Abstract

Background

The Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research has studied Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) prevalence since 1998 and found a dynamic change in its prevalence in Korea. The aim of this study was to determine the recent H. pylori prevalence rate and compare it with that of previous studies according to socioeconomic variables.

Methods

We planned to enroll 4920 asymptomatic Korean adults from 21 centers according to the population distribution of seven geographic areas (Seoul, Gyeonggi, Gangwon, Chungcheong, Kyungsang, Cholla, and Jeju). We centrally collected serum and tested H. pylori serum IgG using a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay.

Results

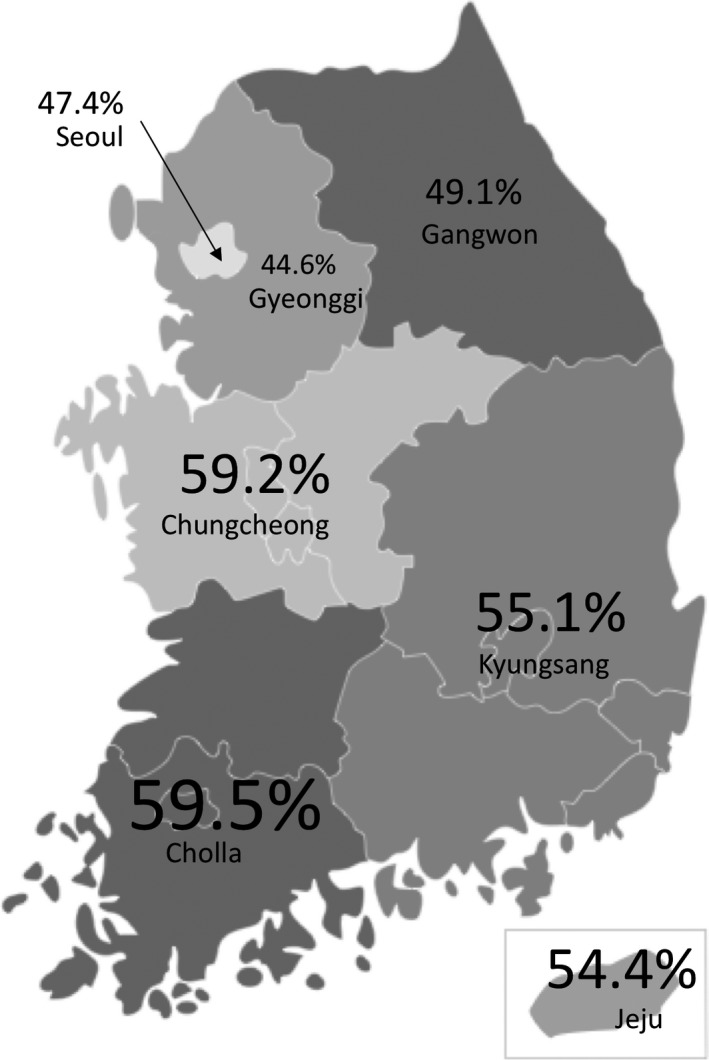

We analyzed 4917 samples (4917/4920 = 99.9%) from January 2015 to December 2016. After excluding equivocal serologic results, the H. pylori seropositivity rate was 51.0% (2414/4734). We verified a decrease in H. pylori seroprevalence compared with previous studies performed in 1998, 2005, and 2011 (P < .0001). The H. pylori seroprevalence rate differed by area: Cholla (59.5%), Chungcheong (59.2%), Kyungsang (55.1%), Jeju (54.4%), Gangwon (49.1%), Seoul (47.4%), and Gyeonggi (44.6%). The rate was higher in those older than 40 years (38.1% in those aged 30‐39 years and 57.7% in those aged 40‐49 years) and was lower in city residents than in noncity residents at all ages.

Conclusions

Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in Korea is decreasing and may vary according to population characteristics. This trend should be considered to inform H. pylori‐related policies.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Korea, prevalence

1. INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has infected more than half of the world's population1 and is an important cause of gastric cancer, mucosal‐associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and peptic ulcer disease.2 Chronic infection with H. pylori is strongly associated with gastric cancer3 the highest incidence of which is observed in Korea, Mongolia, Japan, and China.4 Eradication of H. pylori has thus been attempted in China and Japan to reduce gastric cancer levels.5, 6 Accordingly, determination of the H. pylori prevalence of normal asymptomatic participants is crucial for the establishment of national health policies in these Eastern Asia countries. Nationwide studies of H. pylori prevalence were performed in Korea in 1998, 2005, and 2011.7, 8, 9 Although these studies obtained data from a large number of participants, they had several notable limitations, such as inconsistencies in test methods, uneven study populations, and lack of socioeconomic information. Accordingly, the Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research has newly performed a nationwide H. pylori prevalence study and compared its results with those of previous studies to compensate for their defects.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

Study participants were prospectively enrolled from 21 centers in South Korea from January 2015 to December 2016. These centers are based on seven geographic areas: Seoul (3 centers), Gyeonggi (6 centers), Gangwon (2 centers), Chungcheong (2 centers), Kyungsang (4 centers), Cholla (3 centers), and Jeju province (1 center). All participants were asymptomatic Koreans older than 16 years. Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms such as dyspepsia, regurgitation, and pain or who had history of H. pylori eradication, abdominal surgery, or peptic ulcer were excluded.

Informed consent was obtained, and a questionnaire on socioeconomic status was administered by a physician or nurse. The questionnaire included family history of gastric cancer, family income, education status, and habitation pattern in preschool, school, and posthigh school periods. Family history of gastric cancer was confined to parents, siblings, and children. Family income was divided into low (<US $3000 per month), medium (US $3000‐10,000 per month), and high (>US $10,000 per month). Education status was divided into low (middle school graduate or less), medium (high school graduate or university dropout), and high (university graduate or more). We investigated two aspects of habitation status, geographic area, and type of residence in terms of city or noncity during each life period.

2.2. Serologic evaluation

All collected serum was centrally analyzed by a single company (Seegene Medical Foundation, Seoul, Korea). The Immulite 2000® H. pylori IgG system (Diagnostic Product Corporation, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used to measure anti‐H. pylori IgG. This test consists of a solid‐phase, two‐step chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of this test are reported as 91%, 100%, 100%, and 71%, respectively.10 We used only positive (≥1.10 U/mL) or negative (<0.9 U/mL) results, and equivocal results (0.9‐1.09 U/mL) were excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Statistics

A sample size of 4920 was calculated to obtain a two‐sided 95% confidence interval with a width equal to 0.028, assuming a H. pylori infection rate of 55% based on a previous study.9 We distributed participants into seven geographic areas according to the 2013 population census. Categorical variables were analyzed by the chi‐square test. Multivariable logistic regression was used for the investigation of risk factors for H. pylori seropositivity. We used the Cochran‐Armitage trend test for the comparison of H. pylori seroprevalence among the data published in 1998,7 2005,8 2011,9 and in this study. We only analyzed the results of asymptomatic participants from previous studies. A significance level of P < .05 was applied to all analyses except for multiple comparisons. We used the Bonferroni correction to calculate the P values for multiple comparisons.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Seropositivity of participants and comparison with the results from 1998, 2005, and 2011

We enrolled 4963 asymptomatic participants from 21 centers, and 4917 samples were found to be suitable for the H. pylori IgG test (Figure 1). Among these, 183 samples showed equivocal results. Thus, we acquired 4734 seropositive or seronegative results (Table 1). We found that 51.0% (2414/4734) of the study participants were seropositive.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 4734 | 100 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1937 | 40.9 |

| Female | 2797 | 59.1 |

| Subtotal | 4734 | 100 |

| Age (y) | ||

| 16‐19 | 20 | 0.4 |

| 20‐29 | 685 | 14.5 |

| 30‐39 | 889 | 18.8 |

| 40‐49 | 1115 | 23.6 |

| 50‐59 | 1225 | 25.9 |

| 60‐69 | 603 | 12.7 |

| ≥70 | 197 | 4.2 |

| Subtotal | 4734 | 100 |

| Geographic area | ||

| Seoul | 782 | 16.5 |

| Gyeonggi | 1587 | 33.5 |

| Gangwon | 159 | 3.4 |

| Chungcheong | 483 | 10.2 |

| Kyungsang | 1133 | 23.9 |

| Cholla | 511 | 10.8 |

| Jeju | 79 | 1.7 |

| Subtotal | 4734 | 100 |

| Household income | ||

| Low | 1452 | 30.7 |

| Medium | 2655 | 56.2 |

| High | 621 | 13.1 |

| Subtotal | 4728 | 100 |

| Education level | ||

| Low | 593 | 12.6 |

| Medium | 1371 | 29.0 |

| High | 2761 | 58.4 |

| Subtotal | 4725 | 100 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| <18.5 | 228 | 4.9 |

| 18.5‐23.0 | 2151 | 45.8 |

| 23.0‐25.0 | 1072 | 22.8 |

| ≥25.0 | 1242 | 26.5 |

| Subtotal | 4693 | 100 |

| Family history of gastric cancer | ||

| No | 4362 | 92.2 |

| Yes | 369 | 7.8 |

| Subtotal | 4731 | 100 |

We compared the H. pylori seropositivity of asymptomatic participants among the 1998, 2005, and 2011 studies7, 8, 9 and this study. The overall seropositivity of 51.0% (95% CI: 49.6‐52.4%) in this study represented a significant decrease from 66.9% (95% CI: 65.4‐68.6%) in 1998, 59.6% (95% CI: 58.5‐60.7%) in 2005, and 54.4% (95% CI: 53.5‐55.4%) in 2011 (P < .001) (Figure 2). There was thus a significant decline in seropositivity between each successive study. The arithmetical decrease rates per year were 0.81%, 0.87%, and 0.85% during 1998‐2005, 2005‐2011, and 2011‐2015, respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Helicobacter pylori seropositivity with previous data 7, 8, 9 in asymptomatic adult participants in South Korea

3.2. Risk factors for H. pylori seropositivity

Age, body mass index (BMI), geographic area, and education level were significantly associated with H. pylori seropositivity (Table 2). Individuals aged 20‐29 years showed the lowest H. pylori seropositivity (24.2%) and this increased up to 64.3% in those aged 50‐59 years (OR 4.67, 95% CI: 3.71‐5.86). A similar trend was observed according to geographic area (Figure 3). The peak prevalence group was distributed among age groups 40‐49 (Seoul), 50‐59 (Gyeonggi, Chungcheong, and Kyungsang), and 60‐69 (Gangwon, Cholla, and Jeju). Although H. pylori seropositivity was 32.1% (511/1594) in participants younger than 40 years, it was 60.6% (1903/3140) in those 40 or older.

Table 2.

Risk factors for Helicobacter pylori seropositivity (multivariable logistic regression)

| Total | Seropositive H. pylori | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | |||||

| Total | 4734 | 2414 | 51.0 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1937 | 1048 | 54.1 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 1.15 |

| Female | 2797 | 1366 | 48.8 | Ref | ||

| Age (y) | ||||||

| 16‐19 | 20 | 6 | 30.0 | 0.85 | 0.29 | 2.45 |

| 20‐29 | 685 | 166 | 24.2 | Ref | ||

| 30‐39 | 889 | 339 | 38.1 | 1.85 | 1.47 | 2.31 |

| 40‐49 | 1115 | 643 | 57.7 | 3.82 | 3.06 | 4.76 |

| 50‐59 | 1225 | 788 | 64.3 | 4.67 | 3.71 | 5.86 |

| 60‐69 | 603 | 371 | 61.5 | 4.01 | 3.03 | 5.30 |

| ≥70 | 197 | 101 | 51.3 | 2.65 | 1.83 | 3.83 |

| Geographic area | ||||||

| Seoul | 782 | 371 | 47.4 | Ref | ||

| Gyeonggi | 1587 | 708 | 44.6 | 1.04 | 0.86 | 1.25 |

| Gangwon | 159 | 78 | 49.1 | 1.23 | 0.85 | 1.76 |

| Chungcheong | 483 | 286 | 59.2 | 1.33 | 1.03 | 1.72 |

| Kyungsang | 1133 | 624 | 55.1 | 1.46 | 1.20 | 1.77 |

| Cholla | 511 | 304 | 59.5 | 1.52 | 1.19 | 1.94 |

| Jeju | 79 | 43 | 54.4 | 1.63 | 0.99 | 2.68 |

| Household income | ||||||

| Low | 1452 | 778 | 53.6 | 0.92 | 0.73 | 1.15 |

| Medium | 2655 | 1306 | 49.2 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 1.11 |

| High | 621 | 327 | 52.7 | Ref | ||

| Education level | ||||||

| Low | 593 | 368 | 62.1 | 1.21 | 0.95 | 1.56 |

| Medium | 1371 | 800 | 58.4 | 1.23 | 1.06 | 1.42 |

| High | 2761 | 1243 | 45.0 | Ref | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 228 | 78 | 34.2 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 1.23 |

| 18.5‐23.0 | 2151 | 1012 | 47.0 | Ref | ||

| 23.0‐25.0 | 1072 | 591 | 55.1 | 1.14 | 0.97 | 1.34 |

| ≥25.0 | 1242 | 707 | 56.9 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 1.37 |

| Family history of gastric cancer | ||||||

| No | 4362 | 2199 | 50.4 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 369 | 214 | 58.0 | 1.08 | 0.86 | 1.35 |

The multivariable logistic regression included 4681 individuals.

Figure 3.

Helicobacter pylori seropositivity according to geographic area and age group in South Korea

Participants with a high BMI (≥25.0 kg/m2) showed higher H. pylori seropositivity than those with a relatively normal BMI (18.5‐23.0 kg/m2) (OR 1.17, 95% CI: 1.00‐1.37).

Chungcheong, Kyungsang, and Cholla, all located in the southern part of South Korea, showed higher H. pylori seropositivity than Seoul (Figure 4). H. pylori seropositivity rates were below 50% in Seoul and the adjacent provinces (Gyeonggi and Gangwon).

Figure 4.

Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in seven geographic areas in South Korea

Participants who had a medium education level showed a 23% increase in H. pylori seropositivity compared with those with a high education level (OR 1.23, 95% CI: 1.06‐1.42). Sex, household income, and family history of gastric cancer had no influence on H. pylori seropositivity in multivariable logistic regression analysis.

3.3. Impact of habitation according to life period on H. pylori seropositivity

We investigated H. pylori seropositivity according to habitation type (city vs noncity) and life period (Table 3). Participants who lived in non‐city–city–city circumstances according to life period showed higher H. pylori seropositivity than those who lived in city–city–city circumstances (58.4% vs 46.6%, P < .001). Additionally, participants who lived in city circumstances throughout life showed lower H. pylori seropositivity than those who lived in noncity circumstances throughout life (46.6% vs 62.8%, P < .001) and showed lower H. pylori seropositivity than those with non‐city–non‐city–city circumstances throughout life (46.6% vs 56.9%, P < .001).

Table 3.

Helicobacter pylori seropositivity according to habitation type and life period

| Group | Preschool | School‐age | After high school | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | City | City | City | 1381/2946 | 46.6 |

| 2a | Noncity | City | City | 283/485 | 58.4 |

| 3a | Noncity | Noncity | City | 428/752 | 56.9 |

| 4a | Noncity | Noncity | Noncity | 290/462 | 62.8 |

| 5 | City | City | Noncity | 16/30 | 53.3 |

| 6 | City | Noncity | City | 5/16 | 31.3 |

| 7 | Noncity | City | Noncity | 4/6 | 66.7 |

| 8 | City | Noncity | Noncity | 3/5 | 60.0 |

We compared groups 1‐4 by considering the relatively large participant number. A P value less than .008 was considered significant due to multiple comparisons.

Group 1 vs 2, P < .001; group 1 vs 3, P < .001; group 1 vs 4, P < .001; group 2 vs 3, P = .618; group 2 vs 4, P = .164; group 3 vs 4, P = .044.

4. DISCUSSION

The H. pylori seropositivity of Korea in 2015 and 2016 was 51.0%, and we confirmed a decrease in H. pylori seropositivity compared with previous studies (from 66.9% in 1998 to 51.0% in 2015). In general, H. pylori is more prevalent in developing countries and less prevalent in developed countries. Our result agrees with the development status of Korea, whose gross domestic products per capita were $12,000 in 2000 and $27,000 in 2015.11

We found decreased H. pylori seropositivity, particularly in those aged 30‐39 years, compared with the three previous Korean nationwide studies. Previous studies reported seropositivity rates in those aged 30‐39 years of 74%, 49%, and 42% in 1998, 2005, and 2011, respectively. Considering that prevalence in less developed regions may reach 70% or higher, compared with 40% or less in more developed regions,12 our result (38.1%) is the first to be below 40% in those aged 30‐39 years. In addition, there was a large increase in seropositivity from those aged 30‐39 years to those aged 40‐49 years in our present study series. However, the biggest increase was shown from those aged 20‐29 years to those aged 30‐39 years in previous Korean studies.

Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer are endemic to Japan and China, as well as Korea.1, 13 Japan has shown a decrease in H. pylori prevalence, similar to Korea. In several birth cohort studies from Japan, Japanese individuals born before 1950 showed a H. pylori prevalence rate of 80%‐90%, but those born during the 1980s showed a H. pylori prevalence of 10%‐20%.14, 15 Recent Japanese studies reported that the H. pylori seropositivity in junior high school students was only 3%‐5%.16, 17 Although we did not analyze the birth cohort effect, our lowest seroprevalence rate was 24% in those aged between 20 and 29 years. Also, the highest prevalence rate was observed in those aged between 50 and 59 years. These trends were shown across all seven geographic areas in South Korea. H. pylori seroprevalence data from China have also shown a decrease, from 60% in 1983 to 45% in 2010.18, 19, 20 Korea might show lower prevalence in the future with improved general hygiene, economic development, and a sustained decrease in prevalence among generations.

Although Korea is a small and high internal migration country, we anticipated a geographic difference in H. pylori seropositivity. For the first time among studies of this nature, we distributed the study population among seven geographic areas to adapt to the population census result for H. pylori prevalence in Korea. We found that the capital region (Seoul and Gyeonggi) showed lower H. pylori seropositivity than other areas. This trend was also reported in a previous Korean study in 2011.9 Interestingly, as the distance from the capital region increased, so did the odds ratio of H. pylori prevalence. This may be due to urbanization levels, and we indirectly analyzed this effect according to life period. After the exclusion of groups with a small sample size listed in Table 3, participants who lived in a city throughout their life showed the lowest H. pylori seropositivity. Consistently, a recent Chinese study reported that urban populations had lower rates of H. pylori infection than rural populations.20

In our study, we observed that subjects with higher education level tended to show lower H. pylori prevalence. Considering the increasing proportion of city residence after high school (63.9%, 86.7%, and 96.2% in low, medium, and high education level, respectively) as seen in our study population, this result may be explained by the effect of urbanization.

Helicobacter pylori was more prevalent in obese patients (BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2) than in those with a normal BMI range (OR 1.17, 95% CI: 1.00‐1.37). However, other BMI groups showed no difference compared with the normal BMI group. And the association between obesity and H. pylori infection is controversial, and the causality of these associations has not been proven.2, 21, 22 We also investigated the correlation between BMI and residence style after high school (city vs noncity) but observed no significant correlation between the two (data not shown).

We found no sex differences in the prevalence of H. pylori (OR 1.00, 95% CI: 0.88‐1.15), but a recent meta‐analysis of 169 studies reported that male sex was associated with a higher prevalence of H. pylori (OR 1.12, 95% CI: 1.09‐1.15).23 Our current study was not designed to determine sex differences and several confounding factors were not assessed (such as smoking history, urinary tract infection history in women, and sex hormones).

Our study had some limitations of note. First, there may have been a selection bias. We enrolled asymptomatic participants from tertiary hospitals or their health screening centers. Thus, we may have enrolled more participants with a higher socioeconomic status. Second, there could have been a recall bias. We considered the habitation status of our study patients but this is a relatively subjective parameter and might be recalled incorrectly. Third, although this was a prospective study, the enrollment period was relatively long. However, most participants (91%) were enrolled in 2015.

In conclusion, our current multicenter, nationwide study found a decrease in H. pylori seroprevalence in South Korea and a difference in the seroprevalence rate according to geographic area and habitation type. Our findings could be useful as future baseline data or to inform H. pylori‐related policies in Korea.

DISCLOSURES OF INTERESTS

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research Foundation Grant.

Lee JH, Choi KD, Jung H‐Y, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Korea: A multicenter, nationwide study conducted in 2015 and 2016. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12463 https://doi.org/10.1111/hel.12463

REFERENCES

- 1. Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420‐429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection‐the Maastricht V/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2017;66:6‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Forman D, de Martel C. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori . Int J Cancer. 2015;136:487‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet‐Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pan KF, Zhang L, Gerhard M, et al. A large randomised controlled intervention trial to prevent gastric cancer by eradication of Helicobacter pylori in Linqu County, China: baseline results and factors affecting the eradication. Gut. 2016;65:9‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asaka M, Mabe K, Matsushima R, Tsuda M. Helicobacter pylori eradication to eliminate gastric cancer: the Japanese strategy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44:639‐648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim JH, Kim HY, Kim NY, et al. Seroepidemiological study of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic people in South Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:969‐975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter. 2007;12:333‐340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lim SH, Kwon JW, Kim N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Der Ende A, van Der Hulst RW, Roorda P, Tytgat GN, Dankert J. Evaluation of three commercial serological tests with different methodologies to assess Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4150‐4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. GDP per capita (current US$) from The World Bank: Data. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD. Accessed August 7, 2017.

- 12. Inoue M. Changing epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:3‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359‐E386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asaka M, Kimura T, Kudo M, et al. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:760‐766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Watanabe M, Ito H, Hosono S, et al. Declining trends in prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection by birth‐year in a Japanese population. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:1738‐1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kusano C, Iwasaki M, Kaltenbach T, Conlin A, Oda I, Gotoda T. Should elderly patients undergo additional surgery after non‐curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer? Long‐term comparative outcomes Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1064‐1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakayama Y, Lin Y, Hongo M, Hidaka H, Kikuchi S. Helicobacter pylori infection and its related factors in junior high school students in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forman D, Sitas F, Newell DG, et al. Geographic association of Helicobacter pylori antibody prevalence and gastric cancer mortality in rural China. Int J Cancer. 1990;46:608‐611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu D, Shao J, Wang L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese maritime workers. Ann Hum Biol. 2013;40:472‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nagy P, Johansson S, Molloy‐Bland M. Systematic review of time trends in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China and the USA. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lane JA, Murray LJ, Harvey IM, Donovan JL, Nair P, Harvey RF. Randomised clinical trial: Helicobacter pylori eradication is associated with a significantly increased body mass index in a placebo‐controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:922‐929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu MY, Liu L, Yuan BS, Yin J, Lu QB. Association of obesity with Helicobacter pylori infection: a retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2750‐2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ibrahim A, Morais S, Ferro A, Lunet N, Peleteiro B. Sex‐differences in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in pediatric and adult populations: systematic review and meta‐analysis of 244 studies. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:742‐749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]