Abstract

Imaging in small animal models of lung disease is challenging, as existing technologies are limited either by resolution or by the terminal nature of the imaging approach. Here, we describe the current state of small animal lung imaging, the technological advances of laboratory-sourced phase contrast X-ray imaging, and the application of this novel technology and its attendant image analysis techniques to the in vivo imaging of the large airways and pulmonary vasculature in murine models of lung health and disease.

Keywords: imaging, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary circulation

Small animal lung imaging

Small animal models are critical to understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms of lung diseases and for testing potential therapeutic agents. Models of emphysema,1,2 pulmonary hypertension (PH),3–8 acute lung injury,9–12 pulmonary fibrosis,13,14 and others have been developed that mimic the physiology and pathology of the human diseases. However, physiologic read-outs—such as pulmonary function tests—or post-mortem assessments—such as isolated perfused lung techniques, histology, and bronchoalveolar lavage—do not reflect the full spectrum of the disease process. These measures are either insensitive to focal lesions or early disease (pulmonary function tests) or require sacrifice of the animal to obtain data and therefore preclude longitudinal assessment (histology, isolated perfused lung, bronchoalveolar lavage).

Recently, in vivo imaging techniques have emerged as an important adjunct methodology in small animal research on lung diseases, as these methods allow measurements in the same animals over time or in response to therapy. For example, bioluminescence imaging takes advantage of the enzyme luciferase: when the substrate luciferin is present, it causes visible light to be emitted that can be detected through several centimeters of tissue. Luciferase can be introduced as a reporter gene under a promoter of interest or as an ubiquitously expressed enzyme in a cell type of interest. For example, Blackwell et al. engineered a transgenic line of mice with a promoter that is highly responsive to NF-κB activity (HIV-1 long terminal repeat) to drive the expression of Photinus luciferase.15,16 Using this strain, they were able to characterize NF-κB activation in real time and over time in the lungs in response to systemic lipopolysaccharide (LPS),4 Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia,17 and tumor metastases.18 Bioluminescence imaging can also be used with lung cancer cell lines and bacteria expressing luciferase to track tumor growth, infections, and responses to therapies.16,19,20 Limitations of detecting luciferase-generated photons (500–700 nm wavelength) include relatively poor spatial resolution due to light scattering in tissues21,22 and weak tissue penetration related to photon adsorption, resulting in approximately tenfold signal attenuation per cm of tissue.16,22 Nevertheless, bioluminescence imaging confers several powerful advantages—including the ability to image the same animals over time with repeated injections of the non-toxic substrate luciferin and the use of reporter gene strategies. Furthermore, further advances are expected as detectors and analysis methods improve.

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) imaging uses a cone-beam X-ray source and two-dimensional (2D) detector, with the sample or the source and detector rotated through 360°. Micro-CT scanners have a much smaller field of view (typically 1–5 cm wide) in comparison to clinical CT scanners which are targeted towards full human body scans (30–40 cm in width). Because of the smaller field of view, micro-CT scanners are more sensitive to X-ray energy compared to clinical scanners.23 Image quality in CT scans is highly dependent on the target area (spot size) over which the electron beam interacts. Specifically, for lung imaging, as spot size increases, the amount of speckle in the acquired images is reduced and eventually results in a smooth image without distinct surface boundaries.24 Most laboratory-based micro-CT scanners utilize fixed microfocus X-ray targets with spot sizes as small as 5 µm.25 The ability to modify the cone-beam propagation distance to adjust magnification in combination with microfocus of the electron beam allows for micro-CT scanners to produce significantly higher spatial resolutions over conventional CT scanners, to the order of 20–100 µm.23,26 Several hundred images are captured during a micro-CT scan from different angular views that are interpolated across different planes to produce a three-dimensional (3D) volume through which cross-sectional slices can be taken. The angular projections acquired during micro-CT scans require image reconstruction through a processing algorithm (filtered back projection) which incorporates the angles of each image to reconstruct the original object being imaged.27,28 Micro-CT and post-acquisition image analysis algorithms are widely used in murine and rat models of emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis, and are able to detect changes in lung density over the respiratory cycle as well as over days to weeks from the induction of lung disease.29–33 The advantages of micro-CT imaging include the high resolution, quantitative 3D reconstructions of lung anatomy34 and the ability to perform inspiratory and expiratory scans to determine air trapping and density assessments that correlate with degrees of disease.32,35,36 Limitations to micro-CT imaging include relatively poor soft-tissue contrast, cardiac and respiratory motion artifact—although advances in cardiac and respiratory gating techniques have reduced this effect28,32—and a potential adverse impact of repeated radiation exposure in susceptible strains of mice.34 An excellent 2014 review of small animal micro-CT imaging by Clark and Badea discusses the technology and its applications in depth.28

Other techniques such as hyperpolarized magnetic resonance imaging (HP MRI) and micro-positron emission tomography (micro-PET) imaging can provide unique functional and metabolic information about the state of diseased lungs. Dr. Rizi’s group, for example, used HP MRI to determine the apparent diffusion coefficient in rat models of emphysema as a non-invasive measure of airspace enlargement,37 as well as to measure lactate-to-pyruvate ratios in a rat model of acute lung injury.38 Micro-PET, with a resolution of 1–1.4 mm,26,39 has been used in mice to detect lung metastases26 and to measure glucose uptake in a model of acute lung injury,40 to name just a few examples. These techniques require specialized facilities to generate tracers and sophisticated analysis by experts in the field.

Finally, confocal and two-photon microscopy have allowed for elegant and detailed studies of alveolar epithelial–endothelial interactions and immune cell migration and inter-cellular dynamics in the lungs of live mice via either a thoracic window or isolated blood-perfused lungs,41–47 as well as calcium wave propagation and oxygen saturation mapping.48–50 These techniques have resolutions of < 1 µm43 and provide unique information unobtainable by non-invasive imaging modalities, but by their nature are not able to provide global read-outs of the lung function or responses to treatment. Table 1 compares some of the advantages and limitations of current small animal imaging lung imaging technologies.

Table 1.

In vivo Imaging Modalities for Small Animal Models of Lung Disease.

| In vivo lung imaging approach | Resolution | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioluminescence | Poor | - Repeated measurements over days-weeks - Non-toxic agent - Can use luciferin as reporter for gene of interest | - Low resolution - Semi-quantitative due to caveats about tissue attenuation of light - Limited depth of penetration |

| Micro-CT | 50–100 µm | - Repeated imaging over days/weeks - Functional data on air-trapping and tissue density - Widely available and widely applied to lung disease models | - Concerns re radiation exposure with repeated imaging - Low soft-tissue contrast - Respiratory/cardiac gating needed for best images - Limited opportunity for metabolic reporting |

| Hyperpolarized MRI | 500 µm | - Repeated imaging over days/weeks - Functional information about gas diffusion, tissue metabolism, ventilation - No radiation | - Requires polarizer on site - Requires sophisticated expertise to analyze signals - Limited opportunity for tissue structure/density reporting |

| Micro-PET | 1–1.4 mm | - Repeated imaging over days-weeks - Can provide information about lung tissue metabolism (glucose uptake, etc.) - Can detect lung metastases in cancer models - Potential for targeted tracer design/use | - Low resolution - Requires cyclotron on site to generate novel targeted tracers |

| Confocal/Two-photon microscopy | 1 µm | - Extremely high resolution - Able to image dynamics of individual cells in alveoli and capillaries - Can label cells/structures with fluorescent tags - Can visualize response in real time to perturbations to system | - Terminal procedure - Focal window into lung response (does not give global data for lung) - Limited depth of penetration |

| Phase contrast X-ray CT | 10 µm | - Repeated imaging over days/weeks - Significant resolution advantage compared with micro-CT - Enhanced soft-tissue contrast for advanced segmentation analysis of vessels, airways - Speckles allow particle-image velocimetry analysis, yielding detailed information about regional tissue motion and lung function | - Requires synchrotron or special equipment for coherent X-ray source - Concerns re radiation exposure with repeated imaging - Respiratory/cardiac gating needed for best images - Limited opportunity for metabolic reporting |

Quantitative imaging of the pulmonary vasculature in small animal studies has been more challenging. Contrast agents can be injected intravenously for in vivo imaging,51 but are cleared quickly and require catheter placement, which can be time-consuming and physiologically stressful. Moreover, this approach prevents repeat imaging in the same animal over days to weeks and requires synchrotron radiation for high-resolution images to be obtained.52,53 Detailed imaging of the vasculature in mice has therefore largely relied upon in vivo resin instillation and ex vivo imaging of individual lobes using high-resolution micro-CT.30,34,54–56 Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging has been able to estimate ventilation/perfusion ratios with some success,57 although low resolution of around 1.3 mm is an inherent limitation of the technique.26 Another approach is to inject fluorescent microspheres, either of different sizes or at different times, and analyze the patterns of deposition to determine patterns of pulmonary blood flow in response to stimuli.58 This technique, while able to capture changes in regional pulmonary blood flow over the course of an experiment, ultimately requires animal sacrifice at the end of the experiment to analyze microsphere deposition, precluding long-term assessments in the same animal. Finally, echocardiography can be used to measure the effects of pulmonary vascular disease such as PH on right ventricular remodeling.59 However, none of these techniques permit high-resolution, quantitative measurements of the vasculature in small animal models of lung disease over time in the same animal.

Therefore, although significant recent advances in small animal in vivo lung imaging techniques have allowed researchers to characterize lung structure, function, and metabolism to a much greater extent than in prior decades, there is still room for improvement, particularly in the realm of high-resolution imaging of lung structures and regional tissue motion characterization over the respiratory cycle. Phase contrast X-ray imaging is a unique form of X-ray imaging that is enhanced by the multiple air-tissue interfaces found in the lungs. This technique generates granular images of the lungs in small animals with a resolution of approximately 10 µm.60,61 Because it requires highly coherent X-rays, phase contrast X-ray imaging could previously only be performed in a synchrotron; however, recent advances have made it possible to perform this imaging in a laboratory setting.62 Here, we describe the technology behind this approach and how we have applied it to obtain detailed, quantitative images of the pulmonary vasculature and changes in upper airway motion due to mechanical ventilation in live mice.

Phase contrast X-ray technology

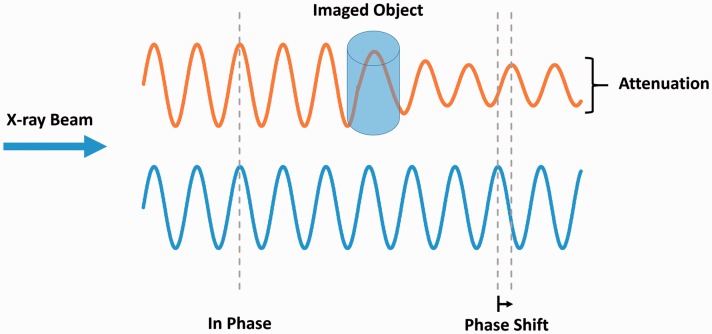

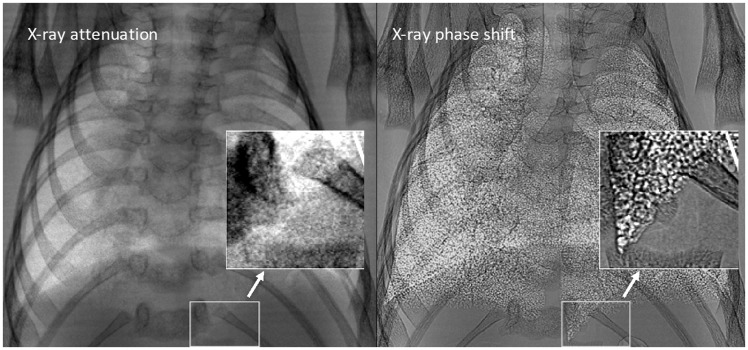

X-ray imaging typically consists of electromagnetic radiation traveling in waves which pass through various tissues in the body. The interaction between X-rays and tissue results in electromagnetic radiation being absorbed by some tissues and refracted by others. As X-rays interact with different tissues, both the amplitude (attenuation) and phase of the X-ray wave are altered (Fig. 1). Although attenuation-based X-ray imaging is most common in both clinical and pre-clinical studies, this approach yields limited contrast and has restrictive resolution for soft tissue imaging. X-ray phase shift is more effective in less absorbant tissues with air-tissue interfaces such as the lungs, resulting in increased image contrast and tissue edge detail (Fig. 2).63,64

Fig. 1.

X-ray phase shift. X-ray wave passing through an object results in a change in both attenuation and phase.

Fig. 2.

Mouse lung phase contrast X-ray. Differences between typical lung X-ray image (left) and phase shifted lung X-ray (right). Distinct increases in contrast and tissue boundary detail are shown due to the phase shift. Adapted with permission from Lewis et al.64 © Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine. Reproduced by permission of IOP Publishing. All rights reserved.

One of the challenges with phase contrast imaging is the reliance on an X-ray source that is both brilliant and highly coherent,65 which previously required synchrontron-based sources.62,66 More recently, however, through the use of grated interferometry67 and propagation-based X-ray sources, phase contrast imaging can be performed using laboratory sources.68–70 This advance significantly expands researchers’ ability to apply the highly detailed imaging capability of phase contrast X-rays to small animal models of lung disease.

Particle image velocimetry

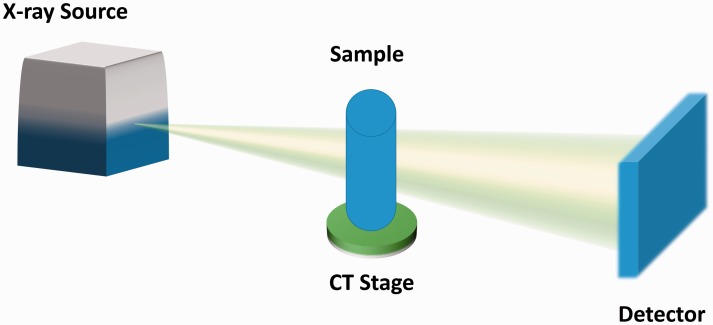

The functional lung imaging described here is based on particle image velocimetry (PIV) on a laboratory X-ray source (Fig. 3). Conventional PIV utilizes tracer particles to determine the velocity of the flow by comparing two images acquired with a known time differential. In the case of functional lung imaging, the speckled pattern of the lung tissue from phase contrast images is used to track the direction in which the lung tissue is moving.71 This process is iteratively conducted across the entire lung, and a displacement and consequent velocity map can be calculated which shows lung tissue movement over time.72

Fig. 3.

Laboratory X-ray image acquisition set-up. A propagation-based X-ray source is used to produce a cone-shaped X-ray beam. The beam interacts with the sample (rotating on a CT stage) resulting in a change in the X-ray beam phase and intensity. The corresponding changes in the X-ray beam are acquired through a flat panel detector. Images are then combined and used to produce a reconstruction of the sample.

Segmentation and quantitative analysis of the murine pulmonary vasculature without IV contrast

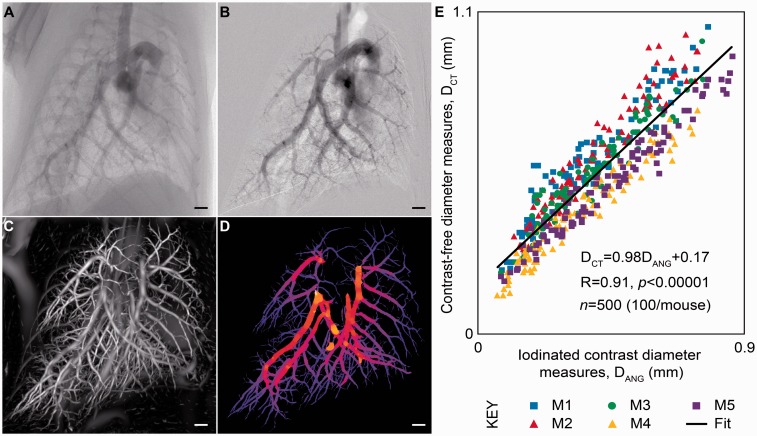

Phase contrast imaging in small animals generates high-resolution data that permit sophisticated post-image acquisition analysis. In particular, it is possible to apply a method originally reported by Frangi et al.73 to generate a 3D vascular tree from a CT scan performed without intravenous contrast. This method involves filtering data based on tissue densities and then growing the vessel structures based on the probability of an item of the correct density being part of a tube. This 3D construct of the pulmonary vessels contains thousands of data points of vascular diameters, which are measured in a radial fashion from the centerline tree.

To validate this method, Samarage et al.74 performed a traditional angiogram with a contrast injection via a right internal jugular catheter in five mice. They were able to obtain high-resolution images of the angiograms by taking advantage of the phase contrast approach on a propagation-based X-ray source (Fig. 4a and b). These researchers then performed phase contrast CT scans in the same mice without the use of IV contrast (which clears quickly from mice) and reconstructed the vascular trees as described above (Fig. 4c and d). They identified the same vessels on the angiogram and the non-contrast reconstructed vascular trees for each mouse and compared vessel diameter measurements between the two methods (Fig. 4e). Over 490 vessels were measured, with an excellent correlation (R2 = 0.85) between diameter measurements obtained from the traditional angiography approach and the non-contrast reconstruction of the vascular tree.74 We are now applying this non-contrast vascular reconstruction technique, termed “contrast-free pulmonary angiography,” to the analysis of vascular responses to acute lung injury and acute hypoxia. Other obvious applications include measuring vasculopathy—and responses to therapies—in mouse and rat models of PH. This is possible because the imaging approach is non-invasive and non-lethal, allowing repeat observations and measurements in the same animal over time.

Fig. 4.

Contrast-free pulmonary angiography. (a, b) Vasculature visualized using IV contrast for traditional 2D pulmonary angiography. (c, d) 3D reconstruction of the pulmonary vasculature from novel image analysis of a phase contrast CT scan in the same mouse. (e) Measurements of vascular diameters obtained by each method show strong correlation across a wide range of values. Adapted with permission from Samarage et al.74

Airway motion over the respiratory cycle during prolonged mechanical ventilation

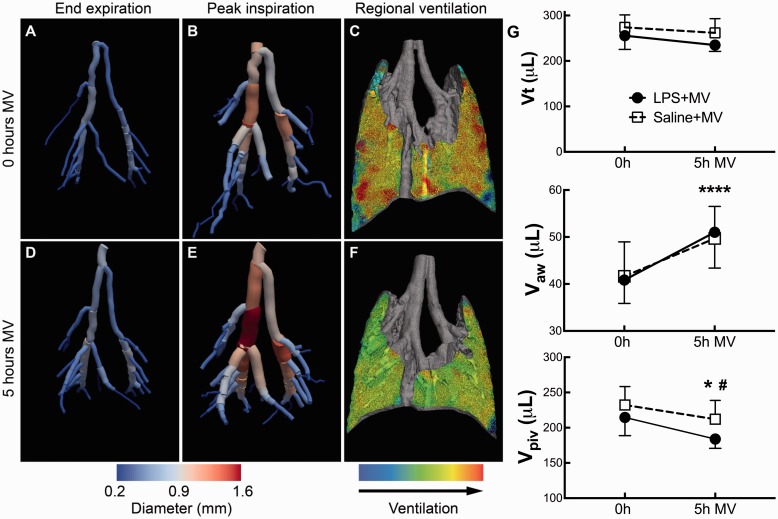

We are able to quantify how lung tissue and airways move during the respiratory cycle in small animals by PIV analysis as described above. Additionally, we can use filtering and skeletonization image analysis to segment the airways, similar to the approach we used for contrast-free pulmonary angiography. We employed this approach in a murine model of two-hit acute lung injury (with intratracheal LPS and mechanical ventilation) and found that the large airways expanded during inspiration on positive pressure ventilation (Fig. 5a and b). We imaged each mouse again after 5 h of mechanical ventilation and found that the large airways showed significantly increased expansion over the respiratory cycle, independent of LPS treatment (Fig. 5d and e). Interestingly, we noted that although the total tidal volumes did not change, the distribution of the tidal volumes shifted from expansion of the parenchyma to expansion of the airways (Fig. 5g).75 Our team first noticed this phenomenon by visual inspection of 3D tissue expansion maps generated by PIV analysis. This example not only demonstrates the value of visual data in generating hypotheses, but also the power of this technique for quantifying changes in airway volumes on the scale of microliters and its novel ability to detect changes in lung function that are not revealed by global pulmonary function tests. Potential applications of the airway expansion analysis include determinations of airway volumes and compliance in murine models of airway disease such as asthma or bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Fig. 5.

Large airways expansion in mice during mechanical ventilation (MV). (a, b) Airway reconstructions from phase contrast CT data and segmentation in a mouse show increased airway size at peak inspiration. (c) Lung parenchyma expansion in the same mouse generated with particle-image velocimetry. (d–f) After 5 h MV, the large airways expansion is increased, while parenchymal expansion is decreased. (g) Total tidal volume (Vt) is unchanged after 5 h MV, but airway volumes (Vaw) are increased while parenchymal volumes (Vpiv) are decreased. Adapted with permission from Kim et al.75

Summary

X-ray-based phase contrast imaging takes advantage of the enhanced contrast generated by air–tissue interfaces and therefore is ideal for in vivo imaging in small animal models of lung diseases. The high-resolution images created by phase contrast X-ray imaging permit sophisticated image analysis techniques such as particle image velocimetry, which measures tissue expansion over the respiratory cycle on a voxel-by-voxel basis. Segmentation approaches can be applied to phase contrast CT scans to generate 3D reconstructions of the pulmonary vasculature and airways, allowing detailed quantitative assessments of vessel diameters and airway volumes. Furthermore, propagation-based X-rays can now be generated outside of a synchrotron setting, allowing for widespread use of these techniques by researchers. This non-invasive and non-lethal imaging can be performed repeatedly in the same animal over spans of hours, days, or weeks. One aspect of this imaging that requires further investigation is the impact of radiation exposure, which, similar to conventional micro-CT approaches, may be a source of toxicity, especially in animals with DNA-repair defects (David Habiel and Cory Hogaboam, personal communication 2017); we are actively exploring this as a potential caveat to multiple repeated exposures, in particular for long time courses when such an effect may be of consequence. Nevertheless, this technology provides a powerful new tool for quantitative and longitudinal analysis in pre-clinical models of lung disease. Future applications include assessments of pulmonary vasculopathies such as PH, airway diseases such as asthma, and parenchymal diseases such as acute lung injury and pulmonary fibrosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Rahim Rizi, Timothy Blackwell, Jahar Bhattacharya, and Glyn Jones for helpful discussions and edits.

Conflict of interest

HJ has purchased stock in 4Dx, a company that develops software for PIV-based lung imaging and hardware for laboratory propagation-based X-ray sources.

Funding

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant K08HL125806 (HJ).

2017 Grover Conference Series

This review article is part of the 2017 Grover Conference Series. The American Thoracic Society and the conference organizing committee gratefully acknowledge the educational grants provided for the support of this conference by Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc., Gilead Sciences, Inc., and United Therapeutics Corporation. Additionally, the American Thoracic Society is grateful for the support of the Grover Conference by the American Heart Association, the Cardiovascular Medical Research and Education Fund, and the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Clauss M, Voswinckel R, Rajashekhar G, et al. Lung endothelial monocyte-activating protein 2 is a mediator of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 2470–2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrache I, Natarajan V, Zhen L, et al. Ceramide upregulation causes pulmonary cell apoptosis and emphysema-like disease in mice. Nat Med 2005; 11: 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asosingh K, Farha S, Lichtin A, et al. Pulmonary vascular disease in mice xenografted with human BM progenitors from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Blood 2012; 120: 1218–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitling S, Krauszman A, Parihar R, et al. Dose-dependent, therapeutic potential of angiotensin-(1-7) for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 2015; 5: 649–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campen MJ, Shimoda LA, O’Donnell CP. Acute and chronic cardiovascular effects of intermittent hypoxia in C57BL/6J mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005; 99: 2028–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Tang H, Sysol JR, et al. The sphingosine kinase 1/sphingosine-1-phosphate pathway in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190: 1032–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pugliese SC, Kumar S, Janssen WJ, et al. A time- and compartment-specific activation of lung macrophages in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. J Immunol 2017; 198: 4802–4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimoda LA, Laurie SS. Vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013; 91: 297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones HD, Crother TR, Gonazalez R, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is required for the development of hypoxemia in LPS/mechanical ventilation acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014; 50: 270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011; 44: 725–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiss LK, Uhlig U, Uhlig S. Models and mechanisms of acute lung injury caused by direct insults. Eur J Cell Biol 2012; 91: 590–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaschetto R, Kuiper JW, Chiang SR, et al. Inhibition of poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase attenuates ventilator-induced lung injury. Anesthesiology 2008; 108: 261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gharib SA, Johnston LK, Huizar I, et al. MMP28 promotes macrophage polarization toward M2 cells and augments pulmonary fibrosis. J Leukoc Biol 2014; 95: 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray LA, Zhang H, Oak SR, et al. Targeting interleukin-13 with tralokinumab attenuates lung fibrosis and epithelial damage in a humanized SCID idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014; 50: 985–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackwell TS, Yull FE, Chen CL, et al. Multiorgan nuclear factor kappa B activation in a transgenic mouse model of systemic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162: 1095–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadikot RT, Blackwell TS. Bioluminescence imaging. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2005; 2: 537–540, 511–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadikot RT, Zeng H, Yull FE, et al. p47phox deficiency impairs NF-kappa B activation and host defense in Pseudomonas pneumonia. J Immunol 2004; 172: 1801–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stathopoulos GT, Sherrill TP, Han W, et al. Use of bioluminescent imaging to investigate the role of nuclear factor-kappaBeta in experimental non-small cell lung cancer metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 2008; 25: 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis KP, Yu J, Bellinger-Kawahara C, et al. Visualizing pneumococcal infections in the lungs of live mice using bioluminescent Streptococcus pneumoniae transformed with a novel gram-positive lux transposon. Infect Immun 2001; 69: 3350–3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li B, Torossian A, Li W, et al. A novel bioluminescence orthotopic mouse model for advanced lung cancer. Radiat Res 2011; 176: 486–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edinger M, Cao YA, Hornig YS, et al. Advancing animal models of neoplasia through in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Eur J Cancer 2002; 38: 2128–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luker KE, Luker GD. Bioluminescence imaging of reporter mice for studies of infection and inflammation. Antiviral Res 2010; 86: 93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulus MJ, Gleason SS, Kennel SJ, et al. High resolution X-ray computed tomography: an emerging tool for small animal cancer research. Neoplasia 2000; 2: 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garson AB, Izaguirre EW, Price SG, et al. Characterization of speckle in lung images acquired with a benchtop in-line x-ray phase-contrast system. Phys Med Biol 2013; 58: 4237–4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flynn M, Hames S, Reimann D, et al. Microfocus X-ray sources for 3-D microtomography. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res Sect A 1994; 353: 312–315. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koba W, Jelicks LA, Fine EJ. MicroPET/SPECT/CT imaging of small animal models of disease. Am J Pathol 2013; 182: 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boerckel JD, Mason DE, McDermott AM, et al. Microcomputed tomography: approaches and applications in bioengineering. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014; 5: 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark DP, Badea CT. Micro-CT of rodents: state-of-the-art and future perspectives. Phys Med 2014; 30: 619–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell RD, Rudmann C, Wood RW, et al. Longitudinal micro-CT as an outcome measure of interstitial lung disease in TNF-transgenic mice. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0190678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faight EM, Verdelis K, Zourelias L, et al. MicroCT analysis of vascular morphometry: a comparison of right lung lobes in the SUGEN/hypoxic rat model of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 2017; 7: 522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gammon ST, Foje N, Brewer EM, et al. Preclinical anatomical, molecular, and functional imaging of the lung with multiple modalities. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2014; 306: L897–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki M, Chubachi S, Kameyama N, et al. Evaluation of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice using quantitative micro-computed tomography. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015; 308: L1039–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Z, Kozlowski J, Schuster DP. Physiologic, biochemical, and imaging characterization of acute lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172: 344–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritman EL. Micro-computed tomography of the lungs and pulmonary-vascular system. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2005; 2: 477–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson KA. Imaging techniques for small animal imaging models of pulmonary disease: micro-CT. Toxicol Pathol 2007; 35: 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y, Chen H, Ambalavanan N, et al. Noninvasive imaging of experimental lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015; 53: 8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xin Y, Cereda M, Kadlecek S, et al. Hyperpolarized gas diffusion MRI of biphasic lung inflation in short- and long-term emphysema models. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2017; 313: L305–L312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pourfathi M, Xin Y, Kadlecek SJ, et al. In vivo imaging of the progression of acute lung injury using hyperpolarized [1-13 C] pyruvate. Magn Reson Med 2017; 78: 2106–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fine EJ, Herbst L, Jelicks LA, et al. Small-animal research imaging devices. Semin Nucl Med 2014; 44: 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Z, Kozlowski J, Goodrich AL, et al. Molecular imaging of lung glucose uptake after endotoxin in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005; 289: L760–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Issekutz AC, et al. Pressure-induced leukocyte margination in lung postcapillary venules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005; 289: L407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Lindert J, et al. Lung surfactant secretion by interalveolar Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006; 291: L596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Islam MN, Das SR, Emin MT, et al. Mitochondrial transfer from bone-marrow-derived stromal cells to pulmonary alveoli protects against acute lung injury. Nat Med 2012; 18: 759–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kreisel D, Nava RG, Li W, et al. In vivo two-photon imaging reveals monocyte-dependent neutrophil extravasation during pulmonary inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 18073–18078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuebler WM, Parthasarathi K, Lindert J, et al. Real-time lung microscopy. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007; 102: 1255–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Looney MR, Thornton EE, Sen D, et al. Stabilized imaging of immune surveillance in the mouse lung. Nat Methods 2011; 8: 91–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westphalen K, Gusarova GA, Islam MN, et al. Sessile alveolar macrophages communicate with alveolar epithelium to modulate immunity. Nature 2014; 506: 503–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldenberg NM, Wang L, Ranke H, et al. TRPV4 Is required for hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Anesthesiology 2015; 122: 1338–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuebler WM. Real-time imaging assessment of pulmonary vascular responses. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2011; 8: 458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang L, Yin J, Nickles HT, et al. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction requires connexin 40-mediated endothelial signal conduction. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 4218–4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwenke DO, Pearson JT, Umetani K, et al. Imaging of the pulmonary circulation in the closed-chest rat using synchrotron radiation microangiography. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007; 102: 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lang JA, Pearson JT, te Pas AB, et al. Ventilation/perfusion mismatch during lung aeration at birth. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014; 117: 535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sonobe T, Schwenke DO, Pearson JT, et al. Imaging of the closed-chest mouse pulmonary circulation using synchrotron radiation microangiography. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011; 111: 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lachant D, Haight D, Glickman SR, et al. Combination ambrisentan and tadalafil preserve vascular volume quantified by micro CT better than either monotherapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193: A3892. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molthen RC, Karau KL, Dawson CA. Quantitative models of the rat pulmonary arterial tree morphometry applied to hypoxia-induced arterial remodeling. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004; 97: 2372–2384. discussion 2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phillips MR, Moore SM, Shah M, et al. A method for evaluating the murine pulmonary vasculature using micro-computed tomography. J Surg Res 2017; 207: 115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jobse BN, Rhem RG, McCurry CA, et al. Imaging lung function in mice using SPECT/CT and per-voxel analysis. PLoS One 2012; 7: e42187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luchtel DL, Boykin JC, Bernard SL, et al. Histological methods to determine blood flow distribution with fluorescent microspheres. Biotech Histochem 1998; 73: 291–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mendes-Ferreira P, Santos-Ribeiro D, Adão R, et al. Distinct right ventricle remodeling in response to pressure overload in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2016; 311: H85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kitchen MJ, Paganin D, Lewis RA, et al. Analysis of speckle patterns in phase contrast images of lung tissue. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 205; 548: 240–246.

- 61.Larsson DH, Vågberg W, Yaroshenko A, et al. High-resolution short-exposure small-animal laboratory x-ray phase-contrast tomography. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 39074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tuohimaa T, Otendal M, Hertz HM. Phase-contrast X-ray imaging with a liquid-metal-jet-anode microfocus source. Apple Phys Lett 2007; 91: 074104. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Henke BL, Gullikson EM, Davis JC. X-ray interactions: photoabsorption, scattering, transmission, and reflection at E = 50–30,000 eV, Z = 1–92. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 1993; 54: 181–342. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewis RA, Yagi N, Kitchen MJ, et al. Dynamic imaging of the lungs using x-ray phase contrast. Phys Med Biol 2005; 50: 5031–5040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fouras A, Kitchen MJ, Dubsky S, et al. The past, present, and future of X-ray technology for in vivo imaging of function and form. J Appl Phys 2009; 105: 1002009. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bech M, Tapfer A, Velroyen A, et al. In-vivo dark-field and phase-contrast x-ray imaging. Sci Rep 2013; 3: 3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwab F, Schleede S, Hahn D, et al. Comparison of contrast-to-noise ratios of transmission and dark-field signal in grating-based X-ray imaging for healthy murine lung tissue. Z Med Phys 2013; 23: 236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bravin A, Coan P, Suortti P. X-ray phase-contrast imaging: from pre-clinical applications towards clinics. Phys Med Biol 2013; 58: R1–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pfeiffer F, Bech M, Bunk O, et al. Hard-X-ray dark-field imaging using a grating interferometer. Nat Mater 2008; 7: 134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou T, Lundström U, Thüring T, et al. Comparison of two x-ray phase-contrast imaging methods with a microfocus source. Opt Express 2013; 21: 30183–30195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dubsky S, Hooper SB, Siu KK, et al. Synchrotron-based dynamic computed tomography of tissue motion for regional lung function measurement. J R Soc Interface 2012; 9: 2213–2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dubsky S, Thurgood J, Henon Y, et al. A low dose, high spatio-temporal resolution system for real-time four-dimensional lung function imaging. In: C36 Imaging and the Lung: A Rapidly Evolving Field. New York, NY: American Thoracic Society, 2014, p. A4316.

- 73.Frangi AF, Niessen WJ, Vincken KL, et al. Multiscale vessel enhancement filtering. In: Wells WM, Colchester A, Delp SL. (Eds.) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1998, pp. 130–137.

- 74.Samarage CR, Carnibella R, Preissner M, et al. Technical Note: Contrast free angiography of the pulmonary vasculature in live mice using a laboratory x-ray source. Med Phys 2016; 43: 6017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim EH, Preissner M, Carnibella RP, et al. Novel analysis of 4DCT imaging quantifies progressive increases in anatomic dead space during mechanical ventilation in mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2017; 123: 578–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]