Abstract

In 2011, the Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (KSNM) published clinical practice guidelines on the management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) based on a systematic review of the literature. The KSNM planned to update the clinical practice guidelines to support primary physicians, reduce the socioeconomic burden of IBS, and reflect advances in the pathophysiology and management of IBS. The present revised version of the guidelines is in continuity with the previous version and targets adults diagnosed with, or suspected to have, IBS. A librarian created a literature search query, and a systematic review was conducted to identify candidate guidelines. Feasible documents were verified based on predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The candidate seed guidelines were fully evaluated by the Guidelines Development Committee using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II quality assessment tool. After selecting 7 seed guidelines, the committee prepared evidence summaries to generate data exaction tables. These summaries comprised the 4 main themes of this version of the guidelines: colonoscopy; a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols; probiotics; and rifaximin. To adopt the core recommendations of the guidelines, the Delphi technique (ie, a panel of experts on IBS) was used. To enhance dissemination of the clinical practice guidelines, a Korean version will be made available, and a food calendar for patients with IBS is produced.

Keywords: Evidence-based practice, Irritable bowel syndrome, Practice guideline

Introduction

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder that imposes a considerable burden on health-related quality of life (QOL) worldwide. IBS patients are more likely to suffer from psychiatric diseases, including anxiety and depression, than are healthy individuals.1 Besides these psychiatric comorbidities, IBS per se impairs the daily functioning of patients. Furthermore, inadequate symptom control results in a significant economic burden due to greater use of healthcare resources.2 Population-based studies have reported that the prevalence of IBS is approximately 10% and is increasing in Asian countries.3–6 The hallmark of IBS is recurrent abdominal pain accompanying a change in bowel habits. The Rome foundation has published diagnostic criteria for IBS,7 which are commonly used. The diagnostic criteria comprise minimum requirements for gastrointestinal symptom frequency and symptom onset. To date, holistic knowledge of the pathophysiology of IBS is lacking. Additionally, no biomarkers for IBS have been validated.8 Use of invalidated diagnostic or therapeutic approaches and good access to treatment may explain the high socioeconomic burden of IBS in Korea. Therefore, organized medical guidelines on IBS based on systematic reviews of the medical literature are needed.

The Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (KSNM) published the first version of the medical guidelines for IBS in 2005, named the “Evidence-Based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment: Diagnostic/Therapeutic Guidelines for Irritable Bowel Syndrome,”9,10 which were more narrative reviews than medical guidelines. The topics related to the diagnosis of IBS were updated in 2010 in the form of a systematic review, “Diagnosis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review.”11 In 2011, the KSNM published updated medical guidelines on the treatment of IBS. These were the first organized guidelines and comprised 13 statements on relevant issues, including dietary advice, medical treatments, and psychiatric interventions.12 Since then, there have been considerable advances in the pathophysiology and management of IBS, namely a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs); understanding of the gut microbiota; and novel therapeutics. Therefore, the KSNM planned to update the organized clinical practice guidelines to support physicians for qualified medical services and reduce the socioeconomic burden of IBS.

Target Population and Audience

The revised version of the guidelines is in continuity with the previous versions. The primary target population is adult patients diagnosed with, or suspected to have, IBS. The major topics are diagnostic modalities, prevention of aggravation, medical treatments, and alternative therapies. The aim was to facilitate establishment of Korean guidelines based on an adaptation process. We considered that the audience of the guidelines would be primary physicians responsible for the care of persons with IBS-like symptoms. In addition, these guidelines may be used by medical students for learning purposes or by patients as a reference to obtain the latest medical knowledge. The literature search query used took into consideration continuity with the previous guidelines, the target patient population, and the potential audience.

Revision Process

Guidelines Development Committee

The steering committee of the KSNM in 2015 undertook the revision of the guidelines. The Working Group for Guidelines development was formed from 2 of the 16 committees of the KSNM (ie, the IBS Research Group and Medical Guideline Group). The IBS Research Group consisted of 1 institute board member (H.J.K.), a staff member (J.H.K.), and 4 general members (H.D.S., D.H.C., H.S.K., and Y.H.K.). The Medical Guideline Group consisted of 1 institute board member (H.K.J.), a staff member (K.H.S.), and 4 general members (J.E.S., Y.J.C., H.C.I., and S.E.K.). The chairman of the Medical Guideline Group (H.K.J.) oversaw and monitored the developmental process and was responsible for training the committee members. A methodologist expert in formulation of guidelines (H.J.K.) mentored the committee from the beginning of the adaptation process. In addition, a librarian from the Medical Library of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (E.A.J.) played an active role as a literature search expert. The Committee members attended the following workshops on guideline adaptation: ‘Quality evaluation of the literature according to the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II,’ ‘Literature search and the evaluation of published guidelines using AGREE II,’ ‘Methodology of clinical data extract’ (October 23, 2015), ‘The overview of guideline adaptation process’ (January 20, 2016), and ‘Medical Guideline Committee remuneration training’ (September 9, 2016).

Guideline Development Process

Principles of drafting statements

As recommended by the expert methodologist, we drafted statements reflecting the reality of Korean medicine without reference to the statements of other guidelines. To reflect the situation in Korea, we referred to related domestic publications and considered the experts’ opinion of clinicians in this field. One librarian was responsible for creating a literature search query, while each member of the committee searched domestic reports employing PubMed and KoreaMed. The population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and healthcare setting principles were employed as the basis of the statements. The present version of the guidelines comprises the following 4 major topics: diagnostic colonoscopy, diet, probiotics, and rifaximin. The data extraction tables were prepared by summarizing the literature on these 4 topics.

Systematic review

In June 2015, a document search expert searched the OVID Medicine, Medline, Medline Systemic Review, Medline Clinical Study, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, KoreaMed, KmBase, and RISS databases for relevant documents. The following search index terms were used as queries: “Irritable Bowel Syndrome” OR “Syndrome, Irritable Bowel” OR “Colon, Irritable” OR “Irritable Colon” OR “Colitis, Mucous” OR “Mucous Colitis” OR “Colonic Diseases, Functional Guideline” OR “Guidelines as Topic” OR “Guideline Adherence” OR “Patient Education as Topic” OR “Practice Guideline” OR “Practice Guidelines as Topic” OR “Clinical Guideline” OR “Clinical Practice Guideline” OR “Consensus” OR “Recommendation” OR “Workshop.” “Abdominal pain” was not used as a single query, because it was assumed that the noise factor would be too high. After completion of the search, the document search expert confirmed that all papers associated with IBS containing the keyword “Abdominal pain” had been searched. After discarding duplicates, the total number of documents retrieved was 375. Both committee members reviewed the assigned documents and independently evaluated whether they were appropriate for the adaptation of the guidelines. The inclusion criteria for the studies retrieved were as follows: (1) English or Korean language, (2) published between 2005 and 2015, (3) adult patients as the study population, and (4) use of the most recent version of the IBS guidelines, if such were extant. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) guidelines for which the evidence is unclear, (2) guidelines for hospitalized patients only, and (3) guidelines for which a revised edition was available, (4) guidelines that had themselves undergone adaptation, and (5) guidelines not developed by a committee comprised of gastroenterology specialists. A total of 8 candidate seed documents was selected for the adaptation process.

Quality evaluation and final selection of the seed guidelines

All members of the committee participated in evaluation of the quality of the candidate seed guidelines. The authors employed the AGREE II method for quality assessment. AGREE was developed to prevent the development of low-quality clinical practice guidelines and to standardize quality assessments of clinical practice guidelines.13 AGREE II complements previous versions of AGREE and is used to measure methodological rigor and transparency in the development of clinical practice guidelines. The AGREE system was developed through discussions among researchers from various countries who have extensive knowledge and experience in clinical guidelines. It consists of 23 structured core domains (scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence) and 2 items for overall evaluation. Each key item is a system that assigns a score on a 7-point Likert scale. Details are available in the AGREE II user manual.14 The K AGREE II quality evaluation tool, a Korean-language evaluation tool developed by the Steering Committee for Clinical Practice Guidelines and Korean Medical Guidelines Information Center, was used to develop the candidate seed guidelines (http://www.guideline.or.kr). In addition, the Guideline Development Committee received training on evaluation of medical care guidelines conducted by the Korean Medical Association. Based on this experience and the K-AGREE II Usage Guide, we reviewed the candidate guidelines for adaptation of the IBS guidelines.

A total of 7 candidate guidelines was categorized by a systematic literature search.12,15–20 Two independent Guideline Development Committee members were assigned to each guideline. Some of the candidate guidelines (for example, the 2015 National Institute for Clinical Excellence [NICE] Guidance18) are mere summaries with only updated content, in which case the previous version of the main body was included in the evaluation. The scale of evaluation was in accordance with the specific guidelines in the K-AGREE II user manual. The completed evaluations of the candidate seed guidelines were collected and reviewed by a supervisor (H.K.J.). If there was a difference of more than 3 points between the 2 evaluators, the 2 evaluators renegotiated with mediation by the supervisor until the difference was adjusted to less than 3 points, as suggested in the K-AGREE II user manual. Through these procedures, each domain score was calculated from the final score of each evaluator for the 6 total domains designated by K-AGREE II. The domain score is the sum of the scores of the individual evaluation items included in the corresponding domain, and the total score is converted to the percentage of the highest score assigned to the corresponding domain by the evaluators. AGREE II does not specify the type of domain score or the absolute minimum reference value. Rather, the domain score utilized is dependent on the situation in which the evaluation tool is used or the judgment of the user. Therefore, the Guidelines Development Committee has established a policy of prior consideration of the “rigor of development” domain. In other words, only guidelines with a rigor of development score of at least 50% were included as seed guidelines.15–18 Guidelines with qualifying scores in other domains were excluded from the seed guidelines if their rigor of development score was less than 50%. This is because the rigor of development domain is related to the process used to gather and synthesize the evidence and the methods used to formulate the recommendations. Therefore, we used rigor of development as the essential domain. The 4 major themes in the revised guidelines (colonoscopy, low-FODMAP diet, rifaximin, and probiotics) were revised from the data extraction tables generated using evidence summaries of the seed guidelines. Based on the 2011 Korean guidelines, subjects outside of the 4 major themes were reviewed and further revised by searching domestic documents in KoreaMed.12

Evidence summary and data extraction table

After selecting the seed guidelines, we prepared evidence summaries to generate data extraction tables, which were limited to the 4 main themes: colonoscopy, a low-FODMAP diet, probiotics, and rifaximin. Based on the method of acceptance of clinical practice guidelines proposed by Harstall et al,21 we planned to accept the seed guidelines and supplement them with expert opinions. All evidence summaries of the seed guidelines were accepted, and data extraction tables were created. Through this process, we evaluated the levels of evidence to be included in the statement. NICE, a UK methodology development center, recommends clarification of evidence-level grading for adaptation processes that reference several seed guidelines using various rating systems.22 This revision also defines 3 levels of evidence and evaluates the level of evidence for each statement (Table 1). In addition, 2 levels of recommendation are provided, independently of the evidence-based evaluation. In general, decisions on the level of recommendation are based on realistic accessibility and cost effectiveness, irrespective of the level of evidence. Data extraction tables for the 4 main topics (colonoscopy, diet, rifaximin, and probiotics) are provided in the Supplementary Table.

Table 1.

Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation

| Item | Definition |

|---|---|

| Level of Evidence | |

| A. High quality | Further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the prediction of the effects. Consistent evidence from RCTs without significant limitations or from exceptionally strong evidence derived from observational studies. |

| B. Moderate quality | Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the prediction of the effects and may change the prediction. Evidence from RCTs with significant limitations (inconsistent results, methodologic flaws, indirect or imprecise) or very strong evidence from observational studies. |

| C. Low quality | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the prediction of the effects and is likely to change the prediction. Evidence for at least one critical outcome from observational studies, case series, or RCTs with serious flaws; indirect evidence; or a consensus among experts. |

| Grade of recommendation | |

| 1. Strong | Recommendation can apply to most patients in most circumstances. The desired effect is certainly greater than the harmful effect. |

| 2. Weak | The best action may differ depending on the circumstances or patient or society values. Other alternatives may be equally reasonable. The desired effect may be slightly greater than the harmful effect. |

RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

Level of evidence and grade of recommendation

To develop an evidence rating system for each recommendation, we conducted a comprehensive quality evaluation. This evaluation considered the planning method, quality, and consistency of the study, based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessments, Development, and Evaluation criteria, to ensure a high quality of evidence across outcomes, and it consisted of 3 levels (Table 2).16,17

Table 2.

Foods With High Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols Contents

| Food | Oligosaccharides | Disaccharides | Monosaccharides | Polyols |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sauce | Chicory drinks, Ketchup, Cream pasta source, Tomato-based pasta sauce, Energy bar, Strawberry jam, Kimchi, Doenjang, Gochujang, Ssamjang, Dumpling, Dim-sum, Tom-yum soup, Thai curry paste | Honey, High-fructose corn syrup | ||

| Food additives | Inulin, Wasabi powder, FOS | Sorbitol, Mannitol, Maltitiol, Xylitol, Isomalt | ||

| Fruits | Peach, Persimmon, Watermelon | Apple, cherry, Mango, Pear, Watermelon | Apple, Pear, Prune, Cherry, Blackberries, Apricot, Avocado, Nectarine, Plum | |

| Vegetables | Garlic, Leek, Onion, Peas, Beetroot, Brussels Sprout, Chicory, Fennel, Artichokes | Asparagus, Artichokes, Sugar snap peas, Pickled onion | Mushroom, White cabbage, Cauliflower, Snow peas | |

| Milk and milk products | Milk, Yogurt, Ice cream, Custard, Soft cheeses | |||

| Grains and cereals | Wheat, Rye, Barley | |||

| Nuts and seeds | Almonds, Pistachios | |||

| Legumes | Legumes, Chickpeas, Lentils |

FODMAP, fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols; FOS, fructooligosaccharides.

Recommendations were graded as strong or weak. A strong recommendation was defined as one with positive effects considerably greater than its negative effects, expected effects that are likely to be obtained if users follow the instructions, and results that are not expected to change in the future. A weak recommendation was defined as one with inconsistent results that may not be reproducible in future studies.

Delphi agreement process for adoption of recommendations

To adopt the core recommendations of the guidelines, the Delphi technique, which is a panel of experts on IBS, was used. The panel was selected by former or current members of the KSNM Steering Committee and the faculty of the Gastroenterology Departments of university hospitals. The background material was presented to the panels in writing or by email. This initial information was accompanied by tables of results obtained from the main clinical trials, along with the data extraction tables prepared by the Guideline Development Committee. The questionnaire was drafted in English with the grade of recommendation and level of evidence for each statement attached. The possible responses to the questions were as follows: ‘I agree completely,’ ‘I agree mostly,’ ‘I agree partially,’ ‘I disagree mostly,’ ‘I disagree completely,’ or ‘I am not sure.’ Panelists able to participate in face-to-face surveys were allowed a response time of approximately 30 minutes. Panelists who were unable to participate in face-to-face surveys were emailed for 2 weeks. The acceptable response rate was not specified. If the time limit specified in the email was exceeded, no more responses were accepted. Consensus was defined by aggregating the final responses if the combined percentage of ‘I agree completely’ and ‘I agree mostly’ was more than 50%. If a consensus was not reached, all panels responding to the recommendation were emailed to determine the issue on which they disagreed. Recommendations that failed to gain a consensus were subjected to 2 further rounds of the Delphi technique. After a series of written surveys and one online survey, all 4 key recommendations gained consensus. The result of the Delphi technique is presented at the bottom of each of the 4 core recommendations.

Internal and external reviews

The members of the Guideline Development Committee conducted an internal review during 2 online and offline meetings. Additional amendments were made and subjected to additional internal review by the executives of the KSNM. The Korean Society of Gastroenterology and Korean Psychiatric Association each recommended a member who would act as an external reviewer.

Dissemination of the guidelines and revision plans

The developed guidelines will be listed under ‘Clinical practice guidelines’ on the official website of the Korean Society of Gastroenterology. In addition, we plan to use the updated guidelines in conferences and medical meetings and to deliver lectures in hospitals and institutes. We will also generate a Korean-language summary of the key points, together with a food calendar. The diet is the major issue in practice; therefore, the food calendar is provided as a separate Supplementary Table. Considering the national health insurance standard, which is the main external barrier to the recommendation, it reviewed the feasibility within the national insurance standard. This amendment will be revised 6 years after its publication in 2011 and subsequently on a similar cycle (or according to the judgement of the KSNM executives following identification of research that would lead to major changes in practice). The relevant committee of the KSNM will be responsible for the revision work.

Editorial independence

The revision meeting was funded by the KSNM alone. No organization or individual influenced the content of the guidelines. The authors of any studies or proposals on the drugs included in the guidelines were notified in advance and were verified before the revision. No member of the working team or committee had a conflict of interest.

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Definition of irritable bowel syndrome

IBS is a chronic, recurrent symptom complex, which includes abdominal pain or discomfort, changes in bowel habit, and bloating for at least 6 months.17,18 The final diagnosis of IBS is based on the exclusion of organic diseases that would explain the symptoms and the absence of endoscopic abnormalities. The Rome definition is used both clinically and for research purposes. According to the Rome IV definition, IBS is defined by recurrent abdominal pain on at least 1 day per week on average, for the past 3 months, that is associated with 2 or more of the following symptoms: abdominal pain related to defecation, a change in bowel frequency, and a change in stool form.7 However, this definition is not always applicable in a clinical setting. Therefore, we adopted a broader definition in these guidelines.

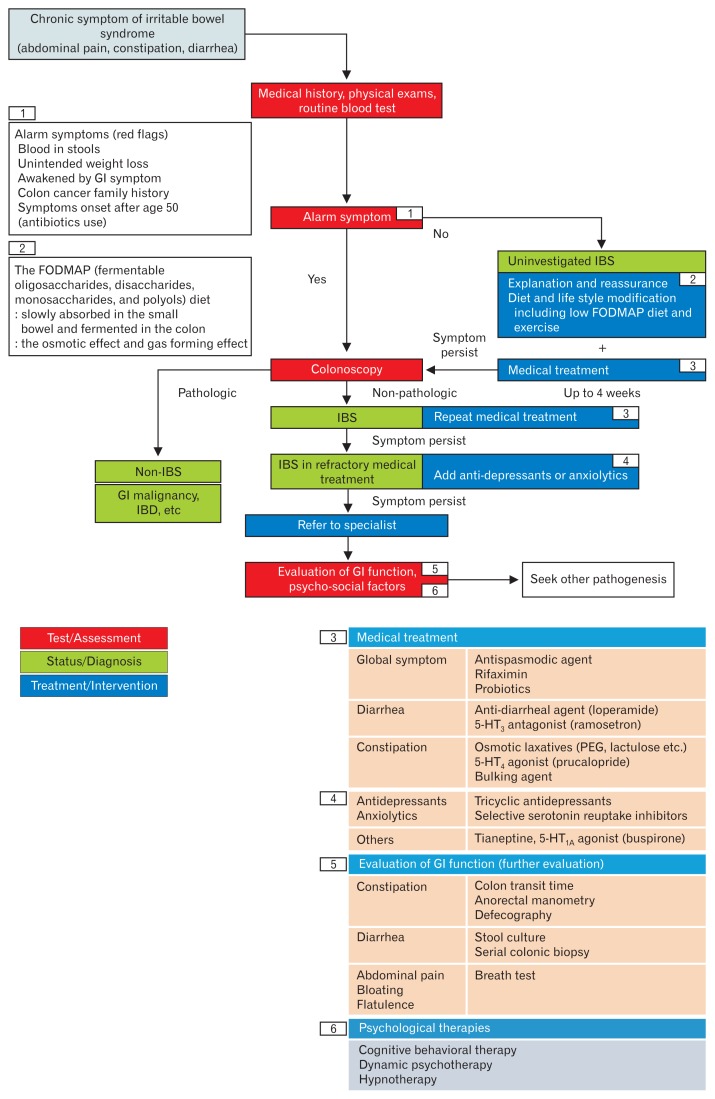

To help the primary care physician understand the standard management of IBS, the guideline development committee suggested the clinical algorithm (Figure). Considering the preference of some patients who prefer non-drug management (diet, physical activity), this life style modification (or combination of pharmacotherapy) locates in the initial management. The definition of refractory IBS, and when to refer to a gastrointestinal specialist, is basically defined by the judgment of the primary care physician. Also, this algorithm is only a general proposal, and there is no legal or medical basis to force to follow it.

Figure.

Suggested diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). GI, gastrointestinal; FODMAP, fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Colonoscopy

1. Statement: Colonoscopy may be considered in patients with alarm symptoms, eg, rectal bleeding, unexplained weight loss, change in bowel habits persisting after age 50 years, or a family history of bowel cancer.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: B

Experts’ opinions: completely agree (37.5%), mostly agree (47.5%), partially agree (10.0%), mostly disagree (2.5%), completely disagree (2.5%), and not sure (0.0%).

IBS usually can be diagnosed according to its characteristic features.23,24 The Rome criteria are reliable only when there is no other organic or metabolic explanation for the symptoms.17 However, the accuracy of a diagnosis based purely on the presenting gastrointestinal symptoms is a concern for practicing physicians. Laboratory tests, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and stool tests for microorganisms, do not increase the diagnostic yield for IBS.25,26 However, symptoms plus negative alarm features have a high predictive value for diagnosing IBS.27 Thus, these diagnostic tests should not be included in the routine evaluation of IBS, and testing should be individualized depending on factors such as age, sex, family history of gastrointestinal disease, presence of stress or other psychological factors, specific symptom predominance, symptom duration and severity, presence of non-IBS symptoms, and test availability and cost.28

The diagnostic yield of colonoscopy among IBS patients is very low.29,30 However, certain “alarm signs” (unexplained weight loss, blood in the stool, anemia, and a recent change in bowel habits) call for special consideration of other disorders before symptoms can be attributed to IBS.18,27,31,32 In these cases, colonoscopy has diagnostic value, not only for excluding organic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy but also for microscopic colitis. Biopsies of different segments of the colon may be required for patients with chronic diarrhea to rule out microscopic colitis.33

Diet

2. Statement: A low-fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols diet, which restricts dietary short-chain carbohydrates, is effective in reducing the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: C

Experts’ opinions: completely agree (5.0%), mostly agree (67.5%), partially agree (25.0%), mostly disagree (2.5%), completely disagree (0.0%), and not sure (0.0%).

FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) in the diet can trigger or exacerbate gastrointestinal symptoms (particularly abdominal pain, bloating, distension, and diarrhea) in IBS patients, while a low-FODMAP diet significantly ameliorates these symptoms. However, FODMAPs do not induce gastrointestinal problems in healthy persons.34,35 Ingested FODMAPs increase the osmotic effect, are slowly absorbed in the small bowel, and are fermented by the colonic microbiota. This results in increased levels of intraluminal fluid and gas in the small bowel and colon, which cause loose stools, bloating, abdominal distension, and abdominal pain in IBS patients with visceral hypersensitivity.36 It is also noteworthy that the significantly increased intraluminal osmosis can be induced only if a huge, non-physiological dose of FODMAPs are given, whereas the differences achievable by reducing dietary FODMAPs do not influence fecal water content and do not change the character of the stools.34 The common food sources of FODMAPs are shown in Table 2.36,37

An elimination diet to prevent triggering of IBS symptoms is recommended for management of IBS.12 Restriction of dietary short-chain carbohydrates (ie, FODMAPs) improved IBS symptoms in one controlled trial38 and 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs).34,39 Three studies reported significant improvement of abdominal pain and bloating but not flatulence and diarrhea or constipation.34,38,39 The side effects of a low-FODMAP diet were not reported, as the durations of these studies were less than 4 weeks. Thus, studies evaluating the long-term outcomes and adverse effects of a low-FODMAP diet are warranted.

East and Southeast Asian foods high in FODMAPs include Korean foods (kimchi, doenjang, ssamjang, and mandu), Japanese foods (gyozas), Thai foods (tom yum soup and some curry paste), Chinese foods (dim sum, wonton, man tou, red been sweet soup, and green bean soup), and Vietnamese foods (pho topped with onion).37,40

Physical Activity

3. Statement: Physical activity may be helpful in improving the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: C

Not voted in the revised edition

Data regarding the effectiveness of physical activity in alleviating IBS symptoms are limited. In one RCT, 12 weeks of treatment with physical activity (20–60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensive physical activity on 3 to 5 days per week) improved the IBS-Severity Scoring System score significantly in patients with IBS.41 Moreover, the frequency of increased IBS symptom severity was significantly higher in the control group than in the physical activity group. In the physical activity group, the IBS-QOL scores improved significantly in the dimensions of emotion, sleep, energy, physical functioning, social, and physical role at the 12-week visit relative to those at baseline. In another RCT, 12-week exercise therapy significantly improved constipation, but not other IBS symptoms, in 56 IBS patients.42

Although there is no clear evidence of the efficacy of other behavioral modifications, such as eliminating alcohol or smoking, getting good sleep, and taking rest, in reducing IBS symptoms, a reduction in the risk of IBS is plausible.20

Physical activity and other behavioral modifications may be recommended for improving IBS symptoms.

Bulking Agents

4. Statement: Bulking agents can provide overall symptom relief in irritable bowel syndrome patients.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: B

Not voted in the revised edition

Bulking agents are fiber supplements, such as psyllium (ispaghula husks), calcium polycarbophil, methylcellulose, and bran. Soluble fiber can provide overall symptom relief in IBS patients, but possibly only in patients with constipation-dominant IBS (IBS-C), although most trials did not specify the type of IBS evaluated.15 In a randomized placebo-controlled trial of 275 patients with IBS, treatment with psyllium for 3 months significantly improved abdominal pain or discomfort, but bran did not.43 A recent meta-analysis of 14 RCTs found that soluble fiber such as ispaghula husk was better than placebo with respect to relieving the symptoms of IBS (relative risk [RR], 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73–0.94; number needed to treat [NNT] = 7; 95% CI, 4–25), but insoluble fiber such as bran was ineffective (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.79–1.03) and actually worsened IBS symptoms.44 Bulking agents can cause bloating, gas, and abdominal discomfort or pain in some IBS patients.45

Osmotic Laxatives

5. Statement: Osmotic laxatives can increase stool frequency in constipation-dominant irritable bowel syndrome patients.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: B

Not voted in the revised edition

Osmotic laxatives are poorly absorbed by the gut and induce water secretion into the intestinal lumen, which softens and eases passage of the stool. Osmotic agents, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), lactulose, sorbitol, and magnesium hydroxide, are inexpensive and have been validated in RCTs for chronic constipation.

PEG is a water-soluble polymer that is minimally absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and behaves as an osmotic laxative. PEG has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chronic constipation. A meta-analysis reported that PEG significantly increased the number of stools per week in patients with chronic constipation.46 However, PEG has not been extensively evaluated in patients with IBS-C. In one RCT involving patients with IBS-C, PEG was superior to placebo for relief of constipation but did not show a beneficial effect on other symptoms of IBS.47 PEG may be useful in patients with IBS-C for specific symptom relief or as an adjunct treatment; moreover, PEG has few adverse effects and a low cost. Lactulose is an osmotic laxative used to treat chronic constipation. However, lactulose is not recommended for treatment of constipation associated with IBS, because its fermentation in the gut may worsen bloating and gas distension.48

Antispasmodic Agents

6. Statement: Antispasmodics are effective in treating abdominal discomfort and pain in irritable bowel syndrome patients.

Grade of recommendation: 1

Level of evidence: B

Not voted in the revised edition

Antispasmodics, including smooth muscle relaxants, anti-muscarinic agents, anticholinergics, and calcium channel blockers, have long been used to treat IBS. Antispasmodic agents reduce the abdominal pain associated with IBS by inhibiting the postprandial contractility pathways in the gut wall and improve bowel habits by increasing the colonic transit time, which reduces the frequency of stool passage, particularly in diarrhea-dominant IBS (IBS-D). In a meta-analysis, antispasmodics showed a beneficial effect on abdominal pain, global symptom assessment, and symptom scores.49,52 The results of RCTs of antispasmodics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antispasmodics Used for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Treatment

| Drug | Starting dosage | Maximum dosage | Representative adverse effects | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium channel blocker | Alverine citrate | 60–180 mg/day | 360 mg/day | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, headache | Only combination with simethicone reduced abdominal pain and discomfort compared to placebo |

| Mebeverine | 300 mg/day | 405 mg/day | Urticaria, angioedema, anaphylaxis | Superior in controlling abdominal pain compared with placebo | |

| Otilonium bromide | 60 mg/day | 120 mg/day | Increased intraocular pressure | Reduced abdominal pain frequency and bloating and improved stool frequency and patient global assessment compared with placebo; lower symptom recurrence after treatment | |

| Pinaverium bromide | 150 mg/day | 300 mg/day | Abdominal distension, abdominal pain, diarrhea | Superior in improving global symptoms compared with placebo | |

| Peppermint oil | 0.6 mL/day | - | Heartburn | Superior in controlling abdominal pain | |

| Anticholinergic agent | Hyoscine | 30 mg/day | 60 mg/day | Dry mouth, tachycardia, impaired vision | Superior in controlling abdominal pain |

| Cimetropium | 100 mg/day | 150 mg/day | Dry mouth, nausea, vomiting, constipation | Superior in controlling abdominal pain | |

| Miscellaneous | Trimebutine | 300 mg/day | 600 mg/day | Dry mouth, constipation, diarrhea | Superior in controlling abdominal pain |

| Phloroglucinol | 160 mg/day | - | Dry mouth, dizziness, and blurred vision | Significantly improved subjects’ global assessment and decreased stool frequency |

Alverine citrate is a selective serotonin subtype 1A receptor (5-HT1A) antagonist that inhibits calcium uptake and modulates smooth muscle activity. Alverine, in combination with simethicone, resulted in a significant reduction in abdominal pain and discomfort in a large placebo-controlled trial.53 Mebeverine is a musculotropic agent with antispasmodic activity that regulates bowel function. Since the 1960s, mebeverine has been used to treat IBS and has shown promise in several clinical trials involving IBS patients. However, in a recent systematic review of 8 RCTs, mebeverine treatment did not result in significant clinical improvement or relief of abdominal pain compared with a placebo.54,55 Otilonium bromide is a poorly absorbed antispasmodic agent found to be effective in reducing pain and improving defecation alterations in IBS patients in placebo-controlled trials.56 Pinaverium bromide has been used to manage the symptoms of IBS. In a recent review of RCTs, pinaverium significantly reduced abdominal pain, improved stool consistency, and reduced defecation straining and urgency in IBS patients.57 Phloroglucinol is a non-specific antispasmodic that reduced pain in IBS patients in a placebo-controlled trial.58 The incidence of adverse events was significantly higher among those taking antispasmodics as compared with a placebo; the most frequent adverse events were dry mouth, dizziness, and blurred vision. No serious adverse events were reported.59

Anti-diarrheal Agents

7. Statement: Loperamide is recommended to improve stool consistency and decrease bowel frequency in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome patients.

Grade of recommendation: 1

Level of evidence: C

Not voted in the revised edition

Loperamide is a synthetic opioid receptor agonist that stimulates inhibitory presynaptic receptors in the enteric nervous system, resulting in inhibition of peristalsis and secretion. Loperamide is the most commonly used drug for multiple symptoms of IBS, particularly diarrhea. The starting dose of loperamide varies from 2 mg once daily to twice daily, and doses of up to 12 mg daily are reportedly safe.60 Although the efficacy of as-needed loperamide for IBS has not been evaluated, it is commonly used in clinical practice. In the late 1980s, double-blinded RCTs revealed that loperamide improved stool consistency and frequency but not pain or global symptoms in IBS patients.62,63 However, the overall quality of evidence was very low due to the small sample size, serious risk of bias, and imprecision. The adverse events of loperamide were similar to those of placebo; however, nausea, cramping, and constipation frequently occur in the general population.64

Serotonin Subtype 3 Receptor Antagonists

8. Statement: Ramosetron, a serotonin subtype 3 receptor antagonist, improves stool consistency, abdominal pain/bloating, and health-related quality of life in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome patients.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: A

Not voted in the revised edition

5-HT3 receptors play an important role in visceral pain, and 5-HT3 receptor antagonists decrease painful sensations from the gut and slow intestinal transit.65,66 5-HT3 receptor antagonists reportedly slow colonic transit, blunt the gastrocolonic reflex, and reduce rectal sensitivity and postprandial motility,66,67 and are effective for the treatment of IBS-D.

Ramosetron is a novel potent and selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, which is reportedly useful in patients with IBS-D.68 To date, 6 RCTs of ramosetron in patients with IBS-D have been reported.69–74 In 2 randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies involving 957 male and female patients with IBS-D,69,70 ramosetron 5 μg once daily increased the monthly responder rate of patient-reported global assessment of IBS symptom relief compared with a placebo. Ramosetron was also as effective as mebeverine in male patients with IBS-D. In a recent RCT involving 343 male patients with IBS-D,71 ramosetron 5 μg once daily was effective in improving stool consistency, relieving abdominal pain/discomfort, and improving health-related QOL. In 2 recent randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies involving 985 female patients with IBS-D,73,74 ramosetron 2.5 μg once daily improved abdominal pain/discomfort, stool consistency, and overall IBS symptoms. Regarding safety, ramosetron is associated with a lower incidence of constipation than are other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and is not associated with ischemic colitis.69–72 In a recently published long-term phase III study,75 no serious adverse event related to ramosetron, specifically ischemic colitis, was observed in patients who received 2.5 or 5 μg ramosetron. However, constipation occurred in 19.7% of patients given 2.5 μg and in 10.5% of patients given 5 μg ramosetron. In summary, ramosetron is effective, with long-term safety, for the treatment of male and female patients with IBS-D. Thus, ramosetron shows promise for treating patients with IBS-D.

Serotonin Subtype 4 Receptor Agonists

9. Statement: Prucalopride, a serotonin subtype 4 receptor agonist, may improve stool consistency, abdominal pain/bloating, and health-related quality of life in constipation-dominant irritable bowel syndrome patients whose bowel symptoms are refractory to simple laxatives.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: C

Not voted in the revised edition

Serotonin influences the secretory, motor, and sensory functions of the gastrointestinal tract.76 5-HT4 receptors are distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract, and stimulation of these receptors enhances intestinal secretion, augments the peristaltic reflex, and increases gastrointestinal transit.77,78 Prucalopride is a novel gastrointestinal prokinetic agent and a high-affinity, highly selective 5-HT4 agonist.79 Prucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation.80 Prucalopride 2 mg once daily for 12 weeks was more efficacious than a placebo in improving stool frequency and stool consistency, decreasing the need for rescue medications and reducing symptoms of constipation in Asian and non-Asian women, and was safe and well-tolerated.81–85 Previous nonselective 5-HT4 agonists (cisapride and tegaserod) are associated with significant interactions with other receptors, leading to adverse cardiovascular events and resulting in withdrawal of these drugs from the market.86 However, serious cardiac toxicity has not been reported in patients taking prucalopride. Because no data on the efficacy or safety of these agents for the treatment of IBS are available, when bowel symptoms are refractory to simple laxatives, prucalopride can be considered in patients with IBS-C.

Antibiotics

10. Statement: Rifaximin may be effective in reducing global symptoms of diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: B

Experts’ opinions: completely agree (7.5%), mostly agree (42.5%), partially agree (45.0%), mostly disagree (2.5%), completely disagree (0.0%), and not sure (2.5%).

Rifaximin is a poorly absorbable rifamycin derivative that inhibits bacterial transcription. The bioavailability of rifaximin is very low because of its poor absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, which reduces the risk of serious systemic side effects. The poor absorption of rifaximin enables an effective concentration to be maintained in the intestinal lumen. A recent review suggests that a subtype of IBS, referred to as small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth, occurs secondary to an intestinal bacterial infection,87 and changes in the spectrum of small intestinal bacteria is reportedly associated with the pathogenesis of IBS.88–90 These provide a basis for considering the use of antibiotics in IBS patients. Traditional antibiotics, such as neomycin, are effective against IBS.91 However, antibiotics have not been used extensively to treat IBS because of the risks of side effects and the development of antibiotic resistance. Several double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled trials and systemic literature reviews show that rifaximin is effective in improving various IBS symptoms. Four recent RCTs have demonstrated the beneficial effects of rifaximin for IBS-D.92–95 These trials involved 3837 patients and compared rifaximin with placebo for the treatment of patients with non-constipation IBS, the majority of whom had IBS-D. In 2 small RCTs, the active treatment groups received rifaximin 400 mg twice a day (bid) or 3 times a day (tid) daily for 10 days,92,93 while in 2 large RCTs, the patients took rifaximin 550 mg tid for 2 weeks.94,95 Four RCTs with dichotomous endpoints support the efficacy of rifaximin in patients with IBS-D and those with relapsing symptoms of IBS-D, and repeat rifaximin treatment was efficacious and well tolerated.92–95 The overall quality of rifaximin was rated as moderate.96 In contrast to other treatments for IBS, which were taken daily, rifaximin was administered for a short duration. In addition, the meta-analysis by Menees et al97 noted that studies involving older patients and a higher proportion of women than men reported higher response rates. Rifaximin is effective for reducing abdominal pain, bloating, and improving stool consistency. However, the efficacy of rifaximin may decrease over time; therefore, repeated treatment may be necessary. Rifaximin has few side effects and a low cost.

Probiotics

11. Statement: Probiotics may be considered to relieve global symptoms, bloating, and flatulence in irritable bowel syndrome patients.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: C

Experts’ opinions: completely agree (7.5%), mostly agree (55.0%), partially agree (27.5%), mostly disagree (7.5%), completely disagree (0.0%), and not sure (2.5%).

Probiotics improve mucosal integrity and restore the intestinal barrier by regulating the gut microbiota. Global symptoms, bloating, and flatulence have been assessed in 23 RCTs involving 2575 patients;15 the results indicated that probiotics were significantly better than the placebo (RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.70–0.89), with an NNT of 7 (95% CI, 4.00–12.50). However, there was significant heterogeneity among the included studies. The use of a variety of preparations complicates the assessment of probiotics. Combination probiotics, as well as formulations based on species of the genera Bifidobacterium, Escherichia, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus, have been investigated in 24 trials, involving 25 comparisons and 2,001 patients who reported an improvement in global IBS symptom scores or abdominal pain scores. Probiotics significantly reduced symptoms, with no significant heterogeneity. A further 17 trials involving 18 comparisons and 1446 patients reported that probiotics significantly reduced bloating symptom scores, albeit with significant heterogeneity. In 10 trials, flatulence scores were significantly decreased by probiotics compared with the placebo, with no significant heterogeneity. Two large, placebo-controlled trials of Bifidobacterium infantis98,99 at 1 × 108 CFU/mL for 4 weeks improved bloating and bowel function compared with the placebo. The improvement in global symptoms exceeded that of the placebo by more than 20% (P < 0.02).98 Five randomized placebo-controlled trials reported that probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus plantarum, and VSL#3, which contains a mixture of lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, and a Streptococcus strain) improved some symptoms, mainly bloating and flatulence.100–104

Several RCTs of probiotics have been performed in Korea. Treatment with Bacillus subtilis and Streptococcus faecium for 4 weeks was significantly superior to the placebo in reducing the severity and frequency of abdominal pain (P = 0.044 and P = 0.038, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in bloating, frequency of gas expulsion, frequency of defecation, or hardness of stools before and after the treatment.105 Saccharomyces boulardii at 210 live cells daily for 4 weeks resulted in a greater improvement in IBS-QOL scores than did the placebo in patients with IBS-D or IBS-mixed (15.4% vs 7.0%; P < 0.05).106 A probiotic mixture (Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium longum, and Streptococcus thermophiles) provided adequate relief of overall IBS symptoms and improved stool consistency in IBS-D patients but had no significant effect on individual symptoms.107

Agents that restore the balance of the colonic microbiota, such as probiotics or poorly absorbed antibiotics, show promise for post-infectious IBS. Further high-quality RCTs are needed to recommend effective evidence-based treatments for patients with post-infectious IBS.87 The optimum strains, species, or combinations thereof, and the appropriate dose and duration, are unclear. Overall, however, probiotics are considered beneficial for IBS, as they are inexpensive and safe.

Antidepressants

12. Statement: Tricyclic antidepressants may be considered in patients with irritable bowel syndrome for abdominal pain relief and global symptom improvement.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: A

Not voted in the revised edition

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can be considered in IBS patients whose symptoms are not improved by laxatives, loperamide, or antispasmodic agents and can provide abdominal pain relief and improve the overall symptoms. Antidepressants, such as TCAs and selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), influence the CNS, and peripheral nervous system and thus could be effective against IBS, the pathogenesis of which has a neurological component.108 Indeed, TCAs reportedly ameliorate IBS symptoms.51,109–116 RCTs that compared TCAs with placebo or “usual management” reported that TCAs significantly improved overall IBS symptoms (NNT=4; 95% CI, 3–8).115 A recent meta-analysis of 799 patients showed that antidepressants can significantly improve the global symptoms of IBS (RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.08–1.77).116 Indeed, in a subgroup analysis, TCAs (n = 428) improved the global symptoms of IBS (RR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.07–1.71).116 TCAs and SSRIs are not effective in IBS patients with depression. However, a smaller dose of antidepressants than that used for depression is required to improve the symptoms of IBS.

The clinical efficacy of different types of antidepressant is unclear. Antidepressants are likely more useful for IBS-D, which is characterized by bowel movements induced by increased anticholinergic activity.109 TCAs are generally more effective against IBS-D.117 A study of only IBS-D patients reported that amitriptyline results in a significant reduction in the incidence of loose stools and the feeling of incomplete defecation compared with a placebo (P < 0.05).111 However, another study reported that TCAs have similar efficacy against IBS D, IBS-C, and IBS-mixed.118 Further large-scale studies of the clinical effects of antidepressants in IBS patients are thus needed.

Antidepressants are regarded as relatively safe;119 the RR of adverse effects from antidepressants was higher than that from a placebo in a meta-analysis of 7 studies (RR of experiencing any side effect, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.18–2.25).120 The number needed to harm was 9 (95% CI, 5–111). No serious adverse events were recorded, but the frequencies of drowsiness and dry mouth were higher in IBS patients taking TCAs than in those taking a placebo. However, there is a risk of QT interval prolongation in patients taking TCAs.16 Therefore, 5–10 mg amitriptyline should initially be taken once daily at night. The dosage may be increased incrementally but should not exceed 30 mg (Table 4).18

Table 4.

Antidepressants Used for Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

| Psychotropic | Drug | Starting dosage | Maximal dosage | Adverse effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCAs | Amitriptyline | 10–25 mg/day | 30 mg/day | Dry mouth, constipation, difficulty sleeping, difficulty urinating, sexual difficulties, headache, nausea, dizziness. and/or drowsiness | Begin with low dose (at bedtime) and titrate by response |

| Imipramine | 25 mg/day | 50 mg/day | |||

| Desipramine | 50 mg/day | 150 mg/day | |||

| Trimipramine | 50 mg/day | - | |||

| SSRIs | Paroxetine | 10–20 mg/day | 50 mg/day | Agitation, dizziness, nausea, headache, vivid dreams, sleep disturbances, sexual difficulties, and/or diarrhea | Begin with low dose and titrate by response |

| Citalopram | 20 mg/day | 40 mg/day | |||

| Fluoxetine | 20 mg/day | - |

TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

13. Statement: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be considered to improve the sense of well-being of patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Grade of recommendation: 2

Level of evidence: B

Not voted in the revised edition

The efficacy of SSRIs against IBS is controversial. In 7 RCTs involving 356 patients, SSRIs reduced IBS symptoms compared with a placebo (NNT=4 ; 95% CI, 2.5–20).120 In addition, SSRIs significantly improved IBS symptoms compared with a placebo (NNT=3.5; 95% CI, 2–14).115 However, a recent meta-analysis of 5 RCTs involving 371 patients reported that SSRIs did not exert a significant effect on the global symptoms of IBS (RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 0.83–2.28).116 In addition, SSRIs did not improve abdominal pain or enhance the QOL of the IBS patients. SSRIs promote peristalsis and thus are considered to be more effective for IBS-C than IBS-D.117 A recent study in Korea reported that the selective 5-HT reuptake enhancer tianeptine was not inferior to the TCA amitriptyline in providing global relief of IBS symptoms (abdominal pain/discomfort, stool frequency/consistency, QOL, and overall treatment satisfaction) in patients with IBS D.121 Therefore, SSRIs may provide some degree of symptom relief in a subset of patients with IBS.

SSRIs are more tolerable and have fewer side effects compared with TCAs, and the risk of critical adverse events is minimal. Several IBS guidelines recommend SSRIs for treatment of IBS.15,17,18,115 Therefore, SSRIs may be considered for IBS patients in whom TCAs are ineffective.18 Further well-designed RCTs are required to evaluate the efficacy of SSRIs in IBS patients.

Others

Chloride channel activators

Activation of chloride channels at the apical surface of the intestinal epithelium is the major mechanism of secretory diarrhea (eg, cholera). Two placebo-controlled trials have assessed the efficacy of lubiprostone in IBS-C patients.122,123 Interestingly, lubiprostone exerted a greater effect on abdominal pain and bowel movement than did the placebo.122 A phase III trial demonstrated an 8% therapeutic gain for lubiprostone over placebo in IBS-C patients, with similar adverse events.123 However, these trials have been criticized for not including an Food and Drug Administration responder end point, and the therapeutic gain was not clinically important.

Psychological therapies

Psychological therapies include cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, dynamic psychotherapy, and hypnotherapy. Several RCTs reported that psychological therapies provide significant relief of the symptoms of IBS.109,124–130 Psychological therapies for IBS have an efficacy similar to medical therapies in terms of improving the symptoms or QOL of IBS patients (NNT=4).15,115 A recent meta-analysis of 41 trials involving 2290 patients reported that psychological therapies reduce gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS at 1–6 months and 6–12 months after treatment.131 However, these studies had limitations, including a low methodological quality, relatively few patients, and no consideration of the heterogeneity of IBS, ie, IBS-D, IBS-C, and IBS-mixed.132 In addition, conducting comparative or double-blinded trials of psychological therapies is difficult; therefore, we should pay much attention to when the results are directly applicable to the real clinical practice.124 Cognitive behavioral therapy (NNT=3; 95% CI, 2–6),109, 124,129,130 dynamic psychotherapy (NNT=3.5; 95% CI, 2–25),126,127 multi-component psychological therapy (NNT=4; 95% CI, 3–7),125,133 and hypnotherapy (NNT=4; 95% CI, 3–8)128,134 were effective against the symptoms of IBS. Unfortunately, stress management and mindfulness training did not have a significant effect on symptoms of IBS, and the effect of relaxation therapy is controversial.124,131 Psychological therapies have no significant adverse effects.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Eun Ae Jung has contributed in the systematic review and the extraction of recommendations. Sam Ryong Jee and Kyung Sik Park supervised the manuscript.

Footnotes

Note: To access the supplementary table mentioned in this article, visit the online version of Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility at http://www.jnmjournal.org/, and at https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm17145.

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Kyung Ho Song have contributed in writing and editing the paper as the first author; Kyung Ho Song, Hye-Kyung Jung, Hyun Jin Kim, Hoon Sup Koo, Yong Hwan Kwon, Hyun Duk Shin, Hyun Chul Lim, Jeong Eun Shin, Sung Eun Kim, Dae Hyeon Cho, and Jeong Hwan Kim have contributed in the systematic review, the extraction of recommendations, and writing the paper; Hyun Jung Kim has contributed in the development of guideline as the methodology expert; and Hye-Kyung Jung has designed the development of guideline as the chairman of the committee.

References

- 1.Ballou S, Keefer L. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on daily functioning: Characterizing and understanding daily consequences of IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12982. Published Online First: 25 Oct 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buono JL, Mathur K, Averitt AJ, Andrae DA. Economic burden of inadequate symptom control among US commercially insured patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. J Med Econ. 2017;20:353–362. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2016.1269016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SY, Lee KJ, Kim SJ, Cho SW. Prevalence and risk factors for overlaps between gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia, and irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Digestion. 2009;79:196–201. doi: 10.1159/000211715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YYWA, Tan HJ, Chua AS, Whitehead WE. Rome III survey of irritable bowel syndrome among ethnic Malays. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6475–6480. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i44.6475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siah KT, Wong RK, Chan YH, Ho KY, Gwee KA. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Singapore and its association with dietary, lifestyle, and environmental factors. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:670–676. doi: 10.5056/jnm15148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miwa H. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Japan: internet survey using Rome III criteria. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2008;2:143–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1393–1407. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JH, Lin E, Pimentel M. Biomarkers of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:20–26. doi: 10.5056/jnm16135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee OY, Yoon CO. Review: evidence based guideline for diagnosis and treatment: diagnostic guideline for irritable bowel syndrome. Kor J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;11:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park HJ. Review: evidence based guideline for diagnosis and treatment: therapeutic guideline for irritable bowel syndrome. Kor J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;11:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JH, Byeon JS, Shin WG, et al. Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:308–315. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2010.55.5.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon JG, Park KS, Park JH, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;57:82–99. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2011.57.2.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AGREE Collaboration. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–E842. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(suppl 1):S2–S26. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberg DS, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ, Sultan S American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1146–1148. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–1798. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hookway C, Buckner S, Crosland P, Longson D. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2015;350:h701. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gwee KA, Bak YT, Ghoshal UC, et al. Asian consensus on irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1189–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukudo S, Kaneko H, Akiho H, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:11–30. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harstall C, Taenzer P, Angus DK, Moga C, Schuller T, Scott NA. Creating a multidisciplinary low back pain guideline: anatomy of a guideline adaptation process. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:693–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45(suppl 2):II43–II47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2009;104(suppl 1):S1–S35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolliver BA, Herrera JL, DiPalma JA. Evaluation of patients who meet clinical criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:176–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olden KW. Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1701–1714. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammer J, Eslick GD, Howell SC, Altiparmak E, Talley NJ. Diagnostic yield of alarm features in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2004;53:666–672. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.021857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanner SJ, Depew WT, Paterson WG, et al. Predictive value of the Rome criteria for diagnosing the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2912–2917. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim ES, Cheon JH, Park JJ, et al. Colonoscopy as an adjunctive method for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome: focus on pain perception. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1232–1238. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome is associated with diverticular disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:652–661. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Feld AD, et al. Utility of red flag symptom exclusions in the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:137–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Black TP, Manolakis CS, Di Palma JA. “Red flag” evaluation yield in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Limsui D, Pardi DS, Camilleri M, et al. Symptomatic overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and microscopic colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:175–181. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67–75. e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HJ. What is the FODMAP? Korean J Medicine. 2015;89:179–185. doi: 10.3904/kjm.2015.89.2.179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Food choice as a key management strategy for functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:657–666. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iacovou M, Tan V, Muir JG, Gibson PR. The Low FODMAP diet and its application in East and Southeast Asia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21:459–470. doi: 10.5056/jnm15111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Anderson JL, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr. 2012;142:1510–1518. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.159285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MC. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: the FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:252–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, Bajor A, Sadik R. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:915–922. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daley AJ, Grimmett C, Roberts L, et al. The effects of exercise upon symptoms and quality of life in patients diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29:778–782. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Muris JW, Whorwell PJ, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW. Soluble or insoluble fibre in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3154. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1367–1374. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snook J, Shepherd HA. Bran supplementation in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:511–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belsey JD, Geraint M, Dixon TA. Systematic review and meta analysis: polyethylene glycol in adults with non-organic constipation. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:944–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chapman RW, Stanghellini V, Geraint M, Halphen M. Randomized clinical trial: macrogol/PEG 3350 plus electrolytes for treatment of patients with constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1508–1515. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lacy BE, Weiser K, De Lee R. The treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2009;2:221–238. doi: 10.1177/1756283X09104794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nigam P, Kapoor KK, Rastog CK, Kumar A, Gupta AK. Different therapeutic regimens in irritable bowel syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 1984;32:1041–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centonze V, Imbimbo BP, Campanozzi F, Attolini E, Daniotti S, Albano O. Oral cimetropium bromide, a new antimuscarinic drug, for long-term treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:1262–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Muris JW. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Annaházi A, Róka R, Rosztóczy A, Wittmann T. Role of antispasmodics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6031–6043. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wittmann T, Paradowski L, Ducrotte P, Ducrotté L, Andro Delestrain MC. Clinical trial: the efficacy of alverine citrate/simeticone combination on abdominal pain/discomfort in irritable bowel syndrome--a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:615–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Everitt H, Moss-Morris R, Sibelli A, et al. Management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: the results of an exploratory randomised controlled trial of mebeverine, methylcellulose, placebo and a self-management website. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Darvish-Damavandi M, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of efficacy and tolerability of mebeverine in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:547–553. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i5.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clave P, Acalovschi M, Triantafillidis JK, et al. Randomised clinical trial: otilonium bromide improves frequency of abdominal pain, severity of distention and time to relapse in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:432–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng L, Lai Y, Lu W, et al. Pinaverium reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1285–1292. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Awad RA, Cordova VH, Dibildox M, Santiago R, Camacho S. Reduction of post-prandial motility by pinaverium bromide a calcium channel blocker acting selectively on the gastrointestinal tract in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 1997;27:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kruis W, Weinzierl M, Schüssler P, Holl J. Comparison of the therapeutic effect of wheat bran, mebeverine and placebo in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 1986;34:196–201. doi: 10.1159/000199329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cann PA, Read NW, Holdsworth CD, Barends D. Role of loperamide and placebo in management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:239–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01296258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lavö B, Stenstam M, Nielsen AL. Loperamide in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome--a double-blind placebo controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1987;130:77–80. doi: 10.3109/00365528709091003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hovdenak N. Loperamide treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1987;130:81–84. doi: 10.3109/00365528709091004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Efskind PS, Bernklev T, Vatn MH. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial with loperamide in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:463–468. doi: 10.3109/00365529609006766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trinkley KE, Nahata MC. Medication management of irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2014;89:253–267. doi: 10.1159/000362405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldberg PA, Kamm MA, Setti-Carraro P, van der Sijp JR, Roth C. Modification of visceral sensitivity and pain in irritable bowel syndrome by 5-HT3 antagonism (ondansetron) Digestion. 1996;57:478–483. doi: 10.1159/000201377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Houghton LA, Foster JM, Whorwell PJ. Alosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, delays colonic transit in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:775–782. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Delvaux M, Louvel D, Mamet JP, Campos-Oriola R, Frexinos J. Effect of alosetron on responses to colonic distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:849–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng Y, Yu T, Tang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptor antagonists in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matsueda K, Harasawa S, Hongo M, Hiwatashi N, Sasaki D. A phase II trial of the novel serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist ramosetron in Japanese male and female patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2008;77:225–235. doi: 10.1159/000150632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matsueda K, Harasawa S, Hongo M, Hiwatashi N, Sasaki D. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the effectiveness of the novel serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist ramosetron in both male and female Japanese patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1202–1211. doi: 10.1080/00365520802240255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee KJ, Kim NY, Kwon JK, et al. Efficacy of ramosetron in the treatment of male patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial, compared with mebeverine. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:1098–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fukudo S, Ida M, Akiho H, Nakashima Y, Matsueda K. Effect of ramosetron on stool consistency in male patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:953–959. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fukudo S, Matsueda K, Haruma K, et al. Optimal dose of ramosetron in female patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase II study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13023. Published Online First: 16 Feb 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fukudo S, Kinoshita Y, Okumura T, et al. Ramosetron reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea and improves quality of life in women. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:358–366. e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fukudo S, Kinoshita Y, Okumura T, et al. Effect of ramosetron in female patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: a phase III long-term study. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:874–882. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim DY, Camilleri M. Serotonin: a mediator of the brain-gut connection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2698–2709. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grider JR, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Jin JG. 5-Hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor agonists initiate the peristaltic reflex in human, rat, and guinea pig intestine. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:370–380. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Prather CM, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, McKinzie S, Thomforde G. Tegaserod accelerates orocecal transit in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:463–468. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bove A, Bellini M, Battaglia E, et al. Consensus statement AIGO/SICCR diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation and obstructed defecation (part II: treatment) World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4994–5013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i36.4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Thomforde G, McKinzie S, Zinsmeister AR. Prucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation without a rectal evacuation disorder. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:354–360. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344–2354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, Ausma J. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation--a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:315–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tack J, van Outryve M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L. Prucalopride (Resolor) in the treatment of severe chronic constipation in patients dissatisfied with laxatives. Gut. 2009;58:357–365. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.162404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ke M, Zou D, Yuan Y, et al. Prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation in patients from the Asia-Pacific region: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:999–e541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ke M, Tack J, Quigley EM, et al. Effect of prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation in Asian and non-Asian women: a pooled analysis of 4 randomized, placebo-controlled studies. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:458–468. doi: 10.5056/jnm14029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR., 3rd American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:218–238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spiller R, Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1979–1988. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]