Abstract

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has evolved into a chronic disease that is managed with tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Now that long‐term survival has been achieved in patients with CML, the focus of treatment has shifted to dose optimization, with the goal of maintaining response while improving quality of life. In this review, the authors discuss optimizing the dose of the second‐generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib. Once‐daily dosing regimens for dasatinib in the first and later lines of treatment were established through long‐term (5‐year and 7‐year) trials. Recently published data have indicated that further dose optimization may maintain efficacy while minimizing adverse events. Results obtained from dose optimization and discontinuation trials currently in progress will help practitioners determine the best dose and duration of dasatinib for patients with CML, because treatment decisions will be made through continued discussions between physicians and patients. Cancer 2018;124:1660‐72. © 2018 The Authors. Cancer published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of American Cancer Society. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐NonCommercial License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and is not used for commercial purposes.

Keywords: BCR‐ABL positive, chronic, dasatinib, dose optimization, leukemia, myelogenous, quality of life, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Short abstract

The focus of the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia is shifting to dose management, with the goal of maintaining response while improving quality of life. Results obtained from dasatinib dose optimization and discontinuation trials will help practitioners determine the best dose and duration of dasatinib for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia.

INTRODUCTION

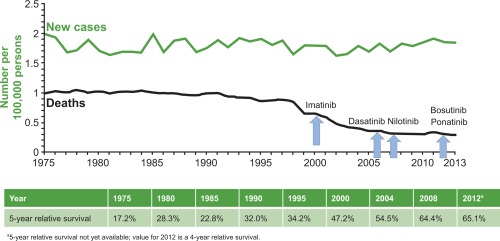

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has evolved into a chronic disease that now is managed with tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy.1, 2 As a result of the use of TKIs approved for CML, patients diagnosed in 2013 are predicted to lose <3 life‐years compared with those without CML, and thus have life spans approaching those of the general population.3, 4 In the United States, rates for new CML cases have been stable over the past 10 years; however, death rates have been decreasing an average of 3.1% each year from 2004 through 2013 (Fig. 1).5 Approximately 65% of patients with CML survived ≥5 years from 2006 through 2012, as opposed to the 5‐year period ending in 2000, when <50% of patients survived ≥5 years.

Figure 1.

Deaths due to chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) relative to the approval of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). The number of new CML cases and the number of deaths due to CML for the years 1992 through 2013 are shown, with the approval of TKIs for the treatment of CML indicated. Reproduced from SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Statistics at a Glance. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cmyl.html. Accessed May 31, 2016 (available in the public domain).5

Now that long‐term survival has been achieved in patients with CML, the focus of treatment has shifted to dose optimization and personalization. Dasatinib is a second‐generation BCR‐ABL1 kinase inhibitor, and currently is approved at 2 doses6: 1) 100 mg once daily for patients with CML in chronic phase (CML‐CP) that is newly diagnosed or after resistance to or intolerance of a previous therapy; and 2) 140 mg once daily for patients with CML in accelerated/blast phase (CML‐AP/BP) or with Philadelphia chromosome‐positive acute lymphocytic leukemia who are resistant or intolerant to prior therapy. Optimization of dasatinib dosing should have 2 goals: 1) the maintenance of cytogenetic and molecular responses; and 2) the minimization of adverse events (AEs). In particular, optimization should describe the minimum daily dose of dasatinib that can sustain disease remission and achieve a patient's therapeutic goals.

Maintaining or improving quality of life (QOL) for patients with CML over the course of their treatment should be a major component of minimizing AEs. QOL may influence a patient's decision to seek treatment regimens of dasatinib that balance efficacy with the fewest AEs, and also offer the easiest adherence.7 For example, a drug taken once per day is preferable to one requiring multiple daily doses, and a drug that may be taken regardless of the type or timing of food is preferable to one that requires timing with regard to meals or that cannot be taken with certain foods. Younger female patients with CML who are treated with imatinib have reported lower QOL compared with the general population8; this finding suggests that for those who anticipate being on a TKI for many years, QOL aspects of treatment may be especially important.

Ongoing studies are helping to refine treatment options that may be appropriate for some patients, including dasatinib dose reductions, interruptions, or discontinuation. It is the goal of this review to bring clarity to the field of dasatinib dose optimization by discussing published retrospective analyses and ongoing prospective studies. In particular, we discuss factors that drive the selection of the optimal dasatinib dose and duration for the treatment of patients with CML.

Optimizing Currently Approved Doses of Dasatinib

The currently approved doses of dasatinib resulted from 2 long‐term pivotal trials aimed at maximizing efficacy while minimizing AEs. The CA180‐034 trial enrolled patients with imatinib‐resistant or imatinib‐intolerant CML‐CP.9 This study compared dasatinib at a dose of 100 or 140 mg per day, and once‐daily or twice‐daily schedules, to determine the optimal dosage and regimen. The results indicated that dasatinib treatment at a dose of 100 mg once daily demonstrated durable efficacy and a tolerable long‐term safety profile. The data obtained from this study should be considered the proof of principle that the daily dose of dasatinib can be lowered, from 70 mg twice per day (a total dose of 140 mg per day) to 100 mg once per day in particular, while maintaining efficacy in patients intolerant of or resistant to imatinib.

The CA180‐056 DASISION trial (Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment‐Naïve Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients) was a study of newly diagnosed patients with CML‐CP who received dasatinib at a dose of 100 mg once daily or imatinib at a dose of 400 mg once daily for a minimum of 5 years.10 At the end of DASISION, dasatinib at a dose of 100 mg once daily continued to demonstrate improved efficacy compared with imatinib at a dose of 400 mg once daily in the first line. The safety profile of first‐line dasatinib at a dose of 100 mg once daily was well tolerated over the long term; no new safety signals were reported. Taken together, the results of the DASISION trial confirmed that a dose of 100 mg once daily constitutes an optimal dose of dasatinib for patients newly diagnosed with CML‐CP.

Dasatinib Dose Reductions and/or Interruptions

Efficacy and safety

There are published data indicating that modifying the dasatinib dose from 100 mg once daily can mitigate significant AEs yet maintain efficacy over the long term. In the phase 2 DARIA‐01 study, patients with CML‐CP were enrolled to determine factors influencing adherence and efficacy when AEs from dasatinib were managed with dose modifications.11 Patients had their dasatinib doses reduced from 100 mg per day to 50 mg per day when they experienced a nonhematologic AE of grade ≥2 or a hematologic AE of grade ≥3. In this small study, approximately 25% of patients had their doses reduced in the first 3 months, and 34% had their doses reduced in the first 6 months. At 6 months, 25 patients (78%) achieved a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) and 13 (40%) achieved a major molecular response (MMR). In addition, pleural effusions were managed effectively through dose modifications while molecular responses were maintained. In a small phase 2 study, NordCML006, 9 patients who had dasatinib doses reduced (6 patients to an average of 50 mg per day and 3 patients to an average of 63 mg per day) had nearly the same median rate of molecular response with a 4.5‐log reduction of BCR‐ABL1 transcripts (MR4.5) as did the 8 patients who were maintained on a dose of 100 mg per day (P = .53).12

Previously, a retrospective analysis of exposure and response to dasatinib in the CA180‐034 trial demonstrated that major cytogenetic response was significantly associated with average steady‐state dasatinib plasma concentrations.13 Reducing the daily dose from 70 mg twice daily to 100 mg once daily minimized AEs while maintaining efficacy by exploiting differences in measures of exposure: the patients receiving the dose of 100 mg once daily were found to have the lowest steady‐state trough concentration of the 4 dose arms investigated in CA180‐034. Although patients in this arm also had the lowest weighted average steady‐state dasatinib plasma concentrations, they also had the highest dose maintenance and efficacy. Moreover, pleural effusion was significantly associated with trough concentration, and thus occurred the least in the treatment arm receiving 100 mg once daily.

To the best of our knowledge, the first‐line OPTIM DASATINIB (Optimized Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Monotherapy) trial currently is the only prospective study of dose optimization based on therapeutic drug monitoring.14 This is a phase 2 trial with 289 newly diagnosed patients with CML‐CP enrolled to validate a dose optimization strategy using plasma levels of dasatinib. As part of the study, patients with high minimal plasma concentrations (Cmin ≥3 nmol/L) had their dasatinib doses reduced in 20‐mg decrements every 15 days to 40 mg per day (if needed) to lower the Cmin to <3 nmol/L. Preliminary results of OPTIM DASATINIB demonstrated that patients allocated to this therapeutic drug monitoring strategy showed a reduced risk of pleural effusion without impairment of the kinetics of response. By 24 months, approximately 88% of the patients with high Cmin values who then had their dasatinib doses lowered achieved MMR; 69% achieved molecular response with a 4‐log reduction of BCR‐ABL1 transcripts (MR4.0); and 39% achieved MR4.5, which is considered a complete molecular response/remission (CMR). Moreover, the dose optimization strategy reduced the risk of pleural effusion in the study population, which is consistent with the data obtained by Wang et al in their retrospective analysis described above.13, 14

Intermittent dosing with dasatinib has been shown to improve tolerability in patients with CML who were resistant to or intolerant of imatinib.15 A strategy of 3 to 5 days of dasatinib, followed by 2 to 4 days of no drug, reduced toxicity while maintaining efficacy. Overall, 18 of 31 patients (58%) maintained or had improved response while receiving weekly treatment, and 16 of 18 patients (89%) achieved MMR or MR4.5. A larger study in which 176 patients with CML received reduced and/or interrupted dosing of dasatinib or nilotinib demonstrated there was no statistically significant difference between rates of major cytogenetic response or CCyR.16 The median lowest dasatinib doses given in this study were 60 mg per day for patients with CML‐CP and 80 mg per day for patients with CML‐AP.16

In addition, several case reports have corroborated the results of the previously discussed studies. In one report, a patient aged 85 years was successfully treated with 20 mg of dasatinib twice weekly after developing liver dysfunction while receiving imatinib and achieved MMR 24 months later.17 In another report, 2 patients with CML‐CP were treated with 20 to 50 mg per day of dasatinib; 1 patient maintained undetectable BCR‐ABL1 transcripts for up to 1 year and 1 patient had levels of BCR‐ABL1 transcripts that were 4 to 5 logs reduced (at times the levels were undetectable).18

Predicting which patients will benefit from dose reductions

Early molecular responses to a TKI (within the first 6 months of initiating treatment) are predictive of long‐term outcomes in patients with CML, and several studies have shown that TKIs induced fast and deep molecular responses, defined as MR4.0 or even MR4.5.19, 20, 21 These levels of responses predict durable, stable responses, and are considered prerequisites for either dose reductions or dose interruptions.

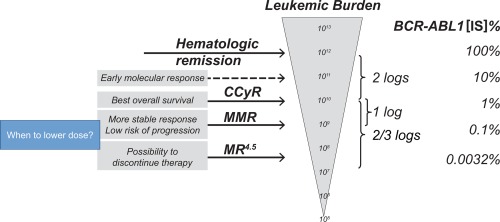

Both the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommendations define optimal responders in terms of molecular responses.19, 22, 23 Therefore, at least for some patients, if deep molecular responses (MR4.0 or MR4.5) have been achieved after a treatment period, it should be possible to reduce dasatinib doses (Fig. 2).19 However, molecular monitoring at fixed intervals is recommended by both the NCCN (every 3 months to 6 months 2 years after the achievement of CCyR)22 and the ELN (after the achievement of MMR),23 which may result in missing the optimal time to reduce doses of dasatinib. For example, if a deep response occurs early in this timeframe between tests, the opportunity for a dose reduction may be missed or delayed.

Figure 2.

Deciding when to lower the dose based on leukemic burden and BCR‐ABL1 transcript levels. BCR‐ABL1 transcript levels are monitored by real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The relationship to transcript levels and possible outcomes is indicated. CCyR indicates complete cytogenetic response; IS, International Scale; MMR, major molecular response; MR4.5, molecular response with 4.5‐log reduction of BCR‐ABL1 transcripts. Reproduced without modification from Morotti A, Fava C, Saglio G. Milestones and monitoring. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10:167‐172. ©The Authors 2015. Published with open access at http://Springerlink.com under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).19

Final study results from the 5‐year DASISION trial for patients with CML‐CP who received first‐line dasatinib confirmed that achieving an early molecular response, BCR‐ABL1 ≤10% International Scale (IS) at 3 months, was correlated with significantly higher progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates (88.9% and 93.8%, respectively, for PFS and OS) compared with patients who achieved BCR‐ABL1 >10% (IS) at 3 months (71.8% and 80.6%, respectively, for PFS and OS).10 For patients who received dasatinib after failing or becoming intolerant of imatinib in the 7‐year CA180‐034 study, those who achieved BCR‐ABL1 ≤10% (IS) at 3 months likewise demonstrated significantly higher PFS and OS rates (56% and 72%, respectively) compared with those who had BCR‐ABL1 >10% (IS) at 3 months (21% and 56%, respectively, for PFS and OS).9

Tools predicting outcome at any time during and after therapy would be useful throughout a patient's treatment regimen. Using data from DASISION and CA180‐034,9, 10 investigators predicted responses during treatment with dasatinib based on plotting BCR‐ABL1 transcript levels and the PFS or OS of patient populations.24 Such analyses may allow investigators to predict future outcomes at any time, rather than solely at times of BCR‐ABL1 monitoring. A limitation of these projections would be that they become less precise as more time elapses from the initiation of TKI therapy: the number of patients for whom a prediction might be made diminishes, thereby reducing the accuracy of the prediction. Increasing the number of patients in the cohort is one way to negate this limitation (eg, by combining suitable data sets).

In addition to molecular responses, effects on CD34‐positive (CD34+) cells may provide another means with which to predict responses to dasatinib. A study of newly diagnosed patients with CML‐CP demonstrated that the molecular responses at 3 months and 6 months depended on the time dasatinib plasma levels were above the one‐half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for CD34+ cells (the dasatinib concentration required to inhibit 50% of CD34+ cells).25 It was found that patients with longer times (>12 hours) above the IC50 had significantly better prognoses: molecular responses at 3 and <4 log reductions were 50% and 45%, respectively.

Other patient factors

Patient preference should be taken into consideration when deciding to modify dasatinib doses. Reductions and/or interruptions may be preferred by patients when discontinuing dasatinib is not an option; administering a lower dose of dasatinib, after initiating treatment at the approved dose, may be preferable to switching to another TKI.16 Moreover, modifying doses (lowering or interrupting) to mitigate toxicity may help to improve adherence.11

In addition to minimizing AEs, economic concerns may drive the decision to lower daily doses for some patients.26 In one study, 41 patients with CML‐CP were treated with a mean dose of dasatinib of 92 mg ± 23 mg per day while achieving and maintaining efficacy, although the quality of the responses was not reported.26 The driving force for reducing doses in this study appears to have been financial, rather than a reduction in AEs. Furthermore, because the long‐term survival of patients with CML is predicted to increase the prevalence of the disease in the near future, the burden of health care costs may have to be considered when planning treatment. Thus, economic considerations beyond the personal may play a role in seeking the lowest effective dose of dasatinib or of any TKI.27 Many of these cost concerns may be mitigated in the future, as approved generic versions of TKIs become available.

Ongoing trials investigating dasatinib efficacy with dose optimization

Nine trials currently are under way that focus on modifying dasatinib dosing while retaining efficacy; their full titles, registry numbers, and summaries are shown in Table 1.11, 14, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 55 Two of these studies, DARIA‐0111 and OPTIM DASATINIB,14 have reported preliminary data and are described above.

Table 1.

Ongoing Clinical Trials for Reduced/Interrupted Dosing of Dasatinib

| Registry Information | Trial Title | Arm(s) (No. of Patients Enrolled) | Intervention(s) | Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UMIN000007345 (Japanese Ministry of Health; DARIA‐01 study)11, 33 | A Phase 2 Study Of Midterm Compliance And Effectiveness Of Dasatinib Therapy In Patients With CML | Single‐arm (N = 32) | Dasatinib at a dose of 100 mg/d, which was either interrupted or lowered to 50 mg/d |

• Compliance with dasatinib therapy at 12 mo • Treatment‐related toxicity • Relationship between serum concentration of dasatinib and clinical result • OS and PFS rates at 1 y |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01916785 (OPTIM DASATINIB)14, 34 | OPTIM DASATINIB (Optimized Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Monotherapy) | Two arms, randomized (N = 289) | Dasatinib doses will be optimized based on plasma values (target Cmin ≥3 nmol/L); dasatinib doses start at 100 mg/d |

• Cumulative rate of significant AEsa

• Rate and duration of treatment interruptions • Dose of dasatinib • Cumulative rates of CCyR, CMR, and MMR • Time to molecular response • Correlation between dasatinib plasma levels and efficacy • OS and PFS at 5 y • Lymphocyte counts before and during dasatinib • Rate of sustained major molecular remission after dasatinib discontinuation |

| UMIN000003499 (Japanese Ministry of Health)36 | Phase 2 Clinical Trial Of Low‐Dose Dasatinib In Patients With Resistant Or Intolerant CML Who Are Treated With Low‐Dose Imatinib | Single‐arm (N = 30)b | Dasatinib at a dose of 50 mg/d, then 100 mg/d | • MMR after 12 mo |

| ACTRN12616000738426 (Australia; CML12 DIRECT)55 | The DIRECT study: Individualized Dasatinib Dosing For Elderly Patients With Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia | Single‐arm (N = 80)b | Patients aged ≥60 y will receive dasatinib at a dose of 100 mg/d, 70 mg/d, 50 mg/d, or 50 mg every other d |

• Incidence of treatment‐related pleural effusion • Molecular responses • Survival • Correlation between dasatinib trough levels, intensity, and response and toxicity • QOL • Percentage of patients eligible for treatment‐free remission • Percentage of patients with different mechanisms of resistance • Overall tolerability |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01804985 (DESTINY)28 | De‐Escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib or sprYcel in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia | Three arms, open‐label (N = 168)b | Imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib, at one‐half the standard dose for 12 mo (imatinib, 200 mg/d; nilotinib, 400 mg/d; dasatinib, 50 mg/d) |

• Percentage of patients who maintain MMR on one‐half dose for 12 mo, then discontinue drug for 24 mo • Percentage of patients who regain MMR after reinitiating TKI • QOL • Health economic assessment • Investigation of patients more likely to develop disease recurrence through laboratory values |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT0268944029 | Therapy of Early Chronic Phase CML With Dasatinib | Single‐arm (N = 100)b | Dasatinib at a dose of 50 mg/d |

• MMR at 12 mo • CCyR at 6 mo |

| LN_CMLSTU_2015_576 (European Leukemia Trial Registry; DasaHIT)30 | Treatment optimization for patients with CML with treatment‐naïve disease (first‐line) and patients with resistance or intolerance against alternative Abl‐Kinase inhibitors (≥second‐line) | Two arms, randomized (N = 306)b | NA |

• The cumulative toxicity score after 2 y of dasatinib treatment • MMR as assessed by BCR‐ABL1 (IS) monitoring by 24 mo |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT0232631131 | Optimization of TKIs Treatment and Quality of Life in Ph+ CML Patients ≥60 Years in Deep Molecular Response | Two arms, randomized (N = 502)b | Fixed (1 mo on/1 mo off) vs progressive (1 mo on/1 mo off for the 1st y; 1 mo on/2 mo off for the 2nd y; 1 mo on/3 mo off for the 3rd y) intermittent administration of imatinib, dasatinib, or nilotinib | • Change in QOL from baseline, then at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 mo |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02348957 (DasPAQT)32 | Treating Patients With CML in Chronic Phase With Dasatinib | Observational (N = 300)b | This study is designed to collect real‐life data regarding CML treatment with dasatinib, with respect to first‐line and second‐line treatment, and switching from another TKI in first‐line to dasatinib in second‐line (it is anticipated that dose modifications will be part of the real‐life setting) |

• Distribution of molecular remission status at study entry and after 12 mo and 24 mo • Best possible response • Time to molecular remission and disease progression • Cytogenetic profile • Hematologic response • Patient adherence • Patient satisfaction • QOL • Safety and tolerability |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; Cmin, minimal plasma concentration; CCyR, complete cytogenetic response; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CMR, complete molecular response; IS, International Scale; MMR, major molecular response (BCR‐ABL1 [IS] < 0.1%); NA, not available; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome positive; QOL, quality of life; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Defined by grade 3 to 4 fluid retention, all‐grade pleural effusion, hematological grade 3 to 4 AEs related to dasatinib, and/or all AEs leading to dasatinib discontinuation within the first year of therapy.

Estimated enrollment.

There are 4 studies currently under way to determine optimizing dasatinib doses in patients or patient subgroups. A low‐dose study in Japan will evaluate the efficacy of 50 mg of dasatinib per day in patients who are resistant to or intolerant of low‐dose imatinib; the primary outcome measure is MMR at 12 months.36 The CML12 DIRECT (Dasatinib Intensity Regulation to Eliminate Cumulative Toxicities) study55 will examine dose optimization of dasatinib in patients aged ≥60 years with CML. In this study, therapeutic daily monitoring will be used to optimize effective doses with minimal toxicity.55 The DESTINY (De‐Escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib or sprYcel) trial will evaluate efficacy at a dose of 50 mg per day of dasatinib in treatment‐naive patients with CML‐CP28; its primary outcome is the percentage of patients who maintain MMR on a dose of 50 mg per day for 12 months. Patients then will discontinue dasatinib for up to 24 months. The Therapy of Early Chronic Phase Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia With Dasatinib trial will evaluate whether administering 50 mg dasatinib per day to patients with early CML‐CP is as effective as giving 100 mg per day.29

Two studies will examine dasatinib efficacy with planned dose interruptions. The DasaHIT trial will evaluate dasatinib holidays for improved drug tolerance in treatment‐naive patients with CML and in patients receiving dasatinib as second‐line treatment; its primary outcome measures are cumulative toxicity after 2 years and MMR as assessed by monitoring BCR‐ABL1 transcripts at 2 years.30 The Optimization of TKIs Treatment and Quality of Life trial will evaluate the efficacy of intermittent dasatinib dosing (1 month on/1 month off vs 1 month on/1 month off in year 1, 1 month on/2 months off in year 2, and 1 month on/3 months off in year 3) and the effect on QOL such dosing regimens may have; the primary outcome is changes in QOL at defined times.31

Finally, the DasPAQT (Treating Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Chronic Phase With Dasatinib) trial is a real‐life study to gather data regarding how CML is managed with dasatinib in practices outside of academic settings, including whether and when dose reductions are used.32

Dasatinib Discontinuation

Efficacy

Treatment‐free remission (TFR), defined as being free from molecular disease recurrence after TKI discontinuation,22 currently is an unmet need of CML therapy, because TKIs have increased patients' life spans to be nearly equal to those of the general population.3, 4 To our knowledge to date, there are limited published data regarding discontinuing dasatinib. In one small trial of 34 patients with CML‐CP, second‐generation TKIs (dasatinib and nilotinib) were safely discontinued.37 The 12‐month probability of maintaining stable MMR was 58%, and no patient progressed to CML‐AP or experienced hematologic disease recurrence. The OPTIM DASATINIB trial for newly diagnosed patients with CML also examined dose discontinuations in early responders (those who had BCR‐ABL1 [IS] ≤0.0032% by 3 years).38 Preliminary results demonstrated that at 12 months, approximately 41% of patients were in TFR. The DADI trial evaluated the effect of dasatinib discontinuation in patients with CML who had been in deep molecular response for at least 1 year.39 Preliminary results indicated that of the 63 patients who discontinued dasatinib, 30 maintained deep molecular responses and 33 experienced molecular disease recurrence (all during the first 7 months). The authors concluded that a treatment‐free period lasting for >1 year is feasible. The DASFREE trial is a study of patients with CML‐CP receiving either first‐line or subsequent lines of dasatinib who are in stable deep molecular response; the primary endpoint is the MMR rate at 12 months after discontinuation.40 An interim analysis of 30 patients demonstrated that 1 year after discontinuation, patients had a high TFR success rate (63% had MMR and molecular recurrence‐free survival at 12 months).41 There was rescue of molecular responses when dasatinib was reinitiated in all patients who developed disease recurrence. The STOP‐2G‐TKI study by the French CML group assessed maintenance of MMR after treatment discontinuation in patients who received second‐generation TKIs (dasatinib or nilotinib) and achieved MR4.5 for the previous 2 years or longer.42 TFR rates at 12 months and 48 months were 63% and 54%, respectively.

Predicting which patients will benefit from dasatinib discontinuation

Overall, relatively few patients are eligible for a treatment‐free period, and not all successfully maintain a response after discontinuation. For these patients, reducing dasatinib dosing as described above may be the best long‐term therapy choice. In deciding which patients to include in current TFR trials, investigators considered performance status, age, molecular response, mutational profile, and adequate organ function (Table 2).28, 34, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 For example, the DADI trial examined dasatinib discontinuations in patients who maintained a deep molecular response for >1 year.39 Patients with a performance status of 0 to 2 and with no severe dysfunction of major organ systems were eligible, but patients having BCR‐ABL1 mutations associated with dasatinib resistance, thus putting them at higher risk of disease recurrence, were not eligible. In the real‐life setting, clinicians have been guided by molecular responses (BCR‐ABL1 reductions of at least 4 logs, sustained for ≥2 years) and low Sokal risk scores. Among patients with low Sokal risk who are treated with imatinib, approximately 50% to 60% sustained a TFR, whereas among high‐risk patients, the percentage decreased to 10% to 20%.49

Table 2.

Ongoing Clinical Trials for Discontinuation of Dasatinib

| Registry Information | Trial Title | Arm(s) (No. of Patients Enrolled) | Inclusion Criteria | Description | Primary Endpoint(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01916785 (OPTIM DASATINIB)34, 38 | OPTIM DASATINIB (Optimized Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Monotherapy) | 2 arms, randomized (N = 289) |

• CML‐CP • ECOG PS 0‐2 • Adequate organ function • Dasatinib ≥3 y • MR4.5 for 2 y |

In addition to optimizing dasatinib dosing based on plasma values, this study is evaluating dasatinib discontinuation in early molecular responders | • Cumulative rate of significant AEsa |

| UMIN000005130 (Japanese Ministry of Health; DADI)39 | Dasatinib Discontinuation trial | Single‐arm (N = 88) |

• Imatinib‐resistant/intolerant CML‐CP • ECOG PS 0‐2 • No severe dysfunction of major organs • No BCR‐ABL1 mutations associated with dasatinib resistance • Dasatinib ≥1 y • MR4.0 for 1 y |

Patients with CML in sustained deep molecular response for at least 1 y to be monitored for treatment‐free remission | • Percentage of patients with treatment‐free remission at 6 mo after discontinuation (time from discontinuation to molecular recurrence) |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01850004 (DASFREE)40, 41 | Open‐Label Study Evaluating Dasatinib Therapy Discontinuation in Patients With Chronic Phase CML With Stable Complete Molecular Response | Single‐arm, open‐label (N = 71) |

• CML‐CP • ECOG PS 0‐1 • Dasatinib ≥2 y • MR4.5 ≥1 y |

Patients with CML in MR4.5 discontinue dasatinib to examine if response is maintained | • MMR at 12 mo |

| STOP‐2G‐TKI study42 | STOP second‐generation (2G)–tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) study | Single‐arm (N = 100) |

• Treatment with second‐generation TKI (dasatinib or nilotinib) ≥3 y • MR4.5 ≥2 y |

Aim is to evaluate treatment‐free remission after discontinuation of first‐line or subsequent lines of dasatinib or nilotinib in patients with CML with long‐lasting and deep molecular responses | • Treatment‐free remission (no loss of MMR) at 12 mo |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01887561 (D‐NewS)43 | Dasatinib for Patients Achieving Complete Molecular Response for Cure D‐NewS Trial | Single‐arm (N = 100)b |

• Newly diagnosed CML‐CP • ECOG PS 0‐2 • Adequate organ function • CMR |

Patients in CMR after dasatinib treatment discontinue therapy to examine if response is maintained | • Overall probability of maintenance of CMR after discontinuing dasatinib |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01627132 (D‐STOP)44 | Discontinuation of Dasatinib in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia‐CP Who Have Maintained Complete Molecular Remission for Two Years; Dasatinib Stop Trial | Single‐arm, open‐label (N = 50)b |

• CML‐CP • ECOG PS 0‐2 • Adequate organ function • CMR for 2 y |

Patients with CML in CMR on a dose of dasatinib of 100 mg/d will discontinue drug | • Overall probability of maintenance of CMR at 12 mo after stopping dasatinib |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01804985 (DESTINY)28 | De‐Escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib or sprYcel in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia | Three arms, open‐label (N = 168)b |

• CML‐CP • TKI treatment ≥3 y • ≥MMR for 1 y |

Imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib, given at one‐half the standard dose for 12 mo followed by discontinuation for a further 2 y | • Percentage of patients who maintain MMR on one‐half dose for 12 mo, then discontinue drug for 24 mo |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01761890 (CML1113)45 | Front‐line Treatment of BCR‐ABL+ Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) With Dasatinib | Observational (N = 133)b |

• CML‐CP • Dasatinib for 2 y |

Real‐life study of patients given first‐line dasatinib who discontinue drug after 2 y of treatment | • No. of patients who discontinue dasatinib permanently after 2 y |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02269267 (The LAST Study)46 | The Life After Stopping Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Study | Single‐arm, open‐label (N = 173)b |

• CML‐CP • TKI treatment ≥3 y • Currently receiving imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib • Documented MR4.0 ≥2 y |

Patients will discontinue TKI, be monitored for molecular recurrence, and report QOL using standard assessment tools |

• Percentage of patients with CML who develop molecular recurrence after discontinuing TKIs • Patient‐reported health status of patients before and after stopping TKI |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02268370 (TRAD)47 | Treatment‐free Remission Accomplished With Dasatinib in Patients With CML | Single‐arm, open‐label (N = 135)b |

• CML‐CP • Imatinib treatment ≥3 y • ECOG PS ≤ 2 • Adequate organ liver and renal functions •MR4.5 |

Patients will take their own supply of imatinib for 3 mo to ensure stable responses, then imatinib will be stopped and patients monitored for disease recurrence; if patient has a recurrence, then he or she will receive dasatinib for up to 2 y; if response is achieved after 1 y and maintained for another y, patient has the option to discontinue drug, with continued monitoring | • Molecular remission (change from baseline in molecular profile at 12 mo) |

| http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01596114 (EURO‐SKI)48 | European Stop Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Study | Single‐arm, open‐label (N = 800)b |

• CML‐CP • First‐line or second‐line TKI for ≥3 y • MR4.0 ≥1 y |

Main goal is assessment of duration of MMR after stopping TKI therapy | • Molecular recurrence‐free survival |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CML‐CP, chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase; CMR, complete molecular response; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; MMR, major molecular response; MR, molecular response (BCR‐ABL1 [International Scale] <0.1%); MR4.0, molecular response with 4.0‐log reduction of BCR‐ABL1 transcripts (BCR‐ABL1 [International Scale] <0.01%); MR4.5, molecular response with 4.5‐log reduction of BCR‐ABL1 transcripts (BCR‐ABL1 [International Scale] ≤0.0032%); QOL, quality of life; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Defined by grade 3 to 4 fluid retention, all‐grade pleural effusion, hematological grade 3 to 4 AEs related to dasatinib, and/or all AEs leading to dasatinib discontinuation within the first year of therapy.

Estimated enrollment.

Ongoing trials investigating the feasibility of dasatinib discontinuation

There are several trials focused on efficacy after discontinuation of dasatinib; these are summarized in Table 2 with their full titles and registry numbers.28, 34, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 In addition to the trials described above for which preliminary results have been published, the D‐NewS trial will assess whether dasatinib can be discontinued without molecular disease recurrence in patients with CML‐CP in CMR while receiving dasatinib; the primary outcome is the overall probability of maintaining a CMR after discontinuing dasatinib.43 The D‐STOP trial will evaluate the discontinuation of dasatinib for patients with CML‐CP who maintained CMR for 2 years; the primary outcome measure is the overall probability of maintenance of CMR at 12 months after discontinuation.44 The DESTINY trial also will evaluate whether patients with CML‐CP can discontinue treatment for 24 months while maintaining molecular responses.28 The Front‐line Treatment of BCR‐ABL+ Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) With Dasatinib (CML1113) trial will follow patients with CML‐CP for 5 years after discontinuation of treatment; the primary endpoint is the number of patients who permanently discontinue dasatinib.45 The LAST (Life After Stopping Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors) study will examine the decision‐making process for patients with CML‐CP and physicians who are considering discontinuing dasatinib; the primary endpoints are the percentage of patients with CML who develop molecular disease recurrence after discontinuing TKIs, and the patient‐reported health status before and after stopping TKIs.46 The purpose of the TRAD (Treatment‐free Remission Accomplished With Dasatinib in Patients With CML) trial is to determine whether an operational cure for CML is possible (an operational cure would mean the disease no longer requires treatment); the primary endpoint is molecular remission at 12 months.47 The EURO‐SKI (European Stop Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) trial will assess the duration of MMR after cessation of TKI therapy; patients with CML receiving first‐line or second‐line TKI treatment are eligible.48

DISCUSSION

The treatment of CML is evolving from a landscape in which patients were maintained on a TKI until failure or resistance occurred to one in which initial TKI treatment is induction therapy, which in turn may be succeeded by reduced or intermittent dosing as consolidation therapy.49 As the life expectancy of patients with CML now approaches that of the general population,3, 4 there is considerable interest in modifying doses of TKIs, including dasatinib, to mitigate AEs as well as to reduce cost burdens for patients and health care systems.26 The results of trials designed to optimize dasatinib doses for individual patients will help to guide future therapy. Accurate and timely molecular monitoring should be used to guide dose optimization. ELN and NCCN guidelines provide definitions of optimal responses to TKIs and recommendations for molecular monitoring.22, 23 However, what constitutes a CMR may not be an absolute, as more sensitive techniques are validated for future use.50

To our knowledge, clinical experience with dasatinib dose optimization is still largely unexplored, and thus there are questions that remain to be answered. Criteria for when doses should be modified have to be established. Currently, the majority of TFR trials require that patients be in molecular remission for at least 1 year. However, patients may have residual disease (Philadelphia chromosome‐positive progenitor cells) and have yet to develop disease recurrence.51 In practice, approximately 50% of patients treated for CML do not achieve MR4.5; therefore, it is most likely better for patients to receive drug doses that achieve remission first, then optimize doses for the long term. It is possible that doses resulting in BCR‐ABL1 transcript levels <1% will be sufficient for some patients. Among patients with imatinib‐resistant disease treated with either dasatinib or nilotinib, those with BCR‐ABL1 <1% versus ≥1% at 6 months were reported to have higher 3‐year MMR (83% vs 16%; P<.001), PFS (94% vs 84%; P = .05), and OS (94% vs 84%; P = .05).52 As trial data mature and are published, the answer to this question should become clearer.

The lowest induction and maintenance doses of dasatinib to achieve optimal responses need to be established. Despite what could be considered a short serum half‐life (3‐5 hours),53 lower and intermittent doses of dasatinib are proving to be effective treatment options. Beyond what long‐term studies indicate for induction doses,9, 10 patients have been maintained successfully on doses as low as 20 mg per day.18 A possible explanation for the efficacy of low‐dose dasatinib may be attributed to its high potency54 and prolonged inhibition of targets.53 For example, it has been reported that the mechanism of cellular apoptosis induced by dasatinib is comparable between continuous low‐dose and transient high‐dose treatment in vitro; however, the effects on proapoptotic molecules (eg, BIM) are prolonged with low‐dose (≥6 hours) versus high‐dose (20 minutes) exposure.53

To the best of our knowledge, the level of efficacy patients should maintain after dose modifications also has yet to be determined. Some level of molecular disease recurrence is likely, and re‐treatment with a TKI has been used successfully.49 Future clinical trials should be designed to determine whether administering induction followed by maintenance doses of dasatinib is a feasible treatment approach. As a word of caution, very long‐term follow‐up will be required for patients whose doses are modified to ensure they do not experience disease recurrence.

How to individualize therapy remains to be explored. Because clinical trials do not focus on individualized treatment, it is up to clinicians to take into account the needs of the patient: age, emerging AEs, or other factors may enter into the decision to modify dosing. It has been our experience that a dosing schedule involving weekend holidays (5 days of dasatinib followed by 2 days off the drug) has helped to mitigate AEs while maintaining efficacy; in addition, we have had positive experiences with alternate daily dosing. In our collective experience, we have treated >10 patients with modified doses of dasatinib who then maintained their previous response or improved from MMR to CMR. The majority of these patients initiated dasatinib at a dose of 100 mg per day and, on achieving MMR, had their daily doses lowered. In some cases, patients started at a dose of 70 mg per day and achieved MMR, never having received 100 mg per day. For the majority of patients, the responses have been durable. Our decisions to reduce doses were based on the molecular response achieved by the patient. Even if patients do not yet experience AEs, their doses could be lowered to prevent future AEs. This should be considered for special populations, especially the elderly.31

Pharmacogenomics may help to determine the optimal dose of dasatinib. As more becomes known regarding how genetics affects responses to dasatinib, pharmacogenomics may be used in the future to prescribe individualized doses. For example, variations in the P‐glycoprotein allele ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (ABCB1) affected the transport of dasatinib, imatinib, and nilotinib into cells, and thus have implications for efficacy at a given dose.56 Another study examined the influence of genetic polymorphisms in ABCB1 and ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2) (which help to confer multidrug resistance), the transcription factor Oct1, risk scores (Sokal, European Treatment and Outcome Study [EUTOS], and Hasford), and trough concentrations of imatinib on CCyR.35 The investigators found that a specific variant in ABCG2 correlated with increased CCyR and thus increased survival.35

Answers to these questions and others will come from prospective clinical trials. Many ongoing trials, as detailed above, are designed to determine how to modify the dose of dasatinib, the optimal time to modify dosing, the patients best suited for dose modifications, and the level of response that should be maintained on a modified dose.

Conclusions

Available data have suggested that administering dasatinib below currently approved doses may minimize AEs and maintain efficacy. Drug holidays (days of treatment respite) as an alternative to dose reductions is another means with which to mitigate AEs while keeping efficacy high. Maintenance therapy (administering a drug at a different dosing schedule to maintain a desired level of response) may be a suitable treatment goal, and data from current trials should aid in developing guidelines for what maintenance therapy should be. Treatment discontinuation often is a goal of CML treatment and certain patients may be well suited to withdraw from dasatinib therapy. Close follow‐up and dose re‐escalation, dose reinitiation, or switching to another TKI would be recommended for patients who demonstrate evidence of disease progression (eg, confirmed increase in BCR‐ABL1 levels by polymerase chain reaction). Ultimately, treatment decisions will be made through discussions between physicians and patients. The questions of when to reduce doses, for whom to reduce doses, and by how much to reduce doses cannot be settled until data from prospective studies have been analyzed.

FUNDING SUPPORT

Supported by Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Giuseppe Saglio has acted as a consultant and a speaker for ARIAD, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer for work performed outside of the current study. Ehab Atallah has served on advisory boards for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer and has received honoraria from ARIAD for work performed outside of the current study. Philippe Rousselot has received research grants from ARIAD, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Pfizer for work performed outside of the current study.

We wish to acknowledge Beverly Barton, PhD, of StemScientific (an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, funded by Bristol‐Myers Squibb) for providing medical writing and editorial support.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shah NP, Tran C, Lee FY, Chen P, Norris D, Sawyers CL. Overriding imatinib resistance with a novel ABL kinase inhibitor. Science. 2004;305:399‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib‐resistant Philadelphia chromosome–positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531‐2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bower H, Bjorkholm M, Dickman PW, Hoglund M, Lambert PC, Andersson TM. Life expectancy of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia approaches the life expectancy of the general population. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2851‐2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sasaki K, Strom SS, O'Brien S, et al. Relative survival in patients with chronic‐phase chronic myeloid leukaemia in the tyrosine‐kinase inhibitor era: analysis of patient data from six prospective clinical trials. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2:e186‐e193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) . Statistics at a Glance. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cmyl.html. Accessed May 31, 2016.

- 6. Sprycel (dasatinib) [prescribing information]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol‐Myers Squibb; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirji I, Gupta S, Goren A, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): association of treatment satisfaction, negative medication experience and treatment restrictions with health outcomes, from the patient's perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Efficace F, Baccarani M, Breccia M, et al. Health‐related quality of life in chronic myeloid leukemia patients receiving long‐term therapy with imatinib compared with the general population. Blood. 2011;118:4554‐4560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shah NP, Rousselot P, Schiffer C, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib‐resistant or ‐intolerant chronic‐phase, chronic myeloid leukemia patients: 7‐year follow‐up of study CA180‐034. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:869‐874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, et al. Final 5‐year study results of DASISION: The Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment‐Naïve Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2333‐2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mizuta S, Tsurumi H, Sawa M, et al. Management of adverse events associated with dasatinib during early periods of therapy in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia‐a clinical report of Daria‐01 Study [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124:4537. [Abstract 4537]. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hjorth‐Hansen H, Stenke L, Soderlund S, et al. Dasatinib induces fast and deep responses in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukaemia patients in chronic phase: clinical results from a randomised phase‐2 study (NordCML006). Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:243‐250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang X, Roy A, Hochhaus A, Kantarjian HM, Chen TT, Shah NP. Differential effects of dosing regimen on the safety and efficacy of dasatinib: retrospective exposure‐response analysis of a Phase III study. Clin Pharmacol. 2013;5:85‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rousselot P, Mollica L, Guerci‐Bresler A, et al. Dasatinib daily dose optimization based on residual drug levels resulted in reduced risk of pleural effusions and high molecular response rates: final results of the randomized OPTIM DASATINIB trial [abstract]. Haematologica. 2014;99(suppl 1):237. [Abstract S678]. [Google Scholar]

- 15. La Rosee P, Martiat P, Leitner A, et al. Improved tolerability by a modified intermittent treatment schedule of dasatinib for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia resistant or intolerant to imatinib. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1345‐1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Santos FP, Kantarjian H, Fava C, et al. Clinical impact of dose reductions and interruptions of second‐generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2010;150:303‐312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Imamura M. Efficacy of intermittently administered dasatinib with a reduced dose in an elderly patient with chronic myeloid leukemia. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:768‐770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jamison C, Nelson D, Eren M, et al. What is the optimal dose and schedule for dasatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: two case reports and review of the literature. Oncol Res. 2016;23:1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morotti A, Fava C, Saglio G. Milestones and monitoring. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10:167‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ross DM, Branford S, Seymour JF, et al. Safety and efficacy of imatinib cessation for CML patients with stable undetectable minimal residual disease: results from the TWISTER study. Blood. 2013;122:515‐522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mahon FX, Rea D, Guilhot J, et al; Intergroupe Français des Leucémies Myéloïdes Chroniques . Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1029‐1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia, version 2.2018. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2017. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/cml.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013;122:872‐884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quintas‐Cardama A, Choi S, Kantarjian H, Jabbour E, Huang X, Cortes J. Predicting outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia at any time during tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:327.e8‐334.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishida Y, Murai K, Yamaguchi K, et al; Inter‐Michinoku Dasatinib Study Group (IMIDAS) . Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dasatinib in the chronic phase of newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72:185‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aksu S, Sahin F, Uz B, et al. The clinical impact of low doses of dasatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol Oncol. 2012;22(suppl 1):8‐14. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lauseker M, Gerlach R, Tauscher M, Hasford J. Improved survival boosts the prevalence of chronic myeloid leukemia: predictions from a population‐based study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1441‐1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kanto CML Study Group . Phase II Clinical Trial of Low Dose Dasatinib in Patients With Resistant or Intolerant Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Who Are Treated With Low Lose Imatinib. World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) ID: JPRN‐UMIN000003499. http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=JPRN-UMIN000003499. Accessed April 1, 2016.

- 29. Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR) . The DIRECT study: Individualised Dasatinib Dosing for Elderly Patients With Chronic Myelogenous Leukaemia. ID: ACTRN12616000738426. https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?ACTRN=12616000738426. Accessed March 6, 2017.

- 30. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. De‐Escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib or sprYcel in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (DESTINY). http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01804985. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01804985?term=NCT01804985&rank=1. Accessed May 30, 2016.

- 31. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Therapy of Early Chronic Phase Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) With Dasatinib. http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02689440. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02689440?term=NCT02689440&rank=1. Accessed March 27, 2016.

- 32. European Leukemia Trial Registry . Dasatinib Holiday for Improved Tolerability (DasaHit). European Leukemia Trial Registry Id KN/ELN: LN_CMLSTU_2015_576. http://www.leukemia-net.org/trial/en/detail_trial.html?id=576. Accessed March 31, 2016.

- 33. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Optimization of TKIs Treatment and Quality of Life in Ph+ CML Patients ≥60 Years in Deep Molecular Response. http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02326311. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02326311?term=NCT02326311&rank=1. Accessed March 27, 2016.

- 34. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Treating Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) in Chronic Phase (CP) With Dasatinib (DasPAQT). http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02348957. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02348957?term=DasPAQT&rank=1. Accessed March 27, 2016.

- 35. World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform . Epidemiological and Clinical Research Information Network. A phase 2 study of mid‐term compliance and effectiveness of dasatinib therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. 2012. World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) ID: JPRN‐UMIN000007345. http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=JPRN-UMIN000007345. Accessed April 12, 2017.

- 36. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. OPTIM DASATINIB (Optimized Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Monotherapy) (OPTIM DASATINIB). http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01916785. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01916785. Accessed March 27, 2016.

- 37. Rea D, Rousselot P, Guilhot F, et al. Discontinuation of second generation (2G) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) in chronic phase (CP)‐chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients with stable undetectable BCR‐ABL transcripts [abstract]. Blood. 2012;120:916. [Abstract 916]. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rousselot P, Etienne G, Coiteux V, et al. Attempt to early discontinue dasatinib first line in chronic phase CML patients in early molecular response and included in the prospective OPTIM‐DASATINIB trial [abstract]. Haematologica. 2015;100(suppl 1):230. [Abstract P599]. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Imagawa J, Tanaka H, Okada M, et al; DADI Trial Group . Discontinuation of dasatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained deep molecular response for longer than 1 year (DADI trial): a multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2:e528‐e535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Open‐Label Study Evaluating Dasatinib Therapy Discontinuation in Patients With Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia With Stable Complete Molecular Response (DASFREE). http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01850004. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01850004?term=NCT01850004&rank=1. Accessed June 2, 2016.

- 41. Shah NP, Paquette R, Müller MC, et al. Treatment‐free remission (TFR) in patients with chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML‐CP) and in stable deep molecular response (DMR) to dasatinib‐the Dasfree Study [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128:1895. [Abstract 1895]. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rea D, Nicolini FE, Tulliez M, et al; France Intergroupe des Leucémies Myéloïdes Chroniques . Discontinuation of dasatinib or nilotinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: interim analysis of the STOP 2G‐TKI study. Blood. 2017;129:846‐854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Dasatinib for Patients Achieving Complete Molecular Response for Cure (D‐NewS Trial). http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01887561. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01887561?term=NCT01887561.&rank=1. Accessed January 27, 2017.

- 44. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Discontinuation of Dasatinib in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia‐CP Who Have Maintained Complete Molecular Remission for Two Years; Dasatinib Stop Trial. http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01627132. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01627132?term=Discontinuation+of+Dasatinib+in+Patients+With+Chronic+Myeloid+Leukemia-CP+Who+Have+Maintained+Complete+Molecular+Remission+for+Two+Years%3B+Dasatinib+Stop+Trial&rank=1. Accessed March 6, 2017.

- 45. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Front‐line Treatment of BCR‐ABL+ Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) With Dasatinib (CML1113). http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01761890. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01761890?term=NCT01761890&rank=1. Accessed May 30, 2016.

- 46. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. The Life After Stopping Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Study (The LAST Study). http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02269267. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02269267?term=NCT02269267&rank=1. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- 47. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Treatment‐free Remission Accomplished With Dasatinib in Patients With CML (TRAD). http://ClincalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02268370. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02268370?term=TRAD&rank=1. Accessed March 27, 2016.

- 48. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. European Stop Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Study (EURO‐SKI). http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01596114. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01596114?term=European+Stop+Tyrosine+Kinase+Inhibitor+Study&rank=1. Accessed January 27, 2017.

- 49. Ross DM, Hughes TP. How I determine if and when to recommend stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment for chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2014;166:3‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Erba HP. Molecular monitoring to improve outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: importance of achieving treatment‐free remission. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:242‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Talpaz M, Estrov Z, Kantarjian H, Ku S, Foteh A, Kurzrock R. Persistence of dormant leukemic progenitors during interferon‐induced remission in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Analysis by polymerase chain reaction of individual colonies. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1383‐1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boquimpani C, Schaffel R, Biasoli I, Bendit I, Spector N. Molecular responses at 3 and 6 months after switching to a second‐generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor are complementary and predictive of long‐term outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who fail imatinib. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1787‐1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shah NP, Kasap C, Weier C, et al. Transient potent BCR‐ABL inhibition is sufficient to commit chronic myeloid leukemia cells irreversibly to apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:485‐493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. O'Hare T, Walters DK, Stoffregen EP, et al. In vitro activity of Bcr‐Abl inhibitors AMN107 and BMS‐354825 against clinically relevant imatinib‐resistant abl kinase domain mutants. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4500‐4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dessilly G, Elens L, Panin N, Karmani L, Demoulin JB, Haufroid V. ABCB1 1199G>A polymorphism (rs2229109) affects the transport of imatinib, nilotinib and dasatinib. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17:883‐890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Francis J, Dubashi B, Sundaram R, Pradhan SC, Chandrasekaran A. Influence of Sokal, Hasford, EUTOS scores and pharmacogenetic factors on the complete cytogenetic response at 1 year in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. Med Oncol. 2015;32:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]