Abstract

The naturally occurring olive phenolics tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG), and oleuropein are known to have antioxidant, antitumor, and antibacterial properties. In the current study, we examined whether the antimicrobial properties of tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein were linked to the inhibition of bacterial ATP synthase. Tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein inhibited Escherichia coli wild-type and mutant membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase to variable degrees. The growth properties of wild-type, null, and mutant strains in presence of above olive phenolics were also abrogated to variable degrees on limiting glucose and succinate. Tyrosol and oleuropein synergistically inhibited the wild-type enzyme. Comparative wild-type and mutant F1Fo ATP synthase inhibitory profiles suggested that αArg-283 is an important residue and olive phenolics bind at the polyphenol binding pocket of ATP synthase. Growth patterns of wild-type, null, and mutant strains in the presence of tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein also hint at the possibility of additional molecular targets. Our results demonstrated that ATP synthase can be used as a molecular target and the antimicrobial properties of olive phenolics in general and tyrosol in particular can be linked to the binding and inhibition of bacterial ATP synthase.

Keywords: E. coli F1Fo ATP synthase, olive phenolics, tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, dihydroxyphenylglycol, oleuropein, enzyme inhibition

1. Introduction

ATP synthase is the major source of ATP, the energy required to perform biological functions in almost all organisms from bacteria to man [1, 2]. The location of ATP synthase in bacteria is the plasma membrane and in humans is the inner membrane of the mitochondria. ATP is generated through the transmembrane electrochemical gradient by coupling ADP and Pi [3–5]. The lesser-known ectopic ATP synthase is found on the surface of numerous cell types where it serves as a ligand receptor and participates in various cellular processes, including angiogenesis, lipid metabolism, and the cytolytic pathway of tumor cells [6].

Cell survival and growth depends on an unhindered supply of ATP. As such, targeted cell death can be achieved through selective inhibition of ATP synthase. Thus, ATP synthase can be an effective and selective molecular target for treatment of various diseases, including microbial infections [6–8]. More than 300 natural and synthetic compounds are known to bind on the F1 or Fo sectors of ATP synthase, causing complete or partial inhibition. Along with antioxidants, chemotherapeutic, and antimicrobial properties, one of the major ATP synthase inhibitor categories is that of phenolic phytochemicals [6, 9–13].

Worldwide antimicrobial resistance is increasing at an alarming rate. By 2050, antibiotic resistant microbial infections are projected to cause millions of additional deaths and cost taxpayers about $100 trillion [14]. The World Health Organization’s global report on surveillance of antimicrobial resistance reports that antibiotic resistance is one of the main reasons for this alarming situation [15]. Finding new ways to kill microbes is an urgent global matter. Therefore, phenolic phytochemicals that can selectively bind and inhibit ATP synthase present an excellent opportunity for preventing and combating antibiotic resistant microbial infections.

The demand for evidence-based phytochemicals in general and plant-based phenolic constituents in particular as alternative remedies has increased [7, 13, 16–20]. A large number of dietary phenolic compounds from a variety of sources have been shown to have potential antitumor or antimicrobial properties [21–25]. Olives and its constituent phenolic compounds have nutraceutical properties and have been assessed for their strong antimicrobial properties at low concentrations against human intestinal and respiratory tract infections, such as those caused by Gram positive bacteria (Bacillus cereus, B. subtilis, and Staphylococcus aureus), Gram negative bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, E. coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae), and fungi (Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans) [26].

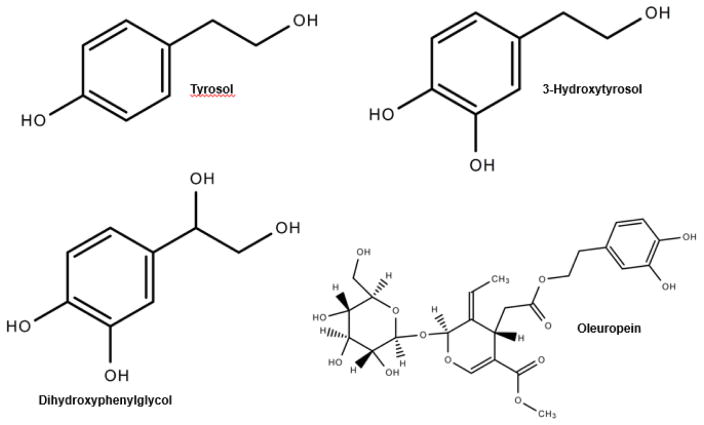

For centuries, olives from the Olea europea (European olive) have been widely enjoyed in foods throughout the world. Only about 10% of harvested olives are used as table olives and the rest is turned into oil [27]. Traditionally O. europea has been used for the treatment of several infectious disorders of bacterial, fungal, and viral origin. As such, the antimicrobial and antiviral potential of O. europaea has been confirmed in multiple studies [28]. Because olives are a rich source of phenolic compounds, olives and its products have been used to treat a variety of disease conditions, such as inflammation; diarrhea; hemorrhoids; and respiratory, urinary, and intestinal ailments. Moreover, olive constituents have been suggested to possess antimicrobial, anticancer, antidiabetic, antioxidant, antihypertensive, antiinflammatory, and antinociceptive properties and contribute to cardioprotective, gastroprotective, and neuroprotective activities ([27] and references therein). The structures of phenolic constituents of olive—tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG), and oleuropein—are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of olive phenolics tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG), and oleuropein.

Tyrosol is a naturally occurring polyphenol found in olives and extra virgin olive oil [29]. In in vitro studies, tyrosol was shown to be absorbed in a dose-dependent manner from virgin olive oil and indicated antioxidant activity. The bioavailability of tyrosol from virgin olive oil was enough to bind human low-density lipoprotein, suggesting that the phenolic constituents of olives are effective in preventing lipid peroxidation and atherosclerotic processes [29]. Tyrosol was also shown to have protective effects against ethanol-induced oxidative stress in HepG2 cells and prevent ethanol-induced liver damage [30]. Further, tyrosol has been shown to have comparable antiinflammatory effects in an endotoxin-induced uveitis rat model with prednisolone, a well-known antiinflammatory drug, which supports the potential of tyrosol in the treatment of intraocular inflammatory diseases [31]. Finally, the antimicrobial properties of tyrosol were observed in the inhibition of single- and mixed-species biofilm formation by the oral pathogen Streptococcus mutans [32].

Hydroxytyrosol is another naturally occurring phenolic phytochemical found in olives and extra virgin olive oil that has antiinflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial properties [33]. It was shown to have antidiabetic and antioxidant properties in alloxan-induced diabetic rats [34]. Administration of 8–16 mg/kg body weight of O. europaea leaf extracts containing oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol for four weeks resulted in significant reductions of serum cholesterol and glucose levels of the diabetic rats along with restoration of antioxidant enzymatic activities [34]. Hydroxytyrosol also possesses powerful antioxidant effects [35], inhibiting the H2O2 -induced DNA damage while indicating a correlation with antiproliferative activities of hydroxytyrosol on breast (MDA and MCF-7), prostate (LNCap and PC3), and colon (SW480 and HCT116) cancer cell lines from the effect of H2O2. Hydroxytyrosol was shown to act as a chemopreventive agent for the initiation and progression phases of carcinogenesis [35]. Furthermore, hydroxytyrosol and other phenolics from olive oil have been shown to eradicate in vitro microbial infections caused by Helicobacter pylori, commonly linked to peptic ulcers and gastric cancer [36]. Hydroxytyrosol is considered a unique HIV-1 inhibitor [37] and has been shown to prevent HIV from entering host cells and binding to the catalytic site of HIV-1 integrase [38].

DHPG is a major phenolic compound present in table olives and is a naturally occurring hydroxytyrosol derivative and metabolite of norepinephrine [39, 40]. DHPG has important implications as a biomarker and has been shown to fluctuate in concentration in rat testis after methamphetamine intake, which may result in male reproductive dysfunction [41]. DHPG was also shown to have some antioxidant activity [40, 42].

Oleuropein is one of the most abundantly found secoiridoid glycosides in olives and olive leaves [27]. Oleuropein is responsible for giving immature and unprocessed olives their bitter taste [43, 44]. Hydroxytyrosol is a metabolite of oleuropein and, thus, shares many similar structural and beneficial health properties with oleuropein [27]. Oleuropein was found to act as a potent antioxidant and reduced oxidative stress in alloxan diabetic rabbits. The treatment of diabetic rabbits with oleuropein doses of 20 mg/kg body weight for up to 16 weeks resulted in blood glucose values near the normal values of control rabbits, suggesting that oleuropein was a potent antihyperglycemic and antioxidative agent [45]. Oleuropein has also been shown to have cardioprotective properties through its antiischemic, antioxidative, and hypolipidemic effects in anesthetized rabbits [44, 46] and it has been shown to have neuroprotective effects [44]. Investigation of the effect of oleuropein on human colon adenocarcinoma cells (HT-29) suggested that oleuropein restricts cell growth and causes apoptosis of HT-29 cells by downregulation of HIF-1?? [47]. Moreover, oleuropein was effective against several microbial strains [48], and the combined olive phenolics of oleuropein and caffeic acid had a significantly higher antimicrobial effect than the individual phenolics [48].

To our knowledge, the bactericidal effects of dietary olive phenolics at the molecular level are unknown. For this reason, we studied the inhibitory effects of olive phenolics—tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein—on E. coli F1Fo ATP synthase and the growth of E. coli strains to determine if the dietary benefits of olive phenolics are linked to the binding and inhibition of ATP synthase. E. coli mutants αR283D, αE284R, βV265Q, and γT273A were used to confirm the binding site (s) for tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein. The results of this work indicate a possible link between the antimicrobial properties of olive phenolics and bacterial ATP synthase.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Olive phenolics and other chemicals

Tyrosol at greater than 98% purity (188255), hydroxytyrosol at greater than 98% purity (H4291), DHPG at greater than 95% purity, and oleuropein at greater than 98% purity (12247) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company. These compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain the desired working solution. The maximal volume of DMSO in ATPase assays was less than 1%. In the current study and previous studies, we noted that up to 40% DMSO by itself had no effect on membrane-bound F1Fo of E. coli ATP synthase [25, 49, 50]. All other chemicals and reagents used in the current study were ultrapure, analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company or Fisher Scientific Company.

2.2. Construction of E. coli wild type, null, and mutant strains

The wild-type E. coli strain with the ATPase gene and null strain without the ATPase gene used in this study were pBWU13.4/DK8 and pUC118, respectively [51]. The E. coli mutant strains pZA84 (αR283D), pZA88 (αE284R), pZA93 (βV265Q), and pZA95 (γT273A) were generated by Stratagene QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, catalog #210519-12) using CGTCCGCCAGGAGATGAAGCTTTCCCGGGCGAC, TCGTCCGCCAGGACGTCGAGCATTCCCGG, CCGTATGCCTTCAGCGCAAGGTTATCAGCCGACC, and CTCGTCAGGCCAGCATTGCGCAGGAACTCACCG primers, respectively. The amino acid replacement site is indicated by bold letters. The growth and viability of E. coli strains were checked on Luria Broth (molecular genetics grade from Fisher Scientific BP1426-2, formulation per liter was 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g sodium chloride).

2.3. Measurement of growth in limiting glucose, preparation of E. coli membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase, and ATPase activity assays

Oxidative and substrate-level phosphorylation were measured by growth yield on limiting glucose (3–5 mM), a fermentable carbon source, and on succinate (1.5M), a non-fermentable carbon source as in [52]. Because of the glycolytic pathway, on limiting glucose, the null strain grows about 40%–50% compared with the wild-type strain. In the absence of ATPase gene, the null strain is not expected to grow on succinate.

Membrane-bound E. coli F1Fo ATP synthase was isolated by growing E. coli to late log phase, harvesting cells in a super centrifuge (Avanti J-251, Beckman Coulter), lysing the cells in a high-pressure French Press (G-M Model 11, Glen Mills Inc.), and separating the membrane- bound F1Fo ATP synthase by ultracentrifugation (Optima LE-80K, Beckman Coulter) as in [53]. This procedure involved three washes of the initial membrane pellets. Wash one was done in a buffer containing 50 mM TES pH 7.0, 15% glycerol, 40 mM 6-aminohexanoic acid, and 5 mM p-aminobenzamidine. The two subsequent washes were done in a buffer containing 5 mM TES pH 7.0, 15% glycerol, 40 mM 6-aminohexanoic acid, 5 mM p-aminobenzamidine, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. The membrane-bound enzyme was washed twice more by resuspension and ultracentrifugation in a buffer containing 50 mM TrisSO4 pH 8.0 with 2.5 mM MgSO4.

ATPase activities were performed in a 1 mL ATPase cocktail containing 10 mM NaATP, 4 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM TrisSO4 pH 8.5 at 37°C. Reactions were started by the addition of 1 mL ATPase cocktail to membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase and stopped by the addition of 1 mL sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to a 3.3% final concentration. Liberated inorganic phosphate was measured spectrophotometrically at optical density (OD)700 as in [54]. The addition of 1 mL Taussky and Shorr reagent [54] develops a blue color with Pi, and the intensity of the color is directly proportional to the activity of enzyme. For ATPase assays, 20 μg wild-type and 20–40 μg mutant proteins were used for a 20–60 minute reaction time. We confirmed that reaction time and protein concentration had no bearing on the reaction outcome. Purity and integrity of membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was established on 10% SDS-gel electrophoresis and by immunoblotting with rabbit polyclonal anti-F1-α and anti-F1-β antibodies [50, 55].

2.4. Olive phenolics induced inhibition of membrane-bound E. coli F1Fo ATP synthase

E. coli wild-type and mutant membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase were incubated with varied concentrations of tyrosol and its structural analogs hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein for 1 hour at 37°C in 50 mM TrisSO4 pH 8.0 buffer. One mL ATPase cocktail was added to initiate the ATPase reaction. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 mL SDS to a final concentration of 3.3%. The addition of 1 mL of Taussky and Shorr reagent generated a blue color that was measured spectrophotometrically at OD700. Inhibitor induced exponential decay curves were generated using SigmaPlot 10.0. The best fit lines for the curves were acquired using a single, 3-parameter model from Regression Wizard Equation. Statistical significance of the relationship between relative ATPase activities against inhibitor concentrations were analyzed by linear regression. The absolute specific activity range for wild-type and mutant membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was between 5–10 μmol/min/mg at 37°C for the different preparations. The absolute ATPase activity values in the absence of inhibitors were used as a 100% benchmark to calculate the relative ATPase activity in the presence of inhibitors.

2.5. Hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein induced inhibition of membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase in the presence of a fixed concentration of tyrosol

The combined effect of olive phenolics were studied by preincubating the E. coli wild-type membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase at 7 mM and 10 mM inhibitory concentrations of tyrosol for 1 hour causing about 25% and 50% inhibition, respectively. Varied incremental concentrations of hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, or oleuropein were added and samples were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in 50 mM TrisSO4 pH 8.0 buffer. This procedure was followed by addition of 1 mL ATPase cocktail to initiate the reaction, 1 mL SDS to stop the reaction, and 1 mL Taussky and Shorr reagent to develop blue color, which was measured at OD700.

2.6. Growth of wild-type, mutant, and null strains in the presence of olive phenolics tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein

Growth properties of the six E. coli strains—wild-type, mutants (αR283D, αE284R,βV265Q, γT273A), and null—were checked on 5 mM limiting glucose and 1.5 M succinate media in the presence and absence of tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein. All E. coli strains were grown in a 96 well-plate for 24 hours on the AccuSkan GO Plate Reader at OD595. The growth signal data were analyzed using Thermo Fisher Scientific SkanIt 4.1 Software program.

3. Results

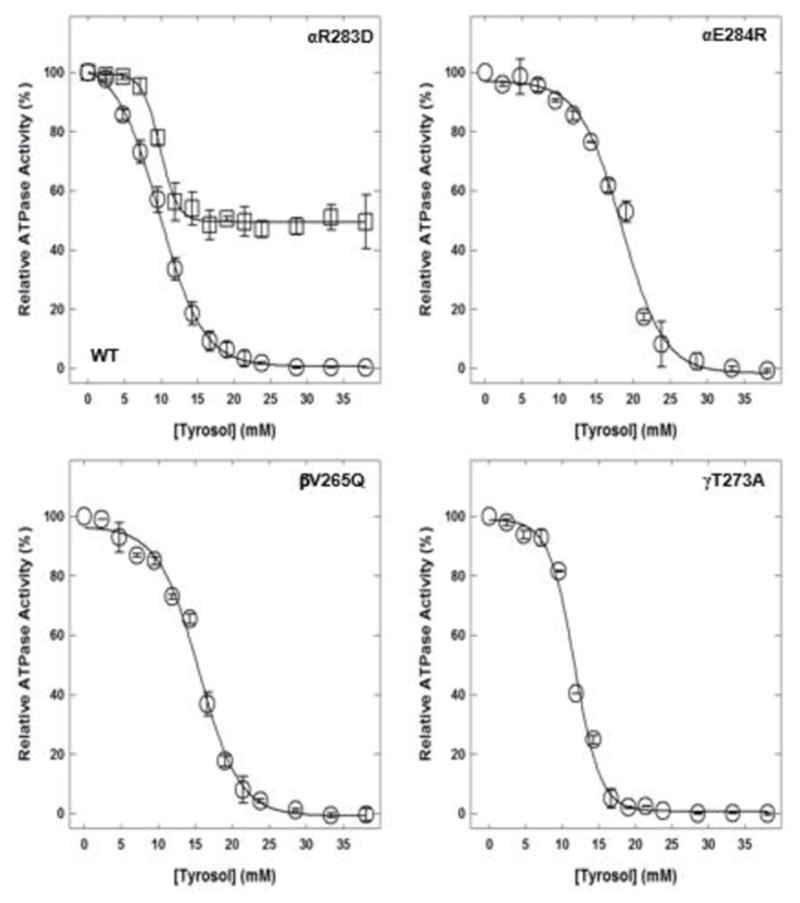

3.1. Tyrosol-induced inhibition of wild-type and mutant E. coli membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase

Tyrosol caused complete inhibition of wild-type, αE284R, βV265Q, and γT273A mutant enzymes and caused about 50% inhibition of the mutant αR283D membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase (Fig. 2). For wild-type enzyme, the maximal inhibition of almost 100% occurred at about 25 mM of tyrosol. For mutants αE284R, βV265Q, and γT273A 100% inhibition was achieved at about 30 mM, 32 mm, and 20 mM of tyrosol, respectively. The mutant αR283D enzyme retained about 50% residual activity up to 38 mM of tyrosol.

Figure 2. Tyrosol-induced inhibition of wild-type and mutant membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase.

Membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature with incremental concentrations of tyrosol, and then 1 mL of ATPase cocktail was added and activity measured. Experimental details are given in the Materials and Methods section. Each data point represents the average of 3–4 experiments done in duplicate tubes, using 2–3 independent membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase preparations.

Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; WT, wild-type.

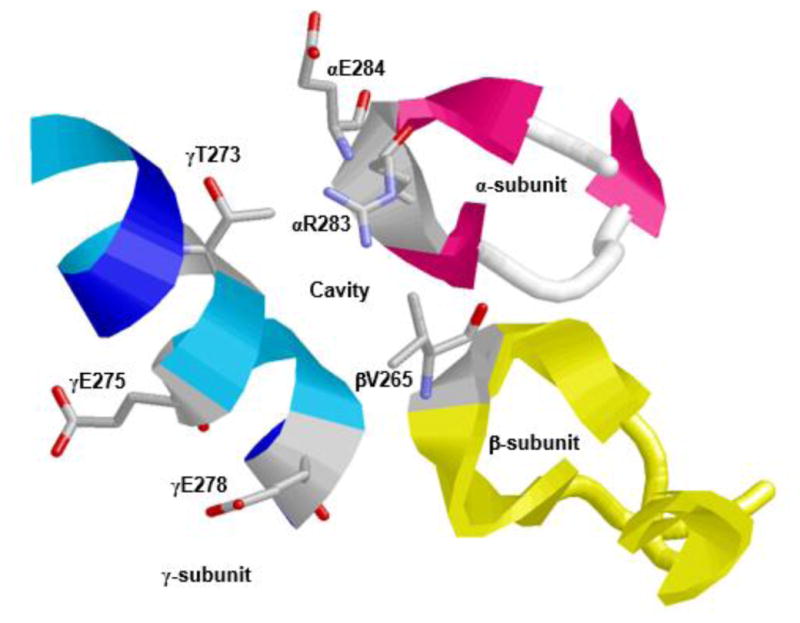

3.2. Plausible olive phenolic binding site on ATP synthase

To identify the residues and binding site for olive phenolics on E. coli ATP synthase, four E. coli mutant strains pZA84, pZA88, pZA93, and pZA95 with αR283D, αE284R, βV265Q, and γT273A mutations, respectively, were generated. The spatial relationship between α-, β-, and γ subunits along with αArg-283, αGlu-284, βVal-265, and γThr-273 residues forming a possible olive phenolic binding cavity is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. X-ray crystallographic structure of F1Fo ATP synthase illustrating the polyphenol binding pocket.

α-, β-, and γ-subunits forming an olive phenolic binding cavity is depicted. Residues αArg-283, αGlu-284, βVal-265, and γThr-273 along with γGln-275 and γGln 278 are identified. RasMol software was used to generate the figure with PDB file 2JJ1 [12]. Escherichia coli residue numbering is used.

Abbreviation: ATP, adenosine triphosphate.

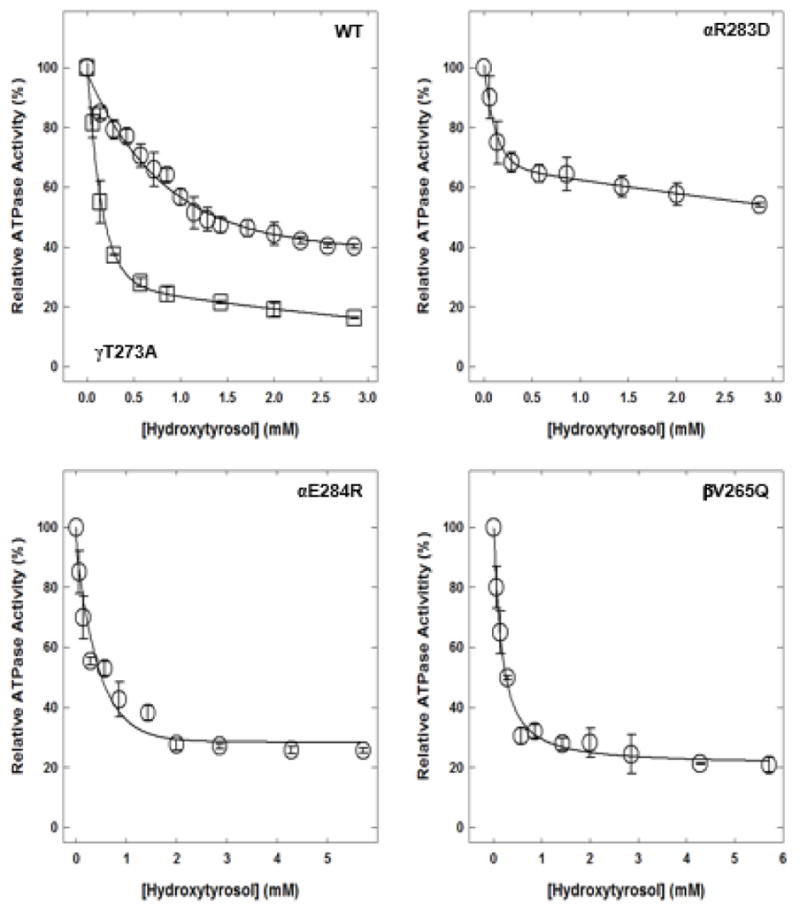

3.3. Hydroxytyrosol-induced inhibition of wild-type and mutant E. coli membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase

Hydroxytyrosol caused partial inhibition of wild-type and mutant enzymes (Fig. 4). Inhibition of wild-type membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was about 62%, mutant αR283D was about 45%, mutant αE284R was about 75%, mutant βV265Q was about 80%, and mutant γT273A was about 84%.

Figure 4. Hydroxytyrosol-induced inhibition of E. coli wild-type and mutant membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase.

Membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature with varied concentrations of hydroxytyrosol, and then 1 mL of ATPase cocktail was added and activity measured. Experimental details are given in the Materials and Methods section. Each data point represents the average of 3–4 experiments done in duplicate tubes, using 2–3 independent F1Fo membrane preparations.

Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; WT, wild-type.

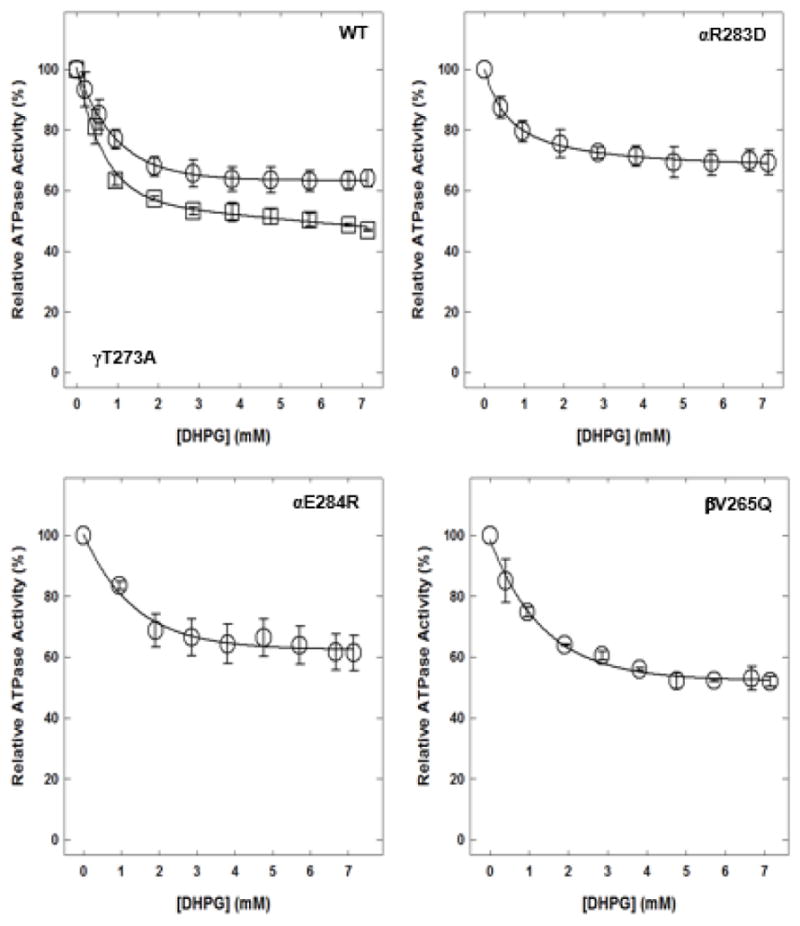

3.4. DHPG-induced inhibition of wild-type and mutant E. coli membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase

DHPG caused partial inhibition of wild-type and mutant enzymes (Fig. 5). Wild-type membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was inhibited about 35%, mutant αR283D about 31%, mutant αE284R about 38%, mutant βV265Q about 48%, and mutant γT273A about 53%.

Figure 5. Dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG)-induced inhibition of wild-type and mutant membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase.

Membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature with varied concentrations of DHPG, and then 1 mL of ATPase cocktail was added and activity measured. Each data point is the average of 3–4 experiments done in duplicate tubes, using 2–3 independent F1Fo membrane preparations.

Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; WT, wild-type.

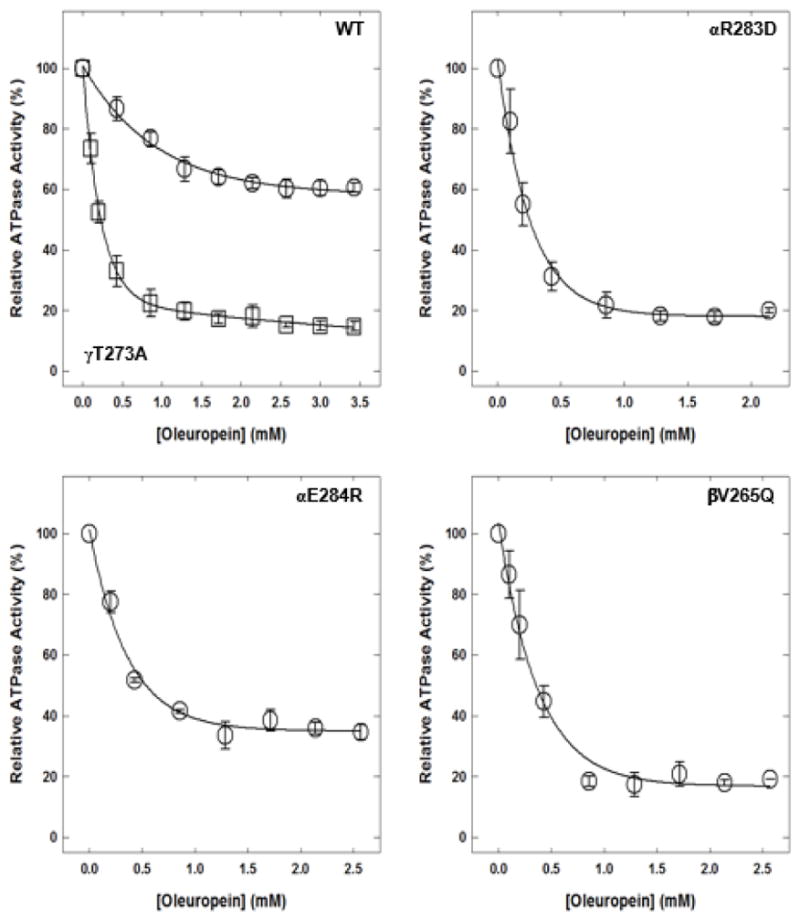

3.5. Oleuropein-induced inhibition of wild-type and mutant E. coli membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase

Oleuropein induced variable inhibition of wild-type and mutant enzymes (Fig. 6). Wild-type membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was inhibited about 40%, mutant αR283D about 80%, mutant αE284R about 65%, mutant βV265Q about 81%, and mutant γT273A about 85%.

Figure 6. Oleuropein-induced inhibition of wild-type and mutant membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase.

Membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature with varied concentrations of oleuropein, and then 1 mL of ATPase cocktail was added and activity measured. Each data point is the average of 3–4 experiments done in duplicate tubes, using 2–3 independent F1Fo membrane preparations.

Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; WT, wild-type.

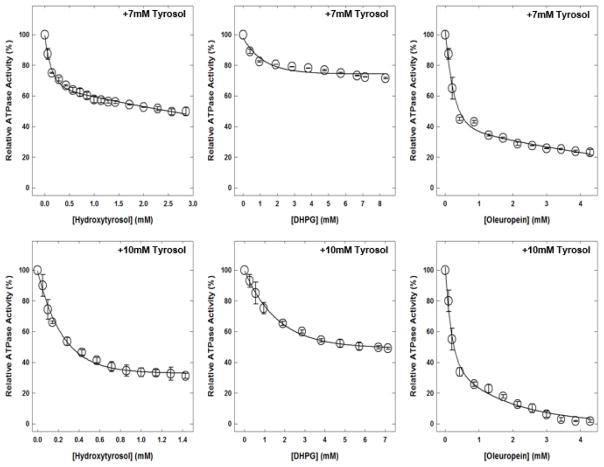

3.6. Hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, or oleuropein induced inhibition of E. coli membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase in the presence of fixed tyrosol concentrations

Figure 7 shows the hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, or oleuropein induced inhibitory profiles of wild-type E. coli membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase in the presence of fixed concentrations of tyrosol. With 25% inhibition (7 mM) by tyrosol, the combined maximum inhibition with hydroxytyrosol was about 50%, about 29% with DHPG, and about 77% with oleuropein. With 50% inhibition (10 mM) by tyrosol, the combined maximum inhibition with hydroxytyrosol was about 70%, about 50% with DHPG, and about 99% with oleuropein.

Figure 7. Hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, or oleuropein-induced inhibition of wild-type membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase in presence of fixed concentrations of tyrosol.

Membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase was incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature with two fixed concentrations of 7 and 10 mM of tyrosol. Top panel (7 mM) represents 25% and bottom panel (10 mM) represents 50% inhibition points in the presence of tyrosol. Tyrosol incubation was followed by incremental addition of hydroxytyrosol, dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG), or oleuropein; and samples were incubated for an additional 60 minutes. Then, 1 mL ATPase cocktail was added and activity was measured at optical density (OD)700. Each data point is the average of 3–4 experiments done in duplicate tubes, using 2–3 independent F1Fo ATP synthase membrane preparations.

Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate.

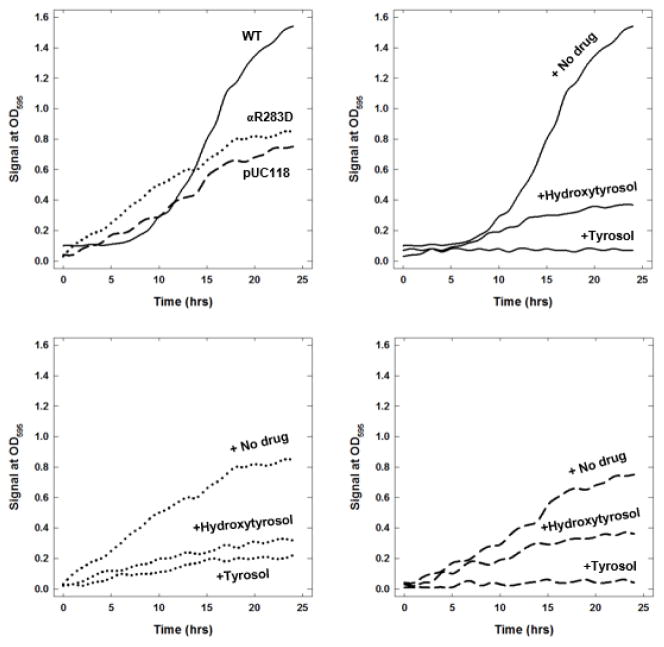

3.7. Growth of E. coli on limiting glucose and succinate in the presence of olive phenolics tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein

The Table shows the growth of wild-type, mutant, and null E. coli strains on limiting glucose (fermentable carbon source) and succinate (non-fermentable carbon source) in the presence and absence of olive phenolics tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein inhibitors. Wild-type and mutant growth were affected to variable degrees by the presence of inhibitors. On limiting glucose and succinate, tyrosol almost fully abrogated the wild-type and null strain growth. For mutants, tyrosol caused significant variable inhibition. Hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein caused partial to significant inhibition of wild-type, null, and mutant strains on limiting glucose and succinate. Growth signals of wild-type, mutant αR283D, and null strains on limiting glucose in the presence and absence of tyrosol and hydroxytyrosol are shown in Figure 8.

Table 1.

Growth of Escherichia coli strains in presence of olive phenolics; tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein.

| Presence/absence of inhibitors | Growth on limiting glucosea (%) | Growth on succinateb (%) |

|---|---|---|

| WTc | 100 | 100 |

| Nulld | 48±3 | 0 |

| αR283D | 54±1 | 48±3 |

| αE284R | 63±3 | 59±2 |

| βV265Q | 58±2 | 51±3 |

| γT273A | 54±4 | 47±4 |

| WT + Tyrosol | 1±1 | 0 |

| Null + Tyrosol | 3±1 | 0 |

| αR283D + Tyrosol | 24±4 | 19±4 |

| αE284R + Tyrosol | 3±2 | 6±2 |

| βV265Q + Tyrosol | 3±2 | 5±2 |

| γT273A + Tyrosol | 2±2 | 2±2 |

| WT + Hydroxytyrosol | 23±1 | 20±3 |

| Null + Hydroxytyrosol | 24±2 | 0 |

| αR283D + Hydroxytyrosol | 38±8 | 30±2 |

| αE284R + Hydroxytyrosol | 26±5 | 29±2 |

| βV265Q + Hydroxytyrosol | 8±3 | 11±3 |

| γT273A + Hydroxytyrosol | 5±2 | 6±2 |

| WT + DHPG | 46±4 | 39±2 |

| Null + DHPG | 33±3 | 35±3 |

| αR283D + DHPG | 60±5 | 46±4 |

| αE284R + DHPG | 61±3 | 53±3 |

| βV265Q + DHPG | 38±4 | 42±2 |

| γT273A + DHPG | 6±3 | 7±2 |

| WT + Oleuropein | 24±2 | 16±5 |

| Null + Oleuropein | 10±2 | 0 |

| αR283D + Oleuropein | 9±1 | 11±2 |

| αE284R + Oleuropein | 21±3 | 11±3 |

| βV265Q + Oleuropein | 15±3 | 18±3 |

| γT273A + Oleuropein | 7±3 | 5±2 |

Growth yield on limiting glucose (fermentable carbon source) was measured as OD595 with hourly reading for 24 hours at 37 °C in AccuSkan Go Plate Reader.

Growth on succinate medium (non-fermentable carbon source) was measured as OD595 with hourly reading for 36 hours at 37 °C in AccuSkan Go Plate Reader.

Wild-type (pBWU13.4/DK8) contains UNC+ gene encoding ATP synthase

Null, (pUC118/DK8) is UNC− gene encoding ATP synthase is removed.

The absolute wild-type OD values were used as 100% bench mark to calculate relative OD values for null and mutant. Data points are average of at least three sample assays.

Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; OD, optical density; WT, wild-type.

Figure 8. Wild-type, mutant, and null E. coli growth signals at OD595 in the presence and absence of tyrosol and hydroxytyrosol.

About 200 μL Escherichia coli culture was grown in limiting glucose with maximal inhibitory concentrations of tyrosol (25 mM) and hydroxytyrosol (3 mM) in a 96-well plate. OD at λ595 nM was set to be measured every 60 minutes for 24 hours with shaking. Experimental details are given in the Materials and Methods section. Each data point is the average of at least three sample readings.

Abbreviations: OD, optical density; WT, wild-type.

4. Discussion

The objective of the current study was to determine if the antimicrobial properties of olive phenolics—tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein—are linked to the inhibition of ATP synthase. If so, we wanted to also determine whether these olive phenolics bind at the polyphenol binding pocket of ATP synthase. The current growing microbial resistance against valuable antibiotics warrants investigation of alternative drugs and ways to combat microbial infections.

Of the four olive phenolics used in the current study, only tyrosol fully inhibited wild-type membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase. The αE284R, βV265Q, and γT273A mutants were also completely inhibited, but the αR283D mutant was inhibited about 50%. As expected, the ionic interactions between the Arg guanido group and tyrosol hydroxyl groups are lost with the replacement of a positively charged residue by a negatively charged residue. The 50% inhibition of the αR283D mutant enzyme by tyrosol corroborates our notion that tyrosol may also bind at the polyphenol binding pocket of ATP synthase. Furthermore, αArg-283 appeared to be one of the important residues required for the binding of tyrosol at this site.

We generated the αE284R mutant to increase the binding affinity between the additional positive charge and hydroxy groups of tyrosol, and the other olive phenolic compounds. However, the αE284R mutant was fully inhibited by tyrosol contrary to our belief that initial inhibition would not occur for up to 10 mM of tyrosol. Complete inhibition of mutant αE284R occurred at about 35 mM of tyrosol instead of at 25 mM for the wild-type. Moreover, the αGlu-284 protrudes away from the possible tyrosol binding cavity, and that would likely be the case for the αArg-284 side chain. Therefore, the extra positive charge did not facilitate quicker and tighter binding. The addition of a bigger residue, βGln-265, to perturb the binding site apparently did not affect tyrosol binding. A plausible explanation for this result could be that the side chain of βGln-265 protrudes into the cavity and does not cause much steric disturbance. Similar to the αE284R mutant, it also took about 10 mM of additional tyrosol to completely inhibit the βV265Q mutant compared with the wild-type enzyme. The γT273A mutant was also generated to increase faster and tighter binding of olive phenolics by avoiding the repulsion between –OH groups of olive phenolics and Thr residue. The removal of hydroxy group, γT273A, enabled the faster inhibition. It took about 5 mM less tyrosol to cause complete inhibition of the γT273A mutant.

In a previous study, resveratrol-, piceatannol-, and quercetin-bound ATP synthase x-ray crystal structures indicated that the polyphenol binding pocket for resveratrol, piceatannol, and quercetin was collectively formed by the α-, β-, and γ-subunit residues [12]. Other dietary polyphenolic compounds have also been shown to bind to the polyphenol binding pocket [25, 49, 50, 56, 57]. Recently, site-directed mutagenic studies confirmed that safranal, a phenolic compound, binds at the polyphenol binding site and that the αArg-283 residue is essential for that binding [25]. Therefore, in the current study, we mutated αArg-283 to αAsp-283, αGlu-284 to αArg-284, βVal-265 to βGln-265, and γThr-273 to γAla-273 to confirm the role of these residues in the binding of the olive phenolics tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein at the polyphenol binding site.

Figure 3 shows the projected αArg-283 side chain in the cavity where tyrosol and the other olive phenolic compounds were expected to bind. Tyrosol-induced inhibition of wild-type and αR283D mutant enzymes showed that the guanidino group of αArg-283 is essential for apt binding of tyrosol at the polyphenol binding pocket of E. coli ATP synthase. Furthermore, the hydroxy groups of tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein may develop hydrophobic, nonpolar interactions with other polyphenol binding pocket residues, such as γGln274, γThr-277, βAla-264, γAla-270, γGlu-278, or αGly-282.

Hydroxytyrosol induced partial inhibition of wild-type and mutant F1Fo membranes. Removal of a positive charge by replacing αArg-283 with αAsp-283 resulted in about 17% lesser inhibition. The addition of a positive charge by replacing αGlu-284 with αArg-284 resulted in about 13% additional inhibition. Substituting a smaller side chain by a bigger side chain by replacing βVal-265 with βGln-265 augmented the inhibition by about 18%. Removal of hydroxy group by replacing γThr-273 with γAla-273 caused about 22% more inhibition. This gain or loss of inhibition in mutant enzymes could be attributed to the ionic interaction between the positively charged guanido group of the Arg residue and hydroxy groups of hydroxytyrosol. Loss of a positive charge from the αR283D mutant resulted in lower affinity, weaker binding, and less inhibition. Gain of an additional positive charge from αE284R resulted in higher affinity, stronger binding, and more inhibition. Similarly, removal of –OH group from γT273A resulted in stronger and augmented inhibition.

DHPG caused nearly identical inhibition of the wild-type and two of the mutants, αR283D and αE284R, by 35±4%. The DHPG-induced inhibition of mutants βV265Q and γT273A was enhanced by about 13% and 18% from 35% to 48% and 53%, respectively, compared with the wild-type. The addition or removal of a positive charge from the Arg side chain did not change the extent of inhibition. Introducing a polar amide side chain, βGln-265, allowed the four hydroxy groups of DHPG to form additional hydrogen bonds. Removal of –OH group from the side chain, γT273A, removed the possible repulsion between hydroxy groups. Therefore, the βV265Q and γT273A mutant enzymes showed greater inhibition than the wild-type enzyme.

Oleuropein caused about 40%, 25%, 41%, and 44% more inhibition of mutants αR283D, αE284R, βV265Q, and γT273A respectively, compared with the wild-type. The phenylethanoid structure of oleuropein was expected to augment the inhibition of mutants. Additionally, the two methyl groups and multiple hydroxy groups of oleuropein may improve the chances of hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions along with the added negative charge from αR283D, positive charge from αE284R, an amide group from βV265Q, or with the loss of –OH group from γT273A. The variety and spatial positioning of functional groups of inhibitors is one of the main reasons behind complete or partial inhibition of enzymes in general and ATP synthase in particular [57]. In previous studies, numerous instances of variable maximal inhibition of ATP synthase have been observed where wild-type or mutant enzymes were partially or incompletely inhibited by phytochemicals, peptides, NBD-Cl, NaN3, AlCl3, or ScCl3 [5, 49, 55, 58, 59].

To confirm the maximum achievable inhibition by tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein, wild-type and mutant membrane-bound F1Fo preparations were incubated with maximal inhibitory concentrations of each inhibitor for 1 hour. This inhibition was followed by an additional pulse of the same inhibitory concentration of tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein, and incubation was continued for an additional hour before the ATPase assay. Little or no additional inhibition was observed, suggesting that inhibitors fully reacted at the binding site and that retained residual activity was not from the degradation of inhibitors.

For a natural or synthetic compound to be biologically active and to trigger or block a biological response, it must possess a group of steric and electronic features that ensures optimal supramolecular interactions [60]. These features are called pharmacophoric features, and the presence of an unsaturated nucleus is one of the pharmacophoric properties of a compound. Olive phenolics, such as tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein, all possess an unsaturated nucleus and caused variable inhibition of membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase. Further, tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein induced inhibition profiles of membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase provide experimental evidence for tyrosol as a lead molecule for the development of selective antimicrobial agents and ATP synthase as a potent molecular target.

The olive phenolics hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein induced inhibition of wild-type F1Fo ATP synthase in the presence of fixed concentrations of tyrosol, demarcates their synergistic, additive, or antagonistic properties. Tyrosol caused 100% inhibition of wild-type F1Fo ATP synthase. Therefore, two fixed tyrosol concentrations of 7 mM and 10 mM were used so that 25% and 50% inhibition of wild-type F1Fo ATP synthase could be achieved. Hydroxytyrosol caused only about 50% and 70% inhibition with the 25% and 50% inhibition by tyrosol, respectively. This level of inhibition appeared to be antagonistic and had a less than additive effect for the 25% and 50% tyrosol inhibition levels, respectively. Also, DHPG induced inhibition of the wild-type enzyme in the presence of the two fixed concentrations of tyrosol did not result in an additive or synergistic effect. The maximum amount of DHPG induced inhibition with the 25% and 50% inhibition by tyrosol was 29% and 51%, respectively, which was equal to the inhibition by tyrosol itself. This type of behavior may occur if there is high binding affinity for tyrosol compared to hydroxytyrosol or DHPG.

The combined inhibitory effect of oleuropein and tyrosol can be considered a synergistic effect. Oleuropein by itself caused about 42% inhibition of wild-type membrane bound F1Fo ATP synthase. Oleuropein induced inhibition of wild-type enzyme in combination with the 25% inhibition by tyrosol resulted in about 77% inhibition. This 77% inhibition is about 12% more than the sum of tyrosol (25%) and oleuropein (40%). Similarly, oleuropein induced inhibition of the wild-type enzyme in combination with the 50% inhibition by tyrosol is about 99%. This joint inhibitory effect is more than the sum of two together, which is about 90%. Given these results, tyrosol and oleuropein seem to interact and produce a combined synergistic effect that is greater than the sum of their individual effects.

The growth properties of the wild-type, mutant, and null E. coli strains on limiting glucose and succinate in the presence and absence of olive phenolics tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein were in excellent agreement with their inhibition profiles. Tyrosol fully abrogated the wild-type (pBWU13.4/DK8) E. coli cell growth. On limiting glucose, the null strain (pUC118/DK8) typically grows about 50% compared with the wild-type. In the absence of ATP synthase, the null strain uses the glycolytic pathway to generate ATP, and the wild-type strain uses all three pathways to generate ATP: glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle, oxidative phosphorylation. In the absence of the ATPase gene, the null strain is unable to grow on succinate. The inhibition level for the wild-type and mutant strains was more than the inhibition level of the membrane-bound enzyme. The null strain inhibition level was also prominent, especially for tyrosol which was about 98% and oleuropein which was about 92%. The higher inhibition of the E. coli wild-type and mutant strains along with near full inhibition of the null strain compared with the inhibition of membrane-bound F1Fo ATP synthase could be attributed to the inhibition of additional targets including damage to the bacterial membranes by the olive phenolics.

When considering the growth signals of wild-type, mutant, and null E. coli strains in the presence or absence of olive phenolics, the growth retention in the null strain likely came from ATP production through the glycolytic pathway. Partial growth loss in the null strain may be attributed to membrane damage or interaction with other non-specified targets. A complete loss of growth in wild-type in the presence of tyrosol may result from the loss of oxidative phosphorylation through inhibition of ATP synthesis. Augmented growth loss in the mutant stain compared with the mutant enzyme may explain this result because of membrane damage or involvement of additional molecular targets including ATP synthase. Complete inhibition of wild-type growth in succinate (as the sole carbon source) in the presence of tyrosol establishes the inhibition of F1-ATPase activity. As such, these results suggested that tyrosol-induced abrogation of microbial growth occurred through the inhibition of ATP synthase.

The range of phenolic compounds in extra virgin olive oil is about 50–800 mg/kg [61]. Consumption of about 50 g of olive oil with a concentration of 180 mg/kg a day provides about 9 mg of olive phenolic compounds [62]. A high concentration of tyrosol at about 25 mM caused the complete inhibition of ATP synthase. Tyrosol is primarily found in extra virgin olive oil, but it is also synthesized endogenously by humans [63]. Tyramine, which is derived from the amino acid tyrosine, can undergo a metabolic pathway in humans leading to the formation of tyrosol [64]. Tyrosol is mainly glucuronidated after intake and is one of the main metabolite forms of tyrosol in humans [65]. Recently, another phenolic phytochemical, safranal, was shown to cause inhibition of ATP synthase at high concentrations [25]. It was also shown that high concentrations of safranal were essential to cause the observed pharmacological effects, and these concentrations are non-toxic in animals and humans [66]. The bioavailability of tyrosol through urine and plasma quantification analyses after oral administration of extra virgin olive oil has been confirmed in human participants [67, 68]. Despite the above bioavailability studies on tyrosol, consistent quantitative data on the concentrations of tyrosol in human plasma after ingestion of extra virgin olive oil is unavailable. This lack of data could result from tyrosol’s rapid excretion from the body and its diverse array of metabolic fates [67].

Hydroxytyrosol is a metabolite of oleuropein and is absorbed at a rate of 55%–60% by human subjects. Hydroxytyrosol has been detected in plasma and urine after ingestion of olive leaf extract [65, 69]. The main metabolites of hydroxytyrosol collected in the urine are conjugated glucuronide forms, which are produced by linking glucuronic acid to other substances via glycosidic bonds [65]. Similar to tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol is rapidly eliminated from the plasma, making it difficult to accurately estimate its concentration [70]. Toxicological evaluation of pure hydroxytyrosol showed a no observed adverse effects level of up to 500/mg/kg/day [71]. This suggests that higher inhibitory concentrations of olive phenolics should not be a concern for their use as antimicrobial agents.

DHPG is a naturally occurring hydroxytyrosol derivative [39, 40]. High levels of DHPG (up to 368 mg/kg of dry weight) have been observed in the pulp of natural black olives [40]. DHPG is also a naturally occurring endogenous intraneuronal metabolite of norepinephrine [72]. No data about DHPG toxicity or human plasma concentration after oral administration of extra virgin olive oil is currently available. However, DHPG has been detected in animal plasma using high performance liquid chromatography techniques [73].

The metabolic fate of oleuropein depends on the developmental stage of the olives. For instance, oleuropein changes to oleuropein-aglycone as the olives ripen. In olive oil, oleuropein-aglycone is hydrolyzed to hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol [74]. Further, humans absorb up to 55%–60% of hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol, and oleuropein-aglycone after ingestion of varied doses. Oleuropein is also metabolized into hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol by human subjects as evidenced by concentrations in urine samples [74]. From the ingestion of 250 mg of oleuropein-rich olive leaf extract, oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and tyrosol metabolites were found in plasma and urine of humans, but the respective concentrations were undetermined [65]. In addition, high performance liquid chromatography can detect up to 1.25 μg/mL of oleuropein in human plasma with 5.9% error [75]. While the toxicity of oleuropein is unknown, as an antioxidant, oleuropein has been shown to defend against the toxicities of many compounds in in vitro and in vivo studies [44].

ATP synthase is a fascinating biological macromolecule to study, and research is continuing to explore its potential role and use as a therapeutic molecular drug target. Many classes of inhibitors with unique chemical properties can selectively inhibit different subunits in both F1 and Fo sectors of ATP synthase [6–8, 24]. The role of ATP synthase as a potent molecular drug target has been documented through inhibitory profiles and the profound effect of ATP synthase on cell growth and survival [6–8]. Mutagenic analysis of ATP synthase has revealed the involvement of specific residues and their selective interactions with inhibitors. For example, a variety of phytochemicals and peptides have been evaluated to selectively bind at the polyphenol and peptide binding pockets of ATP synthase, respectively [8, 12]. While it is evident that ATP synthase plays a strong role in drug targeting and therapeutics, more research is needed to explore the mechanisms of ATP synthase inhibition and its impact on human health and disease.

The inhibition of microbial cell growth in the presence of phytochemicals from previous studies [11, 25, 49, 50, 56, 76] and the olive phenolics—tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, DHPG, and oleuropein—from the current study suggest that ATP synthase can be used as a potential molecular drug target to combat microbial infections. In conclusion, the tyrosol induced inhibition of ATPase activity and E. coli cell growth in the current study indicate that the antimicrobial properties of tyrosol can be linked to its inhibitory effects on ATP synthase.

Acknowledgments

The current study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number GM085771) to ZA and by the A.T. Still University-Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine Biomedical Science Graduate Program (funding number 850-611) to ZA and AA. ZA is grateful to Dr. Margaret Wilson, dean of Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine, for providing funding to purchase the AccuSkan GO Plate reader. We are also thankful to Dr. Robert W. Baer, Professor, Department of Physiology, Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine, for his suggestions on synergistic experimental design. We truly appreciate the help of Deborah Goggin, scientific writer, Research Support, A.T. Still University, for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Senior AE. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:30049–30062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.X112.402313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad Z, Cox JL. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014:10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber J, Senior AE. FEBS Lett. 2003;545:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noji H, Yoshida M. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1665–1668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad Z, Okafor F, Laughlin TF. J Amino Acids. 2011;2011:785741. doi: 10.4061/2011/785741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong S, Pedersen PL. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:590–641. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagliarani A, Nesci S, Ventrella V. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2016;16:815–824. doi: 10.2174/1389557516666160211120955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad Z, Okafor F, Azim S, Laughlin TF. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:1956–1973. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320150003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng J, Ramirez VD. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1115–1123. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piotto S, Concilio S, Sessa L, Porta A, Calabrese EC, Zanfardino A, Varcamonti M, Iannelli P. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;68:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B, Vik SB, Tu Y. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13632–13637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706290104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cushnie TP, Lamb AJ. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Neill J. [accessed 17.01.18];Review on antimicrobial resistance. 2016 2016:1–20. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. [accessed 17.01.18];:xxii, 232. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf.

- 16.Ahmad A, Khan A, Yousuf S, Khan LA, Manzoor N. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:1157–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caselli A, Cirri P, Santi A, Paoli P. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:774–791. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160106150821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karygianni L, Al-Ahmad A, Argyropoulou A, Hellwig E, Anderson AC, Skaltsounis AL. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1529. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandoval-Acuna C, Ferreira J, Speisky H. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;559:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madrigal-Perez LA, Ramos-Gomez M. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:368. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad I, Muneer KM, Tamimi IA, Chang ME, Ata MO, Yusuf N. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;270:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azevedo C, Correia-Branco A, Araujo JR, Guimaraes JT, Keating E, Martel F. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:504–513. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2015.1002625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan SM, Youakim MF, Rizk AA, Thomann C, Ahmad Z. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016 doi: 10.1002/nau.23109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad Z, Laughlin TF. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:2822–2836. doi: 10.2174/092986710791859270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M, Amini A, Ahmad Z. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;95:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira AP, Ferreira IC, Marcelino F, Valentao P, Andrade PB, Seabra R, Estevinho L, Bento A, Pereira JA. Molecules. 2007;12:1153–1162. doi: 10.3390/12051153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashmi MA, Khan A, Hanif M, Farooq U, Perveen S. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:541591. doi: 10.1155/2015/541591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adnan M, Bibi R, Mussarat S, Tariq A, Shinwari ZK. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13:40. doi: 10.1186/s12941-014-0040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Covas MI, Miro-Casas E, Fito M, Farre-Albadalejo M, Gimeno E, Marrugat J, De La Torre R. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2003;29:203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stiuso P, Bagarolo ML, Ilisso CP, Vanacore D, Martino E, Caraglia M, Porcelli M, Cacciapuoti G. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17050622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato K, Mihara Y, Kanai K, Yamashita Y, Kimura Y, Itoh N. J Vet Med Sci. 2016;78:1631–1634. doi: 10.1292/jvms.16-0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arias LS, Delbem AC, Fernandes RA, Barbosa DB, Monteiro DR. J Appl Microbiol. 2016;120:1240–1249. doi: 10.1111/jam.13070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Remesy C, Jimenez L. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:727–747. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jemai H, El Feki A, Sayadi S. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:8798–8804. doi: 10.1021/jf901280r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosignoli P, Fuccelli R, Sepporta MV, Fabiani R. Food Funct. 2016;7:301–307. doi: 10.1039/c5fo00932d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero C, Medina E, Vargas J, Brenes M, De Castro A. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:680–686. doi: 10.1021/jf0630217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Zhang D, Lee JW, Bao J, Sun Y, Chang YT, Zhang J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Zhang D, Lee JW, Bao J, Sun Y, Chang YT, Zhang J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aparicio-Soto M, Sanchez-Fidalgo S, Gonzalez-Benjumea A, Maya I, Fernandez-Bolanos JG, Alarcon-de-la-Lastra C. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:836–846. doi: 10.1021/jf503357s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez G, Lama A, Jaramillo S, Fuentes-Alventosa JM, Guillen R, Jimenez-Araujo A, Rodriguez-Arcos R, Fernandez-Bolanos J. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:6298–6304. doi: 10.1021/jf803512r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janphet S, Nudmamud-Thanoi S, Thanoi S. Andrologia. 2016 doi: 10.1111/and.12616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez-Fidalgo S, Villegas I, Aparicio-Soto M, Cardeno A, Rosillo MA, Gonzalez-Benjumea A, Marset A, Lopez O, Maya I, Fernandez-Bolanos JG, Alarcon de la Lastra C. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Omar SH. Saudi Pharm J. 2010;18:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Omar SH. Sci Pharm. 2010;78:133–154. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.0912-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Azzawie HF, Alhamdani MS. Life Sci. 2006;78:1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreadou I, Iliodromitis EK, Mikros E, Constantinou M, Agalias A, Magiatis P, Skaltsounis AL, Kamber E, Tsantili-Kakoulidou A, Kremastinos DT. J Nutr. 2006;136:2213–2219. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.8.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cardeno A, Sanchez-Hidalgo M, Rosillo MA, Alarcon de la Lastra C. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65:147–156. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2013.741758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee OH, Lee BY. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:3751–3754. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chinnam N, Dadi PK, Sabri SA, Ahmad M, Kabir MA, Ahmad Z. Int J Biol Macromol. 2010;46:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmad Z, Laughlin TF, Kady IO. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ketchum CJ, Al-Shawi MK, Nakamoto RK. Biochem J. 1998;330(Pt 2):707–712. doi: 10.1042/bj3300707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Senior AE, Latchney LR, Ferguson AM, Wise JG. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;228:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senior AE, Langman L, Cox GB, Gibson F. Biochem J. 1983;210:395–403. doi: 10.1042/bj2100395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taussky HH, Shorr E. J Biol Chem. 1953;202:675–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao C, Syed H, Hassan SS, Singh VK, Ahmad Z. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;592:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dadi PK, Ahmad M, Ahmad Z. Int J Biol Macromol. 2009;45:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmad Z, Ahmad M, Okafor F, Jones J, Abunameh A, Cheniya RP, Kady IO. Int J Biol Macromol. 2012;50:476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Azim S, McDowell D, Cartagena A, Rodriguez R, Laughlin TF, Ahmad Z. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;87:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ahmad Z, Winjobi M, Kabir MA. Biochemistry. 2014;53:7376–7385. doi: 10.1021/bi5013063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wermuth CG, Ganellin CR, Lindberg P, Mitscher LA. Pure Appl Chem. 2009;70:1129–1143. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Visioli F, Galli C. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:4292–4296. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vissers MN, Zock PL, Katan MB. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:955–965. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodriguez-Morato J, Boronat A, Kotronoulas A, Pujadas M, Pastor A, Olesti E, Perez-Mana C, Khymenets O, Fito M, Farre M, de la Torre R. Drug Metab Rev. 2016;48:218–236. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2016.1179754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Panova NG, Veselovskaia NV, Medvedev AE. Vopr Med Khim. 1997;43:172–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garcia-Villalba R, Larrosa M, Possemiers S, Tomas-Barberan FA, Espin JC. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:1015–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moshiri M, Vahabzadeh M, Hosseinzadeh H. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2015;65:287–295. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1375681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miro Casas E, Farre Albadalejo M, Covas Planells MI, Fito Colomer M, Lamuela Raventos RM, de la Torre Fornell R. Clin Chem. 2001;47:341–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tuck KL, Freeman MP, Hayball PJ, Stretch GL, Stupans I. J Nutr. 2001;131:1993–1996. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.7.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Bock M, Thorstensen EB, Derraik JG, Henderson HV, Hofman PL, Cutfield WS. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:2079–2085. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201200795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bai C, Yan X, Takenaka M, Sekiya S, Nagata T. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:3998–4001. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aunon-Calles D, Canut L, Visioli F. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;55:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eisenhofer G, Ropchak TG, Stull RW, Goldstein DS, Keiser HR, Kopin IJ. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;241:547–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Wood S, Fernandez-Bolanos Guzman J, Duthie GG, de Roos B. Food Chem. 2011;126:1948–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vissers MN, Zock PL, Roodenburg AJ, Leenen R, Katan MB. J Nutr. 2002;132:409–417. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsarbopoulos A, Gikas E, Papadopoulos N, Aligiannis N, Kafatos A. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2003;785:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sekiya M, Chiba E, Satoh M, Yamakoshi H, Iwabuchi Y, Futai M, Nakanishi-Matsui M. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014;70:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]