Abstract

Many studies have been now focused on the promising approach of fungal endophytes to protect the plant from nutrient deficiency and environmental stresses along with better development and productivity. Quantitative and qualitative protein characteristics are regulated at genomic, transcriptomic, and posttranscriptional levels. Here, we used integrated in-depth proteome analyses to characterize the relationship between endophyte Piriformospora indica and Brassica napus plant highlighting its potential involvement in symbiosis and overall growth and development of the plant. An LC-MS/MS based label-free quantitative technique was used to evaluate the differential proteomics under P. indica treatment vs. control plants. In this study, 8,123 proteins were assessed, of which 46 showed significant abundance (34 downregulated and 12 upregulated) under high confidence conditions (p-value ≤ 0.05, fold change ≥2, confidence level 95%). Mapping of identified differentially expressed proteins with bioinformatics tools such as GO and KEGG pathway analysis showed significant enrichment of gene sets involves in metabolic processes, symbiotic signaling, stress/defense responses, energy production, nutrient acquisition, biosynthesis of essential metabolites. These proteins are responsible for root’s architectural modification, cell remodeling, and cellular homeostasis during the symbiotic growth phase of plant’s life. We tried to enhance our knowledge that how the biological pathways modulate during symbiosis?

Introduction

The vegetable oil production has been crossed approximately 87 million metric tons every year. The worldwide consumption level of vegetable oils, since last decade, enhanced almost 50% with the doubled price1,2. The Rapeseed/canola (Brassica napus) occupied second place (13.6%) in global oilseed production and third place in the global vegetable oil consumption. The annual planting acreage is about 8 MH (million hectares) in China, which accounts for a quarter of the world’s total B. napus production3,4.

Increasing the high yield capacity of B. napus is the big challenge in current agriculture research3. The yield is restricted by various environmental factors like an intensification of land use, irrigation thorough metal/pesticide-contaminated water, water deficit, high temperature, drought, salinity and fungal pathogens3,4. Keeping in mind the environmental aspects, root endophytes and mycorrhiza seems to be a promising approach to cope up with this problem without affecting the soil environment. Subsequently, endophytes help in improving the plant health, growth, development and productivity. These endophytes receive essential organic carbon forms from the host for survival. In return, they secrete some enzymes, which help in solubilizing some complex soil nutrients to available forms for plant uptake. Thus, fungus supports enhanced water and nutrient uptake, protect from various biotic, abiotic stresses and plant pathogens for better growth of the host plant5–8.

Piriformosopra indica, a mycorrhiza like phyto-promotional root endosymbiont, was isolated from woody shrubs Prosopisjuliflora (Swartz) DC. and Zizyphusnummularia (Burm. fil.) Wt. &Arn.in Thar desert of Indian province Rajasthan9. An extensive research has been conducted on this fungus since last two decades. P. indica confers enhanced vegetative growth, stress tolerance, resistance to plant pathogens in wide host range from monocot to dicot plant species without host specificity. The fungus grows inside the root cortex of host plants without invading the endodermis and aerial parts of the plants6–8,10,11. Previously our group has studied the interaction between P. indica and B. napus, resulted in significant enhancement of agronomic parameters, biomass and nutrient elements contents. Quality parameters of oilseed quality like oils content and other acid contents were also found increased significantly12.

Previously in past few years, limited researchers worked on symbiosis at the molecular level, especially at the protein part. Song et al.13 investigated the proteomes of Glomus mosseae and Amorphafruticosa interaction. Expressed proteins found extensively involved in several biological and cellular processes14. Focusing on plant–microbe interactions, Vannini et al.15 analyzed the proteomic profile and investigated the complex inter-domain network during the interaction of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (AMF) Gigaspora margarita with Lotus japonicas15. Proteomes of two wheat cultivars interacted with G. mosseae indicated 55 and 66 DEPs in both, resulting in modulation of proteins related to metabolism14. In another study, leaf proteomics of P. indica colonized barley plant under salt and water stress stated that P. indica induces a systemic response by altering physiological and metabolic capacity in colonized plants improving tolerance to stresses16,17.

The aim of this study was to analyze the protein expression pattern during symbiotic association of fungal root endophyte and host plant. This study supports the idea that proteomics may be closer to phenotype and may incorporate the new insights into plant-microbe interaction explaining ‘how fungal partner provide direct/indirect benefits to the host plant’. Here, we applied label-free quantitative proteomics to investigate the differences in the protein expression between P. indica colonized and control plants.

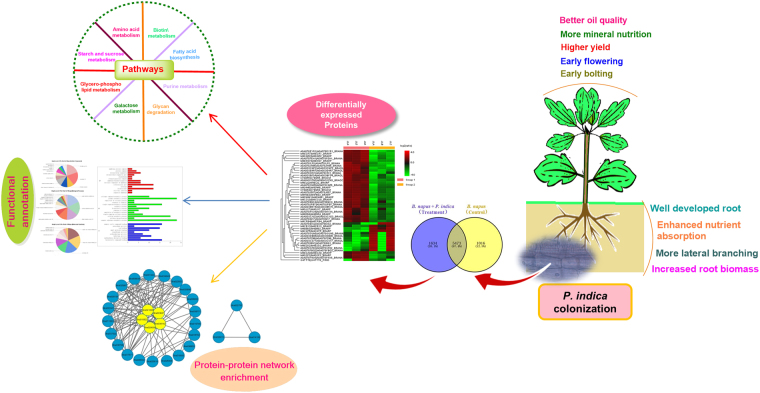

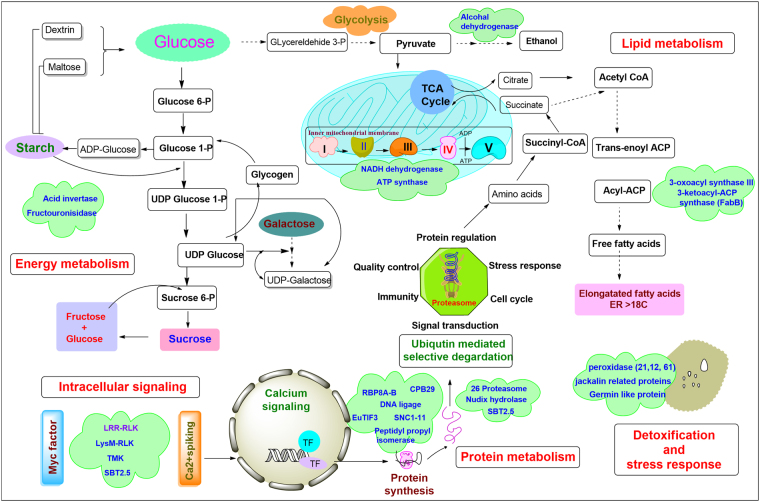

The results of the quantitative proteomics suggested that P. indica significantly accumulated various metabolic proteins potentially involved in metabolic pathways which lead to growth promotion and better crop productivity. We also proposed the model for early symbiotic signaling mechanism of P. indica colonized rapeseed plant at the early symbiotic stage. The physiological and biochemical proteome network illustrated in our study supports the complex proteomic status of plant-fungal interaction. This study also provides the comprehensive insight which will help in the future study that ‘how fungus modulates the cellular metabolic physiology at proteome level’ resulted in ecological benefits to the host plant. Figure 1 depicts the overall schematic approach performed in symbiotic interaction to understand the molecular physiology of symbiosis.

Figure 1.

Schematic experimental approach resulted during symbiotic interaction of P. indica and B. napus.

Results

Root colonization and microscopic analysis

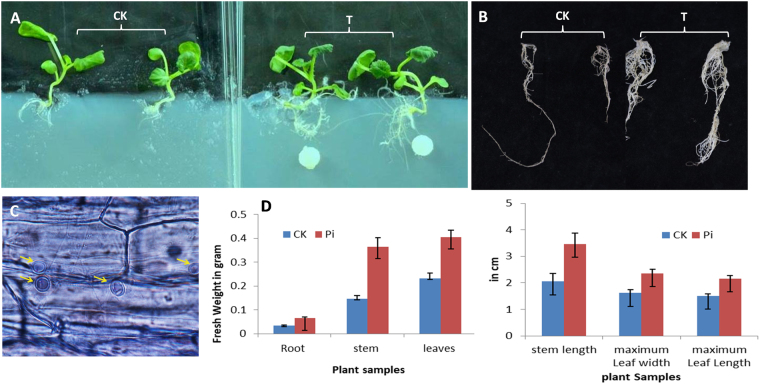

During the co-culture with P. indica, mycelium plugs were introduced 1 cm apart from four-leaved rapeseed plantlets. There was no physical contact with each other during the initial 2–3 days period. Vahabi et al.7 suggested, during this stage of co-cultivation, both communicate via the gaseous phase of exudate soluble compounds. After 5–6 days of the experiment, fungal mycelium and growing roots were approached to each other and penetrates into the epidermal layer of root and subsequently, sporulation started inside the root cortex and symbiosis established between both the partners. On 28th-day post inoculation, branched roots, more lateral rootlets with numerous root hairs were well developed in P. indica treated B. napus (Fig. 2A,B). The P. indica treated host rapeseed was uniformly healthy as compared to non-mycorrhizal rapeseed. At this time, the significant difference was observed in fresh weight of the root, shoot and, leaves. The length of root, shoot and leaves and leaves width were also found significantly higher in treated as compared to control plants. The microscopic study revealed the promotion of hyphal network inside the root system and penetrating the epidermal and cortical tissue12 (Fig. 2C). Dark colored pear shaped chlamydospores scattered around these tissues. At the later stage, these chlamydospores germinate and form the mycelium inside and finally localized as inter and intra mycelium into the host plant root.

Figure 2.

(A,B) Four weeks old B. napus seedling and roots, (C) Microscopic image of root cross section showing the chlamydospores inside the root cortex, (D) Agronomic parameters of treated and control B. napus root and shoot samples after 28 days of P. indica treatment. The values are the means ± SD (CK: Control; T: Treatment).

Quantitative proteomics of B. napus and P. indica interaction

The roots of rapeseed plant colonized with P. indica changed the protein profiles during the mutualistic symbiotic interaction. To assess the proteome coverage on the basis of physiological and growth parameters, we have selected 28 days old plants for the quantitative analysis. From pooled mixture of all control and P. indica treated root samples (in triplicate) by using LC-MS/MS method, a total of 109,003 MS/MS denovo spectra (avg. ~18,167) and a total 21,688 MS/MS peptide-Spectrum matches (avg. ~3,615) were identified and searched against the PEAKS studio 8, which corresponds to a total of 8,123 proteins at 95% confidence level. (Table 1 & Supplementary Table S1). Among, 8,123 total identified proteins, 8,067 proteins were from Brassica species and 56 proteins belong to P. indica, expressed inside the B. napus root.

Table 1.

Statistical overview of proteome obtained after filtration of control (C) and treated (T) samples (in triplicates).

| Sample Name | C1 | C2 | C3 | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide-Spectrum Matches | 2864 | 2621 | 6148 | 2413 | 4276 | 3366 |

| Peptide sequences | 2307 | 1944 | 4102 | 1911 | 2919 | 2342 |

| Protein groups | 1016 | 931 | 1514 | 892 | 1229 | 1019 |

| Proteins | 2263 | 1865 | 3152 | 1856 | 2561 | 2306 |

| Proteins (#Unique Peptides) | 204 (>2); 341 (=2); 789 (=1); | 113 (>2); 175 (=2); 652 (=1); | 320 (>2); 497 (=2); 979 (=1); | 119 (>2); 229 (=2); 621 (=1); | 177 (>2); 357 (=2); 812 (=1); | 201 (>2); 372 (=2); 759 (=1); |

| FDR (Peptide-Spectrum Matches) | 8.60% | 10.30% | 3.10% | 6.10% | 5.60% | 4.70% |

| FDR (Peptide Sequences) | 10.50% | 13.60% | 4.40% | 7.50% | 8.20% | 6.40% |

| FDR (Protein) | 3.40% | 4.30% | 4.50% | 4.00% | 4.70% | 2.30% |

| De Novo Only Spectra | 16583 | 22854 | 17335 | 15753 | 21321 | 15157 |

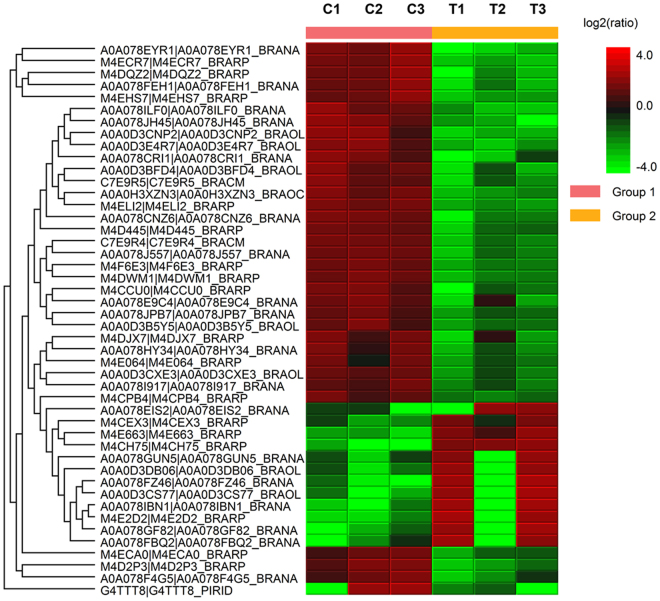

We performed the pair-wise comparison of all samples of control and treatments in triplicate to explore the similarities and differences in the symbiotic root proteome of B. napus plants. By using label-free quantification with following the parameters such as 95% confidence level (p-value ≤ 0.05), fold change ≥2, at least one unique peptide as a cut offs with significant method ANOVA, we identified fungal and plant proteins which are differentially expressed after efficient colonization of P. indica in rapeseed plant’s root. As a result, we found 46 proteins are differentially expressed in untreated control and treated plant roots (Table 2, Supplementary Table S2, and File S1). Among 46 proteins, 45 were plant proteins and 01 was fungal protein - P. indica (expressed inside the host plant root). Of these, 12 proteins were upregulated and 34 proteins were downregulated. Hierarchical clustering showing differentially expressed proteins in two groups of each treatment indicates that root colonization by P. indica induced large changes in protein levels (Fig. 3). To improve the identification of unknown proteins obtained in our result, we performed BLAST analysis against the Brassica species using NCBI database.

Table 2.

Properties of differentially expressed proteins.

| UniProt accession | Protein name and species | Significance (−10lgP*) | Sequence Coverage (%) | Peptide | Unique Peptide | Fold change (ratio of T/C)** | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M4ELI2 | Uncharacterized protein (Brassica rapa) | 35.08 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 0.27 | Down |

| M4CH75 | Uncharacterized protein (B. rapa) | 33.24 | 37 | 14 | 2 | 13.39 | Up |

| M4F6E3 | Acid beta-fructofuranosidase 3, vacuolar-like (B. rapa) | 28.38 | 28 | 13 | 8 | 0.34 | Down |

| M4DWM1 | Reticuline oxidase-like protein (B. rapa) | 26.63 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 0.31 | Down |

| A0A0H3XZN3 | ATP synthase subunit alpha, chloroplastic OS (Brassica oleracea) | 21.78 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 0.27 | Down |

| M4D2P3 | Niemann-Pick C1 protein (B. napus) | 20.18 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.28 | Down |

| A0A078CNZ6 | Alpha-mannosidase OS (B. napus) | 19.8 | 36 | 29 | 1 | 0.27 | Down |

| C7E9R4 | Peroxidase 12(Fragment) OS (B. rapa) | 19.8 | 22 | 6 | 6 | 0.33 | Down |

| A0A0D3DB06 | Pro-resilin-like (B. oleracea) | 18.85 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 2.66 | Up |

| A0A078FEH1 | Germin-like protein subfamily 2 member 4 (B. napus) | 18.53 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 0.21 | Down |

| M4DQZ2 | LRR receptor-like protein kinase At1g51890 (B. rapa) | 18.47 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.17 | Down |

| G4TTT8 | Related to cysteine synthase (P. indica) | 18.15 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.29 | Down |

| A0A078JPB7 | Alpha-amylase/subtilisin inhibitor-like (B. napus) | 18.02 | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0.47 | Down |

| M4ECR7 | Basic blue protein (B. napus) | 17.73 | 39 | 3 | 3 | 0.16 | Down |

| A0A078EYR1 | Adenylosuccinatesynthetase (B. napus) | 17.4 | 18 | 6 | 2 | 0.1 | Down |

| A0A078I917 | RNA-binding protein 8A-B-like (B. napus) | 17.17 | 37 | 6 | 3 | 0.5 | Down |

| A0A078J557 | Epidermis-specific secreted glycoprotein EP1-like (B. napus) | 17.13 | 26 | 12 | 1 | 0.34 | Down |

| A0A0D3CXE3 | MLP-like protein 34 (B. oleracea) | 17.03 | 61 | 11 | 3 | 0.45 | Down |

| A0A0D3BFD4 | Alcohol dehydrogenase (Fragment) OS (B. oleracea) | 16.96 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0.26 | Down |

| A0A078GUN5 | Translationally-controlled tumor protein homolog (B. napus) | 16.87 | 39 | 7 | 1 | 3.16 | Up |

| A0A0D3E4R7 | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase III (FabB), chloroplastic-like (B. oleracea) | 16.19 | 15 | 4 | 4 | 0.2 | Down |

| M4CCU0 | LysM domain-containing GPI-anchored protein 2-like (B. rapa) | 16.04 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 0.38 | Down |

| M4ECA0 | Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase GDPDL3 (B. rapa) | 15.83 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 0.46 | Down |

| C7E9R5 | Peroxidase 21 isofrom X2 (Fragment) (B. napus) | 15.76 | 18 | 3 | 3 | 0.31 | Down |

| A0A078GF82 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase (B. napus) | 15.74 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 4.63 | Up |

| M4E2D2 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 13-B-like (B. rapa) | 15.73 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 7.35 | Up |

| M4EHS7 | Receptor-like kinase TMK4 (B. rapa) | 15.54 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0.21 | Down |

| A0A078CRI1 | Nudix hydrolase 3-like (B. napus) | 15.42 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0.2 | Down |

| A0A078ILF0 | N-acetyl-gamma-glutamyl-phosphate reductase (B. napus) | 15.16 | 23 | 7 | 7 | 0.18 | Down |

| M4CPB4 | 3-hydroxyacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] dehydratase FabZ-like (B. rapa) | 15.05 | 27 | 6 | 5 | 0.48 | Down |

| A0A078JH45 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit F OS (B. napus) | 15.03 | 25 | 6 | 2 | 0.15 | Down |

| A0A0D3B5Y5 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit F (B. oleracea) | 14.98 | 32 | 7 | 3 | 0.41 | Down |

| A0A078HY34 | Suppressor protein STM1-like (B. napus) | 14.92 | 16 | 3 | 3 | 0.37 | Down |

| M4D445 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase (B. rapa) | 14.9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.38 | Down |

| A0A078EIS2 | Uncharacterized protein OS (B. napus) | 14.55 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2.28 | Up |

| A0A078FZ46 | Subtilisin-like protease SBT2.5 (B. napus) | 14.27 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6.46 | Up |

| M4E064 | Jacalin-related lectin 35 (B. rapa) | 14.26 | 34 | 8 | 6 | 0.49 | Down |

| A0A078F4G5 | Pectin acetylesterase 5-like (B. napus) | 14.15 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0.37 | Down |

| M4E663 | Peroxidase 69 (B. rapa) | 14.1 | 25 | 8 | 4 | 5.34 | Up |

| A0A078IBN1 | RNA-binding protein CP29B, chloroplastic-like (B. napus) | 13.92 | 21 | 5 | 1 | 6.26 | Up |

| A0A0D3CS77 | 26 S protease regulatory subunit 7 homolog A-like (B. oleracea) | 13.83 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5.13 | Up |

| A0A0D3CNP2 | Aminoacylase-1 (B. oleracea) | 13.83 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 0.15 | Down |

| A0A078FBQ2 | Protein modifier of SNC1 11-like (B. napus) | 13.65 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 3.13 | Up |

| M4CEX3 | DNA ligase (B. rapa) | 13.54 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.35 | Up |

| A0A078E9C4 | Monocopper oxidase-like protein SKU5 (B. napus) | 13.38 | 21 | 10 | 1 | 0.35 | Down |

| M4DJX7 | Aspartic proteinase A1-like = GN (B. oleracea) | 13.13 | 34 | 14 | 1 | 0.36 | Down |

*Low scoring peptide identifications are filtered out by setting −10lgP threshold >13 (Peak studio 8.0). **Proteins which contains the T/C (Treated/Control) ratio ≥2.28 and ≤0.5 were considered as significant.

Figure 3.

The heatmap showing the expression profiles and hierarchical clustering of 46 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in P. indica colonized B. napus plants. (C-control group and T-treated with P. indica) (Experiment performed in triplicates).

Functional classification of differentially expressed protein

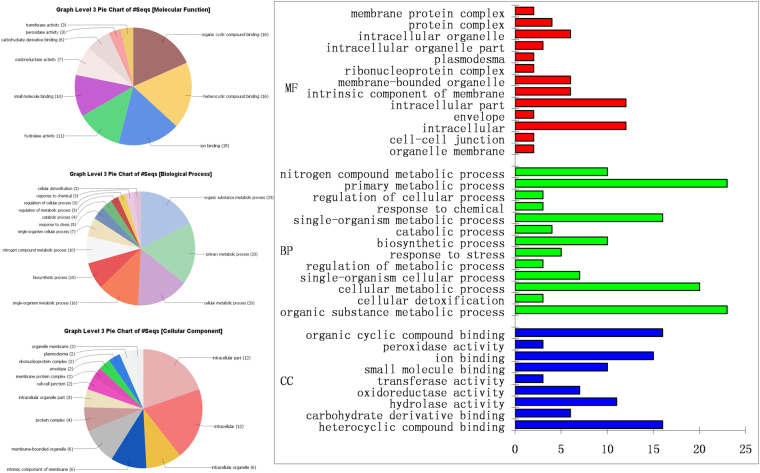

In order to obtain a Gene Ontology (GO) classification for the identified differentially expressed proteins of B. napus plant, a GO tool blast2GO was used. The 46 proteins from P. indica colonized B. napus root are attributed to their biological process and found that 17.70% (23) proteins engaged in the primary metabolic process and 15.38% (20) involved in cellular metabolic processes. The major proportions of 17.70% (23) proteins were found to be involved in various organic substances metabolism which are essential components of biosynthesis, degradation, and energy-related reactions. 7.69% (10) proteins are involved in the biosynthetic process and the same number of proteins is also engaged in nitrogenous compound metabolism. Remaining proteins are related to various other biological regulation processes as cellular detoxification, stress responses, and regulation of catabolic, metabolic and cellular activities. Among the 46 differentially expressed proteins 29.27% (12) proteins were proposed to be located in the cytoplasm and another 17.03% (7) belonged to cytoplasmic part. However, 14.63% (6) proteins were the part of an integral component of the membrane and the same percentage was present in intracellular membrane-bound organelle. Mitochondrial proteins including membrane occupied 9.76% (4) of total identified proteins. The root proteomes of rapeseed showed overrepresented molecular functions in activities of binding like organic compound, nucleic acid, cation-anion binding, nucleotide and nucleoside binding, hydrolase, oxidoreductase activity, peptidase activity. The majority of proposed proteins under molecular function category included phosphate binding (10), nucleotide binding (10), ionic binding (16), oxidation-reduction reactions (3) and various catalytic activities (3). Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S3 represented the identified root proteins modulated by P. indica cover a wide range of cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes. These biological pathways are also mapped in KEGG and were annotated in 10 KEGG pathways (Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 4.

Gene ontology enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins accumulated in P. indica inhabited B. napus root.

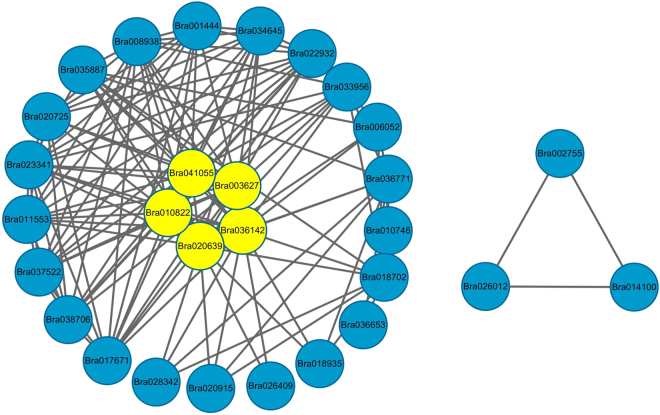

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis of AM fungus treated rapeseed plant

To explore the PPI information in the context of symbiosis responsive proteins, we analyzed the functional overview of 46 DEPs using Cytoscape v2.8.3 software. The Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S4 depict the densely connected network, in which 16 out of 46 identified proteins were mapped to the B. napus protein-interactome database. The proteins which were highlighted in the network with the most connect degree were considered as drive proteins and these proteins centrally involve in energy metabolism that participate in activating, suppressing, regulating or catalyzing the cellular processes within the cell (Fig. 5). In the network, we speculated that the yellow subunits forms the interactome cluster with the other proteins and potentially drives the energy metabolic process in host plant. Another triangle interaction network is related to DNA/protein binding proteins and participates in protein regulation. The findings were consistent with our GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 5.

Protein-protein interaction networks of differentially expressed proteins involved in energy metabolism and protein regulations.

Discussion

In our previous study, we demonstrated the positive interaction of P. indica with B. napus in overall growth, yield, quality and nutritional attributes12. Further, to evaluate the proteomic changes during the multistep colonization process, relative changes in functional proteins has been assessed. We compared the treated and control plants in triplicates, resulted in identification of 46 significant DEPs in which 14 were increased and 32 were decreased. The previous gene expression studies demonstrated that, defense genes, signaling molecules, and transcription factors are upregulated during early stages of root colonization and down regulated gradually at later stages6,7,10,18. We speculate that, in our study, the colonization has been established during the harvesting time followed by enhanced plant growth, so this could be a possible reason of downregulation of 34 DEPs in proteomic analysis. Further, expression of DEPs finally leads to change in cellular morphology, physiological and metabolic conditions of host plant to establish successful symbiosis. Furthermore, functional annotation results in current proteomic approach with GO, KEGG and PPI network revealed the complex functions of proteomic-interactome in host-symbiont relationship (Figs 4 and 5). For instance, KEGG pathway analysis suggested a cluster of proteins which involves in regulation of cellular & biosynthetic process of carbohydrate, lipid and proteins along with metabolic regulation of nitrogenous compound and organic substances (Supplementary Table S5). In addition, functions of identified DEPs were further investigated to reveal the key factors participated in symbiotic associations.

DEPs involved in Defense Pathway

Our proteomic data revealed the elevated level of DEPs involved in the defense/stress/cellular detoxification related proteins including three types of peroxidases [12 (C7E9R4), 21(C7E9R5) and 69 (M4E663) isoforms), germin-like protein (GLP) subfamily 2 (A0A078FEH1), epidermis-specific secreted glycoprotein EP1 (A0A078J557), MLP-like protein (A0A0D3CXE3) and jacalin-related lectin 35 (M4E064) in roots upon P. indica treatment. The peroxidases belong to the class III secretary plant peroxidases, reside in plant vacuoles or intracellular spaces and involved in auxin catabolism, lignin synthesis, H2O2 detoxification and stress responses19. The GLP subfamily member is also participated in defense and is associated with various enzymatic activities comprising oxalate oxidase (OxO), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glucose pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (AGPPase), and serine protease inhibitors20. Song et al.13 suggested the role of lectin and GLP in defense during the interaction of AMF G. mosseae and A. fruticose. Additionally, EP1 and lectins are involved in carbohydrate recognition and glucan binding and play an important role during pathogen attack and maintain the cell integrity21,22. Earlier events suggest that initially root recognizes arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungus as a pathogen and trigger weak defense responses6,7. At this phase, defense genes are expressed and reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by the host against P. indica11. Zuccaro et al.23 studied the P. indica gene expression during colonization of barley roots and reported the elevated level of pre-penetration phase genes engaged in oxidative stress, flavonoid-phenolic compounds reduction, and extracellular dioxygenase activity and in advance stage of colonization stress-related genes, cytochrome P450, glutathione S-transferase, quinine-reductases were found elevated. P. indica exhibits biotrophic colonization strategy, which includes host’s cell death-associated colonization phase, reported in Arabidopsis and barley23–25. We hypothesized that these differentially expressed stress proteins accumulated in cell-death colonization phase which help the colonized plant to maintain the cell homeostasis and enhanced plant resistance from oxidative, biotic, edaphic and environmental stress during various growth and development stages.

DEPs related to pre-symbiotic and cellular signaling

The onset of symbiosis requires perception of chitin-based molecules (lipo)-chitooligosaccharides (LCO), short-chain lipochitooligosaccharides Myc-LCO, and short chitooligosaccharides (CO4) as putative symbiotic signal molecules derived from AM fungus, which is very similar to rhizobial NFs26,27. During the invasion of a foreign organism, a signaling cascade of plasma membrane-localized receptor complexes governs the mutualism through the variety of signaling molecules at root-soil interface. The signaling pathway involves various signal transducers to start molecular dialogue between both the partners like; lysine motif (LysM) domain carrying proteins, and leucine-rich-repeat receptor-like kinases (LRR-RLKs)27–30.

In P. indica colonized root of B. napus, we identified the LysM domain-containing GPI-anchored protein (M4CCU0), which corresponds to the chitin perception mechanism reported in rice30,31. During the onset of symbiosis, Myc-LCO/CO4/chitin is perceived by two plasma membrane receptor; CEBiP (Chitin elicitor binding protein) and CERK1 (Chitin elicitor receptor kinase) with LysM28,29 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Zipfel et al.29 suggested that successful colonization depends on the coordinated perception of Myc-LCO and Myc-chitin oligosaccharides in AM symbiosis29. LysM RLK RNAi knockdown experiments suggest the role of Myc–COs and LysM RLK during the initial AM fungal-host signaling in rice, legume and dicot non-legume plants27,32.

Here, we witnessed another protein, LRR receptor-like protein kinase At1g51890 (M4DQZ2), which enables to recognize fungal chitin, small peptide molecules and also proteins33 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Plant LRR-RLKs possess a functional cytoplasmic kinase domain to perform ser/thr kinase activity34. Previously, plasma membrane-localized LRR and MATH domain-containing proteins were also reported in P. indica symbiosis outcome with growth promotion24,35. Shahallori et al.36 reported a LRR protein named pii-2 in Arabidopsis, responsible for P. indica-mediated growth promotion and enhanced seed production.

Recognition of microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAPS) by host plants accelerates the downstream transmission of signals, which activate other receptors/proteins to regulate the series of cellular events. This leads to notable transcriptional changes to regulate the expression of symbiotic genes. These events mediated by the nuclear calcium oscillations in response to Myc-LCO, which is considered as a hallmark of symbiotic responses29,30. Our data contain following proteins related to calcium signaling; subtilisin-like protease SBT2.5 (A0A078FZ46), (significantly accumulated), calcium binding EF-hand family protein (L7PBC3), and calmodulin (CaM) related (Q710C9) (non-significant, Supplementary Table S1 - Total proteins). SBTs engaged in AM symbiosis and help the plant in ‘sym’ Pathway to perceive the LCOs signal generated by endosymbiotic fungus. This spawns the signaling cascade in root epidermis and subsequently develops the pre-penetration apparatus which lead to infecting the host tissue by arbuscules formation. Further, subtilase genes restructure the plasma membrane26,37.

Our findings support the role of LRR, LysM, calcium binding EF-hand family protein, SBTs, and CaM, mediated signaling in P. indica colonized B. napus. Supplementary Fig. S1 showed the proposed model of signaling during establishment of symbiosis between the plant and fungal partners.

DEPs in Cell architecture and cell wall remodeling

In this study, we also found significantly expressed proteins like receptor-like kinase TMK4 (M4EHS7), pectin acetylesterase (A0A078F4G5), monocopper oxidase [SKU5, a glycoprotein with GPI anchor (A0A078E9C4)] and reticuline oxidase (M4DWM1), responsible for the structural changes during endophytic colonization. The TMK subfamily acts in a functionally redundant manner and interacts with Auxin binding protein 1 (ABP1) to regulate ROP (Rho of Plant) signaling. This critically controls the cell expansion, division, proliferation and downstream of auxin at the cell surface38,39. The enzyme pectin acetylesterase is responsible for O-acetylation of pectin, which plays important role in maintaining cell wall architecture during growth and differentiation of plant tissues40. Similarly, monocopper oxidase regulates the multiple-copper oxidases which participate in directional root cell wall development and growth41,42. Another protein reticuline oxidase, a berberine bridge enzyme is also reported to be involved in the modification of cell wall architecture during growth and it also responds against the pathogen43. These signaling events and activation of cellular architecture proteins help the tissue to reorganize the structure which further helps fungi to develop a highly branched arbuscules inside the cortical cells. These arbuscules surrounded by plasma membrane-derived peri-arbuscular membrane localized various protein moieties which principally take part in nutrient acquisition30,32,44.

Proteins related to lipid, nitrogen and phosphorous metabolism

In plants, fatty acids and lipids are the building blocks of membranes and also required for the senescence, tolerance against cold temperatures and phosphate starvation which helps plants to perform better45,46. Here, two DEPs, 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] (FabB) synthase III (A0A0D3E4R7) and 3-hydroxyacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] dehydratase (FabZ) (M4CPB4) were significantly accumulated in P. indica colonized root (Fig. 6). The KEGG pathway study showed the role of FabB and FabZ as an intermediate candidate in metabolic flux distribution of fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (Supplementary Table S5). FabB-condensing enzyme along with other members is responsible to elongate the chain of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids in C12–C16 range of chain lengths and control the level of unsaturated fatty acids47. However, the FabZ protein is involved in dehydratase catalytic activity during the lipid A biosynthesis. Both DEPs take part in fatty acid elongation, degradation, and metabolism of glycerol-lipid, glycerol-phospholipid and lipoic acid that helps in providing raw materials to newly synthesized cells during root colonization47.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) associated with major metabolic protein networks during symbiotic association of P. indica and rapeseed plant. DEPs that have been significantly detected at the proteomics level were highlighted in green colored clouds.

Nitrogen (N) and phosphorous (P) metabolism are prominence factor in plant’s growth and development. N-acetyl-gamma-glutamyl-phosphate reductase (A0A078ILF0), aminoacylase (A0A0D3CNP2), and adenylosuccinate synthetase (A0A078EYR1), significantly expressed in this study, are key intermediate enzymes in arginine biosynthesis pathway and purine, arginine, glutamate, aspartate metabolic pathway, respectively (KEGG pathway, Supplementary Table S5). Upregulation of these pathways supports the enhanced nitrogen and phosphorous assimilation by P. indica in the colonized host plant. A similar study was performed by Govindarajuluet al.48 in AM symbiosis and concluded that nitrogen transferred from fungus as ammonium, is used in the synthesis of arginine which further broken down in ammonium and takes part in amino acid biosynthesis.49,50.

Previously, P. indica is reported to enhance phosphorous metabolic enzymes which contribute in higher phosphate uptake in plants44. In this study, enzyme glycero-phosphodiester phosphodiesterase GDPDL3 (M4ECA0) is significantly accumulated and helps in catalysis of phospholipids to break down into phosphodiesters, which further lead to release phosphorous by various intermediate steps51. Enhanced arginine metabolism and binding ability of arginine with polyphosphate also suggest its role in translocation of fungal phosphorous to host plants49. These events advocate that P. indica colonization possibly increase the uptake of phosphorous acquisition. In our previous study, we also reported ~17.58% & ~23.34% more nitrogen accumulation and 25.68% & 30.83% more phosphorous accumulation in B. napus leaves and seeds respectively, as compared to control12.

DEPs in Proteins synthesis and fate

During symbiosis, the RNA binding protein CPB 29B (A0A078IBN1), RNA binding motif protein 8A-B (RBM8A-B) (A0A078I917) and Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (A0A078GF82) were found significantly accumulated, which take part in protein synthesis and folding (Fig. 6). The CPB 29B is a member of small family cpRNPs which are engaged in RNA regulatory functions and reported in tobacco, associated to RNA stabilization. The cpRNPs bind to target internal sequences of endoribonucleases and protect it from degradation52. RBM8A together with Magoh, associated with decapping, methylosome activity, and centrosome maturation, and their deficiency results in G2/M accumulation, followed by cell apoptosis53. Nevertheless, Peptidyl-prolyl isomerases are enzymes that are responsible for protein folding by cis-trans isomerization of X-Pro peptide bonds and also bind to mature proteins to control their activity, subunit assembly and localization54,55. Other significantly accumulated DEPs are eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 (A0A078JH45), protein modifier of SNC1 11 (A0A078FBQ2) and DNA ligase 6 (M4CEX3), are important components of cellular protein synthesis and regulation.

During the symbiosis process, the cell metabolism is critically regulated by the periodical synthesis, modifications, degradation of peptides & proteins and programmed cell death. In our root proteome results, 26S proteasome (A0A0D3CS77), nudix hydrolase (A0A078CRI1), suppressor protein STM1-like (A0A078HY34), subtilisin-like protease SBT2.5 (A0A078FZ46) were found significantly upregulated (Fig. 6). From embryogenesis to seed shredding, majority phases of plant life require the selective degradation of regulatory proteins, which is tightly regulated by the ubiquitin-26S proteasome system. Apart from selective degradation, 26 proteasome helps to clean unwanted and abnormal intracellular proteins of cytoplasmic and nuclear origin via ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway to maintain cellular homeostasis during initial and advance stages of symbiosis. It is also engaged in protein trafficking, site-specific proteolysis and limiting the protein activity56–58.

Another accumulated important enzyme in our experiment was subtilisin-like protease SBT2.5, which utilizes the storage protein and is a key component to create plant architecture. It critically associated with whole plant cycle; including germination, vegetative and reproductive growth, embryo, flower, seed development to till senescence. SBTs play a crucial role in peptide hormone synthesis, and also contribute to signal biogenesis in plants26,58,59. Protein family nudix hydrolase is a small protein (16–21 kDa), known for cellular ‘house cleaning’ activity. It is engaged in RNA processing, the directive of ERK signaling, calcium channel, the breakdown of various deleterious endogenous metabolites including, a wide range of nucleoside di- and triphosphate derivatives, nucleotide sugars, and a various substrates specific RNA caps48,60. Fungal intervention with the host increases the metabolic activity for rapid growth, which produces lots of deleterious metabolites as a by-product of metabolic reactions. The above-explained proteins identified in our study supports our hypothesis that these are the key proteins which help to maintain the cellular homeostasis by house-cleaning activity of the host plant. PPI network also depicted the interactome network of DNA binding proteins participates in protein regulation during various biological process (triangle network in Fig. 4).

Proteins engaged in energy synthesis

PPI network reveals that the 16 proteins with 5 driver proteins centrally involved in energy metabolism (Fig. 5). These proteins regulate the carbohydrate metabolism and energy synthesis pathway to maintain energy need during symbiotic growth. Among the DEPs related to carbohydrate metabolism, acid β-fructofuranosidase (M4F6E3) is a key intermediate of galactose, starch and sucrose metabolism (KEGG pathway) and takes part in cell wall biosynthesis (Fig. 6 & Supplementary Table S5). Additionally, enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) (A0A0D3BFD4) is also an important component of carbohydrate metabolism and required for cell division and elongation61.

During the symbiosis, the NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha (M4E2D2), peptidylprolyl isomerase and ATP synthase (Complex V) (A0A0H3XZN3) were significantly accumulated in colonized rapeseed root, possibly played role in the enhanced growth and developmental process. The NADH dehydrogenase (oxidoreductase complex I) participates in electron transfers from NADH to ubiquinone in ETC and at the same time involved in proton translocation across the mitochondrial membrane. Subsequently passing from the various complexes I-IV, as a result, a proton gradient is formed inside the mitochondrial membrane and further this is used by the ATP synthase complex (complex V)62,63. The ATP synthase (the final enzyme in oxidative phosphorylation pathway) binds with mitochondrial F0 and F1 regions and catalyzes the terminal step of ATP formation using electrochemical gradient generated across the membrane by protons during oxidative respiration62–64. The membrane ATP synthase was studied in hosts Medicago truncatula and Pteris vittata, colonized by AM fungus Glomus intraradices65,66. Two fungal mitochondrial ATP synthase along with membrane ATPase activity was also detected by Becard et al.67 in pre-symbiotic phase suggested the role in energy-dependent functions in AM colonized host roots66,67. This study further supports our current host-symbiont proteome results.

ATP production is highly regulated by energy needs, thus the increase in ATP production suggests intense energy demand in the root of rapeseed that could coincide with the switch from asymbiotic to pre-symbiotic growth phase. Accumulation of energy-related DEPs suggests the energy required to maintain both the symbiotic partner together. In later stages, plant growth is enhanced and also the more intense hyphal branching of P. indica inside the root was observed.

Fungal DEPs and unknown proteins

Here, we identified total 56 proteins from P. indica expressed inside the B. napus root (Supplementary Table S1). Out of which, cysteine synthase (G4TTT8) enzyme was found significantly accumulated by label-free proteomics. During the initial colonization phase, reducing environment generates inside the fungus. Cysteine-containing molecules glutathione and thioredoxin protect the fungus against oxidative stress generated by reducing environment68. Out of 46 DEPs, three new symbiotic proteins from colonized rapeseed plant were appeared with unknown function and will be targeted for future study to understand the further role in symbiotic associations.

Figure 6 represents the tentative mapping of symbiotic proteins identified to major pathways of intercellular signaling, glucose and lipid metabolism, energy synthesis and protein regulation (synthesis, selective degradation, and protein lysis). These metabolic pathways are interconnected with each other and key sources of plant growth and development. The structure drawn is based on knowledge available from plants metabolic pathways. The represented proteins/enzymes span key steps of the various regulatory pathways modulated during symbiotic association of P. indica and B. napus.

In conclusion, the 46 DEPs identified in our study are the part of complex cellular and molecular processes in symbiotic association between host and fungus. The quantitative study of protein reveals their role in diverse physiological pathways. This study verifies the positive symbiosis between the host B. napus and AM fungi P. indica. Exploring these protein functions, our study provides a comprehensive understanding of root’s architectural modification, cell remodeling and maintenance of cellular homeostasis during the symbiotic and growth phase of plant’s life. Finally our study provided new candidate proteins to carry out further study on this beneficial association of plant-fungal interaction. These findings will further help the researchers to understand the molecular networks and modulation of biological pathways behind the plant-fungal interaction extensively.

Material and Methods

Fungus

The plant growth promoting fungus P. indica was collected from State key laboratory of Rice Biology, Institute of Biotechnology, Zhejiang University Hangzhou, China. P. indica was grown on modified Kafer medium69 at 25 °C for 5 days in the dark. The two fungal plugs (5 mm each) were picked out and inoculated into a glass petri dish (90 mm × 90 mm) which contains 50 ml of modified plant nutrient medium (PNM)70. The fungus was incubated at 25 °C for 7 days.

Plant Materials

For the experiments, B. napus seeds were collected from State key laboratory of Rice Biology, Institute of Biotechnology, Zhejiang University Hangzhou. Before the experiments, rapeseeds were soaked in distilled water for 12 h. The seeds were surface sterilized and inoculated in Murashige and Skoog medium71 for germination. The four-leaved rapeseed plantlets with consistent height were selected and transferred to new MS medium plate. The fungal hypha plug of 50 mm diameter from 7 days old P. indica, was inoculated 1 cm apart from the root of B. napus seedlings. Further, these plates were transferred to plant growth chamber under growth conditions 25/22 °C (day/night), 16/8 h (alternating light and dark), with a light intensity of 5,500 lx. The samples were harvested after four weeks; leaf, root and stem were separated. The roots were washed carefully in distilled water, weighted both separately and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Further, samples were stored in a −80 °C freezer until protein extraction.

Root Colonization study

The roots of 15 days old rapeseed seedlings were washed thoroughly with tap water, cut into small pieces (1 cm) and treated with 10% KOH solution at room temperature for overnight. The roots were rinsed repeatedly using sterile distilled water, then dipped in 1% HCl solution for 1 min and then stained with 0.05% trypan blue for 3–5 min, finally rinsed several times in sterile water. The stained roots were observed under an Olympus confocal microscope BX51 (Tokyo, Japan) for P. indica root colonization.

Protein extraction, digestion and desalting

To evaluate the proteins during interaction study, proteins were extracted from 28 days old B. napus root samples in triplicates (200 mg per plant) by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) - acetone - phenol method72. The protein concentration was measured by the Bradford method73. Further, 30 μl (approx. 100 μg) total protein was reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 30 mins at 37 °C, then alkylated with 100 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) for 20 mins at room temperature. Finally, samples were digested with 40 μl of 0.05 M ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) with trypsin (enzyme to protein ratio 1:50) and incubated overnight at 37 °C (followed according to manufacturer’s instructions - Millipore).

Mass spectrometry analysis

A Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) system consisting of a Nano-nLC 1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to a linear quadrupole ion trap–Orbitrap (LTQ Orbitrap Elite) mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source was used to analyze the tryptic peptides. Total 2 μg of peptides mixtures were separated by C18 reverse-phase chromatography on an Acclaim PepMap RSLC with a length of 15 cm, an inner diameter (i.d.) of 50 μm, and a particle size of 2 μm using a pre-column (Acclaim PepMap 100, length 2 cm, i.d., 75 μm, particle size 3 μm) and a mobile phase gradient from 3% to 8% (v/v) acetonitrile (ACN), 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (FA) in 10 min, 8% to 20% (v/v) ACN, 0.1% (v/v) FA in 15 min, 20% to 30% (v/v) ACN, 0.1% (v/v) FA in 17 min and 30% to 90% (v/v) ACN, 0.1% (v/v) FA in 8 min with a flow rate of 250 nL/min. Peptides were electro sprayed online into an LTQ-Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer via a ProxeonNanoSpray Flex Ion Source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 1.8 kV (source voltage) and the temperature was set at 300 °C. Peptides were detected by full scan mass analysis from m/z 300–2,000 at resolving power of 60,000 (at m/z 400, measured at full width at half-maximum peak height (FWHM); 1-s acquisition). Collision-induced dissociation (CID) was applied as the fragmentation technique with a collision energy of 35 eV. MS/MS with rolling collision energy of the 20 most intense precursor ions with charge states 2+ to above.The spectral data was acquired by ThermoXcalibur version 3.0.

Protein identification and quantification

The raw spectrum files were processed and quantitative ratio determined using PEAKS Studio version 8 (Bioinformatics Solutions) with a parent mass tolerance of 25.0 ppm, and fragment tolerance of 0.8 Da. PEAKS studio 8 was used to interrogate a custom database containing all Piriformospora and Brassica proteins on UniProt database combined with Post-translational modifications (PTMs). To assess modifications carbamidomethyl was set as fixed, oxidation, deamidation, and 482 built-in-modifications were set as variables. Maximum missed cleavage was set at 3 and false detection rate (FDR) < 1%. For the quantification we used label-free proteomics to identify the differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) with significant score (−10lgP) > 13 were used for protein acceptance. Minimum unique peptide was set at 1. Highly differentially expressed proteins between control and treatment groups were identified by statistical analysis tool (fold change > 2, FDR < 1%) and presented in heatmap format (generated by PEAKS studio 8). The ANOVA was used to calculate significance (in-build in Peak Studio 8).

Data analysis

Plant experiments performed in-vitro were arranged in a completely randomized design and assessed in triplicates. The standard error was evaluated for each experimental group. Blast2GO software (http://www.blast2go.com/b2ghome) was used to annotate all identified proteins using Gene Ontology (GO terms) and molecular function, biological process, and cellular component were determined. Mapping of DEPs and pathway analysis were carried out through Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/pathway.html)74. The protein-protein interaction network obtained using input into Cytoscape version 2.8.3.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information - Table S5, Figure S1 and File S1

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Prasun Bandhypadhyay (ICGEB-New Delhi) and Dr. Akhileshwar Namani (Zhejiang University) to critically analyze the manuscript. This work was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2016C02050-8).

Author Contributions

Experiment design: Qikang Gao and Binggan Lou, Plant experiments and Protein extraction: Jiang Li and Xingyuan Luo, and Pan Li, LC/MS experiments: Neeraj Shrivastava, Interpretation of proteomic data: Qikang Gao and Neeraj Shrivastava, Manuscript preparation: Neeraj Shrivastava, Figure concept and design: Archana Kumari Sharma and Rashmi Pandey, Protein-protein interaction network: Sanling Wu and Archana Kumari Sharma, Manuscript correction and language edition: Binggan Lou and Neeraj Shrivastava. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23994-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hu Z, et al. Unusually large oil bodies are highly correlated with lower oil content in Brassica napus. Plant Cell Rep. 2009;28:541–549. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu, C., Napier, J. A., Clemente, T. E. & Cahoon, E. B. New frontiers in oilseed biotechnology: meeting the global demand for vegetable oils for food, feed, biofuel, and industrial applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22, 252–259 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Karim MM, et al. Production of high yield short duration Brassica napus by interspecific hybridization between B. oleracea and B. rapa. Breed Sci. 2014;63:495–502. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.63.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wanasundara, J. P. D., Tan, S., Alashi, A. M., Pudel, F. & Blanchard, C. Proteins from Canola/Rapeseed Current Status. In Sustainable Protein Sources. (Nagathur, S) 285–304 (Academic, 2016).

- 5.Aloui A, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis elicits shoot proteome changes that are modified during cadmium stress alleviation in Medicago truncatula. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strehmel N, et al. Piriformospora indica stimulates root metabolism of Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1091. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vahabi K, et al. The interaction of Arabidopsis with Piriformospora indica shifts from initial transient stress induced by fungus-released chemical mediators to a mutualistic interaction after physical contact of the two symbionts. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0419-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camehl I, et al. Ethylene signaling and ethylene-targeted transcription factors are required to balance beneficial and nonbeneficial traits in the symbiosis between the endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica and Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2010;185:1062–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varma A, Bakshi M, Lou B, Hartmann A, Oelmueller R. Piriformospora indica: a novel plant growth-promoting mycorrhizal fungus. Agric Res. 2012;1:117–131. doi: 10.1007/s40003-012-0019-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vahabi K, Camehl I, Sherameti I, Oelmüller R. Growth of Arabidopsis seedlings on high fungal doses of Piriformospora indica has little effect on plant performance, stress, and defense gene expression in spite of elevated jasmonic acid and jasmonic acid-isoleucine levels in the roots. Plant Signal Behav. 2013;8:e26301. doi: 10.4161/psb.26301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuo M, et al. High redox responsive transcription factor1 levels result in accumulation of reactive oxygen species in Arabidopsis thaliana shoots and roots. Mol Plant. 2015;8:1253–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su ZZ, et al. Piriformospora indica promotes growth, seed yield and quality of Brassica napus L. Microbiol. Res. 2017;199:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song F, et al. Proteomic analysis of symbiotic proteins of Glomus mosseae and Amorpha fruticosa. Scientific reports. 2015;5:18031. doi: 10.1038/srep18031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernardo, L. et al. Proteomic insight into the mitigation of wheat root drought stress by arbuscular mycorrhizae. J. Proteomics, 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.03.024 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Vannini C, et al. An interdomain network: the endobacterium of a mycorrhizal fungus promotes antioxidative responses in both fungal and plant hosts. New Phytol. 2016;211:265–275. doi: 10.1111/nph.13895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghabooli M, et al. Proteomics study reveals the molecular mechanisms underlying water stress tolerance induced by Piriformospora indica in barley. J. Proteomics. 2013;94:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alikhani M, et al. A proteomics approach to study the molecular basis of enhanced salt tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) conferred by the root mutualistic fungus Piriformospora indica. Mol. Biosyst. 2013;9:1498–1510. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70069k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafiqi M, Jelonek L, Akum NF, Zhang F, Kogel KH. Effector candidates in the secretome of Piriformospora indica, a ubiquitous plant-associated fungus. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:228. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchler BA, Bryant SH. CD-Search: protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acid. Res. 2004;32:327–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barman AR, Banerjee J. Versatility of germin-like proteins in their sequences, expressions, and functions. Funct. Integ. Genomic. 2015;15:533–548. doi: 10.1007/s10142-015-0454-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelen FA, et al. The carrot secreted glycoprotein gene EP1 is expressed in the epidermis and has sequence homology to Brassica S-locus glycoproteins. Plant J. 1993;5:855–862. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1993.04050855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Schutter K, Van Damme EJ. Protein-carbohydrate interactions as part of plant defense and animal immunity. Molecules. 2015;20:9029–9053. doi: 10.3390/molecules20059029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuccaro A, et al. Endophytic life strategies decoded by genome and transcriptome analyses of the mutualistic root symbiont Piriformospora indica. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002290. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill, S. S. et al. Piriformospora indica: potential and significance in plant stress tolerance. Front. Microbiol7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Qiang X, Zechmann B, Reitz MU, Kogel KH, Schafer P. The mutualistic fungus Piriformospora indica colonizes Arabidopsis roots by inducing an endoplasmic reticulum stress–triggered caspase-dependent cell death. Plant Cell. 2012;24:794–809. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.093260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maillet F, et al. Fungal lipochitooligosaccharide symbiotic signals in arbuscular mycorrhiza. Nature. 2011;469:58. doi: 10.1038/nature09622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buendia L, Wang T, Girardin A, Lefebvre B. The LysM receptor-like kinase SlLYK10 regulates the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in tomato. New Phytol. 2016;210:184–195. doi: 10.1111/nph.13753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyata K, et al. Evaluation of the role of the LysM receptor-like kinase, OsNFR5/OsRLK2 for AM symbiosis in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57:2283–2290. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zipfel C, Oldroyd GE. Plant signalling in symbiosis and immunity. Nature. 2017;543:328–336. doi: 10.1038/nature22009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antolín-Llovera M, et al. Knowing your friends and foes–plant receptor-like kinases as initiators of symbiosis or defense. New Phytol. 2014;204:791–802. doi: 10.1111/nph.13117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gong BQ, et al. Rice Chitin Receptor OsCEBiP Is Not a transmembrane protein but targets the plasma embrane via a GPI anchor. Mol. Plant. 2017;10:767–770. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carotenuto G, et al. The rice LysM receptor-like kinase OsCERK1 is required for the perception of short-chain chitin oligomers in arbuscular mycorrhizal signaling. New Phytol. 2017;214:1440–1446. doi: 10.1111/nph.14539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu PL, Du L, Huang Y, Gao SM, Yu M. Origin and diversification of leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase (LRR-RLK) genes in plants. BMC Evol Biol. 2017;17:47. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0891-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diévart A, Clark SE. LRR-containing receptors regulating plant development and defense. Development. 2004;131:251–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.00998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oelmüller R, Peškan-Berghöfer T, Shahollari B, Sherameti I, Varma A. MATH-domain containing proteins represent a novel gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana and are involved in plant/microbe interactions. Physiol. Plant. 2005;124:152–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00505.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shahollari B, Vadassery J, Varma A, Oelmüller R. A leucine-rich repeat protein is required for growth promotion and enhanced seed production mediated by the endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007;50:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor A, Qiu YL. Evolutionary history of subtilases in land plants and their involvement in symbiotic interactions. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2017;30:489–501. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-16-0218-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao Y, et al. Auxin binding protein 1 (ABP1) is not required for either auxin signaling or Arabidopsis development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:2275–2280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500365112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu T, et al. Cell surface ABP1-TMK auxin-sensing complex activates ROP GTPase signaling. Science. 2014;343:1025–1028. doi: 10.1126/science.1245125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hloušková P, Bergougnoux V. A subtracted cDNA library identifies genes up-regulated during PHOT1-mediated early step of de-etiolation in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) BMC genomics. 2016;17:291. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2613-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sedbrook JC, Carroll KL, Hung KF, Masson PH, Somerville CR. The Arabidopsis SKU5 gene encodes an extracellular glycosyl phosphatidylinositol–anchored glycoprotein involved in directional root growth. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1635–1648. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song W, et al. N-glycan occupancy of Arabidopsis N-glycoproteins. J. Proteomics. 2013;93:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nawrot R, Barylski J, Lippmann R, Altschmied L, Mock HP. Combination of transcriptomic and proteomic approaches helps to unravel the protein composition of Chelidoniummajus L. milky sap. Planta. 2016;244:1055–1064. doi: 10.1007/s00425-016-2566-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nath, M. et al Reactive oxygen species generation-scavenging and signaling during plant-arbuscular mycorrhizal and Piriformospora indica interaction under stress condition. Front. Plant Sci. 7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Troncoso-Ponce MA, Cao X, Yang Z, Ohlrogge JB. Lipid turnover during senescence. Plant Sci. 2013;205:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li N, Xu C, Li-Beisson Y, Philippar K. Fatty acid and lipid transport in plant cells. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beld J, Lee DJ, Burkart MD. Fatty acid biosynthesis revisited: structure elucidation and metabolic engineering. Mol. Biosyst. 2015;11:38–59. doi: 10.1039/C4MB00443D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLennan AG. The Nudix hydrolase superfamily. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:123–143. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5386-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Govindarajulu M, Pfeffer PE, Jin H, Abubaker J. Nitrogen transfer in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature. 2005;435:819. doi: 10.1038/nature03610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fellbaum CR, et al. Carbon availability triggers fungal nitrogen uptake and transport in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:2666–2671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118650109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng Y, et al. Characterization of the Arabidopsis glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase (GDPD) family reveals a role of the plastid-localized AtGDPD1 in maintaining cellular phosphate homeostasis under phosphate starvation. Plant J. 2011;66:781–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamura T, Ohta M, Sugiura M, Sugita M. Chloroplast ribonucleoproteins function as a stabilizing factor of ribosome-free mRNAs in the stroma. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:147–152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishigaki Y, Nakamura Y, Tatsuno T, Ma S, Tomosugi N. Phosphorylation status of human RNA-binding protein 8A in cells and its inhibitory regulation by Magoh. Exp. Biol. Med. 2015;240:438–445. doi: 10.1177/1535370214556945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brechenmacher L, et al. Expression profiling of up-regulated plant and fungal genes in early and late stages of Medicago truncatula-Glomus mosseae interactions. Mycorrhiza. 2004;14:253–262. doi: 10.1007/s00572-003-0263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrey SD, Schellhammer M, Ecke M, Hampp R, Tarkka MT. Mycorrhiza helper bacterium Streptomyces AcH 505 induces differential gene expression in the ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita muscaria. New Phytol. 2005;168:205–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sadanandom A, Bailey M, Ewan R, Lee J, Nelis S. The ubiquitin-proteasome system: central modifier of plant signalling. New Phytol. 2012;196:13–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vierstra RD. The ubiquitin–26S proteasome system at the nexus of plant biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:385. doi: 10.1038/nrm2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schaller A, Stintzi A, Graff L. Subtilases–versatile tools for protein turnover, plant development and interactions with the environment. Physiol. Plant. 2012;145:52–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schardon K, et al. Precursor processing for plant peptide hormone maturation by subtilisin-like serine proteinases. Science. 2016;354:1594–1597. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ji X, Gai Y, Zheng C, Mu Z. Comparative proteomic analysis provides new insights into mulberry dwarf responses in mulberry (Morusalba L.) Proteomics. 2009;9:5328–5339. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi H, Greenway H, Matsumura H, Tsutsumi N, Nakazono M. Rice alcohol dehydrogenase 1 promotes survival and has a major impact on carbohydrate metabolism in the embryo and endosperm when seeds are germinated in partially oxygenated water. Ann. Bot. 2014;113:851–859. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsieh WY, et al. The Slow Growth 3 pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for the splicing of mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit7 intron 2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015;168:490–501. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schertl, P. & Braun, H. P. Respiratory electron transfer pathways in plant mitochondria. Front. Plant Sci5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Yoshida M, Muneyuki E, Hisabori T. ATP synthase-a marvellous rotary engine of the cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:669. doi: 10.1038/35089509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bona E, et al. Proteomic analysis as a tool for investigating arsenic stress in Pteris vittata roots colonized or not by arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. J. Proteomics. 2011;74:1338–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valot B, et al. Identification of membrane-associated proteins regulated by the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;59:565–580. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-8269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bécard G, Kosuta S, Tamasloukht M, Séjalon-Delmas N, Roux C. Partner communication in the arbuscular mycorrhizal interaction. Can. J. Bot. 2004;82:1186–1197. doi: 10.1139/b04-087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lithgow JK, Hayhurst EJ, Cohen G, Aharonowitz Y, Foster SJ. Role of a cysteine synthase in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:1579–1590. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.6.1579-1590.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hill TW, Kafer E. Improved protocols for Aspergillus minimal medium: trace element and minimal medium salt stock solutions. Fungal Genet. Rep. 2001;48:20–21. doi: 10.4148/1941-4765.1173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vadassery J, et al. A cell wall extract from the endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica promotes growth of Arabidopsis seedlings and induces intracellular calcium elevation in roots. Plant J. 2009;59:193–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang W, Vignani R, Scali M, Cresti M. A universal and rapid protocol for protein extraction from recalcitrant plant tissues for proteomic analysis. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2782–2786. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information - Table S5, Figure S1 and File S1