Abstract

Study Objectives:

Narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia are chronic neurological sleep disorders characterized by hypersomnolence or excessive daytime sleepiness. This review aims to systematically examine the scientific literature on the associations between narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia and their effect on intellectual functioning, academic achievement, behavior, and emotion.

Methods:

Published studies that examined those associations in children and adolescents were included. Studies in which children or adolescents received a clinical diagnosis, and in which the associated function was measured with at least one objective instrument were included. Twenty studies published between 1968 and 2017 were eligible for inclusion in this review.

Results:

There does not appear to be a clear association between intellectual functioning and narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia; however, limited research is an obstacle to obtaining generalizability. The variability in results from studies investigating associations between academic achievement and these two hypersomnolence disorders suggests that further research using standardized and validated assessment instruments is required to determine if there is an association. Behavior and emotion appear to be significantly affected by narcolepsy. Only two studies included populations of children and adolescents with idiopathic hypersomnia.

Conclusions:

Further research using larger populations of children and adolescents with narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia while utilizing standardized and validated instruments is required, because the effect of these conditions of hypersomnolence varies and is significant for each individual.

Citation:

Ludwig B, Smith S, Heussler H. Associations between neuropsychological, neurobehavioral and emotional functioning and either narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia in children and adolescents. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(4):661–674.

Keywords: academic achievement, behavior, emotion, excessive daytime sleepiness, hypersomnolence, idiopathic hypersomnolence, intellectual functioning, narcolepsy

INTRODUCTION

Daytime sleepiness has a profound effect on everyday function in children and adolescents. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), or hypersomnolence, is frequently seen in association with sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Hypersomnolence in the pediatric population with OSA and its association with learning difficulties, behavior, and psychological well-being have been studied extensively.1–4 However, other causes of hypersomnolence have not been investigated as thoroughly. Hypersomnolence is the primary symptom for the group of sleep disorders known as central disorders of hypersomnolence, of which narcolepsy type 1, narcolepsy type 2, and idiopathic hypersomnia are possibly the most well known.5 These conditions frequently present in childhood and adolescence, but often take some time to be diagnosed.6–8 A recent review by Blackwell et al.9 sought to identify to what extent research had focused on the effects of narcolepsy in children, in particular in their cognitive functioning and psychosocial well-being. The reviewers were responding to concerns regarding an increase in the incidence of narcolepsy diagnoses, and the necessity for monitoring these children and adolescents to enable management of the effects of this disorder. They were only able to identify eight studies that met their criteria for inclusion. The authors noted that restrictions such as small sample sizes and lack of control groups limited understanding of the consequences of narcolepsy. This analysis seeks to build on their review: (1) by widening the criteria to include both narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnolence as central disorders of hypersomnolence, (2) through an examination of a broader range of outcomes including intellectual functioning, academic functioning, executive functioning, behavior, and mood, and (3) by including papers from 1968 through to 2017.

METHODS

Literature Search

Published studies that examined the associations between neuropsychological, neurobehavioral, and emotional functioning and either narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia in children and adolescents were included. Studies in which children or adolescents received a clinical diagnosis, and in which the associated function was measured with at least one objective instrument were included. The search parameters were confined to papers published in English. MEDLINE and Embase databases were accessed to search articles from 1960 through June 2017 using combinations of the following subject terms: narcolepsy OR idiopathic hypersomnia, AND children OR pediatric OR paediatric, AND cognition OR memory OR learning OR cognitive OR neuropsychological OR neurobehavioural OR neurobehavioral OR behaviour OR behavior. This yielded a total of 118 articles.

Inclusion Criteria

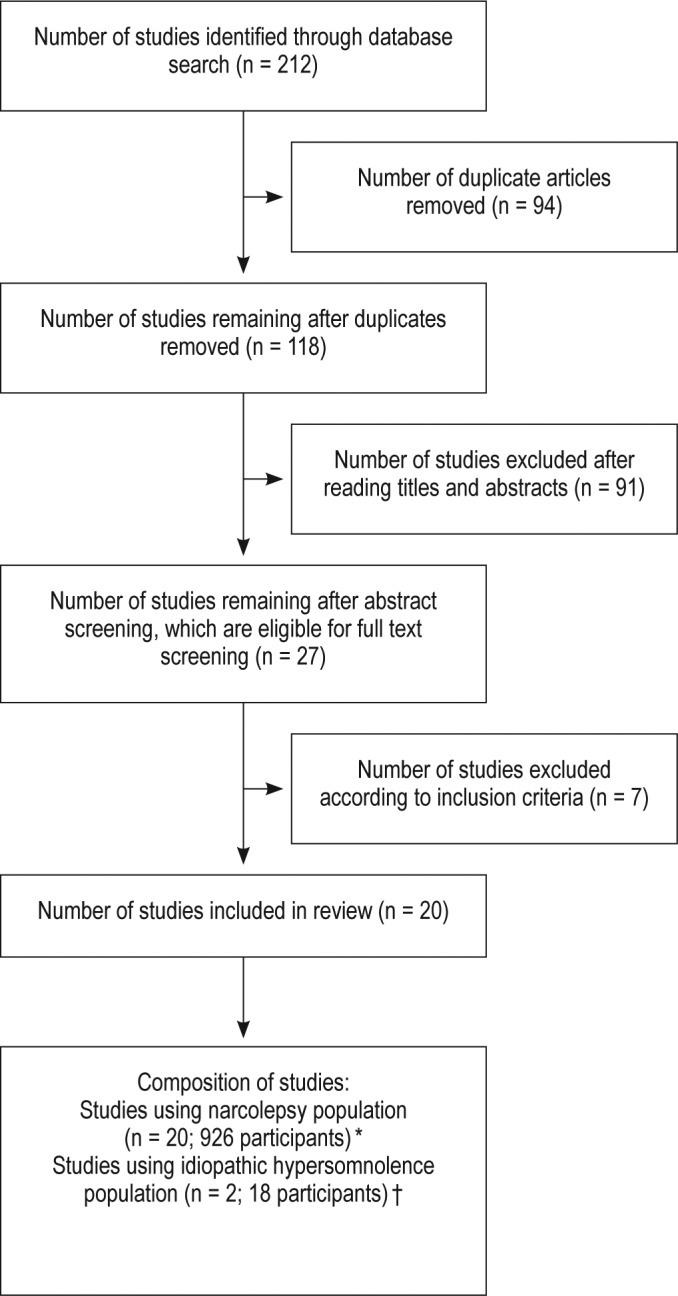

Titles and abstracts were scanned for the inclusion criteria, with the full-text version (if available) being collected when further information was required to assess suitability, or if it was determined the article fulfilled criteria. Criteria included articles written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals. Quantitative studies gave sound data on the effect of hypersomnolence whereas the selected case studies gave qualitative information, which is significant in gaining real-world perspectives of the implications. A total of 20 articles were included for this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Research populations.

Flow diagram for identification of studies and research populations. * = not all studies identified whether the children had narcolepsy with or without cataplexy. † = populations of children with idiopathic hypersomnolence were included in studies with populations of children with narcolepsy.

Quality Assessment

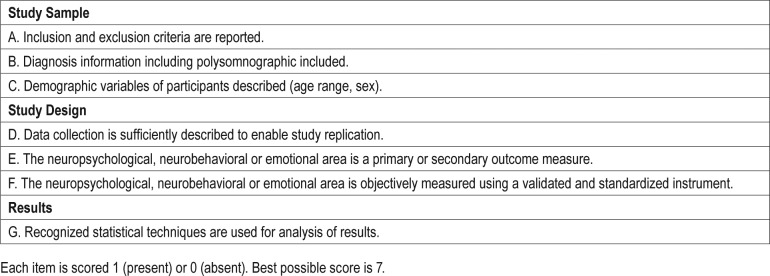

To assess the quality of studies, a set of criteria was developed based on criteria utilized in recent similar reviews. Unique criteria were developed due to the specificity of this field of research and the understanding that research in this area is generally unable to utilize randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Each article was rated according to these criteria (Table 1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). Studies were excluded if they did not provide details on demographic and diagnostic details of participants or if there was a high risk of bias according to the Cochrane risk of bias tool.10

Table 1.

Scale for methodological quality assessment.

RESULTS

Study Characteristics

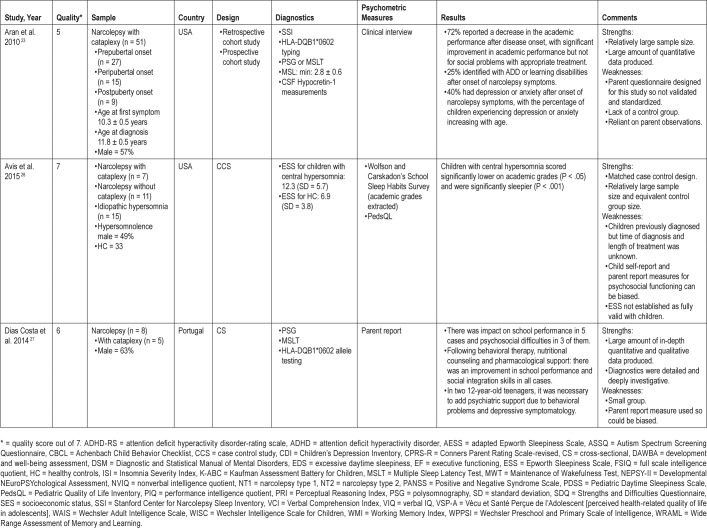

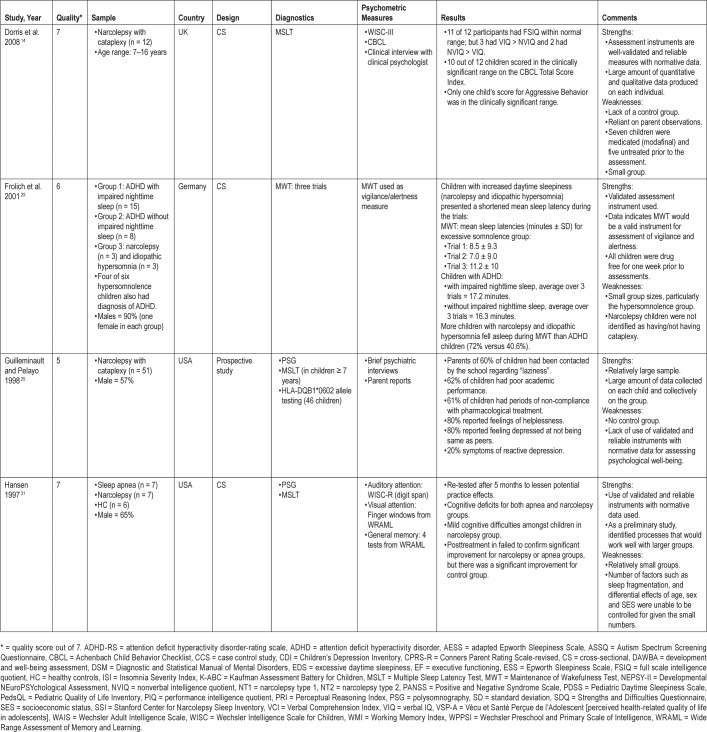

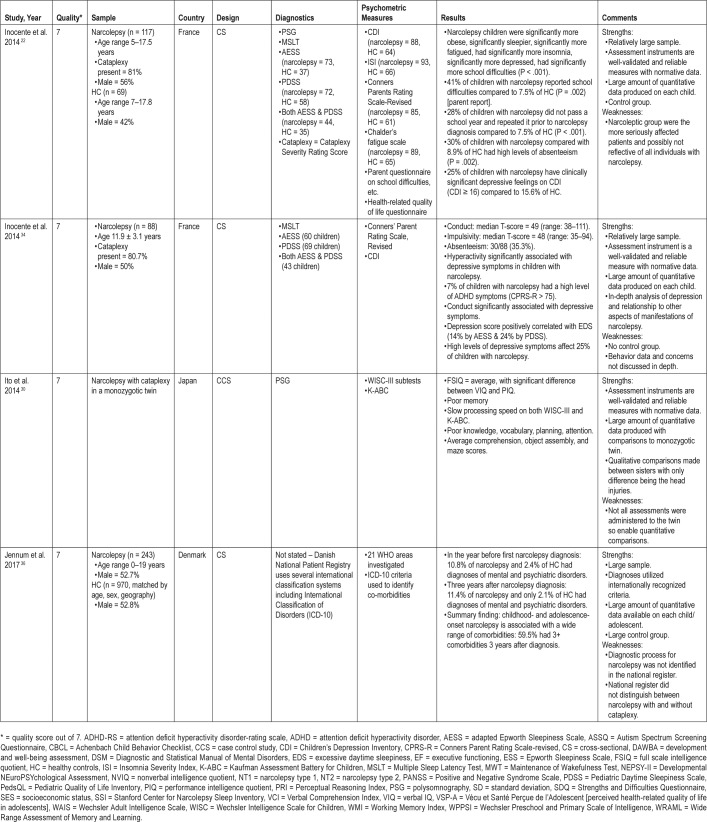

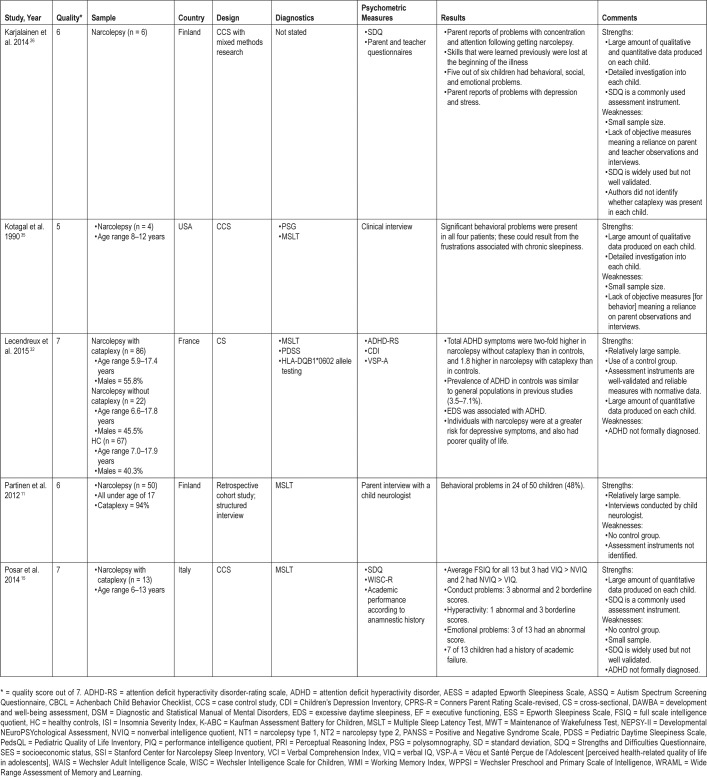

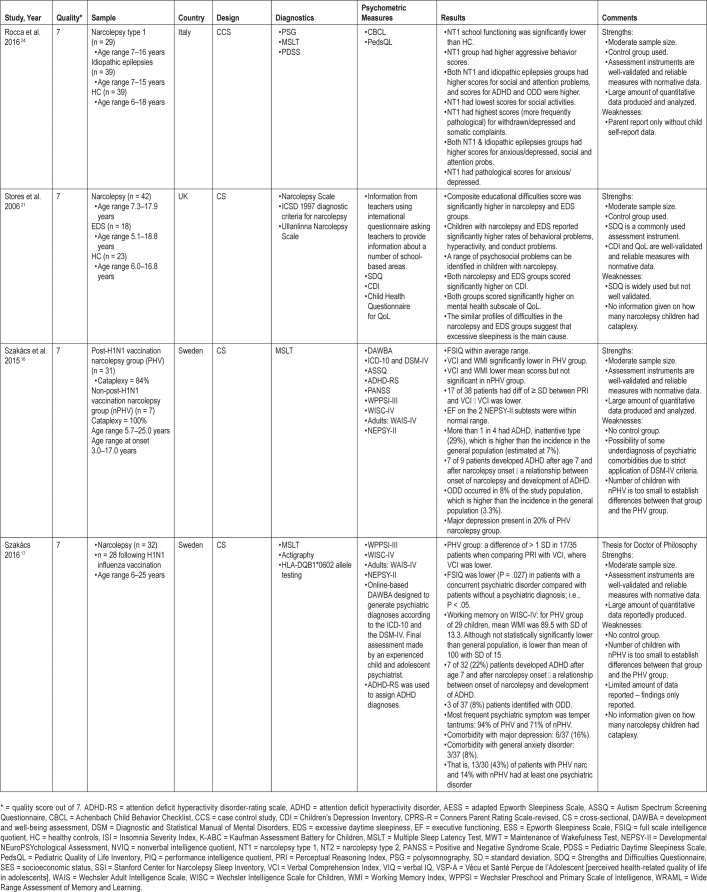

Study characteristics for each of the 20 articles included in this review are summarized in Table 2. This gives information on sample size and origin (such as the inclusion of narcolepsy with and without cataplexy and the use of matched control groups), country, design (six studies were case studies providing a wealth of qualitative information on the more personal effect of narcolepsy on individuals), diagnostics, and psychometric measures used. Results for each are reported and the strengths and weaknesses for each study identified.

Table 2.

Summary of papers included within the review.

Nine studies used relatively large groups, ranging in size from 29 (narcolepsy type 1) through to 243 (narcolepsy with and without cataplexy). Access to these larger groups was due to the increase in the number of cases of children with narcolepsy following the 2009 Pandemrix vaccination used in several European countries. This vaccine triggered what is thought to be an autoimmune reaction, causing narcolepsy to develop in people who were genetically at risk.11–13

Methodological Quality of Studies

A full overview of the quality ratings of the included studies can be found in Table S1, with the criteria for this table outlined in Table 1. Table S1 also contains the bias and Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) levels that contain three levels for study quality (level 1 being good-quality patient-oriented evidence) and three levels for strength of recommendation (level A representing consistent evidence). The screening for bias used the Cochrane bias method, and all studies were identified as having a low risk of bias. The SORT criteria were used to identify the quality, quantity, and consistency of evidence. Level 1 studies require good-quality, patient-oriented evidence with a high-quality individual RCT (6 studies). As such, the quality of 14 studies was identified as rating at a level 2 due to (1) not being RCTs and (2) by using smaller groups of children. Studies with a level 1 quality rating generally had a control group, but also used standardized assessments, meaning scores could be compared to a large population mean. The strength of recommendation was generally identified as level B, which is based on limited-quality, patient-oriented evidence. This was due to most studies being single investigations of a smaller population. One study did not report its design in sufficient detail to enable replication of data collection. That is, the interview questionnaires were not identified in the report. Although a number of studies relied on interviews or qualitative collection of information, they were included in this review. However, these studies gained low quality and strength of recommendation ratings. The inclusion of qualitative information is essential with disorders such as narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia due to the significant effect on the individual's lives and the lives of those around him or her. All studies used recognized statistical techniques for data analysis.

Intellectual Functioning and Hypersomnolence

The four studies (20%) that looked at the intellectual implications of a hypersomnolence disorder all used one of the Wechsler assessments to determine intellectual functioning, with verbal IQ (VIQ) and nonverbal IQ (NVIQ) also reported. Two of the four studies14,15 were case studies employing standardized assessments that yielded quantitative data that resulted in individual rather than group findings being reported. Eleven of 12 children in the study by Dorris et al.14 and the 13 children in the study by Posar et al.15 had a full-scale IQ (FSIQ) in the average range, although 5 children in each study had a discrepancy of more than one standard deviation between their VIQ and NVIQ, thus displaying disparate intellectual abilities. Both studies used standardized norms for the particular assessment instrument administered.

The two studies16,17 that were conducted with larger groups of children and adolescents with narcolepsy also found that most subjects had a FSIQ in the average range, with a number having a FSIQ in the gifted range. These studies investigated groups of 38 and 37 participants respectively, allowing some generalizability of results. Again, many children and adolescents had a significant discrepancy between two or more of the four indices that compose the FSIQ in the Wechsler assessments. However, statistically significant discrepancies between factor indices included in the FSIQ are not unusual in the general population as explored and discussed by Kahana et al.18 Their investigation using the Differential Ability Scales with a nationally representative sample of 1,185 children found that 31.5% had a significant discrepancy between the verbal and nonverbal reasoning indices. Overall, 80% of their sample had a significant discrepancy between factor or subtest scores. The Szakaács17 study also found a significant difference between the FSIQ of those with a concurrent, diagnosed psychiatric disorder and those without, whereas those with a concurrent psychiatric disorder had a lower FSIQ. The concurrent psychiatric disorders included major depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and general anxiety disorder.

In these four studies with 98 participants being assessed, almost all children and adolescents were identified as having a FSIQ within the average range, with most participants yielding significantly uneven cognitive profiles, thus being reflective of the general population. With so few studies, and relatively few participants, identification of any association between intellectual functioning and narcolepsy would be inconsistent and unreliable. In addition, there is a probability of underdiagnosis in less educated groups. A number of studies have identified the inequities associated with access to specialized medical care, with individuals with lower education seeing specialists less frequently than those with higher education levels.19,20 No studies have been conducted with participants who have a diagnosis of idiopathic hypersomnia.

Academic Achievement and Hypersomnolence

There do appear to be some cognitive effects of EDS not reflected in FSIQ. Specifically, Stores et al.21 identified an effect of the EDS associated with narcolepsy and EDS of uncertain origin on educational achievement (narcolepsy = 42, EDS = 18, healthy controls = 23). They developed a composite educational difficulties score using four items rated 0 or 1 and found that in comparison with their control group, the composite educational difficulties score was significantly higher in the narcolepsy and EDS groups. Additionally, in a larger study exploring the associations of narcolepsy with various intellectual, academic, and quality-of-life aspects, Inocente et al.22 found that children with narcolepsy (n = 117) had significantly more school difficulties than matched healthy controls (n = 69). This association was also identified in other research with relatively large groups of children with narcolepsy. Aran et al.23 (n = 51) determined that 72% of parents reported a decrease in academic performance following development of narcolepsy. However, this was somewhat alleviated with appropriate treatment. Rocca et al.24 cited that parent reports identified school functioning was significantly lower in children with narcolepsy (n = 42) than that of the healthy controls (n = 23). Guilleminault and Pelayo25 (n = 51) reported that more than half their participants indicated difficulties with academic achievement, with many children repeating a year of schooling.

Although not as compelling as investigations with large groups, the qualitative evidence gleaned from case studies provides insights often unavailable from data alone. Three case studies explored the association between narcolepsy and academic functioning. Karjalainen et al.26 used mixed-methods research including parent and teacher questionnaires and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) with the six children in whom narcolepsy was diagnosed. This real-life context yielded parent reports of problems with concentration and attention following the development of narcolepsy, and observations that skills that had been previously learned were lost following the onset of the disorder. Whole class work was reported as being particularly challenging, so that smaller group or individual teaching was required. Narcolepsy developed in all six children following the 2009 Pandemrix vaccination. Seven of the 13 children in the study by Posar et al.15 were identified as having a history of academic failure. This is despite having a FSIQ within the average range for their age. In their group of eight children, Dias Costa et al.27 found that parents of five of those children reported an effect on school performance but that there was an improvement following behavioral therapy, nutritional counseling, and pharmacological support.

The Avis et al.28 study included children with a variety of central disorders of hypersomnolence: narcolepsy with cataplexy (n = 7), narcolepsy without cataplexy (n = 11), idio -pathic hypersomnia (n = 15), and 33 healthy controls. It found that all children with a central disorder of hypersomnolence scored significantly lower on academic grades with a Cohen effect size value suggesting a moderate practical significance. These children were also significantly sleepier. The academic grade scores were extracted from the Wolfson and Carskadon's School Sleep Habits Survey and the “sleepiness score” was determined using a modified Epworth Sleepiness Scale. This was the only study to clearly explore the association between academic functioning and hypersomnolence, while including a population with idiopathic hypersomnia.

Nine of the 20 studies (45%) in this review purported to explore an association between academic functioning and a central disorder of hypersomnolence, principally narcolepsy. Eight of the nine relied primarily on observational data. All nine reported significantly lower academic functioning, although in some studies it was acknowledged this had been somewhat alleviated through appropriate treatment. Only one study included a population of children with idiopathic hyper-somnia (n = 15); therefore, no generalizations can be drawn from that small sample. As all nine studies relied on parent reports and questionnaires, information from teachers, or standardized checklists, there is no reliable information on the association between central disorders of hypersomnolence and academic achievement. The use of valid and reliable, normed and standardized assessment instruments such as the Wide Range Achievement Test would enable any effect of hypersomnolence to be more clearly identified. Scores within this population could be more readily compared to norms for a regular population.

Executive Functioning and Hypersomnolence

Seven studies (35%) explored the relationship between a central disorder of hypersomnolence and executive functioning (EF), with only one of those utilizing a population of children with idiopathic hypersomnia (n = 3).29 Of the other six studies exploring the relationship between EF and hypersomnolence, two were case studies and one focused on a small group (n = 7). One case study investigated a twin who had developed narcolepsy.30 The remaining three studies accessed groups ranging in size from 29 to 38—thus small populations overall. In all seven studies, the EF and hypersomnolence association was irregularly explored with inconsistent methodologies, multiple definitions of EF, and numerous choices of assessment instruments. These included subtests from the Wechsler scales,16,17,30,31 Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning,31 Developmental NEuroPSYchological Assessment,16,17 and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).24 One study utilized parent and teacher questionnaires with the SDQ.26 The Frolich et al.29 study explored vigilance as one of the executive functions associated with attention in a population with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and in children with disorders of excessive somnolence. Research utilizing populations of participants with ADHD and participants with a central disorder of hypersomnolence is relatively common, as an association has been identified.32,33 Frolich et al.29 found all children with a disorder of excessive somnolence had significantly shorter sleep latency during the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test. This was used to identify vigilance. Although their data are consistent with some potential effects on vigilance, the small participant numbers do not allow for generalizability. Additional assessments of EF, particularly those associated with attention and vigilance, would enable further support of their findings.

No firm conclusions can be drawn from these data because (1) the wide variety of assessment instruments, (2) the differing aspects of EF each instrument assesses, and (3) the use of noncomparable parent and teacher interviews. Each individual study did identify problems such as a significantly lower mean score for working memory, and poor planning and attention.

Behavior and Hypersomnolence

Behavior problems, including increases in anger, aggression, impulsivity, and inattention, were reported in many children following the onset of narcolepsy. Of the 20 studies included in this review, 11 (55%) included behavior as one of the foci investigated by either standardized behavior assessments or interviews with parents, caregivers, the individuals themselves, and their educators. A number of studies reported that ADHD characteristics, including poor attention and focus, which led to a diagnosis of ADHD inattentive type, was identified after an investigation into the postnarcolepsy behaviors. Specifically, the Szakaács et al.16 study found more than 1 in 4 of the 31 children (29%) in the post-H1N1 vaccination group gained a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD inattentive type, which is significantly higher than the estimated incidence of 7% in the general population. Further, they found that one of the seven in whom narcolepsy developed without the vaccination trigger had gained comorbid diagnoses of ADHD inattentive type and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). A later study by Szakaács17 found that 7 of the 32 children (22%) gained a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD. Of the 32 children in his study, narcolepsy developed in 28 following the H1N1 vaccination. These high incidences of ADHD in the narcolepsy population was also identified by Aran et al.23 who noted that 22% of 40 children exhibited a comorbidity (some prior to the diagnosis of narcolepsy). Inocente et al.34 also found that heightened hyperactivity as identified in the Conners Parent Rating Scale, Revised (CPRS-R) was identified in 22% of the 81 children screened. Lecendraux et al.,32 who used the ADHD Rating Scale, which was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, found that clinically significant levels of ADHD symptoms were identified in 4.8% of controls (n = 67). However, they also reported a significantly higher incidence in patients with narcolepsy without cataplexy (35.3% of 22) than in patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy (19.7% of 86). It could be questioned, therefore, whether findings in those studies exploring the relationship between narcolepsy and ADHD constitute true comorbidity. A number of the diagnostic items for ADHD overlap those for narcolepsy including sustaining attention difficulties and EDS.32

Other larger group studies had similar findings, with behavioral problems identified in significant percentages of children with narcolepsy. Partinen et al.11 used parent interviews with a child neurologist to identify behavioral problems in 24 of the 50 children (48%) in their study. Rocca et al.24 used a case-control study to explore the profiles of 29 children with narcolepsy type 1, comparing those findings with children with idiopathic epilepsies (n = 39) and healthy controls (n = 39). The children with narcolepsy were found to have increased attention deficit problems and aggressive behavior over children in either of the other two groups. ADHD behavior, ODD behavior, and conduct disorder were also found to be heightened in comparison with the control group. The study by Stores et al.21 developed the association of these behaviors with EDS symptomatic of narcolepsy by including a group of children who exhibited EDS (n = 18). With 42 in the narcolepsy group and 23 healthy controls, participant numbers gave Stores et al. some strong data although they used the SDQ as their behavior assessment instrument. The mean scores for the narcolepsy and EDS groups were significantly higher for hyperactivity, conduct problems, and adverse effect on the family. The total SDQ score for these two groups was also significantly higher than the score for the control group. The Cohen effect-size values indicate a moderate to high practical significance, suggesting EDS is the cause for behavior issues in children with narcolepsy.

These latter group findings suggest that not only is inattention and poor focus found to be significantly more frequent in children with narcolepsy, but that other behavior problems may also present and that these identifiers could include hyperactivity and impulsivity, aggression, conduct problems, and oppositional behavior.

Other researchers have also taken a deep investigative approach using case studies which typically use smaller groups of children, enabling associations between narcolepsy and many other life aspects to be fully detailed for each child. Karjalainen et al.26 found five of the six children in their study had behavioral and social problems; and Kotagal et al.35 identified significant behavior problems in all four children they investigated. Two case studies used slightly larger groups. Dorris et al.14 (n = 12) found 3 of the 12 children (25%) had a clinically significant score on the externalizing index of the CBCL, with only one having an aggressive behavior score in the clinical range. Posar et al.15 (n = 13) used the SDQ to identify that 3 of the 13 children (23%) had a score in the clinical range for conduct problems, although 2 other children had borderline scores. There was only one child (8%) who gained a score in the clinical range for hyperactivity, whereas three other children had borderline scores. Although these incidences are similar to that identified in the larger groups investigated, the smaller numbers disallow any generalization.

In all 11 studies that investigated the association between behavior and narcolepsy, the numbers of children identified as displaying inattention, poor focus, impulsivity, aggressive behavior, conduct problems, and/or oppositional behavior was generally significantly higher than the incidence in the general population. A number of studies suggested the EDS of hypersomnolence disorders as the cause for these poor behaviors. All studies used parent reports to identify these behaviors, whether it was through standardized screeners such as the Conners, CBCL, or SDQ, or through in-depth parent interviews. Table 2 includes a summary of findings of associations explored between behavior and hypersomnolence.

Emotion and Hypersomnolence

Anxiety, depression, and/or other emotionally-based problems also appear to be strongly associated with hypersomnolence with 14 of 20 studies (70%) in this review exploring the association. In particular, depression has been identified as having a strong statistical association with hypersomnolence across a number of studies, many of which utilized the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), an internationally recognized, reliable, and validated screener for depression in children. To incorporate observations from parents about their child's behavior and feelings in a range of situations, a variety of other instruments and/or parent questionnaires were also utilized. In many cases this revealed their child was experiencing a greater level of difficulty than other children in that age cohort.

An earlier study in this review by Guilleminault et al.,25 noted that concerns regarding the association between depression and narcolepsy had already been identified up to 20 years ago. Their study utilized 51 prepubertal children, 40 of whom were age 7 years and older. The psychiatric interviews with those subjects found 32 (80%) were “depressed by their inability to be the same as their peers despite not having any physical signs” (p. 140), and eight (20%) were thought to have symptoms of reactive depression. These children displayed poor appetite, disinclination toward social activities or previously enjoyed activities, decline in self-esteem, and crying spells. A concern raised in this study was the lack of support for these children in the school setting where they were often labeled as “lazy,” and were disciplined for falling asleep, being unmotivated, having poor attention or concentration, and exhibiting memory problems. Six families had been contacted on suspicion of their children using illicit drugs. During follow-up, all families reported occasions when their child presented with depressive symptoms subsequently thought to be associated with the narcolepsy. Given this foundation for exploration of an association between depression and narcolepsy, an identification that 12 other studies had explored this area since that time is heartening.

Two studies conducted by Inocente et al.22,34 explored the association between depression and narcolepsy using relatively large groups of children (n = 88 and n = 117). Depres -sion was positively correlated with sleepiness, and when comparison with a control group was established the children with narcolepsy were significantly more depressed than their healthy colleagues. Both studies utilized the CDI as well as other assessment instruments. Lecendreux et al.32 focused on the incidence of ADHD symptoms in children with narcolepsy, including groups with (n = 86) and without cataplexy (n = 22), and in comparison with a control group (n = 67). In addition to identifying clinically significant levels of ADHD symptoms in the two narcolepsy groups (30% and 15% respectively compared to an incidence of 5% to 6% in the control group) Lecendreux et al. also posited that those children with the clinically significant levels of ADHD symptoms also had higher levels of depressive symptoms. It appears, therefore, that a number of comorbid conditions develop with the onset of narcolepsy.

Other sizeable studies had similar findings: 20% of the 40 screened (n = 51) in the study by Aran et al.23 were identified as having clinically significant depression or anxiety after the onset of narcolepsy symptoms. Stores et al.21 explored emotional and psychosocial problems among three groups: narcolepsy (n = 42), EDS (n = 18), and healthy controls (n = 23), using the CDI. Both the narcolepsy and EDS group means were significantly higher than the control group mean. The narcolepsy and EDS group means were statistically similar, suggesting that the association with depressive symptoms may be EDS. The Rocca et al.24 study used the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory to screen for anxiety and depression. They found both the narcolepsy type 1 group (n = 29) and the idiopathic epilepsies group (n = 39) had significantly higher mean scores than the healthy control group (n = 39) for anxiety/depression, whereas the narcolepsy group's mean scores were in the pathological range. Both the Szakaács et al.16 (post-H1N1 vaccination narcolepsy group; n = 31) and the Szakaács17 (n = 37) studies identified a high incidence of children with major depression: 20% and 16% respectively. This study also identified 3 of the 37 children as having generalized anxiety disorder. Many of these larger studies also found comorbidities with a number of other psychiatric disorders. Jennum et al.36 investigated all diagnosed cases of narcolepsy from 1998 through to 2012 using the Danish National Patient Registry (n = 243). These cases were compared with 970 matched controls, 4 for each narcolepsy patient and randomly chosen from the Danish Civil Registration System Statistics. In Denmark, each person is placed on a national patient database and, because all Danes are registered with their Social Security codes, the two databases can be linked. Jennum et al. investigated 21 World Health Organization areas, using several classification systems including the International Classification of Disorders, Tenth Edition. They found that in the year prior to their official diagnosis of narcolepsy, 10.8% of the patients also had diagnoses of mental and psychiatric disorders compared to only 2.4% of the controls having these diagnoses. In the third year following their diagnosis of narcolepsy, 11.4% of patients also had diagnoses of mental and psychiatric disorders compared to only 2.1% of the controls having these diagnoses.15,16,17,18,36 They concluded that narcolepsy in children and adolescents is associated with a range of comorbidities, and in this case, with a significant number of mental and psychiatric disorders.

Four studies conducted a deeper investigation into smaller groups of children using a case-study approach: Dias Costa et al.27 (n = 8), Dorris et al.14 (n = 12), Karjalainen et al.26 (n = 6), and Posar et al.15 (n = 13). All had similar findings regarding the risk for emotional problems, internalizing problems, and depressive symptomatology. The psychological morbidity associated with narcolepsy appears to be significant, and affects most aspects of these children's lives. Indeed, interviews conducted by Karjalainen et al. with the children, their parents, teachers, and community support workers reported that the children felt their “lives had lost joy and childhood unconcern” (p. 876).

An association between hypersomnolence and emotional problems was found in all 14 studies. Although no studies in this section included a population of children with idiopathic hypersomnia, it could reasonably be assumed that these children and adolescents are also at risk of the development of emotional problems due to the EDS associated with that condition. Table 2 includes a summary of findings of associations explored between emotion and hypersomnolence.

DISCUSSION

A review of the association between central disorders of hypersomnolence in children and adolescents and the effect of hypersomnolence on intellectual functioning, academic functioning, executive functioning, behavior, and emotion was conducted. Twenty studies, published between 1960 and June 2017 were included in this review.

Given there were only four studies that explored the relationship between hypersomnolence and intellectual functioning, no clear association between the two aspects was identified. Many participants did have a significant difference between their nonverbal IQ and verbal IQ; however, this difference was also inconsistent, with some individuals having a significantly stronger nonverbal IQ and others having a significantly stronger verbal IQ. Significant differences between factor indices are not unusual in the regular population. Therefore, it could not be clearly established that hypersomnolence is associated with specific inconsistencies within a cognitive profile.18

School difficulties, however, were frequently identified as being significantly associated with the EDS of central disorders of hypersomnolence. These difficulties were often reported through use of qualitative methods such as interviews with parents and teachers. The interviews yielded descriptions of the effect such as: “deterioration in school performance,” or “decrease in academic performance,” or “school functioning is identified as significantly lower” following the onset of narcolepsy. Because only one study had included a population of children with idiopathic hypersomnolence (n = 15), no generalizations can be drawn for that population; however, this study did identify that all children with central hypersomnia had lower academic grades, and were significantly sleepier than healthy children.28 The proportion of children and adolescents with narcolepsy who had repeated a year in school was also significantly higher than that of the general population. Much of the decrease in academic achievement was identified as resulting from the strong effect of the EDS associated with narcolepsy. EDS appears to affect concentration and attention, thus inhibiting the individual from engaging fully with the classroom curriculum and being able to learn, rehearse, and consolidate concepts in the foundational academic areas of literacy and numeracy.

This academic effect through poor attention and concentration appears to be related to EF. As reported earlier, because of inconsistencies in the definition of EF, the variety of EF aspects assessed, and the various assessment instruments used, a robust association between narcolepsy and EF cannot be clearly articulated. Further exploration of the association between EF and central disorders of hypersomnolence using standardized assessment instruments and an internationally recognized model of executive functioning is required, as there could be a strong relationship between them.

EF encompasses a number of higher order thinking skills that can be organized into four discrete yet interrelated domains: cognitive flexibility, goal setting, attentional control, and information processing—each with a number of integrated cognitive processes.37 These skills are necessary for everyday living, academic development, and participation in the social arena. Any future research should also articulate the specific aspects of EF being investigated particularly as there are numerous higher-order thinking skills identified within this area. That is, the definition of EF needs to be formalized using reliable and valid assessment instruments clearly linked to the particular aspect of EF being assessed. Further, behaviors associated with EF should also be capable of undergoing objective observation using credible instruments. Finally, the sleep-wake behaviors associated with central disorders of hypersomnolence need to be objectively and reliably measured because at this point in time the possibility that central disorders of hypersomnolence affect EF is unsubstantiated.

This review also identified an association between behavior problems and narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia. Across studies, significant numbers of participants gained a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD (inattentive type) following the onset of narcolepsy. In addition to this diagnosis, heightened hyperactivity, ODD, and increased aggression were identified in significant numbers of participants. The influence on family life, the individual's social life, and their schooling present research challenges, but this review suggests the effects are significant. Behavior is reportedly so significantly affected by a central disorder of hyper-somnolence such as narcolepsy that it warrants further investigation, particularly into efficacious treatment strategies.

These individuals with narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia experience emotional difficulties. This review identified the strong association between depression and narcolepsy across many studies incorporating large numbers of participants. Participants were also frequently identified with other emotional disorders, particularly anxiety. The most in-depth study found a significant number of children and adolescents with narcolepsy also had comorbid diagnoses of mental and psychiatric disorders.36

The current review further highlights both the thrust of research into central disorders of hypersomnolence, and the significant association that EDS has with the academic, behavioral, and social aspects of these individual's lives. These contribute to a poorer quality of life and loss of self-esteem. The current state of research findings requires further in-depth investigations into the effects of EDS associated with these disorders, and especially identifies the need to explore populations with idiopathic hypersomnia.

Limitations

This review highlights a number of limitations of the current literature available on this topic. Of particular concern is the low number of studies utilizing larger groups of participants and the lack of studies including a control group. The apparent inconsistency in use of standardized assessment instruments is also a limitation, due to the lack of opportunity for comparisons between studies. This was particularly evident for the EF and academic functioning effect areas. In addition, the inclusion of an objective measure of sleepiness would have enabled clearer associations to be identified, as would identification of whether the participants were medicated, and to what extent.

There appears to be overlap between certain studies, with three publications possibly reporting on the same population of patients, despite a difference in n values.22,32,34 This also appears to have been the case in a separate two publication analysis.16,17 Duplication of participants would render the final participant count much lower, further reducing any generaliz-ability of findings.

A major limitation of this review was the inability to apply a meta-analysis as the data were too diverse to be integrated and analyzed. Although much of the research included quantitative data, there was an insufficient body of primary research studies to enable generation of a wide variety of research questions.

Practice Points

There appears to be an effect of EDS associated with central disorders of hypersomnolence, on academic achievement, behavior, and emotion.

EF appears to be affected; however, the data are inconsistent.

The effects of narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnolence are life changing, and close monitoring by parents, teachers, community workers, and physicians is required to ensure each individual is able to reach his or her potential.

Research Agenda

Further exploration of the effect of the EDS associated with central disorders of hypersomnolence in children and adolescents in a wider range of areas is required. This includes a focus on intellectual functioning, academic development, behavior, and emotional well-being, using standardized instruments, clearer definitions of the affected area, and larger cohorts.

Research into the EF of children needs to more clearly define the model of EF and its integral components prior to conducting the research. Standardized, normed, and validated instruments need to be used, with the specific area of EF clearly identified.

Inclusion of measurements of sleepiness at time of testing to more clearly identify any association between each affected area and EDS is required.

Identification of the effect of medication on EDS and assessment findings also needs to be included in future research.

CONCLUSIONS

This review of 20 studies, some with large groups using standardized assessment instruments and a variety of interviews or questionnaires, and others with small groups using a case-study approach has identified probable associations between central disorders of hypersomnolence and a number of areas including academic functioning, behavior, and emotion. The effect of EDS associated with central disorders of hypersomnolence is not well known and indicates the need for parents, teachers, community support workers, and physicians to closely monitor each individual's progress. Further research using objective and standardized assessment instruments, particularly with those individuals who have a diagnosis of idiopathic hypersomnia, may allow causality and treatment options to be identified.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Work for this study was performed at the University of Queensland. The authors confirm that all authors have substantially contributed to the conception and design, critical review for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published of this article. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADD

attention deficit disorder

- ADHD

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- CBCL

Child Behavior Checklist

- CPRS

Conners' Parent Rating Scales

- EDS

excessive daytime sleepiness

- EF

executive functioning

- FSIQ

full scale intelligence quotient

- ODD

oppositional defiant disorder

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PIQ

performance intelligence quotient

- PRI

Perceptual Reasoning Index

- PSG

polysomnography

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SDQ

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SORT

Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy

- VCI

Verbal Comprehension Index

- WMI

Working Memory Index

REFERENCES

- 1.Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bogels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(3):179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olaithe M, Nanthakumar S, Eastwood PR, Bucks RS. Cognitive and mood dysfunction in adult obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA): Implications for psychological research and practice. Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 2015;1(1):67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean B, Aguilar D, Shapiro CM, et al. Impaired health status, daily functioning, and work productivity in adults with excessive sleepiness. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(2):144–149. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c99505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilsmore BR, Grunstein RR, Fransen M, Woodward M, Norton R, Ameratunga S. Sleep habits, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness in a large and healthy community-based sample of New Zealanders. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(6):559–566. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrish E, King MA, Smith IE, Shneerson JM. Factors associated with a delay in the diagnosis of narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2004;5(1):37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luca G, Haba-Rubio J, Dauvilliers Y, et al. Clinical, polysomnographic and genome-wide association analyses of narcolepsy with cataplexy: a European Narcolepsy Network study. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(5):482–495. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorpy MJ, Krieger AC. Delayed diagnosis of narcolepsy: Characterization and impact. Sleep Med. 2014;15(5):502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackwell JE, Alammar HA, Weighall AR, Kellar I, Nash HM. A systematic review of cognitive function and psychosocial well-being in school-age children with narcolepsy. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011:343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partinen M, Saarenpaa-Heikkila O, Ilveskoski I, et al. Increased incidence and clinical picture of childhood narcolepsy following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccination campaign in Finland. PloS One. 2012;7(3):e33723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nohynek H, Jokinen J, Partinen M, et al. AS03 adjuvanted AH1N1 vaccine associated with an abrupt increase in the incidence of childhood narcolepsy in Finland. PloS One. 2012;7(3):e33536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trogstad L, Bakken IJ, Gunnes N, et al. Narcolepsy and hypersomnia in Norwegian children and young adults following the influenze A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic. Vaccine. 2017;35(15):1879–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorris L, Zuberi SM, Scott N, Moffat C, McArthur I. Psychosocial and intellectual functioning in childhood narcolepsy. Dev Neurorehabil. 2008;11(3):187–194. doi: 10.1080/17518420802011493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Posar A, Pizza F, Parmeggiani A, Plazzi G. Neuropsychological findings in childhood narcolepsy. J Child Neurol. 2014;29(10):1370–1376. doi: 10.1177/0883073813508315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szakács A, Hallböök T, Tideman P, Darin N, Wentz E. Psychiatric comorbidity and cognitive profile in children with narcolepsy with or without association to the H1N1 influenza vaccination. Sleep. 2015;38(4):615–621. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szakács A. Narcolepsy in children: Relationship to the H1N1 influenza vaccination, association with psychiatric and cognitive impairments and consequences in daily life. Gothenburg, Sweden: University of Gothenburg; 2016. [doctoral thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahana SY, Youngstrom EA, Glutting JJ. Factor and subtest discrepancies on the differential ability scales. Assessment. 2002;9(1):82–93. doi: 10.1177/1073191102009001010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim TJ, Vonneilich N, Ludecke D, von dem Knesebeck O. Income, financial barriers to health care and public health expenditure: A multilevel analysis of 28 countries. Soc Sci Med. 2017;176:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terraneo M. Inequities in health care utilization by people aged 50+: evidence from 12 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;126:154–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stores G, Montgomery P, Wiggs L. The psychosocial problems of children with narcolepsy and those with excessive daytime sleepiness of uncertain origin. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1116–e1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inocente CO, Gustin MP, Lavault S, et al. Quality of life in children with narcolepsy. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20(8):763–769. doi: 10.1111/cns.12291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aran A, Einen M, Lin L, Plazzi G, Nishino S, Mignot E. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of childhood narcolepsy-cataplexy: a retrospective study of 51 children. Sleep. 2010;33(11):1457–1464. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.11.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocca FL, Finotti E, Pizza F, et al. Psychosocial profile and quality of life in children with type 1 narcolepsy: a case-control study. Sleep. 2016;39(7):1389–1398. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilleminault C, Pelayo R. Narcolepsy in prepubertal children. Ann Neurol. 1998;43(1):135–142. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karjalainen S, Nyrhila AM, Maatta K, Uusiautti S. Going to school with narcolepsy - perceptions of families and teachers of children with narcolepsy. Early Child Dev Care. 2014;184(6):869–881. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dias Costa F, Barreto MI, Clemente V, Vasconcelos M, Estevao MH, Madureira N. Narcolepsy in pediatric age - experience of a tertiary pediatric hospital. Sleep Sci. 2014;7(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avis KT, Shen J, Weaver P, Schwebel DC. Psychosocial characteristics of children with central disorders of hypersomnolence versus matched healthy children. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(11):1281–1288. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frolich J, Wiater A, Lehmkuhl G, Niewerth H. The clinical value of the maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT) in the differentiation of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and disorders of excessive somnolence. Somnologie. 2001;5(4):141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito H, Kenji M, Tatsuo M, Aya G, Kagami S. Case of early childhood-onset narcolepsy with cataplexy: comparison with a monozygotic co-twin. Pediatr Int. 2014;56(5):790–793. doi: 10.1111/ped.12377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen DE. Cognitive effects of sleep apnea and narcolepsy in school age children. St. Louis, MO: University of Missouri-St. Louis; 1997. [doctoral thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lecendreux M, Lavault S, Lopez R, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in pediatric narcolepsy: a cross-sectional study. Sleep. 2015;38(8):1285–1295. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walters AS, Silvestri R, Zucconi M, Chandrashekariah R, Konofal E. Review of the possible relationship and hypothetical links between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and the simple sleep related movement disorders, parasomnias, hypersomnias, and circadian rhythm disorders. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(6):591–600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inocente CO, Gustin MP, Lavault S, et al. Depressive feelings in children with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2014;15(3):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.08.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotagal SV, Hartse KM, Walsh JK. Characteristics of narcolepsy in preteenaged children. Pediatrics. 1990;85(2):205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jennum P, Pickering L, Thorstensen EW, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J. Morbidity of childhood onset narcolepsy: a controlled national study. Sleep Med. 2017;29:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson PJ. Assessment and development of executive function (EF) during childhood. Child Neuropsychol. 2002;8(2):71–82. doi: 10.1076/chin.8.2.71.8724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.