East, South America, North America, and South Asia (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S2) and identified A. terreus (n = 432), A. citrinoterreus (n = 42), A. alabamensis (n = 8), A. hortai (n = 13), A. floccosus (n = 1), and A. neoafricanus (n = 1). As previously reported (Risslegger et al., 2017) one isolate failed to be associated with any existing species, but clustered most closely to A. alabamensis (Supplementary Figure S1).

Our study showed limitations due to the unknown source and date of some clinical isolates. A differentiation between isolates from superficial and deep seeded infections was not made, therefore, source-variable resistance rates cannot be excluded. Number of studied isolates varied per country and might also introduce a bias to resistance rates.

Aspergillus terreus s.s. was the most prevalent species (86.8%), followed by A. citrinoterreus (8.4%), A. hortai (2.6%), and A. alabamensis (1.6%). This is in agreement with other authors (Balajee et al., 2009a; Neal et al., 2011; Escribano et al., 2012; Kathuria et al., 2015) showing that A. terreus s.s. is the most common species of section Terrei in clinical and environmental samples. In addition, we detected A. floccosus and A. neoafricanus. We did not identify A. allahabadii, A. ambiguus, A. aureoterreus, A. bicephalus, A. carneus, A. iranicus, A. microcysticus, A. neoindicus, A. niveus, and A. pseudoterreus. The reason for this might be that these species are less common in clinical samples and the environment. Our species distribution is in line with Kathuria et al. (2015), who reported for the first time a probable invasive aspergillosis and aspergilloma case due to A. hortai, which was found to occur in a prevalance of 1.4% of all section Terrei isolates. A multicenter study by Balajee et al. (2009a) observed a high frequency (33% of all clinical A. terreus s.l. isolates were A. alabamensis) of A. alabamensis. Other studies (Neal et al., 2011; Gautier et al., 2014; Risslegger et al., 2017) reported a lower prevalence of A. alabamensis isolates (up to 4.3%).

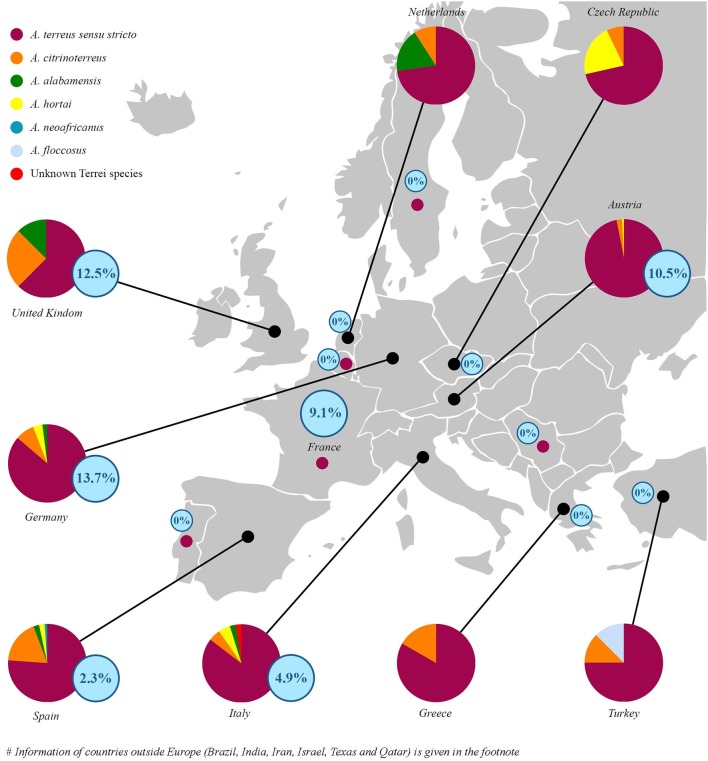

Little is known about the geographical distribution of cryptic species of section Terrei in clinical specimens. A. terreus s.s. was exclusively found in France, Portugal, Serbia, India, and Sweden (Supplementary Table S1). Spain, Italy, Texas and Germany showed highest species diversity (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). In Spain, the prevalent cryptic species were A. citrinoterreus (18.2%), A. alabamensis (2.3%), A. hortai (2.3%), and A. neoafricanus (1.1%), in Italy A. citrinoterreus and A. hortai (4.9%), together with one A. alabamensis (2.4%) and one unknown Terrei species (2.4%). In Germany A. citrinoterreus (7.8%) was followed by A. hortai (3.9%), and A. alabamensis (2.0%). In Texas 80.0% were A. terreus s.s. followed by 10% A. alabamensis and 10.0% A. hortai. Percentage of A. citrinoterreus was highest in Iran accounting 36.36% of all isolates (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Epidemiological distribution of species (circles) and relative percentage of posaconazole resistance (according to EUCAST clinical breakpoints, see Table 2) isolates per country (blue numbers in blue circles) in respect to all investigated isolates. In France, Portugal, Serbia, and Sweden all collected isolates were identified as A. terreus sensu stricto (small dots in magenta). Azole-resistance percentage per countries are given in blue circled numbers. Species distribution in non-EU countries were as follows: India 100% A. terreus s.s.; Israel 84.85% A. terreus s.s. 12.12% A. citrinoterreus 3.03% A. hortai; Texas 80% A. terreus s.s. 10% A. alabamensis 10% A. hortai; Qatar: 83.34% A. terreus s.s. 16.66% A. citrinoterreus; Iran 63.64% A. terreus s.s. 36.36% A. citrinoterreus; and Brazil 85.71% A. terreus s.s., 14.29% A. hortai. All isolates from Iran, Israel, India, Brazil, Texas, and Qatar were susceptible to all azoles tested. For detailed information see Table 4.

Azole resistance among studied section Terrei isolates

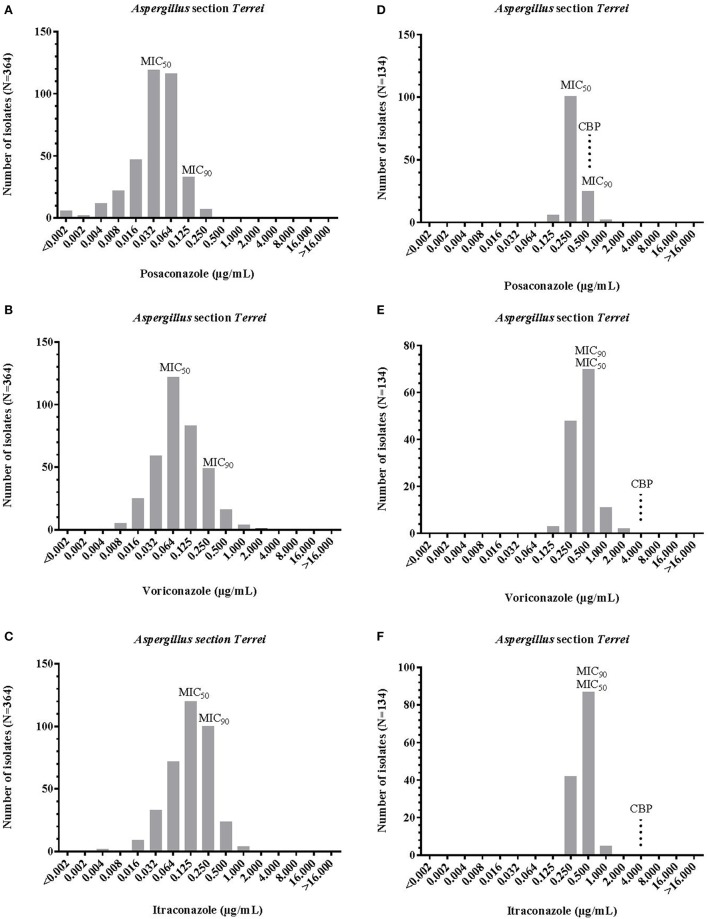

Proposed epidemiological cut off values (ECOFF) values by EUCAST for A. terreus s.s. were 0.25 μg/mL for posaconazole, 2 μg/mL each for voriconazole and itraconazole. Antifungal susceptibility results (MICs) for A. terreus s.s. and cryptic species of the section Terrei are reported in Table 1 and Figure 2. Posaconazole had the lowest MICs for section Terrei isolates (MIC50, 0.032 μg/mL Etest® and 0.250 μg/mL EUCAST), followed by itraconazole (MIC50, 0.125 μg/mL Etest® and 0.500 μg/mL EUCAST), and voriconazole (MIC50, 0.064 μg/mL Etest® and 0.500 μg/mL EUCAST) (Figure 2). Lass-Flörl et al. (2009) observed similar MIC values for posaconazole among clinical isolates of A. terreus s.l. Astvad et al. (2017) tested A. terreus species complex isolates against voriconazole and observed slightly higher MIC ranges of 0.250–8.000 μg/mL.

Table 1.

Clinical breakpoints according to EUCAST1.

| Antifungal agent | MIC S | (mg/L) R |

|---|---|---|

| Posaconazole | ≤0.125 | >0.250 |

| Voriconazole* | ≤1.000 | >2.000 |

| Itraconazole | ≤1.000 | >2.000 |

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration;

CBPs are only available for Aspergillus fumigatus.

Figure 2.

MIC distribution of posaconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazoleintraconazole against Aspergillus section Terrei, obtained by ETest® (A-C) and EUCAST method (D-F). MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MIC50 and MIC90, MIC for 50 and 90% of tested population; CBP EUCAST clinical breakpoint (see Table 2).

No major differences in azole susceptibility profiles for A. terreus s.s. and cryptic species were observed (Table 2). Posaconazole and itraconazole MIC ranges for A. terreus were only slightly higher when compared to cryptic species. As shown in Table 2, MICs50 obtained with Etest® are equal among A. terreus s.s. isolates and cryptic species for posaconazole (0.032 μg/mL) and voriconazole (0.064 μg/mL). No significant differences in MIC90 values were observed among A. terreus s.s. isolates and cryptic species for itraconazole and posaconazole. Voriconazole MICs90 were somewhat higher among cryptic species (0.500 μg/mL) when compared to A. terreus s.s. (0.250 μg/mL). In general, all cryptic A. terreus species were per trend more susceptible to posaconazole and itraconazole than A. terreus s.s. The two most common cryptic species in our study, A. citrinoterreus, and A. alabamensis, showed highest MICs for voriconazole (range: 0.016–2.000 and 0.023–2.000 μg/mL).

Table 2.

Antifungal susceptibility of A. terreus s.s. and related (cryptic) species (Balajee et al., 2009a,b; Samson et al., 2011; Gautier et al., 2014).

| Species | PSC (mg/L) | VRC (mg/L) | ITC (mg/L) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | |

| A. terreus sensu stricto (n = 432) | |||||||||

| Etest® (n = 315) | <0.002–0.500 | 0.032 | 0.125 | 0.008–4.000 | 0.064 | 0.250 | 0.016–2.000 | 0.125 | 0.250 |

| EUCAST (n = 117) | 0.125–0.500 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.125–1.000 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.250–1.000 | 0.500 | 0.500 |

| Cryptic species (n = 66) | |||||||||

| Etest® (n = 55) | <0.002–0.190 | 0.032 | 0.064 | 0.012–4.000 | 0.064 | 0.500 | 0.003–0.380 | 0.064 | 0.250 |

| EUCAST (n = 11) | 0.125–0.250 | NA | NA | 0.125–2.000 | NA | NA | 0.125–0.250 | NA | NA |

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of posaconazole, voriconazole, and itraconazole were obtained by ETest® and EUCAST method.

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MIC50 and MIC90, MIC for 50 and 90% of tested population; ITC, itraconazole; VRC, voriconazole; POS, posaconazole; EUCAST, European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; NA, not applicable; N, number of tested isolates.

According to EUCAST breakpoints 5.4% of all section Terrei isolates are posaconazole resistant. This is a relatively high frequency in comparison to A. fumigatus. A prospective multicenter international surveillance study (van der Linden et al., 2015) showed a prevalence of azole-resistance of 3.2% in A. fumigatus. As shown in Table 3, only mono-azole resistance was observed (posaconazole, MICs ranged from 0.500 to 1.000 μg/mL). Azole resistance was more frequently observed among A. terreus s.s. isolates and was rare among cryptic species. One A. citrinoterreus isolate was resistant against posaconazole (0.500 μg/mL). Posaconazole resistant strains were detected from Germany (13.7%) followed by the United Kingdom (12.5%), Austria (10.5%), France (9.1%), Italy (4.9%), and Spain (2.3%) (Tables 3, 4 and Figure 1). In Turkey, Greece, Serbia, Iran, Israel, India, Brazil, Texas, and Qatar all isolates were susceptible against all azoles tested. However, resistance rates per countries might be influenced by multiple factors such as specimen handling and sampling, and investigated patient cohorts.

Table 3.

Summary of mutations detected in azole-resistant A. terreus and A. citrinoterreus.

| Species | Isolate | EUCAST MIC(mg/L) | Mutation (NA) | Substitution (AA) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VRC | ITC | POS | ||||

| A. terreus sensu stricto | ||||||

| (n = 26) | 51 | 0.500 | 2.000 | 0.500 | M217T | T650C |

| 10 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| 138 | 1.000 | 0.500 | 1.000 | M217V, D344N | A649G, G1030A | |

| 368 | 1.000 | 0.500 | 1.000 | No mutation | ||

| T104 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T112 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | E319G | A956G | |

| T13 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T136 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T15 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.250 | No mutation | ||

| T152 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T153 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | A221V | C662T | |

| T156 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T157 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T159 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T160 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T55 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T59 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T61 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T65 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T67 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T68 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T80 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T9 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.250 | No mutation | ||

| T91 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| T98 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.500 | No mutation | ||

| 16 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 1.000 | No mutation | ||

| A. citrinoterreus | ||||||

| (n = 1) | 150 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 1.000 | I23T, R163H, E202D, Q270R | T69C, G489A, G607C, A810G |

Susceptibily was determined by EUCAST and resistance categorization was based on EUCAST clinical breakpoints (see Table 1).

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; NA, nucleic acid; AA, Amino acid; ITC, itraconazole; VRC, voriconazole; POS, posaconazole: resistant strains based on the EUCAST Antifungal Clinical Breakpoints. EUCAST. European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.

Table 4.

Posaconazole resistance per country relative to (1) all studied isolates and (2) A. terreus s.s. only (also see Figure 1).

| Country | All isolates studied (%) | A. terreus sensu stricto (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 10.5 | 10.9 |

| France | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| Germany | 13.7 | 15.9 |

| Italy | 4.9 | 5.7 |

| Spain | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| UK | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| Iran | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Israel | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| India | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Brazil | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Texas | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Qatar | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Posaconazole showed to be the most effective azole against A. terreus s.s. and related (cryptic) species. However, a high frequency of posaconazole resistant isolates was detected and it was shown that the occurrence of azole resistance differed geographically. Posaconazole resistance among cryptic species was rare when compared to A. terreus s.s.

SNPs in the Cyp51A gene

Mutations at the position M217 were reported to be associated with reduced susceptibility against itraconazole (MICs of 1.0–2.0 μg/mL), voriconazole (MICs of 1.0–4.0 μg/mL), and posaconazole (MICs of 0.25–0.5 μg/mL) (Arendrup et al., 2012), however the substituting amino acids varied from the one found in our study. Our isolates carried the mutations M217T (nucleic acid change T650C) or M217V (nucleic acid change A649G) (Table 3) and were exclusively resistant against posaconazole, when applying the EUCAST clinical breakpoints. Strains carrying the point mutation M217I in the study from Arendrup et al. (2012) were isolated from cystic fibrosis patients receiving long-term azole therapy and showed a pan-azole resistant phenotype. Another posaconazole resistant isolate (T153) carried an amino acid substitution at position A221V, a mutation, which was also previously reported by Arendrup et al. (2010), but was not associated with posaconazole resistance. Hence, functional studies in mutant strains are needed to evaluate the role of the mutations M217V, M217I, M217T, and A221V, which are all located in close proximity to the hot spot mutation M220I of A. fumigatus. Understanding the impact of mutations at the position M217 on the protein folding pattern and subsequently on binding capacities of azoles is the key to evaluate its role as azole-resistance markers. Other hotspot mutations, which were linked to acquired azole-resistance in A. fumigatus, are G54, L98, and M220 (Arendrup et al., 2010). None of them were found in our resistant isolates, suggesting different mechanisms of acquired azole-resistance than in A. fumigatus. The role of the other coding mutations within A. terreus s.s. isolates E19G (nucleic acid substitution A956G) and D344N (nucleic acid substitution C662T) remains to be studied. Voriconazole resistant A. citrinoterreus carried the amino acid changes I23T, R163H, E202D, Q270R (Table 3), which need to be analyzed in detail.

Conclusions

Aspergillus terreus s.s. was most prevalent, followed by A. citrinoterreus. Posaconazole was the most potent azole against the investigated isolates and species. Approximately 5% of all tested A. terreus s.s. isolates were resistant against posaconazole in vitro. In Austria, Germany and the UK posaconazole resistance was higher than 10% in all A. terreus s.s. isolates. Resistance against itraconazole and voriconazole was rare.

Author contributions

TZ: manuscript writing, Etest susceptibility testing, data analysis and interpretation, discussion of results, DNA extraction, sequencing; BS: wrote parts of the manuscript (M&M), DNA extraction, sequencing, nucleic acid alignments, and amino acid alignments; LS: EUCAST susceptibility testing, DNA extraction; JH: BLAST comparison of sequences, molecular species identification; BR: culturing of isolates, subcultivation of isolates, morphological identification, data management; CL-F: manuscript writing, discussion of results, clinical background, funding, coordination of the TerrNet study group, isolate recruitment; ML: manuscript writing, data analysis, study design, supervising TZ, BS, and LS; MA, FS-R, AR, AnC, ST-A, MA, SO, DK, AA-I, KL, GL, JM, WB, CF, MD-A, AG, AT, BW, AH, EJ, LK, VA-A, OC, JM, WP, VT, J-JV, LT, RL, ES, P-MR, PH, MR-I, ER, SA-A, ArC, ALC, MF, MM-G, HB, GP, NK, SH, OU, MR, SdlF are members of the EFISG-ISHAM-ECMM TerrNet Study group: providing strains and data.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The handling Editor declared a past co-authorship with several of the authors BS, KL, JM, BW, VA-A, OC, J-JV, P-MR, CL-F, and ML. The handling Editor declared a shared affiliation, and co-authorship, with one of the authors WB.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katharina Rosam, Sandra Leitner, and Caroline Hörtnagl for technical assistance. The authors also thank the EFISG-ISHAM-ECMM TerrNet Study group for providing strains and data.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by ECMM, ISHAM, and EFISG and in part by an unrestricted research grant through the Investigator Initiated Studies Program of Astellas, MSD, and Pfizer. This study was fundet by the Christian Doppler Laboratory for invasive fungal infections.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00516/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Mellado E., Peláez T., Pemán J., Zapico S., Alvarez M., et al. (2013). Population-based survey of filamentous fungi and antifungal resistance in Spain (FILPOP Study). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3380–3387. 10.1128/AAC.00383-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendrup M. C. (2014). Update on antifungal resistance in Aspergillus and Candida. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, 42–48. 10.1111/1469-0691.12513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendrup M. C., Jensen R. H., Grif K., Skov M., Pressler T., Johansen H. K., et al. (2012). In vivo emergence of Aspergillus terreus with reduced azole susceptibility and a Cyp51a M217I Alteration. J. Infect. Dis. 206, 981–985. 10.1093/infdis/jis442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendrup M. C., Mavridou E., Mortensen K. L., Snelders E., Frimodt-Møller N., Khan H. (2010). Development of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy associated with change in virulence. PLoS ONE 5:e10080. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arzanlou M., Samadi R., Frisvad J. C., Houbraken J., Ghosta Y. (2016). Two novel Aspergillus species from hypersaline soils of the national park of lake Urmia, Iran. Mycol. Prog. 15, 1081–1092. 10.1007/s11557-016-1230-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astvad K. M. T., Hare R. K., Arendrup M. C. (2017). Evaluation of the in vitro activity of isavuconazole and comparator voriconazole against 2635 contemporary clinical Candida and Aspergillus isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 23, 882–887. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddley J. W., Pappas P. G., Smith A. C., Moser S. A. (2003). Epidemiology of Aspergillus terreus at a University Hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 5525–5529. 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5525-5529.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balajee S. A., Baddley J. W., Peterson S. W., Nickle D., Varga J., Boey A., et al. (2009a). Aspergillus alabamensis, a new clinically relevant species in the section Terrei. Eukaryot. Cell 8, 713–722. 10.1128/EC.00272-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balajee S. A., Kano R., Baddley J. W., Moser S. A., Marr K. A., Alexander B. D., et al. (2009b). Molecular identification of Aspergillus species collected for the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 3138–3141. 10.1128/JCM.01070-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum G., Perkhofer S., Grif K., Mayr A., Kropshofer G., Nachbaur D., et al. (2008). A 1-year Aspergillus terreus surveillance study at the University Hospital of Innsbruck: molecular typing of environmental and clinical isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14, 1146–1151. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02099.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary A., Sharma S., Kathuria F., Hagen F., Meis J. F. (2015). Prevalence and mechanism of triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus in a referral chest hospital in Delhi, India and an update of the situation in Asia. Front. Microbiol. 6:428. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary A., Sharma C., Meis J. F. (2017). Azole-resistant Aspergillosis: epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 216, 436–444. 10.1093/infdis/jix210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous P. W., Wingfield M. J., Burgess T. I., Hardy G. E., Crane C., Barrett S., et al. (2016). Fungal planet description sheets: 469–557. Persoonia 37, 218–403. 10.3767/003158516X694499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escribano P., Peláez T., Recio S., Bouza E., Guinea J. (2012). Characterization of clinical strains of Aspergillus terreus complex: molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility to azoles and amphotericin B. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 24–26. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03714.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier M., Ranque S., Normand A. C., Becker P., Packeu A., Cassagne C., et al. (2014). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry: revolutionizing clinical laboratory diagnosis of mould infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, 1366–1371. 10.1111/1469-0691.12750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinea J., Sandoval-Denis M., Escribano P., Peláez T., Guarro J., Bouza E. (2015). Aspergillus citrinoterreus, a new species of section Terrei isolated from samples of patients with nonhematological predisposing conditions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 611–617. 10.1128/JCM.03088-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachem R., Gomes M. Z., El Helou G., El Zakhem A., Kassis C., Ramos E., et al. (2014). Invasive aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus terreus: an emerging opportunistic infection with poor outcome independent of azole therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 3148–3155. 10.1093/jac/dku241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathuria S., Sharma C., Singh P. K., Agarwal P., Agarwal K., Hagen F., et al. (2015). Molecular epidemiology and in-vitro antifungal susceptibility of Aspergillus terreus species complex isolates in Delhi, India: evidence of genetic diversity by amplified fragment Length polymorphism and microsatellite typing. PLoS ONE 10:e118997. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner M., Najafzadeh M. J., Sun J., Lu Q., Hoog G. S. (2012). Rapid identification of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium strains by using rolling circle amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbial. 78, 126–133. 10.1128/AEM.05280-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass-Flörl C., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Cuenca-Estrella M., Perkhofer S., Rodriguez-Tudela J. L. (2009). In vitro activities of various antifungal drugs against Aspergillus terreus: global assessment using the methodology of the European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 794–795. 10.1128/AAC.00335-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass-Flörl C., Griff K., Mayr A., Petzer A., Gastl G., Bonatti H., et al. (2005). Epidemiology and outcome of infections due to Aspergillus terreus: 10-year single centre experience. Br. J. Haematol. 131, 201–207. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05763.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masih A., Singh P. K., Kathuria S., Agarwal K., Meis J. F., Chowdhary A. (2016). Identification by molecular methods and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry and antifungal susceptibility profiles of clinically significant rare Aspergillus species in a referral chest hospital in Delhi, India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 2354–2364. 10.1128/JCM.00962-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal C. O., Richardson A. O., Hurst S. F., Tortorano A. M., Viviani M. A., Stevens D. A., et al. (2011). Global population structure of Aspergillus terreus inferred by ISSR typing reveals geographical subclustering. BMC Microbiol. 11:203. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri C. E., Goncalves S. S., Xafranski H., Bergamasco M. D., Aquino V. R., Castro P. T., et al. (2014). Cryptic and rare Aspergillus species in Brazil: prevalence in clinical samples and in vitro susceptibility to triazoles. J. Clin. Microb. 52, 3633–3640. 10.1128/JCM.01582-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risslegger B., Zoran T., Lackner M., Aigner M., Sánchez-Reus F., Rezusta A., et al. (2017). A prospective international Aspergillus terreus survey: an EFISG, ISHAM and ECMM joint study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 23, 776.e1–776.e5. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivero-Menendez O., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Mellado E., Cuenca-Estrella M. (2016). Triazole resistance in Aspergillus spp.: a worldwide problem? J. Fungi. 2:21. 10.3390/jof2030021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson R. A., Peterson S. W., Frisvad J. C., Varga J. (2011). New species in Aspergillus section Terrei. Stud. Mycol. 69, 39–55. 10.3114/sim.2011.69.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson R. A., Visagie C. M., Houbraken J., Hong S. B., Hubka V., Klaassen C. H., et al. (2014). Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 78, 141–173. 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton D. A., Sanchie S. E., Revankar S. G., Fothergill A. W., Rinaldi M. G. (1999). In vitro amphotericin B resistance in clinical isolates of Aspergillus terreus, with a head-to-head comparison to voriconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 2343–2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden J. W., Arendrup M. C., Warris A., Lagrou K., Pelloux H., Hauser P. M., et al. (2015). Prospective multicenter international surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21, 1041–1044. 10.3201/eid2106.140717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T. J., Petraitis V., Petraitiene R., Field-Ridley A., Sutton D., Ghannoum M., et al. (2003). Experimental pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus: pathogenesis and treatment of an emerging fungal pathogen resistant to amphotericin B. J. Infect. Dis. 188, 305–319. 10.1086/377210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won E. J., Choi M. J., Shin J. H., Park Y.-J., Byun S. A., Jung J. S., et al. (2017). Diversity of clinical isolates of Aspergillus terreus in antifungal susceptibilities, genotypes and virulence in Galleria mellonella model: comparison between respiratory and ear isolates. PLoS ONE 12:e0186086. 10.1371/journal.pone.0186086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.