Abstract

The remarkable site-selectivity and broad substrate scope of flavin dependent halogenases (FDHs) has led to much interest in their potential as biocatalysts. Multiple engineering efforts have demonstrated that FDHs can be tuned for non-native substrate scope and site-selectivity. FDHs have also proven useful as in vivo biocatalysts and have been successfully incorporated into biosynthetic pathways to build new chlorinated aromatic compounds in several heterologous organisms. In both cases, reduced flavin cofactor, usually supplied by a separate flavin reductase (FR), is required. Here, we report functional synthetic, fused FDH-FR proteins, containing various FDHs and FRs, joined by different linkers. We show that FDH-FR fusion proteins can increase product titers compared to the individual components for in vivo biocatalysis in E. coli.

Introduction

Halogenated aromatic compounds often exhibit unique biological activities and are thus commonly used as pharmaceutical drugs and agrochemicals.1 Aryl halides are also valuable building blocks for synthetic chemistry, particularly due to their centrality to a range of powerful cross-coupling reactions.2 Despite the importance of aromatic halogenation, however, common methods of aromatic halogenation, perhaps most notably electrophilic aromatic substitution, often suffer from poor regioselectivity.3 More recent efforts have therefore explored the ability of directed groups to enable selective halogenation of proximal C-H bonds on suitably pre-functionalized substrates.4,5

Complementing these traditional synthetic methods, flavin-dependent halogenases (FDHs) have been shown to halogenate a range of electron rich hetero(arenes) with high selectivity (Fig. 1).6 FDH catalysis proceeds via an electrophilic halogen species (both a lysine-derived haloamine7 and HOX8 have been proposed), which, due to its orientation relative to bound substrate, can override electronic biases of different substrates to catalyze aromatic halogenation with novel regioselectivity.9,10 Notably, FDH catalysis proceeds in aqueous solution at ambient temperature and requires only reduced flavin cofactor (FADH2), sodium chloride as a halide source, and oxygen from air as a terminal oxidant. A cofactor regeneration system (CRS) comprised of a flavin reductase, a NAD(P) oxidoreductase (e.g. glucose dehydrogenase), FAD, NAD(P), and a terminal reductant (e.g. glucose, the only stoichiometric reagent in the CRS) can be used to supply FADH2.

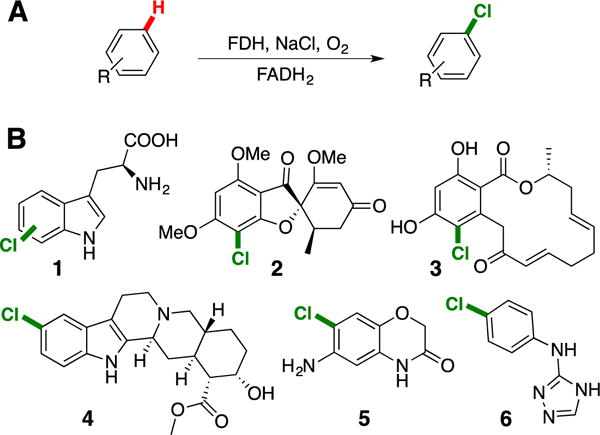

Figure 1.

A) General scheme for halogenation by FDHs. B) Representative products from halogenation of native (1-3) and non-native FDH substrates (4-6).11–14

A number of efforts involving directed evolution and targeted mutagenesis have been used to engineer FDH variants with increased stability,15,16 expanded substrate scope,13,17 and altered regioselectivity14,18. In all of these efforts, a CRS analogous to that described above was used to ensure maximum product formation, which necessitates the purification of a suitable flavin reductase. Typically, E. coli flavin reductase, Fre, or the native RebH partner RebF have been used for in vitro halogenation assays.17 Due to low solubility of RebF when over-expressed in E. coli, a fusion of maltose binding protein and RebF (MBPF) is often used in place of RebF.19 The requirement of flavin reductase (FR) can be tedious for directed evolution efforts, since sufficient reductase for thousands of reactions must be regularly prepared, purified, and quality tested. Of course, this requirement could be eliminated by co-(over)expressing genes for the reductase and halogenase either individually or as fusions. Genetic fusion of the flavin reductase and halogenase could also improve halogenation efficiency, particularly for in vivo applications where a high local concentration of reduced FADH2 cannot necessarily be guaranteed.

The utility of in vivo FDH catalyzed halogenation has now been established in a number of different organisms.12,20–22 For example, Rdc2 has been used to halogenate phenolic compounds in E. coli without co-expressing a flavin reductase, since this organism contains naturally occurring flavin reductases.12,23 Likewise, targeting FDH expression to plant chloroplasts (which have high levels of FADH2) is sufficient to enable FDH catalysis in planta, but co-expression of a reductase is required if cytosolic expression is desired.22 Regardless of whether endogenous reductases may be able to supply FADH2, many studies have shown that increasing the local concentration of enzymes can increase flux through multistep enzymatic pathways.24,25 Previous work has demonstrated that Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases can be genetically fused with NADP+ reductases, simplifying cofactor regeneration.26 Ferrodoxin and flavodoxin reductase type domains can also be fused to cytochrome P450 heme domains to generate self-sufficient hydroxylation catalysts.27–31 We therefore envisioned that an FDH-FR fusion enzyme could be useful for a wide range of in vitro and in vivo applications.

In vitro Characterization of FDH-FR Fusion Enzymes

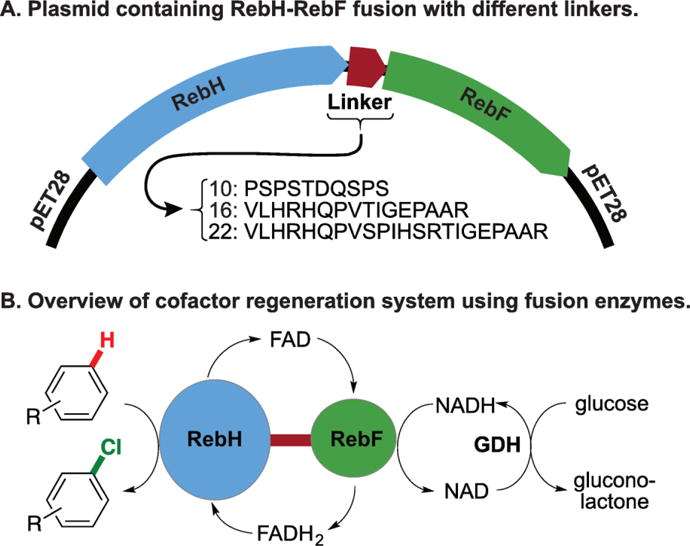

To test the feasibility of developing soluble, functional FDH-FR fusion enzymes, we genetically fused the genes encoding wild-type RebH and RebF using three linkers based on sequences used to create the functional P450-reductase fusions noted above.30,31 These linkers consisted of 10, 16, and 22 amino acid residues (Figure 2A), and the corresponding fusions are referred to as H-10-F, H-16-F, and H-22-F. The fusion constructs were co-expressed with the pGro7 chaperone system in E. coli to afford 20-70 mg L−1 soluble protein following purification.

Figure 2.

A) Fusion constructs encoded on a pET28 vector. B) Overview of cofactor regeneration using fusion enzymes.

To investigate whether reductase and halogenase domains of the fused systems retained activity, we conducted halogenation reactions with L-tryptophan (Figure 2B). The yields of these reactions were compared with the yield of RebH and MBPF added as individual components. All three fusions retained substantial halogenation activity (Table 1, entries 2-4); however, lower product yields were observed relative to the individual enzymes (Table 1, entry 1). Yields were unaffected by the difference in linker length and amino acid composition between linkers 10 and 16, but the longest linker, 22, led to a lower yield. Similar steady state kinetic parameters were obtained for RebH and H-16-F (Table 2), indicating that fusion to the reductase did not significantly impact halogenase activity. The fusion enzyme has a slightly lower kcat value (1.2 vs. 1.3 min−1) and a higher Km (1.8 vs. 1.2 μM), which could account for the lower yields obtained with this enzyme. NADH oxidation was also found to occur at a similar rate as the the MBP-F construct that we typically use for in vitro bioconversions (kcat = 206 and 197 min−1, respectively).

Table 1.

Aromatic halogenation catalyzed by different FDH or FDH-FR fusions.a

| Entry | FDH | Substrate | TTN | [FDH] (μM) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RebH | 7 | 301 ± 2.3 | 1.5 | 90.3 |

| 2 | H-22-F | 7 | 128 ± 2.7 | 1.5 | 38.3 |

| 3 | H-16-F | 7 | 187 ± 11 | 1.5 | 56.2 |

| 4 | H-10-F | 7 | 182 ± 2.5 | 1.5 | 54.6 |

| 5 | H-16-Fre | 7 | 101 ± 1.5 | 1.5 | 30.3 |

| 6 | 3SS | 8 | 117 ± 0.01 | 1 | 23.4 |

| 7 | 3SS-16-F | 8 | 74 ± 4.65 | 1 | 14.8 |

| 8 | 1K | 9 | 382 ± 38 | 1 | 38.2 |

| 9 | 1K-16-F | 9 | 41 ± 11 | 1 | 4.1 |

| 10 | 10S | 10 | 11 ± 0.22 | 25 | 26.3 |

| 11 | 10S-16-F | 10 | 7 ± 0.02 | 25 | 17.3 |

0.5 mM substrate, 1.5-25 μM FDH, 9 U mL−1 GDH, 10-100 mM NaCl, 20 mM glucose, 100 μM NAD and FAD, 25 mM HEPES buffer pH = 7.4, 25 °C, 75 μL final reaction volume. 2.5 μM reductase was added to reactions that did not contain a fusion enzyme. Reactions were quenched with one volume MeOH. 0.5 mM phenol (for 7, 8, 10) or 0.5 mM benzoic acid (for 9) was added as an internal standard, and reactions were analyzed by HPLC.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for aromatic halogenation catalyzed by RebH and H-16-F.a

| FDH | kcat (min−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (min−1 μM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RebH | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.06 |

| H-16-F | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.66 |

90-160 μM L-tryptophan, 0.5 μM FDH, 0.5 μM reductase, 9 U mL−1 GDH, 10 mM NaCl, 20 mM glucose, 100 μM NAD and FAD, 25 mM HEPES buffer pH = 7.4, 25 °C, 75 μL final reaction volume. Reactions were quenched with MeOH 5-20 minutes after reaction initiation. 0.5 mM phenol was added as an internal standard, and reactions were analyzed by HPLC.

To determine if decreased stability, in addition to less favorable kinetic parameters, hinders H-16-F performance, the melting temperature (TM) was compared with that of RebH. Tm’s of 49.5 °C and 44.9 °C were obtained for RebH and H-16-F, respectively, indicating that reduced stability of the fusion could indeed be leading to lower conversions. Previously, a thermostable flavin reductase from Bacillus subtilis32 had been found compatible with FDH halogenation systems.33 With the hopes that addition of a thermostable reductase to RebH might increase the overall thermostability, thermostable Fre was fused to RebH using the 16 amino acid linker. This fusion, RebH-16-Fre, also expressed as soluble protein, but it provided a lower halogenation yield (Table 1, entry 5) and had a comparable melting temperature (TM = 45 °C) relative to H-16-F.

Three RebH variants previously engineered in our laboratory, 1K,34 3SS,13 and 10S,14 were also fused to RebF via the 16 amino acid linker described above. Soluble protein was obtained for all FDH fusions, and bioconversions were conducted with purified enzyme. As observed for H-16-F, all three FDH fusions retained activity for their respective substrates (Table 1, entries 7, 9, 11), but lower conversions were observed relative to the individual enzymes. The largest decrease in product yield was observed for 1K-16-F, a variant that contains a mutation (R231K) in the FAD-binding domain34. H-16-F, 3SS-16-F, and 10S-16-F demonstrate a 1.6-fold reduction in TTN compared to their individual components; however, 1K-16-F displays a 9-fold reduction in TTN (Table 1).

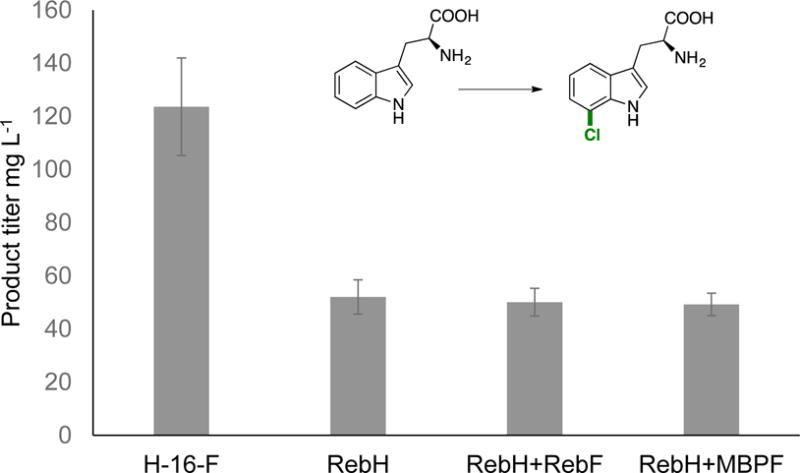

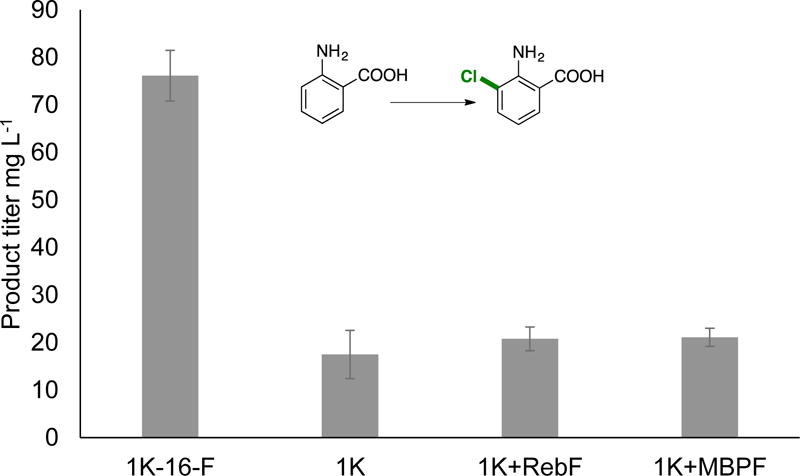

In addition to using fusion enzymes to make directed evolution efforts more facile, we also envisioned that they could provide higher product yields in whole cell bioconversions. Within a cell, the local concentration of FADH2 could greatly impact FDH activity. To test this hypothesis, cells were transformed with H-16-F, RebH, RebH+RebF, and RebH+MBPF (note that RebH+RebF and RebH+MBPF cells contain these two enzymes on two separate plasmids). L-tryptophan (7, 1 mM) and NaCl (100 mM) were added immediately after induction of expression. High titers of 7-chlorotryptophan were obtained, and a 2.5-fold increase in product concentration was observed for cells containing H-16-F relative to RebH, RebH+RebF, or RebH+MBPF (Figure 2). Excited by this result, we sought to demonstrate in vivo chlorination on a non-native substrate. Because E. coli cells contain significant quantities of L-tryptophan natively, we sought to use an FDH that does not halogenate L-tryptophan. Variant 1K was found to have greatly reduced activity on L-tryptophan, and in competition reactions between L-tryptophan and anthranilic acid (9), no conversion of tryptophan is observed (see supporting information). Even though 1K-16-F displayed a 9-fold reduced product yield relative to the single component system in vitro (Table 1), significantly higher titers (76.2 mg L−1 with 1K-16-F, 21.1 mg L−1 with 1K+MBPF) were obtained with this enzyme in vivo (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

In vivo biocatalysis with H-16-F and 1K-16-F to afford chlorinated L-tryptophan (7) and anthranilic acid (9), respectively. Upon induction of expression of 50 mL cultures in TB media, 1 mM substrate and 100 mM NaCl were added. Cultures were expressed for 24 hours at 30 °C, and aliquots of the supernatant were analyzed by HPLC. Three independent trials of triplicate cultures were performed for each cell line, and resulting standard deviations are shown as error bars (n = 9).

In summary, we have demonstrated that functional FDH-FR fusions can be obtained using different linkers, FDHs, and reductases. Although a slight reduction in activity is observed for these enzymes compared with their corresponding single component systems in vitro, the use of fusions could simplify FDH engineering efforts. In addition, higher product titers are observed when fusion FDH-FR are used for in vivo biocatalytic transformations. These could serve as valuable tools for in vivo chlorination in several different organisms.

Supplementary Material

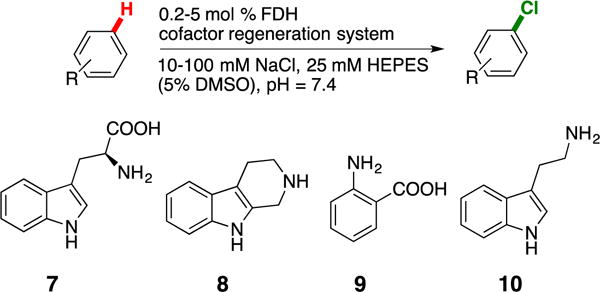

Scheme 1.

General reaction scheme for in vitro reactions on substrates 7-10.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (1R01GM115665). MCA was supported by an NSF predoctoral fellowship (DGE-1144082).

References

- 1.Jeschke P. Pest Manag Sci. 2010;66:10–27. doi: 10.1002/ps.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diederich F, Stang P. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Wiley-VCH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podgoršek A, Zupan M, Iskra J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:8424–8450. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1147–1169. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arockiam PB, Bruneau C, Dixneuf PH. Chem Rev. 2012;112:5879–5918. doi: 10.1021/cr300153j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaillancourt FH, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Walsh CT. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3364–3378. doi: 10.1021/cr050313i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeh E, Blasiak LC, Koglin A, Drennan CL, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1284–1292. doi: 10.1021/bi0621213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong C, Flecks S, Unversucht S, Haupt C, van Pée KH, Naismith JH. Science. 2005;309:2216–2219. doi: 10.1126/science.1116510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bitto E, Huang Y, Bingman CA, Singh S, Thorson JS, Phillips GN., Jr Proteins. 2007;70:289–293. doi: 10.1002/prot.21627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X, Laurentis WD, Leang K, Herrmann J, Ihlefeld K, van Pée KH, Naismith JH. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chooi YH, Cacho R, Tang Y. Chem Biol. 2010;17:483–494. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J, Zhan J. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:2119–2123. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne JT, Poor CB, Lewis JC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:4226–4230. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andorfer MC, Park HJ, Vergara-Coll J, Lewis JC. Chem Sci. 2016;7:3720–3729. doi: 10.1039/c5sc04680g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poor CB, Andorfer MC, Lewis JC. 2014;15:1286–1289. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnepel C, Minges H, Frese M, Sewald N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:14159–14163. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepherd SA, Karthikeyan C, Latham J, Struck AW, Thompson ML, Menon BRK, Styles MQ, Levy C, Leys D, Micklefield J. Chem Sci. 2015;6:3454–3460. doi: 10.1039/c5sc00913h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shepherd SA, Menon BRK, Fisk H, Struck AW, Levy C, Leys D, Micklefield J. ChemBioChem. 2016;17:821–824. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payne JT, Andorfer MC, Lewis JC. Meth Enzymol. 2016;575:93–126. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glenn WS, Nims E, O’Connor SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19346–19349. doi: 10.1021/ja2089348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Runguphan W, Qu X, O’Connor SE. Nature. 2010;468:461–464. doi: 10.1038/nature09524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fräbel S, Krischke M, Staniek A, Warzecha H. Biotechnol J. 2016;11:1586–1594. doi: 10.1002/biot.201600337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng J, Lytle AK, Gage D, Johnson SJ, Zhan J. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:1001–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dueber JE, Wu GC, Malmirchegini GR, Moon TS, Petzold CJ, Ullal AV, Prather KLJ, Keasling JD. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilner OI, Shimron S, Weizmann Y, Wang ZG, Willner I. Nano Lett. 2009;9:2040–2043. doi: 10.1021/nl900302z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torres Pazmiño DE, Snajdrova R, Baas B-J, Ghobrial M, Mihovilovic MD, Fraaije MW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:2275–2278. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robin A, Kohler V, Jones A, Ali A, Kelly PP, O’Reilly E, Turner NJ, Flitsch SL. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2011;7:1494–1498. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nodate M, Kubota M, Misawa N. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2006;71:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0147-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilardi G, Meharenna YT, Tsotsou GE. Biosensors and …. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li S, Podust LM, Sherman DH. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12940–12941. doi: 10.1021/ja075842d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belsare KD, Ruff AJ, Martinez R, Shivange AV, Mundhada H, Holtmann D, Schrader J, Schwaneberg U. BioTechniques. 2014;57:1–6. doi: 10.2144/000114187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohshiro T, Ishii Y, Matsubara T, Ueda K, Izumi Y, Kino K, Kirimura K. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;100:266–273. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menon BRK, Latham J, Dunstan MS, Brandenburger E, Klemstein U, Leys D, Karthikeyan C, Greaney MF, Shepherd SA, Micklefield J. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14:9354–9361. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01861k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belsare KD, Andorfer MC, Cardenas FS, Chael JR, Park HJ, Lewis JC. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6:416–420. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.