Abstract

Sulfite reductase (SiR) catalyzes the reduction of sulfite to sulfide in chloroplasts and root plastids using ferredoxin (Fd) as an electron donor. Using purified maize (Zea mays L.) SiR and isoproteins of Fd and Fd-NADP+ reductase (FNR), we reconstituted illuminated thylakoid membrane- and NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction systems. Fd I and L-FNR were distributed in leaves and Fd III and R-FNR in roots. The stromal concentrations of SiR and Fd I were estimated at 1.2 and 37 μm, respectively. The molar ratio of Fd III to SiR in root plastids was approximately 3:1. Photoreduced Fd I and Fd III showed a comparable ability to donate electrons to SiR. In contrast, when being reduced with NADPH via FNRs, Fd III showed a several-fold higher activity than Fd I. Fd III and R-FNR showed the highest rate of sulfite reduction among all combinations tested. NADP+ decreased the rate of sulfite reduction in a dose-dependent manner. These results demonstrate that the participation of Fd III and high NADPH/NADP+ ratio are crucial for non-photosynthetic sulfite reduction. In accordance with this view, a cysteine-auxotrophic Escherichia coli mutant defective for NADPH-dependent SiR was rescued by co-expression of maize SiR with Fd III but not with Fd I.

In higher plants, reductive assimilation of inorganic sulfate to sulfide is an essential metabolic process for the synthesis of sulfur-containing compounds such as amino acids, sulfolipids, and coenzymes (Leustek and Saito, 1999). Sulfate is activated to adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (APS) by ATP sulfurylase, and APS reductase catalyzes a direct reduction of APS to sulfite, which is further reduced to sulfide by sulfite reductase (SiR). Finally, Cys is formed when sulfide is incorporated into O-acetylserine by Cys synthase (CS). In some bacteria, 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS), converted from APS by APS kinase, is an another activated form of sulfate, and in this case PAPS is reduced to free sulfite by PAPS reductase. This is considered to be a minor pathway in higher plants (Saito, 1999).

APS reductase, SiR, and PAPS reductase catalyze oxidation-reduction reactions and require reductant for their catalytic action. Genes for APS reductase (Gutierrez-Marcos et al., 1996; Setya et al., 1996) and SiR (Bork et al., 1998; Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 1998) have been cloned from higher plants, and both enzymes are known to be plastid proteins, synthesized as a larger precursor with a transit peptide for the organelle localization. These two enzymes primarily depend on photosynthetically generated reductant. APS reductase has a thioredoxin/glutaredoxin-like domain that accepts electrons through glutathione (Bick et al., 1998). SiR contains an iron-sulfur cluster and a siroheme for redox centers and utilizes ferredoxin (Fd) as an electron donor (Aketagawa and Tamura, 1980; Krueger and Siegel, 1982).

Reductive sulfate assimilation also occurs in non-photosynthetic organs of higher plants. Most enzymes for sulfur assimilation exist in substantial amounts in roots (Brunold and Suter, 1989), and the capacity of sulfur assimilation in roots is remarkably increased in response to stresses such as exposure to heavy metals (Rüegsegger and Brunold, 1992) and herbicide safeners (Farago and Brunold, 1990). This is due to the synthesis of Cys and glutathione for phytochelation and herbicide conjugation.

Despite the potential capacity of sulfur assimilation in roots, there is little information about the reductant supply system(s) operating for support of the reductive pathways. We have been focusing on SiR to study such reductant systems. SiR is encoded by a single gene, which is expressed both in non-photosynthetic and photosynthetic organs (Bork et al., 1998; Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 1998). The step of sulfite reduction in non-photosynthetic plastids proceeds in a Fd-dependent manner as in chloroplasts but using non-photosynthetic reducing power. It has been proposed that electrons from NADPH, which is provided from the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, are donated to two Fd-dependent enzymes, nitrite reductase (NiR) and Glu synthase (GOGAT), via Fd-NADP+ reductase (FNR) (Bowsher et al., 1989, 1992).

Fd is known to be distributed in photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic organs as distinct isoproteins in several higher plants (Wada et al., 1986; Kimata and Hase, 1989; Green et al., 1991; Alonso et al., 1995). In maize (Zea mays L.), at least six Fd isoproteins (Fd I–Fd VI) have been identified at both the protein and gene levels (Hase et al., 1991a; Matsumura et al., 1997). The six isoproteins are divided into two major groups, photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic Fds, based on characteristics of organ distributions and gene expressions. Fd I and Fd III are the major Fd isoproteins in leaves and roots, respectively, and differ in the redox potential of the [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fd I: −423 mV, Fd III: −345 mV) (Akashi et al., 1997). Recently, cDNAs encoding root-type FNR were cloned from maize (Ritchie et al., 1994) and rice (Aoki et al., 1995). The homology between these root-type FNR isoproteins is considerably higher (about 90% at amino acid identity) than the homology with their counterparts in leaves (40%–50% at amino acid identity). It is likely that the presence of these organ-specific Fd and FNR isoproteins is due to the requirement for different reductant allocation systems for Fd-dependent enzymes in photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic organs.

In this study, in vitro sulfite reduction systems operating in photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic plastids were reconstituted using purified maize SiR, Fd, and FNR. We examined the organ-specific isoproteins of Fd and FNR for their ability to act as a reductant supply to SiR, and report here that the use of the root isoproteins is essential for supporting efficient sulfite reduction in non-photosynthetic organs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Maize (Zea mays L. cv Golden Cross Bantam T51) seedlings were grown for 11 d on vermiculite with Hoagland nutrients (Arnon and Hoagland, 1940) under fluorescent light at an intensity of about 700 μE m−2 s−1. The photoperiod was 14 h (day)/10 h (night) and the temperature was 28°C (day)/20°C (night). Primary leaves, third leaves, and roots were harvested and stored at −80°C.

Extraction, Electrophoresis, and Western Analysis

About 1 g of each tissue was ground with a mortar and pestle with 0.1 g of polyclar AT and a small amount of sea sand in 2 volumes of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The homogenate was centrifuged at 2,000g for 1 min and the resulting crude extract was boiled with 1% (w/v) SDS for 3 min; alternatively, 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100 was added to the solubilized membrane particle. Extracts were then further centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 min to remove insoluble materials. SiR and Fd isoproteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and non-denaturing PAGE, as described previously (Kimata and Hase, 1898; Matsumura et al., 1999), followed by western blotting according to the method of Towbin et al. (1979). Immunological detection was carried out using rabbit antibodies against SiR or Fds. The detected signals were quantitated based on the standard blot of purified recombinant proteins by the densitometric analysis program NIH Image (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Preparation of Recombinant SiR, Fd Isoproteins, and FNR Isozymes

Recombinant SiR (Ideguchi et al., 1995), Fd I (Matsumura et al., 1997), and Fd III (Hase et al., 1991b) were prepared using Escherichia coli expression systems. Purification of recombinant leaf (L)-FNR and root (R)-FNR will be published elsewhere (Y. Onda and T. Hase, unpublished data). The concentration of SiR, Fds, and FNRs were determined spectrophotometrically (Akashi et al., 1999).

Assay of SiR Activity

Photoreduction of Sulfite

SiR activity was measured using photoreduced Fd I or Fd III as electron donors. The assay mixture contained in a final volume of 1.0 mL: 50 μmol of Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 μmol of NaCl, 5 μmol of MgCl2, 0.5 μmol of Na2SO3, 12.5 μmol of O-acetyl-l-Ser, 20 nmol of Fd, 0.1 nmol of SiR, 40 μg of Chl spinach thylakoid membranes, and an excess amount of Cys synthase. The mixture was illuminated with red LEDs at an intensity of about 200 μE m−2 s−1 at 30°C. Trichloroacetic acid was added to a final concentration of 5% (w/v) to aliquots of the mixture. After removal of the precipitation, the amount of Cys formed was determined with an acid ninhydrin reaction (Arb and Brunold, 1983).

NADPH-Dependent Sulfite Reduction

An electron transfer pathway from NADPH to Fd was reconstituted using FNR. SiR activity was measured using this reduction system with a combination of L-FNR/Fd I, L-FNR/Fd III, R-FNR/Fd I, or R-FNR/Fd III. The assay mixture contained in a final volume of 1.0 mL: 50 μmol of Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 μmol of NaCl, 5 μmol of MgCl2, 0.5 μmol of Na2SO3, 12.5 μmol of O-acetyl-l-Ser, 2 μmol of NADPH, 5 μmol of Glc-6-P, 1 nmol of FNR, 20 nmol of Fd, 0.1 nmol of SiR, and an excess amount of Glc-6-P dehydrogenase (Glc6PDH) and CS. The reaction was initiated by adding NADPH at 30°C. Aliquots of the mixture were removed and Cys formation was determined as described above. In the assay system, in which the content of SiR was increased to 2 nmol, oxidation of NADPH was directly measured spectrophotometrically as the decrease in A340. In this case, O-acetyl-l-Ser, Glc-6-P, Glc6PDH, and CS were omitted from the above assay mixture.

Complementation of E. coli Mutation

A Cys auxotrophic mutant of E. coli, strain JM246 [l-, cysI53(Am), IN(rrnD-rrnE)1] was provided by E. coli Genetic Stock Center (Yale University). This mutant has an amber mutation in cysI, the structural gene for SiR hemoprotein (Ostrowski et al., 1989b), and cannot grow on M9 medium unless 1 mm Cys or Met is supplemented in addition to the other 18 amino acids. DNAs corresponding to the mature regions of maize SiR (Ideguchi et al., 1995), Fd I (Matsumura et al., 1999), and Fd III (Hase et al., 1991b) were inserted under the control of the trc promoter of pTrc99A expression vector (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ), and the recombinant plasmids carrying SiR cDNA alone or both SiR cDNA and Fd I cDNA or Fd III cDNA were introduced into E. coli JM246. As a control, cysI (a gift from T. Mizuno, Nagoya University) was also used for the transformation. The transformed cells were streaked on a M9 plate with or without Cys in the presence of 1 mm isopropyl-β-d(−)-thiogalactopyranoside, and growth was examined after 4 to 7 d at 30°C.

RESULTS

Quantitative Analyses of SiR and Fd in Leaves and Roots of Maize Seedlings

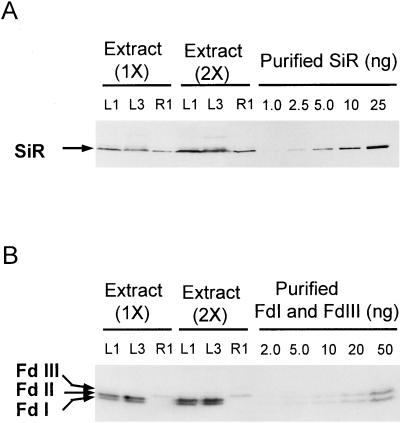

Total extracts from the primary leaf, the third leaf, and the root were separated by SDS-PAGE or non-denaturing PAGE, followed by western blotting (Fig. 1). Three major Fd isoproteins, Fd I, Fd II, and Fd III, were detected. Fd I and Fd II were restricted to leaves, while Fd III was mainly distributed in roots, in accordance with our previous report (Kimata and Hase, 1989). Fd I and Fd II are expressed specifically in mesophyll and bundle-sheath cells respectively (Matsumura et al., 1999). SiR was distributed in leaves and roots as a single band. Amounts of SiR, Fd I, and Fd III were determined based on the standard blot of each purified protein, which was quantitated as described in “Materials and Methods” (Fig. 1; Table I). On a protein basis, the content of SiR was higher in roots than in leaves, while that of Fd isoproteins was the opposite. Based on the reported subcellular volume of the chloroplast stroma (Winter et al., 1994), the stromal concentrations of SiR and Fd I were estimated to be about 1.2 and 37 μm, respectively (average values of the first and third leaves). The stromal concentration of Fd II seemed to be within the same range of that of Fd I. It was found that the molar ratio of Fd to SiR was considerably lower in roots (3:1) than in leaves (30:1).

Figure 1.

Quantitative analyses of SiR and Fd isoproteins in leaves and roots of maize seedlings. A, Total extracts of primary leaves (L1), roots (R1), and third leaves (L3) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and SiR was detected by western blotting using anti-SiR antibody. The amounts of sample applied to all lanes (1X) were equivalent to tissues of 2.5 mg fresh weight. B, The same extracts described in A were subjected to non-denaturing PAGE to separate Fd isoproteins, followed by western blotting using anti-Fd antibodies. The amounts of sample applied to lanes (1X) were equivalent to 1.7 mg of leaf tissues for L1 and L3 and 8.3 mg of root tissues for R1. Purified SiR (A) and Fd I and Fd III (B) were also applied as a standard for quantitative determination.

Table I.

Concentration of SiR and Fd isoproteins in maize leaves and roots

| Protein | Protein

Basis

|

Chloroplasta

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Leaves | 3rd Leaves | Roots | 1st Leaves | 3rd Leaves | |

| μg mg−1 protein | μm | ||||

| SiR | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 1.08 ± 0.16 | 1.4 | 0.95 |

| Fd I | 1.62 ± 0.08 | 1.58 ± 0.18 | NDb | 39.7 | 34.2 |

| Fd III | <0.016 | <0.013 | 0.41 ± 0.02 | <0.39 | <0.29 |

Chloroplast concentrations were calculated from a chloroplast stroma volume of 66 μL/mg chlorophyll (Winter et al., 1994). The chlorophyll a/b content was 62 and 70 μg/mg protein in the first leaves and third leaves, respectively.

ND, Not detected.

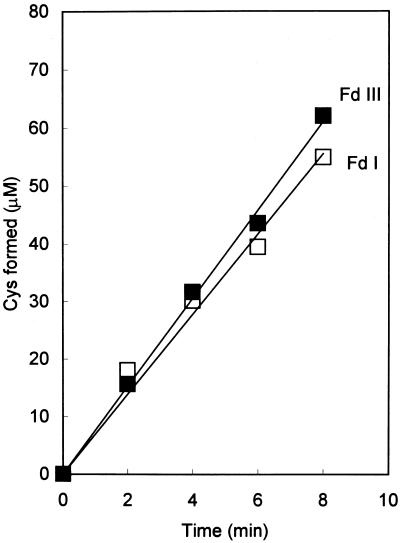

Electron Transfer Ability of Photoreduced Fd I and Fd III to SiR

SiR activity was assayed using either Fd I or Fd III as an electron donor. The assay mixture containing thylakoid membranes was illuminated with a saturated light intensity, and the reduction of sulfite to sulfide was measured by the formation of Cys. This assay system is considered to reflect the physiological sulfite reduction process occurring in chloroplasts. As shown in Figure 2, the reaction proceeded at a constant rate, and both Fds showed a similar electron transfer ability. When Fds were reduced by Na2S2O4, the ability of Fd I was slightly higher than that of Fd III (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Time course of photoreduction of sulfite. The reaction mixture contained Na2SO3, Fd I or Fd III, SiR, thylakoid membranes, and the other components for photoreduction of sulfite described in “Materials and Methods.” The reaction was initiated by illumination. Sulfide produced by SiR was converted to Cys by a coupling reaction with CS. The amount of Cys formed was measured by the acid ninhydrin reaction as described in “Materials and Methods.”

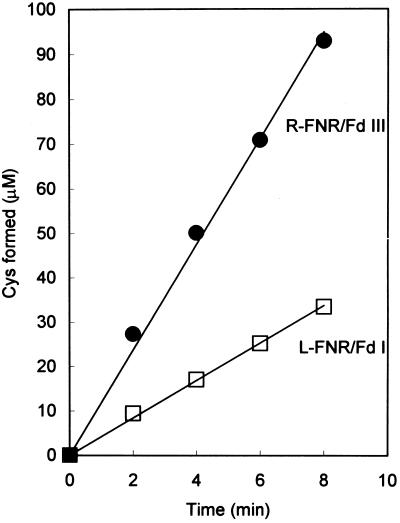

Reconstitution of a NADPH-Dependent Sulfite-Reduction System Using FNRs, Fds, and SiR

In root plastids, it has been proposed that a major function of Fd and FNR is to transfer electrons from NADPH to Fd-dependent enzymes. Using R-FNR and Fd III, or L-FNR and Fd I, NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction system was reconstituted. As shown in Figure 3, both combinations of FNR and Fd were able to support sulfite reduction. However, the comparative rate of the reaction in this non-photosynthetic system was significantly different from that in the photosynthetic system; R-FNR/Fd III showed about three times higher activity than L-FNR/Fd I.

Figure 3.

Time course of NADPH-dependent reduction of sulfite. The reaction mixture contained NADPH, Na2SO3, L-FNR or R-FNR, Fd I or Fd III, SiR, and the other components for NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction described in “Materials and Methods.” The reaction was initiated by the addition of NADPH. Sulfide formation was measured as indicated in the legend to Figure 2.

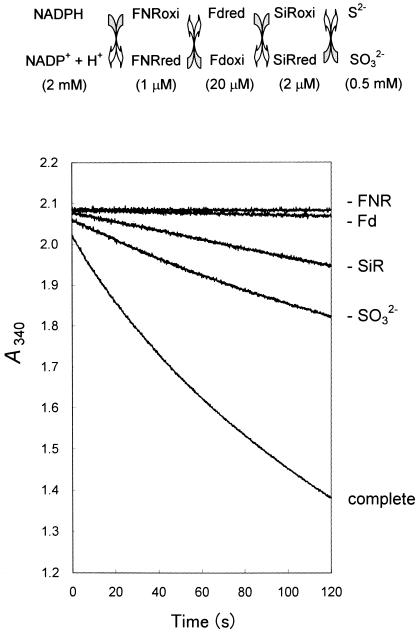

To investigate this NADPH/FNR/Fd/SiR electron transfer system in further detail, a spectrophotometric assay for NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction was used as shown in Figure 4. The data showed that all components, FNR, Fd, SiR, and sulfite, were required for a rapid oxidation of NADPH. Slow reactions observed with one of the components omitted seemed to reflect the NADPH oxidation uncoupled to sulfite reduction. This assay system enabled us to measure the electron transfer occurring when concentrations of several μm SiR and several 10 μm Fd were present. These ranges of concentrations were high enough to reflect the in situ quantitative relations of these proteins determined in this study (Fig. 1; Table I).

Figure 4.

Spectrometric assay of SiR activity in the NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction system. The complete reaction mixture contained FNR, Fd, SiR, and Na2SO3, and the other components for NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction described in “Materials and Methods.” The reaction was initiated by the addition of NADPH (2 mm) and the decrease of A340 was monitored in the cuvette with a light path of 2 mm. In four of the graph lines shown, one of the components in the reaction mixture (FNR, Fd, SiR, or Na2SO3) has been omitted. All assays were carried out under aerobic conditions in which part of reducing equivalent from NADPH was bypassed to O2. The difference in the decrease of A340 between the complete and −SO32− treatments was considered to be the net SiR activity.

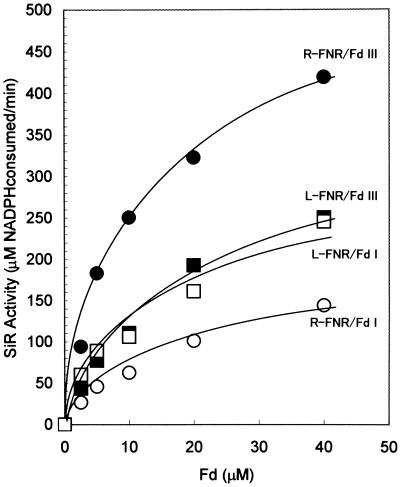

The R-FNR/Fd III pair was the most effective for supporting NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction among all combinations of FNRs and Fds tested (Fig. 5). When the SiR concentration was reduced to 100 nm, the combinations of R-FNR/Fd III and L-FNR/Fd III showed similar efficiency (data not shown). Electron transfer between each FNR and Fd III was not a limiting step in the sulfite reduction system with a low level of SiR. These combined results suggest that both R-FNR and Fd III contribute to an efficient sulfite reduction under physiological conditions. We presumed that the reduction potential of Fd isoproteins and protein-to-protein interaction between FNR and Fd were major determinants for the efficiency of the NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction, as discussed later.

Figure 5.

Comparison of SiR activity using different combinations of FNRs and Fds in the NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction system. The “complete” assay described Figure 4 was conducted using four combinations of FNRs and Fds: L-FNR/Fd I, L-FNR/Fd III, R-FNR/Fd I, and R-FNR/Fd III. The reaction was carried out at Fd concentrations of 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μm.

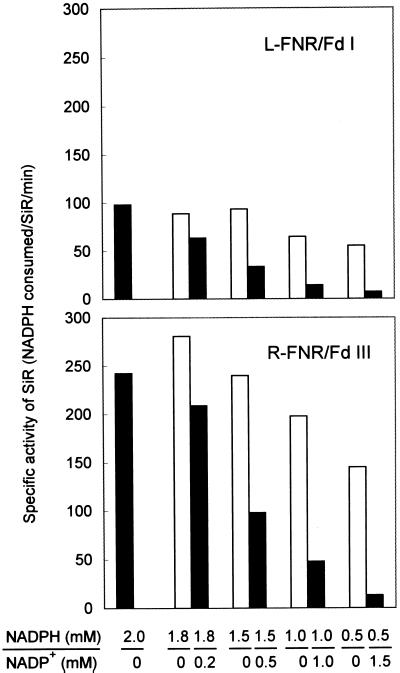

In the above assays we measured the initial velocity of sulfite reduction in the presence of only NADPH. The addition of NADP+ to the reaction mixture decreased the rate of sulfite reduction remarkably (Fig. 6). When the proportion of NADP+ in the reaction mixture was increased to 50%, sulfite reduction activity decreased to less than 20% of the initial level. A relatively high proportion of NADPH is thus necessary to drive efficient sulfite reduction.

Figure 6.

Effect of NADP+ on SiR activity in the NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction. The reaction of NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction was carried out at various ratios of NADPH/NADP+ (legend to x axis) to a total concentration of 2 mm (black bars). As a control, the reaction was carried out in the presence of only NADPH at the concentration of NADPH used for each ratio of NADPH/NADP+ tested (white bars).

Complementation of an E. coli SiR-Deficient Mutation with Maize SiR and Fd

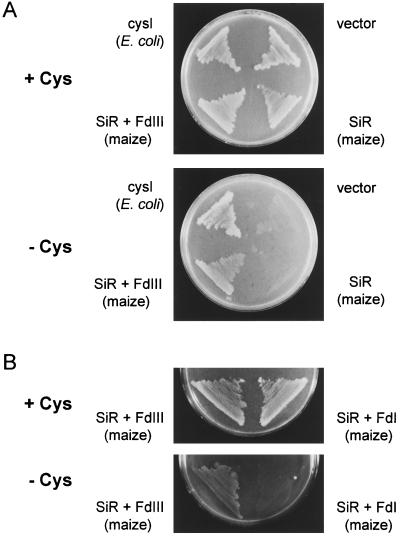

We examined maize SiR and Fd function in the sulfur assimilation pathway of E. coli, expecting that the different electron transfer abilities of Fd I and Fd III observed in our in vitro study could be confirmed in vivo. E. coli SiR is a hetero-oligomeric enzyme composed of flavoprotein and hemoprotein subunits, and utilizes NADPH directly as an electron donor (Siegel et al., 1973; Siegel and Davis, 1974). The hemoprotein is homologous to plant SiR. An E. coli SiR mutant having a defect in hemoprotein, JM246, showed a Cys-auxotroph phenotype. We introduced maize SiR cDNA alone into JM246 or co-introduced the cDNA with maize Fd III or Fd I cDNA, and tested recovery from Cys auxotrophy. As shown in Figure 7, only the cells co-transformed with maize SiR and Fd III cDNAs were able to grow on a minimal medium without Cys. This suggests that maize SiR itself cannot replace the bacterial SiR hemoprotein, and that maize SiR in combination with Fd III but not with Fd I is able to function as a sulfite-reducing system in bacterial cells.

Figure 7.

Growth of E. coil cysI− mutant transformed with maize SiR and Fd genes. A, A Cys auxotrophic E. coli JM246 lacking functional SiR was transformed with control vector (pTrc 99A) or the vector carrying the E. coil cysI gene, maize SiR cDNA, or maize SiR and Fd III cDNAs. Growth of the transformants was tested on a minimal agar plate with (+Cys) or without (−Cys) 1 mm Cys. B, E. coil JM246 was co-transformed with maize SiR and Fd I cDNAs, or maize SiR and Fd III cDNAs, and Cys auxotrophy was tested as above.

DISCUSSION

We initiated this study to investigate the reductant supply system for Fd-dependent SiR in non-photosynthetic organs in maize. SiR seems to be distributed in both leaves and roots as a single molecular species. Fd is encoded by a small gene family, and Fd I and Fd III are the major isoproteins localized in leaves and roots, respectively. By quantitative western-blot analysis, concentrations of SiR and Fd I in the chloroplast stroma were estimated to be 1.2 and 37 μm, respectively, based on the stromal volume per unit of Chl reported by Winter et al. (1994). Although the concentrations of SiR and Fd III in root plastids could not be determined in the present study, their contents on a total protein basis (Table I) indicate that the ratio of Fd to SiR (3:1) in root plastids is 10 times lower than that in chloroplasts. These observations indicate that the quantitative relations of electron carrier (Fd) and enzyme (SiR) for in vivo sulfite reduction, especially in root plastids, is quite distinct from that for in vitro assay of SiR, where the electron carrier is generally present in excess of the enzyme. The amount of Fd, and therefore electron donation to SiR, may be a limiting factor for in vivo sulfite reduction.

With these concerns in mind, we reconstituted sulfite reduction systems with purified recombinant SiR, Fd I, and Fd III. Because, together with Fd, FNR has been proposed to serve as a system for electron donations from NADPH to two other Fd-dependent enzymes (NiR and GOGAT) in root plastids (Oji et al., 1985; Bowsher et al., 1989, 1992), we also used recombinant maize L-FNR and R-FNR in the reconstitution system. An in vitro system for nitrite reduction has been reported using Fd, FNR, and NiR from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Jin et al., 1998).

The redox potentials of Fd I and Fd III are −423 mV and −345 mV respectively (Akashi et al., 1997). Photoreduced or chemically reduced Fd I and Fd III support sulfite reduction by SiR in a similar manner, indicating that there is no significant difference between the abilities of the two Fds for transferring electron to SiR, when they are fully reduced by strong reducing systems (Fig. 2). On the other hand, Fd III is superior to Fd I in the NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction system (Fig. 3). This phenomenon can be explained thermodynamically. The redox potential of NADPH/NADP+ is −320 mV, and the reduction of Fd III from NADPH is more favorable than that of Fd I. Although both L- and R-FNRs catalyze reduction of Fd from NADPH, R-FNR becomes superior to L-FNR in sulfite reduction when SiR is present at 2 μm, a concentration high enough to reflect physiological conditions (Fig. 5).

The amount of FNR does not seem to be a limiting factor, because the molecular activity of FNR (about 400 electrons s-1) is much higher than that of SiR (about 8 electrons s-1), and because the superiority of R-FNR to L-FNR was found at a wide range of FNR concentrations ranging from the submicromolar to several micromolar (data not shown). Fd and Fd-dependent enzymes are known to form an electrostatically stable 1:1 complex (Knaff and Hirasawa, 1991). We have found that Fd has electrostatic interaction sites both common and unique to each FNR and SiR (Akashi et al., 1999). This suggests that the electron transfer from NADPH to SiR via FNR and Fd should be understood as a matter of protein-to-protein recognition, especially when Fd is not present in large excess of SiR and FNR, as is the case in root plastids. More information is necessary to explain the superiority of the combination of R-FNR and Fd III on a physicochemical basis, in addition to the redox potential of the two Fds. We have recently found that the affinity of R-FNR to Fd III is 10-fold higher than that to Fd I (Y. Onda and T. Hase, unpublished data).

NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction is strongly influenced by the ratio of NADPH/NADP+, irrespective of the combinations of R-FNR/Fd III and L-FNR/Fd I (Fig. 6). This is due to the necessity for relatively high proportions of NADPH to drive Fd reduction by FNR. A similar phenomenon was reported in NADPH-dependent nitrite reduction (Jin et al., 1998). In non-photosynthetic plastids, it has been proposed that NADPH is supplied mainly from the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. However, the first enzyme of this pathway, Glc6PDH, is redox regulated, and high ratios of NADPH/NADP+ strongly inhibit the activity of Glc6PDH, especially from chloroplasts (Scheibe et al., 1989). Therefore, there is a conflict between a need for the maintenance of high NADPH/NADP+ ratios for efficient Fd reduction by FNR, and its inhibition of Glc6PDH. In vivo and in vitro studies of Glc6PDH from barley root plastids has revealed that this enzyme is only 50% inhibited at a physiological NADPH/NADP+ ratio (1.5) (Wright et al., 1997). If this redox state also existed in maize root plastids, 30% to 40% of the maximum activity of sulfite reduction would remain (Fig. 6).

A SiR-deficient E. coli mutant was complemented only when the maize SiR gene was co-transformed with a Fd III gene. Fd I did not seem to function as an efficient electron donor for SiR in the bacterial cells. These observations are in good accordance with the results obtained in in vitro NADPH-dependent sulfite reduction studies. It has been reported that when a plant acyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase, which is a Fd-dependent enzyme, is expressed in E. coli cells with leaf-type Fd from Arabidopsis, the level of desaturation of the corresponding fatty acids becomes higher compared with that in cells expressing the desaturase alone (Cahoon et al., 1996). If, as in our studies, root-type Fd had been used, larger changes in lipid desaturation might have been observed. E. coli has its own Fd, which has a [2Fe-2S] cluster and belongs to a different family than the plant-type Fd (Knoell and Knappe, 1974; Ta and Vickery, 1992). E. coli Fd is probably unable to function as an efficient redox partner for these plant Fd-dependent enzymes. At present, we do not know what kind of reduction system is operating for plant Fd in E. coli cells. An FNR-like flavoenzyme has been identified in E. coli (Bianchi et al., 1993), and E. coli SiR flavoprotein has an FNR-like domain in its carboxy-terminal region (Ostrowski et al., 1989a; Eschenbrenner et al., 1995). It is possible that such flavoproteins may support the reduction of plant Fd.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. S. Chandler for his critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Research on Priority Areas (nos. 09274101 and 09274103 to T.H.) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

LITERATURE CITED

- Akashi T, Matsumura T, Ideguchi T, Iwakiri K, Kawakatsu T, Taniguchi I, Hase T. Comparison of the electrostatic binding sites on the surface of ferredoxin for two ferredoxin-dependent enzymes, ferredoxin-NADP+reductase and sulfite reductase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29399–29405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akashi T, Matsumura T, Taniguchi I, Hase T. Mutational analysis of the redox properties of the [2Fe-2S] cluster in plant ferredoxins. J Inorg Biochem. 1997;67:255. [Google Scholar]

- Aketagawa J, Tamura G. Ferredoxin-sulfite reductase from spinach. Agric Biol Chem. 1980;44:2371–2378. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Chamarro J, Granell A. A non-photosynthetic ferredoxin gene is induced by ethylene in Citrusorgans. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;29:1211–1221. doi: 10.1007/BF00020463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki H, Tanaka K, Ida S. The genomic organization of the gene encoding a nitrate-inducible ferredoxin-NADP+oxidoreductase from rice roots. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1229:389–392. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(95)00032-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arb CV, Brunold C. Measurement of ferredoxin-depedent sulfite reductase activity in crude extracts from leaves using O-acetyl-L-serine sulfhydrylase in a coupled assay system to measure the sulfide formed. Anal Biochem. 1983;131:198–204. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon DI, Hoagland DR. Crop production in artificial solutions and soils with special reference to factors influencing yield and absorption of inorganic nutrients. Soil Sci. 1940;50:463–471. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi V, Reichard P, Eliasson R, Pontis E, Krook M, Jornvall H, Haggard-Ljungquist E. Escherichia coli ferredoxin NADP+ reductase: activation of E. coli anaerobic ribonucleotide reduction, cloning of the gene (fpr), and overexpression of the protein. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1590–1595. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1590-1595.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bick JA, Åslund F, Chen Y, Leustek T. Glutaredoxin function for carboxyl-terminal domain of the plant-type 5′-adenylylsulfate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8404–8409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork C, Schwenn DJ, Hell R. Isolation and characterization of a gene for assimilatory sulfite reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene. 1998;212:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowsher CG, Boulton EL, Rose J, Nayagam S, Emes MJ. Reductant for glutamate synthase is generated by the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway in non-photosynthetic root plastids. Plant J. 1992;2:893–898. [Google Scholar]

- Bowsher CG, Hucklesby DP, Emes MJ. Nitrite reduction and carbohydrate metabolism in plastids purified from roots of Pisum sativumL. Planta. 1989;177:359–366. doi: 10.1007/BF00403594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunold C, Suter M. Localization of enzymes of assimilatory sulfate reduction in pea roots. Planta. 1989;179:228–234. doi: 10.1007/BF00393693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon EB, Mills LA, Shanklin J. Modification of the fatty acid composition of Escherichia coliby coexpression of a plant acyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase and ferredoxin. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:936–939. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.936-939.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbrenner M, Coves J, Fontecave M. NADPH-sulfite reductase flavoprotein from Escherichia coli: contribution to flavin content and subunit interaction. FEBS Lett. 1995;374:82–84. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01081-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farago S, Brunold C. Regulation of assimilatory sulfate reduction by herbicide safeners in Zea maysL. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:1808–1812. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.4.1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LS, Yee BC, Buchanan BB, Kamide K, Sanada Y, Wada K. Ferredoxin and ferredoxin-NADP reductase from photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic tissues of tomato. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:1207–1213. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.4.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Marcos FJ, Roberts AM, Campbell IE, Wray LJ. Three members of a novel small gene family from Arabidopsis thaliana able to complement functionally an Escherichia colimutant defective in PAPS reductase activity encode proteins with a thioredoxin-like domain and “APS reductase” activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13377–13382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase T, Kimata Y, Yonekura K, Matsumura T, Sakakibara H. Molecular cloning and differential expression of the maize ferredoxin gene family. Plant Physiol. 1991a;96:77–83. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase T, Mizutani S, Mukohata Y. Expression of maize ferredoxin cDNA in Escherichia coli. Plant Physiol. 1991b;97:1395–1401. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.4.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ideguchi T, Akashi T, Onda Y, Hase T. cDNA cloning and functional expression of ferredoxin-dependent sulfite reductase from maize in E. colicells. In: Mathis P, editor. Photosynthesis: From Light to Biosphere. II. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 713–716. [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Huppe HC, Turpin DH. In vitro reconstitution of electron transport from glucose-6-phosphate and NADPH to nitrite. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:303–309. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.1.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Hase T. Localization of ferredoxin isoproteins in mesophyll and bundle sheath cells in maize leaf. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:1193–1197. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaff DB, Hirasawa M. Ferredoxin-dependent chloroplast enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1056:93–125. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoell HE, Knappe J. Escherichia coliferredoxin, an iron-sulfur protein of the adrenodoxin type. Eur J Biochem. 1974;50:245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RJ, Siegel LM. Spinach siroheme enzymes: isolation and characterization of ferredoxin-sulfite reductase and comparison of properties with ferredoxin-nitrite reductase. Biochemistry. 1982;21:2892–2904. doi: 10.1021/bi00541a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leustek T, Saito K. Sulfite transport and assimilation in plants. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:637–643. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura T, Kimata-Ariga Y, Sakakibara H, Sugiyama T, Murata H, Takano T, Shimonishi Y, Hase T. Complementary DNA cloning and characterization of ferredoxin localized in bundle-sheath cells of maize leaves. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:481–488. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura T, Sakakibara H, Nakano R, Kimata Y, Sugiyama T, Hase T. A nitrate-inducible ferredoxin in maize roots. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:653–660. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.2.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oji Y, Watanabe M, Wakiuchi N, Okamoto S. Nitrite reduction in barley-root plastids: dependence on NADPH coupled with glucose-6-phosphate and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, and possible involvement of an electron carrier and a diaphorase. Planta. 1985;165:85–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00392215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski J, Barber MJ, Rueger DC, Miller BE, Siegel LM, Kredich NM. Characterization of the flavoprotein moieties of NADPH-sulfite reductase from Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989a;264:15796–15808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski J, Wu J-Y, Rueger DC, Miller BE, Siegel LM, Kredich NM. Characterization of the cysJIH regions of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coliB. J Biol Chem. 1989b;264:15726–15737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie SW, Redinbaugh MG, Shiraishi N, Vrba JM, Campbell WH. Identification of a maize root transcript expressed in the primary response to nitrate: characterization of a cDNA with homology to ferredoxin-NADP+oxidoreductase. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;26:679–690. doi: 10.1007/BF00013753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüegsegger A, Brunold C. Effect of cadmium on γ-glutamylcysteine synthesis in maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:428–433. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.2.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K. Biosynthesis of cysteine. In: Singh BK, editor. Plant Amino Acids. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1999. pp. 267–292. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe R, Geissler A, Fickenscher K. Chloroplast glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase: Kmshift upon light modulation and reduction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;274:290–297. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setya A, Murillo M, Leustek T. Sulfate reduction in higher plants: molecular evidence for a novel 5′-adenylsulfate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13383–13388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel LM, Davis PS. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-sulfite reductase of enterobacteria. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:1587–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel LM, Murphy ML, Kamin H. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-sulfite reductase of enterobacteria. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:251–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ta DT, Vickery LE. Cloning, sequencing, and overexpression of a [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin gene from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11120–11125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K, Onda M, Matsubara H. Ferredoxin isolated from plant non-photosynthetic tissues: purification and characterization. Plant Cell Physiol. 1986;27:407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Robinson DG, Heldt HW. Subcellular volumes and metabolite concentrations in spinach leaves. Planta. 1994;193:530–535. [Google Scholar]

- Wright DP, Huppe HC, Turpin DH. In vivo and in vitro studies of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from barley root plastids in relation to reductant supply for NO2−assimilation. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:1413–1419. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.4.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Ashikari T, Tanaka Y, Kusumi T, Hase T. Molecular characterization of tobacco sulfite reductase: enzyme purification, gene cloning, and gene expression analysis. J Biochem. 1998;124:615–621. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]