Abstract

Importance

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes (hereafter referred to as the partnership) was established to improve the quality of care for patients with dementia, measured by the rate of antipsychotic prescribing.

Objective

To determine the association of the partnership with trends in prescribing of antipsychotic and other psychotropic medication among older adults in long-term care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This interrupted time-series analysis of a 20% Medicare sample from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2014, was conducted among 637 426 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in long-term care with Part D coverage. Data analysis was conducted from May 1, 2017, to January 9, 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Quarterly prevalence of use of antipsychotic and nonantipsychotic psychotropic medications (antidepressants, mood stabilizers [eg, valproic acid and carbamazepine], benzodiazepines, and other anxiolytics or sedative-hypnotics).

Results

Among the 637 426 individuals in the study (446 538 women and 190 888 men; mean [SD] age at entering nursing home, 79.3 [12.1] years), psychotropic use was declining before initiation of the partnership with the exception of mood stabilizers. In the first quarter of 2009, a total of 31 056 of 145 841 patients (21.3%) were prescribed antipsychotics, which declined at a quarterly rate of –0.53% (95% CI, –0.63% to –0.44%; P < .001) until the start of the partnership. At that point, the quarterly rate of decline decreased to –0.29% (95% CI, –0.39% to –0.20%; P < .001), a postpartnership slowing of 0.24% per quarter (95% CI, 0.09%-0.39%; P = .003). The use of mood stabilizers was growing before initiation of the partnership and then accelerated after initiation of the partnership (rate, 0.22%; 95% CI, 0.18%-0.25%; P < .001; rate change, 0.14%; 95% CI, 0.10%-0.18%; P < .001), reaching 71 492 of 355 716 patients (20.1%) by the final quarter of 2014. Antidepressants were the most commonly prescribed medication overall: in the beginning of 2009, a total of 75 841 of 145 841 patients (52.0%) were prescribed antidepressants. As with antipsychotics, antidepressant use declined both before and after initiation of the partnership, but the decrease slowed (rate change, 0.34%; 95% CI, 0.18%-0.50%; P < .001). Findings were similar when limited to patients with dementia.

Conclusions and Relevance

Prescribing of psychotropic medications to patients in long-term care has declined, although the partnership did not accelerate this decrease. However, the use of mood stabilizers, possibly as a substitute for antipsychotics, increased and accelerated after initiation of the partnership in both long-term care residents overall and in those with dementia. Measuring use of antipsychotics alone may be an inadequate proxy for quality of care and may have contributed to a shift in prescribing to alternative medications with a poorer risk-benefit balance.

This interrupted time-series analysis of a 20% Medicare sample examines the association of CMS’s National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes with trends in prescribing of antipsychotic and other psychotropic medication among older adults in long-term care.

Key Points

Question

Did the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes reduce the prescribing of antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications to older adults in long-term care?

Findings

In this interrupted time-series analysis of a 20% Medicare sample, use of antipsychotics and overall use of psychotropics declined, although this decrease did not accelerate after the start of the partnership. However, use of mood stabilizers (ie, antiepileptic medications typically used for bipolar disorder) increased and grew more rapidly after initiation of the partnership.

Meaning

Rather than increasing the use of nonpharmacologic treatments, prescribers may have shifted prescribing from antipsychotics to mood stabilizers even though mood stabilizers have less evidence of benefit for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Introduction

The behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are found in patients with all types and stages of dementia and occur in clusters or syndromes such as psychosis (delusions and hallucinations), agitation, aggression, and disinhibition.1,2,3 Nonpharmacologic interventions—better stated as behavioral and environmental interventions—are recommended by numerous guidelines, medical organizations, and expert groups as the preferred first-line treatment,4,5,6,7 although they have largely not been translated into routine clinical practice.8 Despite the fact that no drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, the current mainstay of treatment is the off-label use of psychotropic medications.9,10 Of such agents, atypical antipsychotics have the strongest base of evidence, although their benefits are moderate at best and they are associated with a significant increase in the risk of stroke and mortality.11,12 Given the concerns regarding mortality, the FDA issued black box warnings for atypical antipsychotics in 2005 and for conventional antipsychotics in 2008.

To address the continued high use of antipsychotics in patients in long-term care settings, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes (hereafter referred to as the partnership) in 2012 to “improve the quality of care” for nursing home residents with dementia.13 Although CMS developed a training program to promote “person-centered…high quality care” and the use of nonpharmacologic treatment alternatives to antipsychotics,13 the program’s quality measure is the prevalence of antipsychotic use, which CMS began reporting publicly through the Nursing Home Compare website and the Five-Star Quality Rating System for nursing homes.14 According to CMS, antipsychotic prescribing to patients in long-term care has decreased since the start of the partnership by more than 30%.15

However, it is unclear to what extent the use of antipsychotics was already declining before initiation of the partnership and what its association has been with the use of other psychotropic medications. Prior work examining antipsychotic prescribing in a national health care system found that, while the use of antipsychotics declined after the 2005 FDA black box warning, the overall rate of psychotropic use was unchanged, but the one class for which prescribing increased was mood stabilizers.16 These medications—primarily antiepileptic drugs, such as sodium valproate or carbamazepine—are typically used by psychiatrists to treat patients with bipolar disorder. Although reports of the use of benzodiazepines or mood stabilizers for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia have been published for decades, there is no high-quality evidence of efficacy for treating such symptoms of dementia with these alternatives to antipsychotics, while they are associated with a host of harms.12,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 Despite limited evidence to justify their use, mood stabilizers feature on candidate lists aimed at clinicians of medications to address the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.26,27,28 Although antidepressants may have efficacy for agitation,29 they have not shown efficacy for depression in dementia in 5 randomized clinical trials,30 and they, too, carry risk of adverse events for frail older adults such as nausea, hyponatremia, and cardiac conduction abnormalities. A recent examination of nursing facility survey data at the facility level found a reduction in antipsychotic and psychotropic use overall after initiation of the partnership.31 However, this analysis did not analyze prescribing trends leading to the partnership and, critically, did not include mood stabilizers.

Although antipsychotic use has declined since initiation of the partnership, a concerning potential unintended consequence would be if clinicians have used medication substitution to a different but unmeasured psychotropic agent, such as a mood stabilizer. Such substitutes have even less evidence of benefit than antipsychotics yet similar potential for harms20 and could suggest that increased use of nonpharmacologic treatments, which was a key goal of the partnership,13 has not occurred.

Methods

To track antipsychotic use, the partnership uses the “Percent of Residents Who Received an Antipsychotic Medication (Long-Stay)” measure from the Minimum Data Set (MDS), version 3.0,32 reported on a quarterly basis.15 Although it is the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care, the quality measure that the partnership uses and reports is not limited to residents with dementia. Our study denominator and numerator were constructed to approximate this MDS measure. However, because improving dementia care is the stated intent, we conducted secondary analyses limited to the subgroup of patients with dementia. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School institutional review board, which waived patient consent for these deidentified data.

Study Cohort

The data are drawn from a 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2014. We identified long-stay (≥100 days) residents of nursing facilities based on place of service and Current Procedural Terminology codes from nursing home claims in the Carrier (Physician/Supplier Part B file) and Outpatient files.33 Among these residents, we limited the sample to those with continuous fee-for-service and Medicare Part D coverage during the 100-day period. The MDS antipsychotic measure used for the partnership applies to all long-stay residents (ie, is not limited to patients with dementia) with the following 3 exclusions: schizophrenia, Tourette syndrome, and Huntington disease. Patients with these conditions, identified from inpatient (Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file) and outpatient files, were excluded from the primary analytic cohort (eTable 1 in the Supplement). A long-stay resident remained in the cohort (ie, denominator) until death or the end of the study period, whichever came first (N = 637 426).

Outcomes

Medication use was determined from the Part D prescription drug event file. Psychotropic medications of interest were antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and sedative-hypnotics (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Part D did not cover benzodiazepines until 2013.34 Therefore, sedative-hypnotics refers to nonbenzodiazepine medications; we determined benzodiazepine use separately beginning in 2013. We included memory medications (cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine hydrochloride) separately.

We grouped the data into sequential 3-month quarters and determined all prescriptions for a psychotropic medication of interest during a given quarter. Although 16 742 003 of 18 349 496 medication claims (91.2%) were for 30 days or less, we used the claim date and days’ supply to attribute medication use to all possible quarters (eg, a 14-day prescription filled in the final week of 2013 quarter 1 contributed to the numerator for both quarters 1 and 2). This method allowed us to calculate the outcomes of interest—percentages of long-stay patients prescribed each medication class—on a quarterly basis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted from May 1, 2017, to January 9, 2018. We used an interrupted time-series analysis to examine the association of the initiation of the partnership with prescribing of antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications. Period 1 is before initiation of the partnership (2009, quarter 1, through 2012, quarter 1) and period 2 is after initiation of the partnership (2012, quarter 2, through 2014, quarter 4). Our model used quarterly percentages as the dependent variable and included a linear time-trend variable, an indicator for the postpartnership time period to determine changes in the mean level of prescribing during each time period, and a term for the change in the linear time trend (slope) between periods 1 and 2. We used 2-tailed t tests to test the statistical significance of the partnership and controlled for autocorrelation by assuming a first-order autoregressive process. Because the partnership was launched specifically to improve care of patients with dementia, we repeated the analysis of medication use for the subcohort of patients with dementia. Owing to the large sample size, P < .01 was considered significant.

Results

Our final cohort included 637 426 patients with a long stay (≥100 days) in a nursing facility between 2009 and 2014 (Table 1). The mean (SD) age at entry was 79.3 (12.1) years, most patients were women (446 538 [70.1%]), and more than half the patients (325 545 [51.1%]) received a diagnosis of dementia.

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Cohort and Overall Long-term Care Population With Medicare, 2009-2014.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Study Cohort (n = 637 426) | Overall Long-term Care Population (N = 1 183 227)a | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | ||

| At entering nursing home | 79.3 (12.1) | 79.5 (11.9) |

| At end of study period or death | 81.7 (11.9) | 81.8 (11.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 190 888 (29.9) | 407 553 (34.4) |

| Female | 446 538 (70.1) | 775 674 (65.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 526 991 (82.7) | 1 000 070 (84.5) |

| Black | 64 102 (10.1) | 110 746 (9.4) |

| Hispanic | 29 720 (4.7) | 45 759 (3.9) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 10 006 (1.6) | 15 158 (1.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2622 (0.4) | 4300 (0.4) |

| Other | 2644 (0.4) | 4791 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 1341 (0.2) | 2403 (0.2) |

| Medical conditionsb | ||

| Dementia | 325 545 (51.1) | 587 769 (49.7) |

| Depression | 218 101 (34.2) | 395 700 (33.4) |

| Bipolar disorder | 18 020 (2.8) | 46 296 (3.9) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 2578 (0.4) | 6124 (0.5) |

| Other anxiety disorders | 117 242 (18.4) | 215 258 (18.2) |

| Parkinson disease | 33 414 (5.2) | 64 117 (5.4) |

| Charlson comorbidity indexc | ||

| 0 | 38 260 (6.0) | 74 122 (6.3) |

| 1 | 88 455 (13.9) | 164 438 (13.9) |

| >1 | 510 711 (80.1) | 944 667 (79.8) |

Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with any long-term care during study period.

Determined based on health care encounters during the 12 months preceding entry into long-term care.

Weighted score based on the presence of dementia, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatologic disease, peptic ulcer disease, cirrhosis, hepatic failure (weighted by 3), diabetes mellitus, diabetes mellitus with complications (weighted by 2), hemiplegia (weighted by 2), chronic renal disease (weighted by 2), malignant neoplasm (weighted by 2), leukemia (weighted by 2), lymphomas (weighted by 2), metastatic solid tumor (weighted by 6), HIV without AIDS (weighted by 2), and AIDS (weighted by 6).

Psychotropic Prescribing Among Long-term Care Residents Overall

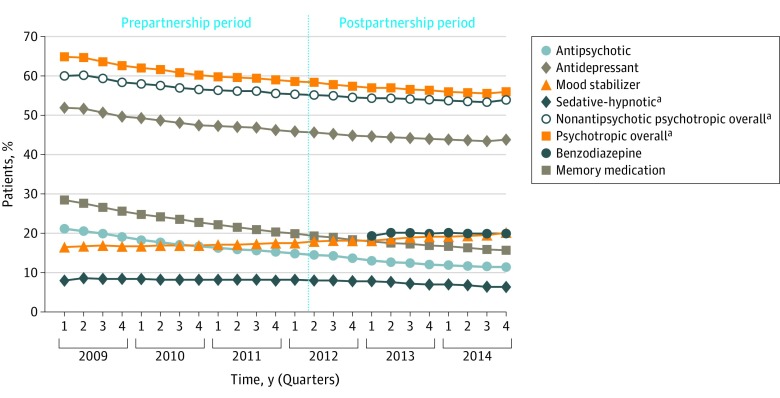

Figure 1 presents the percentage of patients prescribed a psychotropic or memory medication on a quarterly basis before (period 1) and after (period 2) initiation of the partnership (eTable 3 in the Supplement presents the quarterly rates represented in Figure 1). At the start of 2009, a total of 31 056 of 145 841 patients (21.3%) were prescribed an antipsychotic medication; this rate fell during period 1 (ie, before the start of the partnership), with a mean decline of –0.53% per quarter (95% CI, –0.63% to –0.44%; P < .001) (Table 2). By the end of period 2 (2014, quarter 4), antipsychotic use had fallen further to 40 956 of 355 716 patients (11.5%) (eTable 3 in the Supplement), but the quarterly rate of decline slowed significantly from period 1 to 2 by 0.24% (95% CI, 0.09%-0.39%; P = .003).

Figure 1. Percentage of Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents Prescribed an Antipsychotic or Other Psychotropic Medication.

Antipsychotic and psychotropic prescribing overall declined both before and after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes with the exception of mood stabilizers, the use of which gradually increased throughout.

aBenzodiazepines are not included.

Table 2. Rates and Trends of Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Use per 100 Long-Stay Nursing Home Residentsa.

| Medication | Period 1 (From 2009 to Q1 of 2012) | Period 2 (From Q2 of 2012 to 2014) | Slope Change (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use, %b | Slope (95% CI) | P Value | Use, %c | Slope (95% CI) | P Value | |||

| Antipsychotics | 31 056 (21.3) | −0.53 (−0.63 to −0.44) | <.001 | 42 836 (14.6) | −0.29 (−0.39 to −0.20) | <.001 | 0.24 (0.09 to 0.39) | .003 |

| Antidepressants | 75 841 (52.0) | −0.51 (−0.60 to −0.42) | <.001 | 133 738 (45.7) | −0.17 (−0.28 to −0.06) | .004 | 0.34 (0.18 to 0.50) | <.001 |

| Mood stabilizers | 24 218 (16.6) | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.10) | <.001 | 52 358 (17.9) | 0.22 (0.18 to 0.25) | <.001 | 0.14 (0.10 to 0.18) | <.001 |

| Sedative-hypnotics (nonbenzodiazepine) | 11 767 (8.1) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | .27 | 23 772 (8.1) | −0.18 (−0.20 to −0.16) | <.001 | −0.17 (−0.20 to −0.14) | <.001 |

| Nonantipsychotic psychotropics overalld | 87 587 (60.1) | −0.40 (−0.48 to −0.33) | <.001 | 161 792 (55.3) | −0.14 (−0.24 to −0.04) | .009 | 0.26 (0.13 to 0.40) | <.001 |

| Psychotropics overalld | 94 635 (64.9) | −0.54 (−0.63 to −0.44) | <.001 | 170 651 (58.4) | −0.22 (−0.34 to −0.10) | <.001 | 0.32 (0.16 to 0.49) | <.001 |

| Benzodiazepines | NAe | NA | NA | 61 973 (19.4)f | 0.004 (−0.08 to 0.09) | .91 | NA | NA |

| Memory medicationsg | 41 403 (28.4) | −0.71 (−0.78 to −0.64) | <.001 | 56 652 (19.4) | −0.34 (−0.41 to −0.27) | <.001 | 0.37 (0.25 to 0.48) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; Q, quarter.

For a total of 637 426 patients.

Use reflects the first quarter of period 1 (145 841 patients).

Use reflects the first quarter of period 2 (292 456 patients).

Does not include benzodiazepines.

Medicare did not cover until 2013.

Use of benzodiazepines reflects the first quarter of 2013 (320 211 patients).

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine hydrochloride.

Among nonantipsychotic medications, mood stabilizers were the only medication class for which use increased. The quarterly rate of prescribing increased significantly during period 1 (0.07%; 95% CI, 0.05%-0.10%; P < .001), but the growth accelerated significantly after initiation of the partnership, with a quarterly rate increase that was 0.14% higher (95% CI, 0.10%-0.18%; P < .001) (Table 2). By the end of 2014, a total of 71 492 of 355 716 patients (20.1%) were prescribed a mood stabilizer (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Antidepressants were the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medication at all time points, although prescribing declined across both study periods and, as with antipsychotic use, the rate of decline slowed from period 1 to period 2 by 0.34% (95% CI, 0.18%-0.50%; P < .001) (Table 2).

Use of nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics was unchanged during period 1 but declined significantly during period 2 by –0.18% per quarter (95% CI, –0.20% to –0.16%; P < .001) (Table 2). Benzodiazepine prevalence was 19.9% (70 954 of 355 716 patients) in the final quarter; use did not change significantly across 2013 and 2014 when covered by Part D.

The use of nonantipsychotic psychotropic medication overall mirrored the changes in antipsychotic use, with decreasing use during the first period and slower but still declining use after initiation of the partnership (Table 2). When including antipsychotics and benzodiazepines, 214 761 of 355 716 patients (60.4%) were prescribed a psychotropic by the end of 2014 (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Prescribing of memory medications was similar to prescribing of psychotropic medications overall, with declines across both periods.

To determine whether the increase in prescribing of mood stabilizers was associated with an increase in the prevalence of seizure disorders among the cohort, we assessed the quarterly prevalence of seizure disorders, which was stable during both period 1 (0.12% per quarter; 95% CI, –0.02% to 0.26%; P = .09) and period 2 (–0.03% per quarter; 95% CI, –0.20% to 0.15%; P = .08). In addition, we may have had incomplete capture of medication use for patients with hospitalization or hospice use during their observation period.

We completed 2 additional sensitivity analyses: one excluding patients with any inpatient use (eTable 4 in the Supplement) and one censoring observation 180 days before death (ie, as a proxy for eligibility for hospice) (eTable 5 in the Supplement). In both analyses, the significance of slope changes between periods for all medication groups was unchanged.

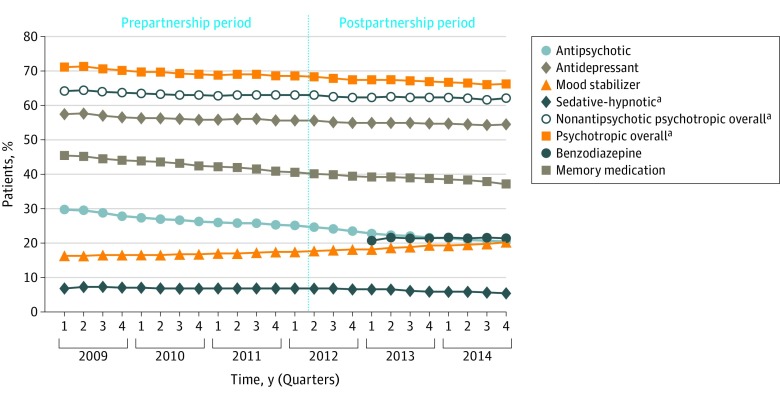

Psychotropic Prescribing Among Long-term Care Residents With Dementia

Among the subset of patients with dementia, the use of psychotropic medication was higher than among the overall study sample (Figure 2; eTable 6 in the Supplement), but the overall trends in use across the study periods were similar (Table 3). The use of antipsychotics declined through periods 1 and 2 to 27 874 of 135 646 patients (20.5%) by the final quarter; the partnership appeared to have no association with the rate of this decline (slope change, –0.003%; 95% CI, –0.14% to 0.13%; P = .96). The use of antidepressants declined at a steady rate through both periods, with no difference after initiation of the partnership.

Figure 2. Percentage of Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents With Dementia Prescribed an Antipsychotic or Other Psychotropic Medication.

Psychotropic prescribing to long-stay residents with dementia was similar to prescribing overall, with declining antipsychotic use and increasing mood stabilizer use both before and after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes.

aBenzodiazepines are not included.

Table 3. Rates and Trends of Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Use per 100 Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents With Dementiaa.

| Medication | Period 1 (From 2009 to Q1 of 2012) | Period 2 (From Q2 of 2012 to 2014) | Slope Change (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use, %b | Slope (95% CI) | P Value | Use, %c | Slope (95% CI) | P Value | |||

| Antipsychotics | 23 636 (29.9) | −0.41 (−0.49 to −0.33) | <.001 | 31 983 (24.8) | −0.41 (−0.50 to −0.32) | <.001 | −0.003 (−0.14 to 0.13) | .96 |

| Antidepressants | 45 561 (57.6) | −0.16 (−0.22 to −0.11) | <.001 | 71 883 (55.7) | −0.11 (−0.18 to −0.04) | .004 | 0.05 (−0.04 to 0.15) | .26 |

| Mood stabilizers | 12 861 (16.3) | 0.10 (0.08 to 0.13) | <.001 | 23 038 (17.8) | 0.24 (0.22 to 0.27) | <.001 | 0.14 (0.10 to 0.18) | <.001 |

| Sedative-hypnotics (nonbenzodiazepine) | 5570 (7.0) | −0.02 (−0.04 to 0.004) | .09 | 9013 (7.0) | −0.15 (−0.18 to −0.12) | <.001 | −0.13 (−0.17 to −0.09) | <.001 |

| Nonantipsychotic psychotropics overalld | 50 753 (64.2) | −0.12 (−0.17 to −0.07) | <.001 | 81 396 (63.0) | −0.08 (−0.15 to −0.02) | .01 | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.12) | .45 |

| Psychotropics overalld | 56 331 (71.2) | −0.23 (−0.29 to −0.18) | <.001 | 88 398 (68.4) | −0.19 (−0.26 to −0.12) | <.001 | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.14) | .36 |

| Benzodiazepines | NAe | NA | NA | 27 759 (20.7)f | 0.04 (−0.04 to 0.11) | .26 | NA | NA |

| Memory medicationsg | 36 025 (45.6) | −0.41 (−0.44 to −0.37) | <.001 | 51 987 (40.2) | −0.26 (−0.31 to −0.22) | <.001 | 0.14 (0.09 to 0.20) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; Q, quarter.

For a total of 325 545 patients.

Use reflects the first quarter of period 1 (79 067 patients).

Use reflects the first quarter of period 2 (129 165 patients).

Does not include benzodiazepines.

Medicare did not cover benzodiazepines until 2013.

Use of benzodiazepines reflects the first quarter of 2013 (133 904 patients).

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine hydrochloride.

Prescribing of mood stabilizers increased during both periods, and prescribing increased more rapidly in period 2 (slope change, 0.14%; 95% CI, 0.10%-0.18%; P < .001) (Table 3). By the end of 2014 (eTable 6 in the Supplement), the prevalence of use of mood stabilizers among patients with dementia (27 474 of 135 646 [20.3%]) was nearly the same as the prevalence of the use of antipsychotics (27 874 of 135 646 [20.5%]), and 29 140 of 135 646 patients (21.5%) were prescribed a benzodiazepine. When including benzodiazepines, 94 303 of 135 646 patients (69.5%) with dementia were still prescribed a psychotropic medication at the end of 2014.

Discussion

In this national Medicare sample of patients in long-term care, we found that antipsychotic use has declined since the initiation of the partnership, as previously reported.14,15,31 However, the program does not appear to have accelerated the decline that was already occurring. What has not been previously reported, to our knowledge, is the growing use of mood stabilizers, which increased more quickly after the start of the partnership.

Although the increase in the use of mood stabilizers was relatively small—an absolute increase of 2.5% from the final quarter before initiation of the partnership to the end of 2014—it was the only medication class that did not experience a decline, and the increase mirrors growth in use of mood stabilizers that Kales et al16 found after the FDA’s antipsychotic black box warnings more than 10 years ago. Soumerai et al35,36 have written extensively about the unintended consequences of policies that seek to reduce the use of specific medication classes, which frequently lead to substitution of medications. In an article from more than 20 years ago, they write, “In many cases, specific substitutions can be predicted in advance.”35(p246) Although mood stabilizers have long been seen as treatments for behavioral symptoms of dementia21,22,23 and their substitution for antipsychotics could be expected, analyses of psychotropic prescribing in nursing homes frequently do not include mood stabilizers.31,37,38,39 The MDS, the federally mandated health assessment survey used for all nursing home residents and the source of data for the partnership antipsychotic measure, collects information on the use of several psychotropic classes, but information on mood stabilizers is not captured; thus, the most likely substitute for antipsychotics has gone unobserved.40

Behavioral and environmental strategies, despite the growing evidence base and greater efficacy than antipsychotics,41,42,43 have not been routinely translated into long-term care settings. The key goal of the partnership is clearly to help correct this issue: through emphasizing reductions in antipsychotic prescribing by measuring and publicly reporting it, facilities might increase the use of evidence-based, nonpharmacologic alternatives.13 However, what is being measured and reported is prescribing of antipsychotics. Without additional resources to implement behavioral and environmental strategies, clinicians may have chosen to shift patients to alternative psychotropic classes. In addition to the psychotropics measured in our study, an investigative report highlighted the recent, rapid growth in off-label prescribing of dextromethorphan hydrobromide-quinidine sulfate for agitation in patients with dementia.44 The medication’s manufacturer specifically targeted facilities with high rates of antipsychotic use who would see dextromethorphan-quinidine “as an attractive alternative,” given the close monitoring of antipsychotic prescribing. As long as antipsychotic prescribing is the only quality measure, substitutions to bypass surveillance will continue.

There are limited longitudinal data on psychotropic prescribing in long-term care with which to compare our analysis. The available evidence suggests that use of antipsychotics was already declining prior to initiation of the partnership, as we found. Chen et al,45 using an analysis of US nursing home pharmacy dispensings in 2006, found an antipsychotic prescribing rate of 29%. This same group found that use of antipsychotics declined to 22% by 2009-2010,46 which is similar to our estimates for the same time period. However, our estimates are lower than the antipsychotic prevalence reported by the partnership.15 The partnership uses the long-stay antipsychotic measure from the MDS, which captures use of an antipsychotic within the previous 7 days regardless of the payment source, while our sample captures antipsychotic prescribing covered by Part D. During every quarter, while we found an antipsychotic prescribing rate approximately one-third lower than the use reported by CMS, both our analysis and the partnership document similar relative reductions in the prevalence of antipsychotics after the start of the partnership (15.0% to 11.5% [our analysis] and 23.8% to 19.1% [the partnership]; reductions of 23% [our analysis] and 20% [the partnership]).

In the final quarter of 2014, more than 60% of long-term stay nursing home residents were prescribed a psychotropic medication. The persistently high use of benzodiazepines is particularly concerning given their association with several adverse events in older adults, including falls,47 fractures,48,49 and impaired cognition.50 That benzodiazepines are prescribed to nearly 20% of these frail, older patients, with use even slightly higher among residents with dementia, is cause for concern.

Limitations

Our analysis has several limitations. First, we derived our cohort of long-stay nursing home residents, a population that declined slightly during the observation period,51 based on their Medicare claims, although this approach has high sensitivity (0.87) and specificity (0.96).33 Second, our sample is limited to those with continuous fee-for-service and Part D Medicare coverage. Therefore, our analysis does not include the growing population of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries or non–Part D prescriptions. Third, while we did not use MDS data as reported by the partnership, using Part D data allowed us to measure the use of mood stabilizers, which is not collected by the MDS. Finally, our analysis ends in 2014.

In light of the potential for antipsychotic substitution, the partnership should consider incorporating more comprehensive measures to capture all psychotropic use, but it is also critical to consider how to measure and incentivize the practice of true person-centered dementia care, such as evidence-based training programs for formal caregivers, such as the DICE (describe, investigate, create, evaluate) approach7 or OASIS.37 However, given the prevalence of psychosis and aggressive behavior among patients with dementia52 coupled with the possibility that some patients may not respond to even extensive behavioral or environmental interventions, patient-centered care may mean that an antipsychotic is appropriate for some patients. Although antipsychotic use in long-term care has declined significantly, it is unclear what the floor should be: as Gurwitz et al14(p119) recently asked: “How low can use go?” However, prescribing should be driven by patient need, not by nonclinical factors, such as patient race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status, nor by the particular prescribing habits of their clinician or local facility culture.

Conclusions

Use of antipsychotic medications was declining before the start of the partnership and continued to fall after its start. At the same time, prescribing of mood stabilizers, an unmeasured alternative possibly prescribed for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, has been growing. Initiatives focused on improving psychotropic prescribing for patients with dementia should monitor use of other psychotropics—including mood stabilizers—as well as consider how to measure and incentivize structured, evidence-based, nonpharmacologic alternatives. Given the barriers to increased uptake of behavioral and environmental interventions relative to simply shifting prescribing, such measurement is essential to further the primary goal of improving person-centered dementia care rather than simply encouraging a shift to prescribing alternative but unmeasured medications.

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Codes for Antipsychotic Use Denominator Exclusion and Dementia and Seizure Disorder Subanalyses

eTable 2. Psychotropic Medication Classes

eTable 3. Percentage of Long-term Stay Nursing Home Residents Prescribed an Antipsychotic or Other Psychotropic Medication (used for Figure 1)

eTable 4. Rates and Trends of Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Use per 100 Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents with No Hospitalization in Study Period (N = 449 205)

eTable 5. Rates and Trends of Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Use per 100 Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents Censored 180 days Prior to Death (N = 583 169)

eTable 6. Percentage of Long-term Stay Nursing Home Residents with Dementia Prescribed an Antipsychotic or Other Psychotropic Medication (used for Figure 2)

References

- 1.Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(5):532-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JC. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):708-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyketsos CG, Sheppard J-ME, Steinberg M, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease clusters into three groups: the Cache County study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(11):1043-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choosing Wisely, ABIM Foundation American Geriatrics Society: ten things physicians and patients should question. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-geriatrics-society/. Updated April 23, 2015. Accessed August 2, 2017.

- 5.Choosing Wisely, ABIM Foundation American Psychiatric Association: five things physicians and patients should question. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-psychiatric-association/. Updated April 22, 2015. Accessed August 2, 2017.

- 6.Ouslander J, Bartels S, Beck C, et al. ; American Geriatrics Society; American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry . Consensus statement on improving the quality of mental health care in US nursing homes: management of depression and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(9):1287-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG; Detroit Expert Panel on Assessment and Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia . Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings: recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):762-769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molinari V, Chiriboga D, Branch LG, et al. Provision of psychopharmacological services in nursing homes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B(1):57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeste DV, Blazer D, Casey D, et al. ACNP white paper: update on use of antipsychotic drugs in elderly persons with dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(5):957-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolanowski A, Fick D, Waller JL, Ahern F. Outcomes of antipsychotic drug use in community-dwelling elders with dementia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2006;20(5):217-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maust DT, Kim HM, Seyfried LS, et al. Antipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia: number needed to harm. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):438-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CMS announces partnership to improve dementia care in nursing homes. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-Releases/2012-Press-Releases-Items/2012-05-30.html. Published May 30, 2015. Accessed March 23, 2016.

- 14.Gurwitz JH, Bonner A, Berwick DM. Reducing excessive use of antipsychotic agents in nursing homes. JAMA. 2017;318(2):118-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes: antipsychotic drug use data report (July 2017). https://www.nhqualitycampaign.org/files/AP_package_20170717.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- 16.Kales HC, Zivin K, Kim HM, et al. Trends in antipsychotic use in dementia 1999-2007 [published correction appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(5):466]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):190-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peisah C, Chan DK, McKay R, Kurrle SE, Reutens SG. Practical guidelines for the acute emergency sedation of the severely agitated older patient. Intern Med J. 2011;41(9):651-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):191-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kales HC, Kim HM, Zivin K, et al. Risk of mortality among individual antipsychotics in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):71-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lott AD, McElroy SL, Keys MA. Valproate in the treatment of behavioral agitation in elderly patients with dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7(3):314-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambers CA, Bain J, Rosbottom R, Ballinger BR, McLaren S. Carbamazepine in senile dementia and overactivity: a placebo controlled double blind trial. IRCS Med Sci. 1982;10:505-506. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrmann N, Lanctôt K, Myszak M. Effectiveness of gabapentin for the treatment of behavioral disorders in dementia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20(1):90-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 2005;293(5):596-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konovalov S, Muralee S, Tampi RR. Anticonvulsants for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(2):293-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zal MH. Agitation in the elderly. Psychiatr Times. 1999;16(1). http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/dementia/agitation-elderly. Accessed August 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kernisan L. 5 Types of medication used to treat difficult dementia behaviors. https://betterhealthwhileaging.net/medications-to-treat-difficult-alzheimers-behaviors/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- 28.Lakhan SE. Alzheimer disease treatment & management. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1134817-treatment#d12. Updated December 22, 2017. Accessed February 14, 2018.

- 29.Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, et al. ; CitAD Research Group . Effect of citalopram on agitation in Alzheimer disease: the CitAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(7):682-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sepehry AA, Lee PE, Hsiung GYR, Beattie BL, Jacova C. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease with comorbid depression: a meta-analysis of depression and cognitive outcomes. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(10):793-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas JA, Bowblis JR. CMS strategies to reduce antipsychotic drug use in nursing home patients with dementia show some progress. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(7):1299-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.RTI International. MDS 3.0: quality measures: user’s manual. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS-30-QM-Users-Manual-V10.pdf. Published April 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

- 33.Yun H, Kilgore ML, Curtis JR, et al. Identifying types of nursing facility stays using Medicare claims data: an algorithm and validation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2010;10(1-2):100-110. doi: 10.1007/s10742-010-0060-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Transition to Part D coverage of benzodiazepines and barbiturates beginning in 2013. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/BenzoandBarbituratesin2013.pdf. Published October 2, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2017.

- 35.Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Fortess EE, Abelson J. A critical analysis of studies of state drug reimbursement policies: research in need of discipline. Milbank Q. 1993;71(2):217-252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Gortmaker S, Avorn J. Withdrawing payment for nonscientific drug therapy: intended and unexpected effects of a large-scale natural experiment. JAMA. 1990;263(6):831-839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tjia J, Hunnicutt JN, Herndon L, Blanks CR, Lapane KL, Wehry S. Association of a communication training program with use of antipsychotics in nursing homes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):846-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang T-Y, Wei Y-J, Moyo P, Harris I, Lucas JA, Simoni-Wastila L. Treated behavioral symptoms and mortality in Medicare beneficiaries in nursing homes with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(9):1757-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowblis JR, Lucas JA, Brunt CS. The effects of antipsychotic quality reporting on antipsychotic and psychoactive medication use. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1069-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. MDS 3.0 RAI manual. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/MDS30RAIManual.html. Accessed August 29, 2017.

- 41.Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. ; CATIE-AD Study Group . Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1525-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Courtney C, Farrell D, Gray R, et al. ; AD2000 Collaborative Group . Long-term donepezil treatment in 565 patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD2000): randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9427):2105-2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellis B, Hicken M The little red pill being pushed on the elderly. CNN. https://amp.cnn.com/cnn/2017/10/12/health/nuedexta-nursing-homes-invs/index.html. Published October 12, 2017. Accessed October 12, 2017.

- 45.Chen Y, Briesacher BA, Field TS, Tjia J, Lau DT, Gurwitz JH. Unexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(1):89-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Briesacher BA, Tjia J, Field T, Peterson D, Gurwitz JH. Antipsychotic use among nursing home residents. JAMA. 2013;309(5):440-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang PS, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J. Hazardous benzodiazepine regimens in the elderly: effects of half-life, dosage, and duration on risk of hip fracture. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):892-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneeweiss S, Wang PS. Claims data studies of sedative-hypnotics and hip fractures in older people: exploring residual confounding using survey information. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(6):948-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tannenbaum C, Paquette A, Hilmer S, Holroyd-Leduc J, Carnahan R. A systematic review of amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment induced by anticholinergic, antihistamine, GABAergic and opioid drugs. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):639-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Nursing facilities, staffing, residents and facility deficiencies, 2009 through 2015. http://files.kff.org/attachment/REPORT-Nursing-Facilities-Staffing-Residents-and-Facility-Deficiencies-2009-2015. Published July 2017. Accessed December 22, 2017.

- 52.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Codes for Antipsychotic Use Denominator Exclusion and Dementia and Seizure Disorder Subanalyses

eTable 2. Psychotropic Medication Classes

eTable 3. Percentage of Long-term Stay Nursing Home Residents Prescribed an Antipsychotic or Other Psychotropic Medication (used for Figure 1)

eTable 4. Rates and Trends of Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Use per 100 Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents with No Hospitalization in Study Period (N = 449 205)

eTable 5. Rates and Trends of Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Use per 100 Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents Censored 180 days Prior to Death (N = 583 169)

eTable 6. Percentage of Long-term Stay Nursing Home Residents with Dementia Prescribed an Antipsychotic or Other Psychotropic Medication (used for Figure 2)