Abstract

The antimicrobial peptide LyeTxI isolated from the venom of the spider Lycosa erythrognatha is a potential model to develop new antibiotics against bacteria and fungi. In this work, we studied a peptide derived from LyeTxI, named LyeTxI-b, and characterized its structural profile and its in vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activities. Compared to LyeTxI, LyeTxI-b has an acetylated N-terminal and a deletion of a His residue, as structural modifications. The secondary structure of LyeTxI-b is a well-defined helical segment, from the second amino acid to the amidated C-terminal, with no clear partition between hydrophobic and hydrophilic faces. Moreover, LyeTxI-b shows a potent antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative planktonic bacteria, being 10-fold more active than the native peptide against Escherichia coli. LyeTxI-b was also active in an in vivo model of septic arthritis, reducing the number of bacteria load, the migration of immune cells, the level of IL-1β cytokine and CXCL1 chemokine, as well as preventing cartilage damage. Our results show that LyeTxI-b is a potential therapeutic model for the development of new antibiotics against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Keywords: LyeTxI, Lycosa erythrognatha, LyeTxI-b, antimicrobial peptide, septic arthritis

Introduction

Super-resistant bacteria are an emerging public health problem. The urge to develop new tools and strategies to combat the superbugs is clear and was vehemently warned by the World Health Organization in a report about the global threat of antimicrobial resistance, in June 2014 (WHO, 2014). In a majority, this problem is associated with an evolutionary adaptation of bacteria that are found in a multicellular specialized formation called biofilm, which increases the resistance to conventional antibiotics (de la Fuente-Nunez et al., 2013, 2016). Thus, biofilm represents a challenge to treat. In the meantime, AMPs have become a new hope as tools against superbugs, as they are the primary immune defense of animals and can also be found in bacteria, fungi, and plants (Bulet et al., 1999; Ageitos et al., 2017). Although AMPs are less likely to induce resistance in bacteria, there are several studies demonstrating that these molecules induce resistance by multiple mechanisms, as increasing expression of proteases that can cleave the peptide, modifying plasma membrane composition and pump efflux (Nizet, 2006; Andersson et al., 2016). However, recently it has been shown that combination of different phylogenetic taxa AMPs, decrease the evolution of microbial resistance against them (Dobson et al., 2013). In addition, AMPs and derived peptides have shown activity against infections due to biofilm formation (de la Fuente-Nunez et al., 2016).

Antimicrobial peptides are typically composed of 7–44 amino acid residues, usually exhibiting amphipathic alpha helix or beta-sheet conformations and being positively charged (Jenssen et al., 2006; Mookherjee and Hancock, 2007; Dawson and Liu, 2008; Epand and Epand, 2011; Wang et al., 2012), although other structural arrangements such as random coil, beta turn, helix-loop-helix, and coiled coil conformations have also been observed (Ghosh et al., 2014; Datta et al., 2015; Verly et al., 2017). Most of the works in literature correlate the activity of these compounds to their membrane-interactions and membrane-disruptive properties (Yang et al., 2001; Bechinger and Gorr, 2017). However, a rising number of works have described the action of the peptides on interactions with intracellular components as DNA, proteins, and also some enzymes (Brogden, 2005; Azim et al., 2016).

A great variety of molecules, such as amino acids, polyamines, proteins, and peptides can be found in spider venoms, including Lycosa erythrognatha. In particular, the venom peptides can interact with ion channels and cell receptors, and some of them show antimicrobial activity (Santos et al., 2016). Most of the investigations on AMPs isolated from spiders have proved the activity of several of these compounds against planktonic bacteria or fungi, although many studies have also shown their activities against bacteria biofilms (Overhage et al., 2008; Ageitos et al., 2017).

Our group previously isolated and characterized a new peptide, named LyeTxI, from the venom of the spider Lycosa erythrognatha (Santos et al., 2010). LyeTxI shows strong antibacterial and antifungal activities, as well as a weak hemolytic activity in high concentrations. Moreover, this peptide inhibits periodontal pathogens and epithelial cells proliferation (Consuegra et al., 2013). Recently, our group showed that LyeTxI and its formulation in beta-cyclodextrin, besides being active against periodontopathic bacteria, can also be used to prevent biofilm development (Cruz Olivo et al., 2017).

Nowadays, several efforts have been made to design molecules derived from AMPs with better efficacy, low possibility to induce resistance and with less potential toxicity. Due to the great biotechnological/pharmaceutical potential of LyeTxI, its structure can be used as a template to develop new antibiotics against planktonic bacteria and fungi. Therefore, in the present work, we describe the structure and the biological activity, both in vitro (planktonic bacteria) and in vivo (a model of septic arthritis in mice), of LyeTxI-b, a peptide derived from LyeTxI. This peptide contains two structure modifications as acetylated N-terminal and a deletion of a His residue. These modifications have altered its structure and improved its activity in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Peptide Synthesis and Purification

The peptide LyeTxI-b (CH3CO-IWLTALKFLGKNLGKLAKQQLAKL-NH2), was synthesized by stepwise solid-phase using the N-9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) strategy (Chan and White, 2000) on a Rink-amide resin (0.68 mmol⋅g-1). The following side-chain protecting groups were used: t-butyl for threonine, t-butyloxycarbonyl for lysine and tryptophan, (triphenyl)methyl for asparagine and glutamine. The couplings were performed with 1,3-diiso-propylcarbodiimide (DIC), dichloromethane in DMF for 3–4 h. Fmoc deprotection steps were carried out with piperidine/DMF (1:4; v:v) (20 min, twice). The last residue was deprotected and washed to perform the acetylation with a solution comprising 2 mL DMF, 1 mL DCM, 0.11 mol.L-1 DIC and 364.4 μl of 99% acetic anhydride (Sigma-Aldrich) for 40 min. The cleavage step and the side chains deprotection were performed with TFA/thioanisole/water/1,2-ethanedithiol/triisopropylsilane, (86.5/5.0/5.0/2.5/1.0, by volume) at room temperature during 3 h. The final product was precipitated with cold diisopropyl ether and lyophilized.

Two steps RP-HPLC were performed to purify the crude peptide. The first purification was done using a semi-preparative Discovery® BIO Wide Pore C18 column (Supelco), previously equilibrated with 0.1% aqueous TFA (solvent A). The elution was performed with a stepped gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA (solvent B) (0–40% of solvent B in 4 min; 40–55% of solvent B in 50 min; 55–100% of solvent B in 5 min). The flow was 5.0 mL.min-1 and detection at 220 nm. The PepMap C18TM column (4.6 mm × 150 mm) previously equilibrated with solvent A was used in the second purification. The peptide fraction was eluted with a linear gradient of solvent B (0–100% of solvent B in 30 min). The flow was 1.0 mL.min-1 and detection at 214 nm.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The quality of peptide synthesis and purification were evaluated by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry analyses carried out on an AutoFlex III instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, United States). The samples were co-crystallized with CHCA matrix (1:1, v/v) on MTP AnchorChip 400/384 or 600/384 plates (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, United States). The instrument was operated in positive reflector mode and the results were analyzed on FlexAnalysis 3.1 (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, United States).

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

The secondary structure preferences of LyeTxI-b were investigated by CD spectroscopy for the peptide in TFE:H2O solutions (0:100; 10:90; 20:80; 30:70; 40:60; 50:50; 60:40), in the presence of SDS micelles (detergent concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 30.0 mM), and in the presence POPC:POPG (3:1 mol:mol) phospholipid vesicles (lipid concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 2.0 mM). The spectra were recorded at 20°C on a Jasco- J-735 spectropolarimeter coupled to a Peltier Jasco PTC-423L (Tokyo, Japan). A rectangular quartz cuvette (1.0 mm path length; NSG, Farmingdale NY, United States) was used. Spectra were acquired from 260 to 190 nm using a 1.0 nm spectral bandwidth, 0.2 nm step resolution, 50 nm.min-1 scan speed, and 1 s response time. 6, 6, and 8 accumulations were, respectively, performed for the peptide samples prepared in TFE:H2O solutions, in the presence of detergent micelles and in the presence of phospholipid vesicles. Similar experiments with the respective blank solutions were also carried out for background subtraction. The peptide concentration, as determined from the tryptophan molar absorptivity (e = 5,550 M-1 cm-1 at 280 nm), was at 36.5 nmol.L-1 in all CD studies. The POPC:POPG (3:1) phospholipid vesicles were prepared as described elsewhere (Gusmao et al., 2017).

Two-Dimensional Solution NMR Spectroscopy

Two-dimensional solution NMR experiments were carried out to determine the three-dimensional structure of LyeTxI-b. Samples were prepared by dissolving the peptide in a mixture of TFE-d2/H2O (60:40%, v/v) at 2.0 mM, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 20 mM aqueous phosphate buffer. All NMR experiments were performed at 20°C on a Bruker Avance III spectrometer operating at a 1H frequency 600.043 MHz. A 5 mm triple-resonance (1H/13C/15N) gradient probe was used for all experiments. Water suppression was achieved by using pre-saturation. All NMR spectra were processed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al., 1995).

Total correlation spectroscopy spectrum was acquired using the MLEV-17 pulse sequence (Bax and Davis, 1985) with a spin-lock time of 60 ms. The following parameters were used: spectral width of 6602 Hz, 512 t1 increments were collected with eight transients of 4096 points. NOESY spectra (Kumar et al., 1980) was acquired using mixing times of 80, 100, and 150 ms to check for spin diffusion. The parameters were used as follows: spectral width of 6602 Hz, 512 t1 increments were collected with 32 transients of 4096. 1H-13C HSQC spectra were acquired with F1 and F2 spectral widths of 12820 Hz and 6602 Hz, respectively. 256 t1 increments were collected with 64 transients of 1024 points. Experiments were acquired in an edited mode in such a way that CH and CH3 correlations showed a positive phase and CH2 correlations showed a negative phase (Willker et al., 1993). 1H-15N HMQC spectra were acquired with F1 and F2 spectral widths of 1824 Hz and 6602 Hz, respectively, using a fast pulse sequence (Schanda and Brutscher, 2005). 128 t1 increments were collected with 800 transients of 1024 points.

NOE Data and Structure Calculations

The NMR spectra were analyzed using NMRView, version 5.0.3 (Johnson and Blevins, 1994). NOE intensities obtained at 150 ms mixing time were converted into 323 semi-quantitative distance restrains (190 intraresidue, 69 sequential and 64 medium range distance restrains) using the calibration described by Hyberts et al. (1992). The upper limits of the distance restrain thus obtained were 2.8, 3.4, and 5.0 Å (strong, medium, and weak NOE, respectively). Forty-four dihedral angle restrains were obtained from analysis of Cα, Hα, Cβ, N, and HN chemical shifts with the program TALOS+ (Shen et al., 2009). Structure calculations were performed using the Xplor-NIH software, version 2.27 (Schwieters et al., 2003). A total of 100 structures, starting with an extended conformation, were generated using a simulated annealing protocol, followed by 20,000 steps of simulated annealing at 1,000 K and a subsequent decrease in temperature in 15,000 steps in the first slow-cool annealing stage. The stereochemical quality of the lowest energy structures was analyzed by PROCHECK-NMR (Laskowski et al., 1996). The display, analysis, and manipulation of the three-dimensional structures were performed with the program MOLMOL (Koradi et al., 1996).

Antimicrobial Tests

Strains of Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) were cultured on BHI agar in aerobic conditions, while strains of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (ATCC 29522) and Streptococcus sanguinis (ATCC 10556) were cultured on BHI in anaerobic conditions. The MIC using the microdilution method was performed to determine the bacterial susceptibility to AMPs, as previously described (Wiegand et al., 2008). Samples of LyeTxI-b were serially diluted from 91.25 to 0.17 μmol/L in MH broth and incubated with 105 CFU/well for 24 h at 37°C. MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the peptide that prevented the visible growth of the microorganism. Also, minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) values were determined by plating an aliquot of MIC values by well, with no visible turbidity, in BHI agar, in aerobic conditions for E. coli and S. aureus, and in anaerobic conditions for A. actinomycetemcomitans and S. sanguinis. After 24–48 h of growth, the MBC value was determined as the lowest concentration of peptide with no visible bacterial growth on the surface of the agar. MIC and MBC assays were performed in triplicate.

Hemolytic Assay

The hemolytic assays were performed as previously described (Santos et al., 2010), with modifications. Briefly, lamb erythrocytes were incubated with a serial concentration dilution of the peptide (91.25 μmol.L-1 to 0.17 μmol.L-1) for 1 h at 37°C. The released hemoglobin was measured using a spectrophotometry at 405 nm. Triton X-100% was used as positive control.

Experimental Models of Arthritis

Staphylococcus aureus-Induced Arthritis

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 was grown in BHI agar supplement with 5% of sheep blood for 24 h. The inoculum (107 CFU.mL-1) was injected into the tibiofemoral joint of anesthetized C57BL/6j mice as described (Amaral et al., 2016), while negative controls received saline injections. Treatments were performed directly into the joint, with LyeTxI-b (0.03 nmol), clindamycin (7.0 nmol) or saline, each starting 48 h after the bacterial injection. Seven days after the injection of the inoculum, mice were euthanized under an overdose of ketamine/xylazine anesthesia, followed by cervical dislocation, for analyses.

Antigen-Induced Arthritis (AIA)

C57BL/6j mice were immunized on day 1 with intradermal injection of 500 μg of mBSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States) in 50 μL PBS emulsified in 50 μL Freund’s complete adjuvant (CFA; Sigma-Aldrich). Fourteen days later, the antigen challenge was performed by injecting 10 μg mBSA (in 10 μL sterile saline) in the right knee joint of each mouse. Mice were then intra-articularly treated with LyeTxI-b (0.03 nmol) 1 h before the challenge and 3 h after the challenge. All procedures were performed under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. Analyses were conducted 24 h after the challenge. Non-immunized mice were used as negative controls. Euthanasia was performed as mentioned above.

In vivo experiments were carried out in accordance and approved by the local Animal Experiment Ethics Committee (CETEA-UFMG; protocol no. 236/2014).

Inflammatory Parameters Analysis

After mice euthanasia, the intra-articular cavity was exposed and washed with PBS containing 3% of bovine serum albumin (2× 5 μL). The total number of leukocytes and differential leucocytes was counted using a Neubauer chamber and cytospin preparations (Shandon III; Thermo Shandon, Frankfurt, Germany) stained with May–Grunwald–Giemsa, respectively. Then, the periarticular tissue was removed for cytokine analyses. IL-1β and CXCL1 chemokine concentrations were measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), following the instructions supplied by the manufacturer (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, United States).

In another set of experiments, mice were euthanized for the analysis of proteoglycan loss in joint cartilage, a marker of cartilage damage. Tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formalin (pH 7.4), decalcified for 30 days in 14% EDTA. Samples were embedded in paraffin and then sectioned and stained with toluidine blue. Two sections/knee joint were microscopically examined by a single pathologist to estimate joint proteoglycan content, as previously described (Urech et al., 2010). The joint surface images of each sample were acquired and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States). Cartilage proteoglycan content was defined as the percentage of TB-stained area in relation to the total evaluated cartilage surface.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Liquid Chromatography

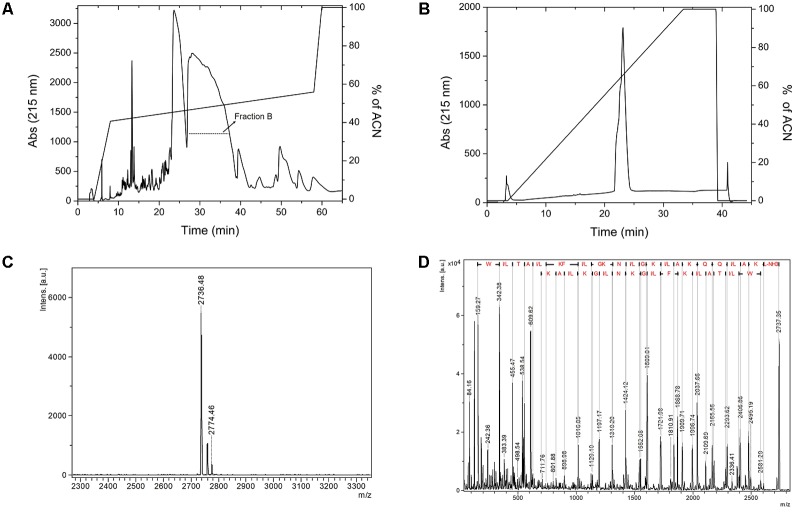

After chemical synthesis, we purified the peptide using two-step RP-HPLC. The first RP-HPLC assay on Discovery® BIO Wide Pore C18 column (Figure 1A) shows two major fractions eluted with an acetonitrile gradient (50–55% of solvent), named fraction A and fraction B. Only fraction B was submitted to another RP-HPLC experiment on a PepMap C18TM (Figure 1B), and the relative purity of the fraction was analyzed by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. The peptide of interest was eluted in fraction B, which was evidenced by a higher m/z intensity 2736.4, corresponding to the expected mass of the N-terminally acetylated peptide (MW 2737.3 Da) (Figure 1C). The peptide was therefore named LyeTxI-b. To confirm the primary structure of LyeTxI-b, this compound was subjected to MS/MS fragmentation (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Purification and mass spectrometry analyses of LyeTxI-b synthetic peptide. (A) The crudely synthesized peptide was first purified by RP-HPLC using Discovery® Bio Wide Pore C18TM column (Supelco) with a stepped gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA. (B) Purification of fraction B by RP-HPLC on PepMap C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm). The column was previously equilibrated with 0.1% aqueous TFA and the peptide eluted with a linear gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA. (C) LyeTxI-b was analyzed by MALDI-TOF-TOF mass spectrometry and (D) the primary sequence was confirmed by MS/MS using LIFT fragmentation.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

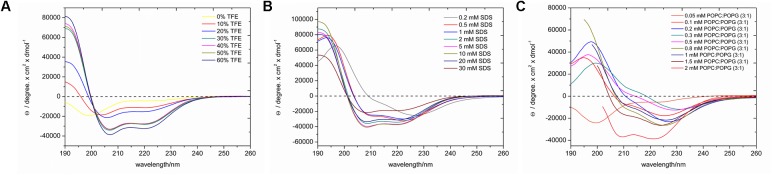

LyeTxI-b exhibits random coil conformations in the aqueous environment, as evidenced by the minimum near 200 nm in Figure 2A. Upon addition of TFE, the peptide adopts a helical conformation, as noticed by the appearance of two minima near 208 and 222 nm and a maximum near 192 nm (Figure 2A), which show relatively small intensities up to 20% of TFE, however, significant increases are observed in solutions containing 30–50% of TFE, which present very similar spectral profiles. This is a very common feature of linear cationic AMPs peptides, which show no conformational preferences in aqueous environments, whereas well-defined conformations are observed in the presence of organic co-solvents or other membrane mimetic environments (Gusmao et al., 2017). Interestingly the spectrum obtained for the peptide in the presence of 60% of TFE is consistent with even higher helical contents. Some investigations using small angle X-ray and dynamic light scattering of different alcohol–water solutions have indicated the formation local clusters, which reach maximum size at about 40% of the co-solvent in the case of TFE:H2O mixtures, whereas higher concentrations of TFE lead to smaller size clusters due to a higher homogeneity of the respective solutions (Kuprin et al., 1995; Gast et al., 2001; Othon et al., 2009). The larger aggregates may reduce the local polarity near the peptide and induce intramolecular bond formation or peptide aggregation, which can be correlated to differences in helicity. Since a higher helicity is observed in the presence of 60% of TFE and to avoid complications due to the formation of local aggregates, we decided to investigate in atomic detail the three-dimensional structure of LyeTxI-b by NMR spectroscopy in a solution containing 60% of the co-solvent (see below).

FIGURE 2.

CD spectra of LyeTxI-b in the presence of (A) TFE:H2O solutions, (B) SDS micelles, and (C) POPC:POPG (3:1) vesicles. At higher phospholipid concentrations light scattering artifacts strongly increase at short wavelengths (≤203 nm) and only the spectral components used for the analysis are shown in (C).

In order to confirm the helical conformation in membrane mimetic environments, the secondary structural preferences were also investigated in the presence of SDS micelles and POPC:POPG (3:1) vesicles and spectra with helical profiles were observed in both cases. In the presence of the micellar detergent (Figure 2B), the intensities of the characteristic maximum and minima increase with the SDS concentration until a plateau (5 mM of SDS) is reached. In the presence of vesicles (Figure 2C), the minimum and maxima intensities also increase with the phospholipid concentration, however, significant augments in the two minima intensities are observed at 2 mM of phospholipids. These results indicate that the peptide adopts well-defined helical conformations in the presence of phospholipid vesicles, however, a membrane-bound (helical) and a water-soluble (random coil) states coexist at smaller phospholipid to peptide ratios, as previously observed for other AMPs (Voievoda et al., 2015).

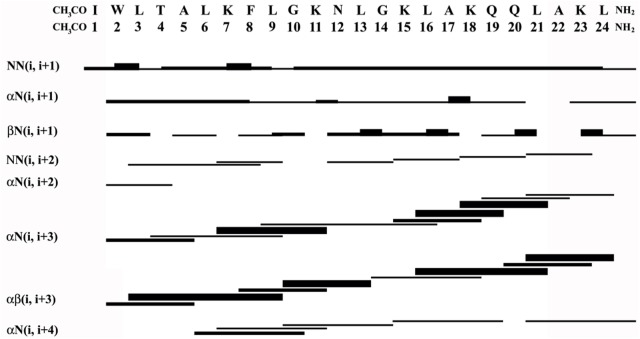

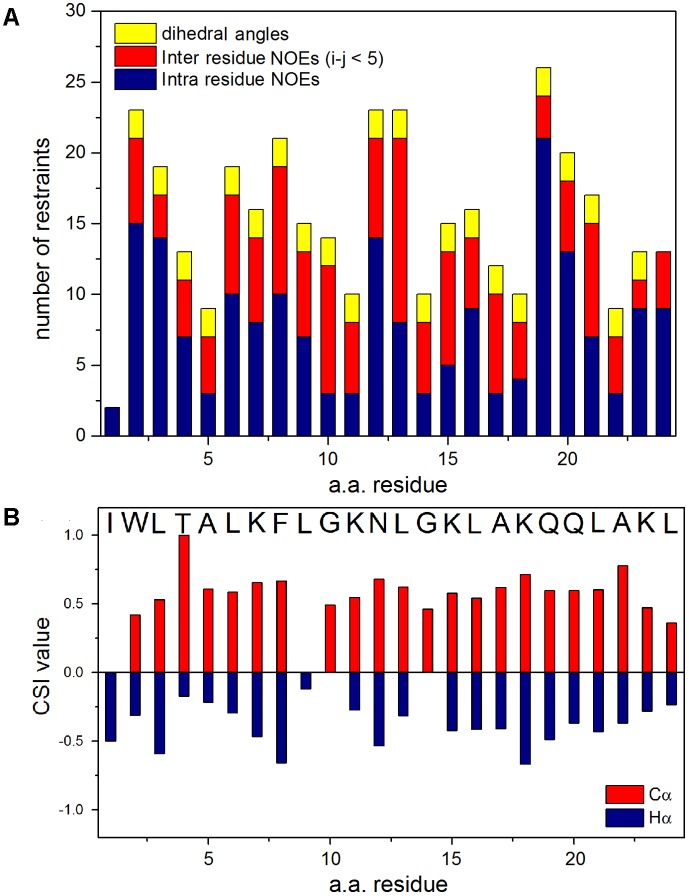

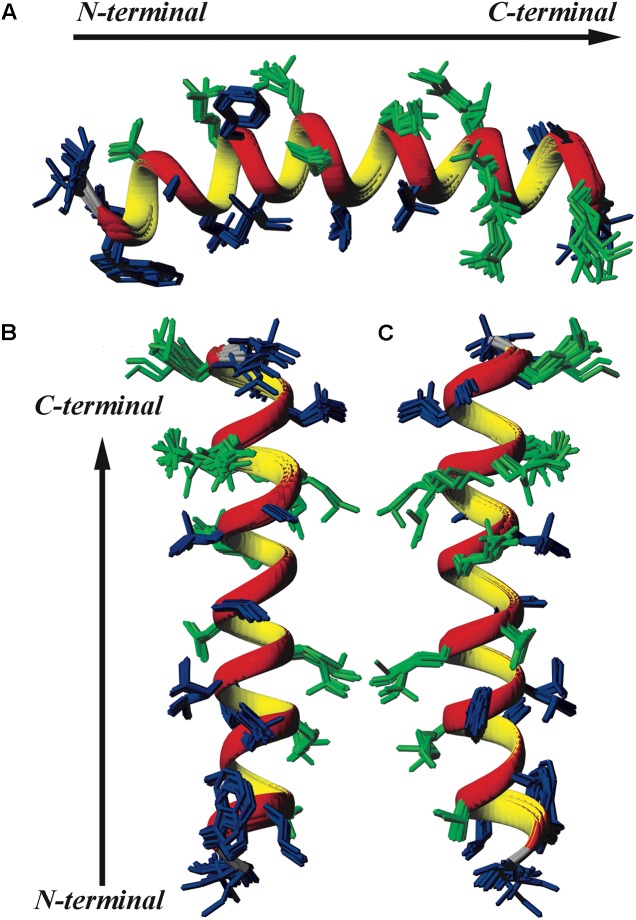

Two-Dimensional Solution NMR Spectroscopy

Sequence-specific assignments have been performed from simultaneous analysis of NMR contour maps, as previously indicated (Resende et al., 2008). The dispersion of chemical shifts observed in the 1H-15N HMQC spectrum, as well as the high number of cross-peaks detected in the NOESY contour map (Figure 3) indicate a well-folded peptide conformation. Figure 4 presents the summary of through-space correlations that characterize peptide secondary structure, obtained from NOESY. In accordance with the data obtained from CD spectroscopy at similar conditions, several NN (i, i+1), αN (i, i+3), αβ (i, i+3) and αN (i, i+4) connections indicate that the peptide presents a well-defined helical segment from Trp-2 to the last amino acid residue, including the C-terminal carboxamide, which is involved in an αN (i, i+4) interaction. The distribution of distance and dihedral angle restraints per residue are presented in Figure 5A. This trend of α-helix secondary structure is also confirmed by the Hα and Cα chemical shift indexes (CSI) (Wishart et al., 1992; Tremblay et al., 2010), as presented in the Figure 5B. Figure 6 presents the overlap of the 10 most stable structures obtained after simulated annealing protocol. This set of structures showed RMSD values of 0.98 and 0.46 Å for the superposition of all heavy and of the backbone atoms, respectively, and all of the ϕ and ψ angular pairs are located in the most favorable regions of the Ramachandran Plot (data from PROCHECK NMR), indicating the good quality of the structural model obtained.

FIGURE 3.

(A) 1H-15N HMQC spectrum and (B) amide-amide region of the NOESY spectrum of LyeTxI-b at 2.0 mM in TFE-d2:H2O (40:60) – pH 7.0 (phosphate buffer), 20.0°C.

FIGURE 4.

Graphical summary of NOE correlations characteristic of helical structures observed in the NOESY spectrum of LyeTxI-b.

FIGURE 5.

(A) Distribution of distance and dihedral angle restraints per residue used in the structural calculations for LyeTx-b peptide. Number of intra-residue NOE restraints is shown in blue, the number of inter-residue NOE restraints (i–j < 5) are shown in red and the number of dihedral angle restraints in yellow. (B) Values of Chemical-Shift Index (CSI) derived from the Cα (red) and Hα (blue) resonances.

FIGURE 6.

Superposition of the 10 lowest energy structures of LyeTxI-b. Hydrophilic residues are shown in green and hydrophobic residues in dark blue. (A) Represents a horizontal perspective of the peptide helix, whereas (B) highlights a face of the helix composed mostly of hydrophobic residues and (C) a face composed mostly of hydrophilic and charged residues.

Similarly to LyeTxI (Santos et al., 2010), LyeTxI-b α-helix does not show a clear partition between hydrophobic and hydrophilic faces, which is observed for many other antibiotic peptides, such as phylloseptins and dermadistinctin K (Resende et al., 2008; Verly et al., 2009). However, LyeTxI-b presents a higher structural stability near the N-terminus when compared to the native peptide LyeTxI, since LyeTxI-b helix is defined by a greater number of medium-range NOEs near the N-terminus, especially medium and strong-intensity αβ (i, i+3) correlations. The higher structural stability near LyeTxI-b N-terminus is certainly related to the terminal amine acetylation, which eliminates the positive charge and stabilizes the positive end of the helix dipole. The acetylation also allows extra hydrogen bond interactions involving the acetyl carbonyl group and the amidic hydrogens near N-terminus. Extra hydrogen bonds interactions, as well as helix dipole neutralization properties due to either C-terminal carboxyamidation or N-terminus acetylation, are known to promote structural stability in helical segments (Resende et al., 2008; Zanin et al., 2016). An interesting feature observed for the LyeTxI-b structure is a helix curvature (Figure 3A), which is correlated to the NN (i, i+2) NOE correlations involving several residues of the helical segment. This sort of NOEs was observed for the native peptide with a minor proportion, inducing a less pronounced curvature of the peptide helix (Santos et al., 2010).

Another example of an AMP that does not show an amphipathic partition is the Htr-M, in which a lysine residue represents a discontinuity within the helix hydrophobic face. This discontinuity has an important structural role in the homodimeric peptide homotarsinin (Htr), since the positively charged side chain of this lysine residue interacts with a negatively charged aspartate residue and a hydrophilic serine residue of the other peptide chain. These electrostatic interactions are important to stabilize the homodimer coiled coil three-dimensional structure (Verly et al., 2017).

Antimicrobial Activity in Planktonic Culture

LyeTxI-b showed a potent antimicrobial inhibition activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative planktonic bacteria under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Table 1). We observed that LyeTxI-b was exceptionally active against E. coli and S. aureus. The MBC values were the same as those obtained for MIC in all tests. The topic antibiotic chlorhexidine acetate was used as a positive control.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of LyeTxI-b and chlorhexidine acetate.

|

E. coli |

S. aureus |

A. actinomycetemcomitans |

S. sanguinis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| Compound | μmol.L-1 | μmol.L-1 | μmol.L-1 | μmol.L-1 | μmol.L-1 | μmol.L-1 | μmol.L-1 | μmol.L-1 |

| LyeTxI | 7.81∗∗ | – | – | – | 10.6∗ | 20.12∗ | 10.9∗∗∗ | 21.8∗∗∗ |

| LyeTxI-b | 0.71 | 0.71 | 2.85 | 2.85 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Chlorhexidine acetate | 125 | – | 31 | – | 125 | – | 62.5 | – |

Data of LyeTxI were obtained from (Consuegra et al., 2013) ∗; (Santos et al., 2010) ∗∗; (Cruz Olivo et al., 2017) ∗∗∗ and correspond to the same strain references used to LyeTxI-b.

The MIC value of LyeTxI-b for E. coli was 10-fold higher when compared to that of the LyeTxI peptide (Santos et al., 2010). On the other hand, the activity of LyeTxI-b for S. aureus was similar to the previously observed for the native peptide (Santos et al., 2010). Moreover, LyeTxI-b was able to decreased around 50% of MBC but with similar MIC in A. actinomycetemcomitans, when compared to the original peptide in the work of Consuegra et al. (2013). It is known that the lipid composition of the plasma membrane considerably affects the action of AMPs (to review Malanovic and Lohner, 2016; Malmsten, 2016). Gram-negative bacteria, in their majority, present a higher concentration of the zwitterionic lipid phosphatidylethanolamine when compared with Gram-positive bacteria (Epand and Epand, 2011).

In general, LyeTxI-b has antimicrobial activity at μmol concentrations, similarly to previously described AMPs, such as magainins, LL-37 and others (Park et al., 2009; Joshi et al., 2010; Brogden and Brogden, 2011; Haisma et al., 2014; Ageitos et al., 2017).

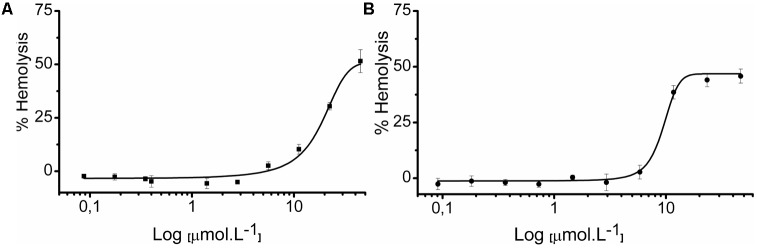

Hemolytic Assays

Our group previously demonstrated the hemolytic capacity of LyeTxI, with an ED50 of 130 μM on rabbit erythrocytes (Santos et al., 2010). Therefore, we also tested the hemolytic activity of LyeTxI-b, to evaluate if the loss of an amino acid residue and the N-terminus acetylation would modify this property. In this work, we performed the assay on lamb erythrocytes, for both peptides. As shown in Figure 7, LyeTxI had an ED50 value of 42.54 μmol.L-1, while LyeTxI-b showed approximately 46.83% of hemolysis at 46.6 μmol.L-1. This result indicates a slight increase in LyeTxI-b activity on eukaryotic cells, which is not significant, considering its 10-fold increase in bactericidal capacity for E. coli. Moreover, we observed a high level of hemolysis for LyeTxI in lamb erythrocytes, when compared to rabbits. It is known that mammalian species differ in their erythrocyte susceptibility, and lamb erythrocytes have been considered more fragile than those from rabbit (Matsuzawa and Ikarashi, 1979). In addition, it may be pointed out that in recent results obtained by our group (not shown) LyTxI-b showed only mild cytotoxicity against lung and kidney normal cell lines (Abdel-Salam et al., work in submission).

FIGURE 7.

Hemolytic activity of LyeTxI and LyeTxI-b. Lamb erythrocytes suspended in PBS were incubated for 1 h with increasing concentrations from 0.35 to 44.8 μmol.L-1 and 0.36 to 46.8 μmol.L-1, of (A) LyeTxI and (B) LyeTxI-b, respectively. The control of 100% of cell lysis was considered by hemoglobin release in the presence of Triton X-100 (1% by volume). Hemoglobin release was measured at 405 nm. ED50: LyeTxI = 42.54 μmol.L-1 while LyeTxI-b at 46.8 μmol.L-1 had 46.83% of hemolysis.

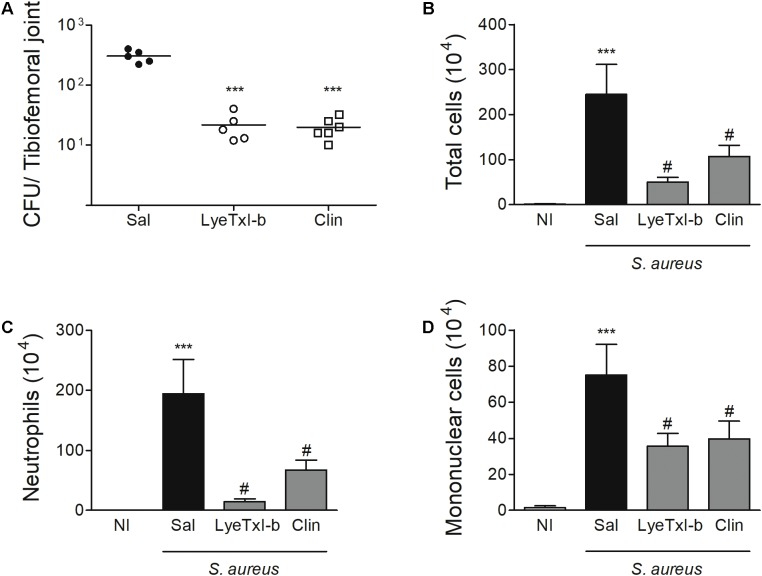

LyeTxI-b Controls Bacterial Growth and Tissue Inflammation in Vivo

Considering our positive results regarding LyeTxI-b activity in the MIC assay, we evaluated the effectiveness of this peptide in a model of S. aureus-induced arthritis in mice (Boff et al., 2018). Initially, we determined the MIC for S. aureus ATCC 6538, since the strain used in this model was different from the previous MIC assay. The MIC value for LyeTxI-b was 2.85 μmol.L-1, while for clindamycin it was 367 μmol.L-1 (control). It is noteworthy that in the growth inhibition tests we used 105 CFU.mL-1 while the SA model was established with 107 CFU.mL-1. Therefore, the MIC concentrations used was two-fold higher for the in vivo test. Thus, for each 10 μL injection in treatment models, 80 ng of LyeTxI-b and 3120 μg of clindamycin were applied.

Staphylococcus aureus-induced joint inflammation is associated with a massive recruitment of neutrophils to the joint that, together with the presence of bacteria, cause articular damage and pain (Mathews et al., 2010). In this model, a high concentration of bacteria can be detected in the joint 7 days after the challenge, and the treatment with LyeTxI-b reduced this number (Figure 8A). Furthermore, LyeTxI-b reduces cell accumulation in S. aureus-challenged joint, including the number of total cells, neutrophils and mononuclear cells (Figures 8B–D). Therefore, we can speculate that both treatments, using LyeTxI-b and clindamycin, were able to decrease the pain symptom, since the pain process can be associated with the mediators released by neutrophils (Sachs et al., 2011), as well as the direct activation of nociceptors by S. aureus (Chiu et al., 2013). It is worth mentioning that the treatment with the peptide decreased the bacterial load to the same level as the antibiotic treatment, not showing significant difference between the groups in the experimental model of SA. However, the therapeutic concentration of our peptide was more than two hundred lower (0.03 nmol) compared to that of the antibiotic (7 nmol), indicating its higher potency.

FIGURE 8.

LyeTxI-b decreases bacteria load and cellular recruitment to the joint. The arthritis was induced by intra-articular injection of S. aureus (107 CFU/10 μL) in mice. The treatment with LyeTxI-b (0.03 nmol) and clindamycin, Clin (7 nmol) by ipsilateral joint injection was performed every other day, starting on day 1, after arthritis induction. The analyses were performed 7 days after S. aureus injection for (A) bacterial load in whole joint and, (B) total cells, (C) neutrophils and (D) mononuclear cells accumulated into the joint cavity. ∗∗∗p < 0.05 compared to non-infected mice; #p < 0.05 compared to saline-treated infected mice. n = 6–8 mice per group. CFU, colony-forming unit (definir); Sal, saline; NI, non-infected mice.

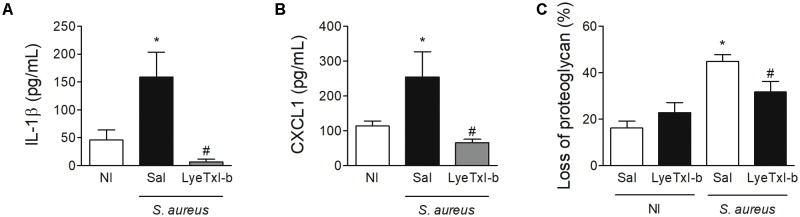

Similarly, the treatment with LyeTxI-b and clindamycin also reduced the level of IL-1β pro-inflammatory cytokine and CXCL1chemokine in the joint, when compared to non-treated joints (Figures 9A,B). IL-1β has been shown as an important factor in the pathogenesis of septic arthritis in an experimental model of intravenous injection (Hultgren et al., 2002) and CXCL1 is essential for the recruitment of neutrophils (Lira et al., 1994). Another important characteristic of septic arthritis is tissue damage. Here, the injection of S. aureus caused an important loss of proteoglycans on articular cartilages while the treatment with LyeTxI-b preserved the integrity of the joint (Figure 9C). Importantly, the injection of LyeTxI-b in naïve joint did not cause tissue inflammation.

FIGURE 9.

LyeTxI-b treatment decreased S. aureus-induced joint inflammation. After arthritis induction by intra-articular injection of S. aureus (107 CFU/10 μL) in mice, the animals were treated with LyeTxI-b (0.03 nmol) and clindamycin (7 nmol) by ipsilateral joint injection every other day. Seven days after S. aureus injection, the levels of (A) IL-1β and (B) CXCL1 in periarticular tissue were measured by ELISA while the loss of proteoglycan was determined by toluidine blue stain (C). ∗p < 0.05 compared to non-infected mice; #p < 0.05 compared to saline-treated infected mice. N = 6–8 mice per group, NI, non-infected mice.

Our results show that LyeTxI-b-treated mice present decreased bacteria load and inflammation in the joint similar to clindamycin but in different concentration, as mentioned above. Since the presence of bacteria in a joint is sufficient to stimulate resident cells to produce pro-inflammatory mediators and cell recruitment, the reduced number of bacteria in LyeTxI-b-treated group could be enough to reduce all other inflammatory markers, as observed in Figures 8, 9. Thus, we questioned whether LyeTxI-b could have a direct role in the reduction of joint inflammation, independently on its bactericidal/bacteriostatic property. To answer this question, we used an experimental model of immunization-induced arthritis (without infection – AIA model). The treatment with LyeTxI-b did not alter the recruitment of neutrophils to the joint, which are important markers of tissue inflammation in this model (AIA: 146.08 ± 15.87 – n = 5, AIA + LyeTxI_b: 162.28 ± 12.71 – n = 6; mean ± SEM). Thus, this result showed a non-direct role of LyeTxI-b on joint inflammation, and the reduction of S. aureus-induced arthritis seems to be caused by the control of bacterial growth in the joint. In sum, the ability of LyeTxI-b to control bacterial growth in the joint is sufficient to reduce the main inflammatory markers of SA model. In addition, preliminary nociceptive assays using an electronic version of von Frey test with LyeTxI-b in mice did not show any effect (data not shown).

Since the treatment of SA patients mostly involves use of antibiotics and considering that an increased number of patients infected with bacteria are resistant to antibiotics, the development of new therapeutic options became essential for a better control of infection and tissue damage (Weston et al., 1999; Sharff et al., 2013). Thus, LyeTxI-b is a prominent model for the development of new antibiotics.

Conclusion

In the present work, we characterized LyeTxI-b, a peptide derived from the spider toxin LyeTxI, with two modifications: removal of a single amino acid residue and N-terminus acetylation. We show that these small alterations are able to improve the antibiotic activity of the peptide. This is also observed in the organisms under study, i.e., different strains of the same microorganism or different species may have different susceptibilities to the drug. Therefore, our results contribute to the emerging area of antibiotics derived from AMPs, as a new alternative for the treatment of infections that are resistant to conventional drugs.

Author Contributions

PR synthesized and purified the peptide and performed MALDI-TOF and CD analyses. RV and JR performed the NMR experiments and analyzed the CD and NMR data. PR and MC investigated the study on MIC. PR and MM-B investigated the study on hemolysis. DB and FA investigated the study on in vivo model. PR and MdL wrote the original draft. PR, MM-B, MC, AP, FA, JR, and MdL wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. MdL envisioned the concept. DS, AP, and MdL supervised the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- AMPs

antimicrobial peptides

- BHI

brain heart infusion

- CD

circular dichroism

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- CHCA

α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid

- Clin

clindamycin

- CXCL1

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1

- DMF

N,N-dimethyl-formamide

- ED50

effective dose 50

- 1H-15N HMQC

1H-15N heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence

- 1H-13C HSQC

1H-13C Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence

- Htr

homodimeric peptide homotarsinin

- Htr-M

homotarsinin monomeric chain

- IL-1β

interleukin 1 beta

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NOESY

nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy

- MALDI-TOF/TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization – time of flight

- MBC

minimal bactericidal concentration

- mBSA

methylated bovine serum albumin

- MH

Mueller-Hinton

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylglycerol

- RP-HPLC

reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- TFE-d2

2,2,2-trifluoroethanol-1,1-d2

- TOCSY

total correlation spectroscopy

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), and Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia em Toxinas (INCTTOX).

References

- Ageitos J. M., Sánchez-Pérez A., Calo-Mata P., Villa T. G. (2017). Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): ancient compounds that represent novel weapons in the fight against bacteria. Biochem. Pharmacol. 133 117–138. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral F. A., Boff D., Teixeira M. M. (2016). In Vivo models to study chemokine biology. Methods Enzymol. 570 261–280. 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson D. I., Hughes D., Kubicek-Sutherland J. Z. (2016). Mechanisms and consequences of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Drug Resist. Updat. 26 43–57. 10.1016/j.drup.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim S., McDowell D., Cartagena A., Rodriguez R., Laughlin T. F., Ahmad Z. (2016). Venom peptides cathelicidin and lycotoxin cause strong inhibition of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 87 246–251. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.02.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax A., Davis D. G. (1985). MLEV-17-based two-dimensional homonuclear magnetization transfer spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 65 355–360. 10.1016/0022-2364(85)90018-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bechinger B., Gorr S. U. (2017). Antimicrobial peptides: mechanisms of action and resistance. J. Dent. Res. 96 254–260. 10.1177/0022034516679973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boff D., Oliveira V. L. S., Queiroz Junior C. M., Silva T. A., Allegretti M., Verri W. A., Jr., et al. (2018). CXCR2 is critical for bacterial control and development of joint damage and pain in Staphylococcus aureus-induced septic arthritis in mouse. Eur. J. Immunol. 48 454–463. 10.1002/eji.201747198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogden K. A. (2005). Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3 238–250. 10.1038/nrmicro1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogden N. K., Brogden K. A. (2011). Will new generations of modified antimicrobial peptides improve their potential as pharmaceuticals? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38 217–225. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulet P., Hetru C., Dimarcq J. L., Hoffmann D. (1999). Antimicrobial peptides in insects; structure and function. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 23 329–344. 10.1016/S0145-305X(99)00015-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W. C., White P. D. (2000). Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis: A Practical Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu I. M., Heesters B. A., Ghasemlou N., Von Hehn C. A., Zhao F., Tran J., et al. (2013). Bacteria activate sensory neurons that modulate pain and inflammation. Nature 501 52–57. 10.1038/nature12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consuegra J., de Lima M. E., Santos D., Sinisterra R. D., Cortés M. E. (2013). Peptides: β-cyclodextrin inclusion compounds as highly effective antimicrobial and anti-epithelial proliferation agents. J. Periodontol. 84 1858–1868. 10.1902/jop.2013.120679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Olivo E. A., Santos D., de Lima M. E., Dos Santos V. L., Sinisterra R. D., Cortes M. E. (2017). Antibacterial effect of synthetic peptide LyeTxI and LyeTxI/beta-Cyclodextrin association compound against planktonic and multispecies biofilms of periodontal pathogens. J. Periodontol. 88 e88–e96. 10.1902/jop.2016.160438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta A., Ghosh A., Airoldi C., Sperandeo P., Mroue K. H., Jimenez-Barbero J., et al. (2015). Antimicrobial peptides: insights into membrane permeabilization, lipopolysaccharide fragmentation and application in plant disease control. Sci. Rep. 5:11951. 10.1038/srep11951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson R. M., Liu C. Q. (2008). Properties and applications of antimicrobial peptides in biodefense against biological warfare threat agents. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 34 89–107. 10.1080/10408410802143808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Nunez C., Cardoso M. H., de Souza Candido E., Franco O. L., Hancock R. E. (2016). Synthetic antibiofilm peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858 1061–1069. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Nunez C., Reffuveille F., Fernandez L., Hancock R. E. (2013). Bacterial biofilm development as a multicellular adaptation: antibiotic resistance and new therapeutic strategies. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16 580–589. 10.1016/j.mib.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995). NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. 10.1007/BF00197809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson A. J., Purves J., Kamysz W., Rolff J. (2013). Comparing selection on S. aureus between antimicrobial peptides and common antibiotics. PLoS One 8:e76521. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand R. M., Epand R. F. (2011). Bacterial membrane lipids in the action of antimicrobial agents. J. Pept. Sci. 17 298–305. 10.1002/psc.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gast K., Siemer A., Zirwer D., Damaschun G. (2001). Fluoroalcohol-induced structural changes of proteins: some aspects of cosolvent-protein interactions. Eur. Biophys. J. 30 273–283. 10.1007/s002490100148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A., Kar R. K., Jana J., Saha A., Jana B., Krishnamoorthy J., et al. (2014). Indolicidin targets duplex DNA: structural and mechanistic insight through a combination of spectroscopy and microscopy. ChemMedChem 9 2052–2058. 10.1002/cmdc.201402215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusmao K. A. G., Dos Santos D. M., Santos V. M., Cortes M. E., Reis P. V. M., Santos V. L., et al. (2017). Ocellatin peptides from the skin secretion of the South American frog Leptodactylus labyrinthicus (Leptodactylidae): characterization, antimicrobial activities and membrane interactions. J. Venom Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 23:4. 10.1186/s40409-017-0094-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisma E. M., de Breij A., Chan H., van Dissel J. T., Drijfhout J. W., Hiemstra P. S., et al. (2014). LL-37-derived peptides eradicate multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from thermally wounded human skin equivalents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 4411–4419. 10.1128/AAC.02554-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultgren O. H., Svensson L., Tarkowski A. (2002). Critical role of signaling through IL-1 receptor for development of arthritis and sepsis during Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Immunol. 168 5207–5212. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyberts S. G., Goldberg M. S., Havel T. F., Wagner G. (1992). The solution structure of eglin c based on measurements of many NOEs and coupling constants and its comparison with X-ray structures. Protein Sci. 1 736–751. 10.1002/pro.5560010606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen H., Hamill P., Hancock R. E. (2006). Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19 491–511. 10.1128/CMR.00056-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. A., Blevins R. A. (1994). NMR View: a computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR 4 603–614. 10.1007/BF00404272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S., Bisht G. S., Rawat D. S., Kumar A., Kumar R., Maiti S., et al. (2010). Interaction studies of novel cell selective antimicrobial peptides with model membranes and E. coli ATCC 11775. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798 1864–1875. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi R., Billeter M., Wüthrich K. (1996). MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14 51–55. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Ernst R. R., Wuthrich K. (1980). A two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser enhancement (2D NOE) experiment for the elucidation of complete proton-proton cross-relaxation networks in biological macromolecules. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 95 1–6. 10.1016/0006-291X(80)90695-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuprin S., Graslund A., Ehrenberg A., Koch M. H. (1995). Nonideality of water-hexafluoropropanol mixtures as studied by X-ray small angle scattering. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 217 1151–1156. 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A., Rullmannn J. A., MacArthur M. W., Kaptein R., Thornton J. M. (1996). AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8 477–486. 10.1007/BF00228148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lira S. A., Zalamea P., Heinrich J. N., Fuentes M. E., Carrasco D., Lewin A. C., et al. (1994). Expression of the chemokine N51/KC in the thymus and epidermis of transgenic mice results in marked infiltration of a single class of inflammatory cells. J. Exp. Med. 180 2039–2048. 10.1084/jem.180.6.2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malanovic N., Lohner K. (2016). Gram-positive bacterial cell envelopes: the impact on the activity of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858 936–946. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmsten M. (2016). Interactions of antimicrobial peptides with bacterial membranes and membrane components. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 16 16–24. 10.2174/1568026615666150703121518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews C. J., Weston V. C., Jones A., Field M., Coakley G. (2010). Bacterial septic arthritis in adults. Lancet 375 846–855. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61595-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa T., Ikarashi Y. (1979). Haemolysis of various mammalian erythrocytes in sodium chloride, glucose and phosphate-buffer solutions. Lab. Anim. 13 329–331. 10.1258/002367779780943297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mookherjee N., Hancock R. E. (2007). Cationic host defence peptides: innate immune regulatory peptides as a novel approach for treating infections. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64 922–933. 10.1007/s00018-007-6475-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizet V. (2006). Antimicrobial peptide resistance mechanisms of human bacterial pathogens. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 8 11–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Othon C. M., Kwon O. H., Lin M. M., Zewail A. H. (2009). Solvation in protein (un)folding of melittin tetramer-monomer transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 12593–12598. 10.1073/pnas.0905967106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overhage J., Campisano A., Bains M., Torfs E. C., Rehm B. H., Hancock R. E. (2008). Human host defense peptide LL-37 prevents bacterial biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 76 4176–4182. 10.1128/IAI.00318-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. H., Nan Y. H., Park Y., Kim J. I., Park I. S., Hahm K. S., et al. (2009). Cell specificity, anti-inflammatory activity, and plausible bactericidal mechanism of designed Trp-rich model antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788 1193–1203. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resende J. M., Moraes C. M., Prates M. V., Cesar A., Almeida F. C., Mundim N. C., et al. (2008). Solution NMR structures of the antimicrobial peptides phylloseptin-1, -2, and -3 and biological activity: the role of charges and hydrogen bonding interactions in stabilizing helix conformations. Peptides 29 1633–1644. 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs D., Coelho F. M., Costa V. V., Lopes F., Pinho V., Amaral F. A., et al. (2011). Cooperative role of tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β and neutrophils in a novel behavioural model that concomitantly demonstrates articular inflammation and hypernociception in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 162 72–83. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00895.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos D. M., Reis P. V., Pimenta A. M. C. (2016). “Antimicrobial peptides in spider venoms,” in Spider Venoms, eds Gopalakrishnakone P., Corzo G. A., de Lima M. E., Diego-García E. (Dordrecht: Springer; ), 361–377. [Google Scholar]

- Santos D. M., Verly R. M., Piló-Veloso D., de Maria M., de Carvalho M. A., Cisalpino P. S., et al. (2010). LyeTx I, a potent antimicrobial peptide from the venom of the spider Lycosa erythrognatha. Amino Acids 39 135–144. 10.1007/s00726-009-0385-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanda P., Brutscher B. (2005). Very fast two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy for real-time investigation of dynamic events in proteins on the time scale of seconds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 8014–8015. 10.1021/ja051306e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieters C. D., Kuszewski J. J., Tjandra N., Clore G. M. (2003). The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 160 65–73. 10.1016/S1090-7807(02)00014-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharff K. A., Richards E. P., Townes J. M. (2013). Clinical management of septic arthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 15:332. 10.1007/s11926-013-0332-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. (2009). TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR 44 213–223. 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay M. L., Banks A. W., Rainey J. K. (2010). The predictive accuracy of secondary chemical shifts is more affected by protein secondary structure than solvent environment. J. Biomol. NMR 46 257–270. 10.1007/s10858-010-9400-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urech D. M., Feige U., Ewert S., Schlosser V., Ottiger M., Polzer K., et al. (2010). Anti-inflammatory and cartilage-protecting effects of an intra-articularly injected anti-TNF{alpha} single-chain Fv antibody (ESBA105) designed for local therapeutic use. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69 443–449. 10.1136/ard.2008.105775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verly R. M., de Moraes C. M., Resende J. M., Aisenbrey C., Bemquerer M. P., Piló-Veloso D., et al. (2009). Structure and membrane interactions of the antibiotic peptide dermadistinctin K by multidimensional solution and oriented 15N and 31P solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 96 2194–2203. 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verly R. M., Resende J. M., Junior E. F., de Magalhaes M. T., Guimaraes C. F., Munhoz V. H., et al. (2017). Structure and membrane interactions of the homodimeric antibiotic peptide homotarsinin. Sci. Rep. 7:40854. 10.1038/srep40854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voievoda N., Schulthess T., Bechinger B., Seelig J. (2015). Thermodynamic and biophysical analysis of the membrane-association of a histidine-rich peptide with efficient antimicrobial and transfection activities. J. Phys. Chem. B 119 9678–9687. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b04543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Epand R. F., Mishra B., Lushnikova T., Thomas V. C., Bayles K. W., et al. (2012). Decoding the functional roles of cationic side chains of the major antimicrobial region of human cathelicidin LL-37. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 845–856. 10.1128/AAC.05637-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston V. C., Jones A. C., Bradbury N., Fawthrop F., Doherty M. (1999). Clinical features and outcome of septic arthritis in a single UK Health District 1982-1991. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 58 214–219. 10.1136/ard.58.4.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2014). Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand I., Hilpert K., Hancock R. E. (2008). Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 3 163–175. 10.1038/nprot.2007.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willker W., Leibfritz D., Kerssebaum R., Bermel W. (1993). Gradient selection in inverse heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Chem. 31 287–292. 10.1002/mrc.1260310315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D., Richards F. M. (1992). The chemical shift index: a fast and simple method for the assignment of protein secondary structure through NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 31 1647–1651. 10.1021/bi00121a010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Harroun T. A., Weiss T. M., Ding L., Huang H. W. (2001). Barrel-stave model or toroidal model? A case study on melittin pores. Biophys. J. 81 1475–1485. 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75802-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanin L. P., de Araujo A. S., Juliano M. A., Casella T., Nogueira M. C., Ruggiero Neto J. (2016). Effects of N-terminus modifications on the conformation and permeation activities of the synthetic peptide L1A. Amino Acids 48 1433–1444. 10.1007/s00726-016-2196-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]