Abstract

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) (including renal pelvis, ureter and urethra) is one of the most common urogenital cancers and the fourth most frequent cancer in men in the USA. In Norway, the incidence of BC has increased over the last decades. The age-standardised incidence rates per 100 000 for 2011-2015 were 53.7 in men and 16.5 in women. Compared to the 5-year period 2006–2010, the percentage increase in incidence was 6.1% in men and 12.3% in women. The recurrence rate of BC is over 50%, the highest recurrence rate of any malignancy. Smoking and occupational exposure to aromatic amines are recognised as the major risk factors. Recently, low-serum level of 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) and obesity have been suggested to increase the BC risk, and leptin, which is important in weight regulation, may be involved in bladder carcinogenesis. More knowledge on potential risk factors for BC is necessary for planning and implementing primary prevention measures.

Methods and analyses

Cohort and nested case–control studies will be carried out using the population-based Janus Serum Bank Cohort consisting of prediagnostic sera, clinical measurement data (body height and weight, body surface area and weight change over time, blood pressure, cholesterol and triglycerides) and self-reported information on lifestyle factors (smoking, physical activity). Participants were followed from cohort inclusion (1972–2003) through 2014. The cohort will be linked to the Cancer Registry of Norway (cancer data), the National Cause of Death Registry (date and cause of death), National Population Registry (vital status) and Statistic Norway (education and occupation). Serum samples will be analysed for 25(OH)D, vitamin D binding protein, leptin, albumin, calcium and parathyroid hormone. Cox regression and conditional logistic regression models and mediation analysis will be used to estimate association between the exposures and BC.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and is funded by the Norwegian Cancer Society. Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals, at scientific conferences and through press releases.

Keywords: bladder cancer, biobank, vitamin D, obesity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of a large sample set of more than 2300 incident bladder cancer (BC) cases.

Prediagnostic serum samples assure the temporality of the relationship between exposure and BC, limiting the possibility of reverse causality.

Use of unique personal identification number for linkages between multiple data sources to establish a virtually complete study file and complete ascertainment of follow-up.

Reviewing and characterising T-stage for all BC.

Lack of treatment data.

Introduction

Rationale and evidence gaps

Urinary bladder cancer (BC) (including renal pelvis, ureter and urethra) is the most common urogenital cancer after prostate cancer and is the fourth most frequent cancer in men in the USA.1 BC has over a 50% recurrence rate, the highest of any malignancy and is one of the most expensive cancers to treat on a per-patient basis.2 In Norway, the incidence of cancer of the bladder has been increasing over the last decades. In 2015, the age-standardised incidence rates were 53.7 and 16.5 in Norwegian men and women, respectively. Compared with the 5-year period 2006–2010, the increase in incidence has been 6.1% in men and 12.3% in women. Up to 50% of all BC cases have been ascribed to smoking,3 and 5%‒25% of the cases have been attributable to occupational exposures4; still, the aetiology of up to 45% of BC remains unexplained. Low-serum level of 25 hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) and obesity have been suggested to increase BC risk, and the hormone leptin, which is important in weight regulation, may be involved in its carcinogenetic process.5 6

25-Hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) is converted to its active hormonal form, 1–25-dihydroxy vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), by 1-α-hydroxylase, which is present in most tissues in the body.7 Parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcium level are important factors as they affect the enzymatic conversion from 25(OH)D to active 1,25-(OH)D3 in the kidney and may be involved in non-classical synthesis. Measurement of circulating 25(OH)D is considered the gold standard measurement of vitamin D status as it integrates vitamin D exposure from oral intake from diet or supplements, as well as from exposure to ultraviolet radiation.8 9 Despite being the gold standard, total circulating 25(OH)D may not be the best measure of 25(OH)D exposure for all tumours. The ‘free hormone hypothesis’ suggests that only unbound, free hormones can have biological effects on target tissues.10 To date, few studies have examined the role of vitamin D binding protein (DBP) also known as group-specific component or Gc-globulin, in the association between 25(OH)D and various cancer processes. DBP transports both 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D in circulation. This protein carries 88% of 25(OH)D and 85% of 1,25(OH)2D; an additional 12% of 25(OH)D and 15% of 1,25(OH)2D circulate bound to albumin. Clinical laboratory assays of circulating 25(OH)D that are currently in use measure total 25(OH)D without differentiating between the bound and free forms. Thus, it remains unclear whether total or free 25(OH)D is more biologically relevant with respect to risk of BC. Two previous studies have examined free, in addition to total 25(OH)D, in relation to risk of BC. One found an inverse association between total 25(OH)D and bladder cancer that appeared to be restricted to participants with low DBP, suggesting that free 25(OH)D might be more strongly associated with risk of bladder cancer than total 25(OH)D.11 The other study found no association between 25(OH)D overall or at any level of DBP concentration.12

Body mass index (BMI; weight/height) is a reliable indicator of body fatness and can be categorised as underweight (<18.5), healthy weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9) and obese (>30). The prevalence of obesity in Norway has risen steeply the last decades. In the 1970s, about 15% of men and women were overweight (www.fhi.no/), while in 2013, the proportions were 58.4% and 47.3%, respectively.13 Two meta-analyses, including 1514 and 1115 cohort studies conclude that obesity significantly increases the risk of BC. Leptin, a hormone involved in weight regulation,16 may be involved in this potential association. High leptin levels have been shown to impact development of several forms of cancer.17 A study of Yuan et al6 shows that leptin receptors are aberrantly expressed in BC tissue and a high leptin level has been associated with BC carcinogenesis.5 6

Low 25(OH)D levels are more frequent in obese persons, suggesting that 25(OH)D deficiency is associated with obesity and vice versa. Deficiency of 25(OH)D is suggested to be associated with obesity,18–20 and both low 25(OH)D and obesity are suggested to contribute to development of BC.

Aims and hypotheses

Better-targeted BC primary and tertiary prevention (risk and survival) is warranted. The interplay between 25(OH)D and obesity and their associations with BC risk are poorly understood. We propose a study aiming to examine anthropometric data (BMI, height, weight, body surface area (BSA) and weight change over time) and serum levels of leptin, total and free 25(OH)D, in relation to BC risk and survival by using samples from Janus Serum Bank and associated data from population-based registries and surveys.

We hypothesise that:

(1a) Obesity, BSA and weight change over time are associated with increased BC risk;

(1b) Obesity, BSA and weight change over time are associated with reduced BC survival;

(2a) Low free and total 25(OH)D level and high-serum leptin levels (>4.1 ng/mL) are associated with increased risk of BC;

(2b) Low free and total 25(OH)D level and high-serum leptin levels (>4.1 ng/mL) are associated with reduced BC survival.

Methods and analysis

Study population and data sources

The Janus Serum Bank Cohort

The study will be carried out using the Janus Serum Bank Cohort, a population-based biobank for prospective cancer studies, containing serum samples and questionnaire data from 292 851 Norwegians who participated in one or more of five Norwegian Regional Health Studies in the period 1972–2003. Detailed description of the samples and data included in the Janus Serum Bank Cohort has been published elsewhere.21 22 The quality aspects of long-term stored samples have been of high priority in the Janus Serum Bank, and component stability for a large number of hormones, proteins, metabolites and electrolytes has been investigated,23–25 including both 25(OH)D and leptin.26–29 A unique 11-digit personal identification number (PIN), assigned to all Norwegian residents will be used to link the Janus Cohort with population-based registries and surveys.

Population-based registries and surveys

The Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN) has collected notifications on cancer at a national level since 1953. Cancer reporting is mandatory by law, and reports from various sources ensure high quality and completeness (98.8%).30 The reporting system, based on pathology and cytology reports, clinical records and death certificates, provides information about site, histological type and stage of disease at the time of diagnosis. CRN has been involved in the Janus Serum Bank operation since establishment in the early 1970s and has been responsible for the data handling; in 2004 the serum bank was integrated into the CRN. The following information is available for cancer cases: month and year of diagnosis, tumour site (International Classification of Diseases seventh revision (ICD-7 codes) converted into ICD-10 codes), histology (codes from ICD-Oncology (ICD-O) second and third revision) and clinical stage (local=no metastases, regional=metastasis in regional lymph nodes or surrounding area, distant=distant metastasis). In addition, all BC diagnoses in the Janus cohort will be reviewed and assigned a pathological T-stage, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual eighth edition.31

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health has been responsible for conducting the national health surveys, on which the Janus Serum Bank is partly based. All participants have completed questionnaires for assessment of lifestyle factors (ie, smoking habits, alcohol use), at the time of serum collection. A database has been established, including data from these questionnaires, as well as measured body height and weight, blood pressure, cholesterol and triglycerides.32 33 The Janus Cohort includes participants from five of the health studies: the Oslo Study I (1972–1973), the Norwegian Counties Study (1974–1978, 1977–1983 and 1985–1988), the Age 40 Program—Oslo (1981–1999), the National Age 40 Program (1985–1999) and the Tromsø and Finmark (TROFINN) Health Study (2001–2003). A set of about 50 variables has been harmonised and standardised due to slightly different wording in the questionnaires.22 Available variables include: height (cm), weight (kg), BMI (kg/m2, categorised as 12–18.49, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, ≥30), smoking status (never, former, current), cigarettes per day (1–9, 10–14, ≥15), years of smoking (1–9, 10–29, ≥30), time since smoking cessation (<3 months, 3 months–1 year, 1–5 years, >5 years) and total physical activity (inactive, low, medium, high) based on leisure time activity. Estimated variables include BSA (m2) using the DuBois’ equation (weight0,4253×height 07253×30.007184)20; and weight change calculated by subtracting the 1985–1988 wt measure from the 1974–1978 measure (median time between the weight measurements of 10 years). Weight change will only be possible for a subgroup with repeated measurement of weight.

The Cause of Death Registry has registered death certificates for all deaths in Norway since 1951. Cause of death registration is mandatory by law.

The National Population Registry contains information on vital status (alive, emigrated or dead) of everyone that resides or has resided in Norway.

The Statistics Norway has the responsibility of covering the needs for official statistics on the Norwegian population including individual data on settlements, migration, occupation and level of education.

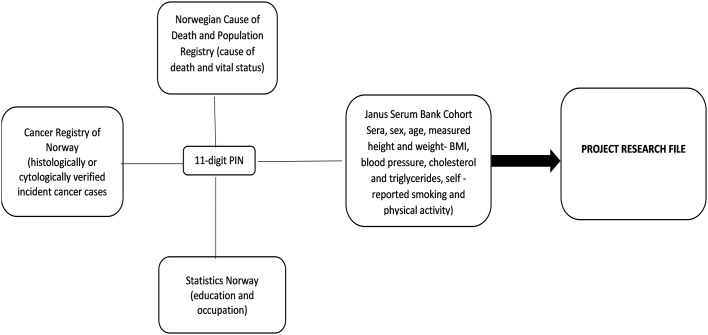

Using the 11-digit PIN, we will link data from four different sources to set up the research file, illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data collection from different sources using PIN. PIN, personal identification number.

Study design

Substudy I: a prospective cohort study

In a prospective cohort study among all individuals in the Janus Serum Bank Cohort (n=292 851) (figure 1), we will explore baseline BMI in relation to bladder cancer risk. Among the included BC cases, we will investigate baseline BMI and BC survival. By 2014, the cohort included 2347 BC cases (ICD-10: C67). BC cases of both muscle invasive and non-invasive urothelial cell carcinoma will be included in the study. Educational level, occupation, age, sex, physical activity, smoking habits, cholesterol, triglycerides and blood pressure will be included in the statistical analyses as confounders.

Substudy II: a nested case–control study

The study will be nested within the prospective cohort described above (study I), including (1) 400 BC cases of high-grade tumours, including muscle invasive (T2–T4) and non-muscle invasive (Ta, T1 and carcinoma in situ) cancer cases and (2) 400 controls alive and without a cancer diagnosis at the time of the BC diagnosis of the cases, matched 1:1 on sex, age (+/-1 year) and date of serum sampling (+/-1 month). Minimum time from blood draw to diagnosis will be 5 years. The serum samples will be analysed for total 25(OH)D, vitamin D binding protein and leptin. As PTH and albumin-adjusted calcium level affect the enzymatic conversion from 25(OH)D to active 1,25-(OH)D3 and might be involved in the non-classical synthesis as well, measurement of these components will be taken into account.

In substudy I, we will investigate the association between BMI and BC, and for substudy II, we will in addition include vitamin D levels. Overall, we will focus on disentangle the relationship of vitamin D, BMI and BC. This will be done in two ways:

By implementing regression models including and interaction effect of vitamin D and BMI on BC;

By testing the hypothesis whether the effect of BMI on BC is mediated by vitamin D using mediation analysis.34

Statistical methods

In the cohort study, Cox regression models will be used to estimate HRs with 95% CI of BC and survival after BC, taking into account stage at diagnosis and BMI and including adjusting for season of blood collection for vitamin D. In the nested case–control study, conditional logistic regression models will be used to estimate the OR with 95% CI.

To find out whether vitamin D acts (totally or partly) as a mediator, modern causal inference theory will be used to estimate different types of effects.34

As we have a number of potential confounding variables, we will use directed acyclic graphs to select variables to include in the statistical models. Confounding variables will be included in the models and tests of interaction effects will be performed when relevant.

The tests will be two sided and p<0.05 will be considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses will be conducted using R package and35 Stata V.14.1 (StataCorp).

Laboratory analyses

The serum samples (aliquots of 400 µL) will be analysed for total 25(OH)D, DBP, leptin, PTH, albumin and calcium. The Hormone Laboratory at Aker hospital, Oslo, Norway will analyse 25(OH)D, DBP, PTH and leptin. The Hormone Laboratory is accredited by the Norwegian Accreditation as a testing laboratory and complies with the General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories (NS-EN ISO/IEC 17025). Albumin and calcium will be analysed at Department of Medical Biochemistry, Oslo University Hospital accredited by the Norwegian Accreditation registration no. TEST 103 that complies with the requirements of the NS-EN ISO 1518. The sample donors, identity and case–control status will be blinded for the laboratory staff. Quality control samples from the biobank will be included in every batch to examine interbatch and intrabatch variability.

Power and sample size

Substudy I

Within the prospective cohort (n=292 851), there are more than 2300 BC cases reported to the cancer registry until the end of follow-up time. Assuming the risk of developing bladder cancer is 1% for the normal weight group and 5% for the obese group,14 one would need a sample size of 586 to have 80% power. Since the sample size here is significantly larger, one can safely determine that the study has adequate statistical power.

Substudy II

In the case–control study nested into the prospective cohort, the statistical power will depend on: (1) proportion of exposure in the population; (2) sample size (cases and controls) and (3) the minimum difference that is possible to detect.

Table 1 shows the smallest detectable OR according to proportion of controls exposed to low vitamin D(25(OH)D and high leptin levels for different sample sizes. The power is 0.80 and a significance level of 0.05 (www.krothman.hostbyet2.com/Episheet.xls). The expected proportions of exposed controls were based on previous studies on serum samples from the Janus Cohort. For 25(OH)D, a study on prostate cancer reported that 4.4% and 30.6% of the controls had 25(OH)D levels below 30 nmol/L and 50 nmol/L, respectively.29 For leptin, a study on colon cancer reported that 20% of the controls had a leptin level of 4.1 ng/mL or higher.27

Table 1.

OR based on proportion of exposed controls and sample size

| Proportion of exposed controls % | Study case:control=1:1 | |||

| Number of cases | ||||

| n=500 | n=400 | n=300 | ||

| 55* | OR | 1.44 | 1.50 | 1.6 |

| 45* | OR | 1.43 | 1.49 | 1.58 |

| 30† | OR | 1.45 | 1.51 | 1.62 |

*Exposure=25(OH)D deficiency (25(OH)D<50 nmol /L).

†Exposure=high-serum leptin levels (>4.1 ng/mL).

Based on results in the table above, we consider 400 matched case-control pairs as a sufficient sample size for the case-control study.

Data analysis plan

The following analyses will be conducted to test our hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: A prospective cohort analysis of prediagnostic BMI and other anthropometric measures in relation to BC risk using the complete Janus Cohort (n=292 851);

Hypothesis 1b: A prospective cohort analysis of prediagnostic BMI and other anthropometric measures in relation to survival after a BC, using all BC cases in the Janus Cohort (n=2650);

Hypothesis 2a: A nested case–control analysis of BC risk according to prediagnostic serum levels of total and free 25(OH)D and leptin in 400 matched case–control pairs;

Hypothesis 2b: A prospective analysis of survival after a BC (n=400) according to prediagnostic serum levels of 25(OH)D and leptin.

Study strengths and limitations

A major strength of the large sample set of more than 2300 incident BC cases. Also, the use of individual PIN for linkages between multiple data sources to establish a virtually complete study file, with exception of data on histopathology, is a strength. The data sources are high-quality population-based registries, with high degree of completeness. The bladder cancer diagnoses are coded according to ICD-O. To get information on staging and control the data quality, all histopathological information will be reviewed and characterised by tumour (T stage). Another strength of this study is that the public health data has been quality assured, structured and harmonised.22 The use of prediagnostic samples assures the proper temporality of the relationship between exposure and BC, limiting the possibility of reverse causality.

Treatment data are of importance when evaluating the survival analyses. These data are missing and will be a limitation of this study

Ethics and dissemination

The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics has approved the study. The different data registries have approved that the use of a deidentified dataset. An identification (ID) key, consisting of the 11-digit PIN and a study-specific ID number, will be stored and governed by a third party unavailable to the research team.

All results will be published in relevant peer-reviewed international scientific journals and presented at conferences, nationally and internationally. Results of importance will be directly communicated to health authorities and to clinicians where the annual national oncology conference ‘Onkologisk forum’ can serve as a platform for knowledge distribution. Results of importance will also be disseminated through press releases and to user groups like the Norwegian Cancer Society. The CRN website is a potential channel to reach patients organisations and the public.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: REG prepared the study. TER, JSS, HHH, HL, BKA, KA, EW and AM contributed to the study design and reviewed and revised the protocol critically for important intellectual content and approved the final versions. REG is the guarantor.

Funding: The research study has been reviewed and granted funding by the Norwegian Cancer Society (no. 182308-2016) and the Cancer Registry of Norway Research Fund.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: The Norwegian Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (no 2016/2233).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svatek RS, Hollenbeck BK, Holmäng S, et al. . The economics of bladder cancer: costs and considerations of caring for this disease. Eur Urol 2014;66:253–62. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman ND, Silverman DT, Hollenbeck AR, et al. . Association between smoking and risk of bladder cancer among men and women. JAMA 2011;306:737–45. 10.1001/jama.2011.1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olfert SM, Felknor SA, Delclos GL. An updated review of the literature: risk factors for bladder cancer with focus on occupational exposures. South Med J 2006;99:1256–63. 10.1097/01.smj.0000247266.10393.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishii N, Wei M, Kakehashi A, et al. . Enhanced urinary bladder, liver and colon carcinogenesis in Zucker diabetic fatty rats in a multiorgan carcinogenesis bioassay: evidence for mechanisms involving activation of PI3K signaling and impairment of p53 on urinary bladder carcinogenesis. J Toxicol Pathol 2011;24:25–36. 10.1293/tox.24.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan SS, Chung YF, Chen HW, et al. . Aberrant expression and possible involvement of the leptin receptor in bladder cancer. Urology 2004;63:408–13. 10.1016/j.urology.2003.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bikle D. Nonclassic actions of vitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:26–34. 10.1210/jc.2008-1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of vitamin D and cancer incidence and mortality: a review (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2005;16:83–95. 10.1007/s10552-004-1661-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holick MF. Vitamin D status: measurement, interpretation, and clinical application. Ann Epidemiol 2009;19:73–8. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pike JW FD, Glorieux FH. Vitamin D. San Diego: Academic Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mondul AM, Weinstein SJ, Virtamo J, et al. . Influence of vitamin D binding protein on the association between circulating vitamin D and risk of bladder cancer. Br J Cancer 2012;107:1589–94. 10.1038/bjc.2012.417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mondul AM, Weinstein SJ, Horst RL, et al. . Serum vitamin D and risk of bladder cancer in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:1222–5. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. . Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:766–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun JW, Zhao LG, Yang Y, et al. . Obesity and risk of bladder cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119313 10.1371/journal.pone.0119313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin Q, Xu X, Wang X, et al. . Obesity and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013;14:3117–21. 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.5.3117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klok MD, Jakobsdottir S, Drent ML. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obes Rev 2007;8:21–34. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garofalo C, Surmacz E. Leptin and cancer. J Cell Physiol 2006;207:12–22. 10.1002/jcp.20472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foss YJ. Vitamin D deficiency is the cause of common obesity. Med Hypotheses 2009;72:314–21. 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007;357:266–81. 10.1056/NEJMra070553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mai XM, Chen Y, Camargo CA, et al. . Cross-sectional and prospective cohort study of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and obesity in adults: the HUNT study. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175:1029–36. 10.1093/aje/kwr456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langseth H, Gislefoss RE, Martinsen JI, et al. . Cohort profile: the janus serum bank cohort in Norway. Int J Epidemiol 2016;95:dyw027 10.1093/ije/dyw027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hjerkind KV, Gislefoss RE, Tretli S, et al. . Cohort profile update: the Janus Serum Bank Cohort in Norway. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:dyw302 10.1093/ije/dyw302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gislefoss RE, Grimsrud TK, Mørkrid L. Long-term stability of serum components in the Janus Serum Bank. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2008;68:402–9. 10.1080/00365510701809235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gislefoss RE, Grimsrud TK, Mørkrid L. Stability of selected serum proteins after long-term storage in the Janus Serum Bank. Clin Chem Lab Med 2009;47:596–603. 10.1515/CCLM.2009.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gislefoss RE, Grimsrud TK, Mørkrid L. Stability of selected serum hormones and lipids after long-term storage in the Janus Serum Bank. Clin Biochem 2015;48:364–9. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stattin P, Kaaks R, Johansson R, et al. . Plasma leptin is not associated with prostate cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003;12:474–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stattin P, Lukanova A, Biessy C, et al. . Obesity and colon cancer: does leptin provide a link? Int J Cancer 2004;109:149–52. 10.1002/ijc.11668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tretli S, Schwartz GG, Torjesen PA, et al. . Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and survival in Norwegian patients with cancer of breast, colon, lung, and lymphoma: a population-based study. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23:363–70. 10.1007/s10552-011-9885-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer HE, Robsahm TE, Bjørge T, et al. . Vitamin D, season, and risk of prostate cancer: a nested case-control study within Norwegian health studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:147–54. 10.3945/ajcn.112.039222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen IK, Småstuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. . Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1218–31. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al. . AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th edn New York: Springer International Publishing, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjartveit K, Foss OP, Gjervig T, et al. . The cardiovascular disease study in Norwegian counties. Background and organization. Acta Med Scand Suppl 1979;634:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.L-L PG. Arven fra Statens skjermbildefotografering (SSF)/Statens helseundersøkelser (SHUS) en introduksjon til databanken. Tidsskr Norsk Forening for Epidemiol 2003;13:14 10.5324/nje.v13i1.304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods 2010;15:309–34. 10.1037/a0020761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, et al. . Mediation : R package for causal mediation analysis. J Stat Softw 2014;59:1–34. 10.18637/jss.v059.i0526917999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.