Abstract

Introduction

The effects of Build Our Kids Success—a 12-week, 1-hour before school physical activity program—on BMI and social–emotional wellness among kindergarten to eighth grade students was examined.

Study design

Non-randomized trial.

Setting/participants

From 24 schools in Massachusetts, there were 707 children, from kindergarten to eighth grade.

Intervention

Children registered for Build Our Kids Success in 2015–2016 participated in a 2 days/week or 3 days/week program. Nonparticipating children served as controls.

Main outcome measures

At baseline and 12 weeks, study staff measured children’s heights/weights; children aged ≥8 years completed surveys. Main outcomes were 12-week change in BMI (kg/m2), odds of a lower BMI category at follow-up, and child report of social–emotional wellness. Analyses were completed in March–June 2017.

Results

Follow-up BMI was obtained from 67% of children and self-reported surveys from 72% of age-eligible children. Children in the 3 days/week group had improvements in BMI z-score (−0.22, 95% CI= −0.31, −0.14) and this mean change was significantly different than the comparison group (−0.17 difference, 95% CI= −0.27, −0.07). Children in the 3 days/week group also had higher odds of being in a lower BMI category at follow-up (OR=1.35, 95% CI=1.12, 1.62); significantly different than the comparison group (p<0.01). Children in the 2 days/week program had no significant changes in BMI outcomes. Children in the 3 days/week group demonstrated improvement in their student engagement scores (0.79 units, p=0.05) and had nonsignificant improvements in reported peer relationships, affect, and life satisfaction versus comparison. The 2 days/week group had significant improvements in positive affect and vitality/energy versus comparison.

Conclusions

A 3 days/week before school physical activity program resulted in improved BMI and prevented increases in child obesity. Both Build Our Kids Success groups had improved social–emotional wellness versus controls.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Registration Number NCT03190135.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity affects 12.7 million (17%) children and adolescents throughout the U.S.1 Substantial work is being directed at efforts towards childhood obesity prevention. As a modifiable lifestyle habit, physical activity is a potential target for these efforts.

Evidence supports the health benefits of physical activity. Children who are more physically active have lower body fat percentage2 as well as lower BMI.3 Higher levels of physical activity early in life are associated with future physical activity levels as well as lower risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes later in life.4–7,8 There is also growing evidence that physical activity has a positive impact on psychosocial wellbeing, cognitive outcomes, and academic performance, as well as mental health.9,10

Despite these benefits, most children do not receive the recommended amount of physical activity.11 Parents cite time pressures, safety concerns, cost, and competition with screen time as challenges to supporting their children’s physical activity.12 As children spend the majority of their time in school, most of their physical activity occurs in this setting,13 however, schools overall do not promote physical activity.14,15 Barriers exist to school-based physical activity, including lack of available resources, concerns regarding burden on academic time, and perceived lack of knowledge to lead physical activity sessions.16 Interventions to increase physical activity in schools have shown mixed results, largely because of the overall heterogeneity in intervention design.17–19

Build Our Kids Success (BOKS) is a before school physical activity program present in more than 2,500 elementary and middle schools throughout the U.S. and internationally. The 60-minute, 12-week program includes a core curriculum delivered by trained volunteers. In a recent report in a single school, BOKS effectively decreased percentage of body fat, and increased aerobic performance in participants versus control students.20 The BOKS program is consistent with Huang and Glass’s systems-level framework to prevent obesity,21 and is rooted in the social contextual theory of behavior change.22 Previous research has found that before school physical activity programs increase overall physical activity23,24 and improve lean body mass.20

This study examines the effects of participation in a 2 days/week and 3 days/week BOKS program on anthropometric and social–emotional wellness outcomes among children and adolescents, aged 5–14 years, in Massachusetts. BOKS addresses current barriers to school-based physical activity programming by utilizing a before school program that does not conflict with academic time and by providing a core curriculum to empower volunteers in leading physical activity opportunities.

METHODS

This nonrandomized controlled trial was conducted in 24 elementary and middle schools in three Massachusetts communities during the 2015–2016 school year (Appendix Figure 1). Study design, eligibility, and recruitment have been published previously.25 In each school, children whose parents registered them for BOKS participated in a 1-hour, before school program. Nonparticipating children served as controls. Primary outcomes included students’ BMI z-score collected by study staff at baseline and at 12 weeks, and odds of being in a lower BMI category at follow-up. Students aged ≥8 years also completed surveys assessing social–emotional wellness. The study was approved by the IRBs of Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and Partners HealthCare, Boston, MA. The trial has been recorded in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03190135).

Study Population

All students in kindergarten to eighth grade (aged 5–14 years) within participating schools were eligible for participation. In partnership with the schools, all students had equal opportunity to participate in the BOKS program and randomization was not feasible. Recruitment occurred in September 2015 and January 2016 with follow-up measures collected in December 2015 and April 2016, respectively.

Parents were notified of the study through a flyer within a packet including BOKS registration and parental consent forms. Parents who registered their children in the BOKS program had the option to voluntarily enroll their child in the study. For students who chose not to participate, parents could consent for participation in the control group. If students consented to study participation and participated in both sessions, only the fall term was included in the analysis. Students were not blinded to study arm because of the nature of participation in the program (i.e., students knew if they were participating in BOKS and how many days per week). Outcomes assessors were also not blinded because of the nature of study data collection sessions (e.g., conducted during a BOKS session or outside of the program).

Students participated in BOKS for 12 weeks. A total of 16 schools administered the program 2 days/week and eight schools administered the program 3 days/week. Program frequency was determined by each district based on feasibility, staffing, and preference. BOKS sessions lasted ≅60 minutes and started with a warm-up game, transitioned into running, relay races, or obstacle courses, and included a skill of the week (e.g., plank, running, jumping). Volunteers, trained by the BOKS organization in program content and teaching methods, led each of the sessions. The BOKS curriculum has been developed by the BOKS educational leadership team and was not altered for the study. Assessments for fidelity to the BOKS curriculum were implemented to ensure consistency across schools.

Measures

Main outcomes included BMI parameters in all participants and social–emotional wellness and student engagement measures in students aged ≥8 years. The authors measured 12-week changes in BMI z-score and the odds of being in a lower BMI category at follow-up. At baseline and at 12 weeks, trained research assistants measured child height and weight without shoes and in light clothing using a Seca scale and a stadiometer. From these measurements, child BMI, and age- and sex-specific BMI z-score and percentile categories were calculated, using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.26 Percentile categories were defined as normal (≥5th to <85th percentile), overweight (≥85th to <95th percentile), obesity (≥95th percentile [specifically within 95% to <120%]); and severe obesity (≥120% of the 95th percentile).27

Students aged ≥8 years were invited to complete surveys at baseline and follow-up related to social–emotional wellbeing. Surveys were administered either in a school-based computer lab or via tablets/laptops. Based on NIH PROMIS measures previously validated within this age group, children responded on a 5-point scale to questions regarding interactions with peers,28 positive affect,29 and life satisfaction.29 For peer relationships, children responded to eight statements on the quality of relationships with friends and other peers in the past 7 days. For positive affect, children rated how accurately each of ten statements related to their positive emotion in the past 7 days. For life satisfaction, children rated how accurately each of five statements described their feelings about life. Based on the Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales (validated for ages 9–11 years), children responded on a 5-point scale to four questions about their health and energy level (vitality/energy subscale) and six statements on how interested and involved they were in school (student engagement).30 Results were examined separately by number of days the school administered BOKS (e.g., 2 or 3 days per week), adjusted for child age and sex, and accounted for clustering by school.

Child age, grade level, and gender were collected from student questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis

Distributions of participant characteristics across the 2 days/week, 3 days/week, and control group were analyzed using F-tests from 1-way ANOVA and chi-square tests. The data was assessed for outlier values and data entry errors. Subjects with biologically implausible values for height and weight and subjects with lower values for height recorded at 12 weeks compared with baseline were removed from the data set. In complete case analyses, effects of the interventions on BMI z-score and social–emotional wellness outcomes were assessed using linear mixed effects repeated measure models to account for clustering within participants over time. Similarly, ordinal logistic mixed effects repeated measure models were used to assess the effect of the interventions on the odds of being in a lower BMI percentile category at 12 weeks compared with baseline. In all models, the primary predictors were fixed effects for the intervention arm, time, and the time X intervention interaction term. The interaction term determined whether there was a different change in the 2 day/week and 3 day/week intervention groups compared with the control group. Models for BMI z-score and BMI percentile category were adjusted for school. Models for BMI were additionally adjusted for age and sex. Models for social–emotional wellness categories were adjusted for school, age, sex, and baseline BMI. All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4 and completed in March to June 2017.

RESULTS

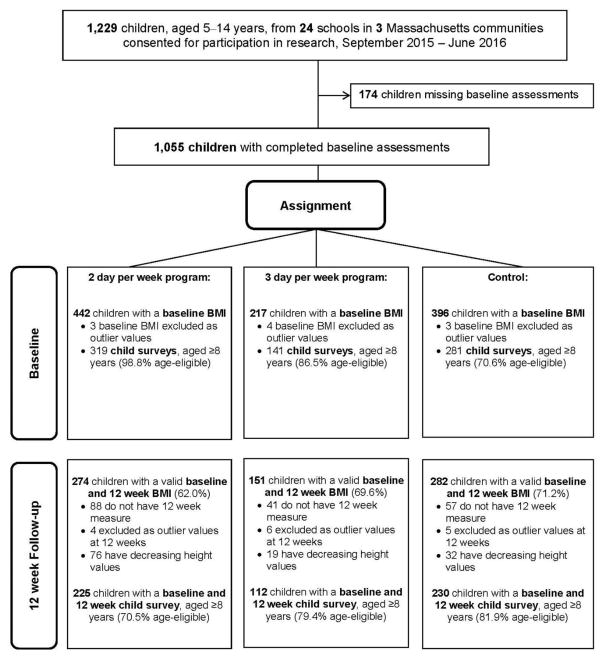

Figure 1 details the participant flow for this study. The sample size for the main BMI analyses included 274 children in the 2 days/week program, 151 children in the 3 days/week program, and 282 children in the control group, for a total of 707 children with complete BMI data at baseline and follow-up (67% of children with completed baseline assessments). Comparison of the 707 participants in this analysis with the 348 participants who consented but did not complete a follow-up assessment showed some differences. For example, the subjects in this analysis were slightly younger (mean age 9.1 vs 9.8 years) and had a lower baseline BMI (18.3 vs 19.0), but did not differ on gender.

Figure 1.

Participant flow for BOKS study.

BOKS, Build Our Kids Success

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of both intervention and control groups, across all schools. There were no statistically significant differences in gender, baseline BMI, BMI z-score or BMI percentile category between BOKS participants and controls. However, there were significant differences in age between the two intervention groups and control group. Across the participating school districts, average kindergarten to eighth grade enrollment was 5,174 children. Approximately 30% of children are considered economically disadvantaged and 31% identified as a racial/ethnic minority.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 707 Children With Baseline and 12-week BMI Assessments Participating in the BOKS Study

| Characteristics | 3 day/week BOKS participants (n=151) | 2 day/week BOKS participants (n=274) | Control participants (n=282) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 8.5 (1.3) | 9.4 (1.9) | 9.2 (1.9) | <0.01 |

| Boy, n (%) | 84 (55.6) | 130 (47.5) | 134 (47.5) | 0.21 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 18.0 (3.2) | 18.5 (4.0) | 18.3 (3.7) | 0.51 |

| BMI z-score, mean (SD) | 0.58 (1.0) | 0.41 (1.1) | 0.45 (1.1) | 0.31 |

| BMI percentile, age and sex adjusted, n (%) | 0.84 | |||

| Underweight (<5th percentile) | 4 (2.7) | 9 (3.3) | 9 (3.2) | |

| Normal weight (5th – <85th percentile) | 95 (62.9) | 180 (65.6) | 188 (66.7) | |

| Overweight (85th – <95th percentile) | 28 (18.5) | 40 (14.6) | 39 (13.8) | |

| Obese (≥95th percentile – severe) | 18 (11.9) | 30 (11.0) | 37 (13.1) | |

| Severe obesity (≥120% of 95th percentile) | 6 (4.0) | 15 (5.5) | 9 (3.2) | |

| Social-emotional wellness scores, mean (SD) | ||||

| Peer relationships, mean (SD) | 28.2 (8.6) | 27.6 (7.5) | 29.2 (7.2) | 0.15 |

| Positive affect, mean (SD) | 33.6 (8.5) | 33.5 (7.0) | 34.4 (6.9) | 0.48 |

| Life satisfaction, mean (SD) | 17.1 (3.5) | 17.1 (2.9) | 17.5 (2.8) | 0.36 |

| Vitality/energy, mean (SD) | 16.5 (3.2) | 15.5 (3.0) | 16.0 (2.6) | 0.02 |

| Student engagement, mean (SD) | 12.2 (4.4) | 12.6 (3.8) | 12.8 (3.8) | 0.55 |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05) of F-statistic or chi-square statistic.

BOKS, Build Our Kids Success

Within the 3 days/week group, adjusted mean BMI z-score was 0.51 (SE=0.14) at baseline and 0.29 (SE=0.14) at 12 weeks, an average change of −0.22 units (95% CI= −0.31, −0.14; Table 2). In the control group, adjusted mean BMI z-score was 0.44 (SE=0.08) at baseline and 0.39 (SE=0.20) at 12 weeks, an average change of −0.05 units (95% CI= −0.11, 0.01). The adjusted BMI z-score difference was significantly different in the 3 days/week group versus controls (−0.17 unit difference, 95% CI= −0.27, −0.07). Children who participated in BOKS 2 days/week did not demonstrate BMI z-score improvement from baseline to 12 weeks (−0.01 unit change, 95% CI= −0.07, 0.05). Program effects are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Changes in BMI, BMI z-score and Categories From Baseline to 12 Weeks, by Intervention Assignment (N=707)

| BMI outcomes | Baseline | 12 week follow up | Adjusted mean change | p-value | Adjusted difference | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Adjusted mean (SE) | β (95% CI) | |||||

| BMI z-score, unitsb | ||||||

| 3 days/week program | 0.51 (0.14) | 0.29 (0.14) | −0.22 (−0.31, −0.14) | <0.01 | −0.17 (−0.27, −0.07) | <0.01 |

| 2 days/week program | 0.41 (0.09) | 0.40 (0.09) | −0.01 (−0.07, 0.05) | 0.81 | 0.04 (−0.04, 0.13) | 0.33 |

| Control | 0.44 (0.08) | 0.39 (0.08) | −0.05 (−0.11, 0.01)) | 0.10 | ref | ref |

|

|

||||||

| Baseline | 12 week follow up | Adjusted odds of being at a lower category at follow up | p-value | Multiplicative difference in ORs | p-value | |

|

|

||||||

| BMI categoryb | % | OR (95% CI) | ||||

|

|

||||||

| 3 days/week program | ||||||

| <5th percentile | 2.7 | 3.3 | ||||

| 5th to <85th percentile | 62.9 | 68.9 | ||||

| 85th to <95th percentile | 18.5 | 15.9 | 1.35 (1.12, 1.62) | <0.01 | 1.36 (1.09, 1.69) | <0.01 |

| 95th to < Severe obesity | 11.9 | 8.6 | ||||

| ≥Severe obesity | 4.0 | 3.3 | ||||

| 2 days/week program | ||||||

| <5th percentile | 3.3 | 3.7 | ||||

| 5th to <85th percentile | 65.7 | 66.4 | ||||

| 85th to <95th percentile | 14.6 | 12.8 | 1.03 (0.93, 1.15) | 0.55 | 1.04 (0.89, 1.22) | 0.61 |

| 95th to <Severe obesity | 11.0 | 11.3 | ||||

| ≥Severe obesity | 5.5 | 5.8 | ||||

| Control | ||||||

| <5th percentile | 3.2 | 2.8 | ||||

| 5th to <85th percentile | 66.7 | 66.0 | ||||

| 85th to <95th percentile | 13.8 | 17.4 | 0.99 (0.88, 1.11) | 0.89 | ref | ref |

| 95th to <Severe obesity | 13.1 | 11.4 | ||||

| ≥Severe obesity | 3.2 | 2.5 | ||||

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Adjusted estimates from repeated measures model. Adjusted for school, age, and sex.

Adjusted estimates from repeated measures model. Adjusted for school.

Children who participated in the 3 days/week BOKS program had significantly higher odds of being in a lower BMI category at follow-up compared with baseline (OR=1.35, 95% CI=1.12, 1.62; Table 2). This effect was not seen in children who participated in BOKS 2 days/week (OR=1.03, 95% CI=0.93, 1.15) or in the control group (OR=0.99, 95% CI=0.88, 1.11). The OR for children in the 3 days/week program was significantly different than the OR for the control group (p<0.01).

Significant improvements were found among BOKS participants related to student engagement, positive affect, and vitality/energy (Table 3). Student engagement scores improved among the 3 days/week program (0.79 unit difference, 95% CI= −0.01, 1.60) compared with children in the comparison group. Students in the 2 days/week group had significant improvements in both positive affect (1.41 unit difference, 95% CI=0.16, 2.65) and vitality/energy score (0.60 unit difference, 95% CI=0.11, 1.08) when compared with children in the comparison group. Students in the 3 day/week group did not demonstrate these effects.

Table 3.

Changes in Social-Emotional Wellness Scales From Baseline to 12 Weeks, by Intervention Assignment

| Social-emotional wellness scales | Adjusted mean change | p-value | Adjusted difference | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β (95% CI) | ||||

| Peer relationships (N=482) | ||||

| 3 days/week program | 0.52 (−0.88, 1.93) | 0.46 | 0.47 (−1.21, 2.16) | 0.58 |

| 2 days/week program | 1.24 (0.26, 2.23) | 0.01 | 1.20 (−0.15, 2.54) | 0.08 |

| Controls | 0.05 (−0.91, 1.01) | 0.92 | ref | |

| Positive affect (N=449) | ||||

| 3 days/week program | 0.64 (−0.62, 1.90) | 0.32 | 0.61 (−0.91, 2.12) | 0.43 |

| 2 days/week program | 1.44 (0.52, 2.36) | <0.01 | 1.41 (0.16, 2.65) | 0.03 |

| Controls | 0.04 (−0.84, 0.91) | 0.94 | ref | |

| Life satisfaction (N=488) | ||||

| 3 days/week program | 0.65 (0.14, 1.17) | 0.01 | 0.48 (−0.14, 1.11) | 0.13 |

| 2 days/week program | −0.10 (−0.47, 0.26) | 0.57 | −0.27 (−0.78, 0.23) | 0.29 |

| Controls | 0.17 (−0.19, 0.53) | 0.36 | ref | |

| Vitality/energy (N=511) | ||||

| 3 days/week program | −0.36 (−0.86, 0.14) | 0.16 | −0.39 (−0.99, 0.21) | 0.20 |

| 2 days/week program | 0.63 (0.28, 0.98) | <0.01 | 0.60 (0.11, 1.08) | 0.02 |

| Controls | 0.03 (−0.32, 0.38) | 0.85 | ref | |

| Student engagement (N=500) | ||||

| 3 days/week program | 0.81 (0.13, 1.48) | 0.02 | 0.79 (−0.01, 1.60) | 0.05 |

| 2 days/week program | 0.47 (0.01, 0.93) | 0.05 | 0.46 (−0.18, 1.10) | 0.16 |

| Controls | 0.01 (−0.44, 0.47) | 0.95 | ref | |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). Models are adjusted for school, age, sex, and baseline BMI.

DISCUSSION

Within a large sample of elementary and middle school students, a before school physical activity intervention was associated with improvement in physical and social–emotional health. Students who participated in BOKS 3 days/week experienced significant improvement across measures of BMI compared with the comparison group, including absolute BMI z-score change (−0.22), and favorable BMI category at follow-up. These changes are clinically significant based on 2017 U.S. Preventative Task Force recommendations for pediatric obesity screening, in which a BMI z-score change of 0.20–0.25 indicates anthropometric changes associated with improvement in cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors.31 Students participating in the intervention also had significant improvement in student engagement, positive affect, and vitality/energy measures.

BMI z-score decreased slightly or remained stable among children in the control group and the 2 days/week group throughout the intervention period. All students had access to twice weekly physical education and it is possible that this accounted for the weight status maintenance. These findings suggest that the increased activity within the 3 days/week group may have been sufficient to influence BMI changes.

The overall heterogeneity of intervention structure and duration within the literature allows few direct comparisons with this study. A small RCT of a 3 days/week, 1-hour after school physical activity intervention decreased the percentage of students classified as overweight compared with controls at 3-month follow-up.32 Short-term school-based interventions combining nutrition and physical activity have been successful in reducing the number of students who are overweight.33–35 Prior studies using before school physical activity interventions increased total daily moderate to vigorous physical activity23,24 and improved body composition measures.20 This study is unique in explicitly evaluating BMI outcomes for a before school physical activity intervention. Taken together, these findings support before school physical activity programming as a successful strategy for prevention of overweight and obesity.

Given the mixed literature on the effectiveness of school-based physical activity interventions,18,19,36 it is worth considering what unique aspects of this program may have encouraged children to be more active, leading to positive changes in BMI. Previous research identifies adequate time spent in physical activity,37 greater enjoyment of physical activity because of participation with friends,38 modeling of increased physical activity by adult role models,39 sufficient staff training,37 and small class sizes (less than 25 students/teacher) as key determinants of successful school-based programming,40 all of which are included in BOKS. Specifically, children participate with a group of peers at the direction of a trained, adult role model, with content built around fun, fitness games that encourage kids to move more.

Although a large body of evidence supports a positive effect of physical activity on academic and cognitive outcomes,9,14,41 less literature addresses social–emotional wellness outcomes. Previous studies have focused on specific populations, such as children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,42,43 or have found associations such as decreased depressive symptoms with increased physical activity levels.44 There is limited work regarding the effect of physical health on more general measures of psychosocial wellbeing. These results of a significant effect on student engagement, positive affect, and vitality/energy, as well as positive trend for life satisfaction and peer relationships, have not been previously reported. The measures used in this study reflect a growing trend towards evaluating patient-reported outcomes in more subjective measures of health. Although the use of the Healthy Pathways scales outside of the previously validated age range is a limitation, these novel results highlight the need for further research on the effect of physical activity interventions on wellbeing.

This study is innovative in its extensive evaluation of the effects of a before school physical activity program on physical and social–emotional wellness across multiple communities. Additionally, it presents an intervention that may be an efficient way to increase children’s physical activity. Schools have existing infrastructure, and co-locating physical activity programs at a location where children are already present may increase access. It is also efficient to use the time before school for physical activity programs. Whereas after school programs may have unintended consequences of replacing other physical activity involvement, before school programs take advantage of a time when children are not usually active.45 Given that this intervention is pre-existing and currently present in more than 2,500 schools throughout the U.S. and internationally, dissemination opportunities appear feasible.

Although the conclusions of this study are limited to the three communities that participated, large scale child participation in programs such as this has the potential to lead to positive changes in health at the population level. Lastly, this study assessed how physical activity exposure (i.e., 2 days/week versus 3 days/week programming) may impact outcomes. Within this sample, 2 days/week participation may be sufficient to achieve social–emotional benefits; however, physical health benefits required 3 days/week exposure.

Limitations

In partnership with participating communities, this study’s nonrandomized design allowed all students an equal opportunity to participate in BOKS. Despite this intention, the lack of randomization is a significant limitation as baseline differences between children who participated versus those who did not could explain the different effects on weight status and social–emotional wellness observed between groups.

Additionally, whether children participated in 2 days/week versus 3 days/week programming was determined by school preference. Factors such as availability of volunteer staff or space limitations may have driven each school’s programming decision. These variations, as opposed to program exposure, could in part explain the observed differences between the 2 days/week and 3 days/week programs.

In the setting of nonrandomization, there were baseline differences in age between groups and these differences may have impacted findings. The use of BMI z-scores and adjustment of models for age and sex attempted to reduce this effect. Post-hoc analyses did not find effect modification by gender. SES and race/ethnicity at the individual level were not available, and could not be controlled for in analyses.

This study addressed barriers to children’s physical activity with the provision of safe and free access to physical activity opportunities as well as a knowledge base with which volunteers successfully delivered effective programing. Despite this, it is unclear if specific barriers to participation in this program exist that prevent some students from benefitting.

Although efforts were made to track any protocol deviations, subtle variations in BOKS delivery across schools may have existed that were out of the authors’ control. Finally, as objective measures of physical activity were not tracked, there is not quantitative data on the physical activity intensity or individual compliance with physical activity lessons.

CONCLUSIONS

A before school physical activity program where children participated 3 days/week resulted in improved BMI and prevented increases in child overweight and obesity. Compared with the comparison group, both BOKS groups experienced a range of improvements in social–emotional wellness as well. Increasing access to before school physical activity programs has the potential to positively impact child physical and mental health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the institutions, research staff and students for their participation in Build Our Kids Success and the research study.

Research reported in this publication was supported by Build Our Kids Success, an initiative of the Reeboks Foundation, and The Boston Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsors.

Harvard-wide Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship. Rachel Whooten is supported by NICHD grant number T32HD075727. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the analysis. Rachel Whooten wrote the first draft of this article, with significant contributions by Meghan Perkins and Monica Gerber. Elsie Taveras revised the article for important intellectual content.

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT03190135.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(219):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dencker M, Thorsson O, Karlsson MK, et al. Daily physical activity related to body fat in children aged 8–11 years. J Pediatr. 2006;149(1):38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sijtsma A, Sauer PJ, Stolk RP, Corpeleijn E. Is directly measured physical activity related to adiposity in preschool children? Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(5–6):389–400. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2011.606323. https://doi.org/10.3109/17477166.2011.606323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly JJ. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour and energy balance in the preschool child: opportunities for early obesity prevention. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67(3):317–325. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108008604. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665108008604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(5):963–975. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cesa CC, Sbruzzi G, Ribeiro RA, et al. Physical activity and cardiovascular risk factors in children: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Prev Med. 2014;69:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rush E, Simmons D. Physical activity in children: prevention of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Med Sport Sci. 2014;60:113–121. doi: 10.1159/000357341. https://doi.org/10.1159/000357341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128(Suppl 5):S213–256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly JE, Hillman CH, Castelli D, et al. Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(6):1197–1222. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000901. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillman CH, Pontifex MB, Raine LB, Castelli DM, Hall EE, Kramer AF. The effect of acute treadmill walking on cognitive control and academic achievement in preadolescent children. Neuroscience. 2009;159(3):1044–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassett-Gunter R, Rhodes R, Sweet S, Tristani L, Soltani Y. Parent support for children’s physical activity: a qualitative investigation of barriers and strategies. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2017;88(3):282–292. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2017.1332735. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2017.1332735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson JA, Schipperijn J, Kerr J, et al. Locations of physical activity as assessed by GPS in young adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):e20152430. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2430. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasberry CN, Lee SM, Robin L, et al. The association between school-based physical activity, including physical education, and academic performance: a systematic review of the literature. Prev Med. 2011;52(suppl 1):S10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shape of the nation report: status of physical education in the USA. Reston, VA: National Association of Sports and Physical Activity & American Heart Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weatherson KA, Gainforth HL, Jung ME. A theoretical analysis of the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of school-based physical activity policies in Canada: a mixed methods scoping review. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0570-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Must A, et al. Shape Up Somerville two-year results: a community-based environmental change intervention sustains weight reduction in children. Prev Med. 2013;57(4):322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mei H, Xiong Y, Xie S, et al. The impact of long-term school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index of primary school children - a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:205. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2829-z. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2829-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby K, LaRocca RL. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD007651. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub2. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wescott WL, Puhala K, Colligan A, LaRosa Loud R, Cobbett R. Physiological effects of the BOKS before-school physical activity program for preadolescent youth. J Exerc Sports Orthop. 2015;2(2):1–7. https://doi.org/10.15226/2374-6904/2/2/00129. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang T, Glass T. Transforming research strategies for understanding and preventing obesity. JAMA. 2008;300(15):1811–1813. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1811. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.15.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, et al. Model for incorporating social context in health behavior interventions: applications for cancer prevention for working-class, multiethnic populations. Prev Med. 2003;37(3):188–197. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00111-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tompkins CL, Flanagan T, Lavoie J, 2nd, Brock DW. Heart rate and perceived exertion in healthy weight and obese children during a self-selected physical activity program. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(7):976–981. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0374. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2013-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stylianou M, van der Mars H, Kulinna PH, Adams MA, Mahar M, Amazeen E. Before-school running/walking club and student physical activity levels: an efficacy study. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2016;87(4):342–353. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2016.1214665. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2016.1214665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pojednic R, Peabody S, Carson S, Kennedy M, Bevans K, Phillips EM. The effect of before school physical activity on child development: A study protocol to evaluate the Build Our Kids Success (BOKS) Program. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.06.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL, Freedman DS, Johnson CL, Curtin LR. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index-for-age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1314–1320. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28335. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gershon RC, Wagster MV, Hendrie HC, Fox NA, Cook KF, Nowinski CJ. NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Neurology. 2013;80(11 suppl 3):S2–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e5f. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravens-Sieberer U, Devine J, Bevans K, et al. Subjective well-being measures for children were developed within the PROMIS project: presentation of first results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(2):207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bevans KB, Riley AW, Forrest CB. Development of the healthy pathways child-report scales. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(8):1195–1214. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9687-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9687-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2417–2426. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6803. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.6803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El Ansari W, El Ashker S, Moseley L. Associations between physical activity and health parameters in adolescent pupils in Egypt. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(4):1649–1669. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7041649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flores R. Dance for health: improving fitness in African American and Hispanic adolescents. Public Health Rep. 1995;110(2):189–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, Van Horn L, KauferChristoffel K, Dyer A. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. for Latino preschool children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(9):1616–1625. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.186. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrell JS, McMurray RG, Bangdiwala SI, Frauman AC, Gansky SA, Bradley CB. Effects of a school-based intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors in elementary-school children: the Cardiovascular Health in Children (CHIC) study. J Pediatr. 1996;128(6):797–805. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70332-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metcalf B, Henley W, Wilkin T. Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54) BMJ. 2012;345:e5888. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5888. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russ LB, Webster CA, Beets MW, Phillips DS. Systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-component interventions through schools to increase physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(10):1436–1446. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0244. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2014-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maturo CC, Cunningham SA. Influence of friends on children’s physical activity: a review. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):e23–38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301366. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biddle S, Goudas M. Analysis of children’s physical activity and its association with adult encouragement and social cognitive variables. J Sch Health. 1996;66(2):75–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1996.tb07914.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1996.tb07914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirkham-King M, Brusseau TA, Hannon JC, Castelli DM, Hilton K, Burns RD. Elementary physical education: a focus on fitness activities and smaller class sizes are associated with higher levels of physical activity. Prev Med Rep. 2017;8:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.09.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hillman CH, Pontifex MB, Castelli DM, et al. Effects of the FITKids randomized controlled trial on executive control and brain function. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1063–1071. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3219. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoza B, Smith AL, Shoulberg EK, et al. A randomized trial examining the effects of aerobic physical activity on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in young children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43(4):655–667. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9929-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9929-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith AL, Hoza B, Linnea K, et al. Pilot physical activity intervention reduces severity of ADHD symptoms in young children. J Atten Disord. 2013;17(1):70–82. doi: 10.1177/1087054711417395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711417395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kremer P, Elshaug C, Leslie E, Toumbourou JW, Patton GC, Williams J. Physical activity, leisure-time screen use and depression among children and young adolescents. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(2):183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun HA, Kay CM, Cheung P, Weiss PS, Gazmararian JA. Impact of an elementary school-based intervention on physical activity time and aerobic capacity, Georgia, 2013–2014. Public Health Rep. 2017;132(2 suppl):24S–32S. doi: 10.1177/0033354917719701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.